- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Many senators now eye White House. Few have ever made it there.

- A China-controlled internet? Why tech giant Huawei worries the West.

- An old-school solution to identity theft: your durable ‘SSN’

- Russians embrace Soviet ideals – by not paying their gas bills

- With mud hut and chickens, an ancestral village heals generational divide

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Playing chicken with Brussels on Brexit: How will May fare?

Arthur Bright

Arthur Bright

There are now fewer than 60 days until Britain is slated to leave the European Union. But while Prime Minister Theresa May yesterday united her fractious Conservative Party behind one more attempt at negotiations with the EU, a resolution to Brexit looks no closer to reality.

Ms. May on Tuesday promised to reopen the withdrawal agreement with the EU in order to find “alternative arrangements” to the “Irish backstop” – a fallback solution for keeping the UK-Irish border open if negotiations drag out. The backstop has been bitterly opposed by the most pro-Brexit Tories, so May’s promise helped bring them into line with her Brexit proposal.

But that proposal shows little likelihood of success. Top EU officials like French President Emmanuel Macron say the withdrawal agreement – which May herself negotiated and had promised was final – is not going to be reopened. And others said Britain wasn’t being clear about its concrete goal. The British government “must now say quickly what it wants, because time is running out,” said German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas.

Though some Brexiters view the EU’s position as a bluff, Europe has shown no indication of giving ground. That leaves May’s prospects in Brussels looking grim. For while she may have kept her party from fracturing over Brexit, the possibility of a no-deal Brexit – something May says “would be a calamity” – seems no less likely.

Now for our five stories of the day.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Many senators now eye White House. Few have ever made it there.

The 2020 campaign could tie the record for sitting senators running for president. And while history points to a steep climb, many see a roadmap in President Barack Obama’s successful campaign.

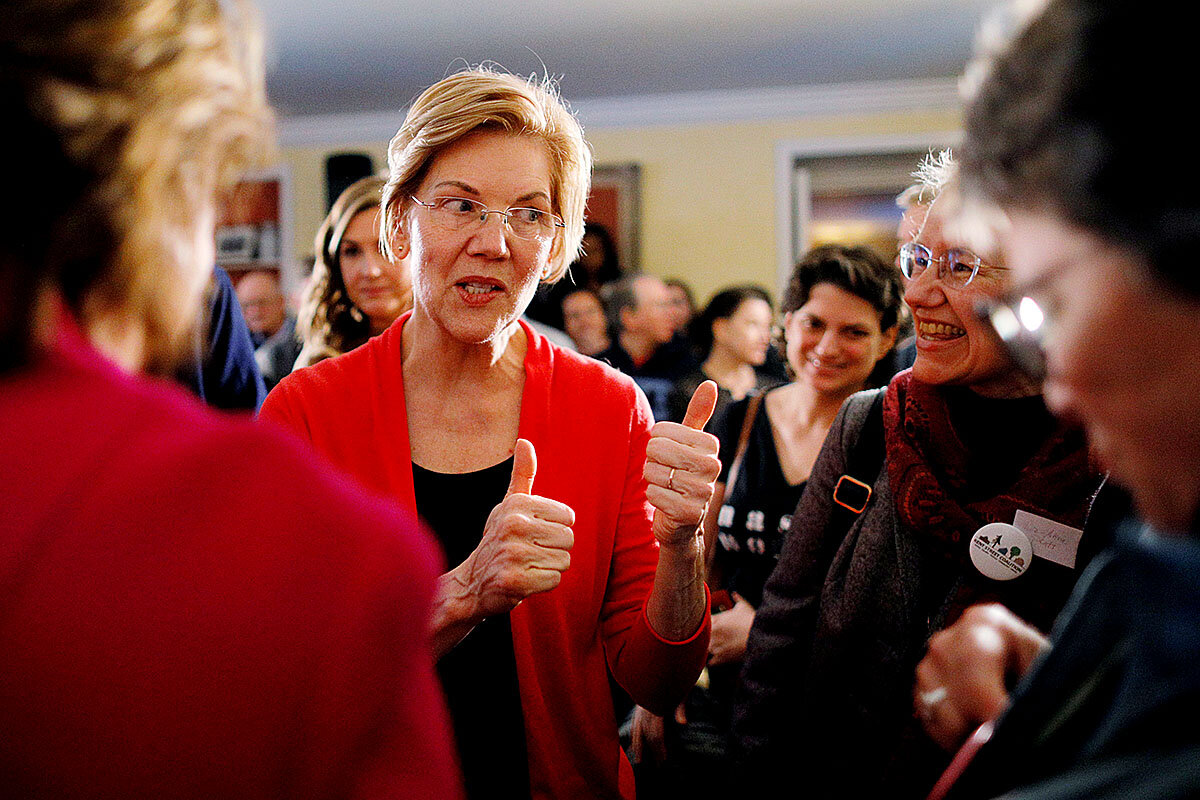

When Sen. Kamala Harris (D) of California announced her bid for the White House last week, she became the third senator to make it official in the past month, after Sens. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Kirsten Gillibrand of New York. Indeed, the 2020 cycle may wind up tying the 1976 presidential race for the record number of sitting senators to declare candidacies. History would say they face an uphill climb. Aside from Presidents Barack Obama and John F. Kennedy, the only other sitting senator to make the jump to the Oval Office was Warren G. Harding – in 1920. Today’s senators, however, have advantages their predecessors didn’t. It’s less important to be physically present in Washington than it used to be, since modern technology makes it easier for candidates and their staff to stay connected. And with a supercharged base of voters dead set on ousting the incumbent and no obvious frontrunner bigfooting the competition, the 2020 cycle is especially alluring to anyone who’s been harboring White House hopes. “They look at whoever is president, and they say, ‘I could do the job just as well,’ ” says Senate historian emeritus Don Ritchie.

Many senators now eye White House. Few have ever made it there.

When a young US senator named Barack Obama announced he was going to run for president in 2007, pundits proclaimed the odds were against him.

