- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Covering Mueller: a view from the keyboard

At 11:03 a.m. yesterday I received a ping on our internal email system from Liz Marlantes, our Washington editor.

“Report just went live,” it said. The Justice Department had pushed the button and posted on its website special counsel Robert Mueller’s report (with some redactions).

What followed were five and a half hours of teamwork that produced Thursday’s lead Monitor story.

My job as a lead writer was to read the actual report and control the keyboard. Staff writer Jessica Mendoza made calls for expert comment. Longtime congressional correspondent Francine Kiefer worked sources to get the Capitol Hill response. It’s a drill I’ve been involved in dozens, maybe hundreds of times over the years.

There are tricks to reading 400 pages of material quickly. My advice: Skip the executive summaries. Navigate using the table of contents, and keep an eye out for key details like Hope Hicks’ 3 a.m. phone call from a Russian on election night insisting on a “Putin call.”

I was surprised to read that President Donald Trump was asking staffers to find Hillary Clinton’s stolen emails. Also, Mr. Trump told Michael Cohen a presidential campaign would be a great “infomercial” for his real estate. The bits where Trump staffers refused his demands to fire Mr. Mueller were amazing.

Putting all this together is like jumping out of a plane unsure if your parachute will open. Jess and Francine produced great stuff fast, which helped a lot. Still, I didn’t file the last take until 25 minutes before our 6:15 publication time. The chute opened just before I hit the ground.

Now to our five stories for the day, which include an exploration of how members of Congress are balancing the implications of the Mueller report with the political calculus of an upcoming election, and a counternarrative challenging the notion that a cleaner energy future must come at workers’ expense.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

After Mueller report, the pressure shifts to Congress

The focus now moves from the criminal realm to the political. And despite the special counsel’s ambiguous conclusions as to whether the president obstructed justice, Democratic leaders remain wary about impeachment.

Special counsel Robert Mueller’s report declined to either charge or exonerate the president on obstruction of justice. As a result, some say, Congress is now responsible for that determination – a situation that has set off an internal debate among Democrats over how exactly to proceed.

The report’s many unflattering details about President Donald Trump have led to renewed calls for impeachment from the party’s liberal base. But House Democratic leaders appear wary of engaging in an exercise that would almost certainly not result in Mr. Trump’s removal from office and could provoke a political backlash. For now they are focused on investigating. House Judiciary Chairman Jerrold Nadler, D-N.Y., has asked Mr. Mueller to testify next month and on Friday issued a subpoena for a nonredacted version of the report.

“It’s really up to Congress … to investigate the question of whether President Trump committed obstruction of justice,” says Ken Hughes, a presidential expert at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.

“That’s their duty,” agrees John Yoo, a former Department of Justice official under President George W. Bush. “If they don’t want to do it, that’s a judgment itself.”

After Mueller report, the pressure shifts to Congress

One day after the release of special counsel Robert Mueller’s much-anticipated report, the focus is shifting to Capitol Hill, with many observers suggesting it’s now Congress’s duty to pick up where the special counsel left off.

“It’s really up to Congress” – and not a special counsel, who works for the executive branch – “to investigate the question of whether President Trump committed obstruction of justice,” says Ken Hughes, an expert on presidential abuse of power at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center in Charlottesville, Virginia, “just as it investigated whether Nixon committed it and whether Clinton committed it.”

“That’s their duty,” agrees John Yoo, a former Department of Justice deputy assistant attorney general under President George W. Bush. “If they don’t want to do it, that’s a judgment itself.”

Mr. Mueller’s report made clear a number of things: Russia tried to influence the 2016 elections in favor of Donald Trump. Mr. Trump and his campaign knew it and benefited from it. At the same time, the evidence reviewed by the special counsel did not establish a criminal conspiracy or coordination between the two.

“He’s closed the book on that chapter,” says Mr. Yoo, now a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

Yet the report also seemed to raise as many questions as it answered. Most prominently, Mr. Mueller left open the matter of obstruction of justice, pointedly refusing either to charge or exonerate the president.

Attorney General William Barr took Mr. Mueller’s wording to mean that there was not enough evidence to prove the president obstructed justice –end of story. Others, however, read the report as shifting the responsibility for making that determination from the realm of criminal prosecution to that of political oversight.

“Congress should take the next steps,” says Lisa Gilbert, vice president of legislative affairs at Public Citizen, a Washington-based government watchdog.” The subpoena and other mechanisms in their toolkit should be used to the greatest extent of their ability.”

In other words, Mr. Mueller put the ball in Congress’ court, for better or worse. And that has set off an internal debate among Democrats over how exactly to proceed.

The ‘Mueller fatigue’ factor

Already the report’s ambiguous conclusions and many unflattering details about the president are leading to renewed calls for impeachment from the party’s liberal base.

But House Democratic leaders appear wary of engaging in an exercise that would almost certainly not result in Mr. Trump’s removal from office, given his strong support from Republicans, who hold the majority in the Senate. They worry it could provoke a political backlash after two long years of investigation, with many voters possibly experiencing “Mueller fatigue.”

Some argue the party would be better off keeping the focus on kitchen-table issues, like health care, that worked to its advantage in 2018.

“Going forward on impeachment is not worthwhile at this point,” Maryland Rep. Steny Hoyer, the No. 2 Democrat in the House, told reporters shortly after the report’s release on Thursday. “Very frankly, there is an election in 18 months, and the American people will make a judgment.”

But later – after his remarks drew a torrent of criticism from the left – Mr. Hoyer clarified in a tweet that “all options ought to remain on the table,” saying “Congress must have the full report & all underlying evidence in order to determine what actions may be necessary.”

