- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Fury at elections snub brings Moscow’s professionals back to politics

- Confederate statues and the future of America’s past

- US immigration and families: A tale from the Holocaust era

- Job training that puts people – and their community – back on track

- Hail this taxi, but hold on tight – boda-bodas swarm Kampala streets

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Women drive toward independence

Kim Campbell

Kim Campbell

Welcome to the Daily. Our stories today include one on mounting protests in Moscow and several focused on problem-solving – around Confederate statues in Atlanta, immigration and job training in the United States, and transportation in Uganda.

But first, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, women are doing something unusual to help each other: riding scooters.

As in other parts of the world (see today’s story from Kampala, Uganda), two-wheelers are a time-saving way to navigate gridlock. But Lily Ride also helps with another issue: sexual harassment. More than 90% of women who use public transportation in Bangladesh report experiencing it, and they also encounter it from typically male scooter drivers. Having both genders on the road is in demand, but not always welcome.

“If our prime minister can be a woman, why can’t I ride a bike?” one new driving recruit, undeterred by critics, tells the BBC.

The jobs in Dhaka are contributing to the improved access to resources mentioned in the United Nations report “Progress of the World’s Women 2019-2020: Families in a Changing World.” Elsewhere, in the U.S., job training support is being offered to women by people like Marvin DeJear, whose contributions we highlight today.

Migration is another focus of the report, recommending that women refugees and asylum-seekers be registered separately from men, and granted separate residency, too. One woman’s experience immigrating to the U.S. during World War II is featured in today’s package.

Back in Dhaka, Syed Saif has seen greater agency come from the service he founded. “We believe that when women are more free and independent on the roads, they can be more strong in their households as well.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Fury at elections snub brings Moscow’s professionals back to politics

Moscow’s urban professionals for many years have been willing to surrender political activism in exchange for material gains. But the protests roiling the city in recent weeks show a political reawakening.

Moscow, as the intellectual, cultural, and business center of Russia, has a very high proportion of highly educated, well-traveled professionals. During the Putin era, this class has been left to immerse itself in private lives and careers, and incentivized to ignore politics. So for many years, they have been dormant.

But that changed in July, when Moscow’s unelected technocratic administration opted to bar 19 independent candidates from registering for elections to the city’s largely toothless city council. The blunt denial of a minor political exercise has triggered weekly protests in the city, with crowds reaching up to 60,000, the largest such demonstrations in almost a decade.

Yet as in the previous cycle of protests against election fraud, the current wave is probably limited by its social base. Urban professionals and Russia’s liberal opposition, including anti-corruption crusader Alexei Navalny, have thus far seemed unable to forge connections with the broader masses of Russians, or even Muscovites. Surveys suggest that many more Russians are growing restive after several years of stagnating incomes and slow economic growth, and disenchanted with their government, but their priorities lie more with bread-and-butter issues.

Fury at elections snub brings Moscow’s professionals back to politics

It is Russia’s biggest political crisis in almost a decade, and one that seems to define the limits of democratic evolution under Vladimir Putin.

Throughout the summer, central Moscow has been rocked by weekly protests – some permitted by authorities, others not – against the city’s unelected technocratic administration. Even the licensed rallies have been hemmed in by massive, intimidating police presence. The unauthorized, flash-mob-style protests held on alternate weeks have been met with unprecedented police brutality and mass detentions.

At the heart of the demonstrations is the outrage of a large and influential segment of the population at the curtailment of their limited democratic rights in the Putin era. This group, which seems to be primarily made of liberal, cosmopolitan professionals, has been left to immerse in their private lives and careers and incentivized to ignore politics for most of the Putin era.

“Many are engaged in civic activism, they are active in social media, and tend to be very politically aware,” says Masha Lipman, editor of Counterpoint, a Russian political journal published by George Washington University. But instead of being allowed what they regard as their right to vote for candidates who speak their own political language in a minor municipal election, they were denied and then subjected to weeks of police violence. “This is what drove the protests.”

“Profoundly offended”

Moscow authorities made the fateful decision in early July to bar 19 independent candidates, mostly known liberal activists, from registering for Sept. 8 elections to Moscow’s largely toothless 45-seat city council.

The electoral commission cited irregularities in meeting the onerous requirements for registering an independent candidacy, including gathering nominating signatures from 3% of a constituency’s voters within one month, as the reason for barring those activists. Thousands of people who signed nomination forms for independent candidates saw their signatures dismissed as fake by bureaucrats, and were even ignored when some turned up in an effort to verify them.

Yet the commission also allowed several independent candidates associated with the pro-government United Russia party to scrape through the process.

The message was not lost on anyone.

“It seems clear that the government is adamant about not letting anybody who is independent and critical-minded win office above a certain level,” says Ms. Lipman. “Even though the Moscow city council has limited authority, it seems to be the cutoff point. ... The status of city councilor gives much more access to government documents, institutions, and procedures. The Kremlin wants to make sure this level is free of such ‘troublemakers.’”

That stirred the protests – the largest since Russia’s last protest wave seven years ago – which seemed to blindside Moscow authorities with their size. The first permitted one, on July 20, attracted about 20,000 people. After three weekends of police violence against spontaneous protesters, the second allowed rally on Aug. 10 drew up to 60,000 people.

That may be small compared with the city’s population of 12 million, but it points to an often overlooked fact. Moscow, as the dynamic intellectual, cultural, and business center of Russia, has a very high proportion of highly educated, worldly professionals – the sort of people who tend to be liberal-minded just about everywhere.

Over the course of the Putin era – now 20 years old – this professional class has benefited from radical expansion of popular living standards, impressive improvements in social services and infrastructure, and even brisk growth in non-political civic activism. And during the past several years in Moscow, the city’s technocratic government has re-made the landscape, building new parks, roads, metro lines, and has greatly improved public services – to the benefit of the Muscovite professionals.

The trade-off is that their ability to influence politics is greatly curtailed. For example, critics point out that Moscow’s massive infrastructure projects are decided upon with very little public consultation, and the process of awarding contracts is nontransparent, favoring city-owned and politically friendly businesses.

