- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In Canada's spat with Saudi Arabia, signs of trickier road for democracies

- For the people of this city, a long year of reckoning

- Buddhism’s Siberian resurgence opens a window on pre-Soviet past

- Lebanon’s complex hashish equation: If farmers gain, who loses?

- Monsters no more? Wide-ranging sharks get a makeover on Cape Cod.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for August 10, 2018

In August in the US Northeast, a middle-aged suburbanite’s fancy turns to tomatoes.

We don’t all need to become experts in microfarming and food preservation. But there’s a deepening awareness that local food is good stuff. A Gallup poll this week showed that a majority of Americans now actively seek it.

That’s not to ignore the stubborn (though eroding) reality of “food deserts” served mostly with processed and plastic-wrapped items. But urban farmers markets and urban farms abound. Many accept SNAP payments. Important elements of the farm bill now moving through Congress address local-food policy.

Big-scale farming, of course, is still about soil-depleting monoculture and sourcing the crops that end up mostly in that processed food. (Or caught in trade-war limbo, as with the 70,000 tons of soybeans now wandering the sea aboard one cargo ship.) But movement is occurring there, too.

In an otherwise sobering report, the food policy site Civil Eats notes that more Iowa farmers are adding oats and other small grains to their rotations. In Indiana, soil-protecting cover crops have become the third most planted crop. Sure, local markets are small. “People just aren't going to gamble with land valued at $2,000 per acre,” economics writer Laurent Belsie reminds me.

But local markets will grow as farm-to-institution efforts grow, feeding schools, hospitals, universities, company cafeterias, and eldercare facilities – sun-warmed local produce finding outlets to match its appeal.

Now to our five stories for your Friday, including a look at Canada’s efforts to find its global role, at Charlottesville’s struggle to find social harmony, at Buddhism’s surprising strength in Siberia, and at scientists’ work to do a little PR for a deep-ocean predator.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In Canada's spat with Saudi Arabia, signs of trickier road for democracies

Canada is trying to fill the human rights leadership gap that the Trump administration has left on the world stage. But it is finding that without US backing, taking the high road comes with a cost.

When Canada’s foreign ministry called in a tweet for the “immediate release” of civil society activists detained by Saudi Arabia, it was not an unusual statement. Canada has made such calls before. But this time it provoked a furious reaction from Riyadh, which accused Ottawa of “blatant interference” in its internal affairs and announced a rash of retaliatory measures, including expelling the Canadian ambassador and halting trade. Many believe the rebuke was intentionally disproportionate, a signal to Western countries not to meddle in Saudi affairs. Other nations have stayed out of the spat, which could signal a new global dynamic in which authoritarians are more willing to defy democracies in the absence of US moral leadership. “If we are entering a global system where not only are authoritarian leaders increasingly bold in their actions [and] the United States is no longer willing to offer the same kind of guarantees as it once did,” says Stephanie Carvin of Carleton University in Ottawa, “that actually means we are going to have to sit down and think pretty hard about how we are going to live in this world.”

In Canada's spat with Saudi Arabia, signs of trickier road for democracies

The furious reaction by Saudi Arabia to what was a rather stock Canadian statement calling for the release of imprisoned human rights activists has little to do with Canada – and everything to do with the ruling agenda of Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman.

Still, the bilateral spat – which has garnered global attention simply for the proportions it has taken – took this country off guard. In doing so, it has raised questions about the price Canada must pay to stand up for its principles on the global stage, which has become a lonelier place as of late.

And despite being cast as the “good” character in the narrative, the Canadian government faces charges of hypocrisy at home, as it asserts its commitment to human rights abroad while continuing to sell arms to the regime. It's a conundrum that many Western nations face, and one reason allies have been so silent in this specific dispute.

Saudis making an example

None of this reflection was expected, when Canada’s foreign ministry called for the “immediate release” of civil society members, including gender-rights activist Samar Badawi, in an Aug. 3 tweet.

Anodyne words by most accounts, Riyadh called them “blatant interference” in its internal affairs and announced a rash of retaliatory measures unless an apology is issued. That includes expelling the Canadian ambassador, halting trade, suspending flights to Toronto, yanking students on scholarship out of universities across the country, and putting a question mark over the continuation of a deal on armored vehicles. For now, oil sales remain unaffected.

Many believe the rebuke was intentionally disproportionate, a signal to other Western countries not to meddle in the internal affairs of the crown prince, known as MBS. Canada is an easy target. While the measures are dramatic for those directly affected – including thousands of students who now must scramble before the start of the school year – the bilateral relationship is relatively narrow. Staking such a position against the European Union would carry much greater risks for Riyadh.

MBS, who in some avenues has been a reformist, has increasingly used authoritarianism to punish domestic critics. Canadian authorities have tried to cool tensions with Riyadh, but say they won’t back down. “Canadians have always expected our government to speak strongly and firmly, clearly and politely, about the need to respect human rights around the world,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Wednesday.

The stance itself is nothing radical or different. Roland Paris, a professor of international affairs at the University of Ottawa and a former advisor to Trudeau, says it only might seem so as others retreat from the stage. “We are living at a time when authoritarianism is on the march and when human rights are being challenged in many parts of the world,” he says, “and continuing Canada’s traditional policy makes it stand out more in that darker world.”

Advocating rights, selling arms

Under that light, however, have surfaced some complex questions for Canada.

Some opinion makers have criticized the government for a political mishap, isolating itself when so much other uncertainty, including negotiations with the US over the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), loom. Others have resurfaced old criticism over a $15-billion (Canadian; $11.5-billion) deal to sell armored vehicles to Saudi Arabia. It was signed under the Conservative government of Stephen Harper, but has remained controversial for the current government. It is unclear if the deal itself will be scrapped – but most analysts say that if it is, it will be ended by the Saudis, not the Canadians.

“[The dispute] has allowed the Canadian government to make statements that Canada always stands up for human rights, and yet there is no suggestion by Canada still that it should not sell billions of dollars worth of light armored vehicles to Saudi Arabia,” says David Webster, an associate professor of history at Bishop’s University in Quebec.

