- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Independence Day revives question with new edge: What is patriotism?

- Four months from midterms, real questions about security from hacks

- Hope for Helsinki: Russia foresees steps on Syria, arms control, Ukraine

- Back to Tulsa: An experiment offers three families hope for American dream

- How a surge in political humor drove young Colombians to the polls

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for July 3, 2018

Forget the World Cup. The most compelling “soccer story” of the week is one of hope and perseverance and global cooperation.

A Thai boys soccer team, lost in a labyrinth of caves in northern Thailand, was found Monday. For 10 days, rescuers hunted for the 12 boys and their coach, fighting rising fear and rising waters.

On June 23, the boys, ages 11 to 16, rode their bicycles to a popular hiking spot: the Tham Luang Nang Non caves. But heavy rains flooded the caves, driving the boys deeper. Efforts were made to pump water out. Monks offered prayers. More than 1,000 people, including teams from Thailand, Britain, the United States, Australia, and China, searched for alternate entrances and plumbed flooded caverns. Nothing. But as rains eased this past weekend, hopes rose. British divers found all huddled on a small ledge.

Outside, tears of joy flowed among families and rescuers. On Tuesday, Thai Navy medics brought in food, but extracting the boys won’t be easy. Twisted, narrow passages filled with muddy waters – hard for experienced divers to navigate – lie between the team and their exit. “We worked so hard to find them and we will not lose them," the provincial governor declared. Families are eager to be reunited. One mother, proclaiming her love in a universal way, affirmed she would soon make her 11-year-old lost boy his favorite meal: a Thai fried omelet.

Now to our five selected stories, including the quest for integrity in American democracy, new paths out of poverty in Oklahoma, and the power of humor in Colombian politics.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Independence Day revives question with new edge: What is patriotism?

As much as “patriotism” shapes the US national debate, there is little agreement on what it is. The freedom to define patriotism may invite social division, but that freedom can also unify.

-

By Doug Struck

Views of American patriotism generally fall into two camps, says Peter Dreier, a professor of politics at Occidental College in Los Angeles. “The first is ‘my country, right or wrong.’ The other is ‘my country, love it and fix it.’ ” Groups and individuals embrace their own versions. Military families bravely report for duty to their country, generation after generation. Professional athletes find their expression in kneeling in protest of social conditions during the national anthem. Clearly, such competing visions are helping to wedge America apart. Measured by polls, hate crimes, and inflammatory rhetoric, the country is becoming more polarized than it has been in at least 50 years. Still, patriotism can also be the necessary glue keeping a country together. What binds many: agreement on the fundamental quality of the American ideal, however well it’s seen as being lived up to at any given time. Robert Noble, a nonagenarian vet who served on D-Day, mused on public patriotism after a Memorial Day parade in Quincy, Mass. “A lot of it depends on what is happening in the country,” he says. “I just feel very fortunate to be here.”

Independence Day revives question with new edge: What is patriotism?

Tom Nelson has a cross tattooed on one arm, a deer on the other, a .38 special pistol tucked under his seat, and a commemorative license plate on his pickup truck that reads “Maine Patriot.”

He mulls over how to explain the slogan.

“Well, I pay my taxes. I vote. I follow the law,” he begins. “I support the Constitution. I support the Second Amendment. I’m all for religion, freedom. I support the military, raise my kids right, and take care of my mother.”

For many, that might be a pretty good definition. Others might pick at it. For as much as “patriotism” blooms in the national debate, there is little agreement on what it is. Or who owns it. Or who is a patriot.

As an increasingly riven country chooses up tribal sides, patriotism is being used as a litmus test, but Americans can’t agree on what color passes. National Football League (NFL) players who knelt during the national anthem were accused of not being patriots. They insist their protest was exactly what patriotism requires.

Politicians, especially on the national level, find they cannot run for office without wearing a lapel pin of the flag boasting of their patriotism – Barack Obama had to defend his occasional choice to go pinless during his first presidential campaign. Park statues are torn down – or defended – and streets and buildings renamed in disputes over which patriotic symbols should represent the United States.

Some Americans remain firm in their certainty of what – or who – is patriotic. But in a smattering of conversations around the country, others admit they struggle with the issue.

In Clifton, Ariz., a small copper mining town carved into rock mountains, Steve Guzzo and Bob Jackson say patriotism was woven into expectations of their town, and that sent them both to Vietnam.

“We all come from military families. Most people were World War I, World War II ...,” Mr. Guzzo says. “You were an American, so you paid your dues just like everybody else. You went into the service.”

“I don’t know what [patriotism] means anymore,” Mr. Jackson says. “There’s people that wave the flag and all that. I don’t agree with them at all, you know. But they still have their right to do it.”

The uproar over the decision by San Francisco quarterback Colin Kaepernick to kneel in protest over police brutality and injustice during the national anthem brought a collision of racial grievances and passions about patriotism. Black Americans found themselves, as they have often in history, at a crossroads.

“This current debate really does leave out the experiences and the complex meanings of patriotism for African-Americans,” says Chad Williams, chair of the department of African and Afro-American studies at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and author of “Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era.”

“I think African-Americans have historically embraced a type of patriotism, one that is not blatantly white supremacist, one that is encompassing of all that America should stand for: freedom, democracy, equality,” he says.

But the US has long been fractured over who “Americans” should be, from the stirring “all men are created equal” vow of the Declaration of Independence, made hollow by slavery, to the “Give me your tired, your poor” invitation of Lady Liberty now mocked by mass roundups of immigrants.

An American flag stands in the corner of James Bonds’s office in Worcester, Mass., a city 40 miles west of Boston. Mr. Bonds and two colleagues are there. They all served during or just before the Vietnam War. They say they are patriotic, all proud to be Americans. But not proud of all Americans.

“I love this country,” says Nick Schuyler. “You have opportunities here. But the color barriers ...” His voice trails off.

In 2000, there were three Veterans of Foreign Wars posts in Worcester. The men say they inquired about joining, but “the quartermaster never seemed to be there with the right membership form for us to fill out,” says Bonds. He and his comrades are black. The VFWs were all white, he says, and mostly vets from World War II. So the three men started their own VFW post. The other posts eventually closed.

“I definitely support the flag,” says Bonds. “But also realize the flag was used in the South Boston bus riots. Remember the picture of the guy that got beat with an American flag? That’s patriotism? It depends on who is defending it, who is naming it.”

“Protesting is as American as breathing,” says Melvin Collins. “That’s what this country was founded on, Boston Tea Party and all. And keep in mind, if you stifle protests, you are going to end up with something much worse.”

***

All manner of groups have embraced patriotism, for diverse reasons. NFL team owners were paid by the military for years to stage patriotic halftime ceremonies and thunderous jet flyovers, and the owners cultivated the fans who applauded. Country music singers have a repertoire of patriotic songs that are foot-stomping staples of rural county fairs and star-studded tours.

Preachers have woven patriotic threads into their sermons, presuming God has chosen sides. The political parties offer up vows of patriotism. Conservatives have staked a louder claim to the term; some say patriotism has been appropriated by Southern white men.

Even some companies find advantage in the symbolism: Jeep, Levi Strauss, Coca-Cola, and Disney usually top the annual “most patriotic brands” survey by Brand Keys, a New York marketing consulting firm.

Much of this might seem the amusing backwash of a raucous democracy, but competing claims of patriotism are helping wedge America apart. Measured by polls, hate crimes, and inflammatory rhetoric, the country is becoming more polarized than it has been in at least 50 years, when Vietnam and civil rights ripped at the social fabric.

