- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Controversial. Chaotic. But not a do-nothing Congress.

- Are Greek and EU officials illegally deporting migrants to Turkey?

- For Mideast Christians, US refugee policy puts a damper on Christmas

- Want to get rid of classroom bullies? Just add babies.

- Chasing darkness: One reporter’s journey into the night

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The islands that could save a lake

A week of political fireworks in the US (we’re watching the government-shutdown saga) also featured the flares of some coldly ambitious tech.

Humanity might have seen the world’s first five-rocket-launch day – missions both national and private – had a bunch of them not fizzled. There was a fresh run by Uber at autonomous cars, and the temporary shutdown of London’s Gatwick Airport by drones of unknown origin.

Hands-on human innovation today extends even to the natural-sounding realm of islands. Most recently in the news because of the existential threat posed to them by rising seas, they’ve also popped up – in artificial form – as territorial markers (think China’s outposts in the South China Sea).

But it’s not all competitive human calculus.

In the Netherlands, a handful of built islets have emerged in a massive freshwater lake, part of a very Dutch effort that’s now paying environmental dividends according to a report from Agence France-Presse.

Construction involved silt, not just sand, and in only 2-1/2 years the islets have provided a foothold for nearly 130 plant types, their seeds borne in by the wind. Tens of thousands of swallows have also arrived. Most important, an “explosion” of life-sustaining plankton is reviving the once-dead lake.

Says one ranger of the high-tech rewilding effort, “We had to intervene.”

Now to our five stories for today, including a look at the deployment of babies against bullies, and, as we enter the Northern Hemisphere’s longest night, a science writer’s celebration of cosmic darkness.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Controversial. Chaotic. But not a do-nothing Congress.

You might have expected a one-party-controlled Congress to have accomplished a lot. But what this one got done – including some bipartisan work – came despite deep political disruption.

To say the 115th Congress has had a bumpy road may be an understatement, given the Trump administration’s roiling of Washington seas and a still-unfinished budget drama. But it has been one of those historically rare periods in which one party controls both the White House and both chambers of Congress. And Congress has notched some achievements that Republican leaders tout: a major tax cut, disarming the individual mandate in Obamacare, and not least, Senate confirmation of two Supreme Court justices and a record 30 appellate judges. The term included bipartisan moves too, from the most significant criminal-justice reform in years to a farm bill and #MeToo sexual harassment legislation applying to Congress itself. “There wasn’t a lot of legislation, but it was big and it was significant, and like many Congresses, it was all crowded toward the end,” says former Senate historian Don Ritchie. New to Congress was a tweeting, “outsider” president who puts a premium on disruption, and who is inexperienced with governing. His base loves it, but it means consternation on the Hill. “Everybody,” says Ritchie, “would like a return to greater stability. Greater predictability.”

Controversial. Chaotic. But not a do-nothing Congress.

The 115th Congress is going out with a bang – but not the celebratory kind.

Instead it is a deafening noise of shutdown drama and alarm bells over national security that is drowning out the accomplishments of the last two years. Republican Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell describes this Congress as the most successful – from a “right-of-center” perspective – in decades.

The Kentuckian readily itemizes GOP wins: a tax cut for corporations and individuals, regulatory rollbacks, and a record number of judicial appointments, including two Supreme Court justices.

As sometimes happens in a lame-duck session when a deadline looms, a flurry of bipartisan legislation also passed, from the most significant criminal-justice reform in years to a farm bill and #MeToo sexual harassment legislation applying to Congress itself.

“There wasn’t a lot of legislation, but it was big and it was significant, and like many Congresses, it was all crowded toward the end,” says former Senate historian Don Ritchie.

But that's hard to notice when politics is roiled like an angry ocean, amid the unconventional presidency of Donald Trump.

Conservative talk-show hosts and right-wing House Republicans mutinied over a short-term budget deal worked out by the leaders of both parties. The deal would have avoided a partial government shutdown over the holidays by extending current government funding through Feb. 8.

But the extension had no new money for a border wall, arguably President Trump’s top campaign promise, and so the right-wing rebelled – as did the president – causing senators who had already left town for such far-flung states as Hawaii to return quickly to Washington.

On top of that came the unexpected announcement by Trump that he is pulling US troops out of Syria because he says the war against the terrorist group ISIS has been won. That prompted the resignation Thursday of Defense Secretary James Mattis, who openly cited his disagreements with the commander-in-chief. Republicans, Democrats, and America’s allies sounded klaxon alarms at this sudden turn of events. Even the taciturn Mr. McConnell said he was “particularly distressed” by the resignation.

In November, voters repudiated unified Republican control in Washington, handing the House to Democrats. It marked the end of one of those rare opportunities that a party has when it controls both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue.

“The thing that I am struck by is how short-lived unified party control has been” in America’s history, says Sarah Binder, a congressional expert at the Brookings Institution think tank in Washington.

Democratic Presidents Obama and Clinton enjoyed it in their first two years, before voters changed their minds. Republican President George W. Bush had it in the middle of his eight-year presidency. One could argue an “almost” case for President Reagan, whose 1980 election brought the first GOP-controlled chamber – the Senate – since 1953. While he faced a Democratic House, he found support among conservative “boll weevil” Democrats.

But divided control is more the norm, with Americans rejecting “overreach” by one party in power, or the public simply shifting directions or wanting change.

Historian Ritchie grants McConnell his definition of success in this Congress, but points out that Reagan’s first two years were “surprisingly productive,” including a major tax cut. What probably puts this Congress over the top in terms of a conservative agenda are the record numbers of court appointees, says the historian.

While the public focuses on the Supreme Court, and the confirmation battle over Brett Kavanaugh certainly had its undivided attention, the high court decides only 100 cases a year, points out Prof. Carl Tobias, at the University of Richmond School of Law in Virginia. The Trump administration has focused like a laser on the federal appellate courts, which decide nearly all of the cases in their regions, he says. The Senate has confirmed a record 30 such judges, and in the next Congress, Americans can expect “at least as conservative, if not more conservative” judges because Republicans will control more seats.

One distinction of this Congress has been the further erosion of Senate rules and the heavy reliance on rarely used procedures that put the minority party at a severe disadvantage. Indeed, it was through these changes that Senate Republicans were able to cope with their very slim majority to score their marquee achievements: judges, the tax bill, the negating of the individual health insurance mandate (though not Obamacare itself), and regulatory rollbacks.

