- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Why the future of wealth looks very different

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

What does wealth look like? For most of human history, it looked a lot like shiny things that humans pulled from the ground. Wealth was built on natural resources, and if you didn’t have them, you went to get them elsewhere. This was fuel for colonialism and exploitation.

But a recent analysis by The Economist finds something interesting. Looking forward, wealth looks less like things we take from the ground. In fact, it doesn’t “look” like anything at all because wealth is increasingly built by better thinking. “As natural wealth is used up, economies will rely more on human capital,” the article states.

In many ways, natural resources can have a regressive effect. They still generate wealth, but in many countries that leads to vast inequities, with a corrupt ruling class hoarding that wealth. In Congo, for instance, colonialism has gone but its economic spirit lingers.

On the other hand, human capital – the wealth generated by innovation, education, and opportunity – has no such effect. Singapore’s significant wealth, for example, is in its people. Its gross domestic product is under no threat from declining natural resources.

For the world, a shift is underway as economies learn that extraction is not the only – or even best – way to grow. The Economist notes: “Financial capital tends to accumulate. Natural capital seems destined to do the opposite.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Next pandemic threat to economy: A wave of evictions

Government bans on evictions during the pandemic are expiring. That makes this moment a test of whether the U.S. can keep a health crisis from becoming a housing crisis.

-

By Richard Mertens Correspondent

-

Laurent Belsie Staff writer

Even in good times, 2 million or more households can face eviction in America in any given year. Low-income renters, especially, often scrape by on margins too narrow to absorb even modest difficulties. Now, the coronavirus pandemic, disrupting the income of legions, could create a tsunami of evictions.

Some states have seen temporary bans on eviction expire, and this week a federal eviction moratorium affecting about one-quarter of America’s rental properties is set to end. An estimated 11 million or more U.S. households may face eviction in coming months.

In Milwaukee, on the ninth floor of a downtown apartment building, Edward Smith was alarmed recently to get a notice that he owed more than $3,000 in rent. Mr. Smith, a disabled Army veteran and former paratrooper, says he fell so far behind because he had to pay funeral expenses for his father, who tested positive for the coronavirus.

“They said they’re going to be sending out eviction notices at the first of the month,” he says. “I told them I’ll try – if I can set up a payment program.” For renters in Wisconsin and beyond, a lot now rides on discussions in Congress about a new round of coronavirus relief for the economy.

Next pandemic threat to economy: A wave of evictions

The first of the month had come and gone, and now in early July the man with the clipboard arrived at the apartments on North Hopkins Street, a plain two-story brick building where grass and weeds grow scraggly along the street and broken furniture lies abandoned around the dumpster out back.

To tenants he was a figure of doom. On the second floor, he stuck a folded eviction notice in the door of Apartment 14, two units down from where Sorea Appling lived. It wasn’t long before Apartment 14’s tenant, and the woman in Apartment 5 downstairs, had found new places to live.

“They say once you get your door knocked on by the man with the clipboard, you might as well leave,” says Ms. Appling, a public school janitor who has been out of work since March and worries that she might be next.

Her worries are increasingly shared by renters across the nation. For several months during the coronavirus pandemic a combination of tenant grit, landlord forbearance, and federal aid has helped people stay in their homes. State or local bans on evictions have in many cases offered a reprieve.

Now those eviction bans are phasing out along with key government support for unemployed workers. With the economy far from recovered, some of the steepest declines in income have been faced by low-income renters like Ms. Appling. By some estimates, the United States could see more than 11 million households evicted in the next four months.

“People are going to go over a cliff,” says Mary Cunningham, a housing expert at the nonprofit Urban Institute, and co-author of a new analysis on the problem. “We’ve seen this coming. We’ve been racing toward it with the clock running out and, so far, Congress hasn’t responded.”

Analogies like “cliff” or “tsunami” are apt. As the Senate convenes this week to consider new coronavirus relief, a key question is whether the resulting bill will include provisions to help at-risk renters. The expiring supports – from the CARES Act passed by Congress in April – include an eviction moratorium for the roughly one-quarter of rental properties that get federal backing, plus supplemental unemployment benefits that have so far buoyed up millions of households.

Although some states have moved to extend eviction bans, the potential for mass evictions on an unprecedented scale looms.

Economists say such an eviction wave could deepen poverty, widen racial inequality, and create severe new damage to the economy that will take years to repair.

“The issue of inability to pay, poverty, and unemployment – that existed pre-COVID-19,” says Raphael Ramos, a lawyer with Legal Action Wisconsin and head of its Eviction Defense Project. “The difference between now and then is that the pandemic has shifted the line of poverty. There are more people at risk than before.”

“Not in 40-hour jobs”

Indeed, the coronavirus is amplifying a problem that has long festered in Milwaukee and other cities. Housing advocates say evictions are a symptom of a combination of chronic problems like low-paying jobs, too little affordable housing, and public transportation systems that are inadequate to take people to where the work is. Renters often scrape by on margins too narrow to absorb even modest difficulties.

“A good part of our clients are not in 40-hour jobs, but in a patchwork of jobs – babysitter, bus driver, hair cutters,” says Peter Koneazny, litigation director at the Legal Aid Society of Milwaukee, where calls from renters appealing for help have skyrocketed. “You have a lot of that. It’s a kind of constant struggle for many people. Their head is barely above water, most of them.”