Criticisms of hypocrisy for countries upholding peace and human rights while trading in arms dog other nations too, particularly Germany. And because of the business at stake, Canada is facing a degree of isolation on this dispute, including from the EU. “I don’t think anyone wants to get embroiled in this spat,” says Peter Salisbury, a senior consulting fellow at Chatham House, a British think tank, “which in many ways suggests that what they [Riyadh] are trying to do is working.”

The sense of standing alone has implications for Canada well beyond this specific case, says Stephanie Carvin, an assistant professor of international relations at Carleton University in Ottawa. Some speculate that Saudi Arabia used Canada as an example because it knew the Trump administration wouldn’t push back. “We are going to survive Saudi being angry at us because we don’t have deep relations with the country,” Ms. Carvin says, “but if more countries feel Canada is a convenient example because it is no longer being protected by the United States, that becomes a problem.”

“If we are entering a global system where not only are authoritarian leaders increasingly bold in their actions, and I would include MBS in that category, but also ... the United States is no longer willing to offer the same kind of guarantees as it once did,” she says, “that actually means we are going to have to sit down and think pretty hard about how we are going to live in this world.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Charlottesville: Lives changed

For the people of this city, a long year of reckoning

Reconciliation is a process, not a switch to be thrown. But Charlottesville, like the nation, shows that exposing the roots of a divide is a painful but healthy starting point.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

-

Christa Case Bryant Staff writer

This is the story of what last year’s Unite the Right rally meant to the people of Charlottesville, Va., how it changed their lives and outlooks, and how they’re striving to address the divisions the protests exposed – individually and as a community. “This is a fight you get into and you go 10 toes deep into it, and you can’t let go,” says Tanesha Hudson, a community organizer who is working on a documentary. Zoe Padron, a high school teacher, lost her fear of getting fired and is pushing her mainly white students to consider the different ways racism manifests itself. Charles Weber, a criminal defense attorney and spokesperson for The Monument Fund, is among the plaintiffs in a legal challenge to preserve historical monuments, including the Robert E. Lee statue whose proposed removal precipitated the protests. “As horrible as the experience was, and as violent, and as brutalizing for the people who live in my city,” says city councilman Mike Signer, who was mayor during the rally, “I think that to the extent that the event lifted the veil on the violence at the heart of this marginal political movement … it served a purpose in waking the country up.”

To view our full Charlottesville series, you can click here. Also, former white supremacist Christian Picciolini offers a unique view into how to counter hate. Read our Q&A with him here.

For the people of this city, a long year of reckoning

The best seats are already taken half an hour before the Charlottesville City Council is due to start.

With less than a week to go until Aug. 12, the anniversary of last year’s Unite the Right rally that devolved into violence, the city is braced for a reprise. Residents file in with signs bearing the name of the new African-American mayor, Nikuyah Walker, and her slogan, “Unmask the illusion.” Others say simply, “Transparency.” One woman, in front row, holds one that says, “Punish Nazi’s not residendts” [sic] on one side and “Arrest Kessler” on the other, referring to organizer Jason Kessler.

When Ms. Walker walks in, the crowd claps and cheers. There are scattered boos and hisses when she is followed by her predecessor and fellow city councilmember Mike Signer, who was mayor during last year’s protests and the consequent fallout.

By the time the meeting kicks off with the Pledge of Allegiance, the room is packed. As everyone says, “… liberty and justice for all,” someone says loudly, “All?”

Over the next five hours, residents step up to confront the city council and new police chief, RaShall Brackney, the first African-American woman appointed to the job, with questions about the coming weekend. It’s clear there’s a lot that hasn’t been resolved since last year, especially around accountability.

“They have to do a full thorough investigation of everything that occurred ... and come up with some type of way to move forward,” says Tanesha Hudson, a longtime community organizer who attended the meeting. “We’re nowhere near any type of healing or moving forward.”

The tense meeting at City Hall is in many ways a microcosm of a city still grappling with the fallout from last year’s protests, which exposed fault lines along class and race in this quiet college town – as well as the nation. Even as white activists have sought to become more effective allies in the fight for racial justice, and African-Americans have watched their white neighbors wake up to issues they have long been acquainted with, few are ready to talk about rebuilding or reconciliation.

And while almost universal opposition is expressed to the ideology espoused by the white supremacists and white nationalists who marched into Charlottesville last summer, there are still divisions over the place of free speech and historic monuments in a city and country grappling with its heritage – and its future as a multicultural society.

This is the story of what last year’s rally meant to the people of Charlottesville, how it changed their lives and outlooks, and how they’re striving to address the divisions the protests exposed – individually, and as a community.

“This isn’t a fight you get into for six months, or a year,” says Ms. Hudson, her voice hoarse after staying at City Hall until 12:30 a.m. “This is a fight you get into and you go 10 toes deep into it, and you can’t let go.”

Hudson is working on a documentary, “A Legacy Unbroken,” to tell the city’s untold stories about people of color. Zoe Padron, a high school teacher, has lost her fear of getting fired and is pushing her mainly white students to consider the different ways racism manifests itself – not just interpersonal bigotry, but systemic injustice, too.

Sarah Kenny, the University of Virginia student body president at the time of the protests, wrote her senior thesis on the role of women in the alt-right, and intends to study conflict resolution in graduate school. Newly minted College Republican chairman Robert Andrews, a distant relative of Robert E. Lee, is planning to hold bipartisan dialogs on campus this year.

Charles Weber, a local criminal defense attorney and spokesman for The Monument Fund, is among the plaintiffs in the Fund’s legal challenge to preserve historical monuments – including the statue of Lee whose proposed removal precipitated last year’s protests.

And Mr. Signer, the former mayor, has spent a lot of time reflecting.

“As horrible as the experience was, and as violent, and as brutalizing for the people who live in my city, physically and emotionally,” he says, “I think that to the extent that the event lifted the veil on the violence at the heart of this marginal political movement … it served a purpose in waking the country up.”

Through the eyes of a 4-year-old

Seth Wispelwey’s daughter was 4 when he took her to a Smithsonian exhibit on 50 years since the civil rights movement, and 150 years since the end of slavery in America. The exhibits at her eye level included black children shackled in chains.

Soon after, he recounts, he was taking her to the library in Charlottesville, right next to the park where stands the soaring statue of the Confederate general.

She asked, “Who is that a statue of?”

