- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The Jacob Blake shooting: More confirmation of police racial bias?

A white officer was filmed shooting a Black man in the back in Kenosha, Wisconsin, Sunday while his three children watched. Outrage and riots have followed.

Jacob Blake’s shooting once again tragically confirms racial bias in policing. Or does it?

It turns out the research on police brutality is all over the map.

“Black men are about 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police over the life course than are white men,” a 2019 study by sociologist Frank Edwards concludes.

But commentator Coleman Hughes writes that other studies show white Americans are just as likely as Black Americans to be fatally shot by police. (One of the four research papers cited by Mr. Hughes has since been withdrawn from publication.) This isn’t to say that racism doesn’t exist in law enforcement. In fact, one of those studies found that for all non-fatal police interactions – such as traffic stops and arrests – even when they’ve been compliant, Black Americans are 21% more likely to be subject to use of (non-lethal) force than white Americans.

On average, every day three Americans are killed by police. The racial breakdown of that data can be parsed various ways. But as Mr. Hughes, a Black writer, suggests, we need an “honest and uncomfortable” conversation about the problem. And if the data suggests the problem of excessive force is less fueled by racism and more by police training and a hair-trigger mindset, that should be addressed.

And solving that problem could make all Americans safer.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Last man standing: How Pence’s loyalty helped him survive

Vice President Mike Pence offers a portrait of loyalty and durability in an administration marked by turnover and drama. Our reporter looks at what’s made this relationship work.

Vice President Mike Pence is one of the few original Team Trump members still around, in an administration marked by record turnover and endless drama. He’s survived despite persistent rumors that the president might replace him with a more exciting candidate, such as former U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley or South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem.

Through it all, Mr. Pence has presented a picture of steadfast support – always on message, never contradicting his boss, rarely allowing a crack of daylight between the two.

And as the vice president formally accepts his party’s nomination again on Wednesday, some say he’s playing the long game. His political future was always going to be tied to the administration’s record, for better or worse. But among the many candidates angling to pick up the Trump mantle in 2024, Mr. Pence could wind up better positioned than most – having established himself as the staunchest of allies, while maintaining a persona distinct from the president’s more controversial one.

“Mike Pence has probably been the most consistent member of the Trump administration,” says Kurt Luidhardt, an Indiana-based Republican strategist. “I think Pence will have earned the right, whether Trump wins or loses, to be a top candidate for president in 2024.”

Last man standing: How Pence’s loyalty helped him survive

When Donald Trump tapped Mike Pence to be his running mate in 2016, it seemed an unlikely pairing. One was a thrice-married former reality TV star; the other a devout Evangelical who made it a policy never to be alone in a room with a woman who was not his wife. The brash New York real estate mogul was making his first run for public office; the governor of Indiana had spent a dozen years as a congressman, and was known for a placid demeanor that even allies admitted could come across as dull.

Yet in Mr. Pence, Mr. Trump may have spotted a quality that he is frequently said to prize above all others: loyalty.

Four years later, the vice president is one of the few original Team Trump members who’s still around, in an administration marked by record turnover – even longtime aide Kellyanne Conway will step down at the end of the month – and endless drama. He’s survived despite persistent rumors that the president might replace him with a more exciting candidate, such as former United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley or South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem.

Through it all, Mr. Pence has presented a picture of steadfast support – always on message, never contradicting his boss. Not only has he never attempted to carve out a distinct political identity apart from Mr. Trump, he seems to have made the decision not to allow even a crack of daylight between the two.

But as the vice president formally accepts his party’s nomination again in a speech at Fort McHenry in Baltimore on Wednesday, some say he’s playing the long game. His political future was always going to be tied to the administration’s record, for better or worse. But among the many candidates angling to pick up the Trump mantle in 2024, Mr. Pence could wind up better positioned than most – having established himself as the staunchest of allies, while maintaining a private persona distinct from the president’s more controversial one.

“Mike Pence has probably been the most consistent member of the Trump administration,” says Kurt Luidhardt, an Indiana-based Republican strategist who has worked in the same political circles as the former Indiana governor. “I think Pence will have earned the right, whether Trump wins or loses, to be a top candidate for president in 2024.”

An odd couple for the ages

Despite their differences, the Trump-Pence partnership made sense for both men in 2016.

Mr. Pence was in the middle of a tough reelection race that some pundits suspected he would lose. A place on the presidential ticket gave him the opportunity to boost his national profile while evading a loss that could end his political career.

Mr. Trump, for his part, had a relatively small pool of candidates to choose from, as many GOP officials had publicly criticized him. In Mr. Pence he found not only a willing partner, but someone who could help shore up white Evangelicals, a critical Republican voting bloc.

“Trump selected an evangelical vice president on purpose,” says Frances FitzGerald, author of “The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America.” “He wanted to reassure them that even if he wasn’t going to church, his vice president was.”

Mr. Pence’s solid conservative credentials may also have sent a message of reassurance to Republican voters unsure about Mr. Trump’s ideological leanings. The vice president – who famously introduced himself at the 2016 Republican National Convention as “a Christian, a conservative, and a Republican, in that order” – had one of the most conservative voting records during his six terms in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Former Mississippi Rep. Gregg Harper, who served alongside Mr. Pence in the House, says he considered Mr. Pence his “bell cow” – a term for the lead cow of a herd that shows the others where to go.

