- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for February 2, 2018

Forget that nettlesome D.C. memo for a moment and lay plans to raid the snack aisle. Maybe try the parsnip chips.

This weekend brings the Super Bowl of pro football, a national moment of togetherness and, yes, a global phenomenon – even if it’s no World Cup of fútbol.

The water-cooler breakdowns of that game will barely have ended when eyes will turn to the Olympics Feb. 9. Stories and substories always abound. (The Monitor’s Christa Case Bryant is en route to South Korea to report some of them.)

At play in both spectacles: modern athletes defying the limitations often associated with aging. Tom Brady – the New England Patriots quarterback, the Roger Federer of football, and the gold-standard player at his position – is, at 40, chasing his sixth ring.

And under the rings at the Winter Games it won’t just be the curling crowd exhibiting maturity. Among 10 likely competitors over 40 are German speedskater Claudia Pechstein and Japanese ski jumper Noriaki Kasai, both 45 and repeat Olympians.

What’s that about? Workout regimens, to be sure. Great gear and new training technology. It’s also a mind-set that puts possibility over a standard prognosis. Says Matt Cassel, Brady’s backup for a few years in the mid-2000s: “You can say what you want, but for him, age doesn’t matter.”

Now to our five stories for today, looking at the reexamination of some norms, outlooks, and practices – and at a Lebanese film that highlights hope for reconciliation.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

War by the numbers: in Afghanistan, a growing fight over facts

Does keeping secrets make a war more winnable? A government watchdog has been frustrated by its inability to publish basic facts about the war effort in Afghanistan. And some analysts worry that that will not help the situation on the ground.

The Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, or SIGAR, is a US government watchdog established by Congress in 2008 to keep tabs on what has become America’s longest war. Its latest quarterly report, on Jan. 30, happened to follow an especially violent week-plus in Afghanistan that saw scores killed in multiple high-profile attacks by the Taliban and the so-called Islamic State in Kabul and elsewhere. But of perhaps more significance to the future of the conflict, SIGAR complained that official metrics that once were public – such as Afghan troop strength and casualty numbers – have been classified by the US military and are no longer published. Analysts, who say there is no doubt that the Taliban are making steady gains across the country at the expense of embattled Afghan government forces, say the hidden data amounts to a coverup. “We’ve seen more than a dozen years of self-serving games played with these metrics,” says a Western official in Kabul with access to detailed security assessments. “We are trying to find a way to triage the violence and achieve some modicum of stability,” the official says. “There is going to be no win here for America.”

War by the numbers: in Afghanistan, a growing fight over facts

By the most obvious metrics, the conflict in Afghanistan has seen a spike in violence during the past two weeks, already half a year after President Trump declared his “fight and win” strategy for America’s longest war.

In Kabul, Taliban insurgents laced an ambulance with explosives, killing more than 100 people at the gate of the Interior Ministry complex on Jan. 27. Taliban gunmen also besieged the Intercontinental hotel, killing more than 20 on Jan. 20.

And jihadists of the so-called Islamic State, not to be outdone, claimed responsibility for attacking the offices of Save the Children in Jalalabad, east of Kabul, killing four staff members. In Kabul, ISIS militants attacked an army post near a military academy, killing 11 on Jan. 29.

Yet even as Afghans coped with the headline-grabbing carnage, official metrics of the state of the war that once were public – insurgent control of territory, for example, and Afghan troop strength and casualty numbers – are no longer being published by the US military.

Analysts say there is no doubt that the Taliban are making steady gains across the country at the expense of embattled, US- and NATO-backed Afghan government forces. And a BBC investigation this week found that the Taliban now “threatens” 70 percent of the country, a level higher than defined by previous US military reporting.

But the lack of updated US data – noted disparagingly by the US government’s watchdog, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), in its latest quarterly report on Jan. 30 – raises questions about why the figures are being hidden now.

The increased opacity comes after Mr. Trump last summer ordered several thousand more US troops to Afghanistan, raising the total level to some 14,000, on a mission to secure “victory.” Airstrikes have been ramped up to the highest level since 2010.

“Of course it’s a cover-up. What else can it be, when you hide figures? The thing is, it is not going well,” says Thomas Ruttig, a co-director of the Kabul-based Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) with decades of experience in Afghanistan.

“There are millions and millions [of dollars] thrown out for what they call ‘public diplomacy’ and ‘narrative building,’ or whatever, and no one except themselves is believing in it,” says Mr. Ruttig, speaking from Berlin.

The war is “definitely not ended or even helped toward that end, by playing these nontransparent games with the numbers and the facts,” says Ruttig. All the five trends he monitors – from security incidents and territorial control to Afghan force casualties – have grown worse since 2015, and many are at record levels.

“It means the conflict has become more violent, more brutal, and more widespread,” adds Ruttig. “It also would be good, vis-à-vis voters and taxpayers, if those figures remained in the public sphere so we can make our own assessment of how our governments are doing.”

Such an assessment has been made more difficult by an increasing scarcity of official figures about the Afghanistan war. In what it called a “development troubling for a number of reasons,” SIGAR, which was established by Congress in 2008, reported that it was the first time it had been “specifically instructed not to release information marked ‘unclassified’ to the American taxpayer.”

That unclassified data was “one of the last remaining publicly available indicators” on how the war is faring, SIGAR wrote, noting that the fact the trend was negative for years “should cause even more concern about its disappearance from public disclosure and discussion.”

'The enemy knows what the situation is'

SIGAR also noted that last fall, for the first time since 2009, the Defense Department classified details about Afghan force strength, as well as key metrics such as Afghan force attrition and capabilities.

The missing figures indicate that, as of October, Taliban territorial control of districts grew by one point over the previous quarter to 14 percent, with 30 percent “contested” with the Afghan government, according to media reports. Likewise, areas of government “control or influence” dropped one point to 56 percent.

