- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- After Sessions: How Trump move may shift dynamics of Mueller probe

- A Massachusetts Republican, and America’s most popular governor

- On the stumps and on the march, women broke down barriers in 2018

- In these bilingual classrooms, diversity is no longer lost in translation

- How Uganda’s school children became the keepers of the vine

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A spike in voter turnout, and reasons to hope for more

Yvonne Zipp

Yvonne Zipp

So, are you a democracy is half full kind of person?

Almost half of eligible voters turned out Tuesday, according to the United States Elections Project. Now, 47 percent of voters might not sound like reason to celebrate – but that’s the highest percentage in 50 years. More than 110 million people cast their ballot – the first time the United States has ever surpassed 100 million voters in midterms.

That’s not to say that there weren’t problems: Our Southern bureau chief, Patrik Jonsson, is working on a story about voter fairness in the Georgia governor’s race, where one candidate oversaw his own election. Brian Kemp declared victory and resigned as secretary of State today, but his opponent, Stacey Abrams, says she isn’t conceding until every vote is counted.

In 2020, even more people will be eligible to vote.

Six states passed measures Tuesday designed to make voting more fair and make it easier to vote – from establishing automatic registration in Michigan to restoring ex-felons’ voting rights in Florida. Floridians interviewed said it came down to fairness in their decision to give an estimated 1.5 million people their vote back.

Take Darrel Linton, of Hilliard, Fla., a proud Trump voter who says that John F. Kennedy is the only Democrat he has ever voted for. He voted yes on Amendment 4, he told Patrik. “I believe everyone should have the right to vote,” says Mr. Linton. “They are in this country, and voting makes them worth something.”

Now, for our five stories of the day, including a look at how, even in our polarized times, there are states that are happy to vote for “the other team” when it comes time to choose a governor. And for a bonus read, Washington Bureau Chief Linda Feldmann hosted Democratic National Committee chairman Tom Perez today at a Monitor breakfast for reporters. Democratic strategy for 2020? “Expand the electorate,” he told reporters.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

After Sessions: How Trump move may shift dynamics of Mueller probe

President Trump's critics say the replacing of his attorney general is an attempt to end the Mueller investigation. But any subsequent moves by the acting AG to undercut the special counsel would be hard to conceal.

-

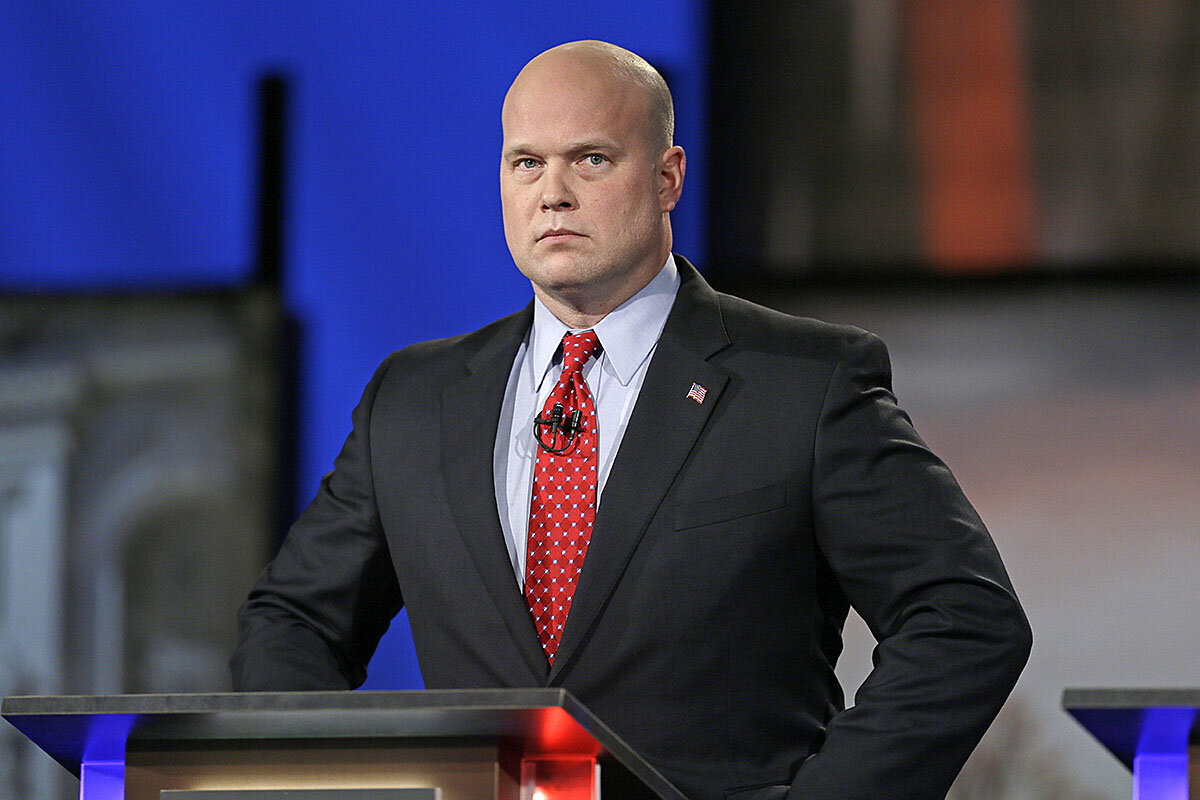

Henry Gass Staff writer

The forced resignation of Attorney General Jeff Sessions – and the elevation of his chief of staff, Matthew Whitaker, to acting attorney general – one day after the midterm elections was executed with the kind of ruthless precision usually found on a grandmaster’s chess board. The highly unusual appointment sent shockwaves across much of official Washington. In a single, bold stroke, President Trump replaced an attorney general who had recused himself from any involvement in the Trump-Russia investigation with someone presumed to be unburdened by that ethical constraint. The move effectively pushed aside Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein as the supervisor of special counsel Robert Mueller. That job now falls to Mr. Whitaker. It remains unclear how Whitaker will use his new authority over Mr. Mueller and his team. But the timing of Mr. Sessions’s removal and Whitaker’s appointment raises questions about Mr. Trump’s motives, according to analysts. “In some ways this isn’t even surprising. It is something everyone expected [Trump] to do,” says Paul Rosenzweig, a senior fellow at the R Street Institute. “It is just incredibly aggressive to do this less than 24 hours after the election. That either reflects incredible self-confidence or incredible panic – or both.”

After Sessions: How Trump move may shift dynamics of Mueller probe

In the summer of 2017, as special counsel Robert Mueller was ramping up his Trump-Russia investigation, a former US attorney in Iowa began offering legal commentary on CNN.

His views clashed with most of the other talking heads on the cable news outlet calling for multiple, wide-ranging investigations of President Trump.

In contrast, Matthew Whitaker, a conservative Republican, argued that the Trump-Russia investigation should be strictly limited to examining whether Mr. Trump or his campaign colluded with Russia to meddle in the 2016 presidential election. And Trump’s financial records, he argued, should be off limits.

His comments did not go unnoticed. By October 2017, Mr. Whitaker had a new job: chief of staff to Attorney General Jeff Sessions.

This week, Whitaker got another promotion. With the forced resignation of Mr. Sessions one day after the midterm elections, Whitaker was named acting attorney general of the United States.

The cabinet-level reorganization was executed with the kind of ruthless precision usually found on a grandmaster’s chess board. The highly unusual appointment sent shockwaves across much of official Washington.

