- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Why US talks with Taliban are suddenly on the table

- GOP squeaks by in another special election – but warning signs abound

- Despite spike in shootings, a Chicago community gets a handle on violence

- For these pastors, protest has become an act of faith

- Science meets history: sorting the saga of the first Americans

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for August 8, 2018

Recent weeks have put on display the power of speaking up.

Take human rights. In late July, thousands of teens took to the infamously dangerous streets of Dhaka, Bangladesh, after two students were killed by bus drivers racing to get new customers. For days, they enforced traffic laws and raised their voices for justice. They want safer streets but are more broadly targeting a culture of impunity around law enforcement.

In another case, Canada raised its voice against Saudi Arabia’s detention of women’s rights activists. Those include Samar Badawi, the sister of a dissident blogger. When Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland tweeted Aug. 2 that she was “very alarmed,” her country brought to the fore that recent social and economic reforms go only so far.

Speaking up, of course, has its perils. Bangladesh now has tougher penalties for reckless driving – a gain for students. But the increasingly authoritarian country also sent a chill with its demand that teachers start recording the names of students who miss class. Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, has reacted harshly, expelling Canada’s ambassador, bringing home Saudis studying in Canada, and ending new trade deals.

But the broader the forum for speaking up thoughtfully, the better. In the US, that’s playing out in a particularly powerful way, despite a contentious political atmosphere: with lots of new faces running for office and strong signs that there are lots of new faces among voters, too.

Now to our five stories, showing how people are thinking in new ways about peacemaking – in the neighborhood as well as on the battlefield.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Why US talks with Taliban are suddenly on the table

Is it as simple as the existence of a common enemy, ISIS? Some see a more complex motive: a US foreign-policy bureaucracy, wary of an uninterested and unpredictable president, trying to maintain a commitment to Afghanistan.

Alice Wells, the top US diplomat for South Asia, met last week with senior Taliban officials. Why would the United States be talking now with the insurgency it pushed out of power for harboring the 9/11 masterminds? One answer is the Islamic State, which is competing with the Taliban in parts of Afghanistan. Another is President Trump’s view of Afghanistan as a “bad investment.” “Suddenly … the Taliban [have] become the best of bad options for controlling ISIS in Afghanistan,” says Nicholas Heras of the Center for a New American Security. But some former officials say the overture has more to do with State and Defense Department officials trying to anticipate and influence presidential action. “There’s a lot of concern in the bureaucracies of an abrupt action by the president to upset the appearance of commitment to Afghanistan,” says one former official, who requested anonymity. Mr. Heras sees the Washington debate “boiling down to two irreconcilable elements:” that Afghanistan in the era of “America First” becomes less and less relevant, and that the immense investment of American blood and treasure makes an honorable exit that upholds US interests a must for many.

Why US talks with Taliban are suddenly on the table

The United States has a lot invested in Afghanistan: a longer war than both world wars and its intervention in Vietnam combined, more than $2 trillion, and more than 2,370 service members’ lives lost.

So why would the US choose now to enter into talks with the Taliban, the Afghan insurgency the US pushed out of power in Kabul in 2001 for harboring the Al Qaeda masterminds of the 9/11 attacks?

To understand the mounting signs of the Trump administration’s interest in negotiating some form of political deal with the Taliban, consider the conjunction of two key factors.

First is a US president, in Donald Trump, who has long considered Afghanistan a “bad investment” and who wants the nearly 15,000 US troops he begrudgingly agreed to keep there withdrawn – sooner rather than later.

Second is the presence in Afghanistan of the Islamic State. Despite pressure from both the US and the Taliban, ISIS continues to be an instigator of havoc inside the country and a cause for concern over the radical group’s potential to undermine broader regional stability.

Combine President Trump’s “America first” foreign policy, which promised to get the US out of “stupid” wars, with an equal promise to keep Americans safe from the terrorism of a West-hating extremist group like ISIS – and indeed to destroy it – and one outcome is talks with the Taliban, some regional experts say.

“There’s a certain logic to engaging with the Taliban now if you take together that President Trump was dragged kicking and screaming into the current Afghanistan strategy” of keeping thousands of US soldiers on the ground “with the fact that ISIS is still able to co-opt or flip parts of the country in the Taliban’s hands,” says Nicholas Heras, a Middle East security fellow at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) in Washington.

“Suddenly for the US, as well as for all the regional actors with an interest in the conflict,” he adds, “the Taliban become the best of bad options for controlling ISIS in Afghanistan.”

Last week the top US diplomat for South Asia, Alice Wells, met with Taliban senior officials in Doha, Qatar, where the insurgency has a political office. The State Department did not confirm the Taliban’s statement that the meeting took place, saying only that Ms. Wells was in Doha as part of efforts to “advance a peace process in close consultation with the Afghan government.”

The meeting has since been characterized by both current US officials and former officials keeping close ties to the Trump administration as a preliminary exploration of future peace negotiations on Afghanistan, or “talks about talks.”

Concern at State and Defense

But for some former officials, the US initiative has more to do with foreign policy players that are supportive of maintaining a significant US role in Afghanistan – namely the State and Defense departments. According to the former officials, these policy-making bureaucracies are seeking to get out ahead of a president known for both sudden policy decisions and a dislike for the current Afghanistan policy.

Noting that the one-year anniversary of Mr. Trump’s reluctant decision to OK a mini-surge is coming up, one former US official says the recent Afghanistan diplomacy reflects a Washington apparatus trying to anticipate and influence presidential action.

“There’s a lot of concern in the bureaucracies of an abrupt action by the president to upset the appearance of commitment to Afghanistan,” says the former official, who requested anonymity to speak more openly. Citing the weekend killings in eastern Afghanistan of three Czech NATO soldiers in a suicide bombing claimed by the Taliban, the former official added, “The worry is that something like that could trigger” presidential action. “What if it were 10 Americans killed, and the news of it was carried in banner headlines across the front pages?”

Others flatly deem the recent meeting a mistake. Ryan Crocker, a former US ambassador to Afghanistan, is publicly airing his view that “nothing good” can come from talks that did not include any Afghan government representation.

Speaking on NPR Friday, Ambassador Crocker said the Taliban had scored a victory by holding talks with the US while excluding the government in Kabul, which the insurgent group portrays to the Afghan people as the “puppet government” of the US.

The US strategy in Afghanistan has broadly been to train and support national security forces capable of securing the vast country and to fortify the country's political stability. But the building up of these forces has been hampered by desertions and high casualties, while the government in Kabul has been undermined by political infighting and allegations of rampant corruption.

Of course, a morning tweet could change everything, but to this point, the president has shown no keen interest in Afghanistan policy, as some regional experts note.