“The enemy knows what districts they control, the enemy knows what the situation is. The Afghan military knows what the situation is,” John Sopko, the Special Inspector General, told NPR this week. “The only people who don’t know what’s going on are the people who are paying for it, and that’s the American taxpayer.”

In response to the SIGAR report, the US-led NATO operation Resolute Support in Kabul blamed “human error in labeling,” and stated that there had been no intention to hide unclassified figures.

But a Western official in Kabul with access to detailed security assessments sees it differently.

“We’ve seen more than a dozen years of self-serving games played with these metrics,” says the official, who could not be further identified.

“Ever since Trump took power, there is a real obsession with winning, and the war in Afghanistan has moved beyond that,” says the official, adding that a military solution is “a fantasy.”

“We are trying to find a way to triage the violence and achieve some modicum of stability,” the official says. “There is going to be no win here for America. Trump doesn’t get that, so you need to hide the reality of what’s going on.”

The SIGAR report coincided with publication of a months-long BBC project to map every district in the country. It found that the Taliban was “openly active” in 70 percent of Afghanistan, far more than when US and NATO combat troops left in late 2014. The BBC also found that half the population lived in areas either controlled by the Taliban or where insurgents “openly and regularly mount attacks."

How many Taliban?

Also in the past week, NBC News quoted US military sources as saying that the number of Taliban fighters stood at 60,000, fully three times the figure of 20,000 that has been reported for years. While analysts note that any estimate of “troop” strength of a guerrilla force is problematic in Afghanistan, the number suggested that US-led forces had long downplayed the scale of fight.

Amid the recent escalation of violence in Kabul, Trump stated that the US would not hold talks with the Taliban, reversing a long-standing US policy to pressure the insurgents to the negotiating table.

“We don’t want to talk to the Taliban,” Trump said Monday, citing the Kabul atrocities. “We’re going to finish what we have to finish, what nobody else has been able to finish, we’re going to be able to do it.”

When rolling out his Afghanistan strategy last August, Trump indicated that the US would withhold more information from the public – and the Taliban.

“America’s enemies must never know our plans or believe they can wait us out. I will not say when we are going to attack, but attack we will,” said Trump. “We are not nation-building again. We are killing terrorists.”

Former President Barack Obama, trying to wind up the Afghan war on his watch, first declared in 2010 that US forces would largely withdraw by 2014, prompting critics to charge that the Taliban had merely to mark their calendars, and wait.

Even if the precise details of the state of the battlefield are less clear today, the trajectory has not changed. The Taliban made significant gains, doubling the number of districts under its control from late 2015, according to SIGAR, but gains in 2017 were less dramatic.

An eroding edifice

No matter how the metrics are defined, though, the results indicate that America's longest war will become longer.

“ ‘Strategic’ often means different things to different sides,” says Ruttig of AAN. The Taliban foothold in what the US military calls “dusty districts,” for example, which are not close to main roads or cities, may not be deemed significant to Washington but are critical to the Taliban.

“I have heard [US commanders] say, ‘If the Taliban are there, then we don’t bother too much about them,’ ” says Ruttig. “That’s exactly the wrong thing, because the Taliban are quite happily living and organizing themselves in the ‘dusty districts’ – they don’t need much. And from there, they move forward.”

That means getting close to the gates of Kabul, with a strong presence in neighboring provinces like Logar and Wardak, and many others, as well as the ability to target the capital itself. The results are not like in Libya in 2011, when the frontline shifted 30 miles a day or more; instead it changes 50 yards, or 500 yards.

“It’s not like a total collapse of the Afghan security forces. It’s more like watching termites eat away at the edifice,” says the Western official in Kabul.

And despite recent reports that the number of Taliban fighters is larger than usually estimated, experts say the number of devotees to a social movement like the Taliban – whose members may be a vegetable seller on the street corner, a farmer, or even a government employee by day – may be impossible to quantify.

No census has ever been conducted in Afghanistan, and an attempt in 1979 was aborted when some census-takers were killed after knocking on doors, especially in deeply conservative Pashtun areas that have traditionally formed the backbone of Taliban support, says the official.

“So understandably the people in remote valleys were never counted, and they had lots of babies,” he says. “I think the recruiting pool for the Taliban is dramatically larger than it once was, and it is dramatically underestimated by the [Afghan] government and by the Americans.”

Share this article

Link copied.

US deregulation push to take aim at fisheries, backcountry

The US government is opening the door to more resource extraction from American lands and waters. Do those changes mean that more local voices are finally being heard – or that science is being ignored in favor of industry?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As the Trump administration opens up federal lands and waters for commercial exploitation, it is also working to decentralize the rule-making process. Amid new policies that will ease coal regulations and open up most of the country’s coastal waters for oil drilling, the Department of the Interior is being reorganized so that state-by-state jurisdictions are replaced by 13 regions. The move is welcomed by loggers, fishermen, hunters, miners, and others who eke out a living on public lands. But critics say that the new approach could threaten the sustainability of the nation’s natural resources. “Democrats and Republicans both want solutions and are tired of centralized Washington decisions," says John Freemuth, a professor of public policy and administration at Boise State University. “That’s why the administration’s moves are timely.” But, he adds, “It is a profound thing if it’s not done right.”

US deregulation push to take aim at fisheries, backcountry

In Talbot County, Md., waterman Jeff Harrison can trace his family lineage to wind-hardened pioneers combing the Chesapeake Bay since the 19th century for oysters, crabs, and rockfish.

Yet even as one of America’s great estuaries slowly returns to health after decades of pollution and overfishing, Mr. Harrison’s generational claim to the water and its wealth is being revoked by federal and state decree in the name of conservation science.

“We want to see a clean Chesapeake Bay, but we also want to be able to make a few dollars out there,” says Mr. Harrison, president of the Talbot Watermen Association, who saw his rockfish, or striped bass, quota cut to zero this year even amid a stock rebound. “The average age of the commercial fisherman in the Bay is 58 years old. The job is already hard enough. I’m probably going to be the last commercial fisherman in my family.”