Evictions are sometimes the result of cascading circumstances. Iyonna Hall-Davis was working as a certified nursing assistant in a Milwaukee suburb, often for 16 hours at a time, when she started having trouble with her car, an old 2007 Cadillac. Taking public transportation to work was “not an option,” she says. “No bus came near it.”

Her transportation troubles led her employer to cut her hours, and she fell behind on her rent, Ms. Hall-Davis says. At the end of February a payroll check that would have covered what she owed arrived late, forcing her eviction. She’s been struggling ever since, moving with her 3-year-old son among family and friends and waiting for her unemployment application to be acted on. She’s been waiting 10 weeks. She hopes to use the money to rent a new apartment and buy another car that can take her to work.

“Whenever that comes, I’ll get my life back together,” she says.

Options for Congress

To stave off the potential crisis, affordable housing advocates are pushing for one or more of the following from Congress: a comprehensive federal ban on evictions to replace the diminishing patchwork of protections currently in place, rental assistance for tenants affected by the pandemic, targeted help for landlords, continuation of the supplemental unemployment benefits at some level, and help for local governments, which are expected to be swamped by eviction notices once the moratoriums end.

Many of those provisions are in the HEROES Act, a $3 trillion package passed by House Democrats in May. Republicans in the Senate, however, say the Democrats’ measure is far too costly.

Some housing groups are optimistic Congress will act. “It’s brink negotiations,” says Bob Pinnegar, president and CEO of the National Apartment Association, which represents the rental housing industry. He expects an acceptable package will emerge.

Affordable housing advocates are more optimistic about local initiatives.

The “cancel rent” movement, for example, notched a victory recently when Ithaca, New York, passed a resolution calling on the state to cancel rent for residents and small businesses for three months.

Massachusetts is the latest state to renew a pandemic-related ban on evictions. Its moratorium, which had been set to expire in August, will now stretch through the fall, due to an order Tuesday by Republican Gov. Charlie Baker.

In Wisconsin, by contrast, a two-month ban set by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers expired May 26. That month, the Republican-majority state Supreme Court threw out Governor Evers’ coronavirus order as unconstitutional and mandated that new policies go through a legislative rule-making process.

Mr. Ramos and others saw evictions in Wisconsin jump 40% over the previous year in the first week after the state eviction moratorium ended. They are now running 14% higher than last year.

“There are a lot of people in this building who are under the threat of eviction,” says Ms. Appling, a slender woman with close-cropped blond hair and a silver crucifix around her neck. “Ever since March, these people haven’t been able to go to work.”

For families, wide ripple effects

Eviction has big ramifications for families. It makes it much harder to rent from other landlords, pushes families into substandard and more crowded housing, and has been shown to have negative effects on everything from physical and mental health to education for children who have to move from school to school, says Emily Benfer, a law professor at Wake Forest University and co-creator of the COVID-19 housing policy scorecard set up by the Eviction Lab, a research project at Princeton University in New Jersey.

Pushing people into more crowded, substandard housing is problematic anytime. Doing it in the midst of rising coronavirus cases makes the potential health fallout much worse, says Ms. Cunningham of the Urban Institute. “It’s really reckless during a pandemic to have people lose their housing when we’re all trying to socially distance.”

Evictions already hit people of color disproportionately. In Boston, a report last month from City Life and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that in nonsubsidized housing, more than a third of evictions happened in predominantly Black neighborhoods, even though only 18% of the rental housing was in those neighborhoods. That’s partly a result of poverty and low income, the researchers said, but the most telling predictor was the neighborhood’s racial composition.

In the pandemic, people of color are more vulnerable because they’re more likely to work the low-wage jobs most at risk during the pandemic, such as hospitality and retail positions, where people can’t work from home. And it’s not clear how many of those service jobs will come back as the economic recovery shows signs of slowing.

Among Americans in general, the problem of eviction is huge, affecting about 2.3 million households in a year, according to the Eviction Lab. In the next four months, the figure could hit more than 11 million, according to a new data analysis tool by global advisory firm Stout Risius Ross LLC.

In Milwaukee, on the ninth floor of a downtown apartment building, Edward Smith was alarmed recently to get a notice that he owed more than $3,000 in rent. Mr. Smith, a disabled Army veteran and former paratrooper, says he fell so far behind because he had to pay funeral expenses for his father, who died in May at a nursing home in the Chicago suburbs. Mr. Smith says his father, who was 90, had tested positive for the coronavirus. “I had to help bury him,” he says.

Mr. Smith, a tall, friendly man who wears an American flag face mask, says he talked to the building’s management after receiving the letter. “They said they’re going to be sending out eviction notices at the first of the month,” he says. “I told them I’ll try – if I can set up a payment program.” But he’s worried. He’s applied for rental assistance.

Lifelines in a storm

Wisconsin is spending $25 million of federal COVID-19 relief money to help tenants avoid evictions. The problem is that many renters don’t know about the assistance. And housing advocates wonder what happens when the money runs out.

In the meantime, many small landlords, too, are on the financial brink, unable to withstand a long-term dive in rental income. Yet some have shown leniency because of COVID-19.

“The mom and pop landlords are doing what they can to keep good tenants,” says Lisa Owens, executive director of City Life/Vida Urbana, a tenant advocacy group in Boston.

Ms. Appling, the school janitor, was astonished to hear from a friend that another landlord had forgiven tenants a month’s rent. Moreover, many landlords know that tenants can apply for rental assistance. They are willing to wait. But not all landlords are so lenient, and as Ms. Appling has observed, evictions can happen suddenly and ruthlessly.