“On one hand, zero tolerance for any kind of political activism and brutality toward anyone violating that, and on the other hand turning Moscow into a modern, comfortable and more livable metropolis,” says Ms. Lipman. “Nobody is against these improvements. But many people were profoundly offended by [the recent] egregious and unlawful abrogation of their rights.”

A compelling alternative explanation for the protests has been put forward by sociologist Olga Zeveleva, who suggests that it is down to “Putin millennials,” or young people who have grown up knowing no leader but Mr. Putin, have no memory of the catastrophic 1990s that preceded the current era, and are impatient for change.

There may be something in that, but surveys taken at Moscow’s two permitted rallies found that just half of participants were under 33 years old and “it cannot be said that they were mainly schoolchildren or even students.” More than 80% of protesters were permanently registered Muscovites, contradicting official claims that out-of-towners were mainly responsible for the demonstrations.

The limits of Russian democracy

As in the previous cycle of protests against election fraud, the current wave is probably limited by its social base. Urban professionals are willing to take to the streets over an issue of basic democratic rights such as this. But Russia’s liberal opposition, including anti-corruption crusader Alexei Navalny, have thus far seemed unable to forge connections with the broader masses of Russians, or even Muscovites.

Surveys suggest that many more Russians are growing restive after several years of stagnating incomes and slow economic growth, and disenchanted with their government, but their priorities lie more with bread-and-butter issues. Indeed, Vladimir Putin has so far proved far more adept at talking to the working class about their primary concerns.

One more optimistic note is suggested by Boris Kagarlitsky, a veteran Russian leftist and Kremlin opponent. He is running for city council on the ticket of the Just Russia party, one of Russia’s so-called “systemic opposition”: more-or-less loyal parties that already have representation in legislatures at all levels. Candidates nominated by such parties do not have to undergo the onerous signature-gathering and other bureaucratic ordeals that independent candidates must face to get on the ballot.

“There are a lot of new, critical-minded people running in local elections all over Russia this year who are nominated by Just Russia or the Communist Party, and who stand good chances of getting elected,” Mr. Kagarlitsky says. “The irony is that this brutal behavior by Moscow authorities is such a scandal, and has angered so many, that people are going to come out and vote this time – few usually bother with local elections – and they are going to vote for anybody except the pro-government candidates.

“There is a good chance that these elections are going to be disastrous for the government, not despite their clumsy efforts to control them, but because of it,” he says.

But Ms. Lipman says the protests themselves, dramatic as they are, lack organizational staying-power.

“There is nothing in terms of a movement that people can identify with in the long term. When the wave subsides, as it did before, it leaves nothing behind in terms of political organization and trusted leaders to sustain it,” she says.

“Of course nobody wants a revolution. People are rightly leery of any big-time political turmoil. Evolution is preferable. But I don’t see much prospect on the horizon of reaching a society of law, checks and balances, and democracy. I don’t think I will live to see it.”

Confederate statues and the future of America’s past

“The past is never dead,” William Faulkner wrote. “It’s not even past.” Many communities are wrestling with that lesson today, as they debate what to do with Confederate monuments – underscoring how their meaning is shaped by the 21st century as much as the 19th.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Erected in 1911, Atlanta’s Peace Monument depicts a winged goddess calling to a Confederate soldier, “Cease firing – peace is at hand.”

Is that a representation of reconciliation – or oppression? Vandals defaced the monument in 2017 after a violent white supremacist march in Charlottesville, Virginia, sparked nationwide protests.

This month, Atlanta added an explanatory plaque at the Peace Monument site, saying the monument “should no longer stand as a memorial to white brotherhood,” its original intention.

Two years after Charlottesville, many locales continue to struggle with how to properly present Confederate statuary.

In Georgia and other former Confederate states, state laws prohibit monuments from being removed. That’s led cities to look for ways to better explain the stone monuments and their role in history.

Atlanta is beginning with a quick approach: plaques. Besides the Peace Monument, it has added signs at the “Lion of the Confederacy,” a stone statue in a city cemetery.

Even writing a plaque can be a fraught process. But officials say the important thing is that just addressing the issue can bring history to life.

“These statues are no longer static. They are now evolving,” says Sheffield Hale, president of the Atlanta History Center.

Confederate statues and the future of America’s past

Put up in 1911, the Peace Monument in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park features a winged goddess calling to a Confederate soldier: “Cease firing – peace is proclaimed.”

At the time, the monument was meant not to glorify the Confederate cause, but to urge reconciliation, a rekindling of a national bond stretching from Atlanta to Boston. It was built to commemorate peacekeeping trips to the North made by members of the Gate City Guard, Georgia’s first militia, in previous years.

But 2019 is different historical country than 1911. What seemed progressive then can today strike some as an oppressive symbol. Vandals defaced the monument following the August 2017 violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, where a “Unite the Right” rally clashed with counterprotesters.

Atlantans suddenly faced some thorny questions, says Sheffield Hale, president and CEO of the Atlanta History Center: “Why is a peace monument a problem? What’s wrong with peace?”

This month, the city of Atlanta installed a sign that presents one answer: the memorial’s idea of reconciliation excluded African Americans. “This monument should no longer stand as a memorial to white brotherhood; rather, it should be seen as an artifact representing a shared history in which millions of Americans were denied civil and human rights,” the sign states.

Two years after the Charlottesville march and its aftermath, states, cities, and citizens all across America continue to struggle with how to handle and interpret the artifacts of the past in the present day.

In that struggle, different narratives clash with modern distributions of power. Conservative Southern state legislatures have passed laws protecting historical monuments, including Confederate statuary. More liberal local jurisdictions are trying to rethink and reframe the meaning of these relics by surrounding them with context, including explanatory material such as signs and plaques.

The result, as in Atlanta, is a riveting and consequential debate that is about where the nation is going as much as where it has been.