On Friday, the president demanded that Republicans also fell another Senate rule, the legislative filibuster. That requires that essentially all legislation meet a 60-vote threshold in order to pass. Doing away with it would allow the president to get his $5.7 billion for a wall, passed Thursday night by a majority in the GOP-controlled House. But McConnell and many Republican senators are adamant about keeping it out of concern that they will get steamrolled when their time in the minority comes.

Bipartisanship surged toward the end of this Congress, particularly with the passage in both chambers of the “First Step Act,” which aims to reduce recidivism in the federal prison system and lower the number of prisoners by changing sentencing laws. Lawmakers in both parties had been working on this for years, and it was greatly helped by a big push from the president’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner.

“We shouldn’t forget that even with the discord, bipartisan bills got through,” says John Fortier of the Bipartisan Policy Center, which puts out a quarterly “Healthy Congress Index.” He names opioid legislation and funding for child healthcare as examples.

On the other hand, Democrats were angry that the president, who signed a bipartisan farm bill this week, plans to revive a work requirement for food stamps by using the regulatory powers of the executive branch. It was only by dropping a work-for-assistance provision that the two parties were able to agree on the bill in the first place.

The partisanship, internal GOP division, and presidential unpredictability that so characterized this Congress limited its potential, observers say, pointing to missed opportunities.

Republicans could not coalesce around a “repeal and replace” of the Affordable Care Act – nor could the parties come together to fix its flaws. On the wall, the president had an opportunity to back a bipartisan bill that provided $25 billion for border security, including a wall, as well as a fix for young immigrant “Dreamers” – but decided to side with immigration hardliners in the Senate and his administration instead. In the end the bipartisan bill had the most votes; the president’s bill, the fewest. After the Parkland shootings, he seemed willing to buck the National Rifle Association on background checks, then changed his mind.

New to Congress was a tweeting, “outsider” president who puts a premium on disruption and who is inexperienced with governing. His base loves it, but it has caused deep consternation on the Hill.

When a Trump about-face shifted the budget talk from “deal” to “no deal” late this week, Sen. Ron Johnson (R) of Wisconsin offered, wryly: “Who knows, this could all change in 30 minutes.”

“I don’t think this is a Congress that any of its members would really want to live through again,” says Ritchie. “It wasn’t the happiest of times for either party. A lot of it had to do with an unpredictable president that caused a lot of tension. Everybody would like a return to greater stability. Greater predictability.”

Special Report

Are Greek and EU officials illegally deporting migrants to Turkey?

While reporting in Greece on another story, Monitor correspondent Dominique Soguel heard tales of migrants being beaten and illegally expelled from the EU by border officials. So she investigated.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By Dominique Soguel Correspondent

Under international law, refugees cannot be returned to a country where their life or freedom is at risk; once they have crossed a border, they must be allowed to apply for asylum if that is what they are seeking. But in Greece, it seems that legal standard is not being met. In multiple incidents reported by human rights groups and supported by a separate investigation by The Christian Science Monitor, migrants say they have been beaten and forcibly “pushed back” across the Evros River, which runs along the Greek-Turkish border. And they say that the perpetrators of the pushbacks have been Greek police officers and members of Frontex, the EU’s border agency. Police and Frontex officials deny involvement. But the violence against the migrants is well documented, and access to the border – a military zone – is highly restricted on the Greek side. “There is a significant body of evidence,” says Eleni Takou, deputy director of HumanRights360, one of the groups documenting the incidents. “Thirty-nine testimonies from us, 24 from Human Rights Watch.… It is becoming obvious that there are several groups in the region who do this.”

Are Greek and EU officials illegally deporting migrants to Turkey?

Fadi Jassem is a skinny Syrian man with sorrow etched on his face. He is one of more than a hundred refugee squatters living in a forsaken building in central Athens. The only document he holds is a Syrian identity card, chipped on the top corner. He blames Greek border police and Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, for his plight.

That’s because Mr. Jassem used to be living a relatively happy life in Germany as a recognized refugee with a three-year residency permit. But then he heard his little brother had gone missing hours after crossing from Turkey to Greece with the help of smugglers. The 11-year-old boy had just been ferried across the choppy waters of the Evros River in the middle of winter when he disappeared. “He got lost in the border area, so I went to search for him there,” Jassem told The Christian Science Monitor in October.

That's when it all went wrong for Jassem. “Greek police grabbed me and handed me over to Frontex. They destroyed all my documents. They put eight of us on a boat and pushed us back to Turkey.”

He assumes that the officials responsible were Frontex because they were masked and spoke German rather than Greek. The police officers, he says, beat and insulted him. It took Jassem many months and several attempts to manage to cross back into Greece from Turkey. Now he hopes that Germany will take him back.

Jassem became the victim of forced pushbacks, an illegal tactic of forcibly removing migrants from European soil, usually soon after they’ve crossed over the European Union’s external borders. The phenomenon is difficult to measure, in large part because of the outright denial by authorities that it is taking place. But evidence of its recurrence is growing, and human rights groups are sounding the alarm, concerned by the frequency and patterns of abuse relayed by migrants trying to reach Europe.

Illegal deportations?

Forced pushbacks are in violation of international law. A key principle of the 1951 Refugee Convention in Geneva, which has been signed by 148 states including Greece, is non-refoulement. The charter prohibits refugees being returned to a country where their life or freedom is at risk. Borders may be crossed irregularly and without documents when the intent is to request asylum; people fleeing war rarely have their documents in order, if at all.

The practice, according to humanitarian workers and human rights researchers with long track records in the Evros region, has long been a problem along the Turkey-Greek border. But the growing frequency of these incidents and the range of actors apparently involved has triggered alarm and a new push for accountability.

Human Rights Watch documented 24 incidents of pushbacks across the Evros River from Greece to Turkey this year. That tally is the outcome of interviews conducted with migrants on both sides of the border this year. Researcher Todor Gardos says they took a conservative approach to the figures. Even if an individual described being pushed back seven times, along with more than 100 other people, this was logged as one experience.

“If you turn up at a border police station in Greece now, it is a matter of lottery whether you get into the asylum or registration process, or whether you get pushed back,” says Mr. Gardos.

Several migrant men claimed Greek police and army officers brutally beat them with batons during the pushback. They expose their backs in a video, recirculated by HRW, as proof of their bruising. Greek social and legal service providers are also collecting evidence in the hope of triggering a change of attitudes from government officials and paving the way for accountability.