In a single, bold stroke, Trump replaced an attorney general who had recused himself from any involvement in the Trump-Russia investigation with someone presumed to be unburdened by that ethical constraint.

The move effectively pushed aside Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein as the supervisor of the Trump-Russia investigation. That job now falls to Whitaker.

It remains unclear how Whitaker will use his new authority over Mr. Mueller and his team.

The growing partisan divide over the investigation was on clear display in the responses of key lawmakers to the move. Many Democrats immediately condemned it as an effort to undercut the Trump-Russia investigation. Some expressed concern it might lead to an attempt to obstruct justice to protect Trump or members of his family.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D) of Illinois called the maneuver “a transparent effort to clear the way for President Trump to limit or stop the Mueller investigation.” He added: “Acting Attorney General Whitaker has made his intentions clear to do the president’s bidding and stop Mueller.”

But Sen. Chuck Grassley, the Republican chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, struck a very different note. “I look forward to working with Matt Whitaker as he takes the helm of the Justice Department,” Senator Grassley said in a statement. “A fellow Iowan, who I’ve known for many years, Matt will work hard and make us proud.”

He added: “The Justice Department is in good hands during this time of transition.”

It was no secret that Trump was displeased with Sessions. One month after his Senate confirmation, Sessions announced that because of his active work on the Trump campaign, he would recuse himself from any involvement in the ongoing investigation of alleged collusion between the campaign and Russia.

In his absence, Mr. Rosenstein, a former US attorney in Maryland, became acting attorney general for purposes of the Russia investigation.

After Mueller’s appointment as special counsel, Rosenstein’s supervisory authority became critical. It was up to Rosenstein to set the parameters for the investigation. While Mueller was authorized to look into allegations of Trump-Russia collusion, he was also authorized to pursue any matters that “arose or may arise directly from the investigation.”

Mueller has indicted Russians for allegedly using deceptive techniques on social media to influence US public opinion during the 2016 election season. He has also indicted Russian intelligence officers for allegedly hacking into the Democratic Party’s computer system and publicly releasing embarrassing emails and other internal documents prior to the election.

What Mueller hasn’t done – at least so far – is indict any member of the Trump campaign or Trump administration for colluding with Russians during the 2016 campaign.

All of the Americans charged by Mueller have been investigated and prosecuted under an expansive interpretation of the special counsel’s investigative mandate. Those cases, involving lying to federal agents, tax evasion, and bank fraud, were brought in part to increase pressure on certain individuals to cooperate with prosecutors in the Trump-Russia probe.

This is a standard investigative practice, but it highlights the power of whoever supervises the ongoing investigation.

And it’s where Whitaker could have a significant impact, should he seek to enforce a more constrained interpretation of the investigative scope established by Rosenstein, according to legal analysts.

It is not clear that he will do so. But in an opinion essay written for CNN in August 2017, Whitaker said that an attempt by the Mueller team to investigate Trump’s finances would exceed the scope of the special counsel’s mandate.

“It is time for Rosenstein … to order Mueller to limit the scope of his investigation to the four corners of the order appointing him special counsel,” Whitaker wrote. “If he doesn’t, then Mueller’s investigation will eventually start to look like a political fishing expedition.”

’Incredible self-confidence or incredible panic’

The timing of Sessions’ removal and Whitaker’s appointment raise questions about Trump’s motives, according to analysts.

“In some ways this isn’t even surprising. It is something everyone expected [Trump] to do,” says Paul Rosenzweig, a senior fellow at the R Street Institute and a former prosecutor on the staff of independent counsel Ken Starr.

“It is just incredibly aggressive to do this less than 24 hours after the election,” Mr. Rosenzweig says. “That either reflects incredible self-confidence or incredible panic – or both.”

Sarah Turberville of the Project on Government Oversight says Whitaker could help ease concerns about his appointment by publicly reaffirming the independence of Mueller’s investigation.

“While it is perfectly legal under the Vacancies Act for Whitaker to be appointed acting AG, it doesn’t necessarily mean it is the ethical or the right thing for the president to do, given the sensitivity of this investigation,” she says.

“It doesn’t make sense for Whitaker to do anything rash,” Ms. Turberville adds. “By most accounts, the special counsel’s investigation seems to be coming to its natural conclusion.”

Of course, no one knows for sure whether the investigation is nearly complete. (Mueller’s office does not issue such updates.)

Critics are calling on the acting attorney general to follow the same path as Sessions and recuse himself because of his past public comments on the Mueller investigation, and because he served as the campaign treasurer of a former Trump campaign aide who is a grand jury witness in the Mueller probe.

Whitaker has offered no indication that he views these issues as posing a conflict of interest that would require him to step aside.

“I doubt he will recuse himself,” says Kami Chavis, director of the Criminal Justice Program at Wake Forest School of Law.

“But it would also be unusual for a person [in an acting capacity] to make a big, seismic change,” she says. “Typically, when you have someone in an acting or interim role, the idea is that they will act in a professional manner and keep things going.”

And while critics worry that Whitaker is now in a position to undercut or end the Trump-Russia investigation, such actions would be impossible to conceal.

Any effort to sharply limit the Mueller probe would likely attract scrutiny by Senate oversight committees. In addition, the newly-elected Democratic majority in the House has pledged aggressive oversight – and support – for the Mueller probe when Democrats take control in January.

Even if Whitaker ordered Mueller to shut down and ordered all of his records sealed, it wouldn’t prevent members of Congress from issuing subpoenas and forcing Mueller and other officials to turn over documents and testify about any evidence of wrongdoing they had uncovered.

Justice Department credibility

Aside from any potential impact on the Mueller investigation itself, Sessions’ removal and Whitaker’s appointment could damage the Justice Department’s credibility as a government institution that traditionally functions apart from political pressures.

“There’s been a very hard wall between the White House and the Department of Justice regarding the handling of criminal prosecutions,” says Jonathan Smith, a former senior prosecutor in the department’s civil rights division.

The importance of that divide separating justice from politics was reaffirmed during the so-called Saturday Night Massacre in 1973, when Richard Nixon’s attorney general and deputy attorney general resigned instead of following his order to fire Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox.

Given that Sessions’ recusal from investigations of the Trump campaign was the only issue for which Trump consistently criticized him, Wednesday’s forced resignation looked to many analysts suspiciously like an attempt to interfere in the Mueller investigation.

“It may not violate the law, but it is grossly inappropriate,” says Mr. Smith, “and it impugns the independence of the Justice Department.”

Still, others say it’s a far cry from the Watergate scandal.

“[Trump] didn’t fire Sessions because Sessions refused to follow an order,” Rosenzweig says. “There is stuff behind it, but it is a lot less than the Saturday Night Massacre.”

A Massachusetts Republican, and America’s most popular governor

Gov. Charlie Baker is Mr. Fix-it at a time when politics seems broken. In an era of slamming the other side, he listens to the other side.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Christa Case Bryant Staff writer

When Republican Gov. Charlie Baker won reelection in Massachusetts by a landslide this week, two of the most prominent attendees at his victory party were non-Republican mayors – one a Democrat and the other an independent. “When we wake up in the morning, we’re not going to be Democrats and Republicans.... We’re HUUUMAAAAAN,” Mayor Sefatia Romeo Theken of Gloucester bellowed from the stage. “This winter, if we’re going to have a storm, we’re all going to get snowed on together.” It’s an apt metaphor. His fans say Mr. Baker has become the nation’s most popular governor through listening, focusing on 100 percent of his constituents, and taking a pragmatic approach to problems that have included epic blizzards. Baker is not alone in being a governor who’s both popular and moderate. At a time of rampant polarization, two of the other most well-liked governors in America are also Republicans in blue states, while Kansas voters just elected a Democrat over a conservative ideologue. What’s the secret sauce? “The biggest thing we’ve tried to do,” says Baker, “is to not take the bait.”

