- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Manafort trial: Russia-probe origins, but a main focus on fraud

- From tear gas to tweets: 50 years in the evolution of US activism

- On election day, ‘new Zimbabwe’ looks closer – but still far away

- In Malaysia, a new attempt to know one’s neighbor – and his faith

- A North Dakota school district tosses old lesson plan, and more

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for July 30, 2018

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

So often, news is about the ways that violence is trying to subvert peace. But recent events in Afghanistan, of all places, are offering a glimpse of the reverse.

Reports from numerous media outlets suggest that the Trump administration has begun preliminary direct peace talks with the Taliban. They are the first such high-level talks in three years and mark a departure from the policy of previous administrations that only Afghanistan could lead negotiations. The moment has lit a spark of anticipation.

But this moment, most agree, grew out of something else: a unilateral, three-day cease-fire declared by the Afghan government during the Eid al-Fitr holiday last month. The response was extraordinary. Taliban fighters wandered into cities, where citizens and even local governors embraced them and took selfies. Insider reports suggest Taliban leadership was livid. Why? The Taliban have momentum, and peace could undermine that.

Yet it sprang up everywhere. “What happened over Eid was deeply subversive, politically and militarily dangerous to any party wanting to prolong the conflict,” wrote the Afghanistan Analysts Network. “It demonstrated that a ceasefire, held to completely by both sides, is possible. It revealed a strong peace camp among Afghans that crosses frontlines, and it opened up the imaginative space for Afghans to see what a future without violence could look like. Perhaps most significantly, it allowed human contact between enemies.”

It has also set a clear task for US and Taliban negotiators: What is the next deeply subversive act they can take for peace?

Here are our five stories for the day, including how the protests of 1968 echo in America today, a child's-eye view of the new Zimbabwe, and lessons from Malaysia on the emerging desire for deeper understanding among religious groups.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Manafort trial: Russia-probe origins, but a main focus on fraud

Beginning tomorrow, Paul Manafort will become the first target of Robert Mueller’s Russia investigation to stand trial. Here's a look at what to expect.

While jurors in the three-week trial of Paul Manafort will be shown substantial evidence of his taste for expensive items, prosecutors told US District Judge T.S. Ellis that they will not seek to admit evidence or make any argument at this trial concerning Russian collusion. Rather than facing election-meddling conspiracy charges, Mr. Manafort, a longtime political operative and former Trump campaign chairman, is standing trial on allegations of tax evasion, bank fraud, and money laundering. It is unclear whether investigators have discovered evidence of collusion involving Manafort and the Russians. Some analysts view the case as a tactic to exert pressure on Manafort to cooperate with prosecutors in the broader Trump-Russia investigation. To others, the absence of a Russian conspiracy in the impending case suggests that Robert Mueller’s team may have found no evidence of collusion. “The government is quite happy to make this a relatively simple case about fraud. He got money, he lied about it, didn’t tell the IRS, didn’t tell the banks, and got rich doing so,” says Paul Rosenzweig, a former prosecutor on the staff of independent counsel Ken Starr during the investigation of President Bill Clinton. “That is a simple story to tell. If they believe the evidence, jurors are not going to have trouble convicting Manafort.”

Manafort trial: Russia-probe origins, but a main focus on fraud

One year ago, on July 25, 2017, FBI agents working with special counsel Robert Mueller presented a thick stack of papers under seal to a federal magistrate in Alexandria, Va.

They were requesting authorization to search the condominium of former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort for evidence of tens of millions of dollars he allegedly concealed from US authorities.

Among the items they were looking for: a $21,000 Bijan black titanium wristwatch, multiple $10,000 custom-made suits, and two silk oriental rugs valued at $160,000.

But the search wasn’t just about cataloging various indicia of Mr. Manafort’s wealth. The warrant also sought bank records, wire transfers, emails, loan applications, and a slew of other documents, both paper and digital, related to virtually every aspect of the political consultant’s personal life, businesses, and finances.

In essence, the agents were working to “follow the money,” in an attempt to unearth evidence that President Trump’s former campaign chairman colluded with Russians to disrupt and undermine Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign.

This week, the fruit of that July 2017 search will be on display in federal court. But rather than facing election meddling conspiracy charges, Manafort is standing trial on allegations of tax evasion, bank fraud, and money laundering.

It is unclear at this point whether investigators have discovered evidence of collusion involving Manafort and the Russians. Some analysts view the tax evasion and bank fraud case as a tactic to exert pressure on Manafort to cooperate with prosecutors in the broader Trump-Russia investigation. To others, the absence of a Russian conspiracy in Manafort’s impending case suggests that Mueller’s team may have found no evidence of collusion.

“The government is quite happy to make this a relatively simple case about fraud. He got money, he lied about it, didn’t tell the IRS, didn’t tell the banks, and got rich doing so,” says Paul Rosenzweig, a senior fellow at the R Street Institute and a former prosecutor on the staff of independent counsel Ken Starr during the investigation of President Bill Clinton.

“That is a simple story to tell,” Mr. Rosenzweig says. “If they believe the evidence, jurors are not going to have trouble convicting Manafort.”

Manafort has pleaded not guilty to all charges.

A network of offshore accounts

Manafort is a longtime lobbyist and political consultant in Washington. Before Trump, he had worked for and advised the campaigns of many Republicans, including Presidents Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush, and former Senate leader Bob Dole. His overseas clients have included controversial world leaders, including Viktor Yanukovych, the pro-Russian former president of Ukraine; Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos; and Zaire leader Mobutu Sese Seko.

The Alexandria trial will focus on events during and after Manafort’s representation of Mr. Yanukovych. From 2006 to 2015, Manafort is alleged to have funneled more than $30 million through a network of offshore accounts in Cyprus and the Grenadines to accounts and vendors in the US.

Many of the transfers were structured as “loans” to avoid US income taxes, according to the 18-count indictment. In other instances, the funds were transferred directly to US-based merchants to pay for bespoke suits from Alan Couture, the Bijan watch, Range Rovers and Mercedes Benz automobiles, and multimillion dollar homes, the indictment says.

Wire transfers were also used to fund renovations and landscaping at Manafort’s homes, including a 10-bedroom, six-bath estate in the Hamptons on Long Island. The property features a pool, a pool house, tennis court, putting green, and a moat, according to federal documents and real estate records.

Manafort had an $18,500 karaoke machine installed in his Hamptons house. He paid the bill by wiring the money from a Cyprus account, according to court documents.

Later, after his political consulting contract in Ukraine ended, Manafort’s income fell, prosecutors say. To make up the difference, he allegedly applied for loans from American banks.

From 2015 to January 2017, Manafort used his US properties as collateral to borrow more than $20 million. Prosecutors say he inflated his income and understated his debts to qualify for the loans.

It was during this same period, in the spring and summer of 2016, that Manafort joined the Trump presidential campaign, serving as campaign chairman and later as campaign manager. He left the campaign in August, after media reports about suspicious payments he’d allegedly received while working on behalf of Yanukovych.

A backchannel for collusion?

Manafort will become the first target of Mueller’s investigation to stand trial. So far 32 individuals, including 26 Russians, have been indicted or charged in the Trump-Russia investigation. Five of them have pleaded guilty.

While jurors in the three-week trial will be shown substantial evidence of Manafort’s taste for expensive items, prosecutors told US District Judge T. S. Ellis in a hearing last week that they will not seek to admit evidence or make any argument at this trial concerning Russian collusion.

Instead, the case against Manafort looks to be a straight-forward prosecution on tax and bank fraud charges.

Tax evasion and financial fraud can be an intriguing news story when the alleged perpetrator is connected to powerful politicians. But that’s not why Manafort’s trial this week is attracting substantial media attention.

Many legal and political analysts have speculated that Manafort – with his long history of working closely with pro-Russian leaders in Ukraine and directly with Russian oligarchs who are close to Russian President Putin – would have been well-positioned as Trump’s campaign chairman to provide a reliable and secret backchannel for possible Trump-Russia collusion during the election.

Manafort was present with Donald Trump Jr. and others at a June 2016 meeting at Trump Tower that had been billed as an opportunity for the Trump campaign to receive “dirt” on Mrs. Clinton from the Russian government. (It does not appear that any “dirt” was produced at the meeting.)

In addition, Manafort was identified by name in former British intelligence officer Christopher Steele’s controversial “dossier” in mid-2016. Mr. Steele was hired by the Clinton campaign and the Democratic National Committee to assemble a political opposition research report to discredit then-candidate Donald Trump. Allegations contained in the Steele dossier helped give momentum to what became the special counsel’s Trump-Russia investigation.

The dossier quotes an unnamed “ethnic Russian,” who was said to be a close associate of Trump, as saying that there was a “well-developed conspiracy of co-operation between [the Trump camp] and the Russian leadership.”

The dossier adds: “This was managed on the TRUMP side by the Republican candidate’s campaign manager, Paul Manafort, who was using foreign policy advisor, Carter Page, and others as intermediaries.”

The Justice Department and FBI appear to have taken these allegations seriously. An August 2017 Justice Department memorandum identifies the anticipated scope of the Mueller investigation as it relates to Manafort.

