- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Election anxiety: Democrat or Republican, Americans are feeling it

- Why Iran is poised to make a comeback ... as a US priority

- In Uganda, a lawyer helps pop star ignite ‘People Power’ movement

- When homework is least of your worries: How colleges help hungry students

- People are bad at predicting their emotions. Is that why we’re so polarized?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Asia’s pandemic success

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

An article in today’s Wall Street Journal asks an interesting question: Why is the West having so much less success handling COVID-19 than East Asia? Cases are spiking again in Europe, and America has long made little headway in containing the pandemic. Meanwhile, in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, “bars and restaurants are bustling, subway trains are packed and live concerts and spectator sports have resumed,” the Journal notes.

At the heart of the discrepancy, it seems, are differing views of liberty. Western views of liberty have for decades driven an unprecedented expansion of freedom worldwide, showing the power of human rights to uplift societies. But the coronavirus is showing how, in Asian democracies, citizens are using those liberties differently. They are putting their own personal preferences aside to serve a larger goal.

Francesco Wu, an Italian Chinese restaurant owner who grew up in Italy, tells the Journal: “Here we are used to having so many liberties – and that’s a great thing. But we are not as used to discipline, to self-sacrifice.”

As one office worker in Seoul, South Korea, tells the Journal, he hates wearing a mask, but “I would rather make sacrifices.” In that way, East Asia is seeing COVID-19 restrictions not as an imposed burden, but as the expression of a genuine desire to act effectively together.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Election anxiety: Democrat or Republican, Americans are feeling it

With two weeks to go, most Americans are worried about the presidential election, polls suggest. But what worries them differs – and speaks to the nation’s different lenses.

A startling 70% of voters believe our democracy is “in danger” in this election, one October poll found. In another survey, more than two-thirds of U.S. adults say the 2020 election has become a significant source of stress in their lives. And perhaps predictably in this era of stark polarization and perception gaps, Democrats and Republicans frame their anxieties in nearly inverse ways.

Americans are thinking not only about the pivotal choice that will determine the direction of the country, but also about the very fabric of its political traditions, including its decentralized and state-varying ballot boxes.

“I have never, not for a fraction of a second in my entire life, worried about the security and validity of an election until now,” says Michelle Deininger, who has voted regularly since she was 18. “And that’s just such a foreign, eerie, un-American feeling.”

“For better or worse, there is a lot of onus on voters this election cycle to be their own greatest advocates,” says government professor Mara Suttmann-Lea, “to know their rights, to know what the follow-up process is for casting mail ballots.”

Election anxiety: Democrat or Republican, Americans are feeling it

Like millions of other Americans, Michelle Deininger has found herself deeply frazzled about the presidential election this November.

A stay-at-home mother and self-described RINO, or “Republican in name only” living in Park City, Utah, she notes how the global pandemic, reeling economy, and ongoing eruption of civic unrest following the killings of George Floyd and others have now also become the nerve-wracking backdrop to one of the most momentous elections in her lifetime.

“I’m 52 and I’ve been voting since I turned 18, and I have never, not for a fraction of a second in my entire life, worried about the security and validity of an election until now,” says Ms. Deininger, a lifelong Democrat from Boston who switched parties two years ago to have a voice in her new Republican-dominated state. “And that’s just such a foreign, eerie, un-American feeling.”

Across the political spectrum, a host of Americans have been expressing similar anxieties, not only about the pivotal choice next month that will determine the direction of the country, but also about the very fabric of America’s political traditions, including its decentralized and state-varying ballot boxes.

A startling 70% of voters believe our democracy is “in danger” in this election, an early-October Fox News poll found, including about 8 in 10 supporters of the Democratic candidate, former Vice President Joe Biden, and 6 in 10 supporters of President Donald Trump. Over two-thirds of U.S. adults, too, say the 2020 election has become a significant source of stress in their lives, according to a survey by the American Psychological Association in early October.

Utah, like many states out West, has long had a robust tradition of mail-in voting. Each election it sends all active registered voters a ballot that can either be mailed or dropped off early at a designated location – like the grocery store where Ms. Deininger cast her ballots in 2018 and this year’s primary.

She didn’t give the system a thought in those elections, she says. But with President Trump undermining confidence in the processing of an expected record number of mail-in ballots across the country, for the first time she double-checked her voter registration, and for the first time she’s considering volunteering to be a poll worker.

“I was horrified and alarmed during the presidential debate when the president urged his supporters to go to polling places and watch closely,” she says. “And I was even more horrified and disturbed at the admonition, exhortation, for the Proud Boys to ‘stand back and stand by.’ This is a very red state, and I just don’t even know, will there be armed supporters, threatening, trying to intimidate?”

Just as she’s speaking, she notices breaking news that the FBI had arrested 13 men involved in an anti-government militia that was plotting, officials say, to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, take her to a “secure location,” put her “on trial” for violating the U.S. Constitution, and foment “a civil war leading to societal collapse.”

“It’s just like we’ve turned into another country,” Ms. Deininger says.

How the economy looks to you

Perhaps predictably in this era of stark polarization and perception gaps, Democrats and Republicans frame their anxieties in nearly inverse ways.

“I’ve been really concerned that there will be irreparable harm to the American economy if it continues to stay shut down any longer,” says James Linzey, chief editor of the Modern English Version of the Bible and a former military chaplain living in Escondido, California. “It’s going to be a fight, but if Joseph Biden is elected, I just fear the worst – and I will consider selling my house and getting out of California,” as other Republicans have already said this year.

He’s been both a supporter and admirer of President Trump from the start, and his enthusiasm for the president has hardly waned. “Fortunately, President Trump has had the wherewithal to try to reopen the economy or encourage the economy to open back up in the states.”

But Mr. Linzey has lost faith in most of the country’s news media and scientific institutions, which he sees as havens for liberal thought and deliberate deception. “I am not concerned about Donald Trump losing the election. The polls were wrong in 2016, and I think the polls are wrong again, too,” he says.