A Massachusetts Republican, and America’s most popular governor

Republican Gov. Charlie Baker is so busy doing his job, he hardly has time to be political.

He doesn’t pick fights. His speeches are unremarkable. He’s not secretly running for president, at least as far as anyone can tell.

If he picked a team jersey, it would say “Massachusetts,” not “GOP.” Many Democrats can’t find it in themselves to revile him. In fact, some declare they like the guy. Even some who thought Hillary Clinton wasn’t liberal enough admit they have cast ballots for Governor Baker. Twice.

Sure, he’s a Republican, but not that kind of Republican.

“Trump comes out with these insane ideas and most Republicans are like oh, yeah. And [Baker] has the guts to say – we’re not going to do that here,” says Deb Hall, a liberal whose vote helped him win reelection by a landslide this week. “I credit him for that. I’m sure he gets flak for that.”

At a time when the cool kids in the Republican Party are calling their opponents liars and left-wing loonies, Baker is quietly charting another path – working with the other side to get things done. And he’s not alone. Three of the most popular governors in America are Republicans in blue states, and they are demonstrating a pragmatism that shows that it is indeed possible to be reasonable, civil, and productive in an era of extreme polarization.

“[Baker] presents a completely different brand,” says Peter Ubertaccio, a political science professor at Stonehill College outside Boston. “It is almost the opposite of what you see in Washington.”

So what’s his secret?

“I think the biggest thing we’ve tried to do is to not take the bait,” says Baker, standing with Lt. Gov. Karyn Polito outside the Owl Diner in Lowell, Mass., on the eve of Election Day. “I think the biggest challenge in public life these days is to focus on common ground and not on the stuff that divides us.”

Just then, someone drives by yelling, “Baaaaaaaaker!!” and he chuckles before finishing his thought:

“I think people miss their opportunities when they don’t think about it that way,” he says.

Working for 100 percent of citizens

Baker barely got elected in 2014. This week he won by two-thirds of the vote, and is ranked the No. 1 most popular governor in America with a 70 percent approval rating, according to a survey of registered voters by Morning Consult.

Gov. Larry Hogan (R) of Maryland, who ranks second most popular with 67 percent approval rating, also handily won reelection Tuesday in a state where Trump got walloped in 2016. Gov. Chris Sununu (R) of New Hampshire is fourth most popular two years into his term. And Gov. Phil Scott (R) of Vermont, a little farther down the list, secured a second term by a 15-point margin.

Meanwhile in Montana, Gov. Steve Bullock is almost their mirror image – a well-liked Democrat in a state where Trump won by 20 points in 2016. And Democrat Laura Kelly just won the gubernatorial race in Kansas, beating out conservative ideologue Kris Kobach.

“A lot of these folks are folks that get the fact that we are supposed to be working for 100 percent of the citizens that we represent,” says Baker in Lowell, a Democratic stronghold where he and Lieutenant Governor Polito have pushed forward a $225 million new courthouse project that had been tabled for a decade. Looking at her, he adds, “You and I have both had lots of people say to us at one time or another, ‘You know, I don’t agree with you all the time, but I feel like you listen.’ ”

Polito has made good on their 2014 campaign promise to visit all 351 cities and towns in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, listening to local officials and helping advance their priorities.

“You want to get something done, you gotta call Karyn,” said Mayor Dan Rivera (D) of the blue-collar city of Lawrence, which was hit hard by gas explosions this fall.

He was one of two mayors invited to speak at the campaign’s Election Night victory party, the other being Mayor Sefatia Romeo Theken, an independent in the heavily Democratic coastal town of Gloucester. They are among 22 mayors who endorsed Baker, 17 of whom were either Democratic or independent. On Tuesday night, Mayor Theken lauded Baker, echoing the theme of putting aside party loyalties to work for the people. [Editor's note: This paragraph has been updated to correct Mayor Theken's political affiliation.]

“When we wake up in the morning, we’re not going to be Democrats and Republicans … We’re HUUUMAAAAAN,” Mayor Theken bellowed from the stage. “This winter, if we’re going to have a storm, we’re all going to get snowed on together.”

Mr. Fix-It

And boy, has it snowed on Charlie Baker.

In 2015, just as he had taken office, Boston was hit by a historic series of blizzards that wreaked havoc on the MBTA transit system, leaving the city gridlocked for weeks and stranding commuters for hours.

So he spent more than $100 million winterizing the system and took steps to improve the MBTA’s accountability. He announced an $8 billion plan to upgrade the system, including gradually replacing the existing fleet of subway cars, which was more than 30 years old, and increasing capacity by 40 percent.

“He jumped right in and grabbed the bull by the horns,” says Mayor Thomas Koch of Quincy, Mass., who says the city is seeing major economic investment as a result of improvements to the Red Line connecting it to downtown Boston.

Mayor Koch, who was one of the few Democratic mayors to back Baker in 2014, also credits him with providing millions in funding for a new park in downtown Quincy honoring Founding Fathers John Adams and John Hancock – both of whom have ties to the area.

Many have compared Baker to Mitt Romney and William Weld, two GOP governors who also worked well with the Democratic legislature. That cooperation is to a certain extent a reflection of Massachusetts political culture.

“The Massachusetts brand of Republican is all about selling balance to folks … that Republicans and Democrats can work together, that they have to work together,” says GOP state chair Kirsten Hughes.

But state lawmakers today say there’s something special about Baker. He is at ease among Democrats in a way Romney wasn’t, and is remarkably accessible.

“He’s probably worked with the legislature better than any governor,” says Ronald Mariano, the majority leader in the House of Representatives who began as a lawmaker in 1991 – the same year that Governor Weld took office.

As an example, Representative Mariano mentions a compromise he reached with the governor on offshore wind power. Baker, he says, was concerned it would be too expensive but listened to Mariano and other proponents. “Probably one of the main reasons he’s successful is he’s a willing listener, he will seek input on the issues and respects the process. You don’t always see that in governors.”

For Professor Ubertaccio, what is most extraordinary about Baker is his ability to defy the centrifugal forces pulling politicians across America into warring camps.

“We live in such an era of extreme polarization that one would have expected that, at some point, that would have caught up with Baker … and it hasn’t,” says the professor. “There’s a degree to which people are just yearning for government to work, and Charlie Baker seems to be the kind of person they’re looking for.”