Republicans have generally sided with Mr. Barr, saying the report should mark the end of Democrats’ pursuit of Mr. Trump.

“If we’ve learned anything over the past two and half years of RussiaGate, it’s that Democrats will not accept any result short of removing the president from office,” writes Joe diGenova, a former U.S. attorney and conservative legal analyst for Fox News. “No amount of legal exoneration will stop the political witch hunt.”

“It’s time to move on,” House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., asserted.

Cost-benefit analysis

Many Democrats, meanwhile, see the report as a kind of roadmap for Congress. Rep. Jerrold Nadler, D-N.Y., chair of the House Judiciary Committee, said as much in a press briefing Thursday. His committee has already asked Mr. Mueller to testify on May 23 and has authorized subpoenas for five White House officials mentioned in the report.

On Friday Mr. Nadler issued a subpoena for a full, nonredacted version of the report, though the Justice Department has said that it will provide leaders of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees a less-redacted copy in coming days.

Still, some observers say even extending the investigations might be politically risky, particularly if Democrats fail to turn up anything more conclusive.

“[Even] if they call Mueller in to testify, I’m not sure what he could say that would be new or helpful,” says Bennett Gershman, a law professor at Pace Law School in New York City.

Perhaps better, he says, to wait on the state and federal investigations looking into Mr. Trump’s finances and The Trump Organization’s business dealings. In his report, Mr. Mueller mentioned referring 14 potential crimes – 12 of which have not been made public – to other offices, saying they were beyond his jurisdiction.

Until this point, Democratic leaders have managed to keep calls for impeachment from the party’s left wing at bay. But the pressure is starting to mount.

On Thursday, influential freshman Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., threw her support behind the impeachment resolution that Rep. Rashida Tlaib of Michigan introduced last month. Rep. Al Green, D-Texas, renewed his own repeated calls to remove the president.

On his progressive podcast Pod Save America, former Obama speechwriter Jon Favreau said the fact that a Republican Senate would be unlikely to convict the president on impeachment charges should not prevent Democrats in the House from doing everything they can to publicly hold the president to account.

“Let’s, I don’t know, provide the American people with all the evidence, all the testimony, all the underlying documents, all the witnesses – everything they need to make a determination about whether the president is fit for office or not,” he said.

Why frustrated Ukrainians may elect a comedian as president

Whom do voters turn to when elected leaders disappoint? Ukraine President Petro Poroshenko looks set to be trounced in elections Sunday, but not because of approval for his opponent, a TV comedian.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Ukrainians seem ready to overwhelmingly elect a political novice, a comedian whose main claim to fame is that he played a president on TV, to the country's real top office when they cast ballots Sunday. According to the latest survey, 72% of decided voters plan to vote for Volodymyr Zelenskiy, with just 25% choosing the incumbent, Petro Poroshenko.

Mr. Zelenskiy is clearly riding the tidal waves of negative feelings toward Mr. Poroshenko that have been building for some time. The president was handily elected five years ago in an emergency race following the Maidan Revolution. But he has since presided over the slow demise of most of the hopes for peace, economic renewal, and an end to corruption and oligarchic rule that he once campaigned on.

“Poroshenko lost this election at least a year ago,” says Ruslan Bortnik, director of a Kiev think tank. “The most burning issues of today are corruption and poverty. Not a single corrupt official has been punished during Poroshenko’s five years, and half the population can’t cope with the rising costs of utilities. ... It seems like many Ukrainians would rather vote for a telephone pole than for Poroshenko.”

Why frustrated Ukrainians may elect a comedian as president

It may be one of the most spectacular political miscalculations of all time.

Election billboards across Ukraine feature a stern-jawed incumbent President Petro Poroshenko facing off with his main opponent in second-round voting for the presidency this Sunday. However, the person he is angrily staring down is not his very real Ukrainian rival, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, but Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Those billboards may stand as a stark symbol of why Mr. Poroshenko’s campaign for reelection appears to have hit a wall.

Ukrainians seem ready to overwhelmingly elect a political novice, a comedian whose main claim to fame is that he played a president on TV, when they cast ballots this Sunday. According to the latest survey, carried out by the Kiev International Institute of Sociology (KIIS), 72% of decided voters plan to vote for Mr. Zelenskiy, with just 25% choosing Mr. Poroshenko. The election’s first round on March 31 was contested by 39 candidates, and Mr. Zelenskiy topped the polls with 30%, followed by Mr. Poroshenko with 17%.

Many in Ukraine’s stunned establishment are reportedly scrambling to build bridges with the newcomer, who largely remains a black box regarding his political, economic, and social policies. A Russian-speaker from eastern Ukraine who barely speaks Ukrainian, Mr. Zelenskiy is clearly riding the tidal waves of negative feelings toward Mr. Poroshenko that have been building for some time. The incumbent president, handily elected five years ago in an emergency election following the Maidan Revolution, has presided over the slow demise of most of the hopes for peace, economic renewal, and an end to corruption and curbing oligarchic rule that he once campaigned on.

“Poroshenko lost this election at least a year ago, when his negative rating reached 50%,” says Ruslan Bortnik, director of the Ukrainian Institute of Analysis and International Relations, an independent Kiev think tank. “The most burning issues of today are corruption and poverty. Not a single corrupt official has been punished during Poroshenko’s five years, and half the population can’t cope with the rising costs of utilities. ... It seems like many Ukrainians would rather vote for a telephone pole than for Poroshenko.”