“If I wanted to be sure I voted right, I’d look up at his vote,” says Mr. Harper. “I had that level of trust with him.”

The Trump-Pence relationship was tested almost immediately in the 2016 campaign, after an audiotape from “Access Hollywood” was leaked to the press in which Mr. Trump could be heard boasting in crude terms about his ability to force himself on women. Mr. Pence reportedly considered leaving the ticket, as a parade of Republican officials denounced their party’s nominee, who was down in the polls just weeks before the election. Yet in the end, Mr. Pence made the pivotal decision to stick by Mr. Trump.

Four years later, the president seems less in need of Mr. Pence’s political help with the base – having satisfied many conservatives with his record on everything from tax cuts to deregulation. For white Evangelicals, the president has “done everything he’s promised them, from Jerusalem to the Supreme Court,” notes Ms. FitzGerald, referring to Mr. Trump’s decision to move the U.S. Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, a long-held conservative dream. She adds: “And you would not think this is true, but a lot of them like his style. ... They like the idea of turning the world upside down.”

Yet while the president may not need Mr. Pence as much from a political standpoint, allies say he would be hard-pressed to find a more faithful governing partner. Much of the credit for the relationship, observers suggest, goes to the vice president – his willingness to toe the line, and cede the spotlight entirely to his boss.

“I’ve always found [Mr. Pence], personally, to be a really humble guy,” says Mr. Luidhardt. “Some people can’t handle being second in command, but I don’t think that’s ever been his problem.”

Loyalty taken to a new level

John Nance Garner, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s running mate on the 1932 Democratic ticket, described the vice presidency as “the spare tire on the automobile of government,” and, more famously, as “not worth a bucket of warm spit.”

Most vice presidents are loyal and supportive, says law professor Joel Goldstein. “But Vice President Pence,” he says, “seems to have taken it to a new level.”

Mr. Pence has maintained this steadfast posture in an administration marked by an unusual level of turmoil. Vice presidents often want to be “in the room where it happens, to borrow the line from ‘Hamilton,’” says Mr. Goldstein, author of the book “The White House Vice Presidency: The Path to Significance, Mondale to Biden.” But that’s much more difficult when policies are being made in late-night tweets, he notes. “And there are some times when you don’t want to be in the room.”

On the few occasions when Mr. Pence has even slightly diverged from the president, he’s done it in the mildest of ways. Ahead of the 2018 midterms, when Mr. Trump endorsed Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore, despite allegations of sexual misconduct, Mr. Pence chose to stay silent on the issue. The vice president attended the funeral of Georgia Rep. John Lewis while Mr. Trump, who had feuded with the civil rights icon, skipped the event. Most recently, Mr. Pence called QAnon a “conspiracy theory,” while Mr. Trump has seemed to court QAnon believers.

Still, Mr. Pence waited to comment on the death of Mr. Lewis, whom he considered “a colleague and a friend,” until after the White House had issued its own statement. And last week, he claimed he “didn’t hear anything” about the president embracing QAnon.

Perhaps the most high-stakes example of Mr. Pence’s deft balancing act has been his leadership of the White House coronavirus task force, a politically risky role that his staff was reportedly hesitant for him to accept. Early on, the president took charge of the task force’s public briefings – which led to some politically damaging moments, such as when Mr. Trump suggested that an “injection inside” the body of disinfectants could be explored as a possible treatment for COVID-19.

After the president said that he was taking the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine to prevent COVID-19, Mr. Pence told reporters he would not follow suit, as his own physician had not recommended it for him. Still, he added: “I would never begrudge any American taking the advice of their physician.”

The vice president is frequently seen wearing a mask when out in public, while Mr. Trump initially refused to wear one and still rarely does. During a visit to the Mayo Clinic in May, Mr. Pence drew criticism for not wearing a face covering – a move for which he later publicly apologized.

His role on the coronavirus task force underscores the ways in which Mr. Pence could wind up taking on much of the baggage of Trump administration failures – especially if the U.S. continues to struggle to get the virus under control and Mr. Trump loses his bid for reelection.

“Because [Mr. Pence] has embraced this role as Trump’s champion so enthusiastically, it’s hard to see him as having a separate identity,” says Mr. Goldstein. “In 2024, a lot of people in the Republican Party who are going to run for president are going to attack Pence and say, ‘Why didn’t he do this or that with COVID-19?’”

In contrast to other recent vice presidents, Gallup found that just as many Americans have an unfavorable view of Mr. Pence as those with a favorable view, perhaps reflecting how much his identity is linked to Mr. Trump’s.

Still, a recent poll by Echelon Insights found that while a plurality of Republican voters – almost 30% – are unsure as to whom they will support in four years, Mr. Pence was the top choice for 26% of them (Donald Trump Jr. came in third, with 12%).

The vice president has traveled quite a bit on behalf of the Trump administration, even in the pandemic era. Following the conclusion of the Republican National Convention, he plans to travel to three Midwestern battleground states, visiting Michigan and Minnesota on Friday before delivering a commencement speech in Wisconsin on Saturday.

And while he may be campaigning in a Trump-Pence 2020 bus, the undercurrents of his own political ambitions are just beneath the surface. Mr. Pence may have said it best himself, during his first RNC speech back in 2016.

