- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- With cake-shop ruling, high court urges respect for both sides

- Behind Trump’s bold stance on the scope of presidential power

- For Nigerians displaced by Boko Haram, lure of home comes with risk

- Why the world comes together over an improbable Colombian reef

- Mall? Utility? Internet metaphors matter in net neutrality debate.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for June 4, 2018

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Jin Park has a message for you: Your talents are not really your own. The graduating Harvard senior said as much during the university’s recent commencement ceremonies.

“Our particular positions within the web of society come to us most of all through fortune, not desert,” he said. Therefore, he added, “we must think about our talents as a collective asset.”

The comment captures the thought radiating from many college campuses today. Privilege is a fraught topic, economically and racially. One tendency can be to think of it in a zero-sum way – that advancement takes from one to give to another. By that reckoning, “collective” thinking sometimes sounds like just making everyone average.

But that’s not really what Mr. Park was saying. When we realize that so much of our success is built from good beyond our control – be it loving parents, a stable community, or dedicated teachers or mentors – we realize that that good is greater than us, and we have just had the fortune to share it. This turns that zero-sum equation on its head. Goodness, when shared, grows. Free market capitalism essentially operates on that principle.

By that reckoning, one of the most powerful questions anyone can ask, Park said, is not “What am I going to do with my talents?”; it is “What am I going to do for others with my talents?”

Here are our five stories for the day, which look at the political value of home, an improbable natural wonder, and the power of language.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

With cake-shop ruling, high court urges respect for both sides

The careful calibration of Monday's US Supreme Court ruling in the Masterpiece Cake Shop case resulted in no sweeping decision. Instead, it "invited us all to turn down the heat in the culture wars," says one legal scholar.

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

The US Supreme Court today ruled in favor of a Colorado bakeshop owner who had been punished for refusing to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. Both parties – Jack Phillips, the bakeshop owner, and the Colorado Civil Rights Commission, which enforces the state’s anti-discrimination law – warned of the dire consequences of a broad decision favoring either side. The court’s 7-to-2 decision limited itself to Mr. Phillips’s case, siding with the baker but reaffirming the broader right of states to prohibit discrimination against LGBTQ people. The narrow decision represents the high court’s latest attempt to navigate tensions between the rights of same-sex people to marry and the religious freedom rights of individuals who may object to such marriages. Support for the decision – albeit lukewarm – from left-leaning Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan and the American Civil Liberties Union, which represented the same-sex couple, suggests a way for states to successfully balance those tensions moving forward, experts say. “This doesn't change the ability of states to protect their vulnerable citizens in any way,” says law professor Craig Konnoth. “What it might do is make people a little more careful in how they talk about these issues, and I think being careful about the way you talk about delicate issues is a good thing.”

With cake-shop ruling, high court urges respect for both sides

The US Supreme Court today ruled overwhelmingly in favor of a Colorado bakeshop owner who had been punished for refusing to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple.

Both parties in the case – Jack Phillips, the bakeshop owner, and the Colorado Civil Rights Commission, the agency that enforces the state’s anti-discrimination law – warned of the dire consequences of a broad decision favoring either side. So did many of the more than 100 friends of the court who filed supporting briefs. The court’s 7-to-2 decision Monday limited itself to Mr. Phillips’ case, however, siding with the baker but reaffirming the broader right of states to prohibit discrimination against LGBTQ people in the marketplace.

The narrow decision represents the high court’s latest attempt to navigate tensions between the rights of same-sex people to marry and the religious-freedom rights of individuals who may object to such marriages. Support for the decision – albeit lukewarm – from left-leaning Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan and the American Civil Liberties Union, which represented the same-sex couple, suggests a way for states to successfully balance those tensions moving forward, experts say.

“This doesn’t change the ability of states to protect their vulnerable citizens in any way,” says Craig Konnoth, a professor who studies the intersection of sexuality and the law at the University of Colorado, at Boulder.

“What it might do is make people a little more careful in how they talk about these issues,” he adds, “and I think being careful about the way you talk about delicate issues is a good thing.”

Turning down heat in culture wars?

The case dates back to July 2012, when Charlie Craig and Dave Mullins, recently engaged, walked into Phillips’ cake shop in a Lakewood, Colo., and asked for a cake for their wedding reception. Phillips said that, while he would be happy to make them other products, he did not sell baked goods for same-sex weddings.

Two years later the Colorado Civil Rights Commission, which enforces the state’s anti-discrimination law, ruled that Phillips had violated the law and ordered him to either sell cakes for same-sex weddings or not sell wedding cakes at all. Appealing the decision, Phillips said he felt forced to choose between his religious beliefs and his life’s work.

The Supreme Court’s decision essentially rules that while states are allowed to apply neutral and generally applicable nondiscrimination laws to business owners and other actors in the economy, they cannot do so in a way that shows hostility to religious views.

When the commission heard Phillips’ case, it did show hostility, the high court ruled. Specifically, the majority opinion – written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, the court’s swing vote and the author of the 2015 Obergefell decision that legalized same-sex marriage – focuses on statements from the commission indicating hostility toward Phillips’ faith-based argument. Noting that one commissioner compared the baker’s argument with religious defenses of slavery and the Holocaust and that another described faith as “one of the most despicable pieces of rhetoric that people can use,” Justice Kennedy wrote that when the commission considered the case “it did not do so with the religious neutrality that the Constitution requires.”

Significantly, Justice Kennedy added that “the outcome of cases like this in other circumstances must await further elaboration in the [lower] courts.”

Overall, he continued: “These disputes must be resolved with tolerance, without undue disrespect to sincere religious beliefs, and without subjecting gay persons to indignities when they seek goods and services in an open market.”

In the opinion of John Corvino, dean of the Irvin D. Reid Honors College at Wayne State University in Detroit, that means that the justices “punted in a way that was instructive.”

The decision “didn't settle the hard questions, but it acknowledged that there are indeed hard questions here and that we won't do a good job of addressing them if we're too quick to label either side as ‘despicable,’ ” added Professor Corvino, co-author of the book, “Debating Religious Liberty and Discrimination,” in email to the Monitor.

“In doing so, it invited us all to turn down the heat in the culture wars – a result I very much welcome.”

When it comes to anti-discrimination law, “the biggest single principle ... is that no one is turned away,” said Robin Fretwell Wilson, law professor at the University of Illinois College of Law in Champaign, speaking of the “dignitary harm of being told, ‘No, not you here.’ ” That said, she added in an interview before Monday's decision, “that does not tell you who bakes the cake. That only tells you that the business serves a person.”

“I personally think that anti-discrimination law can cotton, can allow room for a religious objection to the very thing being protected.”

Lingering tension

The ruling itself is narrow and incremental, but in the context of the national tension between LGBTQ rights and religious freedom there are wins for both sides.

“This is a big win for the religious liberty of all Americans, including Americans who believe that marriage unites a husband and wife,” said Emilie Kao and Ryan Anderson, of the conservative Heritage Foundation, in a statement.

“As the court also noted, ‘religious and philosophical objections to gay marriage are protected views and in some instances protected forms of expression.’ ”

But, Ms. Kao added, “This is a big deal not just for social conservatives, but a big deal for all Americans, that all the Supreme Court is saying is that there needs to be mutual respect, respect for both sides.”

