- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

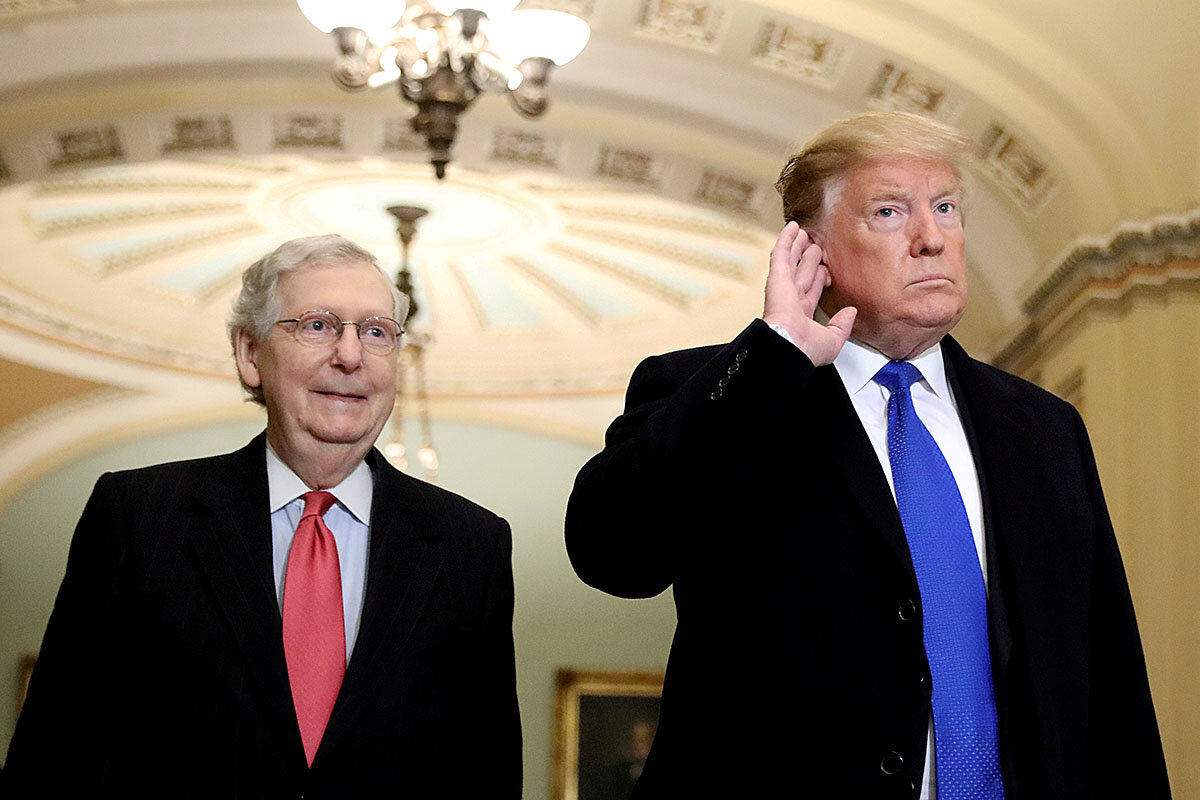

- Trump and McConnell: Political odd couple turned powerful partnership

- Sanders gains strength – and mainstream Democrats worry

- Why Egypt’s President Sisi is rushing to embrace country’s youth

- Yesterday, he sang for guerrillas. Today, he answers to mayor.

- This African group’s music champions rights – and love

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The Monitor as partner, not gatekeeper

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today’s stories look at Washington’s impeachment power couple, the uncertainties about Bernie Sanders, Egypt’s new response to a Mideast crisis, a path to reconciliation in Colombia (maybe), and music empowering African women.

Last Wednesday, we hoped we were doing the responsible thing. You might have seen the video we published on members of the DeafBlind community crafting a language that speaks to their remarkable talents and perception of the world. It was genuinely moving.

When it came to identifying the community, however, our style guides pointed us to “deaf-blind,” even though producer Jingnan Peng’s conversations with the community suggested the term was outdated. To many, “deaf-blind” is medical language that dwells on their condition and its seeming limitations. “DeafBlind” speaks of their ability and agency. The word choice was more than style, it was a statement of how we saw them.

Last week, we chose “deaf-blind.” This week, we have switched.

My first day in Journalism 101, my teacher told us we would decide what was news. We were the future information gatekeepers. That vision is all but gone. You all have Google now. What the Monitor can be is a partner, working with you to bring its unique gifts to your doorstep. And that means being a partner with those whom we report on, too – and listening to the best of what they have to say.

DeafBlind speaks to “who we are,” says Debra Visser Kahn, administrator of the DeafBlind Autonomy Facebook group. “It’s our cultural identity, and we feel it best represents our community.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Trump and McConnell: Political odd couple turned powerful partnership

The Senate impeachment trial has brought together two men with stark differences in personality and style. But they do see eye to eye on one thing: winning.

When Donald Trump became president, he and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell were wary of one another. To some in the Trump camp, it doesn’t get any “swampier” than Mr. McConnell – now finishing his sixth term in the Senate.

But over time they've developed a mutual respect. Through experience – passage of major tax reform and the confirmation of a record number of federal judges, including two Supreme Court justices – President Trump has learned that Mr. McConnell’s advice is worth listening to. Both men are all about winning, whether in elections or on legislation and confirmations or, now, in ensuring that Mr. Trump survives an election-year impeachment trial with party unity intact.

This hard-fought alliance now faces a major test in the Senate trial, which began in earnest Tuesday. Namely, will Mr. Trump continue to defer to Mr. McConnell, or will he muddy the messaging at this high-stakes juncture in his presidency?

“The president, I think, sees Mitch as a Class A operator,” says Chris Ruddy, CEO of the conservative Newsmax Media and a longtime friend of Mr. Trump, in an email. “He’s also a pretty frank guy, and I know the president appreciates that candidness.”

Trump and McConnell: Political odd couple turned powerful partnership

They are perhaps the ultimate Washington odd couple.

One is a charismatic showman who operates on gut and instinct. The other is low on charisma and shrewdly calculating. One is a political outsider who has remade the Republican Party in his own populist image. The other embodies the GOP establishment.

Yet despite some high-profile clashes – punctuated by angry tweets – President Donald Trump and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky have made their relationship work. Foremost, they’re both all about winning, whether in elections or on legislation and confirmations or, now, in ensuring that President Trump survives an election-year impeachment trial with party unity intact.