Risk for Taliban, too

“I don’t know whether he’s spoken to it internally, but he hasn’t externally in any substantial way that we know,” says Laurel Miller, a senior foreign policy expert at the RAND Corp. in Arlington, Va. “It’s kind of a question mark where the White House is” on Afghanistan.

Ms. Miller, who served as the State Department’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan until the position was eliminated last year, says the Taliban also assumed some risk in meeting with the US to discuss potential peace talks. Noting that the Taliban’s comparative advantage vis-à-vis Kabul has always been its internal cohesion, she says the recent contacts may well have sown division among the ranks, with some opposing any suggestion of compromise with the US.

“The downside for them is the possibility that this step risks fracture” within their ranks, she says. “The upside is that it allows them to say, ‘See, this reinforces our view that this is just about the US’ and not, in their words, the ‘puppet regime in Kabul.’”

Where everyone seems to agree is on the point that any movement toward a peace settlement is in its very early stages – and may yet fizzle out. Afghanistan holds local elections this fall and then national elections, including for president, next spring – events that have drawn an uptick of violence in the past and hardened stances over political settlement with the Taliban.

Mr. Heras of CNAS says he sees the discussion in Washington of the way forward in Afghanistan “boiling down to two irreconcilable elements:” that Afghanistan in the era of “America First” becomes less and less relevant; and that the immense investment of American blood and treasure in Afghanistan makes an honorable exit that upholds US interests a “must” for many.

Those interests include a stable government in Kabul and guarantees that rights instilled by the long US and Western engagement, such as those of women and girls, will be maintained in some form.

A not-so-distant withdrawal

But at the same time, shifts in the US role in the country suggest to Heras that the US is trying to prepare the country for a not-so-distant withdrawal. Those include a move to refocus the efforts of US and NATO forces in securing Afghanistan’s urban areas – and a strategy encouraging NATO-trained Afghan security forces to largely pull back to the cities as well.

What the Pentagon and State Department want to avoid is a “Vietnam-type pullout” that leads in short order to a government collapse, Heras says.

And in any case, the presence of ISIS in Afghanistan, even if weakened, means that a US withdrawal is unlikely to be total, analysts say.

“Even if there is a peace settlement and a drawdown of most US and NATO forces, the US will have an interest in keeping some counterterrorism capabilities to confront ISIS and the remnants of Al Qaeda,” Miller says. She notes that while ISIS in Afghanistan may now be “internally focused,” the “open question” remains: “If left unchecked, could it be transformed into a transnational threat?”

Indeed, Heras says the “common concern” over ISIS among nearby actors – from Russia and Iran to next-door neighbor Pakistan – means that the region is likely to support an eventual peace settlement that recognizes a continuing US counterterrorism role in the country.

Share this article

Link copied.

GOP squeaks by in another special election – but warning signs abound

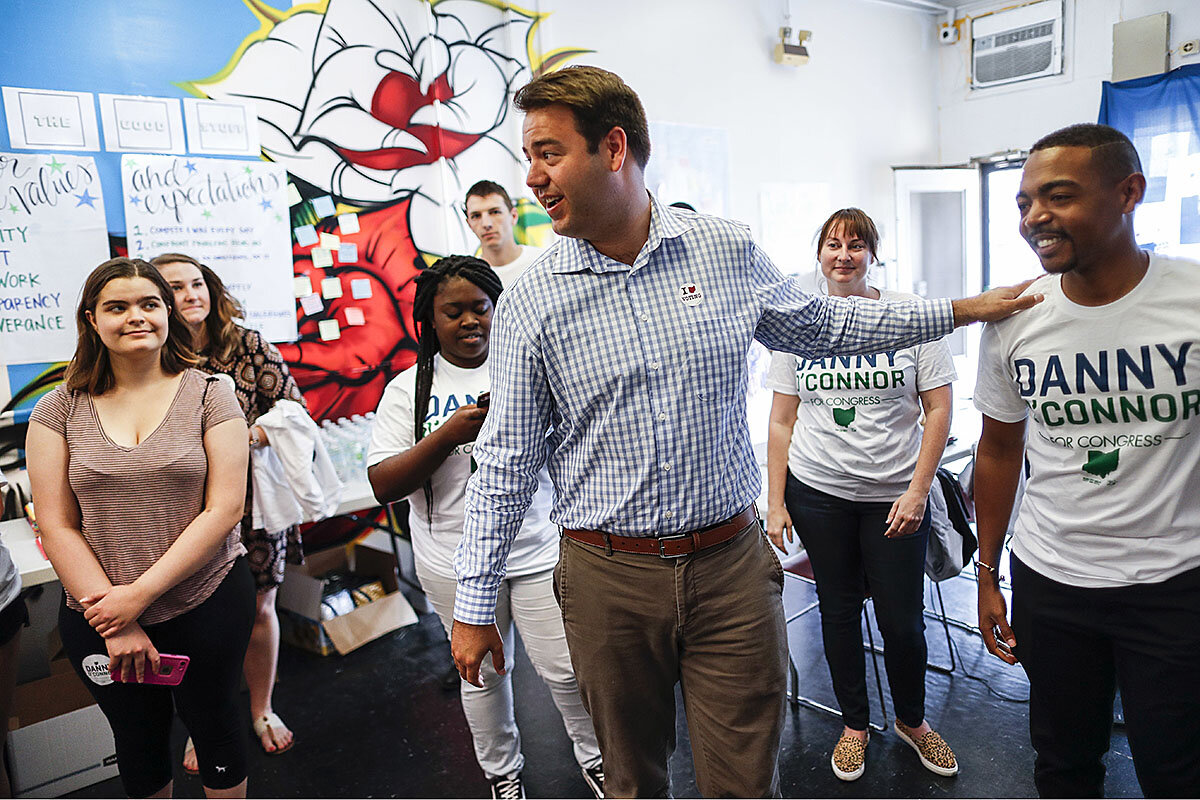

In Ohio’s 12th Congressional District Tuesday, suburban voters, particularly women, moved further away from the GOP. The trend is forcing Republicans to rely more on rural, blue-collar turnout – a narrower path to victory.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Winning, of course, is always better than losing. But the narrowness of Republican Troy Balderson’s apparent victory in the special congressional election in Ohio on Tuesday suggests a “blue wave” may be heading for many suburban districts. In 2016, President Trump carried the suburban Columbus district by 11 percentage points, and yet Mr. Balderson is leading by less than 1 percent, with provisional and absentee ballots still being counted. It’s true that the first midterm elections of any presidency almost always produce a partisan backlash. Democrats under President Barack Obama got “shellacked” – his word – in 2010. This year, Republicans are running under a controversial president who’s generating a severe gender gap, with suburban college-educated women increasingly wary. “There’s no question that there’s been shrinkage in the party in urban and suburban areas,” says Doug Preisse, the GOP chair in Ohio’s Franklin County. “I did get lifelong Republicans in the district ... letting me know that the president’s visit caused them to shy away from voting for Troy. But I also witnessed people being reminded of the importance of the race, and deciding to turn out.”

