- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- For US-China groups, the adversary is COVID-19 – not a country

- Stay-at-home college? Campuses focus on finances, and survival.

- In Ahmaud Arbery case, unexpected advocates for racial justice

- An impossible comeback? The small New York shops trying to survive.

- Spring picture books that delight, inspire, and transport

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The other PPE to keep in mind as lockdowns lift

Today we look at U.S.-China relations at the human level, how colleges are rethinking their offerings, introspection after a Georgia killing, small businesses’ new realities, and picture books to enliven the little ones.

As lockdowns lift, public health officials stress that loosening – a complex process – should come with caution.

The world will still need an abundance of PPE – not the protective gear that’s been in maddeningly short supply, but the exhibiting of three constructive values. Some have already been displayed.

Pragmatism: In January, while some leaders floundered, others worked methodically. In India’s Kerala state, K.K. Shailaja, a science teacher turned health minister, convened a response team before her state of 35 million people had any confirmed cases of COVID-19, adopting World Health Organization protocols and keeping the outbreak manageable.

Practicality: Mongolia’s government was also proactive, advocating social restrictions as the coronavirus rampaged in parts of neighboring China. Measures as simple as hand-washing helped suppress infection rates, reports Global Press Journal, citing national health officials. (The country has also seen a sharp decline in other illnesses attributed to poor hygiene.)

Empathy: Examples of human kindness have flowed. But understanding should extend further. Persistent guidance can come without judgment, writes Harvard epidemiologist Julia Marcus in The Atlantic, though that can be a test when social behavior gets politicized – in both directions.

“[D]espite our best efforts,” Dr. Marcus writes, “some people will choose to engage in higher-risk activities – and instead of shaming them, we can provide them with tools to reduce any potential harms. ... Meet up outside. Don’t share food or drinks. Wear masks. Keep your hands clean. And stay home if you’re sick.”

A note to readers: We’ve been working on a refresh of the Daily, based on interviews with some of you. Watch for some design and format changes in Wednesday’s issue.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

For US-China groups, the adversary is COVID-19 – not a country

Global solutions can be personal. As China and the U.S. argue, we wanted to look at how groups of Chinese Americans are working to connect doctors, gear, and donors between the two countries.

The novel coronavirus has only heightened tensions between Beijing and D.C., as leaders try to deflect blame. There are valid concerns – yet some experts fear the chance for life-saving cooperation has been squandered.

While government face-offs continue, a wide array of American and Chinese organizations are stepping into the void, helping doctors and health experts learn from each other, donating protective equipment, and raising millions to support front-line workers. Those efforts are especially widespread in Seattle, where COVID-19 first hit the United States hard.

Major companies like Microsoft are pitching in, as are Asian-American civic groups and mom-and-pop businesses, at a time when many feel scrutinized.

“I’ve been in this country for 33 years, and I have never seen the Chinese community so mobilized, engaged, generous,” says Haipei Shue, president of the nonprofit civic engagement group United Chinese Americans. The reasons are many, but amid deteriorating U.S.-China relations, and a recent spike in anti-Asian racist attacks, some Chinese Americans feel a need “to prove they are as American as others. ... It is very upsetting and sad,” he says.

For US-China groups, the adversary is COVID-19 – not a country

As top Chinese doctors in Wuhan detailed best practices from their battle against the coronavirus, about 300 American health experts – including a dozen from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – listened intently by videoconference.

“During the early stage of the outbreak, you can … never imagine how the patients rushed the hospital,” Dr. Peng Zhiyong, intensive care unit director at Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, told the U.S. scientists, hospital chiefs, and public health officials.

It was mid-March. The United States had fewer than 50 COVID-19 deaths and 2,000 confirmed cases, a number that would soon balloon. China had been fighting the outbreak for months. But such direct information sharing between Chinese and American practitioners was unexpectedly limited, said organizer Li Lu.

“I was surprised,” said Mr. Li, the Seattle-based investor and philanthropist who arranged the event. Worsening U.S.-China tensions and a raging blame game over the virus between Washington and Beijing meant “two months of valuable experiences [from China] are largely lost in America,” Mr. Li told the group.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

When the world most needs to join forces against a common threat, the two superpowers, gripped by nationalist impulses, have squandered the opportunity to lead, analysts say. Instead they have “engaged in a deeply counterproductive rhetorical battle to see who can be more sanctimonious in blaming the other side,” says Jessica Chen Weiss, associate professor of political science at Cornell University.

President Donald Trump and Chinese leader Xi Jinping both face a domestic legitimacy crisis for failing to keep their people safe from the virus, and “are seeking to deflect blame onto a rival,” says Mira Rapp-Hooper, senior fellow for Asia Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Nevertheless, a wide variety of American and Chinese organizations and individuals are stepping into the void. Often behind the scenes and unreported, they are carrying out vital cooperation ranging from scientific exchanges and donations of protective equipment to financial and practical support.

“The virus doesn’t recognize political disputes, nor national boundaries … nor ideologies,” nor trade wars, says Mr. Li, chairman of Himalaya Capital Management. “With this virus we have now found a real worthy adversary.”

Groups ranging from corporations and mom-and-pop businesses to local governments and nonprofits are bridging the divide. They are also pushing back against a broader economic decoupling of China and the United States, advanced by some leaders in Beijing and Washington.

Many in both countries see decoupling as self-defeating. In the United States, they predict, such a policy could worsen internal divisions. “It would decouple Washington from the rest of the United States, because the rest of the United States is not ready to decouple from China,” says Scott Kennedy, a senior adviser on China’s economy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

More than 100 leading U.S. academics, executives, and foreign policy experts, including prominent Republicans and Democrats, signed an April letter urging a joint fight against the coronavirus, following a similar appeal signed by 100 Chinese academics. Despite rising competition and valid concerns on either side, “no effort against the coronavirus,” says the U.S. letter, “will be successful without some degree of cooperation between the United States and China.”

Fueling the frontline

Such goodwill initiatives are widespread in Seattle, where COVID-19 first hit the United States hard. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation helped fund China’s front-line responders and vaccine researchers as part of a global $100 million donation in February. Microsoft procured masks and other supplies for China, and in March enlisted China’s help to send stockpiles of protective gear to the Seattle area.

Early this year, Mr. Li started the Guardians of the Angeles Charitable Foundation, inspired by the death of Chinese doctor and virus whistleblower Li Wenliang, to help protect medical workers. The foundation has contributed $4 million in medical supplies to more than 100 hospitals in China, and has raised $4.5 million for a similar U.S. effort, donating to 60 hospitals in 13 states.

