- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Remembering a Mideast mediator

Today we look at Israel’s Iran dilemma, the fallout of Latin American protests, a city’s reach to save its schools, a deeper take on women’s self-defense, and the joyful noise of fiddlin’. First, we remember a Mideast peacemaker.

When news came Saturday that Oman’s Sultan Qaboos bin Said, the Gulf nation’s ruler since 1970, had died, Monitor editors began trading messages. At a time of great regional polarization, the sultan’s decades of quiet mediation deserve notice.

His passing felt like “the closing chapter to a more civil time,” says the Monitor’s Taylor Luck, who wrote in 2017 about Sultan Qaboos’ importance to the region. In Muscat, Oman, yesterday, Taylor notes, “just for a moment, everything stopped and reverted back to [a time] when respect trumped rivalry, and dialogue overcame differences.”

Recognition came from Saudis and Qataris, from Iranians and Americans. “Warring factions of Yemen’s civil war all stopped to pay tribute,” notes Taylor, “speaking to the sultan’s legacy.

“Qaboos was not a model democrat, but he was a model statesman, working for prosperity for his people and peace for his neighbors,” Taylor wrote in an email from Jordan. “Traveling and living in the region the past 12 years, I heard nothing but kind words for Sultan Qaboos from princes, politicians, farmers, and fishermen.”

The values that may have helped inspire that – trust, respect, empathy – were celebrated in a Monitor editorial in 2018. They have long extended to Oman itself.

“The country’s diplomacy focuses on understanding the interests of other countries rather than trying to maximize its own gains,” read the editorial, quoting an official in Oman’s foreign ministry. “It relies on seeing them as ‘though we were as them, to see the world through their eyes.’ ”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How demise of Iranian nuclear deal rekindles Israel’s dilemma

Getting what you want politically doesn’t necessarily mean ... getting what you want. Whatever its drawbacks, the Iran nuclear deal gave Israel a breather of sorts. Now its leaders face a grimly familiar predicament, and a ticking clock.

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

Following the killing of Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, Iran said it would no longer refrain from the production of enriched uranium as proscribed in the nuclear agreement it signed with world powers. And Israel, which opposed the deal, once again faces the prospect of its arch enemy being as little as six to 10 months away from having enough fuel to create its first nuclear device.

For all of its flaws, experts say, the agreement would have brought Israel – and the rest of the world – a hiatus of about 10 years from confronting the prospect of a nuclear Iran. But now, Israel could find itself back in the same dilemma it faced before it was signed: “Do nothing and accept Iran on the verge of being a nuclear military force, or strike back,” says Raz Zimmt, an Iran expert at Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies.

“I don’t think in Jerusalem there’s someone who believes, if Iran is months away from a bomb, that President Trump ahead of elections will do something on his own,” says Dr. Zimmt. “The bottom line is we are in a very risky situation right now.”

How demise of Iranian nuclear deal rekindles Israel’s dilemma

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu waged one of his signature political and diplomatic battles against the 2015 Iranian nuclear agreement. The losing effort contributed to his alienation from former President Barack Obama, who brokered the deal.

President Donald Trump, who has been warmly embraced by Mr. Netanyahu, ran for office in part on criticism of the deal, from which he withdrew the United States. He then embarked on a campaign of renewed “maximum pressure” against Iran.

Now Tehran, too, has walked away from the agreement, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which it signed with the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council plus Germany, along with the European Union.

Following the Jan. 3 U.S. assassination of the powerful Qods Force commander, Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, Iran said it would no longer refrain from its production of enriched uranium as proscribed in the agreement.

And Israel, once again, faces the prospect of its arch enemy being as little as six to 10 months away from having enough fuel to create its first nuclear device. Mr. Netanyahu’s office declined to comment for this story.

For all of its flaws, experts say, the JCPOA would have brought Israel – and the rest of the world – a hiatus of about 10 years from confronting the prospect of a nuclear Iran.

But now, Israel could find itself back in the same dilemma it faced before it was signed: “Do nothing and accept Iran on the verge of being a nuclear military force, or strike back,” says Raz Zimmt, an Iran expert at Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies (INSS).

“I don’t think in Jerusalem there’s someone who believes, if Iran is months away from a bomb, that President Trump ahead of elections will do something on his own,” says Dr. Zimmt, a research fellow at the Tel Aviv think tank. “He might tell an Israeli prime minister ‘You have a green light to act,’ but this is not something an Israeli prime minister would like to consider. The bottom line is we are in a very risky situation right now.”

Most senior Israeli intelligence and military officials were not as emphatically opposed to the deal as Mr. Netanyahu was, although none of them saw it as a “good deal” because restrictions on Iran’s nuclear development would begin phasing out after eight years – but this time with international legitimacy and no threat of international sanctions.

Nevertheless, they hinted at relief that extra time had been bought ahead of what’s called the “breakout time” for Iran to become a nuclear power.

Iran’s ambitions: Deterrent or threat?

Despite the latest crisis, Iran is still allowing for international inspections – the last vestiges of the deal to remain in place. They also have not closed the door to future negotiations on a deal, but as their research and development continues, it may prove difficult to turn the clock back on any progress they make in the meantime.

On Sunday the leaders of Britain, France, and Germany urged Iran to return to full compliance with the deal.

Some Israeli experts, among them Elisheva Machlis, a senior lecturer at Bar-Ilan University, argue that Iran is ultimately a rational actor.

Despite the threat Iran potentially poses as a nuclear power, she says, it’s important to ask if Iran would seriously consider actually using nuclear weapons.

“The question is always: Why does Iran need nuclear technology? What is it for?” says Dr. Machlis, arguing it should be understood as part of its regional strongman strategy. “If it’s really for deterrence, the question is, ‘Are they really going to use nuclear weapons?’”

She also argues that Iran, still battle-scarred from a long war with Iraq that lasted for most of the 1980s, is loath to engage in full-scale confrontation and prefers to operate with proxies. She says that’s why Iranian officials have been sending out signals they don’t want to further inflame tensions with the United States.

But whatever Iranian intentions are, few in Israel suggest it not take the threat of a nuclear Iran seriously. Of all the myriad threats facing the Jewish state, a nuclear Iran is considered existential, not just by Mr. Netanyahu, but by security officials across the board.