It’s partly in response to such concerns that the Trump administration – particularly Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke and Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross – is starting to both decentralize its decisionmaking and open up America’s oceans and lands to resource extraction.

But as America’s powerful land and water managers promise broad reforms to bring rule-making closer to the bayous and prairies, clashes over science in resource management are likely to intensify. After all, the new Republican administration has put into fresh play America’s core natural wealth – its game, minerals, fish, fossil fuels, and landscapes – in ways that are challenging scientific thinking and, potentially, threatening the sustainability of those resources.

“We need good, sound science, but science has become politicized,” says John Freemuth, director of the Cecil D. Andrus Center for Public Policy at Boise State University and an expert on the intersection of science and resource management.

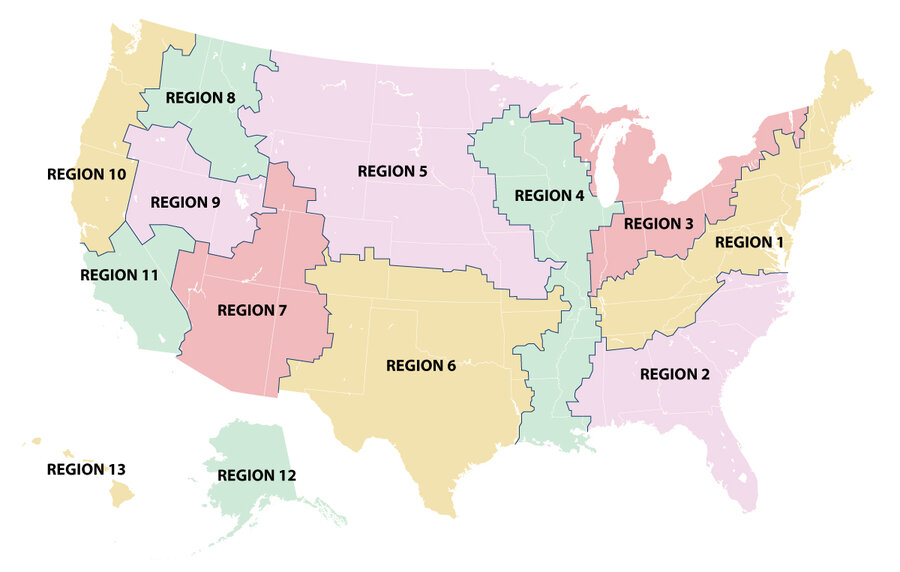

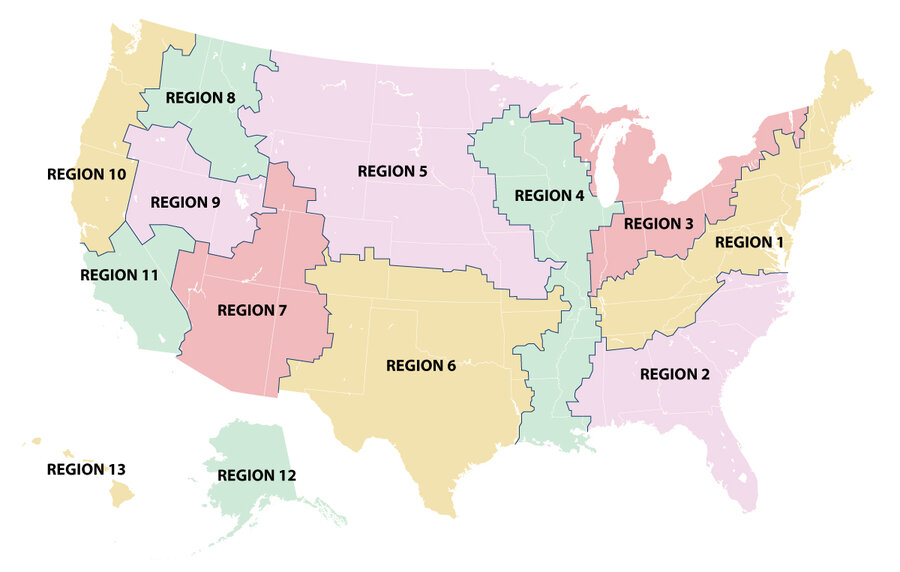

The push to deregulate the American backcountry is stoking centuries-old tensions over how the federal government preserves or exploits its land and natural resources. It’s epitomized, in some ways, by recent announcements by the Interior Department that they will open up almost all US coastal waters to oil drilling, are peeling back coal regulations, and will overhaul the department’s organization so that state-by-state jurisdictions are replaced by 13 regions, guided by watersheds. An Appalachian region would stretch from Bangor, Maine, all the way to Huntsville, Ala.

E&E News, US Geological Survey

“It’s ... about getting more resources out to the field,” Deputy Interior Secretary David Bernhardt told Energy & Environment News, adding that “the generals will be closer to the troops.”

Together, Interior and Commerce oversee roughly 500 million acres of land – a fifth of the US land mass, and nearly half of all Western lands – along with more than 3 million nautical square miles of open ocean.

Interior alone has 70,000 employees, a complex bureaucracy that laces politics and science, as well as intricate relationships with all 50 governors, their respective state bureaucracies, and phalanxes of interest groups ranging from the liberal Sierra Club to the conservative American Land Council.

But while these lands and waters may belong to every American, some feel particularly invested, including the roughnecks, loggers, fishermen, hunters, snowmobilers, and miners who eke out tough livings from rough but beautiful surroundings.

Many of them, like New Hampshire boat owner, biologist, and former fishery council member Ellen Goethel, have watched resources grow increasingly off-limits under what she calls a “one-size-fits-all” conservation approach implemented by the Obama administration. The New Hampshire groundfish fleet – the nation’s first – had 150 boats at Obama’s inauguration. Only six remained when Trump was sworn into office a year ago.

