To hear Marc Denhartog explain it, Dutch supremacy at Olympic speedskating is more logical than extraordinary.

“There is a lot of water here, and it’s cold in winter,” he says in a typical Dutch deadpan. “When kids are young, they learn two things: swimming, which is really mandatory because you can fall in every canal around you, and in winter time, it’s ice skating."

Yet Mr. Denhartog’s appearance belies his rather mundane analysis. He is at an ice rink with his 9-year-old, who is attending a speedskating camp during a school vacation. But Denhartog is not wearing a polar fleece and thumbing through stock quotes on his cellphone. He’s in a skinsuit taking a breather from doing laps on the 400-meter track himself.

Yes, the Netherlands’ canals make speedskating a natural national pastime. But the Jaap Eden skating oval here in the middle of Amsterdam, the camp for kids during winter break, and the skinsuit-wearing middle-aged parent speak to something much more – to a genuine sporting obsession.

Why are the Dutch so good at speedskating? Why do the Germans own luge? Why do the Norwegians look down on the rest of the world in cross-country skiing?

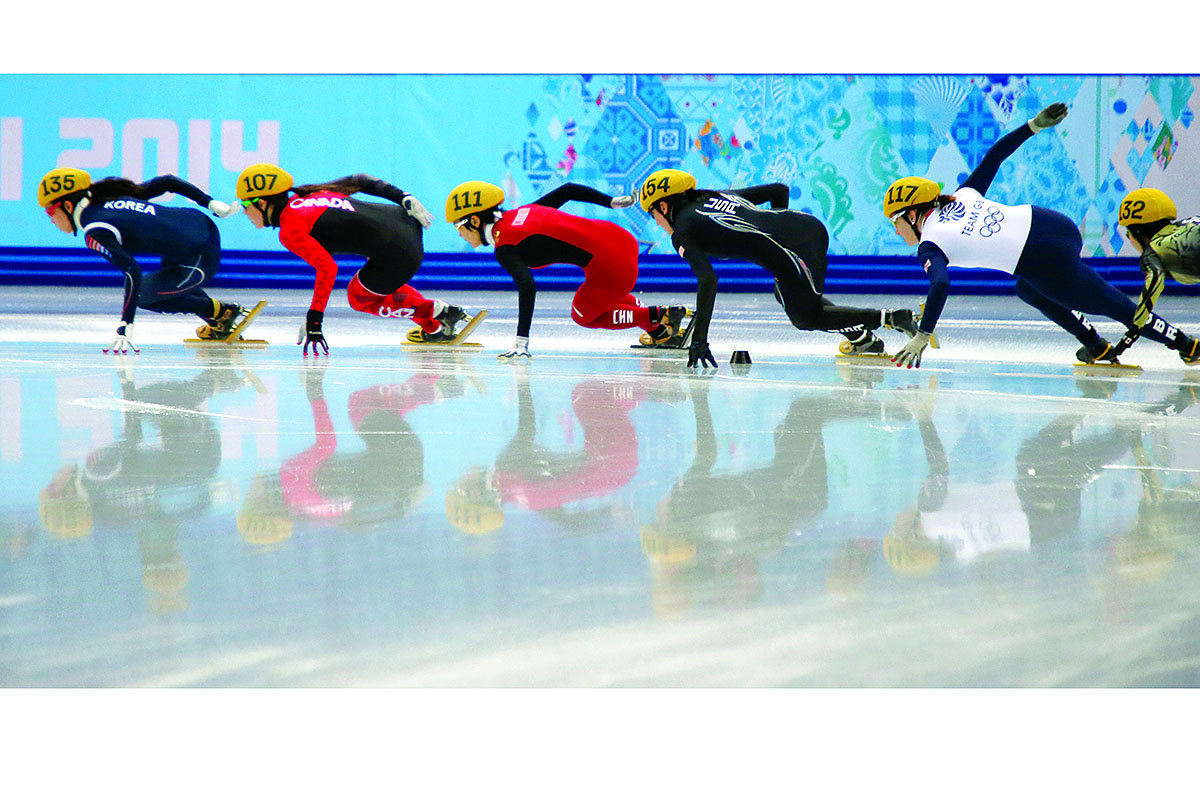

The Olympic Winter Games, which begin in Pyeongchang, South Korea, Feb. 9, are a collection of the obvious and the eclectic. America’s spirit of freewheeling individualism makes its dominance of snowboarding understandable, perhaps. But why are the South Koreans the lords of the short track speedskating rink?

