- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In Midwest swing states, a ‘red wall’ for Republicans could crack

- Service to country: In Kentucky, the fight to bring more veterans to Congress

- In addressing gun violence, a push to understand its main source

- No longer ‘protected’: A migrant policy shift upends deeply rooted lives

- Patron of the past: The duke who’s preserving the soul of the Levant

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

'We have more that unites us'

It’s a big week for Americans. Many have commented on the contentious tone ahead of Tuesday’s midterm elections. But it’s worth noting as well the heart on display.

On Friday and Saturday, Jews and non-Jews across the country heeded a #ShowUpforShabbat campaign after the attack on a Pittsburgh synagogue. As Rabbi Karyn Kedar told an Illinois gathering, “Communities all over the world gather in their sanctuaries, to turn them into sanctuaries again.”

In Seal Beach, Calif., a fan of the Donut City shop noticed proprietor John Chhan working solo and asked after his wife, who turned out to be ill. The neighborhood mobilized. Saturday, they bought all his inventory by 8:30 a.m. so he could close and go be with her. “I feel very warm,” he told NBC News.

And North Ogden, Utah, turned out for Maj. Brent Taylor, killed Saturday in Afghanistan. Neighbors created impromptu memorials and prayed for him and his wife and seven children at church. Many noted his last Facebook post, which lauded the recent Afghan election. “I hope everyone back home exercises their precious right to vote,” he wrote, and that “we all remember that we have far more … that unites us than divides us.”

Monitor writers around the US are poised to help you parse the election’s themes and outcomes as they watch ballot initiatives, too-close-to-call races, and all sorts of potential “firsts.” You can find their stories in the evening Daily or get a jump-start at csmonitor.com starting early Tuesday. Get in the spirit with this file from Linda Feldmann on her whirlwind weekend tour on Air Force One with the ultimate “closer”, President Trump.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In Midwest swing states, a ‘red wall’ for Republicans could crack

With the midterms looming, is the so-called Rust Belt – the parts of the northeastern and midwestern United States where industries have hollowed out – still as pivotal as it was two years ago? The answer appears to be yes, but for new reasons.

In 2016, after Pennsylvania went for a Republican presidential candidate for the first time in 30 years, some Democratic strategists fretted that this swing state had perhaps begun to tip irreparably red. Two years later, those fears haven’t panned out. Indeed, the Democratic incumbents running for statewide office have racked up big leads. It’s a pattern playing out in other key Midwest and industrial states – like Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin – that President Trump narrowly won in 2016 and where Democratic candidates are pitching messages of sensible governance. The president still has plenty of supporters in these states. And nothing is final until voters actually cast their ballots. But the political landscape raises the question of whether the style and message that worked so well for Mr. Trump two years ago just haven’t translated to other Republicans in the region – or is now giving Democrats a boost. “I really hate that stuff that he’s got against immigrants,” says Bill Sarten, a Republican from Beaver, Pa., who voted for Trump in 2016 but plans to vote for Democratic candidates on Tuesday.

In Midwest swing states, a ‘red wall’ for Republicans could crack

Bill Sarten was worried about his guns.

The lifelong hunter had seen the ads warning voters that Hillary Clinton would leave them defenseless. He’d heard the speeches calling her the most anti-gun candidate ever to run for president. And he’d chafed at the thought of an administration that would erode his Second Amendment rights.

So in November 2016, Mr. Sarten voted for President Trump.

“That was a mistake,” he says now.

Sarten, a longtime Republican, says that on Tuesday he plans to vote for Gov. Tom Wolf and Rep. Conor Lamb, both incumbent Democrats on his ballot. Their message about expanding health care resonates with Sarten, who’s 84. More than that, he’s not a fan of the hostile tone Mr. Trump has been setting, or the candidates from his party that have embraced it.

“I really hate that stuff that he’s got against immigrants,” Sarten says, shaking his head. “How can you be like that? It’s when guys go against immigrants and everything like that, that causes that guy like in Pittsburgh” – who shot and killed 11 people at a local synagogue – “to go goofy.”

Sarten was one of nearly 3 million Pennsylvanians who helped usher Trump into the White House in 2016, handing the state to a Republican presidential candidate for the first time in 30 years. In the aftermath, Democratic strategists fretted that Pennsylvania, a swing state that leaned blue, had perhaps begun to tip irreparably red.

Two years later, those fears haven’t panned out. In March, Mr. Lamb won a major upset in a special election in the state’s deeply conservative 18th district. Today the state’s House races appear likely to split about evenly by party. The Democratic incumbents running for statewide office have racked up such big leads against their Republican challengers that a pair of analysts have called the races “boring.”

It’s a pattern that’s playing out in other key Midwest and industrial states – like Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin – that Trump narrowly won in 2016 and where Democratic candidates are pitching messages of sensible governance to voters.

The president still has plenty of supporters in these states, fighting hard for his agenda and his party. And as we saw two years ago, nothing is final until voters actually cast their ballots. But it seems the Trump effect hasn’t been very rewarding for Republicans in purple states that went red in 2016.

In Pennsylvania, it helps that Democrats are fielding incumbents at the top of the ticket. A newly redrawn congressional district map has also made the state’s House races more competitive for Democrats than they have been in years. And more broadly, the president’s party almost always loses ground in midterms.

Still, the political landscape here just a day before the election raises the question of whether the style and message that worked so well for Trump two years ago somehow just hasn't translated to other Republican candidates in the region – or if it has even given Democrats a boost.

