- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Death penalty with dignity? Supreme Court reopens debate.

- Not criminal, but not ethical either: Mueller reignites a political debate

- Texas Republicans wanted a no-drama session. Here’s what happened.

- GMO could help bring back the American chestnut. But should it?

- In Notre Dame fire, a reminder of history’s complexity

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Overcoming outrage: surprising lessons from a Twitter war

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Very quickly, Justin Wolfers realized that his tweet had not gone according to plan. Earlier this month, the economist had meant to say that good sociologists are needed to better shape vital policy discussions. Instead, he’d basically called them all lazy.

It’s what happened next, however, that makes this a story worth sharing.

Some people responded with “gleeful outrage.” This had the effect of hardening his resolve and didn’t persuade him, Mr. Wolfers added in a later tweet. Some, however, pushed him to do better, asking if he understood how his words hurt causes and people he cared about. It was the latter group, he said, who convinced him he was wrong.

Not only that, they changed him more deeply. “It’ll shape how I try to win arguments,” he said, adding that a friend “says to treat people with love, even when they’re wrong.”

One of the most momentous and overlooked findings of the 20th century is that nonviolence works far better than violence. Mr. Wolfers’ aborted Twitter war suggests we can marinate in that lesson even more deeply. Democratic institutions the world over are doing an admirable job of driving down levels of physical violence. But toxic discourse on social media and in politics suggests a next frontier for progress might be in finding ways to practice nonviolence not only in action, but in thought and speech.

Now, here are our five stories for today. We examine why politics struggles to deal with the gray areas of ethics, how the Texas Legislature is debating conservatism’s course ahead, and whether it’s right to save an iconic tree from extinction.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Death penalty with dignity? Supreme Court reopens debate.

How should American states treat prisoners sentenced to die? The answer goes to how the country views justice, and shifts on the Supreme Court are making the question unexpectedly urgent.

The newly constituted Supreme Court is poised to become the most supportive of the death penalty in decades, many observers say. Front and center in a number of recent cases: the tension between the principle of human dignity and the practical needs of justice, for which, some say, society must hand down timely, harsh punishments to both punish and deter the worst of crimes.

However, both liberals and conservatives have voiced alarm that in many cases the court’s recent rulings on cruel and unusual punishment and the religious freedoms of those on death row are chipping away at the concepts of dignity. “What is our sense of humanity, and how do we want to carry out our punishments?” asks Robin Konrad, an assistant professor at Howard University School of Law.

The debate has had scholars reexamining the principles governing capital punishment. “We just see some really strong crosswinds on these cases right now,” says Corinna Lain, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law. “So I think this is a question we have to be asking now, because what principles are behind the death penalty right now?”

Death penalty with dignity? Supreme Court reopens debate.

When Fleet Maull was serving his 14-year sentence in a maximum-security prison more than three decades ago, he spent a lot of time with men who were seriously ill or dying.

The path that led him there was “a little weird,” he says. In the 1970s, he was a “countercultural expat” and a highly educated psychotherapist traveling the world, stopping to study Buddhism with Tibetan masters. To fuel his peripatetic lifestyle, he was a low-level drug peddler smuggling cocaine.

“Which shows you what a knucklehead I was,” says Dr. Maull, who was caught and convicted in 1985 and given the mandatory minimum sentence that altered his life.

Today, nearly 20 years after his release, he calls the timing of his conviction “auspicious” and says, without irony, that “I was in the right place at the right time.” His imprisonment set him on the difficult path to discover what has become his life’s purpose: to help prisoners “live and die with dignity and humanity and with as little pain as possible.”

This aim to uphold the humanity and minimize the pain of those who have committed heinous acts is not a natural impulse for most people. But as a Buddhist spiritual adviser and a prisoners’ rights activist who founded the National Prison Hospice Association while serving his sentence, Dr. Maull sees this goal as springing from an important principle. It's rooted not only in the teachings of the world’s major religions, but also woven into the political ideals of Enlightenment liberalism, in which prohibitions against “cruel and unusual” punishment began to evolve over the past few centuries.

This year, as a newly constituted Supreme Court has begun to readdress capital punishment, the tension between the principle of human dignity and the practical needs of justice has come into focus in a way the United States has not seen for decades, experts say. In fact, the court’s newest conservative justices are poised to make it the most supportive of state executions in decades.

“Capital punishment cases have come out of the woodwork in a way that I hadn’t really been anticipating, in part because it’s been kind of a dormant issue for a while,” says Kathryn Heard, a legal scholar at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Reexamining principles

In many cases, the Supreme Court’s recent rulings have alarmed both liberals and conservatives, who say decisions on the religious freedom of those on death row, as well as the extent of the Constitution’s prohibitions against cruel and unusual punishment, have been chipping away at modern concepts of dignity.

Led by Justice Neil Gorsuch, the five conservative justices have expressed a new impatience at the constant stays and decadeslong litigation that characterize a lot of capital cases. They have suggested that most death row appeals are simply “pleading games” made in bad faith, thwarting the demands of justice.

In two cases decided this April, Justice Gorsuch, writing for a 5-4 majority each time, rejected the appeals of two men, one in Missouri and one in Alabama, who argued that the lethal injection protocols of these states would cause them an unusual amount of pain, given their individual conditions.

“Courts should police carefully against attempts to use such challenges as tools to interpose unjustified delay,” Justice Gorsuch wrote in the case that dismissed the claims of the Missouri inmate, who argued that, because of his rare medical condition, the state’s lethal injection protocol could cause him to die in excruciating pain.

Aside from technical issues of Constitutional jurisprudence, Dr. Maull and others have posed difficult, if fundamental, questions.

Is there a limit to the kind of pain prisoners being executed should experience, even assuming that it will not be pain-free? At the time of execution, should prisoners have a right to have a religious cleric of their own faith or denomination at their side?

“We just see some really strong crosswinds on these cases right now,” says Corinna Lain, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law in Virginia. “So I think this is a question we have to be asking now, because what principles are behind the death penalty right now? It’s really not about deterrence anymore,” she says. “As it’s been shown again and again, it doesn’t exist. It’s not about the incapacitation of dangerous people. It’s all retributivism. That’s it.”

“So why should we care?” Professor Lain continues. “Why should we care about how they’re housed? Why should we care about the method of their executions, given the way they treated their victims? And why should we care whether they have a person comforting them when the state puts them to death?”

