- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What a $1 COVID test and a crowdsourced supercomputer have in common

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

Today’s stories explore European efforts to reopen schools, the use of diversion in presidential communications, a historical view of nationalism during moments of crisis, an unexpected cadre of social media stars, and recommendations for comic relief from our film critic.

For many of us sheltering in place, pandemic life is about getting by with whatever is on hand. From makeshift masks to make-do hairdos, we’re all finding ways to tap into our inner MacGyver. That same spirit of innovation is evident all over the world, as nations with varying resources muddle through this crisis.

When the coronavirus began to appear outside China, officials in Senegal took stock. With 16 million people and just 50 ventilators, they decided to 3D-print their own. And rather than wait for Western nations to donate testing supplies, Senegalese researchers are developing their own diagnostic kits. Their model, which is currently in clinical trials, returns a response in under 10 minutes for about $1. Such innovation has helped Senegal achieve one of the world’s highest COVID-19 recovery rates.

Halfway around the globe, researchers at Stanford University are attacking the problem from a different angle, with the help of about a million volunteers. Ordinary citizens are lending a morsel of their home computer’s processing power to help scientists better understand the coronavirus through the Folding@Home project. Through the power of distributed networks, the project has inadvertently broken the record for the worlds’ fastest supercomputer.

Neither Senegal’s health system nor the Folding@Home network used breakthrough technology to accomplish these milestones. They made do with what they had, and used it in creative new ways.

Which is something we all find ourselves doing in our day-to-day lives these days.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

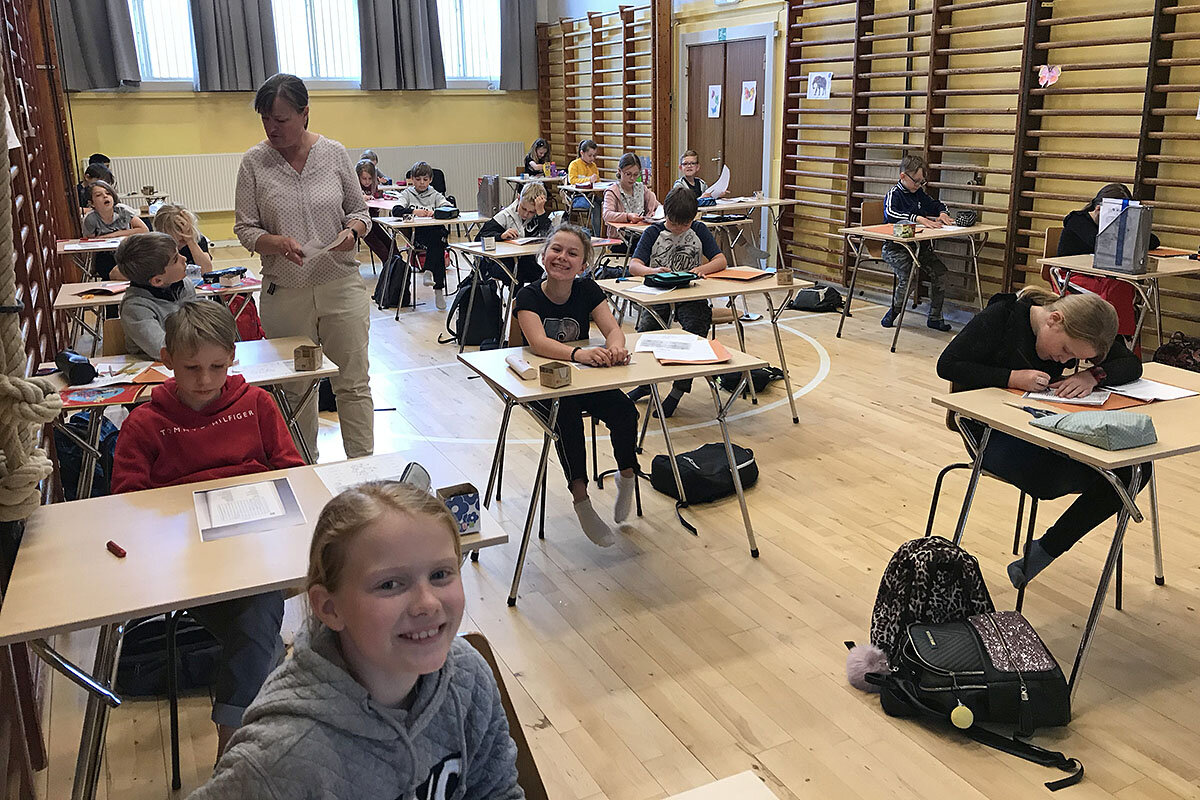

Europe’s schools face new test: Teaching safely in a pandemic

The question of how to reopen schools has loomed large for parents and educators. Europe is starting to feel its way slowly, with a premium on patience and creativity.

-

Colette Davidson Correspondent

-

Jon Kaldan Contributor

Two months after most countries in Europe began closing down in response to the coronavirus, many are cautiously reopening schools alongside their economies, welcoming tens of millions of students back into the classroom in staggered shifts. Denmark was the first to reopen schools in mid-April, followed by France, Germany, Austria, and others.

European governments have been unrelenting with logistical and sanitary requirements. But most countries have otherwise allowed schools to make their own decisions about how lessons should be delivered and physical space partitioned. And they have put a premium on creativity and patience in an environment that has changed vastly since before the shutdown.