Chinese and American cities are also leveraging sister city relationships and other municipal ties.

In Seattle’s waterfront industrial district, the fire department last month welcomed 10,000 respirator masks donated to the city by the coastal metropolis of Hangzhou.

“That’s a few weeks’ worth for the entire department, so the impact is big,” says Seattle Fire Department warehouse chief Sundae Garner, adding that the department had only one pallet left in stock.

Washington state has relied heavily on donations for protective gear, with 20% of N95 respirator masks donated, says J. Norwell Coquillard, executive director of the Washington State China Relations Council. The WSCRC’s new sister charitable organization handled the mask import from Hangzhou, overcoming major bureaucratic hurdles in both China and the United States, says Man Wang, director of the council.

Groups like WSCRC with ties in both countries have proven particularly proactive.

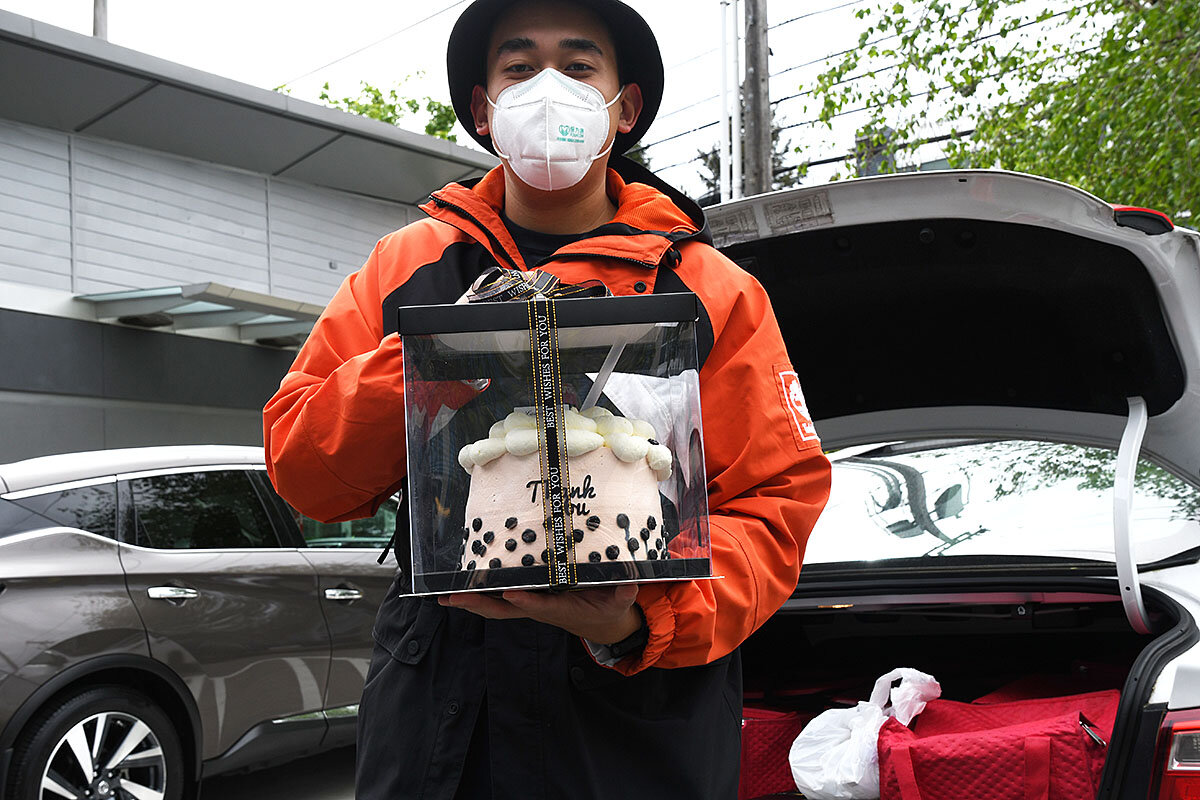

Seattle-based entrepreneur Lv Lili, head of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce in Washington state, spearheaded campaigns to donate medical supplies in China and locally. The chamber most recently helped launch a “#FoodWithLove” drive that has so far delivered more than 15,000 free meals to front-line health care workers and police in the Seattle area.

“I love this city, I love the people here, and I want the environment to be better,” says Ms. Lv, who arrived from China in 2014. The food is donated and prepared by 15 local restaurants and delivered daily by Chowbus to 26 hospitals, clinics, testing sites, and police stations. The goal is to raise donations to pay for future meals, to help keep restaurants afloat.

“Everybody’s doing their best to help fight the coronavirus and get through this hard time, we’re just doing what we can,” says Liu Zhixiong, whose family operates Frying Fish restaurant in Bellevue. Despite suffering a 60% to 70% decline in business, Mr. Liu is donating hundreds of free meals to first responders. “They are doing something we are not brave enough to do,” he says.

Receiving 30 meals of spicy tofu and stir-fried green beans from Frying Fish one recent night, Bellevue police Capt. Robert Spingler calls the “#FoodWithLove” deliveries “pretty unprecedented.” “The officers really enjoy it,” he says. “The food will be gone in an hour or so.”

A similar scene unfolded at the University of Washington virology lab, where program coordinator Lisa Rider emerged from the around-the-clock COVID-19 test analysis facility to collect 50 meals and two ornate cakes from Chengdu Memory restaurant in Seattle’s Chinatown. “It’s been a godsend, particularly for people who are working the midnight shift,” says Ms. Rider, whose lab analyzes about 1,500 tests a day.

The Dolar Shop, a Chinese hot pot chain, is distributing 100 free meals to the public from its Bellevue restaurant and another 150 meals to hospitals and first responders each day.

Help across borders

Chinese Americans feel a special responsibility, says Haipei Shue, president of United Chinese Americans, a nationwide nonprofit focused on boosting civic engagement. “I’ve been in this country for 33 years, and I have never seen the Chinese community so mobilized, engaged, generous,” he says. The reasons are many, but amid deteriorating U.S.-China relations, heightened scrutiny of ethnic Chinese, and a recent spike in anti-Asian racist attacks, Chinese Americans feel insecure, he says, “like they have a target on their back.” They want to go the extra mile to help, in part “to prove they are as American as others. ... It is very upsetting and sad,” he says.