“No Israeli prime minister will say, ‘Let’s wait and see if Iran is serious.’ No one will take that risk,” says Dr. Zimmt. “With all the damage [conventional ballistic] missiles can do, they cannot eliminate the state of Israel. But nuclear weapons can do that.”

America’s role

But Israel’s options are considered to be limited. Israel can push for more international pressure, namely through intensifying economic sanctions, or the U.S. or Israel could launch a military strike that would seek to destroy Iran’s nuclear capabilities.

“I think at this stage Israel prefers a lower profile and to leave it to President Trump to take initiatives concerning Iran,” says Dr. Zimmt. “The Israeli policy is to not interfere too much, to support American economic pressure on Iran, and not to make statements that would indicate it would use force.”

Some Israeli analysts note, however, that with U.S.-Iran relations at low ebb and the two nations at loggerheads over nuclear sanctions, the strategic situation is deteriorating.

“This is the situation and it’s worsening all the time,” says Ephraim Asculai, who worked in the past for the International Atomic Energy Agency and the Israeli Atomic Energy Commission and is now a senior researcher at the INSS.

“And the deal is dying because Iran is really withdrawing slowly from all prohibitions of the deal. It was not a good deal to begin with, but it’s getting worse now,” says Dr. Asculai, who adds he has some concerns about whether the U.S. would stand behind its pledge to prevent Iran from getting nuclear weapons. “As the Iranians accumulate more enriched uranium, the situation is getting more dangerous.”

Dr. Ascoulai and others argue that it’s essential to push further economic sanctions ahead, which have proven effective in weakening Iran. And he calls on Europeans to be as forceful as possible on sanctions as well.

Future negotiations

But Meir Javedanfar, an Iranian-born Israeli lecturer at the Interdisciplinary Center-Herzliya, a private research college, sounds a more hopeful note.

The inspections the Iranians are still allowing are still better than what existed before the Iran deal, he argues.

“The question is political will: whether they want to make a nuclear weapon or not,” Mr. Javedanfar says. “I don’t think they want that. What I think the Iranians are doing by taking these steps on removing limitations on enrichment and number of centrifuges – is … to strengthen their hand in negotiations with America.

“If there is a Democrat in the next White House or if [Mr.] Trump is re-elected they know they will have no other choice but to sit down and talk to them,” he says. “They will have no other choice because of the economic situation.”

Yossi Kuperwasser, former head of research in the Israeli army’s intelligence branch who recently served as head of Israel’s Ministry of Strategic Affairs, argues that only intense and ongoing pressure on Iran will result in a nuclear deal that actually prevents Iran from creating a nuclear weapon.

“This deal should have never been born. It’s proof of the weakness of the West that Iran was given carte blanche to have a nuclear arsenal,” he says.

“We should remain focused on preventing Iran from moving forward and … say they are no longer contained,” says Mr. Kuperwasser, senior project manager at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, a conservative research institute. “This should concern everyone.”

To read the rest of the Monitor’s coverage of the U.S.-Iran clash, please click here.

A deeper look

Behind Latin America’s protests, a fading faith in democracy

In Latin America’s wave of protests, some see democracy in action. But many see growing anger about democracy’s failures, and ask: If a tipping point comes, what might rise in its place?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Not long ago, nearly all Latin American nations were living under dictatorship. But by the 1990s, the numbers had flipped – with mano dura replaced with democracy everywhere from Argentina to Guatemala.

But as this fall’s slew of protests illustrates, many citizens feel that the promise of democracy hasn’t gone according to plan.

The commodities boom of the 2000s helped many nations reduce poverty and inequality in one of the world’s most unequal regions. But over the past several years, economies have sputtered, crime and violence have ticked up, and corruption scandals have cast a pall over earlier optimism. Today’s protests in each country – Chile, Bolivia, Colombia, to name a few – have different catalysts, but many reflect a growing disenchantment with democracy, analysts say.

Support for democracy is at an all-time low in Latin America and the Caribbean, according to the latest AmericasBarometer regional report. Satisfaction with how democracy works has also fallen to just shy of 40%.

Now, how leaders respond could determine the region’s path forward.

“Democracy comes and goes in waves,” says Elizabeth Zechmeister, a Vanderbilt University professor who directed the study. “But then, should we be alarmed? Yes. Because these periods of democratic recession have led to a lot of hardship.”

Behind Latin America’s protests, a fading faith in democracy

Drums pound in a crowded plaza in downtown Santiago, Chile. The so-called front line of protesters standing between the demonstrations and the national police on a recent afternoon don bike helmets and handmade shields with the names of some of their almost 30 fallen peers. “The people, the people, where are the people?” they chant.

“The people are in the streets demanding dignity!” the crowd responds.

But it’s not just Chileans in the streets asking for respect – and safety, and economic security, and quality public services – from their governments. Latin America rounded out the past decade with months of large-scale public protests. The tipping points for citizen discontent run the gamut, from a small increase in train fare in conservative Chile to suspicious election results in leftist Bolivia and fuel hikes in centrist Ecuador. Protesters have taken to the streets from Peru to Haiti, and from Colombia to Mexico demanding better health care and public education, and an end to corruption and rising murder rates.

Regardless of diverse political leanings, the region seems to be in agreement over one thing: Their satisfaction with democracy is on the decline.

It wasn’t long ago that nearly all Latin American nations were living under a dictatorship. But by the 1990s, the numbers had essentially flipped, replacing mano dura governance with democratic leadership and institutions everywhere from Argentina to Nicaragua, and from Chile to Guatemala. Democracy promised citizens more equality and economic opportunity, less violence and oppression. The commodities boom that bolstered many regional economies during the 2000s helped nations deliver on many of these promises, reducing poverty and slowly shrinking inequality in one of the most unequal regions in the world. But over the past several years, economies have sputtered, crime and violence have ticked up, and high-profile corruption scandals have hit nearly every nation, casting a pall over earlier optimism.

“Democracy has been failing to deliver on its promise,” says Elizabeth Zechmiester, who directs the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) at Vanderbilt University, which has tracked trends in democracy and public satisfaction in the region since 2004. “People feel less safe, more economically vulnerable, and that governments aren’t doing enough to respond to their basic needs.”