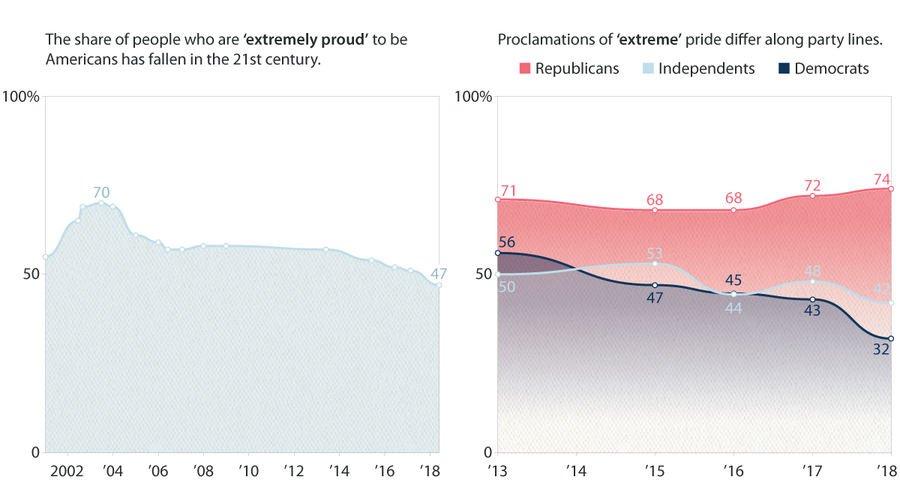

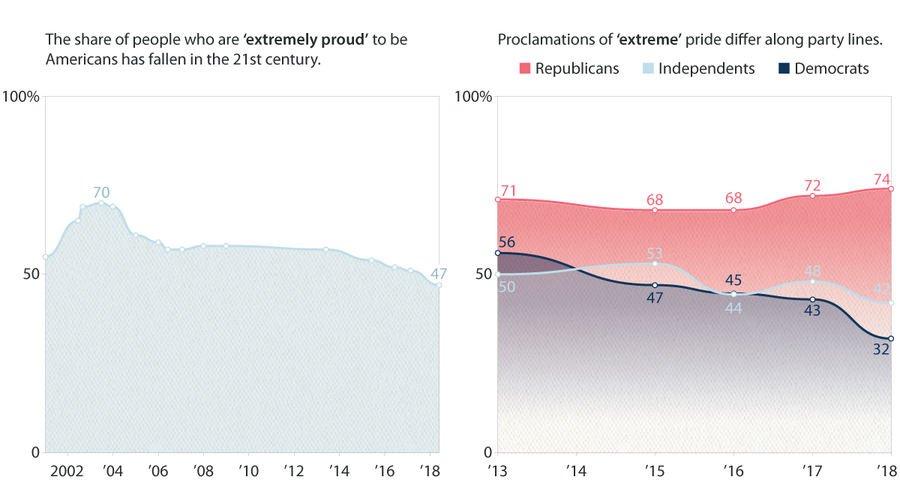

Surveys paint a somber picture. The proportion of Americans who say they are “extremely proud” or “very proud” to be Americans declined to a record low of 75 percent in March 2017, from its post-9/11 high of more than 90 percent, according to Gallup. Tolerance for other people’s views plummeted along with it.

Gallup

Trenton Whitehead runs a tax preparation business in Theodore, Ala. Orderly rows of military portraits hang on his office wall. The top row is reserved for his two sons and his niece, while his clients’ family members who served in the military fill the other rows.

Patriotism means America first, Mr. Whitehead says. It’s the unshakable love of country, even if you disagree with Washington politics. Whitehead says he is tolerant, even of the “tree-hugging liberals” ruining the country. The NFL players’ political protest angers him so much that he has stopped watching their games.

“I put my life on the line to defend their right to protest,” says Whitehead, who served in the peacetime army from 1986 to 1990. “They make millions to play a game, and then they want to stand there and tell you life isn’t fair.”

The Gallup polls found a 25 percentage-point gap between Republicans and Democrats on the question of national pride, the largest partisan gap Gallup has found since it began measuring in 2001. Soured by President Trump’s administration, fewer Democrats reported pride in their country than at any time in the past 16 years; Republicans remained high on Trump and on patriotism.

“I’ve always felt that I’m very patriotic, but it’s hard to feel proud of the country right now,” says Cindy Casterline, a retired nurse in Skowhegan, Maine. “Do you see those little children in cages?” she asks of immigrant children removed from their parents. “I can’t live with that.”

***

Patriotism is not always tinder for argument. It can be the necessary glue keeping a country together, especially in times of national threat. Aside from benefits to the country, though, social philosopher John Kleinig argues in “The Ethics of Patriotism: A Debate” that patriotism may be just as essential to individuals as to the country.

The concepts of patriotism become “part of the identity we acquire and for which we develop loyal obligations,” he writes. “It is important for our identity.”

Summers are studded with opportunities to honor those obligations: Memorial Day, Flag Day, Independence Day, Labor Day. For many, these are occasions to reflect, to gather with neighbors, to honor the good aspects of the country.

Dover, Mass., is close enough to Boston to be a suburb, but the community of 6,000 has a small-town, New England feel to it. Houses spread at the end of long tree-lined driveways. The demographic is affluent and white. About 120 residents fill folding metal chairs for Memorial Day speeches.

Robert and Kristy Dixon sit on the grass in the shade waiting for the ceremonies to begin. They describe Dover as “a very patriotic town.” Mr. Dixon points to the town cemetery, a bucolic shady knoll, neatly kept, with flags and flowers by the tombstones of veterans of every war stretching back to the Revolution.

“For everyone who thinks there’s no cost to freedom, they should walk through that cemetery,” says Dixon.

Michael Lesser, who lives in the next town over, came to Dover to see his daughter play oboe for the Memorial Day ceremony as part of the high school band. He is uncomfortable with the flag-waving displays of patriotism.

“I feel that I’m proud to be an American, but I want to feel that it’s understood. I shouldn’t have to fly the flag to prove it,” Mr. Lesser says. “I think in some sense, a flying flag suggests you are more conservative, even jingoistic, than who you really are. You can be proud to be an American but not agree with all of its policies.”

Patriotism is enmeshed with politics, and politics is a national sport. But it is one to be engaged in warily in small communities, where offenses are often long remembered.

“ ‘Don’t talk politics’ is one of three rules you have here,” says Lindsay Corson, a vision of tattooed artistry behind the bar at the South Side Tavern in Skowhegan. “It starts too many arguments.” The other two rules? “No arm wrestling. No throwing [anything].” That seemed evident, Ms. Corson suggested in a shrug.

“Even in this town it’s a mixed bag,” adds a customer, Jason Bessey, who works in the Hannaford food market. “Some people think patriotism is not criticizing our country. But patriotism like that can be bad. Look at Nazi Germany as a dark extreme. If you can’t even criticize your country, that’s a very bad place.”

Down the street, Karen Dore hustles home from her job on the housekeeping staff of Maine General Hospital. At 5:30 every afternoon she opens the door to her garage, which has been converted into a store. An eagle-bedecked sign in the yard advertises Freedom Firearms.

“It’s for the freedom to bear arms, the freedoms of the Constitution,” says Ms. Dore, still in her hospital scrubs as customers come through the door. A woman with a baby in her car plunks down a stack of $20 bills owed on a gun purchase. Ken Gordon wanders in to pick up a Colt .45-caliber revolver, a gun he recalls fondly from his 21 years in the Army.

Mr. Gordon dawdles to consider the issue of patriotism and protesting football players. “It’s just disrespectful of our country,” says Gordon. “But I respect their right to do it.”

Dore is more pointed. “I don’t think they should. I’m one of those with my hand on my heart.”

“The flag, patriotism, the Second Amendment ... it’s all mixed together,” says Dore.