He told her, “Oh, you remember that war we talked about? The one that ultimately ended up in the ending of slavery? Well, he was a general in that war.”

And she said, “Oh, so he fought for the side that wanted to free all the slaves?”

No, he explained, Virginia was part of the South. “We seceded, so he actually fought for the side that wanted to maintain slavery,” he said.

There was a long pause.

“So why is there a statue then?”

He didn’t have an answer.

“So this is where I don’t get when people are like, ‘Oh, it’s just a statue,’ ” says Mr. Wispelwey, a pastor with the United Church of Christ. “It tells a story, and all you have to do is have the eyes of a 4-year-old or a 5-year-old to understand that … monuments and statues valorize our values.”

It was teenage activist Zyahna Bryant’s petition that led the city council to vote to remove the statues of Lee and fellow Confederate general Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and sparked last summer’s Unite the Right rally.

More than 600 white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and white nationalists converged on Emancipation Park in Charlottesville, along with even larger crowds of counterprotesters. Brawls broke out, and counterprotester Heather Heyer was killed when a protester drove his Dodge Charger into a crowd, and 29 were injured. Two state troopers died in a helicopter crash that is still being investigated.

Mr. Weber and other conservatives in the city say they unequivocally denounce the protesters and their message.

Mr. Andrews, who was part of the College Republicans executive committee that put out a statement ahead of Aug. 12 denouncing the alt-right gathering, was dismayed to see protesters rallying around the statue of his ancestor and namesake, Lee.

“He would not condone any of these individuals’ actions,” he says. “They tried to tie themselves to the statue and it was really wrong.”

“None of us at The Monument Fund supports anything that they do,” agrees Weber, referring to the protesters. “We’re focused on the law.”

Virginia state law makes it illegal “to disturb or interfere with any monuments or memorials so erected.” That applies not just to Confederate memorials, he stresses, but all memorials. He himself is a Vietnam veteran.

“There’s a powerful storyline of how this country came to be,” says Weber, sitting in his quiet Charlottesville law office. “I don’t think telling the full story requires us to throw all that out, any more than I think the quest for better forms of justice requires us to throw out the Constitution.”

‘Worse than anything we were told’

The weekend of Aug. 12, Signer says, was worse than anything he’d had to face before as mayor.

“The government was not aware they would come armed as a militia, with shields, insignias, command structures, and weaponry,” Signer recalls. “That was worse than anything that we were told.“

In the aftermath, the former mayor drew some praise for calling out President Trump for his rhetoric, which Signer said emboldened far-right activists.

But he was castigated when he tweeted, days after the rally, that Charlottesville was “back on our feet, and we’ll be stronger than ever!” The post included a photo of himself jumping in front of an oversized “Love” sign downtown.

“I saw my role as trying to cheerlead for the city and project an upbeat kind of, ‘We’ll be back, better than ever,’ message,” Signer says.“To a lot of folks, and I get that now, it seemed like too much, too soon.”

In December, an independent report on the Charlottesville protests by a former US attorney for Western Virginia, Timothy Heaphy, found considerable fault with city government, particularly the Charlottesville Police Department.

“When violence was most prevalent, CPD commanders pulled officers back to a protected area of the park, where they remained for over an hour as people in the large crowd fought on Market Street,” the report said. It also quoted two close associates of Police Chief Al Thomas as hearing him say, “Let them fight.”

Chief Thomas, the first African-American appointed to the post, denied the comment but resigned.

In January, Signer declined to place himself on the ticket for reelection, instead voting for Ms. Walker, a local activist who was among his critics.

All this happened as Signer, who is Jewish, was facing a slew of anti-Semitic attacks. “Someone sent me a cartoon of Robert E. Lee pushing the green button on a gas chamber with my face Photoshopped on it,” he says.

Signer says he absolutely feels changed after the events of last summer.

“I’ve spent many, many months personally reflecting, praying, trying to listen to critiques more than praise,” he says. “It’s constant work, to make people feel heard in their anger and their disappointment, to not be defensive, to try and gain some wisdom that can help servant leadership in this really tough time.”

Stephen McDowell, a conservative who lives on the outskirts of Charlottesville, sees faith as the answer to that anger and hatred, which he says is the central problem to be addressed.

“If that’s not dealt with, you can never really deal with the problem of racism,” says Mr. McDowell. “I believe the only ultimate way is to give them a change of heart, which only the Christian faith can do.”

Just one episode in long history

The air is still heavy from a thunderstorm when Hudson, the community organizer, shows up at the public library in downtown Charlottesville. Across the street the Lee statue glistens with rain, but Hudson doesn’t want to talk about monuments. She doesn’t want to talk about Jason Kessler or Heather Heyer, though she acknowledges the tragedy of her death. Hudson doesn’t even really want to talk about this weekend: only that she’s still deciding whether to stay in Charlottesville or head to Washington, where Kessler plans to hold Unite The Right 2.

As far Hudson is concerned, last year’s protests were just one episode in a long, ugly history of white supremacy and patriarchy that has kept communities of color and especially the black community “at the bottom of the barrel,” she says. Her fight – to build up black and brown folks in her city – didn’t change on Aug. 12.

If that violence jolts white folks out of their comfort zones, Hudson says, then it did the progressive movement some good.

“I’m not asking any of these white people down here to apologize for the legacy of Thomas Jefferson or slavery or Jim Crow.” She gestures to the folks strolling up and down Main Street, about a block from the library. “What I’m asking white people to do is pay attention to the systems that were built and that they choose to maintain and benefit from.”

Some white progressives here have spent the past year wrestling with that mandate.

As UVA’s student council president, Ms. Kenny’s first instinct was to follow the lead of Signer and then-university president Teresa Sullivan. She issued a statement urging her fellow students to resist engaging the white supremacists’ ideas and stay away from downtown during the protests.

“I definitely received some pushback,” Kenny recalls. “There were some upset students who said, ‘You can’t tell me how to best confront evil.’ ”

She’s since struggled to figure out her role. “One of the biggest weights I felt was to keep the white student body engaged and angry and committed to racial justice … and to make sure that our majority white population didn’t try and just tie a bow on it and walk away,” Kenny says. “So many of our classmates didn’t have that choice.”