“Now, if you know anything about Hoosiers ... we play to win,” said Mr. Pence to a cheering crowd in Cleveland. “That’s why I joined this campaign in a heartbeat.”

California wildfires: Why this year is so intense

Sometimes, extreme adversity can offer a learning experience. In the case of California’s wildfires, our reporter finds this might invigorate a rethinking of our relationship with nature.

With torrential lightning storms, hundreds of fires, and more than 120,000 people evacuated, California is confronting a once-in-a-generation fire season.

As COVID-19 hamstrings the state’s containment and evacuation plans, millions in the American West are watching a tragedy of circumstance. Environmental intrusion, decades of government inaction, and high winds have forced the situation out of control. Without adequate prevention, scientists predict the country’s wildfire seasons will grow in size and cost in the next 50 years.

But those predictions are far from certain. If there’s any hope from this year’s fire season, says Jessica Gardetto of the National Interagency Fire Center, it’s that it serves as a warning.

Ms. Gardetto says that the national number of acres burned so far is below the yearly average – less than 3 million compared with the typical 4 million to 6 million. Though large population centers are threatened, she says, the fires afflicting them are freaks of nature, rather than more usual results of human malpractice.

So now is the time for communities and governments to learn.

Locales in fire-dependent ecosystems can lower risk by building more fire-resistant homes and thinning nearby vegetation, says Ms. Gardetto. State governments can enforce those practices through building codes and fire-extension programs, which integrate experts into at-risk areas for long-term change, says Scott Stephens, a wildfire expert at the University of California, Berkeley.

Through such a combination of education, prevention, and policy, the American West can lower its vulnerability and promote more harmony between humans and nature.

In fire-dependent ecosystems, the risk of wildfire will always exist. But it can become much more manageable, says Professor Stephens. To reduce the chance of another catastrophic fire season, it may have to be.

“The longer-term view has to be being better prepared for the inevitability of fire,” he says. – Noah Robertson

Chart 1: NASA MODIS; Chart 2: California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection; Chart 3: "Climate change presents increased potential for very large fires in the contiguous United States," International Journal of Wildland Fire

Patterns

Two major changes that made the Israel-UAE peace deal possible

The deal has rightly been lauded as historic and a radical reframing of the path forward. But our columnist wonders about the political and value judgments, such as rule of law and stability, that once formed the core assumptions of U.S. diplomacy in the Middle East.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The accolades for the Israel-United Arab Emirates peace deal – only the third formal treaty between Israel and an Arab state – were deserved. But in the Middle East, the political context is always complex.

In practical terms, the agreement makes public an increasingly open secret of cooperation. Still, for Israel, the public acceptance matters hugely.

Two major changes in political context made the deal possible. For many Sunni Muslim Arab states, the conflict with Israel has taken a back seat to concern over Shiite Iran. Israel’s strength in intelligence, cyberscience, and technology encourages cooperation. The Arab world’s commitment to the Palestinians has eroded.

Equally important has been the dramatic change in Washington’s approach. The United States began with an explicit message: The Palestinians were in no position to dictate a new deal. After testing reaction to moving the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem (very little) and permission for Israel to annex parts of the West Bank (far more), the U.S. sought a relatively transactional arrangement with something for everyone.

Yet U.S. assumptions that long drove policy were not just the result of orthodoxy. They reflected value judgments about international law, precedent, and stability. U.S. policymakers will have to weigh whether those judgments still matter.

Two major changes that made the Israel-UAE peace deal possible

“Breakthrough. Historic.” Those were the headline-writers’ words of choice after this month’s U.S.-mediated accord between Israel and the United Arab Emirates – even among vocal critics of President Donald Trump’s iconoclastic approach to foreign policy.

The accolades were deserved. Not just because the public pledge of peace, if followed through on, would mean only the third formal treaty between Israel and an Arab state – and the first for more than a quarter century. It also followed a deliberate drive by the Trump administration to cast aside decades-old diplomatic assumptions about peacemaking in the Middle East.

It holds little surprise that Mr. Trump at this week’s Republican Party convention – or Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who has headed off to visit Israel and the UAE – seemed minded to a kind of “we told you so” victory lap.

Yet as so often is the case in the Middle East – a region I’ve covered since the first Arab-Israeli peace breakthrough, between Israel and Egypt in the late 1970s – the political context is complex. And key questions remain, above all about the still-unresolved conflict between Israel and its Palestinian neighbors, and the future of the West Bank territory it captured in the Six-Day War more than 50 years ago.

An open secret goes public

In practical terms, the Israel-UAE agreement doesn’t change much. It simply makes public an increasingly open secret. For some years now, the UAE and other Arab states in the oil-rich Gulf have been engaging quietly with Israel in multiple areas: politics, security, business, even culture and sports.

But for Israel, the public acceptance of normalization matters hugely. For decades since the founding of modern Israel in 1948, the Arab world hasn’t just rejected the idea of peace. It has questioned Israel’s legitimacy – a challenge with a deep impact on Israelis of all ages and political views. The most powerful moment during the first peace breakthrough was when then-Egyptian President Anwar Sadat told the Israeli Knesset in 1977, “We used to brand you as so-called Israel. ... Now I tell you that we welcome you among us.”

