- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The real roots of political polarization – and how to fix it

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today’s five hand-picked stories look at the latest impeachment twist, why the U.S.-China trade war is thawing, Israel’s view of U.S. leadership in the Mideast, a new bid to protect wild horses, and the remarkable language being invented by the deaf-blind community. But first, a new political discovery.

Political polarization, it turns out, might not really be what we think it is. At a time of Brexit and impeachment, we think of polarization as growing from passionate viewpoints on political policies and personalities. But a recent study suggests it might grow as much from a lack of self-awareness.

Metacognition is a fancy word that touches on how well we can analyze our own thinking. Some people, for example, have a decent sense of when they are wrong, while others don’t. It’s that second group that is much more prone to extreme political thinking, according to the study by researchers at the University College London.

Basically, political extremism seems to be connected to a confidence out of whack with accurate views. Interestingly, even when those holding extreme political views were wrong – and were given more information to show they were wrong – they reiterated their confidence in their answer.

The good news is that the solution, research also shows, is a matter of simply pausing and paying more attention to how we think. In that way, the most polarized moment in our lifetimes is likely to be fixed not alone by changing policies or politicians but by changing thought to be more honest with ourselves.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The Explainer

Trump impeachment and the Parnas Papers: three questions

The American impeachment drama has taken a fresh turn with the release of new documents. Here, we help you sort through what they mean and what their importance might be.

A batch of documents released by House Democrats on Tuesday shed new light on President Donald Trump’s pressure campaign on Ukraine.

The documents appear to strike a blow to President Trump's main defense throughout the impeachment process that has been that whatever he did, he was trying to benefit the United States as a whole, not himself. In a letter to President-elect Volodymyr Zelenskiy, Mr. Giuliani twice says that he is President Trump’s “private counsel.”

But perhaps the most shocking revelation contained in the Parnas papers deals with alleged threats against Marie Yovanovitch, the former U.S. envoy to Ukraine.

On their own the details of the communications between Mr. Parnas and his associates are very unlikely to change votes in the upcoming Senate trial or public opinion about impeachment proceedings.

But as political scientist Jonathan Bernstein wrote Wednesday, House Republicans who have voted to exonerate President Trump, and Senate Republicans who plan to, have to be worried, at least a bit. “Because if new ugly details are still emerging, who’s to say that more won’t turn up later?” Bernstein points out.

Trump impeachment and the Parnas Papers: three questions

The note is an ink scribble on letterhead from the Ritz-Carlton hotel in Vienna. On the first page, at the top, there’s a highlight star, and then a summary of the enterprise’s main point: “get Zalensky to Announce that the Biden case will Be Investigated.”

The writer? Lev Parnas, a former associate of Rudolph Giuliani, President Donald Trump’s personal lawyer. The note is part of a batch of documents provided by Mr. Parnas and released by House Democrats on Tuesday that provide new details about who wanted what, and what they asked for in return, during President Trump’s pressure campaign on Ukraine. If nothing else, the material has roiled the impeachment process against the president on the eve of his Senate trial, increasing pressure for senators to hear new witnesses and view new documents during their proceedings.

The new documents also contain menacing messages regarding Marie Yovanovitch, the former U.S. envoy to Ukraine since removed by President Trump. Whether the messages reflected a real surveillance and targeting campaign against former Ambassador Yovanovitch, directed by Robert Hyde, a Trump donor now running for U.S. Congress in Connecticut, remains unclear. But the material may help explain why she was removed suddenly from her post and told to immediately return to the United States as a matter of her own security. Here are three questions about the newly released documents.

Who was Rudy Giuliani working for in Ukraine?

One of President Trump’s main defenses throughout the impeachment process has been that whatever he did, he was trying to benefit the U.S. as a whole, not himself. This is meant to counter the charge that he was urging Ukraine to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden’s role in the country, and son Hunter Biden’s job at the energy company Burisma, for his personal political benefit.

In his July 25 call with President Volodymyr Zelenskiy of Ukraine, for instance, Mr. Trump said “do us a favor.” He has insisted that the “us” refers to the U.S. Some of the documents released Tuesday call this into question. The first note scribbled by Mr. Parnas, for instance, refers only to “Announce” in regards to an investigation of the “Biden case.” There’s no mention of actually carrying it out, or engaging in any larger fight against bribery and graft in a nation dogged by those problems in the past.

More to the point, the documents contain a letter to President-elect Zelenskiy dated May 10, 2019, in which Mr. Giuliani requests a brief meeting – “no more than a half-hour of your time.” In the letter’s first paragraph, the former New York City mayor says not once, but twice, that he is President Trump’s “private counsel,” and will be representing President Trump as a private citizen, not the chief executive of the United States.

“This is quite common under American law because the duties and privileges of a President and a private citizen are not the same,” Mr. Giuliani wrote. This makes it harder for the president to argue that in his contacts with Mr. Zelenskiy he was representing the United States in general, particularly as he urged other officials dealing with Ukraine to just work with Mr. Giuliani, as testimony from U.S. Ambassador to the European Union Gordon Sondland and others made clear during the House impeachment inquiry.

The May 19 letter also said explicitly that President Trump had “knowledge and consent” of Mr. Giuliani’s actions.

“There is no fobbing this off on others. The president was the architect of this scheme,” said House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff on Wednesday.

Was Ambassador Yovanovitch really in danger?

Perhaps the most shocking revelation contained in the Parnas papers deals with alleged threats against Ms. Yovanovitch’s personal safety.

Encrypted messages to Mr. Parnas from Mr. Hyde, a former Marine, implied that the ambassador was under surveillance, with her communications possibly tapped, and that Mr. Hyde and his associates were just waiting for a go-ahead to do her personal harm.

“They will let me know when she’s on the move,” said Mr. Hyde at one point, referring to alleged compatriots in Ukraine. “They are willing to help if you/we would like a price,” Mr. Hyde added.

Listed as head of a GOP consulting firm, Mr. Hyde is a new face in the impeachment story. His social media is full of pictures of him with President Trump, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, and other Republican Party leaders.

A lawyer for Mr. Parnas, Joseph Bondy, denied that his client was involved in any scheme to follow or harm the U.S. ambassador, and said that the emails reflected Mr. Hyde’s “dubious mental state.” Mr. Hyde himself deflected them on Wednesday with expletive-filled posts indicating the emails were composed in jest.