Frustration with Poroshenko

In an effort to reverse his sagging fortunes, Mr. Poroshenko hit upon patriotic themes to rouse the population against the external enemy, Russia. Hence the billboards. But that now appears to have been a bad miscalculation.

“Poroshenko’s mistake was to champion anti-Russian positions and rhetoric, which served to distract people from domestic Ukrainian problems,” says Alexander Okhrimenko, president of the Kiev-based independent Ukrainian Analytical Center. “It worked up to a point, but over the past five years Ukrainians have gotten tired of it.”

Mr. Poroshenko’s election slogan, “Army! Language! Faith!,” was designed to highlight his achievements in promoting Ukrainian nationalism in the face of Russian expansionism. He did indeed rebuild Ukraine’s once decrepit army into a capable fighting force, held the line against Russian-backed rebels in the east, and stood up to Moscow when it seized Ukrainian warships and sailors in a murky incident in the Kerch Strait between Russia and Russian-annexed Crimea last year.

But his efforts to promote the Ukrainian language have mostly generated friction in a country where both languages have always coexisted peacefully. And his crowning achievement, obtaining autocephaly, or independence, for a Ukraine-based Orthodox Church, appears to be sowing mainly division so far.

“Poroshenko and his team have warned so many times about Russian aggression, even giving dates when the Russian army was supposed to invade Ukraine,” says Mr. Okhrimenko. “People just stopped taking it seriously. Poroshenko put his stake on Ukrainian nationalism, but real nationalists are only about 10 percent of the population. The majority of Ukrainians do not perceive Russia as an enemy.”

Indeed, a public opinion survey conducted earlier this year by KIIS and the independent Russian pollster Levada found that attitudes are improving in both countries, despite all the acrimony, mutual sanctions, and conflict of the past five years. The survey found that 77% of Ukrainians hold “positive” attitudes toward Russians personally, and a clear majority, 57%, reported their view of Russia itself as “positive” – up from 30% four years ago. That doesn’t mean that Ukrainians are pro-Putin: 69% said their attitude to the Kremlin leader was “bad” or “very bad.”

Despite years of mutual sanctions, Russia remains Ukraine’s biggest single trading partner, and trade has actually been on the upswing lately.

Mr. Poroshenko’s efforts to rapidly “decommunize” Ukraine also raised hackles in Russian-speaking eastern Ukraine, where people were suddenly ordered to stop displaying Soviet-era symbols on occasions like Victory Day even though in those regions most people’s ancestors served in the Red Army during World War II. Government attempts to promote wartime Ukrainian “fighters for Ukrainian independence” – despite records of many such fighters collaborating with the Nazis and participating in the Holocaust – may have further alienated many Ukrainians.

“Attempts to force only one language, to rewrite history, to attack holidays like Victory Day, made a lot of reasonable voters turn away from Poroshenko,” says Mr. Bortnik. “He stirred up conflicts with neighbors like Poland and Hungary, and even some of our Western partners started to get fatigued with Ukraine.”

A hard road for Zelenskiy

Despite the fears of some Western observers that Mr. Zelenskiy is “dangerously pro-Russian,” it seems most unlikely that, if elected, he will significantly alter Ukraine’s long-term reorientation away from Moscow and toward the West. Indeed, there was an actual pro-Russian candidate in the election’s first round, Yuriy Boiko, who astounded many by finishing in fourth place with 12% of the overall vote. In some places, such as the Ukrainian-controlled parts of the Donbas and Odessa, Mr. Boiko actually topped the polls.

Mr. Zelenskiy has said he will seek dialogue with Russia and that “winning peace for Ukraine” is at the top of his priority list. Experts say that is not likely to include making territorial compromises. Beyond that, little is known of his specific intentions.

“Peace is number one. People are tired of war. They want to turn over a new page,” says Vadim Karasyov, director of the independent Institute of Global Strategies in Kiev. “Zelenskiy represents a new Ukraine. He wants Ukraine to be a normal East European country, not to be under control of the Kremlin or Europe or the U.S. – a Ukraine that is not the subject of geopolitical competition. People want an end to all this tension and hatred. That is what the huge support for Zelenskiy represents.”

If elected, he will face massive obstacles. He does not have a party, and unless he quickly assembles support in the Supreme Rada (Ukraine’s parliament), he may find himself stymied at least until parliamentary elections roll around in October.

“After the elections, Zelenskiy’s situation will be colossally difficult,” says Sergey Gaiday, head of the Gaiday.com political consultancy. “If he can’t curb corruption, there will be many trials ahead for him. The key issue here is not just to get rid of Poroshenko, but to pass from oligarchic rule to people’s power. The election campaign will seem easy compared to what Zelenskiy will face afterward.”

A deeper look

North Macedonia’s election: a victory for Western diplomacy?

An election in North Macedonia may not seem momentous. But Sunday’s vote is a testimony of the country’s journey from near civil war to EU candidate – and of how successful Western support for democratic change can be.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Back in 2001, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, as it was then known, seemed just around the corner from full-blown civil war. Today it has recently ended a 27-year-long dispute with Greece over its name that was blocking its way to NATO and European Union membership and will democratically elect a new president this Sunday.

North Macedonia is unique in a part of the world where nationalist strongmen, religious extremists, and organized criminals are amassing ever greater influence. It is not only swearing allegiance to the West; it is doing (almost) everything it needs to do to join the club.

Crucially, the United States and the EU got involved 18 years ago. And for much of the past two decades, they have played an active role in the country’s affairs. At key moments “the EU and U.S. had common goals … and spoke with one voice,” says a senior Western diplomat here. “That had an effect.”