“We have to care, because we can’t use the baseline of horrible crimes as our standard for civilized society,” she adds. [Editor's note: This part of the quote was added later for clarity.]

‘Inspired to serve’

Looking back over his experience in prison, Dr. Maull says it was strange that federal officials sent him to the U.S. Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri, rather than a medium-security penitentiary. Dr. Maull found himself among the cadres of healthy prisoners who were needed to help run the maximum-security hospital just as dozens of prisoners with AIDS were being transferred there from around the country.

“When I got there, I realized I was in this hell realm,” says Dr. Maull. “I found myself in this world of tremendous suffering, deep suffering, even without the AIDS crisis.”

Suddenly, after being immersed in the meditative practices of Buddhism for 10 years, the convicted drug-runner found himself bathing prisoners with disabilities, assisting peers with mental illnesses, and teaching mindfulness to blind inmates or those dealing with extreme pain.

“I was just inspired to serve,” says Dr. Maull, who embraced the work of making things better for dying men confined in maximum security.

Rebalancing religious freedoms

Earlier this year, the high court denied the appeal of a Muslim death row inmate in Alabama who wanted his imam at his side at the moment of his death. Prison policy would allow only a Christian chaplain at his side. Many religious conservatives decried the decision.

“The state’s obligation is to protect and facilitate the free exercise of a person’s faith, not to seek reasons to deny him consolation at the moment of his death,” wrote the conservative social critic David French in the National Review.

Just a few weeks later, the court stayed the execution of a Buddhist inmate in Texas, even though the facts of his case were nearly exactly the same, experts say.

“What the State may not do, in my view, is allow Christian or Muslim inmates but not Buddhist inmates to have a religious adviser of their religion in the execution room,” wrote Justice Brett Kavanaugh in a 7-2 decision that left many court observers puzzled. After the decision, Texas banned all religious chaplains and advisers from the death chamber during an execution.

Which makes sense, says Kent Scheidegger, legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation in Sacramento, California, and a strong advocate of the death penalty for those who commit horrible crimes.

“Certainly a person who is about to be executed should be allowed to consult with his adviser, and for many religions, confession at the end is considered very important, and that should all be accommodated,” says Mr. Scheidegger, who has written more than 150 briefs for the Supreme Court advocating for the rights of victims. “But actually having a spiritual adviser in the execution room is not necessary, and if it can’t be done as a practical matter for all religions, then it should be done for none of them.”

“But of course we should avoid making an execution undignified, or an unnecessarily painful event, to the extent we can as a practical matter,” he says. “The penalty of death is just the penalty of death, and we shouldn’t be heaping additional things on it, and I don’t think anybody today thinks we should.”

What is ‘cruel and unusual?

The Supreme Court’s new conservative majority, however, appears to be embracing a different understanding of what constitutes an “unusual” amount of pain during an execution, scholars say.

In previous cases, the Supreme Court has done away with certain methods of execution that violate “evolving standards of decency,” ruling that states should employ less painful methods at their disposal.

In his majority decision denying the Missouri man’s appeal, however, Justice Gorsuch wrote that the Constitution does not guarantee a painless death and that “the question in dispute is whether the State’s chosen method of execution cruelly superadds pain to the death sentence.”

In previous opinions, only the late Justice Antonin Scalia and Justice Clarence Thomas advocated this position. In their view, the Constitution sets a high bar, only prohibiting states from “superadding” extra “terror, pain, or disgrace.”

But the principles behind evolving standards of decency are woven into the very origins of the secular, liberal state, says Professor Heard at Dickinson College, who traces the evolution of the prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment to the Enlightenment.

As an emerging middle class began to challenge the hierarchy of kings and lords, philosophers began to insist on an individual’s “inalienable rights,” including freedom from cruel and unusual punishment, she says.

“Public displays of both state-sponsored violence and established religious belief delegitimized a state’s claims to securing the rights, freedoms, and liberties of all individuals,” says Professor Heard.

This shift in thought is in many ways fundamental to the evolving standards of decency that have governed the implementation of the death penalty since then. Once-common punishments, including the execution of people committing nonlethal crimes or the execution of minors or the mentally disabled, are now widely considered cruel and unusual.

“So what does that mean for us as a society?” says Robin Konrad, an assistant professor at Howard University School of Law in Washington and a critic of the Supreme Court’s recent capital cases. “I mean, really, the issues surrounding the death penalty are, in general, about this as much as anything: What is our sense of humanity, and how do we want to carry out our punishments? And if we are going to have a death penalty, how do we want to carry it out, and are we OK with saying, well, it’s OK if we torture people to death?”

Common humanity

In the Alabama case in which the inmate said the lethal injection would cause him an unusual amount of pain, state Attorney General Steve Marshall echoed many of the concerns of the Supreme Court’s majority, saying the family of the death row inmate’s victim were “revictimized” and “deprived of justice.” The inmate had “dodged his death sentence for the better part of three decades ... by desperately clinging to legal maneuverings to avoid facing the consequences of his heinous crime,” Attorney General Marshall said.

“A lot of inmates will drag everything out as long as they can, and there are plenty of judges willing to accommodate them,” says Mr. Scheidegger at the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation. “But I think it’s possible now that we can make some progress on these kinds of delays.”

Legal matters aside, for Dr. Maull, helping prisoners live and die with dignity and humanity and with as little pain as possible is an expression of compassion that asserts our common humanity.

“I don’t think any of us can imagine what it’s like to face death in prison,” he says. “These prisoners are often dying apart from their families, unwitnessed, and with just about the least dignity a human being can die with.”

“So we try to bring as much dignity to their journey and to their deaths as we possibly can.”

Not criminal, but not ethical either: Mueller reignites a political debate

President Trump’s actions with Russia didn’t bring criminal charges but did raise ethical concerns. That gray area has long been hard to address politically. The final say often falls to voters.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

American history is replete with examples of leaders who violated commonly accepted morals. Some found a public willing to move on; some did not.

Special counsel Robert Mueller’s report lays bare copious contacts between Russians and Trump campaign associates but finds no criminal conspiracy. It also chronicles 10 episodes that Mr. Mueller investigated for potential obstruction of justice by President Donald Trump, leaving a final verdict to Congress.

Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani inadvertently brought the question of moral versus criminal standards to the fore over the weekend on CNN, saying “There’s nothing wrong with taking information from Russians.” Mr. Giuliani was referring to the infamous Trump Tower meeting in June 2016 between senior Trump campaign officials and a Russian lawyer offering “dirt” on Hillary Clinton. When the ethics of taking information from a foreign source was raised, Mr. Giuliani pushed back. “We’re going to get into morality?” he asked. “That isn’t what prosecutors look at – morality.”

“Robert Mueller uncovered a lot of smelly, uncomfortable stuff,” says Gil Troy, a presidential scholar at McGill University in Montreal. “Too many of our leaders think that not being indictable is the moral standard for leadership. That’s not my standard.”

Not criminal, but not ethical either: Mueller reignites a political debate

The Mueller report is bringing questions of ethics and morality in government once again to the forefront of a vigorous public debate.

Jammed with primary sources, special counsel Robert Mueller’s 448-page journey into the inner workings of the Trump campaign and early presidency pops with detail: It is a tale of palace intrigue, deceit, and attempts to collaborate with a foreign power and hinder a federal investigation.

The report lays bare copious contacts between Russians and Trump associates during the campaign, though it finds no criminal conspiracy. It also chronicles 10 episodes that Mr. Mueller investigated for potential obstruction of justice by President Donald Trump, leaving a final verdict to Congress.

“Robert Mueller uncovered a lot of smelly, uncomfortable stuff,” says Gil Troy, an expert on the U.S. presidency at McGill University in Montreal. “As an American citizen, I get encouragement that our law enforcement officials in very high-profile cases are careful not to throw people into the courts, let alone jail, without a very high standard of proof. That’s my happy takeaway.”

Professor Troy’s “unhappy takeaway” comes when he looks more broadly at the behavior of President Trump and some of those around him as well as the scandals that embroiled both President Bill Clinton and his wife, Hillary Clinton, the Democrats’ 2016 presidential nominee.

“I find that too many of our leaders think that not being indictable is the moral standard for leadership,” Mr. Troy says. “That’s not my standard.”

Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani inadvertently brought the question of moral versus criminal standards to the fore over the weekend on CNN, saying “There’s nothing wrong with taking information from Russians.” Mr. Giuliani was referring to the infamous Trump Tower meeting in June 2016 between senior Trump campaign officials, including Donald Trump Jr., and a Russian lawyer offering “dirt” on Mrs. Clinton.

Such a contribution from a foreign national might have violated federal election law, though at the meeting no information about Mrs. Clinton was produced. Still, many observers commented that the offer of help from a hostile foreign power should have led the president’s son to contact the FBI. Instead, the junior Mr. Trump’s emailed reaction was “I love it.”

But when the ethics of a campaign taking information from a foreign source was raised, Mr. Giuliani pushed back. “We’re going to get into morality?” he asked. “That isn’t what prosecutors look at – morality.”

Politics or principle?

American history is replete with examples of leaders who violated commonly accepted morals. Some were protected from scrutiny at the time, including by the press. Those who were exposed sometimes found a public willing to move on, sometimes not.

Almost always, elections are the preferred reset button.

Public versus private morality remains an important if occasionally murky distinction. Adultery, for example, remains unacceptable to many Americans but isn’t an impeachable offense. It was lying under oath and obstructing justice that formed the basis of President Clinton’s impeachment.

President Richard Nixon, mired in the Watergate scandal, resigned when faced with certain impeachment and expulsion. But no other president has been forced from office early. Short of impeachment, a step twice taken by the House, there’s also the option of a censure in cases of ethical violations. The Senate has adopted such a resolution against a president only once: against Andrew Jackson in 1834.

Some Trump critics, concerned by the political risks and impact on the country of impeachment, have proposed that Congress censure Mr. Trump. To others, censure is not enough.

“This is not about politics; this is about principle,” said Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a Democratic candidate for president, in a CNN town hall on Monday. She supports impeaching Mr. Trump.

“To ignore a president’s repeated efforts to obstruct an investigation into his own disloyal behavior would inflict great and lasting damage on this country,” Senator Warren tweeted last Friday.

Among congressional Republicans, the near-silence following the Mueller report has been deafening.

In the Senate’s Republican caucus, Mitt Romney of Utah has been alone in speaking out forcefully. In a statement issued last Friday, the freshman senator said he was “sickened at the extent and pervasiveness of dishonesty and misdirection by individuals in the highest office of the land, including the president.”

Some of the Trump loyalists of today, who gloss over the wrongdoing laid out in the Mueller report, went hard after Mr. Clinton during his impeachment in 1999.

“You don’t even have to be convicted of a crime to lose your job in this constitutional republic if [the Senate] determines that your conduct as a public official is clearly out of bounds in your role,” said then-Rep. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., at the time. “Impeachment is about cleansing the office. Impeachment is about restoring honor and integrity to the office.”

This week, now-Senator Graham tweeted that “using the Mueller report as a basis for impeachment would be an unhinged act of political retribution.”

Guardrails gone

In the first two years of the Trump presidency, a number of key aides served as ethical guardrails, preventing the president from acting on his own worst instincts. According to the Mueller report, many either ignored or slow-walked orders they feared would land the president in trouble.

“The president’s efforts to influence the investigation were mostly unsuccessful, but that is largely because the persons who surrounded the president declined to carry out orders or accede to his requests,” the report wryly states.

Mr. Trump now has a team that better fits his style, including an attorney general, William Barr, who shaped the Trump spin around the Mueller report (“No collusion, no obstruction”) weeks before it was released to the public.

Acting chief of staff Mick Mulvaney is seen more as a cheerleader for Mr. Trump’s instincts than a check on them. He encouraged, for example, the president’s recent push in court to overturn the Affordable Care Act despite the lack of a GOP replacement plan.

“They’ve got an acting chief of staff who seems to be reinforcing all of Trump’s worst political instincts,” says Chris Whipple, author of “The Gatekeepers,” a history of White House chiefs of staff.

The most effective chiefs of staff, Mr. Whipple says, are those willing to give the president bad news. But that takes having a president willing to receive it, and with Mr. Trump that’s not always the case. Before resigning, former Homeland Security chief Kirstjen Nielsen was told not to discuss Russian interference in the 2020 election with Mr. Trump, according to The New York Times. Such talk raised questions about the legitimacy of Mr. Trump’s election, Mr. Mulvaney reportedly implied.