However, if senior officials learned of the emails and took them seriously, it could explain why Ms. Yovanovitch was removed abruptly from her post and told to take the next plane out to the U.S. as a matter of her own safety.

The document cache also contains messages written in Russian from Yuri Lutsenko, Ukraine’s top prosecutor at the time, to Mr. Parnas, in which he urges Mr. Parnas to force out Ms. Yovanovitch if he wants cooperation on the Bidens. Mr. Lutsenko was an ally and appointee of then-President Petro Poroshenko, who lost to President Zelenskiy in an election in spring 2019. He loathed Ms. Yovanovitch because she had been critical of him and supported an independent anti-corruption bureau.

“And here you can’t even remove one fool,” Mr. Lutsenko wrote to Mr. Parnas at one point, referring to Ms. Yovanovitch.

“She’s not a simple fool ... but she’s not getting away,” Mr. Parnas replied.

What happens next?

On their own the details of the communications between Mr. Parnas and his associates are very unlikely to change votes in the upcoming Senate trial or public opinion about impeachment proceedings. (If serious, the threats to Ambassador Yovanovitch could have important legal and political ramifications of their own.)

But as political scientist Jonathan Bernstein wrote Wednesday, House Republicans who have voted to exonerate President Trump, and Senate Republicans who plan to, have to be worried, at least a bit.

“Because if new ugly details are still emerging, who’s to say that more won’t turn up later?” Bernstein points out.

Since President Trump was impeached by the House on Dec. 18, 2019, The New York Times has published an extensive look at the maneuvering behind the withholding of U.S. military aid to Ukraine, moving responsibility for the decision closer to the Oval Office. The legal site Just Security obtained hundreds of pages of unredacted emails related to the aid decision, documenting alarm in the Pentagon at the action and concern that the White House was forcing the Department of Defense into collaboration on an aid block about which DoD officials had legal concerns.

Now there are the Parnas papers. Mr. Parnas has only recently been legally cleared to hand over material to Congress, his lawyers note. House officials note that more will likely be made public soon.

Inside the US-China trade deal

The trade war between the world’s two largest economies has been a drag on global growth. President Trump may have reached the limit of what tariffs can do to force China to change.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

President Donald Trump has claimed victory in his trade war with China. The two countries announced a deal Wednesday that pauses the tit-for-tat imposition of tariffs on goods traded between them, two years after Mr. Trump began to ratchet up pressure on China. The “phase one” agreement covers U.S. exports of farm goods, financial services, and manufactured goods; it also commits China to respect American trade secrets and not manipulate its currency.

It may be a hollow victory, though, that marks a pause in hostilities. Many in Washington still sees China as an economic rival that doesn’t play fair. But Mr. Trump’s strategy of imposing tariffs not only on China but also on other trading partners that run a surplus with the U.S. has made it hard to build global consensus on how open China’s economy should be. And analysts say without a broader set of diplomatic tools, the administration is unlikely to resolve the tensions at the heart of the U.S.-China impasse.

The next phase of trade negotiations with China will start later this year and may not conclude until after the U.S. election in November, which means the U.S. administration, and its priorities on trade, could change. But the tariff war with China seems to be over for now. “The tariffs as tactic? This is about as far as they are going to get the U.S.,” says Edward Alden, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington. “The tactics in phase two may be different.”

Inside the US-China trade deal

In announcing a trade deal Wednesday the United States and China have effectively called a truce after fighting to a standstill.

For now, the tit-for-tat tariff war will be replaced with a kind of armed peace, dubbed “phase one” by President Donald Trump, where both sides will lower some tariffs, but keep others in place.

At an elaborate White House ceremony, President Trump and Chinese Vice Premier Liu He signed a 90-page accord that aims to protect U.S. intellectual property; put an end to forced technology transfer to Chinese partners; reduce Chinese barriers to agricultural imports and financial services; and discourage currency devaluations. China also agreed to buy at least $200 billion worth of U.S. goods and services over the next two years.

