- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- For survivors of priest child sex abuse, what would real justice look like?

- Russia’s joint war games send signal to West. Perhaps not the one it intends.

- What the Affordable Care Act has really meant for insurance shoppers

- In Jordan, ‘house of safety’ offers hope and freedom to at-risk women

- At the Ig Nobel Prize awards, science meets silliness

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Amid fires and hurricanes, the power of poise

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

If you click on this link, you will see a map of the area around Lawrence, Mass., Thursday night. Each one of the dots in the constellation denotes a report that a house was leaking gas, was on fire, or had exploded. There were more than 60. It looks like a war zone. And the first responders called to the scene said it felt like exactly that. The massive gas leak was “something that I’ve never experienced in my fire service career, and hopefully I don’t have to experience it ever again,” said one local fire chief.

Yet the responders flooded in – from towns next door and across the region. And as our Clay Collins (who lives not far away) listened to the response on a scanner app, he was struck by “that reassuringly calm choreography we’re accustomed to hearing” – whether it was 9/11 or the California fires. When the crew on a truck from neighboring Topsfield that had been standing by for hours asked to be spelled, “relief was dispatched immediately,” he notes.

Staff writer Patrik Jonsson has seen the same thing covering multiple hurricanes. And he’s getting a glimpse within his own family. His wife is training to become a volunteer firefighter, and one lesson they learn, he says, is “walk, don’t run.”

This weekend in the Carolinas, the wind and water will also unleash a different force: poise. “ 'Balletic' is a good word,” Patrik adds. “Grace amid chaos is how I've seen it play out in real-time situations.”

Now, here are our five stories for the day, which explore how thought is shifting in massive war games in Russia and in an idyllic house for Muslim women in Jordan. And we also invite you to explore for yourself how well Obamacare is working.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

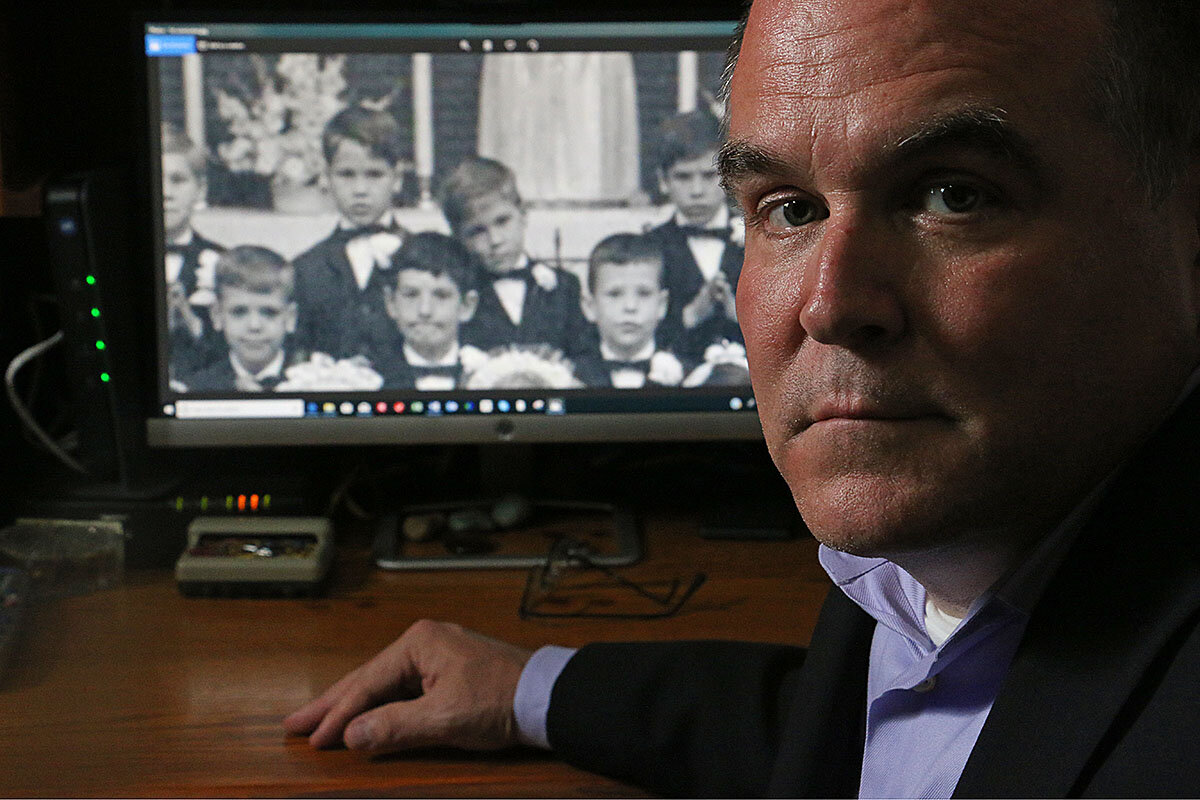

For survivors of priest child sex abuse, what would real justice look like?

The question overlays every detailing of the sexual abuse of children by trusted spiritual figures: How can there be justice for such a crime? We asked several of those now-grown children what, exactly, ‘justice’ would mean for them.

As states grapple anew with the parameters of justice for childhood sexual abuse by priests or ministers, four survivors shared their stories with the Monitor. They describe how, as adults, each of them began a journey to seek the kind of justice they were longing for, often in very different ways. Survivors have begun to coalesce around a number of concrete reforms to reshape the structures of justice: Eliminate statutes of limitations; establish free-standing grand juries with the power to subpoena documents from church archives; and require that all credible accusations of abuse are reported to police. “As a survivor, the biggest, most important part of justice is to be heard, and to be believed,” says Michael Norris, who was abused by a Roman Catholic priest at summer camp when he was 10. Mr. Norris was able to experience two facets of justice that many survivors say they long to see. He confronted his abuser, first face to face, then in a court of law – which found the priest guilty and sentenced him to prison. But the court became another ordeal. “That’s not necessarily justice,” Norris says of his experiences on the stand. “But justice is knowing that this man can’t hurt anybody. He’s in a place now where he’s not going to hurt anyone. And so that’s been justice for me.” Part 1 of 2.

For survivors of priest child sex abuse, what would real justice look like?

There are crimes for which justice can seem like a remote concept.

There are crimes, like the sexual abuse of children, from which many turn away – using language like “unspeakable,” “unimaginable,” or even “inhuman.” Even survivors create their mental shields from the crimes they endured.

