- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- US-China trade: How dose of reality is pushing both sides to deal

- Why Guatemala’s 180 on corruption matters for Central America

- What does it mean to be ‘conservative’ in the Trump era?

- How a polluted Massachusetts mill town is reclaiming its future

- In the Sahara, a vast emptiness etched with a thousand paths

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What a missile scare taught one artist about peace

If you were in Hawaii a year ago this Sunday, the phrase “this is not a drill” might recall 38 minutes of soul-searching.

That’s how long it was before a text alert about an incoming missile was rescinded by the state’s emergency management office. Tensions were high with North Korea, adding credibility to the threat.

Todd Schauman, a colleague then living there, was at a youth basketball tournament. The gym doubled as a shelter. “We were there with many local families,” he says. “There were some good conversations, and the tournament organizers helped promote calm.”

Another dad, who worked in civil air defense, talked about the systems in place and calmly worked his phone. His own “stand down” came before the state’s. Play resumed.

The Hawaiian musician Makana had a more prolonged reaction. After confirming that most of the world’s nuclear arsenal is gripped by the US and Russia, he went to work – and then he went to Russia.

Inside an old Soviet bunker he recorded a song – the acoustics are dramatic – that’s been released for the Hawaiian anniversary. In the video that accompanies it he passes through a crowd of young Russians who look as though they, too, might have gathered for some game. It’s a scene of personalities, not politics.

“My intention is to inspire and remind us all to humanize one another,” Makana says, “to dignify and be curious about each other.” Those connections, he says, are the path to security and peace for us all.

Now to our five stories for your Friday.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

US-China trade: How dose of reality is pushing both sides to deal

Look away from the US southern border. Bravado and self-assurance have stoked tensions over trade for the world’s two largest economies. We look at what’s shifting as both sides see the risks of a trade war.

Prospects have brightened that a 90-day bargaining push between the United States and China could succeed. The reason: Contrary to a tweet by President Trump 10 months ago that trade wars are “good,” evidence is mounting that souring ties are hurting both economies, especially China’s. The result is some momentum in long-stalled talks. After midlevel negotiations in Beijing were extended unexpectedly to a third day this week, Beijing’s chief trade negotiator is preparing to travel to Washington for higher-level talks. An easing of tensions could help the whole world economy. But it won’t be easy to close rifts that stem from very different economic strategies. The US is focused on ending unfair practices by China and reducing the US trade deficit. China’s priority is using trade as a tool in its push for rapid technological development. Wendy Cutler, a former trade negotiator, says “There is an incentive for both sides to reach an agreement, but I don't think that means that they're willing to reach an agreement at any cost.”

US-China trade: How dose of reality is pushing both sides to deal

It’s been 10 months since President Trump shocked the world with a tweet saying that trade wars could be “good, and easy to win."

Lately, evidence has been accumulating suggesting just the opposite. Tariff Man, as the president described himself in a tweet a month ago, is looking much more like Trade Negotiation Man. And Chinese officials appear less assured that they can weather the two nations’ nascent tariff war.

Why?

Economic pressures. Specifically, US stock markets plunged before Christmas, followed by a warning of slowing revenues from bellwether tech giant Apple. And China’s economy showed signs of deterioration in December, with both factory output and retail sales weakening. Both were caused, in part, by existing tariffs and fears that there were more to come. And they are pushing Washington and Beijing to reach a deal.

“Both sides are finding out that trade wars are painful,” writes Mary Lovely, professor of economics at Syracuse University, in an email. “The Chinese economy is slowing…. Foreign investment into the US is down, and there is concern about domestic investment moving forward.”

For Mr. Trump, the key barometer is the US stock market. When it plunged last month, in part because of concerns about a potential trade war with China, that reportedly got the president’s attention. Since then, he has been sounding increasingly positive about US-China talks, and Wall Street has soared from its Christmas Eve low.

Trump may also be feeling he has fresh leverage in talks that stalled last year at a time when officials in China appeared more confident of their own economy’s resilience to a trade storm. Now, rougher economic performance there seems to have changed the mind-set.

“I think China wants to get it resolved. Their economy is not doing well,” Trump told reporters Sunday. “I think that gives them a great incentive to negotiate.”

After midlevel negotiations in Beijing were extended unexpectedly to a third day this week, Beijing’s chief trade negotiator is preparing to travel to Washington for higher-level talks. Those could come as early as the end of this month, US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said.

A good kind of ‘kicking the can’?

Such signs are considered positive.

“It clearly looks like important progress was made as a result of these three days of talks, particularly on issues related to increased purchases [of US goods by China] and maybe some market access” of US firms to Chinese markets, says Wendy Cutler, vice president of the Asia Society Policy Institute and a former trade negotiator. “There is an incentive for both sides to reach an agreement, but I don't think that means that they're willing to reach an agreement at any cost.”

Trade experts say the first step is to reach some kind of deal by March 1 that makes advances in these areas, delays further US tariffs on Chinese goods, and includes a concrete agreement to continue talks on the more difficult structural trade issues that separate the two nations. The administration has threatened that in March it would escalate US tariffs from 10 percent to 25 percent on $200 billion of Chinese goods.

Getting a deal and at least delaying an escalation in tariffs could be a positive, even if it kicks the can down the road on the more difficult issues.

“I can see a good can-kicking scenario and a bad can-kicking scenario,” says Edward Alden, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington. “A good can-kicking scenario is that the administration recognizes this is not a three-month negotiation; it's a three-year negotiation or a 10-year negotiation…. It becomes the beginning of an ongoing negotiation between the United States and China to try to figure out ‘Look, how are the two biggest economies in the world going to reconcile their different systems in a way that allows for greater global stability and prosperity?’ ”

He adds: “A bad [scenario] is you get a weak deal, you declare victory, and and then everybody looks the other way.”

Differing goals for trade

The problem with a face-saving deal is that it would allow a festering of tensions caused by the mismatch in strategic aims between the two nations.

For the US, more balanced trade and level playing fields are the end goals. For China, trade is a tool in its push for rapid technological development and parity with the West. That is why Beijing has been willing to disregard trade rules when it heavily subsidizes certain strategic industries, violates intellectual property rights, and engages in cybertheft to acquire certain Western technology.

