- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- To the moon and beyond: Why China is aiming for the stars

- The Trump effect: How views of an unconventional presidency have shifted

- Ocasio-Cortez gains instant stature in Congress, and social media is a key

- China gets tough on US recyclables. How one Maine town is fighting back.

- The chicken age: Will finger lickin’ fossils define our geological era?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A far-off encounter to unlock new worlds

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

While New Year’s Eve revelers on the US East Coast were counting down to midnight, scientists and engineers at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory were holding their breath. Almost exactly 13 years after leaving Earth on Jan. 19, 2006, the New Horizons spacecraft was set to rendezvous with the most distant object ever explored: Ultima Thule, a bizarre object spinning through the outer reaches of the solar system.

It was hours before the mission team received confirmation that the craft had accomplished its latest task. The message had to travel 4.1 billion miles, after all. Even at the speed of light it took six hours for the transmission to arrive on Earth. And with it came the most detailed glimpse yet of Ultima Thule, which is believed to be a conglomeration of two bodies that collided shortly after the formation of the solar system.

As additional data stream in over the coming weeks and months, scientists hope to glean unprecedented insight into the formation of planets.

Mission scientist Brian May, who earned early fame as the lead guitarist of the rock band Queen, marked the occasion with an original song. In his words: “Limitless wonders in a never-ending sky. We may never, never reach them. That's why we have to try.”

Now, onto our five stories for today, exploring another first for space exploration that hits a bit closer to home, an innovative solution to the US recycling conundrum, and the rise of the chicken as a marker for modern times.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

To the moon and beyond: Why China is aiming for the stars

For Beijing, today's historic lunar landing is as much about cementing global-power status on Earth as it is a foray into the cosmos.

On Thursday a Chinese rover landed where no one has gone before: the far side of the moon. The achievement may be splashy, being a first, but it is just part of the nation’s methodical progression toward becoming a leader in the space industry. And some would argue that China could now be counted among the top echelons of space-faring nations, with human-spaceflight capabilities and more rocket launches than even the United States this year. While other nations have been taking to space at unprecedented rates in recent years, too, China’s path particularly underscores how nations have come to see space exploration as a marker of international prowess. “China has identified space capability as an element of global leadership,” says George Washington University professor John Logsdon. “And clearly China wants to be seen as a global great power in influencing the shape of international affairs, and perceives, as the United States and others have perceived, that space capability is essential to military power, to economic power, and to reputation, to prestige.”

To the moon and beyond: Why China is aiming for the stars

It’s never been done before, even by space-faring nations with decades of experience. But on Thursday, China became the first to land a spacecraft on the far side of the moon.

The Chang’e 4 spacecraft trip is just the latest of China’s space missions. The nation’s burgeoning space program has already sent astronauts into space atop their own rockets, sent several probes to the moon, and has outlined plans for much more.

“China is now a major player in the first rank of space powers, and that’s going to be the reality for decades to come,” says Michael Neufeld, senior curator in the Space History Department at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington.

China is just one of several rising players in the global space arena. Gone are the days of the bilateral space race that was once dominated by the United States and the former Soviet Union. Japan has several missions underway, including its second asteroid sample return mission; the European Space Agency has sent robotic probes to Venus, Mars, and a comet; and India has a Mars orbiter.

But China’s path into the cosmos particularly underscores how nations have come to see outer space and space exploration as a frontier vital to their development and ascendance on the global stage.

“China has identified space capability as an element of global leadership,” says John Logsdon, professor emeritus of political science and international affairs at The George Washington University in Washington. “And clearly China wants to be seen as a global great power in influencing the shape of international affairs, and perceives, as the United States and others have perceived, that space capability is essential to military power, to economic power, and to reputation, to prestige.”

China has been somewhat of an outlier in the landscape of space exploration. The competitive space race of decades past has given way to a spirit of international collaboration, with experienced space-faring nations working together with others on missions.

But China has largely had to go it alone. The US, still the dominant player in the global space scene, prohibits its scientists from collaborating with the China National Space Administration (CNSA) on the grounds that sharing space technology could also reveal insights into US military capabilities.

China, in turn, has seized on space exploration as a venue to display its own technological prowess.

A tricky feat

Being the first to land on the far side of the moon is one such opportunity. It’s a tricky feat.

