- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Biden, Sanders, and the struggle for the Democrats’ future

- What happens to rule of law if the law keeps changing?

- Can Putin and Erdoğan once again keep their countries from going to war?

- Saving the Amazon: How cattle ranchers can halt deforestation

- Shelf love: Go behind the scenes with ‘The Booksellers’

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What Lincoln might have said on Super Tuesday

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today’s stories include the Democrats’ choice between restoration and revolution, a Supreme Court wrestling with America’s sharp political swings, the prospect of a Russia-Turkey war, paths to progress in the Amazon, and the perfect film for book lovers.

As the United States moves through its primaries and toward electing a president, two things jump out. First, the rhetoric suggests a moral divide, with both sides seeing the election as a stark choice on the direction of the country. And second, despite this polarization, there remains a yearning for a return of respect and reconciliation.

The problem, of course, is that the two things seem mutually exclusive. It’s in this light that I read a review in The Economist of “Every Drop of Blood,” a book about Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address. The speech is seen as one of the greatest political addresses in American history, and it was rooted in Lincoln’s moral outrage at slavery. The language was of the thundering judgment of Ezekiel and Jeremiah in the Bible. African Americans in the crowd wept and cried out, “Bless the Lord.”

And yet he finished on a different note, imploring that “with malice toward none, with charity to all … let us strive to finish the work we are in.”

Tellingly, The Economist notes, “America’s partisan newspapers reviewed the address according to their biases.” But Lincoln was aiming at something larger than the fumbling fingers of bias could grasp – a place where conviction and reconciliation are intertwined. In that place, he argued, was America’s uniqueness and greatness.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

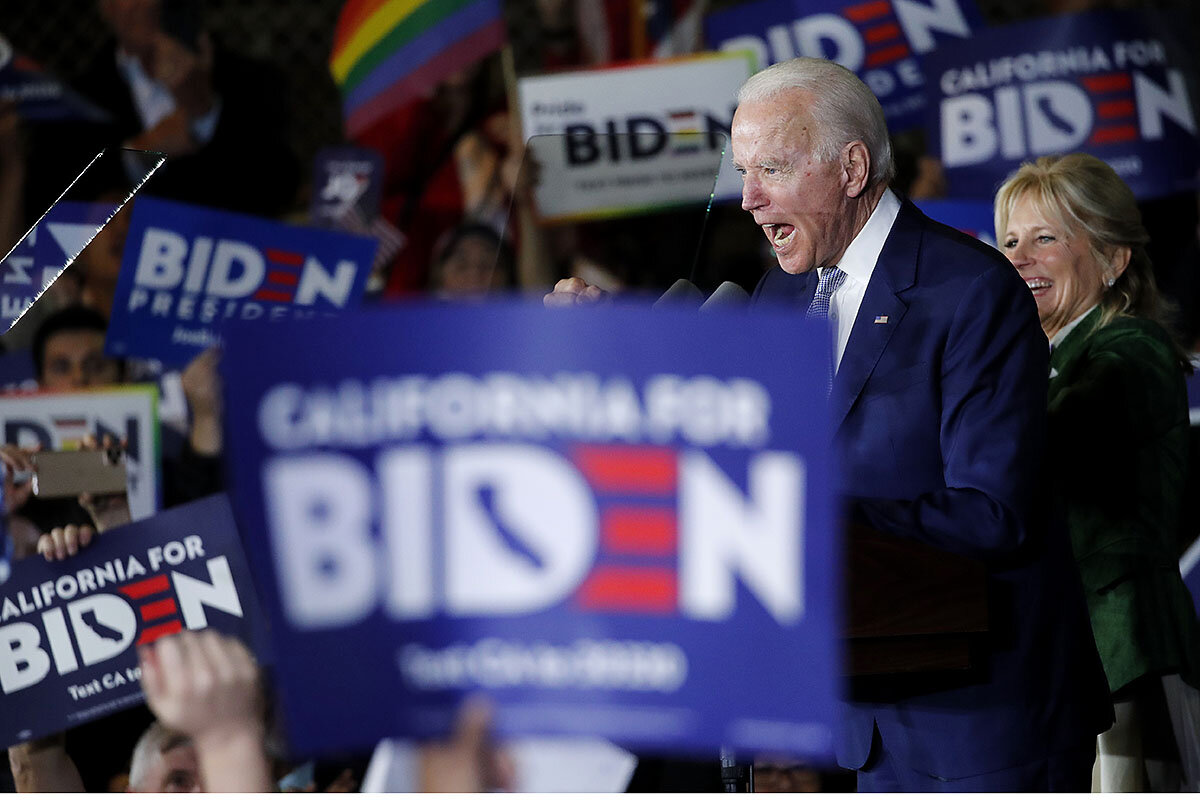

Biden, Sanders, and the struggle for the Democrats’ future

After Super Tuesday, the Democratic presidential race became a clear choice between the restoration of an Obama-era vision and a wholesale political revolution.

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

By almost any measure, Super Tuesday 2020 was a stunning uplift for an American politician who has been a fixture in Washington since winning a Senate seat in 1972.

Joe Biden has run for the nation’s highest office three times. Before last Saturday in South Carolina, he had never won a primary. Now he has won 11. And almost overnight, the roller coaster that has been the 2020 Democratic primary process ended up back where it started: with the former vice president as the front-runner and candidate with the clearest path to winning the nomination.

But don’t unbuckle yet. Sen. Bernie Sanders still has money, organization, and a devoted following on his side.

And Super Tuesday didn’t solve the basic division within the Democratic Party, which pits Senator Sanders, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, and other progressive revolutionaries against moderates who wish to restore Obama-era priorities. That’s a split so fundamental it could cause intramural friction for years to come, no matter who wins the party’s 2020 nod.