How the pandemic has been managed

Eric Mingott, a financial adviser from Queens who used to be active in the borough’s Republican circles, changed his registration to become an unaffiliated independent earlier this year. His primary concern has been the president’s handling of the pandemic. His preexisting medical conditions, he says, make him especially vulnerable to the coronavirus.

“Beforehand it was the economy, or the principles of foreign policy,” says Mr. Mingott, a first-generation American whose parents emigrated from Peru. “Now it’s all about whether or not COVID can end, or how we can control it.”

Born and raised in East Elmhurst, Queens, he, like thousands of New Yorkers, moved to a suburb in Long Island earlier this year, frustrated with the onerous municipal burdens of living in a Democratic-run city and a neighborhood that was a COVID-19 hot spot last March.

“So now, how do we provide for the safety and quality of this election?” Mr. Mingott says. If mail-in ballots are part of the solution, “even though states have been doing it for a long time, the question is, are we capable of doing this with millions of ballots? Will every vote be counted? Will there be a lot of fraud?”

Having a voting plan

Mara Suttmann-Lea, professor of government at Connecticut College in New London, has been planning a community talk titled “What to expect when you’re expecting an election meltdown” – though she says, for the record, she’s certainly not saying 100% there will be such a meltdown.

“Just observing some of the messaging coming out of the Biden campaign and coming out of the [Democratic National Committee], there has been a shift away from the voting-by-mail piece and toward, have a plan, vote early if you can, and really, you know, encouraging voters to do what they can to limit the stress on the system on Election Day.”

That is the plan for Lori Morton, lead coordinator for career services at Broward College in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. She’s a registered Democrat and member of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, the same network of Black women to which vice presidential nominee Kamala Harris belongs.

“I’ve been worried about the mail-in voting probably more than anything else,” Ms. Morton says, noting that the current postmaster general, Louis DeJoy, has personally contributed millions to President Trump and the Republican Party. This year, he has directed the removal of more than 700 sorting machines across the country, nearly twice the average number removed each year from 2015 to 2019.

“But my circle – and I have a large circle, have several circles – we are not mailing anything in,” says Ms. Morton, who also has a private practice as a therapist and counselor. “We’re bypassing the post office. Folks are planning to take their ballots to a supervisor of elections office or taking it directly to a polling place.”

In her practice, she says, she is finding that her clients have been expressing more feelings of anxiety than in past years, and she has been treating a much higher number of people experiencing panic attacks.

“I think that people are just so polarized and just so angry for a variety of reasons, whether they’re founded or unfounded,” she says. “If the Republican Party wins, there’s going to be folks in the street. If the Democratic Party wins, there’s going to be folks on the street. I don’t see any way around that.”

President Trump, too, has declined to say he would accept the election results given what he sees as the many risks of mail-in ballots.

Bipartisan fraud, if any at all

Mail-in ballots do have certain built-in vulnerabilities, say experts including Hans von Spakovsky, manager of the Election Law Reform Initiative at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank in Washington, D.C.

They are the only kind of ballots that are cast outside the supervision of election officials, he says, which makes them vulnerable to everything from being stolen out of people’s mailboxes to voters in their homes being vulnerable to coercion and intimidation by others.

“But even apart from that … the rejection rate for absentee ballots again is much higher than for ballots cast in person,” Mr. von Spakovsky says. “People forget to sign the ballot; they don’t provide all the information you’re supposed to provide. Sometimes the Postal Service, in addition to potentially not delivering it on time, forgets to postmark the envelope.”

And while the impact of fraud may be negligible in presidential elections, and though wide-scale voter fraud is extremely rare, most experts say, in the hosts of down-ballot races, winners are often determined by a small number of votes.

“The one thing I can tell you is that election fraud, when it occurs, is bipartisan,” he says. “It’s committed by people of both political parties, and it’s not always one party stealing from another. Sometimes it’s people in the same political party stealing from each other.”

But both he and others say that in this election, it’s critical that voters casting mail-in ballots have a laserlike focus on the details.

“I think the other thing that really flummoxes folks is the amount of variation there is in election procedures,” says Professor Suttmann-Lea. “For better or worse, there is a lot of onus on voters this election cycle to be their own greatest advocates, to know their rights, to know what the follow-up process is for casting mail ballots.”

Why Iran is poised to make a comeback ... as a US priority

U.S.-Iran relations have vexed many presidents, but whoever manages them during the next four years will face more than just the nuclear question.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Whoever wins the U.S. presidential election, there is reason to expect that policy toward Iran will return to a place of privilege on the foreign policy agenda. Perhaps soon.

Among the indicators: the expiration of an international arms embargo on Iran over the weekend, recent advances in Iran’s nuclear program, and the prospect that under a President Joe Biden, the United States would return to the multilateral Iran nuclear deal.

Yet many staunch critics of the 2015 deal worry that Mr. Biden, looking to quickly rejoin the agreement, would squander the position of strength the Trump administration has developed vis-à-vis Iran through his “maximum pressure” policy.

“We must not throw the regime a lifeline [or] return to the policies of appeasement,” says Robert Joseph, special envoy for nuclear nonproliferation under President George W. Bush.

But others say the Iranians understand that the dire economic and political straits the regime is in mean they would have to compromise with whoever is in the White House in 2021.

“The Iranians know they’d have to make some concessions,” says Alex Vatanka at the Middle East Institute in Washington. “And that’s an opportunity.”

Why Iran is poised to make a comeback ... as a US priority

Iran – that burr under the saddle of U.S. presidents and presidential aspirants alike since 1979 – may not have much of an irritating presence in this year’s presidential campaign.

Indeed, with the focus on big domestic issues, including the handling of the coronavirus pandemic, no foreign policy topic is getting much traction.