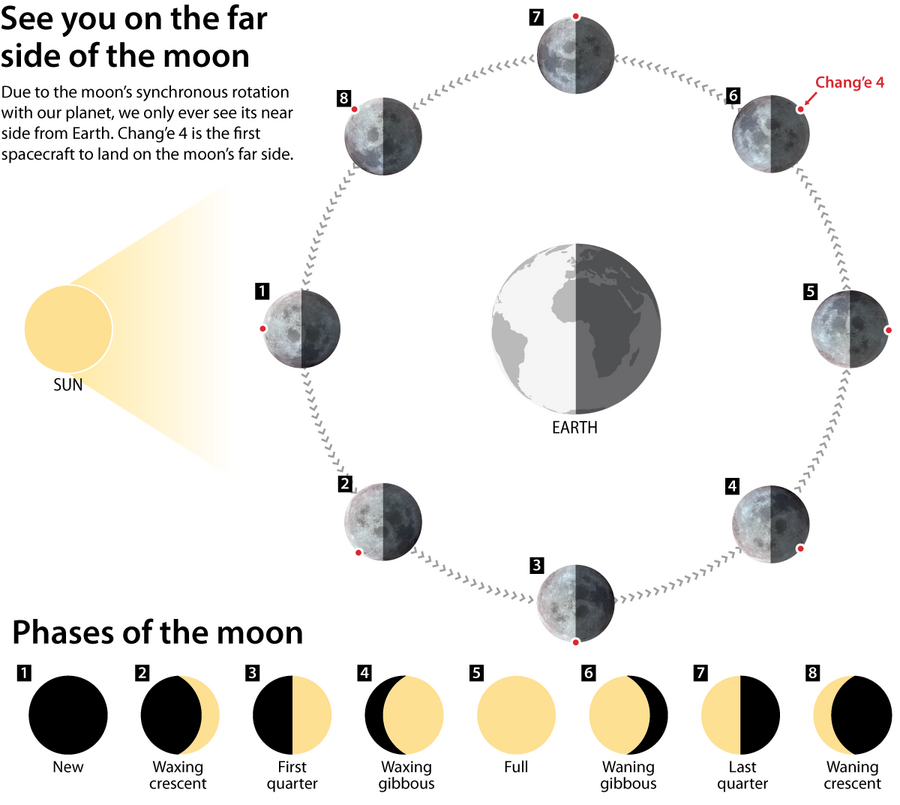

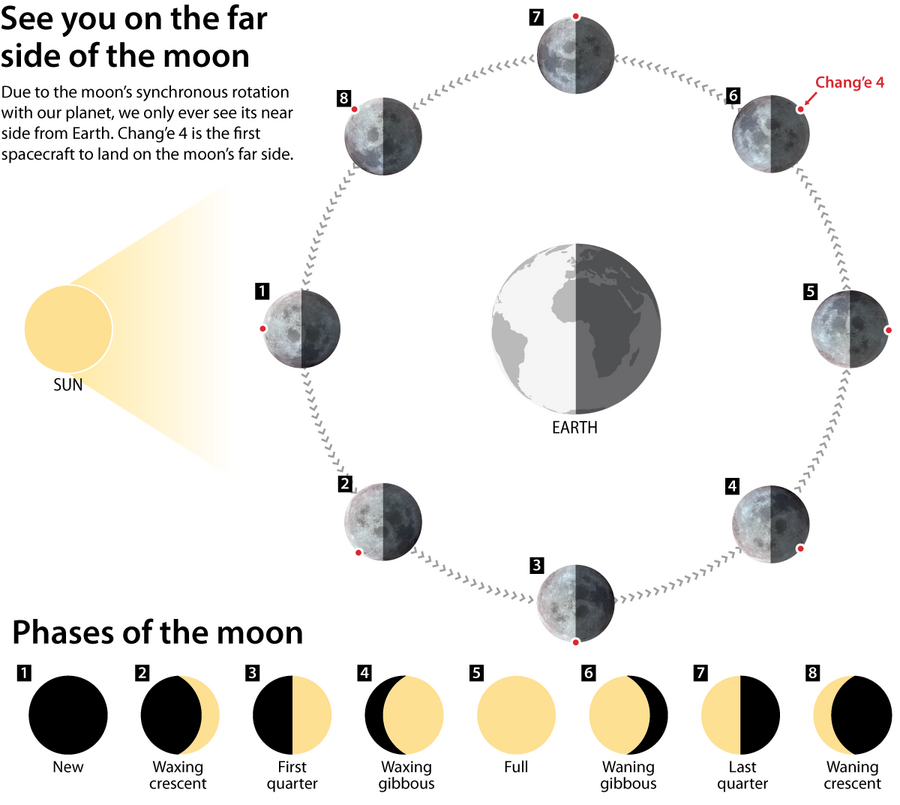

The moon is tidally locked with the Earth, meaning one side always faces toward our planet and one away. As a result, the far side of the moon can’t receive radio signals from the ground. To relay signals to the Chang’e 4 lander, then, China first launched a satellite, called Queqiao.

Although its fourth lunar mission marks a historic first, China’s space agency doesn’t usually target splashy goals.

“This is the first time, really, that they’ve struck out to do something very different and very new,” says Brian Harvey, author of “China in Space: The Great Leap Forward.” “There’s not a mad rush of missions or anything like that. They’re gradually building up a lot of expertise, a lot of knowledge so that they’re in a very strong position” to achieve ambitious goals in the future.

China’s lunar program, Mr. Harvey says, has methodically ticked off the sequence of achievements set out by the US and the USSR during the original space race. The first two Chang’e (pronounced “Chong-guh”) missions mapped the moon from aloft, and Chang’e 3 landed a rover on the near side of the moon. Landing on the far side of the moon was part of the USSR’s plan, too, but the Soviet Union never achieved that, and the US didn’t make it a priority.

The CNSA has ambitious plans for human spaceflight, too. Unwelcome on the International Space Station, due to the US ban, Chinese astronauts aim to establish their own permanent space station by 2020. Already China has launched 11 astronauts into space for increasing amounts of time and technical feats. The nation has also launched two space labs to conduct research and test technologies. A crewed lunar landing could also be on the horizon.

Bold visions

Beyond displaying technological prowess, China is likely using its space program to cast itself as an active participant in the global quest to expand scientific understanding. As a nation facing criticism on the ground for its military posturing and approach to global commerce, China may be seizing on an opportunity to show a positive face to the world, says Andrew Jones, a journalist at the GB Times who covers the Chinese space program.

“What they’re able to do sometimes with the space stuff is present themselves as an outward-looking, sort of looking-to-the-future nation, which is open and looking to contribute to human progress,” he says.

In that spirit of openness, China has invited other nations to send science experiments to be conducted on board its planned space station. For the Chang’e 4 mission, China is working with scientists from Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Saudi Arabia.

This is another way that China is asserting itself as a leader on the global stage, says Dr. Logsdon, particularly as their human spaceflight program takes off. Currently, Russia is the only other nation flying humans into space, although the US is working toward resuming human spaceflight on American rockets. China is also already flying satellite payloads into Earth orbit for other nations.

This is both strategic and economic, Logsdon says. Space has increasingly been seen as rife with economic potential, and charging other nations for rides into space positions a nation well as a global power.

China is also toying with the idea of establishing a crewed lunar base as a gateway to interplanetary human spaceflight. They’re not the only space agency considering this possibility, but such a move would position China to be a major player in the next big phase of space exploration.

So could China emerging as a leader in space exploration shift global priorities in space?

“It’s hard for me to see the point at which the Chinese participation is going to change everything,” Dr. Neufeld says, partially because the Chinese space program is not highly visible internationally, and partially because the space world is already multinational.

But, he says, “it’s adding to human space capability.” Having more space-faring nations means more money to support these expensive endeavors, more engineers to improve technology, and more possible mission targets.

The far side

It may make for poetic song lyrics and album titles, but there isn’t actually a dark side of the moon. But there is a far side of the moon, as our planet’s satellite body always shows the same face to Earth.

The far side of the moon is, however, metaphorically dark, in that there’s still a lot to learn about it. But that may be about to change. China has dispatched humanity’s first robotic envoys, the Chang'e 4 lander and rover, to the previously unexplored region of the moon, offering scientists a new vantage point on the cosmos.

A two-faced moon?

Observations from aloft by both astronauts and orbiters have helped scientists map the entire surface of the moon. But that data revealed some puzzling geological distinctions: About a quarter of the near side of the moon is made of basalt, but only 2 percent of the far side contains the volcanic rock. The far side is also heavily cratered, while the near side appears smoother.

Named for the Chinese moon goddess, the Chang’e 4 rover is set to explore the 110-mile-wide Von Kármán crater. Scientists think an impactor punched through the surface of the moon, kicking up material from beneath the surface in the process. Geologic data collected by the mission could reveal insights into how the Earth-moon system formed, or even the evolution of the solar system more broadly.

An unobscured view of the stars

Landing on the far side of the moon is a tricky technological feat, because the moon blocks signals from Earth. But scientists think that also might make it an ideal place to conduct radio astronomy observations. The Chang’e mission will test that idea by looking to the stars as well as down to the lunar ground.

The gardening rover

The Chang’e mission isn’t just studying what it finds on the moon, it’s also setting up a sort of lunar biology laboratory. According to Xinhua, China’s state-run news agency, the probe carried a sealed container of potato seeds and silkworm eggs to the moon. The idea is that, if the eggs hatch and the seeds germinate, the plants would release oxygen through photosynthesis and the larvae would produce carbon dioxide, creating a simple ecosystem in the container. This would give scientists a chance to study how life might behave in the low gravity of the moon.

The Trump effect: How views of an unconventional presidency have shifted

Supporters see his norm-busting approach as good for the country at the same time that critics view it as dangerously unstable. Is he sowing chaos or being unconventionally effective?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

In the Trump era, the abnormal has come to feel normal. But to say that invites a backlash from the president’s critics, who have warned from Day One against “normalization,” a way station to acceptance, they say. “Even the instability is coming to feel stable, because it is now so accepted,” says Barbara Perry, a presidential historian at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. And yet … There’s another way to look at this presidency. President Trump has, controversially or not, gotten a lot done using the legitimate levers of power, either by going through Congress or through executive action. He has changed the tax code, eliminated key elements of the Affordable Care Act, pulled the United States out of major international agreements (Paris climate accord, Iran nuclear deal), reformed others (US-Mexico-Canada trade), gone hard after China’s trade practices, and announced a pullout of all US troops from Syria and a drawdown from Afghanistan. “Part of it is, just keep the economy growing, and have people realize that on balance, their lives are dramatically better,” says former House Speaker Newt Gingrich.

The Trump effect: How views of an unconventional presidency have shifted

From the start, Donald Trump has tested a “chaos theory” of the American presidency.

Countless norms of a modern White House have vanished, as the ultimate outsider chief executive has done things his way. President Trump has churned through top advisers and Cabinet secretaries at a record pace, dramatically changed the form and content of presidential communications, embraced the politics of government shutdowns, and announced breathtaking policy shifts that have caught even senior aides and world leaders off guard.

A year that began with a short shutdown ended with a long, partial one, as Mr. Trump blew up Congress’s plan to extend funding for a quarter of the government over funding for a Southern border wall.

From the profoundly important to the trivial, Year Two of the Trump presidency matched Year One for sheer drama. Five former Trump aides faced prison time in matters both related and unrelated to the inquiry into Russian meddling in the 2016 election. A Supreme Court nomination merged with the #MeToo movement into must-see TV. Trump barnstormed the country to boost Republicans – and his 2020 prospects – but a blue wave flipped the House, setting up a potential collision course in 2019.