Some see the fire hose of protests flooding Latin America as a sign of democratic health: Citizens are taking their leaders to task. It’s in line with protests and growing discontent with the status quo worldwide. But some worry that the frustration and lackluster responses from government officials, paired with dimming views of democracy, may further open the door to authoritarianism. How leaders respond to citizen dissatisfaction could be the true determinant of the region’s path forward, observers say.

“Democracy comes and goes in waves,” says Dr. Zechmeister. “The fact that we’re in a democracy recession right now is not entirely unique ... when we take a broad look at modern political history,” she says.

“But then, should we be alarmed? Yes. Because these periods of democratic recession have led to a lot of hardship. ... This takes a toll on quality of life and basic liberties.”

“Brewing discontentment”

Support for democracy is at an all-time low in Latin America and the Caribbean, according to the 2018-19 LAPOP AmericasBarometer regional report, based on more than 31,000 interviews in 20 countries in the region. Support for democracy as the best form of government is particularly low in places like Honduras (45%) and Guatemala (48.9%), where leaders have blatantly disregarded democratic institutions like electoral processes and anti-corruption bodies in recent years. Satisfaction with democracy, which measures the sense of how well it is working, is also falling across the region. Satisfaction has gone from nearly 60% on average in 2010 to just shy of 40% across Latin America today.

“There’s a brewing discontentment and disillusionment with democracy in the abstract and how it is functioning in practice,” says Dr. Zechmeister.

That has to do with a number of factors that fall into three central categories: clean government, physical security, and economic well-being. Data in each has been “trending in a negative direction over the past five or so years,” Dr. Zechmeister says.

Corruption scandals have swept Latin America, dampening citizen faith in democracy. Brazil’s so-called Car Wash scandal implicated scores of politicians and more than one former president. The Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht allegedly bribed officials across the region, including in Colombia and Mexico. Four former presidents are under investigation for corruption in Peru, where the current leader dissolved an intractable Congress last fall, something opposition lawmakers likened to a legislative coup. (The AmericasBarometer report found an increased tolerance for dissolving legislatures in times of crisis in the region, as well.) Some 53% of Latin Americans feel corruption has gotten worse in their countries over the past year, according to Transparency International’s 2019 Global Corruption Barometer.

Crime and violence are also on the upswing, creating a sense that governments aren’t doing enough to keep citizens safe. Out of the 20 countries with the highest homicide rates in the world, 17 are in Latin America, according to a 2018 report by the Igarapé Institute, a Brazil-based think tank.

“If I’m not safe taking [public] transportation and walking home from work at night, that’s definitely the government’s fault,” says Ana Regina Fernandez, a medical resident recharging her transportation card in Mexico City on a recent afternoon. Although she didn’t participate, she supported large-scale protests in the capital last year demanding that the government work to find solutions to high levels of violence in Mexico – particularly violence against women.

But it’s perhaps the region’s economy that has put the biggest dent in citizen faith in democracy, experts say. Following Latin America’s commodity boom, when tens of thousands of people moved out of poverty, growth started to stagnate. By 2014, South America had just over 0.5% average growth, posing a threat to the newly minted middle classes and the promise of upward mobility.

Poster child protests

The anxiety around possibly backtracking into poverty, or not gaining the education and formal employment long heralded by regional governments and multinational bodies, came into full relief last fall in Chile. The government proposed a roughly 4% fare hike for the capital’s metro, which sparked widespread protests. It was less than 5 U.S. cents, but a significant bump for low-income families that already spend almost 24% of their income on transportation.

Marcela Pérez has been protesting since October in Santiago’s Plaza de Italia – which protesters (and Google Maps) have redubbed Plaza de la Dignidad. “Our legislators have become deaf,” says the single mother, who works in higher education. “We can’t have people legislating who don’t know how much the metro costs at rush hour or the price of a loaf of bread.”

For years, Chile has been Latin America’s poster child of stability and prosperity. Yet it is the most unequal country in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a group of 36 mostly developed economies, and has an income gap roughly 65% higher than the OECD average.

Ms. Pérez grew up in one of the poorest parts of Santiago and had a son when she was 17 years old. She recalls having it hammered into her, by her family and the government, that the only way to get ahead was to study. So she did – and she picked up tens of thousands of dollars in debt along the way, with few job prospects that could help her chip away at it. Now her son is about to enter college. “How am I going to pay?” she asks. “I have no idea. [The government] created a process of eternal debt.”

After initially resisting protesters’ demands, and declaring that Chile was “at war against a powerful enemy,” President Sebastian Piñera rolled back the fare hikes, and promised to cut electricity costs and slightly increase the minimum wage and minimum pensions.

But the price hikes were simply a tipping point – as in many protests in the region. As protesters flooded out to demand more from their government, its early, forceful response drummed up memories of dictatorship-era repression. As protesters continued to turn out, they brought the very backbone of Chile’s government – its constitution – back into the spotlight.

Chile’s Constitution, approved in 1980, prioritizes then-dictator Augusto Pinochet’s neoliberal economic agenda over the guarantee of public services like access to water or health care, critics say. Many protesters demand it be replaced, pointing to the symbolic heft of its creation during Pinochet’s 1973-90 dictatorship. And despite amendments to the document over the years, many argue its legal framework remains conservative, allowing few formal channels for the public to participate in political decision-making. It requires at least two-thirds approval by Congress to make any changes, a high bar.

In November, the government agreed to hold a referendum in April on whether to draft a new constitution. Fernando Atria, a constitutional lawyer and professor at the University of Chile, has been a key voice in helping Chileans understand what that might mean. He’s come out to citizen-organized neighborhood gatherings – met by cheers and applause – to explain how he views the current constitution as working against the people.

“Originally its purpose was to protect the political and economic model of the dictatorship, so that the coming democracy couldn’t reverse” systems the dictatorship put into place, Mr. Atria says. “The purpose was to configure a power that couldn’t make transformative decisions, and 30 years later we can see a policy that’s still marked by these characteristics.”

Despite the struggles in Chile, outside observers say its government has taken important, if belated, steps in trying to engage protesters and listen to their demands.

In Colombia, where protests started in November following large-scale demonstrations elsewhere in the region, the government has failed to learn from the Chilean situation, says Sergio Guzmán, director of Colombia Risk Analysis, a political risk consultancy.