Countries are weighing a combination of factors that include science, besides elements such as cultural priorities, as they work out the best path forward. “No one knows exactly what’s going to happen,” says François Dubet, a sociologist and professor emeritus of the University of Bordeaux. “If the number of sick people goes down, we’ll return to normal life, but if in 10 days that number goes up, it’s going to get very complicated.”

Europe’s schools face new test: Teaching safely in a pandemic

Henrik Christensen looks tired.

Ever since the Danish government decreed its youngest children could go back to school, the principal of Marie Mørks School has been up late, planning logistics and sorting how to communicate with the families he serves. The youthful father runs a private school 30 miles north of the Danish capital of Copenhagen, and, with a toddler at home and a 12-year-old at the local public school, he understands the anxiety around bundling kids off to school during a pandemic.

“Of course, you are a bit nervous,” Mr. Christensen says. “But the children have missed school and their friends, and for them a month is an eternity. Their smiles take away most of my fears and reservations.”

Two months after most countries in Europe began closing down in response to the coronavirus, many are cautiously reopening schools alongside their economies, welcoming tens of millions of students back into the classroom in staggered shifts. Denmark was the first to reopen schools in mid-April, followed by France, Germany, Austria, and others. Parents expressed concerns about their children’s health, while teachers worked overtime to serve both students in classrooms and those at home who are waiting for a return date.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

In Denmark, logistics around hygiene have been painstaking. Door handles, washbasins, and school tables are wiped down three to five times daily. Classes have been halved, so students can maintain a 2-meter (6-foot) distance. Outdoor spaces are subdivided into five units, with each class appointed one portion during recess.

Even Legos posed a challenge, explains Mr. Christensen – “until a math teacher came up with a brilliant idea!” The Legos are now separated into four boxes, he says, with each set in use only every fourth day, since the virus is believed to die out after 48 hours on solid surfaces.

Indeed, European governments have been unrelenting with such requirements, and officials are watching health metrics closely. But most countries have otherwise allowed schools to make their own decisions about how lessons should be delivered and physical space partitioned, putting a premium on creativity and patience in an environment that has vastly changed since before the shutdown:

- In Germany, one Berlin school has divided each class into four groups to maintain a required 1.5 meters of space between students. This means teachers are delivering the same lesson four separate times.

- In Denmark, a tiny country with 1 million primary and secondary students, classes are advised to be held outdoors where possible. Outside Copenhagen, one school is tapping the gym as a classroom, and has staggered recess so equipment can be sanitized between shifts. Public trust in the Danish prime minister surged from 39% to nearly 80% at the end of April.

- In France, a reopening of schools is purely voluntary, as the national government has shifted decision-making power to mayors and principals. Even so, the Education Ministry expects nearly 85% of its schools to reopen in some fashion by May 15.

Countries are weighing a combination of factors that include science, besides elements such as cultural priorities, as they work out the best path forward. “No one knows exactly what’s going to happen,” says François Dubet, a sociologist and professor emeritus of the University of Bordeaux. “If the number of sick people goes down, we’ll return to normal life, but if in 10 days that number goes up, it’s going to get very complicated.”

Germany: Back to school before summer, but no mandates

In Berlin, where schools began reopening in late April, many principals at the city’s 900 mostly public schools are staggering students’ reentry to school. That means some children are coming back for as little as two shifts a week for 150 minutes each time, so that a required 1.5 meters of distance can be maintained between students.

Teachers report excitement to be back on campus, but also a sense of exhaustion, as they’re taking on new duties including acting as “supervisor” to how students move around the building.

“As in, ‘Hey! You can’t stand that close to each other. Don’t walk towards each other! Use that exit, not this one,’” says Lydia Puschnerus, who teaches at a public gymnasium (equivalent to an American secondary school) in the Schöneberg district of Berlin. “It’s worked so far, but over the long term it’s stressful and unnatural.”

Björn Nölte, who teaches at a public school just outside Berlin, says daily routines have completely changed. “There’s always a colleague sitting in front of the bathrooms; there are always colleagues in all of the corridors, to make sure students don’t accidentally get close.”

Disinfectant has been dropped off at schools, and Berlin’s government has granted teachers a one-time payment of €16 ($17) to buy masks. Yet aside from “must follow” hygiene rules, Berlin has been reluctant to issue mandates, letting schools decide how to alter their curriculum, whether to skip exams, and how to stagger classes.

That comes out of the need to serve an incredibly diverse population, with varying degrees of income and digital access, says Ryan Plocher, a Berlin social studies teacher and teacher’s union representative.

“Principals really have to weigh [how to reopen], because schools in richer districts can do the whole thing by distance,” says Mr. Plocher. “But in poorer areas, some students haven’t been in contact with schools at all during the shutdown. Their parents can’t or won’t help, as in, ‘I’m not going to download PDFs over my private data plan.’”

Like the principal in Denmark, administrators at Mr. Plocher’s school have halved class sizes to maintain social distance. They’ve also eliminated or decided to monitor heavily the times that children might be in contact without masks. “That’s toileting, eating, drinking,” says Mr. Plocher, meaning that kids come onto school grounds only for a few hours at a time, with no lunch. Bathroom breaks are taken one student at a time.

Mr. Nölte’s school has subdivided some classes even further, into four units. With the help of co-teachers and supervisors, Mr. Nölte is teaching all four groups of a single German class simultaneously, shuttling between four rooms, which each houses five or six children.

Ultimately, Berlin’s guidelines are flexible enough that some schools – particularly those with enough space to maintain the required distance – could go back to full capacity.

