- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A new start for Sinn Fein in Ireland?

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today’s stories examine the Trump administration and rule of law, the need for patience in the Democratic presidential race, how the quest for Mideast peace is changing, the surprising mysteries of our own sun, and 10 great books for February.

Ireland has done what was once unthinkable. The results from Saturday’s election put Sinn Fein – the party historically tied to the insurgency of the Irish Republican Army – on equal footing with the country’s two established, centrist parties.

The vote holds no hint of fondness for past violence. Older voters who remember "The Troubles" best largely stayed away from Sinn Fein. But to younger voters, feeling left behind by an economy that increasingly seems to benefit only elites, Sinn Fein was the one party that, ironically, represented a fresh start.

Jason Walsh, who grew up in Belfast and has written about Ireland for the Monitor since 2009, has been tweeting about all this for weeks now. Yet even he was surprised by how well Sinn Fein did. He told me that he still looks a bit askance at Sinn Fein. But he also said the growing economic inequities in Ireland are so pronounced that “it’s remarkable it’s taken so long for an alternative to appear.” A one-bedroom apartment in Dublin can run 2,000 euros a month.

Ahead is a delicate balancing act. Can Sinn Fein really change itself, parting with the last vestiges of links to a militant past? And can it change the country, expanding beyond a dependence on foreign investment to better develop Ireland’s own domestic potential?

“It is an extraordinarily thin line Sinn Fein is walking,” Jason says. But for the first time, Irish voters have given the party the chance to make that change.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

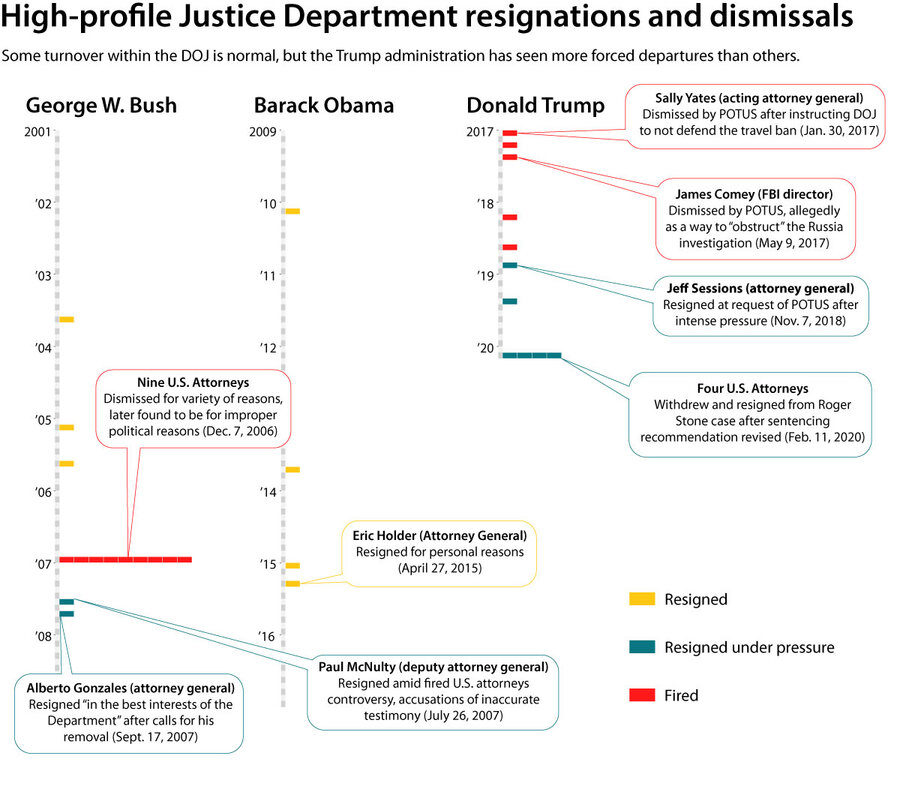

What does justice look like for president’s friends and foes?

At what point does the demand for loyalty undermine the rule of law? Several decisions by the Department of Justice this week have brought a new urgency to that question.

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

The Justice Department is ostensibly an independent agency within the executive branch. But it has increasingly launched probes into the president’s opponents and softened penalties for his allies since Attorney General William Barr became its leader last year.

Those moves stand in opposition to the core principle of equal protection under the law, critics say, and threaten the integrity of America’s judiciary.

On Tuesday, the U.S. Department of Justice reduced its sentencing recommendation for Roger Stone, after President Donald Trump tweeted his dismay at the previous recommendation federal prosecutors had made for his longtime confidant. By the end of the day all four career DOJ prosecutors had withdrawn from the case, and one resigned entirely.

“The minute the public begins to suspect that whether you are prosecuted or what your penalties end up being are affected by whether you are friends or enemies of the president,” says law professor Frank Bowman, “then a critical pillar of the American judicial system starts to crumble.”

What does justice look like for president’s friends and foes?

The events of this week are raising pointed questions about the rule of law and the political independence of America’s largest law enforcement agency.

On Tuesday, in an extraordinary move, the U.S. Department of Justice reduced its sentencing recommendation for Roger Stone, a conservative political consultant, after President Donald Trump tweeted his dismay at the previous recommendation federal prosecutors had made for his longtime confidant. By the end of the day all four career DOJ prosecutors had withdrawn from the case, and one resigned entirely.

The Justice Department is ostensibly an independent agency within the executive branch. But it has increasingly launched probes into the president’s opponents and softened penalties for his allies since Attorney General William Barr became its leader last year.

Those moves stand in opposition to the core principle of equal protection under the law, critics say, and threaten the integrity of America’s judiciary.

The Justice Department “tends to be pretty aggressive [with white collar sentencing], and to have a sudden outbreak of moderation in the case of a guy who happens to be a crony of the president raises questions,” says Frank Bowman, a professor at the University of Missouri School of Law.

“The minute the public begins to suspect that whether you are prosecuted or what your penalties end up being are affected by whether you are friends or enemies of the president,” he adds, “then a critical pillar of the American judicial system starts to crumble.”