Then there’s the spectacle of a top Trump adviser’s spouse – George Conway, conservative lawyer and husband of Kellyanne Conway – regularly tweeting harsh criticisms of the president. Weird? Yes. But we’ve gotten used to it. We also barely blink, it seems, at news reports that might have engulfed other White Houses, such as hush money payments to mistresses and The New York Times’ year-long investigation into Mr. Trump’s family wealth. To the president’s supporters, it’s all more “fake news” or at best a sideshow; to opponents, it’s just more evidence of outrageous business as usual.

In the Trump era, the abnormal has come to feel normal. But to say that invites a backlash from the president’s critics, who have warned from Day One against “normalization,” a way station to acceptance, they say.

“Even the instability is coming to feel stable, because it is now so accepted,” says Barbara Perry, a presidential historian at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

No wonder “House of Cards” and “Veep” have folded. The most fertile imagination of TV writers scripting over-the-top fictional presidencies can’t compete with reality.

And yet …

There’s another way to look at this presidency.

Trump has, controversially or not, gotten a lot done using the legitimate levers of power, either by going through Congress or through executive action. He has changed the tax code, eliminated key elements of the Affordable Care Act, pulled the United States out of major international agreements (Paris climate accord, Iran nuclear deal), reformed others (US-Mexico-Canada trade), gone hard after China’s trade practices, and announced a pullout of all US troops from Syria and a drawdown from Afghanistan.

Consider also the economy – still strong on the fundamentals, despite the year-end plunge in the markets. In a Monitor interview, former GOP House Speaker Newt Gingrich says Trump’s reelection depends on both continued economic strength and working with the newly empowered Democrats in Congress.

“Part of it is, just keep the economy growing, and have people realize that on balance, their lives are dramatically better,” says Mr. Gingrich, an informal Trump adviser. (See sidebar for more of our interview.) “Part of it is, focus on common-sense solutions on health care, and a bipartisan approach on infrastructure.”

Ari Fleischer, former press secretary in the second Bush White House, sees another imperative heading into 2020: outreach to minorities, who went heavily against Trump in 2016.

“The way he expands his base is by talking and showing that he cares about people who don’t come to his rallies,” Mr. Fleischer says.

Whether these measures are even available to Trump, after two years of tumult and no-holds-barred rhetoric, is debatable. Add to that the sirens coming from the left warning of Trump as a wannabe autocrat. “I alone can fix it,” candidate Trump thundered at the GOP’s 2016 convention. As president, now a self-described “nationalist,” he routinely praises the iron-fisted rule of strongmen the world over, from North Korea and China to Russia, Turkey, and the Philippines.

The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University warns of the “extraordinary authority” Trump has available to him – 136 emergency powers “from the minor to the catastrophic,” including seizing control of the internet and declaring martial law.

But so far, at least, the reality of Trump’s executive actions hasn’t matched the fears.

“His rhetoric does reflect an excessive view of inherent power,” says Jonathan Turley, a constitutional law scholar at George Washington University. “But he hasn’t actually used it.”

Trump’s use of executive power is in line with that of his predecessors, Mr. Turley says. And when Trump’s unilateral actions have been reined in by judges – such as the so-called ban on immigration to the US from some predominantly Muslim countries – his administration has followed the edicts of the courts.

“He has given no indication that he is prepared to defy judicial authority,” says Turley. “And he hasn’t ordered agencies to ignore judicial orders. So thus far, he does not have a record that raises the specter of authoritarianism.”

Furthermore, Trump has even managed, on occasion, to preside over significant policy reform with strong bipartisan support in Congress. On Dec. 21, he signed the First Step Act, criminal justice reforms that are deemed modest but nevertheless represent the most significant changes to the system in decades, including scaling back mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug felons. Trump and his senior adviser son-in-law Jared Kushner had pushed hard for the bill in the face of conservative resistance.

Yet on that very same day, Trump also presided over the start of the third government shutdown of the year – this one partial, but by far the longest – when he held firm on demanding more than the Democratic position of $1.3 billion to add more barrier structures to the US-Mexico border.

Two years in, the first American ever to assume the presidency with no governing or military experience seems as untethered by convention as ever – using the levers of power at his disposal, taking stands on his core issues (immigration, trade), and bucking hard-line conservatives when it suits him (criminal justice reform).

There is little that’s routine about this presidency, but a certain rhythm has set in. Quiet days are followed by bursts of activity and provocative tweets, like the programming of a TV drama. His ever-shifting cast of advisers has learned to let Trump be Trump, because they have no choice.

And along the way, this president has had a profound impact on the country.

At the barber shop

Ron Miller – provider of “fantastic haircuts,” by his own reckoning – used to serve a politically diverse clientele at his one-chair barber shop in rural Greene, Maine. Then Trump got elected. Now, Mr. Miller says, people who disagree with his conservative politics don’t come to his shop anymore – even customers of 20 years’ standing.

“I’ve been told, ‘I’m not going to support you because you’ve supported President Trump,’ ” says Miller, a retired Navy diver with a bushy horseshoe mustache. His walls are crammed with memorabilia, including two stuffed deer heads, a Bush poster, and a well-worn Make America Great Again cap.

“You can’t be a Democrat or you can’t be a Republican and have an opinion without the other person hating you,” Miller says. “I’ve seen people in the town that don’t talk to each other anymore.”

Just an hour south, in Maine’s largest city, Portland, it’s not hard to find folks from the other side of the divide. Lynn Jennings and David Silk, just finished with a long morning bike ride, have nothing good to say about the Trump administration as they sip coffee in a local cafe.

“Two years down, two to go,” says Ms. Jennings, a former Olympic runner. “Every day feels like it’s worse than the day before.”

Mr. Silk, a lawyer, recalls coming of age during the Nixon era, and how the president used the tools of government to do away with opponents. “Growing up in that time, I had a distrust of government,” he says. “It took a long time to get that trust back. And now” – he snaps his fingers – “it’s gone again, just like that.”

The two Maines – a predominantly liberal coast, a conservative-leaning interior – reflect a national divide that Trump has exacerbated but did not create. In their new book “Identity Crisis,” political scientists John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck conclude from survey data that the American public contains “reservoirs of sentiment that serve both to unify and to divide.” And in 2016, it was the polarizing rhetoric of the presidential candidates that sowed division among voters in their communities.

“What gave us the 2016 election, then, was not changes among voters. It was changes in the candidates,” the authors write.

Trump’s scorched-earth rhetoric dominated the campaign and activated a new coalition of traditional conservatives and white working-class voters. But Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton didn’t help when she labeled half of Trump supporters “a basket of deplorables.”

Americans, in fact, agree on much when it comes to defining national identity. A December 2016 survey by the bipartisan Democracy Fund found that American identity is centered on beliefs, not race or religion. Most Democrats and Republicans agreed, for example, that “respecting American political institutions and laws” and “accepting diverse racial and religious backgrounds” were important to being American.

But since Trump’s election, Americans’ views on immigration have grown more polarized. Take the question of whether unauthorized immigrants should have a path to citizenship, provided they meet certain requirements. Since 2013, Democrats have held steady in their support of this view (77 percent), as have independents (66 percent), says Robert Jones, chief executive officer of the Public Religion Research Institute.

PRRI’s numbers among Republicans present a different picture: Until late 2016, GOP voters’ support for a path to citizenship held consistently around 55 percent, then between 2016 and 2018, support dropped to 39 percent. Republican support for deportation has jumped from 28 percent to 42 percent.

“On that question, there is no other explanation than the presidency of Donald Trump,” says Dr. Jones. “I don’t believe Trump invented the conditions; racial tensions and anti-immigrant feeling were latent, and he brought them to the foreground.”

Jones also posits that the ascendance of Trump represents a profound shift in the definition of America’s “culture wars.”