It says the special counsel was authorized to investigate “allegations that Paul Manafort committed a crime or crimes by colluding with Russian government officials with respect to the Russian government’s efforts to interfere with the 2016 election for President of the United States.”

The status of that portion of Mueller’s investigation remains unclear, despite substantial speculation during the past year and a half about Trump campaign collusion with Russia.

Congressional Republicans have questioned the FBI’s heavy reliance on what they say are unverified allegations in the Steele dossier. Those questions have gained new urgency after the recent public release of redacted copies of top-secret surveillance applications to monitor the activities and communications of Mr. Page, who served as a foreign policy adviser to the Trump campaign.

Four such applications were approved in October 2016, and January, April, and June 2017. All four share the same notation: “The FBI believes that the Russian Government’s efforts to influence the 2016 US Presidential election were being coordinated with Page and perhaps other individuals associated with [Trump’s] campaign.”

Page has denied working as a Russian agent. No charges have been filed against him.

'Part of a larger plan'

Aside from Russian collusion, the Justice Department’s August memo identifies a second area of investigation: whether Manafort “committed a crime or crimes arising out of payments he received from the Ukrainian government before and during the tenure of President Viktor Yanukovych.”

The Alexandria trial falls within this second area of investigation. But that doesn’t necessarily mean prosecutors have given up on trying to identify and prove collusion.

Many legal experts, including Judge Ellis, have suggested that Mr. Mueller’s tax and bank fraud indictment of Manafort is ultimately aimed at pressuring him to cooperate with prosecutors to help prove a broader collusion case involving Russians and perhaps even Mr. Trump.

“Even a blind person can see that the true target of the Special Counsel’s investigation is President Trump, not [Manafort], and that [Manafort’s] prosecution is part of a larger plan,” Ellis wrote in a footnote in a pre-trial decision issued in late June. “The charges against [Manafort] are intended to induce [Manafort] to cooperate with the Special Counsel by providing evidence against the President or other members of the campaign.”

The judge added: “Although these kinds of high-pressure prosecutorial tactics are neither uncommon nor illegal, they are distasteful.”

If convicted of the tax evasion and bank fraud charges, Manafort, who is in his late 60s, could spend the remaining years of his life in prison.

In addition to the 18-count indictment in Alexandria, Manafort is facing trial in September on a seven-count indictment returned by a federal grand jury in Washington, D.C. That indictment charges Manafort with conspiring against the United States by operating as an unregistered lobbyist on behalf of Yanukovych and various political parties in Ukraine. He is also charged with concealing overseas accounts, and attempting to obstruct justice.

Manafort’s former business partner, Richard Gates, agreed in February to plead guilty to charges related to the same Ukraine work and is now cooperating with prosecutors against his former boss. Mr. Gates will likely become the star witness against Manafort.

Hoping for a pardon?

Given the apparent strength of evidence against Manafort, Gates’ cooperation, and the prospect of spending his final years behind bars, many analysts say they are surprised that Manafort hasn’t reached his own plea deal with Mueller.

“There is reason to think that Mueller’s office would be open to a deal. Mueller has made deals with many of the other people he’s charged,” says David Sklansky, a professor at Stanford Law School and co-director of the Stanford Criminal Justice Center.

He adds: “It is possible there have been discussions and negotiations, but the two sides just haven’t been able to come to a meeting of the minds.”

Rosenzweig, the former federal prosecutor, says the lack of a plea deal may be stem from something more basic. Manafort may not have much, if anything, to offer prosecutors to justify a substantial sentence reduction as part of a plea deal.

“I and others would have expected Mr. Manafort to reach an agreement already,” he says. “If he is going to turn state’s evidence, so to speak, the time to do it is now before you take up three weeks of trial time and before you put the government to its proof.”

Experts say there is another possible explanation, however, behind Manafort’s apparent refusal to cooperate – that he may be hoping for a presidential pardon.

“This president has sent the kind of signals that someone like Manafort might interpret to mean, ‘If you stick with me, I’ll stick with you,’ ” Professor Sklansky says. He adds: “The very idea that someone like Manafort could think of relying on a pardon to get him out of the kind of money laundering charges he is facing is really troubling.”

Yet relying on a pardon seems like a long shot – and may hinge on what, if anything, Manafort actually knows.

“If Manafort knows nothing and Trump is convinced that Manafort knows nothing, then the only reason to pardon him is pure Christian charity – and whatever else you might say about Mr. Trump, that doesn’t describe him to me,” Rosenzweig says.

Trump has expressed regret about the ongoing investigation of Manafort. He frequently denounces the special counsel’s Trump-Russia collusion investigation as a “phony witch hunt.”

Recently, during an interview with Fox News’ Sean Hannity, Trump raised eyebrows by comparing Manafort’s case with the tax evasion conviction in 1931 of Chicago mobster Al Capone. “With Paul Manafort, who is clearly a nice man, look at what is going on with him,” Trump said, criticizing the Mueller probe. “It’s like Al Capone.”

In the case of Capone, of course, prosecutors could never assemble enough evidence to charge the mob boss with murder, running prostitution rings, or bootlegging. So, instead, they charged him with tax evasion.

The president appeared to be suggesting that Capone was defeated by a legal technicality – and that Mueller’s team was seeking to ensnare Manafort under similar circumstances.

But analysts note that allegedly laundering $30 million to avoid paying taxes is far from a legal technicality.

And the president seems to have overlooked a critical point. Capone went to prison and served eight years of an 11-year sentence, much of it in Alcatraz.

Share this article

Link copied.

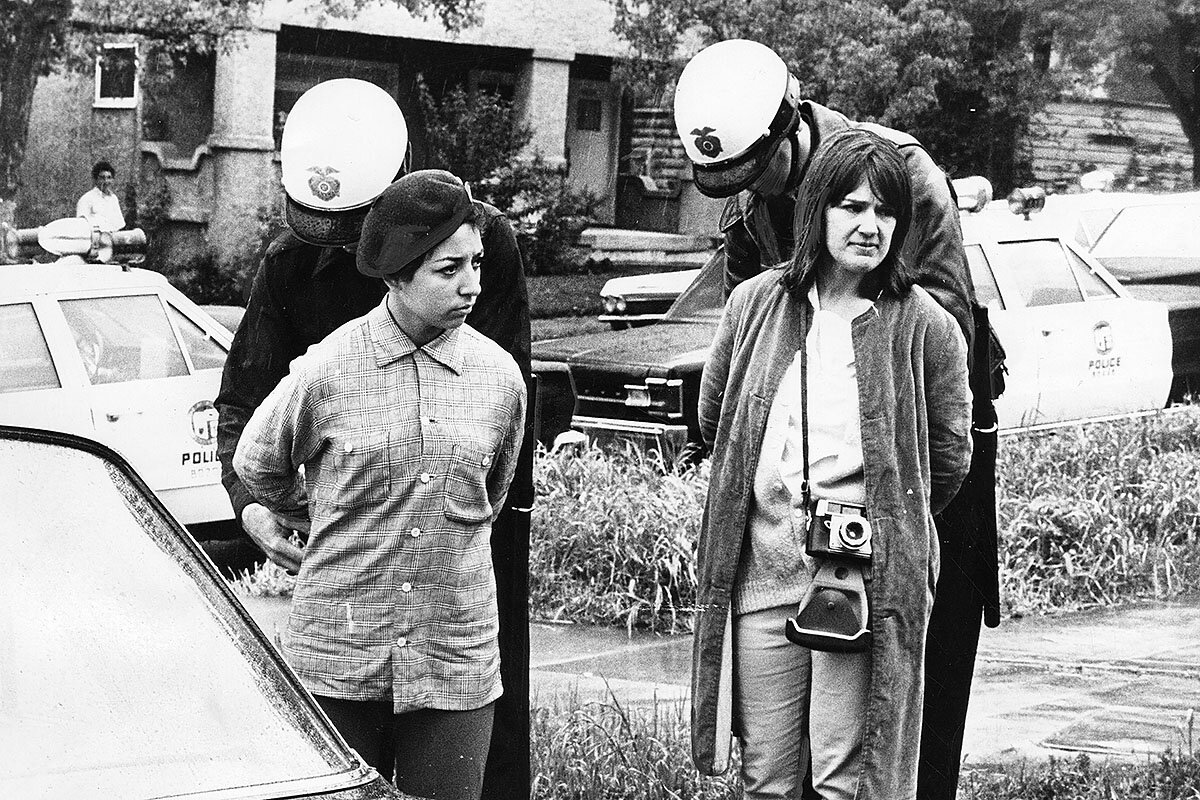

From tear gas to tweets: 50 years in the evolution of US activism

In a time of protests and marches, the turbulent summer of 1968 echoes loudly today. So we went looking for what is different now. In many ways, the issues are the same. But as activism evolves, it is looking to rediscover what makes change.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

In 1968, American activism surged, shaping culture, race relations, gender norms, and politics for decades. Fifty years later, activism has transformed. There’s less rioting, more tweeting. Anger flares faster, but it burns out quicker. In 2018 the dream is not just recognition, it’s also representation: Today’s activists also use the ballot box to address inequality from positions of power, and they have technology to magnify their impact on political discourse. “We’re changing the conversation,” says Cara McClure, who has gone from homeless single mother to entrepreneur to now would-be politician, running for state office in Alabama. But today's progressive movements still coalesce around race, gender, and inequality. In 1968, as now, the goal was to raise awareness about the struggles of the marginalized. And there’s still a real sense that the system needs a shake-up. “What drove those [late-’60s] movements was a rather wild hope that it was time for the country to repair what had been broken in American history,” says sociologist Todd Gitlin. “People today are operating in that same spirit.” Ms. McClure speaks for many when she says: “I'm so fired up.”