“Principles of punishment”

Mr. Stone was convicted by jury of obstructing Congress and witness tampering in November, in a case related to the special counsel investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election. It was the final prosecution in Robert Mueller’s special counsel investigation – an inquiry that Mr. Trump regularly criticized, which resulted in seven guilty pleas and two convictions.

His back tattoo of a smiling Richard Nixon encapsulates both Mr. Stone’s political ideology and the approach he took for decades as a conservative political consultant. He has known Mr. Trump since the 1980s, and like other allies who have run afoul of the law, the president rallied to his defense.

This is a horrible and very unfair situation. The real crimes were on the other side, as nothing happens to them. Cannot allow this miscarriage of justice! https://t.co/rHPfYX6Vbv

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 11, 2020

Prosecutors had recommended a tougher-than-normal sentence of seven to nine years in prison, which they wrote in a court filing would “accurately reflect the seriousness of his crimes and promote respect for the rule of law.”

A sentencing recommendation is usually not a straightforward process. Prosecutors also take into account the offender’s criminal history, age, and whether they chose to take the case to trial – something that typically results in harsher sentences if convicted.

“I have never seen a prosecutor go in and undermine a jury’s verdict,” says Laura Brevetti, a former Organized Crime Strike Force prosecutor with the DOJ.

For offenses like Mr. Stone’s, federal guidelines typically call for a sentence ranging from 15 to 21 months, though they can request more if the offender engages in additional questionable conduct.

Before his trial, Mr. Stone posted on Instagram a photo of U.S. District Judge Amy Berman Jackson, the trial judge, with crosshairs next to her head. During the trial, prosecutors wrote, he also appealed for a presidential pardon through the right-wing media.

A senior DOJ official told media on Tuesday that the line prosecutor’s recommendation was “extreme and excessive and disproportionate to Stone’s offenses.”

But “the underlying principles of punishment are you want to deter people,” says Kami Chavis, a professor at Wake Forest University School of Law and a former U.S. attorney. “We do want to deter people from lying to members of Congress.”

The fact that the four prosecutors involved have since left the case, she adds, suggests they were “uncomfortable with this high level of intervention that seems politically influenced.”

Sword and shield

Potential for abuse is rife in both a president’s pardon power and their command of the executive branch. The fact that the Justice Department is part of the executive branch means there are two perpetual concerns, says Professor Bowman, author of “High Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

One concern is that a president will use the DOJ “as a shield to himself and his friends.” The other is that they will use the DOJ “as a sword against his enemies.”

“This president has indicated a disposition to do both,” he adds. The Stone case “is not out of the blue. This is not some one-off event.”

- Two weeks ago federal prosecutors backed off a recommendation of up to six months in prison for Michael Flynn, Mr. Trump’s former national security adviser, who he has praised as “a wonderful person” and “a very good man.” Prosecutors now support probation for General Flynn, who pleaded guilty to lying to investigators in the Russia inquiry.

- The first pardon he granted was to Joe Arpaio, an early campaign supporter. The former sheriff of Arizona’s Maricopa County was convicted of contempt of court for disobeying a federal judge’s order to stop racially profiling Latinos.

- Prosecutors oppose requests for early release for Michael Cohen, the president’s longtime personal attorney who cooperated with the Mueller investigation before pleading guilty to tax fraud and lying charges.

- Days after being acquitted by the U.S. Senate, Mr. Trump fired two key witnesses against him during the House impeachment inquiry: Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, an Iraq War veteran on the National Security Council staff, and Gordon Sondland, the former U.S. ambassador to the European Union. Mr. Vindman’s twin brother, who also was assigned to the NSC, was also removed.

- Jessie Liu, a federal prosecutor who led the Stone case, had her nomination for a post at the Treasury Department abruptly pulled this week by the White House.

“We all know what [Trump] is about and we all know what he is doing,” says Ms. Brevetti. The Stone sentence “brings up the issue of whether or not, at the highest levels of the Justice Department, is integrity no longer the coin of the realm?”

Barr’s Justice Department

When former Attorney General Jeff Sessions recused himself from any investigation into the 2016 election, in which he’d campaigned for Mr. Trump, the president lambasted him for it. After months of public criticism on Twitter, Mr. Sessions resigned in November 2018.

His replacement, Mr. Barr, has appeared more responsive to the president’s interests.

Mr. Barr returned to the DOJ with a track record of supporting broad presidential power and immunity from investigation.

Since taking office he has opened a review of the Mueller investigation and fired FBI Director James Comey’s actions. He has also opened an “intake process” to vet material that Rudy Giuliani, Mr. Trump’s personal lawyer, has gathered in Ukraine on former Vice President Joe Biden, who is seeking the Democratic nomination. On Wednesday the president congratulated Mr. Barr “for taking charge of a case that was totally out of control.” Also on Wednesday, Mr. Barr agreed to testify before the House Judiciary Committee, ending a year-long standoff.

Congratulations to Attorney General Bill Barr for taking charge of a case that was totally out of control and perhaps should not have even been brought. Evidence now clearly shows that the Mueller Scam was improperly brought & tainted. Even Bob Mueller lied to Congress!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 12, 2020

Ultimately, Judge Jackson will still make the decision as to how Mr. Stone is punished.

But these events have significantly damaged the Justice Department’s credibility, says Rebecca Roiphe, a professor at New York Law School and an expert on judicial ethics.

The president and Mr. Barr “are convinced that we have a deep state, including our Department of Justice,” she adds, refuting the idea that the DOJ is full of progressives who are trying to undermine the White House. “Those aren’t the kinds of people who go into law enforcement. People who choose to be federal prosecutors are not left-wing crazies.”

“It’s not the end of the world, but I do think that the credibility of the Department of Justice as a nonpolitical body that enforces the law equally against all is in jeopardy,” she continues. “This is not damage that can easily be constrained to Trump. Once this line is crossed, it’s really hard to go back.”

After New Hampshire, minority voters could reshape Democratic race

The media often want to anoint a presidential candidate as soon as possible. But after Iowa and New Hampshire, we just might have to be patient and let things play out.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

It may have gone more smoothly than Iowa. But Tuesday’s New Hampshire primary did little to resolve the Democratic presidential nomination contest.

As expected, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont won New Hampshire, but many voters view him as too far left to win a general election. In fact, the combined vote tallies of Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, and Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota would have beaten Senator Sanders by double digits in New Hampshire.