Through experience – passage of major tax reform and the confirmation of a record number of federal judges, including two Supreme Court justices – Mr. Trump has learned that Mr. McConnell’s advice is worth listening to.

“The president, I think, sees Mitch as a Class A operator, a master of the Senate, who has helped him tremendously to move his legislative agenda through,” says Chris Ruddy, CEO of the conservative Newsmax Media and a longtime friend of Mr. Trump, in an email. “He’s also a pretty frank guy, and I know the president appreciates that candidness.”

Mr. Ruddy acknowledges that when Mr. Trump became president, the two men were “somewhat wary of each other.” But over time they’ve developed a mutual respect. “They both like winners and put a value on getting things done,” he says.

This hard-fought alliance now faces a major test in the Senate trial, which began in earnest Tuesday. Namely, will Mr. Trump continue to defer to Mr. McConnell, or will he muddy the messaging at this high-stakes juncture in his presidency?

Since his Dec. 18 impeachment on charges of abuse of power and obstruction of Congress, Mr. Trump has sent mixed signals on what he wants – from “outright dismissal” of the articles of impeachment to the calling of Democratic witnesses, including former Vice President Joe Biden, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff.

Mr. McConnell has said that an effort to dismiss the case would fall short, to the president’s embarrassment. Furthermore, for Mr. Trump, being acquitted after a trial sends a stronger reelection message than a dismissal, presidential allies argue.

Mr. McConnell and Mr. Trump’s lawyers oppose the calling of witnesses; Democrats want to call four, including former national security adviser John Bolton and acting Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney, and question them about Mr. Trump’s alleged quid pro quo with Ukraine to help in his reelection effort.

For now, the McConnell game plan, in conjunction with the Trump lawyers, is in effect. But with the mercurial Mr. Trump, one can never be sure what he might say or do.

Indeed, for all their shared goals, the two men can seem at times from different planets. The key to making any joint Trump-McConnell venture work, say sources connected to each, is to acknowledge those differing styles and take advantage of the best of each.

“McConnell’s not a golfer, McConnell’s not a backslapper,” says Scott Jennings, a former campaign aide to Mr. McConnell from Kentucky. “Think of them as a corporation. Someone’s got to work in sales and marketing and someone’s got to work in product engineering.”

At the same time, Mr. Trump’s alliance with Mr. McConnell reflects a pragmatic streak in the president, a willingness to compromise on his stated goal of “draining the swamp” – that is, changing the way Washington works. Because to some in the Trump camp, it doesn’t get any swampier than Mr. McConnell – now finishing his sixth term in the Senate and expected to win his seventh in November. Former aides to Mr. McConnell are all over Washington, working as lobbyists and consultants.

Ken Cuccinelli, a Trump acolyte and top official at the Department of Homeland Security, once called Mr. McConnell the “head alligator” in the swamp.

That type of rhetoric may have resonated with Mr. Trump when he first arrived in Washington. Certainly, the early going between the two was rough. In July 2017, when the Senate failed to repeal the Affordable Care Act, Mr. Trump was furious – spurring a month of severely strained relations, punctuated by angry presidential tweets slamming Mr. McConnell by name. A phone call between the two men reportedly descended into a profanity-laced shouting match, followed by weeks of no contact.

Mr. McConnell faced other sources of frustration that summer, including Mr. Trump’s controversial reaction to protests by white supremacists in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the president’s open antagonism toward some of Mr. McConnell’s GOP Senate colleagues.

Complicating matters was the position of Mr. McConnell’s wife, Elaine Chao, as transportation secretary. When asked that summer about the tensions between her husband and Mr. Trump, she said, “I stand by my man – both of them.”

By the end of the summer, the two men had patched things over. Populist bomb-thrower Steve Bannon, a major McConnell antagonist, was out as Mr. Trump’s chief White House strategist, and tax reform was on its way to passage. The president’s mood was brightening.

On the effort to repeal “Obamacare,” “McConnell got it as close as he could, but the votes weren’t there,” Mr. Jennings says. “From that day forward, they’ve been hand in glove on just about everything.”

Last year, Mr. McConnell even gave himself a nickname – the “Grim Reaper” – as he promised to defeat all progressive proposals in the Senate.

At this point, “McConnell is probably one of his best advisers, and Trump probably realizes that,” says Al Cross, a former longtime Louisville reporter, now at the University of Kentucky in Lexington.

For Mr. Trump, having an ally who doesn’t compete for the spotlight is a plus. Mr. McConnell is famously taciturn, and keeps his own counsel.

“McConnell keeps things close to the vest, even with his own leadership team. He doesn’t make decisions on the fly,” says Jim Manley, who ran communications for former Democratic Senate leader Harry Reid. “In meetings between Reid and McConnell, neither of whom are known for eloquence, Reid was always the more loquacious of the two.”

Also working in Mr. McConnell’s favor may be the fact that he isn’t quite the “institutionalist” that some make him out to be.

He resisted Mr. Trump’s entreaties to get rid of the legislative filibuster, so he could pass bills with a 51-vote majority in the Senate and not 60 votes. But when it came to another Senate tradition, filling a Supreme Court vacancy expeditiously, Mr. McConnell was willing to break the mold. He refused to hold a hearing or a vote on President Barack Obama’s nominee – Merrick Garland, named in March 2016 – saying the next president should fill the vacancy.

The gambit paid off after Mr. Trump won the election, allowing him to name a conservative to the high court. In all, Mr. McConnell has overseen the confirmation of 187 federal judges, ensuring a conservative judicial legacy that will last decades. Of all the impacts from the Trump-McConnell partnership, that may be the biggest of all.

To see all of The Monitor's impeachment coverage, go here.

Sanders gains strength – and mainstream Democrats worry

Could Bernie Sanders win the Democratic nomination and then get routed in the general election because he’s seen as too liberal? That concern lurks. Then again, 2016 blew up the political playbook.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

With just 12 days until the Iowa caucuses and a dominant front-runner yet to emerge, what once struck many as an unlikely outcome – “Democratic nominee Bernie Sanders” – is suddenly looking like more of a possibility.

Mr. Sanders’ polling strength is eliciting anxiety within certain quarters of the Democratic Party not unlike the reaction many Republicans had in 2016 to another party outsider: Donald Trump. The worry: A “far-left” nominee could backfire for Democrats.