“This form of abuse is really completely and utterly spiritually annihilating,” says Christa Brown, a survivor of abuse at the hands of a Baptist minister decades ago, and an author who now lives in Colorado. “It's been called ‘soul murder,’ and I think that's a very apt word for it.”

How can there be justice for such a crime? And what, exactly, would justice look like to those who, more and more, are finding the will, and perhaps the words, to define it?

“As a survivor, the biggest, most important part of justice is to be heard, and to be believed,” says Michael Norris, a chemical engineer and manager in Houston, who was abused by a Roman Catholic priest while attending summer camp when he was 10.

“To me, there’s healing, and then there’s justice,” says Becky Ianni, a mother of four who was sexually assaulted by a young parish priest, in her own home and for years, starting when she was 8.

“To me justice is being able to file a police report and put your perpetrator in jail,” she says. “That's the ultimate justice.”

Ms. Brown, Mr. Norris, and Ianni were three of a number of survivors who shared their stories with the Monitor. They described the swirl of trauma, self-loathing, and guilt with which they’d lived. They described how, as adults, each broke their silence and gave voice to the now-speakable wrongs they endured. There are similarities, but each of them began a journey to seek the kind of justice they were longing for, often in very different ways.

The nation’s institutions of criminal justice are grappling anew with the parameters of justice – and moving in unprecedented ways nearly two decades after the Boston Globe exposed the sexual abuse of children in the Catholic Church, and the lengths its hierarchy went to cover up these crimes.

- In August, a grand jury in Pennsylvania detailed more than 1,000 documented victims. It said that there were most likely thousands more. It publicly named more than 300 priests as abusers. But because of existing statutes of limitations, only two could be brought to justice.

- In September, officials in at least seven states, including New York, Florida, and Illinois, announced investigations into Catholic dioceses, seeking what some attorneys general called the church’s "secret archives."

- Over the past year, evangelical Protestants also have grappled with stories of abusive ministers targeting underage teenage girls, as well as other instances of child abuse. Because of these and other #MeToo stories, the Southern Baptist Convention, the nation’s largest Protestant denomination, launched a study group in July “to consider how Southern Baptists at every level can take discernable action to respond swiftly and compassionately to incidents of abuse.”

“I guess what finally underlies all forms of justice is truth,” says Brown, who advocates listed as one of 14 people the Southern Baptist Study group should consult. “The need for truth within all these processes, within all these systems, within all these faith communities – and especially the need for truth within our very souls and our hearts – certainly that's what survivors need and yearn for to a large degree.”

Survivors and their advocates, in fact, have begun to coalesce around a number of concrete institutional reforms to reshape the structures of justice. These include: Eliminate statutes of limitations for accusations of child abuse; establish free-standing grand juries throughout the states, each with the power to subpoena documents from church archives; and require that all credible accusations of abuse are reported to the police.

Not every victim finds a voice. But for many who have chosen to share their childhood abuse, justice has become more than the difficult journey through human bureaucracies in both the church and law enforcement.

Part of the idea of justice is recompense for what has been lost. But how do you begin to restore lost community and even lost faith?

“When you are abused and you lose your faith community, it’s another loss,” says Ianni, still struggling to recover her faith, and especially her trust in God. “When people are abused outside of religious settings, they might be able to turn to that. So then, when you're abused in that religious setting, what do you do?”

It is a question that most survivors, often in very different ways, are still struggling to answer. Brown describes justice as an ever-moving process.

“But as abuse survivors, we can still work within our very selves to bring about a form of justice, a justice within our own bodies, a justice over the portion that we ourselves have any possibility of exercising some control over,” says Brown, who has embraced the meditative solace of yoga and hiking the Rocky Mountains that surround her.

“And that's not whole justice, that’s not complete justice – it doesn’t do anything about the perpetrators and the enablers and the community that would rather look away,” she continues. “But working within ourselves, we can arrive at some place of peace and wholeness and go on and have a good life – and that really is the ultimate form of justice.”

***

Norris was able to experience two facets of justice that many survivors say they long to see.

Norris confronted his abuser, first face to face, then in a court of law – a court that found the priest guilty and sentenced him to prison.

As the grand jury lamented, existing statutes of limitations have prevented law enforcement officials from pursuing criminal charges against most priests. In states like New York, victims of many forms of childhood sexual abuse have only until they turn 23 to make an accusation, and until 21 to file for civil damages, according to a state-by-state report of statutes of limitations by the advocacy group Child USA.

By contrast, states such as Alabama, Colorado, Illinois, South Carolina, and West Virginia have no statutes of limitations for sex abuse crimes – a reform that survivors and their advocates have begun to demand from other state legislatures. Kentucky, the jurisdiction that sentenced Norris’s abuser, eliminated statutes of limitations for all forms of child sex abuse in 1974.

In recounting his story again and again – to church officials, to the police, to prosecutors, to defense attorneys, on the witness stand, at appeals hearings, and now at parole board hearings – Norris says the criminal justice system became yet another ordeal.

He has been subjected to attacks on his character: “He was starved for attention,” his abuser’s defense attorney said at the trial. “He’s gotten plenty out of this.”

“That’s not necessarily justice,” Norris says of his experiences in criminal court. “But justice is knowing that this man can’t hurt anybody. He's in a place now where he's not going to hurt anyone. And so that’s been justice for me.”

Norris was abused at a summer camp in Kentucky in 1973, after he got poison ivy during a hike. He was sent to the first aid cabin, and one of the camp administrators, Father Joseph Hemmerle, was supposed to give him treatment and care.

He never forgot the episode. In fact, in the years to come, his life seemed to constantly orbit the priest, a beloved religious leader in the Louisville community – which included his parents, who would often gush about him, he says. When Norris enrolled in his local Catholic high school, Hemmerle was his religion teacher.

He began to drink heavily, and “I was also getting high on pot every day,” he says. And then one day in class, when Norris and another boy were talking during a lecture, his abuser mocked him. “He says, ‘Norris, you’re trouble. You’re just going to end up in prison someday,’” he says.

Norris dropped out. Later, he attempted suicide. He enrolled in another high school, but dropped out again. His parents finally told him he had to get a job, go to school, or leave the house.

Instead he joined the Navy, Norris says. He attended the University of Louisville and got a degree in chemical engineering and got married. After they moved to Houston, his wife was the first person he ever told about his abuse.

It wasn’t easy going back to Kentucky to visit his family. “Every time I would go home, my mother would talk about him. ‘Oh, I saw Father Hemmerle. He’s such a good guy. He remembers you, too!’ ” Norris says. “My wife would say, ‘You need to say something to her.’ But I didn’t know how to do it.”