As the struggling campaign of former Vice President Joe Biden is urgently emphasizing, 99.9% of African American Democratic primary voters and 99.8% of Latino Democratic primary voters have not yet weighed in. As the contest moves to Nevada and South Carolina, the very different electorates there could change the shape of the race. And former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who is also polling well with African Americans, will be a player in primary contests starting in early March.

“I don’t think African American voters in South Carolina or Super Tuesday [states] give two flying kites what the early contests’ outcomes are,” says Antjuan Seawright, a Democratic strategist in South Carolina.

After New Hampshire, minority voters could reshape Democratic race

It may have gone more smoothly than Iowa. But Tuesday’s New Hampshire primary did little to resolve the Democratic presidential nomination contest – and indeed, may have increased the likelihood of a long, protracted battle that could go all the way to the convention.

Winner Bernie Sanders and runner-up Pete Buttigieg – who narrowly leads the overall delegate count coming out of Iowa and New Hampshire – can both plausibly claim some form of “front-runner” status, though neither looks particularly formidable. Amy Klobuchar, who until recently was languishing in the single digits, is hoping to capitalize on an unexpectedly strong third-place finish. With Elizabeth Warren and Joe Biden placing a distant fourth and fifth, and amassing no delegates in New Hampshire, a feeling of doom surrounds their campaigns.

But as the Biden campaign is urgently emphasizing, 99.9% of African American Democratic primary voters and 99.8% of Latino Democratic primary voters have not yet weighed in. As the contest moves to Nevada and South Carolina, the very different electorates there could change the shape of the race substantially yet again – potentially giving new life to candidates like former Vice President Biden and Senator Warren, who have built diverse coalitions of support.

“I don’t think African American voters in South Carolina or Super Tuesday [states] give two flying kites what the early contests’ outcomes are,” says Antjuan Seawright, a Democratic strategist in South Carolina. “Candidates that are coming into South Carolina and Super Tuesday who do not have relationships or have not gained the trust of the political concrete of this party – black voters – they’re going to be drinking hot soda out of a cup. It’s not going to taste good.”

Indeed, Nevada and South Carolina could muddle the Democratic field even further, at a time when party elites are increasingly worried about the prospects of beating President Donald Trump in November. Some see a strong possibility of a contested Democratic convention in July, which could force the party to choose between a fired-up progressive wing and a larger pragmatic wing that retains deep-seated skepticism about the prospect of a ticket headed by Senator Sanders, a democratic socialist.

“If Sanders goes to the convention with a plurality of delegates but not a majority, would they deny him the nomination?” asks Dante Scala, a political scientist at the University of New Hampshire in Durham. “It would be a high-risk maneuver that would take some steel on the spines of party elites and superdelegates – we’ll see if they’re so super.”

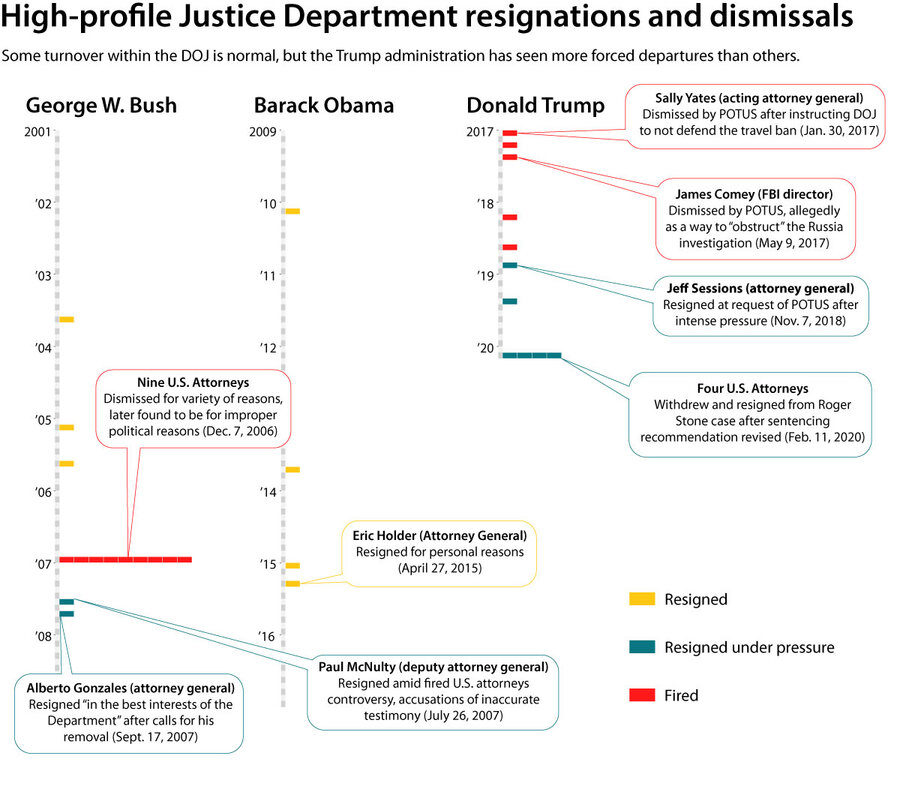

The beneficiary of all this may well be former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a billionaire whose unorthodox strategy of skipping the early states appears increasingly viable, and who is polling well among black voters nationally.

Sanders wins the primary, but ...

In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, a cold misty rain was falling as voters headed to the polls on Tuesday. Outside the New Franklin School in Ward 1, a young volunteer holding a big “Pete” sign and an older woman displaying “Amy Klobuchar for All of America” stood on opposite sides of the sidewalk, joking with each other and engaging in small talk. As a woman emerged from the polling site, she looked at both of them and pushed her hands together – as if to mime, “You should be on the same ticket.”

Indeed, the combined vote tallies of Mr. Buttigieg, the wünderkind former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, and Senator Klobuchar of Minnesota, ranked the most effective Democratic senator in Congress, would have beaten Senator Sanders by double digits in New Hampshire. Yet the first two primary states haven’t revealed much about what the Democratic electorate wants, says Theodore R. Johnson, a senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice in New York, and an expert on the role of race in electoral politics.