“I do believe that Senator Sanders is too liberal to defeat an incumbent Republican president, especially an incumbent president with a good economy and a huge bankroll,” says Marshall Matz, a registered Democrat who worked on the failed 1972 campaign of George McGovern.

But like President Trump, Mr. Sanders’ promise to upend Washington has attracted a passionate group of followers.

“The ironic similarity between Bernie and Trump is that they both have clear messages,” says Iowa-based Democratic strategist Jeff Link. “[Bernie] is incredibly clear and consistent and authentic … and that is powerful in a time when people are cynical about politicians.”

Sanders gains strength – and mainstream Democrats worry

Marshall Matz knows what a losing campaign looks like.

An adviser to Sen. George McGovern’s 1972 White House bid, Mr. Matz had a front-row seat to one of the biggest losses in presidential history. Senator McGovern, a liberal who opposed the war in Vietnam, drew large and enthusiastic crowds on the campaign trail but went on to lose every state save Massachusetts and the District of Columbia to an unpopular incumbent.

Today, Mr. Matz finds himself watching the campaign of Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders with a growing sense of alarm that history may repeat itself.

“I do believe that Senator Sanders is too liberal to defeat an incumbent Republican president, especially an incumbent president with a good economy and a huge bankroll,” says Mr. Matz, a registered Democrat who still admires the late Senator McGovern and considered him a close friend.

“I’m trying to sound the alarm and say ‘heads up’ here,” he says.

With just 12 days until the Iowa caucuses and a dominant front-runner yet to emerge, what once struck many as an unlikely outcome – “Democratic nominee Bernie Sanders” – is suddenly looking like more of a possibility.

Even though a heart attack threatened to derail his campaign last fall, Senator Sanders raised $34.5 million over the final months of 2019, more than any of his rivals. One recent Iowa poll showed him in the lead there for the first time this cycle, and a new national CNN poll has him leading the pack. At the final debate in Des Moines last week, Mr. Sanders was given one of the center-stage spots reserved for front-runners.

He’s benefitted in part from the struggles of fellow progressive Sen. Elizabeth Warren, whose support appears to have fallen off in recent weeks – and with whom he had a public spat last week over whether or not he once told her he believed a woman could not win the White House.

Mr. Sanders’ strength is eliciting a kind of anxiety within certain quarters of the Democratic Party not unlike the reaction many Republicans had four years ago to another party outsider who few initially believed could win: Donald Trump. Like President Trump, Mr. Sanders’ unconventional style and promise to upend Washington has attracted a passionate group of followers who can’t be neatly categorized – and could wind up scrambling the usual “rules” of politics.

“The ironic similarity between Bernie and Trump is that they both have clear messages,” says Iowa-based Democratic strategist Jeff Link. “[Bernie] is incredibly clear and consistent and authentic … and that is powerful in a time when people are cynical about politicians.”

“Viable enough to win”

A lot can change in the weeks leading up to Iowa – and frequently does. Four years ago, Mr. Sanders closed a 12-point gap in the final three weeks before the Iowa caucuses. Today, polls show that 60% of the state’s caucusgoers are still undecided.

But if Mr. Sanders actually wins Iowa (which he very nearly did in 2016), and then goes on to win New Hampshire (as he did in 2016), it is not hard to envision his momentum carrying him on to win in Nevada and beyond. The latest poll out of California, which will vote on Super Tuesday, has Mr. Sanders in the lead there.

“The realization that his campaign is viable enough to win multiple early states, and with the funding there as well, has awoken many to the possibility that he could win the nomination,” says Scott Mulhauser, a longtime Democratic operative who was Vice President Joe Biden’s deputy chief of staff during the 2012 Obama-Biden reelection campaign. “There is a steadiness to his campaign that has endured despite seemingly everything.”

Lately, the drumbeat from establishment Democrats warning against a Sanders nomination has grown noticeably louder.

Hillary Clinton made headlines Tuesday for speaking out against her 2016 primary rival. “Nobody likes him, nobody wants to work with him, he got nothing done,” she says in a forthcoming documentary – an assessment she repeated in an interview in The Hollywood Reporter. When asked if she would support Mr. Sanders were he to win the nomination, she replied, “I’m not going to go there yet.” (She later clarified that she would “do whatever I can to support our nominee.”)

In some ways, that’s a fight many of Mr. Sanders’ supporters seem to relish. To beat Mr. Trump in November, they say, the Democratic nominee will need to excite new voters and get them to the polls – voters who, like many of Mr. Trump’s supporters, have been disappointed by the party and are unhappy with the status quo. Some hypothetical general election matchups do show Mr. Sanders, along with Mr. Biden, faring best against Mr. Trump. One poll published last week by Marquette University Law School found they were the only two to beat Mr. Trump in the crucial swing state of Wisconsin.

But while Mr. Sanders’ supporters see the passion he inspires as a strength, other Democrats see it as a threat. Many blame Mr. Sanders for Mrs. Clinton’s general election loss in 2016, and fear that if he fails to win the nomination again in 2020, his supporters will stay home on Nov. 3 instead of rallying around the party’s nominee.

“Sanders concerns Democrats by getting the nomination – and by not getting the nomination,” says Dennis Goldford, a political scientist at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa. “Democrats are scared down to their toes that Sanders could tank the whole ticket.”

A “solid ceiling” on Sanders’ support?

Of course, not everyone is convinced that Mr. Sanders has a real shot at clinching the nomination. Most Democratic voters simply would never vote for someone who calls himself a democratic socialist, says Professor Goldford.

“I think people forgot that he has a solid floor,” he says, in response to the recent flurry of Sanders-induced panic. “But, at least last time around, he seemed to have a solid ceiling. And he would be underestimated only if he breaks that solid ceiling this time around.”

Some activists on the ground in Iowa express skepticism about Mr. Sanders’ strength. In northern Iowa, a conservative region represented by far-right GOP Rep. Steve King in Congress, several local Democratic leaders say chatter about Mr. Sanders’ rise is overblown.

“I just don’t see it,” says Logan Welch, a member of the Hamilton County Democrats and local councilman for Webster City. “If you just went around Webster City and asked all the Democrats who they are going for, I don’t think Bernie would be in the top three.”