Seeing neighboring protests’ success helped Colombia’s demonstrations gain traction, but the country’s peace accords may have played a key role, too. For decades the government was unable to deliver on expected public services because it was at war with the FARC guerrilla movement, he says. Many Colombians feel they’ve been patient for so long, but with a peace deal signed and in effect, “there are no excuses not to meet your end of the bargain.”

Over 75% of Colombians believe more than half of the nation’s politicians, if not all, are corrupt, according to the AmericasBarometer report. Yet the government, already unpopular, doesn’t “seem to recognize the protesters as players with legitimate issues that need addressing,” says Mr. Guzmán. It could lead to more estrangement and protests in 2020. “That’s not in the government’s best interest.”

Release valve ahead?

In Bolivia, the protests feel distinct from the rest of the region. What began as an uprising of citizens concerned that the longest-serving president in Latin America, Evo Morales, was gaming the system to stay in power – arguably a citizen fight to preserve democracy – has become far less clear-cut. Some protesters are now calling for the former leader’s return from exile in Argentina. Others are concerned the interim government is dead set on overturning any remnant of the Morales government, such as more inclusion for the nation’s indigenous population.

Democracy – and its unmet promises – are still at the core, observers say.

In late November, nearly a month after thousands of Bolivians joined pro-democracy protests that led to the ousting of President Morales, thousands more turned out in cities like Sacaba to demand his return.

Mario Olmos, a father of three who did not participate in early protests for or against Mr. Morales, decided to protest after at least nine civilians were killed there during clashes with government forces.

“We raised up against [the] injustice between classes,” he says, navigating the rubble and burnt tires that cover the streets in the wake of the unrest.

During the protests against Mr. Morales, government forces didn’t respond to protests as harshly, he says, lifting up a string of barbed wire so he could carry his daughter beyond the protest zone. They “let the rich do whatever they want, and they treat us, the poor people, badly.”

Elections scheduled for May could be a release valve for some of the pressure building up over recent months. And in countries where elections went smoothly in recent years, support for democracy tended to increase, according to AmericasBarometer. That includes places such as Mexico and Brazil, where unpopular incumbents were voted out of office by populist-style leaders of vastly different political leanings.

But a winning vote alone may not be enough to buoy support for democracy. One worrying trend in the region is the attitude of young voters, who are particularly disenchanted with democracy, according to a 2017 United Nations report. LAPOP data found similar results. “For the first generation born and raised in democracy, the gap between expectations ... and actual socio-economic outcomes widened the distance between societies and their governments,” the report reads. Some 36% of Latin American youth say they have confidence in the transparency of election results, according to U.N. data, versus the OECD average of 62%.

How their leaders listen or react to their frustrations could determine the next chapter of regional protests, analysts say.

Governments “engaging these movements early on and reaching compromise” could defuse tensions, says Mr. Guzmán. “But in practice we’re seeing less compromise, less willingness to engage with protesters to create a society that’s genuinely better for all.”

Gabriela García contributed reporting from Santiago, Chile. Erika Piñeros contributed reporting from Sacaba, Bolivia.

Inside one Michigan city’s fight to save its schools

Successful schools tend to engage parents. What if a school system broadened its outreach to pull in the perspectives of local business owners and others? We went to Michigan to find out.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Lee A. Dean Contributor

Benton Harbor has sustained a series of setbacks. The Michigan city’s population dwindled from 19,136 in 1960 to about 9,800 in 2018. Riots erupted in 2003, and it came under state emergency financial management in 2010.

But last year, when Gov. Gretchen Whitmer announced a plan to close the city’s two high schools, it was one loss too many for community leaders. They quickly drew a line in the Lake Michigan beach sand and applied citizen pressure with protests, press conferences, and a face-to-face meeting with the governor.

The state backed away from its decision, allowing the high schools to stay open. But a far larger battle remains: coming up with a plan to reverse the district’s decline, and in the process perhaps create a turnaround template for other struggling districts.

The stakeholders have now adopted a comprehensive approach that emphasizes community engagement.

State Deputy Treasurer Joyce Parker, who is chairing a newly formed advisory committee for the process, says the community strategy “is very unique and one we believe will allow us to identify what the real issues are and develop a more holistic approach."

Inside one Michigan city’s fight to save its schools

When voters in Benton Harbor overwhelmingly supported Gretchen Whitmer to be Michigan’s next governor in the autumn of 2018, they could hardly have imagined that she would be the subject of their ire the following spring.

The change came after Governor Whitmer announced a plan to close the city’s two high schools, the main campus and a much smaller magnet school. Community resistance, which included a tense face-to-face meeting with the governor at a Benton Harbor church, was a major factor in motivating the state to back away from its decision and try a new approach, one that will keep the two high schools open.

Now that the city has won the initial skirmish, a far larger battle remains: coming up with a plan to reverse the district’s festering economic and academic decline, and in the process perhaps create a turnaround template for other struggling districts.

Michigan Deputy Treasurer Joyce Parker, who is chairing a newly formed advisory committee, believes the approach will succeed where others fell short.

Unlike earlier partnerships with state government, which tended to stress cooperative agreements between state officials and the local board of education, this initiative is emphasizing community engagement throughout the process. The advisory committee includes local business leaders, teachers, and clergy, as well as the state Department of Education.

“This process, if it provides the results we’re looking for, is one that we could look at for other school districts,” Ms. Parker says. “I suspect that some of the same issues that are taking place in Benton Harbor are in other districts – not only districts like Pontiac and Flint, but even rural districts. Using this community approach is very unique and one we believe will allow us to identify what the real issues are and develop a more holistic approach.”

In addition to the community involvement, another key component of the Benton Harbor approach is its comprehensive nature. Improving the high schools’ performance is an obvious focus, but the committee is exploring every segment of the educational environment, ranging from finances and properties to family engagement and student mental health. “This process is one that is much more comprehensive,” Ms. Parker affirms.

A once prosperous city

Benton Harbor is a small city on the shore of Lake Michigan, about a two-hour drive east from Chicago. In its earlier years, the city prospered due in part to its robust industrial base. As industry declined and with the onset of white flight, its population dwindled from a high of 19,136 in the 1960 census to 9,826 in a 2018 census estimate. Today, Benton Harbor is 85.6% African American, and almost 47% of its population lives in poverty.