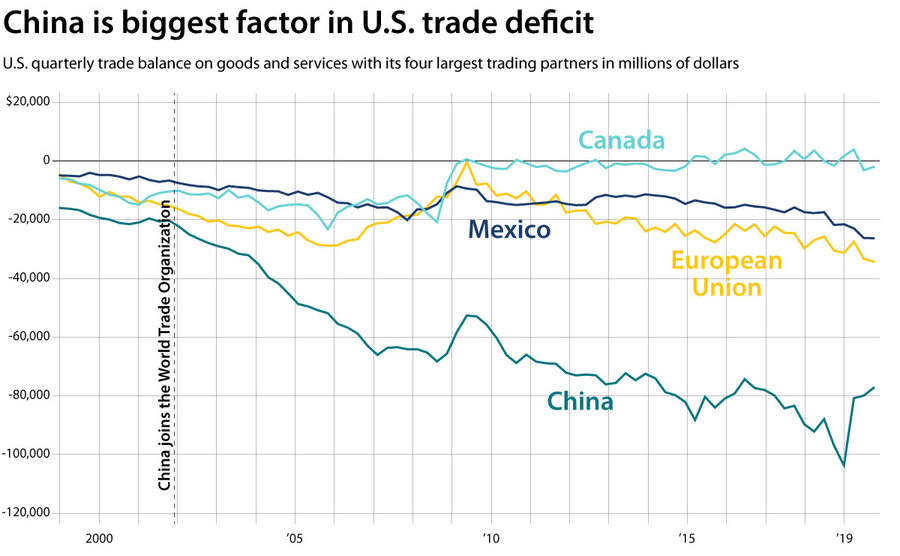

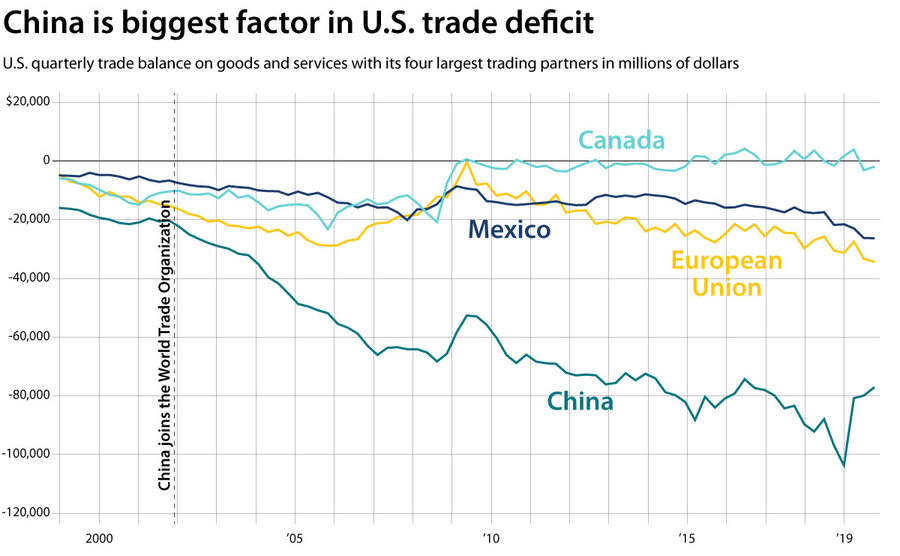

That amounts to a win for the president, who has long sought to reverse a yawning trade deficit with China that he blames for job losses in U.S. manufacturing. But the deal also illustrates the limits of his go-it-alone tariff policy. Without a broader set of diplomatic tools, the administration is unlikely to resolve more gnarly issues at the heart of the U.S.-China impasse, including subsidies and policies that favor domestic Chinese companies.

“The tariffs as tactic? This is about as far as they are going to get the U.S.,” says Edward Alden, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington. “The tactics in phase two may be different.”

By many accounts, the phase one agreement is a step in the right direction. It not only ends the bilateral escalation in tariffs, it puts in place a number of enforcement mechanisms that will make it harder for either party to renege on what they’ve agreed to. It also sets up the creation of a new dispute-resolution office.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

“You have to give the administration credit for having a broad but detailed agreement on many different elements, including having an enforcement arrangement that is specific,” says Scott Kennedy, a China expert at the Center for Strategic & International Studies, a Washington think tank.

From solar panels to steel goods

The conflict began two years ago this month when President Trump imposed tariffs on imported washing machines and solar panels; two months later he targeted steel and aluminum imports. Chinese goods weren’t specifically targeted in either action, but the actions were clearly aimed at China.

The president has long complained that China’s trade practices are unfair and the reason why the U.S. imports $380 billion more in goods and services from China than it sells there. Most economists say the deficit isn’t in itself a bad thing for the U.S. since the lower cost of goods from China is good for U.S. households and businesses. Critics of U.S. trade policy point out that the offshoring of U.S. manufacturing to China and other low-cost producers has decimated many U.S. regions.

In April 2018, Beijing struck back, with 25% tariffs on more than 100 U.S. products, including airplanes and soybeans. The U.S. escalated again in July and so on. By late last year, the Trump administration had penalized a total of $360 billion of Chinese imports and had targeted an additional $160 billion. Similarly, China imposed duties on $110 billion of U.S. goods.

That’s when both sides reached the phase one deal, putting a stop to further escalations. In the new agreement, the U.S. has pledged not to implement the tariff increases it had threatened and also will reduce its Sept. 1 tariffs on Chinese goods from 15% to 7.5% next month.

At the press conference, Mr. Liu reiterated China’s pledge to buy at least $40 billion of American farm products over each of the next two years. The deal’s signing helped drive up U.S. stocks in Wednesday’s trading.

Still, economists doubt China can live up to that $40 billion pledge on agricultural imports, let alone the $200 billion made-in-America bonanza. “There are a lot of people [who are] skeptical,” says Patrick Westhoff, director of the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute at the University of Missouri. It’s conceivable that the Chinese could effectively double the nearly $20 billion in U.S. farm goods it bought before 2018, says Mr. Westhoff. But that would mean China freezing out non-U.S. suppliers, potentially triggering trade friction elsewhere.

If reaching the phase one deal proved difficult, reaching a phase two agreement is likely to be orders of magnitude more difficult because the issues involved go to the heart of the U.S.-China dispute, namely, a sharp disagreement on how economies should operate. In the West, increased trade is generally considered a win-win; in China, it takes a back seat to national economic priorities and political oversight of the economy.

So issues such as China’s goals for technological development supported by government subsidies to companies remain unaddressed.

A broader Western agenda

One big question is how the U.S. can keep pressure on the Chinese for a phase two agreement.

One possible sign came Tuesday when the U.S., the European Union, and Japan released a joint statement calling for tighter trade rules on government subsidies to companies – a key point of ongoing friction between China and the West. The issuing of the statement points to the possibility that the administration would try to involve key allies in its push to get China to change its ways.

“This is not a problem that can be solved between China and the U.S. alone,” says Mary Lovely, a professor of economics at Syracuse University and a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “We need, need, need our allies!”

The next 12 months will be telling, says Mr. Kennedy, since the agreement aims at increasing trade between the two nations. This comes after the tariff war led some U.S. companies to move their operations out of China.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

Can Trump manage a Mideast crisis? Why Israelis have concerns.

President Trump’s decision to take out Iran’s top general has Israel talking. What is the U.S. role in the region going forward?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The U.S. killing of Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani was broadly welcomed in Israel. But for all their initial elation, Israeli national security experts are still struggling to figure out the administration’s strategy in the Middle East.

Was the killing a regional game changer that will curtail the reach of Tehran, or just a one-off assassination of a man Israelis consider an arch terrorist? And could the attack trigger a U.S. withdrawal from Iraq that, some fear, would create a domino effect?

Beyond confusion about Washington's strategic direction, there are serious Israeli misgivings about the machinery of U.S. policy. Given the turnover among the Trump administration’s senior ranks and attrition among career policymakers in executive branch bureaucracies, there are questions about whether the Trump administration can manage a serious crisis, such as the current clash with Iran.

“On the face of it, it doesn’t seem to be an ideal administration to deal with such a problem,’’ says Ephraim Halevy, a former director of the Mossad. “The decision-making process is problematic. The staff at the White House has been depleted,’’ he says. “This situation is a big-time challenge.”