On the stumps and on the march, women broke down barriers in 2018

Who or what will break the so-called glass ceiling for women in US politics? The answer seems apparent in this campaign cycle: a surge of newly energized, organized, and mobilized women.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

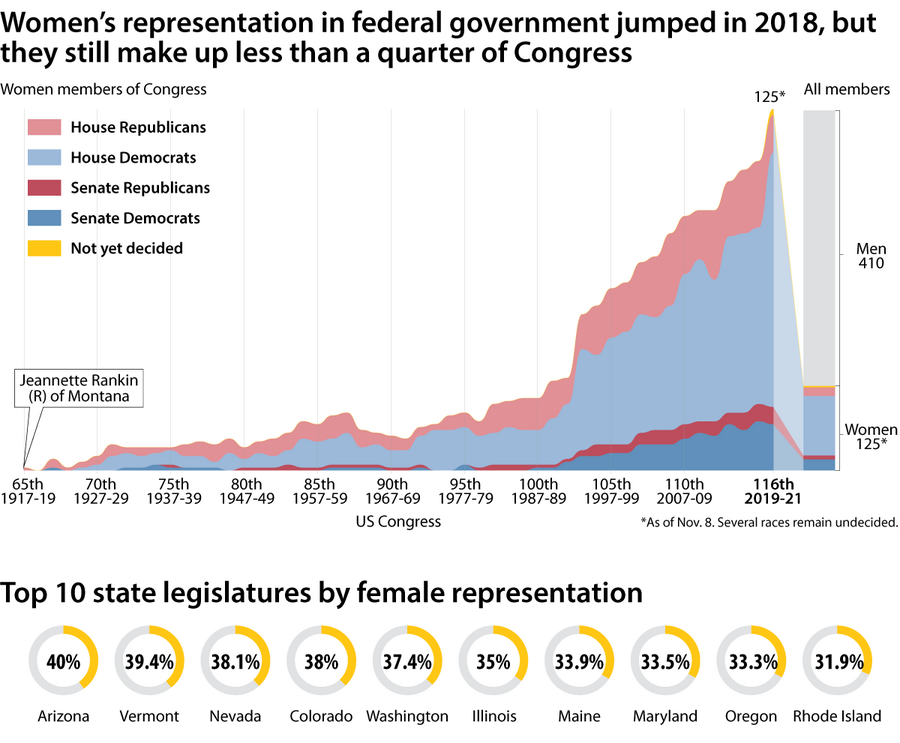

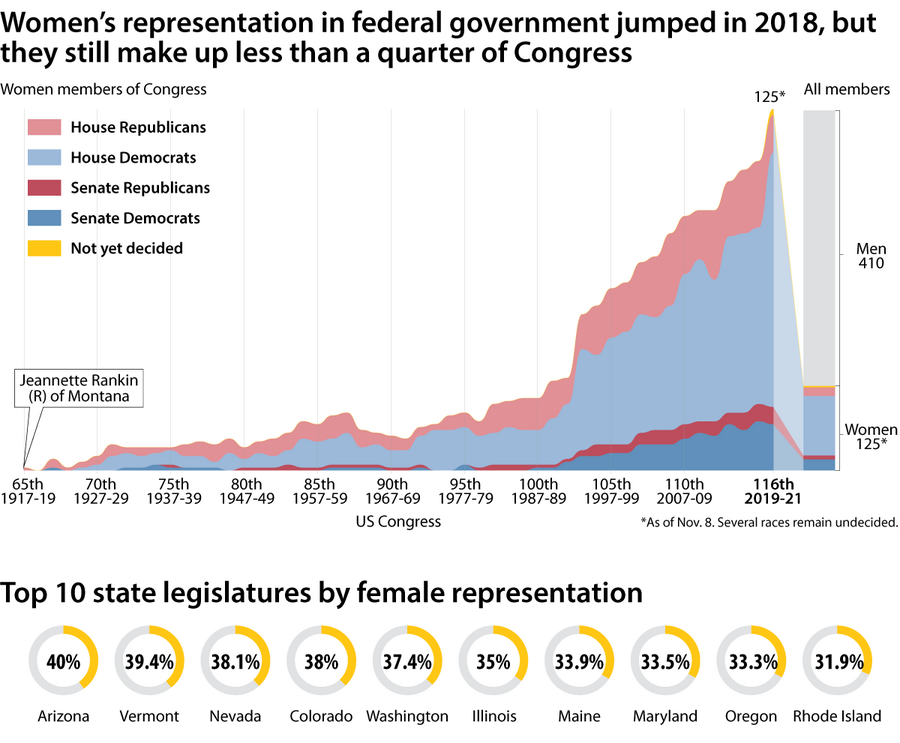

An unprecedented number of women contested races up and down the ticket this week, from Congress to governor’s mansions to town councils. While the gains they made this midterm election leave them far from parity, the effect of thousands of women on the campaign trail has helped break down institutional and cultural barriers. Women now have access to training programs, fundraising, and political networks that before this cycle hadn’t fully matured. Even some of the losses may help lay the groundwork for future women-led campaigns. Stacey Abrams, gubernatorial candidate in Georgia, energized a progressive and diverse constituency in a state that hasn’t seen a Democratic executive since 2003. The one big caveat in the victory narrative is the partisan gap. Republican women racked up their own firsts, but 86 percent of women who will be serving in the next Congress are Democrats. Yet there’s a good chance these newly elected officials are going to stick around. “The incumbency advantage in the US is really strong,” says Mirya Holman, a political science professor at Tulane University. “Once these women are in office, they can probably hold onto those positions.”

On the stumps and on the march, women broke down barriers in 2018

These days, Aryanna Berringer’s bid for Congress sounds almost typical.

She was a young woman of color, new to politics, running as a Democrat against a Republican incumbent. She took her kids with her to campaign rallies, talked about health care and reproductive rights, and touted her military background.

Back in 2012, though, those qualities didn’t shine on the campaign trail the way they would six years later. Ms. Berringer won just 39 percent of the vote, and lost the race to then-Rep. Joe Pitts.

“I didn’t raise much money. And there was certainly not the network that exists today,” says Berringer, who is on the board of Women for The Future Pittsburgh and was active in helping Democratic women campaign this cycle. “I’ve since thought, ‘Man, what if it did when I ran?’ ”

The outcome may not have been any different: Pennsylvania’s 16th District is one of the state’s most conservative, and Democrats haven’t been able to snag that seat in half a century.

But maybe it would have.

Hillary Clinton’s defeat in 2016, so devastating to so many women and girls, prompted an unprecedented number of women to contest races up and down the ticket this year, from Congress to governor’s mansions to town councils.

The gains they made this election leave them far short of parity, however. The share of women in the House, for instance, only went up by about 4 points to 23 percent, and most of them took place on the Democratic side. Some of the most high-profile candidates, like Stacey Abrams in Georgia and Kyrsten Sinema in Arizona, appear to have fallen just short of victory (though at press time, neither race has been called).

Still, the cumulative effect of thousands of women on the campaign trail has undoubtedly helped to break down institutional and cultural barriers. Women now have access to training programs and fundraising and political networks that Berringer would have loved to see in 2012, and that before this cycle hadn’t fully matured. Old standards about who can run successful campaigns, and how, have also shifted, paving the way for more diverse candidate classes in 2020 and beyond.

“People saw that female candidates don’t just look one way, talk one way, think one way,” says Jennifer Lawless, professor of politics at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. “Exposure to lots of different kinds of female candidates and different types of campaigns is the real thing we gain here.”

Surge of interest in running

The first whiffs of change this cycle came in early 2018, in the surge among women interested in running for office. Emily’s List, an organization that supports candidates who back abortion rights, received requests from more than 40,000 women about launching campaigns. (In 2016, the group saw about 900 inquiries.)

At Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J., the Center for American Women and Politics had to close registration for their annual “Ready to Run” campaign workshop and move the event to a bigger venue.

“Nothing like that had ever happened before,” says the center’s associate director Jean Sinzdak.

Then came the campaign ads. By the time the primaries were in full swing, women candidates were going viral as they showed themselves in all their forms: as mothers who breastfed their children, professionals who commuted to work, and veterans who fought for their country.

In May, New York Democrat Liuba Grechen Shirley convinced the Federal Election Commission to allow campaign funds to cover child-care costs. Other states, including Alabama and Texas, have since followed suit.