But that doesn’t mean Iran is altogether absent, or that it’s not poised to come roaring back no matter who takes office in January. It could even happen sooner.

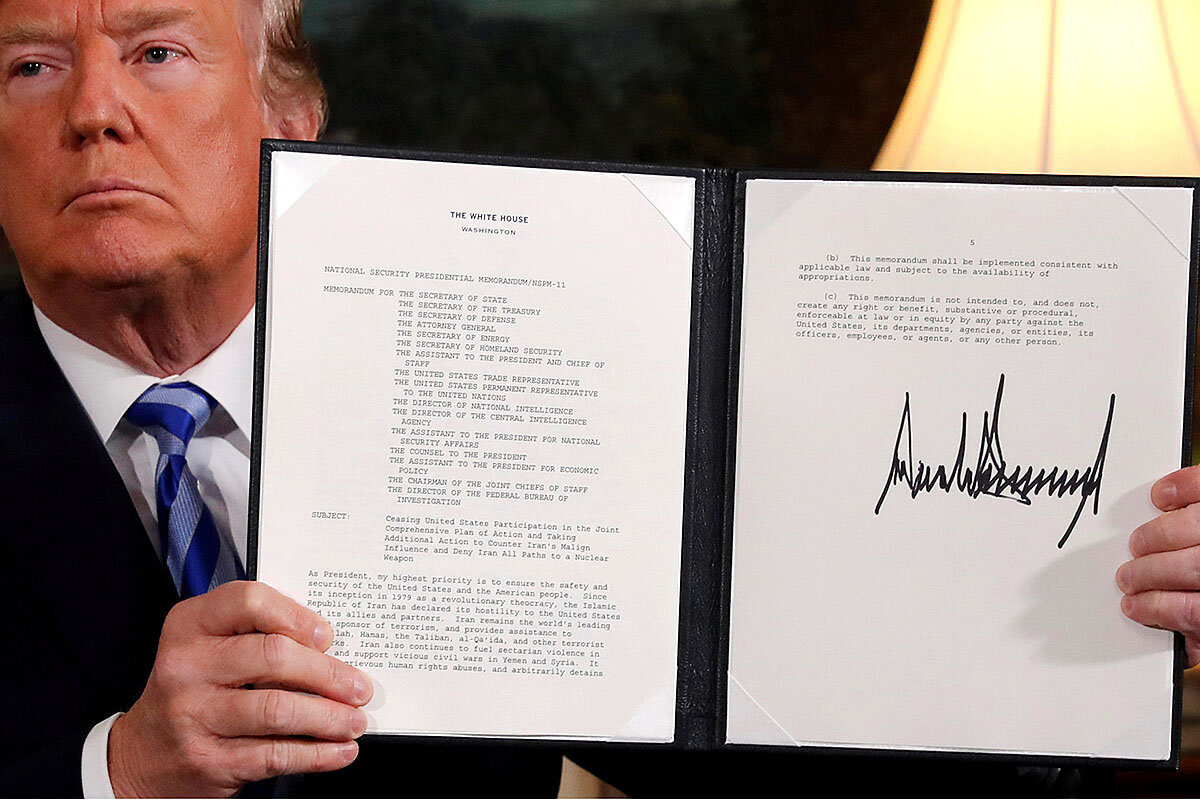

Several indicators suggest Iran could soon return to a place of privilege on the U.S. foreign policy agenda. These include the expiration of an international arms embargo on Iran over the weekend, recent advances in Iran’s nuclear program despite President Donald Trump’s sanctions-based “maximum pressure campaign,” and prospects under a potential Joe Biden presidency for the United States to return to the multilateral 2015 Iran nuclear deal.

But with a difference.

“There are a number of reasons to think Iran is poised to come back” to the agenda once the election is over, “but it’s not going to be the same debate, with the same focus on the nuclear issue to the exclusion of everything else, that we had five years ago,” says Alex Vatanka, director of the Iran Program at the Middle East Institute (MEI) in Washington.

For starters, “the big change looking over the last five years is that Iran has become so weak that it has become much easier for the Chinese – and the Russians – to use the Iranians as a pawn to undermine U.S. interests,” he says.

At the same time, the nuclear issue, while critical, no longer has a monopoly on what makes Iran a looming foreign policy concern for the U.S. “No matter who wins [the U.S. election] in November, the approach will no longer be limited to how many centrifuges [the Iranians] have,” Mr. Vatanka says. “It will have to be a much broader conversation,” including Iran’s regional activities – what the Trump administration calls “exporting revolution.”

On Sunday, a United Nations arms embargo the Trump administration said was critical to limiting Iran’s mischief in the region expired. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reiterated the U.S. position that the embargo remains in effect – and warned that the U.S. will sanction any company that sells arms to Tehran.

The U.S. position sets the stage for a damaging confrontation between the U.S. and some of its closest allies in Europe – the United Kingdom, France, and Germany – that remain parties to the formally titled Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA. They insist that the U.S. withdrawal from the deal nullifies any U.S. say over its provisions.

Also promising Iran’s return to the international agenda is evidence of progress in the country’s nuclear program. Recent International Atomic Energy Agency reports indicate that Iran’s “breakout” time to building a nuclear weapon is just three or four months, in part based on estimates of stockpiled fissile material.

That estimate is down sharply from the one-year breakout time experts assessed when President Trump pulled the U.S. out of the JCPOA in 2018.

In addition, last week a dissident group with a good track record exposing secret nuclear R&D facilities inside Iran reported the existence of what it said is a previously undisclosed military facility dedicated to Iran’s nuclear program. The National Council of Resistance of Iran said in Washington Friday that satellite imagery shows the facility, located in a military zone east of Tehran, has recently been expanded.

Even if Iran has not figured prominently in the presidential campaign, what has been said suggests stark differences between the policies of a second-term President Trump and those of a President Biden.