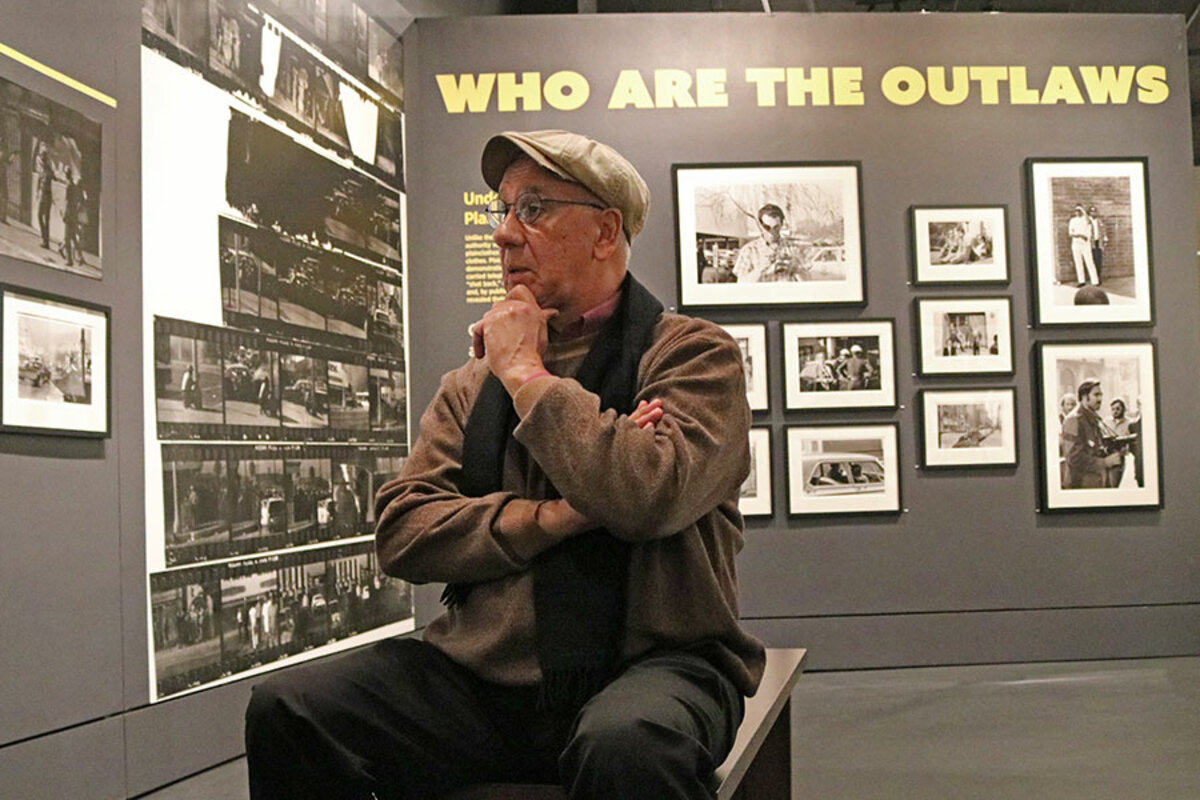

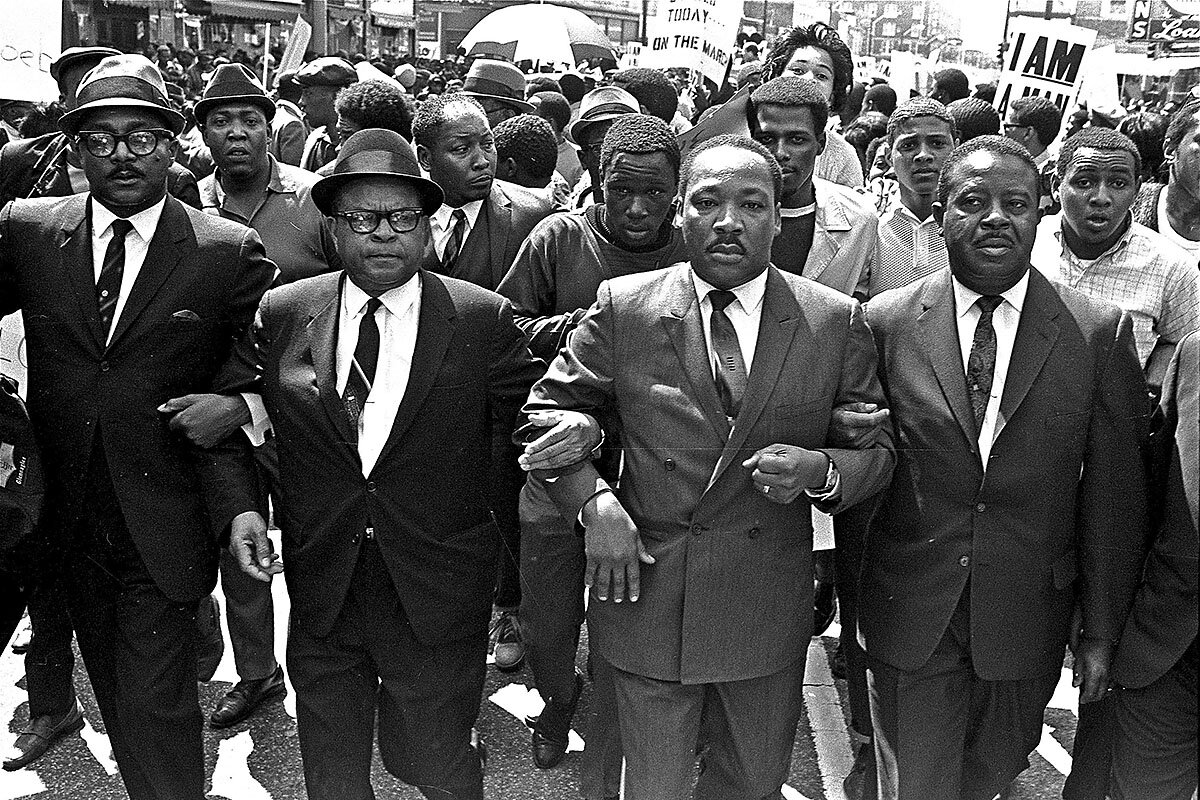

From tear gas to tweets: 50 years in the evolution of US activism

The day was dying. We watched it go, the sun streaking the sky pink and orange as it sank behind the red clay mountains that rule the Arizona landscape.

We had just hiked to the top of Mares Bluff here in Clifton, a mining town of 4,500 near the New Mexico border. The steep, rocky path is marked by gold plaques commemorating every conflict involving the United States since World War I. On the cliff’s edge, flags representing each of the branches of the armed forces stand billowing over the town’s buildings and bungalows. The Stars and Stripes towers above them all.

The memorial had been built in 1999 by a group of local veterans, most of whom had served in Vietnam at the height of antiwar fervor. The place is a physical display of advocacy – a silent salute to fellow soldiers by service members who for decades had felt scorned by the country for which they had fought.

This was our third stop on a cross-country drive from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C. Our quest was to find out how activism has evolved in the past 50 years. Standing on that bluff saluting eras gone by, we could easily feel connected to our trailhead: 1968, an iconic year in US history, one rocked by war and assassinations, by race riots and tear gas, by music, marches, and movements.

Activism had taken center stage that year, shaping American culture, race relations, gender norms, and politics for half a century. We wanted to understand what the period meant to the generation who’d lived during it – and how we, their political and cultural descendants, continue to wrestle with the fallout in 2018.

The trip took 13 days and spanned more than 3,200 miles. Hours of interviews with former and current activists showed us that while the blueprints for battle have changed, the issues many people are fighting for have not. In 1968, the goal was to raise public awareness about the struggle of marginalized communities. Activists then used music, art, and writing as well as protests to bring that struggle forward. In 2018, the dream is not just recognition but representation. Activists today are using the ballot box in a bid to address inequality from positions of power. They also have technology to magnify their impact online, in the streets, and in political discourse.

But today’s progressive movements are still coalescing around race, gender, and inequity – the same issues that undergirded movements 50 years ago. Now, as then, there’s a sense that the system desperately needs a shake-up.

“What drove those movements was a rather wild hope that it was time for the country to repair what had been broken in American history,” says sociologist Todd Gitlin, author of “The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage.” “It’s the kind of hope that generates commitment ... built on a moral fiber that comes to people as they look out on the world and say: ‘This is the moment we’re going to try something.’ ”

“People today are operating in that same spirit,” he says.