He sees more local support for former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Senator Warren, and Mr. Biden in Webster City, a town of less than 8,000 people an hour’s drive north of Des Moines. True, Mr. Sanders surprised everyone with his near-win against Mrs. Clinton in 2016, says Mr. Welch – but it would be shocking for him to rise to the top again this year with such a “thick bench” of Democratic candidates.

Julie Geopfert, chair of the neighboring Webster County Democrats, says Mr. Sanders’ supporters don’t seem as “fanatical” this time around. In fact, she says she has seen a lot of Sanders backers from 2016 switch over to other candidates this cycle.

How caucus system could benefit Sanders

But the bigger field could actually be helpful to Mr. Sanders. Like Mr. Trump, he may benefit from a large and fractured primary, in which those opposed to him wind up splitting their support among various other candidates, and the percentage any one candidate needs to win is lower.

In a January 2016 Des Moines Register poll, 43% of likely caucusgoers said they would describe themselves as “socialist,” which ended up being a good proxy for Mr. Sanders’ eventual support in the caucus that year. In this year’s poll, only 28% of likely caucusgoers described themselves that way. At first glance, that may seem like disappointing news for Mr. Sanders. But that also might be all he needs to win.

“The campaign has thought all along that if they can maintain their base and there is a credible challenger to Biden in the establishment lane, then they would be in good shape,” says Mr. Link.

The way the Iowa caucuses work could benefit Mr. Sanders even more. If candidates are deemed “nonviable” on caucus night (meaning they have the support of less than 15% of those in the room), then their supporters can “realign” with a different candidate.

Kelcey Brackett, chair of the Muscatine County Democrats, speculates that two candidates who may wind up as nonviable are Hawaii Rep. Tulsi Gabbard and entrepreneur Andrew Yang. And he expects a high percentage of their supporters – many of whom identify as independents – will join the Sanders camp.

Indeed, Mr. Brackett says Mr. Sanders is looking quite strong in the southeastern corner of the state, where he did particularly well in 2016. His campaign is large and active in Muscatine County, says Mr. Brackett, and seems to be knocking on more doors and making more calls than other campaigns.

“We’ve probably been underestimating [his support],” agrees Judy Downs, executive director of the Polk County Democrats, Iowa’s most populous county and home to the state capital of Des Moines. The Sanders campaign empowers volunteers by giving them a lot of autonomy, says Ms. Downs – but this also means it’s more difficult to fully estimate the strength of his campaign.

“I think Sanders will be very happy on Feb. 4,” she predicts.

Since publicly speaking out against Mr. Sanders earlier this month, Mr. Matz says several of his colleagues from the McGovern years have reached out to say they agree.

“We need to be more pragmatic than idealistic,” says Mr. Matz. “Who has the best chance of winning? I’m not sure who that is yet – but I’m pretty sure who it’s not.”

Why Egypt’s President Sisi is rushing to embrace country’s youth

The Middle East faces a crisis, and Egypt is no different – too many young people, too few jobs. So the country’s autocratic leader is trying to craft a new persona that’s engaged, fatherly, and a little bit hip.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Nine years ago disaffected young Egyptians launched a revolution that overthrew longtime President Hosni Mubarak. Like the current president, he was a career general who presented himself as a nationalist leader.

Today President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi is presiding over the fastest growing economy in the Middle East. Construction is everywhere and investor confidence is returning. But more than half of Egypt’s population of 100 million is under the age of 25. And even as GDP has risen, so too has poverty. Youth unemployment hovers above 30%.

Mindful of the past, a restless President Sisi is pushing programs to meet the new generation’s needs: housing, health care, youth forums, and jobs. He’s using these programs to project a fatherly persona, that of a concerned leader “providing for” young Egyptians. Hugging young people in front of cameras pushes the point home.

“I have one million youth trying to enter the labor market each year. They want a home, they want to marry, they want to raise children,” Mr. Sisi recently told a group of foreign reporters. “How many jobs would you need to create? Could you do that, every year, for one million people?”

Why Egypt’s President Sisi is rushing to embrace country’s youth

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi is presiding over the fastest-growing economy in the Middle East, tourism is booming, and a war against ISIS-styled militants appears over.

Construction is everywhere and investor confidence is returning. There is a palpable energy and confidence radiating from Cairo’s streets.

Then why is the Egyptian leader restless?

Two words: one million.

Over half of Egypt’s population of 100 million – some 52% – are under the age of 25, while two-thirds are under the age of 30 and are looking for jobs and homes at a time the Egyptian economy is still recovering.

“I have one million youth trying to enter the labor market each year. They want a home, they want to marry, they want to raise children,” President Sisi recently told a group of foreign reporters. “One. Million.”

“How much would that cost in highly developed countries? How many jobs would you need to create? Could you do that, every year, for one million people?”

Therein lies Egypt’s challenge.

It was nine years ago that disaffected young Egyptians launched a revolution that overthrew President Hosni Mubarak. Like President Sisi, he was a career general who presented himself as a nationalist leader.

With that recent past in mind, Mr. Sisi, whose tenure has been marked by the suppression of dissent, is rushing to offer a warm embrace to young Egyptians to head off any potential unrest, opposition, and instability.

Economic recovery

Last month capped a remarkable recovery for Egypt, which just three years ago faced 30% inflation, 20% unemployment, a debt crisis, and devastating terrorist attacks across the Sinai and even in Cairo itself.

Egypt’s gross domestic product grew by 5.8% in 2019, up from 3% when Mr. Sisi was sworn in as president in 2014. Inflation dipped down to 2.7% in November, the lowest since the 2011 revolution.

But these numbers do not tell the whole story.

While GDP has risen, so too has poverty, with poverty rates up 5% over the past three years, according to the government Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. Youth unemployment hovers above 30%.

“In Egypt, the population is still growing, the majority still have access to higher education, yet the economy is not growing at a pace fast enough to create jobs for young people,” says Amr Adly, political economist and assistant professor at the American University of Cairo.

“Creating youth employment is no easy task.”

The government is now rolling out a series of youth dialogues, forums, and technocratic socio-economic programs to address those challenges and telegraph its good intentions.

Youth conference

One symbol of President Sisi’s urgent youth embrace is the “World Youth Forum,” an annual gathering to discuss the challenges and concerns of young people in Egypt, the Arab world, Africa, and beyond that is the brainchild of the Egyptian president himself.