Moreover, those differences are also an indicator of the broad foreign policy strategies and goals each would pursue.

On Iran as well as on other issues, Mr. Trump would be expected to double down on sanctions and confrontation with allies to advance his foreign policy goals. Those goals for a second Trump administration would include more tightening of the screws on Tehran to force a return to negotiations and achieve what Mr. Trump insists would be a better deal.

Mr. Biden, on the other hand, would likely return the U.S. to a multilateral route, seeking to quickly repair relations with key allies in an effort to address international challenges including the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change – and Iran’s advancing nuclear program.

Indeed, a Biden administration would likely seek to return the U.S. to the JCPOA – the question would be under what conditions. Some Biden aides have indicated that a Biden administration would condition a U.S. return to the nuclear deal on certain adjustments.

Jake Sullivan, a former national security adviser to Mr. Biden when he was vice president, said in an August webinar that a President Biden would follow the same “formula” used by the Obama administration – which he described as “leverage diplomacy backed by pressure” – to coax the Iranians back to the negotiating table.

The goal, he added, would be a new deal with Iran that makes “progress, not just on the core nuclear issues but on some of the other challenges as well,” including Iran’s missile development and support for regional proxies.

Some Republican national security experts say a Biden administration would be wise to use the “leverage” Mr. Trump’s policies have built up on a number of key foreign policy issues, including Iran.

Through frequent recourse to sanctions and threats to end security guarantees, “Trump has generated considerable leverage over adversaries and allies alike,” including Iran, writes Richard Fontaine, former foreign policy adviser to the late Sen. John McCain, in the October issue of Foreign Affairs. “A Biden administration would ... do well to use some [of the leverage] Trump would leave behind.”

Nevertheless, many staunch critics of the JCPOA worry that Mr. Biden, looking to quickly rejoin the nuclear deal, would squander the position of strength the Trump administration has developed vis-à-vis Iran.

“We must not throw the regime a lifeline [or] return to the policies of appeasement,” says Robert Joseph, who was special envoy for nuclear nonproliferation under President George W. Bush.

But others say the Iranians understand that the dire economic and political straits the regime is in mean they would have to compromise with whoever is in the White House in 2021.

“The Iranians know they’d have to make some concessions on the regional front, and maybe even on the bad things they are doing at home to their own people,” says MEI’s Mr. Vatanka. “And that’s an opportunity.”

In Uganda, a lawyer helps pop star ignite ‘People Power’ movement

Can an upstart rapper-turned-politician defeat one of Africa’s longest-serving autocrats? That could depend on people like Lina Zedriga, who’s tasked with changing minds across Uganda.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Liam Taylor Correspondent

A year ago, Ugandan lawyer and women’s rights activist Lina Zedriga was thinking about retirement.

So much for that.

Today, Ms. Zedriga is party deputy to Bobi Wine, the Ugandan singer who has become the leading political challenger to longtime President Yoweri Museveni. Mr. Wine’s People Power movement is messy, vibrant, and unpredictable, galvanizing people with the loose promise of change. But he faces fierce pushback – and with elections early next year, he has no time to lose.

Mr. Wine has to win support in the countryside, where three-quarters of Ugandans live. And in March he asked Ms. Zedriga to help him do it. To her, it’s an extension of her activism. “Empowered women transform societies,” reads a sign above her desk.

Politics is a murky business, as Ms. Zedriga knows. Her husband disappeared after the 2001 election, when he was a campaign manager for the main opposition candidate. The government said he had fled to join a rebel group. She still holds out hope that he is alive somewhere.

But even as the screw tightens in Uganda, she is optimistic. “This is the moment when everybody’s feeling enough is enough – enough of the impunity, enough of the injustices, enough of the exclusion,” she says.

In Uganda, a lawyer helps pop star ignite ‘People Power’ movement

Lina Zedriga thought she was done with politics. As a lawyer and activist, she had fought for women’s voices to be heard everywhere in Uganda, from land disputes to peace negotiations to parliament. And now she wanted to go home to the north. Become a catechist. Keep goats. Rest.

One day in February she changed her mind.

Bobi Wine was in court in Kampala, the Ugandan capital, accused of organizing an illegal protest. The singer-turned-politician, whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi, is the leading opposition candidate for president in elections early next year.

Ms. Zedriga, who was there to watch another case, saw Mr. Wine leave the courthouse into a throng of raucous fans. Suddenly the police fired tear gas. Elsewhere that day one of Mr. Wine’s supporters was killed in a road accident – knocked dead by a police car, said Mr. Wine, which the police deny. “We went for the burial,” recalls Ms. Zedriga, “and one of the messages this young girl left was let me not die in vain.”

Since 1986 Uganda has been led by Yoweri Museveni, a former rebel. He has won five elections, on a steeply tilted playing field, and retains some genuine support. Most Ugandans expect him to triumph again in 2021. But Mr. Wine’s candidacy is sparking excitement. At 38, he is half Mr. Museveni’s age. His People Power movement has drawn in student radicals, seasoned politicians, and the young strivers of the city, who scrape a living selling vegetables or riding motorbike taxis.

The movement is messy, vibrant, and unpredictable, galvanizing people with the loose promise of change. In its unofficial anthem, a reworking of a Pentecostal hymn, Mr. Wine paints a vision of a “new Uganda” free of corruption, tear gas, and land grabs, where everyone will “walk with swag.”

But Mr. Wine faces fierce pushback. In 2018 he was arrested, beaten, and charged with treason, along with 35 of his supporters. Last week the army and police raided his headquarters, and on Wednesday a judge will rule in a case challenging his leadership of his party, the National Unity Platform (NUP). His critics sneer that he is inexperienced and lacks ideas.

If Mr. Wine is to threaten Mr. Museveni, he has to win support in the countryside, where three-quarters of Ugandans live. And in March he asked Ms. Zedriga to help him do it. She is now his deputy and the northern coordinator of the NUP, a role she sees as an extension of her gender activism. “Empowered women transform societies,” reads a sign above her desk.