“In 2004, we were talking abortion and same sex marriage,” he says. “Today, those kind of issues have been nearly replaced by identity questions: who gets to be an American, who doesn’t, what it means to be an American.”

Ask Trump voters open-ended questions about how he’s doing, and they often point to the economy first, then immigration, trade, and court picks, all happily. Any complaints? The tweets. The mouth. How his brash style can step on good news and hurt his own cause. But even there, the message is mixed: Yes, he could dial it back on Twitter, but they like hearing directly from the president. And it’s the media’s fault that he’s not popular, and Congress’s fault that he can’t enact his agenda.

“As things evolved, I think the economy seems to be doing well,” despite the downturn in the markets, says Joseph Rattay, a commercial banker in Cleveland. “He’s trying to make good on his promises with border security. He’s making headway with good trade agreements…. Overall, he’s trying to do what he campaigned on.”

Karen Kramer, a software developer from north of Columbus, Ohio, says she was leaning toward someone else in the 2016 GOP primaries but came to like Trump.

“I do feel like he speaks from the heart and that he’s really trying to do the best for our country,” says Ms. Kramer.

She also sees a religious dimension to the Trump presidency, and likes that he’s trying to “preserve a bit of the culture.”

“I am tolerant of other religions, but I also feel like my faith and the Christian religion have really been oppressed, actually,” she says. “I feel just glad that he’s willing to say openly that he believes in God or that he’s celebrating Christmas.”

The view from Caldwell Farms

Rural Androscoggin County in Maine, which includes the town of Greene, is in a way emblematic of the Trump revolution. In 2012, all but four towns in the county voted to reelect President Barack Obama. In 2016, all but one town voted for Trump.

It’s not hard to find satisfied residents. Ralph Caldwell, a farmer in Turner, says businesses here are more optimistic and expanding. “Just look at Caldwell Farms,” he says. “We’re selling more beef than we were, and we’re buying more replacement cattle than we were…. Folks who work for a living, we think he’s wonderful.”

Mr. Caldwell’s only complaint about Trump is that he has “let [special counsel Robert] Mueller stay around. He should have shut off their funds.”

Over in Lisbon Falls, four women friends are gathered at Chummy’s Diner for their monthly breakfast, and are eager to talk politics with a visiting reporter.

“The economy is better,” says Karen Hanlon, who worked the polls on Election Day. “Unemployment is so low. I just wish he’d do more about immigration, but his hands are tied.”

Her friend Monique Gayton also strongly supports Trump, but wishes he would “put a zipper on his mouth.” Still, she and her friends believe the media has been too hostile to the president. Fox is the only network that’s been supportive, Ms. Gayton says, and “if CNN could put a dagger in his throat, they’d do it.”

Public opinion hasn’t budged

One remarkable aspect of the Trump presidency, a roller-coaster ride of “did that really just happen?” moments, is the stability of public opinion. From the start, Trump’s average job approval rating in major polls has consistently held between the high 30s and mid-40s, with disapproval in the low to mid-50s.

“Most people were locked in in their views of Trump, pro or con, from Day One – really even before – and they still are,” says Carroll Doherty, director of political research at the Pew Research Center.

Trump, in fact, is the most politically polarizing president of any going back to Dwight Eisenhower, based on survey data from Pew and Gallup. In the first 19 months of Trump’s presidency, he has averaged 84 percent support among Republicans and 7 percent support among Democrats in Pew polls.

Beyond ever-greater polarization, Americans are also more likely to say that political conversations with people they disagree with are “stressful and frustrating” – and the change is largely among Democrats.

“The worst thing about his presidency is that he has given people permission to be their worst, to be horrible,” says Tasha Judson, a hairdresser and Millennial who grew up in coastal Maine.

In Boston, several African-Americans interviewed agree with Ms. Judson’s assessment. “He opened a can that can’t be closed. When Obama was in office we didn’t have any of this – any of this toward black people or immigrants,” says Candy, who asked that her last name not be used.

Eddy Remy says “politics is politics,” but he objects to the president treating the White House like a reality TV set. “He thinks it’s all a game. He thinks this is ‘The Apprentice.’ ”

In the press room

Time was when White House reporters could count on a press briefing three or four times a week – even in the Trump era. It was an opportunity to question the press secretary about the issues of the day.

In mid-2018, that all changed. The frequency of direct communication from Trump increased – tweets, short question and answer sessions with reporters, and media interviews. The daily briefing nearly vanished.

“If you can hear directly from the president and the press has a chance to ask the president of the United States questions directly, that’s infinitely better than talking to me,” press secretary Sarah Sanders told Fox News in September.

White House reporters and scholars on presidential communications disagree.

“We’ve definitely lost something by losing the daily briefing,” says Martha Joynt Kumar, who studies White House-media relations from her perch in the West Wing press area.

Reporters have lost the regular opportunity to put their questions, on the record, to the press secretary in public, she says. And the White House has lost a valuable source of intelligence on what the press – and by extension the public – is clamoring to know.

“It’s useful for the press secretary in dealings with the president and with staff,” says Ms. Kumar, an emeritus political science professor at Towson University in Maryland. “It can help the press secretary uncork information from the inside. A press secretary can say, ‘Look, I’m getting a lot of questions on that.’ ”

In a way, Trump has become his own press secretary, just as he has made the job of White House chief of staff even tougher than usual, by chafing at the order a typical chief tries to impose. These are among the new norms of the Trump era.

In front of the lectern

“This is what Washington looks like when you have a president who refuses to sort of go along to get along.”

That’s acting White House chief of staff Mick Mulvaney speaking on Fox News soon after the latest government shutdown began. But it’s an observation that can apply widely. Trump does things his own way – including an unorthodox approach to facts and the norms of public civility.

Still, Trump also regularly demonstrates behavior that is conventionally “presidential.” For example, he showed compassion toward the families of young shooting victims at a recent White House meeting to unveil the report of his school safety commission.

But “President acts presidential” isn’t a headline. “President calls porn star ‘Horseface’ ” is. Some media’s emphasis on the negative and outrageous can skew coverage. Trump supporters focus on outcomes and tolerate or minimize his style.

“Separate the signal from the noise,” former Trump aide Steve Bannon often advises.

Trump critics see the power of the presidential bully pulpit and its potential (or actual) harm to overall public discourse.

How much Trump bears blame for a wider decline in public civility – a trend that was already well under way when he entered politics – is open to debate.

“It’s an important question,” says Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania. “The presumption is, someone who gains a great deal of national exposure and carries the legitimacy of the presidency has the capacity to normalize something.”

Trump’s rhetoric at rallies and in tweets certainly strays, at times, from the norms of acceptable public discourse – and rally-goers at times follow suit. But in the 2018 midterms, there was no evidence that major candidates were able to duplicate Trump’s style with success.

“We haven’t seen [Trump’s style] spawn successful imitators, and that’s good news” for the norms of political rhetoric, Ms. Jamieson says. And despite Trump’s perpetual cries of “fake news,” public trust in media rebounded in 2018, according to polls by Gallup and the Poynter Institute.

Looking ahead to the campaign trail

Both Gingrich and Fleischer are avatars of a Republican Party that no longer exists. And both, in their own way, are trying to help shape the party’s future.

Gingrich, who speaks with Trump regularly, preaches his own version of “The Art of the Deal” – compromise with Democrats where possible, and let lawyers deal with the investigations.

The former speaker says he’s told Trump “some of his tweets don’t help him at all.” But “he’s been very effective on big things.”

Fleischer seems less sanguine about 2020. “Trump is not positioned well,” says Fleischer, co-author of a 2013 GOP report on the party’s future.

He agrees that the new House Democratic majority gives Trump a convenient punching bag. And the Democrats certainly might overdo it on investigations and impeachment, and move “too far left” in their presidential nomination process, he says. But Fleischer sees the drubbing Republicans took in the midterms as a warning sign for 2020, because of what it showed about GOP weakness with women and minorities.

