- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Abortion wars: In Louisiana, softer tone paves way for sharp restrictions

- Trump lowered tensions with Iran: why he had to step in

- Florida voters gave ex-felons right to vote. Then lawmakers stepped in.

- As southern Spain dries up, its farmers get inventive

- In Tokyo rice shop, loyalty to a sacred staple

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The future of the past: Museums as shepherds of our collective story

Saturday is a cultural holiday of sorts. No, it isn’t Memorial Day weekend in the United States already. May 18 is International Museum Day, set by the International Council of Museums to celebrate museums as lively cultural centers for their communities.

Institutions around the globe are celebrating with special events and admissions. Entry into the Philadelphia Art Museum will be free, for instance. All museums in Cairo will be free as well. The Museum of Modern Art Dubrovnik in Croatia will host an art workshop for children.

But on International Museum Day we might also reflect on the struggles of some nations to retrieve and display their own artifacts – their own story – to their own people.

In Africa, efforts to repatriate art stolen or looted during the age of colonialism continues. The Monitor recently wrote on this subject in a story on Nigeria’s claim to Benin bronze reliefs displayed in the British Museum.

Iraq continues to search for antiquities looted from its national museum during the chaos of the U.S.-led 2003 invasion. Hundreds have been returned, but hundreds more are still missing.

As recent fires at the National Museum of Brazil and Notre Dame have reminded us, the world’s cultural institutions are more than repositories for historical artifacts. They serve as bridges between our past and the present. To ensure that role continues well into the future, museums everywhere are reinventing themselves for modern audiences, becoming more interactive, adaptable, and community oriented.

Now on to our five stories for the day, which range from an apparent disconnect within the Trump administration on policy toward Iran to an elderly rice seller’s unique window into the changes of modern Japan.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Looking past Roe

Abortion wars: In Louisiana, softer tone paves way for sharp restrictions

Most Saturdays, college freshman Taylor Gautreaux can be found just outside the property lines of one of Louisiana’s three remaining abortion clinics, located in Baton Rouge. Ms. Gautreaux’s job is to talk women out of going inside. She keeps her voice low and tells them she understands they’re in a difficult spot, but do they realize what they’re getting into? Do they know there are resources to help them, she asks, so they don’t have to kill their child?

Articulate, well-trained, and utterly sincere, Ms. Gautreaux is the type of activist who has helped take the antiabortion movement to the brink of overturning Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court ruling that legalized abortion in the United States. In contrast to the violence and religious hysteria that marked the movement in the 1980s and ’90s, groups like Louisiana Right to Life, where Ms. Gautreaux volunteers, train advocates to talk about the well-being of both the fetus and the mother.

Just this week, Louisiana lawmakers took another step toward passing a bill that would make abortion illegal after six weeks of pregnancy. The same day, the governor next door, in Alabama, signed a law that would ban abortion almost entirely. The Alabama law is so strict that some conservatives have expressed concern.

But in Louisiana, where a brand of socially conscious religious conservatism aligns many Democrats and Republicans against abortion, the twin approaches of compassionate rhetoric and bipartisan lawmaking have been highly effective. “Our goal is twofold: to make abortion illegal and to make it unthinkable,” says Alex Seghers, education director for Louisiana Right to Life. “Louisiana looks very successful compared to the rest of the country.”

Abortion wars: In Louisiana, softer tone paves way for sharp restrictions

Most Saturdays, college freshman Taylor Gautreaux rolls out of bed just after 6 a.m., puts on something carefully neutral – no slogans or religious symbols – and drives about 45 minutes from her dorm in Hammond, Louisiana, to Baton Rouge.

On those mornings, Ms. Gautreaux joins a group that gathers just outside the property lines of Delta Clinic, a squat brick building off Goodwood Boulevard on the city’s west side. Sometimes she arrives to find the place empty. Other times women have already lined up, waiting for one of the last three abortion clinics in the state to open its doors.

Ms. Gautreaux’s job is to talk these women out of going inside. She keeps her voice low, avoiding words like “God” or “hell.” She tells the women – and their partners or mothers, whomever they’re with – that she understands they’re in a difficult spot. But do they realize what they’re getting into, she asks, what the science says about what happens when a woman ends a pregnancy? Do they know there are resources to help them so they don’t have to kill their child? Ms. Gautreaux tells them there’s a center with those resources right next door.

“We don’t want to scrutinize a woman,” she says. “We don’t talk bad about the abortionist. We recognize their humanity, just as much as we recognize the humanity of the unborn.”

Ms. Gautreaux is the type of young activist – articulate, well-trained, and utterly sincere – who has helped take the antiabortion movement to the brink of achieving its long-term goal of overturning Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court ruling that legalized abortion in the United States. For years groups like Louisiana Right to Life, where Ms. Gautreaux volunteers, have trained advocates to frame their cause as a human rights campaign that considers the well-being of both the fetus and the mother. This approach, in contrast to the violence and religious hysteria that marked the movement in the 1980s and ’90s, adopts the languages of social justice and science.

And it’s been mostly successful. Over the past two decades, antiabortion activists have helped push state legislatures to pass hundreds of measures restricting the procedure in anticipation of a Supreme Court case that could lead to Roe’s repeal. Just this week, Louisiana lawmakers took another step toward passing a bill that would make abortion illegal after six weeks of pregnancy. The same day, the governor next door, in Alabama, signed a law that would ban abortion almost entirely in that state, subjecting doctors who perform them to prosecution and leaving no exceptions for rape or incest.

The Alabama law is so strict it has little chance of being upheld in court, and even some conservatives have expressed concern that it’s too extreme. At the same time, abortion rights advocates are pushing back, with states like New York and Virginia passing their own measures to protect the right to abortion in case Roe is overturned.

Amy Irvin's story

But in Louisiana, where a brand of socially conscious religious conservatism aligns many Democrats and Republicans against abortion, the twin approaches of compassionate rhetoric and bipartisan lawmaking have been highly effective for abortion opponents.

Along with the six-week bill making its way through the legislature, the state mandates counseling for women seeking an abortion, a 24-hour waiting period between counseling and when the abortion is performed, and physician licensing requirements for anyone who performs the procedure. In April, the legislature passed the “Love Life Amendment,” which, if approved by voters via ballot in the fall, would change the state constitution to say there is no right to an abortion and taxpayer dollars cannot be used to fund the procedure.

The Supreme Court is expected next term to take up another Louisiana law, Act 620, which would require that doctors who perform abortions have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of the clinic. Opponents say the law could reduce the number of doctors performing abortions to as few as one, and the court issued a temporary stay in February blocking the law from going into effect. But many court observers believe the measure could wind up playing a pivotal role in an incremental overturning of Roe.

“Our goal is twofold: to make abortion illegal and to make it unthinkable,” says Alex Seghers, education director for Louisiana Right to Life. “Louisiana looks very successful compared to the rest of the country.”