Biden, Sanders, and the struggle for the Democrats’ future

So far, watching the 2020 Democratic primary process has been like riding a world-class roller coaster, full of wild swings, sudden climbs, and stomach-churning plummets.

And like a spin around Cedar Point amusement park’s “Steel Vengeance,” it has ended up back where it began: with former Vice President Joe Biden as the frontrunner and candidate with the clearest path to winning the nomination.

But don’t unbuckle yet. Sen. Bernie Sanders still has money, organization, and a devoted following on his side. Democratic Party rules, which award delegates on a proportional basis in each state, favor a close race.

There’s a debate scheduled for March 15 that will be essentially one-on-one. Events held a day or so prior to a vote have seemed extraordinarily influential this primary season.

Nor did Super Tuesday solve the basic division within the Democratic Party, which pits Senator Sanders, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, and other progressive revolutionaries against moderates who wish to restore Obama-era priorities. That’s a split so fundamental it could cause intramural friction for years to come, no matter who wins the party’s 2020 nod.

While the restoration wing of the party seeks a return to political norms, civility, and respect for all after years of growing polarization, the progressive wing argues that the United States needs bolder, sweeping changes to everything from health care to climate change.

“I suspect everybody will get together and try to make sure we get rid of Trump. If that happens, we will postpone this conflict a little bit. But it will come back,” says Bill Carrick, a longtime Democratic consultant in Los Angeles.

From zero primaries to 11

Still, by almost any measure, Super Tuesday 2020 was a stunning uplift for an American politician who has been a fixture in Washington since winning a Senate seat in 1972, then served eight years as vice president, yet never before gained any momentum for his own burning presidential ambitions.

Joe Biden has run for the nation’s highest office three times. Before last Saturday in South Carolina, he had never won a primary. Now he has won 11. The other moderates in the race have dropped out and endorsed him.

He currently leads in delegates, with an estimated 433, according to a mid-afternoon Wednesday estimate from The New York Times. Senator Sanders trails with 388.

Mr. Biden benefited from a sudden coalescing of center-left Democrats around his candidacy. With Mr. Sanders surging, these voters decided it was time to settle, not moon after political crushes. African-American voters were crucial to the Biden coalition, which included substantial numbers of working-class whites and college-educated women.

Biden voters interviewed in Virginia’s 7th Congressional District, won by Democratic Rep. Abigail Spanberger in 2018 after 38 years of Republican representation, spoke of a number of reasons why they supported the former vice president. But one thing was on top of many of their lists.

“I just want him to beat Trump,” says Amy Davis, an African-American stay-at-home mom from Culpeper.

Ms. Davis adds that she also thought Mr. Biden did a good job as vice president.

“He impressed me when he worked under Obama,” she says.

Coming to Biden

Some Biden supporters said they had switched from other candidates.

Pat Carl, a retired white man serving as a poll watcher with the Spotsylvania Democrats, says originally, he liked Sen. Amy Klobuchar, who withdrew from the race and endorsed Mr. Biden earlier this week.

But Mr. Carl says he’s confident that a Biden administration would have a place in it for Senator Klobuchar. And as a former Republican, he’s attracted by Mr. Biden’s ideological position in the Democratic Party.

“I’m a moderate kind of person,” he says.

Several Virginia Biden voters volunteered that they’d cast a ballot for President Donald Trump in 2016. They’d believed in his “Make America Great Again” slogan.

But they’ve found his behavior as president off-putting.

“Now he’s just lashing out at everyone, firing his own staff. I’m so disappointed in him,” says Alan Burnham, a white male school bus driver.

Given all the uproar over Mr. Biden’s sudden reemergence as the Democratic front-runner, it is easy to forget that only about one-third of the total number of pledged state delegates to the party convention in Milwaukee have been chosen. There is plenty of time remaining for a Biden stumble, or a Sanders rally.

Six states hold primary votes March 10, including the crucial Rust Belt state of Michigan. Four more states vote March 17, including Florida and Ohio.

Biden’s flaws; Sanders’ strengths

As a candidate, Mr. Biden has flaws. That is part of the reason why he struggled to raise funds and attract voters in the primary season’s initial contests.

On the stump he is prone to garbled speech and other verbal miscues – at his victory appearance Tuesday night, for instance, he mistakenly identified his wife as his sister, and vice versa. (He quickly corrected the error.) He’s been known to run on, and on. Sometimes he gets names mixed up. Given his length of service in Washington, he’s not exactly an exciting new face.

“I don’t think he’s a weak candidate. I think he’s got some weaknesses as a candidate,” says Garry South, a longtime Democratic consultant based in Los Angeles.

But Democrats will start to look at Mr. Biden and see that “at the end of the day, that’s part of what makes him authentic,” Mr. South says.

Meanwhile, Mr. Sanders has strengths. His campaign is flush with cash, and his ability to raise small dollar donations online remains unparalleled. Many of his supporters are devoted in a way that Biden voters don’t appear to be. His rallies draw tens of thousands of fans to hear him excoriate billionaires and corporations and promote Medicare For All and free tuition at public colleges and universities.

For all the attention given to Mr. Biden, the two men remain almost tied in the currency that matters most, delegate strength, Senator Sanders pointed out in an appearance at his Burlington, Vermont campaign office Wednesday.

“What this campaign … is increasingly about is, which side are you on? Our campaign is unprecedented” when it comes to grassroots support, Mr. Sanders said.

In Virginia, primary voters who opted for Senator Sanders stressed his appeal to young people, and how his proposals went to the heart of their concerns.

Amber Seagrave, a young white woman with pink hair who works as a stylist, says she voted for him in part because of his proposals to eliminate student loan debt.