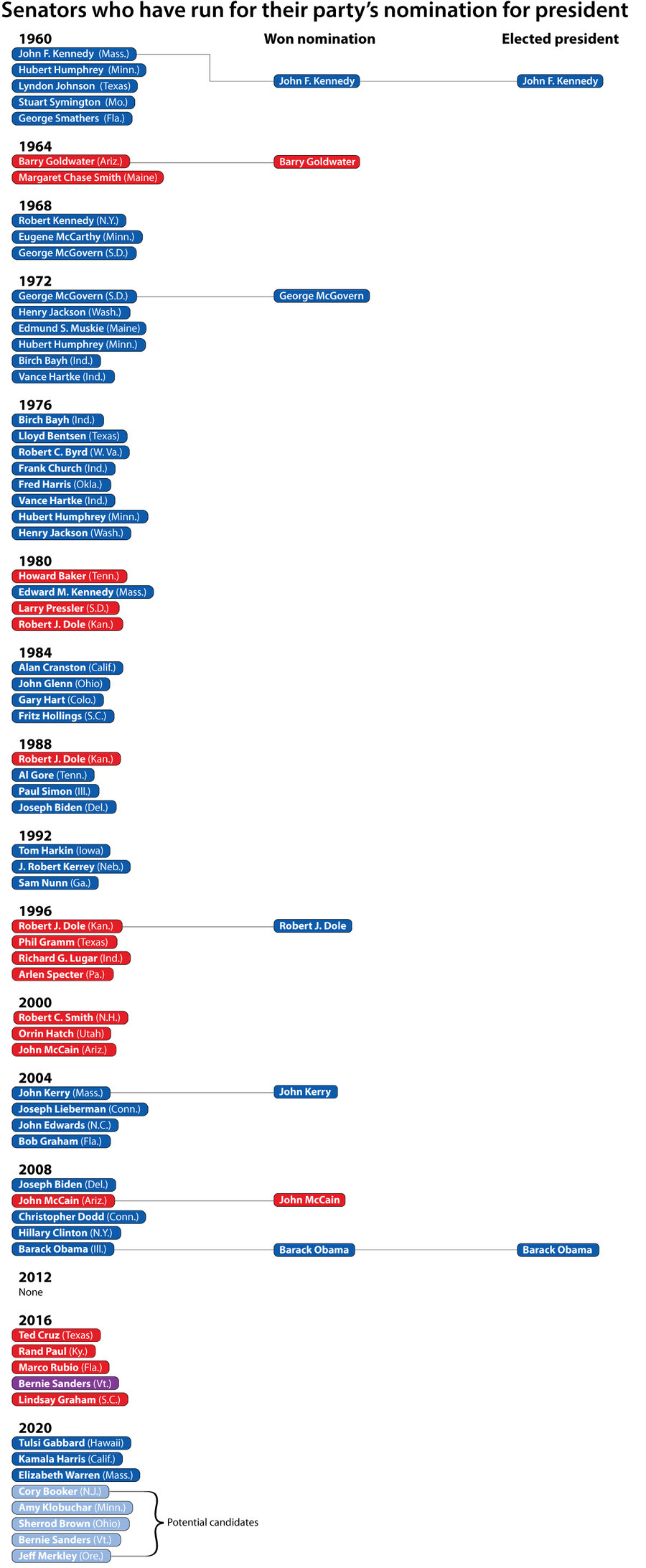

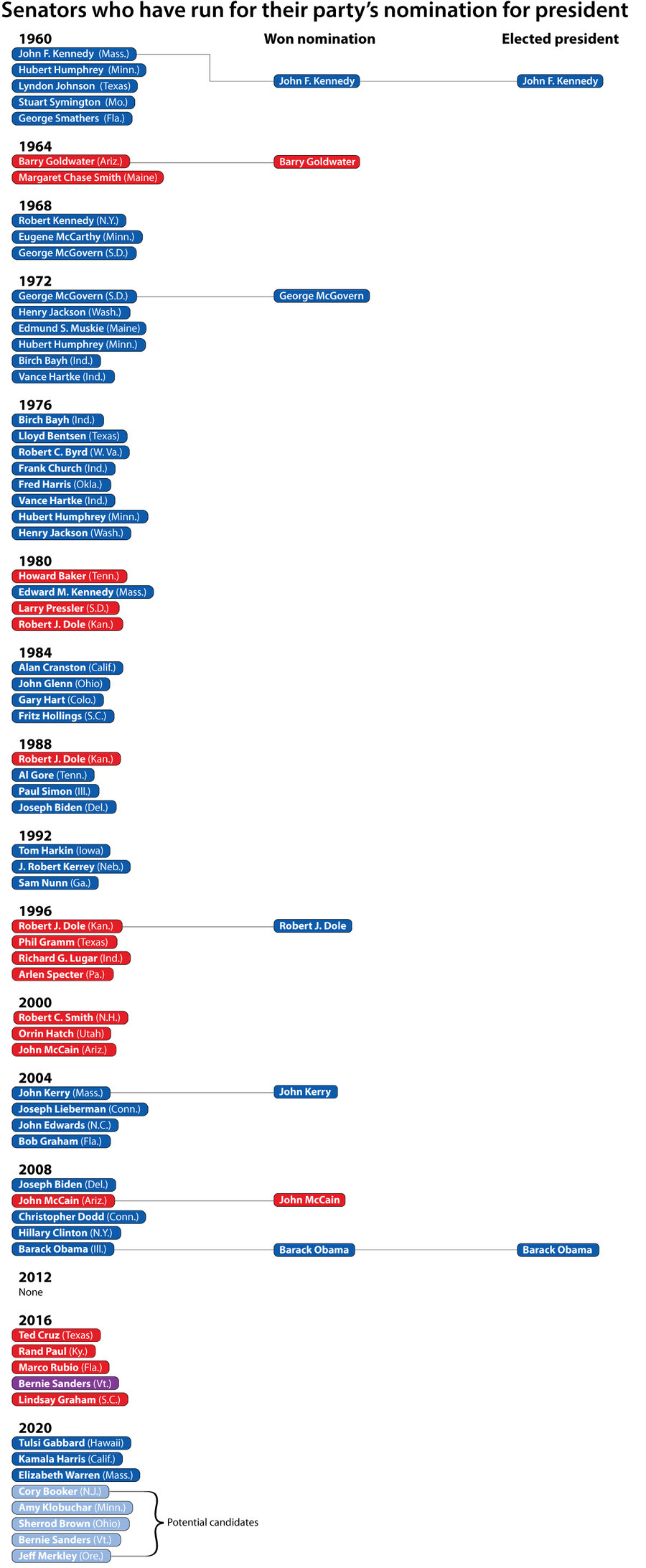

He was a Washington rookie, at the time having served only two years in the Senate, up against Democratic powerhouses like Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden for the nomination. He lacked executive experience. Plus, no sitting senator had won the White House since John F. Kennedy in 1960.

President Obama beat the odds. Now, as 2020 looms, a slew of Democrats are looking to do the same, with as many as eight senators angling toward the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue.

Sen. Kamala Harris of California announced her bid last week – the third to make it official in the past month, after Sens. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Kirsten Gillibrand of New York. Other senators poised for possible campaigns include Cory Booker of New Jersey, Bernie Sanders of Vermont, Sherrod Brown of Ohio, Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, and Jeff Merkley of Oregon.

If all of them wind up running, the 2020 slate would tie the 1976 presidential cycle for the record number of sitting senators to declare candidacies.

History would say they face an uphill climb. In ’76, despite all the senators vying for the nomination, the Democratic Party wound up tapping a governor, Jimmy Carter of Georgia. Before President Kennedy, the only sitting senator to make the jump to the Oval Office was Warren G. Harding – in 1920.