Ms. Padron, the high school teacher, has found herself playing a more active part in educating her students about race and privilege. Throughout the school year, her mostly white students came to her with tough questions about institutional racism and their own latent biases. “I’ve always been a gadfly, but last year I upped the ante,” she says.

“People of color are uncomfortable in so many circumstances so many times. There’s no reason somebody who’s white should feel good all the time,” she adds. “And as someone who is coded as white here” – Padron is Jewish, and married to a Hispanic man – “I had privilege I could use and should use.”

“A lot of them are just starting to pay attention,” says Hudson, back in downtown Charlottesville. “It’s like, ‘Hey, I’m over here and I’m black and I’ve been telling you that this is happening and y’all weren’t listening.... But now, you listening.’ ”

Christa Case Bryant contributed from Boston.

Correction: Mike Signer did not step down from the office of mayor. In Charlottesville's form of government, city council selects the mayor from its members.

Part 1: A new life for mother whose daughter was killed in Charlottesville

Part 2: Charlottesville teen goes from targeting statue to taking on system

Part 3: Charlottesville pastors see protest as an act of faith

Part 4: Jason Kessler and the 'alt-right' implosion after Charlottesville

Siberian crossroads

Buddhism’s Siberian resurgence opens a window on pre-Soviet past

This piece, the second of five parts from a region that’s seldom heard from, shows how a diversity of faiths can flourish over time after a yoke is lifted.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

For decades, the only Buddhist structure in Ivolginsky – indeed, anywhere at all in Russia – was a little wooden temple that Joseph Stalin allowed to be built in 1946. But since the fall of communism, Buddhism has experienced a rebirth in Russia, particularly in the ethnically Mongol republic of Buryatia in Siberia, where Ivolginsky is now a kind of Russian Buddhist Vatican. For indigenous Buryats, who have been mostly Buddhist for the past 300 years, the resurgence is part of a complex awakening. Local scholars are exploring the Buryats’ distinctly non-Russian historical and cultural heritage and endeavoring to reconcile it with their identity as modern Russians. “It's only recently that we got the intellectual freedom to explore our past, and understand that our history, our religion, language, and culture make us quite different from Russians,” says Timur Dugarzhapov, editor of New Buryatia, a local journal. “Yet much of what we value, including our window on modern world civilization, we access through Russia and the Russian language. It’s not a dilemma; it’s a process. Nobody sees our future as separate from Russia, but we do need to discover our own roots.”

Buddhism’s Siberian resurgence opens a window on pre-Soviet past

This cluster of wildly eclectic, multicolored pagoda-style temples, rising out of the dusty steppe a few miles south of Ulan-Ude, is something almost unique in a Russian landscape.

It’s a sprawling Buddhist monastery, with a religious university at its core, something like the Vatican of Buddhism in Russia and a living monument to the rapid revival of traditional religions in post-Soviet Russia. Just 30 years ago there was only one little wooden dugan, or temple, in this place: the first – and for a long time, only – one allowed to exist in the entire Soviet Union. Now there are almost 40 temple complexes in Buryatia alone, as the native Mongol-speaking Buryats enthusiastically rediscover their ancestral beliefs.

It’s a development that is encouraged by Moscow, at least for what it regards as indigenous Russian religions. This rapid growth is approved by authorities as a justified revival of one of Russia's four “founding” faiths – Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism.

For ethnic Buryats, the resurgence of Buddhism is part of a more complex awakening, as local scholars explore the Buryats' distinctly non-Russian historical and cultural heritage, and endeavor to reconcile it with their identity as modern-day Russians. Similar processes are unfolding in many of the 22 “ethnic republics” that are part of the little-known tapestry of today’s Russia.

“Tradition is very much in demand among young Buryats these days,” says Timur Dugarzhapov, editor of New Buryatia, a journal of local scholarship. “It's only recently that we got the intellectual freedom to explore our past, and understand that our history, our religion, language, and culture make us quite different from Russians. Yet much of what we value, including our window on modern world civilization, we access through Russia and the Russian language. It’s not a dilemma, it’s a process. Nobody sees our future as separate from Russia, but we do need to discover our own roots.”

Buryat and Russian

Today, there are about 1.5 million Buddhists in Russia, concentrated in three ethnically Mongol republics: Buryatia and Tuva in Siberia, and Kalmykia in the North Caucasus. Indeed in Russia, specific religions are viewed as belonging to a particular population: The various faiths are bureaucratized and integrated into a central government-run council, and they are strictly enjoined not to poach upon each other’s flocks.

It’s a system that is warmly embraced here at Ivolginsky Datsan. The indigenous Buryat population has been mostly Buddhist for the past 300 years. The datsan, or temple complex, is filled with visiting locals, eager to reconnect with their traditional faith. Most seem to know the intricate, clockwise rituals of worship, how to recognize and pay homage to the wide array of icons that line the temples’ walls, and never pass a prayer wheel without spinning it. New and grander temples are under construction. Scores of local young men are training as monks at the university, and there is even a large class of students from Chinese Inner Mongolia.

“Every Buryat is a Buddhist,” says Dymbryl Dashibaldanov, the rector of the datsan's Buddhist University. “The state recognizes our religion. Once it is recognized, it means people need it.”

Buryatia has been ensconced within Russia for around 300 years, and that history has produced an extraordinarily diverse population who seem to get along without any observable tensions. Many of the Soviet-era immigrants to the territory, who came to man new industries, departed in recent decades as factories closed in the wake of the Soviet collapse, leaving mostly the descendants of the pre-Revolutionary population.

Today the republic is home to about 1 million people, divided about evenly between Russians and ethnic Buryats. The Russians are mostly descendants of the militarized Cossacks who arrived in the 17th century to conquer this land – in a colonial-settler expansion roughly analogous to the United States’ spread across North America a bit later – and thousands of Old Believers, religious dissidents exiled here by the czars.

Before the Russians arrived, this land was all part of the vast Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan. Buryats are basically Mongols; they only developed a separate identity after the Russians drew a border between this territory and neighboring Mongolia a few centuries ago. The traditional religion here was Tengrism, a mix of ancestor worship and animism that imputed spiritual being to natural phenomena. Even today, many Buryats loosely practice what they call shamanism, and visibly leave offerings of food, coins, and other little gifts to the natural spirits beside waterfalls, mountains, or the shores of Lake Baikal.