“I’m going to be late on my student loans again this month,” says Ms. Seagrave. “I had to drop out of college because I couldn’t pay for it.”

Limits to the division

The Democratic nightmare is that the animosity between the Sanders and Biden camps will extend past the convention, and that the loser’s side will sit on its hands and have a lower turnout rate for the general election.

“Over the next month or so, we will see a lot of animosity, anger, resentment. It will look bad and end up feeling pretty similar to 2016,” when bad feeling developed between the Hillary Clinton and Sanders campaigns, says Prof. David Barker, director of the Center for Congressional and Presidential Studies at American University.

But Professor Barker says there are several reasons why this division won’t end up being as consequential as it was four years ago.

For one thing, President Trump is an incumbent both sides want very much to oust. For another, Joe Biden is not Hillary Clinton. Ms. Clinton generated antipathy from both Republicans and the Democratic left wing. Mr. Biden perhaps doesn’t produce that level of animosity.

“The thing about Biden now is that while he doesn’t excite the young progressive left, he also doesn’t inspire the same level of loathing. There seems to be some level of warmth for the guy,” says Professor Barker.

Francine Kiefer contributed to this story.

What happens to rule of law if the law keeps changing?

Interpretations of law change over time, of course. But a case before the U.S. Supreme Court highlights what can happen when politics flip-flop so wildly and quickly.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Four years ago – no time at all in the relatively geologic pace of the high court – the U.S. Supreme Court found a Texas law unconstitutional in placing an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to seek an abortion. But the opinion went further, articulating a test that regulation must satisfy to be constitutional.

For Amy Hagstrom Miller – head of Whole Woman’s Health, the lead plaintiff – it “was a pretty powerful thing to witness.”

Today, the Supreme Court heard arguments in a case involving a Louisiana law virtually identical to the Texas law it struck down. One feature that is not the same: the court itself, with the absence of Justice Anthony Kennedy, who cast the deciding vote in 2016.

It leaves the justices grappling with not only one of the country’s most polarizing issues, but also with the broader implications its ruling could have on their own institutional strength and the rule of law.

“People have very strong feelings and a lot of people morally think it’s wrong, and a lot of people morally think the opposite is wrong,” said Justice Stephen Breyer. “I think personally the Court is struggling with the problem of what kind of rule of law do you have in a country that contains both sorts of people.”

What happens to rule of law if the law keeps changing?

When Justice Stephen Breyer began to speak, Amy Hagstrom Miller could barely believe it.

As he continued, she began to wonder if she was in the U.S. Supreme Court at all, or if she was dreaming.

The headline from Justice Breyer’s majority opinion four years ago, in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, was that the 5-to-4 decision found a Texas law unconstitutional in placing an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to seek an abortion. But the opinion went further, articulating a test of the potential medical benefits and burdens that regulation must satisfy to be constitutional.

For Ms. Miller – president and CEO of Whole Woman’s Health, the lead plaintiff in the case – it “was a pretty powerful thing to witness.”

“Not just the findings of fact, but the reasoning in the decision was beyond anything I’d dared dream,” she adds. “Sitting in that courtroom, I know other states are going to benefit from this.”

That was four years ago – no time at all in the relatively geologic pace of the high court – and those benefits are now under scrutiny. Today, the Supreme Court heard arguments in a case involving a Louisiana law virtually identical to the Texas law it struck down in 2016. One feature of today’s case that is not the same as four years ago: the Supreme Court itself, with two new conservative jurists, including one in place of Justice Anthony Kennedy, a deciding vote in Whole Woman’s Health.

As the argument in today’s case, June Medical Services v. Russo, illustrated, it leaves the justices grappling with not only one of the most partisan and emotional issues in the country today, but also with the broader implications its ruling could have on their own institutional strength and the rule of law.

“People have very strong feelings and a lot of people morally think it’s wrong, and a lot of people morally think the opposite is wrong,” said Justice Breyer near the end of today’s argument. “I think personally the Court is struggling with the problem of what kind of rule of law do you have in a country that contains both sorts of people.”

Citing eight precedents on abortion, he told Deputy Solicitor General Jeffrey Wall, “You really want us to go back and reexamine this, let’s go back and reexamine Marbury versus Madison,” the 1803 decision establishing federal courts’ power of judicial review.

“Why depart from what was pretty clear precedent?” he continued.

How different?

Abrupt shifts in decision-making are customary in the executive and legislative branches of U.S. government. In the courts, however, it could have dangerous ramifications for the rule of law.

“It’s very difficult to be a law-abiding person, if [the law] is constantly changing,” says Kenneth Williams, a professor at South Texas College of Law in Houston.

“Courts have traditionally been very reluctant, and proceeded very slowly at overturning precedents,” he adds. “But those restraints seem to be lessening more recently as courts become more partisan, as the judges have become more partisan.”

The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has long been one of the most conservative appellate courts. It upheld the Texas law later struck down in Whole Woman’s Health. The Supreme Court justices ruled that the law had “no ... health related benefits” and would shutter half of the abortion clinics in the state.

Federal district Judge John deGravelles followed that ruling when, in 2016, he blocked Act 620, the Louisiana law, from going into effect. The law, he found, would leave “one provider and one clinic” in the whole state. (The Monitor visited one of the clinics last year.)

A three-judge panel of the 5th Circuit reversed that ruling, writing that Act 620 was “remarkably different” from the Texas case. Since obtaining admitting privileges in Louisiana isn’t as difficult as in Texas, they said, the law would only potentially close one clinic and “affect, at most, only 30% of women.”