At least one Republican observing from the sidelines sees the Mueller report as a cautionary tale for the president and his team going forward.

“I hope POTUS, his family and staff realize how close POTUS came to an obstruction charge,” tweeted Ari Fleischer, former press secretary to President George W. Bush, using the acronym for president of the United States.

“Laws are made to restrain presidents, even genuinely frustrated presidents who are accused of things they didn’t do,” Mr. Fleischer continued. “Presidents can’t instruct their staffs to lie. Ethics matter.”

Texas Republicans wanted a no-drama session. Here’s what happened.

As the largest Republican-led state, Texas is considered a laboratory for conservative policy and politics. Its leadership wants to focus on pocketbook issues. But some see that as not conservative enough.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Sitting in the shade outside the Texas Capitol on a humid afternoon, Jenny Trumphour said she traveled 200 miles from Fort Worth for a rally – on property taxes.

“It’s been going on for years,” she says. The Texas Legislature “promised reform and they haven’t delivered on it.”

This was going to be the session: The governor, lieutenant governor, and new speaker of the House had all committed to unity and focusing on meat-and-potatoes issues like lowering property taxes and increasing school funding and security. But with six weeks left, property tax legislation has yet to make its way to the governor’s desk and tensions are high. So far, 30 bills to restrict abortion rights have been proposed, though only two have progressed. Other bills would open the door to discrimination against LGBTQ residents.

The tension comes after Democrats posted their best election in decades, and after the last legislative session was dominated by debate over a failed transgender bathroom bill.

That should have been a lesson, says state Sen. Kel Seliger, a Republican from Amarillo. “It doesn’t appear to have very much,” he says. “It should have [been] because of the messages to be gained there, primarily by Republicans.”

Texas Republicans wanted a no-drama session. Here’s what happened.

Texas state Sen. Kel Seliger thought things would be different in the Capitol this year.

Republicans have kept a firm grip on politics here for 17 years, controlling both the governor’s mansion and the Legislature, and in that time Texas has come to define American conservatism. Last November that grip loosened ever so slightly.

Inspired by Beto O’Rourke’s surprisingly strong challenge to U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz, Texas Democrats enjoyed their best election in decades, flipping two seats in the U.S. House as well as two seats in the state Senate and 12 seats in the state House. (Republicans still hold majorities in both state legislative chambers.) Many Republicans who did win, like Senator Cruz, won narrowly.

That this occurred a year after a contentious legislative session dominated by debate over a transgender bathroom bill should have been a lesson, says Senator Seliger, a Republican from Amarillo.

“It doesn’t appear to have very much,” he says. “It should have [been] because of the messages to be gained there, primarily by Republicans.”

Those messages were that Republicans were spending too much time on socially conservative issues, such as abortion rights and LGBTQ rights. While the bathroom bill failed to pass in 2017, so too did efforts to lower property taxes, which created a perception among many Republican voters in Texas that, despite the party’s control of state government, “the Legislature was abandoning its responsibilities on big issues,” says Brandon Rottinghaus, a political scientist at the University of Houston.

“Most Republicans saw the 2017 session end in disaster for both Republican principles and the Republican brand,” he adds. Now “they’re willing to focus, at least temporarily, on other priorities.”

Indeed, this session began with Texas government’s “big three” – Gov. Greg Abbott, Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, and new Speaker of the House Dennis Bonnen – pledging a united front to focus on school finance and property tax reform, Hurricane Harvey relief, and school security. While those spinachy issues remain priorities, that hasn’t prevented legislators becoming bitterly divided over them – both Republicans against Democrats, and Republicans against Republicans.

“The session began with this initial comity. There was a lot of bipartisan rhetoric,” says Ann Bowman, professor at the Bush School of Government & Public Service at Texas A&M University. “But now we’re in the heart of the session the tension has got really high.”

It is a different kind of tension, however, with forays into cultural wedge issues often halfhearted. This angers some conservatives here who believe that, as the biggest Republican-controlled state in the country, Texas is considered a laboratory for conservative policy and politics. The tea party movement began here, for example. But for the most part Texas voters see meat-and-potatoes issues like property taxes and education as top priorities for the Legislature. The current strategy is geared toward preserving Republican control of the Texas Legislature in 2020 so Republicans can control redistricting after the 2020 census. The looming question in Texas politics: What happens then?

“You’re likely to see [social issues] surge back. The conservative wing of the party has already geared up to put the screws to Republicans they think haven’t been conservative enough,” says Professor Rottinghaus.

“Bringing attention to these conservative social issues is going to turn off a lot of voters,” he adds, “and it could exacerbate the speed of Texas turning more purple.”

The ho-hum culture wars?

Socially conservative issues haven’t vanished from the Texas Legislature. One need only look at the roughly 30 bills introduced seeking to regulate and restrict abortion.

Some of the more extreme bills have made national headlines, such as a bill that would make women who get abortions subject to the death penalty. So far, two abortion-related bills have made meaningful progress.

The nearest “bathroom bill” analogue this year is SB17, legislation that would allow occupational license holders like social workers or lawyers to cite “sincerely held religious beliefs” when their licenses are at risk due to professional behavior or speech. Like last term’s bathroom bill, Democrats, LGBTQ advocates, and the state’s business community have come out against it, calling it a “license to discriminate” that is bad for business.

Another bill in the state senate, SB15 – which began as legislation to prevent cities from enacting paid sick leave ordinances – has been amended in a way that could undermine nondiscrimination ordinances in cities.

This approach to addressing polarizing social issues is evidence of Texas Republicans’ shift in priorities, says Mark Jones, a political scientist at Rice University.

“We haven’t seen nearly as much polarizing legislation, and even the [polarizing] legislation we have seen has been somewhat halfhearted,” he adds.

One reason much of the more controversial social legislation is unlikely to go anywhere this year is because of the change in state house speaker. Previous sessions were defined by heated public battles between Lt. Gov. Patrick – a former talk radio host and the face of far-right Texas politics, who leads the Senate – and Joe Straus, then the moderate, business-minded Republican leader of the House of Representatives.

Mr. Straus retired last summer, and Representative Bonnen replaced him with unanimous support from the lower chamber. More conservative than Mr. Straus, Mr. Bonnen has a better working relationship with Mr. Patrick and Governor Abbott, but he has combined that with a longer-term view to protect Republican control of Texas.