The numbers on race are stark, as Fleischer laid out in a recent op-ed at FoxNews.com: In 2000, when George W. Bush was first elected, 81 percent of American voters were white. In 2016, the figure was 71 percent. By 2020, it will be even lower.

“Every successful politician maximizes their base, gins up turnout from their base, and then adds to it,” Fleischer says in an interview. “Trump’s done two of the three.”

But given his style, can Trump really hold his base and attract new support at the same time?

“That was the point of my op-ed,” says Fleischer. “He has to figure out how to do both or it won’t be enough.”

Staff writer Story Hinckley contributed to this report from Maine and Boston. Christopher Johnston contributed from Ohio.

Gingrich to Trump: Time to compromise

Newt Gingrich left the House speakership in 1999, but he’s still full of ideas – and is now an informal adviser to President Trump.

Compromise is the name of the game in a divided government, Mr. Gingrich says in a Monitor interview. He knows; he won the speaker’s chair after fomenting the “Republican Revolution” of 1994, and then worked across the aisle with President Bill Clinton on significant policy initiatives, including a balanced budget and welfare reform, though he also later advocated for Mr. Clinton’s impeachment.

There’s a certain irony in such collaboration: Come to power as a revolutionary, then play “let’s make a deal” with your adversaries. But it’s what most Americans want for Mr. Trump and the newly empowered Democrats, polls show. Below are lightly edited excerpts of Gingrich’s Monitor interview, which took place before the partial government shutdown:

What’s your advice for Trump, given the divided Congress?

He has a real opportunity to reach out. You may have noticed the 46 freshman [House] Democrats who wrote a letter to their leadership saying that they got elected to legislate, not just investigate. I think it would be helpful for him to put together a number of bipartisan initiatives, starting probably with infrastructure.

He also will continue to focus on economic growth. It’s a big advantage for him and poses a challenge for the Democrats, who I don’t think want to become the party of higher unemployment and slow growth.

Will Trump be able to work with congressional Democrats even as they investigate him?

He has to understand – and I think he does – that investigations are just part of the game. He has to just hire lawyers and let them take care of it, and focus on being president.

Do you see Trump’s election and presidency as part of your own legacy, as author of the GOP’s agenda – the Contract with America – in the 1994 midterms?

No, no more than it’s part of [President Ronald] Reagan’s legacy or [Barry] Goldwater’s legacy. I think all of us have been trying to move the country in the same general direction, away from big centralized welfare-state bureaucracies and away from weakness in foreign policy. In that sense, there’s some continuity between Goldwater, Reagan, the Contract with America, and Trump.

So how has he done?

He’s been very effective on big things. And on small things, at times he’s unnecessarily self-destructive. I’ve told him, I think some of his tweets don’t help him at all.

Does Trump need to expand his base to win reelection?

Sure. Part of it is, just keep the economy growing and have people realize that, on balance, their lives are dramatically better. Part of it is, focus on common-sense solutions on health care and a bipartisan approach on infrastructure.

Reagan was at 35 percent approval in January of 1983, and two years later, carried 49 states. So Trump is actually currently slightly stronger than Reagan, despite the most consistently hostile news media in American history.

Did you see warning signs for Trump in the 2018 midterms?

Not really. He’s going to have to communicate to a broader coalition. But I think the other side has problems, too. When you look at the Democratic Party, it’s going to have a substantial amount of internal tension.

Can’t Speaker Nancy Pelosi keep Democrats in line?

No, I think that’s a fantasy. Plus when you get to the presidential campaign, all the pressure’s going to be on the candidates to move to the left.

Do you think Trump has changed the country or its people?

Well, he’s certainly changed it, in the sense that we have a lot more people working today. And we have a lot more people who understand that the United States has the right to stand up for itself. In that sense, he has moved us back toward a much healthier reliance on the United States rather than reliance on international agreements as a way of getting things done.

– Linda Feldmann / Staff writer

Ocasio-Cortez gains instant stature in Congress, and social media is a key

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has drawn attention, in part for her use of social media. The congresswoman represents a new kind of politician maximizing this direct line to the public.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Like her or not, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is the face of a new kind of public official: one who is part politician and part social media influencer, willing to share her personal life as much as her policy positions. Her social following has given her an outsize voice as a congressional Democrat as her party retakes control of the House this week. (She’s bucking the party leadership on one early vote.) The raw style comes with pitfalls – and it’s hard to tell how well it will translate into real influence when it’s time to govern. But politicians have long embraced new forms of communication. Representative Ocasio-Cortez is the latest to build on that history. “A lot of people outside of Washington are mistrustful of this overly self-edited, curated style, where everything you say is poll-tested before you say it,” says Zach Graves of the Lincoln Network, a nonprofit focused on the ties between technology and government. “The personal, empathetic connections that you can make by telling stories that lend themselves well to these platforms are valuable.”

Ocasio-Cortez gains instant stature in Congress, and social media is a key

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has hardly sat down before she whips out her phone to record the chaos around her. Her fellow members-elect talk above the noise in the packed room. The media jostle each other against the walls.

A minute later, the story pops up on her Instagram feed.

“All right, it’s time to pick out our offices,” Ms. Ocasio-Cortez says in the video. “What’s up? We’re getting our numbers!” She means the lottery numbers that decide the order by which new members get to choose their quarters on Capitol Hill.

“People do lucky dances and rituals and such,” she writes in her next post. “Apparently last time someone did a backflip.”

Since her surprise primary victory in June against top House Democrat Joe Crowley, Representative Ocasio-Cortez – and her social media stream – has become a newsmaking machine. Her daily life regularly makes headlines, whether she’s joining sit-ins or doing laundry, giving pep talks or making mac and cheese. In this case, she’s documenting new member orientation week in a series of real-time posts.

Depending on where on the political aisle you stand, she’s either a genius or a joke. But like her or not, Ocasio-Cortez is the face of a new kind of public official: one who is part politician and part social media influencer, fluent in digital strategy and willing to share her personal life as much as her policy positions with the public. And while her raw style comes with pitfalls, Ocasio-Cortez’s outsize stature speaks to its draw – and its potential to change, for better or worse, how politicians communicate with constituents.

“This is a bit of a milestone, for a freshman member to have this kind of impact and following before being sworn in,” says Brad Fitch, president and chief executive of the Congressional Management Foundation. “It may not affect public policy, but another part of [Congress’s] role is to articulate the broader views of constituents in the halls of power. She has certainly already done that.”

And to the degree she successfully cultivates a public following, that may help her very real aspirations to influence the wider debates on public policies, from education to immigration or social justice. Now a sitting House member, she bucked her own party leadership and opposed a rules package Thursday over a spending provision that highlights the divide between the party’s progressive and more centrist wings. [Editor's note: The previous sentence was updated after a rules-package vote.]

“I’m one who believes that the progressive movement is the future and that we have to be fighting for health care as a right, wages, jobs and criminal justice reform, humane immigration," she says. Social media, she adds, keeps her in constant contact with both the movement and her constituents. “Because of that, I can really get a pulse on what’s going on every single day.”

Politicians as media innovators

Technology has always dictated how officials communicate with their constituents. One reason Congress set up the US Postal Service in 1775 was because lawmakers then thought that for democracy to flourish, representatives had to be able to connect easily with the public. The House and Senate were also early adopters of the telephone switchboard, installing them in 1898.

By the 1930s and ’40s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was using radio to broadcast his fireside chats and explain his policies to the American people. Former Speaker Newt Gingrich seized power in the ’90s with the help of C-SPAN, which televised his late-night speeches to an empty House floor.

By 2009, about 30 percent of congress members had Twitter accounts. Today, all of them do, even as the president announces policy decisions online.

Ocasio-Cortez builds on that history, bringing Congress fully into the age of Instagram. Her feed gives an unprecedented look into the life of an elected representative in a way that makes her seem more, not less, human. “She’s tremendously relatable,” says Daniel Schuman, policy director at the social welfare organization Demand Progress. “How often do you get to see inside the Democratic Caucus meeting?”