A women-centered strategy

Ms. Gautreaux, who’s studying to be a teacher at Southeastern Louisiana University (SLU) in Hammond, where she grew up, discovered activism while researching abortion for a psychology class her senior year of high school. Like many Louisianians, she’s a devout Roman Catholic and was drawn to the idea of applying her faith in the service of what she sees as the most vulnerable humans. She got in touch with Alex Seghers, then director of Louisiana Right to Life’s youth program. Ms. Seghers invited Ms. Gautreaux to a training camp for teenagers interested in learning about abortion and other issues, like bioethics and euthanasia.

Taylor Gautreaux's story

Ms. Gautreaux went to her first PULSE Immersion Weekend in February 2018. Over two days, she heard lectures about the different ways abortion is performed, the purported side effects, and the moral arguments against the procedure. She attended workshops on how to convince others that “the unborn” is a person and how to dispute arguments by abortion rights supporters. She took part in dialogue exercises, including one called “trot out the toddler.”

“Say a woman gets pregnant. She has her baby, and the baby’s around 2 or 3 years old, and all of a sudden [the woman] loses her job,” Ms. Gautreaux explains during a conversation this spring at SLU’s Catholic student center. “You would ask the person who’s pro-choice … ‘Would it be morally permissible for her to kill her toddler?’”

After that weekend, Ms. Gautreaux attended the PULSE weeklong Leadership Institute, held in June, and soon was staffing PULSE weekends herself. When she started college in the fall, she joined the campus pro-life club, where’s she’s now vice president. “I’m super active,” she says. “That’s probably the biggest part of my life.”

PULSE is a study in the so-called new rhetorical, or women-centered, strategy developed in the late ’90s by physician and antiabortion activist David Reardon. Until about 2015, the program was known as Camp Joshua, a name still used by some Right to Life affiliates in other states. But the Louisiana chapter wanted to drop the biblical theme and make the camp more inclusive to students who opposed abortion but weren’t religious. They left behind the giant crucifixes and gruesome photos, recognizing that fear and guilt were unlikely to change anyone’s minds.

They instead developed arguments based on material used by proponents of the women-centered strategy – for instance, that abortion not only harms the fetus but is also linked to depression, post-traumatic stress, and infertility as well as increased risk of breast cancer, which all are claims that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has flatly refuted. Advocates are encouraged to support women at whatever stage of their decision.

“Being in the pro-life movement requires not only a knowledge of the unborn, abortion, and the trauma of abortion, but also compassion, coming from a nonjudgmental place,” says Mia Bordlee, the new youth programs director at Louisiana Right to Life.

It’s a powerful framework that draws young people to the cause. Claire Seymour, a high school junior who’s been involved with Louisiana Right to Life since she was in eighth grade, keeps a big binder of the pamphlets and handouts she’s received from her PULSE weekends. “Every few nights I just go back to it and refresh my memory,” she says from the patio of her parents’ home in Luling, just outside New Orleans. Like Ms. Gautreaux, Ms. Seymour’s personal story contributed to her activism: her parents adopted her from a young single mother in Daejeon, South Korea, when she was about six months old.

“What if she’d decided not to keep me?” Ms. Seymour asks. “I want to make sure that if a woman is going through that type of crisis that she has a place to feel comforted that is not in an act of violence such as abortion.”

Reproductive justice

Kameron Kane also spends a lot of her time outside an abortion clinic. Not in Baton Rouge, though; Ms. Kane is a junior at Tulane University in New Orleans. Her stomping ground is the Women’s Health Care Center, a nondescript building on General Pershing Street, about a mile and a half from campus. But unlike Ms. Gautreaux, Ms. Kane isn’t trying to steer women away from the clinic. She’s there as a clinic escort, to make sure the women can get inside safely with as little harassment from protesters as possible.

With only three left in the state – down from 11 in 2000 – abortion clinics in Louisiana are easy targets for protesters. Some come from as far as Texas or Mississippi, looking for a place to strike. And although groups like Louisiana Right to Life have embraced a less confrontational approach to their advocacy, plenty of others still prefer the old aggressive tactics.

“As the women enter the clinic, these people like to shout things,” Ms. Kane says, frustration creeping into her voice. “‘Why are you killing me, Mommy?’ ‘Why would you do this to me?’”

“They will do everything in their power to ensure women don’t go into the clinic.”

Ms. Kane, who grew up in the Philadelphia suburbs, began volunteering as a clinic escort as a freshman. She’d heard about the operation via the New Orleans Abortion Fund (or NOAF, rhymes with “loaf”), a local nonprofit that raises money for women who can’t afford an abortion. The work suited her: She’d discovered a passion for social justice in high school when she’d watched from afar, online, as protests erupted after the death of Michael Brown at the hands of police in Ferguson, Missouri.

Last fall, a year into her volunteer work, Ms. Kane learned that the Newcomb College Institute, Tulane’s center for women’s leadership, had a program that placed students as interns at community groups working on reproductive issues.

The program is grounded in the concept of reproductive justice, a term coined in 1994 by a group of African American women who felt that the women’s rights movement tended to address only the needs of its leaders, who were mostly white and middle class. They wanted to create their own campaign, one that recognized the links between race, gender, and sexual orientation and the resources, education, and opportunities that determine whether or not women have a real choice in their reproductive lives.

Along with clinic escorting, Ms. Kane does canvassing: standing on city sidewalks, handing out postcards with information on economic justice and abortion access, trying to get people to talk about reproductive rights and health.

The work, while edifying, is also draining, she says. Ms. Kane recalls coming home after two hours of facing down a particularly vocal group of protesters at Women’s Health. “I had to just sit down and take a breath,” she says. “It takes a toll on you as a person.”

“It’s rewarding, and empowering,” she adds, “but at the same time, incredibly frustrating that we even have to be out there.”

A tale of two movements

Amy Irvin’s smile carries the weight of the work week when she sits down to chat late in the day on a Friday. She runs NOAF, which she co-founded in 2012, out of a co-working space in northeast New Orleans. Her office is crammed with the trappings of a life of protest marches and fundraisers: snarky signs, colorful costumes, pink hats.

Ms. Irvin has a soft spot for the Newcomb program. Students are the lifeblood of NOAF, she says; without them the organization would have folded long ago. “They were the very first volunteers with our hotline” – where women can call about anything from information on abortion to financial assistance – “and were really part of that very beginning advocacy work that we did,” she says. The internship, which started a few years after NOAF was founded, formalized the relationship.

Compared to PULSE, the program is far less structured and intensive. Newcomb takes about 10 students a semester, whereas the last PULSE weekend had about 40. Those who work as clinic escorts are taught to avoid engaging with protesters and to keep their emotions in check. There’s also some training around how to have constructive dialogue. (“You know: ‘What you said was racist’ versus ‘You are a racist,’” Ms. Kane explains.) But Newcomb interns are assigned to different organizations, whose needs determine what each student learns. There’s no unified approach, no single goal summed up in a slogan.

Which, in many ways, mirrors the disparity between the two movements in states like Louisiana.