Such issues are especially fraught because US officials have been insisting on measures to verify Beijing’s compliance with the promises it makes.

Some trade experts say it’s encouraging that Trump has given charge of the negotiations to Robert Lighthizer, the US trade representative and someone known for pushing for substantive reforms.

“Why trade is fascinating right now is that Trump cares enough about it that he put a serious guy in charge, and therefore we have the possibility of a serious outcome,” Mr. Alden says.

If both sides succeed with an interim deal by March 1, it would take away some of the uncertainty in world markets and lessen US-China tensions, though not eliminate them, says Ms. Cutler. If talks fail, “we'd quickly feel the repercussions. China would feel the repercussions. China would counterretaliate. And I think the global economy would just take a big hit.”

Why Guatemala’s 180 on corruption matters for Central America

Now look well south of the US-Mexico line. In Guatemala, a leader who vowed to curb corruption has changed his tune. We wanted to explore what could happen if institutions can’t check him.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Just a few years ago, Guatemala looked poised to battle corruption. Today, though, its president is battling a landmark anti-corruption commission – and brought the country to the edge of a constitutional crisis to do so. CICIG, as the commission is called, was created more than a decade ago through an agreement with the United Nations. Recently, though, the group has been investigating President Jimmy Morales himself, who once won office with the slogan “Not corrupt, not a thief.” He’s repeatedly tried to limit the commission, arguing that it violates Guatemalans’ rights and sovereignty. This week, he announced he was withdrawing from the treaty and ordered CICIG staff to leave within 24 hours. The constitutional court ruled against his move, but the saga may not be over. Meanwhile, other governments in the region are watching closely. For many years, Central American countries have moved to strengthen democratic institutions. But as many of those gains start to erode and international players scale back their role, some of the region’s leaders are increasingly eyeing their neighbors, taking notes on how far they can go.

Why Guatemala’s 180 on corruption matters for Central America

A constitutional and political crisis has been averted – temporarily, at least – in Guatemala this week, after the Constitutional Court ruled that President Jimmy Morales could not unilaterally expel an international investigative body focused on fighting corruption.

Mr. Morales previously has attempted to muzzle CICIG, as the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala is known. And observers say the court’s ruling isn’t likely to halt government attempts to play down the outsized role of corruption here, particularly with presidential elections on the horizon. The United Nations withdrew the commission members this week after the government’s refusal to guarantee their security.

It wasn’t long ago that Guatemala made a name for itself by prioritizing the fight against impunity and corruption. In 2015, tens of thousands of Guatemalans took to the streets for weeks to demand resignations from the then-president and vice president over a bribery scandal. And Morales was elected to the top office in a campaign where he painted himself as “Not corrupt, not a thief.” In 2016, Morales renewed CICIG’s mandate, allowing it to continue investigating some of the most high-profile corruption cases and criminal networks in the country, working alongside the public prosecutor’s office. But Guatemala’s dedication to rooting out corruption began to sour when cases implicating the business community, former officials, and Morales himself – for illegal campaign financing – started to emerge.

Now lawmakers are threatening to strip the immunity of judges on the very court that halted CICIG’s banishment this week, in an effort to try them for interfering with foreign policy decisions.

Guatemala’s about-face on corruption is telling, both on a national and regional level. In recent years, governments in Central America from Honduras to Nicaragua to Guatemala have flouted decades of both lip service and concrete steps toward strengthening democratic institutions. International players like the United States are scaling back their role holding regional leaders accountable for actions from electoral fraud to repression of public protest, and Central American governments are increasingly eyeing their neighbors, taking notes on how far they can go in eroding democratic institutions.

“What’s happening in Guatemala and how this resolves itself – it’s not just important for Guatemala, but for the region,” says Adriana Beltrán, director of citizen security at the Washington Office on Latin America, a D.C.-based human rights organization. “What’s at stake here is not just whether CICIG stays or not; it’s the future of the rule of law and democracy, and countries not too far away, like Honduras, are watching closely.”

Look and learn

On Monday, Morales said Guatemala was unilaterally withdrawing from the United Nations-backed CICIG, with his foreign minister ordering its staff to leave the country within 24 hours.

Defending his government’s decision at a press conference, Morales was joined by individuals who say they were falsely accused by CICIG investigations. Morales said the body "violated the human rights of Guatemalan citizens and foreigners residing in the country.”

CICIG was created in 2006 to carry out independent investigations on corruption, genocide, and drug trafficking, and its work has implicated three former presidents. The body has been the envy of many citizens in the region seeking an end to the corruption and impunity that plague so many governments here, with 2015 public protests in Honduras over corruption in the social security institute leading to the creation of a similar independent anti-corruption body backed by the Organization of American States (OAS) and known as the Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MICCIH).

But the further investigations have reached, the more enemies CICIG has earned, with critics – now including former supporters like the business community – saying the group is politically motivated and is violating Guatemala’s sovereignty.

This isn’t “just about the president. It’s about the president and his allies,” says Ms. Beltrán, noting that CICIG has been “extremely successful” at shining a light on the extent of corruption in the country, which “extends to every government institution and implicates members of the military and private sector.”

International attention on Guatemala this week has been unflattering, casting the president’s actions as meddling with a body that has roughly 70 percent public approval, according to recent surveys. But it’s a cost that politicians feel is worth paying to undermine the anti-corruption battle at home, says Renzo Rosal, a Guatemalan political analyst and columnist.

“The risk factors aren’t high,” Mr. Rosal says. “There aren’t big public protests like we saw in 2015, the US is far less interested in Guatemala, and the public statements made by US lawmakers don’t have much teeth,” he says. “The government feels the risks are under control, and for that reason they’ll continue bulldozing ahead,” possibly stacking the Constitutional Court with allies – or doing away with the body completely.

“I think everyone in the region is watching each other,” says Rosal, citing how Honduras worked around a constitutional ban on reelection, allowing sitting president Juan Orlando Hernandez to win again in 2017 in an election deemed “irregular” by the OAS (which called for a fresh vote). Guatemala also has a constitutional ban on reelection, which Rosal doesn’t rule out as something the sitting government may try to change.

“Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala – they’re all watching and emulating each other, planting seeds of doubt in the public and creating powerful waves of dubious change in the region.”