“We are in the process toward a dream,” says William Ferris, associate director of the Center for the Study of the American South, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “These statues are markers along the way of how we address both the past and the future as a people. It is an ongoing conversation that in the 21st century is taking an interesting turn as the country is becoming predominantly nonwhite.”

Monumental contested meanings

Richard Straut is one of the Atlanta Peace Monument’s sworn protectors. He has a different view of its meaning than that expressed by its new accompanying sign.

The former Atlanta detective spent a career in both the police and military working for and with African Americans. He is a former commandant of the Old Guard of the City Guard, entrusted with the monument’s care. The Old Guard’s patch – a boar's head with an oak leaf in its mouth – now decorates the state National Guard uniform.

“I’m a soldier in the Old Guard, the precursor to our National Guard,” says Mr. Straut in a phone interview. “It is integrated. We are not some white supremacist nonsense.”

In 1911 the Old Guard wasn’t trying to undermine the government in the United States with a peace monument that referenced a Confederate soldier, according to Mr. Straut.

“It was trying to bring the brotherhood back together again, and we succeeded. We are equal. And all races are involved,” he says.

The Peace Monument is far from the only memorial whose meaning is contested today, of course. From small town squares to battlefields, the South is strewn with stone memories.

They range from innocuous cemetery markers to obvious paeans to the Confederate Lost Cause, including 75 “Johnny Reb” statues – most crafted after Reconstruction in Northern forges – that stand in public places, by intent, as sentinels of white power.

As of February 2019, 114 Confederate monuments have been taken down since the 2015 attack on a Charleston, South Carolina, church by white supremacist Dylann Roof, including General Robert E. Lee from Lee Circle in New Orleans and Ku Klux Klan founder Nathan Bedford Forrest from a park in Memphis. Some 1,747 still stand, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Many of these monuments are shielded from removal or extensive alteration by state laws passed in the former Confederate states, including Georgia, according to the SPLC. Some cities in these states are challenging the legality of these restrictions. Norfolk, for instance, has sued Virginia to lift the state’s removal ban.

Other localities are focusing on adding context. But that process itself is difficult. What to say? How to say it? What is the context here, after all?

“It doesn’t surprise me that communities are struggling to some extent with conceptualization, because the writing of new inscriptions is always extremely contentious,” says Kirk Savage, author of “Monument Wars.”

For its part, Atlanta has tried to move quickly, adding low-cost, fact-based panels that contextualize memorial presence, and bottom-line their intent.

“It is a process to turn them from public statues to outdoor museum exhibits, from statement to artifact,” says Mr. Hale of the Atlanta History Center. “And it is recognition that these are not Civil War monuments. They are Jim Crow monuments.”

Similar discussions – sometimes heated, often thoughtful – are taking place across the South as more and more Americans realize the monuments “are connected to what is happening to me in the present day,” says Mr. Savage, a University of Pittsburgh art historian.

The process of contextualization can be fraught. But inaction can have consequences. The failure of the University of North Carolina to heed calls to contextualize its Confederate “Silent Sam” statue on campus may have helped lead to a mob toppling the statue in 2018.

“We started from a premise of some are going to come down, some are going to stay up, but ... what is next is the really important question: How do we start something that is actually more democratic and more representative and more empowering for people than the old monument system, which is an elite-driven system that almost always tends to reflect the power relations on the ground?” says Mr. Savage. “Our political climate has made it a much more urgent issue.”

“The statues are no longer static”

Americans seem at a wary impasse over the Confederate monument issue, polls say.

In the South, a majority of white Americans want the monuments to stay, and a majority of black Americans want them removed, according to a Winthrop University poll. Overall, a plurality thinks they should remain. There is little agreement about how, or whether, to contextualize them.

Meanwhile, majorities of both black and white Americans agree that race relations in the U.S. are worsening, according to the Winthrop survey.

That raises the stakes for questions about monuments being pondered in places like Decatur, Georgia; Savannah, Georgia; Norfolk, Virginia; and Richmond, Virginia. Richmond’s Monument Avenue features famous statues of Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis. The city’s Valentine Museum is currently exhibiting dozens of conceptual drawings of what could be done with the statues, including one idea to bury them to their heads.

“The question for us has become, what does contextualization really mean?” says Bill Martin, the museum’s director. “And that becomes a jumping-off point for a conversation that needs to happen.”

Two years ago, in Charlottesville, a blue ribbon committee’s decision to remove a Robert E. Lee statue sparked the “Unite the Right” rally. It devolved into a riot and street fight that left dozens injured and one dead.

The national tragedy at Charlottesville made clear to many Americans that the nation’s legacy of white supremacy had burst into the present, and that white supremacists looked at Confederate statues as symbols of their ideology.

As newspaper reporters flocked to the city, religion professor Jalane Schmidt began holding informal tours of the statuary. The tour continues on a monthly basis, drawing upwards of 100 people at a time.

Ms. Schmidt says she didn’t realize until after she began researching that over half of the residents of Albemarle County, where Charlottesville is located, were African Americans the year the Lee statue went up. And her research showed that its installation had little to do with commemoration of soldiers, and much to do with a “lost cause mythology” that advocated a national white brotherhood to thwart the political power of black Americans.

“These statues of metal look like mute monuments, but as we found out they are distilled hatred,” says Ms. Schmidt. “They are sending a message of complete disregard for the humanity of black people.”

Just a few miles from the Peace Monument in Atlanta is “the Lion of the Confederacy,” a stone representation of a lion in repose, clutching a Confederate battle flag. The sleeping royal feline guards hundreds of slain Confederates, including an ancestor of Martin O’Toole’s.

Mr. O’Toole is a former newspaper editor, an amateur historian, and a spokesman for the Georgia Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Last week, he made his first visit to the “Lion” monument after a contextual plaque was added.

Armed with a camera to document the changes, he immediately spots what he thinks is a mistake. A title says “Lion of Atlanta.” The statue is actually called the “Lion of the Confederacy,” Mr. O’Toole says.