The city has sustained a series of other setbacks, including riots in 2003 and coming under state emergency financial management in 2010. Benton Harbor is often compared with its neighbor across the St. Joseph River, the city of St. Joseph, which is predominantly white and more affluent. Lingering racial tensions came to national attention in the 1998 book “The Other Side of the River” by Alex Kotlowitz, which profiled how differently residents of the two cities reacted to the mysterious death of an African American teen from Benton Harbor.

Benton Harbor’s main high school was in the bottom 25% of high schools in U.S. News & World Report’s national educational survey last year. According to state Department of Education statistics for the 2018-19 school year, which used standardized test scores, fewer than 5% of Benton Harbor High School students were proficient in all subjects, compared with a statewide average of 42%.

Benton Harbor’s plunge in population has been a contributing factor in the sharp decline also seen in the district’s student enrollment. Perhaps even more profound is the rise of charter schools and other schools of choice. In this climate of competition for students, the numbers paint a picture of how Benton Harbor is faring. Enrollment is declining at a rate of about 5% to 10% each year. Of the K-12 students currently living within district boundaries, 64% are attending schools elsewhere.

By 2018, the district had racked up a debt of more than $18 million. This grim figure, combined with the substandard academic proficiency, spurred the state to make its proposal to close the high schools, parcel students out to neighboring districts, and concentrate on K-8 education.

One loss too many

With all the hammer blows that Benton Harbor has endured, the potential loss of its high schools was one loss too many for community leaders. They quickly drew a line in the Lake Michigan beach sand and applied citizen pressure with protests, press conferences, and the meeting with Governor Whitmer.

“This community has a lot of history and a lot of pride,” says Ms. Parker, the deputy state treasurer. “The school district is a focal point in the community. As a result, there are a lot of individuals who want to see the district intact. That level of history and pride is something directly related to this particular district.”

The schools are also one of the largest employers in Benton Harbor.

Getting the district’s financial house in order will mean chipping away at operating debt and deficits. One idea is to sell unused properties; another is to lobby legislators for funding reforms. Benton Harbor High School alumnus Marvin Haywood has another proposal: forgiveness of the district’s debt.

“Eighteen million dollars is a drop in the bucket from the state’s perspective,” Mr. Haywood said last month at the first of a series of community outreach meetings. “Other districts have $200 or $300 million in debt, but there’s never any talk of shutting them down.”

Committee members and school staff are aware that a set of problems that took decades to develop will take time to solve. Interim Superintendent Patricia Robinson says the goals of school administrators are measured: first stop the decline in enrollment and then boost the schools’ academic performance. One piece of the academic strategy is to establish benchmarks based on the proficiency test scores at nearby charter schools.

“We’re tasked with trying to re-create our district,” Ms. Robinson says. “Are we going to create something where all of our students come back? Most likely not. But it’s up to us to find ways to stop the decline and stabilize enrollment.”

Getting business owners involved

New Benton Harbor High School Principal Reedell Holmes, who arrived in November, was hired because of his experience as an administrator in Grand Rapids and Muskegon Heights – other challenged districts in Michigan – and his understanding of the culture that exists in urban districts. He has set to work increasing student attendance, boosting achievement scores in math and literacy, and building a positive atmosphere for both staff and students. Community outreach is another building block.

“My plan is to go out and shake hands with business owners and stakeholders and get them involved in the education process here. I want to get 20 businesses to adopt our school and be part of what we’re doing. I’ve done that everywhere I’ve gone,” Mr. Holmes says.

While the adults work to come up with a plan, the students find themselves dealing with a situation that has plenty at stake both for themselves and for the future of their schools. Tray’von Gentry, a soft-spoken junior who is the student representative on the advisory committee, has not noticed his peers experiencing any extra pressure to improve academically. His concerns are more prosaic: He wants to see more after-school activities for students, especially those who may not be interested in sports or band.

Citizens who spoke at the first community outreach session worried out loud that the narrative of an underperforming school district reflects unfairly on the students of the high schools, who Ms. Robinson says are 88% African American.

“They’re not wolves. They’re not thugs. They’re not dumb. They’re not illiterate. You have kids who are not being educated properly,” says former school administrator Reinaldo Tripplett. “That is a group of kids who are so deserving of a quality education.”

Hope, wariness, and tenacity

The mood at the outreach meeting was a mixture of hope and wariness. Memories of past efforts to improve the school district linger, accented by stories of promising beginnings that faded away in the face of a multiplicity of problems. Yet the same spirit of tenacity that helped the community reverse the decision to close the schools is being called on to fuel the hard work of rebuilding.

Benton Harbor residents, who identify strongly with the schools’ tiger mascot, realize they’ve entered a new and perhaps decisive phase.

“At one time in this community and the surrounding areas, the high school had a legacy of pride, integrity, and great accomplishment in academics, athletics, and in the community,” the Rev. William Whitfield said at the outreach meeting. “I’m proud to be a Benton Harbor Tiger, a Benton Harbor fighting Tiger. And we’re in a fight.”