“Let us see how our political participation translates into salt for the women, into the five hundred shillings which we usually tie around our kitenges [fabric wraps],” she says, a rosary around her neck. She has returned to the north after all: not to keep goats, but to build a movement.

Reclaiming humanity

Uganda did not exist until British colonialists created it. Like shoddy welders, they fused together a disparate group of kingdoms and societies. Sometimes, the nation has pulled apart at the seams.

After independence northerners dominated Uganda’s army and, by extension, its politics. The ascent of Mr. Museveni, a southwesterner, ushered in peace in the south but violence and social breakdown in the north – most notoriously the rebellion of Joseph Kony, a self-proclaimed spirit medium, and his Lord’s Resistance Army. The government herded nearly 2 million people into displacement camps, and it was not until 2006 that peace started to return.

“In the north we have never been beggars,” says Ms. Zedriga, who as a lawyer collected statements from women raped in the war. “Now we have generations that are beggars. So our agenda for northern Uganda is let us wake up, reclaim our identity, reclaim our humanity.”

Samuel Obedgiu agrees. When he was 11, he was abducted by Mr. Kony’s rebels, spending nine months in the bush. At university in Kampala he became a protest leader, earning the nickname “Strike Machine.” He now leads NUP’s youth wing in the north, working with Ms. Zedriga from NUP’s new office in Gulu town. He says he is using a “termite strategy” to reach voters, going “underground” like the wood-eating insects.

One morning in September he rides a hired motorbike to a homestead in Nwoya district. Villagers trudge in from the fields and gather beneath a mango tree, still dripping from the morning rain.

“Where should we go as Acholi?” Mr. Obedgiu asks, referring to the Acholi people who live in the area. “What should be the future for our children?”

They work hard to pay school fees, he reminds his audience, but in Kampala their children only find jobs as watchmen and maids.

The crowd murmurs agreement. But they have heard this message from opposition politicians before. They have done their best to vote for change, says one woman, but the rest of the country lets them down. A young man in a faded soccer shirt suggests they should focus on local leaders, because there is no hope of changing the president.

Another man, though, gestures at Mr. Obedgiu’s T-shirt, emblazoned with Mr. Wine’s face. “That one. We want to try him.”

Uphill battle

Mr. Museveni’s government leaves space for the opposition – just not enough for them to win. The press, though constrained, is lively. Elections, though flawed, are fiercely fought.

But politics is a murky business, as Ms. Zedriga knows. Her husband disappeared after the 2001 election, when he was a campaign manager for Kizza Besigye, the main opposition candidate. The government said he had fled to join a rebel group. She still holds out hope that he is alive somewhere.

And politics is dirty too. Ms. Zedriga claims that she was recently at a cafe in Kampala when she was approached by a soldier and a lawyer, promising her a government job, two cars, and 5 billion shillings ($1.3 million).

“I held my bowl of soup,” she says, breaking into characteristic laughter. “I almost poured it on them!”

The screw is tightening. Security officials stopped NUP from opening an office in Kitgum, another northern town. Mr. Obedgiu and Brian Mungu, a parliamentary candidate, say they have been arrested while campaigning. Mass rallies have been banned to stop the spread of COVID-19, a rule that the opposition says is selectively enforced.

Jimmy Patrick Okema, a police spokesman in Gulu, insists that the rules apply equally to all. “As long as you do something that is contrary to the guidelines we shall not entertain that,” he adds.

The candidates milling around NUP’s Gulu office are passionate but inexperienced – and struggling for funds. Lalam Irene is a radio host and singer who says she wants to empower women and heal Uganda’s “wounded politics.” Charles Ochora is a businessman who only joined NUP after losing in the ruling-party primaries in September. Caesar Lubangakene, a snappily dressed humanitarian worker, is running for office in Gulu East; among his rivals is the local priest, running as an independent.

“NUP will not do well in northern Uganda,” says Peter Labeja, who hosts a political talk show on Radio Rupiny, a government-owned station. Local support for the ruling National Resistance Movement has increased since the end of the war, he notes. “[There is] a general appreciation that Museveni is going nowhere for now.”

But Ms. Zedriga no longer thinks of retirement. “This is the moment when everybody’s feeling enough is enough – enough of the impunity, enough of the injustices, enough of the exclusion,” she says. “I am very optimistic.”

Arthur Owor contributed reporting from Gulu.

When homework is least of your worries: How colleges help hungry students

As colleges see students with basic needs beyond just education, many are trying to help in creative ways.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Kelly Field Correspondent

Even before the pandemic, there were tens of thousands of college students without stable housing or enough to eat. Job losses in the restaurant and retail sectors, where many students find work, only made things worse. Some students are months behind on rent with a federal eviction moratorium set to expire at the end of the year. But colleges are finding new ways to respond.

Marcy Stidum, who created Kennesaw State University's program for students who have experienced homelessness and foster care, started training professors on how to spot the warning signs of food and housing insecurity, such as a reluctance to turn on video for online classes. The university has also encouraged course syllabi that includes information for students to access basic needs.

Students are stepping up, too, creating matching programs for students and faculty to share resources with those in need. On some campuses, students have built mutual aid networks, raising emergency funds for classmates.

Sara Goldrick-Rab is director of the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice at Temple University, which researches college students and the challenges to completing their education. “There are things we’ve been asking for, for a long time, that are starting to happen,” she says.

When homework is least of your worries: How colleges help hungry students

Before the coronavirus shut down his school and workplace, things were looking up for Nicholis Perez, a student at Florida State University.

The start of his freshman year had been rough, to be sure. He’d spent his first two months in Tallahassee sleeping in his 1996 Ford Ranger and working 40-hour weeks at a pizza joint, trying to save money for an apartment.

