- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- A fresh ethos for capitalism? ‘Do the right thing.’

- When fighting bureaucracy means disbanding a pandemics office

- Why for pandemic parents, the bathroom is the only escape

- How John McCain and a cabin in the woods inspired an environmentalist

- An artist embraces her Iranian past and her American present

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Coronavirus may bump Olympic Games. Why it can’t dim their spirit.

Today’s stories include recalibrating capitalism, optimizing governmental (and parental) responses to pandemic, expanding the climate conversation, and reimagining protest art. First, a looming pivot for the summer games.

In a quiet act of optimism, the Olympic cauldron was lit Friday in Japan. But the 2020 summer games now appear poised to be bumped from a planned July start – perhaps to next year – as the world grapples with the coronavirus.

Truly, there are much greater logistical concerns just now. Still, the games are a recurring celebration of humankind’s oneness. That spirit is needed.

“Oneness” has a power that’s both secular and religious. Researchers have found it to be “related to values indicating a universal concern for the welfare of other people, as well as greater compassion for other people,” wrote psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman in a 2018 Scientific American story that’s now being recirculated.

Personal triumph, too, is unifying. Stories of individual Olympians can be globally galvanizing. Teams are national, but human achievement inspires – both within and across borders.

Here’s one preview. Hend Zaza is 11 years old. That’s young even for her sport, table tennis. With a shy smile and a ponytail that whips when she plays, she qualified for Tokyo with a win at a tournament this month in Jordan.

Consider that Hend’s homeland, Syria, has been locked in war for all but one year of her life. Consider how the ravages of another war, the one against the coronavirus, are also being overlaid on the grinding Syrian experience.

Waiting for the games – waiting however long – may mean deferring those tales of triumph until a collective fight is more in hand. But the pieces are in place. The stories are at the starting line.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Navigating uncertainty

A fresh ethos for capitalism? ‘Do the right thing.’

What happens when a system built on personal productivity and commercial connections meets a force that favors something very different? Ideally, an authentic shift in thought. Part 4 of a series.

Capitalism. It has spread to nearly every corner of the globe and no other economic system has been so effective at generating wealth. But today it is broken, failing to keep its promise of rising prosperity for all and rewarding a small minority with disproportionate riches.

That has provoked mutinies: Donald Trump’s election, the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union, riots in Chile and Lebanon. And it has provoked a rethink in the business world where, for the last half-century, the only metric for success has been the price of a company’s stock.

Now, more and more firms are saying it is time to put their purpose ahead of their profits, and to judge them also by their impact on their employees, customers, and local communities, as well as the environment.

The coronavirus – and efforts to slow its spread – will likely give this movement a huge boost. The value of mutual social obligations and shared responsibilities will be plain to see in everyone’s daily lives. Could that spell the end of capitalism as we know it – the neoliberal version – and usher in a kinder, gentler model?

A fresh ethos for capitalism? ‘Do the right thing.’

Verneuil-sur-Seine is not the sort of place you expect to find a revolution going on.

It’s a sleepy, nondescript suburb outside Paris, its streets hushed on a recent midweek morning. But in a cramped office in a converted apartment, an ebullient American mother of five and her French husband, a former auto executive, are busy reinventing capitalism.

Putting purpose before profits and ethics above everything, they are building a new sort of business. “We wanted to bring all our personal values into the company,” says Elizabeth Soubelet, a trained midwife. “Basic humanist values like respect for people and the planet.”

Ms. Soubelet and her husband Nicolas make Squiz, re-useable pouches for toddlers to suck applesauce from, which help parents cut down on plastic packaging waste. Theirs is a tiny company with ten employees (we’ll come back to them later), but they are by no means alone. Even titans of finance are on the same track as a new mood sweeps through businesses on both sides of the Atlantic, prompting CEOs to shift out of greed and into good.

And the global coronavirus pandemic has added compelling force to this movement. Suddenly, firms are expected to display compassion and promote the common interest; the way in which stressed companies treat their workers has become a loud and pressing public concern; in the United States, paid sick leave has become a political issue.

Battered by the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath, tainted by yawning disparities in income and opportunity, and focused tightly on the bottom line, “capitalism has been derailed,” says Paul Collier, an Oxford University economist and recent author of a surprise best-seller “The Future of Capitalism.”

“That is stirring new anxieties ... and mutinies” from Lebanon to Chile and from Brexit to President Donald Trump’s election, Professor Collier argues. “Potentially, capitalism is a wonderful system,” he adds. “But it doesn’t run on autopilot. It needs rules.”

After decades of laissez faire, he says, from business schools to boardrooms, “there’s a sea change going on.”

Time for a reset?

When the global businessman’s bible, the Financial Times, launches a campaign entitled “Capitalism: Time for a Reset” as it did last September, you know something is afoot.

In the developed countries where capitalism first flowered, but shifted away from its social obligations, its credibility today is badly tarnished. A worldwide poll earlier this year found that 56% of respondents thought the system was doing “more harm than good.”

And when the pro-free market think tank Legatum surveyed British public opinion in 2017, it found the notion of capitalism most often associated with greed, selfishness, and corruption – “the kind of ‘brand personality’ one would expect from an organization in acute reputational crisis,” its report pointed out.

The current model of unfettered neoliberalism is not keeping capitalism's promise of rising prosperity for all. From San Francisco to Stockholm, well-educated people living in a metropolis have done well from globalization and the prevailing ethos of individualism; less-educated provincials have seen far fewer benefits.

Labor’s slice of the global income pie has fallen from 54% to 39% since 1970, while the share going to wealthier individuals who own capital (such as stocks) has risen correspondingly. In the U.S., labor productivity has gone up by nearly 70% since 1979, but wages have risen by less than 12%.

Executive pay, meanwhile, has reached astronomical levels. In 2018, the 100 best paid U.S. CEOs earned 254 times the median pay of their companies’ employees, according to SEC filings.