She’s been spared, but only for now. Furloughed from her job on May 4, she’s been able to borrow enough from relatives to pay her $525-a-month rent. And yet there’s a limit to what she can borrow. She’s applied for unemployment benefits but has received nothing, even after months of waiting. She doesn’t know when she’ll be called back to work.

“I’m good for this month,” she says hopefully.

Laurent Belsie reported from Waltham, Massachusetts.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

As China tensions rise, Trump and Biden spar for ‘tough guy’ mantle

Both U.S. presidential candidates talk tough on China. But their paths forward are different. So here we offer a look at how each might confront Beijing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Howard LaFranchi Staff writer

Months after President Donald Trump declared the U.S.-China relationship “the best it’s been in a long, long time,” the administration has changed its tune. On Tuesday, for example, the U.S. ordered the Chinese consulate in Houston closed, even as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo praised Britain’s recent actions to counter an increasingly assertive Beijing.

No matter who wins in November, analysts say, the spiraling relations between the two superpowers are here for the foreseeable future. But that doesn’t mean that a Biden White House and a Trump White House would confront China in similar ways.

Mr. Trump may use sanctions more, while Mr. Biden would likely work more closely with Asian allies to counter Beijing. The two could also differ, experts say, on how they use international accords and institutions to challenge China’s vision of global governance.

But beyond how candidates respond to specific provocations from Beijing, some say China’s rise is forcing a reevaluation of America’s role in the world.

“What has changed in the last few years is that increasingly American public opinion sees us in a long-term competition with China,” says Mira Rapp-Hooper, of the Council on Foreign Relations. That shift extends to concern over “the way the world order will be governed.”

As China tensions rise, Trump and Biden spar for ‘tough guy’ mantle

On TV stations across the battleground state of Pennsylvania, President Donald Trump has been running ads that depict former Vice President Joe Biden as weak on China.

There’s a smiling Mr. Biden clinking glasses with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, and then there he is telling “folks” that “China is not the problem.”

Not to be outdone, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee has also been running ads in swing states blasting the president for going soft on China – in particular on the coronavirus pandemic. One ad reminds viewers that Mr. Trump initially praised Mr. Xi for the “very good job” he was doing to control the outbreak.

Whether or not the ads actually sway any voters is an open question. But what the effort of the two candidates to out-tough each other on China seems to suggest is that, no matter who wins in November, the spiraling relations between the two superpowers are here for the foreseeable future.

Mr. Trump may use sanctions more, while Mr. Biden is likely to work more closely with Asian allies to counter China, some experts say. The former vice president, who has said he has spent more time with Mr. Xi than any other foreign leader – and so has a clearer window into his motivations – is also likely to try to maintain good enough relations with Beijing to work on global issues like climate change.

But the deterioration in U.S.-China relations that some now compare to the Cold War is part of a broad geopolitical shift that actually predates Mr. Trump’s arrival at the White House, others say – and will continue no matter who occupies the Oval Office.

“The shift [to a more adversarial relationship with China] has been bipartisan – it just happened to coincide with the election of Donald Trump,” says James Carafano, vice president of national security and foreign policy studies at the Heritage Foundation in Washington.

“Democrats were already just as down on China as Republicans, it’s just that Trump’s rhetoric matched where the country was already headed,” he adds. “Any debate is pretty much over, to a point where skepticism on China is demonstrably bipartisan.”

Indeed, just months after President Trump declared the relationship with China “the best it’s been in a long, long time,” the administration has taken a series of steps signaling an adversarial approach to China. On Tuesday the U.S. ordered the Chinese consulate in Houston closed, even as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo traveled to London to praise recent British actions targeting China – and called for the U.S. and Britain to go further together to counter an increasingly assertive Beijing.

Beyond who sounds tougher on job losses to China, or the specifics of how each candidate might respond to Chinese military provocations in the South China Sea, some say the rise of China is essentially forcing a reevaluation of America’s role in the world that is likely to surface in a variety of ways in the presidential campaign.

“China is the first great-power competitor to arise since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and so as one result China poses the question for us about the type of 21st century great power we are going to be,” says Mira Rapp-Hooper, senior fellow for Asia studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

Upgrades ahead?

China has played small parts in some presidential campaigns, Ms. Rapp-Hooper says – as in 1992, when the U.S. response to China in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square protests surfaced in candidate debates.

What is new for this campaign, she says, is how widely China is viewed negatively by the American electorate. “What has changed in the last few years is that increasingly American public opinion sees us in a long-term competition with China,” she adds. That shift extends to concern over “the way the world order will be governed.”

Ms. Rapp-Hooper does not agree, however, that broad mistrust means China policy is largely precast no matter who wins the White House.

On two key fronts, how a Biden White House confronts China would likely differ significantly from the Trump approach, she says: One is how the U.S. interacts with its Asian allies, and the other is how the U.S. envisions its involvement in international accords and institutions as a means of challenging China’s vision of global governance.

Based on Mr. Biden’s foreign-policy track record, Ms. Rapp-Hooper says she would expect the former vice president not just to “repair” but to “set about to renovate the alliance system for the 21st century.” Part of such a renewed focus would be “creating new strategies and institutions within the alliances to respond to concerns in non-military domains” such as cyberattacks and disinformation.