But Sadat’s lead had, until this month, been followed by just one other Arab head of state: the late King Hussein of Jordan.

Two major changes in political context made the UAE deal possible.

The first was in the Middle East itself. For many Sunni Muslim Arab states, the conflict with Israel has taken a back seat to concern over the growing political and military reach of Shiite Iran. That’s especially true for Gulf Arab countries like the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain, directly across from Iran. For them, moreover, Israel’s unparalleled regional strength in intelligence, cyberscience, and technology have made cooperation especially attractive.

At the same time, the major impediment to past normalization – the Arab world’s commitment to the Palestinians – has been eroding. The Israeli-Palestinian peace process has effectively ended. The Palestinian leadership is divided, between the heirs of Yasser Arafat’s Fatah movement on the West Bank and the Islamist Hamas in Gaza. Amid complaints of mismanagement and corruption, their popular support has been weakening.

Yet equally important has been the dramatic political change in the United States – and in Washington’s approach to the region.

The U.S. initiative that led to the Israel-UAE deal began with an explicit message to all involved: The Palestinians, having turned down previous negotiating proposals aimed at creating a two-state peace, were in no position to dictate the terms of a new deal. Washington drove home the point two years ago by moving its embassy to Jerusalem, the holy city whose status, under decades of past U.S. policy, was to be resolved only as part of a final peace. The move triggered barely a murmur of opposition in the Arab world.

In its Mideast peace plan announced earlier this year, the Trump administration pushed this approach further. It green-lit the idea that Israel could formally annex parts of the West Bank – which did prove too much for many Arab countries, including the UAE, which pushed back both privately and publicly.

Going transactional

Yet that turned out to be the cue for the other key facet of Mr. Trump’s altered approach: the idea of seeking a more limited, transactional arrangement of the kind more traditionally employed by big business.

Everybody got something out of it.

The UAE got closer cooperation with Israel on security, intelligence, and cyber capability, and critically, the prospect of being able to purchase top-end American military equipment like F-35 fighter jets that have long been off the menu for Arab states. It also received some regional political cover in the shape of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s retreat from any annexation of the West Bank, at least for now.

Israel got the promise of its third peace with an Arab country, and the possibility of others eventually following suit. The UAE’s neighbor, Bahrain, is one candidate. So is Sudan, in Africa. Mr. Pompeo is visiting both this week.

The deal also came at a particularly apt time for Mr. Netanyahu. He was already backing off the idea of annexation, both because of Washington’s second thoughts and a cool response from most Israelis, who are a lot more preoccupied with the dire economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. And Mr. Netanyahu himself still faces trial on three charges of corruption for which preliminary hearings have begun.

Finally, the Trump administration itself got an undeniable diplomatic victory.

Still, beyond the question of what comes next for the Palestinians, a more fundamental issue about Middle East diplomacy will bear watching, especially should Mr. Trump lose the White House in November, bringing in Joe Biden and a more traditional approach to foreign policy.

The old core assumptions of American diplomacy in the Middle East – on the status of Jerusalem and the West Bank, or the future political dispensation for the Palestinians – were not just the result of ossified bureaucracy or hidebound orthodoxy.

They reflected political and value judgments. Permanent Israeli control over the West Bank and widening settlement of Israeli civilians there were viewed as a violation of international law and an unwelcome precedent for the wider world. A negotiated peace between Israel and the Palestinians, in spite of its ever-receding prospects, was seen as not only good for the Palestinians and Israel. It was part of a wider aim to bring more stability to a chronically fractious region and, to the degree the U.S. could help deliver it, further American interests as well.

With the huge recent changes in the Mideast – Iran, most of all, but also the war in Syria, the political and economic crisis in Lebanon, the growing assertiveness of Turkey, and the reentry of Russia into the fray – U.S. policymakers will have to ask themselves whether those other long-held judgments still matter.

Did life on Earth come from space? Chummy microbes offer clues.

The origin of life on Earth is perhaps biology’s biggest mystery. But what if life arrived from elsewhere? We look at new research that tests the resiliency of microbes transiting the cosmos.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Where did life on Earth come from? Scientists know that about 4.4 billion years ago, microorganisms appeared on the planet and began to evolve. But they don’t know how a lifeless Mother Earth produced them in the first place.