He notes that Georgia nearly undermined the Confederacy as its key leaders backed national unity in the 1850s. So what happened? News in the South that church bells had pealed in New England in support of abolitionist John Brown’s 1859 raid at Harpers Ferry meant that sectional disputes had morphed into “a dangerous moment for Southerners,” says Mr. O’Toole. “They were suddenly afraid for their lives. They had to fight.”

But even as he quibbles with the Lion’s new explainer, he notes, “I’m OK with the panels. They are mostly fact-based and within the law. I just say thanks to the legislature for passing a law to make sure the Lion is still here. Or else it most assuredly would be gone.”

Atlanta’s confederate statues will stay, at least for now. But all around them, the conversation has shifted, and history, for many, suddenly seems alive – evoking both danger and hope.

“What is important is that these new panels are not permanent,” says Mr. Hale, as park-goers gather to read the new panels. “We can change the words. We can add more panels. But that’s the point. These statues are no longer static. They are now evolving.”

Film

US immigration and families: A tale from the Holocaust era

Immigration policy usually speaks to a nation’s values. In her historical documentary “Nobody Wants Us,” filmmaker Laura Seltzer-Duny wants to “help create empathy for refugees – then and now.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

It didn’t look promising in 1940 when 83 mostly Belgian Jewish refugees aboard the SS Quanza hoped to gain asylum in the United States. Isolationism was flaring, and opposition to admitting any refugees was dominant. But after a chain of events that included the intervention of Eleanor Roosevelt, the passengers were granted entry into the U.S.

The story of the SS Quanza is told in “Nobody Wants Us,” a documentary by filmmaker Laura Seltzer-Duny that had its New York premiere this month. The film lays out the details that underpin a conviction among Holocaust researchers that the Quanza was something of a miracle – and not only because this ship’s refugees were allowed into the U.S. while hundreds of thousands of other Jews were turned away. The documentary also underscores the tenacity of a few key individuals without whom the Quanza’s fortuitous outcome would not exist.

But for Ms. Seltzer-Duny, the real purpose of her project is to encourage viewers, especially young people, to relate history to events taking place now. “I very definitely set out,” she says, “to tell a story that would open people’s eyes to what’s going on today.”

US immigration and families: A tale from the Holocaust era

Well into her retirement years, Annette Lachmann enjoys a happy and active life, teaching critical writing at a New York community college and spending time as a doting grandmother.

The flood of migrant and asylum-seeking families across the U.S.-Mexico border might seem to be worlds away from that of the comfortable Upper West Side octogenarian.

But news of families detained in fetid conditions and, above all, of infants and small children being separated from their parents took Ms. Lachmann back eight decades, and pierced her heart.

In the summer of 1940, a 3-year-old Annette was the youngest passenger on the SS Quanza, a ship whose passengers included 83 mostly Belgian Jewish refugees fleeing an increasingly menacing Europe and hoping for asylum in the United States.

But the Quanza arrived in an America where isolationism was flaring and where opposition to admitting any refugees – least of all Jewish refugees who, it was thought, might be communists and terrorists – was dominant.

“The ship was hot and smelly, I remember that, but I was glued to my mother the whole time; at least I had that,” says Ms. Lachmann. “So I think of those children down at the border being separated from their parents, from anyone they know and trust, and I feel I have some idea of how traumatized they must be – even though,” she adds, “for them it must be 10 times worse.”

If Ms. Lachmann has her happy American life today, it is because the unwanted passengers of the Quanza were finally granted entry into the U.S. – but only after a chain of events that included the relentless intervention of Eleanor Roosevelt. Over a few critical days in September 1940, Mrs. Roosevelt would press her husband, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on behalf of the ship’s refugees and in opposition to the powerful and fiercely anti-immigrant assistant secretary of state, Breckinridge Long.

The story of the SS Quanza is now being told in “Nobody Wants Us,” a documentary by the Washington, D.C., filmmaker Laura Seltzer-Duny.

Individuals who made a difference

The 35-minute film lays out the details that underpin a conviction among Holocaust researchers that the Quanza was something of a miracle – and not only because this one ship carrying 83 refugees was allowed into the U.S. while hundreds of thousands of other Jews were turned away. (A year earlier the U.S. turned away the MS St. Louis, carrying more than 900 Jewish refugees. Historians have determined that at least a quarter perished in Nazi Germany death camps.)

The film also underscores the tenacity of a few key individuals – from a Portuguese consul in France who issued thousands of visas to desperate Jews despite his government’s orders, to a married couple, both Virginia lawyers, who used maritime law to stall the ship’s return to Europe – without whom the Quanza’s fortuitous outcome would not exist.

The film also includes comments from Ms. Lachmann and features a heartbreaking photo of the tiny 3-year-old reaching through one of the Quanza’s portholes to her father, who was already in the U.S. but was not allowed to board the ship to see his family.

But for Ms. Seltzer-Duny, the real purpose of her project is to encourage viewers, especially young people, to relate history to events taking place in their country today.

“This has so many important messages for everyone across our country,” she says, tapping the DVD copy of “Nobody Wants Us” that she holds in her lap. “But my passion is getting this film into schools to help create empathy for refugees – then and now. I very definitely set out,” she adds with a smile, “to tell a story that would open people’s eyes to what’s going on today.”

This week the Trump administration moved to abolish a decades-old court agreement that put a cap on how long the government can hold migrant families and children entering the country illegally. The new regulation would allow for indefinite detention of families and children and scrap minimum standards that the old ruling set for detention conditions.

A former TV producer, Ms. Seltzer-Duny says she has seen too many of the “worthy” stories she has told and issues she has taken up in documentary films over the last 20 years get too little play. For the Quanza’s story, she turned to New Day Films, a filmmaker-run distribution company that places films in libraries, universities, and junior high and high schools, and assists filmmakers in developing educational materials to accompany their films.

Screenings of the film

So far, “Nobody Wants Us” has mostly been shown in Jewish cultural centers – the film’s New York premiere this month was held at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan. (The event was also a fundraiser to help underwrite the cost of placing the film in schools.) But it is slated to be shown in November at the University of Richmond law school, where the theme of the evening will be the legal issues confronting the Quanza – and immigration today.