***

We started our trip with a visit to the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles. The museum was staging an exhibition on La Raza, a bilingual magazine published by Chicano, or Mexican-American, activists from 1967 to 1977. The paper had covered the major demonstrations of the Chicano movement, including the East L.A. rallies in the spring of ’68, when thousands of high school students marched to protest poor conditions in predominantly Mexican-American schools. (Three months later, Los Angeles would reel from the assassination of then-presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, who was in California to meet with farmworker advocate Cesar Chavez.)

Luis Garza had been a photographer for La Raza and co-curated the exhibition. As he walked us through the images on display, he told us how the paper’s staff had strived to capture not just protests and riots but also life in “the barrios” of East L.A. “It was about family, it was about children, it was about culture and art,” he says. “It was about representation ... and making an argument for inclusion.”

We noted that minus the beehive hair and muscle cars, La Raza’s photos could have been lifted from the Women’s Marches that followed President Trump’s inauguration in 2017, or the student-led March for Our Lives against gun violence earlier this year. “Nothing has changed,” Mr. Garza agrees, peering at us behind big, round glasses. “That’s the tragedy of it.” Young people today are contending with the same issues. “That’s why this exhibition resonates,” he says.

As we made our way across the country, we would hear echoes of that idea from people who’d lived through the upheavals of the ’60s and those who’ve inherited the outcomes. The era saw major progressive victories: the expansion of voter rights, the abolition of the draft, the beginning of the end of segregation. Yet “none of those issues have really stopped being issues,” says Professor Gitlin, who teaches at the Columbia University School of Journalism in New York City. “The Vietnam War came to an end, but America’s role in the world, and how to conduct race relations, and how to conduct relations between the sexes – those are all in play.”

After our tour with Garza, we struck southeast for Clifton, about 580 miles away. We arrived on a scorching Saturday and took refuge in Steve Guzzo’s blessedly cool kitchen, where he met us with his friend Bob Jackson. Both men had served in Vietnam – Mr. Guzzo from 1966 to 1968 and Mr. Jackson from 1969 to 1970. Guzzo is president of the veteran support group that built the memorial atop the bluff. Jackson helps him manage the site.

Like many Vietnam vets, Guzzo and Jackson are skeptical of activism and its ability to produce positive change. Both men had returned from the service to a country that had turned against the war, and against them. Guzzo recalled the day he landed in Oakland, Calif., in the spring of 1968.

“I come off the plane, and there’s all these protesters protesting the war,” Guzzo says. “This guy spits on me. And he called me a baby killer, drug addict, warmonger.”

That hostility, directed at them first by activists and then the public in general, has made them both wary of marches and movements – even as they applaud their generation’s efforts to make the country a better place. “The ’60s was one of the greatest generations of all time,” Guzzo says as he served up chips and homemade salsa. “All kinds of rights came out of there. We’re talking women’s liberation, gay rights, human rights. It was an explosion.”

But, like Garza, the two veterans are not sure America has improved in the years since. “It peaked, and then it went the other way,” Guzzo says.

***

We left Clifton on a series of state highways that took us north through New Mexico’s Gila National Forest up into Albuquerque. From there it was due east on Interstate 40, through empty stretches of northern Texas and the plains of Oklahoma. Then, suddenly, the land turned lush: Rivers began to widen and trees filled the roadsides. By the time we crossed the Mississippi River into Memphis, Tenn., the desert was a distant memory.

It was in Memphis that we got perhaps our clearest sense of the ties binding activism today and 50 years ago, and what has and hasn’t changed since. On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in downtown Memphis. For a young Al Bell, King’s death was a personal blow. Mr. Bell had marched with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Savannah, Ga., as crowds of angry whites spat at and beat them. He’d debated the merits of passive resistance and economic empowerment with the reverend himself, and had even co-written a song for King called “Send Peace and Harmony Home.”

King was trying “to instill in us hope, pride, and belief in a better day, as opposed to hopelessness,” Bell says. “That was very, very important to me.”

The assassination had also come at a time when Bell already had his hands full: He had just taken over as chief executive of Stax Records, a soul music label headquartered on East McLemore Street, just a couple of miles from the Lorraine. Four months earlier, the company’s biggest star, Otis Redding, had died in a plane crash. Stax had also just lost its entire music catalog after a deal with its longtime distributor, Atlantic Records, fell through.

Stax’s survival was important to Bell, not just because he was running the company but because of what it stood for. Stax had maintained a policy of racial integration at a time when Memphis was still deeply segregated. Bell still remembers the first time he walked into a studio and saw black and white musicians writing and recording together. “I’d never seen anything like that before,” he says. “I couldn’t believe that that sound and that feeling and that spirit were coming out of these two black guys and these two white guys. I thought, ‘This is a miracle!’ ”

In 1968, Bell set out to simultaneously release 30 singles and 28 albums in a project he called “Soul Explosion.” The goal was to prove that Stax could still make hit records – and that its black artists, especially, could sell music to mainstream, or white, audiences. The label was also a way to represent “the lives, lifestyles, and living of African-Americans” through music, he says. “That was our activism.”

Today, on the site where Stax once stood, a museum celebrates the label’s legacy. Next door is the Stax Music Academy, which offers after-school and summer programming for at-risk, inner-city youth. The day we arrived, we caught the academy’s summer alumni band warming up. The group plucked songs from the Stax catalog, urging visitors to sing and dance to classics such as “I’ll Take You There” by The Staple Singers.

Later, the academy’s instrumental music director, Paul McKinney, told us that connecting the students with the label’s history is a key part of the program. Their hope is to provide young Memphians with the same kind of opportunity Stax Records did for black artists more than a half-century ago.

“I want them to be armed and educated ... to go out to say, ‘Guess what? I’m good enough. I can do it. I don’t need anybody to give me handouts,’ ” Mr. McKinney says.

“The students are still facing a lot of similar issues, you know, that those Stax artists from the ’50s and ’60s had to deal with.”

***

The movements of the 1960s did move the needle. Laws such as the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act provided real protections that have helped historically marginalized groups begin to find equal footing in American society. In 2018 many people know and accept that they need to speak out and stand against various kinds of discrimination. That was not necessarily true in 1968.

But neither the best-intentioned laws nor the changing tide of public opinion can erase centuries of oppression and disenfranchisement, says Lorena Oropeza, an associate professor of history at the University of California, Davis. Just because a society has decided something is wrong doesn’t mean it’s solved the problem.

“Things have become more complicated,” Professor Oropeza says. “It’s no longer, you’re a black child and you can’t go to a white school. It is the case that you’re a black child or a poor child and you’re in a bad school. It’s much more structural, and that’s harder.”

As the challenges facing activists evolved, so did the technology that helps them organize. Social media now makes it possible to rapidly coordinate massive demonstrations across cities – as it did during the Women’s Marches, the March for Our Lives, and the recent Families Belong Together rallies against the separation of children from their parents at the US-Mexican border. Instant communication allows organizations to flourish without the need for a unifying leader. Smartphones give anyone the power to capture injustice when they see it and upload it to a public forum.

“What took us days, weeks, months, years is now instantaneous,” Garza says. “You have here what makes the difference, the very thing they cannot suppress.” He raises his cellphone. “This is your voice.”

The downside, of course, is that the problems of the internet age apply to activism, too. Misinformation can spread quickly and be difficult to correct, leading to misplaced outrage and sometimes violence. The daily rush of headlines can overwhelm people, creating apathy. And while Twitter can get people donating to a cause or out on the streets, it doesn’t push them to do the grunt work on which real change is founded.

“I see the gathering, and the intention, and the passion people have,” says Gloria Arellanes, a former member of the Brown Berets, a paramilitary group that campaigned for Chicano rights in Los Angeles in the 1960s and ’70s. Ms. Arellanes, who’d joined the Berets at age 19, had spent most of her time with the group running a free clinic that served poor Mexican families in East L.A. She still believes that that was the most important part of her activism.

“[People] will say, ‘I came out, I did what I had to do. Tomorrow I go back to my life,’ ” she says, shaking her head as she sits on her porch in El Monte, Calif. “No. You don’t just march and that makes change. That’s not what makes change.”

***

Still, some of the most successful movements today wouldn’t be where they are without modern technology.

In February, teachers across West Virginia mounted a series of strikes over pay and working conditions in public schools. The state teachers unions, with the support of local school districts and administrators, canceled classes for nine days while educators rallied at the State Capitol in Charleston. In the end, the teachers won all five of their demands – and reclaimed a sense of pride and empowerment after years of being overlooked. Teachers in Arizona and Oklahoma would later follow their lead.

We met Adena Barnette – president of the Jackson County Education Association and one of the most visible figures during the strikes – in an empty classroom at Ripley High School, about 35 miles north of Charleston. With her were music teacher Annie Hancock and English teacher Emily Oakes, both of whom had gone out on strike.

With rain misting the windows, the women told us how crucial technology had been to their effort. All 55 West Virginia counties had closed schools to join the strikes, which wouldn’t have been possible without cellphones or the internet. “I could reach 400 people with this phone instantly,” Ms. Barnette says, waving the device. “We had a text tree set up so I could send a text and it went out to the whole county.”