The Greek Council for Refugees, HumanRights360, and ARSIS (the Association for the Social Support of Youth) published 39 testimonies of people who attempted to enter Greece from the Evros border with Turkey but were forcibly pushed back. The Monitor has also spoken to refugees and smugglers in Turkey and Greece who tell similar stories. Details – like the destruction of personal documents and phones – repeat themselves.

The number of refugees and migrants arriving in Greece has dramatically dropped since 2015, when the EU and Turkey signed an agreement to send back to Turkey migrants who do not apply for asylum or whose claim was rejected. More migrants reach Greece from Turkey via the Aegean Sea compared to the land borders, although on average these witnessed more than 1,600 arrivals per month in 2018.

Migrant crossings and forced returns typically take place at night by most accounts, although police officials deny they are happening. A Syrian woman told the Monitor her children were stripped of their coats and shoes before being shuttled across the river to Turkey by masked men in the middle of the night.

“People pass the river and wait for the night to get into the mainland undetected,” says Eleni Takou, deputy director of HumanRights360. “If they are detected, Greek forces, military or police, take them to a detention place, which is not always a designated detention place; it could be a warehouse. Then there are people who take them back. They have a full face mask. Even if faces are visible, there is no insignia to identify them.”

Three residents of the riverside farming villages near Orestiada say that pushbacks are routine. They see them because their land flanks the military zone. The trio gave their accounts on condition of anonymity, as most residents have relatives serving in the Greek military and police.

One young farmer pointed out a river intersection where he said police carry out regular patrols and pushbacks. He says he has witnessed Greek police officers intercept migrants on arrival and load them into blue buses (typically used for arrests).

“These buses then drive into the fields, towards another point in the river,” he says. “There is no other reason to take them there. There is only the river, and they have the police boat with them. Why else would they take them there if not for pushbacks?”

A dangerous crossing

A senior Greek police officer rejected the notion that voluntary or involuntary returns were taking place at the river. He said asylum seekers are treated in line with international obligations, while those who do not seek international protection may be detained and then formally deported.

“The Greek police is in charge of protecting the borders and managing the migration flows,” said Paschalis Syritoudis, police director of Orestiada. “It is all inflow. There is no outflow.” Since the launch of Greece’s Operation Shield in 2012, he notes, 500 smugglers have been arrested and tried, more than 500 river boats confiscated.

Crossing the river by boat typically takes only five to 10 minutes, but bad weather can drag out the process and even turn the journey fatal. There have also been killings associated with the crossing. Three migrant women were found dead with their throats cut near the Evros River, also known as Maritsa.

“Both length and depth of the river vary a lot, especially in winter,” pointed out another officer in an informal conversation with the Monitor during an official visit to the giant wired wall reinforcing the land border. “During the summertime there are a few points that are so low you can just walk across. The vast majority cross the river at night, so the police have thermal cameras. That way they can see everything.”

He says Frontex officers and police conduct the patrols, although the army is also present. The nationalities change and rotations typically last three months. The Germans, however, appear to have a consistent presence, based on the accounts of local police, residents, and migrants.

Three migrants who described pushback experiences to the Monitor said “German commandos” ferried people back across the river to Turkey. Some, like Jassem, felt confident identifying the language; others were less certain. Testimonies in the HumanRights360 report include mention of German and other languages.

“There is a significant body of evidence,” says Ms. Takou, who believes Frontex, in addition to the Greek police and army, may have a role in systematic pushbacks. “Thirty-nine testimonies from us, 24 from Human Rights Watch.… It is becoming obvious that there are several groups in the region who do this.”

Is Frontex involved?

The involvement of Frontex, an EU-level organization, in the pushbacks would take the seriousness of the phenomenon up a level. Evidence of their participation in pushbacks is much thinner, though the behavior of which they are being accused is of far greater concern to those affected. “The biggest fear here is [of] Frontex,” says an aid worker who has access to detention and identification centers in the area. “They are the ones famous for beating and thefts.”

Smugglers and migrants allege that Frontex is involved in the pushback operations due to the differences in the uniforms worn and languages spoken by the masked officials from other Greek officers in what is officially a Greek military area. Legal and social service providers assisting asylum seekers in the border towns near Orestiada have come to similar conclusions. Movements in the region are closely monitored. The smaller dirt tracks that shadow the river as well as its banks are considered off-limits, complicating the efforts of local journalists and activists who have sought to document this issue and build up evidence. The same rules apply to foreign journalists.

In October, a Frontex spokesperson noted the agency’s officers were not directly involved in border patrols. “Our role is to provide additional technical assistance to those countries of the European Union that face increased migratory pressure,” said Izabella Cooper, who put the number of Frontex officers deployed in the Evros region at roughly 30. Officers who witness a code of conduct violation must file a report to headquarters in Warsaw.

Recontacted in December, Ms. Cooper said Frontex officers wore their country uniforms as well as an obvious blue armband as an identifier. “No officers deployed in Frontex’s operations have directly witnessed any of the alleged pushbacks, and no complaints have been made against any Frontex-deployed officers,” she said. “Despite the fact that the agency was not in any way involved, Frontex takes such information extremely seriously.”

Only one Frontex officer has flagged an “alleged pushback,” she said.

Christiana Kavvadia, a lawyer with the Greek Council for Refugees, wants responsible parties brought to trial. The key is ensuring that migrants who testify are adequately protected. “Everybody tells the same story on how it takes place,” she says in a late night interview in Alexandroupolis.

“They don’t distinguish between men, women, families, pregnant women,” she adds. “The problem is getting proof because they destroy phones and documents.”

For Mideast Christians, US refugee policy puts a damper on Christmas

For Christians in the Arab world, as for many others, the vision of life in America has long been a beacon of hope. But US refugee policy has left families in transit to the US torn in two – half in, half out.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

President Trump’s imposition of tighter border controls, which require enhanced vetting and security checks for refugees from the Middle East, has disproportionally impacted Christian refugees from Iraq, Syria, and Iran. The US intake of Christian refugees from across the region was down 99 percent from 2017 to 2018, according to State Department statistics analyzed by World Relief, a Christian organization that advocates for refugees. Laith Yakona is one of thousands whose arrival on American soil has been put on hold indefinitely. As Iraqi Christians who had worked alongside the US military, his family was prioritized for resettlement. But three years after his parents left for the US to join their eldest sister and her husband, Mr. Yakona and his younger sister are still in Jordan, caught in mid-migration by the new restrictions. It’s especially hard at Christmas. “As soon as my parents left for America, our lives here have been on hold,” Yakona says. “Our family is torn in two…. As Christians, we are bearing the brunt of the wars, sectarian violence, kidnapping, and terrorism in the region. Now we are bearing the brunt of this US policy.”