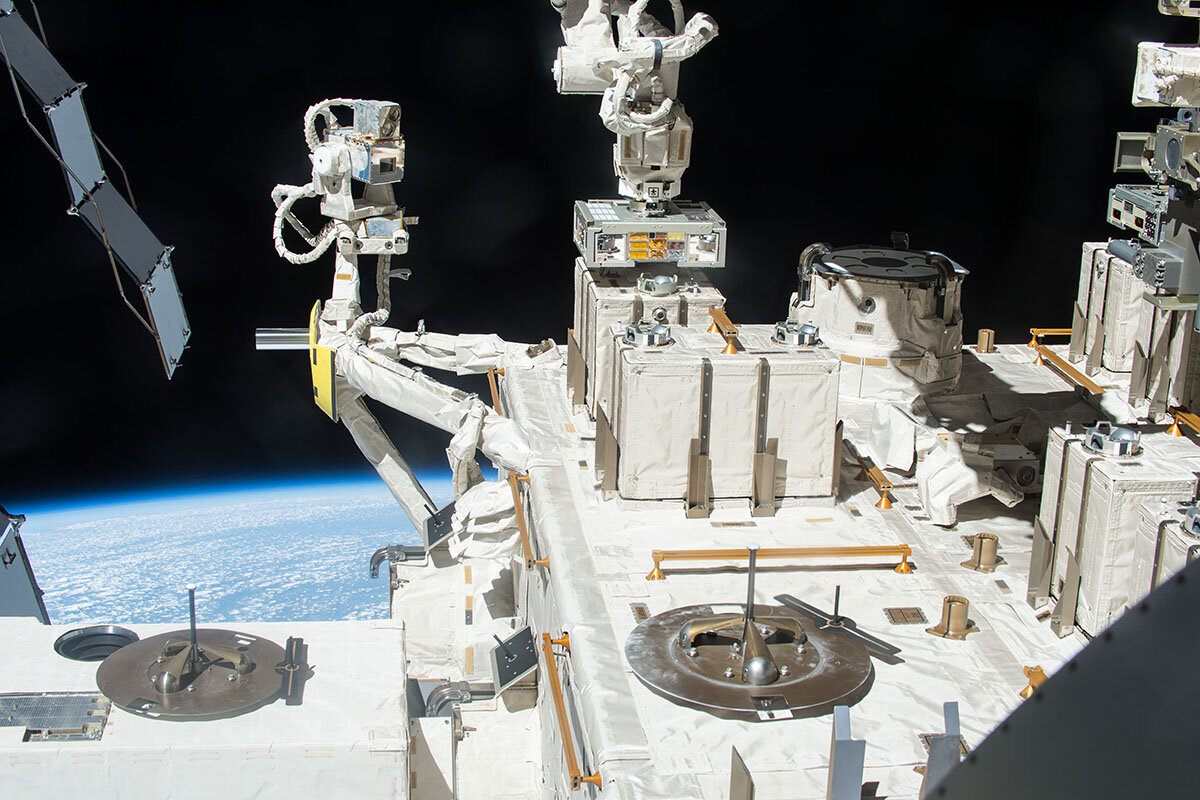

One possible explanation is that she didn’t. Instead, the idea goes, microbes arrived from elsewhere in space. This hypothesis, known as panspermia, remains little supported, but an experiment aboard the International Space Station shows how microbes could have survived travel between Mars and Earth.

A study published Wednesday describes how scientists placed aggregates of dried bacteria on exposure panels outside the space station. After three years, in the vacuum of space, some of the single-celled organisms survived. Cells on the outside layer died, but protected those within.

“We are what we are, but it should perhaps let us realize better that we are part of the universe,” says Purdue University geophysicist Jay Melosh, a proponent of the panspermia hypothesis. “We’re not just confined to our own little planet. We’re the offspring of a truly interplanetary process.”

Did life on Earth come from space? Chummy microbes offer clues.

Where did life on Earth come from? Scientists know that sometime around 4.4 billion years ago, microorganisms appeared on the planet and began to evolve. But they don’t know how a lifeless Mother Earth produced them in the first place.

One possible explanation is that she didn’t. Instead, the idea goes, microscopic lifeforms fell to Earth from space, after traversing the harsh vacuum from another planet.

Many researchers consider this hypothesis, called panspermia, unlikely. But a study published Wednesday shows how single-celled organisms might have survived a journey from, say, Mars to the early Earth through space.

Questions remain about the numerous challenges microbes would face along the way. But if panspermia is indeed possible, and life can be readily dispersed throughout the cosmos, it would fundamentally change how we earthlings see ourselves.

“We are what we are, but it should perhaps let us realize better that we are part of the universe,” says Jay Melosh, distinguished professor of earth and atmospheric science at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. “We’re not just confined to our own little planet. We’re the offspring of a truly interplanetary process.”

Seeds of life

Most scientists say that Earth-life probably did originate on Earth. The standard thinking goes that somehow the conditions were ideal for just the right minerals to come together in a series of chemical reactions that yielded self-replicating molecules, that is, early life. But the particulars of that scenario have been tricky to pin down, leaving room for other possibilities.

The concept of panspermia was kicked off, in part, by the humongous eruption of a volcano on the island of Krakatoa in 1883, says Dr. Melosh. The eruption completely sterilized the island, but just months later, life began to flourish anew. Naturalists explained that the miraculous regeneration came from seeds and insects floating on the winds or the tides from nearby islands, and that got some scientists thinking about the cosmos. Perhaps early Earth was like a barren island, too, they speculated, and the seeds of life or life itself drifted around space and alighted on our planet at just the right moment.

Since then, scientists have learned that the bombardment of cosmic radiation makes it extremely difficult for any kind of life as we know it to survive a journey through space. But for some scientists, the panspermia hypothesis still holds promise.

Dr. Melosh is one of those scientists, and some four decades ago, he proposed that, rather than drifting naked through space, microorganisms might survive that harsh environment in a protected place within rocks. According to this conjecture, life may have been present inside rocks on, say, Mars. And when an impact on the red planet ejected some of those rocks into space, one eventually wound up landing on Earth. Indeed, of 60,000 or so meteorites discovered on Earth so far, nearly 300 are thought to have originated on Mars.

Other researchers have focused instead on whether there are organisms that could survive the harshness of space. To do that, one team of researchers in Japan decided to send some bacteria into space for a few years.