Meanwhile, for James Esseks, director of the ACLU’s LGBT & HIV Project, Phillips “won the battle but lost the war.”

The decision doesn't mean that Phillips, or anyone else, is now allowed to not sell wedding cakes to gay couples, he said in a conference call with reporters, so “on the big issue the bakery was pushing on this case, getting a constitutionally based license to discriminate, they did not succeed."

“We read this decision as a reaffirmation of the court’s longstanding commitment to civil rights protections and the reality that states have the power to protect everyone in America from discrimination," he added.

That tension – states being allowed to prevent discrimination but individuals also being allowed to object to it – has not been relieved by today’s opinion, however. When are objections justifiable, for example? How can state anti-discrimination laws protect citizens without constricting the free exercise of religion?

With similar cases percolating in the lower courts, the Supreme Court is likely to have to address those questions in the future. (One similar case, involving a florist who refused service to a same-sex couple in Washington, could be heard next term.) The four separate opinions in this case authored by various justices, suggest those questions could be challenging to answer.

Justice Kagan wrote a separate concurrence, which Justice Breyer joined, elaborating on why they agree that states are allowed to prohibit discrimination in the marketplace so long as state actors don’t “show hostility to religious views.” The concurrences from Justice Gorsuch and Justice Thomas, meanwhile, argued respectively for why Phillips should have his case re-heard by the commission – potentially setting the case up for a return to the Supreme Court – and why Colorado’s anti-discrimination law also violated his free speech rights, with Thomas saying that wedding cake-making is constitutionally protected “expressive conduct.”

Those disagreements don’t even account for the dissent written by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, which agreed with much of the majority opinion but argued that the court should have sided with Mr. Craig and Mr. Mullins.

This context makes Kennedy’s plea for a civil and respectful discussion of these tensions all the more important, experts say.

“The court is saying: This is an important conversation to have, but dammit we’re going to have a respectful conversation, and if we don’t have a respectful conversation we’re going to put it off. And I think that’s tremendously important,” says Mark Aaron Goldfeder, senior fellow at Emory Law School’s Center for the Study of Law and Religion.

“This is a balancing test,” he adds. Equality for the LGBTQ community and the free exercise of religion “are all valid rights and they all deserve to be listened to, and that’s why it was so hurtful what the Colorado Commission did, which was almost to pretend there wasn’t another side to this question.”

And in addition to essentially requiring all sides of this issue to not demonize another, Professor Goldfeder continues, today’s decision also narrows the issue down to one specific, albeit complex, question: “How does a tolerant society balance values at tension with each other without disparaging either side?”

•Staff writer Harry Bruinius contributed to this report.

Share this article

Link copied.

Behind Trump’s bold stance on the scope of presidential power

President Trump has said that he has the right to pardon himself. The statement shines a light on how much has changed in politics since the last time a president made similar bold claims.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In recent days President Trump and his lawyers have insisted that the powers of the presidency are pretty expansive. The president can pardon himself, according to Mr. Trump. He can’t obstruct justice. He doesn’t have to talk to special counsel Robert Mueller. The last president to have such a sweeping view of the presidency? Richard Nixon, who said, “When the president does it, that means it is not illegal.” Things didn’t turn out well for President Nixon, of course. But Trump may be insulated from the political ramifications of his opinions and actions in a way Nixon was not. He’s more popular than ever with Republican voters. He’s got a GOP-controlled Congress (for now). Perhaps most important, he’s got Fox News, Sean Hannity, and an organized conservative media. “What Trump has is the ability to reach 30 to 40 percent of the electorate in an unmediated way,” says Brian Balogh, a University of Virginia history professor and co-host of the Backstory history podcast.

Behind Trump’s bold stance on the scope of presidential power

In recent days President Trump and his lawyers have made sweeping assertions about the powers of the presidency, describing a US chief executive unconstrained by political limits accepted in Washington for over 40 years.

The president can pardon himself, according to Mr. Trump. By definition, he or she cannot obstruct justice. The president doesn’t have to talk to special counsel Robert Mueller, even if Mr. Mueller sends the White House a subpoena. The very existence of the special counsel is unconstitutional, Trump claimed on Monday in a tweet.

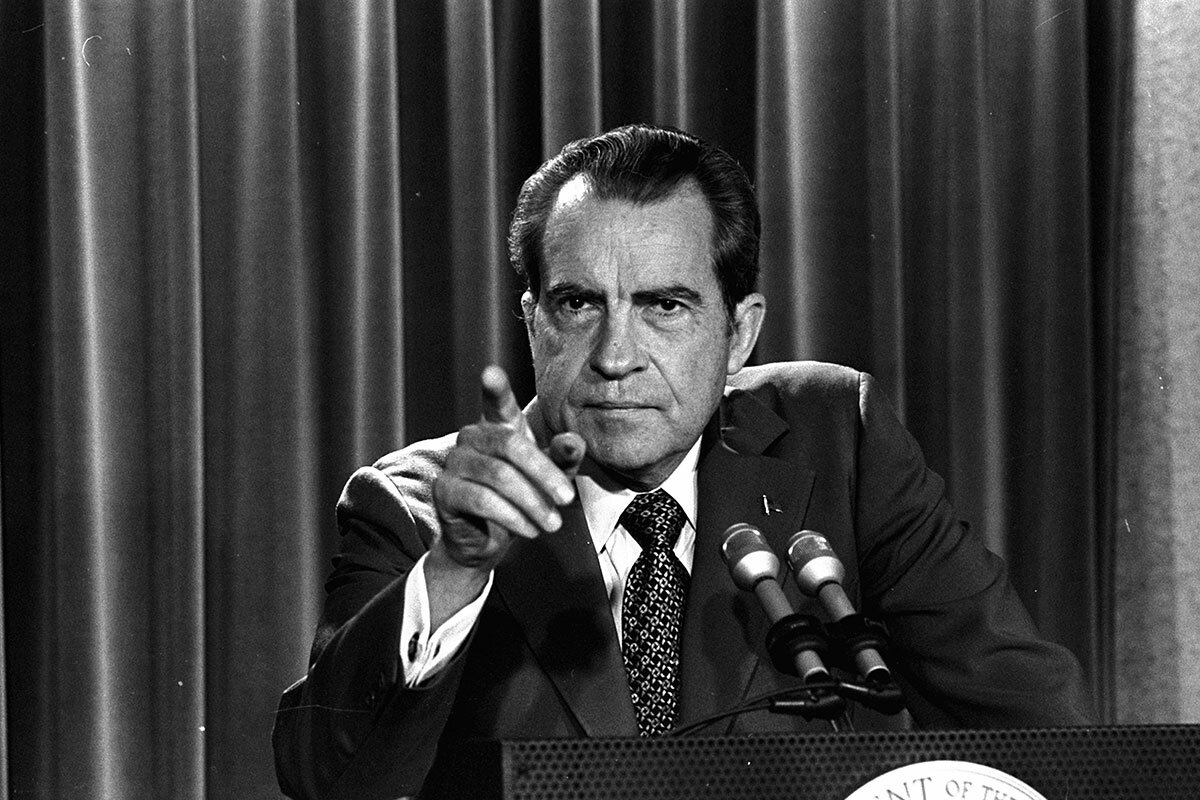

It’s an argument concerning authority that sounds a lot like the one made by Richard Nixon. Famously, Mr. Nixon once told a TV interviewer that, “When the president does it, that means it is not illegal.” The executive branch controls the law, so it is the law. One follows the other. Or so the position goes.