GOP squeaks by in another special election – but warning signs abound

Republicans are cheering their likely victory in Tuesday’s special election to fill an open House seat in Ohio. Winning, of course, is always better than losing. But in the Republican corridors of power, both in the Buckeye State and in Washington, the cries of joy are muffled.

The narrowness of state Sen. Troy Balderson’s apparent victory suggests a “blue wave” may be heading right for suburban districts currently held by Republicans – where GOP women, in particular, are increasingly wary of President Trump. And even if Mr. Balderson keeps Ohio’s 12th Congressional District in the Republican column, other districts with less of a GOP tilt could flip.

In 2016, Mr. Trump carried the suburban Columbus district by 11 percentage points, and yet Balderson is leading by less than 1 percent, with provisional and absentee ballots still being counted. This narrow margin continues the trend of Republicans underperforming significantly in special House and Senate elections since Trump took office.

“There’s no question that there’s been shrinkage in the party in urban and suburban areas,” says Doug Preisse, chairman of the Republican Party in Ohio’s Franklin County, part of which falls in the 12th district.

Some of the challenge for Republicans lies in running under a controversial president, particularly one facing a severe gender gap – 12 points, according to Gallup nationwide polling. Millennial women are an especially tough sell for Trump; 70 percent now identify as or lean Democrat.

It’s true that the first midterm elections of any presidency almost always produce a partisan backlash. Democrats under President Barack Obama got “shellacked” – his word – in 2010.

Still, Mr. Preisse calls the closeness of the Ohio-12 race a “canary in the coal mine” in the run-up to Nov. 6, when every House seat will be on the ballot as well as a third of the Senate.

“If Balderson had lost, then there would be a turkey-sized canary in the coal mine,” Preisse says. But a close victory signals a regular-sized canary, and “it will keep chirping till November.” This was the last special election before the midterms, and the candidates will go head-to-head again in November.

Turnout and the Trump factor

On Tuesday, turnout was the name of the game. In Franklin County, which covers Columbus, turnout was larger than in the district’s other counties – almost handing the election to Democrat Danny O’Connor, a popular local official.

The timing also mattered: It’s August, and a lot of voters are out of town.

“Democrats used early voting to get their vote out over a month, while the Republicans vote on Election Day,” says Jay O’Callaghan, a former US House GOP staffer.

Preisse expects a more traditional turnout in November, with more people voting, and predicts Balderson will probably win again. But there are plenty of other districts available for Democrats to flip. To retake the House, they need a net gain of 23 seats; the GOP is defending 72 districts that have less of a Republican tilt than Ohio-12.

The Trump factor bears watching, but how that nets out is hard to gauge. Did Trump’s last-minute rally in Delaware County spur his supporters to turn out, or did it inspire anti-Trump voters? Preisse says it likely cut both ways.

“I did get lifelong Republicans in the district – not only from Franklin County but also Delaware County – letting me know that the president’s visit caused them to shy away from voting for Troy,” says the Franklin County chairman. “But I also witnessed people being reminded [by Trump] of the importance of the race, and deciding to turn out.”

Another key figure may also have had an impact: Ohio’s Republican governor, John Kasich. He’s a frequent Trump critic, and has hinted at a primary challenge in 2020, but on this issue – the need to keep Governor Kasich’s former House seat in GOP hands – they agreed.

The mild-mannered, mainstream Balderson, in fact, is hardly a Trumpian figure, and getting the stamp of approval from Kasich, also a mainstream Republican, perhaps helped buffer any negative fallout from Trump’s touch.

Big Labor wins big

For Democrats, the best news of Tuesday night came in Missouri, where the labor movement defeated a “right to work” measure that would have dealt a major blow to unions. The referendum asked voters to affirm or reject a new state law barring mandatory payment of union dues by workers. Voters defeated the measure 67 percent to 33 percent, making Missouri the first state to turn back a “right to work” law in decades.

“We thought we might win by 10 or 15 percent,” says Julie Greene, mobilization director at the AFL-CIO, the nation’s largest federation of unions. The big margin “was really just a testament to the [outreach] program.”

National labor forces allied with Missouri’s unions to reach out to workers at their jobs and via phone-banks, door-to-door, mail, and online. The key was to start early, take nothing for granted, and reach far and wide, not just to union members and families, says Ms. Greene.

“Unionization hits at kitchen-table issues, which affects many more than just union members,” she says.

Labor’s political operations are focused, too, on the midterms – and were on the ground in Ohio’s 12th district, as they were last March in a special House election in Pennsylvania, where Democrat Conor Lamb won in an upset. Most, but not all, labor endorsees are Democrats.

At a Monitor Breakfast last Wednesday, AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka spoke of labor’s early start in mobilizing this election cycle. Normally, he said, door-knocking and phone banks start after Labor Day. This year, they started June 1.

“This is going to be the biggest, deepest member-to-member program that we’ve ever had,” Mr. Trumka said.

Despite spike in shootings, a Chicago community gets a handle on violence

When the relationship between law enforcement and crime-ravaged communities is adversarial, it can perpetuate a dangerous cycle. But in this community, residents and police have converged to bring tangible progress.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

-

By Nissa Rhee Correspondent

Even as it struggles with spates of violence like last weekend’s – more than 75 people were shot, with a dozen killed – Chicago has reduced the number of shootings since the spike in shootings in 2016. The South Side neighborhood of Englewood leads the way. It cut homicides and shootings by nearly twice the citywide rate. Last year it saw the lowest level of gun violence since police started keeping records in 1999, though violence persists. Law enforcement has played a role. Police reinvented how they deploy officers and work with the community. They use predictive data. But the real key to the reductions has been a joint effort by community members and police officers to target the places most dogged by violence. Mothers sit out on the most violent corners, and a coalition of organizations provides therapy and job training to the men most likely to shoot or be shot. Terrence Jackson enrolled in a job-training program that broke a cycle of jail and release. “A lot of guys can’t walk from block to block in their neighborhood,” Mr. Jackson says, because they can’t cross gang territories. “But here, we walk together.”

Despite spike in shootings, a Chicago community gets a handle on violence

On a recent Monday afternoon, a dozen boys and girls are shooting hoops at the outdoor courts of Ogden Park on Chicago’s South Side – something that not long ago, few dared to do in this neighborhood of Englewood, which has long struggled with gun violence.