They focused on one particular group of bacteria known to be resistant to radiation and quite resilient: Deinococcus. The team took dried-up colonies of that bacteria and placed them on exposure panels outside the International Space Station. The samples were exposed to the space environment for one, two, and three years.

As it turns out, after three years, some of the bacteria had survived. In fact, although the outside layer of the colony did perish, it ended up creating a protective layer for the microbes underneath. The team’s results are reported in a paper published in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology on Wednesday.

“Our life might [have] originated in Mars if panspermia is possible,” says Akihiko Yamagishi, an astrobiologist at the Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences and the lead author of the new study.

It’s not just about radiation, though. Life as we know it requires water. So how long could a living organism survive being dried out? Previous research has found that spores of a common bacteria, Bacillus subtilis, can survive in space.

But for how long? A rock that’s been broken off of another planet and flung into space probably doesn’t take a direct path to Earth. Rather, it likely falls into an orbit around the sun and is slowly pulled into different trajectories by the gravity of larger space rocks over time. Eventually it may cross paths with the Earth, but that could take millions of years – or longer.

And even if life did survive the trip through space, and then through Earth’s thick atmosphere, it might not be so happy on the surface of the planet, says Steven Benner, a chemist at the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Alachua, Florida. These organisms would be adapted for the environment of another planet, and then for survival in space, so Earth might seem like a particularly hostile environment, he says.

“You know, they’re not used to going to Wawa or 7-Eleven for groceries; they’re used to going to the Martian equivalent,” says Dr. Benner. “And maybe the Martian equivalent has food that’s much different than what they’re going to be having access to on Earth.”

Are we all Martians?

Mars today does not seem very inviting for life, but billions of years ago, the red planet was much more like Earth is today, with flowing rivers, lakes, and oceans. One big question that remains is whether life has ever existed on Mars.

NASA’s latest mission to Mars launched last month, and it aims to sniff out a definitive answer to that question. The new rover, named Perseverance, is equipped to search for signs of past life on Mars and to bag rock samples to be returned to Earth for further study on a future mission.

Although he famously entertained the panspermia model for the origin of life on Earth at a conference a decade ago, today Dr. Benner is dubious. At the time, he says, geologists thought that Earth 4.4 billion years ago was a water world with no dry land to speak of and scientists thought some dry land would be needed for life to arise. But since then, that view has changed and geologists have said dry land might have been around at the right time.

“So we don’t really need Mars,” Dr. Benner says. “Certainly life emerging on Earth does not seem to be such a wild improbability that we require places elsewhere.”

Dr. Melosh is still keen on the idea, however, as the surface of Mars likely did have just the right conditions at the time. Still, he says, “It’s a more complicated solution. And it really doesn’t solve the problem of the origin of life. It just puts it back a [bit]. ... Maybe you buy a few hundred million years that way.”

Alphonso Davies: Canada's humble, joyful soccer phenom

Prepare to be inspired. Our reporter profiles a young Canadian soccer star. It’s a rags-to-riches tale of a Liberian refugee who exudes humility, joy, and gratitude for his adopted home.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Alphonso Davies has been the sports story in Canada this week, after the 19-year-old soccer star and his team, Bayern Munich, won the Champions League in Europe on Sunday. But it has also been his humility, groundedness, and charisma – as well as his origin in a refugee camp in Ghana – that have earned the nation’s adoration.

Mr. Davies has been invigorating sports observers like Shireen Ahmed of the “Burn It All Down” podcast. “I don’t know if I’m more impressed with his Champions League win or with the maturity he shows on the field, the way he has literally blended in with one of most experienced and sophisticated squads in the world at such a young age.”

What stands out most for her is how he combines technical skill, boldness, and speed with “that spirited joy you don’t often see,” she says.

“Life is too short to be angry or sad for long,” he told Bayern’s club magazine. “We went through tough times when I was very young and I’m so infinitely grateful to my parents. ... Their journey began during the civil war in Liberia. ... I’m in the happy situation where I can say I can enjoy every single day of my life.”

Alphonso Davies: Canada's humble, joyful soccer phenom

After Canadian soccer star Alphonso Davies and his team, Bayern Munich, clinched the Champions League in Europe this past weekend, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau tweeted his congratulations to the 19-year-old left back.

Mr. Davies replied: “Thank you Prime Minister @JustinTrudeau! Can I please come home for a week?”

With that single tweet, the newest Canadian sports star revealed glimpses of how he has captivated his nation. It’s for more than the poise he possesses on the field despite his age, and it extends beyond the irresistible success story of a boy who came to Canada as a refugee and became one of the most important prospects in the game.

His request to the prime minister was a reference to restrictions on travel because of the pandemic that has kept him apart from family in Alberta, while he basks in victory in one of soccer’s most important competitions. But with the question – which included a grimacing emoji and pleading hands along with three Canadian flags – he showed traces of the humility, groundedness, and charisma that his former coaches and sports observers say make him such a good role model and, to some, one of Canada’s most significant athletes.

His story is impossible to put down, one that earned plaudits from the UN Refugee Agency and Canadian politicians across the spectrum. Perhaps most significantly to Mr. Davies, it earned him a follow on Instagram from rap icon (and Toronto native) Drake – a social media honor that had him shouting with delight.