'Where different faiths meet'

Tumultuous changes hit in the early 17th century. “Buddhist missionaries came from the east, Cossacks came from the west,” says Mr. Dugarzhapov. “That shaped what we are today. No faith here is dominant. A lot of people somehow manage to acknowledge them all. We have a saying that you can ‘go to an Orthodox priest in the morning, a Buddhist lama in the afternoon, and a shaman in the evening’ and all will be well.”

The Russians conquered Siberia by subduing the local peoples through violence, an unresolved issue that has seen little attention from Russian historians. But unlike the US, where indigenous peoples were displaced and marginalized, the Russian settlers tended to intermarry with native peoples and to find terms of coexistence with them. The Bolsheviks later created a system of national “autonomous republics,” like Buryatia, which in principle recognized the rights of native peoples, even creating written languages for many who had never had one before.

At the same time, they severely limited political options, pressed everyday life into a Soviet mold, and cracked down hard on all religions. Of the more than 80 Buddhist datsans that existed in 1917, not one survived until Joseph Stalin permitted the small wooden temple to be constructed at Ivolginsky in 1946.

“Buryatia was a religious border zone, where different faiths meet and learn to coexist,” says Boris Bazarov, director of the Institute for Mongolian, Buddhist, and Tibetan Studies in Ulan-Ude, a branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. “Soviet rule was very hard on all of them. It’s only in the post-Soviet period that we’ve seen a real flowering of Buddhist faith in this republic. In this respect, Russia has finally modernized itself.”

Mr. Bazarov says the main challenge for the resurgent Buddhist faith has not been how to get along with the Russian Orthodox Church, but how to deal with the pre-existing shamanist beliefs that many ethnic Buryats still cling to.

“A lot of Buddhist ritual has been adapted to accommodate shamanist rituals,” he says. “It’s been very flexible. It enables people to do things they are used to, like leaving coins and other little offerings, and call it Buddhism.”

Lamas' leadership

It was Tibetan Buddhism that came to Buryatia three centuries ago, and still strongly influences its architecture, beliefs and practices. A wave of popular enthusiasm for the faith took off here when the Dalai Lama visited the republic twice in the early 1990s. But, according to government requirements, Russian Buddhists have their own internally elected religious chief, the Pandido Hambo Lama, who sits on the state-backed Interreligious Council in Moscow. No Russian religion is allowed to recognize any outside authority.

That is a potential political problem, since the influence of the India-based Dalai Lama appears very strong here, and his image is almost ubiquitous in the temples of Buryatia’s datsans. But because of Russian-Chinese rapprochement in recent years, everyone agrees that no future visits of the Dalai Lama to Russia would be permitted. Beijing views the Dalai Lama, who advocates Tibetan self-rule, as a threat to Chinese sovereignty.

Mr. Dashibaldanov, the rector, is philosophical about that.

“The Dalai Lama is our spiritual leader, and what is happening in Tibet today is like what happened to us under the Soviet regime,” he says.

But Buddhists are strictly enjoined not to get involved in politics, he adds. “We live in the time where we find ourselves, and we must accept the realities as they are. The main thing is, we continue with our faith.”

Lebanon’s complex hashish equation: If farmers gain, who loses?

This isn’t the usual tussle over legalizing cannabis. The story in Lebanon touches on questions of poverty, economic development, and the political future of a region where the powerful Islamist group Hezbollah draws recruits.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In Lebanon’s impoverished and lawless northern Bekaa Valley, the cultivation of cannabis has revived after a government-sponsored transition to other crops faltered. Now Lebanon is weighing whether to legalize hashish, the Arabic word local farmers use for the crop. It could help an indebted national economy. But the idea raises a thorny political question. Hezbollah, the country's largest political party, is not as popular as it once was among tribes in the Bekaa. Many in that region believe Hezbollah deliberately keeps the area impoverished in order to keep locals dependent on the Iran-backed party for their social needs. Would legalization provide sufficient income to encourage young men to stay away from Hezbollah? It’s not clear if government-set prices would be high enough to allow that, let alone to improve socioeconomic conditions in the Bekaa. Still, farmers voice some hope along with uncertainty. “As farmers, we do not make much money from hashish,” says one. “It’s the dealers who buy the hashish from us that make all the money. This area is so poor that anything that brings some money to our tables is welcome.”

Lebanon’s complex hashish equation: If farmers gain, who loses?

For generations, residents of the impoverished flat plain of the northern Bekaa Valley have been cultivating cannabis.

The illegal enterprise has earned modest incomes for farmers but immense fortunes for the dealers who buy the cannabis in bulk and export the product to lucrative markets in Europe and the Gulf.

To defend their illicit crops, the fiercely independent Shiite tribes of the northern Bekaa do not hesitate to resort to arms when the Lebanese Army and police arrive with their bulldozers. Even Shiite Hezbollah, the dominant political power in Lebanon, struggles at times to appease the tribes.

But change could be coming to the Bekaa Valley, as the Lebanese government is mulling the advice of McKinsey & Co., a prominent global consulting firm, to legalize the cannabis crop. The aim is to generate much-needed revenues for a national economy that has been ravaged by the effects of the seven-year war in neighboring Syria and the presence on Lebanese soil of more than 1 million Syrian refugees.

The notion of legalizing cannabis cultivation has been considered for many years, but it has gained traction after McKinsey recommended the move in a 1,000-page study on ways to improve the economy of Lebanon, the world’s third-most indebted nation.

Parliamentary Speaker Nabih Berri announced last month that the Lebanese Parliament is drafting a bill to make cannabis legal for medicinal use. And a Lebanese university is proposing to establish a medicinal cannabis research center.

But in the northern Bekaa, news of the potential legalization of cannabis – or hashish as it is known locally (hashish is Arabic for grass) – is garnering mixed reactions.

“Some are for it and others against. Some think the area will become rich, but I don’t think we will benefit,” says Mohammed Hamiyah, a former mayor of the village of Taraya nestled on the hilly western flank of the Bekaa Valley.

Away from the main roads around Taraya, fields of dark green cannabis plants sway in the hot breeze ahead of harvesting, which traditionally occurs around the Eid al-Salib, or Festival of the Cross, in mid-September.