United Chinese Americans of Washington (UCAWA) rallied 65 local organizations to obtain protective gear for China, then pivoted to do the same for Seattle, while raising $140,000 for EvergreenHealth Foundation in Kirkland, the first U.S. epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic.

“We are clearly living in an interconnected world, and the pandemic calls for more international cooperation,” says Hong Qi, secretary of UCAWA. “We don’t feel like the government and public officials should ... play the blaming game,” says Ms. Qi, who arrived in Seattle 30 years ago and has worked as a civil servant promoting election participation.

The sheer human suffering should compel the United States and China to rise above their differences, says Mr. Li, who has overcome his share of adversity. Having survived Mao Zedong’s radical Cultural Revolution and the massive 1976 Tangshan earthquake, he emerged as a student leader in the 1989 Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests. After the military crackdown, he escaped China for the United States, where he is now a successful hedge fund manager, and last month was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

“No matter what happens on the level of the two governments, if you feel the pain, people on both sides, you [do] what you ought to do,” says Mr. Li, who describes himself as “100% Chinese and 100% American.”

A popular line from Chinese poetry expresses it best, he says: “Though mountains and rivers separate nations, together we share the same sky.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story misspelled Liu Zhixiong’s name.

As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Stay-at-home college? Campuses focus on finances, and survival.

Next, some institutional solution-seeking. Many colleges had been confronting financial issues even before the disruption of lockdowns. Now the coronavirus is forcing a rethink about delivering value. Can the uncertainty unleash innovation?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Sitting on a deserted campus, David Dooley, the president of the University of Rhode Island, reflects on what college will look like come August. “Any institution that is saying with any degree of confidence what the fall is going to be like, honestly, I think they’re whistling in the dark,” he says.

Even before the pandemic arrived, colleges and universities in the United States were under stress from declining government support and rising skepticism about the value of a college degree. Now they face a perfect storm of economic downturn: less state support, financially needier students, and quite possibly a shrinking freshman class.

So far in 2020, eight colleges and universities are merging with others or closing, with several citing the pandemic as a complicating factor. Dozens more are expected to close in the next few years.

But the economic challenge that’s forcing difficult cuts on college campuses has also unleashed in places a furious bout of innovation as schools rethink higher education and its delivery to students in the 21st century.

“We are ready to change,” says Lynn Pasquerella, president of the Association of American Colleges & Universities. “I am confident the system will come out stronger.”

Stay-at-home college? Campuses focus on finances, and survival.

In any other year, the University of Rhode Island in Kingston would be bustling. Now, due to the pandemic lockdown, it’s deserted. Students are at home; classes are online; buildings are closed.

A security guard on a bicycle makes sure even the new welcome center is shut tight by rattling its locked doors loudly. Uncertainty hangs heavily in the spring air.

“Any institution that is saying with any degree of confidence what the fall is going to be like, honestly, I think they’re whistling in the dark,” says David Dooley, the university’s president, sitting inside the welcome center in early May wearing a face mask. About the only sure thing is that URI – which in recent years has faced head-on the problems of running a viable university system – will be in the red. “We are anticipating that we will take a significant financial hit,” he says.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

It’s a reality for America’s more than 4,000 colleges and universities. Already under stress from declining government support and rising skepticism about the value of a college degree before the pandemic, these schools now face a perfect storm of economic downturn: less state support, financially needier students, and quite possibly a shrinking freshman class. So far in 2020, eight colleges and universities are merging with others or closing, including Holy Family College in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, and 174-year-old MacMurray College in Jacksonville, Illinois, both citing the pandemic as a complicating factor. Dozens more are expected to close in the next few years.

But the economic challenge that’s forcing difficult cuts on college campuses has also unleashed in places a furious bout of innovation as colleges and universities rethink higher education and its delivery to students in the 21st century.

“We are ready to change,” says Lynn Pasquerella, president of the Association of American Colleges & Universities. “I am confident the system will come out stronger.”

Financial balancing act

The pandemic-led lockdowns have already cost schools billions of dollars. To hold on to students for the fall, particularly those whose parents are suddenly unemployed, colleges and universities will have to hand out more financial aid. Unemployment will shrink the tax base for states, which in turn will have to cut support for state schools. Given all that, institutions are proving very reluctant to reduce tuition for the 2020-21 academic year.

“What I’m hearing is a hard ‘no’ on that front,” says Kevin Walker, founder and CEO of CollegeFinance.com, a website for students and parents.

One of the big uncertainties is whether states will allow campuses to open this fall and, if so, how many students will attend. Travel restrictions are likely to limit the number of international students coming to the United States. A survey of nearly 1,200 American high school seniors in late April found that 12% who had already made deposits no longer planned to attend a four-year college full time, according to consulting firm Art & Science Group. And two-thirds said they expected to spend “much less” tuition if colleges went all-digital in the fall. Already, some students are suing schools to get tuition refunds for the spring because the all-digital classroom didn’t measure up.

But schools may get some help on that front. The same travel restrictions and economic hardships that might keep students from attending school also limit their alternatives, such as getting a job or deferring enrollment.

Lily Nguyen, a high school senior in Waltham, Massachusetts, had planned to take a gap year if her school of choice, the University of Massachusetts Boston, went all-digital for the fall. But foreign travel restrictions put an end to her plans to volunteer in Spain or South Korea. Even if UMass Boston is just online, “I think I will still be attending classes,” she says.

A time to innovate

In spite of the cuts, and sometimes because of them, schools are innovating to make themselves more attractive to students.

Some colleges and universities, which this spring had a crash course in online teaching, are hard at work trying to improve the digital experience. Last week, the nation’s largest four-year public university system – California State University – announced it would move almost all its classes online this fall.

Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU), a leader in online education for adults already in the workforce, has a third of its faculty working this summer to reimagine its curriculum for its 3,000 on-campus undergraduates. The goal is to bring tuition down for these students from $31,000 a year to a breathtaking $10,000 in order to make higher ed more widely available to people who can’t afford it. The plan, hatched last October, was supposed to be phased in over three years starting in 2023. But the pandemic-led downturn has pulled forward the timing to begin the transition in 2021.

To attract freshmen for this year, the school in Manchester is offering free tuition to everyone willing to spend one year with the current curriculum before moving to the revamped courses the following years. To bring tuition down, SNHU is considering, among other things, doubling the number of on-campus students; melding online instruction, some of it prerecorded, with face-to-face interaction with full-time faculty; and emphasizing experiential learning. For example, instead of engineering classes, the faculty might assign teams of students to work on a real-world project for a company and monitor their mastery of skills.