“We are the most successful story in the region,” says Deputy Prime Minister Bujar Osmani. “We’re a multicultural, multiethnic, multireligious country with no open disputes among ourselves or with our neighbors. We have become a role model.”

North Macedonia’s election: a victory for Western diplomacy?

When I last visited this tiny Balkan nation in 2001, it was teetering on the cliff edge of ethnic civil war, threatening to drag its neighbors back into renewed bloodshed.

I recall sitting in a provincial town hall, my conversation with the mayor drowned out by the clatter of a helicopter gunship outside the window as it fired rockets at nearby rebel positions.

But the country stepped back from the brink. And on Sunday, after a long and tortuous journey, the country will hold presidential elections that the government hopes will finally unlock the Holy Grail: membership in NATO and the start of talks to join the European Union.

The newborn Republic of North Macedonia is unique in a part of the world where nationalist strongmen, religious extremists, and organized criminals are amassing ever greater influence. It is not only swearing allegiance to the West; it is doing (almost) everything it needs to do to join the club.

“We are the most successful story in the region,” says Bujar Osmani, deputy prime minister for European affairs. “We’re a multicultural, multiethnic, multireligious country with no open disputes among ourselves or with our neighbors. We have become a role model.”

Less partisan observers point to flaws in North Macedonia’s democratic credentials, but there is no doubt that “everyone perceives Macedonia as a positive story,” agrees Uranija Pirovska, head of the local Helsinki Committee, a human rights watchdog.

How did that happen?

An important corner of Europe

Back in 2001, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, as it was then known, had been independent for a decade. Its southern neighbor, Greece, did not recognize its “Macedonia” name; Bulgaria, to the east, did not recognize its language as “Macedonian.” But at least the country had avoided the civil strife that had racked its Balkan neighbors in the 1990s.

But then the National Liberation Army, a rebel group, sprang up, demanding more rights for the ethnic Albanian Muslim community, which makes up a quarter of Macedonia’s population and which had historically felt relegated to second-class citizenship.

Over six months of sporadic fighting, several hundred soldiers, policemen, and guerrillas died, and the rebels advanced to within mortar range of the capital, its airport, and its oil refinery. Full-blown war, Bosnia-style, that could tear the country in two seemed just around the corner.

But, crucially, the United States and the European Union cared enough about stopping that to get involved in negotiating and enforcing peace between the two sides. And for much of the past two decades, they have played an active – sometimes intrusive – role in the country’s affairs.

That is because while Northern Macedonia may be tiny (it is the size of Vermont, with a population smaller than that of Houston, Texas), it is strategically located on Europe’s vulnerable southeastern edge. It is a transit passage for migrants, drugs, and guns. French police, for instance, discovered that one of the AK-47s used in the 2015 massacre at the Bataclan concert hall in Paris came from Macedonia.

The EU and the U.S. were intimately engaged in the peace talks. And they have stood ever since as guarantors of the deal that ended the fighting. The EU even created and dispatched its first-ever autonomous military mission to the country to help keep the peace.

‘Outside pressure brought results’

That was not the last time Western powers waded into Macedonian politics to keep the country on the track they favored.

For a while at the beginning of this decade, Nikola Gruevski, the then-head of the conservative VMRO-DPMNE government, began to indulge increasingly despotic tendencies – a result, critics charge, of the EU soft-pedaling its push for economic and political reform. Mr. Gruevski and a corrupt clique of fellow party members took control of the judiciary, police, intelligence services, state-run firms, and other businesses in what an independent report to the European Commission in 2015 called “state capture.”

The evidence of the Gruevski era is plain to see today in the capital. What I remember as a nondescript city center is now packed with grandiloquent public buildings in the classic Greek style and outsized, overwrought statuary celebrating ancient Macedonian heroes.

As Europe’s migrant crisis mounted, however, the continent came to count on Mr. Gruevski to control the flow of people into the EU. “The EU made ‘stabilitocracy,’ not democracy, its policy,” says Jasmin Mujanović, an expert on Southeast Europe at Elon University in North Carolina.

But when a Macedonian wiretapping scandal led to street protests and then blew up into a full-scale political crisis in 2016, it was again the EU and the U.S. that sponsored interparty talks. Those in turn led to fresh and relatively clean elections that resulted in an opposition majority. And it was those two partners who used heavy diplomatic pressure to enforce the election results in the face of government resistance, according to people involved at the time.

At key moments “the EU and U.S. had common goals … and spoke with one voice,” says a senior Western diplomat here. “That had an effect.”

The ouster of Mr. Gruevski, who fled to Hungary last November after being convicted on corruption charges, “was our victory,” says Borjan Jovanovski, a prominent Macedonian TV journalist, recalling the popular demonstrations. “But it was outside pressure that brought results.”

A Westward-looking country

That dynamic still holds for Zoran Zaev, the current center-left prime minister, who responded to strong calls from the international community to make concessions in his country’s negotiations over its name with neighboring Greece.

Those talks bore fruit last year with an agreement that unblocked North Macedonia’s path to NATO and to accession talks with the EU. Greece had vetoed any progress for 10 years on the grounds that the name the country claimed for itself – Republic of Macedonia – implied territorial claims to Greece’s own northern province of Macedonia.

Mr. Zaev and Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras have been jointly nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for resolving the 27-year-old dispute.

Before Greece imposed its veto, Macedonia had been a Balkan front-runner to start EU membership negotiations and had been set to join NATO.

From the start the country has been clearly oriented toward the West and a keen supporter of the “Euro-Atlantic” geopolitical bloc. Despite delays and setbacks, politicians of all parties and the overwhelming majority of citizens see EU membership as “the North Star” of national policy, says Dr. Mujanović.