That didn’t work out well for Nixon, of course. He made the “not illegal” comment after Watergate had already forced him from office. And many legal experts don’t accept the details of this position. Self-pardoning, as a power, is hotly debated today.

But Trump is in a very different political environment than was Nixon, and his assertions of authority, grounded in reality or not, may reflect that. He is insulated against the consequence of impeachment in a way Nixon never was. One big reason is the rise and reach of activist conservative media. By asserting sweeping powers, perhaps Trump can bolster his electoral defenses, convincing supporters that the Russia investigation and related attacks on him are illegitimate.

“What Trump has is the ability to reach 30 to 40 percent of the electorate in an unmediated way,” says Brian Balogh, a University of Virginia professor and co-host of the Backstory history podcast. “That allows him to push back on Mueller and others.”

In some ways Trump’s is an insulated presidency. That’s easy to miss in Washington, where news alerts on the latest turn of the Mueller case can ping on cell phones across a restaurant dining room, sounding an electronic chorus of media obsession.

But crucially, Trump enjoys solid support from his own party’s voters. A new Gallup poll shows that at 500 days in office he maintains the second-highest “own party” job-approval rating of any president since World War II, behind only George W. Bush (who was boosted by the 9/11 terrorist attacks).

Trump’s approval over time has been very stable, even unusually so, says Nathan Kalmoe, an assistant professor of political communication at Louisiana State University. Political polarization is a big reason for that – his popularity with Republicans contrasts with deep unpopularity among Democrats, and negative ratings from independents.

Also, most voters don’t react to the news alert pings. They make electoral judgments on the state of the economy, how long the incumbent party has been in power, and other general factors.

And support from GOP voters translates into support from GOP politicians in Congress. Republicans control both chambers, for now. While they may lose the House in November, it would take a huge wave for Democrats to retake the Senate.

“President Trump would not be impeached or removed by this Congress given what we know now, and I doubt there would be enough votes in the Senate next year to remove him from office even with Democratic majorities, unless the Mueller investigation reveals some major new evidence implicating Trump personally,” says Dr. Kalmoe by email.

After all, impeachment is not a legal process. It is a political one. Nothing about it is automatic. Mueller’s findings, whatever they are, won’t be a machine setting a congressional impeachment finding in motion. And after impeachment in the House, a two-thirds Senate majority is needed to convict.

“A president might do all kinds of inappropriate things, but if members of Congress don’t want to impeach the president, the president won’t be impeached,” emails Steven White, an assistant professor of political science in the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University.

Legal proceedings are another matter. However, Rudy Giuliani, former New York City mayor and current Trump lawyer, has said that he has been told Mueller will not indict Trump as a sitting president. That follows a current Department of Justice legal opinion holding that a chief executive can’t be indicted while in office.

Trump officials and family members aren’t protected by this opinion. Thus Trump conceivably could end up in Nixon’s position of being named an unindicted co-conspirator while others go on trial. (Nixon chief of staff H.R. Haldeman was convicted and sentenced to 18 months in jail for perjury, conspiracy, and obstruction of justice.)

But perhaps the biggest insulation Trump has that Nixon did not consists of words and pictures. The rise of the conservative media, from Fox News to Rush Limbaugh and other talk hosts plus Breitbart and conservative web sites, is a bulwark that could have whipped up resistance to the Watergate investigatory bodies and personalities of the times. Imagine what a Sean Hannity-style show host might have made of John Dean, the counsel to the president who turned and testified against him in the Senate. “Turncoat” would have only been the starting point.

The role of conservative media in defending Trump is “huge”, says Brian Rosenwald, a political and media historian at the University of Pennsylvania and expert on the political impact of talk radio.

The rise of right-leaning journalists and opinion hosts has enabled Americans to live in echo chambers of their choosing, says Mr. Rosenwald. Much of Trump’s rhetoric is pitched to Fox & Friends viewers and Mr. Hannity’s listeners, not the people who read The New York Times opinion page and listen to “Pod Save the People.”

That allows Trump to easily put his arguments before his most committed defenders.

“It is a huge factor in insulating him. You’ve got a complete alternative reality,” says Rosenwald.

What will happen if the echo chambers collide, so to speak? If Trump insists he can’t be forced to talk, but Mueller issues a subpoena? Or if Mueller issues a report that contains evidence Democrats think is damning, and Congress shrugs?

It’s a possibility. Voters would have to weigh the situation on what they believe to be the merits. We’d have to see what happens.

“I think many reasonable people are awaiting the Mueller report,” says Dr. Balogh of the University of Virginia and Backstory.

For Nigerians displaced by Boko Haram, lure of home comes with risk

How much would you risk to go home? That's the question tens of thousands of Nigerians displaced by Boko Haram are grappling with as officials push for their return to a region many deem unsafe.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Ismail Alfa Abdulrahim Contributor

In the past decade, nearly 3 million people in the Lake Chad region have fled their homes, most of them northern Nigerians escaping attacks by Boko Haram. Scattered across camps and communities, they have become among the most agonizing reminders of the human toll of that crisis. So officials’ promises to bring them home – a sign of success in the war against Boko Haram – might sound like welcome news. But in the eyes of some humanitarian groups, it’s too soon: Residents’ safety is being compromised by politics ahead of elections in 2019, they argue. And to many residents themselves, the situation appears far murkier. Sure, they say, it could be dangerous – as when two suicide attacks happened in the city of Bama, just days after relocations began. But in the tenth year of a war with no end in sight, it is also slowly breaking them to stay where they are.

For Nigerians displaced by Boko Haram, lure of home comes with risk

In the camps and settlements of displaced people that crowd this city, the stories often begin the same way.

The armed men arrived on motorcycles. Or they sprang from the flatbeds of dirt-streaked Toyota Hiluxes. Other times they were on foot, appearing as if from nowhere, machine guns slung over their shoulders with their barrels pointed skywards.

They came to the town mosque. To the school. To the market. They went door-to-door, looking for men. Looking for boys. Looking for young girls.

Everyone who could, ran. Those who couldn’t, walked. They tripped over bodies. They hid in pit latrines. They followed the road or they cut a path through the forest. But they didn’t stop moving. They couldn’t.

Over the past decade, nearly 3 million people in the Lake Chad region have fled their homes, most of them northern Nigerians escaping guerrilla attacks by the Islamist insurgent group Boko Haram. Scattered across camps and communities, they have become among the most agonizing reminders of the human toll of that crisis.

Now, the country’s displaced have also become the centerpiece of a rising political drama. With national elections approaching early next year, Nigeria’s government has promised – not for the first time – that it is on the verge of defeating Boko Haram. And to prove that, officials say, they are going to send their constituents home.