“We’ve only learned about what more progressive white primary voters in two states want,” he says. Still, a YouGov poll from late January found that black voters were nearly twice as likely as white voters to base their vote on candidates’ performance in the Iowa caucuses.

“If you’re a pragmatic voter, which I argue is the dominant tendency among black voters, then you are looking to see who wins primaries because they bring with them the air of electability,” says Dr. Johnson, who adds that black voters are getting “a little skittish” in their support for Mr. Biden.

But Mr. Seawright, who says that African American voters understand their political net worth and have always been independent-minded, says that South Carolina is still Mr. Biden’s to lose. He adds, “the second- and third-place contestants will have an opportunity to drive a specific narrative that could help them gain momentum as they prepare to face Michael Bloomberg and his resources on Super Tuesday.”

Mr. Buttigieg – a prolific fundraiser who has taken flak from other candidates for embracing wealthy donors – has gained momentum from his strong performances in the first two states.

But the true reach of his candidacy will be much clearer after Nevada and South Carolina. According to a Quinnipiac poll taken after the Iowa caucus, Mr. Buttigieg is polling at 4% with African Americans nationally. Senator Klobuchar is at 0%. Mr. Biden, by comparison, retained 27% support despite a disappointing showing in Iowa. Mr. Bloomberg registered at 22% and Sanders at 19% among black Americans.

And Tom Steyer, though not registering with black voters nationally, has gained double-digit support among African Americans in South Carolina, where he has been investing heavily.

In Nevada, which holds its caucuses a week from Saturday and where about 20% of eligible voters are Latino, FiveThirtyEight’s average of the most highly rated polls had Senator Sanders leading at 24.2%, followed by Mr. Biden in second with almost 19%, then Senator Warren and Mr. Buttigieg with 12% and 9% respectively. But just as South Carolina polls shifted after Iowa, the first two contests are likely to affect the polling in Nevada, as well.

To succeed in Nevada, the Buttigieg campaign says they are working to persuade the state’s Latino voters by translating campaign material into Spanish, opening a field office in the heavily Latino neighborhood of East Las Vegas, and launching radio ads with Mr. Buttigieg himself speaking in Spanish.

All of the presidential candidates are now white, after Andrew Yang and Deval Patrick dropped out of the race last night, despite an initial field that was far more racially diverse.

Possibility of a contested convention

Boosting black turnout, which dipped in 2016, is seen as crucial to a Democratic victory in November. The Center for American Progress found that a return to 2012 levels, in addition to natural demographic trends, would enable the party to win the three states vital to Mr. Trump’s victory: Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

But of course, race is only one factor in Democrats’ decision about which candidate will garner strong support. Ideally, they also want someone popular among progressives, urbanites, and working-class voters, as well as black Democrats – groups that sometimes overlap, and sometimes don’t. Finding one individual who can speak to those sometimes disparate interests may prove more difficult than Barack Obama made it appear.

The growing concern, therefore, is that by the time delegates descend on Milwaukee, Wisconsin, for the Democratic National Convention in July, no one candidate will have gained majority support. That could open the way for a brokered convention.

If no candidate got a majority of votes on the first round, a second round of voting with input from superdelegates could well produce a different candidate – angering many, says Don Fowler, a former DNC chair from South Carolina who has been involved in Democratic politics for more than 50 years.

“And that,” he says, “would create a great, great crisis to the party.”

Palestinians protest Trump plan at UN, but has world moved on?

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has long commanded a huge share of global attention. The somewhat muted reaction to President Trump’s peace plan suggests that might be changing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

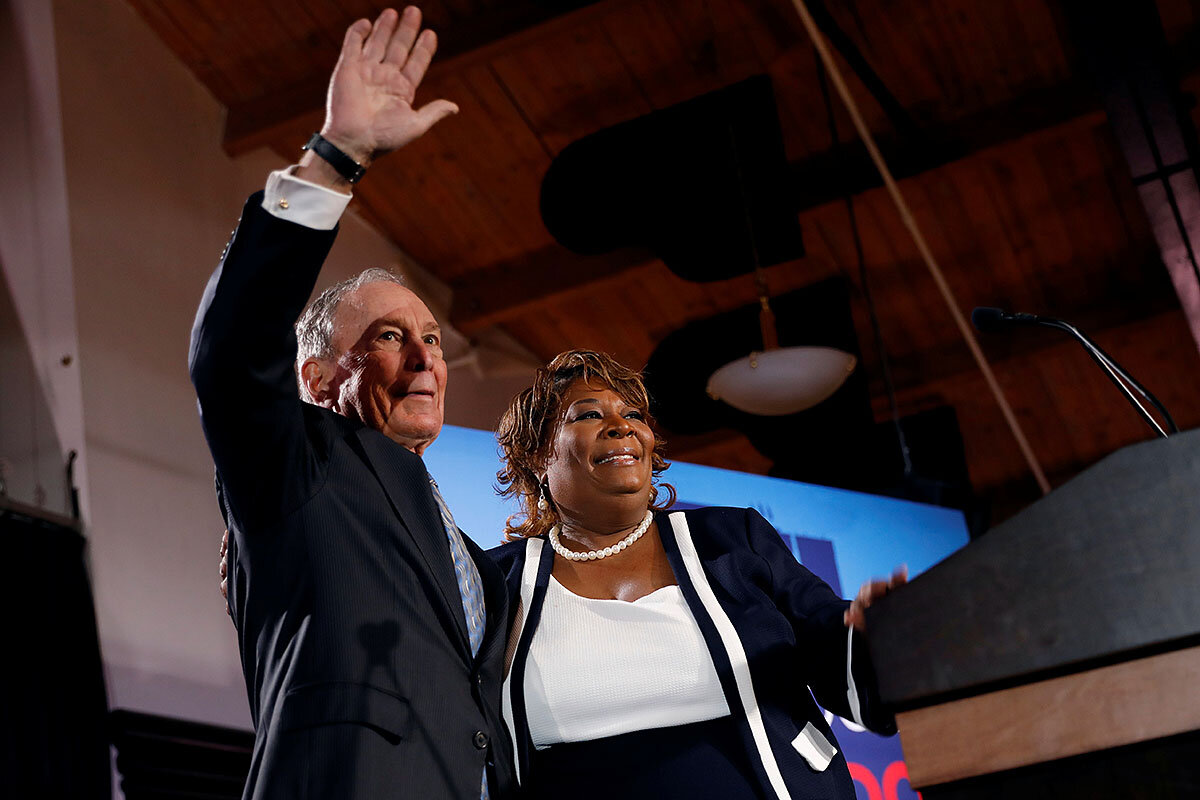

Most members of the United Nations Security Council say they remain committed to a negotiated settlement of the Israeli-Palestinian dispute that results in a viable Palestinian state with its capital in East Jerusalem. But if Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas once hoped for a resolution Tuesday critical of President Donald Trump’s Mideast peace plan, he was disappointed.