Chief Justice John Roberts – considered the court’s ideological center since Justice Kennedy retired – asked a similar question during Wednesday’s argument. Instead of Whole Woman’s Health being the national standard, he asked Julie Rikelman, a Center for Reproductive Rights attorney, should regulations in different states be evaluated individually?

“You have to have the district court examine the availability of specific clinics and the admitting privileges of doctors” in each state, he continued. “Couldn’t the results be different in different states?”

They could be different in different states, Ms. Rikelman replied, but since the Supreme Court ruled in 2016 that the Texas admitting privileges law “was medically unnecessary and its burdens were undue, that holding should clearly apply to Louisiana's identical law.”

“Up for grabs”?

When re-evaluating a precedent, the Supreme Court is supposed to apply the stare decisis doctrine. Specifically, the justices are supposed to consider four factors: the quality of the past decision’s reasoning, its consistency with related decisions, legal developments since the past decision, and reliance on the decision throughout the legal system and society.

“In the abortion area [stare decisis] is a little bit for up for grabs,” says Gillian Metzger, a professor at Columbia Law School, since the right to an abortion has been contested for decades – from before the Supreme Court declared it constitutional in Roe v. Wade in 1973.

“But I don’t think Whole Woman’s Health marked a significant departure from” past abortion precedent, adds Professor Metzger, who co-authored an amicus brief in support of the groups challenging Act 620.

The older a precedent, the more courts and society have come to rely on it, stare decisis doctrine holds. In that sense, it could be less damaging to adjust or overturn a relatively new precedent.

On the other hand, “with a three year-old or four year-old precedent, you’re almost never going to have a different circumstance that would warrant overturning it,” says Professor Williams.

That may not be the case with another precedent Wednesday’s case is raising, however.

Third-party standing

Instead of narrowing, or overruling, Whole Woman’s Health, the justices could focus on a second question raised in a cross-petition from the state of Louisiana: whether abortion providers have “third-party standing” to challenge regulations on behalf of patients.

Justice Clarence Thomas, one of the court’s most conservative members, has often criticized allowing abortion providers to use it, and Justice Samuel Alito expressed similar thoughts during today’s argument.

“The constitutional right at issue is not a constitutional right of abortion clinics, is it? It’s the right of women,” he said. “Can there be third-party standing if there is no hindrance whatsoever to the bringing of suit by people whose rights are at stake?”

The Supreme Court has applied third-party standing in abortion and other medical contexts for almost 50 years.

If abortions clinics are blocked from challenging abortion regulations, only women seeking an abortion would be able to. With the stigma associated with abortion cases, combined with the fact that litigation usually lasts longer than the time period in which a woman could get an abortion, those plaintiffs would likely be difficult to find, says Melissa Murray, a professor at New York University School of Law.

“A lot of people probably wouldn’t understand what it means for doctors to lack standing,” she continues, “but lawyers in this field would know immediately that [it] would make it much harder to bring these challenges.”

Insubordinate circuits?

It may be that the Supreme Court would have preferred to not hear this case at all – or at least not for a few years. The 5th Circuit had other ideas.

“By not adhering to pretty clear precedent [the 5th Circuit] put the Supreme Court in a position where it had to take this case, even if it would have preferred to wait and see how the law develops,” says Professor Metzger.

And if the justices uphold the 5th Circuit’s ruling, she adds, “it really is inciting other lower courts who are so inclined to take similar steps and really push issues onto the Supreme Court’s agenda.”

Abortion has for decades been an emotional, polarizing issue. That political heat has intensified in recent years with candidate Donald Trump pledging to nominate justices who would “automatically” overturn Roe.

His two appointees to the high court – Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh – both described Roe v. Wade as settled precedent during their confirmation hearings. Both were also relatively quiet during today’s argument (Justice Gorsuch didn’t ask a single question).

But “if the court is seen as hollowing out Whole Woman’s Health only four years [later], there’s going to be a lot of people ... who will see this as a political decision,” says Professor Murray.

“That’s something Chief Justice Roberts, who has been a steward of court’s institutional integrity, is thinking about, or should be thinking about,” she adds.

Can Putin and Erdoğan once again keep their countries from going to war?

When Russia entered the Syria war, it put itself on a collision course with Turkey. The tense relationship is now nearer a breaking point than ever before.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Since Russia intervened in Syria’s civil war five years ago, Russian and Turkish forces have come close to conflict in the region more than once. And in the last week, the relationship between the two has reached a new nadir, after three dozen Turkish troops died in the Syrian province of Idlib, some of them in airstrikes likely carried out by Russia.

Now the onus will be on Presidents Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to once again pull their two countries away from the brink of war when they meet in Moscow on Thursday. The most likely outcome of the Putin-Erdoğan talks is a fresh agreement to regulate the crisis, with an accompanying cease-fire, but with perhaps more of the province’s territory being ceded to the government of Syria’s Russia-backed president, Bashar al-Assad.

Mr. Putin and Mr. Erdoğan “both know full well, despite all this brinksmanship, that a direct confrontation between Russia and Turkey has to be avoided at all costs,” says Andrei Kortunov, head of the Russian International Affairs Council. “They will almost certainly find a way to make things quiet down, at least for now.”

Can Putin and Erdoğan once again keep their countries from going to war?

One of the most dangerous flashpoints on earth at present is the northwestern Syrian province of Idlib.

There, Turkish and Russian military units tensely face each other while their proxy forces wage all-out warfare around them. Three dozen Turkish troops have died in the past week, some of them in airstrikes likely carried out by Russia. A war between Russia and Turkey, along with the explosive shock to the already fraying global order that it would bring, looks disturbingly possible.

The question is whether Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Turkish counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who are set to meet Thursday in Moscow, can once again confound predictions of doom around their two nations.

