- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- How coronavirus threat could ease another: nuclear proliferation

- States band together to take next step against coronavirus

- Jobless benefits are a lifeline – if the unemployed can get access

- Hope for student borrowers: Settlement requires administration move faster

- A new vision for farming: Chickens, sheep, and ... solar panels

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What true community can bring to the coronavirus fight

Today we explore nuclear weapons chess, governors grouping on COVID-19, a ground-level take on the unemployment spike, student-loan justice, and where solar meets farming. First, a look at some lessons in communitarianism.

The term “intentional community” could arguably describe any human settlement where inhabitants willingly cluster. A more specific definition applies to groups with shared values and resources (child-minding might be an eagerly sought example) as well as shared spaces.

At a time when perspectives on what constitutes “common good” vary wildly – including at all levels of government – it’s worth looking at communities that bring real intensity to their intentionality.

When I reached Cynthia Tina, a co-director at the Foundation for Intentional Community, she had just finished a two-hour call with the Global Ecovillage Network. FIC promotes cooperative, healthy, sustainable living.

Ms. Tina, a self-described former eco-nomad, ran me through the difference between consensus-based decision-making on community actions and a consent-based process that she sees as a rising alternative.

“The idea is not to get everyone to agree unanimously,” she says, “but to make sure no one has an objection.” Objections to deviations from agreed-upon values are taken seriously. Experimental approaches – to any issue – face a trial period. “We have a saying,” she says. “Good enough to try, safe enough for now.”

Getting to effective unity requires respect, and the suspension of personal or political agendas. A social challenge like the coronavirus – one that underscores existing social dysfunction – calls for making community the top priority at the global, national, and state levels. (And, of course, locally.)

“Community, at its core, really means listening to each other,” Ms. Tina says, “practicing deep listening, and seeking to understand others’ views.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How coronavirus threat could ease another: nuclear proliferation

Nuclear weapons are, for the moment, a global issue that’s decidedly overshadowed. Our writer breaks down what might have happened at a now-delayed conference, and how the delay may have opened room for thought to shift.

Every five years, member states gather to review the half-century-old Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, or NPT. The conference was to have been held at the United Nations in New York for a month beginning next week, and predictions of a rancorous and divisive review were flying high.

Enter the coronavirus pandemic, forcing U.N. officials to delay the gathering of hundreds of diplomats and officials until 2021. The postponement is increasingly being viewed as an opportunity.

Among the reasons for the dour predictions: the world’s nuclear weapons states, including the United States, Russia, and China, were in for a drubbing from nonnuclear states for undoing disarmament accords and modernizing and expanding nuclear arsenals, experts said.

“I continue to believe that the coronavirus pandemic is providing an opportunity for leaders to come together around international institutions and agreements and to restate commitments to international cooperation,” says Rose Gottemoeller, a former undersecretary of state for arms control and international security. “The NPT regime is no different,” she adds, “so I believe we’ll see [treaty signatories] … coming together around the position that ‘this is a good treaty, let’s recommit to it and strengthen it going forward.’”

How coronavirus threat could ease another: nuclear proliferation

With the world caught in the throes of the coronavirus pandemic, the global threat that much of the international community once worried about most – the proliferation of nuclear weapons and the risk of a cataclysmic nuclear winter – has largely vanished from public thought.

The issue has quite literally retreated from the international stage – the pandemic having forced the postponement of the every-five-years review conference of the half-century-old Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, or NPT.

The gathering of hundreds of diplomats and nuclear-issues officials from the NPT’s 191 member states was to have been held at the United Nations in New York for a month beginning next week. U.N. officials have delayed the conference until 2021.

Yet while predictions of a rancorous and divisive NPT review conference were flying high earlier this year, the postponement is increasingly being viewed as an opportunity.

Among other reasons for the dour predictions: The world’s nuclear weapons states, including the United States, Russia, and China, were in for a drubbing from non-nuclear states for undoing disarmament accords and modernizing and expanding nuclear arsenals, experts said.

For some experts in nuclear issues, the year ahead now opens the door to serious discussion of ways of fortifying the NPT, particularly by hardening the consequences of member states withdrawing from the treaty, as North Korea did in 2003.

With the leaders of Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and other countries musing at times about the treaty’s unacceptable limits or even leaving the NPT, some say it’s time to focus on barring the door to a future wave of nuclear-arms proliferation.

Opportunity for leadership

“If you have an extra year, it should be used to consider other ideas and priorities than what typically consumes the conversation, and new ways of interpreting the treaty to preserve its integrity,” says Henry Sokolski, executive director of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center in Washington.

It would be smart to focus a bit more on nonproliferation, and maybe a bit less on disarmament, “which tends to consume everyone but doesn’t get the traction people are looking for,” he says.

Some see a “silver lining” in the postponement, in that it offers an opportunity for global leadership.

“The pandemic has thrown everything up in the air [but] leaders will be looking for ways to show their leadership and put it in a good light,” says Rose Gottemoeller, a former undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, and until recently a deputy secretary general at NATO.

For example, she says President Donald Trump is likely to want a big foreign policy win to tout in his reelection campaign, and that could prompt the U.S. to take some disarmament action – such as extending the New START arms reduction treaty with Russia – before the November election.

More broadly, Ms. Gottemoeller says the context of a global pandemic can actually be a boon to the search for more cooperation on other issues.

“I continue to believe that the coronavirus pandemic is providing an opportunity for leaders to come together around international institutions and agreements and to restate commitments to international cooperation,” says Ms. Gottemoeller, now a distinguished lecturer at Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation in Palo Alto, California.

“The NPT regime is no different,” she adds, “so I believe we’ll see [treaty signatories] … coming together around the position that ‘this is a good treaty, let’s recommit to it and strengthen it going forward.’”

A pessimistic view

Yet despite his hopes for new thinking on nuclear issues in the months ahead, Mr. Sokolski says he worries that a remarkably successful 50-year-old treaty might not last another decade.

The NPT took effect in 1970 based on the basic bargain that the five nuclear-armed states of the U.N. Security Council (the U.S., Russia, China, France, and the United Kingdom) would move toward the elimination of all nuclear weapons, while the non-nuclear states committed to not seeking or developing such weapons but would have access to peaceful nuclear energy uses. The NPT took effect in a world where many countries had nuclear weapons programs, but today only India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea stand outside the treaty.

