- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Will countries answer the ‘Christchurch Call’?

Two months to the day after a gunman killed 51 Muslim worshippers in New Zealand, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern comes to Paris to launch what she is presenting as the “Christchurch Call.”

There was something particularly horrific about the March massacre: The alleged murderer livestreamed his atrocity on the internet so it would go viral. The Christchurch Call, named for the city where the massacre was perpetrated, is aimed at eliminating such violent extremist content from spreading online.

Ms. Ardern is hoping to persuade governments to pass laws banning objectionable material, and she wants the big tech companies – such as Facebook, Twitter, and Google – to tweak their algorithms to direct users away from extremist and terrorist material.

In some parts of the world, that rings free speech alarm bells, and the United States administration, for example, is not expected to sign on. But Ms. Ardern’s authority and credibility on this issue are grounded in her displays of good faith.

She seized the world’s attention, and won widespread respect, with the way she expressed her nation’s grief after the massacre and consoled its victims and their families. Her humanity gave extra force to her condemnation of the atrocity.

Now, she is well placed to take the lead on the delicate issue of internet restrictions precisely because of her reputation for sincerity.

The fact that the massacre happened in New Zealand, she said in a video explaining the Christchurch Call, means “we have a reluctant duty of care” in the matter, “a responsibility that we have now found ourselves holding.”

Now for our five stories of the day, including the Monitor’s first foray into stop motion animation.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘Crisis of masculinity’: How opioid epidemic hits men harder

Traditional ideals of masculinity may be making men more vulnerable to the sort of thinking that leads to fatal drug overdoses. Officials in Vancouver are building their prevention plans around that theory.

Both men and women across North America are dying from fentanyl – a synthetic opioid roughly 50 to 100 times more toxic than morphine that’s entered the drug supply. But when the mortality data has been crunched, the overwhelming number of victims are men, most in the prime of their lives. With fentanyl in the supply, men in the United States have succumbed at a much greater rate than women starting in 2013. In Canada, the disparity is similar.

Now doctors, officials, and social workers in Vancouver are questioning whether the drug crisis is also an overlooked crisis of masculinity. Men take bigger risks with drug use and feel that they can handle their intake. Amid social and economic changes, many men have lost their traditional moorings – making them even more vulnerable in this high-stakes era for drug consumption.

“There seems to be something going on here with men, where some parts of masculinity seem to produce more substance use and more risk of overdose deaths,” says Chris Van Veen, director of strategic initiatives and public health planning at Vancouver Coastal Health. “More men seem to be using these poisoned drugs.”

‘Crisis of masculinity’: How opioid epidemic hits men harder

On a recent morning in the Downtown Eastside, a man in a parking lot picks up a syringe from the ground. Hoping that it contains some sort of substance, he puts it to his arm. But it is empty. He throws it back down.

It is just one scene in this 10-block Vancouver neighborhood, one of North America’s most concentrated areas of drug injection. And it is increasingly lethal as the opioid fentanyl becomes more common; overdose deaths have skyrocketed in this province by 651% between 2009 and 2018.

But Dean Wilson, who began using heroin in his teens and is now an activist whose focus is on establishing a legal, safe supply, says that the victim tally is mounting from those outside the Downtown Eastside, who neither have the tolerance for the drugs nor the access to have them tested.

“We’ve realized that a number of the men dying down here aren’t from here,” he says. “They are construction workers; they’ve got jobs. They are anywhere between 20 and say 35, 40 years old. They come down here on Friday night, they cash their checks, they’re having a beer, they grab a paper of down [heroin] to go home with, they snort it at home. They go to bed. They don’t wake up.”

In fact, health officials are now planning intervention specifically for those in the building trades. And as overdose deaths among men now far outstrip those among women, many doctors, officials, and social workers question whether the drug crisis is also an overlooked crisis of masculinity.

Men take bigger risks with drug use and feel that they can handle their intake. Amid social and economic changes, many men have lost their traditional moorings – making them even more vulnerable in this high-stakes era for drug consumption.

“We’ve thought long and hard about how to create services that keep women safe and that address their unique health care needs. But there seems to be something going on here with men, where some parts of masculinity seem to produce more substance use and more risk of overdose deaths. More men seem to be using these poisoned drugs,” says Chris Van Veen, director of strategic initiatives and public health planning at Vancouver Coastal Health.

Men at risk

Both men and women across North America are dying from fentanyl – a synthetic opioid roughly 50 to 100 times more toxic than morphine. But when the mortality data has been crunched, the overwhelming number of victims are men, most in the prime of their lives.

Men have always displayed riskier behaviors with substance use. But with fentanyl, men in the U.S. have succumbed at a much greater rate than women starting in 2013, says Merianne Rose Spencer, a statistician at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2011 and 2012, overdose rates between the genders were similar.