A deeper look

What does it mean to be ‘conservative’ in the Trump era?

The outsider presidency has challenged core conservative principles, such as commitment to free markets and limited government spending. So is a new “official conservatism” taking shape?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Many have long used the image of a “tripod” to describe three basic principles undergirding the post-war conservative consensus. First articulated in many ways by William F. Buckley Jr., these principles include wide-ranging commitments to free markets and limited government, Judeo-Christian social values, and a robust national defense. But many see this traditional conservative tripod wobbling in the era of President Trump. And while there has been from the start a vocal cadre of “Never Trumpers” who continue to disavow the president and see him as a danger to long-held post-war principles, others see Mr. Trump’s disruptions as a good thing, overall. They see his election as a much-needed intellectual jolt. “Arguably, Trump has been very good for the world of conservative ideas, because he’s loosened up lots of preexisting orthodoxies – he’s loosened up lots of people’s senses of where they belong and what kind of things they can say,” says Steven Teles, professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University. “Since Trump, a sense of the class nature of the Republican Party has gotten shaken up, and that’s very intellectually generative.”

What does it mean to be ‘conservative’ in the Trump era?

As a conservative writer and thinker, F.H. Buckley has a certain reputation for wit and a wry sense of humor.

A professor at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University, he’s written about the morality of laughter, invoked “the once and future king” to describe former President Barack Obama, and accuses America’s wealthy elites of enjoying “redneck porn,” his term for political stories that objectify all those “deplorables” sniffing Oxy in places like West Virginia.

Yet as he’s become one of the foremost intellectual defenders of the unapologetic nationalism of President Trump, many of his right-leaning peers have begun to question Mr. Buckley’s conservative bona fides, just as they have the president’s.

And the former Trump speechwriter, who volunteered early to help his insurgent campaign, has been in many ways deliberately provocative, appropriating at times a leftist vocabulary to describe the nationalist energies that have come to dominate the Republican Party, and which many say have challenged core conservative principles as never before.

“I had this one moment where a prominent member of Congress talked about the Tea Party as “right-wing Marxists,” Buckley says. “And I thought, ‘Aha, that’s moi.’ ” In Canada, his country of birth, he might have even been considered part of its tradition of “Red Torys,” he says – capitalists and social conservatives who maintained a robust and even enthusiastic support for social safety nets.

“But now, what I really am is a member of the ‘Republican Workers Party,’ ” says Buckley, no relation to godfather of the modern conservative movement, the late William F. A reference to the serious if irony-laden title of his most recent book, “The Republican Workers Party,” Buckley suggests it’s partly a right-wing Marxist analysis of what he sees as an emerging class warfare at the center of American politics today. It’s a party, too, he says, that repudiates the moribund “official conservatism” of well-funded right-wing think tanks and opinion journals.

Many of these have long used the image of a “tripod” to describe three basic principles undergirding the post-war conservative consensus. First articulated in many ways by William F. Buckley Jr. – who also helped build the intellectual and institutional infrastructure of the modern movement – these principles include wide-ranging commitments to free markets and limited government, Judeo-Christian social values, and a robust national defense.

But many see this traditional conservative tripod starting to wobble in the era of Trump. And while there has been from the start a vocal cadre of “Never Trumpers” who continue to disavow the president and see him as a danger to long-held post-war principles, others see Mr. Trump’s disruptions as a good thing, overall – they see his election as a much-needed intellectual jolt.

“Arguably, Trump has been very good for the world of conservative ideas, because he’s loosened up lots of preexisting orthodoxies – he’s loosened up lots of people’s senses of where they belong and what kind of things they can say,” says Steven Teles, professor of political science at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “Since Trump, a sense of the class nature of the Republican Party has gotten shaken up, and that’s very intellectually generative.”

Roots in ‘classic liberalism’

As a matter of principle, conservatives have often used the term “classical liberalism” to describe the roots of their thinking, especially when it comes to the laissez faire, free-market leg of the traditional tripod. A libertarian ideal that goes back to the European Enlightenment, classical liberalism asserts the autonomy of the individual over the power of the state and claims a fundamental human right to own property and enter into contracts with others.

And such “liberal” economic principles formed the basis of the new global economy. In the 1990s, even Democrat Bill Clinton led his party to embrace the capitalist premises of international agreements like NAFTA, the idea that global free trade could create a “virtuous cycle” of economic growth and new working middle classes in countries once called the “Third World” but now labeled “the developing world.”

These new middle classes, now with money to spend, would create even more economic growth and its members would naturally gravitate toward liberal democratic values, many believed. Investors were giddy, too, at the prospect of “emerging markets” across the world.

These conservative economic principles, too, were tied to the movement’s traditional focus on a muscular American military. After the fall of communism, a number of “neoconservative” thinkers began to advocate for a more aggressive and proactive use of military force, both to combat terrorism after 9/11 and to protect global supply chains.

“You see them in George Bush’s second inaugural address, where he kind of articulates a kind of American mission,” says Patrick Deneen, professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Ind. “They believed in a much more aggressive American mission of defending and even expanding democracy in the world, sort of seeing their mission in an almost Wilsonian kind of way, making the world safe for democracy.”

Today, both of these pillars of conservatism are under strain. The movement has long included those with more isolationist leanings, of course, but neoconservative thinkers have lost most of their intellectual influence today, and their flagship publication, The Weekly Standard, which was among the most aggressive Never Trump conservative voices, was shuttered last month after its wealthy owners pulled its funding.

“And what you see now, too, even across the world in Europe, is a rejection of the kind of libertarian, globalist economic assumptions of this so-called neo-liberal, or classical liberal, consensus,” says Professor Deneen, author of the 2018 book, “Why Liberalism Failed.” “Now, there’s a much more obviously nationalist economic platform with a strong interest in rebuilding a kind of blue-collar manufacturing base, even to the point of engaging in trade wars to defend American production by imposing tariffs and so forth.”

As a result, Trump conservatives have sometimes sounded a lot like their left-wing rivals. Last month, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D) of Massachusetts said Trump was right to pull American troops out of Syria. Both she and Sen. Bernie Sanders (Ind.) of Vermont and their supporters rail against globalism and “job-stealing free trade agreements” as much as the president and his supporters.