They have negotiated a path out of conflict in the past, particularly when Turkey shot down a Russian fighter plane over northern Syria in 2015. Moreover, Mr. Putin has skillfully drawn Mr. Erdoğan closer to Russia’s orbit by encouraging important mutual dependencies, such as the $12 billion TurkStream pipeline, inaugurated by the two leaders earlier this year, to carry Russian natural gas to southern Europe via Turkey. In the military sphere, Turkey has defied its NATO allies by purchasing the advanced Russian S-400 air defense system.

But everyone agrees that this is by far the worst moment in a relationship that’s been a nail-biter since Russia intervened in Syria’s civil war. And even if a resolution can be found, experts warn it may end up just kicking the can down the road.

“Russia and Turkey need each other, even if their goals collide,” says Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of Russia in Global Affairs, a leading Moscow-based foreign policy journal. “Neither can accomplish anything unless the other at least acquiesces, and that is why they regularly craft these ‘solutions’ that solve nothing but lead over time to even worse crises.”

Close quarters in Syria

Russia’s intervention in Syria almost five years ago ended up derailing Turkish hopes for expanded regional influence after what – at the time – looked like the certain removal of the Bashar al-Assad regime in Damascus.

To manage their differences over Syria, the two agreed at a meeting in Sochi, Russia, in late 2018 to create a buffer zone in Idlib, which would be off-limits to Syrian troops while Turkey would protect about 3 million refugees who have fled from rebel-held zones in Syria that have been overrun by the advancing Syrian army.

The plan was that Turkey and Russia would jointly oversee a cease-fire while Turkey used its authority to separate irreconcilable jihadi rebels, particularly those linked with Al Qaeda, from civilians and more moderate anti-Assad opposition in preparation for an eventual peace settlement that would reintegrate the province into Syria.

None of that has happened. Moscow accuses Turkey of backing extreme Islamist rebels instead of disarming and isolating them, and trying to entrench its own permanent control over Idlib. In the past couple of months, Syria has stepped up military operations, with Russian air support, aimed at taking territory and controlling two vital highways.

In recent days Russia has bolstered its forces in Syria and let it be known that four warships armed with deadly Kalibr cruise missiles will be joining its flotilla in the eastern Mediterranean. Russia’s Defense Ministry warned this week that it “cannot guarantee” the safety of Turkish planes flying over Idlib, which sounds a lot like Russian for “no-fly zone.”

The offensive has created what the United Nations calls a humanitarian disaster, with hundreds of thousands of refugees pushed up against the Turkish border with nowhere to go, and Turkey threatening to unleash a major military assault to push Syrian forces back.

“Erdoğan’s view is that as long as Assad is in power, the people of Idlib will be unwilling to return to Syria and it will be Turkey’s duty to protect them,” says Andrei Kortunov, head of the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry. “But Assad is impatient to end the war, and move on to reconstructing the country. The continued presence of heavily armed jihadi forces that are dedicated to overthrowing the regime isn’t something he will tolerate indefinitely. And Russia’s ability to control Assad is far from certain.”

Drawing new lines

Meanwhile Turkey, which already houses almost 4 million Syrian refugees, claims it will open the floodgates and allow them to migrate to Europe unless NATO and the European Union take steps to support Turkey in this crisis.

Yet NATO seems no more likely to come to Mr. Erdoğan’s rescue in this standoff with Russia than it was in previous tense moments.

“If the worst happens and it comes to war, there seems no option for Putin but to support Assad,” says Mr. Lukyanov. “That will not go well for Turkey. And as long as the fighting is confined to Syrian territory – which Turkey is illegally occupying – it will not trigger NATO intervention. We see absolutely no appetite in Europe, or even the United States, to get involved in something like that.”

The most likely outcome of the Putin-Erdoğan talks is a fresh agreement to regulate the crisis in Idlib, with an accompanying cease-fire, but with perhaps more of the province’s territory being ceded to the Syrian government.

“I can picture Putin and Erdoğan sitting and studying a map of Syria, figuring out where to draw the new lines. They will probably find a compromise, but it will be a very fragile and temporary one. Both have very limited possibilities to control the ambitions of their proxies,” says Mr. Kortunov.

“Both know full well, despite all this brinksmanship, that a direct confrontation between Russia and Turkey has to be avoided at all costs,” he says. “They will almost certainly find a way to make things quiet down, at least for now.”

Editor's note: The original version misquoted Mr. Lukyanov about the relationship between Russia and Turkey.

Saving the Amazon: How cattle ranchers can halt deforestation

Solutions often reside in the problem itself. In Brazil, the cattle ranchers responsible for widespread deforestation may now hold the key to halting further environmental destruction.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The pastures on Fazenda Mitaju, a cattle ranch in Brazil’s central state of Mato Grosso, are dotted with hundreds of white Nelore cattle and fringed by remnants of the lush, tropical Amazon rainforest that survived clearing that began in the 1970s.

Wellison Oliveira Silva supervises this 530-hectare (1,300-acre) ranch. His goal: to intensify productivity and get the 2,500 heads to slaughter faster. To many minds, this would make him one of the most mistrusted figures on the planet. In August, when fires burned in the Amazon, the international community shined a harsh spotlight on Amazonian cattle farmers. After all, the industry is responsible for up to 80% of deforestation across the rainforest.

But Mr. Silva is not bent on fast cash. He’s part of a movement that seeks to intensify production on severely degraded pastures and turn them into efficient and sustainable operations – all without losing a single hectare more of forest. His is one of many efforts rushing to generate cleaner sources of beef while revamping one of the most maligned industries in the Amazon.

As Mr. Silva says, “This is the evolution of the cattle industry in the Amazon.”