Where Louisiana Right to Life has a national network and strategy to draw on, groups like NOAF and Lift Louisiana – a New Orleans-based nonprofit that educates, advocates, and litigates around reproductive justice issues – are largely working on their own. These organizations juggle providing their usual services with time in Baton Rouge, testifying against as many antiabortion measures as they can afford to. The state solicitor general is right now defending 30 abortion laws and hundreds of lawsuits in court. Six more have been introduced in the current legislative session, which started in April. Even Planned Parenthood, with its broad network, struggles here; the organization is currently tangling with the state Department of Health over a permit to perform abortions in Louisiana.

“None of the organizations working on this issue here in Louisiana have much capacity,” Ms. Irvin says tiredly. “It’s a loosely knit group trying to do a lot.”

With the 2020 election supercharging the debate, however, the stakes over abortion seem higher than ever. Activists on both sides are looking ahead to the day when a case that could lead to Roe’s repeal lands in the Supreme Court. But they recognize that won’t be the end – far from it.

“You can change the law all you want,” Ms. Gautreaux back in Hammond says. “But until we change people’s hearts and minds and educate them compassionately on the issues, we’re not going to see an end to abortion in the United States.”

Ms. Kane dreams of someday using a biomedical engineering degree to advance reproductive health technology and research. And Ms. Irvin – along with raising funds for NOAF, working with students, and testifying before lawmakers at the capitol – is trying to promote women’s stories via a weekly radio program called Pro Frequency.

“I feel proud that we’re still at this,” she chuckles. “I don’t know if anyone thought we would still be around.”

Staff writer Samantha Laine Perfas produced the audio and contributed to this report.

Trump lowered tensions with Iran: why he had to step in

If it’s important for global adversaries to understand the language of diplomacy, a leader’s closest advisers also should agree on what to say. Recently, President Trump and his national security team seem out of step.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

According to administration officials, Donald Trump has privately groused to friends and advisers that John Bolton, with his preference for regime change in Iran, could lead to the Middle East war the president has pledged to avoid. In fact, says one expert on U.S.-Iran relations, there may have never been a president and a national security adviser “less alike.”

With tensions with Iran surging to their highest levels yet in his presidency, Mr. Trump used a White House national security meeting this week to tell acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan he doesn’t want a war with Iran. He was sending a message to Iran and to others in the room.

The spike in tensions with Iran parallels in many ways where the Trump White House was with North Korea in the months that led up to Mr. Trump’s groundbreaking summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, some analysts say. “The North Korea scenario is absolutely what we’re seeing here, in that the president is essentially envisioning a North Korea process with the Iranians that leads to negotiations,” says Ilan Berman, an expert in Middle East regional security. Whether Iran is inclined to meet for negotiations remains to be seen.

Trump lowered tensions with Iran: why he had to step in

As Venezuela appeared last month to be on the brink of a momentous political shift, President Donald Trump’s national security team assured him that indeed the strife-torn South American country was about to take the turn to new leadership the administration had been encouraging for months.

But in the end things didn’t go as John Bolton, the national security adviser, or for that matter Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, said they would. Venezuela’s authoritarian President Nicolás Maduro maintained his hold on power.

And an unhappy Mr. Trump suggested to close friends and advisers that he felt he had been misled by his team.

Now it’s tensions with Iran that have surged to their highest levels yet under the Trump administration. And once again the president is signaling discomfort with the advice and sense of heightened urgency he is feeling from his team – again led by Mr. Bolton – to go full steam toward a confrontational posture.

“John ... has strong views on things which is OK. I’m the one who tempers him, which is OK. I have John Bolton and I have people who are a little more dovish than him,” Mr. Trump told reporters last week.

This week, Mr. Trump reportedly used a White House national security meeting to tell acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan he doesn’t want a war with Iran – and to send a message to others in the room.

Privately, some administration officials say, the president has even groused to friends and advisers that Mr. Bolton and his underlying and long-held preference for regime change in Iran could lead to the Middle East war he has pledged to avoid since the 2016 campaign.

The White House’s Iran tumult underscores an intensifying clash of strategies for addressing the challenges that the Islamic Republic poses to the United States and its allies in the region. And as with Venezuela, the Iran debate has laid bare the discomfort Mr. Trump seems to be experiencing with a team that in some ways is out in front of him – and has misled him before.

North Korea parallels

The spike in tensions with Iran parallels in many ways where the Trump White House was with North Korea in the months that led up to Mr. Trump’s groundbreaking Singapore summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un in June 2017, some regional and Iran policy analysts say.

And they note that the North Korea model of rhetorical fire and fury leading to talks with an avowed adversary is the strategy Mr. Trump appears to favor with Iran as well.

“The North Korea scenario is absolutely what we’re seeing here, in that the president is essentially envisioning a North Korea process with the Iranians that leads to negotiations, even without preconditions,” says Ilan Berman, vice president of the American Foreign Policy Council, a Washington foreign policy think tank, and an expert in Middle East regional security.

But at the same time, the president’s favored route faces competition from two alternative approaches, Mr. Berman says. He boils those down to the “regime collapsers” – Secretary Pompeo and others who prefer strangling the Iranian regime with ever-tougher sanctions and other harsh diplomatic measures – and the “regime-changers” favoring military force, led by Mr. Bolton.

Mr. Trump has gone along with ratcheting up sanctions on Iran to get to negotiations – a route he also took with North Korea – ever since he pulled the U.S. out of the Iran nuclear deal last year. But he has sent multiple signals he is much more wary of the rush to military conflict implicit in the Iran regime-change option.

Indeed, there may have never been a president and a national security adviser “less alike” as Mr. Trump and Mr. Bolton, says Karim Sadjadpour, expert in U.S.-Iran relations at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington.

Analysts note it was a statement issued by Mr. Bolton, and not a presidential tweet, that announced last week the dispatch of an aircraft carrier strike group and Air Force bombers to the Persian Gulf. While the deployment was previously scheduled, Mr. Bolton characterized its timing as a response to “troubling and escalatory indications and warnings” coming either from Iran or from its proxies.

Moreover, Defense Department officials say it was in response to requests from Mr. Bolton that the Pentagon had provided the White House with a variety of options for confronting Iran in the event it attacked U.S. forces in the region or ramped up its dormant nuclear program. One scenario called for the deployment of 120,000 U.S. troops – about the number sent in the initial stages of the Iraq War that topped Saddam Hussein.

Mr. Trump considers that war a “disaster,” while Mr. Bolton, who served President George W. Bush and was a fervent hawk on Iraq, stands by the decision to launch a war.

Frustration on both sides

Neither Mr. Trump nor the Iranian leadership profess to want war, but at the same time both sides are frustrated with the status quo, some analysts say.

“The big spike in tensions we’re seeing right now is a reflection of both Iran and the United States feeling that time isn’t really on their side,” says Alex Vatanka, a senior fellow in Middle East regional security specializing in Iran at the Middle East Institute in Washington.