A ‘class warrior’ of the right

Make no mistake, thinkers like Buckley remain committed to free markets and a strong national defense. But as a “class warrior,” he emphasizes certain traditional concerns of the left, including the nation’s gaping income inequalities and growing class divisions, which he says have begun to destroy the social mobility at the heart of the American Dream.

“What does equality of opportunity mean if you’re severely handicapped? What does it mean if you are, for one reason or another, subjected to discrimination?” Buckley says, critiquing a well-known conservative shibboleth. “I mean, it’s not enough to say, ‘Well, we all have an equal shot at it, here you are, here’s a perfect set of contract law rules, so go to it, fella.’ There are certain duties for citizens, as well. Every conservative in every other country well understands that. You know, Margaret Thatcher would never have given up on a Medicare system.”

And he rails against what he calls the rise of “The New Class,” which itself is an allusion to an older description of a privileged Soviet ruling class. Buckley uses it to describe a class of urbane liberal professionals, the top 10 percent of Americans who earn more than $200,000 a year and who “are skilled in the hyper-technical rules and adept in ever-changing Orwellian Newspeak that are employed to exclude the backward, the eccentric, and the politically incorrect.” He includes among this class conservatives like former President George W. Bush, John Podhoretz, and Bill Kristol – another jab at “official” conservatism – as well as those who run the media, educational institutions, and of course the federal bureaucracy.

“And that brought us to the paradox of the 2016 election, when the liberal candidate of a counterrevolutionary and aristocratic New Class was defeated by a revolutionary capitalist offering a path to social mobility,” he writes in “The Republican Workers Party.”

The conservative or “classical liberal” tradition of individual liberty is often based on an abstract universalism, but Buckley argues that a conservative nationalism should have a “special sense of fraternity with their fellow citizens.”

“If you’re a libertarian, as many of the official right-wing thinkers are, you don’t make that distinction,” he says. “But if you’re a nationalist you will say, there are things we provide fellow citizens that we don’t provide noncitizens.”

But he says this is far from ethnically-based nationalism. “There isn’t much room for white nationalism in American culture,” he writes in his book, though he does believe that immigrants like him – he became a US citizen in 2014 – should assimilate. People in other countries may subscribe to the principles of the Declaration of Independence, but “becoming American requires a few more things: American citizenship, and a love for American institutions that aren’t owned by a single race.... It’s not a white culture or a black culture or a Mexican culture. That's why the American who sincerely hates American multiculturalism is something less than an American.”

Still, much of the “America First” critiques of global free markets challenges many of the traditional conservative principles of individualism, given their impact on American workers and the country's growing class divisions.

“The bigger question is whether or not that dissatisfaction represents a real challenge to certain underlying principles, or rather if it really represents a challenge to the way conservatives apply these principles,” says Jonathan Adler, professor of law and the director of the Center for Business Law & Regulation at the Case Western Reserve University School in Cleveland.

“You know, is the discontent with capitalism?” he says. “Or is the discontent with a political system that has injected a large degree of cronyism and government manipulation, a protection of certain industries. The libertarian in me wants to say that it’s the latter, that when people complain about ‘globalist elites,’ they're not complaining about laissez faire so much as they're complaining about the fact that you had certain political elites who talk about things in terms of the market, but act in a way that embraces a significant distortion of the market for the benefit of well-connected industries and well-connected individuals.”

Other proponents of the new conservative nationalism also reject the “blood and soil” white nationalism of the alt-right extremists, and that a focus on the bonds of citizenship retain an American commitment to a liberty and equality that transcends race or creed.

The future of the Republican Party

But many conservatives still see in Trump’s nationalist movement a dangerous tendency toward xenophobia and even racism.

“The future of the Republican Party has no place for Trumpism,” says Lauren Wright, lecturer in politics and public affairs at Princeton University in New Jersey. “The demographics of the American electorate are changing rapidly, and not in the party’s favor. One need not look further than the 2012 GOP autopsy report, in which Republicans promised to do a better job appealing to young voters, minorities, and women, but then did precisely the opposite in 2016,” she says via email.

“Fiscal prudence and free market capitalism have given way to American isolation, protectionism, and national economic insecurity,” continues Dr. Wright. “Family values, moral responsibility, compassion, and a belief in the equality, dignity, and desire of every human being to be self-reliant and free has turned into vilification of immigrants and a fear of the other.”

But Buckley says the third pillar on the traditional conservative tripod, a commitment to Judeo-Christian values, is essential to any classically liberal political system. The Republican Workers Party repudiates “official conservatism,” he says, “because it’s based on a misreading of John Locke, who himself thought that if you don’t ground [classical liberal ideas] in religion, you’re not going to get anywhere.”

He says the Republican Workers Party would never call itself Christian, but in the “Red Tory” traditions in Canada and Britain, religious institutions and people of faith undergird a deep commitment to generous social welfare policies for citizens, and not simply a religiously motivated voluntarism to charity.

“We are in the Judeo-Christian tradition, or in the traditions of religions, and people, all of whom are different from plants and animals, we owe something to each other.”

How a polluted Massachusetts mill town is reclaiming its future

Residents of New England’s old mill towns might be excused for feeling left behind. But in Lawrence, Mass., locals have refused to let abandoned buildings and polluted landscapes define their future.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Ramon Riquel spent the past seven years working at the Crown Cork & Seal factory in Lawrence, Mass. But in March, he was laid off. “They say the plant is down, no more work,” says Mr. Riquel. “It's easy for them, but it’s not easy for us.” Factory jobs have been streaming out of Lawrence for decades. As manufacturers have closed their doors, they have left behind a legacy of pollution and blight. This formerly thriving mill town has become a maze of empty, five-story, brick warehouses deemed brownfields, properties where redevelopment is stalled because of potential pollution. But in recent years, Lawrence has become a center for job training programs that prepare residents such as Mr. Riquel for careers in environmental remediation. Thanks to a patchwork of public and private education programs, many of Lawrence’s majority Hispanic residents have been able to learn a trade while helping to revitalize their community, transforming polluted eyesores into redevelopment opportunities. “Lawrence is going in a new direction,” says Ramon Quezada, who runs a staffing firm for environmental remediation workers. “And we’re helping with that.”