Also in November, the film will be featured in Orange, Connecticut, at an evening focused on “heroism” – with plans for Sen. Richard Blumenthal to present congressional citations to family members of some of the Quanza heroes.

“The story of the Quanza involved a lot of people and different heroes,” says Stephen Morewitz, a California State University behavioral scientist and forensic sociologist whose grandparents, J.L. and Sallie Rome Morewitz, were the Virginia couple who used maritime law to slow the Quanza’s ordered departure.

“They were definitely heroes to the refugees of the Quanza, and through their efforts they demonstrated the important lesson that individuals can make a difference,” Dr. Morewitz says.

But he adds that their “victory” was no doubt “bittersweet” for both his grandparents and Mrs. Roosevelt, since after the Quanza “the door slammed shut.” Indeed, immigration and refugee admissions into the U.S. essentially fell to zero until 1944. (The film notes that FDR, facing reelection in an isolationist country in 1940, was anxious not to be seen as either pro-immigrant or pro-Jewish.)

Another hero of the Quanza saga was Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the Portuguese consul in Bordeaux, France. In the years leading up to World War II, he disobeyed his government’s orders by issuing 30,000 visas to persecuted Europeans, 10,000 of whom were Jews.

Making “ourselves uncomfortable”

One lesson these tales of heroism teach is that “sometimes we need to make ourselves uncomfortable,” says Ms. Seltzer-Duny. “God knows Sousa Mendes made himself uncomfortable – he saved more than 30,000 people, but he died a pauper.” The New York screening of the documentary was sponsored by the American Sephardi Federation and the Sousa Mendes Foundation.

Ms. Seltzer-Duny is working on a longer version of “Nobody Wants Us” that will air on PBS and be entered in film festivals next year – the 80th anniversary of the Quanza story. But she says her chief goal is to place her film and accompanying educational materials in junior high and high schools – especially those with little or no mention of the Holocaust in their curriculum.

Earlier this year she screened “Nobody Wants Us” for history and government teachers in Newport News, Virginia – her hometown and the port city where the Quanza drama unfolded – with a number expressing interest in incorporating the film into their classes.

“I think the road to encouraging young people’s empathy with refugees today passes through understanding history and how we acted towards refugees in the past,” the filmmaker says. At the end of the documentary, as the credits roll, she includes cameos of teenagers from a Jewish community center and a Muslim school talking about immigrants and refugees.

Ms. Lachmann agrees that the story of the Quanza, as well as how it illuminates the conditions that immigrants and refugees face in the U.S. today, needs to reach young people. But her explanation as to why is more succinct.

“We have to learn and try to be better, because history repeats itself,” she says. “It does, but we have to fight it.”

Difference-maker

Job training that puts people – and their community – back on track

Social service organizations can be a lifeline for individuals who are struggling. But Marvin DeJear’s Evelyn K. Davis Center shows that they can strengthen whole communities – one person at a time.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By David Karas Correspondent

Each year, some 7,000 men and women turn to the Evelyn K. Davis Center for assistance with everything from job readiness support and career opportunities to financial coaching and educational support.

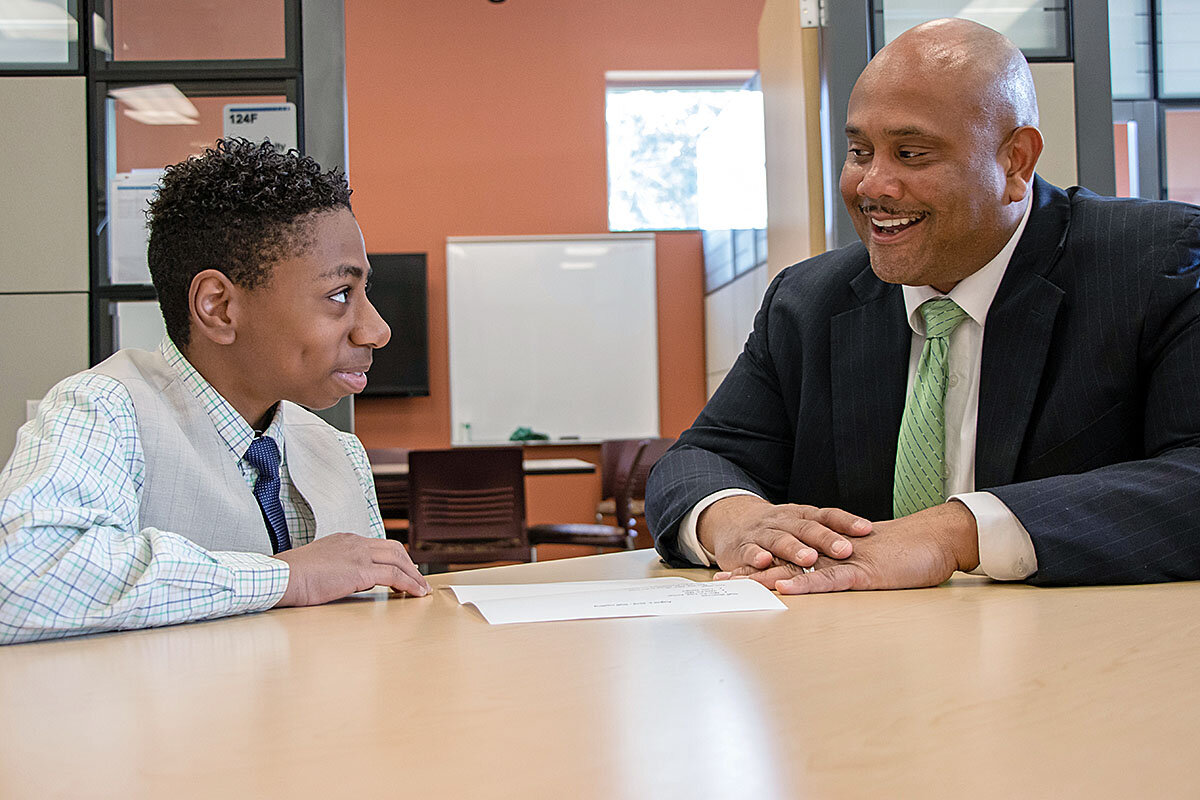

At the center of that effort stands Marvin DeJear. He has been with the center since its founding in 2012, initially serving as operations manager before taking the helm as director.