“Bonnen is conservative [but] he’s also pragmatic,” says Professor Jones. “He’s not going to try and pass legislation so he can score quick political points with Republican primary voters if it would hurt the party’s longer term efforts to retain its majority in 2020 and beyond.”

Clock is ticking

All this isn’t to say that debate over issues like property tax relief has been plain sailing. With no state income tax, property taxes are the primary source of funding for public schools, and state funding has been decreasing for years. With six weeks remaining in the session, legislation that would attempt to lower property taxes and increase public school funding has yet to reach Mr. Abbott’s desk.

The debate has been fierce at times. So committed is Mr. Patrick to passing property tax relief that he made moves to trigger a “nuclear option” in Senate procedure, doing away with a three-fifths vote requirement to open debate on a bill that is seen as encouraging bipartisan debate.

The threat moved Mr. Seliger, one of the few moderate Republicans in the Senate, to vote in favor of debating the bill – avoiding the nuclear option – before voting against the bill itself.

“My [first] vote wasn’t for that measure, it was for the Senate itself and its tradition as a deliberative body,” he said last week on a panel organized by The Texas Tribune.

Which all points to the idea that, in the Texas Legislature, even when things change, nothing really changes.

“The fact that the issues that are focal points are different doesn’t change the session,” says Mr. Seliger. “This time it’s about tax and property tax, last time it was about bathroom bill, the time before that it was something else.”

Some Texans are happy with the chosen agenda, however. Sitting in the shade outside the Texas Capitol on a humid afternoon last week, Jenny Trumphour had traveled 200 miles from Fort Worth for a property tax rally.

“It’s been going on for years,” she says. The Legislature “promised reform and they haven’t delivered on it.”

“Some of the issues they take up just don’t make any sense,” she adds. “They should do what they promised people, listen to their constituents and work on common-sense legislation.”

GMO could help bring back the American chestnut. But should it?

Efforts to repair damaged ecosystems often come with hard choices. What kinds of intervention should be considered off limits? Here’s how that debate is playing out around one iconic species.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The American chestnut tree once sustained a way of life. Pioneers used the tall, straight, and fast-growing tree for fences, railroad ties, furniture, and anything else they wanted to last.

But beginning around 1904, a blight appeared on chestnut trees in the Bronx Zoo and spread rapidly. By the middle of the 20th century, the tree was essentially gone from its natural habitat.

Today a high-tech effort to restore the chestnut awaits federal regulatory approval. Scientists at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, New York, have created a genetically modified lineage of blight-tolerant chestnut trees.

If approved by federal agencies, it would be the first time a genetically modified organism would be intentionally set free into nature to reproduce. To some environmentalists, including two prominent American chestnut restoration activists in Massachusetts, this is a bridge too far.

In a world where ecosystems are under assault, “we are going to need every tool ... to make sure that we have resilient natural and human systems into the future,” says Doria Gordon, a senior scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund. “But,” she says, “we must be precautionary in how we deploy novel gene types into the environment.”

GMO could help bring back the American chestnut. But should it?

Edward Kashmer has fond memories of the American chestnut tree. As a child in the 1930s in western Pennsylvania, he and his playmates would make use of the small, sweet nuts produced by the trees.

“We couldn’t afford golf balls,” he says. “So we used chestnuts.”

Today, on the wall of his apartment in a retirement community in Jamesville, New York, is a regulator clock with an American chestnut cabinet that he says he carved in the 1990s. Mr. Kashmer, who says he owned a woodworking business for 20 years, points out the straightness and closeness of the wood’s grain. “What makes it perfect are the wormholes,” he says indicating the pinpoints bored by insects.

American chestnut trees were once plentiful from Maine to Georgia. But around 1904, a fungus clinging to a Japanese chestnut tree came to New York City. The spores spread on the wind, and within a few decades the American chestnut was all but wiped out. Most memories of mature, living trees reside only in the minds of people in their 80s and 90s.

But less than five miles away from Mr. Kashmer’s retirement community, scientists are working to restore this icon of America’s rustic past. Using a gene taken from wheat, scientists have successfully bred a lineage of American chestnut trees that tolerates the blight, and they hope to someday release it into the wild.

If approved by federal agencies, it would be the first time a genetically modified organism would be intentionally set free into nature to reproduce. To some environmentalists, including two prominent American chestnut restoration activists in Massachusetts, this is a bridge too far.

But to biologist William Powell, one of a duo who led the project, the addition of the wheat gene represents the smallest possible human intervention that could restore the species.

Standing not far from a grove of transgenic American chestnut saplings at a USDA-permitted research station in Syracuse, Dr. Powell, a professor at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF), hopes his project might help redeem the Empire State.

“New York is where the blight started,” he says. “And here is where I’m hoping it’ll stop.”

An ‘almost perfect tree’

Dr. Powell calls the American chestnut an “almost perfect tree.” It grows remarkably quickly, and, when planted near other trees, remarkably straight. The wood is easy to split and hard to rot, and from the Colonial era onward, Americans used it for fences, railroad ties, furniture, cradles, caskets, and anything else they wanted to last.

Chestnut trees, which once accounted for a fourth of all hardwood trees in some eastern forests, played a key role in the southern Appalachian economy. Free-range hogs would forage on the chestnuts. People could collect chestnuts to pay off grocery debts or trade them for shoes.

“It has so many values to it,” says Dr. Powell. “Almost everything eats chestnuts.”

That began to change in 1904, when chestnut trees at the Bronx Zoo started dying. The culprit was soon discovered to be Cryphonectria parasitica, a fungus native to Asia to which the American chestnut lacks any natural immunity.

The blight spread from New York, devastating eastern forests. By 1945, the year Mel Tormé and Bob Wells wrote about roasting chestnuts on an open fire, some 4 billion trees were gone.

In southern Appalachia, the blight destroyed a way of life. Striking during the Great Depression, it ended many people’s ability to live off the land, driving them into wage labor, often in the coal mines.

In a sense, both the trees and those who lived off of them were forced underground. Because microbes in the soil kill the fungus, many of the trees’ root systems survived, awaiting the day when the blight would no longer afflict them.