Explore the distribution of New England's brownfields with an interactive graphic here.

How a polluted Massachusetts mill town is reclaiming its future

When Lesly Melendez recalls her walk to school as a child in Lawrence, Mass., she remembers the six-foot-tall fence cloaked in black cloth and decorated with caution tape. “Keep Out” signs warned passersby away from the so-called Dresden of Lawrence, the burned bones of the former Russell Paper Mill.

“As a kid growing up and walking by things like that...,” Ms. Melendez trails off and sighs.

But her childhood neighborhood looks more appealing today. After years of stop-and-start cleanup, the Russell Mill site is now Oxford Site Park, a green welcome mat for the city. It’s an open space with a bike path. Long grasses bend in the wind, free from any fence.

And this park may have helped the city grow opportunity as well as greenery. Lawrence, long one of New England’s poorest and most polluted communities, has become a center for public and nonprofit job training programs. They are certifying locals to clean up brownfields, properties where redevelopment is stalled because of potential pollution.

Job training grants from the Environmental Protection Agency in particular have enabled hundreds of local workers to boost their résumés, lead change where they live, and transform polluted eyesores into redevelopment opportunities.

The city’s success – and its collaborative approach – could offer a model for other low-income minority neighborhoods ridden with abandoned industrial sites. For Lawrence, brownfields like the Russell Paper Mill are about more than jobs and blight. Cleaning up past pollution boosts a community’s self-esteem.

“Brownfields are one of the programs where you really see the connection between environmental justice and opportunity,” says Alexandra Dunn, administrator for the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 1, which includes the six New England states. “Through these grants we can create a very different chemistry in these communities – one that is focused on economic vitality and the future, as opposed to the historic presence of pollution.”

Across the country, hot spots for pollution are disproportionately located in low-income communities such as Lawrence. For today’s young residents, often nonwhite and immigrant families, the legacy of pollution is a stark example of environmental injustice. (Explore the distribution of New England's brownfields with an interactive graphic here.)

Despite its size of only six square miles, Lawrence still has almost 50 brownfields – relics of its former life as a mill town. Yet locals refuse to let black-cloaked fences and caution tape define their future. Melendez, for one, is working to rid the city as much as possible of the symbols of decay she used to walk by. As deputy director of the local nonprofit Groundwork Lawrence, Melendez now helps convert brownfields into clean open spaces.

“Other things happen; other sexier things come up, and people forget that [brownfields] are here,” says Melendez. “But there are plenty of us that live and work here that want to make sure this is a better place for our children, and our children’s children.”

‘Death by a thousand cuts’

By the EPA’s estimation, the United States has more than 450,000 brownfield sites – properties where redevelopment or reuse is complicated by the presence (or potential presence) of a hazardous pollutant. Factories, dry cleaners, gas stations, and many other commonplace properties become brownfields in their afterlife, requiring state or local agencies to monitor for leaked chemicals or buried pollutants.

Though some designated brownfields have no serious contamination, others continue to pollute water, soil, or air for years. Either way, a brownfield designation requires a costly assessment, and possible cleanup, before it can be repurposed.

This requirement is often cost-prohibitive for developers, especially in communities with shrinking populations and thin profit margins for businesses.

These state and locally managed properties may seem inconsequential compared with the country’s federally run 1,338 Superfund sites, which are typically more serious sites of contamination, such as landfills or mines. But the sheer number of community brownfields and the residual blight they leave on communities make them a priority for places like Lawrence.

“Brownfields are among us. Their impact on humans is direct and tangible,” says Justin Hollander, an associate professor at Tufts University in Medford, Mass., and the author of several books on brownfield pollution. “If you talk to someone who lives across the street from one, they would say we need to talk about this now. They continue to represent a real threat to investment in neighborhoods.”

Lawrence today is a maze of empty, five-story, brick warehouses. Some have been renovated into loft apartments with gyms and open-floor plans. Others have blown-out windows and graffiti. It hardly resembles the prosperous industrial center it once was.

Mill companies flocked to New England towns in the 19th century because of their proximity to water power. And Lawrence, located at the confluence of two rivers and a canal, became a hub for both industry and immigrants.

But everything changed in the 1970s and 1980s when mills started to close or move overseas. The Russell Paper Mill site that Melendez passed on her way to school, for example, once had more than 500 employees and made the glossy paper for National Geographic. But industry left the building in 1974, and it sat untouched for years, falling in on itself and occasionally catching on fire as it sat in brownfield purgatory. More than four decades later, industry still trickles out of Lawrence.

“It's kind of like death by a thousand cuts,” says Christopher De Sousa, an urban planning professor at Ryerson University in Ontario who has spent decades studying brownfields in the US. “All of this vacancy makes the neighborhood seem like it’s shrinking and decaying.”

‘Work of the future’

Local resident Ramon Riquel moved to Lawrence from Puerto Rico a decade ago and spent the past seven years working at the Crown Cork & Seal factory. In March he was laid off.

“They say the plant is down, no more work,” says Mr. Riquel. “It's easy for them, but it’s not easy for us.”

As industry languished, the immigrant community once reliant on these sites has continued to grow. More than three-quarters of the city’s population is Hispanic, and nearly 25 percent lives below the poverty level. The average unemployment rate in Lawrence over the past year was 6.5 percent – almost twice the statewide average.

As deputy director of the Merrimack Valley Workforce Investment Board (MVWIB), Susan Almono spends a lot of time thinking about the city's many job seekers, what the industries of Lawrence's future might be, “and how to bring them together to really drive help, drive economic development.”

One of the area’s ripest industries, Ms. Almono realized, was environmental reclamation of the city’s industrial relics, so she applied for a grant from the EPA.

Founded originally as the Brownfields Job Training Program in 1998, the EPA’s Environmental Workforce Development and Job Training Grant program has since awarded almost $64 million across almost 300 grants to recruit, employ, and train unemployed, low-income, or minority locals for jobs in environmental remediation. Since it began, the program has trained more than 17,000 individuals nationwide and placed about three-quarters of them in full-time jobs.

“The jobs training program through the brownfields program truly is a success story,” says Ms. Dunn at the EPA. “It often isn't given headline attention, but it really is an example of EPA and local communities working together.”