“At one point, these guys couldn’t even come out and play ball,” says Chicago police officer Morris Brown, watching the teens from his patrol car. He grew up here and has spent the past 18 years serving as an officer in Englewood. “You’d go a whole day and no one would come out to the basketball court.”

Selling snow cones from their porch across the street, middle-aged twins Denise and Dennis Hamilton remember those darker days well. Their brother, Paul, was killed by stray bullets in the park in 2016.

“It was Labor Day and he was out walking the dog,” Denise recalls. Two others were killed by gunshots in the park that year, including a young man playing basketball with his brother.

That was Chicago’s most violent year in nearly two decades, with more murders than New York and Los Angeles combined. But since then, the city has made impressive strides toward becoming a safer place. Even as it struggles with spates of violence such as during the first weekend in August – when more than 75 people were shot and 12 died – Chicago has steadily reduced the number of shootings over the past two years. And Englewood is leading the way.

Even as Chicago has seen a steady decline in violence, this South Side neighborhood has cut its homicides and shootings by nearly double the rate seen citywide, reducing them by nearly half – the equivalent of saving 21 lives. In 2017, the neighborhood saw the lowest level of gun violence since the police department started keeping records in 1999.

The key to the reductions in Englewood, researchers and residents say, has been the coming together of community members and police officers targeting the people and places most plagued by violence. Here, mothers sit out on the most violent corners, police officials have reinvented how they deploy officers and work with the community, and a coalition of organizations provides therapy and job training to the men who are most likely to shoot or be shot.

And while gun violence remains a problem in this neighborhood, with 29 murders occurring in the first seven months of this year, the decline in violent crime is starting to be felt by people in the hardest-hit areas.

***

It was eight years ago this summer that Mario lost his 9-year-old sister, Chastity. She had been sitting outside washing her pit bull, Pinky, when gang members sped by in a van and started shooting, targeting her father in a gang-related conflict. He survived, but she was killed.

A few years ago, volunteers from a group called Mothers Against Senseless Killings started bringing their lawn chairs and sitting in a vacant lot just two blocks away. They feed neighborhood kids every evening during the summer.

At first, Mario didn’t know who they were or why they were there. But he’s gotten to know them over the years and even helps them hand out food now.

“They’ve made a big difference in the neighborhood,” he says. “People from everywhere come over here on this block to eat. A lot of people didn’t want to come out on this block before, but they come out here now. [The volunteers] helped stop the violence in the neighborhood.”

Located just two miles southwest of former President Barack Obama’s house, Englewood is a predominantly black and impoverished neighborhood. People here are 24 times more likely to die from gun violence than someone living in the city’s prosperous downtown Loop neighborhood.

In 2008, actress Jennifer Hudson’s mother, brother, and nephew were shot and killed here. The neighborhood was also the setting for Spike Lee’s 2015 musical film, “Chi-raq,” a retelling of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata centered on gang violence. But behind the headlines are systemic problems.

“This kind of gun violence really comes out of the continued conditions of disinvestment, lack of access to quality education with school closings, and minimal access to job opportunities,” says Tonika Johnson, program manager for the Resident Association of Greater Englewood.

In 2015, 36 percent of Englewood residents were unemployed and 58 percent made less than $25,000 a year. The neighborhood has struggled with population loss as people flee the violence and search for better economic opportunities. While there have been some glimmers of revitalization in recent years with the opening of a new Whole Foods grocery store and a $33 million outpatient care center, the effects of decades of disinvestment are not easily reversed. Many say it takes a community-wide effort.

“You can’t just expect policing to solve it. That’s not going to work,” says Ms. Johnson, who helps lead the neighborhood’s Public Safety Task Force. “You can’t just expect residents to be able to work alone to solve it. It really has to be a combination of things.”

On a recent Thursday evening, Johnson is among a dozen representatives from Englewood’s violence prevention organizations sitting in tired fabric chairs at Canaan Community Church eating baked chicken and green beans. Near the back is Seventh District Police Cmdr. Kenneth Johnson, fully at home in the church. He and his twin brother, Kevin – who aren’t related to Tonika – attended the Archbishop Quigley Preparatory Seminary in downtown Chicago and at one time considered becoming priests. Instead, they chose a different kind of service.

Kevin Johnson now commands a police district struggling with violence on Chicago’s West Side, while Kenneth leads the police in the Englewood neighborhood. Kenneth assumed command of the Seventh District in August 2016, as gun violence was soaring and the Department of Justice was investigating the Chicago Police Department for excessive use of force.

Seeing an opportunity to break with the police department’s controversial past, Kenneth adopted a new strategy in Englewood: Officers would take a more active role in the community and employ new technologies to predict and see violence as it is unfolding.

“We have to be more than police officers, more than law enforcement,” he says. “We have to be good community partners.”

So when three homicides took place at an Englewood park just after he took command in 2016, Kenneth worked with the park district, the local government representative, and community members to clean the park, trim the trees, and paint a field house. He also set up an enforcement area around the park so that officers paid more attention to the thriving drug market there. Since then, there hasn’t been a single shooting or homicide in the park.

The police commander’s strategy appears to be working across the neighborhood. A study conducted by the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab, which compared Englewood with similar areas around the city, found that nearly 80 percent of the decline in shootings in Englewood could be attributed to changes in policing, especially the establishment of a Strategic Decision Support Center in the district in February 2017. (The Crime Lab helped launch the SDSC, but it is an independent group.)

***

The SDSC is only the size of an apartment kitchen, but it has dramatically changed how quickly the police respond to shootings in Englewood and how they deploy their resources. Analysts and police officers hover over a bank of computers and maps showing crime data going back five years as well as predicted crime patterns provided by HunchLab.

“We find that the growing use of data-driven policing has had a particularly pronounced impact on gun violence in Englewood,” says Jens Ludwig, faculty director at the Crime Lab, adding that the new policing changes in the district accounted for as much as a 15 percent drop in Chicago’s overall decline in shootings from 2016 to 2017, despite Englewood making up only 3 percent of the city’s population.

Large-screen TVs on the walls of the SDSC stream video from about 120 surveillance cameras positioned across the district. Maps also show where officers are currently responding to calls and the location of recent gunfire detected by ShotSpotter,

a system of microphones dotting the neighborhood.

Lt. Laura West, who oversees the Seventh District SDSC, says the center has allowed officers to use this surveillance technology at the neighborhood level, as opposed to just in the department’s main headquarters. Cameras that used to be looked at only after an incident took place are now monitored 24 hours a day. All officers in the Seventh District have access on their smartphones to the maps and information developed by analysts in the SDSC room.

The change has meant that police are investigating shootings often before people start calling 911. When a gunshot is detected by ShotSpotter, its location lights up on one of the maps and the officers switch to a nearby high-definition surveillance camera.