Difference-maker

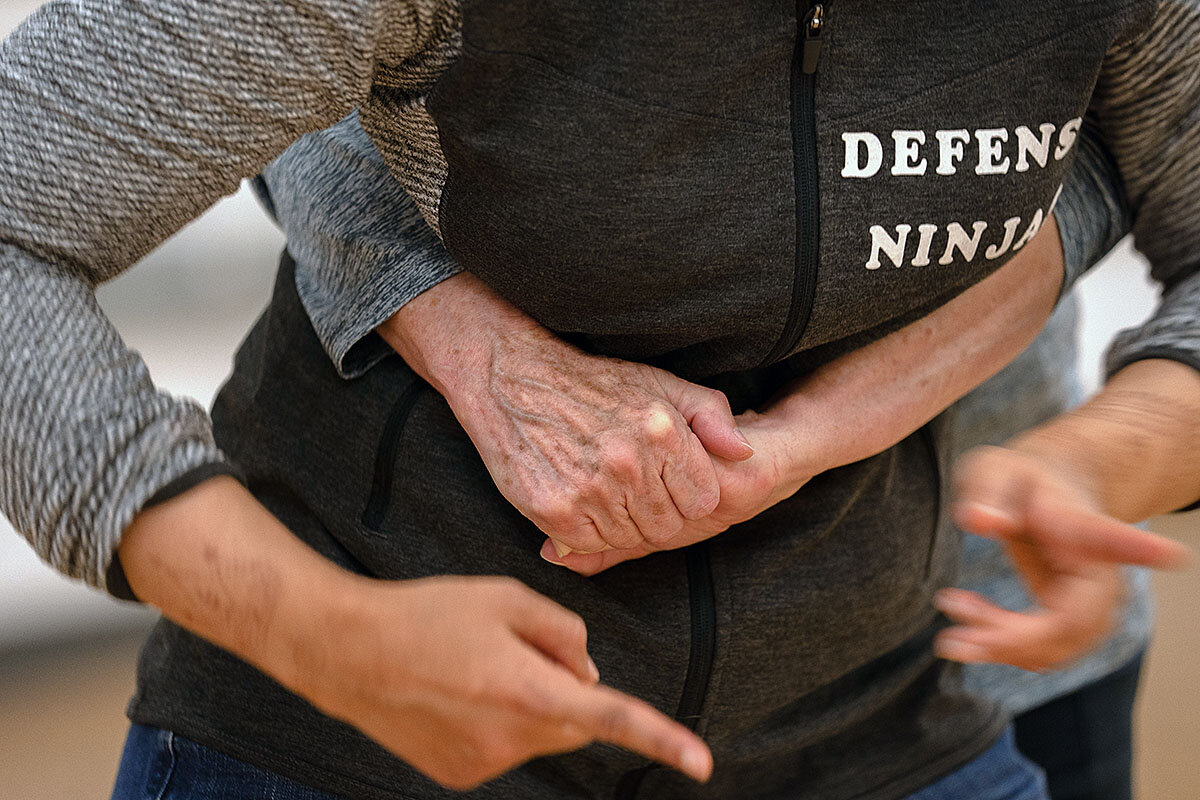

‘Defense ninja’: A Muslim woman’s journey to empowerment

Self-defense is about much more than striking back at an attacker. This story introduces an instructor who leads other women to beat back the limitations that have been imposed on them.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Hallie Golden Contributor

From physical abuse in her workplace to inappropriate touching in her martial arts studio, Fauzia Lala is no stranger to harassment. “Looking back, I was just too scared to speak up or say anything,” she says.

Unable to find training that would allow her to protect herself and speak up when needed, Ms. Lala decided to develop her own. Today, she is head instructor of Defense Ninjas, a women’s self-defense school based in Washington.

The school helps fill an important need for Muslim women who may feel especially vulnerable in the current political and social climate. In just over two years, Ms. Lala’s reach has grown. She started by teaching a handful of students out of a mosque. Now she has 35 to 40 regular students, teaches workshops, and has expanded far beyond the Muslim community. Her classes have become a haven for dozens of women from diverse backgrounds to learn self-defense and who, in the process, discover that what unites them as women is more important than anything that may divide them.

‘Defense ninja’: A Muslim woman’s journey to empowerment

Fauzia Lala was sparring with a teenage member of her tae kwan do class a few years ago when she felt him touch her breast. A provisional black belt, she was well versed in the intricacies of sparring, so when it happened several more times, she knew it was intentional.

Ms. Lala finished the match but didn’t feel as though she could speak up about what had happened. A Muslim who grew up in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, she says she experienced harassment on the job several times when she worked for Microsoft, and had felt too frightened to speak up about it.

“Here I am a black belt that ended up crying and leaving; that’s just crazy,” says Ms. Lala.

Over the next few years, she became increasingly aware of attacks against people – especially women – in the Muslim community, including a man who screamed anti-Muslim insults at two teenagers on a train in Portland, Oregon, then stabbed and killed two men who intervened to help.

Unable to find training that would allow her to protect herself and speak up when needed, Ms. Lala developed her own. Today, she is head instructor of Defense Ninjas, a women’s self-defense school based in Washington. Training consists of 12 levels organized around technical moves and defense objectives, such as escapes, attack, and ground defense. The classes help to fill an important need for Muslim women who may feel especially vulnerable in the current political and social climate.

In just over two years, Ms. Lala’s reach has grown. She started by teaching a handful of students out of a mosque. Now she has 35 to 40 regular students, teaches workshops, and has expanded far beyond the Muslim community. Her classes have become a haven for women from diverse backgrounds to learn self-defense and, in the process, discover that what unites them as women is more important than anything that may divide them.

“Everybody everywhere needs to know self-defense, and currently it’s only being taught in forms of workshops or kickboxing, and that’s not effective,” says Ms. Lala.

“We need the whole curriculum. We need the emotional side. We need the therapeutic side, the meditation, the yoga – everything that women need.”

“An empowering experience”

On a recent Tuesday evening, five women gathered at Redmond Community Center, one of several locations where Ms. Lala offers classes. With Flo Rida’s “My House” playing quietly in the background, Ms. Lala, dressed in jeans and a dark headscarf, stood in front of the group and asked a simple question: “Women don’t really want to punch. Why?”

“Because we don’t have as much hand strength,” answered student Jamie Brown.

Ms. Lala agreed that a woman’s punch may not be strong enough to help her escape a bad situation. But she went on to explain that since she is likely to be shorter than her attacker, she can more easily target the nose and jaw. Putting a palm under the jaw and pushing up and out, she said, could cause the attacker to pass out.

But self-defense is about much more than the physical side of things – like being able to speak up when necessary. Ms. Lala tries to get students together outside her classes once a month to give them more time to interact.

On one Saturday afternoon, she and a handful of women sat in a circle on the floor of a studio on Mercer Island to discuss fear. They spent three minutes jotting down things that scared them, and then shared patterns they noticed, including struggles with self-doubt, aging, and their appearance.

When Ms. Lala brought up a fight this past summer at Disneyland that drew widespread attention due to the seeming inaction of security, some questioned whether they could rely on anyone to watch out for them.

“It always makes me think, ‘What would I do?’” says one of Ms. Lala’s students, Tracy Bumgarner. “If I were in this situation, would I jump in?”

Amelia Neighbors, a Muslim IT project manager, was one of Ms. Lala’s first students. She says the classes quickly started feeling like a club, and that students bonded with each other regardless of their background. Students understand that their peers in class also want to be able to protect themselves, and that they might have had experiences that made them feel vulnerable.