France: A voluntary return

In France, the Ministry of Education has left the decision to open in the hands of local government and school leaders. That’s revolutionary, say experts, in a country where education is “extremely centralized.”

The French education minister expects about 1 million students to return to school, with most of France’s 50,500 schools slated to open in some form. Still, about 10% of towns aren’t expected to reopen schools yet.

“The pandemic is forcing us to decentralize a bit,” says Mr. Dubet. “We’re going to go from a national policy, which is extremely powerful in France, to local policies. This is a new experience for us.”

What is not new, however, is a long-standing familiarity with having to occasionally miss school. In 1968, a social movement led by university students brought the country to a standstill. Earlier this academic year, students of all ages missed class intermittently over the course of about two months due to nationwide strikes against the government’s pension reform plans.

In 1968, no one recorded negative effects of time away in terms of learning gaps, says Mr. Dubet, and most likely no one will now. “The major concern [now] is that students can see their teachers and friends again, that their parents can start working again. Not the education itself.”

For schools opening this week, a 56-page guideline lays out 1 meter (3 feet) of distance between desks and a maximum of 15 students per class. Teachers must wear masks; no ball-playing is allowed. And while preschools and elementary schools open this week, middle schools will follow next week, and high schools at a yet-to-be named date.

Education will look completely different, says Laadja Mamadi, director of a Paris elementary school. “It’s not going to be school as we know it,” says Ms. Mamadi. “We teachers will need to adopt new habits, and so will the students.”

At the 7ème Art public preschool in Paris, for example, teacher Justine Cocquerelle is scanning her classroom to see what needs to be moved, removed, or replaced. Tiny tables host only one miniature chair each; a classroom that usually hosts 25 children will now only take seven at a time, each at his or her own table. Building blocks have been tucked away, and a blanket has been tossed over the books.

“I can’t leave out anything that’s shared between children,” says Ms. Cocquerelle, who returned to school a few days ahead of Thursday’s official reopening. Even the class rabbit, Susie, has been removed from the classroom now that cleaners will be using bleach to disinfect the room at least twice a day. “I’m trying to figure out how I’m going to do this.”

She plans lots of written activities, reading, and singing. Art projects mean individual portions of paint, glue, and tape. Bathroom procedures are still a work in progress, as the four small toilets don’t allow enough distance. What’s clear is that Ms. Cocquerelle will now have double the workload, since she’ll be prepping both in-class activities and online lessons for those who might not return.

“It’s super-complicated,” says Ms. Cocquerelle. “But we hope [the government] sees that it’s working and they open things up a little more.”

France and Denmark have prioritized getting their youngest children back to school. The little ones might be harder to socially distance, they’ve noted, but they need more guidance from an adult, and are still learning social competencies and how to organize work. Plus, young children seem to be less susceptible to serious complications of the coronavirus, and some anecdotal research has suggested that they're less likely to transmit it to adults.

By contrast, other countries like Germany have decided older students should return to schools first, as they’re closer to exams. “That’s not necessarily a pedagogical decision, because tests at the end of ninth grade have been canceled [in Berlin],” says Mr. Plocher, the social studies teacher.

Yet Dr. Karen Wistoft, a Danish education professor, has found that teenagers are feeling more lonely and understimulated during isolation than their younger peers. “The learning potential of teens is so connected to their mental well-being,” she says.

Denmark: Phase 2 of reopening

Back at Marie Mørks School near Copenhagen, Principal Christensen is trying to decide whether a ball is a toy or an “educational tool.”

“If it’s defined as a toy, it has to be wiped down every time it changes hands,” says Mr. Christensen. “But if it is an educational tool, it only has to be cleaned after the school day has ended. The rules are less strict.”

He declared the ball a “tool.” “We have to balance the rules with common sense!” he says.

The Danes are feeling so confident with their reopening strategy that the government announced a second phase of reopening that allows high schoolers to return on May 18. The health authority has also reduced the required social distance in schools from 2 meters to 1.

In Berlin, schools are a few weeks behind Denmark’s reopening, but Mr. Nölte, the teacher at a public school near Berlin, has noticed there’s plenty of joy in coming back together, even in staggered format. “I’ve noticed how happy the students are to see each other,” he says. “Even between my colleagues, I think we will grow closer.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Amid pandemic woes, Trump turns spotlight onto ‘Obamagate’

Many presidents have used diversion as a tool at times of political stress. But President Trump has demonstrated a talent perhaps unrivaled at getting the media and public to jump from issue to issue until they lose focus.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

With the coronavirus pandemic still holding the United States in its grip, President Donald Trump has spent the week railing about former President Barack Obama.

Republican senators on Wednesday released a list of Obama-era officials – including former Vice President Joe Biden – who, during the transition period, requested to “unmask” the name of an American caught on wiretap communicating with a foreign espionage target. That American turned out to be former Trump national security adviser Michael Flynn. Some Republicans offered it as proof of a “setup of General Flynn.”

Unmasking is common – the National Security Agency has dealt with 10,000 to 17,000 such requests annually in recent years. And some of the requests came at a time when the sitting administration was growing increasingly concerned about contacts between the Trump team and Russian officials.

In that sense, the charges may be an example of one of President Trump’s favorite – and most effective – tactics: diversion. Time and again, the president has used the reach and repetition of social media and an accelerated news cycle to provide talking points for supporters, crowd out news that’s negative, and generally leave voters confused or even uncertain as to whether objective truth about the subject in question exists.