“On the U.S. side, the Trump administration had hoped that by now the devastating sanctions imposed on Iran would have had some success with the intended regime behavior modification, and would had worked in bringing them back to the negotiating table,” Mr. Vatanka says.

As for the Iranians, “They are increasingly worried about the prospects of the state of affairs they are facing – with these historic, powerful sanctions – becoming the new normal,” he adds, “and they feel they can’t allow that to happen.”

Mr. Vatanka says that helps explain a variety of actions the Iranians have taken recently, targeting the Europeans but also regional adversaries such as Saudi Arabia and Israel that the Iranians consider to be the “B team” to Washington.

“They’re letting people know that ‘If we’re going to suffer, others are going to come along and suffer as well,’” he says.

That “suffering” has ranged from letting the European signatories of the nuclear deal know that Iran will curtail its efforts to stem the flow of drugs and refugees from Afghanistan into Europe if the Europeans cooperate with the U.S. on renewed sanctions, Mr. Vatanka says, to a recent drone attack on a Saudi oil pipeline.

U.S. intelligence agencies also recently detected what they said was evidence of the Iranians loading missiles onto ships patrolling the Persian Gulf. Moreover, intelligence operatives in Iraq recently reported evidence of Iranian proxy groups stepping up activity – including moving in missiles – around U.S. diplomatic installations in Iraq. That intelligence prompted the State Department this week to partially shutter the embassy in Baghdad and the consulate in Erbil in northern Iraq.

It is this kind of “provocation” that Mr. Bolton is responding to in issuing his tough words. But despite the national security adviser’s reputation as a regime-changer, some analysts believe the model he has in mind in the current sparring with Iran is not so much the Iraq War as a limited military operation that could stun the Iranian regime into accepting talks.

The model for such a military offensive might be the limited operation President Ronald Reagan launched in 1988 in response to Iran’s mining of the Persian Gulf, threatening the passage of oil tankers, some analysts say. Operation Praying Mantis resulted in the destruction or disabling of about half of Iran’s naval fleet – without, the analysts note, setting off a full-scale war.

But getting the Iranian regime to the negotiating table with President Trump is likely to be even tougher than pulling off the Trump-Kim rendezvous, most analysts say. The Iranians would need a means of saving face – their economy reeling and Mr. Trump long since established as the boogeyman – before sitting down with the Trump administration.

Pompeo’s 12 points

Moreover, the conditions Secretary Pompeo set a year ago for the U.S. making peace with Iran in a Washington speech – the famous 12 points Tehran would have to meet before shedding its rogue-regime status – are seen by the Iranians as regime change in disguise, and indeed go well beyond anything demanded of North Korea’s Mr. Kim.

“At the end of the day, the Iranians might find a way to bite the bullet” and sit down to talks, Mr. Vatanka says. “But Pompeo’s 12 points are a non-starter,” making talks with the U.S. of Mr. Trump “much harder than when they talked with the Obama administration,” he adds. “This would not be about the optics, it would be about de-escalation.”

The question now, some analysts say, is whether the Iranians decide to wait out the Trump administration in hopes of a less hostile replacement, or if they decide to “bite the bullet.”

“The question is, will [the Iranians] just grit their teeth and try to tough this out … or do they actually come to the table sometime next year and say, ‘Hey, let’s talk about this?’” said retired Gen. David Petraeus, former CIA chief, at a recent discussion in Washington.

Indeed, some experts believe Iran is interested in finding a way to launch a dialogue with Washington. But they note that while the president has spoken publicly and privately of sitting down with the Iranians, Trump administration officials are not believed to have sent feelers to Tehran in the midst of the all-pressure-all-the-time campaign.

At the same time, they note that the Trump White House lacks a direct channel to Tehran, of the sort the Obama administration had during secret talks with Iranian officials, with Oman and Switzerland acting as go-betweens.

Mr. Berman of the American Foreign Policy Council describes the Trump administration strategy toward Iran as “very much front-loaded,” with all of the focus on means of pressuring Tehran to modify its behavior.

Less thought has been given to the goals the administration wants from launching an engagement process with Iran – one he says would be considerably more complicated and lengthy than the one with North Korea.

What the basis of a process won’t be, Mr. Berman says, is Mr. Pompeo’s 12 points. “However you rack and stack those 12 demands, they look an awful lot like capitulation,” he says. “And I don’t think that’s conceivable on the Iranian side.”

Florida voters gave ex-felons right to vote. Then lawmakers stepped in.

What does it mean to complete a sentence for a crime? That definition lies at the heart of a change in Florida that means about 500,000 people will not see their voting rights restored.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

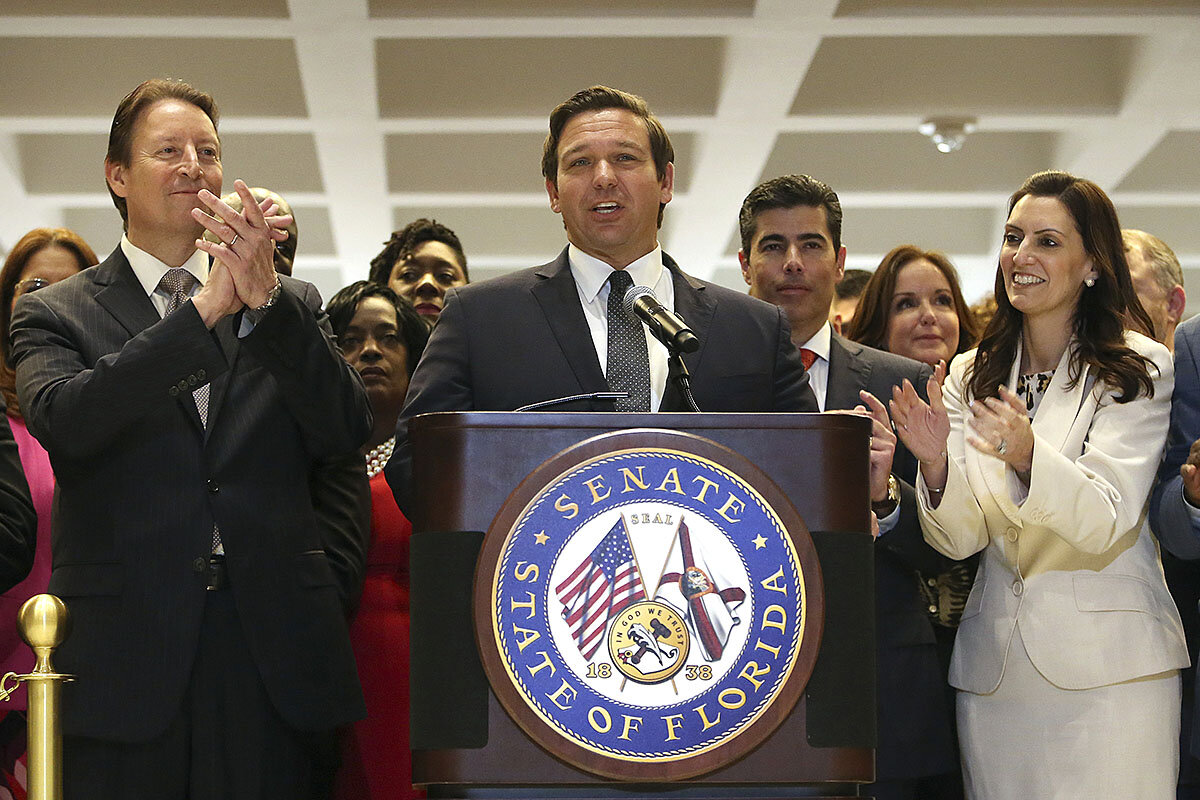

Last fall, Florida voters passed the largest reenfranchisement of U.S. voters in more than 40 years. Originally, it would have involved some 1.4 million Floridians who had served their felony sentences.