Some former national security officials now aligned with the Biden campaign have speculated that Mr. Xi would prefer Mr. Trump to win based on the assumption that a President Biden would rebuild America’s alliances.

Yet while Mr. Trump may have been labelled the anti-alliance president based on his questioning of their relevance and demands they pay their way, Mr. Carafano says it’s simply not accurate to conclude that America’s alliances, particularly in Asia, are in disrepair.

“The people saying relations with our Asian allies need repair are ignoring reality on the ground,” he says. “Look at U.S.-Australia relations – never stronger. U.S.-Japan? Never stronger. India has never been closer to the U.S.,” he adds, “and as for U.S.-South Korea relations, they’re not in trouble.”

Not everyone agrees.

“The way you treat allies is so important, and here’s Trump telling South Korea ‘You have to pay even more for the troops we have there,’ but what does that get you, really?” says Lawrence Korb, a former assistant secretary of defense under President Ronald Reagan who is now a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress (CAP) in Washington. “We’re doing pretty much the same thing with Japan.”

Even if Mr. Biden wins the White House, just returning to where relations with Asian allies were four years ago won’t be the answer, U.S.-China experts say.

“A simple restoration won’t be enough,” says Ms. Rapp-Hooper, who has just published the book “Shields of the Republic,” which looks at how America’s alliances contribute to its security. “There is a huge alliance renovation agenda to be undertaken no matter who our next leader is.”

New realities

Beyond America’s alliances, Ms. Rapp-Hooper says she would expect a President Biden to “return to and try to renovate” a number of international institutions and accords that President Trump has abandoned, as a way of countering China’s emboldened efforts to impose its more authoritarian vision. Instead of quitting the World Health Organization and ceding it to China’s influence, for example, she would expect Mr. Biden to counter China from within.

Mr. Carafano agrees that international institutions have increasingly become the arena for powers like the U.S. and China to impose their values – but he says Mr. Trump has demonstrated an approach that differs from the post-World War II pattern.

“International organizations are no longer about establishing international norms,” he says, “now they have largely become places where great powers battle it out to expand their power.”

And whereas a President Biden would “want to be at every table” no matter the proven value of an organization, he says, President Trump would “continue to use the whole quiver” – sticking with useful forums, seeking to reform some, or leaving “hopeless cases” and establishing alternatives – to compete with China.

In any case, Mr. Korb of CAP says that whoever wins in November, simply squaring off against China and dividing the world into separate camps, like some new Cold War, won’t be an option.

“China has made it clear they’re not going to make the political changes we once thought we could encourage them to make, but that doesn’t mean we can just cut all ties to them given how intertwined our economies are,” Mr. Korb says. “We don’t have the flexibility with China we once had,” he adds, “and whoever is president will have to work with that.”

They’ve faced brutal cops abroad. Now they’re advising US protesters.

Protesters who resist violent policing around the globe are now seeing a special kinship with American protesters, and they're going online to provide support and advice.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Natasha Khullar Relph Correspondent