Traci Green, associate director of Boston Medical Center’s Injury Prevention Center, says some of it might boil down to less interface with the health system for men. “Women in general across health conditions tend to seek care more, but they’re also surveyed more. ... Women have more health conditions that bring them to a health professional, and each of those is an opportunity to check in,” Dr. Green says.

A lack of opportunities for men, when it comes to general wellness, is what drove Paul Gross, a family doctor in Vancouver, to co-found the “Dudes Club,” a meet-up for men, many indigenous, who have a host of hardships from addiction, to poverty, to homelessness – and who were looking for a place to talk about it. Dr. Gross says that drug use has always been a part of their reality but fentanyl has hit them hard – at one point in 2017 they estimated that they had lost 25% of their members to overdose.

Now the group is creating “squads” to go out to Oppenheimer Park, in the heart of the Downtown Eastside, to try to bring in new members seeking brotherhood. “That relational piece I think is missing in the opioid response,” Dr. Gross says. “There is a whole lot of [anti-overdose drug] Narcan and a whole lot of harm reduction, a whole lot of safe injection sites. But not a lot of engaging people, and connecting them to healthy relationships.”

The most deaths in British Columbia happen in the Downtown Eastside, says Mr. Van Veen. But in Vancouver, half occur outside it. And many of the victims aren’t necessarily addicted to opioids.

In a forthcoming study by Vancouver Coastal Health, just 39% of those who have died around the greater Vancouver and Central Coast region had documented daily opioid use, suggesting that many deaths occurred among those who were not addicted. In a British Columbia Coroners Service report, nearly half of those who overdosed fatally in 2016 and 2017 had jobs. Among those, 55% worked in the trade and transport industries, where workplace injuries are common.

Now Vancouver Coastal Health plans to target those in the building trades in a pilot project, bringing to job sites safety talks about treatment options or teaching workers how to use Naloxone anti-overdose kits. So far employers have been open, says Mr. Van Veen, because of the magnitude of the problem. “This crisis is so widespread in this province now that everybody knows someone or knows someone who knows someone who’s died or had an overdose incident or lost a loved one,” he says.

Putting a gender lens on the issue

Alongside this targeted intervention for men, experts are looking deeper to some of the sociology driving men’s death rates – whether it’s risk-taking or overconfidence that they can handle their drugs.

“Normally if we see disparate statistics leaning the other way, we say there’s a gender dimension to this, and we tend not to do that if it’s men,” says Michael Kaufman, an expert on manhood who wrote “The Time Has Come.”

But he says this is a gender issue that demands dominant ideals of manhood be understood. “One is that from a pretty early age, men are trained not to ask for help. We have these strong images that a real man can ‘go it alone.’ He can look after himself.”

That could be behind statistics in a British Columbia Coroners report in January that show 62% of fatal overdoses of illegally taken drugs occurred in private residences. Across Canada, in the latest federal statistics, 75% of accidental apparent opioid-related deaths occurred among men.

Mr. Kaufman also sees a powerful intersection between the opioid crisis and the economic and social underpinnings in which the traditional “blue collar” worker no longer enjoys the status of the dependable breadwinner as he did for the last century. “What you are seeing is a lack of sense of possibility, a lack of sense of worth,” he says. “What that means is that your own capacity for resilience is reduced.”

Dan Bilsker, a Vancouver psychotherapist who focuses on men’s health, has urged policymakers to put a gender lens on the issue – which in turn can break down barriers.

“The caricature was that these fentanyl overdose deaths were taking place in alleys in the Downtown Eastside. But most of them are taking place in people’s homes,” he says. “You see a guy who’s been working really hard at a dangerous job and got severely injured, and it changes your whole reaction to that situation.”

Therein may lie a solution, he says. “It brings out the tragedy and the loss of it. You can empathize more powerfully. You relate to the person you see.”

Video

Why fixing a broken Congress matters

People often say Congress is broken; maybe it’s worn out, too. We can easily forget that Congress is more than elected officials; it is also a workplace for staffers, serving members in all sorts of ways. They need public support and resources to keep Congress running. Our video explores this issue, with a little help from modeling clay.

We often blame partisan politics for dysfunction in Congress. But that’s not the whole story.

Despite public perception that the legislature has too many staff and employees are overpaid, cuts to staff and budget over the years have actually hollowed out Congress’ capacity to do its work. A study by the nonprofit Congressional Management Foundation shows only 6% of senior congressional staff think members have enough time and resources to work on legislation.

Long days and low pay have also made Congress a less than ideal workplace, especially for the nation’s best and brightest. Why deal with the grind on Capitol Hill when lobbying firms and the private sector offer better opportunities?