“I consider us like an airline hub,” says Mr. DeJear. “We help people catch the connecting flights to change their life.”

Under his direction, the center has become a one-stop shop that helps connect clients of all ages and backgrounds to the resources necessary to help them better their lives.

Those efforts to support individuals add up to strengthen the entire community, says Reeva Neighbors, a client who has taken advantage of many of the center’s services. “What the center does for the city of Des Moines,” she says, “is show the community that no matter where you are in life, there is always a way up.”

Job training that puts people – and their community – back on track

Reeva Neighbors was already feeling stretched thin when she needed to help her mother through multiple health issues in 2014.

Ms. Neighbors, who is herself the mother of three children, was also taking online courses, but lacked internet access. But she knew where to turn: the Evelyn K. Davis Center for Working Families.

The center’s free computer lab ensured she could get her homework done and stay in school while juggling her dual caregiving responsibilities. That’s just one example of how the Evelyn K. Davis Center has helped to keep her afloat when life has started to feel overwhelming.

“The center has helped me over the years in so many ways, from using the computer lab and meeting with the job development team, to the financial department helping me get on a budget that was right for me,” Ms. Neighbors says in an email interview. “I am stable and paying off my student loans with no issue, and now have a job. I am very thankful for everything that the center has done, not only for myself, but also for my family and the people of my community.”

Each year, some 7,000 men and women like Ms. Neighbors come to the Evelyn K. Davis Center for everything from job readiness support and assistance with career opportunities, to financial coaching and educational support.

At the heart of that effort stands Marvin DeJear. He has been with the center since its founding in 2012, initially serving as operations manager before taking the helm as director. Under his direction, the center has become a one-stop shop that helps connect clients of all ages and backgrounds to the resources necessary to better their lives.

Every step of the way

“I consider us like an airline hub – we help people catch the connecting flights to change their life,” Mr. DeJear says in a phone interview. “We really focus on meeting people where they are at, and helping them find a game plan to help them accomplish whatever goals, dreams, or desires that they have had.”

Center staff work with clients to individualize those game plans. They might include education and employment assistance or one-on-one counseling from a job developer to define skills, craft a résumé, and identify job opportunities. The center organizes career fairs and offers assistance with professional attire, along with support for housing, utility, and transit expenses to help set clients on the path toward self-sufficiency. Clients can enroll in classes in digital literacy, parenthood, and a range of other topics.

Mr. DeJear sees clients who are homeless, some who are reentering society, and many more who are looking to improve their lives and the lives of their families.

“It could be somebody who has really hit rock bottom,” he says. “And then we have some who have the talent, have the skills and training, but just need help with a résumé.”

The center also provides intensive, individualized financial coaching that encompasses budgeting, credit repair, loan readiness, and more.

“We can take people from debt reduction and credit repair all the way to helping them buy a house, build up their three to six months of savings, [and] help them buy a car,” says Mr. DeJear. “We help them every step of the way.”

Holistic support

Mr. DeJear has always been a person who has enjoyed helping others, and was drawn to the center when changing careers after a successful stint with his general contracting company. He has also spent time teaching working adults at William Penn University, and volunteering to provide financial coaching to students at Iowa State University.

His role doesn’t feel like work, he says, but rather a way to continue helping others. And he is passionate about the challenges they face.

“I don’t think people realize what it really looks like for people on the ground day to day,” he says. “Forty to 50% of Americans can’t handle a $300 or $400 emergency. This work is critical to make sure people have a real chance of being successful moving forward.”

The center is open to anyone – and clients include students at the Des Moines Area Community College as well as residents throughout the region. Although it was initially established to assist those in the urban core of Des Moines, its reach has far exceeded those boundaries.

“We have helped people in 13 ZIP codes, compared with the original 10 neighborhoods this collaborative idea was built around trying to help,” says Mr. DeJear.

A core component of the center’s model is the offering of holistic support – a model that Mr. DeJear credits for much of its success.

“You are really focused on helping people and making sure they have the opportunity to have that [improved] quality of life,” he says. “It is just the reality that people need these things to move forward in a lot of areas.”

Bolstering the community

On a rainy Friday morning at the center, career coach and job developer Terrance Cheeks was settling in for the day. He worked for the state of Iowa in workforce development before joining the center two years ago, and now he helps clients with résumés and job searches.

“We think it is important for everyone to have a career,” says Mr. Cheeks, who adds that they want clients to become self-sufficient, and not have to live paycheck to paycheck.

Assistant director Joy Esposito, who has been with the center for four years, emphasizes the approach of the entire staff with new clients.

“When people come through the door, it is our responsibility to listen to them and try to match our services with their needs,” she says while walking through the center, passing by classrooms and offices. “When they leave here, they are feeling a little more hopeful than when they came in, and that is vital to the work that we do.”

The organization’s client base continues to grow year after year, a testament to the level of need in the community. As clients’ needs shift, Mr. DeJear works to develop new programming, says Kristi Knous, president of the Community Foundation of Greater Des Moines, which played a key role in establishing the center.

“He is changing lives, one by one, and is changing our community for the better,” she says.

Ms. Neighbors has felt that ripple effect throughout the community firsthand.

“What the center does for the city of Des Moines,” she says, “is show the community that no matter where you are in life, there is always a way up.”

For more information, visit www.evelynkdaviscenter.org.