***

Views of patriotism generally fall into two camps, says Peter Dreier, a professor of politics at Occidental College and author of “The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame.”

“The first is ‘my country, right or wrong,’ ” he says by phone from Los Angeles. “The other is, ‘my country, love it and fix it.’ The latter view is that my country has a set of ideals and a patriot is someone who tries to move the country toward the ideals.”

Dr. Dreier notes that many of those closely identified with the symbols of patriotism embraced the second definition. The words to “America the Beautiful” were written by Katharine Lee Bates, an ardent feminist and lesbian who protested US imperialism in the Philippines, according to Dreier.

A sort of unofficial national anthem, Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land,” penned in 1940, has this little-noticed but damning stanza: “In the shadow of the steeple I saw my people/ By the relief office I seen my people/ As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking/ Is this land made for you and me?”

Even the author of the Pledge of Allegiance, Francis Bellamy, “was a socialist who believed the country was suffering from rampant greed of the robber barons, the gilded age, the exploitation of immigrants, and the sweat shops, the slums, the racism,” Dreier says. “He thought the country could do better.”

The founders of the country were not particularly tolerant on the issue of patriotism. In the lead-up to the American Revolution and during the war, most of the new states passed “test acts” requiring all men to swear an oath of allegiance to the new union and forswear Great Britain, according to John Alexander, professor emeritus of history at the University of Cincinnati and author of “Samuel Adams: The Life of an American Revolutionary.”

These were harsh laws, Dr. Alexander says, and violators faced being stripped of legal rights or even being executed. They were designed to force the hand of a reluctant citizenry, most of whom “wanted to stay neutral,” he says. “They wanted to be left alone.”

Gradually, loyalty to a national government grew. By the Civil War, soldiers were jostling to bear their side’s respective flag on the battlefield, even though flag-bearers were often the first ones shot, according to Alexander.

Support for every war has been frothed by calls of patriotism. Stirring appeals helped usher the US into the Spanish-American War, rallied volunteers to the slaughters of World War I, and – reignited by Pearl Harbor – produced long lines at enlistment offices for World War II.

And cries of “un-patriotic” squelched dissent to wars. Aviator Charles Lindbergh went from national hero to the object of murmurs of treason for his resistance to World War II. In the white-hot passions over Vietnam, police and National Guardsmen beat and sometimes shot those protesting the country’s policies, who were seen by many as ungrateful and un-American. Cars sprouted bumper stickers that rejected dissent: “America – Love it or Leave it.” Presidential candidate George Wallace used his speeches to denigrate and threaten hecklers, singling them out as unpatriotic in a manner later mimicked by candidate Donald Trump.

Indeed, patriotism was such a useful cloak for suppressing dissent that, early on, it earned its own cynical description: “Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel,” said Englishman Samuel Johnson in 1775. The dictionary author looked scornfully at the American rebels, observing dryly that “the loudest yelps” for American liberty came from slave owners.

***

Yet while patriotism has remained a volatile issue in the country, some traditions surrounding it have withered and changed hue. Cadets from the North Quincy High School junior ROTC assemble in a parking lot across from a falafel shop for the Memorial Day parade in Quincy, Mass., eight miles south of Boston. They wear sharp blue uniforms and twirl fake rifles. There are nearly 120 of them. All but a handful are of Asian descent, reflecting the town’s demographic shifts.

Paul Moody shows up with a sun-yellow Ranger pickup truck festooned with American flags. He is commander of the Sons of The American Legion Morrissette Post. He remembers when the Memorial Day parade in Quincy was a big deal. “I think the politics hurt that. Vietnam was a political war. Afghanistan and Iraq were political. So the vets aren’t honored the way they should be.”

Fire engines, police motorcycles, marching veterans, and school bands wind their way to the Mount Wollaston Cemetery. The kids are then dismissed and melt away, leaving a small crowd of mostly older citizens gathered around a podium to hear town officials. After the speeches about sacrifice and valor, after the expectable reading of “In Flanders Field” and the unexpectedly soaring rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” by four teenagers from the high school choir, after the gun salute and taps, Robert Noble, age 92, moves resolutely with a walker toward his car.

He is dapper in a tie and coat, with a World War II pin on one lapel and another pin to commemorate prisoners of war. He was one. After the invasion of Normandy on D-Day, Mr. Noble’s unit made it almost to the German border where he was captured and held as a POW for four months, until the war ended.

He is sanguine about public patriotism. “A lot of it depends on what is happening in the country,” he muses. “There are times when veterans are particularly appreciated, and other times they are not.” He has no bitterness about that. “I just feel very fortunate to be here.”

The following week, in a makeshift federal courtroom in the heart of Boston, a crowd sits expectant and a little nervous. The big room is full. “Look at everyone here,” whispers Suma Omara. “Everyone is happy.”

Ms. Omara, a small woman in a burgundy headscarf, is from Egypt. To her right, Mirlande Jean-Baptiste, from Haiti, wears a wildly floral dress, scarlet lipstick, and dangling earrings. To her left, Canadian Barbara Curran laughs at her new friend’s observation. All would become US citizens this afternoon, taking an oath in Boston’s Faneuil Hall, a stately building that once hosted the treasonous exhortations of Samuel Adams to dump English tea in the harbor.

US District Court Judge Mark Wolf applauds the diversity of the 351 aspiring citizens before him, coming from 72 countries. But he admits that not all arms are open to them. “Some of you have experienced difficulties or discrimination because you appear to be different,” he says.

Outside Faneuil Hall, new citizen Yasameen al-Mharib acknowledges the reality of ambivalence – even hostility – toward Arab immigrants. But she notes, tellingly, “my first right is to vote.”

She fled Iraq eight years ago, lived as a refugee in Syria for six years, and now has a college degree from the Wentworth Institute of Technology in Boston and works as a computer engineer. She emerges from Faneuil Hall with her citizenship certificate and gets a hug from her high school friend, Sura Alazzawi, who also fled Baghdad, escaping to Syria then Turkey before joining her pal in Boston.

“A lot of people here supported me,” Ms. al-Mharib says. “They said I was welcome here.”

Carmen Sisson in Alabama and Jessica Mendoza in Arizona contributed to this report.

Gallup

Share this article

Link copied.

Four months from midterms, real questions about security from hacks

The security and integrity of voting systems are fundamental to democracy. Heading into the US fall midterm elections, Congress and many states are moving to address vulnerabilities – but experts say they are not doing nearly enough.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Last year, US intelligence and election-security experts issued grim warnings that alleged Russia-backed meddling during the 2016 election was merely a “wake-up call.” Now, four months from the 2018 midterm elections, it’s unclear if the United States is ready for another round of attacks. In March, Congress passed a measure providing a one-time grant of $380 million to state officials to upgrade and harden their election infrastructure. But while the money is welcome, analysts say it is only a starting point. For example, 14 states in 2016 were using voting machines incapable of producing a voter-verified paper record. Since then, only one – Virginia – has made the transition to a more secure system. Likewise, many specialists advocate statistics-based audits, using random samples of paper ballots, to verify election results and identify hacking attempts. But this year, Colorado will be the only state in the country using the technique. “This is a national security issue,” says Lawrence Norden of the Brennan Center for Justice in New York. “In that context, $380 million is almost nothing. That is what we spend on a single Air Force jet in some cases.”

Four months from midterms, real questions about security from hacks

With the 2018 midterm elections fast approaching, security experts are warning that the nation’s election infrastructure will once again come under assault by hackers seeking to undermine American democracy.

But here’s an underappreciated fact: We’re already under attack.

“We average 100,000 scans on our [computer] systems a day,” Missouri’s secretary of state, Jay Ashcroft, told a recent Senate panel examining election security. He was referring to unauthorized probing of the networks.

