With relatively little effort, the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign on Iran can be seen as both a resounding success and as an abject failure underscoring the United States’ receding influence in global affairs.

Now add to the negative side of the U.S. balance sheet a potentially substantial and long-term foothold being provided to a rising China in the Middle East.

No one questions that the two-year-old policy of harsh sanctions targeting both Iran and other countries willing to cross the U.S. and do business with Tehran has brought the Iranian economy to the brink of collapse. That’s the policy’s “success.”

But if the administration’s goal in imposing that economic misery was to bring Iran back to the negotiating table to reach a “better” nuclear deal, as well as to alter Iran’s “malign behavior” in its neighborhood, the pressure has largely failed.

In announcing the policy in May 2018, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo listed 12 “very basic requirements” Iran would have to meet to win relief from crushing sanctions and get on a path to a new nuclear deal. None of the requirements – ranging from no uranium enrichment and no ballistic missile development to curtailing the undermining of Iran’s neighbors and an end to threats against Israel – has been met, most experts agree.

Perhaps more important, the U.S. has failed to bring many countries along on its approach toward Iran, revealing its waning influence since it left the multinational 2015 Iran nuclear deal in 2018.

On Thursday Secretary Pompeo announced the departure of his special envoy on Iran, Brian Hook. Over his more than two years in the envoy role, Mr. Hook tenaciously pursued the strangulating sanctions that formed the backbone of the maximum pressure policy, and had some success in rallying Arab partners to the U.S. cause. But overall, his departure struck many foreign policy observers as further evidence of the dead end that Iran policy has reached.

Space “filled by China”

Moreover, that waning U.S. influence and ensuing American isolation have opened the door to China to swoop in and rescue an Iranian economy on the brink with a blockbuster strategic partnership deal that many experts say will provide Beijing with a powerful foothold in the region.

“Clearly the U.S. maximum pressure strategy has profoundly surprised the Iranians in how successful it has been at choking the Iranian economy – that part of it has worked,” says Alex Vatanka, director of the Iran program at the Middle East Institute (MEI) in Washington.

“But what it didn’t accomplish was bringing the Iranians back to the table to negotiate a new nuclear deal, as the U.S. failed to articulate exactly what it wanted,” he says. “That has alienated everyone, including the friends and allies the U.S. might have brought along, and that has created a widening space between the two sides – and that space has been filled by China.”

China has decided it wants to be more than “just” an economic power and seeks to play a larger role in key regions like the Middle East, Mr. Vatanka says. “They are looking for vacuums where they can exert their power,” he adds, “and they have found a major one in Iran.”

Certainly the Trump administration did not set out to drive Iran into China’s arms when it developed the maximum pressure strategy. Nor have the Iranians eagerly embraced Beijing’s economic rescue, regional experts say – it’s just that the country’s leaders, and in particular the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, have concluded it’s either that or risk collapse.

“If this strategic partnership ends up baked the way we’re hearing it described, it’s a huge erosion of Iranian sovereignty and acknowledgment by the Iranians that the current [economic] situation has them in truly dire straits that can’t keep going much longer,” says Ilan Berman, senior vice president of the American Foreign Policy Council in Washington and an expert in Middle East security.

“It has them hitching their wagon to [China’s] Belt and Road initiative in a significant way,” he adds, “and basically says the regime has decided, ‘We’re better off in charge of half the country than losing the whole thing.’”