Over the last half-century, the two largest nuclear-weapons powers, the U.S. and Russia, have indeed sharply reduced their stockpiles. But more recently those two powers have shifted to modernizing their arsenals, as China has moved to expand its arsenal. Moreover the U.S. and Russia have moved away from disarmament treaties, with the last major treaty between them, New START, set to expire in February 2021.

Increasingly non-weapons states see the nuclear powers as failing to hold up their end of the NPT bargain, a sentiment that has prompted some NPT members to pursue new initiatives without the major powers. In 2017, 81 countries signed on to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, a document rejected by the nuclear weapons states.

Given the percolating ire of the non-nuclear states, some experts say they are not certain that the postponement of the NPT review conference will lead to greater global unity on disarmament and nonproliferation down the road.

“For sure the review conference” set for next week “was a train wreck waiting to happen, but nothing guarantees that we’ll find ourselves in nine months or a year in a better position,” says Waheguru Pal Sidhu, an expert on multilateral and U.N. issues at New York University’s Center for Global Affairs. “The opportunity is there, but there’s also a risk of even more disunity.”

Much will depend on how countries, and especially the major powers, choose to address the coronavirus pandemic, Mr. Sidhu says. Proceeding with a spirit of “we’re one world in this together” could in turn foster a greater sense of cooperation on other issues, including nuclear weapons and proliferation. But a “you’re on your own” approach could sour the atmosphere of a major international effort like the NPT review.

“People are talking about international solidarity for addressing COVID-19, but on the other hand we have the proliferation really of these nation-first approaches – America first, Brazil first, India first – that set a tone that does not encourage greater cooperation,” he says.

Less time for mischief?

Some experts worry that what Ms. Gottemoeller calls the “mischief-makers” in the nuclear arena – foremost among them North Korea and Iran – could use the months before the NPT conference to advance their nuclear programs and further weaken the global nuclear nonproliferation regime.

But even there, Ms. Gottemoeller says the pandemic has changed her thinking on how some states are likely to proceed on nuclear issues over the coming months.

“My view has shifted on this, I think the pandemic means they have less time and less incentive to make mischief, because they need the help of the international community,” she says.

She cites the example of Saudi Arabia, which has alarmed the nonproliferation community with talk of purchasing nuclear facilities that could leave it in possession of the fuel and other building blocks for an eventual nuclear weapons program.

But other challenges are likely to put provocative moves like a nuclear program on the back burner, Ms. Gottemoeller says. “I don’t think they’ll be focused at this moment on buying nuclear reactors.”

States band together to take next step against coronavirus

Here’s a report about both self-reliance and mutuality. All over the U.S. governors are partnering in the coronavirus fight. Our writers trace the spirit of that back to its source.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

For America’s governors, one thing has become clear during the past few weeks: These next steps will be exceedingly difficult.

Nothing has tested governors like COVID-19. It stretches across the entire country and has proved hard to control. But opening up will be much harder than shutting down, as governors compete for equipment and struggle to maintain health standards in the face of protests, costs, and skyrocketing unemployment.

No wonder they feel they could use a little backup. Governors nationwide are forming regional partnerships to help think through how to reopen responsibly and strategically. It’s an extension of how governors often operate – relying on one another in emergencies.

But it’s also a reminder that, even in partisan times, governors are the ultimate fix-it crew, judged by getting things done. “We know we need each other’s expertise, support, ideas, troubleshooting,” says David Postman, chief of staff to the governor of Washington state. The hope is that it could have a lasting effect. Should states face something like this again, he adds, “let’s go back and remember what we did in 2020.”

States band together to take next step against coronavirus

David Postman was looking forward to his first day off in more than six weeks. As chief of staff to the governor of Washington state – where the novel coronavirus burst early in the United States – he figured the Easter weekend might provide that opportunity.

It was not to be. Instead, he spent the weekend teleconferencing and texting with his counterparts in Oregon and California. The three chiefs of staff were working on a formal collaboration between their West Coast states, and the governors wanted to move quickly. Rumblings were coming from President Donald Trump about an upcoming decision to reopen states’ economies.

“We need to be out there. We want to show people that we are working together,” says Mr. Postman, recalling the urgency of the moment.