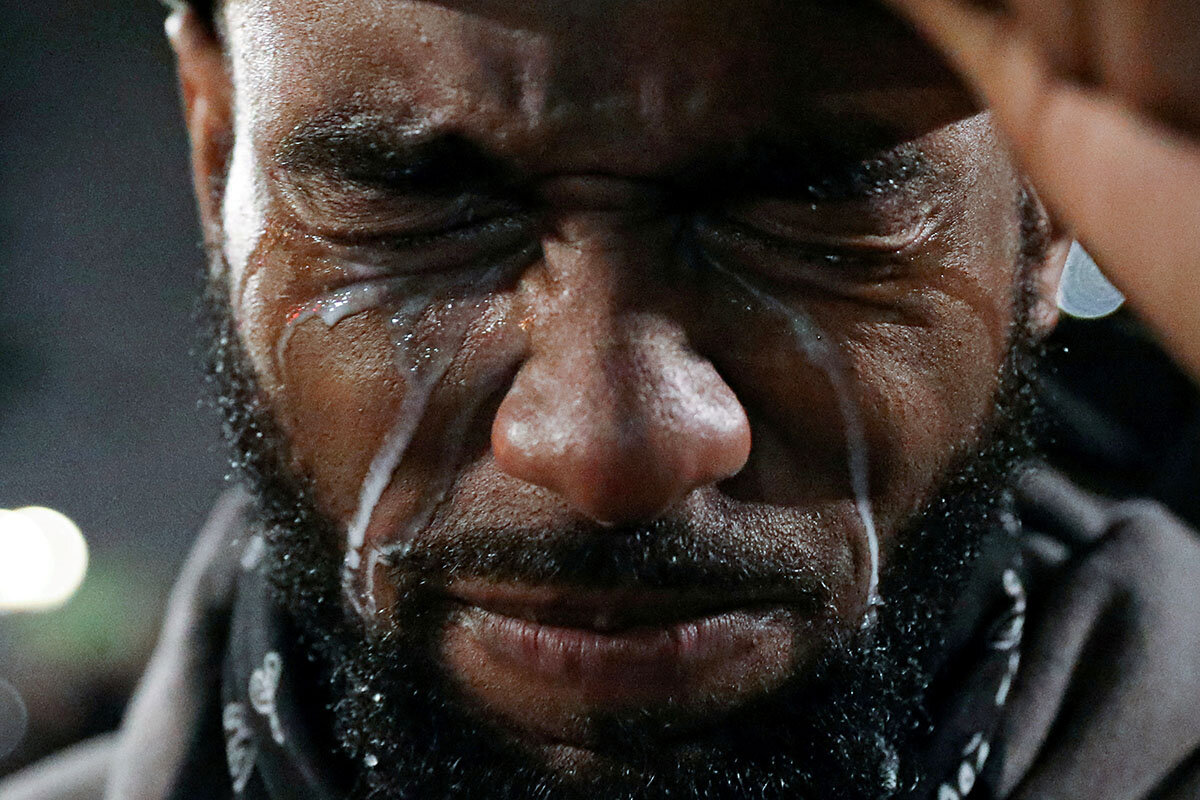

As cities across the United States erupted with protesters demonstrating against the killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd and demanding an end to police brutality, the internet was erupting, too: with advice.

For Rana Nazzal, whose Twitter thread on identifying police weapons went viral, it started with a phone call from a friend in New York who was being fired at with tear gas and had no time to research what to do. Ms. Nazzal, who spent many years joining organized protests in the Palestinian territories, gave him quick tips on keeping safe, but then decided to make it public.

It is a sort of switch for the U.S., which is usually in the position of observer of violent police action globally. But when human rights protests came to the U.S. – along with police action to halt them – a transnational movement of information sharing came with them.

This information sharing was both needed and necessary for people on the ground, given the extent of injuries in the U.S., says Dr. Michele Heisler of Physicians for Human Rights. “In terms of projectile injuries, we’ve already documented about a hundred or more quite serious cases.”

They’ve faced brutal cops abroad. Now they’re advising US protesters.

As cities across the United States erupted with protesters demonstrating against the killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd and demanding an end to police brutality, on the internet, Twitter was erupting, too: with advice.

“Tips, if not wearing a gas mask … rubbing a pinch of salt around eyes, helps combat the impact of the smoke. ... Take care, stay safe & keep reporting. Love from Kashmir.”

“In Palestine, first thing we do under fire is identify the type of weapons israeli cops/soldiers are holding. This defines your strategy for resisting + trying to be safe.”

“israeli soldiers sometimes use stun grenades to thin out a crowd & then go in & arrest people. They know that people with experience won’t run from stun grenades. Keep that in mind because israel trains US police & they may be using same strategies.”

From the identification of weapons to protecting one’s self when shot at, users from the Palestinian territories, Kashmir, Chile, and Hong Kong, gave advice on each and every aspect of demonstrating against brutal police states and keeping safe when in the midst of chaos.

It is a sort of switch for the U.S., which is usually in the position of observer – and sometimes supplier – of violent police action globally. But as the number of protests around the world have risen in recent years, as people have taken to the streets to demand rights and freedoms, so too has a transnational movement of information sharing, largely on Twitter and focused on safety. And when those protests came to the U.S. – along with police action to halt them – the movement came with them.

“Life-changing” information

Law enforcement around the world is increasingly responding to popular protests with crowd-control weapons (CCWs), according to the U.S. nongovernmental organization Physicians for Human Rights (PHR). “The proliferation of CCWs without adequate regulation, training, monitoring and/or accountability, has led to the widespread and routine use or misuse of these weapons, resulting in injury, disability, and death,” PHR noted in a 2016 report. In 2019, analysts at Allied Market Research found that the world’s nonlethal weapons market – that is, weapons frequently used in law enforcement – could be worth more than $9.6 billion by 2022.

For Rana Nazzal, whose Twitter thread on identifying police weapons went viral, it started with a phone call from a friend in New York who was being fired at with tear gas and had no time to research what to do. Ms. Nazzal, who spent many years participating in weekly direct action and joining organized protests in the Palestinian territories and is currently doing her master’s in Toronto, gave him quick tips on keeping safe, but then decided to take it one step further.

While worried for her safety in sharing all that she knew, Ms. Nazzal also felt a powerful sense of urgency. “In Palestine, we usually keep [protester identities and knowledge of weaponry] under wraps,” she says. “I’ve still never touched a weapon; I don’t know that much about them. But now I can identify by looking or hearing the sound. It was one of the things that took me the longest to learn and when I did, it was life-changing.”

Ms. Nazzal was able to identify this weaponry used against U.S. protesters because many of the weapons, especially the tear gas, bought by Israel and seen in protests in the Palestinian territories, are U.S.-made. Protesters in the U.S. were able to look at the weapons being fired at them and using Ms. Nazzal’s posts, among others, recognize them and make educated guesses about next steps during the demonstrations.

This information sharing was needed for people on the ground, given that the extent of injuries in the U.S. was comparable to other demonstrations around the world, according to Dr. Michele Heisler, PHR medical director and University of Michigan professor of internal medicine and public health. “Right now we’re systematically documenting specific cases of injuries but certainly in terms of projectile injuries, we’ve already documented about a hundred or more quite serious cases. The scale and the severity is comparable.”

Some of the cases PHR has documented include a reporter in Louisville, Kentucky, who was hit by a pepper ball while on live television, delivered by an officer who appeared to be aiming directly at her, and a police officer in New York City who pulled down the face mask of a protester who already had his hands up, and shot pepper spray directly into his face.

A new view of the U.S.