Ali (not his real name), a cannabis farmer who has several outstanding arrest warrants, including one for a vendetta killing, stood in the center of the field and fingered a spiky plant appreciatively.

“As farmers, we do not make much money from hashish. It’s the dealers who buy the hashish from us that make all the money. This area is so poor that anything that brings some money to our tables is welcome,” he says. Like all the cannabis farmers and dealers interviewed, Ali spoke on strict condition of anonymity.

In the distance, the clatter of automatic gunfire was carried on the breeze from nearby wooded hills, signaling that another training session was under way for recruits into the militant Hezbollah organization, which operates numerous military bases in the Bekaa and wields a high level of influence.

During Lebanon’s 1975-1990 civil war, cannabis and poppy plants covered much of the northern Bekaa, generating about $500 million a year and turning some dealers and farmers into multi-millionaires.

But when the war ended in 1991, the Lebanese government and the United Nations Development Program launched a drug eradication initiative in which cannabis cultivation was to be replaced by licit crops. Farmers ceased growing hashish, but only some $17 million in funds materialized out of a pledged $300 million, and the program fizzled out by 2002.

Over the past decade, hashish cultivation has soared, in part because farmers took advantage of repeated political crises that drew the Beirut government’s attention away from the Bekaa Valley.

Tensions with Hezbollah

The area has long had a reputation for disorder and violence. Thousands of residents are wanted by the authorities for shootings, murder, car theft, narcotics and arms trafficking, and currency counterfeiting. In the Bekaa, traditional tribal codes and loyalties trump allegiance to the Lebanese state or political party, and Hezbollah is not immune.

Lately, there has been growing opposition toward Hezbollah from the Shiite tribes, a reflection of a widely held belief here that Hezbollah deliberately keeps the area impoverished in order to keep locals dependent on the Iran-backed party for their employment and social needs.

To be sure, joining Hezbollah has its rewards. A Hezbollah fighter can earn around $600 a month and benefit from the party’s extensive social welfare network of schools, hospitals, and charities.

Yet hundreds of Hezbollah fighters have been killed in Syria since 2013, when the party intervened to protect the regime of President Bashar al-Assad. The roads and village streets around the northern Bekaa are lined with crisply colored portraits of Hezbollah’s recent “martyrs.”

In May, Hezbollah and its allies won a small parliamentary majority in nationwide elections. Although Hezbollah triumphed in the northern Bekaa, many residents chose not to vote or voted for non-Hezbollah candidates in a rare sign of discontent.

Local residents also have blamed Hezbollah for the death two weeks ago of drug dealer Ali Zaid Ismael, described by the local media as “Lebanon’s Escobar,” a reference to deceased Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar. The dealer and seven other people were killed in a bloody gun battle when Lebanese troops sought his arrest.

His death triggered a series of protests against Hezbollah, which was accused of lifting its political cover from Ismael and allowing the army to make the attempted arrest. Videos circulated on social media showing angry Bekaa residents cursing the Hezbollah leadership and burning the party’s flags, a borderline breaking of taboos.

Economic opportunity

“Hezbollah is punishing us for not voting for them in the elections,” says a resident of Hamoudieh, Ismael’s home village. “They are making a big mistake by confronting us.”

Given the level of discontent from the Shiite tribes toward Hezbollah, the legalization of cannabis cultivation could serve as a lure for Hezbollah members to quit the organization and generate an income by growing hashish.

But it remains unclear if cultivating cannabis and selling it to the Lebanese state at a price set by the government would provide sufficient income to encourage young men to stay away from Hezbollah, let alone improve socio-economic conditions in the Bekaa.

Many are pessimistic.

“It’s shameful that they [the government] think all we are good at is growing hashish,” says Mr. Hamiyah, the former mayor. “Let them give us factories and [agricultural] projects so that we can make a living. If every young man in the Bekaa is employed in a factory, no one will join Hezbollah.”

Monsters no more? Wide-ranging sharks get a makeover on Cape Cod.

If you were 12 when “Jaws” was released in 1975, you probably had short-term trouble even immersing in a pool. Scientists have been working ever since to demystify sharks. Understanding can take a bite out of fear.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

If the sight of a shark fin cutting through the water sends chills down your spine, you aren’t alone. Generations of moviegoers have been trained to fear these ocean predators. But in one beach town on Cape Cod that has become a hot spot for great white sharks in recent years, educators are working to counter people’s fears with facts. Visitors to the Chatham Shark Center in Chatham, Mass., learn that shark attacks are extremely rare. Only one person in the Cape Cod region has ever died in a shark attack, in 1936. Marine scientists have worked to debunk the “man-eating” image of sharks for decades. But fears have been persistent, especially among adults whose first introduction to the great white came in the movie “Jaws.” Younger generations, however, have had much different initial encounters with fictional sharks, from the rehabilitated great white Bruce in “Finding Nemo” to the outrageously comical “Sharknado.” And those who have attended education programs are armed with the knowledge that sharks aren’t typically a threat to humans. As 7-year-old Colton Chorey says, “I’m not scared. They only bite people on accident.”

Monsters no more? Wide-ranging sharks get a makeover on Cape Cod.

America’s favorite summertime villain is back on the big screen this weekend in “The Meg,” which tells yet another exaggerated tale about the perils of one of the ocean’s most feared predators – sharks.

But despite decades of negative portrayals in pop culture, perspectives may be shifting for the often misunderstood species, and one Cape Cod town is leading the effort.

Chatham, Mass., a town on the outer elbow of Cape Cod’s arm, has long been a destination for beach-loving tourists. But in recent years, an influx of seals has attracted some new seasonal visitors: great white sharks.

For scientists, the arrival of the great white signals a welcome opportunity to study the notoriously elusive animals in the waters along the East Coast of the United States for the first time. But for many residents and vacationers, the sight of their iconic dorsal fins cutting through the water stokes anxieties seeded long ago in movies like “Jaws.” Educators at the Chatham Shark Center are working to counter those fears with facts.

“Knowledge is power. And I think that there is a fear of what people don’t understand,” says Marianne Long, education director of the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, which runs the Chatham Shark Center. “And so when we’re able to educate them and give them more of a background, it can really help to ease those fears.”