Ms. Neighbors recalled a student who told her class about being physically attacked. “We immediately felt this compassion,” Ms. Neighbors says. “I think all of us have felt in our lives somehow disregarded or treated poorly.”

Learning how to protect oneself and others is “just kind of an empowering experience, and it builds that sense of camaraderie,” she says.

Ms. Lala learned from experience how difficult it can be to speak up. She moved to Seattle when she was 20 to study computer science at Seattle University. When she finished her junior year, she was offered a job at Microsoft.

On the job, Ms. Lala says co-workers touched her inappropriately and threw things at her when they were angry. She says people told her that since she was in a modern country, she didn’t need to wear a headscarf. One person pulled at it.

“Looking back, I was just too scared to speak up or say anything,” she says. “That’s how it escalates.”

That’s also part of what drew her to self-defense training.

Confronting harassment head-on

In her classes, she cites studies indicating that it’s very hard to know what you would do in a real situation. While many women say they would kick and scream if attacked, she told one recent class about a Swedish study that showed nearly half of women who were attacked reported experiencing extreme paralysis.

Which is why she wants her students to know they have innate strength, like leveraging their hips and core, to push away attackers. It’s just about knowing how to use it.

“It’s also the vocal side of things and the emotional side of things, so when people are saying certain things or doing certain things, I can stand up and say, ‘Don’t be disrespectful,’” she explains.

Ms. Lala is working to convert Defense Ninjas into a nonprofit, which she hopes will allow her to hire more instructors and establish her own dedicated space for her classes. She also wants to expand throughout Washington state, and perhaps beyond.

Ms. Lala says when women initially start taking her classes, some feel intimidated. But she’s noticed that they quickly start to bond with the other students and develop strong friendships.

“They’re all going through the same thing,” she says, explaining that they want to know how to confront the harassment and abuse so many women face, or simply gain more confidence and control. “They all want something more in life besides whatever they have right now.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect that the individuals who were harassed in Portland were teenagers.

This story was produced in association with the Round Earth Media program of the International Women’s Media Foundation.

On Film

A toe-tapping ode to Appalachian music

Roots and Americana forms of music not only influence many new artists, they’ve also shown up in compelling documentaries from Ken Burns’ “Country Music” to the remarkable new CNN portrait of Linda Ronstadt. Here’s a look at “Fiddlin’,” a narrower take that has real gaps, but that also offers an uplifting look at the joy music can bring.

A toe-tapping ode to Appalachian music

For Galax, Virginia, an Appalachian town hit hard by the loss of its furniture industry, a yearly fiddle convention attracts tourists from locales as far-flung as Japan and Australia. Old-time music, a living ancestor of bluegrass, country, and rock ’n’ roll, is the town’s heartbeat. Despite the relative lack of commercial interest in old-time, it continues to thrive, passed down from generation to generation.

In “Fiddlin’,” an ode to old-time and its community, sibling filmmakers and Blue Ridge Mountain natives Julie Simone and Vicki Vlasic explore the power of the music they grew up on. They take viewers into the 2015 edition of Galax’s Old Fiddlers’ Convention, where musicians play into the wee hours in makeshift tents on a campground. “Fiddlin’,” now available on Amazon Prime and Apple TV, has racked up more than a dozen awards since it began playing at festivals in 2018.

It’s an uplifting look at the joys music can bring, although its narrow account of that music’s history contains disappointing oversights, particularly relating to race. For anyone interested in roots music or Americana, however, “Fiddlin’” offers some good tunes with plenty of twang.

There’s an undoubtedly communal aspect to old-time. Speaking about its distinction from bluegrass, fiddler Jake Krack describes old-time as “hanging-out-in-the-living-room-jamming sort of music.” The ability of old-time music to bring generations together makes for the film’s most heartwarming moments. These bonds shine through in the friendship between celebrated guitar maker Wayne Henderson, a self-described “geezer,” and freckled prodigy Presley Barker, who was just 11 years old at the time of filming.

Presley sees Mr. Henderson as a role model and a hero, but the pair find themselves dueling for the coveted blue ribbon in the convention’s guitar competition. Even beyond Presley, a wealth of precocious youngsters in the film are dedicated to preserving old-time.

For a film that celebrates tradition, however, “Fiddlin’” lacks serious inquiry into its roots. It puts forth a melting pot narrative in which fiddles, brought by Scottish-Irish immigrants, mixed with banjos, made by enslaved people of African origin, to create old-time. Ken Burns’ recent eight-part series “Country Music” provides more historical context on race, acknowledging that minstrelsy was responsible for the banjo’s incorporation into mainstream American music. Much of the work of Rhiannon Giddens, a singer-songwriter and music historian featured in the Burns series, has endeavored to reclaim the black roots of American folk music.

To its credit, the film documents the struggles women face to gain recognition in a field dominated by mostly white men. It also discusses attitudes toward LGBTQ people, although its focus is not to document cultural exclusions.

“Fiddlin’” is at its best when it meshes intimate performances, given on porches and in yards, with personal stories of connection with music. These celebrate music as an antidote to hard times. Karen Carr, a member of The Crooked Road Ramblers, credits “messing” with her guitar for weaning her off the pills she took to combat her depression. Describing the significance of the banjo for enslaved people, mandolin player Ronald Tuck says, “If they wanted to think about good times, they would always play music.”

Those good times come alive in the scenes where musicians join together in song as spectators clap and toe-tap along. While these images become somewhat repetitive, some musicians could have used more screen time, like Dori Freeman or Martha Spencer, who shines on the concluding song “Home Is Where the Fiddle Rings.”

“Fiddlin’,” though not a work of history, is lively, with its share of touching moments. It should be entertaining enough for most Americana fans, and offers a glimpse of how Appalachia grounds its identity in its music.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Missiles, lies, and contrition. Has Iran changed?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Contrition rarely plays a role on the world stage, which is one reason to note the sudden introspection by Iran after admitting it not only shot down a Ukrainian passenger jet Jan. 8 but also denied responsibility for three days.

For a country that has tried to force a religion on others for 40 years, this burst of self-reflection hints that the regime may be open to more radical honesty despite a long record of deception and manipulation. Some experts contend Iran might be facing a “Chernobyl moment,” referring to the change in the Soviet Union after Russians learned of the disaster at the Chernobyl nuclear power station in 1986 and official attempts to cover it up.