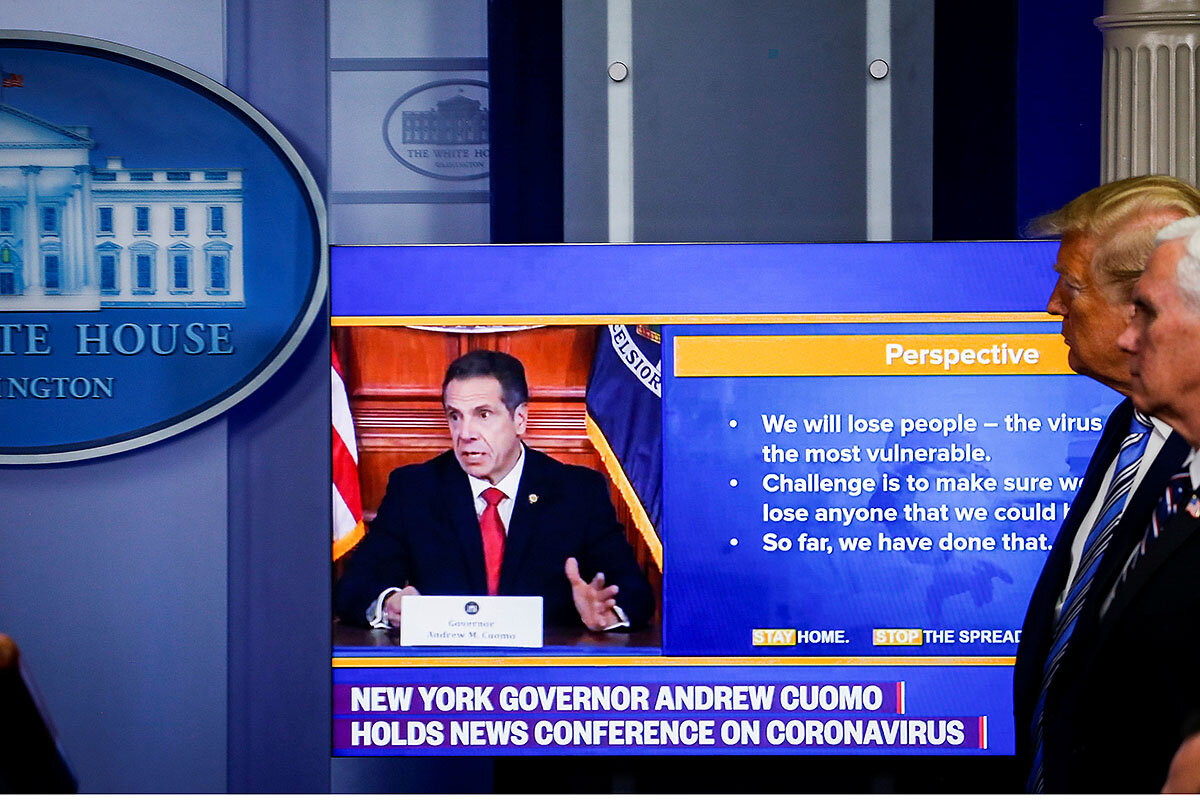

On Monday morning, the governors – all of them Democrats – agreed to guidelines for reopening their economies, including a decline in the rate of the virus’s spread, more testing, and protecting vulnerable populations. The same day, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, also a Democrat, announced a coalition of Northeastern states, followed later in the week by a bipartisan Great Lakes group.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

On one hand, states cooperate on a daily basis, from local agreements on transport to larger ones that affect regions – such as Eastern states capping greenhouse gases and Western ones sharing Colorado River water. And when hurricanes, fires, or floods hit, states are quick to send firefighters and utility trucks.

But nothing is testing governors like COVID-19. It stretches across the entire country, and it is unpredictable and harder to control. While governors say they will rely on science to open up their economies, the science is not so clear. And opening up will be harder than shutting down, as governors compete for equipment and struggle to maintain health standards in the face of mounting pushback, costs, and skyrocketing unemployment.

To this point, that is the key question binding these partnerships: How do they reopen responsibly and strategically? For instance, when is it OK to allow elective surgeries, or how to conduct contact tracing? The coalitions are a reminder that even as the “political poison” in Congress has “leaked” into the states, relationships among governors are “nothing like it is in Washington,” says former New Jersey Gov. Thomas Kean.

Members of Congress are graded on speeches and votes, he explains. Governors, on the other hand, “get graded on what you’ve done. Period.”

That means getting the next steps right. And governors know they’ll need one another.

“The effect of this pandemic is so much more widespread than any other calamity, or emergency, or crisis in anyone’s memory – and its path and duration are hard to predict,” says John Weingart, director of the Center on the American Governor at Rutgers University in New Jersey. “No one wants restrictions relaxed too soon, but what nobody knows is the definition of ‘too soon.’”

Remember Dick Thornburgh

Emergency planning is the very first thing new governors learn about when they gather after Election Day for training by the National Governors Association. A telling example for the newbies: Pennsylvania Gov. Dick Thornburgh. In 1979, after less than three months in office, he had to deal with the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant.

States should be able to count on federal help with resources, guidance, and expertise, Mr. Weingart says. On Thursday, Congress passed nearly $500 billion in coronavirus-related aid on top of $2.5 trillion already passed.

But generally, “states would prefer to rely on each other, as opposed to the federal government,” says Raymond Scheppach, former executive director of the National Governors Association. “They understand each other and they’ll get answers quicker.” They even have a formal compact that allows them to share assistance during emergencies – including smokejumpers, National Guardsmen, and equipment.

In today’s crisis, regional cooperation is “the only way to do it,” says Mr. Kean, a popular two-term governor in the 1980s. What if New Jersey were to open its beaches before New York? he posits. “All the people in New York are going to come to our beaches.”

He and Democrat Mario Cuomo, a former New York governor, met at least once a month over dinner or lunch. They became close friends. Good relationships with the governors of Massachusetts and North Carolina also led to the governors “stealing” ideas from one another, he says.

That same approach must apply now, many governors say. Republican Gov. Charlie Baker of Massachusetts spoke in a local TV interview Monday about the need to get over “the baloney and the noise” of partisan politics. “We’re all in this together and we need to behave and act like that,” he said, rattling off the names of his counterparts from Maine to New Jersey, most of whom are Democrats.

Regional cooperation is vital, he said last week, given how integrated New England states’ economies are. About 250,000 out-of-state drivers enter Massachusetts on an average weekday, including nearly 150,000 commuters from New Hampshire and Rhode Island.

“Part of the planning also requires listening to and learning from our neighboring states,” Governor Baker said, though he emphasized that he would always act first and foremost in the interest of Massachusetts citizens.

That is the balancing act ahead – weighing one state’s needs, and even counties within states, against the needs of neighbors. The point was stressed by the seven Midwestern governors who formed a bipartisan coalition in the broader Great Lakes area. (The group includes Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana.)

“Phasing in sectors of our economy will be most effective when we work together as a region,” they said in an April 16 statement. “This doesn’t mean our economy will reopen all at once, or that every state will take the same steps at the same time. But close coordination will ensure we get this right.”

Relationship with D.C.

Some governors have butted heads with the president over his authority, over shortages of tests and personal protective equipment, and his encouragement of protesters to “liberate” certain Democratic states from restrictions. But they have generally praised the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for its expertise and Vice President Mike Pence for his outreach. And Wednesday saw California’s Gov. Gavin Newsom – who has led the Democratic “resistance” against the president – touting a “very good phone call” with President Trump. More testing swabs are on the way, the president assured him.

In that way, the cooperation between states is not just about filling federal gaps, suggests Mr. Weingart. “It seems clear that the effect of the virus is different in different parts of the country, or on a different schedule, and it’s a healthy response for states to band together in some instances.”

This week, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis announced that six Southeastern states, all led by Republican governors, are also forming a coalition to share ideas about reopening. They are moving more quickly and broadly to loosen restrictions than their Democratic counterparts, though Colorado’s Democratic governor announced he will let his state’s stay-at-home order expire next week and allow businesses to reopen with restrictions.

Mr. Scheppach expects that governors will become closer because of this challenge, and hopes their efforts will lead to greater cooperation in the future. So far, the American public has given governors high marks for their handling of the crisis, with 76% of Democrats and 73% of Republicans praising their state’s governor, according to a Monmouth University poll released last month.

“We know we need each other’s expertise, support, ideas, troubleshooting,” says Washington state’s Mr. Postman. Should states face something like this again, “let’s go back and remember what we did [to collaborate] in 2020.”