Today’s senators, however, have advantages their predecessors didn’t. It’s less important to be physically present in Washington than it used to be – and given the current state of gridlock, there’s less legislating going on anyway. Modern technology also makes it easier for candidates and their staff to stay connected while jetting around the country. While there’s often strong public antipathy toward “creatures of Washington,” Obama showed that newer senators can benefit from the stature and media attention the office brings without coming across as a party insider or having to defend a long trail of controversial votes.

Then there’s the timing. With a supercharged base of voters dead set on ousting the incumbent and no obvious frontrunner bigfooting the competition, the 2020 cycle is especially alluring to anyone who’s been harboring White House hopes. And it’s a good bet that many, if not most, senators have had moments when they’ve looked in the mirror and seen presidential material.

“They look at whoever is president, and they say, ‘I could do the job just as well,’ ” says Senate historian emeritus Don Ritchie. “Ambition is how the political system generates new talent. It drives people to do great things.”

Senate Historical Office

‘You can’t be in two places at once’

After Sen. Birch Bayh (D) of Indiana decided to run for president in the fall of 1975, scheduling quickly became a huge challenge, says Jay Berman, his then-chief of staff. Not only did the Senate meet almost every day back then, but there was also no internet, no cellphones – no easy way to stay in touch with staff on the Hill when the candidate was on the road, or mingle with potential voters when he was in Washington.

The campaign team wanted folks to feel as if the senator was still “a Hoosier, that he had not grown too big for his britches,” Mr. Berman recalls. “But you had to be someplace to make an impression.” Bayh also struggled to support his wife, Marvella, who was fighting cancer during the campaign. In the end, he couldn’t drum up enough support in Iowa and New Hampshire and withdrew his candidacy in March of 1976.

Juggling a nationwide campaign with Senate duties is still grueling, especially for those in leadership. Former Sen. Bob Dole (R) of Kansas managed to win the GOP nomination in 1996 while also serving as majority leader. But he resigned his “day job” in June of that year to focus on his race against President Bill Clinton. (Not that it did much good, as Senator Dole lost to President Clinton by 220 electoral votes.)

“You can’t be in two places at once,” says Sen. Marco Rubio (R) of Florida, one of five senators to run for president in 2016. “If you want to be a competitive candidate, you have to be out there, especially in the states that want to see retail activity.

“But you also have to be here, voting, and so at some point you make these choices,” he adds. “That’s a difficult balancing act.”

That double duty is easier these days because the Senate is usually only in session Tuesday through Thursday and votes are often scheduled ahead of time. Technology has also made it possible for candidates to constantly be present to both voters and staff (although casting votes by proxy is not allowed). And it helps that, in addition to Congress often being in a state of gridlock, Senate Democrats are in the minority; their conference is unlikely to face too many make-or-break votes in the next two years.

“I think people overstate the effect the presidential caucus is going to have on the Senate this year,” a former Democratic aide says in an email. “Not much is going to get done anyway.”

A voting record under scrutiny

The biggest snag senators often face on the road to the White House can be their Washington connection.

For longtime senators, every vote, speech, and hearing – some of which are bound to be controversial – is open to scrutiny and fodder for attack ads. Mr. Ritchie recalls how voters who would otherwise have supported Mrs. Clinton in her 2008 bid couldn’t forgive her vote to support the Iraq War when she was a senator.

“You alienate a lot of people,” Ritchie says.

Senator Gillibrand, who’s served for less than 10 years, is already facing criticism over her past position on gun control. As a House member from upstate New York, she had received an “A” rating from the pro-gun National Rifle Association, voting in 2008 to repeal portions of the firearm ban in Washington, D.C. She quickly pivoted after her appointment to the Senate.

This is when being a newer senator becomes an advantage.

Senator Harris is already having to defend her record as a prosecutor; she had been California’s attorney general when she was elected to the Senate. But she’s spent only two years on the Hill, which means she’s mostly managed to avoid votes that would turn off her base. She’s also been able to leverage her role on the Judiciary Committee to draw media attention, particularly during the high-profile hearings to confirm Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court last fall.

Obama followed a similar path. While he had been a party superstar even before he came to the Senate – from Day One people were asking if he was going to run for president – he seemed to steer clear of making waves as a legislator. Instead, he framed himself as a Washington outsider poised to change the system from inside.

“When we go to vote for a president, we want somebody new, different, fresh,” says Senate historian Betty Koed. “Those tried and true people never made it.”

Of course, one can probably be “too new” to run for president from the Senate. Had former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke unseated GOP Sen. Ted Cruz in the midterms last year, he probably could not have immediately launched a presidential campaign. Ironically, because the charismatic Texan with major fundraising chops narrowly lost to Senator Cruz, he’s now free to run for president.

The Senate can, however, be a place where failed bids turn into bright spots.

Since taking on Clinton in the 2016 Democratic primary, Senator Sanders has gone from low-key independent to one of the preeminent voices of populism on the left. Sen. Lindsey Graham (R) of South Carolina went right back to being a key player after a brief attempt to win the GOP nomination that struggled to gain traction. Even Senator Rubio, who dropped out of the 2016 primary after losing his home state to Mr. Trump by 23 percentage points, has been steadily rebuilding his brand as an influential force and a quiet counterweight to the president on issues like immigration and foreign policy.

In a brief chat with the Monitor, Rubio claims he hasn’t had much time to reflect on the experience of running for president. But he does know what he would have done differently.

“I would have won,” he says wryly. “But that didn’t work out.”

Senate Historical Office

Briefing

A China-controlled internet? Why tech giant Huawei worries the West.

The next generation of wireless networks will help power the 'internet of things,' with links to everything from home thermostats to critical national infrastructure. But who should be trusted to build it?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The US arrest warrant for a leading Chinese business executive revolves around alleged violations of American-imposed sanctions on Iran. But since the detention of Meng Wanzhou in Canada in December, the uproar surrounding her case has widened. Ms. Meng is the chief financial officer of Hauwei, a leader in wireless networking. Beijing sees Washington’s campaign against Huawei as a political ploy with protectionist purposes. But some Western governments suspect that Huawei might build hidden “back doors” into its equipment for Chinese intelligence services. FBI Director Christopher Wray warned on Monday that “we should all be concerned by the potential for any company beholden to a foreign government – especially one that doesn’t share our values – to burrow into the American telecommunications market.” Governments’ mistrust is prompted more by the nature of China’s authoritarian and opaque government than by the firm itself. The question is, Can China carve itself an influential place in the world on its own terms? Or will the rest of the world decide that even if the “China price” is attractive, the hidden costs are too high?

A China-controlled internet? Why tech giant Huawei worries the West.

Huawei, the world’s biggest producer of telecommunications equipment, has been in the headlines as the United States proceeds with a case against one of its executives. Here’s a look at the case, the company, and the global issues at stake.

Q: Who is Meng Wanzhou and why was she arrested?

