- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- From hemp to organic foods, farm bill embraces change in rural US

- The ‘ballot broker’: North Carolina race puts face on electoral fraud

- My hometown schools have resegregated. I went back to see why.

- Why an Argentine leader seeks to break the pull of populism

- How one author illustrates gratitude – on the page and in life

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Theresa May’s curious polling numbers

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

These have been trying times for British Prime Minister Theresa May.

From the day she took office, her charge was daunting. Some called it “an impossible brief.” As leader of the Conservative Party, she had to maintain the enthusiasm of those who voted for Britain to leave the European Union next March. As prime minister, she had to figure out how to engineer that divorce without chaos or significant damage to the British economy.

No one much likes the plan she’s devised. A November poll showed only 19 percent support. Conservatives don’t like it any more than the Labour opposition, and today she faced a vote of no confidence from members of her own party in Parliament. She survived, but it was hardly a ringing endorsement. To top off a tough week, she got locked in her own car Tuesday when trying to meet with German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

And yet Ms. May’s approval ratings have gone … up. Not enormously (they’re still only at 35 percent), but still conspicuously. There is, it appears, some appreciation among voters for the spot she’s in – and for how she’s conducted herself during a trying time. As one commentator told NPR: “She’s dogged. She’s determined. She’s got a real sense of duty…. In the end, people quite respect the fact that she’s still there and she’s still standing.”

Now here are our five stories for you today. We take a look at the need for the United States to look inward to safeguard elections, we share a personal perspective on segregation, and we explore the touching lessons of an author and illustrator.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

From hemp to organic foods, farm bill embraces change in rural US

Passage of the farm bill is a rite of Congress that often borders on the arcane. But this year’s version signals how American farming is gradually embracing a vision beyond the industrial model.

To some degree, Congress’s periodic review of agriculture programs tends to be more about continuity than change. This year’s follows the pattern, avoiding big cuts to food stamps and helping Farm Belt communities weather a multiyear decline in income. But the five-year farm bill also embodies more than its share of new thinking. A 1937 ban on growing industrial hemp, a non-hallucinatory form of marijuana, will be lifted, assuming the bill is signed into law as expected. The measure also has initiatives that boost organic farming, crop diversity, and advanced conservation methods. And in a separate sign of the times, McDonald’s said Tuesday it’s aiming to reduce its use of beef raised on antibiotics. As a result, Americans are likely to see more diversity in crop production, more help to organic farmers and farmers markets, and more experimentation with advanced cropping and grazing methods that improve soil and water quality. That doesn’t mean the bill is a U-turn against the factory-farm model. But Alyssa Charney, of the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, says “there are definitely policy gains.”

From hemp to organic foods, farm bill embraces change in rural US

Every five years or so, Congress passes a farm bill, which offers a peek into the future of agriculture.

This year’s bipartisan version, while mostly aimed at stabilizing the status quo, nevertheless offers changes and new initiatives that boost organic farming, crop diversity, and advanced conservation. And for the first time in decades, it allows US farmers to produce industrial hemp, a non-hallucinatory version of marijuana.

The Senate passed the compromise bill 87-13 on Tuesday, and the House followed suit Wednesday with a 369-47 vote.

Separately, McDonald’s, the nation’s largest purchaser of beef, announced Tuesday it was aiming to reduce its use of beef raised on antibiotics.

Together, these moves suggest that commercial agriculture is expanding beyond a factory model of farming to embrace more geographically and environmentally sensitive approaches to producing food and fiber. As a result, Americans are likely to see more diversity in crop production, more help to organic farmers and farmers markets, and more experimentation with advanced cropping and grazing methods that improve soil and water quality.

“The farm bill is becoming more flexible to provide a reasonable amount of support” to farmers, says Dale Moore, executive vice president of the American Farm Bureau Federation in Washington and former chief of staff at the US Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Mostly, the legislation is aimed at helping farmers deal with a multiyear decline in income – as well as maintaining SNAP benefits (food stamps) for 38.6 million low-income Americans. But beyond that, the bill includes some innovations that should begin to influence the way the United States produces food.

Hemp for consumer products

One of the most striking changes in the farm bill is the move to allow the production of industrial hemp. Outlawed in 1937, at least in part because of its close connection to other marijuana species, the commodity has gained renewed interest, especially in tobacco-growing areas such as Kentucky and North Carolina, where the plant thrives.

Though hemp fibers can be used to create clothing and other products, market analysts expect the biggest growth to come from hemp-derived cannabidiol, or CBD, which is used in health and wellness products such as supplements. Operating in a legal gray area, the CBD market has already grown to $590 million, says Bethany Gomez, director of research at Brightfield Group, a research firm based in Chicago. “We expect by 2022, with this full legalization, [for] that market to hit $22 billion.”

The bill continues Congress’s move away from providing money to grow specific quantities of crops and instead helps to reduce farmer risk by subsidizing crop insurance. This year’s farm bill extends that support to the dairy industry, which has been struggling with low milk prices, and to second-tier crops, such as barley, which can be used to feed livestock or as a cover crop during the winter – a nod to growing concerns about soil degradation from traditional farming.

The bill also increases support to organic farming by establishing permanent funding for research to the tune of $50 million a year by 2023, up from $20 million. It also funds research for organic farming challenges and relieves some of the costs for small and beginning farmers to get certified organic. The Organic Trade Association called the provisions “an historic milestone” in a statement Tuesday.

Other support for small-scale farming includes permanent (it was temporary in the prior farm bill) funding for promoting local farmers markets.

Give-and-take over conservation

For sustainable farming groups, the House-Senate compromise bill represents more of a mixed bag. They are relieved the final bill did not include a House measure that would have eliminated the Conservation Stewardship Program, which helps farmers expand their conservation practices. But funding for the program will be cut so that by 2023 the program will get $800 million a year less than what it got in the last year of the previous farm program.

Nevertheless, there will be more money for farmers using advanced conservation practices, such as growing cover crops (reimbursed at 125 percent of the farmer’s costs) and resource conserving crop rotations and advanced grazing practices (both at 150 percent of costs). The new bill also establishes a Clean Lakes, Estuaries, and Rivers (CLEAR) Initiative, which is aimed at protecting drinking water and waterways from pesticide and fertilizer runoff.

“It's not black and white,” says Alyssa Charney, a senior policy specialist for the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, a Washington-based alliance of grass-roots sustainability groups. “There are definitely policy gains.”

From McDonald’s, ‘progress’ on antibiotics

The McDonald’s announcement that it will restrict its use of antibiotic-fed beef represents a big win for consumer advocates of natural food, who had already pushed McDonald’s and major poultry producers to stop the practice with chicken. The fast-food chain said it will begin monitoring the use of antibiotics in the US and nine other nations that supply most of its beef. By 2020, it will set reduction targets.

“This is progress, but we still have a ways to go,” says Matthew Wellington, antibiotics program director for U.S. PIRG Education Fund, a nonprofit that works for consumers and the public interest. Some 70 percent of antibiotics used for human health actually go to farmers, who feed them to their livestock and poultry to speed their growth. “In five years, the industry will start to move away from antibiotics for animals,” he adds.

Of course, neither CEOs nor legislators can foresee everything.

“Things change,” says Mr. Moore of the American Farm Bureau Federation. The last farm bill, for example, didn’t imagine that US farmers, especially soybean and pork producers, would be reeling from a trade war with China.

That is the reason the new bill combines some existing export-promotion programs. “The money is not significantly more, but the secretary [of agriculture] has been given some flexibility” to create new markets for US farm goods, Moore says. “It gives us some hope” that the US can begin to make up for the potential loss of Chinese markets.