As the results rolled in, it was clear that the energy wasn’t just in the campaigns. Americans elected at least 100 women to the House Tuesday – breaking the previous record of 85 set in 2016 – and nine governors nationwide, matching the 2004 record. The 23 percent share that women will have in the 116th Congress is the highest it’s ever been.

Center for American Women and Politics, Rutgers, Real Clear Politics

A season of firsts

Firsts were everywhere: the first black woman to represent a Massachusetts district in Ayanna Pressley; the first Muslim women to serve in Congress in Michigan’s Rashida Tlaib and Minnesota’s Ilhan Omar; the first Latinas to represent Texans in Congress in Veronica Escobar and Sylvia Garcia.

In New York, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who’s 29, became the youngest woman ever elected to Congress. In the Kansas Third District, Sharice Davids became the state’s first openly gay representative and one of the first two Native American women in Congress.

And there’s a good chance these newly elected officials are going to stick around. “The incumbency advantage in the US is really strong,” says Mirya Holman, a political science professor at Tulane University in New Orleans. “We focus on the upsets. [But] once these women are in office, they can probably hold onto those positions.”

Even some of the setbacks may help lay the groundwork for future women-led campaigns. Ms. Abrams, who was seeking to become the first African American woman to hold the governorship in Georgia, energized a progressive and diverse constituency in a state that hasn’t seen a Democratic executive since 2003.

In Kentucky – which is still sending an all-male delegation to Congress – former Marine fighter pilot Amy McGrath ran a surprisingly tight race against Republican incumbent Andy Barr in the Sixth District, igniting hopes that a woman could someday take the seat.

In Alabama, every female congressional challenger lost to a male incumbent. But organizers like Stacie Propst – co-founding director of Emerge Alabama, which trains Democratic women to run for office – were never going to let defeat this year sour future attempts.

“If we lose, we lose,” she said in an interview in May. “But eventually there will be women who win.”

Partisan gap

The one big caveat in the victory narrative is the partisan gap. Republican women racked up their own firsts: Marsha Blackburn is the first woman to represent Tennessee in the US Senate and Kristi Noem is South Dakota’s first woman governor.

Of the women who will be serving in the next Congress, 86 percent are Democrats.

“That makes it almost impossible to implement any broad institutional change, because only one party is invested,” Professor Lawless says. She adds that true parity will be hard to achieve if most of the gains come from only one party. And she worries that the gap will cause gender to become even more politicized.

“When women talk about issues that disproportionately affect women – like pay equity, sexual harassment – opponents can say, ‘They’re just Democrats,’ ” she says.

Which isn’t to say the wins aren’t worth savoring for the women who wanted them. On Tuesday night, at an election watch party in Pittsburgh, Berringer had the pleasure of seeing Pennsylvania elect four women to the US House of Representatives – more than at any other time in the state’s history.

“It feels like all the work I’ve been doing since [2012] matters,” she says in a phone call the next day. “We have been going at this for decades in Pennsylvania, and yesterday was a huge win for women. I don’t want people to forget that.”

Staff writers Christa Case Bryant and Rebecca Asoulin contributed to this report.

[Editor's note: A previous version of this article mistakenly stated that Republican candidate Young Kim won the race for California's 39th congressional district. The AP has called the race for her Democratic opponent, Gil Cisneros.]

Center for American Women and Politics, Rutgers, Real Clear Politics

Learning together

In these bilingual classrooms, diversity is no longer lost in translation

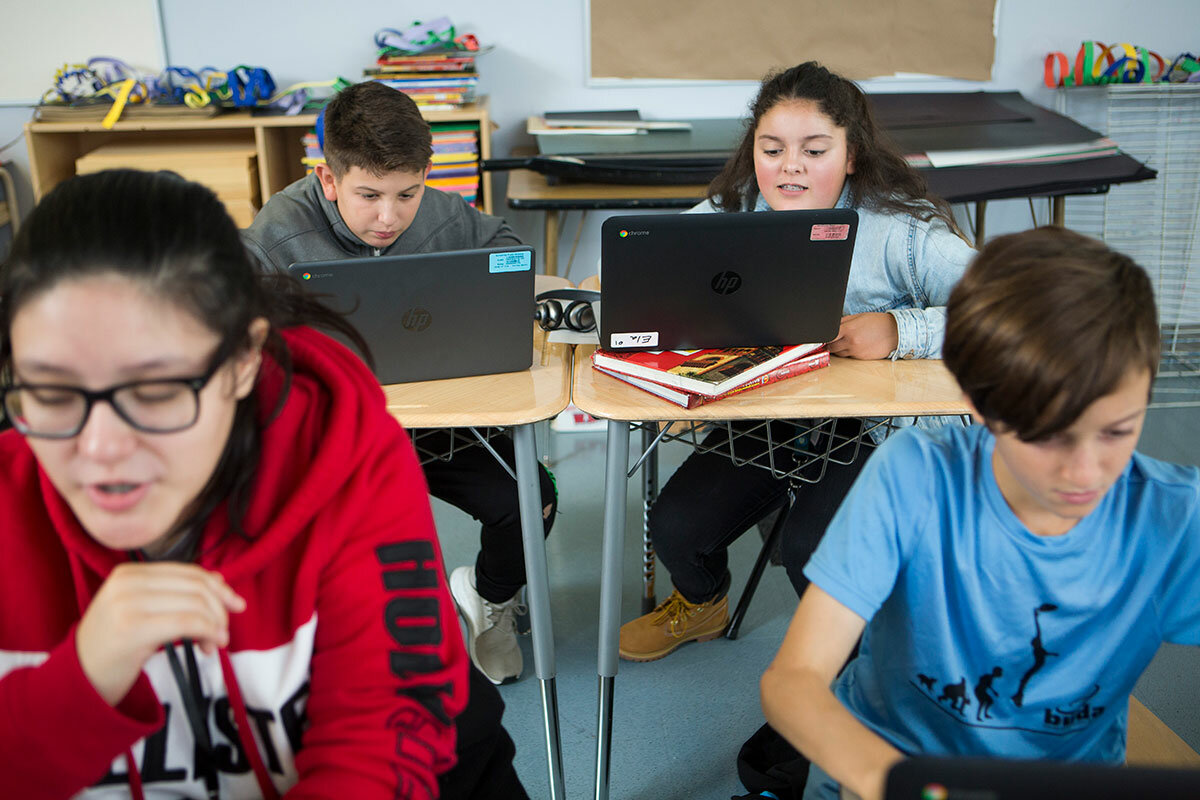

When a second language is seen as an asset, not a burden, it can lead to a powerful byproduct: integration. This is part of an occasional series on efforts to address segregation in schools.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

With the issue of immigration at such a fever pitch in the United States, you might think bilingual education would be stalled. The usual routine, experts say, is like a pendulum: When support for immigration drops, so do funding and policies that bolster multilingual classrooms. And vice versa. But despite prominent anti-immigrant sentiment in the US, one form of bilingual education is actually gaining steam. Two-way dual immersion, which combines fluent English-speakers with English language learners, is taking off. The reason behind the new popularity is simple: Learning in two languages has important academic and economic payoffs. Two-way immersion also celebrates students’ different cultural backgrounds and places value on learning a second language. And closing linguistic gaps can help with closing cultural and racial gaps. “Two-way dual immersion programs do integrate kids,” says Ilana Umansky, assistant professor of education and policy at the University of Oregon. “It is a natural strength of those programs so long as it’s implemented well.”