Amid pandemic woes, Trump turns spotlight onto ‘Obamagate’

In a week when the coronavirus pandemic still held the U.S. in its grip and government health officials publicly warned the nation to be wary of restarting normal life prematurely, President Donald Trump accused his predecessor of criminal acts and hinted that a talk show host he dislikes was possibly involved in a murder.

Both charges are unfounded. But they could be yet more examples of one of President Trump’s favorite – and most effective – rhetorical strategies: diversion. At times of political stress, he has demonstrated a talent perhaps unrivaled in modern American politics for pointing one way, then another, then another, getting the media and public attention to jump from issue to issue until their heads spin.

Many presidents have used diversion as a communications tool, of course. It can be helpful in changing the national focus and framing issues in terms more favorable to their administration.

President Trump’s innovation may be to combine a willingness to make claims that are far from rock-solid – and at times demonstrably false – with the reach and repetition inherent in social media, and the accelerated news cycle that social media feeds. The resulting distractions provide talking points for his supporters, crowd out news that’s negative to his administration, and generally leave voters confused and even uncertain as to whether objective truth about the subjects in question exists.

“It’s a go-to strategy for Trump to point elsewhere when things go wrong and make a song and dance about it,” says Dominic Tierney, professor of political science at Swarthmore College.

An ability to seize the national agenda

Throughout his tumultuous time in office, President Trump has shown an ability to again and again seize the national agenda and direct it where he wants, with a tweet, a press conference, or an off-hand comment as he strides toward his Marine 1 helicopter.

Last July, for instance, as special counsel Robert Mueller prepared to testify before Congress, the president unleashed a series of tweets criticizing four Democratic congresswomen of color, among other things calling them “a very Racist group of troublemakers.” Unsurprisingly, the tweets received a large amount of news coverage.

More recently, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other Democrats have accused him of trying to draw attention away from the federal government’s COVID-19 testing failures by suddenly announcing a suspension of legal immigration, and by tweeting support for protests calling for the reopening of state economies.

During the novel coronavirus crisis, President Trump has been an “agent of distraction,” said Speaker Pelosi on April 22.

This week, the president has been railing about former President Barack Obama. Last Sunday – a day he tweeted or retweeted others 126 times, the third highest daily total during his time in office – President Trump accused his predecessor of undermining his administration by manipulating the “deep state” to falsely accuse former Trump national security adviser Michael Flynn of criminal behavior.

On Thursday, President Trump on Twitter urged the Senate to call President Obama to testify. “If I were a Senator or Congressman, the first person I would call to testify about the biggest political crime and scandal in the history of the USA, by FAR, is former President Obama. He knew EVERYTHING,” President Trump wrote. “No more Mr. Nice Guy!”

Asked about the president’s tweet, Senate Judiciary Chairman Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., told Politico: “I don’t think now’s the time for me to do that. I don’t know if that’s even possible.”

Senator Graham added: “I understand President Trump’s frustration, but be careful what you wish for.”

In its latest iteration, the “Obamagate” theory centers on “unmasking.” Under the law, U.S. intelligence redacts the names of American citizens caught on wiretaps communicating with foreign officials who are espionage targets. But top officials can ask that the name of the American in the conversation be “unmasked.”

Republican senators on Wednesday released a list of Obama-era officials who requested during the transition period to unmask a name that turned out to be Mr. Flynn. The list of officials includes then-CIA director John Brennan, and Vice President Joe Biden.

Some Republicans immediately offered the list as proof that Mr. Biden was part of a “setup of General Flynn” that enmeshed the incoming Trump team in a “Russia collusion hoax.”

But unmasking is common – the National Security Agency has dealt with 10,000 to 17,000 such requests annually in recent years, including under the Trump administration. The officials making the requests would presumably not have known the name of the U.S. citizen in question in advance.

And some of the unmasking requests came at a time when the sitting administration was growing increasingly concerned about contacts between the Trump team and Russian officials. It’s possible that some requests dealt with a phone call from a U.S. citizen to Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak, in which the American asked that Russia not respond to new Obama administration sanctions imposed as punishment for Moscow’s interference in the 2016 U.S. election.

Since the anonymous American’s call sought to undercut the foreign policy of the sitting U.S. president, the officials involved in making that policy might well have been interested in that person’s identity – which was Mr Flynn.

Turning to another subject, on Mother’s Day President Trump also speculated on Twitter that MSNBC anchor Joe Scarborough might have killed someone. “Did he get away with murder?” the president’s tweet read, in part. “Some people think so.”

Mr. Scarborough and his wife and “Morning Joe” co-host Mika Brzezinski have long been one of the president’s favorite foils. Mr. Scarborough was a GOP congressman from Florida in the late 1990s, and the murder reference stems from the death of a young female aide in his district office.

At the time, Mr. Scarborough was in Washington, not Florida. Authorities determined after an investigation that she died after losing consciousness due to a heart condition and falling, striking her head on a table.

The circumstances prompted conspiracy theories, according to a 2017 Washington Post investigation, which concluded: “no foul play was suspected, and her death was ultimately ruled an accident by the medical examiner.”

‘Distraction is Politics 101’

President Trump is far from the first chief executive to try and drive public attention away from subjects that are politically sensitive.

“Distraction is Politics 101. At some level, this is just woven into the fabric of how leaders operate around the U.S. and the world,” says Dr. Tierney.