Like any business, Congress needs a well-supported staff to do its job, which requires a careful balance of crafting smart laws, responding to constituents, and keeping a check on executive power. “[A]t the end of the day, if you are a voter and you care about reducing the power of special interests, and you care about making sure that Congress has the ability to assert itself against the executive branch, you want a stronger, better-resourced Congress,” says Molly Reynolds at the Brookings Institution. –Jessica Mendoza

Why Congress should spend more – on itself

The Explainer

Amid concerns about 2020, a primer on Russian election interference

Public faith in the integrity of elections is critical to any democracy. With new details from the Mueller report about Russia’s interference in the U.S. in 2016, here’s an overview of what happened – and whether it might happen again.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The recent publication of the Mueller report provided more details about the extent of Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election – and is creating a new sense of urgency around the question of what the U.S. is doing to prevent another such attack. Last week, President Donald Trump said that he did not broach the topic on a lengthy call with Russian President Vladimir Putin, telling reporters “we didn’t discuss it.”

But Director of National Security Dan Coats, in a briefing to the Senate intelligence committee in January, warned that America’s adversaries “probably already are looking to the 2020 US elections,” and that they “almost certainly will use online influence operations to try to weaken democratic institutions, undermine US alliances and partnerships, and shape policy outcomes in the United States and elsewhere.”

The Trump administration in early 2018 established a designated information-sharing center for election infrastructure, and Congress approved $380 million to be disbursed to states for election security. But most cyber experts agree that U.S. election infrastructure remains vulnerable. Here’s a brief overview of what we know about what happened the last time around.

Amid concerns about 2020, a primer on Russian election interference

The recent publication of the Mueller report provided more details about the extent of Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election, and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis revealed today after meeting with the FBI that the Russians hacked into two counties' supervisor of elections networks. Such revelations are creating a new sense of urgency around the question of what the United States is doing to prevent another such attack. President Donald Trump said he did not broach the topic on a lengthy call last week with Russian President Vladimir Putin, telling reporters “we didn’t discuss it.”

But U.S. intelligence officials have repeatedly warned that they expect Russia to attempt to meddle in the 2020 election. And in a meeting with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov today in Sochi, Russia, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said he made clear that “interference in American elections is unacceptable. If the Russians were to engage in that in 2020, it would put our relationship in an even worse place than it has been.”

Here’s a brief overview of what we know about what happened the last time around.

How did Russia influence Americans through social media?

The Internet Research Agency (IRA), a Kremlin-linked organization in St. Petersburg, Russia, developed Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook accounts to spread disinformation. This activity began as early as 2014, and by early to mid-2016 the campaign was actively supporting Donald Trump and disparaging Hillary Clinton. By the time the elections took place, the IRA was part of a Russian project with a monthly budget of more than 73 million rubles ($1.25 million) and had the potential to influence millions of Americans.

By the time Facebook and Twitter representatives testified before Congress the following year, the IRA had reached 126 million people through 470 Facebook accounts and 1.4 million through 3,814 Twitter accounts. The IRA also spent about $100,000 putting ads in the news feeds of Facebook users, featuring assertions such as “I say no to Hillary Clinton / I say no to manipulation” and “Donald wants to defeat terrorism ... Hillary wants to sponsor it.”

What was its goal?

The IRA’s operations aimed to “sow discord in the U.S. political system,” in the words of the Mueller report. Some of the most popular accounts included “United Muslims of America” (300,000-plus participants) and “Secured Borders” (130,000-plus participants). IRA-controlled posts touched on flashpoints such as immigration, race, and religion, all designed to exacerbate political polarization. They also sought to sow doubts about American democracy, such as by promoting allegations of voter fraud by the Democratic Party.

This type of political interference has been used by Moscow since Soviet times. John Sipher, a retired CIA agent who served in Moscow and ran the agency’s Russia operations, describes it as “the art of having your enemy think what you want him to think.” But the digital age provides a much bigger platform for such political warfare, which can be more subtle, believable, and far-reaching than in the past.

What did the Russians hack?

In early 2016, as Russia was stepping up its support for Mr. Trump, it opened a second front: hacking political organizations and publishing sensitive documents.

The GRU, a Russian military intelligence unit, hacked the Clinton campaign’s email accounts and gained access to two national organizations of the Democratic Party, stealing hundreds of thousands of documents. The GRU then published these materials through WikiLeaks and fake online personas, “DCLeaks” and “Guccifer 2.0.”

On two occasions, the timing of these releases appeared favorable to Mr. Trump. In late July, amid a controversy over Mrs. Clinton’s use of a private email server while she was serving as secretary of state, Mr. Trump said, “Russia, if you’re listening, I hope you’re able to find the 30,000 emails that are missing.” About five hours later, the GRU “targeted for the first time Clinton’s personal office,” according to the Mueller report.