In 1996, after his mother again starting gushing, Norris finally just blurted out, “Mom, he’s a pedophile.”

“She didn’t know what to say, she was so taken aback,” he says. “Then she asked me what happened, and I told her. And she said she loved me. My mother at that point said, you need to do something about it, but I just wasn’t ready. I didn’t know how to handle it. I was still abusing alcohol heavily, my career wasn’t really where I thought it should be.”

But his mother’s support meant the world, he says. He began to see a therapist. “That little boy was still hurting down there, and I never really dealt with it." It took years, “but I finally reached a point, I can actually tell the story of what happened to me, without getting emotional,” he says. “I did nothing wrong. I learned how to deal with it in a constructive manner.”

This included a momentous decision. He would report his abuse, nearly 25 years after the fact, to church officials. He wrote a letter in 2001 to the diocese in Louisville, formally accusing Father Hemmerle and requesting that he be removed from ministry. He met with the local bishop, but in the end, no action was taken.

Then came the Globe’s bombshell reports. Norris decided to report his abuse to the police. Again, not enough evidence could be found to charge the priest.

“Finally, I reached a point – you know, I’ve done what I can do,” Norris says. “My hands are clean. There’s nothing I can really say.”

But the death of his father prompted Norris to confront Hemmerle face to face. On his father’s death bed, “I sat down and I’m by myself with him, and he says to me, ‘I want to tell you I'm sorry. I’m sorry that I allowed you to be put in that situation.’ ”

“And you know, I had no idea that my father was feeling guilty about this,” Norris says, choking back his tears. “So, that was the last conversation I had with my father, a conversation about this priest.”

A year later, he drove to the rectory where Hemmerle lived.

“I walk up to the door and knock on it,” Norris says. “He comes out, opens the door, and he says hello. He has a smile on his face. And I said, ‘I’m Michael Norris.’ ”

Hemmerle’s smile quickly turned to fear. “He was scared. But he looked at me and he could tell I wasn't there to do anything violent. And he looked at me, and said, ‘I, I know who you are.’ He let me walk in, saying, ‘I didn’t do this, I didn’t do this.’ I told him, ‘I know what happened, and you know what happened. But that’s not why I’m here.’”

“I just wanted him to know that I persevered. I persevered,” Norris says. “You know, he abused me, and I felt the impact of that for 40 years, but I’m OK now. I’m a productive member of society. And I wanted him to know that. It was part of a healing process.”

“I told him the story of my father, and the impact of what he had done to me, how it impacted my whole family, and that he needed to understand that,” he says.

“I felt so relieved when I walked out of there. That you know, I felt like I had unloaded all the pain that I had, and that he knew about what had happened to me,” Norris continues.

Almost a decade later, their orbits crossed again. Another person accused Hemmerle of abuse, and the police re-opened their investigation into Norris’s accusations.

This time, prosecutors subpoenaed church documents – an effort other states are beginning to take. These documents included the Catholic diocese's own psychiatric evaluation of Hemmerle. The evaluation corroborated Norris’s accusations. Armed with this report, prosecutors convinced a jury to convict the priest and send him to prison.

Advocates say that this is the reason states like New York have begun to subpoena such documents in church archives.

Norris has refused any monetary damages. And he says that he forgave Hemmerle years ago.

Yet he cannot bring himself to step foot again in a Catholic Church, he says, or sit through a liturgy. “I told my mother I won’t go to her funeral, I refuse,” Norris says, remembering icy stares he received during his father's funeral liturgy. “I’m sorry, I’m not going to put myself in that place again.”

***

Unlike Norris, Becky Ianni, the mother of four in Virginia, was never able to confront the priest who abused her when she was a girl, or see him brought to justice in a court of law.

It’s been more than 12 years, since she first stepped forward to break decades of silence. She had forgotten the abuse she endured as a child until a moment in 2006, when a photo of the priest opened a hidden place and memories flooded over her.

By this time, her diocese in Arlington, Va., had already instituted reforms, and she didn't wait long to contact the diocese’s victim assistance coordinator. She told her she was asking for three simple things.

“I need the church to say they’re sorry, and I need them to tell me I’m not going to hell – because I still felt like, if I'm going to tell on the priest, then I’m going to hell,” Ianni says. “And then I need them to do something about it, and acknowledge what happened to me.”

For the next 18 months, there were bureaucratic disputes about which diocese had jurisdiction over her case. Church leaders ignored her numerous letters and phone calls, and seemed indifferent when she recounted her story again and again. “You know, I just poured out my heart to you, and that’s how you treat me?” Ianni says.

In the late 1960s, when she was 8, a charismatic young priest, Father William Reinecke, came to her family’s parish in Alexandria, Va. He played football on the streets with the neighborhood boys. “And he sort of adopted our family,” Ianni says. He ate dinner at their house two to three times a week. He drove her older brother, an altar boy, back and forth from liturgies. The priest even helped the family buy a new color TV, she says.

“As an 8-year-old, I wanted his attention, too,” Ianni says. “But he took that adoration and began.…” Her voice trails off. “He would abuse me, literally abuse me in the basement of my house, and then go up and have dinner with my family.”

“I thought I had done something wrong, or that I had more ‘original sin’ than other people, and though I didn’t know why, I knew it was my fault. I thought I was being punished by God because I was a bad little girl,” Ianni says.

As she grew up, Ianni says she pushed these memories to the outer peripheries of her conscious self.

Reineke climbed the ranks, becoming a monsignor and the chancellor of the Diocese of Arlington, Va. One of his duties during his 13-year tenure: investigating claims of child abuse.

Ianni got a degree in elementary education from the College of William and Mary. She met her husband Dan, and they had four children. They attended mass regularly and they raised their children in the faith. “But I never felt I was lovable, really, and saying no was just not part of my vocabulary,” she says.

In 1992, a number of people began to step forward to accuse Monsignor Reinecke of abusing them. That September, after a former altar boy confronted Reinecke face to face, he used a shotgun to take his own life.

Neither her abuser’s well-publicized suicide nor the explosive revelations by the Boston Globe in 2002 sparked Ianni's memories. In 2006, however, one of her sons was struggling with alcoholism and she entered family counseling. The therapist asked the mother of four, then 48, to explore her own formative years.

That included looking through photos – including one of a little girl, standing with a young, handsome priest. Suddenly, and with a force that nearly took her breath away, moments started flooding back into her mind. A malaise of guilt and fear and confusion – it was like becoming that 8-year-old girl again, she says – took hold of her.