Income inequalities “are going very fast in the wrong direction,” acknowledges Angel Gurria, the Mexican head of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the free market’s Paris-based think tank. “You can understand why everybody is so angry.”

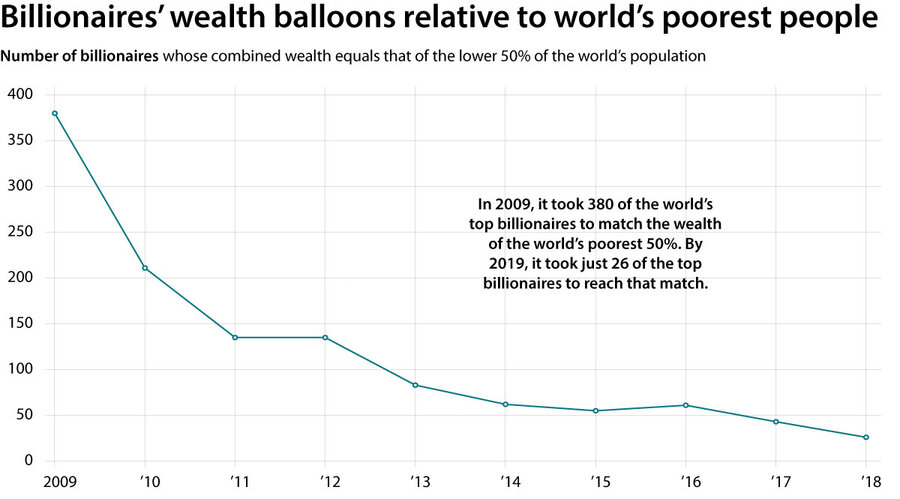

Oxfam

Behind the figures is the way capitalism has been practiced for the past half-century, since the free market economist Milton Friedman wrote in a celebrated New York Times article that “there is one and only one social responsibility of business ... to increase its profits.”

That dictum has dominated business thinking ever since, and it has made “shareholder value” the sole metric by which to judge a company’s success. CEOs have been obliged – by their boards and their investors – to prioritize quarterly earnings performance over all other criteria.

It wasn’t always like this; Henry Ford was keen on reminding people that “a business that makes nothing but money is a poor business.” But in the 1980s that mindset was swept aside by the outlook expressed in a sign hanging outside the trading room of Bear Sterns: “Let’s make nothing but money.”

It didn't help in the long run; Bear Sterns was the first bank to go under in the 2008 financial crisis.

Back in 1943, Johnson & Johnson published its business credo, stressing the firm’s responsibility to customers, employees and suppliers, and to local communities and the environment, before its duty to stockholders.

That approach was not common then, but it is stirring now in more and more boardrooms as business leaders carve out a new role for their companies. Last August 181 U.S. corporate members of the Business Roundtable, including the bosses of Apple, Walmart and PepsiCo, signed a pledge proclaiming their “fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders” and renouncing the doctrine of shareholder primacy.

And now the coronavirus pandemic has prompted people to scrutinize such companies’ behavior, and hold them to higher standards. Whole Foods, part of the Amazon empire, ran into a storm of public criticism recently when CEO John Mackey suggested that employees could donate their paid time-off hours to colleagues facing medical emergencies. This appeared to put some of the burden on Whole Foods’ staff, rather than the company.

Whole Foods and other firms have revised their paid time off policies to help employees cope with the pandemic.

“It’s these notions of purpose, trustworthiness, values, and culture that underpin a reconceptualization of business for the 21st century,” said Colin Mayer, the former dean of Oxford University’s Saïd Business School, at a recent seminar.

But what does that look like in real life?

Considering every angle

For Elizabeth Soubelet, it all began with shame. She was buying applesauce in 64-pouch family packs, she recalls, “and my kids were finishing them in like 14 seconds flat” and then throwing the aluminum-lined plastic containers away.

“I grew up in America in the '70s and '80s, in the heyday of trash,” she says. “I thought this was one thing that I could do better.”

She looked online, and found that all the reusable pouches came from China. That was no good; she didn’t like the idea of buying something that might be made in an exploitative sweatshop with poor environmental controls 5,000 miles away. Bad for the planet.

So she decided to make her own, and with her businessman husband set about creating a company with a simple mission: to help people reduce waste by using the company’s reusable pouches, playfully decorated with cuddly exotic animals.

But Squiz also has a broader vision of its purpose, Nicolas explains. “We want to build an organization that cares for people generally – our customers, our employees, our suppliers and the environment.”

That isn’t always easy.

So as to keep the company’s carbon footprint light, and to fulfill a social purpose, Squiz entrusts its packing and dispatch to a local nonprofit employing intellectually disabled people. Last year that meant some time-consuming and costly mix-ups, but Squiz sales administrator Virginie Bartoli, who spent weeks at the packing center sorting things out, discovered a silver lining.

“I didn’t know much about handicapped people, but I realized when I was working there that everyone has the right to work,” says Ms. Bartoli. “This job I do has made me more human, in some ways.”

Squiz insists that all its products’ components should be made and assembled in Europe, to European labor standards. “We take a stand,” says Sophie Amman, head of marketing and engagement. European workers are expensive, she knows, “but for us the bottom line is not the top priority.”

Still, what does all the care for the environment, the employee perks, the insistence that all materials be recyclable, do to the bottom line? Just how much does it raise the cost per unit?

“That’s a question that drives me crazy,” Elizabeth splutters. “What would you call the base cost? The China price? You can only tell the ‘real’ price when you add in the damage to peoples’ health and to the planet.”

Squiz has settled on a price of $5.50 for a pouch designed to be used at least 50 times. Sales have risen 40% year on year as the company’s reputation for fairness has spread.

That reputation has been cemented by Squiz’ certification as a “B Corporation” (the B stands for benefit) by an independent agency that has validated the company’s performance as a sustainable and ethical enterprise.