But by the end of the fall semester, Mr. Perez had moved in with a friend and advanced to a job at a fine dining restaurant. This past March he purchased a 2013 Hyundai Veloster: “The first car I ever bought that was younger than me.”

Two weeks later, his life was upended. With coronavirus cases on the rise, the restaurant closed, leaving Mr. Perez short on rent. He asked his landlord – his friend’s father – for an extension, and says he got one. But less than a week after the conversation, he returned to the apartment to find the locks changed and his stuff on the street. A note on the door said the family had moved back to Miami.

“It was pretty devastating,” he recalls. “At least I had the new car to live in. That was a lot better.”

Even before the pandemic triggered widespread unemployment, there were tens of thousands of college students without stable housing or enough to eat. Job losses in the restaurant and retail sectors, where many students find work, only made things worse. Now, some students are months behind on rent with a federal eviction moratorium set to expire at the end of the year. With federal aid from the coronavirus relief bill mostly depleted, and potentially a tough winter ahead, colleges are finding new ways to respond.

“There are things we’ve been asking for, for a long time, that are starting to happen,” says Sara Goldrick-Rab, director of the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice at Temple University. “We really are seeing the faculty lean in, asking ‘How do I communicate care?’”

To help students find resources easily, colleges are creating basic needs websites, and professors are adding information about available supports to course syllabi, Dr. Goldrick-Rab says. They are also reaching out in more personal ways.

Florida State, which offers a program for students who have experienced homelessness or foster care, held its freshman mixer online this year, delivering restaurant meals to students’ homes so they could eat together, apart.

A need-seeking majority

Nearly 3 in 5 college students were experiencing basic-needs insecurity in the spring, according to a recent survey by the Hope Center. The rates for Black and Hispanic students were even higher, at 71% and 65%. Colleges responded at that time with millions of dollars in aid to students, including from the federal relief bill. They gave institutional grants to international and undocumented students, who were ineligible for the federal aid.

After abrupt closures, many let students remain on campus if they had nowhere else to go. Some schools kept a dining hall open, with limited hours; others handed out gift cards to grocery stores; or let students order from the food pantry online, rather than shopping in person. Staff delivered groceries to students who lived off-campus, without transportation, and helped students who had left the area find food in their communities.

Some colleges even recruited faculty to help them find students experiencing food and housing insecurity. At California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, administrators asked faculty to flag students who seemed in need of additional support. At Kennesaw State University, in Georgia, staff trained professors on how to recognize the warning signs of food and housing insecurity in online classes, such as a reluctance to turn on video.

With students back on campus this fall, the college has started sending food to mailboxes at its Marietta campus, so students who place an order online don’t need to come to the Kennesaw food pantry to collect it.

Still, without walk-ins, Kennesaw’s pantry isn’t serving nearly as many students as it normally does, says Marcy Stidum, who created and now directs the college’s program for students who have experienced homelessness and foster care. She attributes the roughly 40% drop to students and faculty spending less time together in person this year, since some classes are online.

“We’re missing people that we know would have been referred to us if it weren’t for COVID,” Ms. Stidum says. “It’s like Horton and the Who, where we’re shouting, ‘we are here, we are here!’”

Students step up for classmates

Seven months after the relief bill cleared Congress, the future of a second economic relief bill is uncertain. Many public colleges face budget cuts that will make it harder for them to meet students’ needs going forward.

So, students are stepping up, too, creating spreadsheets and matching programs that let students and faculty share resources with those in need. On some campuses, students have built mutual aid networks that have raised thousands of dollars in emergency aid for their classmates.

“We know that there are quite a few students who can pay the full cost of attendance,” says Yannik Omictin, a senior at George Washington University who helped start its mutual aid network. “We figured what we can do here is redistribute some of that money.”

Meanwhile, Mr. Perez, the Florida State student, is back at work at a local cafe and able to afford an off-campus apartment. His lease is up in December, but he’s not feeling too stressed about it. He says he knows his school will help him find housing and employment if he loses them again.

“As long as I keep going through school, working hard, I think I’ll be OK,” he says. “I’m pretty resilient.”

People are bad at predicting their emotions. Is that why we’re so polarized?

Human beings’ persistent inability to judge what will make them happy affects everything from political polarization to the pandemic, research suggests. But a little perspective can help.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Svoboda Correspondent

You would think that, if there’s anything we humans can easily understand, it’s our own minds. But, as a mountain of studies reveal, we’re not quite as adept at reading ourselves as we might think. In particular, we’re not very good at predicting how a future event will make us feel.

Psychologists call it “affective forecasting,” the ability to foretell our own happiness, sadness, and other emotions. We’re actually pretty good at predicting how intense our feelings will be after a watershed event like an election victory or a job loss. But when we try to predict how those feelings will persist over time, and how they’ll affect our overall mood, we’re often way off the mark.

This misperception may be one factor driving political polarization. Many people tend to think that digesting opposing political views will upset them more than it actually does.

“You think that if your team or your candidate loses, you’re going to be very miserable for a long time,” says New York University marketing professor Tom Meyvis. “But it doesn’t last that long.” Likewise, if you win an award or get a great grade on a test, your happiness will probably evaporate sooner than you think.

People are bad at predicting their emotions. Is that why we’re so polarized?

A professor hunches at her desk until the wee hours, churning out the academic papers she needs for tenure. A sports fan trembles with anxiety as her football team takes the field. A campaign official loses sleep over the prospect of his candidate coming up empty.

These high-stakes scenarios rest on the same common assumption: Achieving the desired outcome (tenure, a team championship, an election victory) will ensure lasting happiness, and falling short will breed deep despair. All of us engage in this kind of “affective forecasting” – predicting how we’re going to feel in the future.