At the forum, held in the Red Sea resort town of Sharm El Sheikh, Mr. Sisi presides over panels and talks with young people flown in from across the world. Among the issues discussed: artificial intelligence, the fourth industrial revolution, cryptocurrency, and food security.

But more than just an emcee, Mr. Sisi is an active participant.

At the 2019 forum last month, the Egyptian president was sitting in the front row, furiously scribbling down notes on a pad of paper, and asking probing questions of speakers and the young audience.

He also never wasted an opportunity to tell Egyptian audiences of the stability he upholds.

On the sidelines, his ministers were buzzing about projects ranging from community biofuel plants to bike-sharing schemes for university students. Young Egyptian entrepreneurs and their businesses were showcased in booths.

“The government is encouraging and opening doors for young entrepreneurs,” says Khaled El-Sayed, founder of a startup highlighted at the Youth Forum. “It is a very different environment than a few years ago when we wouldn’t have even been noticed.”

Some of Mr. Sisi’s other youth programs are paternal, bordering on invasive.

One such program is Mawadda, or the “Affection” initiative, which promotes the importance of marriage among young Egyptians. To cut rising divorce rates, it aims to teach young people how to “pick the right partner.”

Another, the Presidential Leadership Program (PLP), directed by Mr. Sisi’s office, trains potential young leaders in social sciences and governance to prepare them for positions across government to be “the force for reform and change.”

In November, Mr. Sisi swore in 11 new governors who were PLP graduates, and the president says he expects to fill more government positions from these youths.

According to independent media reports, graduates of the program are now also filling posts in state-run and private media organizations, directing content at the behest of intelligence services.

Mega-project to youth projects

Initially there were different priorities for Mr. Sisi, who upon his rise to power in a 2013 military coup against Islamist President Mohammed Morsi was flush with $20 billion in funds from Saudi Arabia and the UAE, eager for an ally to crush Mr. Morsi’s Brotherhood movement.

Since his 2014 election, the Egyptian president embarked on a series of megaprojects – among them an $8 billion expansion of the Suez Canal and a new administrative capital built outside Cairo – to mixed results.

The fight against terrorism and a brutal crackdown on political opposition also consumed Cairo’s energies.

Yet as Gulf funding dried up and security was restored, Mr. Sisi and his government shifted to a series of targeted reforms, partnering in recent years with the private sector and the World Bank to fill gaps to provide housing, health care, and support for young entrepreneurs.

After a $40 billion housing project with the United Arab Emirates to build 1 million affordable homes broke down, Egypt pursued its own program with local banks and the World Bank, providing homes to 241,517 families.

It launched the Long Live Egypt Fund, a charitable fund to serve the poor and young Egyptians in health and housing, and wrote new regulations to support small to medium enterprises, which employ a bulk of Egypt’s citizens.

Last year, Cairo rolled out a new universal healthcare system that allows Egyptians to choose their health service providers, lowers their medical payments, and allows immediate care in private or public hospitals, a scheme praised even by government critics.

Father figure

Mr. Sisi has used these programs to project a fatherly persona, that of a concerned leader “providing for” young Egyptians to help ease painful economic reforms as his government grapples with decades of deep-seated economic issues.

Hugging young people in front of cameras pushes the point home.

The programs also have been instituted at a time the government has slashed energy subsidies, raised fuel prices, imposed taxes, and devalued the Egyptian pound to comply with a $12 billion International Monetary Fund loan.

This paternal approach also stems from Mr. Sisi’s belief that young Egyptians “want a home, job, and a family,” rather than freedoms and democracy.

The president frequently blames the “chaos” of the 2011 democratic revolution for derailing Egypt’s economy and allowing extremist groups to flourish.

After years of post-revolution uncertainty, his argument is persuasive to some Egyptians.

But many liberal and independent Egyptians chafing under speech restrictions, and those from marginalized regions who have borne the brunt of austerity measures, would disagree.

So too would the thousands of young people – some reportedly as young as 11 – who have been arrested for alleged political activity or anti-corruption protests and who continue to languish in jail.

Yet in conversations on the streets of Cairo and on the sidelines of the youth conference, a number of ordinary young Egyptians say unprompted that they feel Mr. Sisi has their interests at heart.

“There is an establishment in place that historically worked against the Egyptian people, but President Sisi is changing this,” says Mostapha Ali, a Cairo craftsman who initially qualified for an affordable housing program before a local bank declined to approve his participation.

“At the very least he is trying and working for our interests.”

Perhaps it was fitting, then, that Mr. Sisi used a hastily arranged local youth conference in September to respond to corruption allegations by a former government contractor that went viral and sparked a spattering of protests against his rule.

“I am establishing a new state. I am doing so in the name of Egypt. ... The whole world will see it,” Mr. Sisi said to an audience of young Egyptians on national television, defending the construction of lavish presidential palaces and listing his government’s achievements.

“Nothing is in my name,” Mr. Sisi insisted. “It is in Egypt’s name.”

Yesterday, he sang for guerrillas. Today, he answers to mayor.

In Colombia, an ex-combatant in the country’s decadeslong civil war has been elected to office. It shows a path to reconciliation – and the hard questions that come with it.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Megan Janetsky Contributor

Guillermo Torres walks the sweltering streets here like a celebrity. He’s been famous for decades, known as “the singer” of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC.

But last October he made headlines for something new: He was elected mayor of Turbaco, becoming one of the first ex-FARC combatants to win an election by popular vote.

Three years after a peace agreement, Colombia is still struggling to emerge from years of conflict. Mr. Torres is a symbol of the nation’s broader tensions as demobilized guerrillas seek to build a place for themselves in a society that still sees them as criminals let off easy. The peace accord made big promises, like reparations for victims and reduced sentences for ex-combatants who tell the truth.

As Mr. Torres takes office this month, his success could be a broader test for the nation. “I’m never going to leave the path of peace anymore,” he says. “I know the risks.”

Yesterday, he sang for guerrillas. Today, he answers to mayor.

Guillermo Torres walks the sweltering streets in this bustling northern Colombian town like a celebrity. Teenage boys ask for selfies, children hug him like family, and throngs of men and women earnestly shake his hand.

Mr. Torres has been famous for decades. Under the alias Julián Conrado and nickname “the singer of the FARC,” he was a key member of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia for 30 years. The guerrilla group is accused of crimes ranging from kidnapping to drug-trafficking, and until a 2016 peace accord was locked in a bloody civil war with the Colombian government for half a century.