Ms. Meng, who is also known as Sabrina Meng, is the daughter of the founder of Huawei, the Chinese tech giant. She is also the company’s chief financial officer.

The US Justice Department issued an arrest warrant for Meng late last year, charging her with violating US sanctions against Iran by doing business through a hidden subsidiary.

So when, last December, she flew into Vancouver, British Columbia, where she owns two luxury homes, Canadian authorities detained her under the terms of Canada’s extradition treaty with the US. She is under house arrest on $7.5 million bail, wearing an electronic ankle bracelet.

In the teeth of furious objections from Beijing, Washington formally requested Meng’s extradition on Monday. The Canadian Justice Department must decide within 30 days whether to proceed; if it does proceed, a judge will hold an extradition hearing. Meng can appeal any move to expel her to the US; legal procedures are likely to drag on for several months at least.

If she is tried in the US and found guilty, she faces a jail sentence of as many as 30 years.

Q: Why has the case attracted so much global attention?

Huawei is a flashpoint in what is arguably the biggest current threat to the global economy – a looming trade war between the US and China. The US unsealed fraud and corporate espionage indictments against Meng and Huawei on Monday, just as a top Chinese official arrived in Washington for talks to try to defuse the trade crisis.

US officials say that Huawei has close ties to the Chinese government and cannot be trusted to build securely the next set of wireless networks – fifth generation, or 5G – in the US or anywhere else. Washington has led a drive to dissuade allied nations from incorporating Huawei equipment in their 5G networks.

China believes the US is trying to block Beijing’s emergence as a top-flight technological power out of fear of competition. It sees Washington’s campaign against Huawei as a political ploy with protectionist purposes, and the case against Meng as a leverage tool in trade talks.

President Trump fed that impression when he said in December that he might intervene with the Justice Department in Meng’s case if that would help close a trade agreement with China or serve US national security interests.

China is going head-to-head with the US over Meng. “Beijing’s reaction will shape the world’s understanding of China’s national strength and will,” according to a Jan. 23 editorial in the Global Times, a Chinese Communist Party-owned daily in Beijing.

Q: What is Huawei known for?

Huawei makes reasonably priced, advanced wireless network equipment, mobile phones, and laptops, which it sells all over the world. The company is China’s international flagship, a shining symbol of its global reach and technological prowess.

Huawei was founded in 1987 by Ren Zhengfei, a former engineer in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. Mr. Ren’s background is one reason that some Western governments suspect that Huawei takes orders from the Chinese government. (Indeed, all Chinese companies take orders from their government if push comes to shove.)

This has sparked fears that Huawei might build hard-to-detect “back doors” into its equipment, giving Chinese intelligence services unparalleled access to – and possibly control over – all manner of devices worldwide that depend on wireless communications.

Huawei has repeatedly denied such suggestions, insisting that it is a private, employee-owned company that has never done anything underhanded.

But experts, including the European Union’s technology chief and the head of Britain’s counter-espionage agency, have recently voiced doubts about Huawei’s trustworthiness. FBI Director Christopher Wray warned on Monday that “we should all be concerned by the potential for any company beholden to a foreign government – especially one that doesn’t share our values – to burrow into the American telecommunications market.”

Q: How has China reacted to Meng’s arrest and the US indictments?

It's showed extreme anger and threatened “grave consequences” for Canada and the US if Meng is extradited.

As Canadian Justice officials consider the US extradition demand, they are under heavy pressure. Within days of Meng’s arrest, Chinese police had arrested three Canadian citizens. Two of them are still being held incommunicado in unknown locations.

Another Canadian, who had been sentenced in November to 15 years for drug smuggling, was hastily retried and sentenced to death this month.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry responded to the Huawei indictments by accusing Washington of trying to “kill” Chinese businesses. Hu Xijin, editor in chief of the Global Times, tweeted, “The US indictment ... is like putting legal lipstick to a pig of political suppression.”

Q: What is 5G?

The shift to 5G wireless networks is a once-in-a-decade upgrade that will make everything work much faster (think downloading a film in a few seconds) and make the “internet of things” a reality of daily life. Operators will be rolling out 5G in the US this year.

5G will be used to control and monitor everything from games on smartphones and the contents of consumers' refrigerators to nuclear power stations and other critical national infrastructure. It will be deeply embedded in society. That is why some regulators are worried about Huawei building such networks.

The US and Japan have banned Huawei from supplying government-owned wireless networks; Australia and New Zealand have forbidden their mobile operators to use Huawei gear in their 5G networks, citing national security; BT, the largest mobile operator in Britain, will not invite Huawei to bid on its core 5G equipment; and Vodafone announced last week it would “pause” purchases of Huawei's core 5G kit.

Polish police arrested a Chinese Huawei employee on espionage charges, and the Polish government has called on the EU and NATO to reconsider their members’ reliance on Huawei technology.

There is little Huawei can do to overcome Western misgivings. Governments’ mistrust and fear is prompted more by the nature of China’s authoritarian and opaque government than by the firm itself.

But as Beijing girds itself for battle on behalf of its national champion, the stakes could not be higher. Can China carve itself an influential place in the world on its own terms? Or will the rest of the world decide that even if the “China price” is attractive, the hidden costs are too high?

An old-school solution to identity theft: your durable ‘SSN’

Even if digital infrastructure is safe, the danger of identity thieves remains. One group of financial security experts wants to protect users by honing an existing tool: the Social Security number.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Lisa Rabasca Roepe Contributor

When the Social Security number was introduced in 1936, its heaviest burden was helping the Social Security Administration identify which “John Doe” to associate wage and tax data with. But over time the SSN has become a gateway to a myriad of services from credit to health care. That’s made it a prime target for identity thieves. In the wake of high-profile data breaches, some, including the Trump administration, have suggested replacing the SSN with a new, possibly biometric, identifier. Rather than create a new single authenticator that would be costly to develop and difficult to implement, a group of industry leaders is seeking to re-envision the role of the Social Security Administration in the digital age. The so-called Better Identity Coalition is proposing that government agencies such as motor vehicle departments and the SSA confirm an individual’s identity – at the individual’s request. Such a move would be a shift in the way the Social Security number is viewed: from a government tool to keep track of residents to an identifier that truly belongs to the individual.

An old-school solution to identity theft: your durable ‘SSN’

The calls started coming immediately following the 2017 Equifax data breach. Roughly half of Americans’ Social Security numbers had been compromised, and the Trump administration, congressional staff, and members of the banking and health-care industry all had one question.

“They wanted to know ‘what do we do now?’ ” says Jeremy Grant, a former senior executive adviser for the National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace during the Obama administration.

At the time, Congress was considering a series of bills related to the use of Social Security numbers, while the Trump administration was floating the idea of replacing SSNs with another form of nonnumerical identification – possibly a biometric identification or a unique fact about an individual.