“All midterm elections, to a greater or lesser degree, are a referendum on the president,” says Terry Madonna, director of the Center for Politics and Public Affairs at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa. “This is greater than any I’ve seen in modern history. Essentially people are voting because of Trump.”

A region-wide trend

Political analysts point out that Democrats are doing best in the states Trump took by a narrow margin.

In Ohio, which he won by 8 points, Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown has been coasting to reelection on a platform of caring for veterans and expanding access to health care. Republicans had hoped to pick off Democratic Sen. Tammy Baldwin in Wisconsin, after Trump shocked Democrats there two years ago, but she’s managed to maintain a double-digit lead against challenger Leah Vukmir by balancing a progressive agenda with a reach-across-the-aisle persona.

In Michigan, some Republicans insist businessman John James can win, but most polls show him trailing Sen. Debbie Stabenow by about 10 points. The state’s gubernatorial race also has Democrat Gretchen Whitmer holding a strong lead over Republican Bill Schuette, thanks in part to her catchy promise to “fix the damn roads.”

Trump’s victory in Pennsylvania, while surprising and significant, was also slim. He only won the state by about 44,000 votes. “To say, after 2016, ‘Hey, Pennsylvania has gone Republican,’ would have been a vast oversimplification,” says Christopher Borick, director of the Muhlenberg College Institute of Public Opinion in Allentown, Pa.

And right now the winds are blowing the Democrats’ way. At the top of their ticket are Governor Wolf and Sen. Bob Casey, neither of whom are particularly exciting, but who are familiar, steady incumbents. Their Republican challengers, former state senator Scott Wagner and Rep. Lou Barletta, have failed to gain traction in either fundraising or the polls despite the way they’ve modeled themselves after Trump.

In one campaign video, Mr. Wagner infamously advised Wolf to put on a catcher’s mask, “because I’m gonna stomp all over your face with golf spikes.” (He later apologized for the remark, calling it a “poor metaphor.”)

“Wagner punches people. Not that he’s less competent, but that persona, maybe it works in Montana. It doesn’t really work in Pennsylvania,” says Melissa Hart, a Republican strategist and former congresswoman who represented the state’s 4th district. “I think if we had nominated a more middle of the road [candidate], we would have done better.”

At the House level, the state Supreme Court’s recent decision to redraw district lines here has shifted a 13 to 5 advantage for Republicans in Congress to a possible even split, if not a 10 to 8 edge for Democrats.

The energy sweeping through the left is one of the factors. Candidates who tailor themselves and their messages to the region – by talking about health care, job security, and practical governance – have a good chance of riding that potential wave, says Mr. Madonna.

Jojo Burgess, a steelworker at a transformer plant in Canonsburg, about 20 miles southwest of Pittsburgh, recalls how his fellow union members just didn’t seem motivated to hit the polls two years ago. “A lot of people lost interest,” he says at a rally at the United Steelworkers headquarters in Pittsburgh, spitting distance from the Ohio River. “People saw Hillary Clinton was up big, so they said, ‘Well we ain’t going to go.’ ”

This time around Mr. Burgess is working to ramp up get-out-the-vote efforts. But he only campaigns for candidates he says reflect working class values like fair labor, access to health care, and job security.

Ryan Prah, who works at the mill in nearby Clairton, also showed up to the rally – and says he liked what he heard. A Coast Guard veteran who loves his guns, Mr. Prah hated seeing the ordeal Cuban migrants were put through as they tried to cross by boat into Galveston, Tex., where he was stationed in the early 2000s. The speeches that Wolf, Senator Casey, and Congressman Lamb made, peppered with references to “the common man” and “the American worker,” hit home for him.

“There’s a lot of people out there that are blowing a lot of smoke, just to get the support of the AFL-CIO,” he says, “but they don’t have a brand or a mind of their own. All these ones do, 100 percent. That’s why I’m here.”

Republican determination ... and doubts

That’s not the prevailing view at the Beaver County Farmers’ Market in Western Pennsylvania.

The Saturday before the election, about a dozen or so vendors brave the chill gray morning to sell crisp produce, fresh breads, and hot food. Most here say they support the president and plan to vote Republican on Tuesday – not surprising in a county that went to Trump by 18 points.

For some, like Patrick Michael, it’s clear-cut: The Democratic Party has lurched too far left. Voters who care about law and order and preventing the US from sliding into socialism need to support the GOP. “I’ve never, ever voted straight Republican or straight Democrat until this election,” Mr. Michael says as he offers stuffed grape leaves and baked kibbeh, traditional Lebanese dishes, for customers to try. “I’m going to go straight Republican on Tuesday.”

Others are less certain. Wayne Harley, who runs the century-old Oak Spring Farm in nearby New Brighton with his wife and youngest son, wants to see leaders who understand issues that affect farmers. He’s not convinced that Wolf, or any Democrat on the ticket, does. He’s also a devout Christian and staunchly pro-life. So Mr. Harley votes Republican.

But he wavers on immigration. As a farmer, he gets the need for migrant labor. He’s also sympathetic to the families in the so-called caravan making its way up from Honduras to the US-Mexico border. They’re the kind of folks his second son, an immigration lawyer, represents.

“It sounds like they’re trying to get out of there. Save their lives and try to find a better life for their kids,” Harley says, watching his youngest unload produce from their truck onto long tables they’ve set up for the sale.

He pauses. “I don’t know how it’s all going to play out.”