Sagar Kaul, co-founder of fact-checking platform Metafact and an expert in tracking misinformation online, was born in the Kashmir Valley and is married to a U.S. citizen. He was 11 years old when the insurgency started in India-controlled Kashmir, and he says he never thought he would ever witness police agencies in the U.S. in their full tactical gear using crowd-control measures the way he saw during protests in Kashmir.

“Foreign policies of the U.S. were always criticized, but domestic problems never found a way into the mainstream media outside the country,” he says. “It’s only now that we know how badly racism and inequality has affected a large population of the country.”

For protesters and the people who have been advising them, there has been a marked shift not just in the way the protests are seen around the world, but the boldness of the protesters themselves.

“We’re seeing a lot more civil unrest that’s going beyond what you’d usually see at a protest, especially a big one,” says Ms. Nazzal. The civilian movements in the U.S. seem to be evolving rapidly, and incorporating strategies from resistance movements elsewhere, such as in Hong Kong, where protesters wore generic black clothing to conceal their identities.

It has been surprising, for many from Kashmir to Brazil, to see such violence being committed against American citizens on U.S. soil by their own police.

“I think we assume that since the U.S. is a developed country, the rights of its citizens to protest wouldn’t be dealt with by bringing in national guards firing tear gas and rubber bullets, and injuring a large number of protesters,” Mr. Kaul says. “The perception of the U.S. as a superpower has definitely changed over the years.”

More parents are home schooling. How that will change public education.

One effect of COVID-19: Families are experimenting with different forms of schooling, and rethinking how education is conducted. That shift in mindset may impact how schools – and society – educate moving forward.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Teri Carey never expected to teach her children at home. But after weeks of researching how to home-school, she has now selected several curriculums, withdrawn her son from his local public school, and started math, science, and history lessons with her 7-year-old.

She’s not alone. A poll of public school parents found that only 27% of parents felt safe sending their children back to school in August or September due to the coronavirus pandemic. And a recent survey of 1,000 parents found 47% were considering home schooling for the upcoming school year.

The likelihood of a sizable uptick in home schooling families – along with families experimenting with other forms of remote education – means many parents are rethinking how schooling can operate, and that’s likely to impact how education is delivered in brick and mortar schools in future, some educators say.

“Right now each is in a box, home schooling and public schooling,” says Joseph Murphy, an education professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, and author of “Homeschooling in America.” “I don’t think the future is going to be that way. I think it will be more like an open playing field.”

More parents are home schooling. How that will change public education.

Teri Carey never expected to teach her children at home. But after weeks of researching how to home-school, she has now selected instruction materials, withdrawn her son from his local public school, and started math, science, and history lessons with her 7-year-old.

“Obviously COVID had a lot to do with it” says Ms. Carey, from Maynard, Massachusetts, who will also care for her toddler this year. “However, it was less about contracting COVID and the fear of getting sick – that was a part of it – but it was more the atmosphere he’d be learning in,” with students and staff wearing masks, desks spaced apart, and limited movement around the building.

“We thought it would be a better learning environment at home,” where he will likely feel less nervous, she says.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

The likelihood of a sizable uptick in home schooling families this year due to pandemic concerns, along with families experimenting with other forms of remote education, means many parents are rethinking approaches to school. Some of them wonder if such options create more flexibility for their schedules, offer more opportunity to discuss cultural heritage, and better accommodate different learning styles. Such a shift could impact how education is delivered in brick and mortar schools going forward, some educators say.

“Right now each is in a box, home schooling and public schooling. I don’t think the future is going to be that way. I think it will be more like an open playing field,” says Joseph Murphy, an education professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, and author of “Homeschooling in America.” He suggests there may be greater blending of home schooling and public education in the future.

A poll of public school parents conducted in June by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) found that only 27% of parents felt safe sending their children back to school in August or September due to the coronavirus pandemic. A recent survey of 1,000 parents commissioned by Varsity Tutors, a tutoring company, found 47% were considering home schooling for the upcoming school year. Inquiries with state and local home-school alliances have spiked.

Public school districts receive funding per pupil enrolled, based on formulas from federal, state, and local sources, says Professor Murphy. The disruption to school finances from people withdrawing students will range from “minimal to annoying to problematic depending on how many kids go out,” he says.

Just over 3% of students were home-schooled in 2016 – the most recent year data is available – an increase from 1.7% of students in 1999, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Susan Wise Bauer, a home schooling advocate and author, expects a large jump in interest in the short-term, followed by the eventual return of most students to traditional school settings and a “small, but substantial bump up in the number of home-schoolers.” She says parents who home-school their children will return to brick and mortar schools wanting to hold deeper conversations with teachers about their children’s education.

In Boulder, Colorado, Emelie Griffith withdrew her 10-year-old twin daughters from private school and started home schooling this summer because their school’s Zoom calls did not engage her kids and they fell behind. She and her husband work full time, but she has adapted by conducting business while her daughters focus on projects. The family often combines school with nature hikes and camping. “It’s allowing us that flexibility while still keeping things exciting in a new environment,” she says.

An explosion of conversations

In recent months, conversation about at-home options for school has exploded on social media and in parenting forums. Parents are seeking matches with other families for home-school pods, posting ads for tutors and public school teachers, and facing questions about whether those who can afford to hire extra help are exacerbating already deep education inequities in the United States.

Proponents of home education say the movement, which is predominantly populated by white students, has grown to include an increasing number of Black and Hispanic families. In 2016, Hispanic children made up 26% of the home-schooled children in the U.S., and Black children consisted of 8% of those home-schooled. Advocates say today’s home-school families also come from a range of religious and nonreligious backgrounds, though the roots of the movement mainly lie with conservative Christian families.