Mr. Grant believed in a different and simpler answer, one that has gained attention as a possible solution. Rather than create a new single authenticator that would be costly to develop and difficult to implement – especially for vulnerable populations who often mistrust the government – Grant worked with a coalition of industry and government leaders to re-envision the question of personal identification in the digital age.

And he’s not the only who sees enduring relevance for SSNs.

“Because SSNs are unique, persistent, and ubiquitous, they are a good way to match people,” such as for a bank to tell the John Smith with good credit from the John Smith with bad credit, says Steven M. Bellovin, professor of computer science at Columbia University in New York City, who helped produce two National Academies reports on the difficulties of creating a national identity system. If SSNs were replaced, Bellovin says it would throw commerce into chaos.

The Better Identity Coalition, an industry group spearheaded by Grant, is focused on rethinking the SSN’s role for the age of hackers and massive data breaches. The group’s basic idea: The pragmatic solution will be a system that relies on multiple points of individual data rather than a single authenticator, whether it’s an SSN or some new digital or biometric token.

‘An old-fashioned idea’

It remains to be seen if Grant and his coalition will carry the day in the debate over digital identity. But they have gained an audience in Washington.

And in a sense their vision is stepping back toward the SSN’s original purpose. From its inception, the intent of the SSN was to be an identifier and to know which “John Doe” the Social Security Administration (SSA) should associate wage and tax data with. But over time public and private entities such as the state motor vehicle departments and health insurance companies have come to rely on the SSN for a different purpose: as an authenticator to verify that someone is who the person claims to be.

The problem with using an SSN as an authenticator is it assumes SSNs are a closely held secret when in truth they are no longer secure, Grant says. In fact, nearly 179 million records containing personal information were exposed in 2017 data breaches, according to the Better Identity Coalition.

“The idea that your SSN is a secret and could be kept a secret is an old-fashioned idea,” Grant says. “The last four digits [of your SNN] don’t offer security, but it can be used as an identifier.”

The Better Identity Coalition is proposing that government agencies, such as motor vehicle departments or the SSA, confirm an individual’s identity – at the individual’s request. For instance, an individual attempting to open a bank account could ask the SSA to validate whether there really is an individual with his or her name, SSN, and date of birth. The SSA would only need to respond yes or no, not provide any additional personal data, Grant says. Simultaneously, the individual could ask the department of motor vehicles to validate that a person with this name, address, date of birth, and driver’s license number exists.

Maintaining multiple avenues for identity verification by different government agencies using a distinct piece of data would help to minimize cybersecurity risks, say members of the coalition, which includes representatives ranging from the banking, medical, and computer-security industries, among others.

“Minimize” is a key word. In the coalition’s view, the realistic goal is not so much to have a flawless identifier as one that works with a high level of confidence and is hard for cheaters to exploit.

Such a system could also help consumers feel an element of autonomy in an often-daunting digital world. Consumer oversight of verifications is key, says Donna Beatty, part of the coalition and head of global product management at JP Morgan Chase.

“Consumers have to have control over the information – how they use it and which service providers will confirm which pieces of your identity,” Ms. Beatty said at recent cybersecurity policy forum in Washington sponsored by the Better Identity Coalition, the National CyberSecurity Alliance, and The FIDO (Fast Identity Online) Alliance.

An SSN for the 21st Century?

If a modernized SSN system may hold promise, some experts question how the government will implement these changes.

“There will need to be procedures in place to make sure it’s not just a one-stop shop for people who want to verify stolen information to know that they actually have a legitimate commodity in their hands,” says Jamie Court, president of the nonprofit group Consumer Watchdog in Los Angeles. “Once you authorize this type of identity verification, security experts will need to think through how it might be used for ill and what types of check and balances there need to be.”

For instance, he suggests there might need to be a limited number of accredited people who can access the information as well as a way to verify the verifier. A better option might be for the government to make it easier for the SSA to reissue an SSN when someone’s identity has been stolen, says Mr. Court, who advocates for consumer rights related to privacy and technology.

Meanwhile, advocates for the poor and homeless warn that proving identity is tricky for anyone without a permanent address or a driver’s license.

“Not everyone has a driver license, and not everyone has the ability to obtain a driver’s license or other form of ID,” says Maria Foscarinis, executive director for the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty in Washington.

There has to be a way to prove identity that isn’t dependent on someone having money to pay for a copy of their birth certificate or an address to prove their identity, she says. Birth certificates, which are needed to get an ID, are often stolen by others or confiscated by police when homeless people are living in a shelter or public place, she says.

However, most people do have an SSN, she says, and it would be helpful to be able to ask the SSA to validate that there is an individual with this name, SSN, and date of birth, particularly if that validation could be used when someone is applying for housing, a public benefit, or even a job.

“But [homeless people] would have to know this resource is available, how to gain access to it, and it would have to not cost anything,” she says.

Bringing identification online

Grant says that at the heart of what the coalition is trying to achieve is giving consumers the right to ask a government entity to help prove who they are.

Yet some privacy experts question whether making it more convenient, less expensive, and more reliable to prove someone’s identity online will have negative consequences for consumers.

If it becomes easy and straightforward to officially prove someone’s legal identity online, it might become tempting for regulators to expand the requirements for businesses collecting, using, and retaining SSNs, making it easier to track individuals online, says Seth Schoen, senior staff technologist for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a San Francisco-based nonprofit focused on defending digital privacy, free speech, and innovation.

People who might not want to be tracked online could find that they’re forced to be identified by their online purchases and online activities, he says. These changes also have the potential to impact free speech, Schoen says. In China, for instance, residents are legally required to identify themselves when they comment online, and this often restricts what people are willing to say.

The idea of giving consumers the right to ask a government entity to help prove their identity is also on government’s radar. In July, the Treasury Department released a fintech report that echoes what the Better Identity Coalition is recommending in its white paper. The Treasury report calls for enhancing public-private partnerships on digital legal identity products and services. Treasury also wants to improve consumers’ access to their financial data.

Agencies have the authority to make many of the changes being advocated by the Better Identity Coalition, Grant says.

He is hopeful the changes the coalition is proposing will ultimately help all individuals to do more online with greater privacy and convenience.

“One of the issues is that most businesses do business digitally, but we are locked into paper IDs,” he says.

Grant points to his experience applying for a home equity loan online. He filled out the online forms and, at the end of process, was told to go to the nearest bank branch to finish applying for his loan.

“Why can’t I log into the DMV site securely and ask them to validate my identity so I can get that loan?” Grant asks. “We’re not set up for citizens to ask the government to play this role.”