Lawrence, a city with around 80,000 people, stands out nationally in remediation employment. The region has the second highest concentration of hazardous removal jobs in the country. The majority of local workers graduate from the for-profit Lawrence Training School, but the MVWIB’s free training programs have made the industry possible for people like Riquel who do not have the resources to pay for a private program.

“We are preparing local residents for good-paying jobs that are accessible to them, and there is a high demand for in our region,” says Almono. “Environmental work is work of the future.”

Before earning its fourth job training grant in the fall of 2017, MVWIB had trained 117 residents, with 82 percent of them finding immediate employment. Almono says the average hourly pay for these workers is $18.21, which is above the state’s $12 minimum wage.

The key to MVWIB’s success, says Almono, has been the program's flexibility. After the first training program, for example, she realized they could expand beyond remediation-specific jobs like lead and asbestos abatement to offer intensive truck driving training.

Almono says they hope to update the program again following Lawrence’s deadly gas explosions in September. Locals see the explosions as yet another example of failing infrastructure and environmental injustice in Lawrence.

Riquel now has his license to drive dump trucks and other vehicles common on a construction or remediation site. Without the EPA-funded MVWIB program, Riquel would have had to pay upwards of $5,000 to enroll in a trucking licensing class on his own.

“All the people over there – they helped me a lot,” says Riquel. “I wouldn't have this job without the program.”

Finding pride in home

Despite imposing numerous funding cuts for environmental programs, President Trump has remained supportive of both the EPA's Superfund and brownfield programs, calling them “absolutely essential” and increasing funding.

“Brownfields have always done well regardless of the administration in power,” says Professor De Sousa. “It's one of the few environmental programs that you can point to that removes blight, brings new development, and brings new jobs…. Politicians love taking pictures with shovels.”

Although safety precautions have improved drastically over the past decade, environmental remediation is still a dangerous job. Low-income minority communities in Massachusetts already have disproportionately higher rates of lead poisoning, and job training programs for low-income minorities in this kind of remediation work could be seen as yet another example of injustice.

But for locals in Lawrence, the work represents opportunity.

“You could always say there are morality issues, but mentally, if you are cleaning an area where you have lived all your life, and it's getting better, it's a sense a pride,” says local resident Ramon Quezada.

Like Melendez, Mr. Quezada grew up in Lawrence. He left the Dominican Republic with his parents in the mid-1980s, following Quezada’s grandmother who moved to Lawrence a decade earlier to work in the mills. And like Melendez, Quezada still remembers the blight he saw as a child.

“I saw all these mills abandoned, and I saw all these burnt homes,” says Quezada.

And like Melendez, Quezada decided to do something about it. Seeing all the work that needed to be done in New England and so many neighbors without jobs, Quezada co-founded Labor on Site, a staffing firm for environmental remediation workers, in the early 2000s. After workers graduate from the MVWIB program or the Lawrence Training School located above Quezada’s office, he helps connect them with contractors.

Last year Labor on Site placed 733 workers, with more than 600 of them coming from Lawrence. Quezada’s records show the firm’s efforts resulted in $4.5 million in payroll, mainly to Lawrence workers.

“Lawrence is going in a new direction,” says Quezada. “And we’re helping with that.”

Explore the distribution of New England's brownfields with an interactive graphic here.

Reporter’s notebook

In the Sahara, a vast emptiness etched with a thousand paths

To two longtime Monitor correspondents on assignment, a step into the Sahara meant adventure. But to others, it represents peril. And to still others, it can mean life and livelihood.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Scott Peterson Staff writer

When two of the Monitor’s longest-serving foreign correspondents visited the Sahara recently, they approached the experience from very different perspectives. For Peter Ford, who had never been to this part of Africa, the trip was a journey of discovery; for Scott Peterson, who had motorcycled across the desert 30 years ago, it was a more nostalgic affair. That mix of memories and novelty added a new dimension to their work together. Scott and Peter were on a reporting trip to Agadez, Niger, a historic trading post that has been the southern gateway to the Sahara for centuries. They were investigating the town’s changing role as a transport hub for migrants heading north to Europe. In the Sahara, they found a desert that means many different things to different people: To its Tuareg inhabitants, accustomed to the trackless wastes, it means life and a livelihood. To many of the migrants, when things go wrong, it means death in the back of a broken-down pickup truck. To Scott and Peter, who share a taste for empty spaces a long way from established towns, it meant adventure. You’ll find more about their impressions in the full read.

In the Sahara, a vast emptiness etched with a thousand paths

In Agadez, one simple, overriding reality imposes itself: the vast emptiness that surrounds this ancient trading post in the southern reaches of the Sahara desert.

Yet, as we found on a recent reporting trip together, that single reality means very different things to many different people. Not least to the two of us.