Across from the Harleys’ stall, Philip Floyd and his sister Laurie chat with customers looking through their display of pumpkins and squash. Like many here, Mr. Floyd cherishes gun rights, and he intends to use his midterm vote to protect them. The killings at the Tree of Life Congregation in Pittsburgh, however, left him horrified.

“It almost makes me feel a sense of guilt, because this guy legally owned his gun,” Floyd says of the shooter. He adds that thousands of gun owners out there would never do anything so awful. “I don’t know what the answer is, except there is a lot of hate in the country right now.”

Service to country: In Kentucky, the fight to bring more veterans to Congress

Rep. Seth Moulton (D) of Massachusetts thinks Congress needs more courage. That's why one of the Democratic Party's rising stars is out stumping for candidates who, like him, have served in the military.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Can a Massachusetts Democrat help woo voters deep in Trump country? Former Marine fighter pilot Amy McGrath thinks so. With help from Rep. Seth Moulton, a fellow Marine who served four tours of duty in Iraq, she has gone from a political nobody to one of the most closely watched challengers in the country. She’s one of dozens of candidates, many of them veterans, whom Mr. Moulton has endorsed in a bid to bring a new generation of leaders to Congress – leaders who, he argues, will put country above party. Over fried cod tail at a nearby diner, he explains his mission is not only to take back the House for Democrats, but to transform an institution that has become mired in political point-scoring. And he would like to see Congress reclaim its constitutional responsibility to hold the president accountable. In Kentucky, Ms. McGrath’s liberal positions on health care are a hard sell among conservatives, but she is energizing Democrats. “If the Marines can trust her,” says voter Judith Cannon, “I think I can, too.”

Service to country: In Kentucky, the fight to bring more veterans to Congress

You wouldn’t think that a Massachusetts Democrat would be of much help wooing voters deep in Trump Country.

But that’s who retired Marine Corps fighter pilot Amy McGrath enlisted in her bid to win Kentucky’s 6th congressional district, one of the most closely watched races in the country.

Just days before the election, as Democrats bask in the aroma of chili and possible victory at the Bourbon County fairgrounds, Rep. Seth Moulton (D) of Massachusetts – a fellow Marine – steps up to the hay bales and pumpkins to make his pitch for Lieutenant Colonel (retired) McGrath.

“I was just a dumb grunt as an infantry guy, slogging through the mud,” says Congressman Moulton, who served four tours in Iraq. “But I’ll never forget what it meant, what it felt like, when I heard jets coming. They had our back.”

“And that’s the biggest thing about Amy ... she’s going to have your back in Congress,” he continues. “And it doesn’t matter what the Republicans say, it doesn’t matter what our leaders in the Democratic Party say – she’s going to fight for what’s right, because that’s just who she is.”

Moulton is spearheading an ambitious bid to bring a new generation of leaders to Congress – leaders who, he argues, will put country above party on Capitol Hill just as they have in the military. Over fried cod tail at a diner, he explains his mission is not only to take back the House, but to transform an institution that has become mired in political point-scoring – to the detriment of the people they serve.

“My observation is that Congress is not lacking in intelligence – most of my colleagues are pretty smart,” says Moulton. “What Congress is lacking is courage.”

That’s why he was one of the first people to endorse McGrath, who was such a dark horse that her own pollster thought she’d do well to lose the primary by only 20 percentage points to the Democratic Party’s preferred candidate.

With Moulton’s help, she beat him by 8 points.

With Election Day fast approaching, a New York Times/Siena College poll shows her tied with her opponent, Rep. Andy Barr (R).

“My talk of country over party kind of scares both sides, it scares both establishments,” says McGrath. “Seth immediately was like – ‘No, this is the kind of person we need.’ ”

Time for a change?

It wasn’t the first time Moulton challenged the Democratic establishment.

In the wake of the party’s stunning defeat in 2016, he has become one of the most vocal in calling for House minority leader Nancy Pelosi and other senior leaders to step aside.

“Imagine being a CEO – you have the worst returns since 1920, but you say, ‘We’re going to keep the current leadership,’ ” he says. “It’s asinine.”

That has left the party in a position of weakness, he argues, unable to intervene as the GOP-controlled Congress has abdicated its constitutional responsibility to hold the president accountable.

“We all talk about the ways in which [President] Trump is tearing apart our democracy – they’re very real,” he says. “But the Founding Fathers knew that that could happen.... [T]hey designed our system of government so that Congress could be a check on the executive. And the Republican Congress has completely failed in that job.”

Moulton is seen by some as a promising new kind of leader who could be a presidential contender as soon as 2020. But his unabashed criticism of top Democratic figures has provoked grumblings on Capitol Hill, where some members of his own party have described him privately as an opportunistic neophyte.

But in his first term, Moulton was ranked No. 2 for effectiveness among all Democratic freshman legislators by the Center for Effective Lawmaking.

“His success at advancing his legislative agenda in the 114th Congress was very consistent with this rhetoric of trying to cross party lines and forge bridges,” says Alan E. Wiseman of Vanderbilt University, who is co-director of the center.

Moulton has also been ranked among the top 10 percent of representatives for bipartisanship. Now he’s cultivating a group of like-minded veterans or service-minded Americans to join him on Capitol Hill.

In total, Moulton has raised $8 million to support 67 candidates in 28 states. He has also helped the congressional candidates to support each other through a Slack messaging channel, a trip to the Mexican border, and group debate prep sessions. Even as he’s waging his own reelection campaign and navigating the first few weeks as a new dad, he has been crisscrossing the country stumping for his mentees.