And the key to attracting students to a more digital model might not lie in the delivery of academics but in the social supports that surround them, says the university’s president Paul LeBlanc. “For our adult learners, our secret sauce is … the way we deploy advising,” he says.

For years, advisers have been working closely with the school’s 135,000 online students, checking in, encouraging, and sometimes becoming confidants about problems at work or with family, he says. The school is now having to think through how to deliver more online supports for traditional undergraduates, who will probably have more of their curriculum delivered online. That means rethinking the mundane, like offering computer help at 2 a.m., as well as the more difficult emotional areas of connectedness and motivation.

Attending college represents academic advancement, but it also involves coming-of-age experiences from friendships to clubs and sports to parties, Dr. LeBlanc says. “When [students] say, ‘I don’t want to do online,’ part of it is they’re grieving the loss of this” social side. If the school is to succeed with these students with far less face time, “they need to know someone cares that they’re doing their work.”

Miami Dade College in Florida – one of the nation’s largest colleges, with a student population that is 70% Hispanic and 44% below the poverty line – is gearing up for a surge in enrollment, which typically happens during economic downturns. Since announcing it would hold all its summer courses online, students are rapidly signing up. One of its new offerings is pandemic-inspired. “We are in the process of developing a contact-tracing curriculum that we hope to launch in the next couple of weeks,” says Lenore Rodicio, the school’s executive vice president and provost.

Fast-tracking tech vision

Further north, at the University of Rhode Island, Dr. Dooley is toying with the idea of a major based on managing pandemics. He says the crisis has accelerated the university’s move to a 24/7 learning environment supported by technology, where, for example, students might take in a professor’s lecture at their convenience – 7 p.m. or even 3 a.m. – rather than in class at a specified hour.

“We have more faculty than ever who are interested in learning how to do that,” he says. “That enables students to progress to their degree in a time frame that they have a lot of control over – and that isn’t just all tied up in what we recognize is a rather arbitrary 15th century academic calendar.”

URI has experience with surviving tough times. When he arrived on campus as president in 2009 – in the depths of the Great Recession – Dr. Dooley set the faculty to work on revising its general curriculum and doubled down on an initiative already in place: a laser focus on student achievement. One innovation was that courses were revamped so that any general education class counted toward the requirements of any major, so a student in political science could transfer to engineering without wasting any credits.

The results: Undergraduate enrollment is up from under 11,000 to about 14,600 today. Average time to graduate has declined from more than five years to 4.2. Support from the state legislature has moved from $58 million to about $84 million. The pandemic will likely change that, but Dr. Dooley says the goal is the same: focusing on student success.

“We simply could no longer afford the notion, which public institutions had long operated under, that we’re here, you can come and you sink or swim,” he says. “Instead, the notion needs to be: If you choose to come to us, our mission is to do everything we can to help you succeed.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

In Ahmaud Arbery case, unexpected advocates for racial justice

National narratives around race don’t change easily. But the moral clarity emerging after the killing of a black jogger in Georgia may be a defining moment for conservative ideals and racial justice. Our reporter explores why.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Something unusual has happened in the aftermath of the Feb. 23, 2020, shooting of Ahmaud Arbery: The entrenched political lines around Black Lives Matter cases have not held. Conservative voices – particularly in Georgia government – are joining the chorus calling for justice.

Georgia Sen. Kelly Loeffler, a Republican, came out early to condemn the killing, calling for justice for Mr. Arbery. She was joined by a chorus of major conservative voices, including some prominent evangelicals. While some think it’s too soon to say the national narrative has shifted, some black Georgians interviewed welcome white conservatives stepping off the sidelines.

“Black people in this nation have spent more time in involuntary servitude than in freedom if you add it up over time,” says James Yancey, a Brunswick attorney, who is African American. “It didn’t get that way overnight and it’s not going to change overnight. It will have to come down to a divine change from the hearts of people.”

White people, including evangelical Christians, speaking up for that change is important, he says. “Words have meaning. Words mean something.”

In Ahmaud Arbery case, unexpected advocates for racial justice

Ben Davis is a self-described Christian conservative and a strong supporter of Second Amendment rights. He also believes citizen arrest laws have solid roots in common law.

The one-time campaign chief for former Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach is also a former long-distance runner.

And what Mr. Davis saw in the video showing the killing of Ahmaud Arbery, a black runner in Brunswick, Georgia, was jarring.

To him, the video offers moral clarity, and he says that standing up publicly for a fellow runner’s constitutional rights doesn’t negate his conservatism.

“It seems like conservatives are always kind of Johnny-come-latelies with some of these really important issues, instead of speaking imaginatively about how being conservative applies to the whole sphere of public and collective life together,” says Mr. Davis, who wrote an Op-Ed about the shooting for The Wichita Eagle newspaper in Kansas. “Many say, ‘Oh, this is just a leftist issue so we’re going to sit very comfortably in our own little narrative. We’re going to wait it out and keep ourselves silent.’

“I think that’s wrong.”

Something unusual has happened in the aftermath of the Feb. 23, 2020, shooting of Mr. Arbery: The entrenched political lines around Black Lives Matter cases have not held. Conservative voices – particularly in Georgia government – are joining the chorus calling for justice.

Mr. Davis and other conservatives see the killing of Mr. Arbery – in which armed white men in a pickup truck chased down a black man wearing shorts and sneakers – as a defining moment for conservative ideals and racial justice.

“To see someone killed before one’s very eyes is horrifying, but ... there’s also a sense of weariness and lament that I find in the country after so many cases of this sort of horror happening,” says Russell Moore, author of “Onward: Engaging the Culture Without Losing the Gospel.” “There may be some ambiguities about some of the questions here, but there certainly is no ambiguity about the end result: that private citizens do not have the authority to kill someone. There’s just not a Christian justification nor an American justification for this sort of action.”

A consensus across party lines

While some think it’s too soon to say the national narrative has shifted, some black Georgians interviewed welcome white evangelicals stepping off the sidelines.

“Black people in this nation have spent more time in involuntary servitude than in freedom if you add it up over time,” says James Yancey, a Brunswick attorney, who is African American. “It didn’t get that way overnight and it’s not going to change overnight. It will have to come down to a divine change from the hearts of people.” And white people, including evangelical Christians, speaking up for that change is important, he says. “Words have meaning. Words mean something.”