Hail this taxi, but hold on tight – boda-bodas swarm Kampala streets

When urban planning, laws, and enforcement lag behind community needs, people find their own solutions. But the problems might just get bigger.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

If you’re trying to get someplace in Kampala and you have less than a couple of hours to spend in traffic, a nimble boda-boda motorcycle taxi might be your best option. It’s a mode of transportation in Uganda’s capital that has grown to employ hundreds of thousands of drivers. “Boda-bodas are a necessary evil,” says Sam Mutabazi, head of an NGO promoting urban planning.

Swarms of motorbikes gather at major intersections, revving their engines like angry hornets. Individual riders thread their way between bumpers and between lines of traffic, or they take to the sidewalk, or simply ride into oncoming traffic. Entrepreneurial solutions like the SafeBoda app – which briefly trains drivers and provides helmets for them and their passengers – are attempting to make the chaotic rides less dangerous.

But the time may soon come when even this remedy proves impossible. In the absence of an organized mass transit system (public transport in Kampala means thousands of 14-seater minibuses) or any plan to transfer jobs to satellite cities, the situation seems likely to worsen. “The problem is that the government’s short- and long-term plans are not clear,” Mr. Mutabazi says.

Hail this taxi, but hold on tight – boda-bodas swarm Kampala streets

If you want to get across town quickly in traffic-clogged Kampala, you need a hairnet.

A 10-mile car commute in the Ugandan capital routinely takes two hours. Or you can jump on one of the city’s ubiquitous boda-boda motorcycle taxis. Safety is not their strong point, but drivers with the ride-hailing app SafeBoda at least provide passengers with a helmet. And – for reasons of hygiene – a disposable hairnet.

“Boda-bodas are a necessary evil,” says Sam Mutabazi, head of the Uganda Road Sector Support Initiative, a nongovernmental group promoting urban planning. “If you are stuck somewhere and you have urgent business, you can just leave your car and take a boda-boda” that can weave its way through the thickest of jams.

But the time may soon come when even that remedy proves impossible. In the absence of an organized mass transit system (public transport in Kampala means thousands of 14-seater minibuses) or any plan to transfer jobs to satellite cities, the situation seems likely to worsen. “The problem is that the government’s short- and long-term plans are not clear,” Mr. Mutabazi complains.

Kampala has a population of 1.8 million; another 1.7 million pour into town each morning and leave each evening in an orgy of congestion. About 70% of the country’s economic activity is concentrated in the capital, and the authorities are not considering moving any government offices or businesses into the suburbs.

With the capital’s population predicted to rise fivefold by 2040, to 10 million inhabitants, “we will have a static city where people will be spending most of their time in traffic jams” unless a solution is found, warns Mr. Mutabazi.

The government has begun work on a mile-long overpass in the center of the city, but Mr. Mutabazi does not expect that to significantly reduce the pressure. “It’s just adding more concrete to a built-up city, dropping a brand-new road into a ramshackle network,” he argues.

In the meantime, boda-bodas rule the road, and there are an estimated 300,000 of them in Kampala. Swarms of motorbikes gather at major intersections, revving their engines like angry hornets. Individual riders thread their way between bumpers and between lines of traffic, or they take to the sidewalk, or simply ride into oncoming traffic.

You are taking your life in your hands when you take a boda-boda: A 2010 study at Kampala’s Mulago hospital, the largest in the country, found that 75% of patients admitted for trauma injuries sustained in traffic accidents had been involved in boda-boda crashes.

That has prompted a number of companies, including Uber, to get into the boda-boda business and offer clients a little more security, which has upset independent drivers, who are fighting government efforts to regulate them: The boda-boda Joint Leadership Forum recently complained about Western “companies that are engaging in the management of our boda-boda sector with unknown intentions.”

And elsewhere in Africa, Uber has come under fire for allowing its drivers to ride unsafe bikes. Six Uber Eats motorcycle drivers have died in accidents since 2017 in Cape Town, South Africa, according to an investigation by the website GroundUp, a public interest news agency in Cape Town.

The most visible of the Kampala ride-hailing apps is SafeBoda, whose drivers wear fluorescent orange vests emblazoned with their names, as well as distinctive orange helmets.

Julius Wandera, a friendly young man, has been driving for SafeBoda for six months on an Indian-made 100cc Bajaj Boxer bike, a popular model in the boda-boda world. He says he wasn’t being paid well at the shop where he worked before; today he can make between $10 and $12 a day. “It’s not a lot, but it’s for starters” as he gets into the business, he says. He could earn more, but he stops driving at 7 o’clock. “It’s scary riding at night.”

How does a SafeBoda driver differ from a traditional independent? Mr. Wandera did a daylong class to learn and rattles off the rules. “You have to follow the traffic lights, you mustn’t ride carelessly, you can carry only one passenger, you have to have a driving license, your bike must be in good condition, you must have discipline, you must not drink, and you must know how to speak English.”

Then he has an afterthought. “Oh, and you are not supposed to go the wrong way up one-way streets.”

The chaos that ensues when the large majority of boda-boda riders, not attached to any ride-hailing app, are not following such rules is frightening. And even for SafeBoda drivers, overtaking on the inside is standard practice.

Uganda’s long-standing president, Yoweri Museveni, has mooted a ban on boda-bodas, suggesting they should be replaced by the three-wheeler tuk-tuks so familiar in India and Southeast Asia, but it seems unlikely he was serious.

It is hard to see how the plan might ease congestion, since tuk-tuks take up more room than motorbikes. On top of that, points out Mahmood Mamdani, director of the Institute of Social Research at Makerere University in Kampala, an army of hundreds of thousands of young men with similar outlooks and similar aspirations could prove to be a volatile force.

“Museveni sees boda-boda drivers as a political constituency,” Professor Mamdani says. “They are untouchable.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Natural motivators for plastic bans

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The South Pacific nation of Vanuatu was the first country to ban plastic drinking straws. It also joined dozens of other countries that have restricted use of plastic shopping bags. Yet where Vanuatu really stands out is how its leaders pitched this environmental cause. They played up potential gains in economic benefits, cultural traditions, and other aspects of social well-being. It was a reminder to environmentalists of the limits of using fear and loss as sole motivators to change personal behavior or badger governments into action.