Indeed, that promise played a major role in holding the country together. It gave common purpose to the ethnic Macedonian majority and the ethnic Albanian minority, says Erwan Fouéré, a former EU ambassador to Skopje. “Had there not been the prospect of EU membership, which united the country, there would have been much greater fragility,” says Mr. Fouéré. “It was vital, pivotal.”

That prospect was also the motivating force behind the reforms that Skopje has been implementing, with varying degrees of success, on the political and economic front. The aim was to turn North Macedonia into a sufficiently democratic, free, and law-abiding country for the EU to be ready to imagine it as a member of the Union.

“The only fuel that makes the transformation engine run in this region is EU aspirations and monitoring,” says Mr. Osmani.

At the same time, few people in North Macedonia feel any particular ties with or sympathy for Russia, unlike in neighboring Serbia, where Moscow’s influence is strong. Nor is the ethnic Macedonian majority especially open to influence from Turkey, unlike in Muslim-majority Albania and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

“That has made it easier for the West to win over our sentiments,” says Andreja Stojkovski, a local political analyst, especially when Europe and the United States provide the lion’s share of foreign aid to Skopje and when hundreds of thousands of citizens have moved to Western Europe in search of work.

Brussels and Washington have built on such natural inclinations to shore up civil society and a free press, says the journalist Mr. Jovanovski, who at the nadir of Mr. Gruevski’s rule was sent a threatening funeral wreath. And the Helsinki Committee’s Ms. Pirovska still recalls how all the Western ambassadors gathered at an LGBT center in Skopje to show their support after it had been attacked in 2013.

‘The only functioning multiethnic state in the region’

Western diplomats have paid special attention to relations between ethnic Macedonians and Albanians in order to forestall any chance of another 2001-style flare up of deadly violence.

Politicians in both communities seem confident there is no such risk, largely because Albanian grievances at being treated as second-class citizens have been addressed.

“I feel very satisfied,” says Feriz Dervishi, an Albanian businessman and member of the city council in Kumanovo, a provincial town set in rolling farmland a 45-minute drive from the capital. In 2001, he worked closely with the Macedonian mayor to keep the lid on his ethnically mixed town, and the rebellion did not catch fire there.

Mr. Dervishi points to the language rights his community has won. Albanian is Macedonia’s second official language, commonly used in parliament; there are a record number of schools teaching class in Albanian; and proportional hiring practices have been introduced in the public sector.

“When you look at the opportunities I had when I was a young man and the chances in life that my grandchildren have now, there is no comparison,” Mr. Dervishi says.

Sealing ethnic political unity, at least in this electoral cycle, is the fact that Stevo Pendarovski, the social democratic candidate for the presidency, has the backing of the Democratic Union for Integration, which is the largest ethnic Albanian party, and other ethnic parties. That has never happened before.

North Macedonia “is the only functioning multiethnic state in the region,” says Simonida Kacarska, director of the European Policy Institute, a Skopje-based think tank.

On the political reform front, the picture is more mixed. Since taking office in 2017, the government has pushed through a raft of legislation to buttress democratic government against the sort of assault it suffered from Mr. Gruevski. But political expediency has sometimes taken precedence over principle, critics complain.

“We are rebuilding the foundations of the country, and Western perspectives are at the top of the agenda,” says Ms. Pirovska. “But not everything is going in the right direction.”

She cites the persistence of political patronage, rife under VMRO-DPMNE rule and still widespread. She also wonders about the government’s commitment to justice and the rule of law in light of the political deals Mr. Zaev appears to have made with the opposition to ensure parliamentary approval of his flagship accord with Greece.

Critics also question whether reforms to the intelligence agencies will really make them accountable. They worry that without a purge of judges and prosecutors, the judiciary will remain under the government’s thumb.

“There is a big gap between principles and reality,” argues one skeptical European diplomat. “A lot remains to be done.”

The Prespa agreement

Such reservations might cast doubt on Mr. Osmani’s claim that his country is a regional role model. But in one respect, North Macedonia is a standard-bearer. In resolving the name dispute with Greece that had festered for more than a quarter of a century, Skopje and Athens showed their neighbors that compromise could overcome the most recalcitrant problems.

“From a psychological, political, and strategic point of view, putting that problem to rest is very significant for other bilateral disputes in the region,” says Mr. Fouéré, the ex-EU envoy. “It will add pressure” on Serbia and Kosovo, for example, to end their border dispute, he suggests.

But the so-called “Prespa agreement” will not necessarily serve as a blueprint. “Finding an agreement is itself extraordinary and a rare example of good news in the region,” says Clemens Koja, head of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) office in Skopje. “But each case is different.”

That hasn’t stopped Mr. Pendarovski, the social democratic presidential candidate, from campaigning on the Prespa agreement as his government’s signal achievement and “open sesame” moment. He is seeking to replace Gjorge Ivanov of the VMRO-DPMNE, who has been obstructing the government by refusing to sign laws passed by parliament.

Mr. Pendarovski’s VMRO-DPMNE opponent, Gordana Siljanovska, opposes the Prespa agreement and says she would reopen it, though she has not explained how Skopje could join NATO or start membership talks with the EU if she were to do so.

“What is at stake here is the whole North Macedonia project, trying to transform a virtually dictatorial, captured state that was trending away from the West into a legitimate and democratic government that is part of Europe,” says the senior Western diplomat.

How much North Macedonia will be part of Europe is still an open question. After repeated delays, the government had expected to be given a firm start date for accession negotiations when EU heads of government meet in June. But that expectation is looking shaky, especially since French President Emmanuel Macron is insisting the EU should emerge from its current disarray before enlarging its membership.