Mr. Ashcroft and other state election officials were asked how often they detect attempts specifically to break into voter-registration and other election-related systems.

“Every day,” responded Vermont’s secretary of state, Jim Condos. “We probably receive several thousand scans per day.”

Steve Simon, Minnesota’s secretary of state, compared the frequent attempted cyber-intrusions he sees to a car thief casing a parking lot. “[The car thief] goes there a day or two in a row, and takes out binoculars and observes traffic patterns, and he tries to figure out, is there a way in?” Mr. Simon told the senators.

“There are a lot of people casing a lot of parking lots,” he said.

Last year, US intelligence and election-security experts issued grim warnings that alleged Russia-backed meddling during the 2016 election was merely a “wake-up call.”

Now, four months from the 2018 midterm elections, it’s unclear if the US is ready for another round of election-related attacks in the cyber-shadows.

“There is a vast improvement over where we were in 2016,” says Lawrence Norden, an election expert at the Brennan Center for Justice in New York. “There has been so much more discussion and training done over the last year and a half than there ever was around cybersecurity.”

But, he adds, it is not nearly enough.

In March, Congress passed an election-security measure to provide a one-time grant of $380 million to state officials to upgrade and harden their election infrastructure.

While the money is welcome, analysts say it is only a starting point to address the full spectrum of vulnerabilities exposed during the 2016 election season.

“This is a national security issue,” Norden says. “In that context, $380 million is almost nothing. That is what we spend on a single Air Force jet in some cases.”

A paper record

For example, in 2016, 14 states were using voting machines incapable of producing a voter-verified paper record. Many of those states want to upgrade to a more secure voting system that would use paper ballots that can be hand-counted if there is a suspected breach or failure of tabulation software. But since the turmoil of 2016, only one of those states, Virginia, has made the transition to a more secure voting system.

Part of the reason for the delay is cost. It can cost tens of millions of dollars to outfit an entire state with new voting machines. Estimates are that Pennsylvania, a key swing state, may have to spend up to $60 million to replace its voting machines. Under the new federal grant, Pennsylvania is set to receive $13.5 million.

Officials in New Jersey and Georgia are actively exploring ways to buy new voting machines that support paper ballots. But they haven’t done so yet.

“It is disappointing that, given that there is pretty much uniform agreement among security experts that these systems need to be replaced, that we couldn’t manage to do it before the 2018 election,” Norden says.

Moreover, he and others are quick to point out that paper ballots alone won’t be enough to protect US elections.

Michigan has used voter-verifiable paper ballots with its voting machines since 2004. But last year, the state spent $40 million to purchase the newest version of its voting machines, with upgraded software and more robust security features. The upgrade involved replacing 5,000 machines in 4,300 voting precincts state-wide, according to state officials.

“We want to stay two steps ahead of the bad guys,” says Fred Woodhams, a spokesperson in the Michigan secretary of state’s office. “We are pleased about where we are, but we still have more work to do.”

Mr. Woodhams says Michigan was allocated $10.7 million of the $380 million in federal election security funds earlier this year. The state plans to use much of that money to hire a cybersecurity contractor to conduct a comprehensive review of the state’s election system.

“They will be looking at the whole system globally and at the local level as well,” he says. “Because there are a lot of systems that interface with each other, we wanted to see how everything works together, and where the vulnerabilities are.”

As in many states, Michigan’s election system is decentralized. Elections are conducted at the local level by 83 county clerks and 1,520 city and township clerks. While decentralization makes it harder for a hacker to disrupt or swing an election, it also makes it harder to provide a uniform defense against cyberthreats.

The same issue arises in Minnesota, where elections are run at the county level, but only nine of the state’s 87 counties are large enough to support a full-time, year-round clerk, according to Minnesota officials.

Security experts note that many election offices across the country, particularly in rural areas, do not have a single information technology specialist on staff, let alone someone trained in the latest cybersecurity threats and counter-techniques.

Following the 2016 election, many state and local election officials complained that the national government failed to provide them with real-time warnings about ongoing efforts to hack into their systems. In some cases, local officials didn’t learn of the attacks until 10 months later.

Since then, the Department of Homeland Security has set up an organization called the Election Infrastructure Information Sharing and Analysis Center. If state officials agree to participate, they can install monitors on their election networks to track and identify any potential threats. The center would then share recovered information and provide a warning system for other states.

Risk-limiting audits

Given the complexity of identifying and addressing election vulnerabilities, many election specialists advocate the use of audit techniques to help verify election results and identify hacking attempts.

Estimates are that 32 states have regulations or procedures for post-election audits. But many of these audits aren’t structured to detect a tabulation software flaw, or aren’t rigorous enough to uncover a deliberate hack, experts say.

The most robust audit available uses statistics to examine a random sample of paper ballots to verify the computer-driven tabulation of votes. Because it relies on a hand-count of a relatively small number of ballots (at least initially), these so-called risk-limiting audits provide a reliable way to double-check computerized election results.

The science has been proven and the cost is not substantial. But in 2018, Colorado will be the only state in the country using this technique to verify its elections.

“There is pretty much universal agreement that this is an important security measure to detect and perhaps recover from attacks on electronic voting systems,” Norden says. But he acknowledges: “There has been very little progress made on that front.”

Rhode Island is set to conduct risk-limiting audits starting in 2020. Pilot programs have been undertaken in Indiana and Orange County, Calif.

For the first time in 2018, Michigan will be conducting an audit of election results, by physically counting paper ballots in randomly selected precincts in each county.

“This is an avenue that might give assurance to people who are concerned about cybersecurity issues,” Woodhams says. “Every voter in Michigan will be using a paper ballot, so at the end of the day, even if everything goes wrong, we still have a paper ballot to take out and look at by hand if we have to.”

But while Michigan is ahead of many states, Woodhams acknowledges that protecting an election from outside interference will be an ongoing process.

“Cybersecurity isn’t something where you can declare victory and move on,” he says. “It is something you work on every day.”

Hope for Helsinki: Russia foresees steps on Syria, arms control, Ukraine

From Russia’s perspective, the Trump administration has been more antagonistic than his predecessor. We look at why Russians are relatively optimistic about an improvement in the relationship.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

To all appearances, the Kremlin couldn't be happier about the July 16 meeting between President Trump and Vladimir Putin in Helsinki, Finland. While Russian experts caution that no diplomatic breakthroughs are likely, they are taking the White House's offer to meet as a sign that the neo-cold-war chill that began under Barack Obama has finally reached rock bottom. Even though relations between the United States and Russia began to sour during the Obama administration, Mr. Trump has acted more antagonistically to the Kremlin than Mr. Obama on multiple fronts. Now, just the fact that the meeting between Trump and President Putin is happening may be enough to turn the relationship around, many Russians hope. “Despite the tremendous damage to the Russian-American relationship over the past year and a half, there is a stubborn belief among Russian leaders that Trump really wants to work to improve things,” says Sergei Strokan, foreign affairs columnist with the Moscow business daily Kommersant. “We are desperate enough to believe that things have hit the bottom, and there's nowhere to go but up.”

Hope for Helsinki: Russia foresees steps on Syria, arms control, Ukraine

At least from Moscow's viewpoint, it's been a disastrous year and a half for Russian-American relations.

President Trump's campaign promises to “get along with Russia” excited the hopes of many here. But in fact, he delivered the most acrimonious, sustained downward spiral the relationship has seen in almost four decades, leaving many Russians gripping their heads in frustration.

Now he wants a summit?

But to all appearances, the Kremlin couldn't be happier about the July 16 meeting between Mr. Trump and Vladimir Putin in Helsinki, Finland. While Russian experts caution that no diplomatic breakthroughs are likely, they are taking the White House's offer to meet as a sign that the neo-cold-war chill that began under Barack Obama has finally reached rock bottom.