It’s too soon, some humanitarian groups have protested, arguing residents’ safety is being compromised by political goals. But to many of those residents themselves, the situation appears far murkier – home is a risky, but tempting, promise.

Sure, they say, it could be dangerous, but it is also slowly breaking them to stay where they are. In the tenth year of a war with no end in sight, the idea of staying forever in a tented camp or a foreign city is for many as oppressive as the possibility of violence outside.

“Of course we want to leave – on an average day here, I do nothing, I just wait,” says Usman Yakub, a resident of the Bakassi camp in Maiduguri. If he were home, he says, at least he might be able to farm. At least he could do something besides wait around for distributions of tarp and grains and old clothes. “Government tries to help us [here in the camps] but it’s impossible for another person to provide for all your needs.”

Pre-election push

After a decade of fighting, some 2.3 million Nigerians are still unable to return home, including more than 1.6 million inside Nigeria itself. Tens of thousands have become refugees in neighboring Cameroon.

“We want zero camps, we want everyone to be able to vote in their home locality next year,” says Ya Bawa Kolo, chairwoman of Nigeria’s State Emergency Management Agency (SEMA).

Such statements, however, have critics raising the alarm that politics are pressuring the government to bring people back to former rebel strongholds before it is truly safe.

“These relocations are entirely linked to the elections,” says Alexandra Lamarche, an advocate with Refugees International and author of a recent report on the returns. “The question is how far the government is willing to go with risking people’s lives to make its political point.”

Nigeria’s national elections are still nine months away, but already the smiling faces of political hopefuls smile down from billboards across Maiduguri. Bright yellow tuk-tuks twirl around roundabouts plastered with posters for would-be legislators and governors.

For President Muhammadu Buhari, who will run for a second term, defeating Boko Haram was one of his first campaign’s major promises. And although the Nigerian military has notched some major successes against the group since then, the insurgency continues to lash cities and towns across the region. Mr. Buhari, meanwhile, has been conspicuously absent here – most recently missing a forum of regional governors where he was the guest of honor.

“He certainly feels pressure to redouble his efforts now because he doesn’t want to be seen as not fulfilling his campaign promise,” says Ibrahim Umara, associate professor of international relations and strategic studies at the University of Maiduguri.

In March, Kashim Shettima, the governor of Borno State – where Boko Haram’s insurgency is concentrated – pledged that he would close all of the camps for displaced people in Maiduguri, the state capital, this year. By midway through next year, he promised, everyone who wanted to go home would be there. (Those statements are “conditional,” his spokesperson later stressed to the Monitor, and “the governor’s greatest wish is to close all camps and resettle all [displaced people] in safe and dignified ways.”)

In early April, a convoy of government-owned American school buses painted green and white rattled out of Maiduguri, bound for the city of Bama, 50 miles to the east.

The choice of Bama to begin the latest round of returns was deeply symbolic. The second-largest city in Borno, Bama has long been a weathervane for the government’s fight against Boko Haram. When it fell to the insurgents in 2014, it became proof-positive that Boko Haram could seize and hold a major city. When the Nigerian Army recaptured the city the following year, just two weeks before a national election, government officials pointed to the victory to show that the tide had turned.

Within two weeks of the first convoy, about 35,000 people returned to the city, according to figures provided by the United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR.

Going home – to what?

Babagana Kassim was among them. Three years ago, Mr. Kassim arrived in Maiduguri with nothing after fleeing an attack on a mosque where he was praying in Bama. He didn’t have his two wives or his nine children. Not his prized maroon Volkswagen nor the wad of naira notes he kept buried in the sandy dirt behind his house. Not even his shoes.

“I was broken then,” he says.

Slowly, he says, he built his life back. Three months later, his family followed him to Maiduguri, and a few months after that, Kassim, who had been a shopkeeper in Bama, opened a small store selling snacks and household goods.

But the thought of going home was never far from his mind, and when he heard on the radio that the government was beginning relocations back to Bama, he decided immediately to go.

As soon as he arrived, however, he says something seemed off.

“They were telling us the whole city was rebuilt but when we arrived, but it was maybe one in three buildings,” he says. And the sudden influx of people had strained humanitarian resources. Food distributions kept running out before he got to the front of the queue.

Then, five days after he arrived, he was at the mosque for morning prayer when he heard an explosion. A suicide bomber had blown themselves up nearby. The next morning, it happened again.

“The day after that, I came back to Maiduguri,” he says. “I realize now, taking people home is a ploy for the election period. Wait till the election finishes – they’ll stop all this talk. It’s just to deceive people into voting.”

After the two attacks, the local government halted the returns, saying they would only continue when the security situation was better. Still, most of those who returned to Bama have stayed, according to UNHCR.

But in the camps in Maiduguri, many of the displaced still think returning home before the elections is a far-fetched idea. For Talatu Akawu, who lives in Bakassi and comes from the nearby town of Gwoza, it’s no longer her top priority.

“Our house was destroyed, so as of now, we don’t have anything to go home to,” she says. But Maiduguri sometimes seems little better, she says. On a recent afternoon, she was hanging her laundry outside the tarp tent she shares with her family when she heard the familiar pop-pop-pop of gunshots in the distance. It was Boko Haram, attacking a neighborhood nearby.

“It’s a fiction to say that Boko Haram is defeated,” she says. “Look what happens – we are not even safe here.”

Why the world comes together over an improbable Colombian reef

Beneath the murky waters of one of South America’s busiest ports, the Varadero coral reef has become an unlikely symbol of survival and beauty.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Svoboda Contributor

Locals call Varadero “the improbable reef” for good reason. Here in one of Latin America’s busiest harbors, the first few feet of water are what you’d expect, nothing but a yellow-tinted haze. But about 10 feet down is a massive vista that, by all scientific logic, shouldn’t be here: a kaleidoscopic reef garden, in made-for-IMAX colors. It has persevered in the midst of intensive coastal development, streams of toxic runoff, and waters so warm they’d turn many reefs into lifeless skeletons. Scientists are working to uncover the secrets of its striking resilience, secrets they can use to help other threatened reefs around the world. The so-called rainforests of the oceans are in danger of virtually ceasing to exist by 2100. But scientists and reef advocates also have to save Varadero itself. There are plans to dredge a channel so the harbor can accommodate more container ships – a move that could boost Colombia’s economy.

Why the world comes together over an improbable Colombian reef

Luis David Lizcano-Sandoval is looking for just the right spot to descend. With his hand-held GPS unit at the ready, the marine biologist from the University of Valle in Cali, Colombia, issues instructions to our boat’s driver, Pablo: a la izquierda, to the left, or a la derecha, to the right. Just a few hundred yards from us, loaded container ships pass to and from Cartagena, Colombia’s main port city. Each time one chugs by, our tiny boat rocks energetically in its wake.

Mr. Lizcano-Sandoval signals to Pablo to cut the motor, then jumps into the water and disappears. A few moments later, his head pops back up. “This is it,” he says. Together, we don our masks, let the air out of our scuba vests, and start sinking beneath the waves.

The first few feet of water are what you’d expect in one of Latin America’s busiest harbors – nothing but a yellow-tinted haze, a layer of polluted sediment that rises to the surface like oil. But about 10 feet down, the pea soup abruptly turns clear and turquoise.