The near-uniform lining up of the international community behind U.S. efforts at Mideast peace may now be gone. But also gone is a fervent dedication to the Palestinian cause as a top international priority. At the same time, the weight and influence of the United States in the region and the world remain such that no peace initiative from an American president is going to be summarily dismissed.

“Clearly this is not a peace plan. Let’s not pretend that it is,” says Michael Oppenheimer, a professor of U.S. foreign policy and international relations at New York University. “It’s a reflection of facts on the ground, the kind of treaty you’d expect at the end of a war,” he says. “It’s sad for the Palestinians, but they just aren’t the do-or-die issue for countries that they once were.”

Palestinians protest Trump plan at UN, but has world moved on?

For decades, the international community has largely deferred to the United States’ lead in the effort to bring peace to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Think President Jimmy Carter’s Camp David Accords, the (President Bill) Clinton Parameters, and President George W. Bush’s Annapolis peace conference.

But now that President Donald Trump has unveiled his long-awaited “deal of the century” that aims to resolve the conflict once and for all, the global response looks different.

Gone is the broad acceptance of the U.S. lead, and the near-uniform lining up of the international community behind U.S. efforts at Mideast peace. But also gone is a fervent dedication to the Palestinian cause as a top international priority, particularly among Arab countries.

At the same time, the weight and influence of the U.S. in the region and the world remain such that no peace initiative from an American president is going to be summarily dismissed.

Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas learned this Tuesday at the United Nations in New York, where he had hoped to culminate an appearance before the Security Council – in which he blasted the Trump peace plan as one-sided and unfair – with a resolution demonstrating global rejection of the plan.

“This is an Israeli-American preemptive plan in order to put an end to the question of Palestine,” Mr. Abbas told the council.

The Trump plan “is like Swiss cheese, really,” the Palestinian leader added, holding aloft a map of the series of small islands within Israeli territory that would constitute a Palestinian entity under the American proposal. “Who among you will accept a similar state and conditions?”

And indeed, all of the council’s 15 members (five permanent members and 10 rotating seats) except for the U.S. expressed reservations about the Trump peace plan, with most members saying they remain committed to a negotiated settlement that results in a viable Palestinian state with its capital in East Jerusalem.

Still, things did not go as Mr. Abbas had hoped. Once it became clear that a resolution intended to underscore American isolation over the Trump peace plan was garnering only mixed support, the resolution was first watered down, and then delayed indefinitely as resolution sponsors Tunisia and Indonesia scrambled to try to secure support.

Already a hint at this lingering global reluctance to stand in opposition to an American Mideast initiative (and to risk drawing the ire of the peace plan’s namesake) had come last week. Tunisia’s well-respected U.N. ambassador, who helped fashion a resolution that was sharply critical of the U.S. peace plan but who also linked that criticism to the U.S. president, was abruptly sacked.

“Tunisia’s ambassador to the United Nations has been dismissed for purely professional reasons concerning his performance and lack of coordination with the ministry on important matters under discussion at the U.N.,” the Tunisian Foreign Ministry said in a statement.

But diplomatic sources at the U.N. said that in fact the ambassador, Moncef Baati, had been fired because the resolution he spearheaded had specifically criticized the Trump peace plan as being in violation of international law. Tunisia has a new president, Kais Saied, who did not want to start his tenure facing the wrath of the U.S. president, sources added.

Three years into the Trump presidency, a widespread international understanding of what getting on the U.S. president’s wrong side can mean played some role in the Security Council’s reluctance to go on record condemning the U.S. plan, some analysts say.

“Trump’s reputation as a counterpuncher really has deterred many actions that could provoke him to take negative or retaliatory steps,” says James Phillips, senior research fellow for Middle Eastern affairs at the Heritage Foundation in Washington. “I’d say the Tunisian decision [on its ambassador] probably reflected that.”

Still, Mr. Phillips and others say that what the lack of fiery support for Mr. Abbas reflects first and foremost is the waning of international interest in the Palestinian cause.

“It’s sad for the Palestinians, but they just aren’t the do-or-die issue for countries that they once were,” says Michael Oppenheimer, a professor of U.S. foreign policy and international relations at New York University’s Center for Global Affairs. “Clearly this issue has become kind of a nuisance for many countries, particularly the Gulf states that once stood solidly behind them,” he adds. “It’s no longer central to their diplomacy or to their pursuit of national interests.”

Other priorities, from tending to broad strategic relationships (with the U.S. and even Israel) to confronting an expansive Iran, have supplanted the Palestinian issue at the core of Arab and Gulf counties’ interests, Professor Oppenheimer says.

At the same time, Heritage’s Mr. Phillips says many countries look at other challenges in the region – the Syrian civil war, with its millions of refugees; the war in Yemen; upheaval in Libya; the destabilizing presence of the Islamic State – and the result has been a weakening fervor for the Palestinian cause.

“The impact of all these other conflicts is that the Palestinians’ plight is not perceived to be as bad as it used to be,” he says.

U.S. officials say privately that this week’s Security Council session on the Trump plan for resolving the conflict turned out better than they might have expected. They note, for example, that the council had voted overwhelmingly in favor of a resolution condemning the Trump administration’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in 2017 – forcing the U.S. to veto the measure.

By comparison, they take the failure of a resolution condemning the Trump plan as a victory and a sign of things going in the direction of the Trump “vision.”

Still, NYU’s Professor Oppenheimer says that does not mean the world likes what it sees in Mr. Trump’s “deal of the century.”