Can Trump manage a Mideast crisis? Why Israelis have concerns.

In the hours after the killing of Iranian Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Israeli opposition leaders alike were quick to praise the Trump administration.

The U.S. drone strike had eliminated a hardened foe of Israel who sought, effectively, to encircle the country’s borders with hostile and well-armed proxies.

But for all their initial elation, Israeli national security experts have been left with a nagging hangover: Like Saudi Arabia and other key players in the region, they are still struggling to figure out the administration’s strategy in the Middle East.

Was the killing of General Soleimani a regional game changer that will curtail the reach of Tehran, or just the one-off assassination of a man they consider an archterrorist?

Moreover, many voice concerns about whether President Donald Trump and his administration have sufficient expert staffing and best practices to manage a military conflict against Iran, Israel’s most powerful regional foe.

At the core of the uncertainty is whether the surprise killing of General Soleimani signals a reversal by the United States, Israel’s most important ally, of a recent trend of disengagement from the Middle East.

A rising cycle of direct confrontation with Iran would be at odds with the U.S. reluctance to become embroiled in the Syrian civil war and to retaliate for attacks on regional allies like Saudi Arabia, as well as with the pullback from its northern Syria alliance with Syrian Kurds.

“I hear many, many questions about U.S. strategy in our [national security] system,’’ says Michael Herzog, a fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and a retired Israeli brigadier general whose late father, Chaim Herzog, was Israel’s sixth president. “To what extent this signals a real change of course, or [conversely] is kind of an eruption given the fact that the Iranians crossed an American red line.”

In the latter case, he says the Israelis surmise that “the U.S. will revert to its previous course, which strategically is more about retreating from the region rather than increasing its footprint.”

Trump’s popularity

President Trump enjoys overwhelming popularity in Israel for recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and taking a hard line on Iran, and for his support for Israeli annexation of the Golan Heights, the strategic plateau seized from Syria in the 1967 Middle East war. His decision to take out General Soleimani, who for decades cultivated a network of allied militias in Lebanon, the Gaza Strip, and Syria to form a forward ring of pressure around Israel, figures as another notch in his belt here.

“Israelis feel satisfaction in the elimination of Soleimani, considering all the blood on his hands, and his leadership of the regional campaign to marshal Shia forces against Israel,’’ says Daniel Shapiro, a former U.S. ambassador to Israel and a senior fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) at Tel Aviv University. “It’s consistent with an Israeli ethos of striking first at terrorist leaders.”

Mr. Trump’s public popularity and his close ties with Mr. Netanyahu make Israeli politicians and experts cautious about airing public criticism of the leader of Israel’s main ally.

Still, policy hands are more focused on Mr. Trump’s repeated declaration of his desire to be done with the “endless wars” in the region and on the actions that signaled a declining commitment. And only a few months ago, the president was flirting with the idea of negotiating with Iran.

In late December, the Israeli military chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Aviv Kochavi, complained that it would be better if Israelis weren’t the “only ones” acting against Iran.

Despite the surprise assassination, the U.S. military’s leak of a letter purporting to announce plans to withdraw from Iraq – later denied by U.S. Defense Secretary Mike Esper – only fueled those concerns.

Former Prime Minister Ehud Barak, who led an aggressive Israeli policy toward Iran as defense minister under Mr. Netanyahu, says the leaked letter represents the deeper desires of an unpredictable commander in chief.

“It’s not completely far-fetched to think that Trump would exchange blows with the Iranians – this is the main worry of allies in the region – and at a certain stage, when the blows become more serious, you wake up one day, and it turns out that Trump has ordered U.S. forces to leave,” Mr. Barak said in an interview with Israel Army Radio.

Immediately after the attack on Mr. Soleimani, Iraq’s parliament voted to order the U.S. military to leave its soil. If the U.S. were to exit Iraq in the aftermath of the killing, it would mark a backfiring of extraordinary strategic consequences, says Ambassador Shapiro and others.

“I don’t rule out that, paradoxically, [the attack] will result in the U.S. retreating from Iraq,” says Mr. Herzog. “The president could say, ‘We targeted Soleimani, [so] we can leave.’ If the U.S. government decides to leave Iraq ... there’s going to be a domino effect.”

The machinery of policy

Beyond confusion about the strategic direction of Washington in the Middle East, there are serious Israeli misgivings about the machinery of U.S. policy.

Given the turnover among the Trump administration’s senior ranks and attrition among career policymakers in executive branch bureaucracies, there are questions about whether the administration has the ability to handle a serious crisis.

“On the face of it, it doesn’t seem to be an ideal administration to deal with such a problem,’’ says Ephraim Halevy, a former director of the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad.

“The decision-making process is problematic. The staff at the White House has been depleted. The number of people involved in the National Security Council is much less than it was before,” he says. “This situation is a big-time challenge.”

Looking to another region, Mr. Trump’s foreign policy flirtation with North Korea and the lack of results from U.S. negotiations with leader Kim Jong Un also don’t inspire confidence, says Ehud Eiran, a political science professor at Haifa University and a visiting scholar at Stanford University.

“It seems that the whole machinery isn’t exactly rational. The general pattern of decision-making is not based on process,’’ Professor Eiran says. “There is no input from the national security bureaucracy, no coordination. Big dramatic moves aren’t followed with any achievements.”

The large list of potential actors and complex matrix of alliances in the Middle East make the task of calibrating U.S. actions all the more challenging, he adds.

Danger of miscalculation

While security experts believe it’s likely that Iran will avoid direct retaliation against Israel in order not to provoke a counterattack, they still worry about Israel becoming embroiled in unintended escalation between the U.S. and Iran.

Indeed, even before the strike against General Soleimani, Iran’s presence in Syria and its support for Hezbollah in Lebanon stoked considerable tension along Israel’s northern border. Now, Israel will have to factor in the flammable aftermath of that targeted killing when it decides whether to hit Iran or its allies, such as a deadly attack on an air base in the Syrian province of Homs Tuesday that Damascus accused Israel of carrying out.

According to a report Wednesday in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, Israel’s Military Intelligence branch sees the current U.S.-Iran clash as creating an opportunity for Israel to strike at Iranian and allied targets, even though it expects Iran or Hezbollah would respond to any fatalities.