The recent AEI survey found that 34% of white parents and 19% of nonwhite parents say they feel comfortable sending their children back to school in August or September. High-income families also feel it is safe to send their children back to school by almost twice the rate of low-income families.

Muffy Mendoza from Pittsburgh withdrew her three sons from public school six years ago, after serving on her school’s PTA and realizing that the schools “didn’t have a great record of educating Black children.”

Ms. Mendoza tag-teams home schooling with her husband so they both maintain employment and a parent is always present with the kids. She includes a greater depth of African history and lets her children’s curiosity guide their learning. She posts resources about home schooling and unschooling on her website BrownMamas.com and has seen a rise in inquiries and traffic to her site since the pandemic shutdowns.

Recent racial justice protests have also sparked interest in home schooling due to concerns about discrimination and systemic racism in schools. For Black parents in particular, Ms. Mendoza says the switch to home schooling can feel relieving.

“The first thing I noticed once all of my children had been removed from school was the peace I felt in my household,” she says. “And if there are any Black mothers who are reading this, I know you know what I’m talking about. I’m talking about the constant calls that come from the school. I’m talking about the combativeness of getting assignments done. I’m talking about the arguments that happen as a result from the so-called behavior problems that your son or daughter is experiencing at school. The first thing you will notice with home schooling is there’s no more of that.”

Greater opportunities

Marlha Sanchez, from Santa Ana, California, says that home schooling her children gives them opportunities to see their Indigenous and Latinx heritage represented in positive ways, which was lacking in their public schools. (Ms. Sanchez prefers to use the gender-neutral term Latinx.) “It wasn’t until I was an adult that I started to learn about the incredible agriculture practices that existed in Mexico, or the hundreds of Indigenous languages spoken. I really believe that for our kids to feel accepted and empowered and that they belong, they need to see our history in a positive light,” she says.

Ms. Sanchez formed the Unidos Homeschool Cooperative about five years ago, and the tightknit group of families is able to provide child care for each other as parents both work and home-school their children. The Cooperative expanded this summer from serving six families in person to enrolling more than 100 families for virtual discussions of a social justice program developed by Chicana M(other)work, a network of scholars and mothers.

Parents already home schooling when the pandemic hit have experienced disruptions to extracurricular activities, but some are shifting to online activities and making it work. “I love it,” says Dave Miranda of his home-school involvement. The father from Lexington, Massachusetts, owns a consulting business and works with his wife, who also owns her own business, to home-school their 11-year-old son. “Too often it’s vacations or weekend outings when a family does things together as a unit. Why not learn together? I think it’s great to see that we’re all learning and we’re all getting something out of what he’s doing.”

Home schooling has come under recent criticism, with Harvard Law School professor Elizabeth Bartholet calling for a “presumptive ban” due to lack of regulation in the U.S. and concerns about child abuse and quality of instruction. She argues instead for parents to “demonstrate that they have a legitimate reason to home-school.” Advocates counter that home-schooled students are at no greater risk and point to research that they say shows positive academic, social, and professional outcomes for home-schooled students.

For Ms. Carey, the first few weeks have been encouraging. She started early to help herself and her son adjust to the new routine, and they’re enjoying following his interests, like reading about outer space.

“Public education is really ingrained in my brain and I really believe in it,” she says. “I was very intimidated by home schooling, but once I did the research, and it took a while, I saw how manageable it was.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of the organization Chicana M(other)work. As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Africa douses a fire over the Nile’s waters

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Africa’s ability to resolve its internal disputes took a big step this week. Egypt and Sudan agreed to continue seeking an accord with Ethiopia over its new hydropower dam on the Blue Nile River – a vital water source for all three. Merely agreeing to more talks might not seem like progress. Yet with Egypt making threats against its upstream neighbor, leaders of the 53-nation African Union stepped in as mediators and skillfully relieved the tension. Preventing conflicts on the continent has become the AU’s prime focus.

The dam is the largest hydropower project in Africa. Ethiopia began filling its reservoir in mid-July to capture runoff during the rainy season despite a breakdown of negotiations a week earlier. Within days Sudan and Egypt reported lower flow levels in the Nile, a potential problem for agricultural irrigation and other water needs.

Resolving the dispute could set a model for Africa in how to share its abundant natural resources. Both climate change and population growth are straining the environment. Africans need a shift in perspective away from a fear of scarcity and toward a wise and cooperative approach to land and water supplies.

Africa douses a fire over the Nile’s waters

Africa’s ability to resolve its internal disputes took a big step this week. Egypt and Sudan agreed to continue seeking an accord with Ethiopia over its new hydropower dam on the Blue Nile River – a vital water source for all three.

Merely agreeing to more talks might not seem like progress. Yet with Egypt making threats against its upstream neighbor, leaders of the 53-nation African Union stepped in as mediators and skillfully relieved the tension. Preventing conflicts on the continent has become the AU’s prime focus.

The dam is the largest hydropower project in Africa. Ethiopia began filling its reservoir in mid-July to capture runoff during the rainy season despite a breakdown of negotiations a week earlier. Within days Sudan and Egypt reported lower flow levels in the Nile, a potential problem for agricultural irrigation and other water needs.