But last October, Mr. Torres made headlines for something new. He was elected mayor of Turbaco, becoming one of the first ex-FARC combatants to win an election by popular vote.

As Colombia struggles to emerge from years of conflict, the vallenato singer is a symbol of these broader tensions as demobilized guerrillas seek to build a place for themselves in Colombian society. After decades of bloodshed, there are deep-seated stigmas surrounding ex-combatants like Mr. Torres. He faces accusations of violence from his involvement with the FARC – though he denies ever doing more than sing songs of peace for the rebel fighters.

As Mr. Torres assumes office this month, his political ascent poses a tough question for the country that’s ended war on paper but still struggles to feel at peace: Is it possible to move ahead when the decades of conflict are still unresolved?

The peace deal is meant to facilitate the reintegration of former combatants and pay reparations to nearly 8.8 million registered victims. It promises things like a special court for transitional justice, providing reduced sentences for ex-combatants who tell the truth about what happened during the conflict.

“I’m not a militant of the FARC anymore,” Mr. Torres says, sitting in a market in the heart of Turbaco on a late December morning. “I don’t want to be a militant of any party. I want to be a militant of my people.”

Lasting ‘stigma’ of the FARC

The 2016 peace agreement promised an end to 52 years of violence between Colombia’s government and guerrillas hiding away in the rural reaches of its jungles. Combatants set down their arms and a newly formed FARC political party was given seats in Congress. But an inherent distrust of the combatants still simmers.

When the FARC emerged in the 1960s, they referred to themselves as the “People’s Army,” set on countering violent military crackdowns. But the insurgents turned into something more destructive, relying on forced recruitment, extortion, and Colombia’s lucrative drug trade to fuel their war against the government.

“The FARC committed egregious crimes against humanity,” says Sergio Guzmán, director of Colombia Risk Analysis. “They raped, they killed, they kidnapped. ... It’s not like they have a bad reputation undeservedly.”

In 2018, President Iván Duque took office after campaigning heavily against the peace agreement, saying it created an environment of impunity. The conservative politician denounced “inhumane criminals who have killed, kidnapped, extorted, and recruited children, arriving to Congress.”

Under Mr. Duque, faith in the peace process has faltered, as the government fails to implement key facets of the agreement. Paramilitary-fueled violence in former FARC zones surged in the power vacuum left behind. Ex-combatants have been targeted and assassinated by other armed groups, and key FARC leaders made renewed calls to arms against the government. Mr. Torres received death threats during his campaign, and now walks around town with a bodyguard.

“The stigma of being an active part of the conflict is going to remain with them forever,” Mr. Guzmán says about former FARC members.

‘Armed with a guitar’

Mr. Torres was born in 1954 in the impoverished town of Turbaco, which sits just a stone’s throw away from the tourism hotspot of Cartagena. He claims he began singing in the womb.

As a young man, his ballads turned political as he noticed the corruption permeating coastal governments like Turbaco’s. He became what he called “the people’s singer,” crooning about injustices facing his town in coastal rhythms of vallenato.

“I sing because the people need their singers,” he says. “It’s how the people express their joy. It’s how the people express their sadness. It’s how the people express their desires, their will, their dreams.”

Singing about injustice was a dangerous proposition at a time when anyone speaking out against the government was lumped in with leftist guerrillas. Mr. Torres started to see a violent backlash against his political activism in the early 1980s. When paramilitaries killed his friend Julián Conrado, a doctor and fellow singer, 29-year-old Mr. Torres fled to the jungle-cloaked Sierra Nevada mountains and joined the FARC.

“Many Colombians didn’t have any other options to save our own lives,” Mr. Torres says, noting that many joined the FARC or the military simply to not be caught in the crossfire. “It was a decision I made forced by circumstance.”

He gave himself the alias Julián Conrado to honor his friend. When he joined, Mr. Torres hoped to someday leave the fighters and return home.

In the FARC, Torres became a troubadour for the guerrillas. “I am a guerrilla, but you know what has been my weapon for all my life? My singing,” Torres says. “I was always armed with a guitar.”

Escaping his past?

Some observers say he was armed with more lethal weapons. While Mr. Torres’ electoral victory was historic, his past is front and center for many critics as he assumes office.

Before Mr. Torres demobilized in 2016, the singer was wanted by the United States Drug Enforcement Agency for alleged crimes including drug trafficking and conspiracy. There were numerous warrants out for his arrest in Colombia, including for homicide and kidnapping. While he was actively a part of the FARC, the U.S. government offered up to $2.5 million as a reward for information leading to his arrest.

Former Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos dubbed Mr. Torres a “narco-terrorist” in 2011 when he was captured and imprisoned for three years in Venezuela. He was released to join peace negotiations with the Colombian government in Havana.

Mr. Torres denies all allegations against him, saying he was associated with the actions of FARC leaders because he played music at key events.

“I’m not a man of war, I’ve never been a man of war,” Mr. Torres says. “I spent a lot of my childhood under the bed because I was scared of fireworks.”

The now-65-year-old mayor says he tried to demobilize with other guerrillas after a few years in the FARC, forming the leftist political party Patriotic Union. But when party members became targeted by paramilitaries, drug lords, and security forces, Mr. Torres says he returned once again to the jungles.

‘Tired of war’ – and the FARC

Colombia’s October 2019 local elections were the first in which the FARC political party participated in a popular vote. It served as a referendum on the guerrillas’ popularity and ability to integrate into a society that still fears what the fighters once represented, says Gimena Sánchez-Garzoli, Andes director of the Washington Office on Latin America.

Mr. Torres says that in an attempt to leave the stigma of the FARC behind, he ran for office under the leftist party Colombia Humana – not the rose banner of the FARC party.

His anti-corruption message won 50.7% of the vote, nearly 20% more than his closest competitor.

While the FARC party ran more than 300 candidates for thousands of open mayoral and council seats, only two were elected. Two other ex-combatants also won mayoral seats under the helm of other parties.

The elections offered the party an opportunity to show they had been redeemed in the eyes of the public, Ms. Sánchez-Garzoli says. But in practice, the results were the opposite.

It shows “that Colombian society was tired of war, but they were also tired of the FARC,” Ms. Sánchez-Garzoli says. Though a relative outlier, Mr. Torres’ coastal town may offer an alternative path forward.