“Clearly this is not a peace plan. Let’s not pretend that it is. It’s a reflection of facts on the ground,” he adds, “the kind of treaty you’d expect at the end of a war with a clear winner and loser.”

Many countries in the region and in Europe may not like that reality, Professor Oppenheimer says, but they have “moved on” to other priorities and interests.

“Any opposition we hear now [such as that voiced at Tuesday’s Security Council session] is lip service,” he says. “But frankly, I think it’s been lip service all along.”

Why the sun’s mysteries could soon be revealed

You'd think the sun – so close, so important – would be an open book to scientists. Actually, no. But three new telescopes could start a golden age for understanding our closest star.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

For astronomers, the next decade could reveal a wealth of scientific understanding about our nearest star, thanks to a trio of new instruments.

Launched on Sunday, Solar Orbiter spacecraft – a collaboration between the European Space Agency and NASA – aims to study the sun’s mysterious magnetic poles, which appear to “flip” every 11 years. NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, which launched in 2018 and recently made its closest pass to the sun’s surface, seeks to explain the mysteries of the sun’s atmosphere. And the National Solar Observatory’s Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii, which released dazzling test images last month, brings its keen eye to the sun’s fainter parts.

The three observatories were designed and planned separately, and it was a coincidence that they’re set to operate around the same time. Scientists say that learning about our sun can yield information about other stars – and perhaps even life – outside our solar system.

“These three together, they basically will define the future of the field,” says Nour Raouafi, project scientist of NASA’s Parker Solar Probe mission. “The next decade, I believe, will be the golden age of solar and heliophysics research.”

Why the sun’s mysteries could soon be revealed

Our sun is such an enduring presence in our sky that it can feel like an old friend. But, with a blinding light that confounds traditional telescopes and scorches most space probes, much about it remains a mystery.

That could soon change, with a trio of new solar observatories poised to revolutionize our view of our solar companion, its relationship to our world, and perhaps even other star systems.

On Sunday evening, the newest solar observer rocketed into space by the light of a nearly full moon. The Solar Orbiter spacecraft – a collaboration between the European Space Agency and NASA – is designed to examine the sun from new angles, including taking the first ever look at its poles.

It joins NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, which launched in 2018 and has recently taken its deepest dive into the sun’s atmosphere to sample the solar wind directly. Also coming online later this year is a 4-meter ground-based observatory, the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST) in Hawaii, which will be able to study the fainter parts of the sun. Late last month, DKIST released its first test images of the sun’s surface, depicting turbulent cell-like structures the size of Texas and dazzling the public.

“These three together, they basically will define the future of the field,” says Nour Raouafi, project scientist of NASA’s Parker Solar Probe mission. “The next decade, I believe, will be the golden age of solar and heliophysics research.”

Unruly suns

The sun is continually producing “space weather” – coronal mass ejections, geomagnetic storms, and solar flares that can disrupt satellites and the power grid on Earth.

Researchers have long observed that these solar storms seem to wax and wane regularly, a phenomenon thought to be linked to the sun’s magnetic poles “flipping” every 11 years. But scientists haven’t been able to take a good look at the poles. All images of the sun have largely been from the same angle, roughly in line with the solar equator.

“It’s like trying to study a three-dimensional ball with only looking at part of it,” says Holly Gilbert, NASA deputy project scientist for Solar Orbiter and director of the Heliophysics Science Division at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. But Solar Orbiter’s path will take it over the sun’s top and bottom. “This allows us to look at the entire sun itself.”

We know from observing other stars that our sun is fairly tame – at least at the moment. Astronomers have spotted stars exploding violently, likely dousing planets in their orbit with radiation. Could our star be capable of that, too?

“We’re so desperate to know if other stars are like our sun, if our sun is normal, or what our sun might have looked like in its past or in its future,” says James Davenport, a stellar astronomer at the University of Washington.

If researchers can figure out what mechanisms drive the sun’s activity, it could help put it in a cosmological context among other stars. And that knowledge, in turn, could help scientists piece together a more precise picture of how solar systems form – as well as what might make a planet habitable.

“All of life on the Earth comes from the energy that the sun produces,” says Jeff Kuhn, an astronomer at the University of Hawaii and a co-investigator on the DKIST Science Working Group. “And without a complete understanding of how that energy fluctuates, we don’t really understand our future.”

Earth’s atmosphere allows just enough of the sun’s light through while keeping the most harmful rays out. But scientists say the solar wind, the stream of plasma rushing away from our star, can rip atmospheres from planets. Earth’s magnetic field deflects much of the solar wind, protecting our atmosphere, but the same might not be the case for similar planets orbiting other stars.

The new observatories are built to glean more information about the solar wind and the mechanisms that drive it. As such winds are difficult to study directly around other stars, scientists hope these missions will reveal indirect ways to infer the flow of stellar winds in other star systems. That knowledge, in turn, could help improve models to identify potentially habitable distant worlds.

“The sun is basically the star in our backyard,” says David Alexander, a solar physicist at Rice University. So it becomes a laboratory for astrophysics, he says. “We’re taking that knowledge of the sun and then applying it to other stars.”

A stellar lineup

Parker, Orbiter, and DKIST weren’t planned to be a team. All three observatories were designed separately, and it was a coincidence that they will all begin to operate around the same time.

But that’s a coincidence scientists are eager to harness. The three observatories will work together in many ways, using their unique sets of instruments and paths to study regions of the sun from different angles, both literally and figuratively.

“It’s a really good synergy with these different observatories,” Dr. Gilbert says. “Heliophysics is pretty difficult because it’s really a system science, and we have to understand how these different parts of the system are coupled,” from the solar atmosphere to the magnetic field, and how that interacts with the Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field.

Together, astrophysicists expect this trio to revolutionize our view of the sun, resolving long-standing questions about stars and planets, and revealing surprises about our constant companion.

“The sun is right there in front of us,” Dr. Kuhn says. It’s been “there in front of us forever, since civilization started. And yet now, only now in our lifetime are we looking at it and seeing as much detail that’s there.”

Books

10 books to brighten your February

Here we share with you our top literary picks for February, including the tale of a rogue naturalist and a biography of Emily Dickinson.