This week, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis is signing into law a bill that formalizes that amendment but adds a controversial definition: tying the full payment of fees, fines, and restitution to the phrase “sentence served.”

There will still be as many as 840,000 people regaining the right to vote, a new army of voters that could hold huge sway in the tightly divided swing state.

Yet in withholding the vote from about half a million people, “it’s quite clear the Legislature has gone well beyond what nearly two-thirds of Floridians thought they were voting on,” says political scientist Daniel Smith.

It is not by definition a poll tax, as critics have termed it. But it is also, says Coral Nichols, unfair.

“I call it the gray area – people like me,” says Ms. Nichols, a Republican who runs a nonprofit prison diversion program in Seminole, Florida. She still owes $190,000 in restitution, toward which she pays monthly. “Lawmakers need to consider the people in the gray.”

Florida voters gave ex-felons right to vote. Then lawmakers stepped in.

Coral Nichols estimates she will have to live to 188 to be able to vote again in her home state of Florida.

For the devoted “duty, honor, country” Republican, that is heartbreak after hope.

Having completed her prison sentence for grand theft, Ms. Nichols believed she would have her right to vote restored after 64 percent of Floridians voted in favor of Amendment 4 last November. The amendment ordered automatic vote restoration for some 1.4 million Floridians who can’t vote because of past felonies.

But this week, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis is signing into law a bill that formalizes that amendment but adds a controversial definition: tying the full payment of fees, fines, and restitution to the phrase “sentence served.”

It is not by definition a poll tax, as critics have termed it. But it is also, Ms. Nichols argues, not fair. Yes, she owes $190,000 in restitution, but she says her judge made clear that she has no criminal sentence obligations left after he converted her debt into a civil lien, toward which she pays $100 a month.

“I call it the gray area – people like me who do not fit your black-and-white, cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all policies,” says Ms. Nichols, who runs a nonprofit prison diversion program in Seminole, Florida. “My sentence is complete, I’m completed, and this is the thing that echoes within the very depths of my soul. I am the gray, and lawmakers need to consider the people in the gray.”

The vote last fall became the largest reenfranchisement of U.S. voters since 18-year-olds were given the right to vote in 1971. Originally, it would have involved some 1.4 million Floridians – more voters, in fact, than there are Vermonters.

There will still be as many as 840,000 “returning citizens” surging the polls, a new army of voters that could hold huge sway in the tightly divided swing state.

Yet in withholding the vote from about half a million people like Ms. Nichols, “it’s quite clear the Legislature has gone well beyond what nearly two-thirds of Floridians thought they were voting on,” says University of Florida political scientist Daniel Smith, an expert on how legislatures treat ballot measures.

“The [constitutional] amendment says, if you read it, you have to complete your sentence,” Governor DeSantis said at an environmental issue forum at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. “And I think most people understand you can be sentenced to jail, probation, restoration if you harm someone. You can be sentenced with a fine. People that bilk people out of money, sometimes that is an appropriate sentence. That’s what the constitutional provision said. I think the Legislature just implemented that as it’s written.”

Two of the people behind Amendment 4 – Desmond Meade and Neil Volz – opposed the addition. They say their organization, the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, attended myriad Senate subcommittee meetings as the bill made its way through the statehouse. One day 600 former felons showed up to discuss the amendment.

‘Win at the margins’

To critics, the decision of the Legislature and governor to impose their will on the law is part of an emerging Republican playbook: winning by subtraction. The stakes are huge, with Florida shaping up to be a key battleground in 2020.

“The plight of voter rights [in Florida] is part of that bigger narrative of the right: to win at the margins,” says Texas Tech University political scientist Seth McKee, a longtime Florida observer. “It’s not a Southern thing. It’s a competition thing.”

Yet the nine-year effort to restore full citizenship to former felons, its proponents say, remains “about people, not politics.”

Amendment 4 “was framed as a question of right and wrong, of morality, of returning a civic voice to people who had served their sentences – a come-back-home,” says David Daley, author of “The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy.” “That united people across racial lines in Florida. ... This was a supermajority of Republicans, Democrats, independents, whites, blacks, Latinos – a real coalition.”

The decision by Mr. DeSantis and the GOP-led Legislature to alter the decision of nearly two-thirds of a state’s electorate is not an uncommon reaction to ballot initiatives. The Massachusetts Legislature voted to delay legalizing recreational marijuana sales after voters approved it in 2016. Also in 2016, voters in Maine approved four ballot questions and a bond issue. In 2017, the state Legislature voted to amend or repeal three of the four measures. (Maine lawmakers tried but ultimately failed to repeal a ranked-choice voting law.)

But Florida also has a history of voter suppression that traces back to the Civil War. Historians there say that the roots can be traced back to the day when a group of boys and older men fended off a Union attempt to take Tallahassee in early 1865, leaving it the only Confederate capital not to fall.

That factored into the Florida’s unique sense of invincibility, that it could in practice, if not legally, ignore what Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice Charles H. DuPont in 1865 called “the exactions of the fanatical theorists.”

“Deep into Florida history, back when Florida was a Southern state, there was a realization after the Civil War that [black people] are potential voters now,” says Gary Mormino, author of “Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams,” a social history of Florida. “And [the disenfranchisement] that happened wasn’t really a conspiracy, because it was pretty wide out in the open. They basically said, ‘What can we do to keep African Americans from taking over Florida?’”

To be sure, Florida was also the first state to abandon the poll tax in the 1930s, setting it on a course that differentiates it from the rest of the Deep South to this day. Today, it is “not a Southern state,” as Mr. Mormino says, but more a smudged window on the nation.

Former felons at the polls

For some former felons who will be able to vote in the next election, the state’s unique social and historical dynamic reverberates in their desire to be “returning citizens.” And the battleground nature of the state, they say, means that the plight of a single person’s rights in Florida should be a concern for all Americans.

“Florida has a national spotlight on it; it’s a transient state, all those different attitudes and traditions coming together – a place where it’s way too hot and people’s tempers get out of control,” says Lance Wissinger, a former felon whose new Florida voter registration card sits behind his ID in his wallet. “It’s the swamp, man. It is a mixing bowl of just craziness, and I think that spills over into the politics of the state.”