Then in October, just an hour after a damaging video surfaced in which Mr. Trump had bragged about groping and kissing women without their consent, WikiLeaks released a second trove of emails stolen months earlier from Clinton campaign manager John Podesta.

Russia also targeted at least 18 states’ electoral systems, with others reporting malicious activity. The GRU gained access to an Illinois database with millions of registered voters, and also breached at least two Florida county government’s computer networks. Though there is no evidence that Russia’s hacking changed the vote tally or manipulated voter registration data, such malicious activity has raised concerns that in the future, foreign actors could tamper with voter registration records to exclude certain voters or groups of voters on Election Day.

How has Washington responded?

In February 2018, a grand jury in Washington indicted 13 Russian nationals and three Russian entities “for conspiracy to defraud the United States.” Among them was Putin ally Yevgeniy Viktorovich Prigozhin, whose companies had funded the IRA troll factory.

Several months later, the grand jury issued a second indictment charging a dozen members of the GRU with 11 criminal counts, including “conspiracy to commit an offense against the United States by attempting to hack into the computers of state boards of elections, secretaries of state, and US companies that supplied software and other technology related to the administration of elections.”

To help states defend against such threats, the Trump administration in early 2018 established a designated information-sharing center for election infrastructure. Around the same time, Congress approved $380 million to be disbursed to states for election security.

Is the U.S. ready for 2020 elections?

Director of National Security Dan Coats, in a briefing to the Senate intelligence committee in January, warned that America’s adversaries “probably already are looking to the 2020 US elections as an opportunity to advance their interests. More broadly,” he added, “US adversaries and strategic competitors almost certainly will use online influence operations to try to weaken democratic institutions, undermine US alliances and partnerships, and shape policy outcomes in the United States and elsewhere.”

While Mr. Coats has indicated that the intelligence community is doing everything it can to prevent the success of such efforts, and many states have substantially stepped up their defenses, most cyber experts agree that U.S. election infrastructure remains vulnerable.

So 1 million species are at risk of extinction. Now what?

The bleak environmental reports just keep coming. The latest declares that humans pose a threat to a vast portion of Earth’s plants and animals. But what can the public do with that kind of information?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Last week, newspapers across the United States were plastered with a dire prognosis for Earth’s plants and animals. The United Nations’ first biodiversity assessment declared that humans were pushing 1 million species toward extinction. But beyond headlines, whether such a landmark report on biodiversity will leave a lasting mark on society or not remains to be seen. And what happens next may matter more than the report itself.

“The power of the report will only be known when we see the reflection of the report in action,” says Keith Tidball, an ecological anthropologist at Cornell University.

The U.N. report is the most extensive and comprehensive assessment of global biodiversity ever conducted, but some are skeptical that a single report could trigger a widespread shift in perspective on biodiversity and extinction by itself. Such reports offer a sketch of the ecological stakes. But it’s up to science communicators to fill in the lines with the context of what that means for humanity.

As Thomas Lovejoy, the so-called godfather of biodiversity, puts it: “Most people are blissfully unaware of what biodiversity does for them.”

So 1 million species are at risk of extinction. Now what?

The statistic is staggering. One million animal and plant species are at risk of extinction, many within decades, if humans don’t act to save them, according to the executive summary of a United Nations global assessment of biodiversity released last week.

One million species.

To put that into context, although scientists aren’t sure exactly how many species currently live on the planet, estimates range from 2 million to 12 million. Researchers have formally described almost 2 million species so far.

The U.N. report puts a number to something many ecologists have been saying for years: that we’re in the midst of the Earth’s sixth mass extinction – and it’s largely due to human activities. Corroborating papers continue to pile up. Just today, Dutch researchers published a study implicating overhunting in the steep decline of tropical forest mammal populations.

The report, put out by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), points to five main drivers of modern extinction. Those factors are, in diminishing order of magnitude, changes in land and sea use, hunting and fishing pressures, climate change, pollution, and invasive species.

Newspapers across the United States were plastered with this gloomy news last week. But whether such a landmark report on biodiversity will leave a lasting mark on society or not remains to be seen. And what happens next may matter more than the report itself.

“The power of the report will only be known when we see the reflection of the report in action,” says Keith Tidball, an ecological anthropologist at Cornell University.

The rock and the lightbulb

Many landmark environmental reports in the past have ended up as fodder for policymakers already predisposed to care about their specific issue, rather than engaging additional minds on the topic.

These reports can serve as either a rock or a lightbulb, says Robert Stavins, a professor of energy and economic development and director of the Harvard Project on Climate Agreements at Harvard University. In political processes, scientific analysis can either illuminate a topic for policymakers to discuss how to proceed, or it can become ammunition for those who are already predisposed to a particular position that is supported by the analysis.