The 3,000-plus B Corps around the world, which include Ben and Jerry’s and the outdoor-gear manufacturer Patagonia, are legally obliged to consider the impact of corporate decisions on their workers, customers, suppliers, community and environment. They see themselves as the vanguard of “business as a force for good,” a better way of running capitalism that benefits a range of stakeholders, not just shareholders.

And there is no more vocal champion of “doing well by doing good” than Paul Polman.

Making capitalism sustainable

Mr. Polman, an energetic and talkative Dutchman, climbed the corporate ladder at Procter & Gamble for 27 years. But he made his name as the boss of a rival consumer goods giant, Unilever, the Anglo-Dutch firm that owns brands worldwide such as Hellmann’s, Dove, and Lipton tea.

It was there, until he left his job last year, that he pioneered the stakeholder model of multinational capitalism.

At first, he angered investors when he took over in 2009 by refusing to offer the traditional quarterly profit forecasts on which financial analysts rely, and insisting on taking a longer-term view of his company’s performance. Unilever shares fell 10%.

Then Mr. Polman alarmed them even more by devoting money and attention to something he called the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan, which involved all sorts of projects that seemed harebrained at the time.

He pledged Unilever would buy all of its agricultural raw materials from sustainable sources by 2020. (In fact, it has managed to hit 70%.) He announced ambitious personal hygiene targets in developing countries, launching hand-washing programs for kids and building 30 million toilets.

“Each Unilever brand had a social mission and a purpose,” Polman recalls.

That built the trust that is especially critical to consumer product companies, but which can decide the fate of any company. And a global study earlier this year found that ethical issues such as integrity are three times more important to people than competence when it comes to trusting a company.

For Unilever, all this paid off. The company yielded 290% shareholder return over Mr. Polman’s decade at the helm, he says proudly. “The development agenda is a business agenda,” he insists. “It doesn’t have to be a tradeoff.”

The financial markets are still somewhat hesitant, he says, “but investors are starting to wake up.”

BlackRock, the largest asset management company in the world, handling $7 trillion, is a case in point.

In his 2019 annual letter to the heads of the companies that BlackRock invests in, CEO Larry Fink urged them to identify and express their companies’ purpose. This year he announced that BlackRock’s actively managed funds will no longer invest in companies that derive more than 25% of their revenue from thermal coal.

“We’ll walk away from businesses whose purpose we don’t believe is particularly compelling or will ensure that the company will be around for a long time,” explains BlackRock spokesman Ryan O’Keeffe.

In the same vein, the head of the world’s largest asset owner, the Japanese government’s pension investment fund, warned in an open letter earlier this month that “companies that seek to maximize corporate revenue without considering their impacts on other stakeholders ... are not attractive investment targets for us.”

Such pronouncements have drawn accusations of “purpose washing”; and activists are still waiting to see any change in behavior by any of the companies that signed on last year to the Business Roundtable’s declaration of commitment to “all of our stakeholders.”

“That was just a statement,” says Andrew Winston, who advises businesses on sustainability. “It didn’t actually commit the companies to much of anything and it remains to be seen how they apply it. But it was symbolically important and it has started a debate.”

Now they must put their money where their mouth is, says Mr. Polman. And he doesn’t think they should be afraid to forge a new path for capitalism. The figures seem to back him up: In the current stock market rout, ESG funds (focusing on environmental, social, and governance investing) have outperformed their peers.

“Ten years ago, I did what I did as an act of faith,” Mr. Polman says. “But now there are quite a lot of hard facts showing that purpose-driven, long-term, multi-stakeholder firms which respect people and the planet see better business performance.

“Companies that do all this will be ready for the future. The rest will turn out to be dinosaurs.”

Read the entire Navigating Uncertainty series.

Oxfam

When fighting bureaucracy means disbanding a pandemics office

“More bureaucracy!” is perhaps not the best rallying cry. But what if streamlining means hindering work on an essential set of tasks? The current crisis highlights both sides of the issue.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

For President Donald Trump, the National Security Council (NSC) must have seemed like an ideal place to make good on his pledge to drain the swamp.

Founded more than 70 years ago as an advisory board for the president on matters of national security, it has grown into a bureaucracy of its own – often pulled this way and that by the agendas of those assigned to it.

Among the groups to be disbanded: a pandemics office founded by President Barack Obama, now folded into a broader directorate that works on nuclear proliferation and terrorism. The question today, of course, is: Could it have made any difference? Experts point to one area, in particular, where it could have been helpful. It had expertise to coordinate across different agencies, especially in the early stages of the outbreak.

Without such an office, “can you invent it as a posse at the last minute?” asks a member of President George W. Bush’s NSC. “Yes. But would it be more effective if it’s already on the spot? Yes. And it could act faster.”

When fighting bureaucracy means disbanding a pandemics office

When PBS journalist Yamiche Alcindor recently asked President Donald Trump about his decision to disband the National Security Council’s office for pandemics, Mr. Trump said the question was “nasty.”

But it pointed to a fundamental tension in Mr. Trump’s view of government. Can he “streamline” a government that he feels has become too bloated while maintaining its ability to act effectively?

The administration sees this as essential work, returning the NSC to its core function as an advisory body of several executive branch secretaries serving the president – instead of a growing bureaucracy pursuing a variety of agendas.

[Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.]

But some former NSC officers from both Republican and Democratic administrations worry that Mr. Trump has cut into the meat of the NSC. The disbanding of the pandemics office in 2018 under John Bolton, which was then folded into a broader directorate on issues such as nuclear proliferation and terrorism, shows the costs of such downsizing, they say.

“We live in an era of recurrent crises of this kind [like coronavirus] that come with greater velocity, greater impact, and cost, and we need a facility within ... the White House that has the authority to see around corners, see things early, act very quickly, and bring about accountability and coordination of the U.S. response,” says Stephen Morrison, director of the Global Health Policy Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “That has been missing” with the disbanding of the White House pandemics office.