“People need second chances,” says Luis Montalbon, a moto-taxi driver here. “He’s done bad, but now the people are choosing him because he is leading against the bad things that have been happening in this town.”

Mr. Montalbon, a father of two in his late 30s, lived nearly his entire life with the FARC and Colombian government at war. Leaning on his motorcycle – the scorching coastal sun beating down on his sweat-speckled face – he talks about the rampant corruption and soaring levels of poverty and unemployment he believes is holding Colombia back.

“In Turbaco there isn’t anything,” he says. Mr. Torres’ promises for change presented a sliver of hope, he explains, though people still whisper about the mayor’s past.

Despite the outpouring of support in his hometown, Torres may have a “rude awakening” as he faces the rest of the country as a public official, Mr. Guzmán says. Mr. Torres still must present himself before the country’s transitional justice court, Special Jurisdiction for Peace, after being listed among 31 FARC leaders allegedly involved in FARC kidnapping policies.

And any ex-FARC member holding office will have to collaborate with a national government that repeatedly rails against the peace process for being too lenient.

Mr. Torres, however, isn’t too concerned about his political longevity.

“If I have to pay whatever price for the peace of my country, I’m ready to pay that,” he says. “But I’m never going to leave the path of peace anymore. I know the risks that I run.”

This African group’s music champions rights – and love

Music can be more than a form of entertainment. For the group Les Amazones d’Afrique, a collective of women musicians from Africa, it’s a tool to empower women and speak out against violence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

As in many parts of the world, in Africa, violence against women is widespread. That’s why, in 2014, Valerie Malot, head of a booking firm, encouraged several star singers to take a united stand against such violence on the continent and beyond. And that’s how the African female collective Les Amazones d’Afrique was born. Its founding principle: to be a vessel to empower women against spousal abuse, second-class status, and female genital mutilation.

Released in 2017, “Republique Amazone,” the group’s first album which focused on violence against women, garnered plaudits from NPR, Rolling Stone, and Barack Obama.

On Jan. 24, the world will have the opportunity to hear “Amazones Power,” the second album by the multilingual group whose lyrics focus on women’s rights. Its fluid, evolving lineup includes lead singers from Mali, Algeria, Benin, and Burkina Faso.

“This album is really about empowerment, sisterhood, and love,” says Tiguidanké Diallo, who records under the name Niariu. “Without women holding this world together, we wouldn’t be at peace. Women are the glue that sticks people together as a society.”

This African group’s music champions rights – and love

Tiguidanké Diallo still hasn’t played her new songs to the person who most influenced the feminist outlook of the lyrics: her mother.

Ms. Diallo, who records under the name Niariu, recently joined the African female collective Les Amazones d’Afrique. Her sassy staccato propels “Heavy,” the first single from the group’s new record, “Amazones Power.” She’s also the sole figure on the album cover. Sporting the golden arm cuffs and headdress of an Amazon warrior, she stares at the camera with a formidable gaze.

“My mom is kind of my strength,” says Niariu during a phone call from Paris. “My determination, I get it from her.”

Niariu is “really shy” about unveiling the finished project to her mother. But on Jan. 24, the world will have the opportunity to hear the second album by the multilingual group whose lyrics focus on women’s rights. Its fluid, evolving lineup includes lead singers from Mali, Algeria, Benin, and Burkina Faso. The glue of the project isn’t just producer Liam Farrell, aka Doctor L. It’s the founding principle of Les Amazones d’Afrique to be a vessel to empower women against spousal abuse, second-class status, and female genital mutilation.

“The first album was to talk [about] and fight against the violence against women,” says Niariu. “This album is really about empowerment, sisterhood, and love.”

The genesis of Les Amazones d’Afrique dates back to 2014. Valérie Malot, head of the booking, publishing, and management firm 3dFamily, encouraged several star singers to take a united stand against violence against women in Africa and beyond. The consequent 2017 album, “République Amazone,” featured notable Malian artists such as Oumou Sangaré, Mamani Keïta, Angeìlique Kidjo, and Mariam Doumbia. It garnered plaudits from NPR (“There’s no mistaking the talent and vision these spectacular vocalists share”) and Rolling Stone (“[a] hard-funking, future-minded collaboration”). Barack Obama named “La Dame et Ses Valises” (“The Woman and Her Suitcases”) one of his favorite songs of 2017.

Les Amazones d’Afrique’s dub-influenced electronica, twined with Afrobeat rhythm and West African guitar, is currently anchored by Fafa Ruffino, Kandy Guira, Rokia Koné, Niariu, and Ms. Keïta. Niariu had been performing in an underground Parisian group when she was invited to come to the studio to write and sing.

“[On] the second album, the emphasis was more in talking about the violence on the women, but that can also be perpetrated by women,” says Niariu, noting that female circumcision is often performed by women. “So it was also a way of, first of all, uplifting women again, but also make us realize the strength that we have and how we can change things together.”

This time out, several songs pair male and female vocalists. Their inclusion isn’t just artistic; it’s also symbolic. Men have their part to play in feminism, says Niariu.

“Femininity is in everyone – male and female,” she says, praising Jon Grace and Boy-Fall from the group Nyoko Bokbae for their emotional sensitivity on their shared song. “That doesn’t mean that I’m not masculine enough. That means today I embrace my feminine side. And that’s something that I think males have to understand, society has to understand, because there’s a lot of pressure of what we call masculinity.”

The singer also sees a role for women to embrace masculine qualities, such as strength. “Heavy” is a tribute to female entrepreneurs such as Boy-Fall’s Senegalese grandmother, an immigrant who launched a successful hair salon in Paris. Niariu cites single mothers as another example of women who embody both masculinity and femininity. Her own mother is among them.

“When she was young, she was that cool kid, a rebel,” Niariu says, shaving her head, piercing her nose, and wearing leather. “And then she got married and then her life changed and she didn’t have the tools to be able to follow her dreams.”

The singer demurs on providing details of her mother’s marital experience as an immigrant from Guinea. There were “a lot of really desperate moments,” she allows. The aunts who helped raise Niariu inspired the song “Smile.”

“This message is a way to speak for my mom, who needed and still needs this sisterhood,” she says. “It’s a message ... to everyone that had the same story or is going through the same things and also trying to break this cycle.”

The final track on the album, “Power,” gathers 16 vocalists to reiterate a similar message. It’s a universal rallying cry for ending violence against women and ushering in equality and respect.