As a cool ocean current drifts through, a massive vista opens up to reveal something that, by all scientific logic, shouldn’t be here – a kaleidoscopic reef garden, rising out of the depths like some fanciful rampart. Over on one edge, there’s a purple coral behemoth with convex shelves jutting out. Darting surgeonfish flank orange coral domes, each one as wide as an outstretched arm. Bright sea fans dot the landscape, waiting to extend their tendrils for the floating plankton that sustain them.

“It’s like a city,” Lizcano-Sandoval says as we surface, spitting salt water. This arresting time-capsule world, he thinks, may look much the same now as it did centuries ago, when Spanish conquerors built fortress walls around Cartagena to keep marauding pirates out.

For the coastal communities that have harvested its bounty for centuries, and for the scientists who officially discovered it five years ago, there is no reef like Varadero. Locals call it “the improbable reef,” and for good reason: It has persevered in the midst of intensive coastal development, streams of toxic runoff from the nearby Canal del Dique (Dike Canal), and waters so warm they’d turn many reefs into lifeless skeletons. Scientists like Lizcano-Sandoval and Pennsylvania State University’s Mónica Medina are working to uncover the secrets of Varadero’s striking resilience – secrets they can use to help other threatened reefs around the world.

But just as Varadero begins to yield its tantalizing scientific bounty, it’s looking as if the reef may be damaged or even destroyed. A group of government officials, port authorities, and businesspeople is planning to dredge a channel so Cartagena’s harbor can accommodate more container ships – a move they say will boost the nation’s economy. However, the researchers who study Varadero, along with local environmental activists, are hoping to stall the dredging project so the reef’s storied legacy can continue – and perhaps contribute to the rescue of other endangered underwater Edens.

***

Coral reefs like Varadero are the rainforests of the oceans: diverse ecosystems that contain more species per square mile than almost anywhere else on Earth. Even though reefs cover only about 1 percent of the world’s seabeds, they contain at least one-quarter of all sea life. Smithsonian Institution researchers now think the biodiversity of reefs might be even higher than previously thought: When they surveyed a variety of coral reefs, 38 percent of species they came across were rare ones (found only once), and 81 percent of species were found only in a confined local area.

Millions of people around the world, especially in coastal zones, depend on coral reefs for their bounty of fish. Reefs also protect vulnerable coastlines from storm surges and attract tourists interested in snorkeling and diving.

But a variety of human-caused phenomena, including gradual sea warming, pollution, and ocean acidification from dissolved carbon dioxide, are pushing many coral reefs to the edge of extinction. When ocean temperatures rise too high, the tiny coral animals that make up reefs expel their zooxanthellae, “helper algae” that use photosynthesis to make food for the corals. As a result, the corals turn white or “bleached,” and having lost their main food source often die soon thereafter. And when too much carbon dioxide from tailpipe emissions saturates ocean waters, the higher acid content that results can damage reef structures, causing them to crumble. Not only does that threaten corals, it endangers the marine species that depend on reef formations for shelter.

As factors like these have converged in recent years, the pace of reef destruction has picked up. A 2017 study by UNESCO found that 25 of the world’s most important reefs, which make up about three-quarters of the world’s reef systems, had undergone significant bleaching in the past three years. One, the Great Barrier Reef, lost about 30 percent of its coral cover in 2016 alone. Other mass die-offs have decimated systems from the Caribbean to the Indian Ocean.

The need for solutions has never been more urgent, and marine scientists are scrambling to come up with ways to save the world’s underwater rainforests. The Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium in Sarasota, Fla., for instance, is growing corals in controlled conditions that researchers will later transplant onto faltering reefs. Mote aims to plant more than a million corals to replace dead or dying ones.

Another promising avenue involves creating “coral probiotics”: supplying threatened corals with a mixture of bacteria from healthier corals, which may make their systems more resilient to stresses such as warming waters and disease.

These strategies have yet to be tested on a global scale. But in the absence of such drastic measures, coral reefs as we know them could virtually cease to exist by 2100, which is one reason activists are focusing so urgently on what lies at the bottom of the bay here.

***

The project Valeria Pizarro took on in January 2013 seemed like an innocuous one. A Colombian marine biologist and an experienced diver, Dr. Pizarro carried out underwater environmental surveys for a variety of clients. This time, a consulting agency representing Cartagena’s port developers had hired her to check out a location near the mouth of Cartagena Bay.

Cartagena was growing and flourishing as never before, and developers wanted to dredge the location to create a new shipping lane for large boats. A previous survey had reported that the bottom of the bay was largely devoid of life. A “degraded reef,” the survey called it. Pizarro’s job would be to find whatever small clusters of coral still remained. She would then transplant these stragglers elsewhere to clear the way for the new shipping lane.

Pizarro’s goal for her first dive was simply to survey the area before going back for more detailed analyses. As she descended through the murky water, she braced herself for the degraded reef she’d been told to expect. Maybe I’ll find some small corals, she thought. Maybe some medium ones.

Then, in less time than it took to exhale a lungful of bubbles, the vista changed. An entire unspoiled coral reef, in made-for-IMAX colors, unfurled like something Gabriel García Márquez had dreamed up. Pizarro paused, trying to take in the magnitude of it all. One question lodged in her mind: How come? This reef, she knew, should not exist. Its presence was a feat of magical realism.

One of the men who’d hired Pizarro was on the boat with her when she discovered the reef. “We have a problem,” she said to him after she surfaced.

“What is it?”

“We don’t have a few colonies here. We have a coral reef.”

The consultant balked, telling Pizarro they probably weren’t in the right spot. But she stuck to the evidence she had seen through her mask.

Over the following weeks, Pizarro methodically surveyed the entire area. There were thriving reef formations everywhere, fortresses of coral extending all across the bay’s mouth. “We dove the whole [thing], trying to find the best place for the shipping channel,” Pizarro says. “We never found that place.”

It wasn’t long before she decided she had to get out of the project entirely. She knew it might mean taking a financial hit, but she couldn’t stand the thought of helping to destroy the undersea world she had just uncovered.

***

It took some time for Pizarro, now executive director of Colombia’s ECOMARES foundation, to process the discovery she’d made. But the response from her fellow scientists was a good gauge of its magnitude. Researchers started calling Varadero “the heroic reef” – a nod to Cartagena itself, dubbed “the heroic city” after surviving centuries of sieges and attacks.

The year after Pizarro found the reef, Mateo López-Victoria, a biologist at Pontifical Xavierian University in Cali, Colombia, rushed a short journal article into print to tell the world of the reef’s existence. The dispatch sketched out Varadero’s unique qualities in broad strokes.

“The largest colonies found must have survived repeated human disturbances,” Dr. López-Victoria and his colleagues wrote. “This coral formation is a unique resource that should be conserved and further studied considering its high species diversity, the large size of some of its coral colonies, and the atypical conditions under which it developed.”

Thanks to the initial surveys they’ve done, researchers have gleaned some insights into what makes Varadero unique. “Corals in Varadero have a very distinct growth pattern,” says biologist Roberto Iglesias-Prieto, Dr. Medina’s colleague at Pennsylvania State University. Specifically, the corals grow about twice as fast as similar corals elsewhere, but their skeletons are less dense; it’s possible that these traits give them an advantage over their slower-

growing coral counterparts.