The answers to why certain countries do so well in certain sports change by country and clime. South Korea’s K-pop culture loves celebrities and short track skaters are divas on switchblades – heroes or villains in the demolition derby of each hairpin corner. In Germany, the country of BMW and Porsche, the ceaseless quest to build the perfect luge sled takes on almost mystical proportions.

Olympic dominance is born of a kindling fire – a historical connection or cultural affinity for a sport that then builds on itself. A financial commitment from the national government can help. But true supremacy comes when sport and nation intertwine so closely that one becomes part of the identity of the other.

There are many examples. Hockey is a core constituent of the Canadian id. Austria justifiably sees itself as the home of Alpine skiing. The Scots were the first to glide curling “stanes” across frozen lochs.

All of which leads to a fundamental question as the world prepares to watch the best athletes on earth bedazzle with their talents in the snow-gauzed mountains of South Korea: When it comes to sports – especially Olympic sports – is culture destiny?

* * *

The deepest connection between a country and a winter sport almost certainly is that between Norway and cross-country skiing. The biathlon – which combines cross-country skiing and riflery – evolved out of combat exercises in the late 1600s. To this day, Norwegian conscripts are still required to learn how to ski and shoot as part of mandatory military service.

But cross-country also defines something more in the Norwegian character. In the late 19th century, it was a prominent expression of Norwegian nationalism. As the country pressed for independence from Sweden, its explorers pushed northward toward the North Pole – conspicuously, on skis.

Fridtjof Nansen, who was the first to cross Greenland’s interior and at one point had traveled farther north than any human in recorded history, “was very conscious about using his skis physically and symbolically,” says Åslaug Midtdal of the Norwegian Ski Museum, the world’s oldest such institution, in Holmenkollen.

Cross-country skiing originated with the Vikings as a form of transport and a way to hunt. In 1206, amid the Norwegian civil war, legend has it that a group of rebels derided as being so poor that they wore birch bark on their feet – the Birkebeiners – carried an infant to safety over mountains by ski from Lillehammer to Trondheim. The infant would grow up to become King Haakon Haakonsson IV, who ended Norway’s civil war and became renowned across Northern Europe.

“Vikings were very good skiers,” says Ms. Midtdal. “The landscape made it impossible for them to travel without skis.”

This March, thousands of Norwegians will re-create the historical trek in the slightly shorter 54-kilometer Birkebeinrennet cross-country race from Rena to Lillehammer for the 80th time.

It is only one example of how deeply winter sports can be sewn into a nation’s history. For the Dutch, skating can be traced like a thread through the centuries. It is thought that the modern iron-bladed skate was first developed in the Low Countries in the 13th century – a revolutionary means of transporting both goods and people along the icy canals.

Four centuries later, Dutch rebels on ice skates so befuddled imperial Spanish forces during the Eighty Years’ War that the Spanish crown reportedly ordered 7,000 of its own pairs of ice skates and offered its soldiers skating lessons. “It was a thing never heard of before today to see a body of musketeers fighting like that on a frozen sea,” a Spanish duke said at the time.

Alas, Spain is still waiting for its first Olympic medal in long track speedskating. The Dutch have won 105 – a full 25 more than No. 2 Norway.

Marnix Koolhaas, a Dutch skating historian and former trainer, says skating took hold as a pastime after the Reformation. As Calvinism spread, the revelry associated with Carnival, an annual Christian celebration that lasted several days, diminished. “It got transferred to the ice, as the place for joy and fun,” says Mr. Koolhaas.