“I was in a state, not knowing what to do,” Ianni says. "But I wanted to find other victims, other survivors, I knew that.”

After nearly two years of delays, a church panel finally judged Ianni’s accusations credible. But in their first letter of apology, they used vague and euphemistic language, she says.

“The first letter of apology I got – I still have it – what it said was, ‘We're sorry for the experience you had with a priest in our diocese,’” she says. She immediately sent it back.

“I think the church has failed in this, because they’ll say, oh this happened to you, and they use the term 'inappropriate behavior’ or other euphemisms,” she says. “And someone actually said to me, the priest was just ‘overly affectionate.’ These are sexual crimes. And so I think that, to give victims justice, you first need to acknowledge what happened to them.”

In their second letter, the church officially apologized for the sexual abuse she experienced, and at the hands of Reinecke. They also published an announcement in the Arlington Herald. Even more gratifying, the church announced its findings of the former chancellor's abuse in every Sunday bulletin in churches throughout the diocese.

“That’s what I wanted, and so for me, that was my justice,” says Ianni, who also received a small cash settlement. “And quite honestly, if they had simply done those three things right away, I’d probably still be Catholic.”

“I’m not sure how much I trust God yet, if that makes sense,” she says. “But I would like to.” Church officials never addressed her anxieties about hell, however. “I definitely miss God, and I’m trying to figure out a way to get back there.”

But the journey she’s taken since those memories of her abuse came flooding back 12 years ago has changed her pretty profoundly, she says.

She’s no longer so meek, and she’s become an active leader in a different community, the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, an organization Norris also joined.

Ianni has been on the front lines of pressuring church officials to be more transparent. And she has found a sense of meaning as she shares her own story of survival, within a new community that embraces her, without conditions or judgments.

“It’s almost like the Catholic Church created what I am right now,” says Ianni. “And in a way, I’m not sorry for that.”

Correction: Christa Brown was one of 14 people advocates say the Southern Baptist Study group should consult.

Russia’s joint war games send signal to West. Perhaps not the one it intends.

War games are often about bluster, and the current massive joint military exercises between Russia and China are no different. Yet in subtler ways, they might also hint at how the US is compelling each to consider the other anew.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

On paper at least, the joint Sino-Russian Vostok 2018 war games now under way look impressive. Though they fit into Russia's regular schedule of annual military drills, nothing on this scale has been attempted since Soviet times. Moscow claims that 300,000 troops will take part, along with 36,000 military vehicles. That's bigger than the armed forces of most countries in the world. The exercises have led some Russian commentators to suggest hopefully that Russia and China might be edging toward a full-blown military alliance. But analysts warn that talk of a military alliance between Russia and China is very premature at best. “Nobody actually conducts military exercises of this sort anymore. They are a cold war vestige,” says Alexander Golts, an independent military expert. “But the idea of Russian military resurgence is the only card Putin has to play in his confrontation with the West.” More fundamentally, experts add, neither Russia nor China has any interest in creating a formal military alliance with the reciprocal obligations that would entail. Both have repeatedly rejected the idea and insisted that the present relationship – which they describe as a “strategic partnership” – is quite enough.

Russia’s joint war games send signal to West. Perhaps not the one it intends.

They are the most massive war games in Russia since the height of the cold war. And the Vostok 2018 exercises, now underway in Russia's Far East, demonstrate an unprecedented level of Sino-Russian geopolitical unity.

The exercises, kicked off this week by Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping at a summit in Vladivostok, have led some Russian commentators to suggest hopefully – echoed, fearfully, by some in the West – that the two giants might be edging toward a full-blown military alliance. The war games include Chinese troops working with Russians, and a small contingent of Mongolians, in a multi-nation war scenario.

“The message here is clearly directed at Washington. US policies, such as trade war, have encouraged China to seek closer cooperation with Russia,” says Sergei Lukonin, a Far East expert with the official Institute of World Economy and International Relations in Moscow. “As for Russia, if it were not for the collective pressures like sanctions from the West – the US in the first place – things might have developed very differently. But with all these pressures on both countries, the idea of growing strategic cooperation with China has become rather popular.”

But others say that the exercises are less portentous than they appear – and not as large as they have been described. While Sino-Russian cooperation is increasing, they say that a formal alliance is not in the cards. The games are rather a calculated message to warn the United States away from the East Asian region.

On paper at least, the joint war games now under way look impressive. Though they fit into Russia's regular schedule of annual military drills, nothing on this scale has been attempted since Soviet times. Moscow claims that 300,000 troops will take part, along with 36,000 military vehicles including more than 1,000 tanks, about 1,000 aircraft, and 80 warships. That's bigger than the armed forces of most countries in the world.

And although Russian and Chinese forces have exercised before in multi-national drills, mostly under the auspices of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the inclusion of 3,200 Chinese troops, along with 30 aircraft, into the scope of regular Russian-run maneuvers is something quite new.

“The participation of Chinese forces alongside Russian ones is a clear signal to the would-be hegemon that it will not split our two countries, pit us one against the other, in this region,” says Viktor Litovkin, military editor for the state ITAR-Tass news agency. “We may not be allies, but this kind of cooperation is developing very fast.”

The new level of military coordination is mirrored by robust economic developments between the two countries. Bilateral trade and Chinese investment in Russia are both growing at a rapid clip. Russia is already China's largest oil supplier, and is set to become its biggest source of natural gas when the new 2,000-mile Power of Siberia pipeline into the Chinese industrial heartland is completed next year. As China seeks to evade US tariffs on agricultural goods, it is eying the Russian Far East's vast tracts of under-utilized farmland and already making a few long-term leasing arrangements.

But analysts warn that talk of military alliance between Russia and China is very premature, at best.

“Nobody actually conducts military exercises of this sort anymore. They are a cold war vestige,” says Alexander Golts, an independent military expert. “But the idea of Russian military resurgence is the only card Putin has to play in his confrontation with the West. So our generals are doing their best to provide this card, to show that we can conduct such war games on that huge old cold war level.”

However impressive the Vostok 2018 drills may look on TV, they likely contain a strong element of fiction, Mr. Golts and other experts say.

“For one thing, they say 300,000 military personnel are involved, but that exceeds the total number of Russian ground troops, which is about 280,000,” says Golts. “The number of vehicles and tanks said to be taking part is very hard to believe. There certainly aren't that many armored vehicles in Siberia and the Far East, and if they brought them in from the west, it would have tied up the single rail line to the Far East for weeks. It would also have denuded our defenses in the west. When you count up everything, there is no way it adds up to what they are claiming.”