And some, looking at the partisan chaos in the United States through the prism of Russian political culture, see signs that Trump is finally whipping his rivals into line and asserting his will as a strong president should. Indeed, at his meeting with White House National Security Adviser John Bolton last week, Mr. Putin singled out “sharp domestic political strife” in the US as the main reason such a summit has only now become possible.

“The relationship has been a complete mess [under Trump], and US policy toward Russia has been incoherent and unpredictable. We believe the situation is outright dangerous,” says Sergey Karaganov, an influential senior Russian foreign policy hand. “The atmosphere is still toxic, but it looks like Trump is winning” in his battles with the Washington establishment.

In that case, Mr. Karaganov says, it might be possible to move forward on a variety of urgent issues when the two presidents meet, including Syria, arms control, and maybe the ongoing crisis in Ukraine. It might even be possible to start talking about a “grand bargain,” a sweeping modus vivendi between Russia and the US that some Russian optimists read between the lines of Trump's campaign rhetoric.

‘Nowhere to go but up’

While relations between the US and Russia began to sour during the Obama administration, Trump has acted more antagonistically to the Kremlin than Mr. Obama on multiple fronts. That's a primary reason why the debate going on in the US over whether Trump is under Kremlin influence doesn't pass the smell test among Russians.

Obama avoided getting involved in the Syrian war, and even partnered with Russia in a deal to eliminate Bashar al-Assad's chemical weapons arsenal. Trump has twice unleashed cruise missile strikes against Syria over alleged chemical weapons use. Obama avoided supplying lethal weapons to Ukraine. Trump has sent cutting-edge Javelin anti-tank missiles for use by Kiev's forces.

Sanctions against Russia were initiated by Obama after Russia annexed Crimea and got involved in the eastern Ukraine anti-Kiev rebellion, but they have multiplied and become seemingly irreversible under Trump. Obama kicked out a large number of Russian diplomats over allegations of Moscow's interference in US presidential elections, but Trump topped him by ordering the biggest expulsion of Russian envoys in history.

Now, just the fact the meeting between Trump and Putin is happening may be enough to turn the relationship around, many Russians hope.

“Despite the tremendous damage to the Russian-American relationship over the past year and a half, there is a stubborn belief among Russian leaders that Trump really wants to work to improve things,” says Sergei Strokan, foreign affairs columnist with the Moscow business daily Kommersant. “We are desperate enough to believe that things have hit the bottom, and there's nowhere to go but up.”

“Just by the fact of holding the summit, even if they talk about nothing, Putin and Trump are sending a clear signal to their respective administrations, political classes, and publics that improved US-Russian relations is still on the agenda,” Mr. Strokan says. “Psychologically, the atmosphere changes. In fact, it might be best if we just get a vague statement of principles, like the one that emerged from the Singapore summit with North Korea, because it will create an upbeat mood ahead of the long, tough negotiating that will have to follow.”

Areas for common ground

Some practical deals are possible, even in a brief meeting that is mostly about optics, say Russian analysts.

A key issue is Syria, where the US appears to have already conceded that the Obama administration's longstanding goal of regime change is off the table. “I don't think Assad is the strategic issue. I think Iran is the strategic issue,” Mr. Bolton told Face the Nation on the weekend.

In exchange for the abandonment of US support for the anti-Assad rebels, Russia could agree to help limit Iranian influence in post-war Syria, especially near its borders with Israel. Indeed, it seems clear that Russia and Israel, who maintain good relations, have been talking about something like this for quite awhile.

“We have good relations with Iran, and we might be able to use our influence to shape a workable deal,” says Karaganov. “It's a very complex problem, and we'd need to get something in return.”

An easy deal for Trump and Putin would be to agree to open talks on extending the New START strategic arms reduction treaty, which will expire in less than three years if no action is taken, leaving the world's two nuclear superpowers with no agreed framework of strategic arms control for the first time in more than four decades.

Another step could be to set up a special commission to fix the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty, the deal that ended the cold war 30 years ago but now looks to be on the critical list.

The simmering war in eastern Ukraine has so far defied all diplomatic efforts at resolution, and doesn't look susceptible to any quick solutions now.

“We are in a corner in Ukraine. Putin wants to solve it, but where to begin?” says Alexey Mukhin, director of the independent Center for Political Information in Moscow. Last week Trump hinted that he might be willing to recognize Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea, because “everyone there speaks Russian.”

Some agreement on Crimea would have to be part of a “grand bargain,” but no one in Moscow is looking for anything like that out of the Helsinki summit.

“We are going to this summit because there is no alternative,” says Mr. Mukhin. “When Putin meets Trump, it will be just the start of a long and difficult conversation that might lead to a more sane and predictable relationship down the road. Right now, I think we will be satisfied with just having the summit.”

Back to Tulsa: An experiment offers three families hope for American dream

To help children break out of a cycle of poverty, an Oklahoma experiment doesn’t simply assist the children. It also helps their mothers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 11 Min. )

Hayzetta Nichols was once labeled a “hellbound child” by a judge and cycled through 28 foster families by age 13 before she found the woman she calls “mom.” Today, Ms. Nichols and her own children are part of a bold philanthropic initiative to unleash the potential of disadvantaged kids in Tulsa, Okla., a city of 400,000 once known as the oil capital of the world. Its richest resident, George Kaiser, has pledged much of his fortune to building a public-private safety net for young families in a state that is largely notable for its absence. His family foundation is focusing on children’s learning from birth until third grade, a multiyear bet on sustained early intervention to deliver scholastic success to the most needy, including black and Latino families. The Monitor is following three mothers whose lives are touched by Mr. Kaiser’s philanthropy, from quality day cares and early-reading classes to prison-diversion programs and family planning. Their struggles show the challenges of raising children in trying circumstances and the potential of targeted philanthropy to help parents to break cycles of poverty and neglect. This is Part 2 of a yearlong series. To read Part 1, click here.

Back to Tulsa: An experiment offers three families hope for American dream

It’s 94 degrees F. in the midday sun as Hayzetta Nichols steers her fully loaded baby stroller past a row of broiling cars. Her two other children toddle beside her and Lavelle, her husband, headed for the welcoming chill of a multiplex matinee.

Normally all three kids would be at daycare but it’s closed for staff training. Since it’s also Ms. Nichols’s day off work she has decided to take the family to the opening day of “Incredibles 2.” She plans to nap once everyone settles down in the front-row recliners. But she’ll also pump extra breast milk for Loyal, her three-month-old daughter, just as she does on her daily breaks at the call center.

For Nichols, multitasking is just another word for making it.

“How do I do it? I just do it. There’s no in between, there’s no trying. You gotta get out there on that ledge and go for it. That’s part of being a mom,” she says.

Nichols is part of a bold philanthropic initiative to unleash the potential of disadvantaged kids in Tulsa, a city of 400,000 once known as the oil capital of the world. Its richest resident, George Kaiser, has pledged much of his fortune to building a public-private safety net for young families in a state that is largely notable for its absence. His family foundation is focusing on children’s learning from birth until third grade, a multi-year bet on sustained early intervention to deliver scholastic success to the most needy, including black and Latino families.

Oklahoma’s schools were in the spotlight in April when teachers walked out to demand – and got – higher pay and more spending on education in a state that ranks among the least generous. While the George Kaiser Family Foundation (GKFF) has invested in public-school programs and the district’s leadership, its largesse can’t replace core funding of education and other state programs.

The Monitor is following three mothers whose lives are touched by Mr. Kaiser’s philanthropy, from quality daycares and early-reading classes to prison-diversion programs and family planning. Their struggles show the challenges of raising children in trying circumstances and the potential of targeted philanthropy to help parents to break cycles of poverty and neglect.