For Mideast Christians, US refugee policy puts a damper on Christmas

Laith Yakona wants only one thing for Christmas, the same thing he has prayed for the last four Christmases: to spend the holidays with his family.

War, bombings, kidnappings, death threats, and death squads failed to break up the Yakona family in their hometown of Baghdad before leaving for Jordan. Yet after a decade of their navigating the increasingly polarized war-torn Iraq and then a life in exile, one event has split the family in two: a new life in America.

“As soon as my parents left for America, our lives here have been on hold,” Mr. Yakona says from the sparse rented apartment he shares with his sister in Amman, a Christmas tree propped in the corner behind the television. “Our family is torn in two, and we have been given no reason why.”

Yakona is one of thousands of Christian refugees from the Middle East whose arrival on American soil has been put on hold indefinitely amid the Trump administration’s slowdown and downsizing of the US refugee program.

Many refugees have relatives who reached the United States shortly before that overhaul, leaving hundreds of families divided and thousands abandoned in host countries like Jordan and Lebanon. This Christmas, persecuted Christians from the Middle East have been left on the outside looking in.

Although the US has never specified quotas based on religion, persecuted religious minorities have long made up a large portion of the 70,000 or so refugees per year the US has taken in on average ever since the refugee program was introduced by Congress in 1980.

Yet with the policy to tighten the borders, the US intake of refugees has dropped dramatically. In fiscal year 2017, the US government accepted a quota of 110,000 refugees. Under President Trump, the ceiling was lowered to 45,000 for fiscal year 2018. But according to the State Department, the US only took in half that number, 22,500, in 2018.

According to the UN refugee agency UNHCR, the US has shifted its refugee intake mainly to Africa, taking fewer refugees from the Middle East, who now require enhanced vetting and security checks. This new policy has disproportionally impacted Christian refugees from Iraq, Syria, and Iran.

The US intake of Christian refugees from across the Middle East was down 99 percent from 2017 to 2018, and for Iraqi Christians, down 98 percent, according to State Department statistics analyzed by World Relief, a Christian organization that advocates opening US borders to refugees.

“American churches, primarily evangelical churches, may not realize that there is a dramatic slowdown in refugee resettlement, and they definitely don’t realize that persecuted Christians have been so dramatically shut out,” says Mathew Soerens, US director of church mobilization at World Relief.

Tale of separation

Yet the tightening of borders to refugees has not only hurt those fleeing persecution and war who wish to travel to the US; it has stopped those already approved by the US government from completing their journey.

As they were targeted in Iraq both for being Christians and for having worked alongside the US military, Yakona’s family was prioritized for resettlement; in 2008 Yakona’s eldest sister immigrated to the US with her husband, a translator for US forces, after he received death threats.

Yakona and his father stayed in Baghdad until ISIS’s advance drove them to finally leave for Jordan and apply for refugee status in 2014, and they were approved for resettlement to the US. Yakona’s parents traveled to the US to rejoin their eldest daughter in Michigan in December 2015.

Yakona and his younger sister were to follow within months, but their trip was delayed by bureaucracy and then thrown up in the air by the Trump administration’s executive order temporarily halting the refugee program and banning Iraqi nationals in January 2017.

Since then, the two siblings have passed all the required additional security clearances and are informed their papers are in order. Their father, who has been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, calls each day to hear if there has been “good news.” Each time the reply is the same: Not yet.

“As Christians, we are bearing the brunt of the wars, sectarian violence, kidnapping, and terrorism in the region. Now we are bearing the brunt of this US policy,” Yakona says.

Dozens of stories like Yakona’s can be found among a 300-strong Iraqi Chaldean congregation at a church in central Amman, at one of several services for the community held each week in the capital.

At the door, an usher passes out pamphlets advertising a food drop and a “Santa gift drop” the following Sunday – few here can afford toys for their children – but prayer-goers have no interest in gifts.

“We want people to pray that we reach America,” Saad Manuail says to a white-robed priest.

No answers for the families

Mr. Manuail and his sisters Zena and Reem fled to Jordan with their parents and two younger sisters in 2009 after their father was kidnapped for 20 days and armed gunmen ordered that “all Christians leave” the Baghdad neighborhood or risk being killed.

Their father, Muhaned, was granted refugee status on American soil while visiting as a tourist in 2013, and their mother and two younger sisters soon followed.

Saad, Zena, and Reem had to stay behind in Amman and were accepted for resettlement in 2015, passing security checks, interviews with US Citizenship and Immigration Services staff, medical checkups, and a cultural immersion course.

On Dec. 4, 2016, the three were told to ready their bags as they would travel “any day now” to rejoin their family, but the January 2017 executive order by Trump put everything on hold. They have been waiting for their travel date for more than two years.

“What has happened in the past is that refugees sent to the US are told ‘You made it through the process, you can get on the plane now and don’t worry, your siblings are in the same process right behind you,’ ” says Mr. Soerens of World Relief.

“Now almost no one is coming, and there are no answers for the families that have now been separated.”

According to IRAP, a US organization that provides legal assistance and advocacy for vulnerable refugees wishing to enter the US, a duplicated vetting process introduced by the Trump administration requiring multiple security organizations to carry out similar background checks for each refugee has created a backlog, adding years to what was once a two-year resettlement process.

IRAP has filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration over the slowdown, which staff call a “de-facto way of preventing approved refugees from traveling to and entering the US.”

“Everyone is waiting. There is a huge stall in the pipeline and no one truly knows where things stand in the process,” says Trinh Tran, senior attorney at IRAP’s office in Amman. “We tell our clients to think of the more long term, closer to five years and perhaps as many as seven.”

For those waiting in host communities, conditions are tough. In Jordan and Lebanon, where most Iraqi Christian refugees have fled, it is illegal for Iraqis to work. Most have spent their life savings in Amman and now try to get by on church donations.

Money from mother in America

Meanwhile, the bulk of aid provided by international organizations is earmarked for Syrians, and even that has dried up.