“Some of the sluggishness and confusion that we have seen bedevil this effort since the very beginning ... [is connected to the] absence of effective structures within the White House itself,” he adds.

That’s because a pandemics office could have filled a vital role from the first moments of the crisis – coordination. Organizations had to spend valuable time getting on the same page.

“In a crisis like this you don’t go to HHS [Health and Human Services] and ask them to manage it. You go to the White House where presumably you have the expertise developed to work across all the relevant agencies,” says Peter Feaver, who was a strategic planner for President George W. Bush’s NSC.

“Can you invent it as a posse at the last minute? Yes,” he adds, “But would it be more effective if it’s already on the spot? Yes. And it could act faster.”

Moreover, when the pandemics group was moved into a larger directorate, it lost expertise. “Amid a pandemic, we should prefer a team with sufficient seniority to guarantee access and trust,” says Loren DeJonge Schulman, the NSC’s director of defense policy during President Barack Obama’s first term. “These are not matters you want to learn on the job in crisis.”

The National Institutes of Health leader who has become a fixture at daily White House coronavirus briefings acknowledges the team’s absence is felt. “It would be nice if the office was still there,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told Congress March 11.

What is the NSC for?

To Mr. Trump, however, the NSC had become something that was never intended. National security adviser Robert O’Brien said recently that the NSC had “ballooned” to 250 staff members under President Obama. Mr. O’Brien reduced it to 175 when he took his job, and it is now at 110, he added.

“The NSC is not there to re-create the State Department or the Pentagon” within the White House, he said.

But in shrinking, the NSC has become too much of a “yes, sir” body that tells the president what he wants to hear, says Ms. DeJonge Schulman, who is now a national security expert at the Center for a New American Security in Washington.

“The NSC staff is not there to implement the president’s every desire, but to make sure he has the best options, evaluation or risk and cost, and perspective on agency views,” she adds.

Some also suspect that the downsizing aims to reduce the number of career officials – the “deep state” – seeing them not as a source of expertise but as a potential den of disloyalty.

“It’s just not the case that the NSC O’Brien took over was too big, especially given the complexity and variety of issues the president has to deal with,” says Mr. Feaver, who is now a public policy professor at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. “What is the case is that Trump didn’t think he needed any NSC staff.”

Mr. Trump’s impeachment was largely launched by a whistleblower assigned to the White House from an outside agency – the CIA. The president’s preoccupation with “the agencies” suggests to Mr. Feaver that the streamlining “is fueled by the same mindset that gives him concern about the so-called deep state, but it reflects a high level of insecurity and a unilateral approach to loyalty.”

Golden days

For his part, Mr. O’Brien says he is trying to return the NSC to the model created by the legendary Brent Scowcroft under President George H.W. Bush – a focus on implementing the president’s policies.

“If you can’t get on board with [the president], you’re probably better off back in your agency or ... running for Congress,” he told a crowd at the Heritage Foundation to laughter.

But others have a different view of Mr. Scowcroft’s legacy. Under Mr. Obama, National security adviser Susan Rice “believed the NSC staff should focus on coordinating policy and advising the president, not implementation that should go to agencies – a fundamentally Scowcroftian view,” says Ms. DeJonge Schulman.

Ms. Rice, too, undertook a “right-sizing effort,” worried that the NSC had begun taking over agency duties. But the NSC’s key role was “making sure agency perspectives get a fair hearing and fair evaluation with the president,” Ms. DeJonge Schulman adds.

Beyond that, there are limits to a model from three decades ago.

“Brent Scowcroft didn’t need an office on cyber, but it’s a necessity now,” says Mr. Feaver. “In the same way, the judgment was made at some point that pandemics were going to become a bigger problem in our current time and so necessitated more high-level attention at the White House.”

To him, “that view has been borne out.”

[Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.]

Essay

Why for pandemic parents, the bathroom is the only escape

Many who work outside the home have at least temporarily lost a daytime divide between career concerns and active parenting. If that describes you, then you’ll empathize with this essayist in Paris.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

“Mama! Pee-pee! Mamaaa!”

It’s the fourth day of lockdown and my 3-year-old daughter has once again woken me up at 6:20 a.m. Next, my 18-month-old coughs herself awake.

I love my children. Of course I do. But ever since French President Emmanuel Macron announced that school was canceled and we would be allowed outside only for groceries or medical visits, I have been filled with a terror I have never known. What the heck am I going to do with my kids for the next however-many days?

Thank goodness for the endless supply of internet memes, most of which involve some version of child confinement while parents work. See, it’s not enough that we have to find ways to entertain and educate our little demons during this trying time, but we also have to keep our jobs.

While I hide out in the bathroom typing, I know that in many ways parents of older children have it harder. How to explain the unfathomable state of the world? Are we creating a whole generation of germ freaks? All I can do is have faith life will return to normal someday – and that we’ll still like each other in the end.

Why for pandemic parents, the bathroom is the only escape

It’s 6:20 in the morning. The fourth full day under lockdown. While some Parisians will be enjoying a leisurely lie-in – working from home or on paid leave – I am awakened by my 3-year-old daughter, whose calls increase in intensity.

“Mama! Mama! Pee-pee! Colette!”

Minutes later, my 18-month old starts coughing herself awake. I’m not so much worried she has the coronavirus (although who knows) as I am annoyed. Once again, I have approximately the next 12-15 hours to spend with my kids.

I love my children. Of course I do. But ever since French President Emmanuel Macron announced that schools in France would be closed indefinitely due to the coronavirus pandemic, and then – days later – that we would be allowed out of our homes only for groceries or medical visits, I have been filled with a terror I have never known. What the heck am I going to do with my kids for the next 14 to however-many days?

Under normal circumstances, my partner and I aim to get our girls out of our small two-bedroom apartment by 9 a.m. – school day or not – lest they start climbing the walls/tearing up the place. Now, it would seem, that is all there is to do.