Staff writer Christa Case Bryant contributed to this report from Boston.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Jobless benefits are a lifeline – if the unemployed can get access

The lessons in this piece are about readiness, and they’re tough ones. Jobless benefits – meant to ramp up automatically as needed – are faltering in the face of a severe test. We wondered what needs to change.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When the Pittsburgh restaurants where Ciara Bailey worked had to close in March, she quickly filed a claim for unemployment benefits. But now, weeks later, she’s still not sure if her claim will be accepted, let alone when her first check will arrive.

“It’s really scary, especially now that money is dwindling,” Ms. Bailey says, describing how she’s stretching to make a food budget last for herself and her 8-year-old daughter.

Similar challenges are playing out for legions of newly unemployed Americans, after efforts to contain the coronavirus brought major parts of the economy to a halt. Millions of jobless claims are being paid. But state agencies that administer the benefits are scrambling to staff jammed phone banks and patch outmoded software. The race to help the unemployed is teaching hard lessons in readiness for a program widely viewed as an automatic stabilizer that people can count on to gear up during economic hard times.

“There has been a lack of attention nationwide to this program,” says Julia Simon-Mishel, a specialist on unemployment compensation at Philadelphia Legal Assistance.

Jobless benefits are a lifeline – if the unemployed can get access

Every morning, Ciara Bailey wakes up at 7:45 a.m., calls the Pennsylvania Department of Labor & Industry when it opens at 8:00 a.m., and waits on hold – only to get disconnected.

Ms. Bailey filed for unemployment in March after both of the Pittsburgh restaurants where she worked closed due to the COVID-19 outbreak. She says many of her co-workers have started to receive unemployment benefits, but a check has yet to arrive in her mailbox.

“It’s scary, it’s really scary, especially now that money is dwindling. Having my daughter, do I go [work] somewhere that’s essential, like a grocery store and work and come home?” says Ms. Bailey, whose 8-year-old daughter has only one lung and has gone to a hospital for flu-like symptoms in the past. “I would be coming home … and putting everybody else at risk too.”

Like so many Americans, the single mother now needs unemployment benefits to survive an economic downturn that is pushing unemployment to rates not seen since the Great Depression. With more than 26.5 million Americans having filed jobless claims in the last five weeks, the very urgency of the problem has made it hard for Americans to tap into vital and promised assistance.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

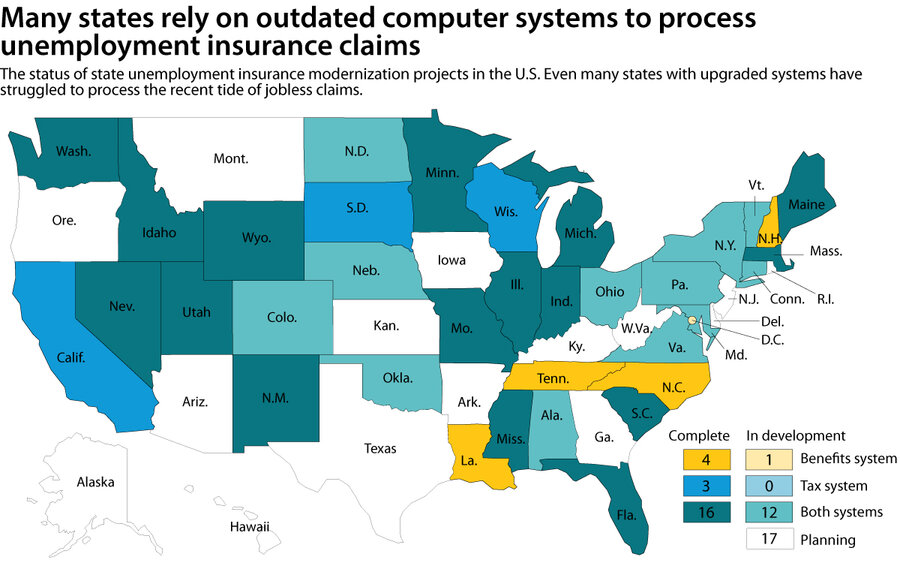

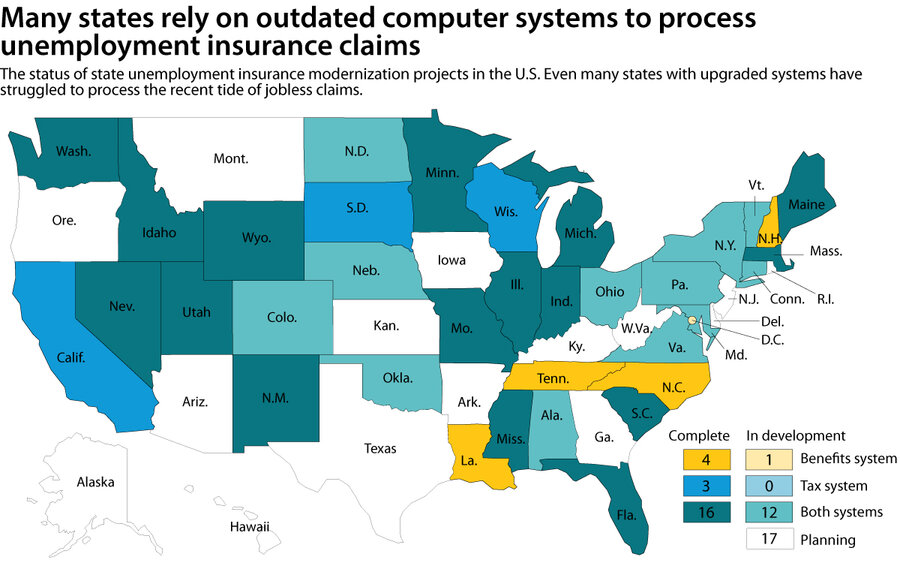

Millions of unemployment claims are being processed successfully, yet experiences with jammed phone lines, website glitches, and weekslong delays have been nearly as common. The problems partly reflect flawed or outdated software, and partly they reveal a failure of imagination: that a major economic shock could hit so many workers so quickly. The race to help the unemployed is teaching hard lessons in readiness for a benefit widely viewed as an “automatic stabilizer” in economic hard times.

“Right now, for a majority of [jobless] people, unemployment compensation benefits are the only form of income they’re going to have access to,” says Julia Simon-Mishel, the supervising attorney for the unemployment compensation unit at Philadelphia Legal Assistance. “There has been a lack of attention nationwide to this program, so of course states are struggling to process this incredible number of claims.”