Ice became a great equalizer. The strict divisions between class and religion didn’t apply. When Dutch skating clubs were founded, they were always neutral, unlike Roman Catholic soccer clubs. “If you were a poor guy but a good skater, you could ask an upper-class girl to skate with you and have fun during ice time,” he says.

Skating had its heyday in the 17th century, during the Dutch golden age, and was often captured in winter landscapes of the period. “In a way, foreigners look at the Dutch population and say they are so free in many ways,” says Koolhaas, noting the liberalism that defines Dutch society. “I think the root of that kind of freedom is based on what happened since the 17th century on the ice.”

It’s a dreary day in the central German town of Winterberg. Snow is falling thickly, roads are slippery, and visibility is poor. So, of course, the luge track is packed.

For the states of Hessen and North Rhine-Westphalia, today is the day scouts will be looking for new talent. And more than anywhere else in the world, the talent has come out in numbers appropriate for a country captivated by careening on a small sled down a serpentine, iced trough.

“A lot more children came than expected,” says Caroline Theelke, the luge youth coach for the two states. “At first, we talked about 20 [coming]. Then a lot more signed up and we set the limit at 50. Now it’s even more, despite the difficult weather conditions.”

At the Olympics, luge is completely, utterly German. And this day in Winterberg is proof. Since the addition of luge to the Winter Games in 1964, Germans have won 31 of 44 gold medals, and 75 of the total 129 medals. Put another way, Germany has won more medals than the rest of the world combined – and it’s not particularly close.

Take Robin Geueke and David Gamm. The two young men won bronze at last year’s doubles World Cup race in Pyeongchang, regarded as a major test for the coming Games. But they won’t be competing at the Olympics. The Germans can only take two teams, and, even though Geueke and Gamm are ranked No. 4 in the world, they are No. 3 on the German team.

Perhaps it’s the German penchant for velocity. There’s a poetry to one of the Olympics’ fastest sports – with sleds skimming 90 miles per hour down the track – being dominated by a country that has no speed limits on many highways.

Or perhaps it’s German engineering, dedicated to its mantra of Vorsprung durch Technik, “advancement through technology.” When luge legend Georg Hackl was preparing for the Games in Salt Lake City in 2002, where he hoped to win his fourth straight gold medal in the men’s singles, Porsche designed his sled. Outside Berlin, the German government funds a semi-secret Soviet-era research institute dedicated to honing and improving the equipment of Germany’s Olympic athletes.

“Yes, it’s all very German,” Harald Schaale, the institute’s director, told Reuters in 2014. “Engineers everywhere look at how science can improve how things work. It’s possible Germans are a bit more obsessed about it than others.”

Or maybe all these things just came together at a unique time and place to create something new – a luge tradition that didn’t exist before the 1960s. After all, only 16 luge tracks exist in the world, four of which are in Germany.

“The different locations in Germany also compete against each other,” says Gamm, the doubles luger who will miss out on Pyeongchang. “Material and new training principles are tested and new talents can be scouted at four sites simultaneously. And in the end, only the best prevail.”

This is the power of the Olympic Games to create a winter sports tradition, and it will also be on display this year in the host nation, South Korea.

Four years before short track speedskating officially entered the Olympics, Korea was hardly a superpower. In 1988, when short track was just a demonstration sport, the country finished on the podium only twice. Since 1992, however, South Korea has been on the short track podium more than any other country – 42 times, compared with No. 2 China’s 30.

In short, Korea saw an opportunity, and state planners seized it. After 1988, “Koreans ... were determined to make it their own,” wrote the Chosun Ilbo, a Korean newspaper, in 2006, noting that Koreans, “with their relatively small figures,” were perfectly suited for the small oval track.

Zealous government planning is hardly new to Seoul. “Physical fitness is national power” was a mantra of Park Chung-hee, South Korea’s dictator from 1961 to 1979. His government, and the administrations that succeeded it, saw their role as selecting national champions in business, the arts, and sports.