Medina thinks certain elements in runoff from the Canal del Dique may be benefiting the corals in surprising ways. “Part of the day, [the corals] get these nutrient-rich waters where they’re eating and photosynthesizing,” Medina says. She notes that fairly recent changes in coral growth coincide with a period when more sediment was being dumped into the bay.

It’s likely, then, that certain reefs actually thrive on some nutrients found in canal runoff. Varadero’s corals might also benefit from their location right at the mouth of Cartagena Bay. “They have constant communication with the sea,” Pizarro says. The fresh inflow of ocean water might lessen the impact of toxic mercury, cadmium, and copper that runs off into the bay from nearby industrial facilities.

Medina and her colleagues are trying to figure out if other aspects of the reef’s biology contribute to its success – aspects that could ultimately be replicated in reefs elsewhere. “There is something about the location,” Medina says. “Everybody does better in Varadero.” Samples of microbes from Varadero’s corals – the onboard collection of bacteria, viruses, and algae that perform critical metabolic tasks – have revealed that they are totally distinct from those found on other reefs, Medina says. Her lab is conducting a detailed analysis to find out whether the microbes might be performing important functions, such as fighting disease, that help the corals to survive even in less-than-ideal conditions.

In the future, if conservationists can transport Varadero’s hardy corals to other endangered reefs around the world, or even seed threatened reefs with whatever microbial cocktail helps Varadero’s corals thrive, those reefs might have a better chance of surviving despite ocean warming and pollution. Many of the world’s reefs now hang in a liminal zone between death and survival. By putting Varadero corals’ survival tactics to work on other threatened reefs, scientists like Medina, Lizcano-Sandoval, and Pizarro hope to tilt those reefs a little bit closer to the side of life.

***

The big question hanging over these investigations is whether the scientists will be able to finish them at all. Developers’ dredging plans stopped after Pizarro first discovered the reef, but Colombia’s Ministry of Transport, Cartagena port authorities, and developers have since come up with a revised dredging proposal. While the new plan is designed to be less damaging to Varadero than the initial one, it would still involve slicing a shipping channel across the heart of the reef.

Officials at National Development Finance (FDN), which funds national development ventures, are backing the dredging plan because of the economic opportunity they say it offers the region. As one of the 10 largest ports in Latin America, Cartagena handles more than 2 million containers per year, and dozens of ships enter the bay each week. FDN says the channel project would boost Colombia’s competitiveness by reducing boat traffic delays and allowing ships to reach Cartagena more easily.

“Currently, Cartagena’s port has a unique navigation channel way, which increases the ships’ waiting time for entry and exit from the harbor,” says FDN spokeswoman Juliana Maria Restrepo Marin. If plans for the new channel go forward, she adds, more ships will be able to reach the port, which would create more jobs and reduce the cost of some consumer goods. “This new project will have economic benefits, not only for Cartagena, but for the whole country.”

Pizarro estimates, however, that the latest planned dredging operation would ruin at least a quarter of the reef, a blow that would threaten much of the remainder. That’s why a group of Colombian activists, including psychologist and teacher Bladimir Basabe, is working to make sure dredging plans never come to fruition. At a conservation conference Mr. Basabe attended a couple of years ago, one presenter talked about Varadero, and Basabe – who had never heard of the reef at the time – was entranced. For many years, the consensus had been that “the bay does not harbor any coral, that everything is dead,” he says. “The corals of Varadero have shown the opposite, to society and to world science.”

When Basabe found out the reef might not survive the decade, he resolved to act, forming a nonprofit called Salvemos Varadero (Save Varadero). Other local activists, including environmental lawyer Rafael Vergara – a former Colombian M-19 revolutionary – soon joined the cause. Ideally, Basabe says, “what will happen is that the channel project will be totally suspended, and the project area will be forced to change.”

After Salvemos Varadero was created, its leaders swung into action in a 21st-century way: They posted a petition on change.org, describing the reef and urging people to resist the planned dredging operation. More than 25,000 people have signed the petition so far. “The defense of the reef is a victory,” Mr. Vergara says over coffee and Oreos at his seaside Cartagena apartment. He scoffs at developers’ projections of economic growth, saying the city wouldn’t necessarily see increased shipping traffic after dredging operations – and that even if it did, the project would still be a mistake. “The corals,” he says, “are more important than the gains of private companies.”

***

The dredging project is currently under environmental review, and the developers have pledged to abide by the results of the review, whatever they might be. “We want to be clear that the project will only take place if it’s environmentally viable, and if it has all the legal and environmental authorizations,” Ms. Restrepo Marin says.

To get approval to proceed, the developers will have to update their environmental license from Colombia’s National Authority of Environmental Licenses. In order to secure license renewal, project partners will consult with communities from the area surrounding Varadero, communities that benefit directly from the reef’s bounty of fish. “The communities are becoming more informed. They have united with activists,” Medina says.

Many locals have a detailed understanding of what they stand to lose if the reef disappears, which may make it harder for developers to make the case for dredging. Colombia’s National Natural Parks authority and activists from Salvemos Varadero are also involved in the discussions about the reef.

At the very least, Pizarro says, the meetings between different parties will take several months, which should stall dredging approval long enough for Colombian citizens and others around the world to learn more about the reef. The ideal outcome of the discussions, in Pizarro’s view, would be for the country’s Ministry of Environment to add Varadero to an existing marine protected area that surrounds the Rosario and San Bernardo archipelagos. “That will be just what we need,” she says. “It would be the ultimate goal.”

In principle, Colombia’s National Natural Parks authority favors this goal. “We are ready to support the creation of permanent spaces that guarantee the protection of these corals,” says Luz Elvira Angarita, Colombia’s National Natural Parks director of the Caribbean territory. Right now, she says, the main obstacle is that Colombia’s current environmental budget does not cover the extra cost of adding Varadero to the protected area. But since national legislators reevaluate this budget from year to year, activists could potentially persuade them to allot more money to keep Varadero intact.

Basabe is also pushing to get the reef added to Colombia’s official coral reef atlas, which is maintained by INVEMAR, the country’s institute for marine and coastal research. The atlas hasn’t been updated for years, and since Varadero does not appear in its pages it is not entitled to the same environmental protections as reefs that do.

From her light-filled upper-floor apartment facing Colombia’s Santa Marta mountains, Pizarro ponders the reef’s future. As the scientist who discovered Varadero, she feels as bonded to the reef’s inhabitants as she does to blood relatives. “I have lots of pictures of coral,” she says, laughing, as she scrolls through her laptop’s photo gallery. “Corals are part of my family.”

While she’s optimistic about Varadero’s prospects, she knows the economic pull to expand Cartagena harbor is strong. “For me it’s, ‘This reef is unique.’ For them it’s, ‘We need it for development,’ ” she says. “Yes, you’re going to get a few million dollars. But in the long term, this reef is going to give us lots more.”