From refugee to the world’s best

He was born in Ghana’s Buduburam refugee camp, which was created for Liberians fleeing civil war like his parents. His family was eventually able to resettle in Edmonton, the capital of Alberta, when he was 5. Early mentors talk often about the long hours his parents worked, and the responsibilities Mr. Davies had at home, at just 10 years old, like changing his younger siblings’ diapers.

It was on the soccer field that he found an outlet and sense of belonging. Tim Adams founded Free Footie in Edmonton, a league for elementary schoolers whose families can’t afford recreational sport. One of his teachers connected him to the program. It was only a brief season, but Mr. Adams says that is all it took. “There are some kids where even if they touch the ball one time you know that they are special,” he says. “He was moving through a crowd of a thousand, and you could tell there was something different.”

He played soccer at St. Nicholas Soccer Academy and for the Edmonton Strikers youth club before enrolling in the residency program of the Vancouver Whitecaps, one of Canada’s top-flight teams, at 14. He had to convince his parents, who were worried about his studies and bad influences, to let him leave. His father, Debeah Davies, hammered into him: “Be a good guy. Be a good kid. Be a good boy,” he said in a Whitecaps video.

Mr. Davies made his Major League Soccer debut for the Whitecaps at 15, and in 2017, after he became a Canadian citizen, he became the youngest player to appear for the Canadian men’s team. At 17, he signed with one of the world’s best teams, Bayern Munich, which paid the Whitecaps at least $13.5 million in transfer fees, a record-setting deal for an MLS player at the time.

This time he had to convince himself. When Bayern reached out to meet him, he recalled recently in The Guardian, “I was like, ‘oh my god, really?’ It was both exciting and scary. I just had to prove to myself that I could compete at this level.”

‘That spirited joy you don’t often see’

Throughout it all, Mr. Davies has been invigorating sports observers like Shireen Ahmed, co-host of Burn It all Down, a feminist sports podcast. “I don’t know if I’m more impressed with his Champions League win or with the maturity he shows on the field, the way he has literally blended in with one of most experienced and sophisticated squads in the world at such a young age.”

What stands out most for her is how he combines technical skill, boldness, and speed with “that spirited joy you don’t often see,” she says. “He adds this life, this happiness.”

Joy is something he has carried throughout his life, he told Bayern’s club magazine. “Life is too short to be angry or sad for long. I think it runs in my family. We went through tough times when I was very young and I’m so infinitely grateful to my parents,” he said. “Their journey began during the civil war in Liberia and we came to Canada via Ghana. I’m in the happy situation where I can say I can enjoy every single day of my life.”

Globe and Mail sports columnist Cathal Kelly, who called Canada “just about the most marginal soccer country on Earth” in a recent column, says his appeal here is two-fold.

“He fulfills our most cherished national narrative – newcomer fleeing peril arrives in this country and makes good,” Mr. Kelly says in an email. And for a country with a history of being discarded by top athletes as soon as they are good enough, Mr. Davies committed himself as an international player here. “Davies is on the leading edge of a new generation of (non-hockey-playing) Canadian pros who want to wear the Maple Leaf. People respond to that.”

Perhaps more important, Mr. Davies has become an inspiration for any kid who might struggle, like those in Free Footie who are predominantly refugees, newcomers, and Indigenous youth – and stands as a reminder to society of the nurturing role it can play to help any child transcend. “His story and what he embodies is so perfect,” says Mr. Adams. “It just really shows that when you grind and you have characteristics that everybody can see, you’re going to be supported to get to some pretty amazing places.”

Mr. Davies addressed precisely those kids after his victory. “This one for everyone who is chasing a dream right now,” he tweeted. “Take it from me. Don’t give up. It may seem impossible now. But keep working on your craft. Keep grinding.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The peacemakers in Belarus

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In violent conflicts, peace often comes in unexpected ways, and directly from the work of women. Take note of what happened in Belarus after a rigged election on Aug. 9 resulted in peaceful demonstrations against dictator-president Alexander Lukashenko – and then a brutal crackdown by police on the protesters.

The violence brought thousands of women to the streets of Belarus. For days in mid-August, they wore white, held flowers aloft, and talked to the police. They held hands in long chains of nonviolent civil resistance. As the pro-democracy protests have continued and now include a wider range of people, the regime has been forced to switch tactics.

One leader of the women’s demonstrations, Maria Kalesnikava, explains why their use of symbols of peace and empathy – hugs, smiles, flowers, the color white – helped turn public opinion. “We decided to appeal to mutual respect and personal dignity,” she told the Atlantic Council. “These signs help to build respect between people.”

In Belarus, the “women in white” did step up to curb police violence, thus helping to widen the appeal of moving the country to democracy. Peace can indeed come in unexpected ways.

The peacemakers in Belarus

In violent conflicts, peace often comes in unexpected ways, and directly from the work of women. Take note of what happened in Belarus after a rigged election on Aug. 9 resulted in peaceful demonstrations against dictator-president Alexander Lukashenko – and then a brutal crackdown by police on the protesters.

The violence brought thousands of women to the streets of Belarus. For days in mid-August, they wore white, held flowers aloft, and talked to the police. They held hands in long chains of nonviolent civil resistance. Soon after, many workers in state factories went on strike. European leaders took notice and threatened sanctions against the regime for its violence.