“Without women holding this world together, we wouldn’t be at peace,” she says. “Women are the glue that sticks people together as a society.”

Niariu says she’s going to sit her mother down to listen to the album soon.

“I know she’s going to tell the whole world about it,” she says, laughing.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why 2020 may be a year of giving

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Politics in the U.S. has become so intense that spending on political ads for the 2020 elections could reach $20 billion. At the same time, private giving to nonprofit groups may also see a banner year. In 2019, charitable giving reached an estimated $430 billion, up slightly from the year before. In both types of giving, whether for advocacy on a national issue or for action to solve a local problem, the motive is often a strong belief in how to shape society.

The big picture is one of greater civic engagement, at least measured by donations. Giving to a cause can transform both the donor and the recipient. It incites others to give. It helps people align their values for common purpose. For many, giving is merely a reflection of the good given to them.

Unlike the money itself, the effects can be immeasurable.

Why 2020 may be a year of giving

Politics in the U.S. has become so intense that spending on political ads for the 2020 elections could reach $20 billion. That would be a big jump from $16 billion four years ago. More people are willing to give more money for public causes.

At the same time, private giving to nonprofit groups may also see a banner year. In 2019, charitable giving reached an estimated $430 billion, up slightly from the year before despite a 2017 tax law that reduces taxpayer incentives to itemize donations. And during the November event known as Giving Tuesday, charities raised $511 million globally compared with $380 million in 2018.

In both types of giving, whether for advocacy on a national issue or for action to solve a local problem, the motive is often a strong belief in how to shape society. Political donors, of course, may be trying to rig public policy for their personal benefit. But the line between selfless and selfish giving is often blurred. The larger picture is one of greater civic engagement, at least measured by donations.

Groups that rely on private giving are concerned that Americans have a limit on their generosity. They warn of a competition for dollars between charities and politicians. Or they worry about the rising cost to run an ad asking for money. Yet the limitation is not in the amount of “discretionary” money in people’s bank accounts. It is in the vision of those asking for the money. A worthy cause can alter a person’s spending priorities.

Giving to a cause can transform both the donor and the recipient. It incites others to give. It helps people align their values for common purpose. For many, giving is merely a reflection of the good given to them.

The meaning of giving has also expanded to include ethical investing or investing in for-profit businesses with social goals, such as selling goods made of recycled material. As trust in traditional institutions declines, young people are inventing new ways to help others. They seek giving that is egalitarian and results-guaranteed.

The biggest result of giving is a more compassionate society. Giving helps build community, whether it is a donation to a political campaign or a homeless shelter. Unlike the money itself, the effects can be immeasurable.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Leave the ruminating to the cows

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Kim Hedge

Thoughtful consideration is a good thing. But when we’re stuck in a cycle of rumination that hampers progress, where can we find peace and answers? We can listen for divine guidance, letting the all-knowing God bring the calm and inspiration we need.

Leave the ruminating to the cows

Do you ever get stuck mulling over an idea, imagining all the different ways it could play out, or replaying a conversation and thinking of all the ways you could have responded better? Or when you think about a person (or even yourself), do you sometimes get stuck dwelling on something they did wrong, rather than the 95% of things they do right?

Sometimes when I find myself doing this, it almost feels as if I’m not in control of my own thinking. I get so focused on that one thing that I become almost mesmerized by it. I just keep turning it over and over, ruminating on it.

“Rumination” is a term used to describe the eating process of cows and other ruminant animals, including sheep, goats, deer, elk, buffalo, giraffes, and camels. These animals have four stomach compartments and can store food so they can come back to it later to chew on it again, which is called chewing the cud.

This is what we do, figuratively speaking, with thoughts or ideas when we ruminate on them. They come back to us over and over to keep chewing on, or wrestling with. Constructive thoughtfulness is a good thing, of course. But when it becomes something more extreme, how do we stop unhelpful cycles of rumination?

I have found a couple of ideas helpful in these situations. One has to do with a particular way to think about God. “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, provides several synonyms for Deity that find their basis in the Bible. One of them is Mind – divine Mind. Both the Old and New Testaments share accounts of God as all-knowing, wise, possessing infinite understanding, and having good counsel and righteous judgment or discernment. (See, for instance, Isaiah 40:13, 14; Psalms 147:4, 5; and Romans 11:33, 34.)

The idea that God is infinite, all-knowing Mind, possessing wisdom and knowledge of all that is good and true, and governing all by His wisdom and goodness, has direct relevance for us. The first chapter of the Bible explains that we are created in God’s image and likeness. As God’s spiritual reflection, we express that infinite Mind. This means that understanding is a quality inherent in the true, spiritual nature of each of us. So when we’re looking for answers, we can listen for divine guidance and let the all-knowing Mind calm our thought.

It can seem hard to listen when our mind is spinning in circles of rumination. But I like the example of Jesus responding to the fears of his disciples when he was out on a boat with them in a raging storm (see Matthew 8:23-27). From the vantage point of his spiritual understanding of God, Mind, the Bible says Jesus “rebuked the winds and the sea” with an authority that stilled the wind and waves and calmed the thoughts of his disciples.

This profound example of expressing divine authority reminds me that storms of thought within us can be stilled. God governs His creation with love and only ever wants peace for us, as this Bible passage conveys: “For I know the thoughts that I think toward you, says the Lord, thoughts of peace and not of evil [or fear, doubt, or rumination], to give you a future and a hope” (Jeremiah 29:11, New King James Version). As the expression of God’s love and goodness, we can and do experience and express that divine peace.

Psalm 46 counsels, “Be still, and know that I am God” (verse 10). Even when mental tumult seems overwhelming, we can take a moment to turn wholeheartedly to God to still our thought. The infinite, divine Mind is always peaceful and has just the inspiration we need at every moment. I’ve found that a willingness to let the divine Mind guide us tends to break the cycle of rumination, leaving me free to think clearly and to be receptive to new ideas and a fresh perspective. And we can trust that God’s answers – which come with clarity and calm – will benefit us and those involved in whatever the situation may be.

So, next time you’re caught up in mulling over some thought again and again, remember: We can leave the ruminating to the cows, and let God help us feel the clarity and true peace of Mind.

A message of love

Welcoming the Year of the Rat

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. We hope you’ll come back tomorrow when our Martin Kuz offers the latest in his updates from Australia – how the wildfires are testing a point of national pride.