A few Western observers have pointed out that Russia is probably exaggerating its military might for political effect, but for the most part official US and NATO spokespeople seem content to go along with it.

“It's a very well-known and time-honored game, in which hardliners on both sides use the propaganda stereotypes of their opponents to fuel their own narratives,” says Sergei Strokan, foreign affairs columnist for the Moscow business daily Kommersant. “Why would anybody from NATO want to argue that the Russians aren't as big a threat as they claim to be?”

More fundamentally, experts add, neither Russia nor China has any interest in creating a formal military alliance, with the reciprocal obligations that would entail. Both have repeatedly rejected the idea, and insisted that the present relationship – which they describe as a “strategic partnership” – is quite enough.

Sergei Uyanaev, deputy director of the official Institute of Far East Studies in Moscow, says that China would have no interest at all in getting dragged into Russia's European confrontation with NATO, or its antagonisms with the West over Ukraine. For its part, Russia may offer rhetorical support, but wants no part of China's conflict with the US and regional countries over territorial claims in the South China Sea.

“Both sides want to maintain an independent foreign policy, and not to take on any more responsibilities than they need,” says Mr. Uyanaev. “At the same time, both feel pressured by the US, and this is driving them together. These military exercises are a carefully staged message, primarily to the US, but they are probably not a sign of bigger things to come.”

The Redirect

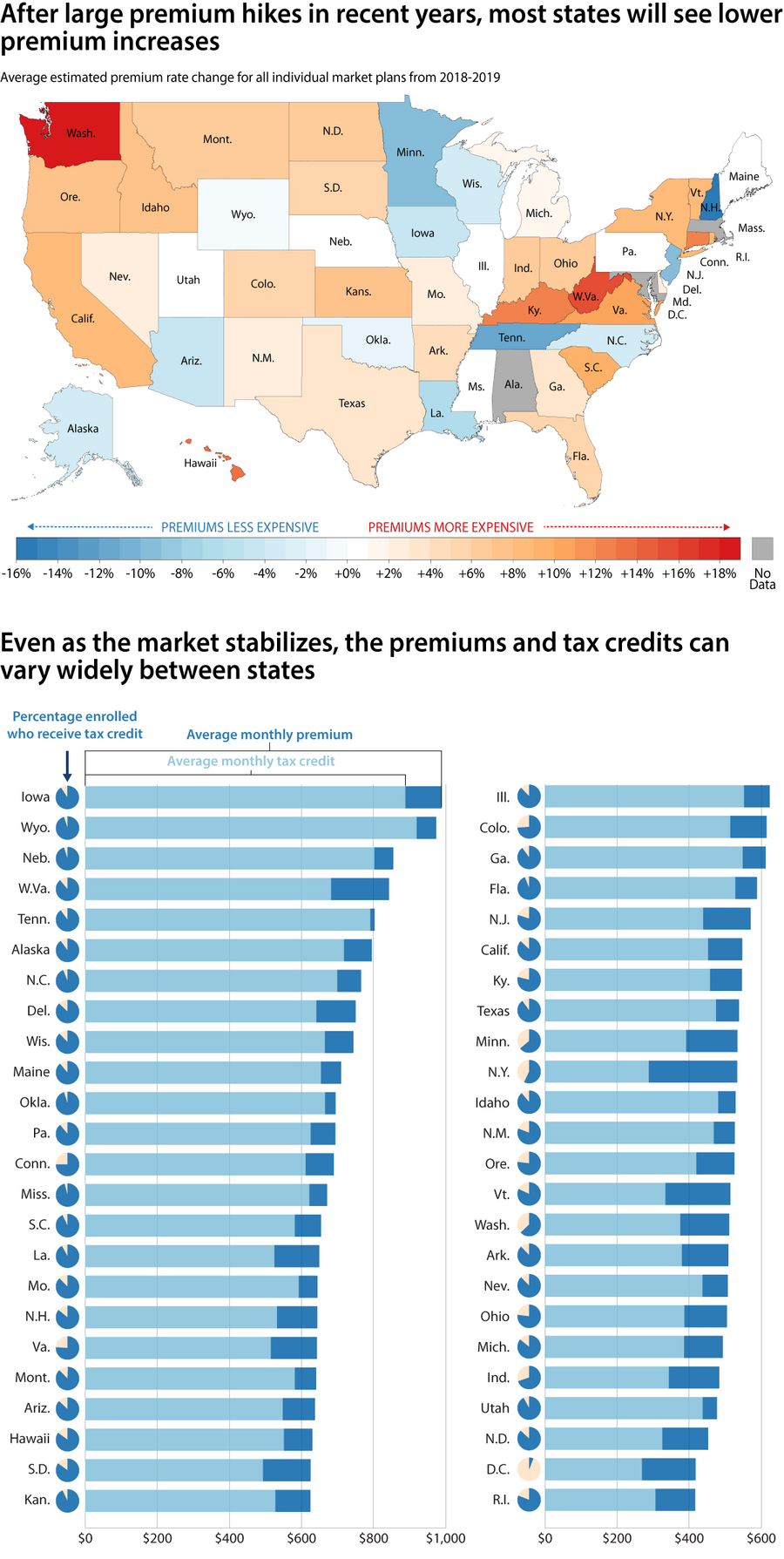

What the Affordable Care Act has really meant for insurance shoppers

The idea for this graphic came from a reader. She wanted a state-by-state look at how the Affordable Care Act was affecting premiums so she could cut through all the political spin herself. We thought: What a great idea! So ... voilà!

The outlook for the Affordable Care Act seemed bleak heading into 2019. Republicans were taking steps to undercut it, such as reducing assistance for enrolling in the ACA insurance marketplaces. Premiums had been rising in many states at double-digit rates, partly due to concerns that enrollment would plummet. The reality today is surprising. Bucking fears, all counties have at least one insurer offering ACA plans. The average shopper for an individual insurance plan will pay just 3.3 percent more in 2019, according to an analysis by consulting firm Avalere Health and The Associated Press. In 12 states, average premiums will actually drop. Basically, enrollment didn’t fall off in 2018, and insurers ended up being profitable, giving them the ability to keep premiums stable, says John Holahan of the Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center. Stable premiums might help insurers attract a group with low enrollment: those above 400 percent of the poverty line, who don’t qualify for tax credits. “We'll just have to see what [insurers’] experience is this year,” says Mr. Holahan. “And if it’s bad ... they’ll probably jack up premiums again. But so far the 2019 experience has been surprising and has been a good thing.” – Rebecca Asoulin