“We can get to that corner before the [patrol officers] do and let them know what’s happening,” West says. “It’s a game changer, really.”

Getting to the scene of a shooting faster means that police can pick up evidence before it is destroyed or removed and even catch criminals in the act. While overall arrests are down, gun-related arrests are up 25 percent in the district from last year.

But the new center also means that the police are constantly watching community members, even those who are not committing a crime. On a recent day, an officer was switching from camera to camera following a black man in a red vest as he walked along the sidewalk, stopping at a gas station and chatting with some friends. He was not doing anything illegal, and wasn’t even aware that he was being observed.

It’s a controversial strategy in a city where black and Latino residents often complain about illegal stops and searches and surveillance by police. Chicago has one of the most extensive and integrated camera networks in the United States, and the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois has pushed back against the SDSC.

“Residents and visitors to Chicago continue [to live] without protections from these powerful, invasive systems,” says Ed Yohnka of the ACLU of Illinois. “We remain concerned that the city of Chicago continues to expand intrusive surveillance systems – including the Strategic Decision Support Center and a proposal to expand the use of drone surveillance – without appropriate and necessary public transparency.”

***

Three miles to the south of Englewood’s SDSC, a different sort of eyes survey the streets. Sitting in hot pink lawn chairs, the volunteers of Mothers Against Senseless Killings (MASK) are watching over about a dozen kids eating pizza and brownies at a vacant lot on the corner of 75th and Stewart. One man rakes up trash, while two women plant flowers and vegetables.

Eight days earlier, before MASK had begun its summer sit-outs, this corner was a very different place. Empty chip bags and beer bottles were strewn throughout the lot. A group of young men were hanging out in front of the liquor store across the street, which advertised “cut rate” booze. Tension filled the air. That night, a 46-year-old man was shot four times in the back here. Thankfully, he survived.

Since 2015, MASK has been coming to this corner from 4 p.m. to 8 p.m. on most summer days, barbecuing and playing with neighborhood kids. A volunteer group that runs on donations, MASK regularly feeds as many as 150 kids and adults from the area. “This is called watching the kids,” says MASK founder Tamar Manasseh, who was inspired to start coming to this corner after a mother about her age was shot and killed here. “You watch over them and make sure nothing happens.”

Ms. Manasseh, a trained rabbi and mother of two, grew up in this area and today lives in the nearby Bronzeville neighborhood. She remembers a time when parents regularly sat outside on their porches to keep an eye on their kids. Now, it’s not uncommon for youths here to spend the whole summer indoors, with parents fearing for their safety.

In the four summers MASK has been coming to this corner there have been shootings, but only one murder. Beyond being a violence prevention program, however, Manasseh says the mission of MASK is about building resilience and a sense of community in a place that’s often painted as a war zone. Many of the women and men who volunteer with MASK have been impacted by gun violence themselves.

That includes Maria Pike, whose son, Rick, was shot while trying to park his car in a gentrifying neighborhood on Chicago’s West Side in 2012.

“The thing about being a survivor is it doesn’t matter who you are, what color you are, where you live – we all feel the same kind of grief,” says Ms. Pike, who couldn’t sleep through the night for two years after she lost her son. Now, with a man arrested for his murder, her focus is on connecting with other mothers affected by violence. “It doesn’t matter whether your son is on the wrong side of the fence or not, your grief is the same. And in order to have peace here, we have to become a community and we have to join forces with the mothers of the ones who hurt our kids.”

So Pike makes the nine-mile trek south from her home to Englewood as often as she can. Last year, she helped plant a vegetable garden on the lot that produced more than 20 pounds of tomatoes and a seemingly endless supply of lettuce.

“We had salads constantly!” she laughs. “The beautiful thing was people didn’t realize they were connecting with each other [through the garden]. Kids who passed by with their moms would ... check on the tomatoes and Papa King would explain to them how they grow,” she says, referring to a fellow MASK volunteer. “That interaction is so important.”

Last year, MASK gave out book bags and school uniforms to kids who needed them. They are now working with the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago and the city government to build a small permanent community center on the block that would serve the area year-round and provide science, technology, engineering, and math classes to children. MASK has inspired people to form affiliate groups elsewhere in Chicago as well as in Indiana, New York, and Tennessee. But to permanently improve the neighborhood, Manasseh says, they would need help from the city to address the underlying causes of the violence.

“You want the violence to stop. But if we stop it, now what?” she asks. “What can you do for these people in these neighborhoods? You’re closing the schools. They don’t have jobs. They live in a food desert. What are you going to do?”

***

One answer lies in a community center a few miles north of the MASK site. There, a social services agency is trying to give men more choices, men like Terrence Jackson.

Mr. Jackson doesn’t look like someone most at risk for gun violence in Chicago. At 6 feet 5 inches, the Englewood native cuts a gentlemanly form, wearing a maroon shawl-neck cardigan and jeans.

But one of the things that sets this program apart is its use of big data to find the people who most need its services. While police departments, including Chicago’s, use predictive algorithms to find the individuals most likely to commit crimes, this seems to be the first time that nongovernmental organizations have used analytics to connect those individuals to social services.

“Before I got the call about a job at READI [Rapid Employment and Development Initiative], I was nine toes in the street – selling drugs, robbing, [using] guns,” says Jackson. “When you’ve got kids and bills, you resort back to what you know. Because you’ve got to provide for your kids, even though it’s not right.”

READI, launched by the global antipoverty group Heartland Alliance in response to violence here in 2016, enrolls men in an 18-month program of intense cognitive behavioral therapy and supported job training. It also provides them with legal and social services along the way. Studies have shown cognitive behavioral therapy to reduce violent arrest rates, especially when combined with employment training.

The initiative has a $32 million budget for its first two years and works in four communities in Chicago, including Englewood. Organizers hope to connect 500 men to jobs by the spring of 2019. They’re almost halfway there. The participants are mostly African-American and between the ages of 18 and 32. Eighty-one percent have lost a loved one to violence and almost all have been arrested before – 16 times, on average.

Jackson grew up in a single-parent home and started using drugs and getting involved with a gang before he was a teenager. At 10 years old, he was shot in the back. Over the next 17 years he was in and out of jail, mostly for getting into fights and destroying property.

Then, in 2009, Jackson was arrested for committing a series of armed robberies of AutoZones. He says he was trying to get money to buy a present for his son, who was turning 1. He ended up spending eight years in prison.

After he was released last summer, Jackson struggled to find a job. Although he had picked up a few trades while incarcerated, no one wanted to hire someone with a criminal record. Then he was selected for READI.

To be sure, the program faces challenges. Six men selected for READI – including two who had already started working – have been shot since the program started.