Bailey Bischoff contributed to this report from Washington.

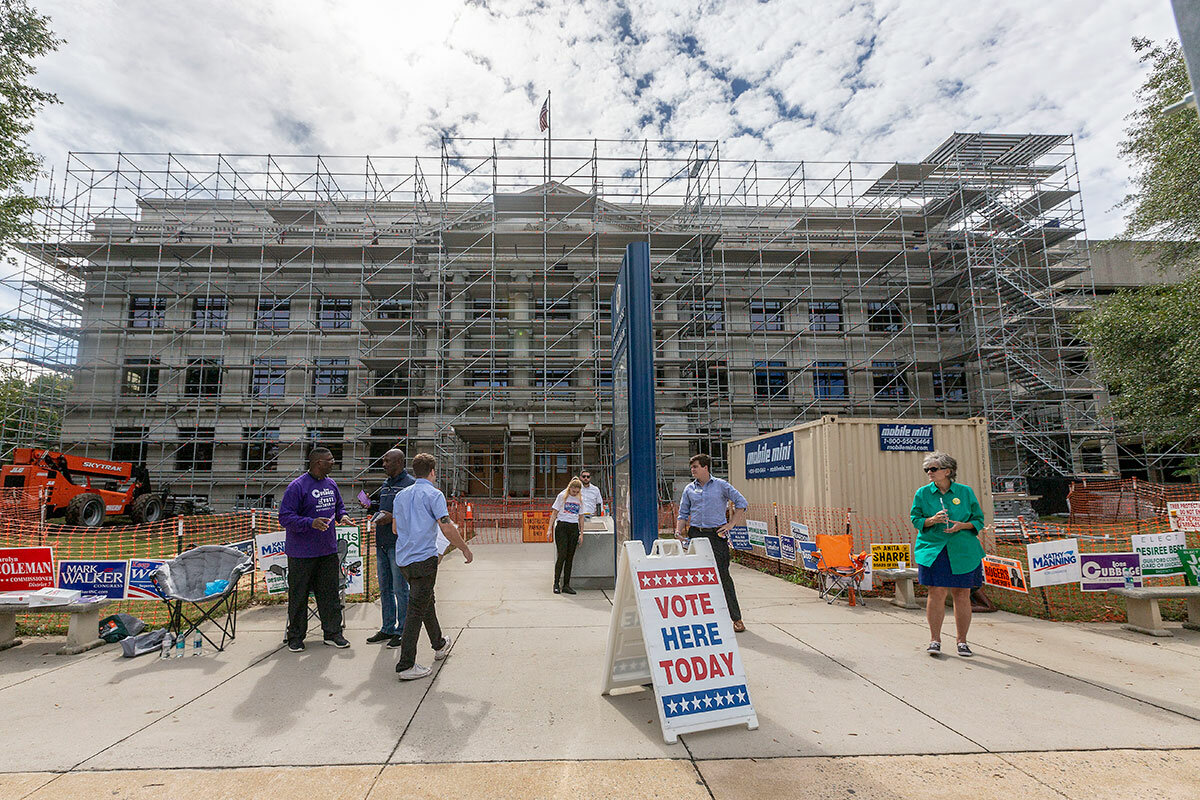

The ‘ballot broker’: North Carolina race puts face on electoral fraud

The United States has focused a lot in recent years on manipulation of its elections by outsiders. But an unfolding story in North Carolina suggests the need to demand honesty and transparency at home, too.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

It wasn't federal investigators but number-crunching academics and local journalists who unearthed the facts in North Carolina’s Bladen County. There, a team apparently run by a convicted fraudster illegally collected absentee ballots and, potentially, tampered with them or tossed them in the garbage. The fraud allegations come at a moment of greater concern over US election security. In fact, eight in 10 Americans are at least somewhat concerned about people hacking the country’s voting systems, according to an Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research study published last month. In that way, the election fraud scandal in North Carolina may supply new clarity regarding the true dynamics of election manipulation in the US – while, perhaps, adding urgency to how it can be more capably curbed. “This case in North Carolina demonstrates where there are some real problems, as opposed to fears of voter fraud,” says Barbara Headrick, a professor who studies the intersection of law and politics. “This is not about people trying to vote illegally. This is people who are trying to legitimately use their franchise who are then having it taken by an organized effort in favor of one candidate – by changing votes, by stealing them.”

The ‘ballot broker’: North Carolina race puts face on electoral fraud

A country still dealing with potential election interference by foreign agents is now facing a home-grown scandal: credible and bipartisan allegations that a small-town operator in rural North Carolina used illicit means to swing a 905-vote win for a Republican House candidate.

A bipartisan elections board in North Carolina unanimously declined to certify the Ninth District election last week after “unfortunate activities,” in the words of the board’s vice chair – apparent mass-manipulation of absentee ballots – came to light.

On Tuesday, the story grew even deeper. Affidavits suggest that Republican officials shared early voting data with partisans while withholding that information from Democrats. The debate has now shifted from whether one operator’s actions affected the results to whether the entire proceeding is so tainted that a new election is necessary.

While the state has until Dec. 21 to either certify or call for a “re-do,” Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi has suggested that a Democrat-controlled House may refuse to seat Republican Mark Harris until the irregularities are fully exposed and resolved.

To be sure, election experts say county-level electoral fraud is part of a long American tradition, especially in the South, that carries on to this day. It tends to occur in barely watched elections in remote, often poor regions where ballot corruption can offer spoils like power and cash.

But the fraud allegations come at a moment of greater concern over US election security. In fact, eight in 10 Americans are at least somewhat concerned about people hacking the country’s voting systems, according to an Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research study published last month.

In that way, the election fraud scandal in North Carolina may supply new clarity regarding the true dynamics of election manipulation in the US – while, perhaps, adding urgency to how it can be more capably curbed.

“This case in North Carolina demonstrates where there are some real problems, as opposed to fears of voter fraud,” says Barbara Headrick, a professor at University of Minnesota, Moorhead, who studies the intersection of law and politics. “This is not about people trying to vote illegally. This is people who are trying to legitimately use their franchise who are then having it taken by an organized effort in favor of one candidate – by changing votes, by stealing them.”

Number crunching, old-fashioned journalism

As America learns through investigations into the 2016 election more about shadowy forces tugging at US elections, number-crunching academics and shoe-leather journalists unearthed the facts in Bladen County. There, a team apparently run by a colorful convicted fraudster illegally collected absentee ballots and, potentially, tampered with them or tossed them in the garbage.

In that way, the NC-9 race puts a believably human face to fraud: Faulkneresque characters working the countryside as “ballot brokers,” threading the legal needles of the absentee ballot system, skipping a few ethical stitches along the way.

When searching through data, Catawba College political scientist J. Michael Bitzer discovered that 19 percent of mail-in absentee voters in the county were registered Republicans. However, 62 percent of the total absentee vote went to the Republican candidate. Bitzer had never seen such an anomaly. And shoe-leather reporting by TV reporter Joe Bruno in Charlotte put faces to the claims. On Wednesday, WECT 6 reported that Kenneth Simmons of Robeson County signed an affidavit saying he and his wife saw operative Leslie McCrae Dowless Jr. holding more than 800 absentee ballots outside a campaign event. (In North Carolina, it is illegal for anyone other than a direct family member to turn in a ballot for someone.) “The way I look at it, I don’t care if you are Republican, unaffiliated, or Democrat. I want it fair,” Simmons told WECT 6.