“We are closer to the threshold of escalation, and the probability or prospect of miscalculation is much higher than it was before the assassination,” says Kobi Michael, a fellow at INSS.

“If Israel needs to operate, it will be a good reason for these militias to retaliate much more aggressively. And we will find ourselves on a slippery slope.”

To read the rest of the Monitor’s coverage of the U.S.-Iran clash, please click here.

A deeper look

Taming an American icon: A plan to curb wild horses, and save the West

The United States goes to extraordinary lengths to save wild horses. The most extraordinary step of all, however, might be finding a solution that strikes a balance between ranchers and nature, too.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

Wild horses may be beloved in America, but to some, they’re also a nuisance – a remarkably fecund one, with a population that grows by about 20% a year, wreaking havoc on rangeland vital to ranchers and other wildlife. Estimates put the wild horse and burro population at 88,000 to 100,000 on public lands as of this past spring. That’s more than three times the target population of 26,700 that the U.S. Bureau of Land Management believes can be sustainably supported.

With limited resources and management options, the BLM is trying to handle the horses through a piecemeal solution of roundups, adoptions, and maintenance on taxpayer-funded private lands. But it’s an expensive system that satisfies no one and is leading to growing populations of horses.

Now, for the first time in years, there are glimmers of a solution. A broad coalition – including animal-welfare groups and ranching organizations – has put out a plan that it believes offers a way forward.

“It’s like a runaway freight train, and it’s not easily solved,” says Dean Bolstad, who worked for the BLM for 44 years. “I can’t tell you how important [dealing with these animals] is to the health and well-being of public lands.”

Taming an American icon: A plan to curb wild horses, and save the West

When the first wild horses come into view, thundering through high desert sagebrush, it’s easy to imagine they’re in the American West of 150 years ago. This part of Nevada is desolate and beautiful: massive plains that stretch for miles without a building – or tree – in sight, rugged snow-gauzed mountains piercing the sky.

But if the idea of wild horses is a romantic one in America, conjuring images of unfettered freedom and unfenced spaces, the reality, in today’s West, is far more complicated. These horses – herded by a helicopter and headed for relocation to private pastures or adoption – lie at the nexus of a human-wildlife conflict that is one of the most incendiary in the West. It is a dispute rife with emotions and with little common ground.

Wild horses may be beloved in America, but to some, they’re also a nuisance – a remarkably fecund one, with a population that grows by about 20% a year, wreaking havoc on rangeland vital to ranchers and other wildlife. Estimates put the wild horse and burro population at 88,000 on public lands as of this past spring, though most experts say it’s now closer to 100,000. That’s more than three times the target population of 26,700 that the U.S. Bureau of Land Management believes its herd management areas can sustainably support.

With limited resources and management options constrained by law, court order, and public opinion, the BLM is trying to handle the horses through a piecemeal solution of roundups, adoptions, and maintenance on taxpayer-funded private lands. But it’s a system that satisfies no one, is expensive, and is leading to growing populations of horses both on and off public rangeland.

“It’s like a runaway freight train, and it’s not easily solved,” says Dean Bolstad, who retired from the BLM in 2017 after 44 years with the agency. “I can’t tell you how important [dealing with these animals] is to the health and well-being of public lands.”

Now, for the first time in years, there are glimmers of a solution. A broad coalition – including both animal-welfare groups and ranching organizations – has put out a plan that it believes offers a way forward. It expands roundups and adoptions in the short term, and proposes a massive increase in fertility control measures to keep populations stable in the long term. The downside: It’s expensive (and requires congressional allocation of funds) and faces fierce criticism from major wild horse advocacy groups, which believe that the plan will pave the way for slaughtering the animals.

Still, those involved in formulating the plan say it represents a monumental undertaking in which groups used to warring with each other worked hard to lay aside differences.

“It was painful. ... No one liked the information once we dug into these numbers,” says Celeste Carlisle, a biologist with the wild horse advocacy group Return to Freedom, which has taken some flak from other horse groups for its endorsement of the proposal. “But nothing is going to be achieved unless you actually listen to what people are saying, and listen without your own biases.”

This is a debate that on the surface is about animals and public lands but is more fundamentally about people and values. That’s a big reason why finding a resolution has been so hard.

J.J. Goicoechea, a fourth-generation Nevada rancher who was also part of the Path Forward proposal, says it’s been challenging getting ranchers to agree to the compromise as well. But, like Ms. Carlisle, he thinks a plan with broad support is the only option. Mr. Goicoechea says he understands the emotional attachment to wild horses that lies at the root of the debate. “We’re not anti-horse,” he says. “They’re a part of the American West. The West evolved with the horse. Unfortunately, they’re now taking over, and the West is evolving again.”

For an animal that seems quintessentially American, the wild horse is actually not native, and technically, not wild. Today’s wild horses all descended from domesticated horses, many brought over by the Spanish in the 1500s, intermixed with a variety of other breeds. But with a durable recent history and an even longer ancient history – their ancestors roamed Wyoming 3 million years ago, and horses may not have disappeared completely from North America until about 10,000 years ago – some horse lovers prefer to refer to them as a “reintroduced” species.

“They represent the West,” says Greg Hendricks, director of field operations for the American Wild Horse Campaign, out in the Desatoya range to observe the recent December roundup. “They earned a spot. They fought in our wars, did all the things that you would expect to earn a spot. And that’s why I work to try to keep them here.”

Wild horses are charismatic and easy to love. They also happen to reproduce quickly – starting at a young age and continuing throughout most of their lifespan – and have few natural predators. When forage is scarce, they’ll eat what’s available down to the root, making it difficult or impossible for vegetation to recover.

Wild horses also enjoy an extraordinary amount of protection. A massive public campaign in the 1950s and ’60s helped get the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act adopted in 1971, setting the baseline for the current management system and making it illegal for private citizens to round up, herd, or kill horses. Subsequent congressional action and court cases have also limited management options – most notably, ensuring that no horses on federal land end up killed or sold to slaughterhouses in Mexico or Canada.

Herd management areas, or HMAs, exist in 10 states, but Nevada, with more than half the wild horses in the United States, is ground zero in the conflict. In the Desatoya management area, where the action is focused on this blustery day, the BLM has determined that the “appropriate management level” is between 127 and 180 horses. As of July, the herd numbered about 560.