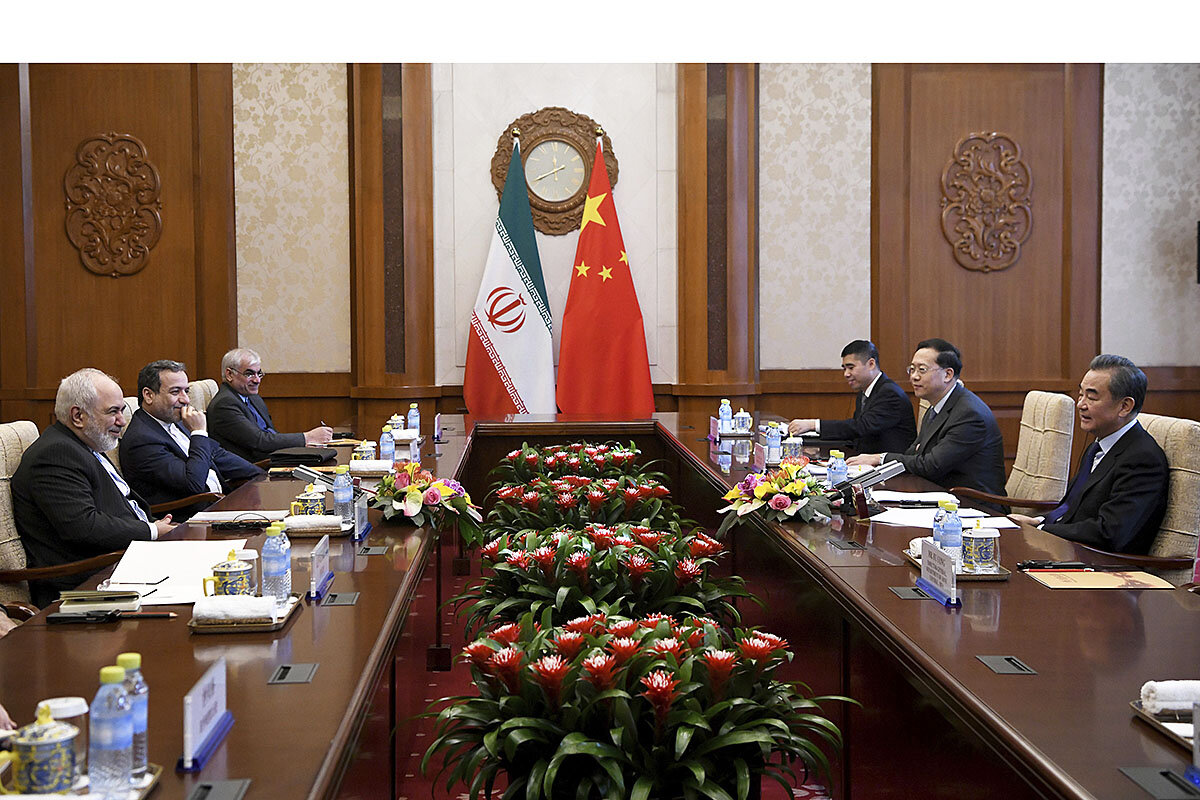

Beijing and Tehran declared after recent talks that negotiations on a 25-year strategic partnership would continue, with a goal of finalizing a deal within a few weeks.

Countering U.S. pressure

Even as China has been negotiating the new partnership, it has been working to thwart U.S. pressure on the Iranian regime – and to highlight America’s deepening isolation from the rest of the world on a number of key international diplomatic matters, including Iran’s nuclear program.

At a recent United Nations Security Council session at which the U.S. pressed to extend an Iran arms embargo set to expire in October, China dismissed the American initiative as baseless because the U.S. is no longer a party to the Iran nuclear deal, also known by the acronym JCPOA, which includes the embargo.

“China opposes the U.S. push for extending the arms embargo in Iran,” said China’s U.N. ambassador, Zhang Jun, at the June 30 Security Council meeting. “Having quit the JCPOA, the U.S. is no longer a participant and has no right to trigger a snapback” to reimpose U.N. sanctions on Iran.

Mr. Pompeo also failed to muster support from European allies on the council, underscoring the lonely American stance on Iran.

Germany, France, and even Britain had hoped to use the JCPOA to rebuild economic ties to Iran and develop Iran’s “historic pivot to Europe,” Mr. Berman says. But he says U.S. policy – in particular the secondary sanctions targeting foreign companies doing business with Tehran – thwarted European aims and “forced the Iranians to turn elsewhere.” That “elsewhere” is to some degree Russia, he says, but primarily China.

Indeed Mr. Vatanka of MEI says the China partnership could signal the finalization of Iran’s “protracted divorce process” from the U.S. and the West more broadly that started with the 1979 Iranian revolution.

After failing on his first go at extending the Iran arms embargo, Secretary Pompeo now says he will try again – and that the U.S. will proceed to take “necessary action” to ensure that Iran does not import proscribed arms if the embargo expires.

But in light of the dearth of support for the U.S. position, the likelihood of Mr. Pompeo winning an extension before the October expiration seems virtually nonexistent, most experts say.

As Mr. Berman notes, all the parties involved are “hedging their bets” given the proximity of the U.S. presidential election and the possibility that U.S. policy on Iran could shift back to a more traditional diplomatic approach should President Donald Trump lose his reelection bid.

Moving on from Iran

In any case, the Iranian issue has lost much of the “salience” it had in Washington just a couple of years ago, says Mr. Vatanka.

It is true that a group of congressional Republican hawks called the Republican Study Committee recently issued a report on the Middle East, with particular attention to Iran’s “rogue activities” in the region and steps the U.S. should take to counter them. Those should include even tougher sanctions on Iran’s “vital sectors” and the designation of Iranian-backed “proxy militias” as terrorist groups, the group said.

And at a recent appearance by Secretary Pompeo before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Democratic Sen. Robert Menendez of New Jersey blasted the Trump administration’s Iran policy for leaving Iran closer to acquiring a nuclear weapon than it was when the administration withdrew from the JCPOA.

But for the most part, Washington has redirected its sights to China as its No. 1 adversary, Mr. Vatanka says. As an example, he points to how “the China challenge” ended up dominating Mr. Pompeo’s Senate appearance, which was supposed to focus on Iran.

When it comes to America’s biggest threat, Mr. Vatanka says, “This town has moved on.”