Atop it all, efforts by Congress to prevent a wider economic collapse have added extra pressure on states, which administer the nation’s unemployment insurance system. Recent legislation pledges an extra $600 per week in unemployment benefits and widened eligibility so that self-employed or gig workers can qualify. Many states are still struggling to deliver these new benefits.

“For years, state unemployment systems have been underfunded from an administrative perspective,” says Ms. Simon-Mishel.

Some good news: The additional $600 per week is starting to flow in most states, says Andrew Stettner, an unemployment expert at The Century Foundation. The processing of claims seems to be improving, he adds, with 71% of claims submitted since the start of the crisis now registering as insured unemployment.

Ms. Bailey believes her application is on hold because the office denied an earlier unemployment claim she filed after quitting a previous job in February. Repeated attempts to communicate the situation with the office have proved fruitless, and the two emails she received from the office were contradictory and confusing on whether her claim was accepted.

“It was like they read my message and wrote whatever they wanted to. They didn’t answer my questions or anything,” she says.

Stretching a food budget

Currently, Ms. Bailey and her daughter are living off $355 worth of federal nutrition assistance she received on April 13. She’s responsible for a $70 phone bill – her lifeline to the unemployment office – but thanks to a generous landlord, she hasn’t paid rent since February.

To pass the time in quarantine, Ms. Bailey and her daughter, Brooklyn, walk up and down Pittsburgh’s rolling hills, baby dolls in tow. She says she has enjoyed spending more time with her, but that it’s also heartbreaking when Brooklyn asks her for food she can’t afford or why she can’t go outside and play with her friends.

“She’s just sick of eating the same things already and can’t understand that we can’t eat all day right now,” says Ms. Bailey. “I’ve got less than a hundred dollars to my name yesterday, and she’s used to things that she wants me to buy her, and I don’t have the money to. It breaks my heart, you know. What do I do when I can’t give her what she needs?”

Ms. Bailey’s experience notwithstanding, Pennsylvania’s unemployment system appears to have worked about as well as most in this crisis. Pennsylvania began to overhaul its system in 2017 and was on track to roll out the new product this fall, but the economic fallout from the coronavirus has upended this plan.

Analysts say America’s spike in joblessness is undercounted, so far, because so many self-employed or gig workers haven’t been able to file claims. The federal government’s $2.2 trillion economic relief package created pandemic unemployment assistance to expand benefits and cover these people, but states are still in the early stages of enabling their applications.

While no state system has gone unstrained, some are dealing with the new demands better than others. Washington state, for example, has been quicker than many to widen the pool of claimants and roll out enlarged payments.

Along with hiring hundreds of new workers in recent weeks (like some other states), Washington overhauled its system after the 2008 financial collapse and recession – a decision that Employment System Policy Director Dan Zeitlin says helped them avoid a claims-processing disaster.

By contrast, jobless workers in Florida have faced grueling delays. As of last week, the state’s unemployment system has processed only 4% of 850,000 applications since the crisis began in March, according to the Orlando Sentinel.

Why state systems falter

Systems are crumbling due to their rigidity and age. Many of them are decades old and were written in COBOL, a programming language designed in 1959 that fell out of college curriculums in the 1980s. States like New Jersey are scrambling to find coders. And even newer systems aren’t necessarily flexible enough to handle a historically rapid surge in demand.

“Most states are experiencing the equivalent of a [cyber] attack on their website,” says Mr. Stettner, of The Century Foundation. “And even the best ones … are not modernized, they’re not in the cloud. That limits [their] ability for expandability and remote work.”

The Information Technology Support Center (a group supporting state unemployment-system upgrades)

A report released Thursday by the U.S. Labor Department Inspector General’s office expounded on this theme, citing longstanding concerns including that ”states have been slow to modernize unemployment systems.”

Challenges have been amplified in some states by policy shifts in recent years that reduced benefits or made them harder to access, according to the National Employment Law Project in New York.

Ms. Simon-Mishel in Philadelphia adds that systems are often optimized for state officials, rather than workers.

“I wanted to share a list of best practices to share with the legislature, but I could only find examples of where these projects had gone wrong and what had gone wrong,” she says. “If you’re going to spend millions of dollars upgrading your technology, it should make it easier for workers.”

On Easter Sunday, Ms. Bailey got a two-line email response from the unemployment insurance office indicating she was financially eligible for unemployment benefits. She was thrilled. In a text to the Monitor, she said, “So, that’s a bit of light at the end of the tunnel, hopefully.”

Many days later, though, she still hasn’t been able to submit a claim, much less received money. She worries about her ability to stretch her food and money till next month’s nutrition assistance arrives.

So Ms. Bailey’s morning routine remains the same: wake up, call the office, wait.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

The Information Technology Support Center (a group supporting state unemployment-system upgrades)

Hope for student borrowers: Settlement requires administration move faster

Much of the narrative around student loans focuses on the extended hardship that they can create. We wanted to explore the issues of accountability and fairness in a complex push for loan forgiveness.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

When Theresa Sweet enrolled in the Brooks Institute of Photography in California, she didn’t realize the school had been bought out by a for-profit company. Two years into a program that required Ms. Sweet to take out $46,000 in federal loans, Brooks came under investigation for mischaracterizing graduates’ salaries and other suspicious practices.

By the time Ms. Sweet graduated in 2006, she says the only photography jobs available were unpaid. She has worked in sales and as a nursing assistant ever since. In 2016, she filed a “borrower defense” claim that would qualify her for loan forgiveness, and has been waiting for an answer from the U.S. Department of Education.

She is the lead plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit that reached a proposed settlement this month with the agency, which has agreed to a firm 18-month deadline for processing such claims. The compromise represents one step of progress while the larger question continues to play out: What’s the fairest way to satisfy the rights of misled borrowers while ensuring that students, colleges, and the government all fulfill their respective responsibilities?

For Ms. Sweet, the settlement “feels like a huge victory.” But even if her federal loans are forgiven tomorrow, she says, “I’m still starting from scratch.”

Hope for student borrowers: Settlement requires administration move faster

Fresh hope arrived this month for about 170,000 student borrowers who say their colleges defrauded them. Their requests for forgiveness of federal student loans, known as “borrower defense” claims, have gone unanswered by the U.S. Department of Education for months or years.