Ray Hendrix, the main rancher with grazing allotments on these rangelands, expresses frustration about what the horses are doing to the land. In late August, he visited what he calls the “lower country,” where he planned to graze some of his 900 cows this winter. He was thrilled to see abundant “winterfat” – a nutritious shrub that makes for excellent winter forage.

“I thought, this is fabulous. We’ll turn out this fall and there will be a lot of feed,” says Mr. Hendrix, a no-nonsense rancher in a baseball cap and Carhartt jacket. “Then I go back in October and it’s all gone. The horses ate it.”

He’s hopeful that since the BLM is removing horses, the natural scrub will revive. But in some places, particularly along rivers and streams, he’s seen damage that he thinks can never be undone.

Like most ranchers in Nevada, Mr. Hendrix grazes his cattle almost exclusively on public lands. He’s trying to use the landscape responsibly. But the horses, he says, make that challenging.

“How do you deal with something you can’t manage?” he asks. “Even if we herd those horses, we’re breaking the law. ... Just think of what 600 animals that you cannot manage are going to do to the resource.”

For many horse advocates, the problem isn’t the wild mustangs. It’s the cattle. The horses, they argue, have more of a right to these lands than the cows. But even for those activists who acknowledge that burgeoning horse populations are an issue, they’re troubled by the trauma of helicopter roundups and the lack of serious efforts to use fertility controls. They see management practices tipped against the horses.

Steve Paige, a quiet man with white hair, attends as many of the BLM “gathers” as he can, wielding a camera with a long lens to document the process. A field representative for the American Wild Horse Campaign, Mr. Paige hopes that his presence adds a layer of accountability to the operation. At the Desatoya roundup, he mixes easily with the BLM employees, though at some of the other gathers, he acknowledges, “they hate me.”

Mr. Paige lives in Reno, Nevada, but his first involvement with horse advocacy came almost 30 years ago, when he lived in Los Angeles. He attended an auction and saw one man buying up as many horses as he could, for $300 apiece, with the intent, he presumed, of selling them for slaughter. When the man bid on a small Arabian, Mr. Paige suddenly found himself bidding on it, too – with no way to transport or board the horse.

“She was the most beautiful horse I had seen,” he says. “My only regret is that I couldn’t buy more that day.”

The Desatoya gather goes relatively smoothly. On the first day, about 80 horses are rounded up, and then separated into gender-separate groups. The first band has a foal with it, but the helicopter moves the herd slowly enough that the foal can keep up. As the horses near the trap site, contractors release a “Judas horse” – a trained mustang that runs into a fenced-off area luring the wild band with it.

Mr. Paige says he’s seen horses run so fast that foals can’t keep up and die overnight. “There’s good days and bad days,” he says. His style with the BLM handlers is reserved rather than confrontational, and when he sees a potential problem, such as barbed wire near the pen site, he suggests they mark it to ensure horses don’t get hurt.

Ken Collum, manager of the BLM’s field office in Stillwater, Nevada, is overseeing this gather. A geologist with a dry sense of humor, he peppers his conversations with anecdotes from his years working in Central America. As he observes the progress of the roundup, he fields regular calls both from his office in Carson City and from the Navy, which is conducting jet fighter exercises overhead. Contrails slash the skies as the horses run below.

The toughest aspect of wild horses, says Mr. Collum, is seeing how hard they are on the land as well as the constraints they put into any management plan.

“We don’t manage species – except horses, for some reason. We manage the habitat,” says Mr. Collum, as he drives through the lands adjacent to Mr. Hendrix’s ranch, stopping periodically to note where cheatgrass, an invasive annual plant, has taken over. Most of these lands have been overgrazed for years and bringing them back to health is already challenging, he says. Growing horse populations affect “our ability to manage grazing and just about everything.”

A few weeks earlier, mustang lovers and BLM officials were gathered in Ardmore, Oklahoma, for one of the least controversial portions of any wild horse solution: an adoption event. Emotions run high here, too, but in this case, they’re positive. Potential adopters eagerly look over untamed horses in pens; past adopters have brought their mustangs with them for an annual horse show.

In corrals, groups of eight to 10 mustangs stand together, wary of anyone who approaches. Handlers separate the ones already claimed, pushing them into chutes and eventually waiting trailers.

Kayden Laymance, tall and blond, with braces, a black cowboy hat, and an irrepressible grin, watches excitedly as two horses get loaded up. The 14-year-old says she has wanted to adopt a mustang ever since she first came to this event three years ago. Her family has three horses at their farm in Gainesville, Texas, and Kayden has worked with “problem” horses before, but these will be the first she’s broken entirely by herself. “I’ve never gotten to start a horse,” she says. “I get to put the first ride on it. It’ll be awesome.”

This is what the BLM would like to see: more mustangs off the range and adopted by responsible owners. But finding homes in enough numbers has always been a challenge, and BLM officials acknowledge that adoption, by itself, can’t solve the problem. Still, this year, in an effort to boost the process, the BLM began offering an incentive: It will pay up to $1,000 to anyone who adopts a horse. Adoptions, which were flagging, have started to climb. In fiscal year 2019, people took home more than 7,000 horses – the highest number since 2005 and a 54% increase over the previous year.

The incentive program wasn’t the main reason the Laymances decided to adopt their mustangs, but it helped. Money can be tight in a family with seven children, and Whitney Laymance, Kayden’s mother, hopes the stipend will offset some of the costs of caring for the horses.

But mostly Ms. Laymance is excited about what this means for Kayden. “This is our mom-daughter project,” she says. “It’s giving my daughter and me the gift of bonding over what we are both most passionate about.”

Past adopters are, if possible, even more enthusiastic. Carol Wandell, who teaches horseback riding in Gainesville, has been working with mustangs for about 30 years – ever since her son, at age 13, decided he wanted a horse and bought an untrained mustang from a friend. “It took two years before my son could even ride the horse,” she laughs. “We had no idea what we were getting into.”

Over the years, she and her daughter-in-law have adopted about 15 horses and burros, and breaking them has been a rite of passage for several of her grandchildren. “It transforms the kids,” she says. “Every time I go to one of these places, there always seems to be one that touches my heart, and you end up bringing it home.”