Another delay in June would be a bitter disappointment to both the government and its citizenry. Those who mutter darkly about malign forces stepping in to fill the political vacuum are probably exaggerating. But rejection would be a dangerous blow to the whole Balkan region, officials warn.

“In our ethnic relations and in our relations with our neighbors, we have built a culture of compromise,” argues Mr. Osmani. “If that is not recognized and we as a government are punished, you won’t find another leader anywhere in the region who will think it is worth making difficult decisions for the sake of stability and peace.”

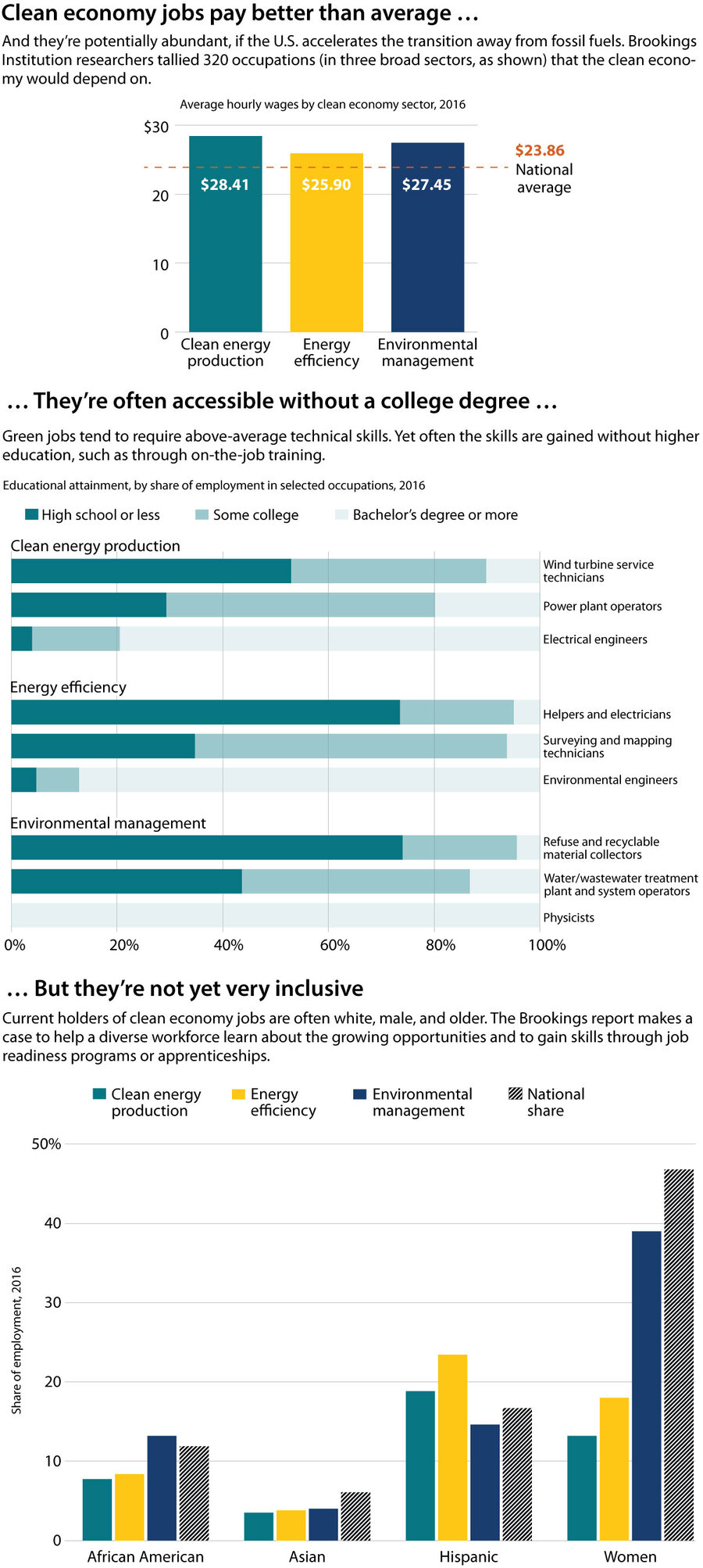

A doubly green deal? Clean energy jobs also pay well.

Discussions of a clean energy transition are often clouded by fears of job loss. But new analysis from the Brookings Institution suggests that such a transition could come with tangible economic benefits.

Recent proposals for a Green New Deal have stirred debate: Would a massive transition toward renewable energy help or hurt the economy?

It’s a question that essentially pits concern about the price tag against a sense of urgency about the risks of greenhouse gas emissions in the long run. A new report gives perspective on one piece of the discussion.

Researchers at the Brookings Institution find that if the economy pivots toward renewable or clean energy, the jobs created would be attractive ones. They generally pay higher than average. They offer a wide range of career paths, and often without needing a college degree – something the economy needs at a time of significant industrial transitions.

“This is a very attractive and multifaceted sector,” and it connects with “a lot of things that we're talking about and concerned about as a nation, even beyond the clean energy transition,” says report co-author Mark Muro. And passing the Green New Deal bill itself isn’t actually key to creating these jobs. Various “decarbonizing” measures could open up that path, Mr. Muro says. – Mark Trumbull

Brookings Institution

Holy grail: how Hollywood can get religious movies right

Easter is a natural time to roll out movies meant to uplift and inspire. But finding the right balance of depth and realism often eludes filmmakers. Where is there room for improvement in faith on film?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Stephen Humphries Staff writer

More Christian movies are being produced today than in Cecil B. DeMille’s heyday. They range from multiplex hits such as “God’s Not Dead” and “War Room” to multitudinous direct-to-video flicks that make Hallmark TV movies look high-budget by comparison. Even Mel Gibson’s blockbuster, “The Passion of the Christ,” reportedly has a sequel on the way.