Editor’s note: As a public service, we’ve removed the paywall for all our coronavirus coverage. It’s free.

Luckily, parents in France can look to the experience of those in Asia who’ve already suffered through months of lockdown to guide us, or take advice from Spaniards and Italians who are living on a surreal future plane, days or weeks ahead in their lives in confinement: Keep a schedule. Create quiet time. Get some fresh air every day.

The first few days chez moi were filled with New Year’s resolution-like euphoria. I unearthed a giant piece of cardboard from the back of the closet and created a daily “learning board,” ready to embark on my new career as homeschool teacher. There were stickers for each day of the week, numbers, and letters, and I printed a stack of toddler activity sheets to boot. It was all going to be okay.

By day three, the stickers were still in the same place on the learning board as the day before and papers were strewn across the living room. The girls were still in their pajamas at 10 a.m. And were those animal stickers lining the toilet seat?

I can see that my twice-a-week iPad limit is going out the window. My 3-year-old is already asking for Peppa Pig every night before dinner and I am too exhausted to say no.

Thank goodness for the endless supply of internet memes, which range from the silly to the downright dire. Most involve some version of child imprisonment while parents work, be it strapping them down in front of the TV or quite literally locking them in a cage.

You see, it’s not enough that we have to find ways to entertain and educate our little demons during this trying time, but we also have to find a way to keep our jobs.

Seeing as how the bathroom is the last bastion of privacy (when the kids are not trying to beat down the door), I expect that I, like many French parents, will be using this tiny haven to answer work emails, make calls, and write – or at least respond in peace to the scores of WhatsApp messages from other parents in lockdown misery that flood my phone.

These days, WhatsApp and FaceTime are not just diversions; they’re life savers, especially for families with older kids. But apart from group phone chats among friends and loved ones, they offer no solution for tweens with serious energy to burn. In France at least, we’re allowed short periods of outdoor exercise every day. Spaniards can take their dogs for a walk, but not their children.

“It’s really complicated,” says Ruth de Andres, my partner’s cousin and mother of an 8-year-old girl and 13-year-old boy in León, Spain. “What do you do with all this energy? My daughter loves to dance but after a certain point, she gets bored. Then she’ll play her viola but after 10 minutes she gets tired. It’s been very hard … I’m exhausted.”

But parents with older children have to do more than just keep them physically under control; they also have to make sure their brains don’t turn to mush.

In France, the government has promised to provide online classes, but the platforms crashed the first day. Many high school seniors are stressing about how they’ll pass the end-of-year exams in subjects like math and biology when they barely understand them in the classroom. For children with illiterate parents, the challenges are compounded.

In a way, I have it easy. My girls risk losing a bit of French while they’re stuck at home with two nonnative speakers, but I’m not worried about them falling behind in reading or math, as I would if they were older.

And even if entertaining two toddlers is truly energy-sucking and testing the little patience I possess, it doesn’t compare to the emotional challenges of parenting older children in lockdown. My girls simply think they’re on extended vacation and are thrilled they get to spend 24/7 with Mom and Dad.

And even though some of our best efforts – like removing the pacifier or getting my older daughter to fall asleep on her own – are likely to fall by the wayside as our notions of routine get scrambled, I know they’ll be OK.

I don’t have to explain that a deadly virus is the reason they can’t see their grandparents or friends, or need to answer existential questions about the unfathomable state of the world. My daughter’s “Why” game is even starting to seem pretty OK right about now – except when she asks why half the people in the street are wearing surgical masks.

If what has happened in Asia is any indication, we could be in this situation for a while. All I can do is have faith that one day things will return to normal. That my girls will be able to touch the doorknobs of our apartment complex, hug their friends with wild abandon, or even grab other kids’ toys in the neighborhood sandbox – without me scrambling for the hand sanitizer.

I hope we’ll all look back on this strange time in humanity’s history and realize it brought us closer – communities and families. I know I’m lucky that I actually like my family. Many kids in Europe’s lockdown will face abuse, hunger, or mental health issues. It’s a good reminder, during these tough weeks ahead, that we have to be kind to one another in order to survive.

In the meantime, though, thank goodness for Peppa Pig.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Profile

How John McCain and a cabin in the woods inspired an environmentalist

Progressive young voices of warning have been raised on climate change. We profile a young conservative who wants others like him to know that they, too, have a role in the conversation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Hallie Golden Contributor

Remember that Republican President Theodore Roosevelt established national parks, and the Environmental Protection Agency was created under Richard Nixon? While the GOP is largely seen as at odds with environmentalism, that hasn’t always been the case. Benji Backer, college senior and present-day conservative environmentalist, is working to bring like-minded young people back into the conservation discussion. He’s been speaking across the country as the founder and president of the American Conservation Coalition, which has members on 200 college campuses.

Mr. Backer disagrees with activist Greta Thunberg’s darker view of climate change because he thinks it could turn people away from the fight. But he believes the left and right can work together to tackle the crisis. “We all have our own roles to get people engaged in this issue in a way they haven’t been before,” says Mr. Backer. “And whatever gets us to the final results of climate action is all that matters.”

How John McCain and a cabin in the woods inspired an environmentalist

Benji Backer stood in front of 100 college Republicans at the University of Central Florida and asked for raised hands from those who consider themselves environmentalists. Everyone held up an arm.

Then came the follow-up question at the College Republican State Convention last month: “Do you guys know what the conservative environmental platform is?” The hands went down.

Mr. Backer went on to talk about the role of markets and capitalism in a greener future, bringing local hunting and fishing communities into the conversation, and looking to innovation and technology for environmental solutions.

He is giving these talks across the United States as the founder and president of the American Conservation Coalition (ACC), a nonprofit full of young people working to bring conservatives back into the conservation discussion, so that the left and right can work together to tackle the climate crisis.