Now the agency, led by Secretary Betsy DeVos, has agreed to a firm 18-month deadline for processing the claims, through a settlement of the class-action lawsuit Sweet v. DeVos. With both sides framing it as a win, the compromise represents one step of progress while the larger question continues to play out: What’s the fairest way to satisfy the rights of misled borrowers while still ensuring that students, colleges, and the government all fulfill their respective responsibilities?

Recent actions by Congress, and multiple court rulings, reveal a bipartisan appetite for accelerating relief for defrauded borrowers.

Lead plaintiff Theresa Sweet says she followed a community college professor’s advice when she enrolled at what was then known as the Brooks Institute of Photography in California. The professor didn’t realize the school had been bought out by a for-profit company, she says. But two years into a program that required Ms. Sweet to take out $46,000 in federal loans and additional private loans, Brooks came under investigation for mischaracterizing graduates’ salaries and other suspicious practices.

By the time Ms. Sweet graduated in 2006, the only photography jobs the “career” office suggested were unpaid, she says in a phone interview. She has worked in sales and nursing assistant jobs ever since, she says.

After phoning hundreds of lawyers and getting nowhere, Ms. Sweet finally discovered the option of filing a borrower defense claim in 2016. She’s still waiting for an answer from the Education Department.

The settlement “feels like a huge victory,” she says. “I will get an answer. ... I won’t be just on the hook, waiting and waiting and waiting like I have been since I graduated.” But even if her federal loans are forgiven tomorrow, she says, “I’m still starting from scratch,” trying to build a positive credit history.

A reprieve for borrowers

The agreement will wipe out any interest these borrowers have accrued since filing their claims – once class members have the opportunity to comment and it is approved by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California.

It also includes the assurance that each month of delay beyond the new deadline would automatically lop 30% off an individual’s debt. And the agreement bars the garnishment of wages or other involuntary loan collections – with violations resulting in 80% of the borrower’s debt being canceled, according to the Project on Predatory Student Lending at Harvard University, which provided counsel for the plaintiffs.

“Getting rid of some of that interest and stopping the collections for this set of borrowers is really important; a lot of these people are in default,” says Beth Stein, a senior adviser at The Institute for College Access & Success (TICAS).

Some of them are military veterans who used up their post-9/11 GI Bill education benefits and have told the Project on Predatory Student Lending that they feel betrayed not only by their schools, but now by the government as well.

Secretary DeVos has long held that her job is to protect American taxpayers by looking closely at borrower defense claims and demanding adequate proof that a student has been harmed. In public remarks she has attributed the delays to various lawsuits challenging the department’s approach.

The Education Department called the Sweet settlement “an important win for students and for taxpayers,” in a statement emailed to the Monitor by press secretary Angela Morabito. “The Department put a sound adjudication methodology in place. ... This proposed settlement is validation of that process and of the Department’s longstanding goal to resolve all of these claims as quickly as possible.”

In October, a federal judge in a separate case held Secretary DeVos in contempt because the Education Department illegally tried to collect debt from thousands of borrowers defrauded by the now-defunct Corinthian Colleges.

After more than a year in which the agency processed no borrower defense claims, the wheels started turning again in December. The Project on Predatory Student Lending estimates that 40,000 claims have been processed since then.

Secretary DeVos, aiming to reverse what she deemed overreach in the Obama administration, has written a new borrower defense rule, set to take effect July 1.

Among other restrictions, it would take away borrowers’ right to appeal, says Kyle Southern, who directs higher education policy work for the nonprofit advocacy group Young Invincibles. “This department has shown itself time and again to be more concerned with protecting the interests of predatory for-profit institutions than the rights of defrauded student borrowers,” he says.

The U.S. House and Senate have both voted on resolutions, with some bipartisan support, to overturn the new rule. In February, President Donald Trump’s advisers said they would recommend a veto, but he hasn't yet stated his intentions.

Embarrassment and accountability

Ms. Sweet says many borrowers in her situation are embarrassed to talk about falling for their college’s false promises. But she hopes the lawsuit will help the public “understand that what happened to us, it was fraud.” The government should be protecting students, she says, and if taxpayers are going to be upset, they should direct it at agencies that failed to hold schools accountable. “They shouldn’t be angry with students who were defrauded,” she says.

The debates over borrower defense claims are part of a “much bigger college accountability debate,” says Neal McCluskey, director of the Center for Educational Freedom at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. While borrower advocates criticize Secretary DeVos for hiring people with ties to the for-profit education industry, he says, she has in turn suggested that those trying to police the industry are overzealous.

“We have seen evidence sometimes that charges against schools, lenders, services – that they appear worse when first reported than they are when you dig in,” he says.

Robert Eitel, an adviser to the Education Department and former executive at two for-profit education companies, generated controversy by reportedly being involved in rescinding the former borrower defense rule. An inspector general’s report recently concluded that Mr. Eitel did not appear to be in violation of federal ethics laws.

Depending on the extent of the economic slowdown, for-profit colleges might scale up quickly to encourage people out of work to go back to school, says Ms. Stein of TICAS. She offers some advice to prospective students: Shop around, and don’t let a school pressure you into making a quick decision to enroll.

“The Department of Education has really worked hard, under this administration and the previous administration, to get better information online for students through the College Scorecard,” she says. “See if you could go to a similar program at a community college or somewhere else nearby for a whole lot less money.”

A new vision for farming: Chickens, sheep, and ... solar panels

When both food production and power production are localized, one predictable result can be a fight over land. We set out to find, instead, some case studies in coexistence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Lynn Freehill-Maye Contributor

Picture this: A field of solar panels that, instead of being overrun by weeds, has livestock roaming around and vegetables growing in the panels’ shade.

Such experiments in agrivoltaics, or co-locating solar panels and food production, are being undertaken around the United States. The practice can include vegetables that need some shade, and grazing livestock – like cows, goats, sheep, or even chickens. The idea is that livestock’s munching can keep plants from growing too tall and shading the panels, thus saving on mowing, and cutting down on vegetation maintenance costs and emissions.

With photovoltaic capacity projected to more than double (again) over the next five years, some farmers who lease the land they grow crops on worry about their landlords renting it out to someone else, including solar farms. Agrivoltaics proponents hope this approach will ease concerns.

“You’re seeing farmers sell off land and transition it to solar,” says Greg Barron-Gafford, an associate professor at the University of Arizona who studies the impacts of large-scale land-use change. “Our hope is this could allow us to keep more food production in areas that need energy production.”