Two months after a prosecutor deemed the chase and killing legal under the state’s self-defense and citizen arrest laws, two men – father and son Greg and Travis McMichael – were arrested on May 7 by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation on charges of assault and murder. A fourth prosecutor has now been assigned to the case. The Department of Justice is probing the incident as a possible federal hate crime. A judge denied bond.

The men say they were chasing a burglary suspect who turned violently on them. Mr. Arbery was shot three times at short range with a shotgun. The elder Mr. McMichael’s attorney said the facts will present a different series of events than the public has seen so far.

For now, the current picture “fits into the worst impressions that people have, that Georgia is still ‘Mississippi Burning’ – that this is still the 1950s, where lynchings take place,” says Charles Bullock III, a political scientist at the University of Georgia, in Athens.

Georgia Sen. Kelly Loeffler, a Republican, came out early to condemn the killing, calling for justice for Mr. Arbery.

She was joined by a chorus of major conservative voices.

“The time for being silent ended last week,” Republican Senate leader David Ralston told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr, also a Republican, said: “It’s important for people to know that Republicans value each and every human life. I think it’s important for everyone to understand that civil rights is not within the purview of any one party.”

The bipartisan outrage over the killing and how it was handled has jump-started a conversation about a Georgia hate crime bill that has passed the Republican-led House but has lingered in a Senate committee. A previous hate crimes law was voided in 2004, leaving Georgia only one of four states without such laws. Lawmakers may also revisit citizen arrest laws that one Glynn County prosecutor said protected the shooters from prosecution.

One of those supporting a probe into why it took two months to make an arrest is U.S. Rep. Buddy Carter, a Republican whose district includes Brunswick.

“The American people and the people in the First District especially need to be assured not only that justice is going to be done, but that they have confidence in the judicial system and law enforcement,” says Congressman Carter. “I think a reassessment is essential. As damning as that video was, we want to make sure that ... these guys get a fair trial. But, I mean, let’s face it: This should never have happened.”

Is this really a new narrative?

Some historians are critical of purported “new narratives” based on a singular exception.

“Some of the other cases have been more ambiguous in part because the victim’s character gets besmirched pretty quickly in the process, or because of the authority of the person doing the shooting,” says Andra Gillespie, director of the James Weldon Johnson Institute at Emory University in Atlanta, who is black. “But in this case you had an extrajudicial activity where the narrative quickly became an unarmed jogger gets shot by vigilantes. That was visceral and made this a clear black and white issue of right and wrong.”

Others caution that the outcry in this case may be more politically motivated than anything else.

“The outcry and the movement in the criminal justice system, in a lot of ways that’s a response to negative publicity that the local community and the state of Georgia is getting about ... a lynching,” says historian Carole Emberton.

But others see a difference this time – if of degrees.

Professor Bullock draws a parallel to the last American mass lynching, which happened in Georgia in 1946 when two African American couples were killed by a white mob at Moore’s Ford Bridge on the Appalachee River.

State and federal law enforcement poured in, but leads evaporated as the community closed ranks to protect the killers. The FBI investigation was finally and quietly closed a decade ago without any arrests. Historians point out that Georgia ranked second in numbers of confirmed lynchings through the Jim Crow era. There was no official recognition until 1999, when state officials erected a historical marker at Moore’s Ford.

“The governor-elect [in 1946], Eugene Talmadge, didn’t say anything condemning the lynching, and some people believed that the racist campaign he ran that year may have encouraged the lynch mob to think that there are no repercussions,” says Mr. Bullock.

But if the men who chased down Mr. Arbery believed the law and the community would protect them, adds Mr. Bullock, they were eventually proved mistaken.

A different kind of moment

For many white evangelical Christians, morality, race, and politics have long been wound into one tight cord through the South. The killing of Mr. Arbery has started a vigorous conversation within those Christian communities.

“If you think about Odetta’s song in the mid-20th century, ‘God’s Going to Cut You Down,’ speaking to the Klan and other white supremacist terrorists, the point of that song was to say that what you think is hidden will be ultimately revealed,” says Mr. Moore, president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention in Nashville. “That means that Christians have a responsibility to seek to walk in the ways of a just God, and to bear another’s burdens.”

What may also be happening now beyond condemning hate on moral grounds is an understanding that conservatives may lose more broadly when they don’t demand equal justice in cases of racist violence.

“Racial violence often becomes a bifurcated thing on a narrow set of issues,” says Mr. Davis, in Wichita. “The idea of institutional racism ... has always either been used as a weapon or as a way of sidestepping the issue entirely.”

This is a different kind of moment, he hopes.

“When there are real, clear instances of racism such as what we have here, we should collectively speak out,” says Mr. Davis. “This should not be tainted by political ideology. We can be unified with one voice, condemn it and learn from it, and mourn it as a nation. ... It’s got to be citizens leading the cultivation of virtue and a spirit of reconciliation in this country. It’s got to happen among the people.”

A deeper look

An impossible comeback? The small New York shops trying to survive.

We looked at college finances earlier. Here’s another case of the pandemic amplifying a long-running issue – the thin margins on which small firms run. Our report from New York highlights the resilience coming forward at the start of a critical summer.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By Hillary Chura Contributor

In a typical April at Pilates Reforming New York, 2,500 clients would be using special reformer machines, strengthening their abs and improving their balance. But this April, with the studios closed, owner Ann Toran instead conducted mat classes via Zoom. Just 433 clients joined in.

When Ms. Toran and her husband, Errol Toran, are allowed to reopen the studios, they doubt revenues will sustain them. The clients are not going to be thinking about exercise, Mr. Toran says. “They’ll be thinking about [their own] food and rent.”

Pilates Reforming New York is one of 230,000 small and midsize businesses in New York City. It’s unclear how many of these establishments have closed because of the coronavirus shelter-in, but anecdotal evidence based on a swath of Manhattan’s Upper East Side suggests it could be half. That mirrors national research that estimates COVID-19 has temporarily closed more than 40% of businesses.

But many businesspeople are hardly ready to give up. Take contractor Aaron Bloom. He wonders if potential clients will prefer hiring him because he was already sick with the coronavirus. “There’s reason to be hopeful,” he says. “That’s all I can do.”

An impossible comeback? The small New York shops trying to survive.

They’ve had no real customers since March. Bills are overdue, and landlords need money again. Savings are gone. Tens of thousands of small independent New York City businesses are hunkered down, trying to find a way through the most punishing economic calamity in generations. Many have already called it quits.