Founded in 2017, the group has spread to 200 college campuses. By next year they hope to have 10,000 members. The ACC helps people connect with elected officials to advocate for bills such as the Restore Our Parks Act, but also focuses on teaching the public how conservatives and conservation fit together.

“We’re educating conservatives, liberals, whoever wants to listen, on how market-based, limited government policies are better for the environment; and how if you believe in markets or technology or conservative values … you can also be an environmentalist,” says Mr. Backer, a business marketing senior at the University of Washington in Seattle.

While the GOP is largely seen as at odds with environmentalism, that hasn’t always been the case, says Toddi Steelman, Stanback dean of Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment. After Theodore Roosevelt created national parks and forests, Richard Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency and the Endangered Species Act, for example.

“I think people … understand that the protection of water, air, and concern for our health is good not just for our children, but if we do it well, it’s good for business,” says Dr. Steelman. “It creates sustainability in terms of what we want to achieve broadly writ – economically, socially, and environmentally.”

Ms. Steelman says Ronald Reagan’s administration shifted to a focus on deregulation to boost business and industry after the recessions of the 1970s. “That rhetoric has just been adopted by the Republican Party since then as part of the party line,” says Ms. Steelman.

Ten-year-old debate fan

For Mr. Backer, a televised debate between Barack Obama and John McCain in 2008 initiated his activism as a conservative, if not Republican, since he eschews the labels of political parties for himself. But he’s had a passion for the environment for at least as long. Growing up in Wisconsin, he enjoyed spending weekends in the woods around the cabin his grandparents built. As he got older, he realized that these two passions “were not correlating at all.” By 2016, Mr. Backer realized there were others just like him, and with a team he launched the ACC.

Mr. Backer says he’s received pushback from conservatives who see environmental efforts as a “trojan horse,” and from liberals who think the ACC is not doing enough. But within the last year, he’s noticed something of a shift.

“More of the left of center people are realizing that you need both sides. And more people on the right of center side are realizing that you can look at these issues within a mindset that isn’t completely anti-conservative,” says Mr. Backer.

An ACC representative at the University of Missouri in Columbia, Dalton Archer, adds, “I am starting to see both locally and across the country student-age young Republicans talking a lot more about environmental issues than you would originally have thought.”

Mitch McConnell and Greta Thunberg

Recently in Washington, D.C., Mr. Backer met with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s top policy adviser, and in the past had also met with President Donald Trump’s staff, something he called a “work in progress.”

“I don’t believe that our future has been stolen from us,” he says. “I believe that we have time to fix climate change. I believe that’s what the science says.”

That’s where he disagrees with activist Greta Thunberg. The pair met in November when they both testified in Congress. Mr. Backer remarked on her ability to inspire, but with a more alarmist approach that could turn people away from the fight.

“At the end of the day you need somebody like her and you need somebody like me and you need every sort of person in the movement for this to get tackled,” he says. “We all have our own roles to get people engaged in this issue in a way they haven’t been before, and whatever gets us to the final results of climate action is all that matters.”

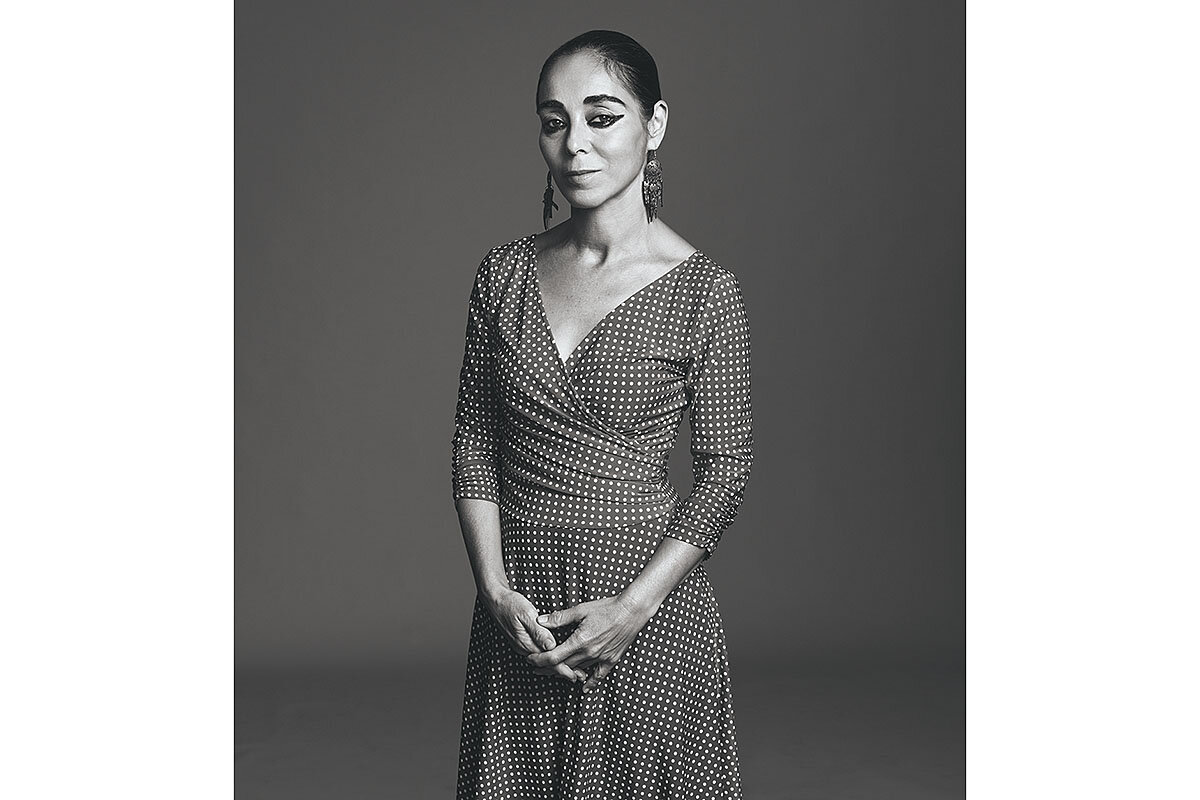

An artist embraces her Iranian past and her American present

Political art can be blatantly confrontational. It can also be more gently persuasive. Meet an Iranian exile in the U.S. whose most treasured offering is insight.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Carol Strickland Correspondent

Shirin Neshat’s artistic epiphany began when she traveled back to Iran in 1990 after living in the United States for 15 years. “It was quite traumatic,” she says. The Islamic Revolution in 1979 and the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, which had separated her from her family, had altered Iranian society.