Above all, the Tulsa Experiment – an experiment in which the participants shape the outcome – is an attempt to restore the American Dream to those perhaps least able to hold onto its promise.

It’s been three months since Alexis Stephens completed Women In Recovery, a Kaiser-funded prison-diversion program, which allowed her to start over after years of addiction and to reunite her with her two children. Today she’s picking up Addison, who was born while Ms. Stephens was incarcerated, from daycare and driving across town to her mother’s house, where Carson, who just finished third grade, is waiting to go to his Cub Scout cookout.

At a nearby park, men in shorts mill around a grill, while a gaggle of young boys toss a football and dart between playground rides. Carson peels away to join them. “What’s Bubba doing?” Stephens asks Addison. “Is he pushing the boys” on the merry-go-round?

Addison, a toddler enamored of her newfound speed, kicks off her shoes and skips over the grass toward a fishing pond, where a fountain sprays water into the warm evening skies. Stephens, who wears a black sundress, chases after her, leaving her mother, Claudia, sitting on a bench.

Claudia has been a constant in Carson’s quicksand childhood, his legal guardian while Stephens was addicted and homeless; Claudia wrestled him away from his father, who has since been sent to federal prison for drug trafficking. Now, Stephens is sober and has a car and a steady office job. Carson lives with her and Addison in a downtown women’s shelter.

When she was struggling with addiction, Stephens moved frequently with Carson, fearful of Child Protective Services taking him away. They lived in rented apartments, rarely well maintained. “I don’t want that life for my kids. I want stability for them. They deserve that,” she says.

Lindsey House, the women’s shelter, has strict rules for its residents: no messy apartments; a 10 p.m. curfew; savings program in lieu of rent. No men. (She is dating a man she met online, but they have to meet elsewhere.)

“I still have the accountability and structure here that I have to live by,” says Stephens. “I come home every day after work to a clean house because I have to clean my house every day.”

Not long after Stephens finished her 18-month recovery program, she left Carson sleeping on the sofa. It was Saturday morning, and Stephens needed to service the breathalyzer in her car that’s a condition of her holding a license. She figured it would take under an hour, and if Carson woke up, he could find the mom upstairs who babysat for him.

In that hour, the stability that Stephens had worked so hard for nearly fell apart.

When Carson woke from his nap, his mom wasn’t there. He looked out the window and saw a police car parked outside. He walked out the front door, went up to a police officer, and said, “I can’t find my mother.”

By the time Stephens rushed back, after a frantic call from Lindsey House staff who spotted the cop and Carson outside and intervened. The policeman was waiting in the office. He knew her criminal record, her probation rules, Carson’s status.

“I was extremely calm because what I represent has to represent what I am right now,” she says. She listened to the officer, and agreed that it was wrong to leave Carson alone. He said he wouldn’t write her a citation but that the incident would go on her record.

What she feared most – losing her children, going back to jail – didn’t transpire. “It could have gotten bad. It could gotten really bad,” she says.

Now there’s a handwritten list on the fridge of emergency numbers to call. That the incident happened at Lindsey House, where staff could vouch for Stephens is another reason why she’s loath to leave next month. She’s hoping for an extension so she can prepare for the next step, save enough, perhaps, for a down payment on a house with a yard and a bedroom for Carson, who sleeps on a bunk above her bed.

“I’m going to lose a lot when I move out of here,” she says. “If you need creamer in the morning, you’ve got a friend. If you need someone to get your kid off the bus in the morning, you’ve got a friend.”

Trash bin. Spray bottle. Bucket. Latex gloves.

Check.

Mikaleah Moment pushes her way into a recreational room where a dozen or so seniors and their caregivers sit at tables bathed in the blue glow of a daytime game show. Some are doing crossword puzzles or reading catalogs. Tulip-shaped paper streamers hang from the ceiling.

Ms. Moment wheels her bucket to the men’s bathroom to start cleaning and mopping. In an hour she’ll be done with work and ready to collect her daughters from Educare, an early-learning center built and funded by GKFF. For now, she considers this job at a seniors day center a find – $11 an hour, no weekends, walking distance from home. (A week later she quit the center to work at a gas station.) “I change jobs like I change my clothes. But I always keeps me a job,” she says.

Her last job, serving food at a Tulsa hospital, was even better, she says, but it ended abruptly after Educare called to say Jo’Nae, her 3-year-old, was waiting to go home. She called the father who was supposed to collect her; he told her he was at the mall. “I told the manager I have no choice but to leave now,” she says, shaking her head at her ex-boyfriend’s behavior. She was fired, and never went back.

For staff at Educare, which serves low-income children who start as early as six weeks, this is familiar terrain. Family units are rarely nuclear. Fathers may be involved or cohabitating, and share some parenting duties, but the primary caregiver is inevitably the mother.

For Moment, that’s been her life since she was 15. Her mother died the previous year, just as Moment was about to become a teen mom herself. R’Myah – whose father is Moment’s current boyfriend, Rande – was born last August. Moment lives with her children at the house of her late grandmother, a retired schoolteacher who pushed Moment to finish high school.

Which is how Moment, now age 18, finds herself the head of her household. There are rules: Clean up after yourself. No visitors after 11 p.m. Proper meals, not junk food.

She’s dismissive of young mothers who can’t cook. “I know how to be a real mom. It’s not just, ‘buy them stuff.’ You got to nurture, learn with them, teach them, work with them,” she says.

After R’Myah was born, Moment began using a long-acting contraceptive, a program supported and funded by GKFF.

She has two younger siblings: a troubled half-sister, 16, who insists that she wants a baby, too – “This is not what you want,” she tells her – and a brother who’s entering his senior year of high school. The last time she saw him, he blurted out that he was going to be a father.

“Congratulations. But I’m going to kill you,” she told him.

Like Stephens, Moment plans to move. She has visited apartments for rent, figuring she can find a tenant for her grandmother’s old house. It holds too many memories, not all warm, and Moment feels the weight of it on her narrow shoulders. Moving is “a fresh start,” she says.

At home, Rande helps with parenting and brings her lunch when he’s not working for his father’s construction business. Ask about Rande’s family, and Moment’s face lights up. “His daddy is the daddy I never had. If I need help doing something he’s right there,” she says.

Rande’s family was also Moment’s introduction to rodeos and horses. The first time she met him he was wearing cowboy boots, fresh from practice. Soon he was taking her to his grandfather’s stable to teach her how to ride, and she bought her own horse, Gojoe, a thoroughbred.

Riding “is like therapy,” she says. “It’s soothing. I could be extremely upset but I go there and start riding that horse and I’m calm and cool.”

On a recent Saturday, it was rodeo night in Owasso, 10 miles north of Tulsa. Rande drives a pickup truck and horse trailer, while Moment follows with the girls in her dented gray Camry. The sun is setting behind a hill overlooking a ploughed fenced field flanked by a rusted green bleacher, as scores of riders and horses gathered by the pens. The crowd in the bleachers is a mix of families, black and white, and young and old cowboys; the air is thick with sweat and dung and hay, and a sweet smell of another kind of grass.

Moment, who wears jeans, purple-and-tan cowboy boots, and a colorful zig-zag blouse, hoists herself up onto her saddle. Her turquoise purse swings at her side. Jo’Nae is placed in front, holding the reins.

“You see that pony?” says Moment, pointing to a small girl on horseback. “Maybe I’m going to get you one like that.”

“It’s cute,” says Jo’Nae.

“Yeah. Maybe I’ll get you one.”

“Then I have one horse. 1, 2, 3, 4.”

“We’ll need a bigger trailer,” says Moment.