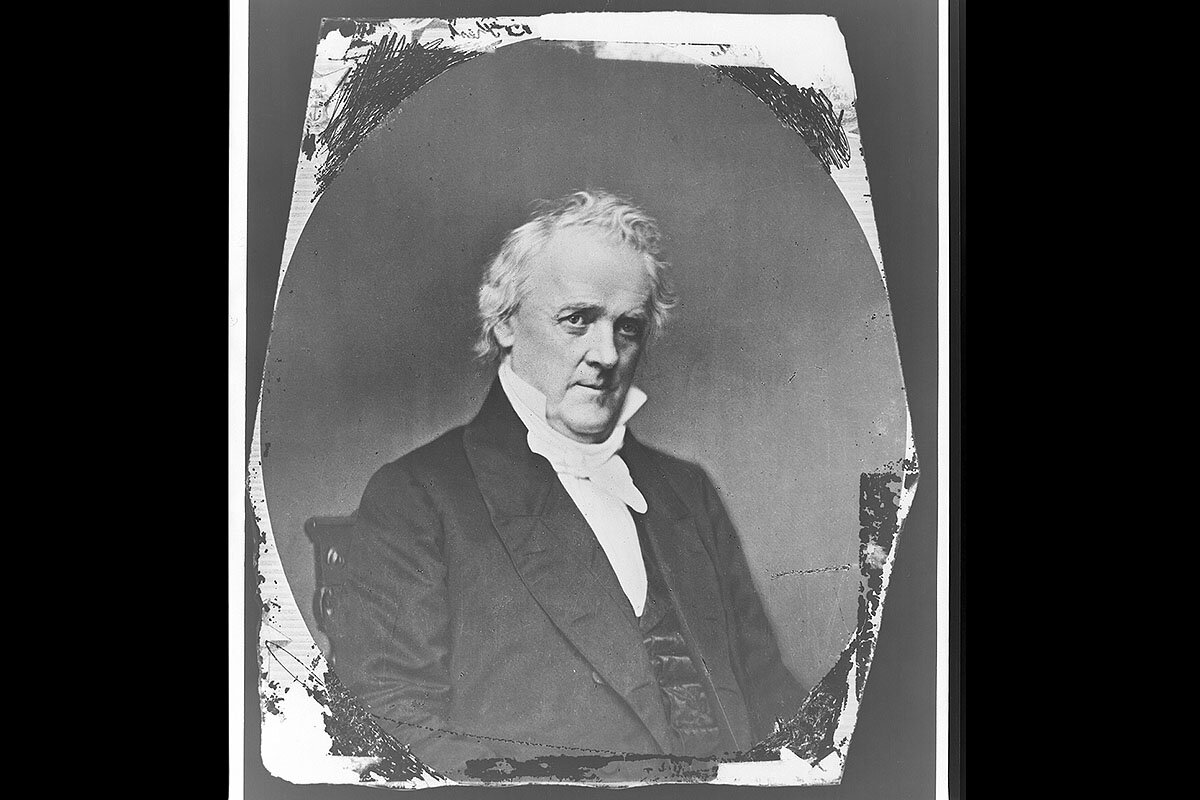

Prior to the Civil War, President James Buchanan tried to distract voters from the national schism over slavery by mounting a federal expedition to subdue Mormons in Utah, who were then resisting U.S. rule.

“I believe that we can supersede the [abolition crisis] with the almost universal excitements of an Anti-Mormon Crusade,” adviser Robert Tyler wrote in an 1857 letter to Buchanan.

This worked – briefly. But the Mormons and the feds struck a compromise, and the struggle over slavery known as Bloody Kansas loomed again.

In a more modern example, President Lyndon B. Johnson in early 1966 was eager to distract Americans from upcoming Senate hearings he knew would be critical of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

On the spur of the moment, LBJ flew with much of his Cabinet to Hawaii for a quick conference on improving South Vietnamese domestic conditions. This was a brief success, but the Senate hearings, held by Sen. William Fulbright of Arkansas, went on for years. In that sense, the Hawaii jaunt did little to affect overall public opinion. Distractions, almost by definition, can only last so long.

Tweets are short, pandemics are longer

That may prove true even in the current political and social American environment.

On the one hand, President Trump commands an instant audience that would be the envy of LBJ – indeed, the envy of any previous Oval Office occupant. His tweets are retweeted by millions of followers and covered, and thus amplified, not only by Fox News but also CNN and the New York Times.

The conservative media network consisting of Fox, Rush Limbaugh, and others is something that Republican presidents like Richard Nixon could only have dreamed of as a means to project their points of view.

But like LBJ, President Trump may find that while his attempts to raise different subjects may work for a period of time, the underlying national conditions persist longer.

The president’s distraction attempts have been much less effective during the pandemic, says Vanessa Beasley, an associate professor of communications studies at Vanderbilt University who studies presidential rhetoric.

“COVID-19 has presented a unique rhetorical challenge to President Trump,” she says via email.

He’s no longer able to point to the strength of the economy, she says. Most of his political rivals have gone quiet. The virus itself can’t be tweeted away. And he himself has taken the stage for lengthy briefings.

“If, before COVID-19, he was always asking us to look elsewhere in times of trouble, right now he is inviting us to look directly at him,” Dr. Beasley says.

That will probably reassure his strong supporters, she says. But the experience of recent weeks has shown it also has rhetorical costs, especially when he speaks about medical treatments and their efficacy.

“If he is counting on his presence to calm viewers and distract them from the costs of COVID-19, it is not clear that this strategy is effective,” she says.

Precedented

National unity during crisis? Look to lessons from WWII.

We may remember World War II as a period of patriotism and solidarity. But the years leading up to the war were marked by deep social and political rifts that may sound familiar today. As we again face the threat of a deadly – if faceless – enemy, what can we learn from the last time Americans banded together to confront a crisis? Here’s the fourth installment of “Precedented,” a video series about how history can help us understand today’s issues.