Unlike thousands of essential businesses in New York that have been limping through the coronavirus stay-at-home order, these nonessential shops have not opened their doors in two months.

While less populated areas of New York state began emerging from lockdown last Friday, city businesses know their rollout will be on pause for some time. Mayor Bill de Blasio said in early May that reopening the city “is a few months away at a minimum,” though last week he said nonessential businesses could begin opening in June if statistics continued to improve.

The timing is brutal. Spring is the busiest season for many of these shuttered businesses, and they need these months to carry them through the rest of the year.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

It’s unclear how many of New York’s small businesses have closed because of the coronavirus shelter-in, though anecdotal evidence based on a swath of Manhattan’s Upper East Side suggests it could be about half. That mirrors national research that estimates COVID-19 has temporarily closed more than 40% of businesses. And another 3% of restaurants and almost 2% of other small companies are permanently closed.

Operating in one of the most competitive, expensive, regulated, and taxed cities in the nation has long kept New York’s small-business owners up at night. Now these barbers, antique shop proprietors, and bookstore owners must become instant experts on public health, new government regulations, and still-evolving consumer psychology. There are other challenges: Six-foot distancing will mean a significant financial blow if businesses counted on crowds to survive. And loyal customers may want to shop local, but may ultimately ditch the 10-person queue to shop online at home.

New York City has some 230,000 small and midsize businesses selling just about anything that can be had, from handmade hats and custom acrylic furniture to sari material and sheet metal. The question now is how many of these specialty shops can survive. Even in a city of more than 8.3 million people, there’s only so much demand, given that unemployment could top 12% this year and layoffs are likely to extend through March 2021.

Thousands of local businesses – arguably the heart and soul of the city – may not survive the COVID-19 shutdown, says Jonathan Bowles, executive director of the Center for an Urban Future, an independent think tank. The first closures should be apparent by Aug. 20, when the city’s temporary ban on evictions is expected to end.

“It’s bad enough already, but unless these small businesses start making money soon, I just don’t know how they’re going to pay the bills,” Mr. Bowles says.

Even before COVID-19, many small businesses around the country were fragile and missed out on the decade-plus economic expansion. According to a new report by the regional Federal Reserve banks, 30% of firms with fewer than 500 employees last year were classified as “at risk” or “distressed”; 64% reported financial challenges during that time; and 86% said they would need to cut salaries, incur debt, or take other action if they missed two months of revenue.

Living month to month – pre-coronavirus

Karen Dixon and her husband, Essam Moussa, are among those entrepreneurs who are up against it. Long before the coronavirus temporarily closed their Upper West Side shoe store, The Shoe Tree, Ms. Dixon says they had been living month to month.

Generally, the middle of May would find The Shoe Tree packed with families, and the storeroom overflowing with some 400 pairs of shoes. On average, they’d tally 40 sales a day. Instead, the couple are cleaning their store, postponing deliveries, and hoping suppliers will have shoes whenever they reopen.

As in the rest of the state, businesses in the city’s five boroughs will roll out based on how essential they are and how much risk their opening would pose. Shoe stores and other retail are likely to be in the second wave of openings, after businesses like construction and manufacturing. Regardless of when The Shoe Tree returns, Ms. Dixon worries about whether parents will bring their children. She also fears a further push toward digital sales.

“People are sitting at home online, working, so they can order shoes for their children online and not come into the store. We have a big concern that our customers won’t come back. Situations like this really push consumers in that online direction,” says Ms. Dixon, who is also a furloughed soprano in The Metropolitan Opera chorus.

When the store reopens, she says staff will institute protective measures such as wearing masks and sanitizing their hands after each customer. She hopes new signs will strike the right tone between welcoming customers and reminding them that only a few shoppers will be allowed inside at once.

An elusive financial cushion

Spring is also a busy season for Pilates Reforming New York. Any normal April would have 2,500 clients splayed out on special reformer machines, strengthening their abs and improving their balance. Owner Ann Toran and her 18 instructors would be coaching the in-person classes at four studios seven days a week.

But by this April, the studios were all closed, and most instructors were collecting unemployment benefits. Using Zoom, Ms. Toran was conducting mat classes from her New Jersey home studio, but just 433 clients had joined in. They did isometric and floor exercises, rather than working out on a machine with pulleys.

When Ms. Toran and her husband, Errol Toran, are allowed to reopen the studios, they doubt revenues will sustain them.

“Even if we were ready to rock-and-roll the first day we could open, that’s not necessarily what our clients’ priorities will be,” says Mr. Toran, a chiropractor. “They’re thinking, ‘How do I survive?’ They’re not going to be thinking about exercise. They’ll be thinking about [their own] food and rent.”

Like many small New York City businesses, Pilates Reforming New York didn’t have a financial cushion, thanks to high salaries, six-digit annual rent, hefty taxes, red tape, reinvestment in the business, and small margins. In January, however, the year had been looking good: Lengthy renovations were done, and all four studios were running. Now the Torans hope to stay afloat by Zoom teaching, online professional development, and the sale of used equipment they no longer need.

They’ve also canceled leases on two underperforming studios, thanks to a so-called good guy (or gal) clause that lets tenants who are current on their rent pay a fee to quit their lease early. As for the two locations the Torans are keeping, they paid what they could on one and are hoping for the best with the other.

The view from Hell’s Kitchen

Perhaps no single group of businesses has been hit as hard by lockdowns as have restaurants. Estimates are that anywhere from 30% to 75% of the country’s independent eateries could fail before the economy recovers. Two-thirds of American restaurant workers had been laid off by mid-April, and at least 40% of restaurants were closed, according to the National Restaurant Association. Dine-in restaurant service is in the third of New York state’s four-stage reopening plan.

Hell’s Kitchen restaurateur Daniel Assaf closed on March 15, and he has no idea when he might reopen the dining room at his fondue and tapas restaurant, Kashkaval Garden. Unlike many local owners, he didn’t bother with takeout or delivery because he worried about the risk to staff. Yet from a financial standpoint, he knows he needs to reopen soon.

“Our chef is 59. I don’t want on my conscience that we opened too early,” says Mr. Assaf, who has bought masks, gloves, and cleaning supplies and is considering using ultraviolet lights to disinfect the restaurant each night.

He says he expects to bring back a skeleton crew for takeout, delivery, and grab-and-go appetizers and salads. The dining room will have less than half its former 60-person capacity. Mr. Assaf does have one suggestion – that the city allow restaurants to open outside dining areas on streets that have been closed during the pandemic and turned into pedestrian walkways.