“In a small county like Bladen, if this had not been a competitive congressional contest, probably nobody would have picked up on this, to be candid,” says Dr. Bitzer, who published the anomalous data on his blog. “[Absentee-ballot manipulation] happens in small races, sheriff’s races, a variety of different environments,” he says. Given the impact, “this will probably force a reevaluation of procedures in North Carolina. But my bigger concern is how you can ultimately stop human behavior if we are at the point of winning at any cost, which is where our polarized partisanship is at, at this point.”

Bipartisan concern

North Carolina is already helping to answer that question. At first Republicans threatened to sue if the board didn’t certify the results. But as more details have come out, the state is moving closer to holding a special election in 2019, potentially including a new primary. Revelations that county election officials shared early voting data with Republicans only underscore how the fraud may extend beyond a paid vote broker to pure government corruption, one key Republican said.

“This action by election officials would be a fundamental violation of the sense of fair play, honesty, and integrity that the Republican Party stands for,” North Carolina GOP chairman Robin Hayes said in a statement issued Monday, saying if true, the allegations would warrant a new election. ”We can never tolerate the state putting its thumb on the scale.”

His dismay resounds. Voters across the US have focused on bipartisan efforts to shore up the vote, in several states by curtailing political gerrymandering that creates safe districts for the party in power – a fount of partisan distrust across the US. Missouri is about to hire its first ever state demographer tasked with drawing more equitable districts.

On the other hand, Republican-led states have acted primarily to prevent in-person voter fraud by passing ID laws. States like Colorado and Washington mail every voter a stamped mail-in ballot. Safeguards in the system have largely prevented fraud in those states, election observers say.

The NC-9 election “is indicative of fraud in a sense, because it is so hard to commit widespread fraud that you usually see it in onesies or twosies, or in larger amounts on the edges of the electoral system,” says Charles Stewart III, a voting technology expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass. “Often the fraud has become financially advantageous to somebody, and they are willing to risk it because they feel like the rest of the world isn’t paying attention.”

In the Tar Heel case, however, the ruse was bound to be discovered, he says. “North Carolina is incredibly transparent, so if you are going to do something squirrelly it’s going to be noticed – especially if you do something squirrelly at the scale that you think it might affect a congressional election.”

Vote-buying scandals

The South has a historical tolerance for such malfeasance, Bitzer says.

Kentucky had vote-buying scandals up into this decade. Alabama faces perennial county election scandals, oftentimes featuring intra-party Democratic corruption in rural majority-black counties. And the biggest vote-buying scandal in US history came in the late 1990s out of rural Georgia, where a rite of passage for turning voting age had long been to receive cash for one’s first vote, according to the FBI.

“In Southern politics there has always been a strong relationship between county politics and walking-around money,” says Bitzer at Catawba College. “Even with the Voting Rights Act and other measures to protect the vote, human nature is very much prone to corruptive influences, and the South at times can be a leader in that particular mentality.”

The scope of the problem goes beyond the South, from county operatives to geopolitical scoundrels in front of computer screens. But it also shows how vigilance on the part of the voting public and bipartisan referees makes decisive election fraud difficult to pull off.

“[Ballot manipulation and vote influencing] is about poverty and marginality,” says Professor Stewart at MIT. “Even in the 19th century where you saw efforts to buy votes, it’s going to be poor people who are ... subject to these sorts of temptations. It involves people preying on somebody’s lack of knowledge of the laws, or that a payment of $10 might actually be worth their while to skirt the law.

“In other words, if you don’t feel an investment in the vote to begin with, then it becomes a means toward another end. That’s the story here. And it happens in cities in the North, it happens in rural areas. You don’t need to be playing the theme from ‘Deliverance’ to believe that something like this might be happening in your hometown.”

Learning together

My hometown schools have resegregated. I went back to see why.

Thirty years after the peak of school integration nationwide, that progress has unraveled. But the outcome in Buffalo, N.Y., could offer lessons on America’s pressing need to address racial separation. Part of an occasional series, Learning Together.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

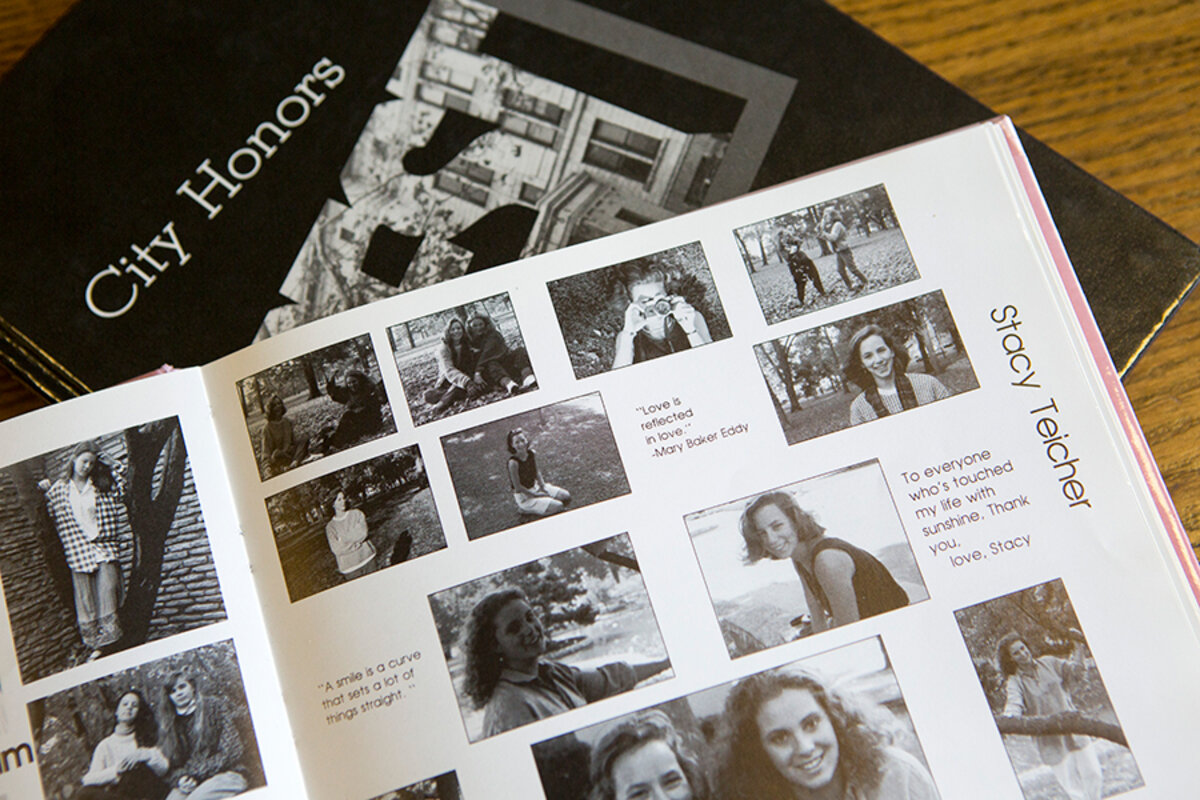

When Buffalo, N.Y., began desegregating its schools, my parents signed me up to take a bus to a new magnet school downtown. My K-12 years, 1976 to 1989, perfectly paralleled the rise of a national model for integration. Now, nearly 30 years later, the schools are in some ways as segregated as they ever were. When I came across this information as an education reporter, my heart sank. I had been largely out of touch with Buffalo since my parents relocated in the early 1990s. Had it really so drastically changed? Why was my public high school, City Honors, the subject of a civil rights complaint in 2014 for racial disparities in its selective admissions process? As I’ve focused much of my reporting this year on how communities are responding to a national trend of resegregation, I had to understand better what’s been happening in my hometown. What I found was a familiar can-do attitude among Buffalonians – and a lasting legacy from the desegregation era. Despite longstanding struggles with racism and poverty, and a need to do much more, creative approaches are percolating in a city now infused with new investments and a diverse array of newcomers.