Last week Yakona was informed by the UN that their monthly cash assistance, 125 Jordanian dinars that they relied on to help pay rent and utilities, was ending. Yakona and his sister are now reliant on the money their 62-year-old mother sends back from working in a hotel in Michigan.

“We are paying two rents on one salary, when I should be in the US supporting my parents,” Yakona says. “There is pressure from all sides and no relief.”

There are few alternatives. According to the UNHCR, while the US intake of refugees residing in Jordan dropped from 23,000 in 2016 to 3,300 this year, only Britain and Canada have been able to add to their quota – 1,000 each.

If refugees accepted by the US wish to withdraw their application and apply for another country, they must start at the very beginning of the process with the UNHCR at the back of the line, adding several years to their wait.

Munir, who fled to Jordan when ISIS took over his hometown of Mosul in 2015, took a different tack. He petitioned the Australian government for resettlement rather than go through the lengthy process to the US.

“I want to start a new life. I don’t want to spend years stranded waiting for the US like my friends and other Christians here,” says Munir.

Yakona will spend this holiday remembering pre-war Christmas feasts of dolma, meat- and rice-stuffed grape leaves and zucchini, while the Manuail family recall midnight mass and receiving friends and relatives who would come and go to give their season’s greetings until early Christmas morning.

“The house would be filled with laughter. You could feel the love and the energy,” said Zena Manuail. “Now everyone is separated by borders and oceans. For us, the Christmas we know is dead.”

Difference-maker

Want to get rid of classroom bullies? Just add babies.

How best to teach empathy? It’s a question with which educators have wrestled. This piece looks at a novel way of helping young students appreciate attributes such as vulnerability and strength.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Social and emotional learning has been gaining ground around the world since the late 1980s, when problems of bullying and teen suicide became more prominent and forced schools to take on a role involving more than traditional academics. One solution is Roots of Empathy, a learning program about empathy that was started in Toronto by social entrepreneur Mary Gordon in 1996; it has since spread around the globe. In a typical Roots of Empathy class, which lasts a year, a baby and parent visit students nine times, and an instructor for the program visits 27 times. By watching the infant’s development over time, children learn to empathize with his or her vulnerability and recognize their own. The goal is to make children and classrooms kinder and gentler, and ultimately society more civil – an especially important aim at a time when divisions between “us” and “them” seem to be hardening. “It looks a bit silly, it looks insignificant, it looks frivolous, it looks cute,” Ms. Gordon says. “There’s no question it’s definitely cute. But it’s absolutely profound, because the children come to understand themselves and, I hope, love themselves.”

Want to get rid of classroom bullies? Just add babies.

Baby Max, who is just 5 months old, is perched awkwardly on his belly. He is trying to prop himself up as he gazes at the group of first- and second-graders in a Toronto classroom. But the lesson is not for him today; it’s for the youngsters gazing intently back at him.

He starts to cry. “How is he feeling right now?” instructor Kathy Kathy, who accompanies Max to this classroom at Market Lane Public School, gently asks the children. “Is he sad?” They nod. “Why do you think he’s sad right now?”

“He wants to go home,” says one girl.

“Because he’s stuck on his belly,” another classmate answers.

The discussion turns to the subject of frustration. “Put your hand up if you sometimes feel frustrated,” Ms. Kathy says, and hands shoot up in acknowledgment.

This is a typical exchange in a Roots of Empathy class, started in Toronto by social entrepreneur Mary Gordon in 1996 and that has since spread around the globe. In each session, taught from kindergarten through middle school, a baby plays the role of “teacher,” showing children firsthand about triumph, failure, persistence, and character.

By watching the infant’s development over the course of a year, children learn to empathize with his or her vulnerability and recognize their own. The goal is to make children and classrooms kinder and gentler, and ultimately society more civil – an especially important aim at a time when divisions between “us” and “them” seem to be hardening.

“Kathy going into the school with a baby – it looks a bit silly, it looks insignificant, it looks frivolous, it looks cute,” Ms. Gordon says. “There’s no question it’s definitely cute. But it’s absolutely profound, because the children come to understand themselves and, I hope, love themselves.”

And she zeros in on why empathy is so crucial: Its absence “is the common thread in aggression, bullying, and violence. It’s lacking completely,” she says.

Cyberbullying and disconnect

Social and emotional learning has been gaining ground around the world since the late 1980s, when problems of bullying and teen suicide became more prominent and forced schools to take on a role involving more than traditional academics. That work has gotten renewed attention as technology has ushered in new forms of bullying and heightened a sense of disconnect from communities.

In Denmark, for example, some schools have mandatory classes in empathy. And in Kentucky, the city of Louisville launched a multimillion-dollar project called the Compassionate Schools Project.

Here in Canada, Roots of Empathy is now in classrooms across all the provinces. In a typical year, a baby and parent visit children nine times, and an instructor for the program visits 27 times.

Today the theme is “crying,” which is appropriate because Max has been fussier than normal. He just learned how to roll onto his belly and wants to practice it constantly, but he gets stuck – even in the middle of the night. He hasn’t gotten enough sleep lately, his mother explains.

As they observe his crying and think of ways to console him, Kathy explains the lessons gleaned for these mostly 6-year-old students: “They start to feel this power to do something to make someone else feel better. When someone is crying at this age, normally they’ll say, ‘Oh, you’re a crybaby.’ Now they want to say, ‘What can I do to help you feel better?’ ”

The lesson applies to middle-schoolers, too, says Market Lane junior high teacher Tom Veenstra. Although Roots of Empathy is not a magic wand for cyberbullying, it gives children tools to reflect. “When there’s a video being passed around and it comes to you, you have the choice: Am I going to keep passing it around or am I not? Am I going to ... do something to try to support the person?” he says.

“I think that the message that we really hammer home, again and again and again, is that every baby has their own unique set of characteristics and temperaments. And it’s not right or wrong; it’s who they are,” he says.

Roots of Empathy has reached nearly 1 million students, the program estimates, from the United States to Switzerland to New Zealand. In 2002 Gordon was named Canada’s first Ashoka fellow, part of a network of social entrepreneurs seeking solutions to the globe’s persistent problems. This year she received Canada’s Governor General’s Innovation Award.