They include Conor Lamb, the Pennsylvanian who staged a stunning upset earlier this year; Colin Allred, a former NFL player who – according to a new poll – just pulled ahead of 15-year GOP incumbent Pete Sessions in northern Texas; and McGrath, who has mounted such a strong challenge to Representative Barr that Trump personally came out to rally Republican voters last month.

Often dressed in fleece jackets with minimal makeup and jewelry, she combines a Marine toughness with a mama-bear warmth, as comfortable talking about her kid running around the neighborhood naked as she is underscoring the historic importance of the 2018 vote.

“This election is about the soul of our country,” the mother of three tells the crowd at the chili dinner. It is about who we are, it is about who we want to be, what kind of country we want our kids to grow up in.

“Do we want leaders that always demonize the other side? .... Or do we want leaders with courage?”

She describes herself as leading by example, running a substantive campaign focused on issues rather than attack ads.

But Barr, who was first elected in 2012, challenges that narrative.

“Nobody should be under the false impression that my opponent has somehow run this pristine, positive campaign,” he said in a fiery Oct. 29 debate, accusing McGrath of misrepresenting his record. Among other things, he cited the fact that every single Democrat in the House voted in support for his bill to levy tough sanctions on North Korea, which passed 415-to-2 but is awaiting passage by the Senate. “Despite this narrative that somehow I am partisan, the reality is that I routinely work across the aisle to get things done for the people of this district.”

He also has a strong record of getting results for veterans, says his communications director, Jodi Whitaker. Among his initiatives: setting up the Sixth District Veterans Coalition, which has helped hundreds of veterans resolve disability claims; expanding GI bill eligibility; and allowing survivors of military sexual trauma to seek treatment outside of the VA system.

While McGrath has leaned heavily on her veteran status, some Kentucky veterans have accused her of misleading voters. Though she did become a Marine Corps pilot, during her 89 combat missions bombing Al Qaeda and the Taliban she wasn’t in the pilot’s seat. She was the back-seat weapons system operator.

Judith Cannon of North Middletown doesn’t buy the criticism.

“Was she crocheting or knitting back there?” asks Ms. Cannon outside the chili dinner. “I know how hard she had to work, how much she had to take ... how good she had to be.... If the Marines can trust her, I think I can, too.”

A viral video, funded by aunts

McGrath burst onto the national scene with a debut campaign video, talking about overcoming naysayers to fulfill her childhood dream of becoming a fighter pilot, that attracted more than a million views in just a few days, and brought in $1 million over the next few months.

But there was never any guarantee it would be a success. When McGrath decided to move back home to Kentucky after two decades in the Marines, she knew just two politicians. She called her aunts to ask for money, and went $7,000 in the red to produce that first video.

It was the tenor of that 2016 election that catapulted her into politics.

“The fake news, the divisiveness, the labeling each other.... I just shook my head. This isn’t us,” says McGrath, whose service galvanized her sense that Americans are all in this together.

She recalls a fellow pilot – “Sugar Bear” was his call sign – with whom she worked side by side in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province, a Taliban stronghold. He was a Republican, like her husband, which made for lively debates.

“But man, we came together as Marines to get our job done,” she recalls. One day in 2010 he went out on a mission and was shot down. It’s losses like that, she says, that have given her a larger sense of what it means to serve the country and put people above politics.

“Sugar Bear and I might have disagreements but we never doubted our patriotism, we never doubted our love of country,” she says, adding that Moulton shares the same values. “It isn’t who we are as Americans.”

Perception Gaps

In addressing gun violence, a push to understand its main source

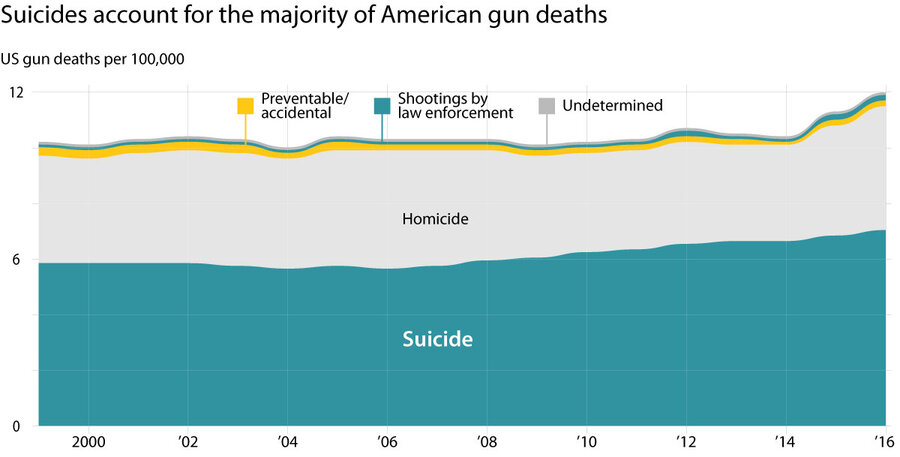

Do you know what's at the root of most gun deaths? Most of us don't immediately think of suicide. This podcast delves into an often overlooked crisis and how people who differ on gun regulation have created a place of trust and cooperation around it.