As the pro-democracy protests have continued and now include a wider range of people, the regime has been forced to switch tactics. It is detaining or questioning protest leaders one by one. Much of Belarusian society is clearly no longer on the side of a violent ruler.

One leader of the women’s demonstrations, Maria Kalesnikava, explains why their use of symbols of peace and empathy – hugs, smiles, flowers, the color white – helped turn public opinion. “We decided to appeal to mutual respect and personal dignity,” she told the Atlantic Council. “These signs help to build respect between people.”

“For the last 26 years, authorities showed disrespect, humiliation, and intimidation to people in different positions. ... Anger, violence – it works for a very short term. Self-esteem, respect, love [is] something eternal,” she said.

In many countries where violence has erupted, the work of women often made a difference in peacemaking because many of them bring qualities of inclusiveness. Their role was pivotal, for example, in ending a civil war in Liberia, arranging cease-fires in Colombia, and toppling a dictator in Sudan. Based on studies, when women serve as mediators or signatories, peace accords are 35% more likely to last at least 15 years. Since 2000, when the United Nations began to focus on including more women in negotiating an end to violent conflicts, the portion of peace agreements that included a reference to women rose from 11% to 27%.

“We must not overlook the importance of increasingly involving women in peace building, because they’re rarely involved in causing the conflict in the first place,” says Nancy Lindborg, former president of the U.S. Institute of Peace.

In Belarus, the “women in white” did step up to curb police violence, thus helping to widen the appeal of moving the country to democracy. Peace can indeed come in unexpected ways.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Divine Love led me out of a riot

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Patrick McCreary

Unexpectedly caught in the middle of a riot, a man had this inspiration: “Just love.” The idea that nothing can overpower the Love that is God brought courage and the peace of mind he needed to safely leave the area, and the disturbance soon dissipated, too.

Divine Love led me out of a riot

Years ago I was invited to entertain at a national political nominating convention. It was a very hot summer’s day, and the venue was an open courtyard in front of a public building. Next to the venue was a large, concrete flood channel, which had been transformed into a makeshift tent city occupied by hundreds of people. They had come from all over the United States to demonstrate in support of various political agendas.

As I was performing, first a few, then almost all of the demonstrators climbed up out of the dry floodway and crashed the private party. Before long, there was an intense mass of flailing bodies and screaming voices. I was in the middle of a riot. I was startled; then I was afraid. Then I prayed, “God help me.”

In the midst of turmoil, hatred, and violence, my plea for God to help was answered through this inspiration: “Just love.” This was a surprising thought, considering the severity of the circumstances, but it was so strong that it gave me courage to carry on.

I had learned through my study of Christian Science that Love is another name for God, and that nothing can overpower this Love that is God. While teaching a group of pupils in 1898, Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, posed this question: “What is the best way to bring about an instantaneous healing?”

According to Irving Tomlinson, one of the students present; “There were many answers, but when they had finished, she said that it is to love, to be love and to live love. There is nothing but Love. Love is the secret of all healing, the love which forgets self and dwells in the secret place, in the realm of the real” (Irving C. Tomlinson, “Twelve Years with Mary Baker Eddy, Amplified Edition,” p. 104).

Guided by the divine directive to just love, I quietly and quickly packed up my gear and placed it on a dolly. The guests had already filled the reception patio by the time the demonstrators appeared, so the space was now almost impenetrably crammed. I gently started to push the equipment. I lovingly declared aloud to those around me, “Hello! Excuse me. Thank you. Excuse me.” When there was no way forward, I paused and prayed, eyes open, smiling out of gratitude that, despite what the material senses were seeing, divine Love was here and a very present help. Then another opening would appear, and again it was, “Excuse me. Thank you,” as I moved further forward.

There was considerable shoving and swearing around me, but at no time was a hand laid upon me or any of my equipment. I was still a bit anxious, but I did not fear the crowd, nor did I judge them as anything other than my brothers and sisters in Christ. Soon I found myself in the parking lot, which was free of people. I safely stowed the equipment and departed the scene.

But prayer continued. I began to forget self and feel a greater love for all the people I had just left. I affirmed that no one can be deprived of the inspired Word, the Christ, Truth, the scientifically sound understanding of God. I knew that denial or repression of the rights given to us by God isn’t God’s will; no one can be deprived of anything that God, Love, gives.

Tomlinson’s reminiscence goes on to report additional remarks by Mrs. Eddy from that day’s teaching on the subject of Love: “Love is a Shepherd who goes forth into the darkness of the night, into the storm and wind, to find the lost sheep. This Shepherd of Love leaves the beaten path, searches the wood and marsh, pushes aside the brambles, and seeks until the lost is found; then He places it within His bosom and returns to heal and restore” (pp. 103-104).

Later that night, I saw a television news report on this incident. There was no significant damage or injuries, and the disturbance dissipated almost as quickly as it had begun.

The Bible makes clear that God supplies all needs. God, Love, is ever present, inspiring us to think and act in ways that bless not only us but our neighbors as well, injuring none. The more we know of God, the more we know of our true, spiritual identity as His children and experience the influence of the gentle Christ, guiding us – and causing us to be a blessing.

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, July 9, 2020.

A message of love

A writer on the march

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about the rise of fish farming in the Gulf of Mexico.