In these bilingual classrooms, diversity is no longer lost in translation

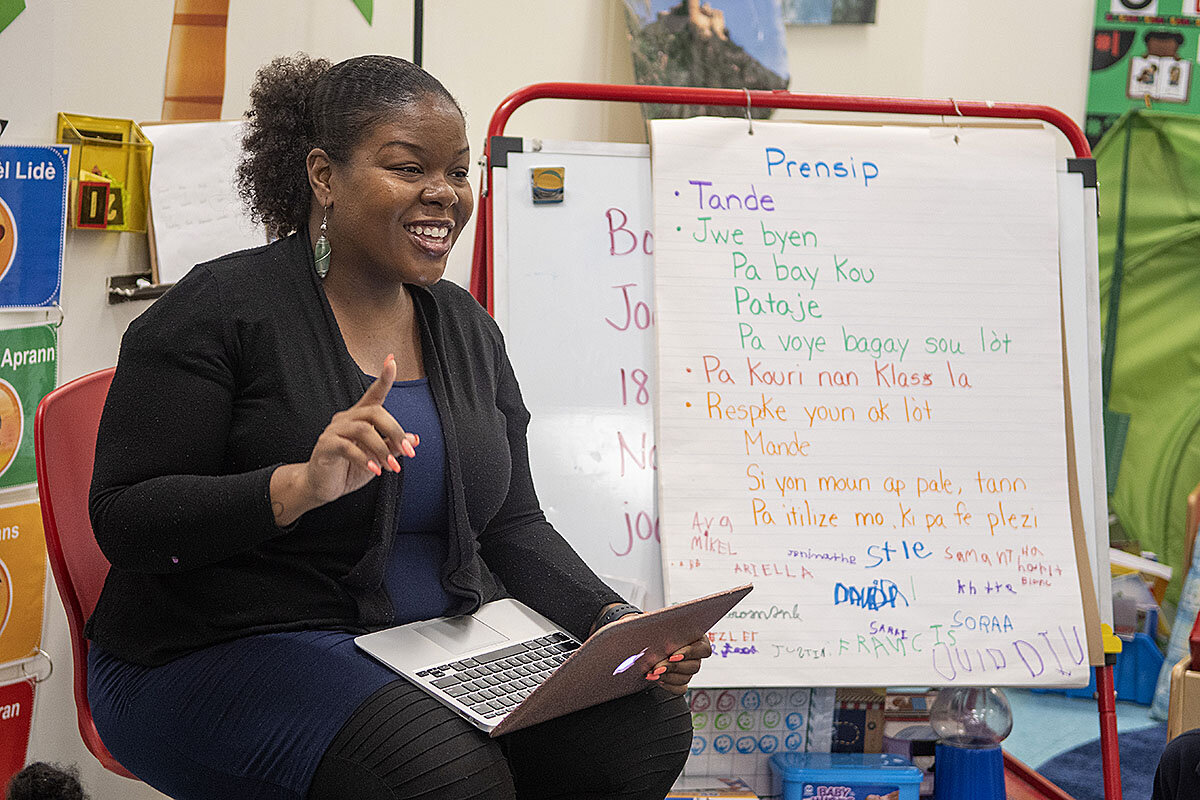

“Tonton Bouki!” shouts Priscilla Joseph, a kindergarten teacher at the Toussaint L’Ouverture Academy at Mattahunt Elementary School in Boston. “Eya eya!” her class roars back, swaying in a circle at the front of the classroom.

“N’ap mache!” Ms. Joseph calls out. “Mache konsa!” they reply, nearly falling over each other giggling. Tonton Bouki, the subject of their song, is a mischievous character in Haitian folklore.

The Toussaint L’Ouverture Academy is a one-of-a-kind bilingual kindergarten program here in Mattapan, an immigrant-dense neighborhood at the city’s southern border. It’s the country’s only Haitian Creole two-way dual immersion program at this level.

In Joseph’s class, Haitian and Haitian-American students mix in equal numbers with kids who have no direct connection to the Caribbean country. “No one is different here because they speak a different language,” she says.

With immigration debate at such a fever pitch in the United States, you might think bilingual education would be stalled. The usual routine, experts say, is like a pendulum: When support for immigration drops, so do funding and policies that bolster multilingual classrooms. And vice versa.

But despite some prominent anti-immigrant sentiment in the US, one form of bilingual education is actually gaining steam. Two-way dual immersion, which combines fluent English speakers with English language learners (ELLs) is taking off.

“These two-way programs with English-speaking kids are just exploding all over the country. Now it’s an advantage for the middle class, for English-speaking parents to have their kids in a program like this. So it has changed the dynamic,” says Patricia Gándara, professor of education and co-director of the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles.

That explosion of support signals a shift in how educators across the political spectrum think about multiculturalism. The traditional approach would take ELLs and drill down on language lessons until they could hold their own in English-only classes. Two-way immersion, on the other hand, celebrates students’ different cultural backgrounds – and sees a second language as an asset, not a burden. That line of thinking can lead to a powerful byproduct: cultural and racial integration.

“Two-way dual immersion programs do integrate kids ... It is a natural strength of those programs so long as it’s implemented well,” says Ilana Umansky, assistant professor of education and policy at the University of Oregon in Eugene.

Bipartisan appeal

The reason behind the new popularity is simple: Learning in two languages has important academic and economic payoffs. Research suggests that these two-way, dual-immersion programs, some of which have been around for decades, can lead to academic gains that eventually outpace those from peers. Studies also suggest that participation can help close achievement gaps between ELLs and native English speakers. And as demand for bilingual employees in the US grows, there’s now more incentive than ever to train a polyglot workforce.

Within the past two years, California and Massachusetts have both lifted restrictions on bilingual education programs. Only two states still have such measures – Arizona and New Hampshire – although bilingual programs are allowed with special permission.

But it’s not just blue states that are leading the charge on two-way dual immersion. States that are generally tough on immigration are joining in, too. “North Carolina has been ostensibly very anti-immigrant in a lot of its policies but at the same time,” the state is “one place where there’s a lot of growth in these two-way programs,” says Professor Gándara.

“So you see these interesting things happening at cross-currents,” she says.

Of 59 existing two-way dual immersion programs in the southern state, 22, or about 37 percent, launched in the past three years. The city of Dallas now has 56 two-way, dual-immersion programs. Utah has started more than 200 dual-language programs within the past 10 years, although most are one-way, in which all students are native English speakers.

Opponents of bilingual education often say it keeps immigrants and their families from learning English and assimilating. But with English-fluent students entering these classrooms, that argument is changing.

“Somebody like [Education Secretary] Betsy DeVos, if she’s looking at this issue of bilingualism as something that’s open to all kids and middle-class kids, she’s probably not going to get too involved in this … because there [are] advantages there for middle-class English-speaking kids, for nonimmigrant kids,” says Gándara.

As for assimilation, observers see changes there, too. In two-way dual immersion, “principals are reporting that [ELLs’] self-esteem is increased and then along those lines, that also allows the non-English parents to be more active in the school community,” says Stephen Kotok, assistant professor of administrative and instructional leadership at St. John’s University in New York.

Integrating classrooms, not just schools

Nancy Uribe, a third-grade teacher at the East Somerville Community School in Somerville, Mass., teaches in UNIDOS, a kindergarten through eighth grade Spanish two-way dual immersion strand of the school. The program is well established – it’s approaching its 20th anniversary next fall. Every year, Ms. Uribe’s students interview a friend or relative from a different country. Then the children present their research, and families come to watch and eat food from some of the featured cultures.

“I see these Anglo parents with a little bit of Spanish and these Latino parents with a little bit of English eating pupusas and trying to communicate with body language ... and to see that connection is wonderful,” says Uribe.