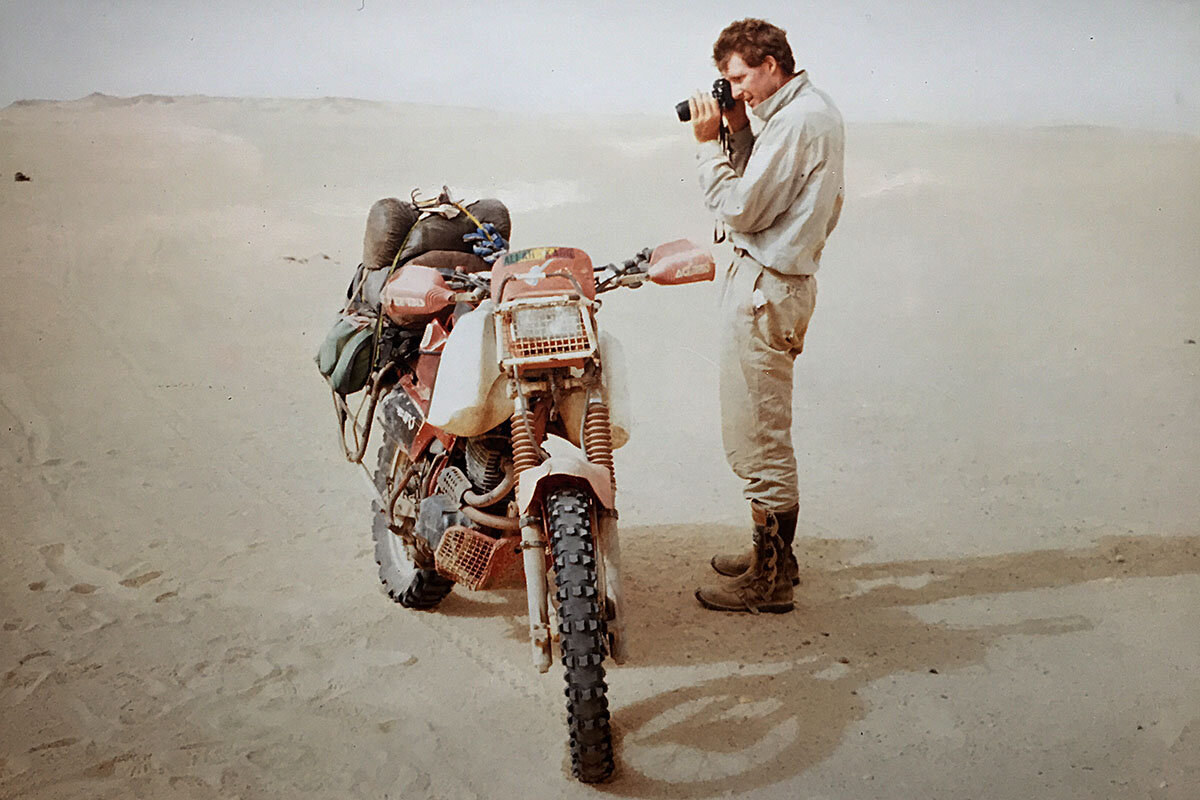

For Scott, the trip recalled his first youthful adventure in these parts, nearly 30 years ago, crossing the Sahara astride a Honda 500cc dirt bike. (More about that later.)

But I had never been this far south in Africa and I was surprised – and a little disappointed – to find that the Sahara starts off as more a stony plain than a sea of sand. And my curiosity was tinged with caution. After all, the British government “advises against all travel” in the Agadez region for fear of jihadi terrorists, and the French authorities “strictly discourage” their citizens from frequenting the area.

That has wreaked havoc with one mainstay of the local economy – tourism. And the Niger government’s efforts to choke off the flow of migrants heading for Europe has toppled the other pillar of Agadez’s prosperity, the transport and guide business.

A crossroads, an oasis

For centuries Agadez has been a crossroads of the desert, an oasis where caravans of camels, guided by desert-dwelling Tuareg tribesmen, would stop to replenish as they carried gold, ivory, and ebony northward, or silks, beads, and pottery south.

For the Tuaregs, the desert means life. It is the place where they have always earned their living from their expertise and survival skills. Once they served camel trains that took 40 days to cross the desert. More recently they have driven the trucks and pickups that carried migrant workers to seek jobs in oil-rich Algeria and Libya in a couple of days.

Now the government has barred the route north out of Agadez, at the instigation of the European Union as it tries to stem the migrant tide. That hasn’t stopped everybody, though. And it means that the drivers who still try to smuggle migrants past the police patrols have to avoid all the traditional paths and drive through the trackless desert, trusting their luck and their GPS.

For many migrants – nobody knows how many – the desert has meant death. Pickup drivers lose their way and run out of fuel in the middle of nowhere, literally. Or their vehicles break down. The stranded passengers don’t stand a chance in the scorching desert heat.

“We saw dead people on the way,” recalled one Nigerian migrant we interviewed who had made the crossing. “You don’t feel comfortable. There’s a lot of desert and no road.”

(To read the series related to this trip, click here.)

The lure of the desert

Scott and I share a taste for empty spaces a long way from civilization (and, truth be told, for going to places our governments tell us not to go to.)

We were able to indulge ourselves, very briefly and accompanied by a truckload of heavily armed soldiers, on a four-hour foray northeast of Agadez along the road that leads eventually to Libya.

The whole of its length is marked only by six-foot-high concrete posts, sometimes planted a kilometer (six-tenths of a mile) apart. As I stared into the distance, awed by the endlessness, I could only imagine what lay beyond the last post that I could see. But I could almost hear Scott’s motorbike revving in his head.

This is what he was remembering as he surveyed the same vista:

Roaring north on my motorcycle in 1990, whipped by the desiccating winds sweeping across the southern edge of the Sahara, I knew the paved road would eventually end.

And it did, just outside Agadez, unceremoniously marking the spot where even Niger’s meager infrastructure ceased to exist. I eased the bike to a stop at the last lip of the pavement, and hopped off. Standing beside my overheated metal steed, I looked out over an endless expanse of sun-scorched earth and desert.

I was on a yearlong journey across Africa, launching my career in journalism by writing freelance stories along the way. The vast emptiness of the Sahara desert back then was to me the embodiment of adventure, of swashbuckling risk-taking, and pure freedom in one of the most inhospitable wildernesses on earth.

I was solely responsible for myself as I rode across that desert for three days and nights in the company of two Dutch bikers, headed northwest for Algeria. The motorcycle was a mess – a secondhand 500cc Honda dirt bike, with its muffler gone and red plastic sides melted from engine heat. But it boasted an oversized fuel tank fitted for long desert rides.

During the hottest hours of the day we created makeshift awnings, tying swaths of cloth to the handlebars of our bikes to make shade. At night I took long-exposure photographs of the stars and the Milky Way, with the bike in silhouette.

I was stepping deliberately into the unknown, riding that motorcycle off the pavement onto the dusty sand track with a youthful sense of bulletproof invincibility, undergirded by equal measures of exuberance and fear.

Decades later, back on that same road to report and photograph a story on African migration to Europe, I found that for both today’s migrants and my own self 30 years ago, the Sahara crossing marked an important step toward the future.

But where I had once discovered opportunity (I wrote my first story for The Christian Science Monitor from Niger back then) migrants were finding a potentially fatal barrier to their dreams. And even those who survive the journey risk being held for ransom by Libyan militia.