A new vision for farming: Chickens, sheep, and ... solar panels

When Jackie Augustine opens a chicken coop door one brisk spring morning in upstate New York, the hens bolt out like windup toys. Still, as their faint barnyard scent testifies, they aren’t battery-powered but very much alive.

These are “solar chickens.” At this local community egg cooperative, Geneva Peeps, the birds live with solar power all around them. Their hen house is built under photovoltaic panels, and even outside, they’ll spend time underneath them, protected from sun, rain, and hawks.

Geneva Peeps is one of the many experiments in agrivoltaics, or co-locating solar panels and food production, being undertaken around the United States. The practice had already been happening in countries like the United Kingdom and Uruguay. Over the past few years, more pilot programs have been set up in states like New York. And with photovoltaic capacity projected to more than double (again) over the next five years, some developers are exploring whether agrivoltaics may ease concerns about farmland being given over to solar production.

“You’re seeing farmers sell off land and transition it to solar,” says Greg Barron-Gafford, an associate professor at the University of Arizona who studies the impacts of large-scale land-use change. “Our hope is this could allow us to keep more food production in areas that need energy production.”

Finding the right pairing

Agrivoltaics doesn’t just include chickens. Other livestock also can roam around solar panels, and some researchers are experimenting with planting crops, too.

Animals that graze around solar fields offer several benefits, proponents of agrivoltaics say. Not only does their manure enrich the soil, their munching keeps plants from growing too tall and shading the panels. Another win: They lower vegetation maintenance costs, reducing the need for lawn mowers or landscapers.

Pilot agrivoltaic programs have tried many grazers – with varying success. The chickens at Geneva Peeps, for example, aren’t grazing powerhouses. Founder Jeff Henderson admits that he still has to fire up the lawn mower sometimes.

When solar panels are elevated for them to roam beneath, cows do better, as shown in a University of Massachusetts pilot. But the higher materials cost of raising panels has kept “solar cattle” from taking hold yet. Goats have been tried, too, but they sometimes jump on panels and chew wires.

The winner among livestock so far has been calm, eat-anything-and-everything sheep. In fact, most of the members of the American Solar Grazing Association, founded in 2017, are shepherds. (Honeybees can be part of the mix with sheep, too.)

Researchers, like Dr. Barron-Gafford at the University of Arizona, are also studying how well crops grow under panels.

Dr. Barron-Gafford noticed that in the desert, saguaro cactuses spend their first 10 to 15 years growing in the shade of mesquite trees. Surmising that shade from solar panels could benefit crops, too, he has studied how agrivoltaic setups affected food yields and water usage in dryland areas. Among his findings: Chiltepin pepper plants yielded three times as much fruit, and tomatoes twice as much, under photovoltaic panels. They required less irrigation, and temperatures under panels where crops were growing were lower, too.

“You’re seeing more and more solar installations out in rural areas,” Dr. Barron-Gafford says. “We’re seeing here that putting solar overhead can provide a consistent energy source, can reduce the water you need to use, and that food is giving back to your solar by helping keep it cool [through transpiration].”

Seeking common ground

Still, tensions remain between solar and agriculture. Farmers who lease the land they grow crops on often worry about their landlords renting it out to someone else, including solar farms. And rural residents may want to see their area hold onto its farming heritage. A California developer, Cypress Creek Renewables, riled up rural New York in 2016 when it mass-mailed farmers seeking leases on 20-plus acre fields.

Lewis Fox, co-founder of the American Solar Grazing Association, has found that involving animals helps solar skeptics lower their defenses. He’ll bring lambs to a project open house and find locals open up a bit more. Often, he says, they find it reassuring that local land can stay in agriculture, even if solar is added.

“Solar in general is unfamiliar to people, and if you hear there’s a large development coming to your town, people naturally get defensive, a little suspicious,” Mr. Fox says. “There’s support, but also a lot of concern. Once people come out to a site and see it being grazed, it kind of clicks. A well-managed grazing program on a site is very productive. It’s not just throwing a few sheep out and letting them go wherever for a season. We can raise a lot of meat on an acre of raised panels. It’s a serious form of agriculture.”

Still, Mr. Fox has seen friends in the dairy industry lose leased land. Agrivoltaics can’t ease all those tensions, he concedes. “I don’t think setting up grazing contracts is going to paper over issues of people losing leased land,” he says. “It’s definitely important that developers are good actors working in ethical ways.”

Another key to being received better, some solar developers say, could be not to “co-locate” solar and agriculture on the exact same parcels of land. “Instead of 100 acres of prime farmland, we should work with four farmers and use 25 acres of marginal farmland each,” suggests Bill Jordan, founder and CEO of Jordan Energy & Food Enterprises LLC, an Albany-based company that specializes in on-farm photovoltaic placement.

Mr. Jordan argues that solar can actually help save farms more easily if panels are situated on the property’s wetter, hillier farmland, or on roofs. “There’s a lot of solar going in – it could push farmers out of farming, or diversify the family farm,” he says.

First came the chickens

Mr. Henderson didn’t know about agrivoltaics when he founded Geneva Peeps in 2015. His goal was simply to help local families raise chickens. Backyard coops aren’t allowed in the Finger Lakes town of Geneva, New York, but he found industrial-zoned land where they’d be permitted.

Forty families now share weekly chicken-care shifts of 10 to 15 minutes. Ms. Augustine pedals over for her shift, and with her bike helmet still on, checks the hens’ food and water. In return, she and fellow members get a dozen or more eggs at a time.

The year after launching, Mr. Henderson installed 44 kilowatts’ worth of solar panels, both powering the operation and producing excess for the grid through net metering. There wasn’t enough room on the chicken coops to install rooftop panels, but he did have more than an acre of land – more than 180 egg-layers really needed. Mr. Henderson wasn’t aware of any similar farms combining solar and chickens, but he figured the project could be a local sustainability model.

“We knew they could all coexist together because there’s no reason you can’t have solar panels and chickens,” Mr. Henderson says. “One of the hopes is this will give people an idea of a way you could do it.”

This story was published as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story. It was produced with support from an Energy Foundation grant to cover the environment.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

For Syria, a light of justice in a German courtroom

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

After nine years of a brutal war in Syria against pro-democracy civilians, a bit of sunlight began to shine Thursday on the war’s atrocities. Two former members of Syria’s secret police went on trial in Germany for crimes against humanity based on evidence of state-sponsored torture. The trial is the first time an independent court will be able to provide some justice for victims of the regime of Bashar al-Assad.