Analysis by consulting firm Avalere Health and The Associated Press

In Jordan, ‘house of safety’ offers hope and freedom to at-risk women

Here’s a story that embodies so much of the Monitor – exposing the venal and brutal thinking that has surrounded so-called ‘honor’ crimes in the Muslim world for so long, and finding the seeds of change taking root.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

Amira can no longer look at navy blue – the color of the prison uniform she wore for a decade and a half. She was living in prison for her own protection, placed in administrative detention after her brothers tried to kill her in a so-called honor crime. It’s a controversial practice Jordan has carried on for decades, for survivors who have nowhere else to turn. Amira still carries the physical scars from her brothers’ attack, including a bullet lodged in her chest. But it’s the psychological scars of prison that run deepest. For years, Jordan’s government and civil society groups have worked to create an alternative for survivors – to support rather than punish them and to change perceptions of at-risk women. Their solution is Dar Amneh, literally the “house of safety”: a jointly run guest house to help them build new lives. Dar Amneh, which opened this month, designs a program to prepare each guest to reconnect to society and, when possible, to reconcile with her family. Reminders of the threats residents face are never far, but it’s a world away from prison. “This center would have been rebirth for me … a new beginning,” Amira says.

In Jordan, ‘house of safety’ offers hope and freedom to at-risk women

On the outskirts of Amman, the guests have just arrived at a walled villa, a guesthouse with an idyllic garden of lemon, apricot, and pomegranate trees, a barbecue grill, and wicker lounges arranged around a 2-meter-high fountain.

Awaiting them inside – above the communal fireplace and granite countertop kitchen – are brand new individual apartments complete with fully stocked kitchens, flat-screen TVs, a children’s playroom, digital washing machines, even treadmills.

Although the residence houses guests, this is no hotel. This is the last refuge for women who have nowhere left to turn.

Dar Amneh, literally the “house of safety,” is a unique joint project by civil society groups and the Jordanian government to help women at the risk of violence from their own families build new lives.

In Jordan, some two dozen women are killed each year in so-called “honor” crimes, when a family member murders a female relative to clear the family name of a perceived stigma, such as pregnancy out of wedlock or purported promiscuity.

What often goes unreported are the dozens of additional attempted murders, death threats, and instances of physical abuse against women by their very own relatives.

But the newly opened guesthouse is more than just a solution for when tribal and family ties break down; activists and officials say it is a program geared to change perceptions of the at-risk women – including in their own communities – so that they are seen as victims.

The women’s plight is more than a simple matter of security and safety. In tribal societies such as Jordan, the family is a safety net; it provides for its members, protects them, and fills a welfare and security role often played by the state in the West.

“If you are threatened with violence or murder in Jordan, your family protects you and supports you – but what do you do when that threat comes from within the family itself?” says Raghda Azza, the Dar Amneh director and a longtime women’s activist.

“That is when the system breaks down,” she says, “and everyone, including the government, families and law enforcement, are out of options.”

The reality behind the 'honor'

What makes these crimes even more complicated is that while men claim to commit these acts out of so-called family honor, in reality most are motivated by money, inheritance, or at times simple jealousies and sibling rivalries – all masked in a way to benefit from a law that until recently granted leniency to “honor” killers.

Unable to return threatened women to their families or help them start a new life elsewhere, for decades the government did the only thing it could: place women in protective custody.

Under a controversial measure called “administrative detention,” the local governor would hear each woman’s case and – if she were deemed at risk – place her in a woman’s prison “for her safety” for a one-year period, renewable each year.

With the government ill-equipped to facilitate reconciliation between these women and their families or to provide them with a new life, these detention periods are renewed indefinitely. Women have spent 7, 10, even 15 years in prison.

“The easy answer for both the family and the government to ‘close the file’ on these women was prison,” says Eva Abu Halaweh, director of the Mizan Law Group, which has advocated for these detained women for the last decade.

“Authorities don’t want to jail women, families don’t want to jail their daughters, they just don’t believe there is an alternative,” she says.

Although Jordan amended its laws in 2017 to close a loophole granting leniency to honor killers, and judges have passed down harsher sentences in recent months, the administrative detentions continue.

The practice has left dozens of women lost in the prison system. Women such as Amira.

Amira, now 55, who knows the plight of detained women all too well, still carries the physical scars from when her brothers attempted to kill her over a rumor: slash marks from a butcher’s knife cross her chest; a gunshot scar crinkles her chin; a bullet is lodged in her chest. But the psychological scars of spending 14 years in prison are what run deepest and resurface most often.

Amira can no longer wear or even look at navy blue, the color of the prison uniform she wore for a decade and a half. And spurred by years of being deprived of her favorite foods, she cooks extra at every meal: mounds of stuffed grape leaves – her favorite – and eggplant and chicken.

Many days she wakes up crying, unable to believe she has her own apartment and can move at her own free will. Amira does not live in Dar Amneh, but she participated in a pilot program that led to the creation of the shelter, and is part of a generation of an estimated hundreds of women who have lost decades in prison.

“There is not one day, not one hour, not one minute that goes by without me remembering my life in that place,” says Amira, who prefers to use a pseudonym for her protection.

Search for an alternative

For years, the government and civil society groups and activists worked to establish an alternative for women like Amira – to support rather than punish them. Their solution: a hybrid center combining NGOs’ experience with the government’s resources and authority.

Under the new model, civil society and women’s rights groups provide services, legal representation, case evaluation, and, when possible, family reconciliations. Under the umbrella of Jordan’s Ministry of Social Development, the state provides security and political backing, with the government carrying the legal responsibility for the women’s lives.

Working off the experiences of shelters in Tunisia and France, organizers fitted best practices to the more tribal Jordanian society and this month finally opened Dar Amneh to its first guests. Eight women are already there, and 22 are expected by the end of this month.

Women like Amira will no longer be sent to prison. They will be given a choice.

Amira was released from prison in 2008 to Mizan Law Group after an arrangement with the government. But she says if Dar Amneh had existed, she would have been spared “a lifetime” behind bars and a daily reminder of her trauma.

“This center [Dar Amneh] would have been rebirth for me … a new beginning,” she says.

Dar Amneh says its goal is to create a calm and relaxed atmosphere to create a sense of stability for women whose lives have been out of their control for years.

The center gives women an initial evaluation with a social worker, a lawyer, and women’s rights advocates. They design a specially tailored program to prepare each guest for a new life, to reconnect to society and, when possible, to reconcile with their family.

They are then asked if they consent to the program. They are free to leave the guest house at any time.