It helps that Ocasio-Cortez is who she is: a Latina progressive who not only beat out a white, male establishment Democrat, but who also, at 29, became the youngest woman to be elected to Congress. But other members – including 85-year-old Sen. Chuck Grassley (R) of Iowa – have also successfully embraced the medium, which shows how much Americans value what they perceive to be authentic interactions with their leaders.

“A lot of people outside of Washington are mistrustful of this overly self-edited, curated style, where everything you say is poll-tested before you say it,” says Zach Graves, head of policy at the Lincoln Network, a nonprofit that looks into the ways technology and government can work together. “The personal, empathetic connections that you can make by telling stories that lend themselves well to these platforms are valuable.”

Social media: ‘authentic’ but challenging

This direct, “be-yourself” approach to constituent communications could mean better accountability and transparency – at least on paper. In some ways, it is helpful for members to take the temperature of their constituency through social media. And it aligns with the kind of energy that’s swept the Democratic Party’s progressive wing with the arrival of this freshman class, which was elected to take on the establishment and take action in an environment of gridlock, write Casey Burgat and Charles Hunt in a recent analysis for the Brookings Institution.

Still, it can be hard for congressional staff to draw meaningful conclusions from a set of tweets or Instagram comments. There’s no easy way to tell whether a post is from an honest voter or someone with an agenda, posing as one. Social media monitoring also pushes Congress, already experiencing a drain on expertise, to put more resources on messaging instead of on policy and research.

It’s also easy to draw fire when you’re always the center of attention. Conservative media has loved to hate her, criticizing everything from her plans to support a Green New Deal to her decision to take a week off over the holidays for “self-care.”

It’s not just the right. The Washington Post recently called her out for falsely claiming that the Pentagon had “$21 trillion in accounting errors” that could have gone to financing Medicare For All, one of her keystone issues. She called Politico “fake news” after the site reported that she was looking to unseat Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D) of New York in 2020 – a comment that led Donald Trump Jr. to send his own tweet of sympathy.

And as the new Congress prepared to open, she found herself criticized as a “shiny new object” by outgoing Sen. Claire McCaskill of Missouri, a tiff that highlighted inter-party rifts between centrists and the left.

These tangents have led some to wonder whether or not her style will get in the way of governance. “You can be overexposed, and then you’re seen by your colleagues as a showboat when you want to be more of a workhorse,” especially as a freshman, says Betsy Fischer Martin, executive director of the Women and Politics Institute at American University. “It’ll be interesting to see ... what she’s doing with her platforms.”

Ocasio-Cortez, however, seems to believe in her approach – and the public seems to love it. In less than two months, her Instagram following soared from about 800,000 to 1.2 million. She says she tries not to overthink every post, that her goal is to help the public understand how Congress works from the inside.

“When you’re a normal constituent, one of the biggest frustrations is like, ‘Why can’t we just get Medicare for all passed?’ Or, ‘Why is my representative’s office in such a difficult-to-attain place?’ ” she says. “It’s important to show people what these processes look like.”

Social media can lift that veil, she adds. “It has the potential to really show your authentic member as themselves. And that can be a great thing.”

China gets tough on US recyclables. How one Maine town is fighting back.

Beijing’s 2018 crackdown on recyclables was widely decried as a disaster for global recycling. Facing rising recycling costs, cities like Sanford, Maine, have found innovative ways to respond.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Can you recycle responsibility? Instead of blaming China for cracking down on trash in recycling, one city in Maine cleaned up its act. Until 2018, no one much cared that Americans were throwing hair dryers, garden hoses, and Christmas lights in their recycling. Then China got fed up, triggering a spike in costs. One day this summer, the city of Sanford, Maine, got a notice from their recycling facility, ecomaine: In just 15 days, they had racked up thousands of dollars in fees for exceeding the rate of contamination – i.e., nonrecyclables – in their curbside recycling. So the city ramped up enforcement, instructing recycling truck drivers to leave behind what was not recyclable. That sparked weeks of obscenity-laced tirades from residents. But Sanford held firm, and in less than a month it cut contamination rates from 15 to 20 percent to as low as 0 percent per truck. “The problem is not ecomaine enforcing. The problem is not China rejecting contamination,” says Matt Hill, director of Sanford Public Works. “The problem is that people are just not paying attention to what we do with our waste.”

China gets tough on US recyclables. How one Maine town is fighting back.

At the peak of the recycling crisis here, Kayla LeBrun almost pressed the panic button that summons the police. As the administrative assistant at the Sanford Public Works Department, she was on the front lines of an ugly battle – one that had been triggered half a world away.

Residents stormed into the office and set her phone ringing off the hook. They demanded to know, in language that can’t be printed here, why the city’s recycling service was suddenly refusing to pick up things they’d always collected – like plastic grocery bags.

In short, the answer was that China – the No. 1 destination for US recyclables – had cracked down on imports of “recycling” that was laced with trash, and had even stopped taking certain materials altogether. That had driven up the cost of business for US recycling facilities, which in turn started charging municipalities for banned items mixed in with recycling. Sanford, seeking to avoid $100,000 in unexpected fees, abruptly ramped up enforcement of its recycling rules.

That didn’t go over well with many of the city’s 21,000 residents, who pay the highest taxes in York County despite the fact that their household incomes are well below the county average. And on top of that, they pay for each bag of garbage they put out on the curb. So when recycling trucks refused to pick up their recycle bins because of violations, that meant a more expensive trash bill.

“Well, I’ll just throw it in the street,” screamed one lady who had stuffed her recyclables into a 50-pound nonrecyclable dog food bag. Other angry residents stood in front of the recycling trucks and refused to move; one individual even threw a paint can at a truck driver, injuring her.

The company that collects Sanford’s recycling, Casella, was spending as much as two extra hours a day, at a rate of $140 per truck per hour, examining recyclables and leaving orange warning tags for offenders.

But both they and the city held firm. Within just a few weeks, Sanford’s contamination rates – the percent of trash mixed in with recyclables – dropped from 15 to 20 percent to 0 to 3 percent.

At a time when many American cities and towns face steep costs for their recycling programs, leading some to dump their recyclables in landfills or stop collecting them altogether, Sanford’s example offers an alternative path forward. It shows how, at a time when developing countries such as China are raising their environmental standards, the United States can take greater responsibility for the waste it produces.

“The disruption to American recycling markets is in the long term going to be good for the United States from an economic and environmental perspective,” says David Biderman, chief executive of the Solid Waste Association of North America, who says the reduced dependence on a foreign market will boost jobs in the US while also spurring innovation at home. “I think it’s reinvigorated a discussion about reducing waste in the first place.”

Why Sanford didn’t play the blame game

America’s recycling rates have more than tripled over the past 30 years, to nearly 35 percent of total waste produced.

Yet that track record is marred by “wishcycling” – people putting everything from lobster shells to Christmas lights into their recycle bins. In just a few weeks this summer, Sanford residents tried to recycle a hair dryer, coffee grounds, diapers, a dog run chain, stuffed animals, pool toys, blinds, a car mat, a vacuum cleaner, and a cooler.

“They need to get rid of this thing, and here’s a bin that gets picked up every week, so why not give it a shot?” says Matt Hill, director of the Public Works Department in Sanford.

So long as China was taking America’s recyclables, no one much minded. But when Beijing implemented its “National Sword” policy in early 2018, everyone suddenly cared a lot more.

One day this summer, Ms. LeBrun opened a shocking bill from ecomaine, the Portland-based company that processes Sanford’s recycling. The company, facing a 50 percent drop in revenues as the new Chinese policies created a glut of recyclables in the US, was charging municipalities for exceeding the certain contamination rates. In just 15 days, Sanford had racked up thousands of dollars in fees.

LeBrun immediately brought the bill to Mr. Hill, who calculated that at this rate, it would cost the city about $100,000 in fees a year. He started flipping through the city’s contract with ecomaine.