-

By Monitor reviewers

10 books to brighten your February

1. Apeirogon by Colum McCann

Colum McCann’s novel is a meditation on Israel – geographically, politically, and psychologically – as told through the story of an Israeli and a Palestinian. The two men each lost a daughter to the conflict; grief has sealed their friendship and hardened their conviction of the need to end the occupation.

2. Love, Unscripted by Owen Nicholls

A romantic comedy, this debut novel follows a film projectionist as he comes to terms with the fact that romance in real life bears little resemblance to what’s in the movies. Film references abound as he and his girlfriend struggle through disillusionment before arriving at a charming, happy ending.

3. Amnesty by Aravind Adiga

A Sri Lankan man living as an unauthorized immigrant in Australia discovers that he holds key information in a murder case. But if he goes to the authorities to reveal the killer, he will also reveal himself. Aravind Adiga unfolds a compelling story that pits self-interest against conscience.

4. The Authenticity Project by Clare Pooley

When Monica, a London cafe owner, discovers a notebook with an entry written by an eccentric artist seeking to be truthful, she sets off a chain reaction of transformation when she commits to helping him. More entries follow; strangers become friends and a community blossoms. Clare Pooley’s novel is fresh, funny, and inspirational.

5. Bird Summons by Leila Aboulela

Three Muslim women set off on a pilgrimage in Scotland in Leila Aboulela’s novel. Salma, who married a Scot, misses her Egyptian home and childhood sweetheart. Moni has subsumed her life to care for her ill son. Iman, who’s been dumped by her third husband, is homeless. Aboulela does a beautiful job examining faith and the interior life of women. There’s a thread of magic realism that unfortunately snags the plot as the book goes on, but it is impossible not to root for the trio to find their way.

6. The Adventurer’s Son by Roman Dial

Renowned biologist and explorer Roman Dial searches for his 27-year-old son, who has gone missing in the jungles of Costa Rica. Part memoir, part mystery, “The Adventurer’s Son” is a story of a father’s love – for his son and for the natural world.

7. 1774 by Mary Beth Norton

Cornell University history professor Mary Beth Norton has crafted a deeply researched and beautifully written account of the year in which the forces pushing the American colonies to rebellion finally came to the boiling point.

8. The Falcon Thief by Joshua Hammer

In the tradition of Susan Orlean’s “The Orchid Thief,” Joshua Hammer chronicles another naturalist gone rogue. “The Falcon Thief” tells of an enterprising rustler of falcon eggs, which are prized among those who want to hatch them as expensive pets. It’s a gripping read – a tale of obsession that promises to engross readers as they wonder, with each turn of the page, what will happen next. (Click here to read the full review.)

9. These Fevered Days by Martha Ackmann

This engaging biography of poet Emily Dickinson focuses on 10 pivotal episodes that shaped her life and poems. Martha Ackmann describes these with the flair of a novelist, drawing on research and insights she gleaned from teaching a Dickinson seminar at Mount Holyoke College. Ackmann challenges stereotypes about the poet and provides a rich sense of how “the woman in white” may have experienced her world.

10. The Splendid and the Vile by Erik Larson

Erik Larson, who’s been thrilling readers for decades as one of America’s best popular historians, turns his attention to Britain during World War II. In “The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz,” Larson expertly captures not only a nation’s despair but also the extraordinary human responses to the crisis, from courage and ingenuity to passion and grit.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Politics of hate loses a key vote in India