Saving the Amazon: How cattle ranchers can halt deforestation

The white Nelore cattle, their characteristic hunch above their shoulders, graze in the bright green pastures of the Fazenda Mitaju ranch. Around them is the tropical rainforest that survived the clearing of the Amazon that began in the 1970s, when the government lured Brazilians here to settle the vast territory.

Wellison Oliveira Silva supervises this 530-hectare (1,300-acre) ranch. He records the animals’ feed intake daily, rotating them to different parcels of pasture if they are eating too much or too little, and measures the height of the Mombaca grass planted here, which stands anywhere from knee- to waist-high.

His goal: to intensify productivity and get the 2,500 heads to slaughter faster.

To many minds, this would make him one of the most mistrusted figures on the planet. In August, when fires burned in the Amazon, the international community shined a harsh spotlight on Amazonian cattle farmers. And that’s fair. The industry is responsible for up to 80% of the deforestation across the rainforest, according to Yale University’s School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

But Mr. Silva is not some gnarled farmer intent on fast cash. He’s a 20-something employed by Pecsa (which stands, in Portuguese, for Sustainable Cattle Ranching in the Amazon). A private company spun off from an environmental nongovernmental organization, the group seeks to intensify production on severely degraded pastures and turn them into efficient and sustainable operations. The group believes it’s possible to do so without losing a single hectare more of forest – even as demand for beef from Brazil continues to soar.

Here in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil’s largest cattle-producing region, ranches that once caused deforestation may now help stop it. “If we don’t start to produce twice, three times, four times and then 10 times more on the already cleared areas, they’re going to clear the Amazon,” says Laurent Micol, a co-founder of Pecsa.

Pecsa joins many efforts – some carrot, some stick, and many controversial – rushing to enforce, incentivize, and generate cleaner sources of beef. In doing so, it hopes to strike a win-win for one of the most maligned sectors in the Amazon.

Battling stigma

Brazil is a leader in forest protection. Its Forest Code requires that up to 80% of a landowner’s property in the Amazon biome be preserved as forest, depending on when it was purchased and how big it is. As environmental pressure has grown over the years, those laws have been more rigorously enforced. The government implemented an environmental registry for each property that maps who owns what and what is produced, and uses satellite imagery to monitor deforestation.

But resources are limited and enforcement sometimes lax. And many worry the Amazon is more vulnerable now that Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has taken a pro-development stance in the Amazon that has made him wildly popular.

After dropping dramatically since 2004, deforestation rates have crept up in recent years. Fears came to an international head in the fires last August. Much of the fires were man-made, with land-grabbers, from loggers to cattle ranchers, burning forest to create more pasture.

That’s led to stigma across the entire industry, which comprises more than 200 million heads of cattle.

“The problem is we have a lot of producers of cattle or soybean close to or in the Amazon that are not burning. They are suffering. They are considered the same as deforesters,” says Charton Locks, the chief operating officer of Aliança da Terra, which works to foster sustainable farming in Brazil. “For the international community, it’s all the same. Companies start to avoid buying products from Brazil, which creates a problem for the good producers.”

So Aliança da Terra is trying to differentiate the good farmers. It has built a “Producing Right” platform of 1,500 members, representing more than 5 million hectares of farmland, who adhere to preserving forest, protecting wildlife, and improving social and labor conditions on their ranches.

Rescuing degraded land

On a recent day Willian Campos, a veterinarian by training, visits Fazenda Gamada, a soy and cattle farm an hour from Alta Floresta. He is in charge of ensuring participating farms follow a checklist of over 200 items, a process so rigorous that Mr. Campos says some producers back out once they begin. But those who continue can enter deals with supermarket chains that pay a premium for commodities from green ranches, creating what Mr. Locks calls “a positive ecosystem.”

But not all farms adhere to such high standards voluntarily, and according to many environmentalists, incentives cannot work without stricter enforcement, beyond the current government controls.

In 2009, Greenpeace won a pledge from the largest meatpackers in the Amazon to reject sales from deforested properties. But the results have been limited: Not only does the program not include all meatpackers, monitoring has been limited to direct suppliers, typically the finishing ranch that sells to the meatpacker. That leaves the supply chain exposed.

“I think what’s happened so far is that there are a lot of loopholes, and so people don’t have to take it seriously,” says Lisa Rausch, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Using publicly available data, her team and the National Wildlife Federation have developed a traceability tool called Visipec that allows meatpackers to trace indirect suppliers. They are a significant part of the supply chain that could be responsible for about 50% of the deforestation driven by the cattle sector in the Amazon.

Visipec has been available since 2019 and is being offered to the industry for free. But its designers, who say it’s good for business too, say no meatpackers have fully implemented the tool yet.

So-called zero deforestation commodity agreements have been criticized for alienating farmers who are under increasing pressure from the international community. This came to a head in Alta Floresta a decade ago, when the municipality found itself on a government blacklist for deforestation.

That’s how the seeds of Pecsa were planted. Many of those who work at the company today were working at an NGO at the time that helped get farmers off the blacklist.

Alta Floresta is a booming town that sits in the “Arc of Destruction, where today only 45% of the original forest remains. Much of the ranch land is badly degraded, littered with termite mounds that signal nutrient-poor soil below. Many ranches operate at a loss. Pecsa reimagined that land by reforming degraded ranches into sustainable, productive systems that removed incentives to cut deeper into the Amazon.

Pecsa’s model is unlikely. The 65-person team of MBAs, data specialists, zoo technicians, agronomists, and environmentalists take over ranches in multiyear contracts, implementing all of the necessary and costly reforms to transform the property. They invest in new grass to improve the soil, increase the density and productivity, and reforest areas that legally should be conserved. The owners share a percentage of the output.