Programs that try to cultivate empathy or mindfulness are not always embraced by schools or parents. Some see them as interfering with traditional academics. But teacher Marisa Diaz, whose class is working with Max this year, says she believes the time is an investment in the rest of the curriculum. “When the emotional intelligence increases, the relationships become more productive or positive. And then it translates into the work,” she says.

Studies back up the importance of social and emotional learning on academics. For example, one 2015 study published in the American Journal of Public Health, which followed kindergartners for almost two decades, concluded that those with greater social-emotional skills were more likely to experience “future wellness” in schools and jobs.

Less fighting

Roots of Empathy has been evaluated independently around the world. One Canadian study published in 2011 showed it could reduce fighting in school-age children by about 50 percent.

That’s what inspired the program in the first place. Gordon, who in 1981 started Canada’s first school-based Parenting and Family Literacy Centres, was making a home visit to a teenage mother who hadn’t shown up for one of their sessions. The young woman opened her door, a baby girl in her arms and a toddler hanging on to her leg. Gordon recalls that the mother had a gash above her eye, where her husband had beaten her – again.

“It was sort of a blinding moment,” Gordon says. “In the car on the way home – I had about a 35-minute ride home – I made up Roots of Empathy. It wasn’t out of love. It was out of sheer rage.”

In creating the program, Gordon could draw on her psychology degree, courses that she took in social work, and the four years she worked as a kindergarten teacher. She also notes that her experience growing up in a big family in Newfoundland, with parents who gave of themselves – whether that was spending time with a neighbor over a cup of tea or donating used clothes – taught her and her siblings about the power to make a difference. Three of the five siblings (including Gordon) have been awarded the Order of Canada.

Gordon says she always knew she wanted to work with children. Her nickname in the family growing up was Little Mother Mary. “I had two little brothers, and it was my joy to play with them and take care of them,” she says.

Roots of Empathy has been around for more than two decades, but when the BBC did a short segment on the organization early this year, the video went viral. Gordon attributes that to the “crisis of connection” that so many societies around the world face. “We need empathy. Look at the world. We need empathetic leaders,” she says.

But at this moment in the Toronto classroom, her gaze is focused much closer, on Max, who is audibly fussy. “How does it make you feel when you hear that sound?” Kathy asks the children, her voice soothing. She suggests that a song might make him feel better, so they sing him “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.”

“I’m tired,” says one boy. “I think Max is tired, too,” Kathy replies.

She asks the children if they have any questions before he goes. One child asks how many teeth he has.

“He doesn’t have any teeth yet, but I think he’s going to get one soon,” his mother answers. The key word in this exchange is “yet.” It teaches children that everyone is on his or her own timetable. They might not know how to read yet, but they will learn.

“We’re all a work in progress,” Gordon says. “What Kathy is really helping them to develop is the language for their feelings,” she says. “It does change children. It sensitizes everybody, and the ecology of the classroom becomes kinder.”

• For more, visit rootsofempathy.org.

Other groups providing activities to children

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects below are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

• Niños de Guatemala gives an education to underprivileged children as well as their families and communities. Take action: Lead an arts or sports workshop for the youths.

• Avanse aims to advance the lives of street children. Take action: Contribute money to a program in Colombia that provides a refuge for children of sex workers where they can participate in art and educational activities.

• Nepal Orphans Home attends to the welfare of youths in Nepal who are orphaned, abandoned, or not supported by their parents. Take action: Buy novels in English that these children can use in book clubs.

Chasing darkness: One reporter’s journey into the night

Finally, here’s another story about appreciation. Illumination often signifies progress. As the Northern Hemisphere’s shortest day yields to its longest night, a reporter with a deep interest in science and space reflects on connecting with the still beauty of darkness.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

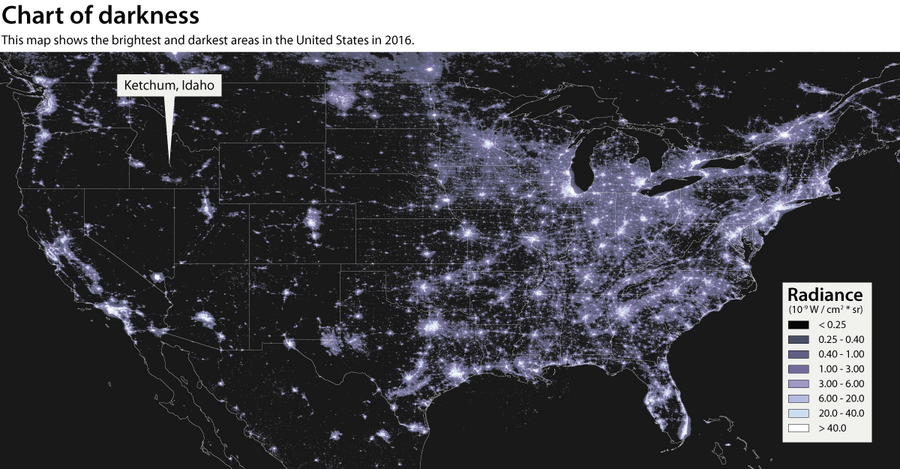

For centuries, the night sky has offered people a window into the universe. Today, however, more than 80 percent of North Americans can’t actually see the Milky Way – and some can’t even recognize it when they do. We’ve built a veil of artificial light between ourselves and the dark depths of space. Streetlights, neon signs, and other electric lights overpower the stars. For some, that brightness is seen as societal progress. But for others, it is a deep loss of humankind’s visceral connection to the cosmos – and for them, that makes darkness something worth fighting to preserve. In central Idaho, with vast public lands and a smattering of small towns, it gets pretty dark at night. Local efforts there to minimize light pollution were recognized just last year when the International Dark Sky association certified a swath of more than 1,400 square miles as the first International Dark Sky Reserve in the United States. On a night this past October, the blanket of stars in the clear Idaho skies is so thick that it’s hard to fathom that each pinprick of light represents an entire solar system.

Chasing darkness: One reporter’s journey into the night

At 5 a.m., it’s too dark to see the fields of volcanic rock and sagebrush that stretch for miles on either side of the highway. But over the beams of my headlights, I get a taste of the view I’m really here for, as a few stars pierce the inky black sky.

Today, our relationship to the cosmos is largely mediated by technology, through telescopes and NASA missions. But for millennia, humans could simply look up on a clear night to marvel at the bright speckles that stretched directly over them. Pondering space was a visceral experience.