National unity during crisis? Look to lessons from WWII.

For ‘grandfluencers,’ age isn’t a social media hindrance – it’s a hook

Amid the coronavirus lockdown, older people have widely been seen as something to be shielded from harm. But thanks to social media, some are also offering their experience as voices of authority and positivity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

In the Instagram Live show #CuarenTata, 95-year-old Luisa Cantero Sanchez, better known as Tata, reads haltingly off a script welcoming viewers. She and Miguel Ángel Muñoz, her great-nephew and co-star, then begin chatting and laughing, the love the two share emanating from every interaction.

Tata is one of many figures of advanced age to become a social media sensation lately. Indeed, while older people have often been portrayed as vulnerable, weak, or lonely during the pandemic, they have also become examples of life and resilience.

Mr. Muñoz moved in with Tata, who cared for him as a child, to care for her during lockdown. She lived through the Spanish Civil War and World War II, and has authority about how to endure hardship.

For her part, she has said he has helped her tolerate this time of isolation. When he puts on the red flamenco dress and a blond wig, she erupts: “You kill me with your youth!”

“You have no idea how much happiness you bring to my life,” writes one viewer. “You and Tata are a paragon of love, and you, Miguelito, are a huge example of how we should be with our elderly.”

For ‘grandfluencers,’ age isn’t a social media hindrance – it’s a hook

She’s not your typical social media influencer. But in atypical times under strict quarantine, Spain has turned to Luisa Cantero Sanchez, better known as “Tata,” for their dose of daily escape.

“I’m 95 years old, and I’ve adopted technology to help us stay in our houses to fight the coronavirus,” reads her Instagram profile, which has attracted more than 106,000 followers since the show #CuarenTata began this spring. Each afternoon, she and her millennial great nephew, the Spanish actor Miguel Ángel Muñoz, do an Instagram Live together, dancing, singing, and laughing, and always holding a minute of silence for those lost to and fighting the pandemic.

In a recent episode – their 44th – she is dressed in a string of pearls and a flowery blouse and begins the show with a sign of the cross. Her nephew clicks a clapperboard, and Tata reads haltingly off a script, as she does every day, welcoming viewers. The love the two share emanates from every interaction, no matter how silly. When he dresses up as a flamenco dancer, her head goes back in laughter, and she takes out a handkerchief to wipe her eyes. The adulation comes pouring in. “This is the best part of my afternoon,” crows one Instagram follower. Another, in all caps, sums it up: “TATA, YOU ARE THE SOLACE OF SPAIN.”

Tata is one of many figures of advanced age to become a social media sensation lately. Indeed, while older adults have often been portrayed as vulnerable, weak, or lonely during the pandemic – the image of residents peering out of nursing homes will surely become iconic – they have also gained space as voices of authority, positivity, and resilience.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Many had become influencers before this, part of the age-defying movement, like the glamorous @baddiewinkle in the U.S., who has 3.8 million followers and whose Instagram profile reads “Stealing ur man since 1928!!,” or Taiwan’s stylish @moonlin0106. Others have attracted followers for simply sharing the quotidian routine of aging, from “Grandma Pat” in the U.S. to Geoffrey and Pauline Walker in the United Kingdom, who say they have received so many interview requests they declined this one. The couple today document their quarantine, from boiling noodles to putting out laundry. Recently, over 87,500 viewers joined them for tea and Victoria sponge cake.

One of the most famous grandmotherly figures to emerge in this crisis is “Nonna Rosetta” from southern Italy, who with humor and no nonsense doled out advice in a video that went viral. Sitting in her kitchen, the 87-year-old exhorted: “Suggestion No. 1: You have to wash your hands. Is this news?” she says, irked. “I’ve asked you so many times: ‘Did you wash your hands?’ Not because of coronavirus. Always.” It reached 23,000 people around the globe and was translated into English, Russian, Chinese, Portuguese, Romanian, and Spanish.

Renata Perongini, a writer with the Naples-based production company Casa Surace, which produced the video, says that although Nonna Rosetta is a comedic character, the woman behind her, Rosetta Rinaldi, is your typical Italian grandmother; Ms. Perongini has known her since she was a kid.

“By having Nonna Rosetta at home, in her kitchen, sitting on her chair, talking directly to the audience, we tried to share a message that is both serious and reassuring, to be truly listened to because you recognize Grandma has enough experience, and wisdom, to be listened to,” she says.

Shir Shimoni, a Ph.D. candidate focusing on representations of older people in popular culture at King’s College London, says that despite representations of positivism, health, autonomy, and even entrepreneurship by “grandfluencers,” there is a part of society that doesn’t want the responsibility, be it directly or via the state, to care for older people. She warns that the rise of grandfluencers may in part be a tacit celebration of those among the elderly – statistically the most vulnerable demographic in the pandemic – who don’t require society’s care. Still, she agrees today’s figures are “endearing, and even powerful; there is a sense of agency.”

And part of that lies in the intergenerationality at play. Mr. Muñoz, the actor, has told local media he moved in with Tata, who cared for him as a child, to care for her during lockdown. She was a cleaner for most of her working life, and lived through the Spanish Civil War and World War II, and has authority about how to endure hardship.

For her part, she has said he has helped her tolerate this time of isolation. In Episode 44, when he puts on the red flamenco dress and a blond wig, she erupts: “You kill me with your youth!” He takes her hands, and leads her to dance.