‘A little bit of an art’

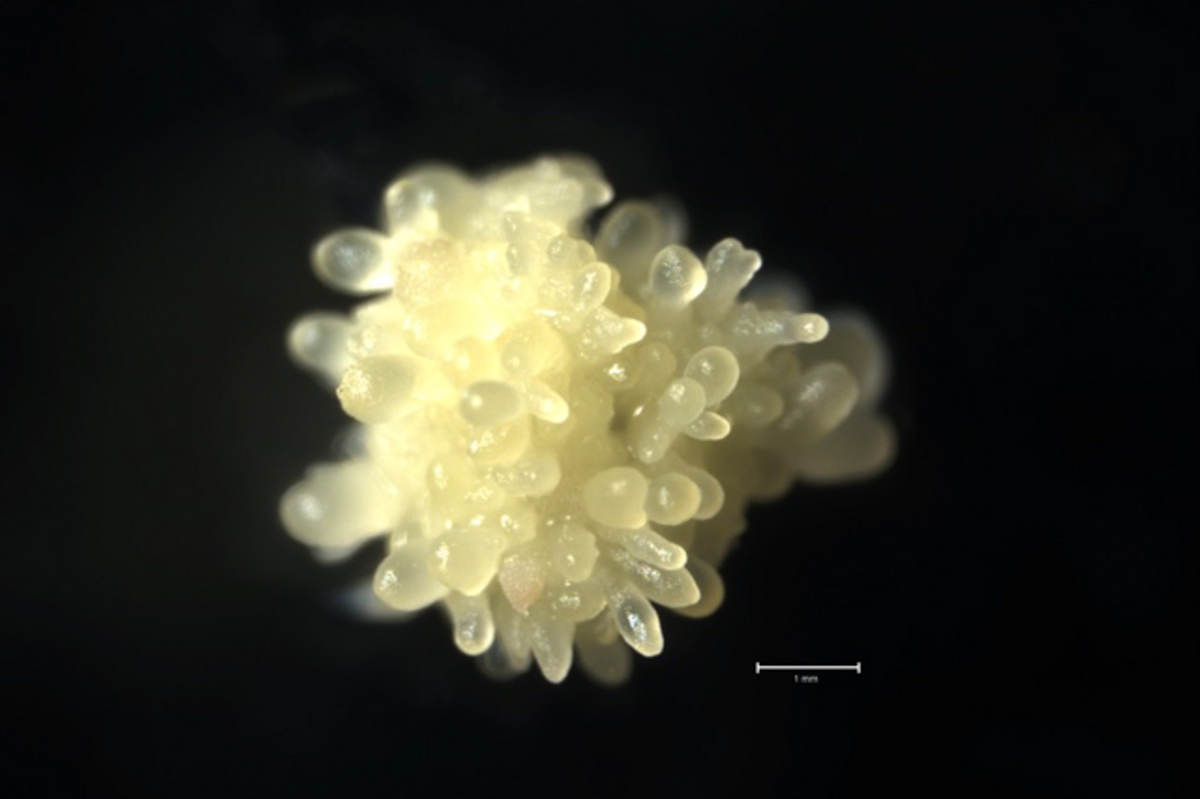

Through a microscope, the chestnut embryos at the lab for the American Chestnut Research & Restoration Project at SUNY ESF’s Illick Hall look like Israeli couscous: clusters of tiny pearl-like spheres. The embryos are the progenitors of Darling 58, chestnut trees whose genome Dr. Powell and his colleague, Charles Maynard, spent decades learning to tweak by adding a single gene from bread wheat.

At the lab, the trees are reproduced asexually, first by cracking open the nut and removing the embryos from the tip of the nut. These embryos are cleaned and then placed in a petri dish containing a nutrient-rich gel, where, if all goes well, they will multiply. Like growing plants, they are repotted into new petri dishes with new nutrients every few weeks as they grow and, eventually, sprout.

“We try to replicate what goes on inside the nut,” says Linda McGuigan, a researcher at the lab. “It’s a little bit of an art.”

When the transgenic trees are crossbred with American chestnuts, only about half of the plants will carry the gene. “Because it’s only on one chromosome, you would have half the [offspring] being transformed,” says Sara Fitzsimmons, a Penn State forest researcher and the director of Restoration for the American Chestnut Foundation, a nonprofit that sponsors the work at ESF.

At a greenhouse on the top floor, the leaves from transgenic chestnut saplings bear holes from hole-punchers used to collect leaf samples for testing. Those shown to have the gene will eventually go on for further testing, perhaps at the nearby research station where, enclosed in deer fencing, healthy American chestnut trees are growing in upstate New York again.

An ‘irreversible experiment’

The U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Environmental Protection Agency will need to sign off on the transgenic trees before they are released into the wild to reproduce, a process that could take up to three years. Dr. Powell says that he hopes to have approval by 2020.

But not all environmentalists champion the work. Today a group of activists opposed to genetically engineered trees released a white paper arguing that the unknown risks are far too great.

“The release of GE AC into forests would be a massive and irreversible experiment,” reads the paper, authored by Rachel Smolker of Biofuelwatch and Anne Petermann of the Global Justice Ecology Project.

The authors argue that the project at ESF represents a “Trojan Horse” that would open the gates for regulatory approval for genetically engineering trees for profit.

Doria Gordon, a senior scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund, agrees that caution is warranted when dealing with transgenic organisms. But she sees little evidence for the Trojan horse argument. “Those floodgates,” she says, “already were open with the extensive use of genetically modified crop species.”

In March, two board members of the Massachusetts and Rhode Island chapter of the American Chestnut Foundation, one of them the chapter president, resigned in protest over the national organization’s support for the technology.

“I’m not against genetic engineering,” says Lois Breault-Melican, who walked away from what would have been her fifth year as president. “That’s not the problem.”

To Ms. Breault-Melican, who has long promoted backcross breeding, which involves hybridizing the American chestnut with its more blight-tolerant Asian and European relatives, the transgenic trees are unnecessary.

“There’s no hurry to do this,” she says. “The backcross breeding program is working the way that it is supposed to work. When we joined, they realistically said to us that this will probably be a 100-year project.”

Dr. Powell insists that time is of the essence. While the trees’ roots can survive the blight, they cannot live forever. Those roots are crucial for a healthy restored population. “Every year that passes, we lose some genetic diversity,” he says. “We don’t want a monoculture.”

But it’s the trees longevity that also concerns Ms. Breault-Melican. “When they genetically engineer a corn plant, that plant will live for a year. But if you get a genetically engineered tree, well, American chestnut trees live up to 200 years.”