But over time, we’ve distanced ourselves from our stellar context, building a veil of artificial light between ourselves and the dark depths of space. Our streetlights, neon signs, and other electric lights are increasingly flooding the night sky and overpowering the stars. As a result, about a third of the world’s population cannot see the Milky Way from where they live. And some people can’t even recognize it. In 1994, when an earthquake knocked out power across Los Angeles in the night, some residents were reportedly so alarmed by the unfamiliar silvery cloud overhead that they called 911.

Still, some people say that a natural connection to the cosmos is worth maintaining. And that means embracing the darkness, and fighting to preserve it.

“The sense of wonder for the night sky is disappearing,” says Steve Pauley, who has earned the nickname “Dr. Dark” for his work on preventing light pollution in Idaho. And that means something vital to humanity is being lost, he says. “What are we without wonder?”

That’s why I’ve dragged myself out of bed hours before sunrise. Like 99 percent of Americans, I live with light pollution, and I’ve never seen a truly naked night sky. So I’m searching for my first glimpse.

With vast public lands and a smattering of small towns, it gets pretty dark at night in central Idaho – arguably one of the darkest places in the country. Just last year, in the wake of local efforts to minimize light pollution, the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) certified a swath of more than 1,400 square miles there as the first International Dark-Sky Reserve in the United States.

Efforts to preserve the darkness in the region began about 20 years ago, when Dr. Pauley, a retired medical doctor and resident of Ketchum, Idaho, noticed the sky overhead was getting brighter at night. “I thought, ‘This is not good,’ ” he recalls.

After researching light pollution, writing a newspaper column, and giving public talks on the topic, Pauley began to catch the attention of city officials. Together, they instituted “dark sky ordinances,” requiring and encouraging residents to eliminate excess lighting in their yards and businesses and to shield light so it illuminates only the intended area. The town has also been certified as a dark sky community by the IDA.

NASA Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite

Value in darkness

About 60 miles north of Ketchum, another Idahoan became enamored with the night sky.

“It seemed to me like one of the real amenities of living in a place like this,” says Steve Botti, mayor of Stanley, Idaho. So when he learned about the IDA’s efforts to designate dark sky reserves, he realized the region was a perfect candidate.

Mr. Botti collaborated with officials in Ketchum, the city of Sun Valley, Blaine County, the Idaho Conservation League, and the US Forest Service to submit an application to the IDA for reserve status. In December 2017, the IDA approved the application and awarded the Central Idaho Dark Sky Reserve with Gold Tier status, the highest ranking for night sky quality.

It makes sense that rural Idaho can get so dark, as light pollution is inherently tied to urban living. But that doesn’t mean we should treat cities as completely lost causes, says Diane Turnshek, an astronomer and lecturer at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

“There’s going to be a lingering place in the [city] center where you’re never going to see [the Milky Way],” she says. “But I think more in terms of how far you have to travel outside the city to see the Milky Way. If you could bring it down from an hour to 20 minutes’ drive, that would be awesome. Many more people would see the Milky Way then.”

Professor Turnshek has spearheaded efforts to reduce light pollution in Pittsburgh. There, and in other cities, like Tucson, Ariz., dark sky activists have convinced officials to switch out traditional incandescent bulbs in streetlights for ones with less glare, like yellow-hued LED bulbs.

Untangling humanity completely from light pollution isn’t really the goal, says John Barentine, director of public policy at the IDA. Artificial light often goes hand in hand with human technological advancement and can provide benefits to society, such as in the form of greenhouses or safety at night. But there may be a happy medium, says Dr. Barentine, such as motion-sensor lights or dimmable bulbs.

Proponents of darkness say it’s worth finding a way to reduce artificial light where we can. Recent studies have found many ways that light pollution damages animals’ natural rhythms, from sea turtle hatchlings to migratory birds, and influences human health.

“But I think we should [reduce light pollution] for its own sake and for how it can improve our overall feeling about ourselves and our world,” Barentine says. “The night sky is something that inspires people. It has for thousands of years.”

‘Never Stop Looking Up’

My own quest for a glimpse of true darkness reveals a disconnect between myself and the circadian rhythms of Earth. By the time I reach a deserted parking lot in Ketchum, the sky has already begun to brighten, and twilight blots out most of the Milky Way. Having never known the true meaning of dawn, I had made a crucial miscalculation. Speaking only to the frosted grasses and mountains around me, I vow aloud to try again as soon as possible.

Two days later, the sky is clear enough for another try.

As I step out of the car, I nervously raise my face up toward the sky. Jackpot! There it is, stretching across the sky as far as I can see. The Milky Way is so vibrant, my eyes don’t even have to adjust to the dark to see it.

I expected to feel a depth to the sky, perhaps as though I was falling into a bottomless pit. Instead, the blanket of stars above me is so thick it is hard to fathom that what lies before me are billions of entire solar systems. In black and white, the whole scene feels surreal.

As I get back in the car, I mentally plan to return, to spend a night beneath these stars so I can marinate in the vastness of the cosmos and my small place within it.

As if my thoughts had been heard, back on the highway I pass a sign that says “Never Stop Looking Up.”

NASA Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Beneath the bowl game glamour

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For US football fans, watching college bowl games is part of the holiday season. Sponsorships – think Cheez-It Bowl – are one reminder that college football has become a big business. Sponsors see their names put before captive viewers. Host cities gain millions of dollars in television exposure. Universities benefit: Alumni pride generates donations. But in major college football the pressure to win means money is too often calling the plays. In 31 states a football coach at a state university is the highest-paid public employee, often earning many times what the state governor does. Overemphasis on “performance” can lead to abuses. This year the University of Maryland’s head coach was fired after a player died at practice. Concussions remain a concern. And racial inequities remain. Black players still graduate at a much lower rate than white players. (The gap has been closing, but at a glacial pace.) Fans who love college football – the excitement, the athleticism – need to care equally for the lives of the young men who are playing it.

Beneath the bowl game glamour

The sponsor names attached to college football’s holiday bowl games have long been a source of amusement. This year’s batch includes the Bad Boy Mowers Gasparilla Bowl, the Famous Idaho Potato Bowl, and the Cheez-It Bowl. The Makers Wanted Bahamas Bowl may raise the most puzzled eyebrows: It promotes an industrial park in Elk Grove Village, a Chicago suburb.

For US football fans, watching college bowl games has become part of the holiday season, sweet treats to gobble at the end of the year (though the biggest bowl games that lead to crowning a national champion now linger long past New Year’s Day).