Russians embrace Soviet ideals – by not paying their gas bills

Frustration with present economic woes is leading many Russians to turn to the ideals of a rose-colored Soviet past. And for some, that means an unusual ethical stand: refusing to pay their utility bills.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Union SSR, a Russian “trade union” of some 15,000 members, has a somewhat unusual philosophy. While the Soviet Union is gone, the union insists its legal spirit remains alive. And the union’s members want to assert their economic and social rights as “Soviet citizens” against what they consider a dysfunctional and illegitimate new reality: the modern Russian government structure. As a practical matter, that means not paying their electricity, gas, and housing bills. “Officials of the Russian Federation substitute themselves for Soviet ones,” says Union SSR founder Sergei Dyomkin. “Yet the state they preside over is not a social state as the USSR was.” The union is a manifestation of a growing frustration with the Russian economy and a desire for a rose-colored Soviet past. And the rising cost of utilities seems to be a flashpoint issue. State gas monopoly Gazprom says that Russians owe nearly half a billion dollars in unpaid gas bills alone. Earlier this month a court in Chechnya ordered Gazprom to write off $135 million in debt owed by the population after prosecutors warned of “rising social tensions.” There are signs that other Russian regions might employ the same tactic.

Russians embrace Soviet ideals – by not paying their gas bills

There is a joke that was especially popular in the harsh years following the collapse of the USSR.

One Russian says to another, “You know, everything our old Soviet bosses told us about communism was false. But everything they told us about capitalism was true.”

That joke captures some of the ambivalence that still shapes Russians’ responses to the collapse of the USSR’s socialist state behemoth almost three decades ago and its replacement by an essentially market-driven form of state capitalism.

As in many Western countries, there is widespread disillusionment with a system that increasingly seems incapable of delivering economic prosperity, or even security, for large parts of the population. And Russia is experiencing a surprise spike in nostalgia for the USSR, in which nearly two-thirds now say they “regret” its passing, perhaps fueled by selected memories of the free education, health care, and full employment guaranteed by the Soviet welfare state.

Enter Sergei Dyomkin and his fast-growing Union SSR movement.

The former oil trader created the Union SSR “trade union” for people who want to assert their economic and social rights as “Soviet citizens” against what they consider a dysfunctional and illegitimate new reality. They don’t deny that the USSR is gone; they just insist that its legal spirit remains alive.

And of more practical import for the Russian state, the union encourages its members to demand that authorities live up to the Soviet-era rhetoric of social justice that still permeates the Russian constitution and political rhetoric. Until they do, the movement says, members should refuse to pay their electricity, gas, and housing charges until Russia’s social reality is brought back into line with the post-Soviet state’s political rhetoric.

“We cannot go on living as we used to,” Mr. Dyomkin says. “Of course the Soviet Union cannot be restored. But officials of the Russian Federation substitute themselves for Soviet ones, yet the state they preside over is not a social state as the USSR was. It has bad medical care, bad education, people are exploited for profits, and the courts do not function as they should. We want the state to obey its own laws. Officials must be the servants of the people.”

The power of unpaid bills

The rising nostalgia for a departed superpower, combined with widespread, growing economic hardship and disenchantment with existing political institutions, is potentially a powerful social force. But don’t expect Russians to erupt into their own version of France’s “yellow vest” uprising anytime soon. Polls consistently show large majorities of Russians unwilling to take their protest moods to the streets, perhaps another aspect of the Soviet legacy.

But Dyomkin insists that he is not interested in such political ends. “We aren’t going to be demonstrating in the streets, organizing meetings, or calling people to do anything,” he says. “Our goal is to raise consciousness.”

Union SSR reportedly has more than 15,000 members in 170 branches around Russia, especially in the restive Russian Far East. The group has not registered as a public organization and at least so far seems to be flying beneath the authorities’ radar screen.

But the tactic of refusing to pay one’s bills until the state delivers on its promises, which may seem quixotic to Westerners, might catch on in Russia.

Earlier this month a court in Chechnya ordered the Russian natural gas monopoly Gazprom to write off $135 million in debt owed by the population after prosecutors warned of “rising social tensions.” Gazprom is appealing that decision, but there are signs that other regions around Russia might employ the same tactic.

Members of Dyomkin’s group say they are determined. “I am not a person who is easily frightened,” says Vladimir Petrov, a retired military officer and founding member of Union SSR. “Our task is to unite people. When there are a million of us, we will be a big force, and the authorities will have to listen.”

The Soviet legacy

A variety of signals suggest that popular discontent is rising amid stagnating incomes and rising prices over the past five years. Public dissatisfaction has been made especially acute by issues like the Kremlin’s dismantling of the Soviet-era pension benefits and other liberal reforms of the old welfare system. More than half of Russians say they want the government to resign over its handling of social and economic policy.

But the rising cost of utilities, known as communal payments, seems to be a flashpoint issue. Gazprom says that Russians owe nearly half a billion dollars in unpaid gas bills alone.

“Communal tariffs grow every single year. There was not a single year after USSR collapse when it didn’t happen,” says Yekaterina Schulmann, an associate professor at the Russian Academy of National Economy and State Service [RANEPA]. “People takes loans, and the growing credit load is a problem in its own right. People need consumer loans to make both ends meet.” [Editor's note: The original version used a different transliteration of Ms. Schulmann's name.]

The element of Soviet nostalgia is one factor that makes Russian political culture, and its public manifestations, quite different from the West today, says Mikhail Chernysh, an expert with the Federal Center of Theoretical and Applied Sociology, part of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

“The policies of today’s state are turning more and more toward dismantling the old Soviet welfare system without providing adequate replacements. One thing people had in the Soviet Union was medical clinics in every community; today there are places that have no access to health care at all,” he says. “Social inequality is visibly growing. The Russian elite today enjoys all the privileges of wealth but feels no responsibility for public needs.... The Soviet state proclaimed equality as its main objective, and people remember that. The Soviet legacy is this enduring demand for social justice, for equality, for the principle that wealth should be properly earned and it should serve social ends.

“To be clear, people have a very selective memory of the Soviet Union. They don’t miss the shortages of goods, the repressions, the impossibility to travel abroad or to freely practice one’s religion. Nobody wants any of that back. But much of today’s political conversation is formed by people's yearning for a mythological Soviet Union, the socially oriented state that made a priority of popular needs,” he adds.

‘Who represents the people?’

Some accuse Dyomkin of being a political huckster who is mainly after the $15 fee each new member of his union must pay, followed by monthly dues of around $3. He denies that and insists that all the money goes to expanding the organization.

“It’s about enforcing the law. Who represents the people? Only political parties are represented in the parliament; the people didn't choose them.... Our union takes the form of a trade union,” which is a grass-roots organization of ordinary people uniting to defend their rights, he says.

Whatever the truth about Dyomkin’s motivations, the broad attention Union SSR is attracting seems to be a sign of the times.

“This union looks like a populist project aimed at a particular segment of society,” says Dmitry Oreshkin, head of the Mercator Group, an independent Moscow-based political consultancy. “They seem to promise people something, to protect their rights, but give no guarantees. I wouldn’t be surprised if, at some point, its leaders abscond....

“But, at the same time, its appearance shows that there is a social demand for such organizations. The state is not doing its job, so people look for alternatives. In future, such new organizations will be unregistered, independent, and at odds with the authorities. Maybe some will be frauds, but some of them might actually defend people’s rights,” he says. “But what seems certain is that there will be more groups like this.”