“It’s the unknown risks of the GE tree, especially down the road,” she says.

Ms. Fitzsimmons at Penn State says there are no guarantees that any single approach will prove fruitful. “You can’t say with certainty that this gene will, no matter what, restore the species.”

All you can say, she says, “is ‘Let’s take multiple approaches to create a more robust population that can persist into the future, that will give us a better chance.’”

At the American Chestnut Foundation, those approaches take the form of the three B’s: conventional breeding, biocontrol to keep the fungus away from the trees, and biotechnology.

Dr. Gordon at the Environmental Defense Fund agrees that a multipronged approach is needed in a world where forests are under assault from climate change, invasive species, and other environmental perils. “We are going to need every tool in the toolbox to make sure that we have resilient natural and human systems into the future.”

“But,” she says, “we must be precautionary in how we deploy novel gene types into the environment.”

“I am sympathetic to the individual reactions of people and their belief systems to these kinds of technologies,” she says. “We have to have a process for weighing those concerns against the other risks and benefits of deploying genotypes that may increase the resilience of our land and water systems.”

This article has been updated to clarify that the national and regional chapters of the American Chestnut Foundation are distinct entities. The regional chapter does not hold a position on genetic modification.

Patterns

In Notre Dame fire, a reminder of history’s complexity

History is complicated, and the history of Notre Dame is no different. That offers lessons at a moment when selective views of history are being used to fuel nationalism.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Ned Temko

The fire that struck Notre Dame in Paris has resurfaced an important lesson: that any nation’s history – any great building’s history – is far too complex to fit on a bumper sticker.

My first instinct upon hearing the news was to Google it. Instead, I reached for a 1950s book called “Notre Dame of Paris: The Biography of a Cathedral.” Its author brought home a truth that seems timely, as politicians draw on their countries’ past to fuel populism and nationalism.

The “history” invoked in movements like Brexit, “illiberal democracy” in Poland, Vladimir Putin’s rise in Russia, or Donald Trump’s call to “Make America Great Again” tends to airbrush out misjudgments and injustices. As debate swirls over how to restore Notre Dame, the book draws a great arc that shows that the cathedral is the product of multiple fixes and changes over the centuries.

We risk forgetting that when human stories are presented as simple matters of triumph versus threat, they are almost certainly a lot more complicated. The allure of populists’ pseudo-history grows as we lose the habit of taking the time to delve deeper.

In Notre Dame fire, a reminder of history’s complexity

When fire struck Paris’s Notre Dame cathedral last week, my first instinct, shared no doubt with millions across the globe, was to Google it. Yet then I reached for a yellowed edition of a 1950s book called “Notre Dame of Paris: The Biography of a Cathedral.”

The catalyst was less intellectual than personal: its author was Allan Temko, my late uncle. But his 300-page tour of how the cathedral, and Paris and France around it, came to be, brought home a truth that seems timely nowadays, as politicians worldwide draw on their countries’ past to fuel a mix of populism and nationalism. It is that any nation’s history – any great building’s history – is far too complex, too nuanced and too rich to fit on a bumper sticker.

The same might be said of my uncle. He was best known as the Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic of the San Francisco Chronicle. But “Notre Dame of Paris” was a product of his years as a would-be novelist. I always think of him as the on-again, off-again friend of fellow Columbia student Jack Kerouac, to whom he loaned his typewriter when Kerouac was working on “On The Road,” and in whose books he appears under a bizarre carousel of pseudonyms: Roland Major and, much less imaginatively, Irving Minko and Allen Minko.

The “history” invoked in movements like Brexit in Britain, “illiberal democracy” in Poland or Hungary, Vladimir Putin’s rise in Russia, or Donald Trump’s clarion call to “Make America Great Again” has little place for nuance. In drawing a picture of past glories and triumphs, it tends to airbrush out setbacks or misjudgments, not to mention the suffering, injustices, or other human frailties invariably part of history as it’s actually lived. Even the history of a cathedral.

Centuries in the making

In exploring Notre Dame’s place in the hearts of the French, and the millions of others who visit it each year, my uncle’s book draws a great arc stretching from the earliest settlement of the Île de La Cité in the middle of the River Seine, long before there was a Paris, to the years after the Second World War. He traces the vision and design, the role of the limestone-quarriers and tree-fellers, stonemasons, and other artisans, that made possible the greatest Gothic cathedral on earth. And he revels in its beauty, describing how it strikes the eye from the Left Bank of the Seine, the Right Bank, or the river itself.

But that’s just part of the story. There is Maurice de Sully, the son of peasants from the Loire who became Bishop of Paris and conceived the idea of the cathedral. The interlocking role of the Roman Catholic Church and the monarchy during the stretch of nearly a century in which the cathedral was built and France emerged as a nation. The tumults of war and crusade and inquisition. The aftermath of the French Revolution, when the crowds toppled and decapitated 28 stone statues of the ancient kings of Judah – wrongly believing them to be figures of French kings. And the fact that Notre Dame, in its current form, is the product of multiple fixes and changes over the centuries, and of long periods of deterioration and willful neglect.

In fact, its oaken roof has twice before caught fire, though the flames were spotted and put out. The emblematic image of last week’s blaze was of the enormous spire, or flèche, toppling as the roof gave way. But it, too, was a replacement, after the revolution. And my uncle’s eye for architectural detail leaves little doubt that once the fire roared out of control, its fate was sealed: It weighed one million pounds.

None of this is to suggest that only by immersing ourselves in volumes of history can we escape the allure of populists’ pseudo-history. In fact, the Wikipedia entry on Notre Dame is wonderfully detailed. Yet I do think many of us have lost the habit of taking the time to delve deeper: even to go beyond a few Googled news paragraphs to the Wikipedia site.

In the process, we risk losing the understanding that when human stories are presented as simple matters of black-and-white, triumph versus threat, they are almost certainly a lot more complicated than that.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Taking ‘old age’ out of its old box

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The famed British actress Glenda Jackson is back on stage, an amazing encore for someone who first won accolades on film and stage decades ago. Should such achievements at what is considered “advanced” ages be celebrated? Or are they instead a new norm?

Without all the stereotypes about aging, the answers to both questions would be yes. Yet in a culture that still makes jokes about older people and imposes notions of impairment on them, examples of mastery over aging are still needed, especially in societies with a rapidly rising older demographic.

