Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

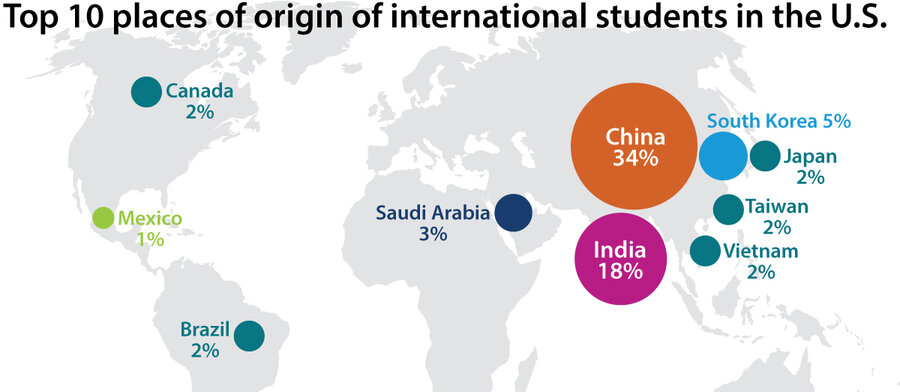

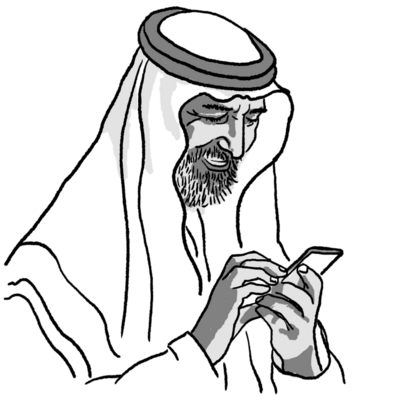

Today’s five hand-picked stories offer two views of today’s impeachment testimony, a potential crack in the wall of polarization, questions about Latino political power, Chinese students on U.S. campuses, and a new app for an old tradition in Jordan.

But first, humpback whales had me when I first heard them sing. I remember sitting in my bedroom as a grade schooler perched over the record player as it crackled along the shiny grooves of a floppy black record that came in National Geographic. The unearthly beauty transported me to a place beyond imagination and yet, amazingly, actually real. What a world I lived in!

I think of that today as I read that populations of humpback whales in the South Atlantic have recovered from near extinction to pre-20th-century abundance. The numbers are unfathomable – from 450 in the 1950s to 25,000 now.

The humpbacks’ song spoke to us all in ways words never could. Similarly, author Rachel Carson helped spawn the environmental movement with her 1962 book that spoke of a “Silent Spring” without birdsong. But what of nature that can’t sing for itself? Can we find a song for the planet?

A Monitor Progress Watch story from last year concludes: “Ultimately, the whales’ recovery is a story of a global community coming together.” Amid the tremendous challenges our planet faces, it is vital to remember the good we can do. And that often begins with the awe and humility that allow us to find our own deeper harmonies as the human race.