But as researchers are discovering, we’re not nearly as good at it as we think. Studies show that, time after time, our predictions about what will make us happy and what will upset us miss the mark. As the pandemic takes a toll on collective emotional well-being – a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey conducted in June found that more than 40% of Americans reported adverse mental health – it might be time to reassess our assumptions about happiness. Understanding the nature of forecasting mistakes, and why they occur, can give a clearer sense of when to believe emotional predictions and when to take them with a big grain of salt.

“You think that if your team or your candidate loses, you’re going to be very miserable for a long time,” says New York University marketing professor Tom Meyvis. “But it doesn’t last that long.” Likewise, if you win an award or get a great grade on a test, your happiness will probably evaporate sooner than you think.

Not only do we tend to oversell how much a future event will affect our happiness, we exaggerate how long the impact will last. In a 2019 study, Texas A&M University psychologist Heather Lench and her colleagues asked groups of people how they thought they’d feel in two different scenarios: if their candidate won or lost an election, or if they got an unexpectedly high or low grade on an exam.

Respondents accurately predicted their emotions’ intensity in these situations, but they weren’t nearly as good at predicting how those emotions would evolve over time. Most of the time, initial feelings dissipated and didn’t affect people’s overall moods as much as they thought.

Humans’ frequent emotional forecasting mistakes can affect beliefs and perceptions in surprising ways. Last year, public policy experts at Harvard’s Kennedy School found that these errors help explain why society is so politically polarized. We think digesting opposing views will upset us more than it actually does, so we avoid those views, consuming mostly content we already agree with – a habit that’s hard to dislodge once it gets entrenched. But when we correct our false affective forecasts, we’re less apt to seek out biased political information.

Down memory lane

Overall, we learn swiftly from our mistakes: Almost no one who’s touched a hot stove needs to be reminded not to do it again. But when it comes to emotional forecasting, we aren’t as quick to catch on. You might think that staying in bed until noon on Saturday will make you happy. But even if it makes you feel like garbage (stinking garbage, to boot), you might still be tempted to linger under the covers next weekend.

It isn’t that we consciously resist learning from our poor forecasts, says Professor Meyvis. It’s that we often don’t have a clear sense of what those forecasts were in the first place. In a series of studies, he and his team showed that people tend to misremember their happiness predictions, revising them to match what reality turned out to be.

If a financial windfall doesn’t make you as happy as you initially thought, for example, you might assume that you foresaw this disappointment all along. “It’s tempting to think of memory as opening a little drawer and retrieving the memory, but that’s not what happens,” Professor Meyvis says. “You’re going to try to reconstruct your feelings based on what your current feelings are.” This under-the-hood reconstruction prevents you from realizing that your initial predictions were way off the mark – and when you’re not fully aware of making a forecasting mistake, you’re not motivated to correct it.

Like scientists peering through a microscope, most people also engage in what’s called “focalism” when predicting how an event will make us feel. That is, we focus so intently on that event that we gloss over the impact of all the other events that will happen around the same time. When you think about how sad you’ll be if you get fired, or if your candidate loses an election, you probably are not thinking about how you’ll feel if you make a new friend, summit a mountain, or have your first grandchild in the near future.

In reality, though, a never-ending parade of life events – some good, some bad, some neutral – reduces the impact of any single event on your well-being. “When you actually get there, there are a lot of other things happening, too,” says Professor Lench. “One outcome doesn’t affect all of life. You have other goals and priorities that are also important.”

The bright side of bias

Even so, some researchers argue that it might not be wise to try to correct all our emotional forecasting errors. From an evolutionary perspective, they say, there are good reasons we make these kinds of mistakes over and over.

When we exaggerate the emotional toll of a future negative event, we pull out all the stops to make sure that event doesn’t happen. And believing that reaching a goal will bring fulfillment – whether that goal is securing tenure, saving enough to buy a home, or catching a boatload of fish – helps ensure that we survive and thrive. “When you’re thinking about how intensely happy you’ll be when you receive tenure, it keeps you going,” Professor Lench says.

People who err on the sunny side in forecasting their feelings might also be better at dealing with obstacles in everyday life. Desirée Colombo, a doctoral candidate at Spain’s Universitat Jaume I, asked people to predict what they thought their mood would be over the next two weeks. Then her team checked in with them three times a day during that time period. People who predicted brighter moods than they actually experienced “were more resilient and had better mental health,” Ms. Colombo says.

So how do you know if you should go with the flow of your emotional forecasts or push back on them? One wise approach, experts say, is to gain some perspective on your forecasts by looking to your feelings about them. If anticipating great joy after finishing a presentation inspires you to power through it, your overoptimism might be a positive influence.

On the other hand, if you’re constantly making yourself miserable by predicting future doom – or sacrificing your present well-being to ensure future happiness – it’s time to step back and assess your forecasts against the broader backdrop of the rest of your life. Almost no triumph will bring as much enduring happiness as we think, and almost no setback is as emotionally devastating as we fear.

“To the extent that we realize, ‘This has happened to me before and I survived,’” Professor Meyvis says, “that’s a good thing.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Chile’s choice to reinvent itself

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Chile is poised to embark on what may establish a model for Latin American countries grappling with the effects of anti-democratic behavior. On Sunday voters will decide in a referendum whether to draft a new constitution. The question follows nearly a decade of mass protests over various inequities from tuition fees to health care. It is expected to pass with overwhelming support. That will start a two-year national process leading to a new political framework and social compact.

Chile has been one of the region’s most effective countries in addressing economic inequality. But perhaps because of such rising expectations, it has seen waves of mass protests that reflect a society convinced of the opposite. Demonstrations over the past year finally forced the government to call the referendum. The Sunday vote, delayed six months by the pandemic, has raised expectations that a new balance can be found between individual and collective prosperity.

If Chile can reinvent itself with a new constitution, it might help put an end to violent overthrows in a region still struggling to operate through consensus and equality.