After mass shootings such as those in Pittsburgh, Parkland, Fla., and Sandy Hook, Conn., there’s a strong desire to prevent these tragic events from happening. But there’s also strong disagreement on how to address the problem. Many Americans are surprised to learn that mass shootings actually account for less than 1 percent of gun violence fatalities in the US. Suicides actually account for most gun deaths. According to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), nearly two-thirds of the 38,000 deaths by firearms in 2017 were due to suicide. In the latest episode of the Perception Gaps podcast, we explore how to have a more productive political conversation around gun violence prevention. After her husband shot himself, Jennifer Stuber became an agent for change in Washington State. She has formed an organization that includes an unusual array of participants, including the National Rifle Association and the Second Amendment Foundation as well as health experts and gun control groups. “These are groups that wouldn't normally come together, but the reason they've come together is around a common goal of saving lives lost to suicide,” she says.

National Safety Council, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

On the move

No longer ‘protected’: A migrant policy shift upends deeply rooted lives

This story helped us grasp the complexities of policies that on paper seem cut and dried. Take Temporary Protected Status, under which immigrant Julio Perez built a good life in the United States. But what seemed secure threatens to come crashing down.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Julio Perez, from El Salvador, lives and works in the United States perfectly legally. But next September, if the Trump administration has its way, he and his family will be expelled. Mr. Perez is living in the US under a program known as Temporary Protected Status, designed for migrants whose home countries have been deemed too unsafe for them to be sent home. President Trump is now rolling back the scheme, which has benefited nearly 500,000 people, as part of his campaign to cut down on migration. That leaves Perez, his wife, and 13-year-old son in limbo, their future up in the air. But they are not resigned to their fate; Perez has joined a migrant-led campaign to halt the deportation of TPS holders and to persuade Congress to legislate a path to permanent residency. If they lose, Perez says he will return to El Salvador and start over. “But we don’t want to go, and that’s why we keep fighting until the last days.”

No longer ‘protected’: A migrant policy shift upends deeply rooted lives

Julio Perez pulls a card from his bulky brown wallet. It is this US government-issued piece of plastic that makes it legal for Mr. Perez to live and work here, to chase the American dream of social mobility.

The card lists his name, date of birth, his nationality – and an expiry date: Sept. 9, 2019.

In the past, that deadline would have meant it was time to re-register for Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a program for migrants whose home countries are in such turmoil that repatriation is deemed unsafe. Perez has extended 12 times since his country, El Salvador, was rocked by two calamitous earthquakes in 2001.

But now President Trump is rolling back the decades-old program, arguing that temporary protections have become permanent and that it is time for migrants to go home. One by one, countries whose citizens had TPS status have been struck off the list.

And so Perez knows that the life that he has built here is due to come crashing down next year – his steady job, his safe home, his 13-year-old son’s education – all terminated.

That prospect led him to join a national migrant-led campaign to halt the deportation of TPS holders and to persuade Congress to legislate a path to permanent residency. Other activist groups have filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration over its handling of TPS. On Oct. 3, a federal judge in California hearing the case issued a temporary injunction against any deportations.

In public, Perez puts an optimistic spin on these efforts and his chances of staying in the US. Some mornings, though, he wakes up and thinks, that’s another day gone, one day fewer until termination.

“People are really afraid. This is limbo. We don’t know where we’ll be in 10 months,” he says.

Perez is not one of the unauthorized foreigners living illegally in the United States, of whom there are between 11 million and 22 million, according to different estimates. He is part of a much smaller group of 436,866 people from 10 countries who have been given explicit permission to stay in the country because of their origins.

By far the largest number are from El Salvador, whose citizens were first granted TPS protection in the 1990s in the aftermath of its civil war. Around 12,000 live in Massachusetts, including thousands of Salvadorans in East Boston, an immigrant-friendly peninsula pressed between Boston’s international airport and its harbor.

“They’re all trying to figure out what to do and praying that TPS doesn’t run out,” says Lydia Edwards, a Boston city councilor who represents the ward. Among them are migrants who own houses and businesses and now face “huge decisions” about personal and financial questions, she adds.

TPS holders pay taxes and social security and must have a clean criminal record in order to renew their permits every 18 months. “I can’t think of another group of people who are more patriotic about this country,” says Ms. Edwards.

Perez lives in a two-bedroom apartment in East Boston with his wife, Marina, who also has TPS, and Moises, their US-born son.He came to Boston in 1994 after first making his way from his village in El Salvador through Guatemala and Mexico by bus and train to the border at Tijuana. Together with hundreds of other migrants he waited for his chance to cross on foot at night, stole past the border agents and made his way to the home of a relative in Los Angeles.

His motivation was opportunity, a belief that he could make a better life in the US. “I knew one day I would come here, and stay here,” he says.

El Salvador was poor and the civil war, which ended in 1992, had seeded a generation of men with guns who formed gangs and preyed on the powerless. But Perez hadn’t come to the US to claim asylum. He had come to work, as he had been doing since leaving school aged 16.

A friend in Boston sent him $500 for a plane ticket. Two days later he flew there, one more undocumented worker chasing a paycheck, one more migrant taking English classes on weekends. It wasn’t hard to find a job; restaurants didn’t ask too many questions. But Perez saw that as an unauthorized immigrant he could only go so far.

In January and February 2001 two massive earthquakes shook El Salvador. They killed more than a thousand people and caused destruction that officials estimated would cost $2.8 billion to repair. The relatives Perez had left behind in El Salvador were unharmed. But his life in the US was about to change.

In March that year, President George W. Bush declared that Salvadorans in the US would be eligible for TPS, so they could find work more easily and remit money to their stricken country. The offer even extended to more than 1,000 migrants then in detention awaiting deportation to El Salvador.