• Olga Podolskaya contributed to this report.

With mud hut and chickens, an ancestral village heals generational divide

For the children of immigrants, there’s often a detachment from older relatives as well as a physical distance from ancestral land. In Israel, a model Ethiopian village is bringing generations together.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

In the foothills of Israel’s Mount Carmel, teens and the older Ethiopians who visit this boarding school are tending to a model village they built together. Goats and chickens roam around the thatched huts and rows planted with teff – a staple grain in Ethiopia. They are also working on their generational divide. Once revered as the stable core of society in Ethiopia, the elders here in Israel have been seen as weak and dependent on a host society that was sometimes hostile to their customs and the color of their skin. Ziv Ababa teaches the history course on Ethiopian Jews at Meir Shfeya Youth Village and leads trips to Ethiopia. While meeting the Jewish community that remains there, the students get a deeper understanding of what was often a traumatic journey to Israel, particularly for those who traveled in the early 1980s through Sudan. “It gives our Ethiopian students a feeling of belonging and connection and confidence in themselves that they have a proud history of over 2,000 years,” says Mr. Ababa. “And in this, too, we hope they will feel more connected to their parents.”

With mud hut and chickens, an ancestral village heals generational divide

The teenagers scramble up a terraced hillside of their own creation, excited to show off one of the thatched round huts at the top that they also helped build.

In Ethiopia, it’s called a tukul, its cream-colored walls fashioned from straw and mud.

“This is our Ethiopian village,” says Yavletel Endergay, a high school senior, sweeping his hand over the view below: rows of corn, lettuce, coffee, sugar cane, and teff – a staple grain in Ethiopia. Nearby roam goats and chickens.

The young Mr. Endergay and his fellow Ethiopian-Israeli students planted the crops working side by side with older Ethiopian men and women who come every week to their school to tend this model village they built together in the foothills of Israel’s Mount Carmel.

The physical work, storytelling, and indigenous knowledge being passed down as the generations work together is an effort to address a crisis that has left the community’s youth estranged from their dislocated parents and grandparents, who came of age in a culture vastly different from the rough and tumble one they found waiting for them in Israel.

Endergay explains that it was in remote rural villages like this that his family and his friends’ families lived for generations in Ethiopia before immigrating to Israel.

The patch of land surrounding the tukul, he says, was cultivated cooperatively by relatives. That information about their communal farming way of life was new to Endergay, as was so much that has been taught to him by his elders.

“I was two when I came to Israel, and I don’t remember anything about Ethiopia,” says Endergay, one of some 135,000 Ethiopian Jewish immigrants and their descendants living in Israel. “It makes me want to go back there and learn as much as possible about what was,” he says.

The origins of these African Jews are debated, but one theory is that they are descendants of King Solomon or the lost tribe of Dan. The Ethiopian Jewish community, known as Beta Israel, arrived in Israel in waves, beginning with small numbers as far back as the 1930s, but most substantially in the 1980s and ’90s. Most recently, immigrants have come from the Falash Mura community. They say they are descendants of Ethiopian Jews who converted to Christianity generations ago, but now they want to return to Judaism.

Intergenerational divides among immigrants are common, but among Ethiopian Israelis the break has been especially severe. In part it’s born of the older generation’s culture shock and struggle to acclimate in a modern, urban setting. But community members say the younger generation’s loss of respect for their elders is more profound: Once revered as the stable core of their society, the elders were seen as having become weak and dependent on a host society that was foreign and sometimes even hostile to their customs and the color of their skin.

For young Ethiopian Israelis, a feeling of otherness and even racism are indeed issues. A recent fatal police shooting of a knife-wielding Ethiopian Israeli has reignited community allegations of racism and police abuse, and Wednesday hundreds protested on a highway outside Tel Aviv, bringing rush hour traffic to a standstill.

‘Roots’ trips to Ethiopia

The educators at Meir Shfeya Youth Village – a boarding school for at-risk and immigrant youth supported by Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America – who came up with the idea of the model village have also started offering a class on the history of Ethiopian Jews, the only course of its kind currently being taught in the Israeli school system. They have also led student “roots” trips to Ethiopia.

“This gives them a connection … to see where their parents came from,” says Ziv Ababa, a teacher at the school who has, along with the principal, spearheaded the Ethiopian generations bridge-building efforts. “It’s important because there is a total disconnect. They don’t know their history, and they go and see what it was like there, what their parents went through there to come here, and it helps connect them more closely to each other.”

The poverty many Ethiopian families experience in Israel exacerbates the shame and feelings of dislocation for both young and old. “What’s been created is a generation of kids born here without anything who see their parents as people neither in a position of leading or giving,” says Yuvi Tashome, an activist who immigrated as a child. She directs an organization called “Friends by Nature,” which works to empower Ethiopian-Israeli communities.

Ethiopian Israeli children, she argues, are raised more by Israeli institutions than by their parents, including boarding schools and after-school programs, and that the message the children receive is that their parents are not capable.

Mr. Ababa, who also designed and teaches the history course on Ethiopian Jews, came to Israel when he was 10, and on the trip to Ethiopia he takes students to his home village and arranges meetings for students who still have relatives there. While touring and meeting the Jewish community that remains, the students also get a deeper understanding of what was a traumatic journey to get to Israel, particularly for those who traveled in the early 1980s through Sudan. Thousands died along the way.

Ababa says of the class he teaches: “It gives our Ethiopian students a feeling of belonging and connection and confidence in themselves that they have a proud history of over 2,000 years, and shows that they too have a tradition and values. And in this, too, we hope they will feel more connected to their parents.”

Revelation in Gondar

Students are also charged with interviewing their parents to better understand them as people and the hardships they have endured. At the model village with the elders, the students are even taught how to conduct the traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremony, a central part of the cultural life of Ethiopian families, so they can conduct it at home with their parents – another path toward reconnection.

Zemini Aiano went on the trip to Ethiopia last year and describes it as a revelation. So many basic details of her parents’ life in Ethiopia had been a mystery to her. When she returned and showed them photos of a river in the province of Gondar where they grew up – and where the majority of Ethiopian Jews originate – her father recognized the scene as the stretch of the river that flowed right by his home village.

“I was right near where family once lived, and I didn’t even realize it,” she says.

“Before I had felt so frustrated by our differences – what I was going through, and how I felt more connected to Israeli society and speak a language [Hebrew] they have trouble expressing themselves in,” she says of her relationship with her parents.

She knows only basic Amharic – “I cannot speak from my heart in Amharic” – and her 11-year-old brother does not speak it at all.

“I feel more connected to my roots now – and I’m very proud of my parents,” says Ms. Aiano. She mentions that she goes by her Amharic first name, a growing trend among younger Ethiopians. For years most went by Hebrew names given by immigration officials.