Like many countries driven by ideology or ruled by powerful figures, Iran is not used to saying sorry. Yet this case of official humility, even if forced on the regime, could allow it to see the benefits of surrendering to the truth in the face of its weakness.

Other nations can take note of this self-reflection and hope this tragic incident has offered a lasting lesson to the Islamic republic.

Missiles, lies, and contrition. Has Iran changed?

Contrition rarely plays a role on the world stage, which is one reason to note the sudden introspection by Iran after admitting it not only shot down a Ukrainian passenger jet Jan. 8 but also denied responsibility for three days. Here is how officials, after international exposure of the incident, finally took accountability, something demanded by Iranian protesters in recent days:

President Hassan Rouhani described the firing of a military missile at the civilian aircraft as an “unforgivable mistake.” The head of the Revolutionary Guard, Maj. Gen. Hossein Salami, apologized. “Never in my life was I so ashamed,” he said. The foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, tweeted an emoji showing a broken heart to express the official grief over the 176 people killed on board the civilian flight.

The supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, ordered the armed forces to address their “shortcomings.” The government set up a task force to investigate the downing of the plane and tend to the victims’ families. It emphasized the need for “total honesty and transparency.” Iran now appears to be cooperating with countries whose citizens were killed by the missile.

The apologies didn’t stop there. Some journalists in the Iran’s highly controlled media also noted their role in spreading official lies. The Tehran Association of Journalists issued a statement saying, “Hiding the truth and spreading lies traumatized the public. What happened was a catastrophe for media in Iran.”

For a country that has tried to force a religion on others for 40 years, this burst of self-reflection hints that the regime may be open to more radical honesty despite a long record of deception and manipulation. Some experts contend Iran might be facing a “Chernobyl moment,” referring to the change in the Soviet Union after Russians learned of the disaster at the Chernobyl nuclear power station in 1986 and official attempts to cover it up.

Like many countries driven by ideology or ruled by powerful figures, Iran is not used to saying sorry. It seems to follow Benjamin Disraeli’s advice to “never explain, never apologize.” Yet this case of official humility, even if forced on the regime, could allow it to see the benefits of surrendering to the truth in the face of its weakness. “We are ashamed, but we will make recompense,” said General Salami.

While all these actions may merely be aimed at preserving the regime, the official remorse, repentance, and restitution are a small step toward the redemption of Iran. Other nations can take note of this self-reflection and hope this tragic incident has offered a lasting lesson to the Islamic republic.

To read the rest of the Monitor’s coverage of the U.S.-Iran clash, please click here.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The pause that empowers

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Larissa Snorek

Recent protests and demonstrations around the world have made one thing clear: Change is desired by many. It can seem hard to know where to begin, but pausing to feel the intelligent presence of God, good, is an empowering starting point.

The pause that empowers

In recent months, the world has generously offered a stage for demonstrations on a range of issues. From protests in Iran and India and continuing unrest in Hong Kong to the “yellow vest” movement in France and the Extinction Rebellion, hardly an area of the world remains untouched. The common story? Something must change, even if what that is or how to go about it isn’t clear.

In one of my first jobs, my human rights colleagues and I regularly staged protests in our city for one cause or another. Yet when asked what we hoped to achieve, our answers were often vague. In essence, our deep desire was to see individuals reach out and connect, with compassion and caring that would result in changing society.

Innovation, change, and progress happen as a result of thought changing. Actions may contribute to this change – but the ultimate shift must be mental. When thinking is primarily focused on abstract issues needing to be solved out there in the world, it can be difficult to know where to begin. But every outward change is the result of what happens first within hearts and minds.

November 2019 marked the 30th anniversary of the Berlin Wall coming down. I remember the day well. I also remember well a talk I heard shortly after by a woman who’d lived in East Germany. She talked about praying for unification every day for 10 years straight.

Her persistence struck me. When I asked her what kept her going all that time without seeing any outward evidence of change, she said something I’ll never forget: The wall came down in a moment. But it wasn’t the work of a moment. It was the result of all the moments leading up to the instant that thought changed. And what do you think changes thought?

She said that every time she paused and turned her thoughts toward God, she could feel a shift happening in her consciousness. She was gaining a more spiritual view of God’s irresistible power and unwavering presence right where division seemed so entrenched. This kept her going.

Revolutionary writings by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, outline a model for change: “The best spiritual type of Christly method for uplifting human thought and imparting divine Truth, is stationary power, stillness, and strength; and when this spiritual ideal is made our own, it becomes the model for human action” (“Retrospection and Introspection,” p. 93).

There’s an irony to this – that stillness is the model for human action. Often, when we identify a problem, the first response is to want to do something. But sometimes the best thing to do is to be still and feel divine presence.

Christ Jesus has been a model for me regarding stillness. With a mob surrounding him ready to stone a woman caught in adultery, he stayed still. After some moments, he simply made a statement that changed the thought of everyone there: Those of you without sin can cast the first stone. And one by one the woman’s accusers left, until the whole crowd had dispersed (see John 8:3-11).

True quietness has vibrancy. In spiritual stillness, thought aligns itself “intelligently with God” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 107). Christian Science defines God as divine Mind. This Mind gives us ideas that change how we think – when we yield up our own limited conceptions to them. We see that spiritual reality includes all the goodness, peace, and love we wish to see as already established in the completeness of divine creation.

Awareness of this precludes our feeling any urgency stemming from angst, nervousness, or fatigue. Action proceeding from divine presence is not motivated by fear or self-will, and when we are aligned with this presence, we realize that it is all there is, and it is all we can feel in that moment.

Action for change, when premised on this divine allness, acknowledges the spiritual completeness that God is showing us. Pausing to see spiritually chips away at the mental blocks trying to continually divide humanity.

Being still, as the first step toward action, aligns us with the presence of divine Mind that helps us look beyond immediate situations of conflict to see how God is already present. And this is what assures us of a bright year ahead.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Jan. 6, 2020, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

All aboard

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow. We’ll have your serious world news. We’ll also take a look at what makes a scientist start playing rock music … to ladybugs. It’s the kickoff of a new franchise on offbeat science.