At a gun show in Las Vegas last week, Secretary Zinke, a former Navy SEAL from Whitefish, Mont., agreed that “local voices have been ignored” – referring in particular to regulations limiting coal leases, uranium drilling, and the creation of new national monuments.

But critics say that many of these decisions pay lip service to “local voices” while in reality ignoring both science and the diversity of local voices that exist.

Whitefish carpenter Tom Healy points to proposed amendments to a sage grouse conservation plan that had been written by a wide-ranging group of stakeholders but was modified by the Interior Department to reflect 11th hour concerns by ranchers and miners. The revised grouse plan – which would allow BLM administrators to bypass the original one when considering new gas and oil leases – is expected to be released soon.

The grouse plan “is the first time that an effort like that has been put together at that scale, by that many stakeholders, and not only did it look like it was going to work but it is a working model for other conservation efforts,” says Mr. Healy, who recently objected in a widely-circulated essay to being called an elitist by his neighbor Zinke. “Now that whole program is being picked apart. It doesn’t bode well for the sage grouse but it does bode very well for the corporations [that the administration] is doing the bidding for.”

And while Secretary Ross’s moves to override the decisions of federal fishery managers and expand the season for species like fluke and red snapper have been welcomed by many commercial fishermen, others worry that they undercut the established tradition of having a commerce secretary heed the advice of those managers.

“We’ve seen some recent decisions in the Southeast which ignore science, and that’s troubling,” says Holly Binns, director of the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Southeast ocean conservation work. “When science doesn’t lead the way, I think it’s risky and everyone loses out.”

Fisheries can be tricky to manage as numbers fluctuate. US fish stocks have largely rebounded in recent decades under strict management, but it is difficult for managers to trust self-reporting by fishermen of catch and bycatch – key indicators of stock health.

Since a near-collapse of the red snapper stocks in the Gulf in 2007, a plan from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that halved the quota and divided it evenly among commercial and recreational fishermen has had a dramatic impact. The fish is now so numerous that it is being found outside of its native ranges. Yet recreational anglers overshot their quota by a million pounds last year, leading to a dramatic cut to the season this year. Fishermen fumed.

Zinke, a tall, rugged Westerner, came into his role vowing a Theodore Roosevelt vision of balancing conservation with resource capitalism, and some conservation-minded Westerners thought he would be a champion for protecting public lands. Many are now reassessing that idea.

Along with his pushes to undo regulations and shrink two national monuments have been several decisions that seemed mostly political, including what appeared to be a handshake waiver of oil exploration off Florida’s coast, made at the request of Gov. Rick Scott, a GOP Senate candidate. That left other Atlantic seaboard governors feeling that the administration’s decisions have more to do with political loyalty than science and fairness.

That was a “gaffe that he needs to address,” says Prof. Freemuth.

Still, “Western governors are talking about convening meetings on working landscapes, and what’s intriguing about that is that it’s largely bipartisan,” Freemuth says. “Democrats and Republicans both want solutions and are tired of centralized Washington decisions. That’s where you get the archetype of the rancher or the Native American who have been on this landscape for a long time, and they’re doing a kind of citizen science. That’s why the administration’s moves are timely.”

But given the stakes, he warns, “It is a profound thing if it’s not done right.”

E&E News, US Geological Survey

New signs of promise for social impact investing

Do well by doing good. You’ve heard that aspirational investing formula before. This piece looks at a twist: Some social bond investors are pushing governments to get better at measuring their programs’ effectiveness – not just how many people they serve.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

A new report this week delves into an important question: Can money increasingly earn an investment return while also helping to achieve social progress? In this case, the focus is on a narrow slice of that question – the rise of “social impact bonds,” or SIBs. So far, innovative projects include support for homeless youths in Australia and immigrants struggling to learn English in Massachusetts. If the social results beat certain benchmarks, the investors are rewarded by governments for essentially saving taxpayer money. If the programs don’t hit those targets, it’s the investors who are on the hook, not governments. The returns aren’t stellar compared with the risks, so this is an arena that blurs the line between investing and philanthropy. But the new report shows the promise: 10 early SIBs have paid investors back, while one failed. And SIB promoter Tracy Palandjian in Boston says the efforts are changing mind-sets by prompting governments and social service providers to do more measuring of results for everyone from homeless people to prison inmates. “The mind shift is our proudest accomplishment.”

New signs of promise for social impact investing

It started with a simple premise: Private investors could help reduce the rate at which released British prisoners commit new crimes.

Seven years later, the recidivism project at Peterborough Prison stands as a success. Its intensive work with male prisoners who serve less than a year offered help with housing, training and employment, parenting, substance abuse, and mental health. It reduced recidivism by 9 percent among 2,000 prisoners, saving the British government enough money in prison and other costs that the investors who funded the experiment got a 3 percent annualized return over five years.

Since then, the mechanism behind this success story – known as pay for success or a social impact bond (SIB) – has spread to 24 countries, according to a report released this week by Social Finance, a nonprofit that sets up such bonds. So far, private investors have funded 108 projects aimed at saving governments money with innovative projects serving everyone from homeless youths in Australia to parents in need in Germany to blind people in Cameroon.

It's a novel idea with big potential implications, but also relatively new, and its success depends on how one counts. The new report sheds light on the progress SIBs are making. The investors – typically institutions and wealthy individuals who want their money to have a social impact – have been paid back in 10 of the 27 projects that have wrapped up, according to the Social Finance report. Just one project failed (a New York City recidivism effort), and 16 others have not made their results public. [Editor's note: The number for finished projects has been updated from the original version of this paragraph.]

For governments and social-service providers, even failures can provide valuable insights. And since private investors foot the initial bill and only get paid back if the project saves taxpayer money, SIBs allow them to experiment without risking government funds.

The most important impact of SIBs, however, may be a shift in thinking.

“We’ve really begun to change the way [our partners] look at the world,” says Tracy Palandjian, chief executive officer and co-founder of the US arm of Social Finance, based in Boston.