The morality of an environmental cause lies not in what it is against but what it is for, especially values that elevate people’s thinking. A recent study at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia looking at 39 pro-environmental behaviors found 37 were linked to life satisfaction.

This approach isn’t positive thinking. Rather it is positive results, or just the kind of pitch that Vanuatu promised and is delivering in its plastic bans.

Natural motivators for plastic bans

A year ago, the South Pacific nation of Vanuatu become the first country to ban plastic drinking straws. It also joined dozens of other countries that have restricted use of plastic shopping bags. And later this year, it will again be a global leader with a ban on disposable diapers that include plastic material. It certainly deserves credit for taking these steps, especially as they spurred other Pacific nations to follow suit.

Yet where Vanuatu really stands out is how its leaders pitched this environmental cause.

Yes, they cited the plastic pollution washing up on Vanuatu’s shores, choking both wildlife and tourism. The country’s nearly 300,000 people spread over 65 islands could easily notice such problems. Leaders also spoke of the need for collective sacrifice and daily inconvenience, especially for parents who will have to give up their current type of diapers. And yes, resistance to the bans continues.

But what they really played up well were potential gains in economic benefits, cultural traditions, and other aspects of social well-being. It was a reminder to environmentalists of the limits of using fear and loss as sole motivators to change personal behavior or badger governments into action.

Vanuatu is still tallying up the benefits to its economy from the bans, especially in tourism. But it has already seen one effect: the revival of traditional woven bags made of natural fiber to replace plastic bags. “The more we use them, the more we encourage our cultural art of weaving, in turn strengthening the cultural heritage of Vanuatu,” says the country’s first lady, Estella Moses Tallis. The country has become an innovator in finding many alternatives to plastic, notably in trying to design biodegradable diapers. One inventor has created water taps made of bamboo instead of plastic pipes.

Too many eco-causes are framed as a choice between self-interest and the greater good of society. “It worries me to see pro-environmental action being equated with personal sacrifice,” says Kate Laffan, a behavioral scientist at University College Dublin. She says a growing body of research suggests that, rather than posing a threat to individuals, the adoption of a more sustainable lifestyle “represents a pathway to a more satisfied life.”

The morality of an environmental cause lies not in what it is against but what it is for, especially values that elevate people’s thinking. A recent study at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia looking at 39 pro-environmental behaviors found 37 were linked to life satisfaction.

This approach isn’t positive thinking. Rather it is positive results, or just the kind of pitch that Vanuatu promised and is delivering in its plastic bans.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Purposeful retiring – at any age

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Diane Marrapodi

However many changes we make in our lives, we never retire from God’s goodness and vitality. Everyone is capable of experiencing this, right here and now.

Purposeful retiring – at any age

Whether we’re dreading retirement or approaching it with a heart full of cherished hopes and dreams, our concept of it is generally centered around one thing: removing ourselves from work. The word typically refers to leaving one’s job; its unintended consequences, however, often seem to include loneliness, isolation, obscurity – a state which may leave something to be desired.

Thankfully, there is a broader sense of retirement that is worth considering. When Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy retreated from society for about three years following her discovery of Christian Science, she said it was “to ponder my mission, to search the Scriptures, to find the Science of Mind ... and reveal the great curative Principle, – Deity” (“Retrospection and Introspection,” pp. 24-25). She retired for the sole purpose of going up higher in her understanding of God, the divine Mind.

This type of retirement enabled her to withdraw from cultural restrictions on women and from myriad beliefs that hold back humanity. She grew in her understanding of the scriptural explanation of God as ever-present divine Love, who fully directs and governs man and the whole of creation.

This understanding did not occur all at once. It dawned in consciousness, was carefully and prayerfully considered, and was then applied with healing results: She repeatedly proved that the divine laws of God are always available and able to liberate the sinning, sick, and dying.

Through earnest study of the Bible, she learned from the examples of its faithful people, particularly Christ Jesus, how to retreat from worldly concerns to gain higher views of divinity. Mrs. Eddy says of his example, “Jesus prayed; he withdrew from the material senses to refresh his heart with brighter, with spiritual views” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 32).

Jesus’ moments of withdrawal from the clamor of torment and hatred – up into a mountain, into a ship, into the garden of Gethsemane – were not a retirement from care and duty; they were moments of selfless surrender to God’s will in order to gain strength and inspiration for his work of teaching and healing. He withdrew to go up higher in his understanding and demonstration of God.

And he showed that the law of Love is universal, now. There is no waiting to be free over a period of time. What a blessing it is to know you do not have to wait to be of a certain age before retiring or retreating from adversity!

And if you are past what is commonly considered retirement age, there’s no law that says you have to cease working. One woman, well past that age, was often told she should close the private school she owned and retire. Yet she felt a strong commitment to the children’s education. Understanding that divine Life, God, is pure, perfect, and infinite in scope and capacity, and that all of God’s children fully and eternally express this Life, she was never burdened by a sense of heavy labor.

So she retreated – from the prescribed customs or social mores of her day. She refused to agree with being too old, too frail, or needing to accommodate the “sunset years.” Instead, she relied on God-derived, God-endued vitality, well-being, strength, and productivity. She kept teaching and running her school for many years.

Whether or not we retire in the conventional sense, there is no retreat from Life, because we forever express the Life that is God as our very own nature. On this basis, we can overcome limitations of material thinking and living. We can see that retirement isn’t based on a calendar or a geographical change, and needn’t be characterized by unwanted solitude, or obscurity. Heaven forbid! Its blessing is not in creating a new life after a certain age but about discovering and defending our right to experience more of our God-given life all along the way. With each new view of God, Life, we can have a fresh experience, make progress, contribute, and discover health.

However many changes we make in our lives, we never retire from God, Life, and His goodness and vitality. Through prayer, we can discover God’s plan of infinite good, well-being, and service, and feel the ever-present divine Love that sustains us in challenging moments.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Aug. 19, 2019, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Let it shine

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow when our series on the oceans continues with a piece about the connection between the deep sea and outer space.