“There was the opportunity to point the finger at ecomaine,” he says, but the city decided instead to work with ecomaine and Casella to address the underlying problem. “The problem is not ecomaine enforcing. The problem is not China rejecting contamination. The problem is that people are just not paying attention to what we do with our waste.”

Beyond the curb

From the giant bay at ecomaine where Casella and other trucks dump their loads, it takes just 3.5 minutes for recyclables to be whizzed along a conveyor belt through a series of sorting areas, which include everything from workers picking out particular kinds of materials to high-tech optical sensors that trigger bursts of compressed air under certain items in order to separate them into a different channel. The workers and whirring machines process as much as 18 tons an hour, making it difficult to achieve China’s ultra-low contamination rates of 0.5 to 1.5 percent, depending on the material.

“We can clean up the load, but we’re doing it by hand,” says ecomaine chief executive Kevin Roche. “None of the automation is helping with contamination – that’s all manual.”

The day the Monitor visited ecomaine, the facility had just sent a shipment of paper to a mill in West Virginia under new ownership – from China.

In effect, US subsidiaries of Chinese firms are becoming part of the solution to US recycling challenges. Faced with the Beijing-imposed decline in imported recyclables, some of them are seeking to rebuild their profits by expanding into US markets.

A subsidiary of Chinese firm Nine Dragons Paper, ND Paper LLC had bought the mill this fall for $62 million in cash. The company, which was only formed this year, is one of at least several China-linked outfits that have set up shop in the US after Beijing’s shift, says Brian Boland, vice president of government affairs and corporate initiatives at ND Paper.

Some 60 percent of American recycling consists of paper, and until 2018 China took more than half of that paper. That created a whole subset of companies in China that used that material to make recycled paper products. So, when starved of their core material, some have started buying up paper mills in the US, including ones that had been shuttered.

ND Paper is in the process of hiring 130 people to reopen a mill in Old Town, Maine, says Mr. Boland. The company has also announced it will invest in a new recycling operation at its plant in Rumford, Maine, next year, giving facilities like ecomaine a destination far closer, and cheaper, than China or even West Virginia.

“Really, the Rumford mill is our biggest hope,” says Mr. Roche, the ecomaine executive.

A model for other communities

Such stateside solutions make a lot of sense to Hill of Sanford’s Public Works.

“If China can do all this with the recycled material, why aren’t we doing it?” he says, citing the cost of transporting a mounting volume of recyclables halfway around the world to be turned into recycled materials. “Why does it have to go over there and then come back here? Why can’t it just be done here?”

Sanford, Casella, and ecomaine’s partnership shows that it can be.

“It definitely could be replicated across the country,” says Kenneth Blow, who oversees Casella’s operations in Sanford and beyond, and says a number of towns have dramatically reduced their contamination rates. “All the municipalities have worked very well with us…. It was a lot of work, a little bit of a struggle, but it’s been successful.”

What can I recycle?

Unfortunately there is no simple answer, as it depends on the collection system and sorting facility used by your city or town. But your Department of Public Works will thank you if you depart from the world of “wishcycling” – crossing your fingers as you throw everything from pool toys and stuffed animals to coffee grinds in your recycle bin, hoping they will be taken away – and spend a few minutes educating yourself.

Here are a few tips:

- Check your town or city’s website for a guide to recycling. Many communities or even states post a “recyclopedia” of what’s allowed and what isn’t.

- Just because something is marked with the triangular recycling symbol doesn’t mean it can go in your curbside recycling. The biggest culprit is plastic grocery bags, which will gum up the machines at most facilities that take residential recycling. Most local grocery stores will recycle such bags, so bring them on your next shopping trip – and/or invest in reusable bags.

- Food containers, particularly pizza boxes, can be too dirty to recycle. Scrape off that extra cheese, or only recycle the top half of the box.

- Remove all plastic film, such as that found on the top of yogurt containers. Refrain from putting in long stringy items, like garden hoses or Christmas lights, which tangle up the fast-moving sorting machines and can cause injury to facility employees.

- Don’t forget about the first two parts of the recycling triangle: Reduce and reuse.

The chicken age: Will finger lickin’ fossils define our geological era?

Over the past several decades, humankind has reshaped the domestic chicken into a creature highly tailored to our needs – so much so that its fossils may prove to be the defining markers of our geological era.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Peter Ford Global correspondent

Geological periods are frequently marked by the fossilized creatures that they feature. The Jurassic Period had dinosaurs. The Pleistocene Epoch had woolly mammoths. For us, in the modern Anthropocene Epoch, the defining animal may prove to be the chicken. That’s what a group of British scientists argues in a recent study. They say that the Anthropocene – characterized primarily by the huge impact humans are having on their planetary environment – will be clearly demonstrated in the changes wrought in the humble chicken over the past several decades. Subjected to intensive breeding programs and high-tech rearing farms, the average contemporary chicken is much taller and five times as heavy as its predecessor in 1961. Today’s birds are not just fatter; their bigger bones have completely different genetic and biochemical structures from their antecedents just seven decades ago. And there are a lot of chickens: The world eats more than 60 billion chickens a year, and the standing population is around 23 billion. “Broiler chicken fossils will be abundant worldwide and recognizable as new and distinct,” says Jan Zalasiewicz, one of the researchers. “That makes them good candidates” to mark the dawn of the Anthropocene Epoch.

The chicken age: Will finger lickin’ fossils define our geological era?

Most people, when they take a broiler chicken from their supermarket shelf, don’t give much thought to what kind of a fossil the bird’s bones will one day make.

But Jan Zalasiewicz does. And he is part of a group of British scientists who believe those fossilized bones will provide future paleontologists with a key hallmark of our society as mankind moves into a new geological epoch.

The Jurassic Period had dinosaurs. The Pleistocene Epoch had woolly mammoths.

We, it seems, have chickens.

For one thing, there are a lot of them. The world eats more than 60 billion chickens a year, and the standing population is around 23 billion, according to a University of Leicester paper published recently by Professor Zalasiewicz and a team of colleagues.

And today’s broilers are nothing like the chickens our grandparents ate. Subjected to intensive breeding programs and high-tech rearing farms, the average contemporary chicken is much taller and five times as heavy as its predecessor in 1961.

“Broiler chicken fossils will be abundant worldwide and recognizable as new and distinct,” says Zalasiewicz. “That makes them good candidates” to mark the dawn of the Anthropocene Epoch, he adds.

The Anthropocene, many scientists suggest, is a new unit on the geological timescale, characterized primarily by the huge impact humans are having on their planetary environment. They date its beginning to the mid-20th century.

The humble domestic chicken is a good example of that, the University of Leicester team says. The denizens of modern battery farms would barely be recognizable as Gallus gallus domesticus to ancient Roman farmers, or indeed to American farmers before 1948.

That was the year the US Department of Agriculture organized the “Chicken of Tomorrow” contest among poultry breeders, with the goal of “one bird chunky enough for the whole family – a chicken with breast meat so thick you can carve it into steaks,” as The Saturday Evening Post put it.

That launched the modern global poultry industry that has made the broiler chicken the most numerous bird species on earth (40 times as large as the global sparrow population) and probably the most numerous in history.

It also led to “the most extreme and rapid change ever seen in the body of an animal,” says Zalasiewicz. “Evolution normally takes millions of years; this has taken just a few decades.”

That is because of the technology brought to bear – computers controlling broiler farms’ heat, humidity, light, and grain distribution to maximize growth rates in carefully bred birds. “Left alone these chickens couldn’t survive,” points out Carys Bennett, lead author of the University of Leicester paper. “Their body mass is too much for their legs and their hearts.”

Today’s birds are not just fatter; their bigger bones have completely different genetic and biochemical structures from their antecedents just seven decades ago.

That will be clear to future scientists digging through geological strata, and their job will be made easier by the manner in which we dispose of chicken bones.

Wild bird carcasses are scavenged and generally disappear from the geological record. But most chicken bones are thrown into plastic-lined landfills, an anaerobic environment in which organic material tends to mummify, rather than decay, which means it will eventually fossilize.