Resolving the dispute could set a model for Africa in how to share its abundant natural resources. Both climate change and population growth are straining the environment. Africans need a shift in perspective away from a fear of scarcity and toward a wise and cooperative approach to land and water supplies.

“Cooperation is not a zero-sum game,” said Rosemary DiCarlo, United Nations under-secretary-general for political and peace-building affairs, after a round of talks among the three nations earlier this year. “It is the key to a successful collective effort to reduce poverty and increase growth, thus delivering on the development potential of the region.”

Ethiopia announced plans to build the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in 2011, just as pro-democracy protests gripped Egypt and as Sudan was breaking apart after decades of civil war. Since then, negotiators from all three countries managed in fits and starts to resolve most of their differences. The key unresolved issues include a legal framework for settling disputes, a water-sharing agreement during prolonged droughts, and the schedule for filling the dam, which could take up to seven years.

Ethiopia says that when it is finished and filled, the dam will produce enough electricity to accelerate economic growth within and across its borders. Sudan and Egypt, however, claim there are too many uncertainties. Any agreement would depend on stability in Ethiopia, where ethnic tensions run high. In addition, northeast Africa is subject to severe droughts, political fragmentation, and increasing competition from foreign rivals such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia.

One way to set aside those fears is to look at examples of resource-sharing in Africa and elsewhere. An informal pact among Somalia, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda, for example, allows domestic animals to graze across borders. This has eased tensions and hardship in herding communities.

Despite the threats and the breakdowns in the dialogue over the dam, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry nonetheless acknowledged “the undeniable truth of our commonality and camaraderie” earlier this year. He recognized the dam as an opportunity to “chart a new course of peace and prosperity for our peoples.”

That may have been an acknowledgment that Ethiopia’s dam, now mostly built and holding back water, is an undeniable reality. The courage on all sides to embrace cooperation, combined with more efficient use of their waters, could turn resource-sharing into a lasting framework for peace.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding a home

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Lynn Mahoney

Struggling to find a house that would accommodate both her budget and her large family, a woman turned to God for inspiration and guidance. The idea that God is “forever near” – wherever we may be – turned the way she was thinking about the situation around, and a happy resolution ensued.

Finding a home

After years of being happy to rent a home, my husband and I decided to move our family of seven and buy our first home near my parents. This started a rather arduous process of traveling about 190 miles, sometimes several times a month, looking at properties to buy.

The first house we learned about seemed perfect but was way over the price we could afford, so I put the information about it away in a drawer (this was before the internet, so property details arrived by post). As information about various other properties continued to arrive, we found that none of the houses within our budget could accommodate our large family. After six months of searching, we hadn’t found a house yet. It all began to seem impossible.

In difficult situations I’ve often found it helpful to turn to God for help. In this case, I’d been praying with the 91st Psalm in the Bible, which talks about our shelter, dwelling, safety, and guidance found in God. The textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, describes God as “incorporeal, divine, supreme, infinite Mind, Spirit, Soul, Principle, Life, Truth, Love” (p. 465).

This inspired me to think about the idea of home as more than a building. I made a list of the qualities I felt reflected our home in God, and then thought about those qualities in relation to those synonyms describing God’s nature. For instance, I considered that security and safety are included in God as Principle; joy within the house is an expression of divine Soul; kindness and warmth, evidence of the presence of God as Love; and so on.

Yet although this was spiritually uplifting, we still didn’t have a house. I called my mum, who was a Christian Science practitioner (someone who prays for people seeking help with any sort of issue, whether it is health, relationships, or moving house), and asked her to pray with me.

Mum knew I was rather scared to move from our quiet village and sensed that I was still mentally clinging to the home we were in. She helped me see that the ideas I’d been praying with were not just true about one particular home or place. God-given security, joy, and peace are everyone’s to feel and experience, everywhere.

I thought of a hymn I’d often found helpful over the years in bringing up our family. The last verse really helped build my trust in God to lead us forward. It goes:

In Thy house securely dwelling,

Where Thy children live to bless,

Seeing only Thy creation,

We can share Thy happiness,

Share Thy joy and spend it freely.

Loyal hearts can feel no fear;

We Thy children know Thee, Father,

Love and Life forever near.

(Elizabeth C. Adams, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 58, © CSBD)

The realization that God, divine Love and Life, is “forever near” – wherever we are – was the clincher for me. It moved my thought forward, past the fear of an uncertain future.

And you know what happened soon after this change of thought? Through the letter box came another mailing about the very first house, which had seemed so perfect but too expensive. The price had dropped hugely.

When my husband got home from work, we all got in the car and drove to the property. It was perfect for us. Another family was looking at this house that same day, but we were thrilled when the owner accepted our offer, even though it was slightly less than the new price she had sought.

I also prayed to know that the other family would find a place that was right for them. As it happened, years later my son met one of the children from that family, and they became good friends. The family had found a beautiful house of their own.

Though some of our children have their own homes now, my husband and I still live in this house with some of our family. It certainly has been a home where we have “live[d] to bless,” sharing so much happiness. And not just with our own family, but with others, too. For instance, this home later became a refuge for my son’s friend when his family moved away from the area.

Each of us, wherever we are, can turn to God to guide us and feel the spiritual peace and joy that God bestows on all.

A message of love

Once upon a time

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when our Russia correspondent, Fred Weir, looks at a heat wave in Siberia the likes of which hasn’t been seen in centuries, maybe longer. How is Russia responding?