Like most other restaurateurs, Mr. Assaf is underwater. He owes more than half of April’s rent, all of May’s, and another $50,000 to $60,000 to companies that provide food, wine, and linens – though they are all working out terms. Like colleagues across the nation, he says the Paycheck Protection Program needs to change so businesses can use more of the proceeds to pay landlords and suppliers, rather than just staff.

For some restaurants, the way through COVID-19 is to go out of business.

Lower East Side restaurateur Stefan Jonot says that of the 300 or so local restaurant owners with whom he’s in touch, 20% have either closed or are preparing to do so. As for his Les Enfants de Bohème, the dining room may not open until September or later. Even then, it would be at 40% of its former capacity – and revenues.

Mr. Jonot plans to open on a limited basis soon to sell family-style, heat-and-eat meals. Chicken and sides for four will run about $50. Mr. Jonot needs the proceeds to help pay expenses, though he says he is current on the rent, thanks to crowdfunding.

The importance of flexibility

For many establishments, the importance of flexibility has never been more apparent. Logos Bookstore, a quaint, old-fashioned bookshop on a quiet strip on the East Side, has been in business for 25 years selling greeting cards, CDs, puzzles, and books. Like many independent companies, it’s primarily a brick-and-mortar setup, but owner Harris Healy is trying to bump up its online exposure. This month, Logos launched a virtual children’s story hour on Mondays, and it’s planning a similar book club for adults.

“If you don’t have the right technology, you might as well throw in the towel. Everything going forward in the world is going to be tech,” says Mr. Healy, who sold about 40 books online in the past two months, compared with 500 in the store in a normal two months.

An online presence allowed the venerable Strand Book Store to reopen early. After having been closed for five weeks, this granddaddy of New York’s independent bookstores began taking online orders on April 25 – weeks before any bookstore in the state was allowed to resume limited operations for on-site customers.

Despite the daunting challenges, many businesspeople are hardly ready to give up – such as contractor Aaron Bloom, whose Brooklyn company is Uncanny Creations. He was sick with the coronavirus for three weeks in March and April. But in the coming months, he’s hoping to get jobs from homebound workers who want designated nooks (or walls) where they can Zoom and do other tasks. He figures if he can show he’s immune to COVID-19, potential clients may prefer hiring him.

“I recognize that this is not a scientifically proven claim yet, but there’s reason to be hopeful,” he says. “That’s all I can do.”

Editor’s note: The part of this story about Mr. Jonot's rent obligations has been updated.

As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Books

Spring picture books that delight, inspire, and transport

Lockdowns with children can inch from cozy to confining. Our writer plucks four lush books that can throw open the window of imagination.

-

By Augusta Scattergood Correspondent

Spring picture books that delight, inspire, and transport

Spring is for new beginnings, friendships, flowers, and sharing picture books. These four books are perfect for family reading, and for keeping kids entertained if you’re sheltering in place during the coronavirus pandemic.

Hello, Neighbor! The Kind and Caring World of Mister Rogers

By Matthew Cordell

Hands up if you remember the neighborhood’s clanging trolley? Mr. McFeely and his speedy deliveries? Or perhaps you were enticed by the fairytale world of Daniel Striped Tiger. In his new picture book, Caldecott medalist Matthew Cordell (Wolf in the Snow) reminds us of all the reasons we love Fred Rogers. He was adored during his TV career and now a new audience will discover him though books that tell his story. Enhanced by endnotes of fascinating facts from the neighborhood and his life, the book and its illustrations have the intriguing feel of turning pages in a family scrapbook. This lovely reminder of the quiet, compassionate television host is the perfect book to encourage children to talk about kindness, about sadness, and about acceptance. The publisher’s recommended age for “Hello Neighbor!” is preschool through third grade, but a wide audience of fans and soon-to-be-fans will appreciate this authorized biography of Rogers.

Lift

Written by Minh Lê and illustrated by Dan Santat

It's the job of young Iris to push the elevator buttons in her building. “Up or down, our floor or the lobby,” she takes to the task, shows pride in her work, eagerly awaits the ride. But when her baby brother takes over touching the buttons and her parents not only allow but encourage this insult, she feels betrayed. Then she discovers a different kind of lift button, one discarded by the repairman. This mysterious, repurposed button is a magic cupboard, Max’s boat, and Narnia’s wardrobe door all rolled into one. Now Iris can travel to places she’s only dreamed of. The story is funny, poignant, and exciting, and Dan Santat’s graphic-novel like illustrations beg to be looked at more than once. Youngsters ages 4 to 8 and every grownup who shares this special family story with them will love “Lift.” My favorite line? “After all, everyone can use a lift sometimes.”

My Best Friend

Written by Julie Fogliano and illustrated by Jillian Tamaki

Making a friend can be so sweetly uncomplicated when you’re skipping through the park or chalking sidewalks, and award-winning author Julie Fogliano and illustrator Jillian Tamaki’s new picture book celebrates the joy of a budding friendship. In “My Best Friend” (ages 4-8), two girls discover what fun it is to have a pal to sit with beneath a big tree or to turn your hands into quacking ducks together. The story plays out in muted greens and pinks that surprisingly pop right off the page. A pickle, a creepy hand made of leaves, shared strawberry ice cream – such perfect details make this a lap book to enjoy and read again and again. Watch for a surprising turn in the end that will make both reader and listener smile.

Follow the Recipe: Poems about Imagination, Celebration, and Cake

Written by Marilyn Singer and illustrated by Marjorie Priceman

This picture book (ages 6-11) of culinary advice and clever tips is just the thing for budding poets and imaginative cooks. But instead of actual recipes for cake, cookies, or kohlrabi, award-winning author Margaret Singer offers exuberant pages brimming with words to savor. Marjorie Price’s illustrations are the perfect complement to this collection of both free verse and traditional poetry. Turn the pages and imagine spring asparagus as “grand marshals leading the parade of green” and hear the plink-plink-plink of shelling peas. Read “Follow the Recipe” once for the poems, return for the whimsically delightful illustrations, and come back when you need a bit of sage advice. A book to dip into more than once, to relish, or to share with a friend, this one goes nicely with a plate of fresh-baked cookies.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

In Afghanistan, peace starts in democratic unity

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a pivotal step toward peace in Afghanistan’s long war, the country’s two leading politicians signed an agreement Sunday that ends a feud over who won a flawed election eight months ago. President Ashraf Ghani will retain his office while election rival Abdullah Abdullah will head up talks with the Taliban and appoint half of the new government’s cabinet.