Chicken bones will not be the only markers of the putative Anthropocene Epoch. The Earth, and we ourselves, have all become slightly radioactive since the United States and other powers began staging atmospheric nuclear tests in the 1950s. Plastics have also become a ubiquitous marker of the modern age; most handfuls of beach mud and other sediments now accumulating contain plastic microfibers.

But “chickens are the only example of a new and distinct future fossil coincident with the Anthropocene,” Zalasiewicz says. They are also “pretty symbolic” of mankind’s priorities, he adds. The poultry industry “shows the scale of our transformation of our biosphere. We’ve converted it into feedstock for humans.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Where age is a state of mind

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Media reports Thursday noted much about Rep. Nancy Pelosi as she was elected House speaker for the second time. Yes, she is again the most powerful woman in American politics, the chief adversary of President Trump, and the nation’s third most senior official. The dog-that-didn’t-bark: any major focus on her age. Even though she is the oldest person to hold the speaker’s gavel, the general silence may be a sign of a shift toward a less ageist society. (Journalists were almost as little focused on the age of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who is the youngest woman ever elected to Congress.) Such thinking defies the gloom of demographers about, in particular, the fast-growing cohort of older people around the globe, and the alleged burden they might bring. “Everywhere, people are embracing aging as a privilege rather than a punishment,” writes Carl Honoré in a new book, “Bolder: Making the Most of Our Longer Lives.” “They are aging better and more boldly than ever before. As a result, chronological age is losing its power to define and constrain us.”

Where age is a state of mind

As self-designated watchdogs on government, the news media were remarkably quiet Thursday about one aspect of Rep. Nancy Pelosi as she was elected House speaker for the second time. Yes, she is again the most powerful woman in American politics, the chief adversary of President Trump, and the nation’s third most senior official. But the dog-that-didn’t-bark: a major focus on her age.

Even though she is the oldest person to hold the speaker’s gavel, the general silence may be a sign of a shift toward a less ageist society. In fact, journalists were almost as little focused on the age of one new House member, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who is the youngest woman ever elected to Congress.

Ms. Pelosi herself has contributed to this new quietness about age. Last year, she said age has “nothing to do” with choosing people for Congress. “If you have a problem with somebody who is older, run for office,” she told CNN.

Such thinking defies the gloom of demographers about the fast-growing cohort of older people around the globe and the alleged burden they might bring. Last year, for example, the World Bank warned of economic “headwinds from aging populations in both advanced and developing economies.”

To Paul Irving, chairman of the Milken Institute Center for the Future of Aging, such predictions are simply not accurate. They are “a byproduct of stubborn and pervasive ageism.” While some older adults cannot maintain an active lifestyle, he writes in a recent Harvard Business Review, “far more are able and inclined to stay in the game longer, disproving assumptions about their prospects for work and productivity.”

Any news stories that did focus on the ages of Pelosi or other top leaders tend to reflect what writer Carl Honoré calls the “still syndrome.” In a new book, “Bolder: Making the Most of Our Longer Lives,” he says we persist in using phrases such as “he’s still working” or “she’s still sharp as a tack.”

The underlying message: Anyone engaging with the world after a certain age is a minor miracle. Such a perspective only boxes people into narrow paths when, if anything, we are in a “golden age” for older people, he writes, based on three years of research.

“Everywhere, people are embracing aging as a privilege rather than a punishment. They are aging better and more boldly than ever before,” he states. “As a result, chronological age is losing its power to define and constrain us.”

The chief obstacle for “seniors,” he says, is not their bodies or minds but stereotypes. Perhaps in largely ignoring Pelosi’s age (or the youth of new members of Congress), the media may be shedding such tropes and their self-fulfilling tendencies. They are learning to drop the “still.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

True womanhood without limitations

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

With today’s swearing-in of new members, the 116th US Congress includes a record number of women. In light of this, today’s contributor explores the topic of womanhood and the boundless value that true womanhood holds for the world.

True womanhood without limitations

It is noteworthy that today there were a record number of women sworn in as members of the 116th Congress of the United States. While work toward gender equality is certainly not finished, it is encouraging to recognize every step of progress.

Progress in the equality of opportunity comes from a lot of hard work and dedicated effort on the part of both women and men. But at the base of such progress, I feel there’s also a leavening of humanity’s thoughts about womanhood itself. In particular, many have gained a new sense of womanhood based on a better understanding of the nature of God. Over the years I have enjoyed pondering Bible references in conjunction with my study of Christian Science that depict the nature of God as both masculine and feminine, Father and Mother. It has helped me to better understand the infinitude of God’s nature and therefore the boundless nature of each of us as God’s image and likeness. For example, there’s this passage from Isaiah that conveys a sense of God’s motherhood when He promises to care for the entire people of Israel: “As one whom his mother comforteth, so will I comfort you” (Isaiah 66:13).

Christian Science has helped me see more clearly that true womanhood is expressed in spiritual qualities, and is not materially defined. True womanhood includes the integrity and strength of selflessness, especially when difficulties arise, and the ability to perceive the power of God to overcome evil in whatever form or circumstance it appears. These spiritual qualities bring wonderful blessings to human experience.

An inspiring biblical example where the qualities of true womanhood are on full display is that of a woman named Abigail, described as “a woman of good understanding” (I Samuel 25:3). She was married to a surly man named Nabal, who for no obvious reason refuses food to David, who would later become king, and his men, even after they had showed kindness to his shepherds. After this rejection, David’s anger is fueled, and he is set on killing Nabal and all his men.

When Abigail hears of this, she gathers food, drink, and even sheep as gifts and goes out to meet David. Regardless of her husband’s bad character, Abigail appealed to David’s higher nature and pleads with him to show mercy to Nabal and spare his life. David yields to Abigail’s appeal, and recognizes the action she took as a great blessing to him and his men.

Today the expression of noble qualities such as unselfed love, forgiveness, and mercy couldn’t be more needed – in our homes, communities, governments. Undaunted by cowardice and timidity, individuals who have learned to assimilate such qualities show mercy even when it seems undeserved – because they discern goodness as the true, spiritual nature of every man and woman. Through their knowledge of divine Love’s care and protection for everyone, they help others rise to this true goodness and do the right thing.

Mary Baker Eddy, the Discoverer of Christian Science, yearned to lift the consciousness of both men and women to the true sense of manhood and womanhood based on the truth of God and of God’s creation. As a woman of the 19th century, what she herself overcame and accomplished went far beyond the traditional role of women of her time. She discovered Christian Science, and with persistence, trust in God, and great courage and spiritual strength, she faced every imaginable obstacle while she explained and demonstrated the spiritual essence of Christ Jesus’ teachings and pointed the way for all of humanity to follow his example. And she established the Church of Christ, Scientist, and founded this newspaper.

Stressing that both men and women truly include the complete spiritual reflection of God’s motherhood and fatherhood, Mrs. Eddy wrote in her primary book, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “The ideal man corresponds to creation, to intelligence, and to Truth. The ideal woman corresponds to Life and to Love. In divine Science, we have not as much authority for considering God masculine, as we have for considering Him feminine, for Love imparts the clearest idea of Deity” (p. 517). Her deep understanding of God as Love enabled her to lift human consciousness to the perception of true womanhood; and both her example and her ideas have helped to lessen stereotypes and limitations placed on men and women, showing that such limitations have no basis in Spirit.

A knowledge of the womanhood – and manhood – of God’s creating gives us dominion in human experience. As I’ve prayed to see the feminine and masculine qualities of God as constituting the spiritual individuality of myself and others, I’ve begun to see more clearly that these qualities are immortal and thus are as limitless as divine Spirit. The expression of spiritual qualities cannot be limited or restricted by age, gender, economics, or rank. No condition of lack or oppression can block their expansive influence where there is the desire to be and do good.

A message of love

Congressional reset

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when Henry Gass takes us to the US border, where two towns – one in Mexico and the other in the United States – are learning from each other about water conservation.