Sponsorships are one reminder of how college football in the United States has become a gigantic industry, but one with a dark underside.

Cities can gain millions of dollars in television exposure by hosting games. Sponsors see their names and products put before captive viewers. And the universities themselves benefit: Alumni pride in the alma mater’s athletic success can generate stronger ties and more donations. Potential students may see successful schools as desirable places to enroll: Consider the so-called Flutie effect, named after Boston College quarterback Doug Flutie who in 1984 led his team to an improbable win that resulted in a bump in student enrollment at the school.

In major college football the pressure to win means money is calling the plays. In 31 states a football coach at a state university is the highest-paid public employee, often earning many times what the state governor does. University of Wisconsin football coach Paul Chryst, for example, earned $3.2 million in 2018, while Gov. Scott Walker received $147,328; University of Texas head coach Tom Herman was paid $5.5 million, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott $150,000. And so on.

On top of that, many coaches receive bonuses for winning, including for playing in or winning bowl games. But overemphasis on “performance” can lead to abuses. Earlier this year University of Maryland head coach DJ Durkin was fired after a player died during practice. An investigation by ESPN reported that players had been bullied, intimidated, humiliated, and abused by coaches and staff.

Concussions are another source of deep concern at all levels of football, including colleges. This year the NCAA instituted new rules on kickoffs that aim to lower the numbers of these injuries, a step of progress.

But racial inequities remain. Black college football players still graduate at a much lower rate than white players. While the gap has been closing, it’s been at a glacial pace. Since fewer than 2 percent of college players ever play professionally, students on college football scholarships need to be sure they receive a good education.

This year, the graduation rate for all players on bowl-bound teams is 79 percent, up from 77 percent last year. But the gap between white and black players widened to a 90 percent rate for white players and 73 percent for black players, says Richard Lapchick, the director of the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport at the University of Central Florida.

Some of the gap results from the uneven quality of education players receive before attending the university, Mr. Lapchick allows, which speaks to educational inequalities at the grade and high school levels.

At universities, “I like to think academics is listed ahead of athletics for emphasis,” Lapchick says, but for “coaches who value winning at all costs, the student in the student-athlete can often be shortchanged.”

Fans who love all that’s attractive about college football – the glamour, excitement, and athletic excellence on display – need to care equally for the lives of the young men who are playing it.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The gift of Christmas

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mojisola George

The healing, saving message of the Christ brings comfort and cure to yearning hearts in every corner of the globe – not only at Christmas, but every day of the year.

The gift of Christmas

My childhood memories of Christmas in England are filled with twinkling lights, melodious carols, snowmen, and brightly wrapped gifts under a splendidly decorated tree. As an adult, living in Nigeria, I’ve found the Christmas season is still a bustle of festivity and goodwill, including seeing dearly loved relatives and singing inspiring hymns. Throughout the season, the Christmas message recorded so beautifully in the Holy Bible resonates from church pulpits and school plays to articles in the media.

But for some, Christmas is not “the season to be jolly,” as portrayed by the 1862 yuletide carol written by Scotsman Thomas Oliphant. For those remembering a happier time, a wistful look may cross the face; those struggling with illness may feel fear.

Yet beyond commemorating the birth of Jesus, Christmas commemorates the universal, practical message of the incorporeal Christ, the healing manifestation of Love that Jesus exemplified and which he said antedated Abraham (see John 8:58). Can not this healing Christ come to those struggling with sorrow or sickness today?

An experience I had many Christmases ago showed me that Christ is indeed “Immanuel,” which Mary Baker Eddy explains in the Christian Science textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” as “ ‘God with us,’ – a divine influence ever present in human consciousness” (p. xi). My toddler son was unable to keep food down and getting weaker. We were home alone, late at night, without a phone or car to access outside help.

In university, I had become a member of the Church of Christ, Scientist, and my daily Christian study had brought a deeper understanding of the Christ as God’s gift to mankind (see John 3:16). Jesus gave proofs of the practical power of God’s love throughout his life, doing good to all and healing multitudes. He promised that anyone in any age can experience the goodness and healing that come from a clearer understanding of the ever-present Christ and of God, whose very nature is Love itself. For me, the Christ is the best of all gifts and keeps giving not only at Christmas, but every day of the year.

So it’s no surprise that at this frightening time, I reached out wholeheartedly to God in prayer. Almost immediately this thought came: “Does God send sickness, giving the mother her child for the brief space of a few years and then taking it away by death?” I recognized this as a passage from Science and Health (p. 206), which articulates the universal Christ message that heals in line with God’s law.

It was an idea that took away my fear, because in that moment I knew and felt the truth of the answer: No! The nature of God is one of ineffable love for all of His children — for each of us as the spiritual expressions of His goodness.

My son fell asleep peacefully beside me. In the morning he woke up perfectly well and very hungry. What a joyous Christmas it was. All I could think of as we got ready for church that Christmas Sunday was “Thanks be unto God for his unspeakable gift” (II Corinthians 9:15).

Christ, Truth, is the practical proof that we are always with God. Christ’s message speaks to every yearning and listening heart, reveler and mourner alike. It brings healing, comfort, and lasting joy despite the human circumstance. In the Bible, at the time of Jesus’ birth, it came as an angelic message to some shepherds watching their flock that night and as a bright star to the Magi, who faithfully followed it to where the baby Jesus had just been born.

Mary Baker Eddy writes, “I love to observe Christmas in quietude, humility, benevolence, charity, letting good will towards man, eloquent silence, prayer, and praise express my conception of Truth’s appearing” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 262).

This Christmas, as the streets fill with bright decorations, the lights twinkle merrily in homes, and we prepare to give or receive gifts, we can give a different gift: Whether we find ourselves in the sunny warmth of the equator or the snow of cooler climes, we can spare a moment in quiet solitude, saying a prayer for the sick and wistful, acknowledging that God’s gift of the Christ message of peace, comfort, joy, and healing reaches and touches every hungering heart. This is the underlying and overriding substance of Christmas.

A message of love

Remembrance

A look ahead

Have a wonderful weekend. We’ll be back Monday with a look at a festival in the Israeli port city of Haifa that honors Christmas, Hanukkah, and Muslim traditions. The big December gathering is now in its 25th year.

We’ll also deliver a special audio offering: editors’ favorite holiday readings for Christmas Eve. We hope you’ll listen in.