In recent decades, a phrase like “65 is the new 55” is updated to higher numbers. But why put a number on it at all? Whether commanding a theater stage or working in an office, expressing one’s talents and abilities can be satisfying at any age. The “essential you” does not have a sell-by date.

Taking ‘old age’ out of its old box

The famed British actress Glenda Jackson is treading the boards right now as King Lear, reciting from memory all 747 of the character’s lines during a 3-1/2 hour performance, eight shows a week. It’s an amazing encore for someone who first won accolades on film and stage decades ago and then left for a much different career as an elected politician in the House of Commons.

Now back on Broadway she’s among the few actresses to take on one of Shakespeare’s most demanding male roles. Asked about how “the age thing” affects her performance she responds: “The essential you is on the inside, it stays the same.”

In London, Maggie Smith, Ms. Jackson’s senior by a couple of years, is starring in “A German Life,” the disturbing real-life confessions of Brunhilde Pomsel, secretary to Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels. The “Downton Abbey” favorite is the whole show in a 100-minute, one-woman play. As expected, her performance has won over critics.

Should such achievements at what is considered “advanced” ages be celebrated? Or are they instead a new norm? Without all the stereotypes about aging, the answers to both questions would be yes. Yet in a culture that still makes jokes about older people and imposes notions of impairment on them, examples of mastery over aging are still needed, especially in societies with a rapidly rising older demographic.

Worldwide, the percentage of people over 60 will nearly double between 2015 and 2050, the World Health Organization reports. By next year, more people will be over 60 than under 5. The agency also notes that the experience of chronological age varies widely: Some 80-year-olds have physical and mental capacities similar to many 20-year-olds. Some athletes in their 80s and older run marathons.

Such shattering of stereotypes is essential to the debate about whether older people will be a boon or a burden to society. The U.S. government just reported that Medicare and Social Security, two key programs serving older Americans, face funding shortfalls in the near future.

One solution would be to encourage Americans to work longer before taking their benefits. That seems to be happening: More than 20% of Americans over 65 are working or are looking for work, a 57-year high; that figure was 10% as recently as 1985. More than three-quarters of older Americans (77%) say they are in good or excellent health with no limitations on the kind of work that they can do, reports the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Some older Americans, of course, can no longer work. Some need to keep working to have enough income. Others enjoy the mental stimulation, the satisfaction of accomplishing goals, and the camaraderie of the workplace.

In recent decades, a phrase like “65 is the new 55” is updated to higher numbers. But why put a number on it at all? Whether commanding a theater stage or working in an office, expressing one’s talents and abilities can be satisfying at any age. The "essential you" does not have a sell-by date.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

In the face of violence, build on a model of love

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By John Tyler

When today’s contributor was robbed and assaulted, the idea that God is all-powerful Love itself prompted him to forgive rather than to react in kind. The situation turned around completely, and his wallet was returned to him right then and there.

In the face of violence, build on a model of love

When someone hits you, do you hit back? For thousands of years this has posed a problem. Over 3,000 years ago, in Moses’ time, they devised two different solutions. One was to hit back, but not harder than you were hit – “an eye for an eye” – which was a great step of progress in a day when vengeance was often hugely disproportionate. The other is as radically innovative today as it was then: “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself” (Leviticus 19:18).

This second solution is based on an entirely different picture than action-reaction: only action – loving. It’s based on the premise that love actually expresses great power. For the apostle John in the Bible’s New Testament, Love was literally a name for the All-power, God (see I John 4:16).

The Love we’re talking about here is not only incredibly powerful, it’s the only legitimate power, as the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, has pointed out. In “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896” she said of love: “I am in awe before it. Over what worlds on worlds it hath range and is sovereign! the underived, the incomparable, the infinite All of good, the alone God, is Love” (pp. 249-250).

Understanding just how powerful divine Love is can defuse reactions and bring healing. I had a chance to experience this one day when I was giving away some materials in a parking lot in the “gangland” part of our town. A young man asked for something, and when I bent over to find it, he picked my wallet out of my back pocket. I felt it and whirled around. He punched me in the face. A crowd of other men started taking his side.

Earlier that day, I had been thinking about a favorite line of mine in the Bible: “I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever” (Psalms 23:6). In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mrs. Eddy explains that as dwelling in the consciousness of divine Love (see p. 578).

What came to me was that I needed to change my picture of these gang members – to see them as children of divine Love, the spiritual expressions of God’s goodness – and to be conscious of the power and presence of God’s love. And faced with violence in that parking lot, I also knew I had to forgive, an essential part of loving. To me, forgiveness is the putting aside of my judgments about others to listen for Love’s guidance and feel the presence of Love always here. No one can ever be outside God’s love.

With all this in mind I was able to see through the facade of the tough guy, the self-centered, the uncaring; I glimpsed the nature of Love as these men’s own, and only real, nature. At that point, I found it easy to forgive them, to feel pure, spiritual love for them as my brothers in God. By getting my ego out of the way, I could mentally acknowledge God’s love for His children.

Then the leader stepped forward and, despite grumbling on the part of some of the others with him, returned the wallet to me and apologized.

Let’s face it: We live in a world in which violence sometimes seems inevitable. It can be easy to be drawn into the action-reaction model. But divine Love is always in action. This Love is the divine Parent of all. Surely the effect of that infinitely loving Parent could not be anything other than unselfish, good, merciful, just, and so on. That Love is the essence of each one of us, despite outward appearances.

Each of us can contribute to healing violence by starting in our own consciousness, by letting our relation to God, divine Love – rather than hatred or revenge – animate us, by striving to love God with all our soul, all our mind, all our strength (see Luke 10:27). Then we can perceive and love the wholly spiritual nature in each of God’s children.

This is not about attempting to change others; it’s divine Love transforming us all from within. Building on this basis, we’re learning to love, to value everyone’s true nature as our own nature is transformed in the process. We begin to see that hate and vengeance are neither advisable nor inevitable. They cannot destroy Love, because infinite Love is the only real power.

Adapted from an article published in the Aug. 9, 2010, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

In remembrance

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Tomorrow, we’ll take a look at one of the more important facts lost in the partisan sideshow about the Mueller report: Russia allegedly hacked a Florida county’s election network in 2016. Staff writer Christa Case Bryant looks at what lessons there are to learn – and whether they are being heeded.