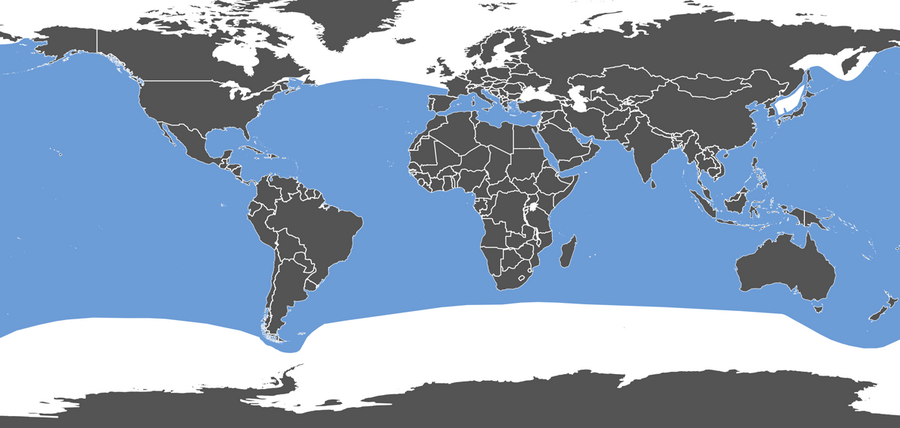

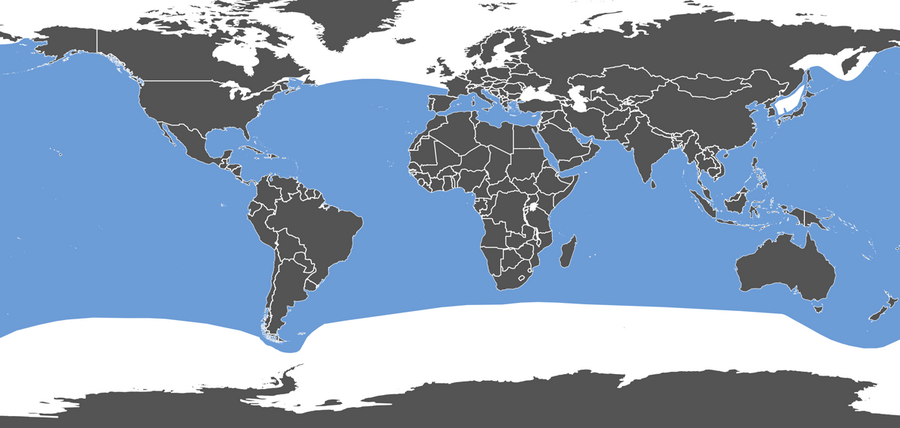

International Union for Conservation of Nature

The reputational rehab appears to be working, as many residents and local business owners have adopted the great white as an unofficial town mascot. Visitors can find shark-related apparel in almost every shop lining Chatham’s Main Street. An art installation called “Sharks in the Park” provides a school of artfully decorated shark cutouts for passersby to admire. And according to Ms. Long, shark ecotourism is thriving.

But still, visitors can be hesitant – the center has received calls from people in support of a “cull,” or an organized killing of sharks to control populations. Culls can actually create more problems says Long, which is why the center is constantly reminding people that the presence of sharks is actually a positive sign of a healthy, biodiverse ecosystem. She and her colleagues also spend a good deal of their time assuring visitors that shark attacks are incredibly rare, especially off the coast of Cape Cod.

The great whites are drawn to the area by the presence of seals, their preferred food source. Scientists believe most shark attacks are actually “test bites.” That’s likely what happened to Cleveland Bigelow in August 2017 when he was stand-up paddleboarding off of Marconi Beach in nearby Wellfleet and a shark took a bite out of his board, knocking him into the water. Mr. Bigelow wasn’t hurt – sharks have taste buds, so once it realized the board wasn’t food, it swam away. His board, with bite mark and all, can be now be observed up close in the Chatham Shark Center.

According to the Global Shark Attack File, there have only been five recorded, unprovoked shark attacks in waters off of Cape Cod dating back to 1800. The only person to ever die from a shark attack in the Cape Cod region was bit in 1936 when swimming off of a beach in Mattapoisett. Globally, there were 88 unprovoked shark attacks in 2017, which scientists say is an average amount.

Marine scientists have worked to dispel the “man-eating” image of a shark for decades. But fears have been persistent, especially among adults whose first introduction to the great white came in the movie “Jaws.”

Younger generations, however, have had much different initial encounters with fictional sharks. Many young children first learn about sharks from Bruce of “Finding Nemo,” a rehabilitated great white with the mantra “Fish are friends, not food!” Young adults today are more likely to have laughed their way through “Sharknado” or have attended an aquarium or shark center educational program by the time they see “Jaws.”

Colton Chorey, 7, visited the Chatham Shark Center with his parents and says he now knows sharks aren’t typically a threat to humans.

“I’m not scared,” says Colton. “They only bite people on accident.”

His mom, Lauren Chorey, says she wants her son to learn more about sharks so that they can have a respect for the animals without having to be constantly afraid while enjoying the ocean on Cape Cod.

“When I grew up [sharks] were villains,” Chorey says. “But attacks are so rare. We shouldn’t be scared.”

International Union for Conservation of Nature

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Paving Mexico’s road to reconciliation

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

He does not take office until Dec. 1. Yet with Mexico’s homicide rate soaring, President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador is not wasting time. He has begun a countrywide listening tour aimed at developing a “national reconciliation pact.” His boldest suggestions include the idea that government should forgive perpetrators who confess their violent acts and commit to not repeat them. Offers of forgiveness have been a common tool in countries caught up in mass violence or emerging from long conflicts, such as Colombia or post-apartheid South Africa. Mr. López Obrador is inviting a debate that includes all points of view and options, from amnesty and drug decriminalization to assuring that the guilty are prosecuted. His advisers stress the importance of supporting victims. They suggest improving police capacities and withdrawing the military from crime fighting. The new president also says he will seek more educational and employment opportunities for youths. None of this will be easy. But, with Mexicans expecting security and other improvements, the new leader has a foundation on which to build. It’s an effort worthy of support.