Because SIBs require metrics of success to determine whether investors should be paid, they are causing governments, social-service providers, and social-minded investors to change their focus from the number of people they’re serving to the effectiveness of those programs, she says. “The mind-shift is our proudest accomplishment.”

It is also quite rare, at least in the United States. In a 2013 article for The Atlantic, former government officials Peter Orszag and John Bridgeland wrote that they were flabbergasted when they calculated that less than $1 of every $100 of government spending was “backed by even the most basic evidence that the money is being spent wisely.”

The idea of wiser spending can attract politicians from across the political spectrum. In Britain, the groundbreaking Peterborough SIB was initiated under a Labour government, carried forward by a coalition government, and has earned kind words from Prime Minister Theresa May's Conservative Party, says David Robinson, chair of the Peterborough program for the British arm of Social Finance. “What I hope will be the long-term outcome is that government performance does improve.”

Here in the United States, the spirit also has been bipartisan. In Massachusetts, for example, SIBs initiated by former Democratic Gov. Deval Patrick have been taken up by his successor, Republican Gov. Charlie Baker. This past June, as the national debate heated up over immigration, Governor Baker and Social Finance announced a new program to help improve immigrants’ reading skills and provide them with job training in six Massachusetts cities.

Not everyone’s a fan, and even at their best SIBs won't be the answer to every social problem.

When the Maryland Department of Legislative Services looked into the feasibility of an SIB to reduce recidivism, it concluded: “Even when using a set of highly optimistic assumptions, it is clear that pilot reentry programs cannot self-finance their operations. Because pilot programs cannot create a large enough reduction in demand to close a facility, the cost dynamics are driven by much smaller marginal cost savings.”

Even several of the successful SIBs come with caveats for investors. They used multiple targets, some of which were met and paid investors a return. Other targets were not met and did not pay out.

And while some SIBs offer a sizable return – an ongoing Australian program to reunite institutionalized kids with their families paid out 8.9 percent per year in its first two years – returns are often quite small versus comparable investments. SIBs typically come with a much higher risk of losing one’s capital than traditional bonds, so their appeal is mainly to so-called impact investors, who are willing to accept a less generous risk/reward profile.

Even successful SIBs don’t always change minds. The Peterborough project, for example, which officially launched the SIB movement, was cut short so that a national prison reform could be implemented. The reform didn’t embrace the lessons that the Peterborough project had uncovered about recidivism, says Mr. Robinson. Under the reforms, “the rehab work that has been done by the contractors is tiny or nonexistent.”

In Britain, which has hosted more SIBs than any other country, momentum has slowed. In 2015, the country initiated 15 of them. In the following two years, it averaged only five a year. Social Finance blames the slowdown on the government, which has establishment a bureaucracy to deal with the projects, which means more consistent vetting of new projects, but which has also slowed down the pace of approvals.

SIB proponents are quick to point out that the bonds can’t substitute for government funding. They only allow government experimentation and close tracking of results. Also, they’re not the proper tool for all social problems.

“It's a work in progress,” says Ms. Palandjian of Social Finance. “It's one of the many tools in a toolbox for governments to use.”

Still, investor interest remains strong. "We are looking to do more pay for success projects on a national level," Miljana Vujosevic, director of impact investments at Prudential Financial, writes in an email. Since investing in the Massachusetts SIB for immigrants, the investment firm has invested or provided grants to other foundations and funds involved in SIBs.

Why Israeli plan to deport Africans faces Jewish opposition

This piece offers a powerful look at self-identification, at how one culture views others, and at the value of staying true to deeply held values even when they’re tested by very real "pragmatic" concerns.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel, rejecting criticism of his government’s plans to deport nearly 40,000 African migrants, referred to them this week as “illegal labor infiltrators.” It’s an argument that echoes other anti-immigration leaders facing the world’s largest flood of refugees since World War II. But most of the migrants, who began arriving in Israel in 2005 from Sudan and Eritrea, are seeking asylum. And the prospect of their deportation is increasingly posing a moral dilemma for Jews in the Diaspora and in security-conscious Israel, which, say commentators, sees itself as a refuge for Jews, but not for others. Alongside the nascent Israeli opposition to the government plan are Diaspora Jews who recall their own families’ histories as refugees and victims of persecution. Rabbi Ayelet Cohen is a senior director at the New Israel Fund, which supports social justice in Israel. “For those of us who are connected to Judaism through the Torah and Jewish religious law,” she says, “we are very aware of those religious tenets that forbid standing by when someone is at risk of death and in a place of danger.”

Why Israeli plan to deport Africans faces Jewish opposition

When Jean Marc Liling immigrated to Israel from France, he was a young man shaped by the knowledge that his Swiss parents were hidden as children during the Holocaust.

So for him, fighting against the Israeli government’s plan for the mass deportation of African asylum-seekers feels deeply personal.

Mr. Liling is among a growing number of activists here opposing the plan, which would present the country’s population of some 38,000 African asylum-seekers with the stark choice: deportation or prison.

Resistance to the government plan, scheduled to begin in April, has come from pilots refusing to fly planes used in the deportations and from authors, playwrights, lawyers, doctors, and Holocaust survivors. All are united in their call to the government to see these people as refugees in need of shelter today, just as Jews have been in past generations.

Hundreds have even volunteered to hide asylum-seekers, if it comes to that.

That prospect hits home for Liling, executive director of the non-profit Center for International Migration and Integration.

“For me, coming to Israel was really about not having to hide, being able to be completely myself as a Jew, and the thought that anyone would have to be hidden in Israel is something that is deeply disturbing and in complete dissonance to what I think Israel is supposed to be,” he says.

Nevertheless, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, echoing the stance of other anti-immigration leaders facing the world’s largest flood of refugees since World War II, this week referred to those who would be deported as “illegal labor infiltrators” and called the campaign against the deportations “absurd.”