Loyal arrived in March, right on time. Since then, Nichols has gone back to work, used her tax credits to buy a used SUV, and has bought new furniture and a washer and dryer for their rented house. Come August, she wants to re-enroll part-time at Tulsa Community College and earn more credits towards a social-work degree.

“Everything is looking up,” she says.

For Lavelle, work has been more fitful. His record – he served prison time for assault – makes it hard to get a job, even when he enrolled in a program, which GKFF funds, that helps former felons to transition into work. He had at least four interviews, but no callbacks. “How is he supposed to get a job without someone at least giving him a chance to try?” sighs Nichols.

His dream job, says Lavelle, a former boxer, is to be a car mechanic, a skill he picked up from his father growing up in Arkansas, one of 10 children.

For now, he’s picking up yard work and other casual jobs. Every month, he has to appear before a judge and pay $40 in probation fees. This month he took Loyal along, scooped her into his arms and walked into the courtroom. “Everyone changed when they saw her,” he says, laughing at how the judge and court officers lightened up at the sight of a smiling baby.

Like her sister, Myracle, 3, and brother, Lijah, 1, Loyal has begun attending Educare. Nichols is thrilled at the progress her children are making – their vocabulary and curiosity and poise – and is glad that Myracle is moving up to preschool, away from Lijah, whom she says is overprotective of his older sister in classroom squabbles. “He’ll just come over there and hit you because he can’t get his words across. That’s why I’ve been working with him” on using his words, she says.

Nichols knows the power of proactive parenting. By the time she turned 13, she had cycled through 28 foster homes and been expelled from school for fighting; her judge called her “a hellbound child” who required 24-hour supervision. The foster parent who turned her life around was a single mother, a social worker who was taking college classes.

“She knew she had a challenge ahead, and I guess that’s what she signed up for,” she says.

Nichols says her “mom,” as she calls her, was patient and firm. Under her protective wing, Nichols put her angry fists down and graduated top of her high school class in Morris, Okla. (She also reconciled with her birth mother, who lives in southern Oklahoma.)

“Knowing that I had such a strong woman providing for me I knew that I could do the same thing when the time came,” she says.

Back at the cinema, the family has settled in for the movie. Lavelle hands Loyal over to her mother, who is helping Myracle to refill her lemonade. Blankets from home are passed out. Lijah climbs over for a cuddle, then nods off. Nichols gently lays him back on his oversized recliner.

On the screen, Edna Mode, the fashion designer, is dispensing advice to Mr. Incredible, whose three kids are proving a handful. She tells him: “Done properly, parenting is a heroic act.”

Part 1: Tulsa experiment: Can investing in children early reverse poverty cycle?

How a surge in political humor drove young Colombians to the polls

American college students often get their news from late-night TV comedians. But when fear flushed political satire from the airwaves in Colombia, it reemerged on YouTube, inspiring a new generation to laugh – and vote.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Rebekah F. Ward Contributor

Colombia recently elected its next president in a hotly anticipated runoff election. Voter turnout this year was historic – about 53 percent – with many first-time voters pointing to the role of new, online political humor programs as waking them up to the importance of getting involved and casting their ballots. With a media landscape long associated with political parties, online humor programs entered the political conversation, helping many voters find their voice in the conversation. For example, the on-screen personality of Maria Paulina Baena, the face of the show “La Pulla,” appears frizzy-haired, without makeup, wearing a masculine jacket and tie – and she's angry. Through her frustration, she channels some of the powerlessness felt by the Colombian public. And for this election, it struck a chord. “Satire is very important in a country where many people are scared to say what they really think,” Juanita Léon, head of political website La Silla Vacía, says of Colombia’s long history of violence. “It becomes the place where truths are said without fear.”

How a surge in political humor drove young Colombians to the polls

A week before Colombia’s June presidential run-off, Sebastián Os was perched in the second row of Bogotá’s crowded national theater. Ecstatic, the teen sat just a few feet away from the star of the show, his unlikely hero: a middle-aged political humorist and YouTube celebrity Daniel Samper.

Mr. Samper’s online series, “#HolaSoyDanny” (Hi, I’m Danny), has developed a huge following across Colombia. His show, and the equally popular “La Pulla” (The Taunt), have become the politically minded antiheroes of Colombia’s YouTube generation – which is more accustomed to watching fresh-faced teens perform complicated stunts or makeup routines online.

“I only started learning about serious politics with Daniel,” says 17-year-old Sebastián, who began following “#HolaSoyDanny” earlier this year. “At first I was like, ‘no, anarchy! I don't like politicians!’ But then with Daniel's videos, ‘I was like, this is interesting.’ ”

Sebastián first watched Samper for the entertainment value. But then he started reading the news to be sure he would “get” all of Samper’s jokes. Now, Sebastián is part of a growing trend among young Colombians who may consider all politicians as homogeneous, but who are waking up to the importance of following the news – and casting ballots.

Colombia’s recent presidential election saw voter turnout at a 20-year high. New-voter registration rates nearly doubled those of the last presidential election, suggesting an uptick in youth registration. The higher levels of engagement reflect the high stakes and divisions in this election. The two candidates held views on opposite ends of the political spectrum, and the controversial peace process brought to fruition by President Juan Manuel Santos in 2016 polarized voters who disagree on how demobilized fighters should be treated.

A handful of government and nongovernmental-organization efforts focused on mobilizing voters this year, like youth-focused get-out-the-vote campaigns and mock election events. But, in this tense climate, political humor – online, unfettered, and reaching into the millions of viewers per video – has proven one of the more popular tools in making sense of the political environment, analysts say. As these programs continue to attract followers, there’s hope that the medium will further increase political conversation and engagement here.

“Both ‘La Pulla’ and Daniel Samper remind us that political humor is necessary, that it had been something missing in” our news coverage, says Maria Alejandra Medina Cartagena, a communications researcher and journalist. “What makes it successful … is to be able to criticize everything that is wrong, everything that needs to be criticized” in a way that broadens the conversation beyond political elites.

Filling a gap in traditional media

It is no coincidence, according to Ms. Medina, that “#HolaSoyDanny” and “La Pulla” came out in the spring of 2016. Colombia's two main television stations removed all of their political humor programs in 2013, her research found. At the time, there was a broad fear of alienating audiences and losing money – as well as self-censorship. In 2013, political polarization was already growing, as popular ex-President Álvaro Uribe split from his successor and former minister of defense Santos over how to resolve Colombia's 50-year civil conflict, which left more than 200,000 people, mostly civilians, dead.

At the same time, Colombia experienced a burst in online video consumption, according to Google data. The nation’s monthly YouTube users ballooned to 24 million in 2016, half of the country’s population. Between 2014 and 2015, the site’s visitors increased by 75 percent.

Though YouTube and online comedy stars are a new phenomenon here, Colombia long examined its political situation through humor, says Juanita Léon, head of political website La Silla Vacía.

“Satire is very important in a country where many people are scared to say what they really think,” Ms. Léon says of Colombia’s long history of violence. “It becomes the place where truths are said without fear.”

Humor doesn’t equate a lack of seriousness in reporting. Samper and the team from “La Pulla,” for example, are professional journalists with backgrounds at some of Colombia’s biggest, most reputable print publications.

The lack of barriers to entry on YouTube allowed them to take their reporting chops and present them in new ways online. Both these shows stand out for their basic formulas: rapid-fire, talk-to-the-camera aesthetics, without a lot of bells and whistles.

“It is recorded with a cell phone, there is no big production, there are no people doing makeup, there are no lights, there are not 20 people on set. Many times my 9- and 10-year-old daughters record it, or my wife,” Samper says. “This is the format of our times: homespun videos, hosted on the internet absolutely free… it was a way to mainstream satire.”