The deal to share governing responsibilities is itself a tribute to how many Afghans view power differently than the Taliban militants trying to impose their will through guns. It was mediated over months by a number of respected Afghan leaders who persuaded both men to put the country’s interests ahead of their personal ambitions, especially during the struggle against the coronavirus.

Peaceful consensus-making is now a norm in Afghanistan’s maturing democracy. “The knot that can be opened with hands should not be opened by teeth,” wrote one group of female political figures about their efforts to mediate the new power-sharing agreement. That sentiment is certainly in need given the continuing brutality of the war, such as the recent terrorist attack on a maternity ward in Kabul.

In Afghanistan, peace starts in democratic unity

In a pivotal step toward peace in Afghanistan’s long war, the country’s two leading politicians signed an agreement Sunday that ends a feud over who won a flawed election eight months ago. President Ashraf Ghani will retain his office while election rival Abdullah Abdullah will head up talks with the Taliban and appoint half of the new government’s cabinet.

The deal to share governing responsibilities is itself a tribute to how many Afghans view power differently than the Taliban militants trying to impose their will through guns. It was mediated over months by a number of respected Afghan leaders who persuaded both men to put the country’s interests ahead of their personal ambitions, especially during the struggle against the coronavirus.

Peaceful consensus-making is now a norm in Afghanistan’s maturing democracy. “The knot that can be opened with hands should not be opened by teeth,” wrote one group of female political figures about their efforts to mediate the new power-sharing agreement. That sentiment is certainly in need given the continuing brutality of the war, such as the recent terrorist attack on a maternity ward in Kabul.

The Afghan negotiators were not alone. In March, the Trump administration threatened to withhold $1 billion in aid unless the two presidential contenders struck a deal. But the United States largely left it to the Afghan mediators in suggesting the details of an agreement.

With a deal in place, Afghanistan’s government may soon be ready for talks with the Taliban – not only because of its ability to speak with one voice but also with a legitimacy borne of this latest demonstration of democracy. The intra-Afghan peace talks were proposed in February under an agreement made between the U.S. and the Taliban but were delayed because of the political feud.

Ending more than 18 years of war with the Taliban will not be easy, especially if the U.S. decides to withdraw its troops without a final peace deal. But the more that the Taliban are shown the resolve of the Afghan people in improving their elected government, the more the group will need to compromise at the negotiating table. Even the two presidential contenders had to learn that lesson.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Goodness that’s never in short supply

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Dilshad Khambatta Eames

Especially at times like this, it can seem as if there just aren’t enough resources to go around. But as a woman found during a financially difficult time, the light of God’s healing, saving goodness and love shines on all of us.

Goodness that’s never in short supply

Challenging times like these may suggest that resources are finite and insufficient, or that some individuals gain while others are left out by chance or by lack of opportunity or access. The outlook can appear bleak, limited, and unfair.

A kinder, more gentle, and principled view is offered by divine Science, the law of God, which is rooted in the foundation of one infinite God, good. This God is the Mind, or intelligence, of the universe; and this Mind, which is also Love, is universal and impartial. Divine Love never compromises. It does not give to one and take away from another. It is the only real source of goodness and cannot be in short supply.

Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered Christian Science, writes: “Love, redolent with unselfishness, bathes all in beauty and light. ... The sunlight glints from the church-dome, glances into the prison-cell, glides into the sick-chamber, brightens the flower, beautifies the landscape, blesses the earth” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 516).

Infinite Love has no boundaries. And each of us is an idea of this Love, of divine Mind, reflecting the unending grace of God. As we begin to see that spiritual reality, we experience the very real dimension of spiritual sense. It’s as gentle and natural as the dawning of a new day. Here, dark predictions and limitations are displaced by divine light.

Some years ago, I moved to another country to go back to college. Before I left, a friend I deeply respected took my hand and said, “Love’s work and Love must fit.” I recognized this as a line from a hymn that describes the spiritual identity of man (meaning all of us). To me, it felt like a mother’s loving counsel, to bear in mind that I am God’s idea, child, or pure reflection. The hymn also describes our identity as God’s child this way:

Man is the noblest work of God,

His beauty, power and grace,

Immortal; perfect as his Mind

Reflected face to face.

(Mary Alice Dayton, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 51)

Embarking on this new adventure hadn’t been a rash decision. Yet things weren’t easy, to say the least. Although I had a reasonable sum of savings to last me a little while, it was limited. Things were uncertain, and I couldn’t work on a student visa. During one semester, everything seemed to fall apart.

But I had a strong conviction I could trust in God and His Christ, Truth, as my “good shepherd” (see John 10:11). I had faith to do God’s will, which could only reflect divine goodness. Divine Love was the “sunlight” nourishing me spiritually when I felt helpless and imprisoned by fear, bringing a conviction deep within me that Love’s gentle presence and power, constant and active, would guide and care for me.

As I looked for opportunities to serve on the college campus between classes and on weekends, I was offered a very modest but interesting position in the international student affairs office. My gratitude was boundless when, without my asking, the office applied for a work visa for me, which then opened up many avenues of opportunity to be of service to others.

It can be tempting to think that opportunities are dependent on circumstances or chance. But I’ve noticed that it is the supply of spiritual ideas from God – expressed in qualities such as compassion, kindness, love, cheerful willingness, confidence, trust, intelligence, generosity, humility, and joy – that uplift hearts. And they multiply, manifesting themselves in tangible blessings.

This experience is such a modest example, but it showed me something important. When the sun shines, it lights up the whole landscape. It doesn’t stop shining, and no one is left out.

This unity of man with God, good, is what Jesus saw so vividly, despite what appeared to be lack, limitation, disease. He understood God to be the true cause and substance of us all, and this spiritual understanding enabled him to heal so naturally.

God supplies us with spiritual ideas. These are infinite resources, and we’re made to express and share them with each other. We can all recognize the indivisible wholeness of our relation to God, limitless Mind, and experience renewed health, supply, harmony, and progress.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all the Monitor’s coronavirus coverage is free, including articles from this column. There’s also a special free section of JSH-Online.com on a healing response to the global pandemic. There is no paywall for any of this coverage.

A message of love

Here be dragons

A look ahead

Be well, and come back tomorrow. Taylor Luck is working on a story about how the pandemic has turned back the clock on Ramadan observances – and why that may be a welcome development.