Still, adoptions, even in increased numbers, can’t reduce the populations to a sustainable level. Many of the horses instead end up on private lands, at a cost to taxpayers of nearly $50,000 per animal over the course of its lifetime. Currently, about two-thirds of the BLM wild horse and burro budget goes to maintaining these horses.

For the animals, it’s not a bad life. At Mowdy Ranch Mustangs in Coalgate, Oklahoma, more than 360 mares roam a 4,000-acre ranch. They graze and gallop amid grasslands, woods, and rolling hills.

When they first got there, Clay Mowdy notes, many of the horses were terrified of trees. Now they’ve adjusted to the environment, just as others have adjusted to the presence of people. (The Mowdys run a guest ranch.)

Occasionally, says Mr. Mowdy, activists come who are certain the horses must be suffering. “They leave happy,” he says, as he drives over the ranch in a pickup, two of his dogs in the back. “I don’t think we’ve ever had anyone that’s gone away without their position changed quite a bit.”

The big, but often unspoken, issue surrounding wild horses is slaughter. Plenty of people who have worked on wild horse issues for years acknowledge that killing them would be the most cost-effective and efficient way of dealing with overpopulation.

But even those who favor it as a solution admit it’s unlikely that it will ever be politically palatable. Horses are too beloved; the scenes of their suffering in slaughterhouses in Mexico or Canada too vivid. Killing horses “is not going to fly,” says Mr. Bolstad, the retired BLM official.

With that option unavailable, most experts agree that a massive investment in some sort of fertility control has to be a centerpiece of any plan going forward. But it isn’t easy to do. While the vaccines used are improving, a large number of mares in a herd – perhaps 80% – need to be treated to actually keep population growth in check. The initial vaccines don’t last long. A second booster shot is more effective, but rounding up horses is expensive, and by the time a second shot is given, many of the original mares have had foals, which are also producing offspring.

“It’s like trying to plug a dam with your finger,” says Mr. Hendrix, the rancher.

But critics of the BLM argue that the agency has never truly given fertility control a chance, other than with a handful of small herds. The longer-acting version of PZP, the most common fertility vaccine, has been in use since 2004, notes John Turner, an endocrinologist at the University of Toledo who has been working with vaccines for decades. “The BLM created the crisis by not taking action. ... They’ve had 15 years to do something about it, and they’ve just continued to do what they do,” says Dr. Turner.

The American Wild Horse Campaign recently began working with the state of Nevada to manage a herd of 3,000 horses on state land outside Reno. In just seven months, spokeswoman Grace Kuhn says, 14 volunteers have injected over half the mares with vaccines – more horses than the BLM treated nationally. While initiatives like this are impressive, many believe it will take a multifaceted approach to solve the overall wild horse problem, something like the Path Forward proposal of the coalition.

“This is our best effort to come up with something that can change and revolutionize this program,” says Stephanie Boyles Griffin, a senior scientist at the Humane Society of the United States.

Through an increase in roundups, expanded adoptions, relocating unadopted horses to more cost-effective pastures, and – most importantly – treating about 90% of the mares returned to the range with fertility measures, the groups believe they can get numbers to more reasonable levels within 10 years.

The problem with this approach, say critics, is that it will cost so much in the short term that it will lead inexorably back toward slaughter. For wild horse advocates like Ms. Kuhn, that is a practice that should never be broached again. “This Path Forward is the antithesis of that,” she says.

A day after the Desatoya roundup, the corralled horses inhale hay in their new surroundings at an adoption facility outside Reno. The small foal is still with its mother. What will happen with it next – a new home with someone like the effervescent Kayden Laymance, a new life on a cinematic ranch like Mowdy’s?

The 1971 law designed to protect wild horses called them “living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West.” But finding a compromise between those idealistic values and the pragmatism of the people who use the West’s vast public lands defies easy solution. What everyone agrees on is that the current path is untenable – and maybe that alone is enough to inspire a way out.

Mr. Goicoechea, the Nevada rancher, explains the futility of the status quo with characteristic grit. “I’ve seen horses eat sagebrush down to the stump,” he says. “I’ve seen them eat their own manes and tails.”

While it’s easy to view this issue through the lens of extremists on both sides, the reality is most people realize its complexities; they just come down differently on whether to tilt the scales toward horses, ranching livelihoods, or the overall ecosystem. Ms. Boyles Griffin, who works on numerous “human-wildlife” conflicts for the Humane Society, says this one is the most challenging.

“All of the stakeholders involved are driven by unique values and attitudes toward wild horses for good or bad,” she says, “and people have a tremendous amount of identity associated with their view of how these animals should be managed.” In the broad middle, she says, are people who care about both horses and the land, and want to make sure they’re managed humanely and sustainably. “I think the majority of people on this issue want that; they just have different opinions on how to get there.”

Watch

In one revolutionary language, a community taps the power of touch

For deaf-blind people, sign language has long been a meager way to feel the connections that sight and sound convey. This is the story of their amazing efforts to create their own language based on touch, transforming how they relate to each other and the world.

A new language centered around touch is spreading within the deaf-blind community and revolutionizing how its members communicate.

Protactile, or PT, emerged in Seattle in 2007, when a group of deaf-blind people began exploring their natural tactile instincts. PT is not meant to be heard or seen, like other forms of sign language. Instead, the speaker articulates a message by applying different touches to the receiver’s hands, arms, and other parts of the body. Today, thousands of people have expanded PT’s reach, and the language continues to evolve as new expressions emerge, unique to PT and derived from deaf-blind people’s experiences.

Jaimi Lard, a deaf-blind woman who works as a public speaker at Perkins School for the Blind, says languages like American Sign Language were created to be seen, not felt. This led to misunderstandings as she tried to communicate with others, as she often participated in conversations without fully grasping what was happening. But with PT, “we are able to be included in more,” says Ms. Lard in ASL.

Ms. Lard and her hearing and sighted interpreter, Christine Dwyer, have incorporated elements of PT in their communication. “I’ve known [Jaimi] for 30 years,” says Ms. Dwyer at a recent talk she gave with Ms. Lard. “Seeing the difference that Jaimi and I have been able to do in our communication in the past year is just amazing.”