This spring, oceanographer Sylvia Earle’s international Mission Blue alliance named Varadero Reef an official Hope Spot, a distinction that activists say strengthens their case. Vergara, for one, is confident, refusing to even consider the prospect of losing the reef. “We have to win,” he says, with echoes of his old revolutionary fervor.

If officials and citizens agree, the “heroic reef” can continue to teem with life – and scientists like Medina can go on cracking the code of its resilience. “All we want,” Vergara says, “is permanence.”

Saving the Varadero coral reef

Mall? Utility? Internet metaphors matter in net neutrality debate.

Like other countries, the United States is trying to figure out how best to regulate the internet. The debate is showing how deeply language affects the way we see complex things.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Absent intervention by Congress or the courts, the Federal Communication Commission’s net neutrality regulations, which prevent internet service providers like Verizon and Comcast from establishing tiered pricing and levels of access to the internet, will expire on June 11. But the rules, which are supported by big majorities of Americans in both parties, aren’t going down without a fight. Framing arguments on both sides of the debate are different metaphors about what the internet really is. Is the internet a grocery store, for instance, or more like a utility? “Metaphors play a fundamental role in our basic understanding and in the way we reason about various important topics in our lives,” says University of Oregon philosopher Mark Johnson. And “the metaphors that operate most powerfully,” says Annette Markham, a professor of information studies at Aarhus University, “are those that operate without our awareness.”

Mall? Utility? Internet metaphors matter in net neutrality debate.

Accompanying nearly every debate over internet policy is a host of conflicting metaphors over what the internet actually is.

“It’s not a big truck,” Sen. Ted Stevens (R) of Alaska famously remarked during a 2006 Senate debate over net neutrality; rather, he explained, not entirely implausibly, “it’s a series of tubes.”

More than 11 years later, during a November 2017 House antitrust hearing on the same topic, Rep. Darrell Issa (R) of California compared the internet to a Safeway supermarket that leases its end-cap displays to soda companies, and to a magazine that charges advertisers more money for the back cover. Meanwhile, proponents of net neutrality warn of “throttling,” “fast lanes,” and a literal threat to freedom of expression.

As the debate intensifies over whether the companies that built and own the tubes should be required to treat everything that flows through them equally, so too will the figures of speech, tropes, analogies, and framing devices used to describe what American internet pioneer Bruce Schneier calls, “the most complex machine man has ever built.”

“There’s no way to reduce any important concept like the internet to one single metaphor,” says Mark Johnson, a philosopher at the University of Oregon in Eugene, Ore. “And they don’t always fit nicely together, which just mirrors the complexity of the human conceptual system.”

Beginning in 1979, Professor Johnson, working with University of California, Berkeley, linguist George Lakoff, helped transform how cognitive science, linguistics, and many other disciplines think about metaphors. Drawing primarily on linguistic evidence, in their influential 1980 work, “Metaphors We Live By,” Lakoff and Johnson argued that, far from being merely figures of speech, metaphors are fundamental modes of thought that structure how we experience the world, think about it, and act within it.

“Thirty-some years ago, people didn’t take metaphors seriously. It was kind of a marginal notion,” says Johnson. “And what’s happened is a radical shift in which we’ve come to see that metaphor is a fundamental process of human cognition, and it isn’t really optional when it comes to our abstract concepts.”

Annette Markham, a professor of information studies at Aarhus University in Denmark, says she has relied on Professor Lakoff’s and Johnson’s theories to analyze how people talk about the internet. In the debate over net neutrality leading up to the Federal Communication Commission’s 2015 decision to require it, she observed a distinction in how those on each side of the debate frame their arguments.

Those who opposed net neutrality rules – a group that includes Verizon, Comcast, AT&T, Time Warner, and other companies that bring the internet to people’s homes, offices, and mobile devices – “focused almost solely, especially in 2015, on the physical infrastructures that powered the internet,” she says. In this framework, says Professor Markham, “the internet isn’t the place where society exists. It’s a set of pipes that have to be maintained and owned and controlled by someone.”

By contrast, for net neutrality’s proponents – this includes Silicon Valley giants Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Netflix, as well as big majorities of Democratic and Republican voters – “the internet is a ubiquitous part of society that we’ve come to depend on in the same way that we depend on streets and sidewalks and water running from the tap,” says Markham. “The broad capacities of the internet remain a very central focus of this group.”

'Sharing' vs. 'the information superhighway'

One of the earliest metaphors used to describe the internet, long before it had actually been invented, was the library. Writing in the July 1945 issue of The Atlantic, the American engineer Vannevar Bush asked readers to consider a desk-sized device, which he named the “memex,” that could store, retrieve, and display microfilms of millions of books and other records. Each page would have codes linking it with related pages, creating a “mesh of associative trails.” Engineers inspired by Bush went on to create hypertext, one of the basic features of the World Wide Web.

But, as the internet evolved, viewing it as simply a collection of linked texts proved too limiting. “I’d say that we view the internet more as a utility, that it’s a resource that nowadays really everyone needs to do basic things,” says Alan Inouye, the director of public policy for the American Library Association, which has been a major supporter of net neutrality.

Beginning in the 1990s, as the internet began to make its way into the households of wealthy and middle-class families, the reigning metaphor shifted from that of an information resource to a kind of space. Users would “surf” through “cyberspace” from one “site” to another along an “information superhighway.”

“These very spatial metaphors encouraged us to think about the internet as a physical place that we go to,” says Jessa Lingel, a professor at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. “We sort of leave our bodies behind, and then you can become something much more abstract and less embodied online.”

That framework began to shift again, says Professor Lingel, in part because of a deliberate rebranding of the internet after the dot-com crash of 2001. “Then you get Web 2.0, and that is when you start to start to see this participatory culture, remix culture, mashups, and the idea that everyone is going to be putting content together themselves.”

The metaphors kept shifting with the rise of social media platforms like MySpace, Facebook, and Twitter. Now, instead of posting new renderings of creative content, people began “sharing” information about themselves, such as their demographic data, their consumption habits, and their likes and dislikes of nearly everything.

“ ‘Sharing’ has become the norm of the internet, because that is how companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Google monetize their activity and make profit,” says Lingel.

“An ‘information superhighway’ is a regulated system,” says Markham. ”With ‘sharing,’ there’s no regulatory presence. It’s just a choice, very individually oriented. And there’s a free will built into that kind of metaphor.”

Today, attitudes are shifting again. Many Americans are now rattled by the full implications of a system that collects and monetizes information taken from its users, and the European Union has announced its intentions to come down hard on companies that fail to protect the personal data of people within its borders.

But even as people continue to express anxiety about the internet, society still allows it to suffuse more and more aspects of daily life, even going as far as to carry it around with us in our pockets.

“Over the last 20 years,” says Markham, “we have completely stepped into the frame.”