“These women have been deprived of choice,” Ms. Azza says, “our role is to give them the best options available and allow them to choose their future.”

Experts provide courses on life skills such as time management, anger management, communication, parenting, and social skills that may have been frayed by years behind bars.

In order to help the women become self-sufficient, Dar Amneh is working with organizations to provide courses in secretarial work, manufacturing, and interview skills, plus tutorials on how to set up their own small businesses or apply for grants from Microfund for Women and other organizations.

Once women and specialists agree they are able to leave the guest house and start their new life, after an estimated six months to two years, Dar Amneh will arrange with security services to place them in a neighborhood or town far from their family if they are still at risk.

Need for security

Yet despite Dar Amneh’s soothing pastel colors and luxurious amenities, reminders of the very real threat these women face is never too far.

A fiberglass barrier extends over the villa’s walls to prevent any neighbor from peering in or entering. An armed guard is on duty around the clock in a white security kiosk similar to those at diplomatic missions and embassies.

The compound is located at the very edge of a remote neighborhood on Amman’s outskirts; the staff use a driver to bring visitors to the center so as not to give out the address.

Inside, mobile phones are banned in case GPS-driven apps and social media “check-ins” reveal the location of staff members and guests. Everyone, including the administration, uses a landline to communicate with the outside world. But it is a world away from prison.

“Here they can see the sky; there is no sky in prison,” says Azza as she checks on the sprouting eggplants and bell peppers in the garden. “But that alone is not enough. Soon they will acclimate and want what everyone deserves – freedom.”

With Dar Amneh in place, Abu Halaweh and other activists say they are preparing to challenge the legality of administrative detentions in the courts and – by making it easier for women to report assault or intimidation by their family – strip away another layer of attackers’ impunity.

“When you make people aware that these women are victims and deserve support, it is a big step,” says Abu Halaweh, the women’s rights activist. “The next step is to end this practice and hold perpetrators to account.”

In a press statement Thursday, Jordan’s minister of social development, Hala Lattouf, announced that the detention of at-risk women will end completely by the end of the year, noting that the Dar Amneh “experience has proven the possibility of replacing administrative detention with rehabilitation, integration and reconciliation.”

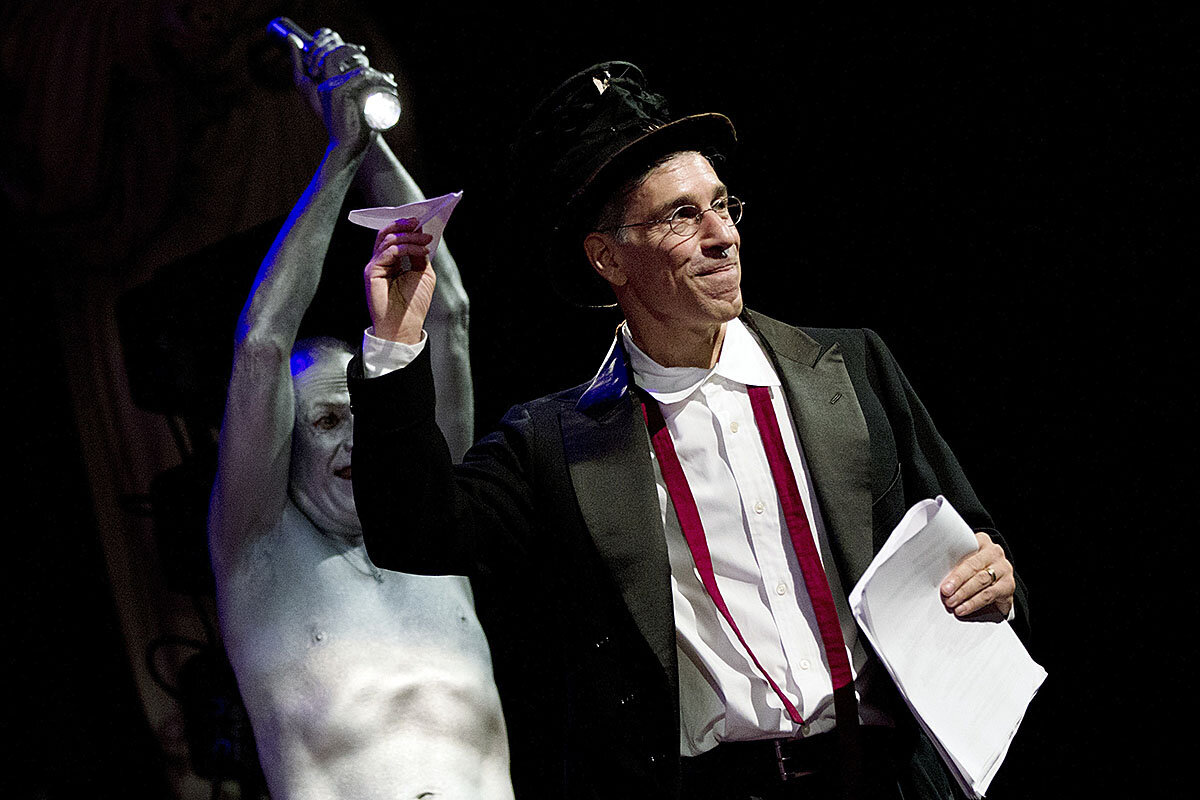

At the Ig Nobel Prize awards, science meets silliness

An annual tongue-in-cheek awards ceremony at Harvard highlights the importance of play, lateral thinking, and outright frivolity in the natural sciences.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Science is often seen as a solemn discipline fraught with weighty questions. But on Thursday evening, an awards ceremony in Cambridge, Mass., celebrated a different side of science. Held annually at Harvard University, the Ig Nobel Prizes honor scientific achievements that first make people laugh, then think. For example, one prize this year was awarded to researchers who measured the effectiveness of human saliva as a cleaning product. But the goofiness may not always be trivial. The science that earns Nobel Prizes often comes from researchers who don't shy away from quirky questions or methods deemed crazy. Charles Darwin himself engaged in what he called "fool's experiments" to operate on the fringe. “The tradition is that if there’s science and laughter together, something’s wrong," says Marc Abrahams, a founder and master of ceremonies at the Ig Nobels. "And in fact, it's almost the opposite, if you really pay attention."

At the Ig Nobel Prize awards, science meets silliness

On Thursday evening at Harvard University’s elegant, 1,000-seat Sanders Theatre, four Nobel laureates wait on stage to present awards. “Human spotlights” wearing silver body paint and little else stand holding flashlights high. Once the ceremony gets under way, paper airplanes soar overhead. Scientists try to clean a painting with their saliva. Later, a Tesla coil discharges writhing purple sparks, the buzzing crackles echoing throughout the wood-paneled theater.