While READI is still in its early stages, staff point to positive benchmarks, such as high job attendance, that indicate the program is making a difference. Even participants living out of their car or on friends’ couches are still making it to work regularly.

“I think the program is great,” says Jackson, who now spends three mornings a week in therapy and works part time with the Chicago Park District. “I look at it like, for all the negative I’ve done, I get to give back. We don’t have a lot of good programs in Chicago for us to help us do something great. We have a lot of jails and police stations, but not enough resources.”

***

Progress at reducing gun violence can be painstakingly slow, even with the success of neighborhoods like Englewood. And the progress can be uneven: Even as the city’s overall violence went down over the past two years, the number of children shot in Chicago has remained steady.

Questions also persist about how sustainable the current trend is. The spike in gun violence that Chicago and other places experienced in 2016 came after a long period of decline. Some are concerned that the city’s recent success may be reversed, and point to the violence this past weekend as evidence of just how fragile the peace here is. But for the people most affected by gun violence, even small changes can seem like victories.

Out on the streets of Englewood, Jackson agrees that he and the other men are changing and transforming their neighborhood – and themselves. As part of his job training with the city parks agency, Jackson and a dozen other participants are working their way down Garfield Boulevard on this day picking up trash. As the men walk toward the highway, they joke with each other. Jackson will walk 15 blocks with his crew, a harbinger of peace in and of itself.

“A lot of guys can’t walk from block to block in their neighborhood,” Jackson says, because they can’t cross gang territories. “But here, we walk together.”

New Chicago program targets men most at risk of gun violence

Charlottesville: Lives changed

For these pastors, protest has become an act of faith

United Church of Christ ministers Brittany Caine-Conley and Seth Wispelwey wanted to stand against white supremacists in Charlottesville, Virginia. On August 12th last year, they marched. Then, they say, the really hard work began.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

On Aug. 12, Charlottesville, Va., ministers Brittany Caine-Conley, Seth Wispelwey, and other faith leaders not only marched with local activists, but they also – after the violence started – helped the wounded and calmed the frightened. In the aftermath of that weekend, they began to comprehend the vastness of the task ahead. The pastors faced resistance from members of the faith community who didn’t love the idea of their ministers taking to the streets. They wrestled with complex traumatic experiences that were tangled with faith and race. They also sought to explain to their congregants about why it mattered to stand with communities of color, especially when it was uncomfortable. “We weren’t prepared for how difficult it was going to be afterward, how long the trauma would linger,” Ms. Caine-Conley says. “Every day has felt like Aug. 13 since,” Mr. Wispelwey adds. For both, what happened last summer – and everything that’s come since – has meant a fundamental shift in what they fight for, who they hang out with, and how they’ve oriented their lives. “There’s no going back, having passed through the fire of last year,” Wispelwey says.

For these pastors, protest has become an act of faith

The idea seemed simple enough: Put out a call to faith leaders and clergy across the country, and get them to show up in Charlottesville and stand against white supremacy.

It was the summer of 2017, and white supremacists had already marched on the city twice: First in May, at a torchlight rally led by white nationalist Richard Spencer, and again in July, when the Ku Klux Klan came and held a demonstration that ended in tear gas. The robust local activist community had long begun marshaling their forces, but local ministers Brittany Caine-Conley and Seth Wispelwey – both with the United Church of Christ – saw a glaring gap.

“We didn’t really have a mechanism to mobilize people of faith to show up and do public witness,” says the Rev. Caine-Conley. “[We] weren’t prepared or equipped to show up in the streets or to demonstrate in any capacity.”

From that need came Congregate Charlottesville. Long term, the goal was to create an infrastructure for faith leaders here to organize and to serve as a bridge between the local faith and activist communities. Short term – the weekend of Aug. 12 – they wanted “to keep our community as safe as possible and to claim that white supremacy is evil,” Caine-Conley, who heads the organization, says.

As it turned out, none of it was simple. Congregate Charlottesville built the framework for a local activist clergy, training them in how to respond to conflict and fear. On Aug. 12, they not only marched with local activists. They also – once the violence started – helped the wounded and calmed the frightened.

But the pastors’ founding principles faced resistance from members of the faith community who didn’t love the idea of their ministers taking to the streets. In the aftermath of that weekend, Caine-Conley and the Rev. Wispelwey say they began to comprehend the enormity of the task ahead. They would have to wrestle with complex traumatic experiences that were tangled with faith and race. They also sought to explain to their congregants about why it mattered to stand with communities of color, especially when it was uncomfortable.

“We weren’t prepared for how difficult it was going to be afterward, how long the trauma would linger,” Caine-Conley says.

“Every day has felt like Aug. 13 since,” Wispelwey adds.

The two pastors issued the nationwide call at the end of last July. About 300 responded from as far away as California, Texas, Massachusetts, and Florida. Those who came took part in training sessions that Congregate, alongside local activist groups, had been holding all summer. They learned how to react in conflict situations and avoid arrest, how to keep themselves and their congregations safe, and how to de-escalate crises.

In some ways, Caine-Conley says, what resulted was beautiful: a diverse group of faith leaders turning up to prove they could stand against neo-Nazism and white supremacy. “It was people of color, Muslim and Jewish leaders, a lot of women, a lot of queer leaders,” she says. “Those were the people that showed up and put their bodies on the line.”

Wispelwey, who identifies as a straight, white male, says it changed how he looked at his own role. “The people most often on the receiving end of systemic violence and actual violence are the ones most often showing up to confront it,” he says. “And until that equation changes and more white people embody solidarity and step outside their comfort zones and risk some skin in the game, we’re not going to see the needle move the way it needs to.”

That has led Wispelwey and Caine-Conley to walk increasingly different paths. Caine-Conley has stepped forward as an activist leader, drawing from her experiences as a queer clergywoman. Wispelwey has tried to step back, and instead work to raise the voices and experiences of his colleagues and congregants of color. “It’s high time that we default to white men not calling the shots, period,” he says.

It’s a message that can come with a cost – in Charlottesville and elsewhere. Shortly after the protests, the Rev. Robert W. Lee IV, a young pastor at a church in North Carolina and an indirect descendant of Robert E. Lee, took a stand against racism at MTV’s “Video Music Awards.” Mr. Lee, who appeared alongside the mother of the woman killed during the Aug. 12 riot, urged those in positions of power and privilege to “answer God’s call to confront racism and white supremacy head-on.” He later resigned from his congregation, citing some members’ displeasure with his remarks (an account the church’s governing council disputed).

For both Wispelwey and Caine-Conley, what happened on Aug. 12 – and everything that’s come since – has meant a fundamental shift: in what they fight for, who they hang out with, and how they’ve oriented their lives.