Chile’s choice to reinvent itself

Over the past 120 years, 163 governments in Latin America have been overthrown. More often than not, one coup d’état led to another. In 1955, Argentina had three. Between 1920 and 1982, Bolivia had one on average every three years. The recovery from such anti-democratic actions can take decades.

Now Chile is poised to embark on what may establish a model for countries grappling with the long-term effects of such political earthquakes. On Sunday voters will decide in a referendum whether to draft a new constitution. The question follows nearly a decade of mass protests over various inequities from tuition fees to health care. It is expected to pass with overwhelming support. That will start a two-year national process leading to a new political framework and social compact.

It is potentially a remarkable experiment in peaceful evolution for a country whose people tend to avoid talking openly about a recent violent past. In 1973 military and police forces overthrew the socialist government that had been elected barely three years earlier. What followed was “a wrenching tragedy,” in the words of a truth and reconciliation commission established after Chile’s return to democracy in 1990. In the first three months following the coup by Gen. Augusto Pinochet, more than 250,000 Chileans were arrested or detained. During the next 16 years, the total number of people killed, tortured, or imprisoned rose to 40,018.

Designing a new constitution would once again put General Pinochet’s legacy under scrutiny – not just his human rights abuses, but even more his economic policies. Chile’s transition back to democracy was managed under a constitution drafted by the military regime and designed to entrench market-oriented priorities that helped Chile achieve success on a continent not known for economic and political stability. Since 1980 Chile has gone from being the poorest country in Latin America to having the highest total economic output. It is a haven for foreign investment and notably free of corruption.

Chile has been one of the region’s most effective countries in addressing economic inequality. But perhaps because of such rising expectations, Chile has seen waves of mass protests that reflect a society convinced of the opposite. Demonstrations over the past year finally forced the government to call the referendum.

Public perceptions of inequality are not unfounded. Cities across the country, and particularly in the south, have seen a rapid expansion of tightly packed low-income neighborhoods. One Pinochet-era oddity in particular captures why ordinary Chileans feel aggrieved: All water resources are open to private ownership. As a result large national and international companies own exclusive rights to volumes of water flowing through the country’s many rivers, posing environmental threats and resulting in water emergencies in areas where 67% of the population is concentrated.

The Sunday referendum, delayed six months by the pandemic, has raised expectations that a new balance can be found between individual and collective prosperity. “There is a lot of hope surrounding the referendum,” writes Chilean activist María Jaraquemada. “Chile’s current constitution lacks legitimacy. The process to create a new constitution could enable a renewal of Chilean democracy and establish a new pact with the government in which citizens finally participate actively.”

If Chile can reinvent itself with a new constitution, it might help put an end to violent overthrows in a region still struggling to operate through consensus and equality.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Hold to the good

No matter what we may see or hear – either in our own experience or on the news – there is a truth we can all hold to that does more than make us feel better. It helps us detect and bring out the spiritual force of divine good that is able to effect change.

-

By Michelle Boccanfuso Nanouche

Hold to the good

Jeremiah Swift and Ryun King, tattoo artists in Murray, Kentucky, recently began offering a free body-art modification service to patrons who had hate-related tattoo slogans and symbols that no longer reflected who they were. Mr. King told CNN, “We just want to make sure everybody has a chance to change” (Alaa Elassar, “A Kentucky tattoo shop is offering to cover up hate and gang symbols for free,” cnn.com, June 14, 2020). Reports like these show the pure hearts of those willing to witness, encourage, and help others wake up to their true good selves.

When I was a young child, my mom – frequently overwhelmed with the responsibility of raising three teenagers and two preschoolers – was no stranger to profanity. I struggled to reconcile the sweet mothering I often witnessed with some of the harsh words that would escape from her mouth during the day. But I asked God to help me understand. And the simple answer that always brought peace was “Mommy is God’s child. Mommy is good.”

Seeing only what was good in my mom was so easy and natural. And it brought me that revelation of her true nature as good, as the reflection of God’s goodness. And I think that view of her helped heal the situation, because the cursing started to dramatically lessen. She became better known for her “whoopsie-daisies” than for anything off-color – a healing that lasted her lifetime.

Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy wrote of the potential for great moral and physical transformation through an understanding of God’s infinite good, and the reflection of that goodness in the heart of humanity. In her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” she explained, “The admission to one’s self that man is God’s own likeness sets man free to master the infinite idea” (p. 90).

Understanding the goodness that each of us reflects as the likeness of God sets us free to see through and heal undesirable character traits either in ourselves or others. Even more, it enables us to pray for the needs in the wider world with greater confidence.

The Monitor, in fulfilling its mission “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind” (Mary Baker Eddy, “The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 353), seeks out and highlights evidences of substantial good to be found in even the most difficult of human circumstances. And by bringing to light those difficult circumstances, this news organization is also pointing out to readers issues needing prayer. In particular, prayer that looks to the divine Mind that is God helps us detect and bring out the spiritual force of divine good that is able to effect change, when bad behavior, conflict, and vice seem to hold the reins.

In the last book of the Bible, Revelation, John writes about “a new heaven and a new earth” (21:1), indicating the great change that comes to light step by step as we recognize God’s goodness as supreme, overcoming and destroying all evil. Science and Health challenges us, “Have you ever pictured this heaven and earth, inhabited by beings under the control of supreme wisdom?” (p. 91).

We can see glimpses of the new heaven and new earth when we let the divine Mind show us what’s true about ourselves and others. We can see the reality of God’s goodness as the true motivator and governor of every individual. This prayer bears fruit on an individual level, but it is also bound to bring blessings on a larger scale, bringing out more of the truth of God’s good and pure creation.

A message of love

It’s a boy!

A look ahead

Thank you for spending time with the Monitor today. Please come back tomorrow when our Whitney Eulich looks at how Mexico is wrestling with the line between protest and disorder. Seeking progress against rape and femicide, protesters are pushing boundaries.

For a summary of some of today’s top headlines, remember to check our First Look page.