Facebook and Twitter also kept people connected to the cause. Teachers and their supporters were able to track hearings and recruit new people, even when they were a hundred miles away.

Another shift in activism between 1968 and today is the way groups are trying to induce change. Now they’re as likely to do it at the ballot box as with a placard.

Following the 2016 elections a wave of women and minorities began running for office, many for the first time. The sudden rush toward positions of leadership, especially among women, marks an evolution from ’60s-era feminist strategies of marching in the streets, lobbying for reforms, or tossing bras into the trash.

The idea is that the most relevant way to boost a cause is to do it from within government. “If the current system and the men in charge were going to do things for women and children, they would’ve done it by now,” says Stacie Propst, who in 2017 founded the Alabama arm of Emerge, a national nonprofit that recruits and trains women to run for state and local office under the Democratic banner.

We met Ms. Propst and three other Emerge women, all of whom are on ballots this fall, at Propst’s home in Irondale, just outside Birmingham. “We haven’t done ads,” she says, after installing us at her big, oval dining table. “It’s been networking woman-to-woman, and social media is often the way that women do it.”

Cara McClure, who’s running for a seat on the Alabama Public Service Commission, not only discovered Emerge on Facebook, she also raised the funds for her filing fee – more than $1,900 – through GoFundMe.

Ms. McClure posts regularly on her Facebook page as a way to both campaign and share her experiences with friends and followers. “I write my fears, insecurities,” she says in a soft lilt that belies her tough history. A marketer by training, McClure had lived on the streets, raising her son, before deciding to become an activist and now politician.

She sees social media as an important way of changing the narrative, regardless of her campaign’s outcome. “I’m very mindful that people are watching, and young women are watching,” she says. “So every step of the way I’m thinking about what I’m doing represents.”

***

In many ways, activism in 2018 looks nothing like activism in 1968. We no longer burn draft cards or spit on returning vets. There’s less rioting, more tweeting. Anger flares faster, but it also burns out quicker. Still, as we wound our way east, we sensed an energy in the air, one that called to mind the “wild hope” that Gitlin, the author, had spoken of.

Across the country, we saw people waking up to causes – conservative and liberal – they can support and finding a way to fight for them, just as activists did in 1968. Back then it might have meant wearing a brown beret or a black jacket, taking photos for a magazine, or writing a song with a person whose skin was a different color. Today it would look more like donning a pink hat or waving a rainbow flag or running for office when everyone says you can’t or shouldn’t.

“I’ve become more aware at all levels. I never really felt like I was organizing to make change until this event,” says Ms. Oakes, the English teacher in West Virginia. “We have a platform to build on that I don’t think we had a year ago. And it’s been inspiring to see how we’ve started something.”

“We’re changing the conversation,” adds McClure in Irondale. “I’m just so fired up. Going from homeless single mom to entrepreneur to activist to now politician? The proper, the right type of politician with visionary leadership? Oh my God, chill bumps.”

“I think too many of us were way too complacent because we were comfortable and we felt as if it didn’t matter,” says Heather Milam, who’s running for secretary of State in Alabama. “If we’ve learned anything from history,” she adds, “it’s that we can’t rest on our laurels.”

Back in Clifton, Guzzo and Jackson, neither of whom would consider themselves politically progressive or liberal, have found their own brand of activism. Guzzo regularly maintains the memorial on Mares Bluff, keeping the plaques free of graffiti and the trail clear of debris. Jackson prints dog tags for service members to display on the memorial. The tags hang on wire strung across the flagpoles lining the cliff’s edge. Together the two men helped build another, smaller, memorial park in town for people who can’t make the hike up to the bluff.

Guzzo says helping others – and dedicating himself to a cause he cares about – has been the most effective form of healing he’s found since the war.

“The best therapy for me, and the best therapy I’ve seen for a lot of people, is getting involved,” he says. “The more active you can become, the more self-worth you have.”

Dylan Lewis contributed to this cross-country report, both from behind the wheel and with his notebook.

On election day, ‘new Zimbabwe’ looks closer – but still far away

When the Monitor first met these families, Robert Mugabe had just resigned – the same day, in fact, that their daughters were born. Eight months later, amid elections, we wanted to know if they saw signs of the new Zimbabwe they dreamed of for their children.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Progress and Alfred Garakara’s daughter, Aleeya, was born Nov. 21, 2017. It’s a day they’ll always remember, of course, but so will all Zimbabweans: the day strongman Robert Mugabe finally resigned, after 37 years in power. “She is living in a new Zimbabwe, to me,” Alfred says. In Aleeya’s Zimbabwe, people gossip freely about their president in shops and on public minibuses. They don’t go to political rallies when they don’t feel like it (unlike before, when young men in ruling party T-shirts made certain they would be there). But today, as Zimbabweans vote in the first post-Mugabe election, many say that the new Zimbabwe they felt promised last year has been slow to come. Mr. Mugabe’s successor, President Emmerson Mnangagwa, vowed to jump-start the country’s economy, which was leveled by years of sanctions and corruptions. But today, there is another currency shortage, with practically no cash to speak of. “It’s not enough to have freedom of expression on an empty belly,” Alfred says. “My daughter can’t take freedom of expression to school in her lunchbox.”

On election day, ‘new Zimbabwe’ looks closer – but still far away

It’s strange now to think of that day, the one where Moreblessing Mutsakani’s life cleaved in half. The day that broke the world in two.

But that’s how it will always be: before Nov. 21, 2017, and after.

Before was Robert Gabriel Mugabe’s Zimbabwe. Mr. Mugabe was Zimbabwe, and Zimbabwe was Mugabe. You just didn’t have one without the other. After a while, it had become almost impossible to imagine you ever could.

Until that day, when he was just gone, and the country’s strange new after could finally begin.

But for Ms. Mutsakani, that day represented another before, and another after. Before Nov. 21, 2017, there was also no Meryl, her baby girl. But since that day, she’s rarely apart from this giggling, roly-poly of a child, who grasps at everything, as if she’s hungry to know what every bit of the world feels like. There was life before Meryl – but somehow, her mother thinks when she holds her, that almost doesn’t feel possible.

The Monitor first met Mutsakani and her family in November last year, a week after Meryl was born, seemingly on the cusp of history.

“Welcome to all the Zimbabwean children born on this day,” Zimbabwean novelist NoViolet Bulawayo had written on Facebook, hours after Mugabe resigned. “You’re our most precious, most untarnished promise, may you never see what we've seen, may you know, finally, a Great Zimbabwe.”

Today, eight months later, their country is at the polls, electing the first politicians of the post-Mugabe era. But in a two room tin-roofed house at the end of a rutted dirt road in the Harare suburb of Epworth, Mutsakani and her husband, Joseph, say they are still waiting for Meryl’s new Zimbabwe to appear.

They wait for it in many places, but none so obviously as the bank queue. Over the last two years, Zimbabwe has been gripped by a currency shortage so dire that there is no almost no cash to speak of here. Out-of-order ATMs dot the capital city like relics, a reminder of a long-gone time when machines could spit out your money at will. Now, instead, once or twice a month, Joseph braces himself against the dry pre-dawn winter chill to arrive at the bank by 4 a.m. so that he can withdraw $30 US in government-printed “bond notes” – the maximum many banks now allow.

When he arrives, he is often number 600 or 700 in the line. And when his turn at the teller comes 10 hours later, he’s often handed his allotted money in a bag of 10-cent coins. Sorry, the bank employees tell him if he balks at this, it’s all we have now.

This wasn’t supposed to be what Meryl’s Zimbabwe looked like, her father says. When Mugabe’s former deputy Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa – popularly called by his initials, “E.D.” – became president, he had promised to woo back foreign investors and create new jobs to jump-start an economy leveled by years of sanctions and corruption. “Zimbabwe is open for business,” he announced again and again. “A man of action,” promised the giant campaign billboards that sprung up as the July 30 elections approached.

So why, Joseph wondered, did it sometimes feel like things were still going backward?

Meanwhile, in another part of town, Progress and Alfred Garakara were taking stock too.

Their daughter Aleeya was born the same day as Meryl, in a tidy government maternity hospital in the neighborhood of Mbare, a dense jumble of houses, shacks, and rundown apartment blocks on the southern edge of the capital.

“She is living in a new Zimbabwe, to me,” Alfred says. In Aleeya’s Zimbabwe, he says, people gossip freely about their president in shops and on public mini-buses. They don’t go to political rallies when they don’t feel like it (unlike before, when young men in ruling party T-shirts came by their house to make certain they would be there).

“In the 2008 election, the violence got so bad that we wouldn’t open up the door at night, even to family,” Progress says. “This way we are talking critically of the president, we never ever would have done that now.”

“But it’s not enough to have freedom of expression on an empty belly,” Alfred adds. “My daughter can’t take freedom of expression to school in her lunch box.”

Around them, these past few months, has echoed a quintessentially patient Zimbabwean mantra. Let’s wait and see. Will the new government create new jobs? Let’s wait and see. Will Mr. Mnangagwa step down if he loses the election? Let’s wait and see.