Perez called his boss at the seafood restaurant where he worked. “Don’t wait for me tomorrow,” he told him. The next day he gathered his documents; at nine o’clock, when the doors opened, he was one of the first in line, ahead of hundreds of other hopefuls, to file his application for TPS.

A month later, his card arrived. “That was the best day of my life in the US when I had that document in my hand,” he says.

Being legal meant Perez could find a better job at a hotel in Boston, where he stayed for several years, working his way up to doorman. He grew into a more settled life, volunteering more at his church, which is where he met Marina. They married in 2004, and Moises was born the following year.

Six years ago, Perez was hired as a part-time custodian at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. Today he rides the subway on weekdays to one of the university’s art museums where he’s a team leader, a full-time position that provides health insurance and paid vacation and an annual salary of around $40,000. After paying $1,300 in rent his family’s biggest monthly expense is tuition fees for Moises, who attends a private Catholic school on a partial scholarship.

Marina works in the school kitchen. She finds it hard to express fully the anxiety she feels over what ending TPS means for Moises, who is in eighth grade. “I want to be here. El Salvador is a good country. But there you don’t have opportunities for our child, not like here,” she says.

When the Trump administration announced in January that it was ending protected status for Salvadorans, Perez jumped into action. He joined a statewide committee of TPS holders and volunteered to represent TPS holders employed at Harvard. From a life in the shadows – working off the books, keeping his head down – Perez had emerged as a public advocate. “If you don’t fight for your own cause nobody is going to do it for you,” he says.

In most respects, TPS holders have been fortunate; their permits shielded them from the deportations of unauthorized immigrants that began under President Barack Obama and have continued under Mr. Trump. But their registration also means that authorities now know who they are and where they are and when their permits expire. In theory, that means they will have no choice but to go home.

Ana Alonzo, an attorney at the Salvadoran consulate in Boston, is skeptical. “Frankly, these people are not going to leave,” she says, noting that many have children in school.

“How are you going to take your kids to a country that they’ve never been?” she asks.

The US government’s own assessment, made public by the lawsuit, warned that deported TPS beneficiaries would likely cross illegally back into the US, given their deep ties to the country. Others may preempt deportation by melting back into the unauthorized population.

For Perez, that’s not an option. If he loses his protected status he will move back with his family to El Salvador and start over again. “We don’t want to go, and that’s why we keep fighting until the last days,” he says. “And we’re optimistic that we’re going to get something.”

On a recent weekday morning, Perez and fellow committee members trooped into City Hall in Boston to meet with Edwards and staffers of other councilors. They were joined by a dozen or so TPS holders making a three-month bus journey across the country to lobby politicians and raise awareness of their plight.

After other speakers had their turn, Perez, who has a brush mustache and wears glasses, rose from his chair. Speaking in fluent, accented English, he said he was proud to call himself a Bostonian and that as a migrant he had become part of society. “We are hard workers and we have contributed to this nation in many ways,” he told the councilors.

Two days later, Perez called his supervisor at Harvard to ask for time off. The bus needed a driver for the next leg of its journey and Perez had agreed to fill in. It would be another week of advocacy, of making the case for staying here and staying here legally.

“We don’t want TPS anymore. Our campaign is about permanent residency,” he says.

Patron of the past: The duke who’s preserving the soul of the Levant

If you’ve never met one of those people who seem to embody a nation’s history – and even if you have – read this story. To Jordan’s Duke of Mukhaibeh, stature comes from salvaging his nation’s heritage.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

Patron of the arts, archaeologist, environmentalist, curator, host, farmer, king’s confidant, playboy – Jordan’s first and only duke has played many roles in his life, but there is one he cherishes: promoter and preserver of Jordan’s heritage. Born Mamdouh Bisharat to one of the kingdom’s wealthiest landowning families, the Duke of Mukhaibeh (so named by the late King Hussein of Jordan) has spent six decades protecting Jordan’s heritage and culture. At 80, you can find him at the Duke’s Diwan, the oldest residence in downtown Amman. Its faded robin's egg blue walls feature an eclectic mix of art and history, an extension of the duke himself: photographs of 1930s Amman hang alongside sketches of Roman ruins and Ottoman homes, calligraphic poetry, impressionist paintings, bushels of dried wheat, and a mosaic portrait of his close friend, the late King Hussein. The duke sometimes reminisces about his time in England in the late 1950s – spent at England’s museums and historic sites – which inspired his lifework. “They celebrated their heritage and identity,” Mr. Bisharat says. “I knew we could do the same in Jordan.”

Patron of the past: The duke who’s preserving the soul of the Levant

“Welcome, welcome!” a man in a tattered blazer and a chestnut farmer’s tan says to three dumbstruck university students who have just wandered in off the street and into the faded apartment. “I hope you are hungry.”

The duke, as always, has set a table for six.

“Eat. Then look around and see what Jordan was really like.”

Patron of the arts, archaeologist, environmentalist, curator, host, farmer, king’s confidant, playboy; Jordan’s first and only duke has played many roles in his life – often on the very same day – but there is one he cherishes: promoter and preserver of Jordan’s heritage.

Born Mamdouh Bisharat to one of the kingdom’s wealthiest landowning families, the Duke of Mukhaibeh has spent six decades protecting Jordan’s heritage and culture, and at 80 remains hard to keep up with.

You can find him, for a moment, at the Duke’s Diwan, the oldest residence in downtown Amman, which he has rented at double its value since 2000 to prevent its owner from knocking it down.