“There’s no going back, having passed through the fire of last year,” Wispelwey says. “When activists of color say, ‘Jump!’ I wanna be there to say, ‘How high?’ ”

“Antiracist organizing here has largely become my life,” Caine-Conley adds. “It’s difficult to be around people who have experienced nothing similar. My community has shifted quite a bit.”

Still, both hope that more people will take what Charlottesville went through and use it as a means to start asking tough questions of themselves and those around them. “White progressives or white people in general can’t just read Ta-Nehisi Coates, read The New York Times, and go, ‘Oh, apparently the police are shooting black men with impunity. I strongly disagree.Next,’ ” Wispelwey says. “It has to be more than just Facebook agreement.”

Staff writer Christa Case Bryant contributed to this report.

[Editor's note: This article originally misstated Brittany Caine-Conley's role at Sojourners United Church of Christ in Charlottesville.]

Part 1: A new life for mother whose daughter was killed in Charlottesville

Part 2: Charlottesville teen goes from targeting statue to taking on system

Coming Thursday: The organizer and the alt-right, a year later

Science meets history: sorting the saga of the first Americans

The story of human history is in many ways one of migration. But that tale isn’t always easy to tell. Sometimes we need science to teach us.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

When it comes to understanding where we come from, a story goes a long way. Scientists weave the tale of human prehistory using data points, but those don't always offer a narrative as clear and linear as we might like. In the case of the peopling of the Americas, for instance, scientists thought they had it all figured out: During the last ice age, humans traveled from Asia into Alaska, then down a corridor between ice sheets to spread across the United States. But subsequent research prompted scientists to look for a new story – perhaps the first Americans followed the Pacific coast instead. Some researchers say we might have been too quick to jump to a rewrite – and that we shouldn’t be so attached to one narrative at all. A paper published today in Science Advances suggests that both models are viable and reminds scientists and science consumers alike that, as Texas State University archaeologist Michael Collins puts it, “We don’t begin to have all the answers. We don’t even have all the questions.”

Science meets history: sorting the saga of the first Americans

You may have learned a story of the peopling of the Americas in grade school. The tale begins near the end of the last ice age with a mass migration across a land bridge from Asia to Alaska From there, the first Americans spread down into North, then South America along an interior corridor that opened up between thick ice sheets that blanketed what is now Canada. Or perhaps the tale included a Pacific coastal route.

But coming up with a single narrative isn’t actually as straightforward as it may seem. Without written records, we need scientific data to teach us our prehistory. And that data doesn’t always fall into one nice, neat, settled narrative.

When it comes to the peopling of the Americas, scientists are increasingly entertaining the possibility that the story might not be so simple – or so simple to sort out.

“This is an extremely complex issue. There’s not going to be any simple model or simple narrative that covers all of the variants that we see in the early peoples of the Americas,” says Michael Collins, an archaeologist at Texas State University in San Marcos.

Decades ago, scientists discovered stone tools in the United States dated to shortly after an ice-free corridor was thought to have opened up. The tools appeared to be about 13,500 years old, and the ice sheet is thought to have opened up about 14,000 to 15,000 years ago. So it was easy to imagine that the people using those tools (dubbed members of the Clovis culture) followed bison or other rich resources down that corridor and then spread across the region below the ice sheets.

“We didn’t know anything earlier,” says Professor Collins. “It was an elegant model, and it seemed to explain everything.”

So when some archaeologists found signs of even earlier human presence south of the ice sheets – even as far south as Chile – many other scientists were skeptical, and some evidence was even dismissed as impossible. But the evidence piled up. And then paleoecologists found evidence that suggested the corridor might not have been enticing, resource-wise, for humans until about 12,600 years ago.

Some scientists began to proclaim that the peopling of the Americas needed a rewrite. Around the same time, the idea emerged that perhaps the first Americans exploited resources like kelp as they migrated along the Pacific coastline, which would explain some pre-Clovis archaeological sites in the region.

But that rewrite might have come too quickly, says Ben Potter, an archaeologist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He and a group of other archaeologists, anthropologists, geneticists, and paleoecologists are working on questions around the peopling of the Americas. Their paper published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances reviews much of the evidence and asserts that there are still many questions to be answered about the Pacific coastal model – and that we may have been too quick to dismiss the ice-free corridor pathway. Neither can be ruled out, they say.

In the paper, they point out that new scientific data has emerged that suggests the corridor might not have been so barren. There were trees there as early as 13,500 years ago, so perhaps the environment was enticing early enough for those early Americans to wander down it after all.

“We’re letting our hypotheses drag us around by the nose,” says Collins, who was not involved in the study. If we get too attached to one of these narratives, he says, it’s difficult to keep an open mind to new data.

Writing a story or painting a picture?

Part of the problem, Collins says, is that this isn’t like laboratory science. Researchers can’t reproduce each other’s work to refute or corroborate it. Instead, it depends how you assemble the data in context, and consider its quality.

Furthermore, human migration isn’t exactly linear. A group of people doesn’t say, “hey, let’s march ourselves halfway across the globe without knowing what’s there.” Instead, explains Professor Potter, “we’re looking at expansions and contractions of people as habitat gets better or worse.”

That idea leaves open the possibility that humans migrated down both proposed pathways. Or perhaps people set out in waves.

It’s more like painting a picture of a moment in time than piecing together a linear narrative, says Amy Gusick, associate curator of anthropology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. All the archaeological and genetic clues must be put into the broader environmental context to understand whether or not a given place could even support people.

“We’re trying to understand broadly this world that these individuals may have gotten into at this particular time,” she says. “We’re just building it piece by piece to understand a much broader issue and a much broader question.”

Part of looking at the broader topic of the peopling of the Americas requires letting go of the attachment to figuring out who was first, Potter says. “That one probably could never be answered.”

Although holding too tightly to narratives can be limiting, narratives do serve a purpose, says Collins. Defining the patterns in the data into a narrative allows for more productive dialogues, he says.

“You build a model and expect it to evolve,” he says. “If you are in the business of making models of human behavior in the past, you cannot expect these to be universally accepted. People are going to challenge aspects of it and change will follow. Sometimes the whole idea will just get dumped.”

“There’s so much more to learn,” says Dr. Gusick. Scientists across disciplines – ecologists, archaeologists, and geneticists – are increasingly looking at the topic to add more data. “All these different kinds of input from so many different kinds of researchers that do so many different kinds of specialties all have their part to play in piecing it together.”

With so much curious data, any story about a prehistoric human expansion is far from written in stone. “We don’t begin to have all the answers,” says Collins. “We don’t even have all the questions.”