Paving Mexico’s road to reconciliation

Elected as Mexico’s next president by a wide margin on July 1, Andrés Manuel López Obrador does not take office until Dec. 1. Yet with the homicide rate at a record high, AMLO, as he is known, is not wasting time. In August, he launched a countrywide listening tour aimed at developing a “national reconciliation pact.”

His boldest suggestions include the idea that government should forgive perpetrators who confess their violent acts and commit to not repeat them. It’s part of a broad effort to reform institutions and create new options for youth, including those already seduced by crime.

“You cannot confront violence with violence,” said the president-elect at one “peace forum,” adding, “I respect the people who say don’t forgive or forget. I say, forgive, but don’t forget.”

Offers of official forgiveness have become a common tool in several countries caught up in mass violence, such as Colombia’s war with Marxist rebels, or countries coming out of a long conflict, such as post-apartheid South Africa. AMLO stresses the need for citizens – of every country – to help create the conditions for peace and ensure that the tragedies of recent years are ended and not repeated.

Improving public security, providing justice, and restoring social peace are at the top of his “to do” list. The president-elect hopes the public listening sessions over the next two months will start a healing process. It may also fuel the corrections needed in a country where his election reflected a deep loss of public confidence in the government’s ability to handle violence and corruption.

Since 2014, violent homicides in Mexico have risen steadily. Last year, they reached the highest totals ever recorded (more than 29,000 killed). And over the past decade, more than 35,000 people have vanished, presumably victims of criminal or corrupt officials.

Rising crime has overwhelmed and undermined law enforcement and justice institutions. In the past three years, crime has spread more widely around Mexico. No longer dominated by large drug cartels, crime became “democratized” to smaller, local gangs carrying out a variety of criminal activities, including stealing gasoline from pipelines. Simultaneously, Mexico’s justice system continued to produce very few convictions, despite efforts at reform. Law enforcement institutions are perceived as corrupt and ineffective. According to a 2017 poll, some 76 percent of Mexicans feel unsafe.

During the election campaign, AMLO was vague about how he would deal with these challenges, at one point mentioning “amnesty,” which set off alarm bells about dealing with drug capos and brutal killers. Now he hopes to develop specific proposals with the help of the discussion sessions. He is inviting a full debate that includes all points of view and options, from amnesty and drug decriminalization to ensuring that the guilty are prosecuted.

His advisers stress the importance of supporting victims, including funds to help them and perhaps establishing truth commissions to uncover past wrongs. They suggest radical restructuring the current security model, which mainly relies on police and military forces, to one that improves police capacities and gradually withdraws the armed forces from crime fighting. AMLO also seeks to strengthen justice institutions and cut off cartel finances.

In addition, he proposes more educational and employment opportunities for youths, notably those embedded in low-level criminal activities such as being a gang lookout. The idea is to reinsert them into society, educating rather than punishing them.

None of this will be easy. It will take new laws, new funds, wise policy choices, and a persistent effort to forge new social attitudes. But, with some 65 percent of Mexicans currently expecting security and other improvements under his presidency, AMLO has a good foundation on which to build. It is an effort worthy of support.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

How can I learn to love myself?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Lizzie Witney

Today’s contributor learned to love herself when she took seriously the idea that God was loving her.

How can I learn to love myself?

I remember sitting in my bedroom asking myself, “How can I learn to love myself?” There was a time when I compared myself regularly to my friends and wished I could be as pretty, funny, or interesting as they were. There wasn’t much I loved about myself; instead, I was constantly thinking of everything I should do better. I wanted to express more love, integrity, and selflessness, among other things. It’s not that I hadn’t tried to, but forcing myself to be a better person wasn’t sustainable. I’d slip up – and then be left feeling frustrated and hopeless.

As a Christian Scientist, I’m used to praying about tough things in my life. And in the past, I’d prayed about so many other issues and had great healings – of illnesses, relationship problems, and even character traits that needed to be overcome. But I’d been reluctant to pray about this. It seemed selfish to ask God to show me how I could love myself, and I was afraid that even if I did ask, I wouldn’t get an answer.

Sitting in my bedroom that afternoon at a particularly low point, I realized that I couldn’t keep going through this cycle of negativity. So I gathered up the courage to reach out to God.

The first thing that occurred to me was that none of those negative thoughts could be coming from God, who is supreme and infinite Love, so they couldn’t have any power or truth to them. We have the courage not to accept or believe a lie. What should we be listening to and believing instead? This verse from the Bible gave me direction: “Trust in the Lord with all thine heart; and lean not unto thine own understanding” (Proverbs 3:5). I made a conscious decision to wholeheartedly trust God and to reject any thoughts that weren’t from Him.

Another idea in a favorite book – “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science – helped me get a better understanding of how I should see myself. It says, “If there ever was a moment when man did not express the divine perfection, then there was a moment when man did not express God, and consequently a time when Deity was unexpressed – that is, without entity” (p. 470).

Our very purpose for existing is to express God. Not as mortals, separate from God, struggling to be better. Rather, we are the creation of God, divine Spirit – meaning we inherently express His lovely attributes, such as joy, beauty, creativity, and love. God expresses all His goodness equally in everyone – and loves each of us. So rather than comparing ourselves to others, we can be grateful for their expression of these wonderful qualities, because it shows that we can express God in this way also.

Loving God means loving His creation, too, and that includes ourselves. We have a right to love ourselves as He created us. This is far from arrogant, because it involves acknowledging God as the source of all good.

These ideas completely transformed my concept of myself, and I felt genuine love for myself. I can’t say that since then I haven’t occasionally had feelings of doubt or inadequacy. But when I do, I remember this experience and remind myself that I have plenty of good to share because I reflect God.

In the Bible, when someone addressed Christ Jesus as “Good Master,” he replied, “Why callest thou me good? there is none good but one, that is, God” (Matthew 19:16, 17). This wasn’t a self-deprecating statement; Jesus was acknowledging that all the good he embodied was an expression of God. This is true for each of us, too. In the expression of God that you and I truly are, what’s not to love?

Adapted from an article published in the Q&A series of the Christian Science Sentinel’s online TeenConnect section, July 3, 2018.

A message of love

Washing up, worldwide

A look ahead

Have a great weekend. On Monday we’ll have a report from Zimbabwe, where the growth of mobile money is taking the edge off the country’s latest cash crisis.