Take the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports, for example. Those analyses have often been used as political rocks – albeit sometimes effective ones – rather than as tools to engage discussion.

There is a place for “rocks,” says Professor Stavins. “You can’t win a battle without ammunition.” But, he says, reports that end up as ammunition don’t end up changing a lot of minds.

The authors of the new U.N. biodiversity report call for “transformative change” in societal paradigms and values in order to halt the mass extinction. But that might take a lightbulb moment rather than a rock.

The new U.N. report was put together by hundreds of scientists from 50 countries. Together, they spent three years systematically combing through data and thousands of scientific reports, and probing government, indigenous, and local knowledge sources, too. They looked through data from the past five decades to assess how biodiversity and habitats have changed, and the relationship between economic development and changes in nature.

Some people have quibbled with the 1 million figure. The study authors arrived at that global estimate in part by extrapolating the rate of extinction previously calculated by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Researchers with the IUCN had examined a much smaller number of species.

A recipe for action

The U.N. report is the most extensive and comprehensive assessment of global biodiversity ever conducted, but some are skeptical that a single report could trigger a widespread shift in perspective on biodiversity and extinction.

It might be one piece of what helps shift perspectives on biodiversity and extinction, says Kurk Dorsey, an environmental historian at the University of New Hampshire. But it probably isn’t enough on its own.

The recipe for action on environmental issues typically requires three ingredients, Professor Dorsey says. The U.N. report offers one: the science. But there generally needs to be a sentimental or sympathetic cause that people can get behind as well. Economic losses and payoffs can also be deal breakers – or makers.

That combination came together when researchers discovered a hole in the ozone layer in the 1980s. The ozone layer protects the Earth from harmful solar radiation, which would affect humans and all other life on the planet – the sympathetic cause. Scientists linked the damage to the emissions of certain industrial chemicals that wouldn’t be too costly to phase out. And policymakers quickly came together to ratify the international treaty known as the Montreal Protocol to ban those substances. Today, the ozone hole is healing.

In the case of the ozone layer, the economic trade-offs were minimal. Issues like biodiversity loss and climate change, however, can come with much higher costs.

There is an economic argument for biodiversity, says Thomas Lovejoy, a professor in the department of environmental science and policy at George Mason University and a senior fellow at the United Nations Foundation. Many plants and animals are vital to life as we know it. They underpin modern medicines and technologies, and intact ecosystems support clean drinking water systems and clean air.

“Most people are blissfully unaware of what biodiversity does for them,” he says.

But the wonder of nature can also be a powerful force, adds Dr. Lovejoy, who has been called the “godfather of biodiversity” for coining the term. To explain, he tells a story of “craniacs,” people who flocked to Nebraska to see sandhill cranes as they stopped in the Platte River Valley on their migration paths. When the river habitat became less appealing for the birds, craniacs and others who adored the birds advocated for projects to maintain its hospitality for the cranes.

Sparking compassion

“Numbers numb but stories engage,” says Ed Maibach, director of George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communication. Although the U.N. biodiversity report provides global context to extinction, Dr. Maibach’s research suggests that stories about specific threatened species and their plight will more likely motivate people to action.

Stories lend mental pictures to associate with an issue, Dr. Maibach explains. For example, if you think about climate change, you probably automatically visualize a polar bear stranded on a chunk of ice. An image or story like that is more likely to evoke empathy.

It may go beyond feeling compassion for another being, though, suggests Dr. Tidball. He points to retired Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson’s hypothesis that humans innately seek out connections with nature and other life. Dr. Tidball says that although we may now hold mental images of ourselves as separate from nature, we still crave that affinity with nature, that reconnection to being part of the biosphere. He suggests that spending time in nature may also engage more people with biodiversity.

Whether society changes course in response to scientific reports of the sixth mass extinction or not may come down to a philosophical issue, says Professor Dorsey.

“It really gets down to the question of what is the role of humanity on the planet,” he says.

10 fantastic May books to whisk you away

Now, here are two books that our reviewers picked out as being among the best of recently published fiction and nonfiction.

One is “The Satapur Moonstone,” by Sujata Massey. It’s a novel about Perveen Mistry, a rare woman lawyer in 1920s India, who travels to a remote princely state to resolve a dispute about the young maharajah’s schooling between his mother and his grandmother. The death of the first in line to the throne was thought to be a curse, but the dauntless Perveen unravels a nasty plot. There’s a romance brewing, too.

The other choice is “Stony the Road,” by Henry Louis Gates Jr. Reconstruction saw a brief flowering of African American empowerment after the Civil War. But as Gates recounts, the ideals of Reconstruction were soon extinguished by Jim Crow, a system of oppression designed to preserve the South’s status quo. Gates explores how Jim Crow propaganda still informs public discourse today.