But even as they were waiting, life carried on. Aleeya grew a round belly and gleeful laugh, and four razor-sharp front teeth, which she mostly used to eviscerate gummy bears. Progress started selling odds and ends – clothespins, sewing kits, reading glasses – on the floor of Harare’s tobacco auction warehouses. A new Pepsi factory opened nearby, and so many people stormed the gates trying to apply for jobs that police broke up the crowd with tear gas. The price of cooking oil and maize meal and formula went up, and then it went up again.

“At times, I wondered to myself, why did we think E.D. would change anything?” Progress says. “At the end of the day, he comes from the same team as Mugabe. It’s the same game.”

And so, as their cash dwindled, Progress took a hard look around the house to see what they could part with. Already, in the last two years, the family had sold their fridge and two sofas. Now, she realized with a sharp pang, her beloved wardrobe set would have to go too. So one day in early December, she and Alfred dragged it out onto the dusty road in front of their house.

Soon, someone came by with an offer. $200. And just like that, it was gone.

“I won’t mince my words – we did this thing to survive,” she says. “I have a responsibility to make sure my family is fed, however I can.”

Behind her, the state broadcaster blasted grainy footage of a presidential campaign rally, which had been on most of the day. The president, who was wearing a tailored yellow shirt with his own face on it, pushed his arms back and forth in a jerky dance.

Occasionally, Progress or Alfred glanced over at the set, but they weren’t really paying attention. Things might be changing, they thought, but politics still didn’t belong them.

“At the end, Mugabe was tired, he was ready to go,” Progress says, watching E.D.’s on-stage shuffle. “But these guys, you can see they are here to stay.”

Tatenda Kanengoni contributed reporting to this story.

In Malaysia, a new attempt to know one’s neighbor – and his faith

Proximity doesn’t always breed familiarity in religiously diverse Malaysia. Many people tolerate one another’s faiths without understanding them. But after an election upset, many Malays have a message: That’s not enough.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

Malaysia is a country of many faiths – as is clear from just a walk through the neighborhoods of Kuala Lumpur. In one yard stands a red wooden Taoist altar box, covered in yellow gilded Mandarin characters. Next door, a stone Buddhist statue is poised on a pedestal in a carefully arranged garden. And nearby, a villa’s welcome sign reads “Ma Shah Allah”: the Islamic equivalent of saying “God bless this house.” But despite centuries of living side by side, many Malaysians say they know little about each other’s religions. In part, analysts say, that’s the result of recent years’ increasingly identity-based politics, meant to distract from the last government’s mounting scandals. “We keep employing the term ‘tolerance,’ but we are unable to go beyond it,” says Victoria Cheng, whose nongovernmental organization promotes interreligious understanding. “By saying tolerance, we send the message: I tolerate your presence enough not to attack you but I do not like you enough to understand you. And that has to change.” After an upset election in May, however, some Malays hope the time is right to promote interfaith events – starting with something as simple as breaking bread together.

In Malaysia, a new attempt to know one’s neighbor – and his faith

Jason Lee holds three smoldering incense sticks at his forehead and bows three times at the altar in the open courtyard. He then pauses in prayer. As he places a candle on a mantle in front of the altar, the Muslim call for noon prayer, the adhan, rings out overhead.

Mr. Lee is a Buddhist, his neighbor is a Hindu, his cousin is a Taoist, his best friend is a Christian. They are all Malaysians living in a country whose official religion is Islam.

“We are many faiths but one country,” Lee says while leaving the Maha Vihara Buddhist temple, which has stood in Kuala Lumpur since 1894.

Yet while Malaysia's mix of faiths and cultures have lived side-by-side for centuries, increasingly ethno-sectarian politics have built barriers between communities over the past two decades.

Many Malaysians say they tolerate each other, but do not understand each other – not yet, anyway.

Since the May election, when voters ousted the party that had ruled Malaysia since independence from Britain, some are now looking to transform the country into a better model of interfaith harmony. And the first step, they say, is to know one another.

“It is part of Malaysian society and culture to be tolerant. We keep employing the term ‘tolerance,’ but we are unable to go beyond it,” says Victoria Cheng, lead program manager at Projek Dialog, a nonprofit that promotes interreligious understanding.

“By saying tolerance, we send the message: I tolerate your presence enough not to attack you but I do not like you enough to understand you. And that has to change.”

Diverse but divided

Religions came in waves to Malaysia. Islam was brought by merchants between the 10th and 12th centuries; Buddhism and Taoism came over with Chinese immigrants; Hinduism and Sikhism arrived with Indian immigrants; and Christianity first appeared with Arab Christian traders, then flourished with the conquests of the Portuguese, Dutch, and British.

This legacy has given Malaysia an unusual mix of faiths: 61 percent Muslim, 20 percent Buddhist, 9 percent Christian, and 6 percent Hindu, in addition to smaller numbers of followers of Sikhism, Taoism, indigenous beliefs, and other religions. Although Islam is the official religion, other faith communities are free to practice and organize themselves.

Yet the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), the party which had dominated Malaysia since the late 1950s, frequently turned to identity-based politics to frighten and mobilize its Muslim Malay base – particularly as political scandals mounted.

Analysts say former prime minister Najib Razak wooed more hardline Islamist voters as the 1MDB graft scandal engulfed his administration. Mr. Najib was arrested and charged with corruption related to 1MDB earlier this month. He has denied all wrongdoing.

“The use of ethno-politics and Islamism was not common, but UMNO increasingly resorted to it recent years to get their base mobilized, get the Muslim Malay vote and distract the public from corruption,” says HuiHui Ooi, a Malaysia analyst and associate director of the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security at the Atlantic Council.

The government’s Department of Islamic Development (JAKIM) and its local offices would restrict interfaith initiatives involving Muslims, advocates say. They describe an increasingly intolerant atmosphere, from public condemnation of “un-Islamic” events, to restrictions on non-Muslims using the word “Allah” to refer to God. The previous government cancelled a Christian prayer gathering during Ramadan, saying it would upset Muslims during the holy month.

Malaysia bans proselytizing to Muslims, and conversion from Islam requires rarely-given approval from a shariah court. To avoid accusations of proselytizing, Buddhist newsletters have “for non-Muslims only” written in a banner across the top, while Buddhist bookstores post signs in the window barring Muslims. Church newsletters are not distributed outside churches.

“There were always attempts from Malaysians of different faiths to reach out, to have true interfaith initiatives, but the authorities would prevent them from happening,” says Kevin De Rozario, a lawyer and activist CAN Malaysia, a Christian organization.

Religion 101

The policies have left a lasting mark. Many Malaysians say they have never stepped into a house of worship other than their own; others struggle to differentiate between the different religions or understand the basics of Islam.

Projek Dialog has hosted a series of forums explaining the basics of Malaysia’s different faiths, delivered by religious experts and activists in Kuala Lumpur and other locations, from “Shariah 101” to “Taoism 101.” Malaysians are invited to ask about stereotypes they have held for years but would otherwise go unanswered and unchallenged, activists say.

Participants have openly asked whether it is true that Sikh men must never cut their hair (Yes), or whether marrying four wives is compulsory in Islam (No, but it's allowed).

“Sometimes we get complaints that Chinese Malaysians are building a second temple in the same neighborhood, and we have to explain this is Buddhist temple and that is a Taoist temple, and they all must have access to their houses of worship and they do not threaten yours,” says Mohd Faridh Hafez, of the outreach bureau at the Muslim Youth Movement of Malaysia (ABIM). “We are working against the disinformation that has been spread over the years.”

Breaking barriers can also be as simple as breaking bread. After UMNO lost the election on the eve of Ramadan, Malaysians looked for ways to capitalize on the Muslim holy month to show solidarity. ABIM worked with a Christian group and Komas, an anti-discrimination NGO, to organize an interfaith iftar – a fast-breaking meal at sunset – at a Kuala Lumpur mosque, featuring Muslim and Catholic leaders.

This time, JAKIM did not shut it down. While a small crowd was expected, hundreds showed up to pass out porridge and water and share the meal. The symbolic act of breaking the fast went viral, symbolizing hope for a new, more inclusive country.

“There is a strong urge among Malaysians to meet and learn about each other; it is only a question about allowing a meeting space,” says Faribel Fernandez, financial officer of Komas.

ABIM, for example, opens its social services to all Malaysians. “We all want to see Malaysia as a model as a Muslim country with a pluralistic society where all live together in harmony and understand each other,” says Ahmad Fahmi, the group’s vice president.

There are signs that average Malaysians are eager as well. At the Batu Caves, a 300-foot staircase up a mountain to a Hindu cave temple outside Kuala Lumpur, ethnic Chinese and Malays in Islamic headscarves make the trek to watch the prayers.

And in Putrajaya, the federal-government district, hundreds of non-Muslim visitors snap selfies and read informational signs outside a palatial rose-granite mosque that floats, seemingly suspended on the water.

In other subdivisions, a common sight is one yard with a red wooden Taoist altar box covered in gilded Mandarin characters, next to one with a stone Buddhist statue on a pedestal in a carefully-arranged garden, adjacent to a villa with the Arabic words “Ma Shah Allah”: the Islamic equivalent of a plaque saying “God bless this house.”