My hometown schools have resegregated. I went back to see why.

In the fall of 1976, I started kindergarten by climbing onto a yellow school bus that wove its way through my tree-lined North Buffalo neighborhood and deposited me downtown near the edge of Lake Erie.

Waterfront Elementary – a new Brutalist-style building made of corrugated concrete – was anything but brutal on the inside. We had a swimming pool, a dance studio, and open classrooms where children from all over our otherwise segregated city came together to learn.

It was the first year of Buffalo’s new magnet-school program – part of the response to a federal court order to desegregate. The “magnets” drew families into schools voluntarily to contribute to racial balancing.

My best friend in elementary school was biracial and lived in the mostly black subsidized apartment complex next to Waterfront. When I visited Sondae Stevens’s place, she’d dare me to climb up with her on the low-slung roof of the school. When she visited mine, she enjoyed the novelty of playing in an attic. Our quirky personalities just clicked.

While we progressed through the grades, the magnet system grew into a national model. Before the desegregation order, 7 out of 10 Buffalo public schools were segregated – meaning more than 80 percent white or 80 percent minority. By the mid-1980s, that was down to 4 out of 10. The peak of school integration nationwide happened around 1988, when I was starting my senior year of high school.

It took less than 25 years for that progress to unravel. By 2012, some 70 percent of Buffalo schools were once again segregated. Courts had lifted many integration orders (including Buffalo’s) in the 1990s. Subsequently, a series of Supreme Court decisions limited the tools school districts could use to racially integrate.

On top of that, City Honors – a school for Grades 5 through 12 that I started attending in ninth grade – had become the centerpiece of a civil rights complaint in 2014, focused on the low rate of African-American students admitted to Buffalo’s selective schools.

When I came across this information as an education reporter, my heart sank. I had been largely out of touch with Buffalo since my parents had relocated in the early 1990s. Had it really so drastically changed?

“What’s at stake for Buffalo is equity and justice,” Jennifer Ayscue told me in a phone interview last spring. She visited with a team from The Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles to craft recommendations after the 2014 complaint, and co-edited a new book about it. “The district ... regressed and resegregated ... [but] with political will, they could really make great progress and have more equitable schools,” she said.

I had always been proud of attending integrated public schools. The “integration generation” I belonged to isn’t immune from prejudice, but many of us feel as if our experiences better equipped us to combat it.

My African-American friend Ursuline Bankhead, who graduated with me in 1989 (and has since seen her daughter graduate from City Honors), puts it this way: “We ate together, we broke bread together, whether it was on a trip or in each other’s homes. There’s a certain level of intimacy that happens when you share a meal.”

But if I tested my rather nostalgic view through my reporter’s lens, what would the story look like?

I know long-standing patterns of racial discrimination require sustained effort to undo – and Buffalo has long been one of the most segregated metro areas in the nation.

The arc from desegregation to resegregation here mirrors what has been going on across the United States for decades. Many urban school districts that integrated in the 1970s and ’80s, through busing and other controversial methods, slowly retreated in the backlash – and demographic changes – that followed.

So I set out to see what was happening in the school system I attended – and whether Buffalo might once again hold lessons for one of the most pressing problems facing urban America: how to find creative ways to cut down on students’ racial and economic isolation, and the unfairness those conditions have historically produced.

***

While I was trotting off happily to Waterfront, Samuel Radford III was starting sixth grade. His dad had signed him up to bus from black East Buffalo to white South Buffalo, where he attended Hillery Park Elementary.

In the neighborhood, “people were not happy to have us,” Mr. Radford recalls as we stand outside the school, across from a low stone wall defining a quaint park.

Some locals threw rocks at the bus or chased black students down the street if they stuck around for after-school activities. “School went from this fun place to this tense place,” he says, and although he did fine academically, “it just was a struggle.”

Statistics show that African-Americans who attended integrated schools in the US in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s had better outcomes than those who did not, and the benefits persisted among their children and grandchildren. Isolating the effects of integration for that first generation shows that it “led to an increase of a full year of educational attainment, increased earnings by one-third, and ... large reductions in both the annual incidence of poverty and the likelihood of incarceration in adulthood,” Rucker Johnson, a University of California, Berkeley professor and author of the forthcoming book “Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works,” tells me in an email.

But in talking with Radford, it’s clear that black students paid a price for those benefits that I as a white student didn’t.

I met up with Radford because he’s organized parents in Buffalo to fight for educational equity, and he helped file the 2014 complaint. He’s also president of the District Parent Coordinating Council (DPCC), a group that aims to hold the school system accountable.

He’s a warmhearted man who loves to take selfies. Today, he’s decked out in a maroon plaid sport coat and diamond-patterned tie, and he slips on his sunglasses as he drives. Earlier I had looked at color-coded maps showing white and minority neighborhoods, the economic gaps between them, and historic examples of “redlining” that restricted investment in minority areas of the city. Now, as we’re driving, I can see the markers of racial inequality in three-dimensional reality.

The farther we get from Main Street going east, the fewer trees and the more dilapidated buildings we see. We drive on an overpass with railroad tracks below, and he announces that this is the line that divides the East Side from South Buffalo, home of manufacturing jobs and union halls – and still a place to which some black residents don’t feel safe venturing.

My childhood friend Ursuline, like me, has fond memories of her school days. But it isn’t difficult for her to call up incidents of racial bias.

We both attended a “gifted” magnet program at Olmsted (a middle school that has since moved into two buildings to span prekindergarten through 12th grade). When we applied to City Honors for ninth grade, Ursuline recalls, the white principal at Olmsted “told me I was not smart enough to get in.”

Ursuline went home crying, but she tested so well that she got in even without the principal’s recommendation. “Every time I would run into [that principal] in public,” she says, “I’d be like, ‘Yes, I got into City Honors. Yes, I got into Penn State. Yes, I have my master’s degree.’ ”

Wendy Mistretta, a white City Honors parent on the DPCC, tells me a more recent anecdote: A friend of hers, one month into teaching young kids at an East Side school, told her that because so few could read at grade level, “we should stop telling them they should go to college.”

After the 2014 discrimination complaint, the district dropped teacher recommendations from the admissions criteria for selective schools, and it’s been conducting training with staff to combat implicit bias.

***

A culture shift is under way to foster higher expectations and equity in the city’s classrooms. It has come in part since Kriner Cash, superintendent of Buffalo Public Schools, took the helm in 2015, Dr. Mistretta and others say.

A “community schools” partnership now engages thousands of students and parents in after-school and Saturday activities in their neighborhoods. The program strives to offset the “extraordinary needs” Superintendent Cash has identified as affecting 9 out of 10 students – ranging from homelessness and trauma to a variety of mental and physical health issues.

New innovative high school programs stimulate students’ interests in promising local career paths. Test scores have been on the rise. And the percentage of students graduating within four years, which barely broke the mid-50s for about a decade, recently rose to 63 percent.

The Say Yes to Education program is also providing many families with new hope. Its college scholarships cover any tuition that Buffalo public school graduates can’t pay through other means. “We’re inching along in terms of progress,” Radford says.

We stop by the steps leading up to City Honors School at Fosdick-Masten Park. That’s the formal name of the massive 1914 building made of white-glazed terracotta, which sits atop a hill a few blocks east of the Anchor Bar on Main Street, where a national culinary staple – Buffalo wings – originated.

Radford tells me there’s still progress to be made when it comes to minority representation at City Honors and Olmsted, widely considered the city’s gems. At City Honors, for instance, blacks represented 31 percent of the student population in 1999 and now stand at just 16 percent. Currently, the school is 57 percent white.