Transforming cattle ranching

Nothing they have implemented is revolutionary – but their results have been. On a recent afternoon, Mr. Micol, the Pecsa co-founder, drives through muddy roads that cut through a farm they will manage until 2022. When they took over in a pilot project in 2011 and completely in 2016, the grass on this farm, a half-hour west of Alta Floresta, was almost all dead, yellow, and littered with invasive species. The hills around a natural springhole, where the animals would drink, were denuded.

There are now five cattle per hectare, compared to one per hectare when Pecsa took over. Today, the 2,500 cattle drink water and eat feed at a single “leisure center.” When the pasture gets too low, they are rotated to another.

“We consciously decided not to do something too green, not something that was going to be organic, or more ecological,” Mr. Micol says. “It’s just meant to be efficient.”

They have been able to increase productivity, in terms of animal stocking and weight gain, by almost 10 times compared with the region’s average on degraded lands. A study contracted by Imaflora, an NGO, showed that Pecsa-produced meat uses 84% less land and emits 85% fewer greenhouse gases than the baseline. McDonald’s ended its nearly 40-year moratorium on Amazonian beef with a Pecsa contract in 2016.

Pecsa is currently managing 30,000 heads of cattle on 10,000 hectares of ranchland over six properties, with aims to expand to 150,000 heads on 45,000 hectares in three years. “Our purpose is not to run six ranches,” says Mr. Micol, who began his career as a management consultant. “Our purpose is to transform cattle ranching in the Amazon.”

Mr. Silva, the Pecsa supervisor, managed a much larger farm in his previous job. But he joined the staff because he sees it as training for the future. “This is the evolution of the cattle industry in the Amazon,” he says.

On Film

Shelf love: Go behind the scenes with ‘The Booksellers’

A new documentary suggests that books are not only an escape, but also a way of being fully human. Monitor film critic Peter Rainer says the basic urge they satisfy will never age.

-

By Peter Rainer Film critic

Shelf love: Go behind the scenes with ‘The Booksellers’

“The Booksellers” is a documentary for people who treasure the sheer look and feel of books. It is for anyone who has ever spent way too much time in used and rare bookstores teetering on tall ladders or squeezing through narrow, tome-filled aisles in search of that most precious of commodities: the book you didn’t know you needed until you found it – or, to be more precise, it found you.

As a proud member of this diminishing tribe of obsessives, I am grateful there exists a film featuring my spiritual kinfolk, even though it is fairly New York-centric and much more about fanatic book dealers than fanatic book buyers. (It turns out, in the used and antiquarian book world, there’s not much of a difference.) Although he doesn’t identify some of them on screen, director D.W. Young has chosen his camera subjects carefully, almost lovingly: He never makes fun of them. He’s smart enough to recognize that the most self-aware among them are more than capable of poking fun at themselves.

Take Dave Bergman, for instance, a rare book dealer whose apartment apparently serves as the holding cell for his wares. He specializes in oversized books, some of which, like a volume on the catacombs of Rome, are so heavy that he hasn’t reshelved them in decades. He shows off a 1907 book on woolly mammoths that contains, as a bonus, a packet of woolly mammoth hair (presumably authenticated). A note of sly self-deprecation runs through his litany, but you can also tell that these books, and the worlds they have opened to him, are his lifeblood.

The same is true of rare book and ephemera collector Michael Zinman, celebrated in a 2001 New Yorker profile as “The Book Eater.” (His first purchase, at age 21 in 1958, was a three-volume octavo edition of Audubon’s “Quadrupeds of North America.”) He is interviewed at home, practically walled in by books, and seems ineffably happy.

I confess that I am much more of a used book person than a rare book or first editions maven. It’s not just that the latter are prohibitively expensive. To take the most sky-high example, as we see in the documentary, the Leonardo da Vinci sketchbook known as the Hammer Codex sold at auction to Bill Gates for $30.8 million. A first edition of the first James Bond novel, “Casino Royale,” went for $150,000. If the text is what truly matters, spending many thousands of dollars on a first edition likely does little but enhance the coffers of the dealer. I wonder how many of these wealthy collectors actually read their books.

“The Booksellers” is more congenial, at least for me, when it showcases some of New York’s famed bookshops and their owners. The Argosy Book Store is a six-story emporium of wonders where I have spent quality time going bleary-eyed in the stacks. We hear from founder Louis Cohen’s three daughters, Judith Lowry, Naomi Hample, and Adina Cohen, who run the store. They make the vital point that the Argosy, established in 1925, survives today where so many others did not because the building is family-owned. The same is true of New York’s fabled Strand Book Store, which is run by its founder’s granddaughter. The Strand is in a section of the city once known as Book Row. Of the 48 stores in the area’s heyday, only the Strand survives.

As many of those interviewed can attest, the internet has greatly accelerated the demise of this world. Humorist Fran Lebowitz puts it succinctly: “You know what they used to call independent bookstores? Bookstores.”

So it was especially pleasing to hear from Rebecca Romney, a chipper, convincingly upbeat book dealer who often appears on “Pawn Stars.” She discounts the doomsday scenarios, and I agree. The movie opens by saying that books are not just an escape; they are a way of being fully human. I’m confident the basic urge they satisfy will never age.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

In central Europe, a stereotype of corruption breaks

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One stereotype of people in Europe’s former communist countries is that they still see personal connections and political favoritism as necessary for success in life. Merit and honesty come a distant second. This image was dealt a blow in the Feb. 29 elections in Slovakia. An anti-corruption party came out on top, riding a wave of demands for openness, equality, and rule of law in government.

Just by its name alone – Ordinary People and Independent Personalities – the party reflected a popular movement to build a culture of integrity. Its slogan, “Let’s beat the mafia together,” hinted at a shift toward breaking old patterns of corruption. “We want to show ... central Europe has not gone crazy,” says the party’s leader, Igor Matovič.