In the 20th century, the state pioneered a slew of onerous rules that disproportionately affected black voters. It was the first and only state to add larceny – a civil matter – to the list of disqualifying crimes. The threshold for a third-degree felony was set at $300, the lowest in the United States.

The strategies were so effective that in the 1960s there were only seven black people registered to vote in Gadsden County – a county that had about 12,000 African Americans old enough to vote, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

Before November’s vote, Florida also had the country’s strictest clemency system. Since its rules were changed in 2011 under former Gov. Rick Scott, only 3,005 of 30,000 applicants had their voting rights restored.

That put Florida – ground zero of the 2000 election controversy that was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court – into a class of its own when it comes to disenfranchisement. Some 10 percent of all potential voters and 21 percent of potential black voters had lost the right to vote.

“It is hard to believe that the intensity of the partisan efforts now to put up barriers between certain voters and the ballot box is unrelated to the larger questions of a changing America,” says Mr. Daley.

There appears to be a perception on both sides of the political aisle that more of the new voters may lean Democrat than Republican, but no one actually knows their political makeup, Professor McKee says.

“Republicans own the tough on crime issue, so, knowing that, any Republican would look [at ex-felons] and say, ‘Oh, boy, these people getting out of prison – that is not my constituency.’ And I think they are right, for the most part. But there could be a lot of those white guys who are coming out who like Trump. What is to say they don’t?”

‘A whole brand-new start’

For example, the next time Floridians go to the ballot box, Mr. Wissinger will be there.

After being convicted for manslaughter for the death of his best friend in a drunk driving accident, Mr. Wissinger became a model citizen in prison – the kind of prisoner who, while incarcerated, wins a silver medal at the America’s Chef Competition as part of a work release program and starts a Toastmasters club behind bars.

He is a registered Republican and now owner of a drone company in South Florida, and his quest to vote touches on something common among people who can’t vote: personal quests not just for redemption, but also for restoration of their patriotic worth.

“I don’t think you can be a citizen without a vote,” says Mr. Wissinger. “When I was finally able to register to vote again ... I was asked afterward about how I felt, and I was, like, ‘Man, it’s New Year’s Day. It’s a whole brand-new start to everything.’”

Republicans, says Mr. Volz of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, have not been deaf to those points. The Legislature recently raised the third-degree felony minimum to $750 – a small yet substantial change.

“What we are seeing is that people like myself who have lost our voice and then regained it, we’re the biggest evangelists for democracy,” says Mr. Volz, a former Republican congressional aide who was convicted for his involvement with the Jack Abramoff lobbying scandal. “That means we will continue to move forward in the spirit of Amendment 4, which is one of celebration of democracy and a belief in second chances. Full steam ahead.”

As southern Spain dries up, its farmers get inventive

Fending off the ravages of climate change in Spain’s farmland may turn on how well its farmers can adopt new techniques that help restore their environment’s life-giving capacities.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Dominique Soguel Correspondent

Spain today is the world’s third-largest almond producer. But climate change, coupled with soil erosion, threatens to change that, not just for the almond crop, but for the wider fruit basket that is Spain. If the worst-case-scenario climate change models play out – with global temperature increases of 5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, versus the Paris climate agreement target of 1.5 degrees – all of southern Spain would become desert.

In response, farmers and organizations across Spain’s Andalusia region are experimenting with new techniques and strategies to revitalize the land sustainably. For example, the company La Almehendresa brings together more than 20 partners who want to go beyond organic farming and focus on regenerative methods.

“We want to see the expansion of ecological, regenerative agriculture,” says Frank Ohlenschlaeger, director of La Almehendresa. “We want to restore degraded soils and landscapes. All of this with the goal of combating climate change because this is a red zone when you look at a map on the risks of desertification.”

As southern Spain dries up, its farmers get inventive

Finding wild asparagus sprouting at the feet of his almond trees puts a smile on the face of Juan Garcia Chacon, a Spanish farmer. The natural vegetation is a sign that the farm’s strategies to counter erosion are working.

Mr. Chacon, who last year left a job as a vehicle test driver to farm alongside his retired father, is one of many farmers across Spain’s Andalusia region who are working to find new agricultural practices to counter the dry winds of climate change. “My first year is marked by few almonds but tremendous hope,” he says with conviction.

Climate change experts estimate that two-thirds of Spain is vulnerable to encroaching desertification and accelerated soil erosion. Due to a mix of natural and socioeconomic factors, the Mediterranean nation is considered the worst afflicted when it comes to land degradation in arid, semiarid, and dry areas of the European Union. So farmers like Mr. Chacon are turning to regenerative agriculture in a bid to revitalize local landscapes, economies, and communities.

“I must leave this land in the best conditions possible,” says Mr. Chacon. “If I don’t take seemingly simple steps, we will lose this land to erosion and lose the almond trees,” says Mr. Chacon. “We will leave the next generation with no place to live or work.”

Spain’s warming fruit basket

The Chacon family has been growing almond trees for the better part of four decades. Like many in this region, they historically focused on cereals, and only planted almond trees on the border of their fields. But that changed when they grasped the enormous commercial potential, both at home and abroad, of the almond, prevalent in Spanish sweets and across bar tables.

Spain today is the world’s third largest almond producer behind Australia and the United States, which is the world’s top producer by a big margin. Rising prices, coupled with the knowledge that their countrymen are often eating California almonds rather than local products, has led many Spanish farmers here to invest in the almond.

The quality of the soil across the 21 hectares (52 acres) owned by the Chacon family is mixed – depressingly gray but viable in parts, iron-rich and promisingly red in others. The variety of almond trees grown here bud in March rather than between November and February. Almond trees need the cold to thrive, but a harsh frost can destroy their delicate fruit.

But climate change, coupled with soil erosion, threatens to change that – not just for the almond crop, but for the wider fruit basket that is Spain, where much of the land is semiarid with bitingly cold winters and hot summers.

In the southern region of Andalusia, the country’s most populous and with a landmass equivalent to Ireland, assessments of the risk of desertification range from high to very high. If the worst-case-scenario climate change models play out – with global temperature increases of 5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, versus the Paris climate agreement target of 1.5 C or 2.7 degrees F – all of southern Spain would become desert. The regional authorities recognized the threat and prioritized the fight against desertification already in 1989. In some parts of southeastern Spain, 80 tons of soil per hectare are lost annually due to soil erosion. To date, an estimated 5% of all Spanish agricultural land has undergone a degree of erosion characterized as irreversible.

Agriculture is not the main driver of the Spanish economy. It employs less than 2% of the Spanish workforce and represents less than 3% of gross domestic product. But it remains important; within the European Union, only France dedicates more of its land to agriculture. Spain ranks first in organic farming in the bloc and is among the top five in the world. Andalusia itself accounts for half of Spain’s ecological production.

Average temperatures have risen faster in Spain than in other parts of Europe, pushing some local almond farmers to shift toward the pistachio tree. In some parts of southern Spain, temperatures could rise by 6 degrees C by 2050 rather than the projected average of 2 degrees.