-

By Staff

10 fantastic May books to whisk you away

There’s something for everyone in this month’s book recommendations, whether you’re hungry for tales of political movers and shakers or would rather wander through dreamy European cityscapes.

1. The Parisian, by Isabella Hammad

Isabella Hammad’s first novel is not a page turner. That’s not an insult. With historical sweep and sentences of startling beauty, she has written the story of a displaced dreamer, a young Palestinian whose merchant father sends him to France to study in 1914. Patient readers will be rewarded with a new voice worth listening to.

2. The Guest Book, by Sarah Blake

The Milton family is forced to address the lies buried under three generations of family lore. Sarah Blake spins a fascinating epic that touches on privilege and ambition, racism and grief, revealing as much about America’s identity as it does the Miltons’.

3. The Flatshare, by Beth O’Leary

This quirky romantic comedy has surprising depth. London book editor Tiffy is mending from an emotionally abusive relationship; devoted night nurse Leon is struggling with his own issues. They become flatmates who correspond only through sticky notes, until they bumble into each other. Colorful storylines, generous-hearted characters, and British banter make this a refreshing novel.

4. The Satapur Moonstone, by Sujata Massey

Perveen Mistry, a rare woman lawyer in 1920s India, travels to a remote princely state to resolve a dispute between a grandmother and mother about the young maharajah’s schooling. The death of the first in line to the throne was thought to be a curse, but the dauntless Perveen unravels a nasty plot. There’s a romance brewing, too.

5. Walking on the Ceiling, by Aysegül Savas

Aysegül Savas’ debut novel is a kaleidoscope of exquisite memories. Nunu, a young woman from Istanbul, moves to Paris after her mother’s death. Longing for connection, she meets a kindred spirit in a famous older gentleman British author. Their intellectual repartee as they meander through the City of Lights, visiting cafes, is engrossing.

6. Stony the Road, by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Reconstruction saw a brief flowering of African American empowerment after the Civil War. But as Henry Louis Gates Jr. recounts, the ideals of Reconstruction were soon extinguished by Jim Crow, a system of oppression designed to preserve the South’s status quo. Gates explores how the propaganda of Jim Crow informs public discourse today.

7. A Good American Family, by David Maraniss

David Maraniss’ insightful, bighearted book centers around his father’s 1952 appearance before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. The author, contrasting his father’s story with that of committee chairman John Stephens Wood, a onetime Ku Klux Klan member, compels us to consider how “American” was defined.

8. Our Man, by George Packer

George Packer’s biography of diplomat Richard Holbrooke, best known for brokering the Dayton Accords that ended the Balkan wars, is also an elegy for the vision of American power he represented.