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

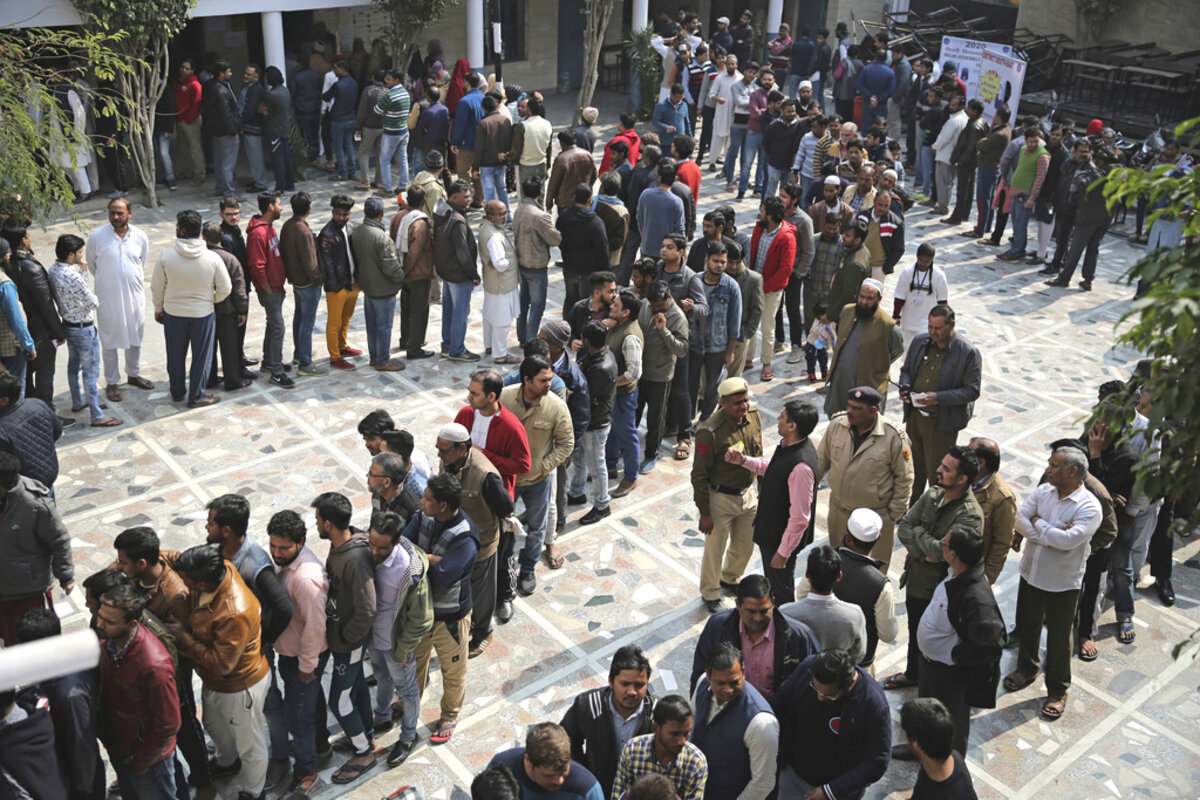

In December, India passed a new citizenship law for migrants that purposely excludes Muslims. It was the first time that religion has been used to grant nationality despite India’s secular constitution. For two months, both Muslims and non-Muslims have held sustained protests against the new law. Even more important, voters appear to be in revolt. On Feb. 8, India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party suffered a massive defeat in local elections in New Delhi, despite intense campaigning by the party’s leader, Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The BJP won only 8 of 70 seats in the city’s assembly while the other seats went to the local Aam Aadmi Party (Common Man’s Party, or AAP). One of the AAP’s top leaders, Sanjay Singh, said the election result is a mandate against hate.

The resistance to the BJP’s policies could go on. Even though the party won national elections last May, it has lost power in five states since 2018 and may lose more this year. In a democracy, where the principle of equality for all people before the law is sacred, the use of hatred to win votes or to hold power is easily exposed.

Politics of hate loses a key vote in India

The Muslim minority in the world’s two most populous countries, China and India, have lately felt very much under siege. Since 2017, China has shut mosques and rounded up its Uyghur Muslims for mass “reeducation.” In December, India passed a new citizenship law for migrants that purposely excludes Muslims. It was the first time that religion has been used to grant nationality despite India’s secular constitution. In other moves, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has signaled it seeks a Hindu-centric nation.

In each country, the anti-Muslim discrimination differs in scope and intensity. Yet one other difference stands out.

In India, which is the world’s largest democracy, both Muslims and non-Muslims have held sustained protests for two months against the new citizenship law, the largest demonstrations in decades. Even more important, voters appear to be in revolt. On Feb. 8, the BJP suffered a massive defeat in local elections in New Delhi, despite intense campaigning by the party’s leader, Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

With 20 million people, the nation’s capital is a microcosm of the country. The BJP won only 8 of 70 seats in the city’s assembly while the other seats went to the local Aam Aadmi Party (Common Man’s Party, or AAP). Its leader, Arvind Kejriwal, is a well-known anti-corruption activist who, as Delhi’s chief minister since 2013, has implemented popular anti-poverty projects. He opposes any fear-mongering against Muslims.

One of the AAP’s top leaders, Sanjay Singh, said the election result is a mandate against hate. Mr. Kejriwal says the vote “is a victory for Mother India, for our entire country.” Indeed, the election was seen as a referendum on Mr. Modi’s politics of division and his image as protector of Hindus, who are about 80% of the population.

The resistance against the BJP’s policies could go on. Even though the party won national elections last May, it has lost power in five states since 2018 and may lose more this year. In a democracy, where the principle of equality for all people before the law is sacred, the use of hatred to win votes or to hold power is easily exposed.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Different perspectives? No problem.

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By John Biggs

When people have different beliefs or opinions, is conflict inevitable? At an interfaith gathering, a man experienced how a humble willingness to consider what God is doing and seeing at this moment lets in God’s unifying, healing light.

Different perspectives? No problem.

I was representing my local Church of Christ, Scientist, at a “belief fair” hosted by a local university, where faith groups in the area were invited to come and share information. It was a decidedly friendly campus event, and I had gotten into conversation with a man representing another faith community.

We appreciated sharing with each other our love for God and for the power of prayer. I began to feel a little flustered, though, when the conversation took a turn. It seemed to me that the man wasn’t really listening to what I was sharing and was only trying to share his point of view.

After a while, he asked if we could pray quietly together. This is one of my favorite things to do, so I happily agreed. I closed my eyes and mentally thanked God for being there – right here, loving everyone gathered on that university lawn – and then I asked to see even more clearly what God was doing and seeing at that moment.

I felt overcome with a tangible sense of the presence and all-inclusiveness of God, the divine Spirit. Gratitude for God welled up in my heart in a totally fresh way – and it included gratitude for both God and all of God’s children.

It was so moving. I wasn’t trying to convince myself that everyone (including the man who had seemed so off-puttingly pushy) is God’s child, the spiritual image of the Divine. I simply felt deeply aware that, yes, God is truly our heavenly Father-Mother, our perfect creator, and as such, is the unifier of us all. We are God’s work!

I felt I was experiencing something of what Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, says in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures”: “One infinite God, good, unifies men and nations; constitutes the brotherhood of man; ends wars; fulfils the Scripture, ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself;’...” (p. 340).

This statement is based on the implications of the depth and breadth of the First Commandment: “Thou shalt have no other gods before me” (Exodus 20:3). The oneness of God implies a cohesiveness in all His work, a freedom from friction or faction. And we can demonstrate that divine harmony in our activities.

My frustration with the other man fell away. Now, I just felt so much more aware of God’s presence that I was eager to open my eyes and see evidence of the goodness He expresses at every moment!

Well, I opened my eyes, and the man I was speaking with was looking intently at me. He said, “My back doesn’t hurt anymore!” He went on to explain that his back had been troubling him for a long time, but as we were praying he’d felt all the pain just vanish.

He asked what I’d been praying about, and I said, “God just loves us all so much, doesn’t He?” The man gave me a big smile and said, “Yes, He does!”

I certainly hadn’t been praying specifically for this man – I hadn’t even known of his trouble. But nothing can interrupt the harmony of divine Spirit. And each of us, after all, is truly spiritual, reflecting God’s nature. These spiritual facts are universal, there for all to experience.

The fresh view of God’s allness and oneness I had that day has helped me realize that cutting through inharmony between people of different faiths – or different politics, backgrounds, etc. – isn’t about trying to make everyone agree. The power of God, good, isn’t determined by what viewpoints people have. God just is, and when we start from the vantage point of the universality of God’s harmony and love, seeing ourselves and others in God’s light, healing is a natural result.

A message of love

True grit

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we look at the tough questions coming to the surface as Germany pushes toward aggressive targets for transitioning to renewable energy. Like, are wind farms really making a positive difference?