The walls between these neighbors will soon be lowered, some Malaysians hope.

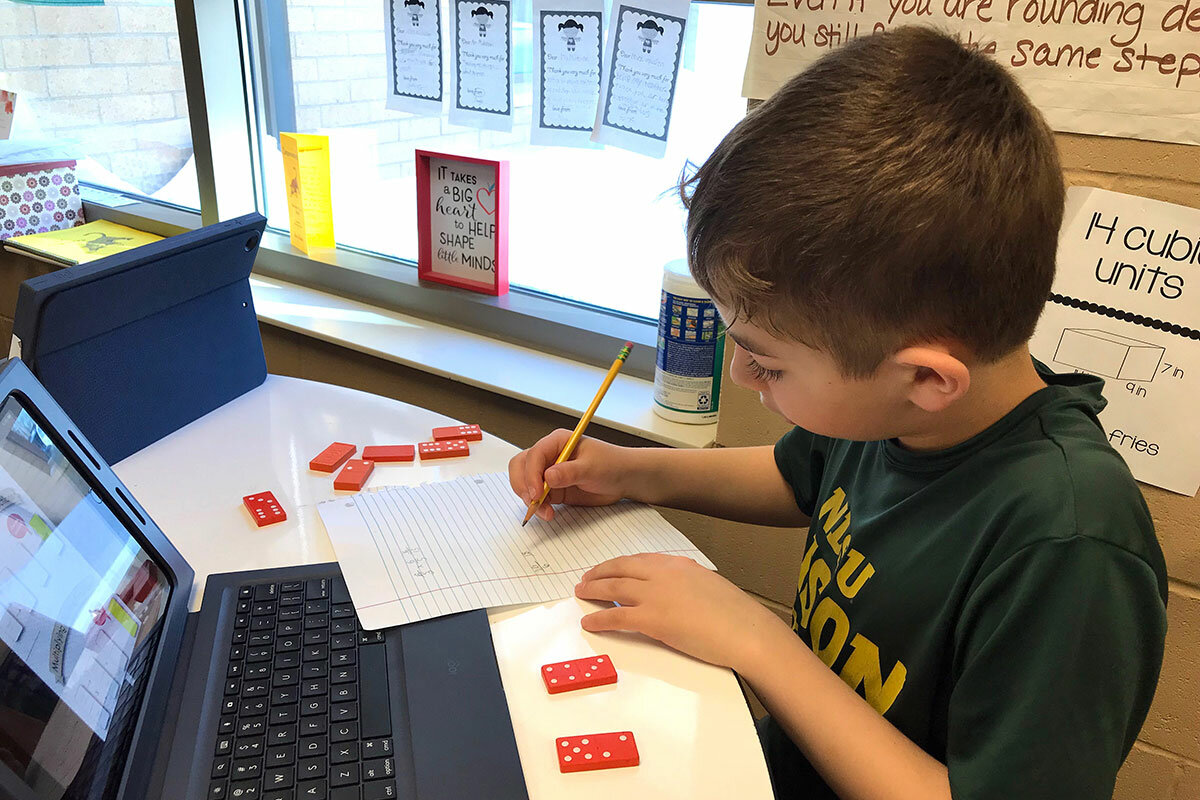

A North Dakota school district tosses old lesson plan, and more

Are grade levels really necessary? One North Dakota school shows how creative educators can get when they are determined to put students’ needs first.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Chris Berdik The Hechinger Report

Moving from one grade to the next is often a rite of passage. But what if there were no grade levels? That’s what Northern Cass School District 97 in Hunter, N.D., is experimenting with. The idea is to untether teaching from traditional approaches – where students are grouped by age and taught at a uniform, semester pace – and instead adopt competency-based education, in which students progress through skills and concepts by demonstrating proficiency. Although it’s still sorting out standardized tests and student self-pacing, Northern Cass took the first steps toward its goal this past school year, launching a pilot called Jaguar Academy. A few dozen teens left their grade levels behind for three periods a day and moved through select courses with a mix of online lessons and teacher-led seminars. The district plans to expand the pilot until it’s an option for all students in what are now called the eighth through twelfth grades. For Katelyn Stavenes, a rising ninth-grader, Jaguar Academy is a welcome taste of autonomy. “I can just lean back and do my stuff,” she says, “instead of always watching the clock and wondering, when can I get out of here?”

A North Dakota school district tosses old lesson plan, and more

On windswept fields outside Fargo, N.D., a bold experiment in education has begun. In a lone building flanked by farmland, Northern Cass School District 97 is heading into year two of a three-year journey to abolish grade levels. By the fall of 2020, all Northern Cass students will plot their own academic courses to high school graduation, while sticking with same-age peers for things like gym class and field trips.

The goal is to stop tethering teaching to “seat time” – where students are grouped by age and taught at a uniform, semester pace – and instead adopt competency-based education, in which students progress through skills and concepts by demonstrating proficiency.

That alone isn’t unusual; a majority of states now allow competency-based pilot programs, and many schools have fully implemented the approach. What makes Northern Cass notable is that very few mainstream schools, let alone districts, have set out to topple grade levels.

But as the movement against seat-time learning grows, more schools nationwide will be grappling with grade levels, deciding whether to keep them or to hack through thickets of political, logistical, and cultural barriers to uproot them.

Some school leaders insist that competency-based education can survive and even thrive within grade levels, or a modified version of them. Others, however, echo Northern Cass superintendent, Cory Steiner.

“We can’t keep structures that would allow us to fall back into a more traditional system,” says Mr. Steiner. “If we’re going to do this, we’re going to have to manage without grade levels.”

While seat-time schooling is fiercely opposed by reformers, it is backed by state and federal law. Northern Cass’s reforms rely on North Dakota’s 2017 decision to let districts apply for waivers from requirements such as hours of instruction.

Most states have something on the books to encourage competency-based options, but only about a half-dozen states have loosened dictates enough to dispense with grade levels, according to Matt Williams, chief operating officer and vice president of policy and advocacy for the personalized-learning nonprofit KnowledgeWorks.

In North Dakota, Mr. Williams and his colleagues worked with Kirsten Baesler, the state superintendent of public instruction, to write the waiver bill, and Northern Cass leaders lobbied legislators to pass it.

They pushed for radical change even though North Dakota districts were doing well by traditional measures, such as graduation rates, ACT scores, and the National Assessment of Educational Progress, on which the state regularly ranks among the top 15 in most subjects and grade levels tested.

According to Ms. Baesler, however, “We were too often teaching to a test. Educators wanted students to engage more and apply their learning in meaningful ways.”

For students, more autonomy

Northern Cass took the first steps toward that goal this past school year. A few dozen teenaged students left their grade levels behind for three periods a day during Jaguar Academy (named for the district’s feline mascot) and moved through select courses with a mix of online lessons and teacher-led seminars. Some finished the material pegged to their grade levels by mid-year and moved on, while others took more time.

As a first-year pilot, Jaguar Academy is just part of the larger overhaul, which includes reworking both academic content and “habits of work,” such as perseverance and collaboration, into progressions of competencies free of grade-level expectations.

But the program is one of the district’s first forays into a grade-free future. It plans to expand the pilot until it’s an option for all students in what are now called the eighth through twelfth grades.

For students like Katelyn Stavenes, a rising ninth-grader, Jaguar Academy is a welcome taste of autonomy.

“I can just lean back and do my stuff instead of always watching the clock and wondering, when can I get out of here?” says Katelyn.

At Northern Cass, momentum for change began during the district’s 2016 accreditation renewal when staff checked up on students after graduation. They found that graduates’ college grades tended to dip compared to their high-school GPAs, and the students bounced around a lot – switching majors, transferring to other universities, or dropping out. District leaders decided they hadn’t done enough to prepare students for life after high school.

According to Melissa Uetz, a special education teacher who became Jaguar Academy’s lead facilitator, the message was, “We needed to help kids find their passions before they left school.”

That meant more flexibility and potential for exploration in student schedules. The primary goal for Jaguar Academy was to give high school students more opportunities for job shadows and internships. More proposed changes spiraled out from there, including the decision to do away with grade levels.

“Teachers said, ‘If this is good for kids, why not bring it to all of them?’ ” Steiner says. “Our conversation went from Jaguar Academy to ‘What if we tore the whole system down?’ ”

Navigating the issues of tests, self-pacing

Of course, no matter what individual states and districts allow, federal law still mandates grade-level-pegged testing. Education departments use those scores to evaluate schools. Quite often, so do parents.

California’s Lindsay Unified School District, which switched to competency-based education years ago and has been mentoring Northern Cass, kept grade levels because of standardized tests. Lindsay Unified’s director of advancement, Barry Sommer, says he would love to scrap grade levels, because they get in the way of “truly moving to a 21st-century school that’s learner-centered.” But California’s district-accountability tracking system is based on grade-level achievement tests.

For testing and student data reporting, Northern Cass still plans to link students with an expected year of graduation.

“We’ll do whatever we have to do for testing,” Steiner says. “But we won’t put any extra effort or incentive into [the tests].”