Mr. Chacon admits that almond farming has been tough, and that success or failure can hinge on 1 degree, the tiny difference between zero and subzero temperatures that manifests itself even within his land. “This year we had timely and gentle rains, but we suffered a heavy frost at the end of March,” he says, cracking open vibrant green almond buds to reveal damaged brown interiors. A healthy almond, he notes, opening a bigger bulb in better shape, is translucent.

There is no doubt in his mind that it will be difficult to match last year’s yield and income: about 20,000 kilos (44,000 pounds) of almonds, 35,000 euros ($39,000). But he is an expert at eking joy from the farm, finding the trade-off of more time and less money more than worth it in the company of his parents, partner, and pointer dogs.

His spirits visibly lift when his feet sink into a borderline muddy patch of soil, palpable evidence that his efforts to form terraces, natural water beds, and sheet mulching are working. “Look, no erosion.”

‘This is commonsense agriculture’

Mr. Chacon is also part of a growing network of farmers, brought together by the AlVelAl Association, who are trying to breathe life back into the ghost towns of Andalusia.

With nearly 300 members spread across the Spanish plateau regions, AlVelAl aims to revive local communities just as much as the landscape. It does so by lending financial and technical support to farmers, agritourism businesses that source locally, and regional entrepreneurs.

The results are on display in Chirivel. An agriculture fair in March showcased the efforts of multiple generations taking pride in local traditions and experimenting with new techniques.

Frank Ohlenschlaeger, a native of the German town of Hanover who settled in Spain 25 years ago, is using the fair to test consumer reaction to a combination of toasted almonds, salt, and aromatic herbs like rosemary and thyme grown between the almond trees. His company, La Almehendresa, brings together more than 20 partners who want to go beyond organic farming and focus on regenerative methods.

“We want to see the expansion of ecological, regenerative agriculture,” he says. “We want to restore degraded soils and landscapes. All of this with the goal of combating climate change because this is a red zone when you look at a map on the risks of desertification.”

Almehendresa and AlVelAl are projects that took root in Spain thanks to Commonland, a Dutch foundation that carries out similar work in the Netherlands, South Africa, and Australia. Such initiatives fit into a broader global effort to restore 150 million hectares (580,000 square miles) of the world’s deforested and degraded land by 2020 and 350 million hectares (1.3 million square miles) by 2030.

Santiaga Sanchez, a major landowning and leading female farmer in the region, stumbled on making water-collecting patches of grass between her almond trees because she needed room for her goats to feed. Training up the next generation of farmers through work placements, she says she is optimistic because there are signs of change, even if slow and gradual.

“We haven’t invented anything,” she says on the sidelines of a panel discussion on the merits of regenerative agriculture organized by AlVelAl. “This is commonsense agriculture. Mother Nature is so wise and so grateful that as long as we stop stabbing her, she will respond.”

Change, everyone here knows, is ultimately not in the hands of farmers, but consumers.

“What we eat transforms the territory,” says Loli Masegosa Arredona, an expert in sustainable nutrition and co-president of AlVelAl. “What is the point of an organic product if it destroys the environment? So, let’s stop for a moment and think: What kind of territory do we want? Our diets are a tool to change the landscape.”

This story was produced with support from an Energy Foundation grant to cover the environment.

In Tokyo rice shop, loyalty to a sacred staple

Sometimes you stumble across a single place, or person, whose story tells a much larger one. That’s the case with this tiny Shinjuku rice shop, as its owner tries to weather change and keep true to a time-honored trade.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In Japan, rice isn’t just a grain. Over the centuries, it has served as a store of wealth; a mealtime staple, three times a day; and inspiration for paintings and poems. Today, it sits at the center of the most formidable agricultural lobby in the world, with an iron-willed policy to restrict foreign imports. In short, it’s national pride.

That doesn’t mean selling it is easy. Households consume half the rice they did half a century ago, thanks to a declining population and a shift toward Western tastes.

“I’m barely staying afloat,” says rice shop owner Koichi Ogawa, perched on a stool amid the tools of his trade: a rice mill, large metal scale, and burlap sacks. The shop does one-third of the business it did three decades ago, and it’s his pension – not profits – that covers basic expenses.

Many other shops have closed their doors, and someday his may, too. Even Mr. Ogawa’s own daughter prefers two-minute microwave rice. But for now, his loyalty is to his 70 customers: patrons who appreciate the texture of the grains in their hand, and purchase three kinds just to try a new variety.

“I can’t do anything about societal changes,” he says. “But I can sell quality rice.”

In Tokyo rice shop, loyalty to a sacred staple

Loyalty to rice, loyalty to customer.

These are the driving motivations behind Koichi Ogawa’s tenacity as a Tokyo shopkeeper. “I’d be very sad if I had to close – I’ve grown up with this store,” Mr. Ogawa says of the Kinsei Ogawa rice shop, a trade that’s been in his family since the 1940s.

Located down a tiny street in bustling Shinjuku, Kinsei Ogawa has seen it all: The bubble economy of the 1980s whose deflation caused corporations to fail, but spared the mom-and-pop vendors supplying staples of everyday life. The 2011 earthquake whose tsunami washed away rice farms, driving up wholesale prices and forcing him to purchase black-market rice.

Today, Mr. Ogawa struggles with a new conflict: the tension between the economic realities of a dying industry, and a stubborn devotion to the 70 customers he has left.

“I’m barely staying afloat,” he says, perched on a stool in his shop, surrounded by the tools of his trade: a rice mill, large metal scale, and burlap sacks. Kinsei Ogawa is doing a third of the business it did three decades ago, and it’s Mr. Ogawa’s pension – not profits – that covers basic expenses. Still, he keeps his doors open, even as others of his generation declined to take over their fathers’ businesses.

In Japan, rice is more than just a staple: It signifies the pride of a country and culture. Over the centuries, the grain has morphed from a store of wealth to the focal point of the dinner table. Rice is at the center of the most formidable agricultural lobby in the world, not to mention one of the most hotly-debated items in national policy.

Yet cultural and demographic shifts have left rice merchants like Mr. Ogawa behind. A declining and aging population, along with a shift toward fast food and Western tastes, means less demand overall. Now his loyalty to the grain – and its buyers – harkens to a bygone era.

“Rice has cultural cachet,” says University of Chicago professor Thomas Talhelm, who’s spent a decade studying the connection between rice agriculture and cultural behavior in Asia. “I can imagine that if [Mr. Ogawa sold] beans, it would be easier for him to give it up.”

‘Rice as Self’

In Japanese, the word for meal – gohan – is actually the word for cooked rice.

Rice is so intertwined with culture and language that it’s central to Japanese identity, says Nicole Freiner, a professor at Bryant University in Rhode Island who recently wrote “Rice and Agricultural Policies in Japan: The Loss of a Traditional Lifestyle.” It has served as money, at a time metal was considered “dirty”; an offering at shrines; and sustenance, eaten three times a day.