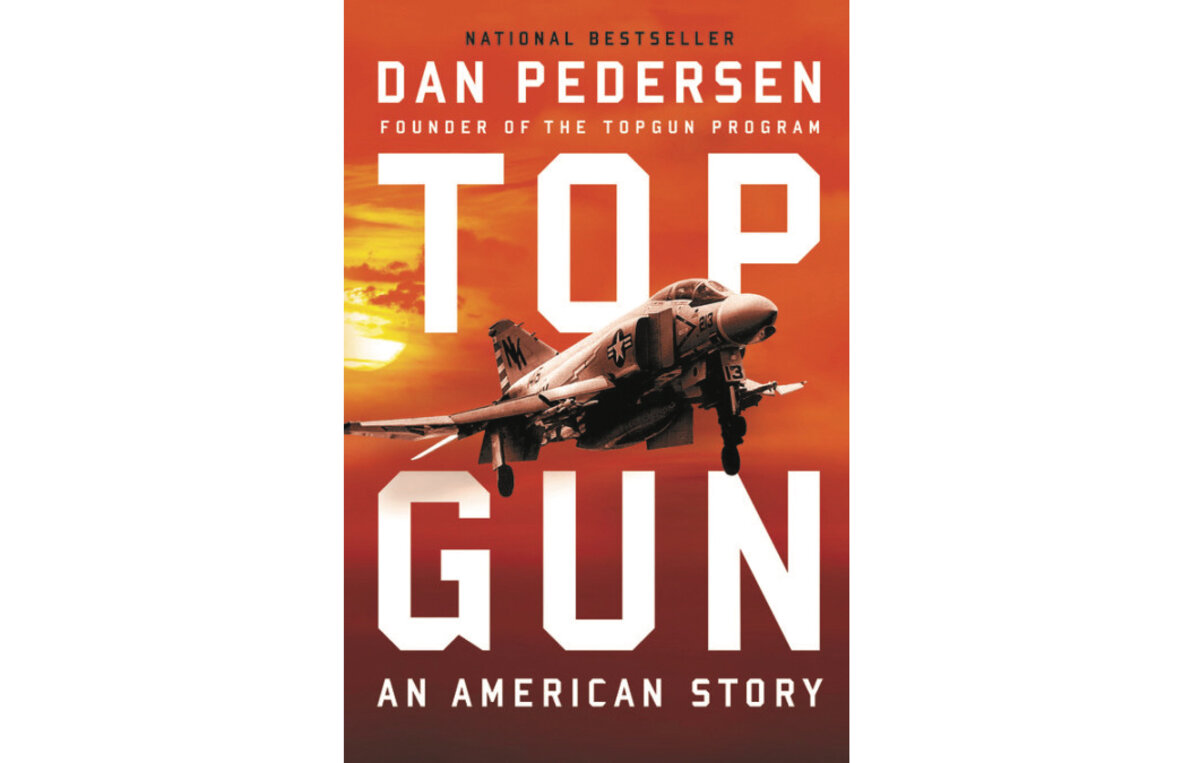

9. Top Gun, by Dan Pedersen

During the Vietnam War, Navy carrier pilots were losing air battles. To remedy this, maverick Dan Pedersen envisioned a “train the trainer” program using the best pilots to develop new tactics. He straps readers right into the cockpit of his Navy F-4 Phantom jet fighter as he chronicles the now-famous Navy Fighter Weapons School, aka “Top Gun.” His bold, white-knuckle action and passion to be the best make this an exciting book from beginning to end.

10. The Impeachers, by Brenda Wineapple

The first president that Congress attempted to remove from office was Andrew Johnson in 1868. Brenda Wineapple’s history of Johnson and the Reconstruction era’s bitter partisanship serve as a corrective to anyone mistaking the end of the Civil War as a period of calm.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The oh-too-rare case of loving political foes

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In today’s call-out culture – when four out of 10 people view those in the other party as “downright evil” – it is becoming news when leaders show a love for others despite a sharp divide over policies, personal traits, rules of engagement, or even basic facts. Their actions often go beyond civility or mere tolerance. They listen with a warm heart to the deeper worries of opponents. The latest example of this rare species in Washington is Jim Baker, who recently resigned as the FBI general counsel. He experienced strong disagreements with the Trump White House and took abuse from the president for simply doing nonpartisan work in the agency. Last week Mr. Baker posted an essay on the Lawfare blog despite objections from friends and colleagues. It is titled “Why I Do Not Hate Donald Trump.”

Might Mr. Baker’s essay on loving Mr. Trump mark a turning point away from America’s descent into the politics of personal contempt? As the presidential race heats up, voters can choose to gravitate toward candidates who honor rather than hound opponents with howls of derision. In politics, love isn’t blind. It can melt hate.

The oh-too-rare case of loving political foes

Many Republicans wonder why President Donald Trump has not tweeted a personal attack against Nancy Pelosi and even meets with her frequently. Does he actually like the House speaker?

Among Democrats, former Vice President Joe Biden is similarly singled out for his tributes to the character or likability of prominent Republicans, from Dick Cheney to William Barr. At the funeral for Sen. John McCain, he said, “I loved John McCain.” He took particular flak earlier this year for calling Vice President Mike Pence “a decent guy.” Some pundits predict Mr. Biden’s aisle-crossing good nature will doom him in the primaries for failing a purity test among party stalwarts.

In today’s call-out culture – when four out of 10 people view those in the other party as “downright evil” – it is becoming news when leaders show a love for others despite a sharp divide over policies, personal traits, rules of engagement, or even basic facts. Their actions often go beyond civility or mere tolerance. They listen with a warm heart to the deeper worries of opponents and, without Machiavellian pretense, admire the good in them. They separate people from their actions and motives to really care for their future or express gratitude for their existence, even for possibly teaching something worthwhile.

The latest example of this rare species in Washington is Jim Baker, who recently resigned as the FBI general counsel. He experienced strong disagreements with the Trump White House and took abuse from the president for simply doing nonpartisan work in the agency. Last week Mr. Baker posted an essay on the Lawfare blog despite objections from friends and colleagues. It is titled “Why I Do Not Hate Donald Trump.”

He wrote, “I will try to love him as a human being. I will try to love his family. And most importantly, I will try to love his supporters – all of them. Loving Donald Trump and loving his supporters is the best way for me to love America and to honor those who sacrificed so much for my freedom.” Mr. Baker does not even want to define Mr. Trump as an enemy in order to then love him in a Christian-style response.

Similar words can often be heard from presidential candidate Cory Booker. When goaded recently by Mr. Trump in a tweet, the Democratic senator responded with sincerity, “I love you Donald Trump,” while promising to defeat the president in the 2020 election.