But as with new Easter-release “Breakthrough” – a film based on the true story of a mother who saves her hospitalized son’s life through prayer – the stories and theology in Hollywood fare are often too shallow or too literal. Movie critics and theologians wonder why that has to be and suggest that filmmakers instead be less preachy and obvious with their messages.

Ultimately, humans tend to learn best via narrative, says Abby Olcese, who writes for Christian publications such as Sojourners and Relevant. The Bible is full of rich stories about what mankind’s relationship to God looks like, she notes. Film has the capacity to operate in the same way. “What Christian movies should aspire to,” she says, “is telling a legitimately good story and letting the content speak for itself.”

Holy grail: how Hollywood can get religious movies right

As a Christian, Vox film critic Alissa Wilkinson was initially intrigued by “Breakthrough,” a new movie timed to coincide with Easter and based on the true story of a mother who saves her hospitalized son’s life through prayer.

Despite the likable cast, led by Chrissy Metz of TV’s “This is Us,” Mrs. Wilkinson ultimately found “Breakthrough” generic. “It’s very much one of those films that’s like ‘Do you believe in miracles?’” She points out that rather than diving deeper into theological questions, as when one character asks why her ill husband wasn’t similarly saved, the movie simply leaves them hanging.

Today more Christian movies are being produced than in Cecil B. DeMille’s heyday. They range from multiplex hits such as “God’s Not Dead” and “War Room” to multitudinous direct-to-video flicks that make Hallmark TV movies look high-budget by comparison. Even Mel Gibson’s blockbuster, “The Passion of the Christ,” reportedly has a sequel on the way. But as with “Breakthrough,” the stories and theology are often too shallow or too literal, leaving those who are following this fare asking why. Movie critics and theologians suggest that filmmakers instead be less preachy and obvious and that they start by taking a page from the Good Book.

“Popular art created by Christians or for Christians really seems to have taken a turn for the worse. And it parallels, I think, a superficiality in churches,” says Jared C. Wilson, director of the Pastoral Training Center at Liberty Baptist Church near Kansas City, Missouri. “They’ve been discipled according to just more of a sentimental kind of Christianity rather than a more mature or fully orbed biblical Christianity.”

Swap sermons for ideas

Fewer Americans are going to church, according to the Pew Research Center. But 80% still believe in some higher power or spiritual force, and many are still watching movies. To reach those who prefer recliner seats to church pews, Mr. Wilson says spiritually inclined moviemakers first need to learn the classic storyteller’s dictum: show, don’t tell. That includes an economy of language. Unless you happen to have Morgan Freeman delivering an Aaron Sorkin soliloquy to a John Williams soundtrack, it’s best to avoid sermonizing on-screen.

A far more effective approach, he adds, is to allow characters’ actions to convey ideas. In other words, let Christianity inform the story rather than starting out with a message agenda.

William Romanowski, author of “Cinematic Faith,” points to “Tender Mercies” as an example. In that 1983 film, Robert Duvall plays a country music artist who has a conversion experience early in the story. “He starts making decisions in a different kind of way, living a different way. And it changes the way that he loves someone,” says Mr. Romanowski, a professor at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan. “Those are the films I think that are more engaging in terms of making God real in the world that we live in.”

That complexity of character – found in the Bible itself – is what more filmmakers should focus on, say critics and theologians. David, for example, went from heroic Goliath-slayer to, at one point before he repented, an adulterous and murderous king (perhaps the original “Breaking Bad”). Audiences relate to messy, complex characters whose stories may defy easy resolution. Paul Schrader’s 2018 movie “First Reformed,” about a priest experiencing a spiritual crisis, exemplifies that approach, says Mrs. Wilkinson.

“I was talking to an artist yesterday who was saying what we’re looking for is to make art that reflects you back to you – not so you can see yourself, but so you can see yourself differently and decide if that’s what you want to be,” says Mrs. Wilkinson. “People experience it, and then they are pushed into reasking big questions like what is the meaning of life, what are we doing here, how do we love our neighbor, and what happens after we die.”

Christian storytellers can learn a lot from those Hollywood artists who are able to challenge their audiences, says Andrew Barber, who writes film reviews for Christianity Today and The Gospel Coalition. As an example, Mr. Barber cites Martin Scorsese’s 2016 movie “Silence,” in which two 17th-century Jesuit missionaries find their faith tested in Japan.

“It asks ‘What does a Christian who fails look like?’” says Mr. Barber, who has a master of divinity degree from Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis. “I think it has a very strong heretical line at the end. But it is incredibly earnest and at moments very devotional. I found it very powerful and asking really interesting questions. But I think it’s a movie that would be be a great conversation starter for a lot of Christians.”

The Gibson effect

Mr. Barber says many Christians still haven’t forgiven Mr. Scorsese for his 1988 movie “The Last Temptation of Christ.” That movie generated both controversy and some thoughtful discussion by positing that Jesus was briefly tempted to escape crucifixion and instead live out a life that included marrying Mary Magdalene. Ultimately, it flopped at the box office.

That hasn’t stopped Hollywood from rebooting, reimagining, and recasting Jesus of Nazareth even more times than Spider-Man. Credit Mr. Gibson. Scores of movies have tried to replicate the $612 million global success of “The Passion of the Christ.” The reported sequel is said to feature Jim Caviezel reprising the role of Jesus after his resurrection.