Most of the Africans fled to Israel in a long overland journey from war-torn Sudan or from the dictatorship in Eritrea, with the first immigrants crossing the Sinai Desert from Egypt in 2005.

Jewish state's moral dilemma

The Israeli government’s stance, say commentators, speaks to a nation on the eve of its 70th birthday that has been shaped by its struggle for survival in a hostile neighborhood – a struggle that has fostered a suspicion of the “other” – and that sees itself as a refuge for Jews who are fleeing persecution, but not for others who might be.

It’s a moral dilemma for a country that in its earliest days, informed by the then-recent horrors of World War II, played a key role in formulating the 1951 Refugee Convention, the first time the international community came together to state what countries’ responsibilities were in protecting refugees.

Amid the debate over the plan, reports have surfaced that unnamed “third party” countries the Africans would be sent to (Rwanda, unofficially, and possibly Uganda) have proven to be dangerous and even life-threatening destinations. And alongside Israel’s nascent but swelling grassroots opposition to the plan, an alarm has been sounded among some Diaspora Jews who say deportation would be an egregious move that violates Jewish values and the history of a people that knows what it is to flee persecution.

They see in these African asylum-seekers a reflection of their own families’ histories as refugees and as victims of persecution, whether it was in the Holocaust or a century ago taking flight from the pogroms in the Russian Empire. They also note that Jewish tradition advocates for the protection of refugees, citing the 36 Biblical references to the commandment to “Love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

'Whiff of racism'

Nevertheless, the government is holding firm to its plans. Cabinet ministers and officials refer to the Africans officially as “infiltrators” for entering the country without authorization, and say most are economic migrants.

Most live either in South Tel Aviv, where they work mostly in restaurants, or in the southern resort town of Eilat, where they work in the hotel industry. The government has said they would bring in Palestinian workers to replace them.

They also have used the words “demographic threat” to describe the asylum-seekers, even though they number less than 1 percent of the population and their ranks are unlikely to grow – in part because of the border fence with Egypt that Israel built in response to the migration.

The deportation policy has also brought with it accusations of racism, that the urgency to kick them out of the country has more to do with the color of their skin. Even longtime Israel advocate Alan Dershowitz, the lawyer, constitutional scholar, and commentator, said in an interview with an Israeli cable television station that it was impossible to avoid the “whiff of racism” that came with deporting nearly 40,000 people of color without properly checking their refugee status first.

Israel has granted refugee status to less than 1 percent of those who have applied. By contrast, Canada has granted such status to 97 percent of the Eritreans who have reached its shores.

A Diaspora vs. Israel schism

Irwin Cotler, the former justice minister in Canada and a past president of the Canadian Jewish Congress, has been in Israel meeting with officials about the plight of the asylum-seekers.

He explains the different perspectives of Israeli and Diaspora Jews this way: “North American Jews live in a different political and cultural moment. They don’t have geopolitical and security considerations, and don’t have government coalition considerations or the urgencies of the moment living in Israel…. They come to it as people who feel genuinely concerned, if not anguished, by what is happening.”

The dichotomy is not just an Israeli phenomenon, but reflects the divergent perspectives in other countries as well, between those who identify with refugees and believe in diversity, and those who feel threatened by it.

“Israel was founded with a very deep awareness of what happens to a people when they have no place of refuge,” says Rabbi Ayelet S. Cohen, a senior director at the New Israel Fund, an American non-profit which advocates for social justice and equality in Israel. “For those of us who are connected to Judaism through the Torah and Jewish religious law, we are very aware of those religious tenets that forbid standing by when someone is at risk of death and in a place of danger.”

Rabbi Cohen was referring to testimonials collected from asylum-seekers who had already been voluntarily deported (the government has offered a $3,500 grant to those who agreed to leave) to Rwanda or Uganda. Many reportedly have been robbed, others raped, and others sold to human-trafficking rings, even facing death as they continued toward Europe on the dangerous journey through Libya.

Protections for minors

Rabbi Tamar Elad-Appelbaum, who leads a non-denominational synagogue in Jerusalem, has become active, together with Liling and others, in trying to get special protective status for those who came to Israel as unaccompanied minors a decade ago (an estimated 200 people) and were educated in Israeli schools.

They speak fluent Hebrew, are rooted here with friends and support networks, and some have even tried to enlist in the Israeli army – and when they were rebuffed, instead signed up to do national service.

She and others are working with synagogues and individuals across Jerusalem to help provide a network of support for them.

Rabbi Elad-Appelbaum says Israel has a lot to learn from Diaspora Jews, but she appeals for empathy in understanding where Israel’s official stance comes from.

“There are two points of view in our history. Jews in America have a talent for being able to look at the world and see ourselves as part of a proactive vanguard, and we in Israel for the past 70 years have been looking through the perspective of how do we make a home for Jews. Both are significant,” she says, “and we need to braid both of them together.”

On Film

‘The Insult’ crafts a credible microcosm of a religious divide

Peter Rainer tells us that what he liked best about Ziad Doueiri’s ‘The Insult’ was the same thing he liked about the director’s previous film, ‘The Assault.’ It’s his focus on ordinary people, not power players. “He gives the conflicts a human scale,” Peter says, “and he allows for many conflicting voices to speak out.” That points to a filmmaker’s belief in reconciliation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Peter Rainer Film critic

A clash between two bullishly proud men in the streets of Beirut, Lebanon, might sound like too simplistic a metaphor for modern Christian-Muslim tensions. But “The Insult” – a nominee for this year’s Oscar for best foreign language film – brings real power to the idea. Director Ziad Doueiri, a Lebanese Muslim who co-wrote the script with his ex-wife Joelle Touma, a Lebanese Christian, is not out to indict one party or the other. The film mostly plays out in the courtroom, and because of that the filmmakers’ approach can seem at times too determinedly evenhanded for such a volatile subject. But this method, which likely owes something to the religious dualism between Doueiri and Touma, is preferable to the screed that this film could have become. The film’s most telling aspect is that, as the courtroom confrontations and media frenzies heat up, both Yasser and Tony do become, in effect, minor players in a national drama. Neither disputant is glorified. And in scenes laced with nuance, they come to understand that they are more alike than they realize.