Held annually at Harvard, the Ig Nobel Prizes honor 10 achievements – usually scientific research – that first makes people laugh, and then think.

Winners of the 2018 prizes include scientists who found that chimpanzees imitate humans about as often and as well as humans imitate chimps, and researchers who measured the cleaning effectiveness of human saliva.

Science is often seen as a solemn discipline in which researchers contemplate weighty questions. The Ig Nobels are anything but that. But such silliness may hold a vital place in science.

“The tradition is that if there’s science and laughter together, something’s wrong. And in fact, it's almost the opposite, if you really pay attention,” says Marc Abrahams, founder of the Ig Nobels, which are in their 28th year. Quirky questions and simple curiosity can drive more serious scientific breakthroughs.

Dudley Herschbach, a professor emeritus of chemistry at Harvard, is no stranger to that concept. When he began his work using molecular beams to analyze chemical reactions, many senior scientists in the field “thought it was ridiculous to try,” Dr. Herschbach recalls. But it worked, opening up a wide variety of research possibilities, and earning Herschbach and colleagues the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1986.

Unconventional thinking typically drives Nobel Prize worthy breakthroughs, says Herschbach, who has participated in past Ig Nobel ceremonies. But such unbounded curiosity isn’t just rewarded in science, it’s also inherent.

“Scientists are really kids. They’re the ones who are really curious, and they never grow up. They stay curious. That’s an important aspect of science,” Herschbach says.

Some of the most famous scientists in history have embodied that unbridled curiosity about the world around them. Charles Darwin, for example, conducted what he called “fool’s experiments,” in which he challenged the obvious. In one, he placed some pollen from a male flower with an unfertilized female flower under a jar just to see whether they would interact with no pollinator present.

Some Ig-Nobel-winning findings have arisen from that same sort of pondering. For example, last year’s physics prize went to a scientist who investigated whether a cat could be considered both a solid and a liquid prompted by observations of felines pouring their bodies into various vessels.

Another previous winner, Andre Geim who won the Ig Nobel prize in 2000 for using magnets to levitate a frog, applied that same ingenuity to his work on graphene, which earned him and a colleague the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Sometimes exploratory research can lead more directly to big breakthroughs, too. Take the origins of Wi-Fi, for example. Stephen Hawking theorized in 1974 that black holes might not always be black, and a young Australian scientist was intrigued by that question. But when John O’Sullivan and colleagues set out to make observations that would test the theory, they found that the equipment wasn’t quite right. They made some adaptations, and the result is the backbone of modern Wi-Fi.

The questions posed and experimental setups may be quirky and inventive, but Ed Cussler, a chemical engineer and professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota, says scientists are still coloring within the lines when they approach them by using the toolbox of the scientific method.

Dr. Cussler himself won an Ig Nobel prize in 2005 along with colleagues for conducting an experiment that showed that, compared to swimming in water, people do not swim faster or slower in syrup. That question had dogged Isaac Newton and Christiaan Huygens, who had been in disagreement over it but had no way to test it themselves.

“The charm, to me, is not inventing new science to explain these phenomena,” says Cussler. “It’s using the science that’s been in your head in a way that you didn’t expect to.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A golden lesson from the 2008 financial crisis

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Ten years ago tomorrow, the financial firm Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, triggering the worst global recession in decades. Many are marking the date by noting lessons learned. Largely unnoticed, however, is the fact that it awakened an improved culture of prudence in many financial firms as well as other companies. Out of the bust came a boom in the hiring of “chief risk officers.” Such employees today are integral to many companies. They spot hidden operational risks, such as fraud or excessive debt. One guiding task: Don’t let a company think that it can take on more risk by assuming government or creditors will rescue it. The crisis did lead to bailouts, a step seen as necessary to prevent a systemic collapse. But Washington also set down tough rules to push companies into avoiding “moral hazard,” a tendency to take big risks because of that belief in inevitable bailout. And the risk officers the crisis spawned? They really are affinity coaches, enabling empathy among employees toward clients, customers, even the broader economy. In that sort of morality, there is little or no hazard.

A golden lesson from the 2008 financial crisis

Ten years ago on Sept. 15, the financial firm Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, triggering the worst global recession in decades. The 2008-09 economic crash created much hardship and exposed many inequities, yet it also led to new regulations and spawned endless books and movies about the lessons learned.

Largely unnoticed on this 10th anniversary, however, is the fact that it also awakened an improved culture of prudence in many financial firms as well as other companies. Out of the bust came a boom in the hiring of “chief risk officers.”

While financial crises are hardly new, the job of “risk manager” was invented only about two decades ago. Such employees are now integral to many companies, charged with spotting hidden operational risks, such as fraud or excessive debt.

One overall purpose in their job: Don’t let a company become complacent in thinking it can take on more risk by assuming government or creditors will rescue it.

The crisis a decade ago did lead to massive bailouts of several firms, a step seen at the time as necessary to prevent a systemic collapse of financial markets. But Washington also set down tough rules to push companies into avoiding “moral hazard,” or a tendency to take big risks because of a belief that government will ride to the rescue again.

“There was a real danger that moral hazard created by our actions to resolve this crisis could plant the seeds of a future crisis,” wrote Timothy Geithner in a 2014 book about his role during the crisis as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Part of a risk officer’s job is to help managers avoid poor decisions that would badly affect the welfare of others – such as the past practice of selling mortgages without full disclosure about the ability of homeowners to pay them off.

“If you fail to ... serve customers and counterparties in an ethical manner, you could be headed for some negative outcomes,” says Nancy Foster, head of The Risk Management Association, a body of some 18,000 professionals.

If more banks now see themselves in the welfare of others, they are practicing the golden rule. Risk officers are really affinity coaches, enabling empathy among employees toward clients, customers, and even the broader economy.

In that sort of morality, there is little or no hazard. And perhaps it is also a key lesson from a crisis that has offered so many teachable moments.

A message of love

A routine roundup

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. We deeply appreciate your support of Monitor journalism. On Monday, we’ll have a look at what the economic world has learned since the collapse of Lehman Brothers investment bank, which happened 10 years ago this weekend and was seen as marking the deepest crisis of the Great Recession.

Also, we have a bonus story for your weekend, as the Monitor’s Peter Rainer looks at how comprehensively #MeToo has affected one of the annual rites of the film world, the Toronto Film Festival. You can read Peter’s full report from Toronto here.