While diwan in Arabic is a grand reception hall for a sheikh or royalty, here the apartment from the 1920s is a portal to both the past and present: a living, breathing cultural center, arts space, and museum in the beating heart of Amman.

Its faded robin's egg blue walls feature an eclectic mix of art and history, an extension of the duke himself: photographs of 1930s Amman hang alongside sketches of Roman ruins and Ottoman homes, calligraphic poetry, impressionist paintings, bushels of dried wheat, and a mosaic portrait of his close friend, the late King Hussein of Jordan.

The rooms are arranged to show visitors how Jordanians lived for much of the 20th century. Now, artists and writers use the space for exhibitions, book launches, and work spaces, always free of charge.

The duke often sits in the dining room for lunch with guests. Today is a cream of bulgur wheat soup and green beans, all from his farms, which he offers to a pair of German tourists and Jordanian teenagers.

Mr. Bisharat’s career of preservation started as a teenager in the 1950s.

Upset at the sight of treasure hunters breaking apart Roman statues, columns, and sarcophagi to sell as souvenirs to tourists in nearby Jerusalem, Bisharat arrived at a solution: to buy them himself.

Starting with a headless Roman statue for three dinars ($4.20) in 1958, he salvaged more than 200 pieces destined for the black market, now all registered with the country’s department of antiquities. He then set his sights higher, campaigning for the preservation and restoration of the iconic sites of Umm Qais, Jerash, and the Amman citadel.

With the flow of petrodollars from the neighboring Gulf in the 1980s and 90s, and with it, rapid urbanization and unplanned development, Bisharat acted as a one-person campaign to save historic buildings and monuments from the wrecking ball.

It had become a way of life.

Honoring heritage

“Action!” the duke calls, to no one in particular. Within minutes he has left the diwan.

The duke is always on the move. From a morning of building recycled art in his stately home, he goes to check in on the historic villas he is salvaging down the hill, then to his diwan to lunch with visitors, then to his design center to meet with artists, followed by his farm in central Jordan. He returns back in Amman in time for an embassy reception, and later, a dinner party for seven at home.

Even the duke’s homes are alive, pulsing and flowing with people and art. Film crews move in and out of his old villas, and a calligraphy lesson gathers in the diwan while tourists take photographs and the duke’s employees carry in salvaged wooden furniture, discarded street signs, and stones from Ottoman-era homes. All move with the same kinetic energy he radiates.

He stops on the road outside his home to pick up a discarded bag of chips.

“This is my favorite activity,” he says. Every couple of minutes he stops to pick up trash: plastic bags, soda cans, foam cartons.

While his relatives and other landowning families long ago sold their farms to be developed as apartment complexes and shopping malls, the duke maintains his farm in Mukhaibeh, in the northern Jordan Valley near the Golan Heights, although military restrictions have rendered it unprofitable.

His other ancestral farm in southern Amman is the last plot of open land in the capital. There, he plows the wheat fields, which have been cut in half by an expressway and crowded by an airport, factories, and now, an IKEA.

He maintains the farms and the diwan, the oldest continually inhabited house in Jordan, as a living museum and a reminder to Jordanians and the country’s elite.

“This area was once the bread basket for the Roman Empire,” the duke says, “and now we import wheat from the US.”

“If we don’t go back to living within our means and being self-reliant, we will always be in a crisis.”

If you can convince him to sit still long enough, Bisharat will reminisce about his time in England in the late 1950s, gallivanting with lords and poets, spending days in gentlemen’s clubs such as White’s and Travellers Club, weekending at the country homes of dukes, and meeting four prime ministers.

But it was the days spent at England’s museums, art galleries, and historic sites that were “a revelation,” he says.

“They celebrated their heritage and identity,” Bisharat says. “I knew we could do the same in Jordan.”

Bisharat has done his part: helping establish the country’s National Gallery of Fine Arts and the National House of Poetry, and supporting an art scene.

But the title?

The late King Hussein, enamored with Bisharat’s love of country, decided to make his nickname official, issuing a royal decree in 1974 recognizing him as “Duke of Mukhaibeh.”

Dukedom has not given Bisharat airs.

While Amman’s rich and powerful clog Amman’s narrow streets with Rolls-Royces and Lamborghinis, the duke drives a silver Chevy pickup packed with tomatoes. His blazers and suits are frayed, dating to the 1960s.

“What I learned in England is that it is not the car that you drive or the clothes that you wear that is important,” Bisharat says, preparing for his next supper party, “but whom you dine with.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Is progress on race still possible?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

To other countries, elections in the United States can be an occasion for taking stock of their own moves toward racial equality. As they watch the US, many wonder if they need to hold up similar mirrors. One country took bold action on race last month. In Tunisia, a largely Arab nation with a black minority of 10 to 15 percent of the population, the legislature has passed a strong anti-racism law. Tunisia is now the first African or Arab country to make racial discrimination punishable by a fine and jail time. At the least, the law will help break the taboo of discussing race as a public issue. As in many countries, the mental shift comes after the passage of a law. The race debate in the US likely played a part in Tunisia’s action. While it remains to be seen how the new law will be implemented, Tunisia could now influence other nations in the Middle East and Africa to act more strongly on racial discrimination. What Tunisia did is show that progress on race is possible.

Is progress on race still possible?

In the campaign for the 2018 midterm elections in the United States, the issue of race was a bold backdrop. Would blacks have voting access? Is it racist to send troops to stop Central American migrants? Did the president’s use of words like “nationalist” compel a white supremacist to kill Jews in Pittsburgh? At the same time, the diversity of candidates set a record.