The story of the peopling of the Americas is no different. It may never be settled. And that’s what makes it interesting, Gusick says. “One of the great things about science is the continual discovery of things.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Syria needs to be a blueprint for peacemaking

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Syria is a good place to bring fresh thinking about how to build a stable peace. Most of the pro-democracy rebels fighting against Bashar al-Assad’s regime have been defeated. Territory has been retaken from the Islamic State. Now, many powerful nations – including Iran, Turkey, Russia, and Israel – have a stake in what comes next. A political settlement will require opponents with little trust in each other to negotiate when talks brokered by the United Nations begin next month. The dynamics are complex, but one aspect stands out: The West appears willing and able to finance the rebuilding of Syria if there is a political transition that would include a new constitution and elections. Iran and Russia cannot afford the price tag. Yet that rebuilding is necessary to assure the safe return of millions of refugees and keep others from leaving. Negotiators must use the lure of a peaceful, prosperous Syria to win over the players with the biggest stake in its future. For years, Syria has been the world’s biggest war. With fresh thinking about peacemaking, it could be the best example of how to end one.

Syria needs to be a blueprint for peacemaking

One reason that recent wars have lasted so long is that so little remains understood about how to build a stable peace. Half of the world’s current armed conflicts have lasted for more than 20 years. More than half of conflicts that ended in the early 2000s have since relapsed. Reversing this recent record will require a reassessment of past methods aimed at taming mass violence.

A good place to bring fresh thinking is in Syria. Its war is “only” seven years old. Yet the toll in lives (more than 350,000) and displaced civilians (12 million) give it a special urgency. Most of the pro-democracy rebels fighting against a ruthless Assad regime have been defeated. And the territory once occupied by the Islamic State has been retaken. Many powerful nations, such as Iran, Turkey, Russia, and Israel, claim a stake in a post-conflict Syria. For its part, the United States has just reimposed sanctions on Iran in part to get its forces and allies out of Syria as a protection for Israel.

A political settlement in Syria calls for peacemaking on a new order, one that will require opponents with very little trust in each other to negotiate. “There will be times when we have to hold our nose and support dialogue with those who oppose our values, or who may have committed war crimes,” said Alistair Burt, a British Foreign Office minister, in a recent talk about a new government report on ways to end the world’s current conflicts.

A new set of talks on Syria, led by Russia and Staffan de Mistura, the United Nations special envoy for Syria, is slated for September. Given that negotiations since 2015 have failed, these talks must be conducted in a very different way to succeed. The UN envoy hopes to organize democratic elections within two years under the supervision of the UN and somehow bring the country’s Sunni, Shiite, and minorities together as a country again.

The dynamics of Syria are complex but one aspect stands out: The West appears willing and able to finance the rebuilding of the country if there is a political transition from President Bashar al-Assad that would include a new constitution and elections. Iran and Russia can hardly afford the price tag, estimated at some $250 billion, to restore the country. Yet rebuilding is necessary to assure the safe return of millions of refugees – and to prevent them from migrating to Europe.

Negotiators need to use that lure of a peaceful, prosperous Syria to win over the players with the biggest stake in its future. As the British report finds, based on research about 21 recent conflicts, resolving a war must rely on progress in understanding what often drives a country’s warring elites: “perceptions of fear and insecurity and forms of envy, rivalry, hatred, prejudice, solidarity and loyalty.”

Today’s conflicts that can’t seem to end need a new model of peacemaking. For several years, Syria has been the world’s biggest war. Soon, with fresh thinking about peacemaking, it could be the best example of how to end a war.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Trust in a good outcome

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Ingrid Peschke

Far from blind faith or naiveté, understanding the nature of God as our good creator brings hope and practical solutions.

Trust in a good outcome

In today’s climate of volatile news, it can be heartening when a story surfaces that the whole world seems to rally behind. For instance, such unified support was palpable when a Thai soccer team was recently rescued from 18 days of captivity deep within a flooded cave labyrinth.

Despite fearful predictions that the group would be stuck in the cave for months at the mercy of the monsoon season, creative solutions abounded, particularly in the courageous efforts by divers. It truly felt as though everyone near and far – including a diver who lost his life while ensuring those trapped had the oxygen they needed – was working for the complete and safe return of the team and its coach.

I love thinking about the qualities that were expressed along the way, including patience, courage, intelligence, creativity, love, and selflessness. The Scriptures call such qualities the “fruit of the Spirit,” which we each inherently include as God’s creation, or expression. As the New International Version puts it, “The fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Against such things there is no law” (Galatians 5:22, 23).

It can be hard to be patient and faithful when we aren’t sure of an outcome, and yet prayer that acknowledges the goodness of God enables us to trust that the end result will be in accord with good, giving strength and confidence even in the toughest of circumstances. As the King James Version of the Bible assures us, “They that seek the Lord shall not want any good thing” (Psalms 34:10).

From my study of Christian Science, I have come to expect that when we seek guidance from God, the one divine Mind or intelligence, we can expect to receive creative and harmonious answers. Fearful predictions dissolve, replaced with a calm understanding that God’s goodness is always present and available.

My family has had many experiences that have shown us the practicality of this idea of trusting in good. Although these are much more modest than the rescue of the soccer team, they have illustrated to us the spiritual laws that lie behind the affirmation that we can trust goodness to prevail. During a particularly harsh New England winter when we had no break in heavy snowfall, ice dams formed on our roof, eventually leaking into our home. The resulting water damage was significant, and our insurance company and multiple contractors had to be involved in efforts to restore our home.

During this time we heard stories on the news and from neighbors about the scarcity of good contractors and the difficulty of even reaching insurance agents due to the high volume of similar claims throughout our state. My husband and I prayed during each step of the process to replace fear and uncertainty with confidence in Mind’s providence of intelligent solutions.

I considered home as a spiritual idea, rather than focusing on a physical structure that could be negatively impacted by time or weather. As God’s loved spiritual offspring, we each dwell in God’s love, finding in Him a home that is forever intact. The heart of home consists of qualities such as beauty, order, light, warmth, and generosity – qualities we can cherish wherever we are.

These ideas brought me peace amid the destruction and uncertainty. We found that as we sought God’s guidance, each obstacle was met, including a creative solution that allowed us to live in our home while the work was completed. The people we ended up working with expressed kindness and generosity, and our home was satisfactorily restored in a reasonable amount of time.

Such experiences give me hope when addressing life’s challenges, whether individual or global. These words of Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy, inspired by a passage in the Bible, relate to each one of us and continue to inspire my prayers: “How blessed it is to think of you as ‘beneath the shadow of a great rock in a weary land,’ safe in His strength, building on His foundation, and covered from the devourer by divine protection and affection” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 263).

A message of love

The sport of war?

A look ahead

How long should people be held accountable for their questionable social media rants? Tomorrow, Harry Bruinius will examine how we're still working out the rules of a tool that offers instant global reach.