“You have no idea how much happiness you bring to my life,” writes one viewer as the improvisation plays out. “You and Tata are a paragon of love, and you, Miguelito, are a huge example of how we should be with our elderly. A huge example.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

On Film

Home theater: Comedies to lighten your lockdown

Need a laugh? From the Marx Brothers to Albert Brooks, these are films that get better on repeat viewing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Peter Rainer Film critic

Times and tastes may change, but funny is still funny, writes film critic Peter Rainer. He can think of few comedies that are better picker-uppers than the three highlighted for this week’s column. From the get-go, in their own very different ways, they take you to a better place and keep you there. “I’ve seen these films many times and, if anything, they improve with age,” he writes. “What was new the first time around becomes cherishable on repeated viewings.”

Home theater: Comedies to lighten your lockdown

It has always been my particular pleasure to champion older movies that might be discoveries for some and remembered treasures for others. This is especially true when it comes to comedies. Times and tastes may change but funny is still funny. I can think of few comedies that are better picker-uppers than the three I’m highlighting for this week’s column: “Tootsie,” “Lost in America,” and “Duck Soup.” From the get-go, in their own very different ways, they take you to a better place and keep you there. I’ve seen these films many times and, if anything, they improve with age. What was new the first time around becomes cherishable on repeated viewings.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

“Tootsie”

Dustin Hoffman had perhaps his greatest movie role to date in “Tootsie” (1982) as Michael Dorsey, a New York actor deemed so “difficult” by his agent (played to the hilt by Sydney Pollack, the film’s director) that he’s become unemployable. In desperation, secretly dressed in drag, he auditions for a soap opera and lands the part. As “Dorothy Michaels,” playing a hospital administrator, he becomes the star of the show, all the while keeping his real identity under wraps.

Gender-bending complications ensue, including his attraction to one of the show’s actresses, Julie, who warms to Dorothy as a confidante. Julie is marvelously played by Jessica Lange, who won the best supporting actress Oscar for this film in the same year that she was also nominated for best actress for her harrowing and polar opposite performance as Frances Farmer in “Frances.” And there’s Julie’s widowed father Les (Charles Durning), who is smitten with “Dorothy.”

The entire cast is tiptop, including Bill Murray as Michael’s playwright roomie, Teri Garr as Michael’s understandably frazzled girlfriend, and Dabney Coleman as the TV show’s lecherous director.

During its making, “Tootsie” was notorious for production problems on the set. Hoffman and Pollack were continually at odds (despite the film’s smash success, they never worked together again), and the script was worked over by many more writers, including Elaine May and Barry Levinson, than the two who were credited, Murray Schisgal and Larry Gelbart. Given all this dissension, one might reasonably have expected a disaster, and yet not only is “Tootsie” a classic comedy, but also, of all things, a seamless classic comedy.

It’s also unexpectedly touching. Michael’s disguised yearning for Julie pulls him apart. When the jig is finally up, he tries to calm her outrage by telling her, “I was a better man with you as a woman than I ever was as a man.” Hoffman gives a line that might otherwise sound sappy a deep wellspring of emotion. (Rated PG)

“Lost in America”

Albert Brooks, as performer, writer, and director, is one of the most original comic talents in the history of American show business. He came from a showbiz family, with a famous radio comedian father, Harry Einstein, who had the wit, or the chutzpah, to name his son Albert. His best movies as a director and co-writer are “Real Life” (1979), a deadpan satire about a supremely annoying documentary filmmaker who intrudes on a family’s privacy; “Modern Romance” (1981), where Brooks plays a supremely annoying film editor trying to win back his girlfriend (Kathryn Harrold); and his masterpiece, “Lost in America” (1985), where he plays David, a cocky Los Angeles ad executive who, denied a promotion to vice president, chucks it all, liquidates his assets, buys an RV, and with his doting, befuddled wife, Linda (Julie Hagerty), sets out on the road “Easy Rider”-style.

Things, needless to say, do not go as planned. One of the funniest scenes of all time comes right after Linda has lost their life savings at a Vegas casino. David frantically tries to convince the casino owner, played with impeccable slow-burn exasperation by Garry Marshall, to give the money back to the couple as a “bold” publicity gimmick. Perfection. (Rated R)

“Duck Soup”

Leo McCarey’s “Duck Soup” (1933) is the funniest Marx Brothers movie and also, in its own vaudeville-gone-haywire way, one of the best antiwar satires ever made. Groucho plays Rufus T. Firefly, the president of the embattled state of Freedonia, and Chico and Harpo play spies hired to undermine him. The brothers never worked better together, and at least one of their routines – the famous “mirror” scene where Groucho and Harpo mimic each other’s movements – is unmatched. (Unrated)

These films are available to rent on Amazon’s Prime Video, YouTube, Google Play, and iTunes.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

An overlooked answer to COVID-19

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Of all the responses to the coronavirus, one of the most overlooked by journalists and national leaders has been prayer. Yet take note:

On May 14, tens of thousands of Christians, Muslims, and Jews around the world held a day of prayer for healing. Or note a day of prayer held in Israel April 22 and one in the Philippines April 8 to address the virus crisis. In the United States, the National Day of Prayer, held every year on the first Thursday in May, focused this year on helping Americans cope with COVID-19.

In March, the number of Google searches with words like “prayer” and “God” skyrocketed in 75 countries. In addition, downloads of Christian apps for prayer and meditation have increased in the U.S.