Cho Ha-ri, a 2014 Olympian, was in first grade when an instructor spotted her. She was admitted to the Taereung Training Center – a pipeline for elite athletes set up by the government in northeastern Seoul – where she lived 11 months a year for 23 years. “I’d wake up at around 4:30 a.m., skate from 6 to 8, and have breakfast,” she says. “From 10 to 12, I’d weight train. After lunch and a short break, from 1:30 or 2, I’d train more until 6 and then have dinner. And there’s a night training for about an hour.”

Her road to success, far from glamorous, was a journey through peril and hardship toward single-minded mastery. There’s a Korean appeal there, she says. “It’s the type of sport that requires one to persevere until the very end,” she adds. “I think there’s a sense of perseverance unique to South Koreans.”

Yet at the end, for the very best, there is also glamour. “In Korea, it’s personality driven,” says Olympic historian David Wallechinsky. “The people become role models, and it’s a self-perpetuating thing.”

This in a nation where sport is tied to ethnic pride – where a belief lingers that all Koreans, whether from the North or South, come from a superior bloodline called the minjok. “I think South Koreans generally have better, quicker reflexes than Westerners,” says Kwon Sung-ho, professor of physical education at Seoul National University.

* * *

Domination in a sport often confirms national characteristics that a people cherish in themselves. For the United States, think freedom, individualism, and innovation. In other words, think snowboarding.

In truth, the Winter Olympics’ entire freestyle revolution – turning from austere timed events to those judged by tricks – has heightened American influence on the Games. The US was generally a Winter Olympic also-ran until the 2000s, when the explosion of X Games-style sports gave it a medal table jolt.

“What drew me to halfpipe and aerials more than anything else was the fact that there weren’t any rules – you could do it however you wanted, and as long as you made it look good, it would get the respect of both competitors and the judges,” said David Wise, a freestyle skier, at an Olympics media event late last year.

Others take a more conservative approach, doing the same tried-and-true runs in a quest for wins. “I want to win, but I want to do something new more,” he noted.

“It’s an American thing. The pioneer. And that’s why I love to use the term pioneer. Because America is about pioneering,” he added. “And honestly I think that’s why our team has been traditionally so successful in free skiing and snowboard....”

He’s certainly right about the success: America has won 24 medals in snowboarding – twice as many as second-place Switzerland. And there are 10 snowboarding events on the program for Pyeongchang, as the program keeps growing.

It’s been 20 years since a brash band of Americans in baggy pants first invaded the Olympic slopes at Nagano, Japan. Those inaugural riders, distinguished by their free spirits and irreverent attitudes, did more than captivate crowds at the Games. They helped breathe youthful vitality into a Winter Olympic movement that for years has struggled to grow its geographic appeal and relevance.

“Snowboarding is not a team sport,” says DJ Jenson, a former Burton Snowboards senior vice president. “These athletes have unique personalities and train in different locations rather than one place like members of other teams do. They take pride in competing for their country but so much is about self-expression, individuality, and creativity. That’s what makes it so much fun to watch.”

Even snowboarding’s origins are quintessentially American. Depending on whom you believe, the first snowboard was either a “snurfer” (snow surfer) invented by a Michigan man in his garage on Christmas Day 1965, or a “bunker” board patented by a Minnesotan in 1937.

While Americans may brandish their individuality in the halfpipe and big air, Russians showcase a different national characteristic every four years in another realm – on ice. The sense of grace evident in the Bolshoi and Mariinsky is manifested in the country’s figure skaters. Russia has not necessarily dominated the sport: The 55 total medals of the Soviet Union, Russia, and 1992’s Unified Team just barely top America’s 49. Yet the success the country has had in figure skating is rooted in elements of Russian culture and cunning – the beauty of ballet allied with the might of a state sports machine.

Since pairs figure skating was introduced in 1964, Russian or Soviet skaters have won gold an astonishing 13 of 14 times. Their record in ice dancing is only slightly less impressive, having won seven of the 11 gold medals since the event began in 1976. Between the two events, the Russian/Soviet team accounts for 38 of 75 medals awarded.