“The country had really transformed from what I recalled the last time I was there ... [when it] was modern and very liberal,” she says. Ms. Neshat was shocked to discover all the women encased head-to-toe in black. The country seemed to have traveled backward in time from a colorful, secular society to a conservative theocracy.

On the trip, she encountered images of Iranian women glorified by the state as martyrs who’d fought against Iraqi invaders. She found it “terrifying but also interesting and exhilarating,” she says. Even while these female warriors’ civic rights were curtailed, they could still bear arms. They were both militant and silenced. The paradox fascinated her.

When she discovered that Iranian women had lost their voices, Ms. Neshat found hers.

An artist embraces her Iranian past and her American present

Iranian American artist Shirin Neshat doesn’t think political art should be obvious and preachy.

“It’s wrong to tell people what’s right and what’s wrong. But it is possible to make art that makes people think about important issues in a whole new way and have new insights,” she says.

Over a 30-year career, Ms. Neshat has mined her feelings of dislocation as an exile. She’s created haunting photographic portraits, surrealistic video installations, and atmospheric short films with collaborators such as actress Natalie Portman and composer Philip Glass. In 2018, she was commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery in London to create a portrait of activist Malala Yousafzai. She’s won numerous international art and film prizes.

A retrospective of her work, “Shirin Neshat: I Will Greet the Sun Again,” recently ended its run at The Broad in Los Angeles and is expected to travel to the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, in Texas, early next year. It traces Ms. Neshat’s evolution from depicting Middle Eastern subjects to her latest projects focusing on her adopted country. (She became a U.S. citizen in 1986.)

For her, the struggle is creating a balance between “being politically conscious – tackling the real issues we’re facing – and allowing multiple interpretations so people can think about it and take away whatever they wish.”

Her work erects bridges rather than walls, according to Farzaneh Milani, chairwoman of the department of Middle Eastern and South Asian languages and cultures at the University of Virginia. Ms. Neshat’s poetic and conceptual art is like “a magic carpet that takes us to unfamiliar territories,” she says, freeing us from “our mental, intellectual, and political ghettos.”

In “Land of Dreams” from 2019, the artist combines photographic portraits of people in New Mexico – immigrants, Native Americans, ordinary people from all walks of life – with videos that elicit their dreams and fears. The project attempts to create a portrait of America at this moment, in the middle of the hostile rhetoric toward immigrants and asylum-seekers. Her message, she says, “is to emphasize the diversity in this country between multiracial ethnicities and the shared humanity that defines America.” For Ms. Neshat, who is proud to be both an American and an immigrant, “the American identity is this multiplicity and hybridity.”

Her artistic epiphany began when she traveled back to Iran in 1990 after living in the United States for 15 years. “It was quite traumatic,” she says. The Islamic Revolution in 1979 and the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, which had separated her from her family, had altered Iranian society.

“The country had really transformed from what I recalled the last time I was there under the shah [Mohammad Reza Pahlavi], which was modern and very liberal,” she says. Ms. Neshat was shocked to discover all the women veiled, encased head-to-toe in black. The country seemed to have traveled backward in time from a colorful, secular society to a conservative theocracy.

On the trip, she encountered images of Iranian women glorified by the state as martyrs who’d fought against Iraqi invaders. She found it “terrifying but also interesting and exhilarating,” she says. Even while these female warriors’ civic rights were curtailed, they could still bear arms. They were both militant and silenced. The paradox fascinated her.

When she discovered that Iranian women had lost their voices, Ms. Neshat found hers.

Until the trip to Iran, she had been living in New York, co-directing a nonprofit experimental space called Storefront for Art and Architecture with her then husband, Kyong Park, and raising a son. She had pursued art studies at the University of California, Berkeley, but she was not then producing art.

“At the time, I didn’t have an art career,” she recalls. “I didn’t have an audience in mind. Everything just grew very organically. The revolution was the core of my subject, understanding how the country became Islamicized, and then the subject of martyrdom.”

She began sketching hands and feet, and writing in Farsi script on top of them. Eventually, she thought, why not just use photography? Later, she moved on to photographs of Iranian women, who are shown covered except for their eyes and sometimes their faces. Some carry weapons. They look unblinkingly out at the viewer. The artist inscribes the faces in the photographs with decorative flourishes and the words of contemporary female Iranian poets. Ms. Neshat gives words to what the women have experienced, depicting their dignity as well as their defiance.

The series of photographic portraits, “Women of Allah,” brought her international attention.

Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the nonprofit Center for Human Rights in Iran, says that “Women of Allah” “is about how women during the war were propelled into roles they never had before.” The series effectively overturns stereotypes, especially that of “the subservient, obedient housewife or woman in Iran,” says Abbas Milani, director of the Hamid and Christina Moghadam Program in Iranian Studies at Stanford University.

Ms. Neshat uses art as a tool to inform, provoke, and perhaps even liberate and heal.

She provides a fresh perspective on the places where she’s worked in addition to Iran, such as Turkey, Morocco, Egypt, Azerbaijan, Mexico, and the U.S. Seeing the world through her eyes requires a revision of assumptions.

“Through difficult encounters or interacting with something you don’t understand, if you allow yourself to take a crack at understanding it, art can bring an incremental change in perspective,” says Ed Schad, who curated Ms. Neshat’s retrospective at The Broad.