“The students,” she continues, “they already have it.”

UNIDOS is the only two-way dual immersion program in Somerville, a dense city just north of Boston with a substantial Latino population. Spanish is in the air here – at bus stops and Mexican restaurants along its main street. But as Boston housing prices climb upward, an influx of English-speaking commuters is reshaping the city’s linguistic diversity, and its school district.

At UNIDOS, the mostly even mix of Latino and non-Latino students spend half their time learning in English and half in Spanish, switching between subjects. Each grade has two bilingual teachers: one a native Spanish speaker and the other a native English speaker. A focus on equal representation helps correct for a problem persistent in even equity-minded monolingual schools.

“Even in successful kinds of racial integration programs a lot of times what happens is the schools look pretty racially diverse but then you walk into the school and the classrooms are not very diverse,” says Professor Kotok. “So that's where we were looking at dual language as it can move beyond that and integrate the classrooms.”

Often, schools take ELLs out of class to focus on English – sometimes for up to four hours at a time, as is the case in Arizona. “Spanish-speaking kids or whoever are being pulled out of their classes for their English instruction while their classes are learning math or learning science or learning history,” says Professor Umansky. “Those kids end up losing that content.”

Gentrification challenges

Two-way dual immersion isn’t a magic bullet for integration, say observers – especially in districts where growing English-fluent populations, who tend to be whiter and wealthier, tilt the community’s demographics.

And that’s where housing reform plays a vital role, explains Gándara. Without measures to keep the neighborhood affordable, the draw of a dual-language program can lead to gentrification. It’s something that Holly Hatch, principal of East Somerville Community School, thinks about often. Housing activists in Somerville have worked to keep property costs from skyrocketing, she says.

In Los Angeles, Gándara has noticed some families keen on getting in to two-way dual immersion programs have even bought houses in qualifying neighborhoods that they then rent out or leave empty while their children enroll.

To prevent ELLs from getting pushed out, schools should commit to maintaining diversity in their student body, says Kotok. Both UNIDOS and the Toussaint L’Ouverture Academy reserve seats for students at different linguistic levels. UNIDOS sorts students into three equally represented categories: English dominant, Spanish dominant, and bilingual. Waiting lists for all three groups are full.

“Districts need to be very clear on their goal of diversity because [pushing ELLs out] definitely is a risk and more fluent parents and native speakers try to hoard those seats,” says Kotok. “You’re not going to get the full academic and cognitive benefit if you don't have this balance in the classroom.”

Last year, Kotok and his colleagues made additional recommendations for two-way immersion programs hoping to achieve meaningful racial integration, including providing special training for bilingual teachers and securing structural supports for educators and families.

Cultural pride

There’s a subtle point about two-way dual immersion that parents and teachers at both schools often mention. These programs send a message to immigrant groups that their language and culture are valuable to the wider community.

“Here we all promote what a benefit it is to be able to read, write, and speak a different language and appreciate the differences between people and their cultures,” says Patrice Hobbs, another elementary teacher in UNIDOS.

At the Toussaint L’Ouverture academy, Joseph has noticed a similar powerful response to the formation of the school, now in its second year. For older members of Boston’s active Haitian community, seeing such a wide interest in the program has moved them.

“They were just so excited to hear that there were kids here in Boston that were learning Creole and some of them that were not even Haitian … And you literally saw their faces light up like, ‘Really?’ And I'm like, ‘Yeah, some of them are not even Haitian at all,’ ” says Joseph.

“Someone taking this much importance in [their] culture gave them a sense of pride,” she says.

This is story is part of an occasional series, Learning Together, on efforts to address segregation.

How Uganda’s school children became the keepers of the vine

In a nation where a majority relies on subsistence farming, improved crop strains can make a big difference. But getting fortified seedlings into the hands of farmers can require its own kind of revolutionary thinking.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

The sweet potato has always been an important crop in Uganda. But in recent years, the root vegetable has taken on heightened significance as a means of addressing malnutrition, food insecurity, and poverty. New strains of the crop, developed by Uganda’s National Crops Resources Research Institute, promise fortified nutritional value, increased drought tolerance, and higher yields. But spreading the word proved difficult. It was hard for government workers and sporadic volunteers to reach the nation’s small-scale farmers. So scientists at the research institute have recruited some unlikely ambassadors: local schoolchildren. The students learn to tend sweet potato vines in school before bringing them home to their families. In the first three years of the project, Ugandan schoolchildren distributed close to 22 million vines, increasing adoption by 10-fold over traditional methods of distribution. Farmers are hearing from someone they trust and who will be around throughout the growing season. “Whatever you tell children, they take the message to the parents,” says Grace Babirye, who is with a collaborating nongovernmental organization. “[M]others listen to their children.”

How Uganda’s school children became the keepers of the vine

Joan Nabadda’s school days in Kitagobwa are filled with reading, writing, and sweet potatoes.

The 7th-grader is one of 11,200 students in Uganda being trained as evangelists for improved strains of kipaapali, as the orange-fleshed tubers are known locally.

The sweet potato has always been an important crop in Uganda. The East African nation is the leading producer of sweet potatoes in Africa and second to China in the world. In recent years however, the root vegetable has taken on heightened significance as a means of mitigating malnutrition, food insecurity, and poverty. New strains of the crop, developed by the National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI) in Namulonge, promise fortified nutritional value, increased drought tolerance, and higher yields.

Distributing these new strains to the region’s far-flung small-scale farmers, the majority of whom are not connected to formal agricultural networks, has been a challenge. With limited number of government extension workers to distribute the vines, the government has relied on NGOs to educate farmers about growing practices. But those efforts have been sporadic, and adoption of these new varieties has been low.

In the past few years, however, NaCRRI has recruited school children like Joan to not only distribute these improved crops, but to teach their families as well.

In addition to their academic studies, students in 56 schools in the districts of Wakiso, Mukono, and Kamuli receive training in vine preservation, sweet potato agronomy, and disease identification and management, says Gorettie Semakula, a research scientist at NaCRRI and the team leader for the program in Uganda.

“The model was 10 times more successful than the other models,” says Dr. Semakula.

In the first three years of the project, Ugandan school children distributed close to 22 million vines in the districts of Wakiso, Mukono, and Kamuli. A companion program in Tanzania has distributed 50 million sweet potato vines in the same period, says Dr. Kiddo Mtunda, the program’s lead scientist in Tanzania.

The program has caught the eye of other scientists at NaCRRI. Dr. Stanley Nkalubo, who runs the institute's Legumes Research Program, has started deploying school children to distribute drought-tolerant and fortified bean seeds and to train farmers on growing practices. And Semakula has been talking with the NaCRRI's parent organization, the National Agricultural Research Organisation, about scaling up the program.

By teaching children to bring what they are learning at school home to their families, researchers have been able to reach areas that they otherwise may not have been able to, says Semakula. Nearly every village in Uganda has a primary school, and most families have at least one school-age child.

The model has not only enabled more efficient seedling delivery, it has also made distribution more equitable, says Grace Babirye, program director at Volunteers Effort For Development Concern Uganda, one of the collaborating NGOs engaged in agricultural extensions. In other programs, beneficiaries were likely to be friends or colleagues of extension workers.

Sending children as the messenger ensures that farmers are introduced to these new varieties from someone they trust and who will be around throughout the growing season, rather than a government worker who arrives for one day and never returns.

“Whatever you tell children, they take the message to the parents,” Ms. Babirye says. “[M]others listen to their children.”