Shifting the political discourse

Even with low production value, the topics tackled by these programs are robust. Extensive research goes into each episode.

“We do this because we’re trying to give people tools to think about the reality they’re living in, and for us, that’s only possible through satire,” Juan David Torres, one of three young journalists behind “La Pulla,” says. “Our final goal is to tell people, well, this is important for you because it is affecting you. Maybe it’s harming you. Maybe sometime in the future, it will hurt you. So you really have to pay attention.”

For Mr. Torres, that has also meant using a relatable tone – almost the opposite of what Colombians see in their nightly news anchors. The on-screen personality of Maria Paulina Baena, the face of “La Pulla,” appears frizzy-haired, without makeup, wearing a masculine jacket and tie – and she's angry. Through her frustration, she channels some of the powerlessness felt by the Colombian public. And for this election, it struck a chord.

“Normally, the comment we get is that people weren’t interested in politics until ‘La Pulla’ came around,” Ms. Baena says.

Colombia has historically struggled with voter turnout, but saw 53.4 percent of the population at the polls in the final presidential election. And while other factors weighed in, new voters – many of them the young YouTube audiences – played a key role.

“La Pulla” released videos criticizing each candidate; episodes on the final contenders, Ivan Duque and Gustavo Petro, were viewed almost two million times each. “#HolaSoyDanny” featured a 2-hour live “YouTubers vs. Candidates” debate, where he brought in young, non-political YouTube personalities to question three of the candidates face-to-face.

Even these politicians knew that their online presence mattered.

According to Santiago Castaño, a university student in his early 20s, YouTube humorists like “La Pulla,” “#HolaSoyDanny,” and “Me Dicen Wally” are his main sources of political news. In a country where many traditional outlets are linked to political parties, Mr. Castaño feels that these overtly opinionated YouTube satirists are in the best position to start a dialogue.

“I think they’ve had a huge influence on the political debate among Millennials,” he says. They criticize political parties indiscriminately, and while they are transparent about their own perspectives, “they don’t try to impose on you what to think.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

An impending revolution in Mexico

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

With the election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as Mexico’s next president, the world will have the opportunity to see how one leader will approach ending corruption. Will he overhaul institutions or try to change public attitudes? Much in such a decision depends on a leader’s view of people. In his victory speech, Mr. López Obrador emphasized what he sees as the innate goodness of everyday citizens. He said his first request of Congress upon taking office Dec. 1 would be to change the Constitution and allow a sitting president to be tried for corruption. He promised to spare no one in rooting it out. He sees in his election a “revolution of consciences,” or the public expression of the “love, morality and love of neighbor” that lies within the people. Many historical figures, such as Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., have put a strong emphasis on a “revolution of conscience” to achieve change. If AMLO, as he is known, means what he says, then Mexico may be about to experience another revolution.

An impending revolution in Mexico

In many democracies, a new leader who wins an election with an anti-corruption platform might lean toward one of two choices: Overhaul corrupt institutions or change public attitudes that accept and perhaps even expect corruption.

Fix the system or fix the culture? To put it another way, does the problem lie mainly in societal attitudes or in how attitudes are altered and abused by corrupt practices from on high?

Much in such a decision depends on a leader’s basic view of people.

Now, after the election July 1 of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as Mexico’s next president, the world will have the opportunity to see how one leader will implement such a choice.

In a victory speech, Mr. López Obrador clearly blamed a corrupt ruling elite, or what he called “the mafia of power,” while emphasizing what he sees as the innate goodness of everyday citizens.

Many observers, he stated, claim corruption is part of Mexican culture. “That is a falsehood. A big lie,” he counters. “In our people, there is a great reserve of values, cultural, moral, spiritual, in the families, in the pueblos, in the communities.”

“The problem is above,” he said, pointing upward. “The rulers always set a bad example.”

To make his point, he promises to set himself up as a moral icon upon taking office Dec. 1. He will start by converting the presidential palace into a public park and forgo the perks of office. He said his first request of Congress would be to change the Constitution and allow a sitting president to be tried for corruption. He also promises not to spare colleagues, friends, or family members in rooting out corruption. He cites a common saying, “A good judge begins at home.”

López Obrador, commonly known by his initials, AMLO, believes so much in the power of leading by example that he did not even offer a plan to change government structures to prevent corruption or ensure that rule of law prevails among Mexican police, prosecutors, and judges. He dismissed the role of civil society groups that have long offered ideas for government reform.

A corrupt system will end, he believes, “because the president won’t be corrupt.” He sees in his election a “revolution of consciences,” or the public expression of the “love, morality and love of neighbor” that lies within the people. His core message to Mexicans: Don’t be corrupt, and if you see it, report it. He also seeks to implement a vague “reconciliation” plan that would offer some kind of mercy to corrupt leaders and to many of those involved in organized crime.

AMLO’s views will challenge a common notion in Mexico that people are born with evil hearts. He says that by setting an example and selecting good appointees he can cut crime in half and achieve “complete eradication of political corruption.” And he won’t need to raise taxes to fulfill his leftist anti-poverty goals because, without corruption, government will have more money and be more efficient. Indeed, the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness estimates corruption eats away 2 to 10 percent of gross national product and reduces foreign investment by 5 percent a year.

During his campaign, AMLO tapped into a deep public cynicism toward the ruling parties that have governed Mexico since the end of one-party rule in 2000. Last year, according to pollster Latinobarómetro, only 18 percent of Mexicans said they were satisfied with democracy. The country has also experienced record levels of violence. Yet as real democracy has taken hold, and Mexican youths learn to use social media for civic activism, voters appear ready for radical change.

Is Mexico’s incoming president being too naive? Is he wrong to assume that individuals are sovereign in their thinking and only yield some of that sovereignty to the rulers of their choosing? Can the corrupt in government, business, and organized crime be made whole by someone setting good examples for them and by offering them ways to reform?

Most corruption fighters around the world rely on a belief that people naturally want openness, integrity, and accountability in both their private and civic lives. Yet such activists often go beyond setting examples or a code of ethics. They want governing structures with strict rules and stiff penalties. When AMLO was mayor of Mexico City, he opposed such measures, such as a “freedom of information” law.

Mexico is currently one of the world’s most corrupt countries. Yet one leading expert on corruption, Romanian political scientist Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, provides this advice: “It would be wrong to believe that a country is entirely doomed by poor history.” Many historical figures, such as Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., have put a strong emphasis on a “revolution of conscience” to achieve change.

If AMLO really means what he says and attempts to implement his plans for ending corruption, Mexico may be about to experience another revolution. At the least, he could shift the needle on the age-old question about the origins of corruption toward an ideal of civic life based on the good to be found in others.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A fuller freedom

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

Today’s column includes a poem and quotes that point to our inherent freedom and unity.

A fuller freedom

God made all His creatures free;

Life itself is liberty;

God ordained no other bands

Than united hearts and hands.

One in fellowship of Mind,

We our bliss and glory find

In that endless happy whole,

Where our God is Life and Soul.

So shall all our slavery cease,

All God’s children dwell in peace,

And the newborn earth record

Love, and Love alone, is Lord.

– James Montgomery, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 83, adapt. © CSBD

You will know the truth, and that truth will give you freedom.

– Christ Jesus, John 8:32, “The Voice”

Like our nation, Christian Science has its Declaration of Independence. God has endowed man with inalienable rights, among which are self-government, reason, and conscience. Man is properly self-governed only when he is guided rightly and governed by his Maker, divine Truth and Love.

– Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 106

A message of love

In World Cup’s shadow, a higher-stakes game

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Tomorrow Monitor editors and writers will be off, enjoying Independence Day in the United States. But watch for a special email about the Fourth of July from correspondent Martin Kuz, who spent three years covering US troops in Afghanistan.