To other countries, elections in the US are seen as a way for its citizens to make progress on race but also take stock of whether the country is moving toward racial equality at all. Few if any countries with a diverse people do such a regular moral accounting in public.

Yet as they watch the US from afar, foreigners often wonder if their country needs to put a similar mirror up to themselves. Their biggest concern is often whether racial progress is possible at all.

Despite the end of slavery, Jim Crow laws, and other landmarks in US history, Americans keep questioning their own progress, especially as the economic prospect for African-American men has slowed in recent decades. Progress is too uneven or sometimes reversed.

Such a concern, however, did not stop one country from taking bold action on race last month.

In Tunisia, a largely Arab nation in North Africa with a black minority of 10 to 15 percent of the population, the legislature has passed a strong anti-racism law. Tunisia is now the first African or Arab country to make racial discrimination punishable by a fine and specific jail time.

As home to the start of the Arab Spring, Tunisia has long been a reformer in the region. It formally abolished slavery in 1846 (well ahead of the US). It has piled up many reforms since overthrowing a dictator in 2011, which has only heightened sensitivities to the racism that lingers within its society.

Many Tunisians were shocked into action in 2016 by two highly publicized instances of abuse of black people. Lawmakers realized they needed a law on the books to help prevent such abuses. The new law, for example, sets a $350 fine and one-to-three months in jail for using racist language in public. More aggressive acts receive stiffer penalties.

At the least, the law will help break the taboo of discussing race as a public issue. As in many countries, the mental shift comes after the passage of a law. Many Tunisians still need to accept that citizenship comes with respect for the equality of others.

Or as one activist, Saadia Mosbah of the anti-racist group M’Nemty (My Dream), put it, “We are all the fruits of one tree.”

The race debate in the US likely played a part in Tunisia’s action. While it remains to be seen how the new law will be implemented, Tunisia could now influence other nations in the Middle East and Africa to act more strongly on racial discrimination. What Tunisia did is show that progress on race is possible.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

My pastor saved me from suicide

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Allison J. Rose-Sonnesyn

Today’s contributor shares how the spiritual, healing ideas in the Bible and the Christian Science textbook freed her from despair and the temptation to commit suicide.

My pastor saved me from suicide

Not long ago, I was in a shared car in my city. In the course of our conversation, the driver expressed his heartbreak and confusion about the fact that the pastor of his church had engaged in an extramarital affair.

My heart went out to him. I tried to encourage him, and as we pulled up in front of my destination, I explained that I was about to attend a church service where my pastor was going to share the good news about God’s love for us, and that he was welcome to come with me. He thought about it, then said he wanted to, but couldn’t because of his work schedule.

Our conversation filled me with renewed appreciation for the pastor of the Christian Science Church – the Bible and the Christian Science textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy. In fact, several years ago, the love and care of this always-available, universal pastor saved my life.

I was overseas for the summer, and during this period I went through difficult times and often felt desperately alone. For the first and only time in my life, I contemplated committing suicide.

One day I was in tears, thinking about suicide as a way out, but not really wanting to die. I had witnessed the effects of individuals’ suicides on my family, and I didn’t want to subject anyone to that, but I also felt helpless and hopeless.

While I was growing up I attended the Christian Science Sunday School, where I had gotten to know my pastor. In fact, I had been gifted my own set of the Bible and Science and Health when I was in kindergarten, and I loved these books. I loved reading from them regularly and brought them with me to Sunday School each week.

Can having two books as pastor really meet the personal, and sometimes critical, needs of an individual and the world? In her “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” Mrs. Eddy describes the relationship we all can have with the Christian Science pastor this way: “Your dual and impersonal pastor, the Bible, and ‘Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,’ is with you; and the Life these give, the Truth they illustrate, the Love they demonstrate, is the great Shepherd that feedeth my flock, and leadeth them ‘beside the still waters’ ” (p. 322).

Ever since I was a child, studying the spiritual laws of God these books contain has made me feel close to God, taught me about God’s love for me and for all His children, showed me how to apply these laws to experience comfort and physical healing, and helped me understand my inseparability from God. So in this moment of deep sadness and loneliness, I reached out to God, divine Love, to help me and to show me what to do.

In that instant, I looked up and saw my Bible and Science and Health on the table across the room from me. It felt like an answer to my prayer – and I went to my pastor. At first, in my extreme need, I didn’t open the books, but simply hugged them, knowing that the spiritual, healing truths they contain would help me and provide me with what I needed. My pastor was with me!

This simple recognition immediately broke the mesmerizing sense of despair, and reminded me that my Father-Mother God is always with me and is constantly helping me. I’m never alone. My tears of helplessness were replaced with tears of hope and gratitude and a feeling of being loved.

After several minutes, I opened the books to familiar passages and regained my emotional and mental equilibrium. To say that I was grateful to God would be an understatement! This “dual and impersonal pastor” had rescued me in my moment of dire personal need.

The healing message that this pastor preaches – about the spiritual laws of God and their applicability to our lives – is equally available for everyone to apply in his or her life, regardless of background or circumstance. All are welcome to come to this pastor to learn more about God as Spirit and about their real identity as the spiritual, blessed, loved, harmonious, and healthy child of God – and to experience the peace and healing that such an understanding brings.

Adapted from an article published in the Sept. 24, 2018, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Art of separation

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Tomorrow come back as we cover the midterm elections in the United States. Tuesday is the day many Americans will essentially weigh in on how they view President Trump's two years of leadership – and the state of politics in the US today.