Now with Adelina Sotnikova’s gold in the women’s singles in Sochi – remarkably, the first for Russia in the event – the country is beginning to expand its footprint. “In Moscow, figure skating is so popular that parents stand in lines, sometimes overnight, to register their children with a top trainer,” says Olga Ermolina of the Russian Federation of Figure Skating.

After the Soviet Union collapsed, Russian sports foundered. The nation’s legendary figure skating trainers fanned out across the world, where they made a living teaching others. But after Vladimir Putin came to power, resources began to flow back into national sports.

Three-time Olympic pairs champion Irina Rodnina, for example, returned to Russia from the US and was elected to successive terms in the State Duma, where she currently oversees sports policy for the pro-Kremlin United Russia party. “There was a time when trainers were leaving Russia en masse, but not anymore,” says Oleg Shamanayev, deputy editor of the Moscow newspaper Sport-Express. “Now trainers are spoiled for choice: We have really good schools, and are strongest in female skating.”

Russia’s Olympic collapse reached its nadir at the 2010 Vancouver Games, where Russian figure skaters didn’t win a single gold medal, managing just one silver and one bronze. With Russia set to host the next Winter Games in Sochi, the Kremlin was determined to turn things around.

That effort has become notorious, involving an unprecedented doping operation that has seen Russia banned from the Pyeongchang Games. But Russian athletes who prove they are clean can compete under the Olympic flag, and that could include Team Russia’s figure skaters.

“There are very few cases of doping in this sport, if only because there are no drugs that can help achieve better results in figure skating,” says Mr. Shamanayev.

* * *

One thing that can be said for certain – from Sweden to Saskatchewan – is that success breeds success.

The recipe for Winter Olympics domination is the scene in Amsterdam – a parent passing a passion on to a child – repeated countless times across a country. “Around 4 we start them on ice hockey skates,” says Denhartog. “But we like to have them start early with the longer skates. Because that’s for us the real skating.”

And despite all the Dutch ice skating ovals, nothing quickens the pulse like seeing ice on the canals. “In the winter, we get crazy around it. We follow the news, follow the ice thickness,” he says. “When it’s a good night, you will take the morning off with your friend for ice skating.” (He is adamant that any Dutch boss would understand.) The holy grail is the Elfstedentocht, a 120-mile canal race that connects 11 cities in the northern province of Friesland when conditions are cold enough.

The scene repeats itself by the luge tracks of Germany. A mother from Schmallenberg has just watched her 8-year-old son race down the track at 34 m.p.h. “Well, I’m a bit worried about the constant driving, but if he wants to pursue it, we will support him,” she says. “I mean, if you’re from the region, you automatically foster an affection for the sport.”

Other Germans agree. “Our youngest start at the age of 5,” says Ms. Theelke, the youth coach. “This means if they make it all the way to the top they already have a lot of experience, a lead of hundreds or maybe even thousands of races.”

In Norway, cross-country skiing is ingrained in everyday life. Many Norwegians have access to a family ski cabin in the mountains. Urban dwellers in Oslo have only a short train ride to get to free prepared trails just outside the city. Norwegian youth are exposed to cross-country skiing at day care and primary school and through 1,150 local ski clubs.

“I went to and from school on skis,” says Pål Rise, a cross-country education consultant with the Norwegian Ski Federation. “That culture still lives in Norwegians.”

In the end, as the Winter Olympics unfold in South Korea, the world will be watching more than a clash of extraordinary athletes. It will be witnessing a collision of cultures and histories: German precision and Russian elegance, American individualism and Korean perseverance, the legacy of skating musketeers and Norwegians in birch bark boots.

(Contributing to this report were Sara Miller Llana in Amsterdam; Valeria Criscione in Oslo; Felix Franz in Winterberg, Germany; Geoffrey Cain with Jieun Choi in Seoul, South Korea; Fred Weir in Moscow; Todd Wilkinson in Bozeman, Mont.; and Christa Case Bryant in Park City, Utah.)