“Because of mobility,” says Dr. Inouye, “the internet is really more like air.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Mexico’s big moment – and one for the US, too

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

On July 1, Mexico will choose a new president in an election that will not only determine Mexico’s direction but will also affect the United States. For a host of reasons, what happens in and with Mexico touches more US lives daily than events in any other country. The front-runner in the presidential campaign is Andrés Manuel Lopéz Obrador, a former mayor of Mexico City who is known as AMLO. AMLO proposes to replace the “mafia of power” with a government working for the “good people.” Polls show AMLO’s lead holds across all demographics. But compared with his closest rival, AMLO has much less experience in dealing with the US. This leaves his potential management of US-Mexican relations unclear. That relationship has been tested by tariffs and tweets, and by perceptions of US unfairness in NAFTA negotiations. No matter who wins the presidential election, it is not in the interest of the US to jeopardize an important relationship. For decades, the economic well-being and security of both countries have improved when they seek “win-win” solutions. During these critical next few weeks in Mexico, the US must find ways to mend its ties with a close neighbor.

Mexico’s big moment – and one for the US, too

Mexicans are preparing to vote in elections that carry big implications for both their country and the United States. They will choose a new president and thousands of other officials on July 1.

With the two countries entwined as never before, the vote – as well as recent decisions by President Trump – calls for special care of a special relationship.

The front-runner in the presidential campaign is Andrés Manuel Lopéz Obrador, commonly known as AMLO, a former mayor of Mexico City. He is a well-known leftist who ran unsuccessfully for president twice before. He has so far focused his campaign on rooting out corruption and standing up for the less well-off.

Much of his popularity is also based on a widespread perception that the past two presidents and their political parties – the right of center National Action Party (PAN) and the long-dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) – were not able to control unprecedented levels of criminal violence or generate sufficient economic growth to benefit most Mexicans.

AMLO proposes to replace the “mafia of power” with a government working for the “good people.” The 25,000 violent homicides in 2017, the highest number recorded in the past 20 years, have convinced many of the need for change. Polls show AMLO’s lead holds across all demographics, including the well educated.

Compared with his closest rival, AMLO has much less experience in dealing with the US. This leaves his potential management of US-Mexican relations unclear. He and aides have rebutted criticisms that he might follow the path of Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez. He has dispatched aides to Washington and New York in an effort to reassure influential Americans about his intentions.

This shows that the election will not only determine Mexico’s direction but will affect the US. What happens in and with Mexico touches more US lives daily than events in any other country because of a combination of trade, family ties, and other connections. An estimated 35 million US citizens are of Mexican heritage. More than a million legal crossings take place each day along the 1,990-mile border. Mexico is America’s second largest export market, and the US is by far Mexico’s largest trading partner.

At the same time, studies estimate that some 5.5 million Mexicans are in the US illegally, though the number may have dropped over the past 10 years. Illegal drugs and unauthorized immigrants (now mostly from Central America) still head north across the border, while arms and billions of dollars from drug sales head south to criminal groups.

Since 2007, US-Mexican security cooperation has deepened on fighting drug trafficking, illegal immigration, and terrorism, becoming critical to US security. In 2017, Mexican and US cabinet members agreed on a strategic plan for going after transnational organized crime involved in drug trafficking. In recent testimony to Congress, US officials described bilateral security cooperation as unprecedented.

The massive improvement in the relationship stems from the growing commercial ties built since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was negotiated 25 years ago. Since then, US-Mexican trade has multiplied by six, with substantial investments flowing from both sides. Some 5 million US jobs depend on business with Mexico, compared with an estimated 700,000 in 1993.

Today, the two countries build things together. Mexico’s finished manufactured exports to the US, for example, contain the highest levels of US parts and supplies by far compared with those of any other trading partner. Many economists argue that the relationship has made both economies stronger and helped many US companies fend off competition from low-wage countries in Asia while keeping prices lower for US consumers.

On May 31, Mr. Trump applied tariffs to steel and aluminum from Mexico (as well as from Canada and the European Union), which many interpreted as a step to increase pressure on those countries to reach new trade agreements on US terms. Mexico announced a list of US products to which it will apply reciprocal retaliatory tariffs. These moves threaten not only the ongoing renegotiation of NAFTA but also the $600 billion in yearly trade and Mexico’s cooperation on security.

So far, the Mexican presidential campaign has largely focused on domestic issues rather than the country’s ties to the US. Nevertheless, the tariffs and frequent anti-Mexico tweets by Trump are perceived as unfair. Many Mexicans also view US demands in the NAFTA negotiations as unreasonable and threatening. Not surprisingly, critical opinions of the US among Mexicans are well over 50 percent compared with 29 percent three years ago. Mexico’s government will not want to be perceived as yielding to US pressure tactics.

No matter who wins the presidential election, it is not in the interest of the US to jeopardize an important relationship. For decades, the economic well-being and security of both countries have improved when they seek “win-win” solutions. During these critical next few weeks in Mexico, the US must find ways to mend its ties with a close neighbor.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Can God still love me if … ?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Today’s author shares how no circumstance can separate us from the love of God.

Can God still love me if … ?

When I was in grade school, my parents were unable to care for me, so I found myself living with other families in our city. That’s a hard thing for any child to face.

But one day, at the Christian Science Sunday School I’d been attending, I was introduced to one of the most profound points in the Bible: “God is love” (I John 4:8). My teacher explained that God’s love, like sunlight, shines on everyone, no matter what. And from Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy’s book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” I learned that “Father-Mother is the name for Deity, which indicates His tender relationship to His spiritual creation” (p. 332).

I came to feel so tangibly that divine Love was my constant companion that I was able to go through those years without my parents and yet not feel alone. And ever since, I have valued every opportunity to help others feel that same impartial love of God for them.

Some years ago I was asked to give a talk in a detention facility for teenagers who had committed crimes that, if they were adults, would have put them in prison for many years. The talk was about the nature of God as Love itself, and a girl in the back raised her hand and asked whether God could truly love everyone, no matter what they had done – then her face turned red, she looked down in her lap, and she started to cry.

What happened next was powerful. We explored that idea of God’s love, which I had been so helped by as a child and ever since. I was able to say, “Yes, God certainly loves us all, without any lapse and without any exception.”

I wanted them to know that we each have a deeper identity than it may seem on the surface, and that’s how God is always seeing us. I considered with them what it means to be the purely spiritual offspring of a divine Father-Mother who, as Love itself, is always present and supremely powerful. This truly endless love of God purifies us, teaches us, corrects us, and guides us.

By then, a number of these teenage inmates were in tears, but they were strong, good, hopeful tears. As I was leaving, I thought, “In just a few minutes, I will be gone from this facility, but I know that God – our Father-Mother, Love – will always be with each of these individuals, and no one can be separated from our divine Parent’s caring, redeeming presence.”

I love what the Bible says of God’s love in this passage: “As one whom his mother comforteth, so will I comfort you” (Isaiah 66:13). Divine Love’s pure goodness tenderly nurtures us, as a caring mother nurtures her child. Opening our heart to the reassurance and love of our true Parent, God, brings strength and redemption. This leads us to think and act more consistently with our loved and loving spiritual nature as the children of God. We can glow in our divine Father-Mother’s love. And we can grow in it, too.

As those teens in the detention center seemed to glimpse, it’s a powerful thing to simply pause and feel God loving us; and the reason we can feel His love when we do so is because it is always there for each of us.

A message of love

Remembering the resisters

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when correspondent Taylor Luck looks at protests in Jordan that have brought down the prime minister. Young Jordanians are finding their voice for the very first time – without the divisive political language that doomed the Arab Spring.