In the district schools overall, by contrast, nearly half the 31,000 students are black and only 20 percent are white. Another 20 percent are Hispanic, and the remainder are Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, or multiracial.

Radford’s youngest son attends City Honors, but Radford isn’t satisfied with just his own child having that opportunity. He wants more to be done to counter the “very strong forces that have been around for a very long time in trying to maintain the status quo,” he says.

***

One way Buffalo schools are slowly improving outcomes is by focusing on the young. A few blocks from City Honors, the Stanley M. Makowski Early Childhood Center stands as a place where disadvantage meets opportunity, where shimmers of brilliance emerge despite low average test scores.

On this day, Ming Yu is teaching third-graders Mandarin by concentrating on phrases related to time. When a boy constructs the Mandarin equivalent of “I get up at 6 in the morning,” Ms. Yu gives him a high-five.

The student population at the Makowski Center, which teaches children from pre-K to fourth grade, is about 70 percent African-American. But it attracts young people from around the city with its International Baccalaureate Early Years curriculum, which strives to infuse 21st-century skills and global perspectives. Test scores at the Makowski Center have been rising, but still fewer than 20 percent of the students score proficient in English and math.

The district recently won a $1 million grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to phase in better teaching methods and expand enrichment opportunities instead of reserving them for “gifted” students. To address accusations of discrimination regarding admission to the district’s more selective schools, officials hold parent meetings to spread awareness about a test to try to qualify for Olmsted or City Honors. They have also made it convenient by offering the test at each school during school hours; previously it took place on a Saturday at a central location.

As a result, the number of district students taking the exam for fifth- or ninth-grade entry into City Honors and Olmsted has increased more than 10-fold. This fall 90 out of 141 Makowski fourth-graders took the test.

In one wing of Makowski’s cathedral-ceilinged building, Patricia Spasiano leads fourth-grade students through a lesson on complete predicates. “This is a conflict-free zone, right?” she reminds a few who are arguing, and then affirms, “You’re doing an awesome job.”

A tacked-up handwritten list of vocabulary words from a recent reading of “My Brother Martin” catches my eye. The first word: “Segregation – keeping two groups of people apart.”

The words “segregation” and “integration” don’t currently figure much into policy discussions related to education in Buffalo. The formal system that existed to racially balance schools no longer remains, but the value and belief system behind it “has stayed with us to this very day,” says William Keresztes, the district’s chief of intergovernmental affairs, planning, and community engagement. Students aren’t simply assigned schools based on where they live, but have choices throughout the city. In fact, many schools here roughly reflect the racial breakdown of the overall population that attends district schools.

Yet by some measures they are still segregated because, while students of color make up 80 percent of the school district, the city’s population of 260,000 is 48 percent white and Erie County is 80 percent white.

For a host of reasons, many families in Buffalo have chosen not to send their children to district schools. Roughly 9,000 students in the city attend private, parochial, or charter schools (public schools that operate independently from the district).

Some of these families tend to opt back in if their kids gain admission to Olmsted, City Honors, or a few other top-choice district schools. Such families, usually white, have been better at maneuvering within a system that often advantaged them, even if inadvertently. Many, for instance, would have their kids take the entrance exam and if they got in, the family would move into the district so the kids could attend the select schools. As a result, a few years ago 60 percent of students entering City Honors and Olmsted came from private, suburban, or other schools outside the district, Dr. Keresztes says.

The situation has prodded officials to have “honest discussions about race,” he says. “The purpose of City Honors is not to create an enclave for white families.”

The city has not implemented all recommendations stemming from the civil rights complaint. But it has undertaken a variety of reforms designed to maintain the admissions schools’ academic standards while broadening access. And it has stopped allowing people who live outside the city of Buffalo to take the admissions test, which school officials combine with grades and good attendance to create a formula that ranks applicants for the select schools.

The result is that today 60 percent of City Honors and Olmsted seats are being earned by students from district schools, Keresztes says. Yet he agrees more work is needed to address the low numbers of certain minority groups, especially at City Honors.

***

The high ceilings and the light flowing in from interior courtyard windows give me a familiar feeling as I walk the halls of my former high school, peeking into classrooms.

Then I spot a student clad in black from head to toe, except for an opening for her eyes, and I’m reminded how much more culturally diverse Buffalo has become.

Principal William Kresse has been leading City Honors since 2005, and in between making rounds in his bright blue sneakers, he talks about recent developments and controversies. “The African-American number needs to go up.... We’ve got to take this head on,” he says.

For years, he says, he was “yelling into a big giant empty cave” when he tried to talk with district officials about structural barriers families faced. But he’s encouraged that under the leadership of Cash and Keresztes, some barriers have “been blown up.”

City Honors does strong outreach throughout the city, and Mr. Kresse plans to create a summer program with the help of a group that prepares African-American students for competitive entrance exams.

In some ways the school seems more integrated now than in my day. Class levels used to track largely along racial and economic lines, for instance, with the advanced classes being disproportionately white. But Kresse oversaw the elimination of tracking. Everyone takes International Baccalaureate or Advanced Placement courses. About half the students – regardless of their background – opt to pursue a full IB diploma.

I sit down in the “museum room” full of yearbooks and other objects of historical import to talk with 10 juniors and seniors. It’s quickly clear that they appreciate being in a school that stretches them both intellectually and socially.

“I’m exposed to the lives of other people who have nothing to do with me,” says Allen, an African-American who lives on the East Side. He’s got friends with Polish heritage and “friends who were talking about the Quran.... It’s so cool.”

Ellen, a white student, says, “I can learn about so many things that I will never learn about at home,” where “aerodynamics” is a typical topic at dinnertime.

Next to her, Daniel, from a Vietnamese family, says only a few others in his district elementary school were at the honors level, so coming here with advanced peers “gave me the optimism that I can shape my future.” He wants to be a surgeon.

Alexis, a science aficionado, feels both sides of the opportunity-gap issue. She’s black, and her dad was among the first to bus to integrated schools in Buffalo. One of her best friends is a white classmate she met at City Honors. In the African-American community, “I’ve been called Oreo ... as if striving for a good education is strictly associated with being white,” she says. But she’s also helped kids who attend less well-funded schools tap into resources she’s discovered through connections made here.

“Being surrounded by a decent amount of privileged Caucasian students, it can be rough at times,” she says, but she and the others agree the culture here fosters empathy and an ability to talk about differences.

***

As I watch children with colorfully beaded braids and heavy backpacks climb onto the buses at the end of the day at Waterfront, I’m wondering what their future holds.

I reached out to Sondae, my Waterfront friend, before my trip. We hadn’t talked in more than a decade, but we picked up as if no time had passed. She attended high school in Chicago, and now her son is doing the same. Up through eighth grade, though, she opted to put him in a private school that’s mostly white, because she didn’t see a public school offering what helped her thrive at Waterfront.

Cindy Ludwig, a white friend from Olmsted and City Honors, settled with her husband in Amherst, N.Y., a Buffalo suburb. Her kids’ schools are good but lack racial and economic diversity. “Everyone’s just like them.... Their whole experience is so homogeneous ... and it bothers me,” she says.

My children attend a nonprofit Montessori school in southern New Hampshire, so their public school experience is yet to come. They contribute to racial and international diversity – from my husband’s British upbringing and his parents’ roots in India and Mauritius. Still, I often wonder if we are doing enough to interact with people from a wider range of economic and racial backgrounds.

Without the pressure of civil rights requirements, “elementary and secondary schools are becoming more unequal,” Gary Orfield, co-director of The Civil Rights Project, told me last spring. “The problem isn’t curing itself.”