Ms. Neshat’s art embodies an immersive, expansive, and transnational view of humanity.

“I cherish my relationship to American culture,” the artist says. “I live a double life, a life between East and West, and Iran and America, since I was 17. You maintain something of your past, but then you adapt to where you are living.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Self-isolating as a gift, not a grind

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The World Health Organization has advised people to manage their mental well-being as much as their physical health, especially those hunkered down at home with feelings of fear, loneliness, and sadness. The agency recommends people be empathetic toward those with COVID-19, seek accurate information about the crisis, and find safe ways to help others in isolation.

In other words, one’s home is now both a sanctuary from the virus and a place to rethink the principles that ought to govern home life. Are we seeking out truthful sources of news? How can we better calm a friend with loving assurance? What new ways of expressing life might be possible during the still silence of self-isolation?

WHO’s call is meant as a challenge. In the sanctuary of one’s home, some of the old ways of thinking about relationships, skills, and interests must be rethought. The isolation can be a gift, not a grind, especially as a new inner life leads to bettering oneself as well as the lives of others.

Self-isolating as a gift, not a grind

As it leads the global battle against the coronavirus, the World Health Organization has advised people to manage their mental well-being as much as their physical health. The advice is especially true for the hundreds of millions of people who have self-isolated during the pandemic. WHO suggests engaging in healthy activities to relax, eating well, and keeping regular sleep routines.

Yet WHO also knows such advice may not be enough for those people hunkered down at home with feelings of fear, loneliness, and sadness. The agency also recommends people be empathetic toward those with COVID-19, seek accurate information about the crisis, and find safe ways to help others in isolation.

“Assisting others in their time of need can benefit the person receiving support as well as the helper,” the agency stated.

In other words, one’s home is now both a sanctuary from the virus and a place to rethink the principles that ought to govern home life. Are we seeking out truthful sources of news? How can we better calm a friend with loving assurance? What new ways of expressing life might be possible during the still silence of self-isolation?

For many, the pandemic is reshuffling the notion of home as a sanctuary, or a sheltering space that allows one to anchor one’s thoughts and values. People are redefining their cords of attachment in new ways. Instead of going to religious services in person, they are worshipping online. Instead of going to parties, weddings, sporting events, or even funerals, they are holding digital gatherings.

Adjusting to a new life of quarantine can have its rewards. “All of this can be overwhelming, but it doesn’t need to be,” wrote the leaders of the United Methodist Church in Simsbury, Connecticut, in a message to congregants. “This can be a time where we can deepen our prayer life, increase our meditation time and work to expand the peace of God around us as those near and dear grapple with heightened anxiety.”

WHO’s call for people to maintain their mental well-being is meant as a challenge. In the sanctuary of one’s home, some of the old ways of thinking about relationships, skills, and interests must be rethought. The isolation can be a gift, not a grind, especially as a new inner life leads to bettering oneself as well as the lives of others.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Gathering spiritually, calming pandemic fears

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Chet Manchester

Around the world, public gatherings have been restricted as part of efforts to contain the coronavirus. But as one man found when he fell ill in a remote area some years ago, even when we’re all alone, there’s another kind of “gathering” we can participate in – one that brings safety and healing.

Gathering spiritually, calming pandemic fears

There’s a growing list of restrictions around gathering publicly right now, and that’s understandable. And it’s natural and right to support efforts to contain the coronavirus.

But there’s another kind of gathering that’s essential to healing fear, especially during a pandemic. Christ Jesus described it this way: “Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them” (Matthew 18:20).

This kind of gathering can take place even when we can’t meet in person. It’s a coming together in thought, an openness to the spiritual view of life that Jesus taught. And it’s one of the most practical, health-giving things we can do.

Collective prayer is a powerful way to come together, and billions on our planet unite in a simple prayer Jesus taught: the Lord’s Prayer. Mary Baker Eddy, who founded Christian Science, once spoke of the Lord’s Prayer as a “bond of unity” and a “point of convergence” for all Christians (see “Pulpit and Press,” p. 22). Its ideas are universally true, a prayer that people of all backgrounds can “gather around.”

In her book about spiritual healing, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Eddy gives a spiritual interpretation of the Lord’s Prayer. It begins, “Our Father which art in heaven, Our Father-Mother God, all-harmonious” (p. 16).

I’ve experienced healing in my life again and again by treasuring that idea of one universal Father-Mother God governing all creation in total harmony. Once, while in a remote part of Africa, I felt a fever drain from my body as the sense of our Father impelled me to include everyone around me in my prayer, even the mosquitoes. My prayers affirmed that we are all part of one all-harmonious, spiritual creation. As it says in the Bible, “God blessed them” (Genesis 1:22, 28). Everything our good and loving God creates is made to bless, not to harm. So the divine creation certainly doesn’t include or cause disease. This spiritual outlook enabled Jesus to heal, and it’s at the heart of his prayer.

As I prayed in this way, the fear gripping me was replaced by what felt like a flood of love, God’s love, for me and everything around me, and the fever just melted away. I was well. (You can read more about this healing here.)

That experience and many others have given me tangible proof of the healing power of prayer. I’ve also glimpsed what it really means to gather “in my name” as Jesus taught. It’s about gathering not around a human personality but around the universal idea of Christ, or Truth, that Jesus lived and taught. Christ means anointed or divinely inspired. I like to think of it as our divine creator’s “communication link” to everyone, everywhere.

Opening our hearts to the Christ enlightens our whole way of thinking, giving us a spiritual view of life and health as governed by God, rather than a battle for survival in a dangerous world. Christ is an irresistible power bringing us all together, enlightening our perspective of everything, helping us see our common bond as children of one infinite God. This is what makes gathering in prayer so powerful. And so healing!

A message of love

Under one sky

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow. We’ll take a deeper run at the amplified challenges suddenly facing the sandwich generation – those taking care of their elders as well as their offspring.