Then there’s the question of whether to place limits on how quickly or slowly students move through competencies. For instance, another of the districts mentoring Northern Cass found that just letting students work at their own pace led some kids to slack off and disrupt classmates.

“I remind teachers that we need to put some controls on this,” says Bill Zima, superintendent of the district in question, Maine’s Kennebec Intra-District Schools regional school unit #2 (RSU2). “First-graders are not ready to completely manage their time. Nor are seniors. Nor are adults, really.”

The solution for some is grouping in a single classroom kids who would traditionally be in two or three different grade levels – a longstanding practice of Montessori schools.

“A lot of schools are finding ways to blur grade levels rather than getting rid of them,” says Karla Phillips, policy director for personalized learning at the Florida-based Foundation for Excellence in Education, or ExcelinEd.

At Northern Cass, teachers plan to step in if a student gets more than three weeks behind or ahead of an expected “teacher pace.” Students who struggle will get extra support. Students who speed ahead will get a conversation about next steps.

“Maybe we let them fly,” says Steiner. “Or maybe they want to do an independent project, or work as a peer teacher, or go back to work more on a competency where they’ve struggled.”

Meanwhile, the district is also reworking teacher assignments. Last year, for example, the elementary teachers stopped being generalists and started to specialize. The idea is that teachers will encounter students in a broader range of ages and abilities, but only in their academic areas of expertise.

Breaking with cultural norms

After cutting the regulatory red tape and solving the logistical puzzles, a deeper challenge remains in the move away from seat-time. Grade levels are part of our culture, deeply rooted in how we think about learning and childhood more broadly.

“When you meet somebody and ask how old their kids are, they say, ‘Oh, they’re in third grade or fourth grade,’ ” notes Ms. Phillips.

Cultural norms have kept grade levels partially intact in Maine’s RSU2 district, which has hosted Steiner and Northern Cass teachers many times.

Back at Northern Cass, however, they believe that grade levels would become a crutch for students and teachers and ultimately stymie reform. “We know that we’re taking a big leap and not everybody’s going to be on board,” says Steiner.

This summer, Northern Cass teachers and administrators have been rewriting lesson plans and assessments. They’ve also been visiting more-experienced competency-based districts such as Lindsay Unified. By 2020, Steiner wants Northern Cass to be the district hosting visitors, as a mentor to other schools mulling the idea of nixing grade levels.

“On their way to visit Lindsay or another of these pioneering schools, they can stop in North Dakota,” he says, “because there’s a school out in the middle of a cornfield that’s doing this transformative work.”

This story about competency-based education was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Trump enlarges his vision on trade

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A substantive agreement on trade between the United States and European nations is far from assured. All 26 European Union member states still need to agree to proposed talks. Nevertheless, the new perspective is that both parties can emerge winners. On another big trade front – renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement – President Trump has spoken positively with Mexican President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador about reaching an agreement. The reasons for the shifts in tone are widely debated. Some experts ask if they are sincere or just tactical. But worth underscoring is that a key change in the US perspective appears to be a desire to facilitate solutions for all. This shift to a climate of give-and-take allows all sides to fix problems and open up market opportunities for workers, farmers, businesses, and consumers. Rather than fight over a bigger piece of the current economic pie, the parties can grow the pie. Progress in trade negotiations have long rested on the knowledge that economies will make progress if they include more players rather than exclude them.

Trump enlarges his vision on trade

After starting trade skirmishes with America’s closest economic partners, the Trump administration may be moving toward resolutions that could bring substantial benefits – and not only on trade itself.

The latest shift was President Trump’s July 25 agreement to negotiate key trade and economic issues with the European Union. The two sides also called a temporary halt to imposing further tariffs while the talks move forward. Significantly, Mr. Trump said both sides of the Atlantic could win in this “new phase” of the relationship. This is a notable improvement in tone from his recent reference to the EU as a principal “foe.”

A substantive agreement is far from assured. European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker still needs all 26 EU member states to agree to the talks. Nevertheless, the new perspective is that both parties can emerge winners. This is significant because the trans-Atlantic economy is the world’s largest. Trade and investment between the EU and the United States employs about 9 million workers and supports as many as 15 million jobs.

On the other big trade front – renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement – Trump spoke positively with Mexican President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador (aka AMLO) after his July 1 election victory about reaching an agreement on updating NAFTA. The two men followed up with a positive exchange of letters, in which Trump wrote that a successful renegotiation of NAFTA “will lead to even more jobs and higher wages for hard-working American and Mexican workers.”

Although Trump added a threat that the negotiation should go quickly or he would “go a much different route,” he and AMLO avoided clashes over hot-button issues related to immigration, and supported a rapid return to negotiations. US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer subsequently told Congress he hopes to complete the basic NAFTA negotiations in August. Mexican and Canadian trade ministers have echoed that goal.

As with the EU, the stakes for North America are high: $1.2 trillion in current trade and as many as 14 million US jobs (as well as millions more in Mexico and Canada, America’s largest export destinations).

The reasons for the shifts in tone are widely debated. Some experts ask if the US change in tone is sincere or just tactical. Others surmise that the forceful concerns of US farmers, businesses, and legislators about the combined harmful effects of so many conflicts with trading partners had an impact on the White House. The president and his supporters argue that his tough approach has led America’s partners to come up with attractive offers for the US.

Worth underscoring is that a key change in the US perspective appears to be a desire to facilitate solutions for all. Many observers have lamented that a big obstacle has been a US attitude that trade conflict must be “win-lose,” with the US as the clear winner.

This shift to a climate of give-and-take allows all sides to fix problems and open up market opportunities for workers, farmers, businesses, and consumers. Rather than fight over a bigger piece of the current economic pie, the parties can grow the pie. That approach helps build political support for an agreement at home – although each country must also assist industries and workers in adjusting to heightened competition.

The NAFTA talks will be the first test for this new perspective. All sides agree the treaty needs an update after 25 years. Much technical work is needed to fix the 30-odd chapters of the treaty, which alone will bring challenging issues. On the political level, a handful of proposals raised by the US are being resisted by Mexico and Canada. These include rules for making vehicles, provisions to settle disputes, and the issue of whether to include a five-year “sunset clause” in which all three countries must agree to continue the treaty. Canada and Mexico, as well as many people in the US, say the uncertainty of such a sunset clause would undermine long-term investments.

As it tries to reshape global norms to ensure commerce keeps expanding, the US needs all the allies it can get. This makes it important to adopt a perspective that allows trade “wins” for all.

Progress in trade negotiations has long rested on the knowledge that economies will make progress if they include more players rather than exclude them.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding promise for the future

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Deborah Huebsch

Today’s column explores how the idea that God is supreme – now and always – helps calm fears about the future.

Finding promise for the future

Sometimes, in the middle of the night, I’ve awakened in a sheer panic. Often the fear is specific; at other times, just a general foreboding that bad things are going to happen. Or it might relate to something I heard on the news. But here’s the common thread: fear of the future. Is there any way we can feel secure about what lies ahead in our lives – for ourselves and for the world?

Something that helps me is a growing understanding that I can depend on God’s loving presence, no matter what the situation. Through my study of Christian Science, I’ve begun to see that God’s hand is at the helm. During fearful moments, one thing that’s been especially helpful is a statement made by the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, in one of her poems. She wrote, “O Life divine, that owns each waiting hour” (“Poems,” p. 4).

What a promise for the future lies in that statement! Instead of fearing the worst, we can begin to trust that Life, another name for God, is not only present now, but actually always has been, and it “owns” our future. One definition of “own” is to recognize as having full claim, power, authority, and dominion over something.

What can we expect from this divine Life? The Bible is a great source of inspiration in answering this question. One helpful passage reads, “The eternal God is thy refuge, and underneath are the everlasting arms” (Deuteronomy 33:27). To see ourselves as safe and cared for by the divine All-power now and always helps calm fear that would keep us from making progress.

This isn’t just an abstract concept. In my own moments of fear, “what ifs” and “oh nos” try to dominate my thinking, but when they do, I’ve found that it’s possible to shut off that chatter. Not through burying our heads in the sand or ignoring potential problems, but through allowing God to be heard by opening our thoughts to God’s presence, listening for God’s healing messages, which relieve fear.

Answers and reassurances then come to thought, often with an encompassing sense of God’s goodness. Sometimes an inspiring word or familiar phrase comes to mind that lifts us above the turmoil, bringing a distinct shift in thought, from fear to a clear sense of expectancy that everything will be all right.

This release from fear of the future doesn’t always happen quickly. Sometimes it takes persistence and a commitment to sticking with what God is conveying, even if it feels difficult to fathom at first. But I’ve found it’s always worth the effort, because it brings about peace and hope – not only regarding our individual lives, but also about the future of our world at large. This doesn’t mean that we don’t still face challenges. But accepting that divine Life really does own each moment gives us confidence that takes away our fears.

A message of love

In fire’s wake

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. We hope you’ll come back tomorrow when staff writer Linda Feldmann looks at the prominent Republicans – and some now ex-Republicans – taking on President Trump. What happens when you feel your party has left you?