The next few years will shed more light on whether Buffalo is doing enough to spread opportunity fairly and make its top schools more racially balanced. But as I ride around town talking with Radford, I feel hopeful. He and others are keeping alive the idea that “it’s important for children to interact with each other across racial lines, across socioeconomic lines,” he says.

That’s one of the lasting legacies of Buffalo’s integration efforts: “Had we not broken through that barrier and got people to go to school together, get to know each other,” he says, “I think Buffalo in a lot of ways would be somewhere in the ’60s right now.”

This is story is part of an occasional series, Learning Together, on efforts to address segregation.

Why an Argentine leader seeks to break the pull of populism

President Macri promised to make Argentina a ‘normal’ country, far removed from the populist boom-and-bust economic cycles of the past. But populism's pull may be stronger than he bargained for.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

From Perón to Kirchner, Argentina’s been defined for decades by its leftist, populist governments – and its economic crashes. It’s a trend that President Mauricio Macri is finding is harder to break than expected. His attempts at stabilizing and normalizing the country – from negotiating an International Monetary Fund loan to stave off default, but cutting highly popular subsidies in the process – haven’t reaped the benefits he or his supporters hoped to see. And now it’s looking as if his populist predecessor has a shot at squeezing him out of office next year, likely swinging the government back to high-cost social spending. Observers say four-year presidential terms may not be enough to truly wean Argentina off of populism, but the bigger question is whether Argentines are truly interested in leaving such an ingrained political tradition behind. “The younger people grew up with the Kirchners, and many of them associate those years with good times,” says Argentine economist Matías Carugati. Compared to that, Mr. Carugati says, the idea “of making Argentina a ‘normal country’ isn’t as attractive.”

Why an Argentine leader seeks to break the pull of populism

Young Andrés Watle has only been around for about three decades – and yet that’s long enough to have known the economic ups and downs of Argentina’s legendary populist governance.

“It seems great when you’re living the good times of el populismo, with services practically given away and a feeling that we’re a wealthy country,” says Mr. Watle, a Buenos Aires travel agent.

“But inevitably comes the fall to the not-so-good times, and that feels less good, and it hurts a lot of people,” he says. “It’s a pattern we need to break.”

Breaking the pattern of the boom-and-bust economic cycles that have defined Argentina’s economy for decades was a central objective of Argentine President Mauricio Macri when he took office in 2015.

Mr. Macri’s winning campaign pledge: to make Argentina a “normal” country, permanently off the populist roller-coaster.

In Argentina, populismo is historically associated with the left: leaders who are charismatic and pledge to serve “the people” over national elites, and rely on widespread public spending and subsidies. They’ve played a key part in perpetuating a boomerang economy. A populist will typically spend widely on social programming, and when the coffers are empty and a new, typically opposition leader is elected, the nation takes on austerity measures.

Macri inherited an economy that was careening toward default. His predecessor, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, used the proceeds of the recent commodities boom to heavily subsidize gasoline and provide electricity that was practically free.

For many economists, especially free-market liberals, Macri’s task was nothing short of halting Argentina’s slide under the Kirchners to something approaching the economic collapse of Venezuela.

But three years later, Macri is finding that weaning “the people” off the milk of populism is not easy – perhaps all the more so in a country where the populist tradition extends back to the post-WWII boom years of Juan and Eva Perón.

To stave off default, Macri this year negotiated a $57 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund. But the loan came with strings attached: cuts in spending, slashed subsidies, cutbacks in the pension programs that had been expanded by Kirchner and her predecessor in office, her late husband Néstor Kirchner.

As electricity bills and gas prices have soared, and unemployment rates and small-business bankruptcies have risen, Macri’s popularity and prospects for re-election next fall have plummeted.

“This is a country that after so many years of populism has become used to the government handing out more all the time,” says Juan Luís Bour, chief economist at FIEL, the Foundation for Latin American Economic Studies, in Bueno Aires. “Argentines basically understood this system was not sustainable – which is one reason Macri won,” he says. “But to get to ‘normal’ the government has had to break some eggs, and that kind of change is going to hurt a lot of people.”

As Macri’s fortunes have crashed, prospects for the return to power of Kirchner – and for yet another swing to the populist left – have risen.

“The popular thinking out there is, ‘Macri tried to move us away from populism – and look where it got us, to even higher debt, higher and rising unemployment, and more difficult living conditions,’ ” says Matías Carugati, chief economist at Management & Fit, a Buenos Aires consulting and public opinion firm. “People tend to remember the good times of populism, but no so much the bad.”

‘We can't eliminate it in four years’

Polls show Macri retaining support of about a quarter of the electorate. They show Kirchner with similar levels of support. That leaves a huge slice of the population dissatisfied with both options – and seemingly open to some third candidate, yet to emerge.

Noting that many economists expect the government’s tough adjustment measures to begin yielding positive results next year, Mr. Carugati says an economic recovery that is perceptible to the public might not come soon enough to boost Macri’s electoral fortunes.

Global conditions haven’t helped, Carugati says. Macri banked on a recovery through opening up the country to the world – just as the global trend moved to heightened protectionism and less enthusiasm for trade accords.

Pointing to a shantytown that has sprung up within eyesight of the sleek high-rise where he works, Carugati says South American migrants – most recently from Venezuela – have streamed in, exacerbating conditions for poor Argentines.

But perhaps most important is that one presidential term may not be enough to change a national mindset, he says.

“If it’s a cultural thing that we Argentines are fond of populism, maybe the reality is that we can’t eliminate it in four years.”

Carugati says other Latin American countries, including next-door neighbors Uruguay, Chile, and Peru, have moved away from populist pasts, “so we know it’s possible.”

Yet, not all populist models in the region are alike. In Chile, for example, populism was carried out by a brutal military dictatorship. No one emulates that today, making it easier to banish the approach.

‘A populist 'habit’?

It’s not difficult to find unhappiness with Macri’s project on the streets. Alfonso Andrade, a produce vendor in the city’s San Telmo neighborhood, says electricity price hikes alone – he claims to have been hit by a rise of 4,000 percent in his bills – could do him in. “At this rate I could lose my business,” he says.

But that’s just in the center of the capital, which by most measures is far better off than the rest of the country.

“Where we are right now, this is New York, you wouldn’t know we’re in a stagnant economy,” says Martín Ortiz, referring to the upscale section of Buenos Aires where he teaches English for a living. “But come out to where I live, and it starts to be more like Detroit,” he says, referring to where he lives about 20 miles south of the capital.

Mr. Ortiz says Macri hasn’t been radical enough in forcing change in Argentina.

“He started out in the right direction,” he says. But, he’s “pulling back from what he promised in the interest of getting re-elected.”

One reason for Macri’s retreat is that in order to change the country, he has had to challenge how Argentines see themselves, some social observers say – and that has not always gone down well.

Take the example of beef. For much of the 20th century, Argentina was one of the world’s top beef exporters. But the emphasis on exports made it increasingly expensive at home.

Mr. Bour of FIEL says the Kirchners saw imposing high taxes on beef exports as a way to kill two birds with one stone – fill government coffers to help pay for subsidies, and make beef a staple of the Argentine dinner plate again. Argentina slumped from its top-tier ranking among world meat exporters to 11th or 12th place, Bour says.

Last month Macri announced Argentina’s re-entry into the US meat market during President Trump’s visit for the Group of 20 industrialized countries summit. But higher domestic prices have once again led to public grumbling.

Bour says that older Argentines are among the biggest supporters of a return to populism – in part because Kirchner made a government pension the right of everyone, whether they contributed to the system or not.