Rice paddies themselves are heralded, portrayed in everything from Japanese paintings to poetry. They are “our ancestral land, our village, our region, and ultimately, our land, Japan,” writes anthropologist Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney in her book “Rice as Self: Japanese Identities Through Time.”

Understanding the symbolic-cultural significance of rice is critical to understanding the modern hullabaloo around it. For years, at the behest of the lobbying organization Japan Agricultural Cooperatives, the government has paid farmers to produce rice, and heavily subsidized the crop. As a result, consumers are penalized twice in the name of protecting farmers – once via taxation and a second time at the counter, with rice prices kept artificially high.

Perhaps the most iron-willed policy of all is a restriction on foreign imports, aiming to prop up the homegrown version. Indeed, the tariff on imported rice beyond set quotas has been, roughly, anywhere between 300 and 700 percent in recent years. The government’s longstanding intervention in rice is, “from a world perspective, unparalleled in its degree,” writes Dr. Ohnuki-Tierney.

Today, rice derives its symbolic power from day-to-day sharing among family and friends. And it builds community not only at the dinner table, but back at the rice paddy: Rice is more labor-intensive than any other staple crop. In other words, it requires a village to raise it.

In the end, any governmental protections may come too late to save the rice merchant, much less the farmer. Policies that benefitted small sellers like Mr. Ogawa are long gone. Up until about 1970, Japanese bought staples with a food stamp, initially introduced when rationing was required. Effectively, this system required people to purchase at local shops. That system’s demise, in part, gave rise to the power of the supermarket.

Meanwhile, households in Japan consume only half the rice they did a half-century ago – down to about 56 kilograms per capita each year. Rice shop owners can seem the final point of contact between a customer and a cultural relic, as both grain and merchant shift toward scarcity.

Loyalty to quality

Back in his Tokyo shop, Mr. Ogawa is more than happy to wait for the occasional customer. After all, working is a form of exercise. “Those who closed their businesses go jogging to stay healthy,” he says. “I stay active because I carry rice daily.”

The family tree isn’t an option for succession; his daughter prefers two-minute microwave rice to the slow-cooked version. His son was willing to learn the trade, but Mr. Ogawa talked him out of it, since “he wouldn’t be able to make a living.”

Hiring a foreigner wouldn’t be an option, either, though immigration has been posited as a salve for Japan’s labor shortage. “There are more than 100 different kinds [of rice] to explain to customers,” Mr. Ogawa explains, and a newcomer might not grasp the ins and outs.

Meanwhile, the shop grows quieter, year by year. Two years ago, the elementary school down the street shuttered its doors, as young families moved in search of more affordable housing. Where schoolchildren used to parade past Mr. Ogawa’s line of vision twice a day, like clockwork – just before 8 a.m. and a touch after 3 p.m. – there’s now silence.

“The kids used to say, ‘Good morning, rice shop man!’ when they walked by,” Mr. Ogawa says, fondly. “And in the afternoon, ‘Hi, rice shop man! I’m done for the day.’ It was lively in this neighborhood. It was fun.”

He waits for his few customers. “They’re all rice lovers,” he says with gratitude: patrons who appreciate the texture of the grains in their hand, and purchase three kinds just to try a new variety.

“I can’t do anything about societal changes,” he says. “But I can sell quality rice.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Food aid for hungry North Koreans?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

North Korea’s Kim Jong Un has enjoyed the high prestige of meeting an American president twice in the past year. Defiant of global sanctions, he continues to test ballistic missiles and defy demands to denuclearize. Despite all this strutting on the world stage, however, Mr. Kim has a new problem. The United Nations estimates 40% of North Koreans will suffer severe food shortages in coming months, a result largely due to bad weather as well as too much spending on armaments.

Despite the crisis, North Korea criticizes plans by South Korean President Moon Jae-in to provide $8 million in food aid. In the end, Mr. Kim will probably accept the aid, as the regime has done in the past.

Under international sanctions, such aid is allowed, and for good reason. Not only is it necessary to keep innocent people alive, but it is part of Mr. Moon’s strategy of making “small steps” toward trust-building.

It also points out the contradiction between the regime’s claim to greatness and the reality of everyday life for North Koreans. The people there cannot eat nuclear weapons. But they can be sustained by South Korean compassion.

Food aid for hungry North Koreans?

For a young leader – with a nuclear arsenal at the ready – North Korea’s Kim Jong Un has enjoyed the high prestige of meeting an American president twice in the past year, not to mention summits with the heads of Russia, China, and South Korea. Defiant of global sanctions and determined to display his power, he continues to test ballistic missiles and defy demands to denuclearize.

Despite all this strutting on the world stage, however, Mr. Kim has a new problem. The United Nations estimates 40% of North Koreans will suffer severe food shortages in coming months, a result mainly of bad weather as well as too much spending on armaments. The last time North Korea saw mass famine was in the mid-1990s. Hundreds of thousands of people died. And the Kim family regime had to allow unofficial food markets to take root in a strict socialist economy that is one of the poorest in the world.

This time, Mr. Kim must decide whether to accept the food aid. The regime admits that annual precipitation has been at its lowest since 1982. Food production is also at a 10-year low and could fall another 12% this year. The government has reduced food rations to extremely low levels.

Despite the crisis, North Korea criticizes plans by South Korean President Moon Jae-in to provide $8 million in food aid. The aid is being considered by Seoul out of humanitarian concerns but also to nudge the North toward concessions on denuclearization. The United States says it does not oppose such aid as long as it is distributed to people in need rather than the North Korean military.

In the end, Mr. Kim will probably accept the aid, as the regime has done in the past, both for its own survival and in hopes it might lead to an easing of economic sanctions by the U.S. The last time that South Korea provided food assistance was nine years ago.

Under international sanctions, such aid is allowed, and for good reason. Not only is it necessary to keep innocent people alive, it is part of Mr. Moon’s strategy of making “small steps” toward trust-building between the two countries.

The South’s generosity serves as a strong counterpoint to the North’s many provocations. Food aid sends a message of unity between the two Korean people. It highlights the universal desire to protect the innocent despite political differences.

It also points out the contradiction between the regime’s claim to greatness and the reality of everyday life for North Koreans. The people there cannot eat nuclear weapons. But they can be sustained by South Korean compassion.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

no mote or beam

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Joni Overton-Jung

Here’s a poem pointing to everyone’s innate ability to express God’s light and love. The title refers to Jesus’ teaching about focusing on others’ “motes” – that is, judging them for their smaller faults – even as we ignore the much larger “beams,” or flaws, impacting our own ability to see clearly.

no mote or beam

no mote

or beam*

can mock

the shaft

of light

you aretoo luminous

for night

to leave some markno

you are made

for light

of light

God’s lightLove’s halo rests

on you

through youno mote

no beamjust rivulets

ripples

riversresplendent

dawn

*See Matthew 7:1-5

Originally published in the July 2, 2018, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

In Uganda, a wellspring of hope

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with us today. Come back Monday, when we’ll look at the shifting role of the car in American life.