In Kitagobwa, a village in Uganda’s Wakiso district, that idea is evident.

Joan was one of the first students at Kitagobwa Primary School to join the program. She was particularly interested in the new strain’s resistance to drought, an increasing problem in Wakiso.

“I was enthusiastic about learning about the new techniques of growing sweet potatoes, as we usually eat them during times of scarcity,” Joan says. “I was also interested in any skills that would help me improve on our income at home.”

By the time Joan brought vines home to her family she had gained hands-on knowledge of basic sweet potato agronomy, from planting to weeding to harvesting. She learned the art of hilling, the gathering of loose soil around the base of the plant as it grows to promote growth of the fleshy tubers beneath the soil.

Impressed by what her niece was learning, Joan’s aunt, Deziranta Nakisozi, accepted an invitation to visit the school to learn for herself. She had never before received any formal agricultural training.

Gesticulating toward the hilled mounds of earth around her, Ms. Nakisozi boasts, “Kipaapali yielded very well.”

Her neighbor in the field, Rebecca Nakakawa, has seen similar success since her daughter brought home kipaapali vines from school.

“The yields from the kipaapali are much better than our traditional variety,” she says.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Germany’s learning curve on immigration

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Tuesday’s elections did little to help Americans define a middle ground on immigration. Germany, too, has been convulsed on the issue. Yet it may soon hold a sober debate on the topic with an eye toward a centrist solution. The candidates vying to replace Angela Merkel as party chief of the Christian Democratic Union differ on what to do about migration, an issue that has heightened polarization since 2015, when a million Muslim refugees flooded into the country. But they know that consensus is needed. More than half of Germans say they feel like strangers in their own land, according to a new poll. Ms. Merkel herself has admitted mistakes in allowing the rapid influx of migrants without better preparing Germans. She has since struck deals with other countries to restrain the flow of people, and worked to assimilate new arrivals. As she slowly exits after 13 years in power, Merkel leaves a mixed legacy on immigration. But her learning curve on the topic has prepared her party, and perhaps all of Germany, to tone down the rhetoric of fear, and to come together.

Germany’s learning curve on immigration

Tuesday’s elections in the United States did little to help Americans define a middle ground on immigration. Perhaps they should take a cue from another big democracy, Germany. It has been equally convulsed on the issue. Yet it may soon hold a sober debate on the topic with an eye on finding a centrist solution.

Since 2015, when a million Muslim refugees flooded into the country, German politics has become more polarized. The far-right, anti-immigrant party Alternative for Germany has gained strength. So has the pro-immigrant Green party. Traditional parties in the middle, especially the dominant Christian Democratic Union, have started to lose local elections.

In October, those losses finally forced CDU leader Angela Merkel to announce her departure as party leader next month and eventually as Germany’s leader. The three candidates vying to replace her as party chief differ on what to do about migration. Yet they also know the country must find a consensus.

“We need to work out a way for people here to feel at home – people who have lived here a long time and people who have arrived more recently,” said one of the candidates, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, on Nov. 7. She added that the rest of Europe, which has also seen the rise of anti-immigrant parties, must join in the effort. “The question of how to protect ourselves from [migrant] criminals is not one we can answer in Germany alone,” she said.

The centrist parties feel some urgency. More than half of Germans now say they feel like strangers in their own land because of Muslim immigration, according to a new poll from the University of Leipzig. That is a big shift from before the 2015 refugee crisis. One in 3 believe foreigners come to Germany only for its generous welfare system. Close to half want a ban on Muslims moving to the country.

The other two candidates, corporate lawyer Friedrich Merz and health minister Jens Spahn, are more conservative than Ms. Kramp-Karrenbauer yet do not want to rip the party apart over the issue. “You don’t win people’s confidence in security with harsh tones, with shrill demands,” said Kramp-Karrenbauer, who is Ms. Merkel’s chosen favorite to replace her.

Merkel herself has admitted mistakes in allowing the rapid influx of migrants without better preparing Germans. She has since struck deals with Turkey and other countries to restrain the flow of people. And she emphasizes stronger efforts to assimilate new arrivals in learning German and accepting basic values, such as equality for women.

As she slowly exits after 13 years in power, Merkel leaves a mixed legacy on immigration. But her own learning curve on the topic has prepared her party, and perhaps all of Germany, to tone down the rhetoric of fear and come together, as Kramp-Karrenbauer put it, to value “the binding above the divisive.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Remembrance without grief

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Joan Bernard Bradley

When the younger sister of today’s contributor died unexpectedly, the idea of “praying without ceasing” brought a tangible sense of God’s love, instead of the darkness of grief.

Remembrance without grief

One Saturday, a relative brought me some urgent news – my younger sister had unexpectedly passed away. It was a shock to hear this.

That day, I was in my neighborhood Christian Science Reading Room, which I’d found to be a spiritual refuge since first learning about Christian Science some years before. I’d spent many hours there being fed spiritually, using its vast selection of spiritual resource materials to aid me in my Bible study. One verse had recently leapt off the page at me: “Pray without ceasing” (I Thessalonians 5:17). Right then, I’d made a private commitment to strive to do that to the best of my ability.

When I heard about my sister, whom I loved dearly, the urge to grieve loomed over me. But I found hope in this idea of praying without ceasing – of “hold[ing] fast that which is good” (I Thessalonians 5:21), or actively acknowledging God’s ever-present goodness. Turning wholeheartedly to God, who is infinite Love, I affirmed in my prayers that divine Love was the source of my strength and would show me how to respond appropriately to the events to come. I also leaned on this verse from the Bible: “It is God that girdeth me with strength, and maketh my way perfect” (Psalms 18:32).

Searching for a deeper understanding of these words, I discovered that one meaning of “strong” is “having great force of mind.” Christian Science explains that Mind is a synonym for God, who creates and knows only peace, life, and joy. I saw that I could rely on the force, or power and presence, of divine Mind to lift my thoughts above the dark sense of death, misfortune, and loss.

During the days that followed, I pondered the explanation of creation given in the first chapter of the Bible, where God, divine Spirit, “saw every thing that he had made, and, behold, it was very good” (Genesis 1:31). This helped me see that what constituted my sister’s true identity were God-reflected, spiritual qualities – qualities such as the kindness, vitality, generosity, and motherly love that I had always appreciated in her. This identity originates in God and therefore cannot be lost or destroyed. On the contrary, these qualities live forever and can be felt in our hearts and thoughts even after someone we love has passed on.

When family and friends gathered to remember my sister’s life, we took turns sharing our favorite memories of “C,” as she was affectionately called. The stories shared were filled with joy and laughter. Treasuring these precious memories of how she expressed herself as the loved child of God had a healing effect. While there were still tender moments when I missed my sister, I can honestly say that I was free from deep grief and have remained so. Instead, I felt filled with a conviction that life cannot truly be lost.

Jesus instructs us, “When thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret; and thy Father which seeth in secret shall reward thee openly” (Matthew 6:6). Mary Baker Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, explains, “The closet typifies the sanctuary of Spirit, the door of which shuts out sinful sense but lets in Truth, Life, and Love” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 15).

Each of us can have a “sanctuary” experience as we hold steadfastly to the spiritual fact of Spirit’s allness and goodness. The effect is a tangible sense of God’s love and comforting presence, bringing us peace and freedom from emotions and thoughts that are unlike God, good.

A message of love

A somber anniversary

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow. We’ll have a report from the Florida Panhandle, where our reporter found that the headlines moved on much sooner than people’s need for help.