‘The Insult’ crafts a credible microcosm of a religious divide

A minor flare-up in the streets of Beirut, Lebanon, accelerates into a microcosm of the contemporary tensions between Christians and Palestinian Muslim refugees in “The Insult,” the powerful new movie directed by Ziad Doueiri that is one of five nominees for this year’s Oscar for best foreign language film.

The fracas begins when Yasser (Kamel El Basha), a Palestinian living with his wife in a refugee camp and the foreman of a Beirut construction crew, notices an illegal drainpipe coming from an apartment balcony. When the workers ask Tony (Adel Karam), the apartment’s owner and a Lebanese Christian with a loathing for Palestinians, if they can fix the pipe, he shuts them out. So Yasser goes ahead and fixes it anyway, leading to a hot exchange in which Yasser spews expletives at Tony, who then demands an apology. Both Tony and Yasser are bullishly proud men, and a forced attempt at a truce leads to a standoff in which Yasser breaks two of Tony’s ribs and culminates with a trial and an appeal that gain national attention.

In the initial trial, both men appear without lawyers. Tony believes he doesn’t need one “because I’m right.” Yasser, though admitting his guilt, nevertheless stands resolute, refusing to utter for the judge Tony’s words that led to the violence during the confrontation. Those words were, “I wish Ariel Sharon had wiped you all out,” and Yasser cannot debase himself by speaking them.

Doueiri, a Lebanese Muslim who co-wrote the script with his ex-wife Joelle Touma, a Lebanese Christian, is not out to indict one party or the other. (Doueiri has worked as a camera assistant for Quentin Tarantino and directed “The Attack,” an intriguing drama about an Arab-Israeli surgeon in Tel Aviv who discovers that his late wife was a suicide bomber.) As the film mostly plays out in the courtroom, his approach can seem at times too determinedly evenhanded for such a volatile subject. But this method, which likely owes something to the religious dualism between Doueiri and Touma, is certainly preferable to the screed this film could easily have become.

The film’s most telling aspect is that, as the courtroom confrontations and media frenzies heat up, both Yasser and Tony become, in effect, minor players in the larger national drama being played out. Their respective lawyers – Nadine Wehbe (Diamand Bou Abboud), who represents Yasser, and her father, Wajdi (Camille Salameh), who represents Tony – take center stage. (Salameh, who is like a Lebanese Claude Rains, is especially marvelous.) Tony, to Wajdi’s astonishment, doesn’t even care about any financial settlement; he just wants an apology. His wife, Shirine (Rita Hayek), whose baby is born sickly during the time leading up to the trial, possibly due to the stress, wishes Tony would just end his selfish recriminations. Yasser’s wife feels the same way about her husband, leading to the unavoidable conclusion that Middle East tensions would be a lot less tense if women were in charge – a sentimentalization, no doubt, but, given the intractability on view in “The Insult,” not so far-fetched.

Neither disputant is glorified. Yasser, with his look of grim dignity, is a marvelous camera subject, and, as played by El Basha, you can see a lifetime of suffering in those drawn features and wary eyes. (El Basha won the best actor award at the Venice Film Festival.) But Yasser, as revealed in the trial, was no angel during the Lebanese civil war that ended in 1990, a war that severely affected Tony’s childhood and adds a layer of empathy to our assessment of him. (Yasser is at least a decade older than Tony.)

Despite his Christian bona fides, Tony, who makes a point of listening to anti-Palestinian TV rants in his auto repair shop, is no saint, either. He defiantly tells his wife that he is no Jesus Christ and can’t turn the other cheek, saying, “We don’t solve this thing by pretending to love each other.” To make peace would eliminate the ferment that animates his life. And yet, imperceptibly, both he and Yasser come to understand that they are more alike than they realize. (In the film’s most felicitously funny moment, they both recognize, during the court proceedings, their strong shared preference for German-made machinery over Chinese.) There’s even a quick scene near the end in which Tony circles back to the parking lot after the trial and, with his nemesis looking on, wordlessly fixes Yasser’s nonstarting car engine. This grace note shouldn’t work, but it does. The unspoken amity, despite everything, is palpable and, even more, believable.

In the end, the film’s most nuanced summation comes from Wajdi, who says, “No one has a monopoly on suffering.” Grade: A- (Rated R for language and some violent images.)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

After mass rape, turning disgrace into grace

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

Aid workers in the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh are offering an extraordinary service to women survivors of war rape: helping them overcome the social stigma of their assaults. The women are offered medical help, of course, but just as important are the mental healing and restored dignity that allow them to better integrate into families and communities. The techniques are subtle. Survivors are offered “dignity kits” that include soap and other personal aids. Mirrors are placed on shelter walls to remind the women of their beauty. Counselors then lead the women in discussions. The goal is to replace feelings of loss, disgrace, and sadness with calmness, safety, and empowerment. Such services are relatively new in the history of conflicts with mass sexual violence. They were developed with the help of international campaigns aimed at turning such acts of terror and humiliation into opportunities to bring peace to individuals and communities – and achieve a victory over the sexual abusers.

After mass rape, turning disgrace into grace

The United Nations calls it “the most urgent refugee emergency in the world.” Since August, nearly 700,000 Muslims known as Rohingya have fled violence against them in Myanmar, a largely Buddhist nation. The sprawling camps of refugees in Bangladesh are indeed a catastrophe. Yet the crisis is becoming known for something else just as extraordinary: Aid workers are offering special services to Rohingya women because of the sexual violence committed against many of them.

The services, provided in shelters only for female refugees, assist survivors of rape and other sexual assault to overcome any shame, social stigma, or shunning. The women are offered medical help, of course, but just as important are the mental healing and restored dignity that allow them to better integrate into families and communities.