My desert had been the epitome of adventure and freedom. Too often, theirs promises nothing but suffering and enslavement.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Behold Greeks giving thanks

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In Greece this week, government leaders gave a big thank-you to visiting German Chancellor Angela Merkel for helping the country become free of massive bailouts. Just five years ago she was denounced for insisting on austerity and strict reforms imposed on a Greece long used to entitlements and tax evasion. The gratitude was more than a “debt of gratitude” or an acknowledgment of mutual dependency. Both sides spoke as if a virtuous cycle of friendship and partnership had replaced past resentments and fear. Gratitude for good can have that power. It can replace an instinct for willpower to solve a problem. It allows for patience and an openness to further good. The Greek economy still has a long way to go to maintain its steady but small growth. About a third of the population lives near poverty. But Ms. Merkel’s visit marks yet another step in the thinking of Greeks as they emerge from crisis. Being thankful is a critical threshold.

Behold Greeks giving thanks

In case you have yet to send thank-you notes for holiday gifts, perhaps this rare story of public gratitude might give you a nudge. In Greece this week, government leaders gave a big thank-you to a visiting German Chancellor Angela Merkel for helping the country become free of massive bailouts and get itself back on its fiscal feet.

Just five years ago, Alexis Tsipras, the current prime minister, told Ms. Merkel during a visit to “go back” because of the financial austerity and strict reforms imposed on a Greece long used to entitlements, tax evasion, and lying about official debt.

The gratitude was more than warranted.

The size of emergency loans from foreign creditors ($331 billion) from 2010 to 2018 – especially from German taxpayers – was the largest ever to a country on the brink of bankruptcy. And Germany certainly had an interest in rescuing Greece. Collapse of the economy or a default on debt might have destroyed the euro, the single currency for much of Europe.

Yet the gratitude expressed by both Mr. Tsipras and Greek President Prokopis Pavlopoulos was more than a “debt of gratitude” or an acknowledgment of mutual dependency. Both sides spoke as if a virtuous cycle of friendship and partnership had replaced past resentments and fear.

Gratitude for good can have that power. It can replace an instinct for willpower to solve a problem. It allows for patience and an openness to further good.

“The difficulties now lie behind us,” said Tsipras, who had once opposed budget belt-tightening. “Greece is a different country that can regard the future with greater optimism.”

For her part, Merkel appreciated the new trust and frankness that helped the countries find solutions. She also paid tribute, with some empathy, to the continuing sacrifices of Greeks. “I know people went through great difficulty and had to undergo very hard and harsh reforms.”

The Greek economy still has a long way to go to maintain its steady but small growth. About a third of the population lives near poverty. But Merkel’s visit marks another step in the thinking of Greeks as they emerge from crisis. Being thankful is a critical threshold.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A ‘sweet’ sense of God’s healing power

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Joan Bernard Bradley

After a fish bone lodged in her throat, today’s contributor found that God’s help is always right at hand.

A ‘sweet’ sense of God’s healing power

The use of slang words has become so prevalent in our social media-driven society that online slang dictionaries exist to define popular terms. Since I hear the term “sweet” being used frequently in different contexts, I looked it up and found one meaning to be “pleasing to the mind or feelings.”

I like the fact that this meaning communicates a sense of joy for good experienced. For me, my most treasured experiences include healings I’ve had through the study and practice of Christian Science. So I’ve started to refer to some of my most memorable healings as “sweet.”

One of these healings took place while I was visiting my parents in the Caribbean. We were enjoying a delicious fish dinner fried “island style,” which means that smaller fish are fried whole. The bones in the fish are to be artfully removed while it is being eaten. I must have forgotten the art of eating this delicacy, because suddenly a bone lodged in my throat. Efforts to dislodge it were in vain, and I began to feel afraid.

In my distress, I reached out to God in prayer and remembered this promise from the Bible: “The word of God is quick, and powerful” (Hebrews 4:12). My dad offered to drive me to the hospital, but based on many experiences of healing I’d previously had through prayer, I realized that I didn’t have to wait for help – God’s help was right at hand. So I excused myself, went into my bedroom, and contacted a Christian Science practitioner. (A practitioner is someone whose ministry is dedicated to healing through prayer based on his or her understanding of God’s transforming love and power.)

Lovingly, and with a conviction that came from the depths of her spiritual understanding, the practitioner shared a statement from “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, that said: “God is everywhere, and nothing apart from Him is present or has power” (p. 473). This idea of God’s nature as the one infinite all-power, filling all space, buoyed and strengthened me. I then acknowledged with my whole being that because God, divine Love, is present everywhere, there is no room for anything but good. Even though that didn’t seem to be the case right then, the spiritual reality of God’s present goodness remained unchanged.

Holding steadfastly to these ideas made me feel less fearful, so I propped myself up on the bed and continued to pray. Within a few minutes, I could feel the bone moving gently down my throat – and that was the end of the problem. When I returned to the dining area with a big smile to join my parents, they rejoiced with me, and we praised God for His goodness. On more than one occasion afterward, my parents, who were not Christian Scientists, commented on this healing.

This has been a landmark healing for me, primarily because I witnessed the immediacy of God’s power to heal, but also because of how gently and peacefully the situation was resolved. It has left me with a sweet sense of God’s power as a holy, active presence. The prophet Jeremiah wrote: “Am I a God at hand, saith the Lord, and not a God afar off?... Do not I fill heaven and earth?” (Jeremiah 23:23, 24).

Through my study and practice of Christian Science, I’ve found that viewing God as infinite Spirit, ever-present good, and all of us as His image and likeness, as the Bible teaches, naturally elevates our concept of ourselves and each other beyond a material and mortal viewpoint and reveals our true identity as God’s spiritual offspring. Each of us, then, inherently reflects and expresses the spiritual qualities that Love imparts: peace, joy, holiness, gentleness, etc. These building blocks of our spiritual identity are permanent and cannot be destroyed, but they are brought to our attention more vividly through prayer. That’s why the memory of this experience is so “sweet” and why I rejoice in these beautiful words of the Bible: “My meditation of him shall be sweet: I will be glad in the Lord” (Psalms 104:34).

A message of love

As seen on TV

A look ahead

Have a good weekend and come back Monday. We’ll preview the confirmation hearing of the new US attorney-general nominee and look at why many “emerging adults” are putting off traditional markers of the grown-up world such as marriage, children, and home ownership.