Adversity often pushes people to search for answers through prayer. The individual problems may differ in type and scope, but the universal truths found through prayer can provide peace and calm to all. Those truths are eternal and accessible. For many during this pandemic, this is not a surprise. Perhaps they should not be overlooked.

An overlooked answer to COVID-19

Of all the responses to the coronavirus, one of the most overlooked by journalists and national leaders has been prayer. Yet take note: On May 14, tens of thousands of Christians, Muslims, and Jews around the world held a day of prayer for healing. It was sponsored by a newly formed interfaith group called the Higher Committee of Human Fraternity.

“Let us face this challenge with patience and composure,” said Indonesian President Joko Widodo at a mass prayer service in his Asian nation on Thursday. “Panic is half of the disease, equanimity is half of a cure, and patience determines recovery.”

Or note a day of prayer held in Israel April 22. Jewish, Christian, Muslim, and Druze religious leaders gathered online to lead people in their respective prayers. Or note a day of interfaith prayer in the Philippines April 8 to address the virus crisis.

In the United States, the National Day of Prayer, held every year on the first Thursday in May, focused this year on helping Americans cope with COVID-19. At the local level, interfaith groups have also held days of prayer – on Facebook, Zoom, or similar online platforms.

During the COVID-19 emergency, “Americans have become significantly more likely to say that religion is increasing its influence on American life,” according to the results of a mid-April Gallup Poll. A March survey by Pew Research Center found 24% of Americans say their faith has become stronger while 55% said they had prayed for an end to the spread of the coronavirus.

In March, the number of Google searches for words like “prayer” and “God” skyrocketed in 75 countries, according to economist Jeanet Bentzen at the University of Copenhagen. In addition, downloads of Christian apps for prayer and meditation have increased in the U.S.

Adversity often pushes people to search for answers through prayer. The individual problems may differ in type and scope, but the universal truths found through prayer can provide peace and calm to all. Those truths are eternal and accessible. For many during this pandemic, this is not a surprise. Perhaps they should not be overlooked.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

From loneliness to permanently companioned

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Martha Sarvis

Even in today’s interconnected world, loneliness is all too common, especially in light of widespread physical distancing efforts. But as a woman found when faced with recurring bouts of loneliness, the realization that God’s love and companionship are always present can heal lonely hearts and strengthen our relationships.

From loneliness to permanently companioned

Have you ever felt lonely? I know I have. With the recent requirements for physical distancing, many people are struggling with being alone for far too long.

Even before the coronavirus had entered the scene, Britain had started a successful campaign to pair volunteers with those experiencing loneliness. There are statistics indicating that the feeling of loneliness is on the rise in other places, too.

Genuine caring from another individual can lessen feelings of loneliness. But at times I’ve felt lonely even when loved ones are present. So what permanently fills the void?

I faced this very question last year when our son got married. My husband and I happily welcomed our new daughter-in-law into the family, but thinking about the changes to come brought feelings of loss. My son and his fiancée had a yearlong engagement with many joyful gatherings. But each occasion seemed to bring on bouts of loneliness for me. Sometimes it would come as not feeling accepted by the group, as kind as they were. Other times it was just emptiness or fears about the future.

For me, a key step has been realizing that, fundamentally, companionship isn’t a physical need but a spiritual one. And I’ve found the antidote is becoming more aware of our oneness with God. Christian Science explains that God is infinite and always present, and that our entire being is the expression of God’s qualities. Our relation to God is like the sun and its rays. God is the sun, and we shine forth, or reflect, His infinite light.

You can’t get any closer than that. The Apostle Paul puts it this way: “Neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God” (Romans 8:38, 39).

But how do we experience this oneness when loneliness seems overwhelming? It starts with prayer that affirms God’s presence and power, and our true nature as the expression of divine goodness and joy. This is not an intellectual process. It’s an opening of thought to God that surrenders a mortal, material sense of existence in favor of spiritual reality: the always-present power of God that is forever good and loving.

God is closer than our next thought, and His entire being is Love. As we read in the Bible, “Yea, I have loved thee with an everlasting love: therefore with lovingkindness have I drawn thee” (Jeremiah 31:3).

This spiritual reality is not some far-off ethereal wispiness. It is here now. “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the Monitor’s founder, defines “substance” in part as “that which is eternal and incapable of discord and decay. Truth, Life, and Love are substance ...” (p. 468). Truth, Life, and Love are Bible-based names for God. Divine substance is always present, and infinitely so. It is rock solid.

This idea of our dependable, substantial relation to God became my bedrock. Each time I turned to God in prayer, I would feel a reassuring sense of companionship and acceptance as God’s loved child. It was not a consolation prize or a feeling I was getting something that was second best. It was the best – a warm and fully satisfying sense of God’s presence and power.

Step by step it became easier to see that I could never truly be lonely. Praying to understand more of my oneness with God freed me from the fear of being alone. As I became more confident in God’s unwavering companionship, I became freer with my own expressions of caring because my happiness wasn’t dependent on acceptance or companionship in return. I realized I already had these and could joyously express love toward others. The bouts of loneliness stopped, and I have good relationships with family members old and new.

This feeling of loving companionship with our divine Father-Mother, God, is available to everyone. It satisfies the heart with permanent companionship and provides a more solid basis for our relationships with one another.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all the Monitor’s coronavirus coverage is free, including articles from this column. There’s also a special free section of JSH-Online.com on a healing response to the global pandemic. There is no paywall for any of this coverage.

A message of love

New training buddies

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when Howard LaFranchi explores what is being done to address the growing challenge of food insecurity around the world.