Joaquin Phoenix is the latest actor to don the crown of thorns. He costars in “Mary Magdalene,” released in the United States last weekend, which retells the Passion narrative from the perspective of the titular female apostle, played by actress Rooney Mara.

In her Vox review of the film, Mrs. Wilkinson praised its quietly subversive feminist angle, but she felt that its dreamy, ethereal style undercut its realism. Fantastical depictions also dogged Darren Aronofsky’s “Noah,” which featured a giant, six-armed rock monster that looked like it had wandered in from a Thor movie.

If Hollywood wants to make better biblical movies, it needs a more inspired view of the scriptures, nuanced but not so narrowly focused, says Abby Olcese, who writes for Christian publications such as Sojourners and Relevant. “They think that all Christians believe that the Bible is 100% right all the time,” says Mrs. Olcese. “The reality is that there’s a lot more division within the church as to how much of it is divinely inspired but written by man.”

Ultimately, though, humans tend to learn best via narrative, she says, and the Bible is full of rich stories about what mankind’s relationship to God looks like. Film has the capacity to operate in the same way.

“What Christian movies should aspire to is telling a legitimately good story and letting the content speak for itself.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

When saying no to a president saves democracy

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Few Americans will read special counsel Robert Mueller’s report. That’s OK, as the main conclusions are well known. A few parts, however, offer a lesson on how individual acts of conscience can make a big difference. Mr. Mueller praises some of those around President Donald Trump for standing up for rule of law. A key person was former White House counsel Donald McGahn. Twice the president told him to fire the special prosecutor, and twice Mr. McGahn refused, perhaps saving American democracy from a constitutional crisis.

It is not easy to say no to an American president. In many cases, it takes moral courage for a public servant to act on principle, such as the ideal that justice should be nonpolitical. Mr. McGahn’s actions are an echo of one taken by Elliot Richardson, the attorney general who in 1973 refused President Richard Nixon’s order to fire a special prosecutor probing the Watergate scandal.

Mr. McGahn’s example is particularly useful as the United States continues to battle a core reason for the Mueller probe: Russian attempts to persuade Americans of false stories. Defying such propaganda requires an inner compass to discover what is true and to act on it.

When saying no to a president saves democracy

Few Americans will read the public portions of special counsel Robert Mueller’s report. That’s OK, as the two main conclusions are well known: The Trump campaign did not collude with Russia to influence the 2016 election, and yet President Donald Trump tried to influence the investigation. Congress will now decide if the president did obstruct justice. A few parts of the report, however, offer a lesson on how individual acts of conscience can make a big difference in a democracy.

Mr. Mueller praises some of those around Mr. Trump for standing up for rule of law. “The President’s efforts to influence the investigation were mostly unsuccessful, but that is largely because the persons who surrounded the President declined to carry out orders or accede to his requests,” Mr. Mueller wrote.

A key person was former White House counsel Donald McGahn (pronounced “McGann”). Twice the president told him to fire the special prosecutor, and twice Mr. McGahn refused, perhaps saving American democracy from a constitutional crisis. Mr. Mueller found Mr. McGahn, who resigned last October, to be “a credible witness with no motive to lie or exaggerate given the position he held in the White House.”

It is not easy to say no to an American president. One famous case occurred in 1980 when Secretary of State Cyrus Vance opposed President Jimmy Carter’s military operation in Iran to rescue American hostages. Mr. Vance resigned, and the operation failed as he forewarned.

In such cases, it takes moral courage for a public servant to act on principle, such as the ideal that justice should be nonpolitical. Mr. McGahn’s actions are an echo of one taken by Elliot Richardson, the attorney general who in 1973 refused President Richard Nixon’s order to fire a special prosecutor probing the Watergate scandal.

“The more I thought about it,” Mr. Richardson wrote later, “the clearer it seemed to me that public confidence in the investigation would depend on its being independent not only in fact but in appearance.” In 1998 he won the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Mr. McGahn’s example of moral independence is particularly useful as the United States continues to battle a core reason for the Mueller probe: Russian attempts to persuade Americans of false stories via social media. Defying such propaganda requires an inner compass to discover what is true and to act on it. Voters, like public servants, have a duty beyond allegiance to a person or to accepting what they read online. They must live by the values that bind a democratic society. Sometimes that means saying no.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Continuity

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Florence H. Lawson

“Love lives on, and Life unfolds/ Man’s immortality,” concludes today’s poem, which points to Easter’s message of life in God, from whom we can never be separated.

Continuity

You say he died. Do you not know

That Love is our true Life?

The calm, pure joy of peace divine

Remains, and heals all strife.

Love gone? Life fled? Impossible!

We only wake to see

That Love lives on, and Life unfolds

Man’s immortality.

In the end of the sabbath, as it began to dawn toward the first day of the week, came Mary Magdalene and the other Mary to see the sepulchre.... And the angel answered and said unto the women, Fear not ye: for I know that ye seek Jesus, which was crucified. He is not here: for he is risen, as he said.

– Matthew 28:1, 5, 6

That Life is God, Jesus proved by his reappearance after the crucifixion in strict accordance with his scientific statement: “Destroy this temple [body], and in three days I [Spirit] will raise it up.” It is as if he had said: The I – the Life, substance, and intelligence of the universe – is not in matter to be destroyed.

– Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 27

Poem originally published in the July 26, 1952, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

‘The tulips make me want to see’

A look ahead

That’s it for today. Be sure to come back on Monday, when we’ll have a story on a new Ikea furniture collection by African designers. Can a couch change people’s mindsets about African art?