The techniques are subtle. Survivors are offered “dignity kits” that include soap and other personal aids. Mirrors are placed on shelter walls to remind the women of their beauty. Flowers and other decorations remind them of the beauty of life. Counselors then lead the women in discussions. The goal is to replace feelings of loss, disgrace, and sadness with calmness, safety, and empowerment.

The women may also be taught a livelihood. Many survivors learn to end their silence, thus reducing the culture of impunity and gender inequality, which fuels the cycle of abuse.

Such services are relatively new in the history of conflicts with mass sexual violence, such as Islamic State’s enslavement of Yazidi women in Iraq and Boko Haram’s kidnapping of girls in Nigeria. They were developed with the help of international campaigns over the past decade aimed at turning such acts of terror and humiliation into opportunities to bring peace to individuals and communities – and achieve a victory over the sexual abusers.

“Women’s bodies have always been used as battlefields,” says Dr. Helen Durham, director of law and policy at the International Committee of the Red Cross. “But we need to be clear that sexual violence in war is not something inevitable. It is preventable and we all need to work together to strengthen efforts in prosecution, prevention, and in finding practical solutions to help those affected.”

One initiative started by the British government in 2012, known as Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI), has trained thousands of security and aid workers on ways to challenge the negative attitudes associated with sexual violence. The techniques are tailored to the cultural sensitivities about women and sexual assault in different cultures and religions. In a document issued last fall called Principles for Global Action, PSVI spells out very specific recommendations. Here are two examples:

•“Reinforce directly and indirectly that all human beings have worth, and being a victim/survivor/child born of rape does not change someone’s inherent value.”

•“Ensure the definition of justice is not narrowed to legal processes and takes account of what the individual victim/survivor considers justice to be (such as reparations, re-gaining employment, community reintegration etc.).”

The idea is to be survivor-centered and reverse traditional thinking about sexual assault. Or, as Tariq Mahmood Ahmad, head of PSVI, puts it, “We must see stigma for what it is – a weapon intended to undermine and prevent social, political and economic recovery for individuals, communities and societies.”

Lifting the stigma of war-time rape is a big step toward ending the use of such a weapon altogether. At the refugee camps in Bangladesh, the women survivors seeking help are not so much victims of rape as they are now heroes of peace.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Don’t put up with contagion

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Heidi K. Van Patten

Today’s contributor shares how “turning off” the thought that sickness is inevitable by considering everyone’s real identity as God’s flawless, spiritual child brought quick healing.

Don’t put up with contagion

The 15-minute drive from my home into town winds through the woods and into hilly farmland with a glimpse of a lake. As I drive this familiar route – sometimes being quiet, and sometimes listening to music on the radio – I enjoy the scenery.

Once I was enjoying this pleasant drive when a song came on the radio that I didn’t like. I thought: “Ugh, I’ve got this beautiful day to drive, and I have to listen to this annoying music. And it will probably go through my mind the rest of the day.” It didn’t occur to me until about halfway through the song that I could actually turn the radio off!

While I had to laugh at myself, this incident made me consider how easy it can be to go along with disturbing influences that can take away our mental peace or even negatively affect our physical health, and to entertain such thoughts throughout the day. As with that song, they may begin subtly but can become more aggressive. The good news is that we have the ability to “turn off” these thoughts by turning to God and letting Him fill our consciousness with the unchanging, harmonious spiritual reality that assures our peace and health.

Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy addressed this idea when she wrote: “Stand porter at the door of thought. Admitting only such conclusions as you wish realized in bodily results, you will control yourself harmoniously” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 392).

I’ve had several opportunities to see the power of this kind of prayer in action. For example, several years ago I woke with a very uncomfortable sore throat on the first morning of a family trip. It was a beautiful day, and we had a lot of fun activities planned. But this sore throat was a bit like that annoying song in its persistence, and I was concerned it would ruin my day.

I had experienced physical healing many times before by praying. For me, praying about illness often begins with considering my true identity as God’s spiritual image, as described at the beginning of the Bible (see Genesis 1:26, 27). So I took some time that morning to better understand what it meant to be the image of God – spiritual, because God is Spirit. I realized that because everyone’s true nature is the image of God’s perfect wholeness, perfect health was my natural state of being.

This true identity is permanent – not affected by the circumstances around us. And understanding this spiritual fact inspires confidence in God’s care for us, which dispels fear of illness and gives us a powerful basis for rejecting thoughts of contagion, knowing contagion has no foundation in spiritual reality.

Praying on this basis of spiritual reality can also bring to the surface any unhelpful thoughts that perhaps we have let linger, so that we can then work toward healing them. Sure enough, as I prayed that morning, I recalled that several days prior to this, I’d distanced myself from someone else experiencing similar symptoms to what I now faced, so I wouldn’t catch anything.

I realized that simply going along with the thought that sickness is contagious and inevitable hadn’t been the best way to care for this person or myself. But how freeing it is to know that it’s never too late to change our approach. I still had the opportunity to recognize the perfection of God’s creation and perfect health as everyone’s God-given right.

I continued praying along these lines, and by mid-morning I was completely free of the sore throat and all symptoms of illness, and able to freely participate in the day’s activities with my family. The clearer understanding I gained of everyone’s true identity as spiritual and pure, not as mortals vulnerable to illness, has many times helped me to better support others, too.

Actively guarding our thinking against any contagious thoughts – whether thoughts of physical illness or influences of hate or fear – doesn’t mean just ignoring what’s going on around us. On the contrary, it means exercising our inherent awareness of the presence and power of God, and of everyone’s real identity as God’s flawless, spiritual child. And this spiritual awareness not only brings about more healing in our lives, but also makes us ready and able to help meet the needs of humanity through our prayers.

A message of love

Remembering an epic battle

A look ahead

Thanks so much for spending time with us today. Come back Monday. We're working on a story looking at how America can repair its outdated infrastructure. In Oklahoma's Grady County, they do it one leak at a time.