She says she likes the meaning of her name, Zemini: one who arrived on time.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Super Bowl’s halftime controversy

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The Super Bowl’s halftime show has a history as starry as the game itself. Performers have included a who’s who of pop music, from Bruce Springsteen to Beyoncé. This year’s headliner, Maroon 5, is no slouch. But other artists – including Cardi B, Rihanna, and Jay-Z – apparently turned down the opportunity to instead show support for Colin Kaepernick, former quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers. Mr. Kaepernick became the eye of a public storm during the 2016 season when he knelt during the playing of the national anthem to express concern over racial injustice. Others saw the act as showing disrespect. A cultural debate ensued. Gladys Knight has agreed to sing the national anthem this year. “I understand that Mr. Kaepernick is protesting ... police violence and injustice,” she told Variety. But “I pray that this National Anthem will bring us all together in a way never before witnessed….” The show (and the game) will go on. Performers will respect important issues while not seeing a need to politicize an entertainment event. The civility of the debate will help ensure civil rights.

Super Bowl’s halftime controversy

The eight most-watched television broadcasts in US history were Super Bowl games. Though viewership has slipped in recent years, the 2018 game still gathered 103.4 million people in front of their screens. It was the top-rated TV event of the year.

The game’s glitzy halftime show has its own starry history. Over a half-century, performers have included a who’s who of pop music, from Bruce Springsteen, Diana Ross, and Prince, to Justin Timberlake, Lady Gaga, and Beyoncé.

This year’s headliner, Maroon 5, can boast of three Grammy awards and millions of album sales, but it’s hardly the hot act of the moment. Cardi B, Rihanna, Jay-Z, and others apparently turned down the opportunity to star in the year’s biggest showcase to instead show support for Colin Kaepernick, former quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers. .

Mr. Kaepernick, an African-American, became the eye of a public storm during the 2016 season when he knelt during the playing of the national anthem before NFL games to express his concern over incidents of racial injustice. But others saw the act as showing disrespect for the anthem and US flag. A cultural debate ensued. Today Kaepernick is no longer employed by an NFL team. That has led some to argue team owners won’t hire him because of his public political expression while working in an NFL event.

An online petition asking Maroon 5 not to perform has received more than 110,000 signatures. But PJ Morton, the lone African-American member of Maroon 5, has defended the group’s appearance.

“We can support being against police brutality against black and brown people and be in support of being able to peacefully protest and still do our jobs,” Mr. Morton has said. “We just want to have a good time and entertain people while understanding the important issues that are at hand.”

Another African-American, the “Empress of Soul” Gladys Knight, has agreed to sing the national anthem at the game.

“I understand that Mr. Kaepernick is protesting ... police violence and injustice,” she told Variety in a written statement. But “[i]t is unfortunate that our National Anthem has been dragged into this debate.... I pray that this National Anthem will bring us all together in a way never before witnessed and we can move forward and untangle these truths which mean so much to all of us.”

Perhaps in an effort to quiet the controversy, Maroon 5 did not give a traditional press conference this week. Instead, it announced it would join with the NFL and Interscope Records to make a $500,000 donation to Big Brothers Big Sisters of America. Travis Scott, an African-American rapper who will join Maroon 5 on stage at halftime, earlier pledged to donate in partnership with the NFL $500,000 to Dream Corps, a nonprofit social justice group with several initiatives, including prison reform.

One thing is certain in 2019: The show (and the football game) will go on. Those protesting or boycotting will make their point that racial issues still need attention. The participating performers will respect the issues Kaepernick raises while not seeing a need to politicize a sports and entertainment event. And the necessary national conversation about the best ways to draw attention to and correct social wrongs will go on. The civility of the debate will help ensure civil rights.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Our true identity can’t be stolen

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Valerie Minard

When fraudulent charges appeared on her credit-card bill, today’s contributor was skeptical that the situation would be resolved. But considering a spiritual view of identity as safeguarded by God brought a more productive outlook, and resolution ensued.

Our true identity can’t be stolen

While the internet provides a tremendous resource of knowledge and convenience, it also exposes personal information in ways we could never have imagined. Safeguards that once seemed pretty much invulnerable are no longer foolproof. So how do we protect ourselves?

Some time ago I had an experience with identity fraud. When a new credit-card bill arrived, I noticed there were about $1,000 in purchases and withdrawals from ATMs in another country that neither my husband nor I had made. The credit-card company helped us submit a fraud report to investigate the matter but advised that we might be responsible for paying the bill.

This was not encouraging news, and fear started to creep in. I felt violated that someone had taken my personal information and stolen money from me. I was also skeptical that the credit-card company would follow through and get the proper evidence needed for a waiver of the charges. It seemed unfair that we might have to pay for someone else’s dishonesty.

But I saw that this was unhelpful, dead-end thinking. I knew from experience that what would be most helpful was to stop focusing so much on the resentment and instead ask, What is God knowing about all this?

Well, first off, I had learned in my study and practice of Christian Science that God is good. That He is the Giver of all good. Nothing God gives us can ever be taken away. As our creator, God also safeguards our true identity as His spiritual offspring. Therefore, I realized, nothing about this God-derived identity can be stolen or misused.

I prayed to extend this view to others involved, too – for instance, to see that the people at the credit-card company were also God’s children, the spiritual expressions of divine Truth, created to be trustworthy. My skepticism about their efforts shifted to gratitude that they were willing to investigate the matter. I felt grateful for the case worker who was patient enough to explain the whole investigative procedure to me, and for the detectives who were checking out the ATMs and stores where purchases had been made.

I was encouraged by a passage in the Bible that says, “There is nothing covered, that shall not be revealed; neither hid, that shall not be known” (Luke 12:2). Besides the literal way in which I hoped this would be proved true by recouping the funds, this also suggests to me that one’s ability to express qualities such as honesty and integrity can never truly be lost, because it stems from our true, spiritual identity. Similarly, one’s God-given purity and wholeness can never be stolen, even if it seems we’ve been defrauded.

A couple of weeks later, I was delighted to learn that the perpetrators had been apprehended. I was surprised to notice that not only was our credit-card balance credited for the fraudulent charges, but an extra $1,000 had been credited by mistake.

Now it was my turn to express honesty and integrity! When I notified the credit-card company of the error, they realized that a bug in their software system resulted in twice the payback. No one had ever brought this to their attention before. Not only had the wrong done to me been corrected, but now the credit-card company and the businesses they dealt with could fix a significant problem; they were helped as well.

God does uphold and safeguard our identity, which can never be stolen, defiled, or taken away. Recognizing this spiritual reality equips us to see more evidence of it in our lives.

Adapted from a Nov. 7, 2011, article now located on JSH-Online.com.

A message of love

Limiting exposure

A look ahead

Thank you for accompanying our exploration of the world today. Please come back tomorrow, when we will look at how communities across the Midwest are trying to shield their most vulnerable members, the homeless, from the arctic temperatures gripping the region.