But perhaps more surprising is the strong youth support for Kirchner in the polls.

“The younger people grew up with the Kirchners, and many of them associate those years with good times,” says Carugati. Mrs. Kirchner’s time in office is also associated with an era of idealistic themes like human rights and regional solidarity.

Compared to that, the idea “of making Argentina a ‘normal country’ isn’t as attractive,” he says.

“But I’m a young person too,” says Watle, the travel agent. “I think there are a lot of others like me who believe that as difficult as it might be, we have to break the populist habit.”

How one author illustrates gratitude – on the page and in life

Jarrett Krosoczka’s recent memoir is about growing up with a parent struggling with addiction. But its messages for young people focus on resiliency and giving thanks.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

A compliment from a children’s book author gave Jarrett Krosoczka the boost he needed as a third-grader to feel confident in his drawing. On a recent Saturday, he invited that same author to talk about art and their friendship in Boston. At the end of the event, he presented Jack Gantos with a painting of Rotten Ralph, the character of Mr. Gantos’s he drew some 30 years prior. Gratitude is a common theme of Mr. Krosoczka’s – having spoken of it in TED Talks and included it in his new memoir for teens, “Hey, Kiddo,” a National Book Award finalist this year. In the book, he tells the story of how he was raised by his grandparents while his mother battled a heroin addiction. “I wouldn’t change a single thing about my childhood because it made me who I am,” he says in a phone interview. “I’m grateful for everything that’s led me up to this point.” (Jarrett Krosoczka’s story demonstrates the power of great teachers. Did a teacher have a profound influence on your life? If so, we want to hear from you. Submit your story here and it may be included in an upcoming project. Bonus: It’s a great way to practice gratitude.)

How one author illustrates gratitude – on the page and in life

Jarrett Krosoczka, unshaven and unnerved, paced the floor of his kitchen in western Massachusetts. As a children’s book author, he knew how to tell stories. But as a last-minute substitute that Friday afternoon six years ago, Mr. Krosoczka only had four hours to craft a TEDx Talk.

His wife, Gina, knew immediately what he should speak about: his upbringing as the son of a mother addicted to heroin. “Be honest and be transparent,” he recalls her saying.

Now, with his first book for young adults, an illustrated autobiography, he takes that edict to heart once more.

In “Hey, Kiddo,” Krosoczka celebrates his grandparents, who made the choice to raise him as their own son as his mother struggled with addiction. In the memoir, a National Book Award finalist, he brings to life his upbringing with a muted ink palette featuring only flashes of burnt orange – the color of one of his late grandfather’s pocket squares that now serves as a safety blanket for one of Krosoczka’s daughters.

“I wouldn’t change a single thing about my childhood because it made me who I am,” he says in a phone interview. “My mother’s [artistic] talent and incarceration made me want to do something big with my artwork.... I’m grateful for everything that’s led me up to this point.”

From writing his memoir to starting a national lunch lady appreciation day (one of his series features a crime-fighting cafeteria worker), the author regularly makes the case for gratitude: A thank-you reminds both giver and receiver of their importance and connection to others.

“A thank-you can change a life,” Krosoczka (pronounced Crow-sauce-KA) said in his second TED Talk. “It changes the life of the person who receives it, and it changes the life of the person who expresses it.”

And at a recent event at the Boston Athenaeum, he took the opportunity to show his gratitude to another writer who helped him along his way.

‘Nice cat’

In 1986, children’s book author Jack Gantos visited Krosoczka’s third grade class at Gates Lane Elementary School in Worcester, Mass.

He went room to room, assigning the first task he could think of: Draw his character Rotten Ralph. He patrolled the aisles between the desks. Krosoczka had drawn the best one. “Nice cat,” Mr. Gantos told him. Krosoczka writes about the encounter in his memoir, depicting his third-grade self as swelling with pride.

On a Saturday in November, Krosoczka invited Gantos – who won the Newbery Award for children’s literature for “Dead End in Norvelt” – to talk about art and their friendship. At the end, he presented Gantos with a painting of Rotten Ralph.

“It was kind of a thank-you from him,” Gantos says in a phone interview. “And I’m very grateful that he mentioned me. It reminds me to always say that to every kid that has any kind of talent or sometimes even a good-looking stick figure.”

Gantos’s bright red “very very nasty cat” and Krosoczka’s bright yellow Lunch Lady now stand side by side in a mural honoring Massachusetts children’s book authors at Boston’s Logan Airport.

Both Gantos and Krosoczka individually travel across the country talking to students about art and writing. These visits convinced Krosoczka that not only did he want to write his memoir, but he needed to write it.

“Every school I went to – it didn’t matter what town, what city, what state – I would talk to the teachers and they would say, ‘We have kids here who are just like you,’ ” he told the audience at the Athenaeum, one of the oldest independent libraries in the United States. “They have an incarcerated parent. They have an addicted parent. They’re being raised by an uncle, an aunt, or a grandparent. It wouldn’t matter if the school was 99 percent free and reduced lunch or it was a $30,000-a-year private school,” he says.

‘Hey, Kiddo’

Krosoczka knew “Hey, Kiddo,” his 38th book in 17 years, would be a big shift. He worried what readers and his family would think. After all, his grandparents “cursed like truckers who used to be sailors,” he says at the Boston event.

The memoir, which was a finalist for the National Book Award, is cropping up on end of the year “best of” lists. And while the top honor went to Elizabeth Acevedo for her novel “The Poet X,” Krosoczka says being a finalist – and the accompanying sticker – will help the book reach a wider audience, including kids struggling with the same issues.

At a recent reading, he noticed a very young boy in the audience. At first he wondered if the boy might be too young for the content (which is labeled 12 and up) but resisted saying anything because the boy and the adult he was with sat with such intention. While signing the boy’s book, he learned that the 8-year-old’s brother, who was 12, had recently died of an overdose.

“It’s each caretaker’s decision” what books their children read, he says. “But they should make that decision knowing that my mother started using when she was 13 years old.... Having these difficult conversations in the safe space of a book before the child has to deal with it in real life is really important.”

‘That is who I am’

On a school visit to his old elementary school in 2001, Krosoczka ran into his former lunch lady, Jeanie. That encounter sparked the idea for his crime-fighting Lunch Lady character (her catchphrase: “Justice is served”) and School Lunch Hero Day, a national day of appreciation started in 2012.

To show their gratitude to the men and women who feed them, some kids draw their lunch ladies as superheroes. One class made a hamburger of thank-you notes. Another made a thank-you pizza.

“Gratitude just permeates my work because that is who I am,” Krosoczka explains, adding, “Authors really are their works.”

Seeing an author model gratitude can be powerful for young people, especially if they lack models in their lives, says Jeffrey Froh, a Hofstra University professor who studies positive psychology.

“Gratitude strengthens your relationships – that’s the bottom line. It’s like social crazy glue,” he explains.

Countless caretakers tell Krosoczka that the Lunch Lady books made their kids want to read, he says. (He always uses the word caretakers rather than parents – a choice made with kids like him in mind.)

“Some people just get it with kids, and he’s one of them; he’s not preachy,” says Marianne Stanton, a librarian at the Melrose Public Library in Massachusetts who attended his Boston talk.

Krosoczka says he also benefited from adults who understood young people. An important moment in his book – and life – features Mark Lynch, who taught the author comics and animation as a teenager at the Worcester Art Museum. Mr. Lynch says in an interview that Krosoczka captured the truth of their relationship in the book, “even my gestures.”

Hearing from Krosoczka “is the thing that you live for as a teacher,” says Lynch, adding, “It reminds you of the awesome responsibility of teaching.”