Mr. Matovič sees his party’s rise as a revival of the uprising 30 years ago that tumbled communism in Czechoslovakia. The revolution has not ended, Mr. Matovič told voters. Rather it “goes on inside each of us” who believe in its ideals.

As prime minister, he will need to build up institutions that are transparent and accountable. Corruption could soon be seen as the exception and not the rule in Slovakia.

In central Europe, a stereotype of corruption breaks

One stereotype of people in Europe’s former communist countries is that they still see personal connections and political favoritism as necessary for success in life. Merit and honesty come a distant second. This image was dealt a blow in the Feb. 29 parliamentary elections in Slovakia (which was once half of Czechoslovakia). An anti-corruption party came out on top, riding a wave of demands for openness, equality, and rule of law in government.

Just by its name alone – Ordinary People and Independent Personalities – the party reflected a popular movement to build a culture of integrity. Its slogan, “Let’s beat the mafia together,” hinted at a shift toward breaking old patterns of corruption. “We want to show ... central Europe has not gone crazy,” the party’s leader, Igor Matovič , told Reuters.

To build a majority in parliament and become prime minister, Mr. Matovič must still form a coalition with other parties. But the momentum for clean governance is well set. Two years ago, after the murder of an investigative journalist, mass protests forced a prime minister to resign and triggered a number of probes into official graft. Then last year, an anti-corruption activist, Zuzana Čaputová, was elected president.

While that position holds few powers, Ms. Čaputová has set a high example. “Maybe we thought that justice and fairness in politics were signs of weakness,” she told supporters in 2019. “Today, we see that they are actually our strengths.”

Mr. Matovič sees his party’s rise as a revival of the pro-democracy uprising 30 years ago, known as the Velvet Revolution, that tumbled communism in Czechoslovakia. Many of Slovakia’s leaders after 1989 were former communists who regarded seats of power as opportunities for self-enrichment. The revolution has not ended, Mr. Matovič told voters during the campaign. Rather it “goes on inside each of us” who believe in its ideals.

As prime minister, he will need to build up institutions that are transparent and accountable. Corruption could soon be seen as the exception and not the rule. And a lingering stereotype could be broken. Many in Slovakia have already made that choice.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

You can’t be robbed of what God has given you

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Andrea McCormick

Searching for a way forward after the funds she’d brought on a business trip abroad were stolen, a woman turned to God for help – and experienced God’s care in tangible ways.

You can’t be robbed of what God has given you

My husband and I were on a two-day business trip to the famous Panjiayuan market in Beijing to buy inventory for our Chinese antiques store. However, when we arrived at our hotel after navigating through a bustling crowd, I discovered that the funds we had brought for this purpose – several thousand dollars – had apparently been pickpocketed out of my closed purse.

I felt angry that the money had been stolen from me, but realized things would be even worse if we went home to New York empty-handed with nothing to sell, and at that time there was no way to transfer funds quickly from my bank account back home. Yet I needed to be able to start shopping at dawn the next day.

When faced with seemingly unsolvable situations, I have always found guidance, comfort, and courage by turning to the Bible. Calling on God to guide me has released me from the grip of panic and brought to light harmonious solutions.

Studying the Bible, along with the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, has taught me about God and the close relation we all have to God as His beloved children. In fact, we are made in God’s image, the spiritual expression of God’s goodness and love, which are the true substance of our existence and can never be lost.

This real substance, God’s substance, is not money; it is spiritual: a universal and eternal supply of goodness, expressed throughout creation. With this realization I forgave the person who had taken the money, knowing they could never take away my real substance, which comes from God. And I found comfort in the idea that everyone, including that individual, has the innate ability to find this true sense of substance for themselves, too.

This silenced my fear. In Proverbs it says, “Trust in the Lord with all thine heart; and lean not unto thine own understanding. In all thy ways acknowledge him, and he shall direct thy paths” (3:5, 6). As I prayed for divine wisdom to guide me, it came to me to go to the ATM in the hotel. I was well aware that I could do this, of course, but since our bank had a daily withdrawal limit that was only a fraction of the amount we needed, it hadn’t seemed like a viable solution to our pressing need.

But as I walked away from the machine after following up on this intuition and making the withdrawal, it came to me clearly to go back and try to make another withdrawal. To my surprise, I was able to, and not just once – several more times before it cut me off. I was overjoyed to have the funds I needed for the first shopping day, on which we found an abundance of good merchandise.

The next day, I was again able to withdraw more than expected. While the amount I was able to withdraw still totaled less than the amount that we had lost, I was grateful beyond words. It proved sufficient to purchase the inventory we needed.

But there was still the haunting thought, “This is great, but you have still lost several thousand dollars.” Inspired by my earlier prayers and what had transpired since, I felt a conviction that no one can take from any of us the goodness, joy, and supply that the Almighty God has given us. With that, the feeling of having been irreparably robbed of something left.

At that moment, I spotted a particular item that was a rare find, and I was able to get it for a reasonable price. I quickly called a customer back in the U.S. who collected these particular items and told him what I had found. Usually he took months to consider prospective purchases. But in this case he immediately said, “I’ll take it” – and his offer was for the same amount that had been taken from my purse.

It felt clear to me that this was no coincidence, but evidence of the restorative power of spiritual understanding indicated in a promise God makes to us all: “And I will restore to you the years that the locust hath eaten…. And ye shall … be satisfied, and praise the name of the Lord your God, that hath dealt wondrously with you” (Joel 2:25, 26).

A message of love

He does whatever a spider can

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when our Simon Montlake looks at how young Republicans – who see a need to take climate action – are charting a conservative path forward.