Such people like to quote Martin Luther King Jr.’s advice that “hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.” But what can that love really look like when the norm in today’s tribal politics is contempt and dehumanization?

In a new book, “Love Your Enemies,” scholar Arthur C. Brooks says the best “contempt killer” is gratitude toward those with whom you disagree. It offers them dignity and makes them feel heard, which can diminish the fears and sadness driving bile emotions. While you may not like a person or their views, gratitude shows you empathize and respect them. It reduces a desire for social distance from those who offend one’s morality.

“Your opportunity when treated with contempt is to change at least one heart – yours,” Mr. Brooks writes. “You may not be able to control the actions of others, but you can absolutely control your reaction.”

Might Mr. Baker’s essay on loving Mr. Trump mark a turning point away from America’s descent into the politics of personal contempt? As the presidential race heats up, voters can choose to gravitate toward candidates who honor rather than hound opponents with howls of derision. In politics, love isn’t blind. It can melt hate.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding a deeper sense of identity, overcoming drug addiction

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By John Kohler

Looking beyond the physical senses for his sense of worth and identity lifted today’s contributor out of hopelessness and brought freedom from substance abuse – an experience that inspired his prayers for others facing such issues.

Finding a deeper sense of identity, overcoming drug addiction

When I was in my teens, I felt as if I didn’t fit in. The educational system didn’t seem to work for me, and I didn’t see any viable employment prospects on the horizon. I was generally unhappy and angry, and I felt pretty hopeless. So I looked for a way out and turned to drugs, just to feel a little better. Along with this came addiction.

I sensed all along that there had to be something to my identity beyond what the physical senses were telling me. I just didn’t know how to tap into that, and now I had this addiction problem. It wasn’t until I was introduced to Christian Science that I found freedom.

That freedom came naturally as I learned more about God and my relation to Him – things that were pretty amazing. The most revelatory idea to me was that as the child of God, my identity was completely spiritual, made in His image and likeness, as recorded in the first chapter of Genesis.

At the time, I wasn’t really thinking that what I was learning would heal the desire to get high. I just knew I was glimpsing a deeper and truer sense of reality, of our dominion over unhelpful influences, than what I had known previously. But it did heal me; the addiction just fell away within a month or so.

What had happened? As I read the Bible and “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Christian Science discoverer Mary Baker Eddy, I was discovering my true, spiritual identity. I learned not to think of myself as a mortal with all these problems. Suddenly the limitations and hopelessness I had been feeling so hemmed in by just dissolved.

Christian Science had opened my eyes to the infinite possibilities of good, which I hadn’t been able to see from my previous limited perspective of looking to matter as the source of my being and satisfaction. I became comfortable with myself, and suddenly there was hope on the horizon. In the years since this healing, I have remained completely free from any desire to use drugs of any kind and have had a fulfilling career.

Our bodies cannot tell us what is true about God’s spiritual creation, which includes each of us. As the offspring of the all-powerful God, we reflect the strength of God. The shackles of addiction, not being from God, good, have no claim on any of us. And there are no unwanted children in God, divine Love. Each and every individual is worthy of His care and has an inherent purpose and opportunity: to express God.

Acknowledging these spiritual facts is a powerful counter to a sense of hopelessness or being stuck. And we naturally start to feel the infinite promise of divine Love and to see that we have no need to depend on matter for satisfaction and pleasure.

I have found this statement in Science and Health very helpful: “Reform comes by understanding that there is no abiding pleasure in evil, and also by gaining an affection for good according to Science, which reveals the immortal fact that neither pleasure nor pain, appetite nor passion, can exist in or of matter, while divine Mind can and does destroy the false beliefs of pleasure, pain, or fear and all the sinful appetites of the human mind” (p. 327). This passage has helped me see that pain, cravings, fears, and matter-based pleasures have no real hold on us because they are not of God, the one divine Mind.

Everyone is entitled to feel the joy and freedom that isn’t a temporary euphoric state of the human mind; real joy and freedom come from a deep and steady spiritual sense of satisfaction whose source is infinite Love.

When we pray about these things, affirming the spiritual facts about God’s creation, we’re counteracting the belief that we are helpless, hopeless mortals and that true satisfaction is elusive and temporary. This elevates the thought of humanity. We may not always see immediate change, but I know that the recognition of my spiritual identity lifted me out of substance abuse. This encourages me to expect that affirming these ideas with a genuine love for others must inevitably have a similar redeeming effect.

Adapted from an article published in the April 4, 2016, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Greetings, Maori style

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow. In Belize, a bold effort to change environmental laws and replant coral has achieved the impossible: It has brought a reef back from the brink.