Whatever Krosoczka writes next, Lynch says, he knows the author will make the 65-mile trek to Worcester – as Krosoczka has done once a year for the past 17 – to be a guest on Lynch’s radio show. He will, as he’s always done, go out of his way to make time for his former teacher.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Putin’s praise of a truth-telling dissident

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Vladimir Putin paid tribute on Tuesday to the late Alexander Solzhenitsyn, unveiling a statue honoring the Nobel Prize-winning author on the centennial of his birth. Solzhenitsyn, the Russian president remarked, never allowed anyone to speak “badly about his motherland.” That may have been news to those at the Moscow event. For decades, Solzhenitsyn was a fierce critic of his country. Fortunately, Solzhenitsyn’s widow, Natalia Svetlova, also spoke, reminding Russians that people today are still kept in “heavy conditions” like the fictional character in the writer’s first novel, a book about a gulag inmate. “We have to remember...,” she said, “to look around us with open eyes.” Truth-tellers with “open eyes” are as needed today in Russia as they were in the Soviet era. Solzhenitsyn’s writings helped collapse the Soviet Union from within. In contrast, Putin regards the end of the communist empire as a great “geopolitical tragedy.” The more Mr. Putin tries to honor Solzhenitsyn, even by claiming the writer disapproved of criticism of Russia, the more Russians may write and speak in ways that counter fake news.

Putin’s praise of a truth-telling dissident

An object of investigation in the West for spreading fake news, Vladimir Putin paid tribute on Tuesday to a man known for truth-telling. The Russian president praised the late Alexander Solzhenitsyn on the centennial of his birth and unveiled a statue honoring the Nobel Prize-winning author.

Mr. Putin’s highest praise – for a writer known for exposing the ideological lies of tyrants – was that Solzhenitsyn never allowed anyone to speak “badly about his motherland.”

That may have been news to those attending the event in Moscow. For decades, Solzhenitsyn was a fierce critic of his country. Fortunately, Solzhenitsyn’s widow, Natalia Svetlova, also spoke, reminding Russians that people today are still kept in “heavy conditions” like the fictional character in the writer’s first novel published in 1962. The book, “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich,” depicts the unpleasant truths of an inmate’s day in a slave labor camp, or gulag, under dictator Joseph Stalin.

“We have to remember...,” she said, “to look around us with open eyes, and to provide help to Ivan Denisovich if he needs it.”

Truth-tellers, or those with “open eyes,” are as needed today in Russia as they were in the Soviet Union of 1917 to 1991. Even a decade after his death, Solzhenitsyn still stands out as an icon of how individuals speaking the simplest truths can bring down a corrupt system.

“One word of truth outweighs the whole world,” he said, based on what he called “an unchanging Higher Power above us.” And his corollary was just as important: “Never knowingly support lies.”

More than any other Soviet dissident, Solzhenitsyn’s great writings, especially the nonfiction trilogy “The Gulag Archipelago,” helped collapse the Soviet Union from within. In contrast, Putin regards the end of the communist empire as “the greatest geopolitical tragedy” of the 20th century. The more Putin tries to honor Solzhenitsyn, even by claiming the writer disapproved of criticism of Russia, perhaps the more Russians will write and speak in ways that counter fake news.

Putin is no Stalin but his actions, such as jailing human rights activists, have turned many in the West against him. In a Pew poll of 25 countries this year, 63 percent of people had no confidence in Putin to do the right thing in global affairs.

Both Putin and Solzhenitsyn are Russian patriots. But the latter saw patriotism in a different way. “A great writer is, so to speak, a second government in his country,” he wrote. “And for that reason no regime has ever loved great writers.” In his later years, Solzhenitsyn welcomed praise from Putin. But he never relinquished his role as a truth-teller or his wish for Russians to speak the truth as well.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Mary’s Christmas message: humility empowers us

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

Today’s contributor explores timeless, healing lessons we can learn – even 2,000 years later – from one of history’s most significant women.

Mary’s Christmas message: humility empowers us

Humility has had something of a bad rap over recent decades. It has often been seen as weakness in contrast to power, vulnerability in the face of aggression, and self-effacement in place of self-promotion. But is that truly what humility is?

Perhaps an answer lies in the story celebrated this time each year, particularly the role played by a remarkable young woman. Millions of Christmas cards annually portray Mary meekly cradling the infant Jesus, whose birth was the promised arrival of a long-anticipated Messiah. But they can’t begin to depict the powerful spiritual backstory of this meek mother.

Mary’s child grew to be humanity’s greatest benefactor, pointing the way beyond the burdens of material belief by proving the true, spiritual nature of all, as God’s children. Yet did the babe’s birth itself coincide with a glimpse of this divine idea?

Yes, according to another woman named Mary – Mary Baker Eddy. Pointing to “the glorious perception that God is the only author of man,” the discoverer of Christian Science wrote in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “The Virgin-mother conceived this idea of God, and gave to her ideal the name of Jesus – that is, Joshua, or Saviour” (p. 29).

This unconventional conception, then, did not take place in a vacuum. It was the outcome of a clear spiritual awareness. Science and Health explains, “The Holy Ghost, or divine Spirit, overshadowed the pure sense of the Virgin-mother with the full recognition that being is Spirit. The Christ dwelt forever an idea in the bosom of God, the divine Principle of the man Jesus, and woman perceived this spiritual idea, though at first faintly developed” (p. 29).

What’s striking about these insights is how they indicate the Virgin-mother wasn’t just a passive recipient of a “miracle” child. Through exercising pure (spiritual) sense, she perceived the spiritual idea whose full development would emerge in her hallowed son. And she was humble enough to receive a revelation from God, the divine Mind.

As described in the Bible, when she got the extraordinary message from God that she was to bear the child who would be the promised Messiah, Mary responded, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word” (Luke 1:38).

You could say this illustrates how meekness can be the gateway to finding out just how special each individual is as a child of God. The nature of Mary’s entry into motherhood was a one-time historical occurrence. But the way it occurred indicates a capacity we all have to open our hearts to God’s guidance revealing the distinct way we are each called to love Him and serve our fellow men and women.

So while humility is commonly defined as a modest view of one’s importance, in spiritual terms it is almost the opposite. It includes mentally bowing to the spiritual fact that we’re each vital to God’s complete expression of Himself. Without any one of us, His glorious expression would be incomplete.

The words and healing works of the child born to Mary show us our profound worth as God’s unique expressions. When urging the value of being meek to those who heard his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus said that by doing so they’d inherit the earth. Eugene Peterson’s “The Message” Bible translation paraphrases that as finding ourselves “proud owners of everything that can’t be bought” (Matthew 5:5).

In this way, humility is spiritual power. It can free us from sickness and self-destructive behavior. It can disentangle us from a sense of vulnerability to others’ attitudes and actions. And it can replace both self-effacement and self-promotion with unselfed love for all, including ourselves.

We can, of course, prayerfully reach for this meek and mighty understanding during the holidays. But doing this can make us happier and more loving at any time of the year and open our hearts to needed healing for ourselves and others. As 20th-century women’s rights campaigner Helen Steiner Rice said: “Peace on earth will come to stay, / When we live Christmas every day” (Daniel A. Armah, “Lessons of Christmas,” p. 178).

So let’s live Christmas throughout 2019 by following in the healing footsteps of Christ Jesus and by echoing the example of that bold young Mary who illustrated the power of humility available to us all.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Dec. 19, 2016, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

The whole world at her feet

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we have one of the best stories you’ve probably never heard of this year. It’s from Armenia, and it looks at a revolution fueled by Twitter, civil disobedience, and a lot of hugs for police officers. Armenians are getting a taste of truly free and fair elections for the first time.