Note: This video is meant to be watched, but we understand that is not an option for everybody. For those who are unable to watch or listen, we have provided a transcript of the video here.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why Europe seeks to fix Libya – for its own future

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

On Sunday, German Chancellor Angela Merkel hosts a high-level summit in Berlin to end the civil war in Libya, a major conduit for migration to Europe. Last year, nearly 95,000 people crossed the Mediterranean from both Libya and Turkey. The current fighting in Libya threatens to turn it into a failed state – or a “second Syria” – and end its fledgling attempts to curb migration from the rest of Africa.

At the summit, Ms. Merkel will not only be balancing Europe’s competing views of migration. She will also be dealing with foreign meddling in Libya by Russia, Turkey, Egypt, and many other countries.

Ms. Merkel, like the European Union, has been on a long learning curve about migration. The issue even played into Britain’s vote to exit the EU. Within Germany, Ms. Merkel’s chosen successor, Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, has called on politicians to value “the binding over the divisive.” At Sunday’s summit, Ms. Merkel will try again to seek common ground for peace in Libya so that her own country and the EU can find peace on the divisive issue of migration.

Why Europe seeks to fix Libya – for its own future

Europe’s destiny, Angela Merkel often says, could be determined by the way it deals with mass migration. Indeed, the German chancellor’s own future was determined by how she dealt with nearly a million people flooding Europe from Africa and the Middle East four years ago. She welcomed them. By 2018, anti-immigrant politics had forced her to announce she will step down in 2021 – but not before she once again tries to shape the way migrants enter Europe.

On Sunday, Ms. Merkel hosts a high-level summit in Berlin to end the civil war in Libya, a major conduit for migration. Last year, nearly 95,000 people crossed the Mediterranean from both Libya and Turkey. At least 1,200 died during the treacherous journey. The current fighting in Libya threatens to turn it into a failed state – or a “second Syria” – and end its fledgling attempts to curb migration from the rest of Africa. About 600,000 migrants are currently stuck in the country.

At the summit, Ms. Merkel will not only be balancing Europe’s competing views of migration. She will also be dealing with foreign meddling in Libya by Russia, Turkey, Egypt, and many other countries. Last week, Turkey and Russia tried to arrange a truce in the war but failed.

Libya, whose longtime dictator Muammar Qaddafi was ousted in 2011, is an oil-rich Arab nation under threat from Islamic radicals lying north of some of Africa’s poorest and more terrorism-troubled countries. In fact, the Pentagon refers to much of northern Africa as “the arc of instability.” Ms. Merkel has pushed the European Union to send money and troops to the region to attack the root causes of African migration. “Africa needs a self-supporting economic boom,” she said on a trip to the continent last year.

Much of her effort to deal with the migrants already in Europe and to stem the flow of new ones has had some success. But now Libya’s near-collapse could open the floodgates again. In addition, the World Bank estimates climate change will force 86 million people in sub-Saharan Africa to migrate by 2050. Many would attempt to reach Europe.

Ms. Merkel, like the EU, has been on a long learning curve about migration. The issue even played into Britain’s vote to exit the EU. Within Germany, Ms. Merkel’s chosen successor, Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, has called on politicians to value “the binding over the divisive.” At Sunday’s summit in Berlin, Ms. Merkel will try again to seek common ground for peace in Libya so that her own country and the EU can find peace on the divisive issue of migration.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Can love save a life?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Deborah Huebsch

The realization that God is Love, ever present and forever embracing us, brings healing and renewal to every aspect of our lives.

Can love save a life?

The latest public health crisis, according to Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, California’s surgeon general, is what is termed ACE – or adverse childhood experience. She says that more than 60% of all adults suffer from the effects of childhood trauma, resulting from abuse, neglect, or parental mental illness, alcohol or substance abuse, or divorce. Doctors report that the body gets wired by childhood stresses in ways that lead to sharply increased risk of serious disease.

However the medical community also acknowledges that loving, stable relationships can have a very positive impact and can help reverse the negative effects of difficult childhood experiences – for both children and adults. This report struck deep when I heard it, because every determining factor for ACE was present in my childhood. However, I found complete healing and have lived a life free of the predictions for those having suffered adverse childhood experiences. How is that possible?

I was introduced to Christian Science just after I turned 21. As I began to read “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, two sentences jumped off the pages – and changed my life. They were both about love – God’s love.

One reads, “Love is impartial and universal in its adaptation and bestowals” (p. 13). The other says, in part, “Love supports the struggling heart until it ceases to sigh over the world and begins to unfold its wings for heaven” (p. 57). These passages went deep because love was something I’d never experienced or even ever expected to experience. But I began to see that love is something that everyone, everywhere can know and feel – even me.

Through my continued study of Christian Science, I learned about a loving and nurturing God, the Love that embraces all impartially, and includes no negative elements. This God was right at hand to help and heal the effects of an adverse childhood experience. I also learned that whatever is created by divine Love, God, which includes you and me, must be spiritual and therefore all good and worthy of love. This truth of our inherent spirituality is the basis for our ability to feel and know God’s love in our lives.

Christian Science reveals that God’s love is not something that comes and goes according to the events in one’s life; His love is constantly there for us. God’s love is a fundamental fact we can turn to. It’s an actual law. It’s consistent, reliable, powerful. And it’s always present to be experienced. As we pray to understand God better, we feel the actual presence of Love, God, in our lives.

I found great solace and comfort in learning about God’s love. And I found that this love of God became evident in amazing and concrete ways. For the first time ever, I began to have relationships that were loving, caring, kind.

All this love that originated with God seemed like a fountain that poured forth healing. It cleansed me of the effects of childhood trauma, both mentally and physically. I found a life of health, purpose, and joy. It didn’t happen overnight, but I made steady progress, and freedom proved to be inevitable.

When we understand genuine love as ultimately derived from the divine, unlimited source, we can prayerfully affirm its availability for everyone. Hearts and bodies can be healed by recognizing this law of Love and its regenerating effects. So can love save a life? The answer is yes.

A message of love

All tucked in

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. We hope you’ll come back tomorrow when we look at Vladimir Putin’s plan for Russia after he steps down as president. Unexpectedly, it points in a direction that might actually bolster democracy.