The trial is made possible because of a global effort to document war crimes in Syria, including the amassing of more than 50,000 photographs and thousands of witness accounts. Now, in this first step toward justice, victims of the war will be able to confront their alleged perpetrators. This display of accountability could send a signal to those still in the Assad regime that they could face such a trial someday.

If the two men are convicted, it may embolden more victims to provide evidence of war crimes, perhaps hastening an end to the conflict. The voices of the innocent can be a powerful antidote to the violence of war. They are also essential to national reconciliation in such a war-ravaged country.

For Syria, a light of justice in a German courtroom

After nine years of a brutal war in Syria against pro-democracy civilians, a bit of sunlight began to shine Thursday on the war’s atrocities. Two former members of Syria’s secret police went on trial in Germany for crimes against humanity based on evidence of state-sponsored torture.

The trial is the first time an independent court will be able to provide some justice for victims of the regime of Bashar al-Assad. At the least, the courtroom exposure of the regime’s systemic abuse of civilians will set a precedent for the eventual truth-telling necessary to heal Syrian society once Mr. Assad is removed from power.

Germany was able to prosecute the two defendants, Anwar Raslan and Eyad al-Gharib, because they were found living in the country and arrested last year. Like the victims who will testify against them, they too chose to flee Syria.

Germany abides by the principle of universal jurisdiction, or the idea that a country can prosecute war crimes committed outside its borders. Such a claim is supported by the fact that Russia, the main ally of Mr. Assad, has prevented an international court from pursuing cases involving Syrian atrocities. Russia can use its veto in the United Nations Security Council to block this path of justice.

In addition, Germany has been affected heavily by the war in Syria. It has accepted hundreds of thousands of refugees who fled the war, many of them victims of torture and rape.

The trial is also made possible because of a global effort to document war crimes in Syria, including the amassing of more than 50,000 photographs and thousands of witness accounts. In 2016, in defiance of Russia, the U.N. General Assembly established an independent investigative mechanism for Syria.

Now, in this first step toward justice, victims of the war will be able to confront their alleged perpetrators. This display of accountability could send a signal to those still in the Assad regime that they could face such a trial someday. The trial also sends a “signal of hope” to the many Syrians who have suffered war crimes, says Germany’s justice minister, Christine Lambrecht.

If the two men are convicted, it may embolden more victims to provide evidence of war crimes, perhaps hastening an end to the conflict. The voices of the innocent can be a powerful antidote to the violence of war. They are also essential to national reconciliation in such a war-ravaged country.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Our always-present help during crises

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Patrick McCreary

At a time of crisis, is panic our only option? One mayor found he could rely completely on God’s help and direction as he navigated an emergency situation in his town.

Our always-present help during crises

In Hutchinson, Kansas, in 2001, there was a crisis. Mid-morning, fiery geysers of gas and water began erupting throughout our city.

As mayor, I was notified immediately and raced downtown to our emergency operations center. Nobody knew how this was happening or how to stop it. Tragically, there were fatalities, buildings in the downtown were destroyed, and we had to put out an order to evacuate hundreds of homes in the affected areas. Yet what happened over the following days and weeks left me with no doubt about the truth of these words from the Bible: “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble” (Psalms 46:1).

I am a lifelong Christian Scientist. Christian Science offers a scientific explanation of the words and works of Christ Jesus, who was the best healer the world ever knew. And Jesus taught his followers that they needed to be healers too by evidencing what he unreservedly proved, that God is “a very present help in trouble.” So as I was racing to get downtown, my thought went immediately to God, affirming that God is divine Mind, and that I and all the citizens are ideas of Mind, God’s children, lovingly cared for and protected, right now. It was a real test of spiritual resolve and faith to remain steadfast in knowing that there is, there can be, only one omnipotent, controlling power.

A Bible passage I thought a lot about at the time says: “Behold, I will do a new thing; now it shall spring forth; shall ye not know it? I will even make a way in the wilderness, and rivers in the desert” (Isaiah 43:19). Over the next few weeks, as my whole attention was on the well-being of our citizens, I held that promise close to my heart. I was committed to never losing sight that God was making a way in the wilderness and that I could see “rivers in the desert.” That I could witness how the divine consciousness was present and more powerful than the extreme material circumstances I was seeing around the clock.

The Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, learned from Jesus’ ministry, as well as from her own experience, that Love is the answer to all human needs. In her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” she writes: “The very circumstance, which your suffering sense deems wrathful and afflictive, Love can make an angel entertained unawares” (p. 574). As powerful and violent as the material situation was that we were being presented with, I knew that divine Love, through angel thoughts, was present and more powerful than any evidence of discord. In my daily visits to citizens in improvised city shelters, I made it a point to let Love lead the way and to provide an honestly sympathetic, receptive ear to the needs and concerns of those I spoke with. And I visited our police and fire services in the field, as they worked around the clock, to learn what I could do to help.

Over a period of a few more days, discord was yielding to harmony. Wonderfully creative and inspired ideas about how to proceed found voice in the many committed and selflessly serving city employees. And those ideas led to solutions involving the state geological service, the United States Army, and even NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Explanations and solutions for this crisis came in rapid succession, many of the families were returned to their homes, and a newfound sense of community replaced fear and disruption. Love was prevailing, as it always does.

“God the Preserver of Man” is the subject of one of the weekly Bible Lessons in the “Christian Science Quarterly.” While evidence of this fundamental truth often seems scanty on the human scene, to the degree we stick with the spiritual facts we increasingly witness and discern more of the spiritual good that is always present. God enlightens human consciousness regarding the harmony of His creation. In reality, God, good, is All-in-all and there is no other power, no other presence. God governs, guards, and guides all right ideas, and these ideas meet every human need.

There’s a verse in the book of Malachi that states: “For I am the Lord, I change not; therefore ye … are not consumed” (3:6). The more we know of God, the more we know of our true selves as His reflection. The more we know of God, the more we see His perfection and power being manifest in every aspect of our lives. The more we know of God, the greater our ability to understand and to bless our neighbors near and far through the spirit of Christ. This was proved in my experience in Kansas many years ago. I have learned that no crisis can paralyze us from turning wholeheartedly to God, our “very present help in trouble.”

A message of love

Welcoming Ramadan

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow. We’ll send you into the weekend with a look at a global spike in pet adoption that includes a tail-wagging video you’ll want to share.