- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- White working class is shrinking. It still may decide 2020 election.

- Fleeing the Taliban in the night, a family’s faith in peace wavers

- Poll watching: Democratic safeguard or intimidation?

- Is Bolivia’s vote a comeback for Latin America’s left? Not so fast.

- Did prehistoric climate change help make us human?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Debates may not change voters’ minds. They’re still good for democracy.

Thursday’s final presidential debate probably won’t change many votes. President Donald Trump did not hurt himself, though his bar of expectations was low following a rough first debate in which he interrupted constantly. Challenger Joe Biden didn’t slip up, laid out prospective policies, and generally parried the president’s attacks.

In any case there aren’t many votes available to sway. Only about 5% of voters are undecided. With mail-in and early voting about one-third of estimated 2020 ballots – some 47 million – have already been cast.

But debates are still a useful exercise for American democracy.

For one thing debates juice turnout. Over 21 million people watched the debate live, and millions more saw clips and read media coverage. Debates are a clear, head-to-head competition. They can make partisans more excited to head to the polls for their side.

They’re also educational. On Thursday both challenger and incumbent told us who they would plan to be in the Oval Office. Mr. Biden talked like a conventional liberal Democratic nominee, who will try to solve major social problems with preestablished plans. President Trump was the President Trump of the last four years – a mix of bravado, false statements, and improvisation.

And in the end debates are democracy itself. They are rituals that bring together millions of people, who watch and talk about them and judge candidates and think about who the nation’s leaders should be.

“Being engaged in politics, making observations, sharing experiences with others, these are what democracy is about,” tweeted Jennifer Victor, a George Mason University political science professor, following Thursday’s event.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

White working class is shrinking. It still may decide 2020 election.

Working class voters from Rust Belt states were key to the 2016 election – and may yet decide 2020. Four years later, their concerns are the same: jobs and a future for their kids. But who do they feel best represents their values?

Nationally, white voters without college degrees are a shrinking portion of the electorate. Yet in critical battleground states like Pennsylvania, they still represent a majority of voters. Because President Donald Trump’s approval has dropped significantly in the suburbs, he likely needs to grow his support among this demographic.

In theory, he has room to do that. According to Dave Wasserman of the Cook Political Report, 66% of all eligible citizens who did not vote in Pennsylvania in 2016 were non-college-educated white adults. And over the past four years, Republicans have been outpacing Democrats among new voter registrations in the state.

But Democratic nominee Joe Biden is making a direct play for these voters as well. The former vice president has been careful to walk a more moderate line on issues like fracking, and has emphasized his own hardscrabble childhood in Scranton. That’s making the president’s path to victory more challenging.

“We value our values here, and that’s why we love Joe,” says Jimmy Connors, who was Scranton’s mayor from 1990 to 2002, serving as a Republican for all but two of those years.

White working class is shrinking. It still may decide 2020 election.

Almost every morning, half a dozen men meet for coffee at Max’s Deli, a diner that shares a wall with an auto supply shop, to talk politics. Some live “up the line” or “down the line” – a reference to the historic Scranton railway – but all have lived in the area their entire lives. And come Nov. 3, all are planning to vote for President Donald Trump.

“I’ve never really been political up until this last election,” says Bob Duffy, an Air Force veteran and retired mailman. He expresses some distaste for the president’s personal behavior, saying “I don’t care for his attitude.” But he still believes Mr. Trump is suited to the job: “He’s the type of man we need for this political age.”

“I’m all for him,” agrees Al Gordon, a veteran as well. “He’s finally standing up to China for a change, and standing up to all these countries that have been taking our money.”

Four years ago, voters like Mr. Duffy and Mr. Gordon propelled Mr. Trump to a surprise win here in Pennsylvania – and, by extension, the Electoral College. Mr. Trump’s success in formerly Democratic-leaning Rust Belt states, including Michigan and Wisconsin, sent media outlets scrambling to places like Max’s Deli outside Scranton to try to better understand why white working-class voters had so fervently embraced the brash real estate mogul from New York.

Now, as the nation hurtles toward one of the most contentious and unusual elections in modern history – in a year marked by a pandemic, mass unemployment, and social and racial turmoil – Mr. Trump’s hopes for a second term may hinge once again on the support of these same voters. The big question is whether they will back the president with equal or even greater levels of intensity this time around. And whether it will be enough.

Nationally, white voters without college degrees are a shrinking portion of the electorate, going from 45% in 2016 to 41% now. Yet in a number of critical battleground states like Pennsylvania, they still represent a majority of voters. Because the president has seen his approval drop significantly in the suburbs, he likely needs to grow his support among this demographic.

In theory, Mr. Trump has room to do that. According to Dave Wasserman of the Cook Political Report, 66% of all eligible citizens who did not vote in Pennsylvania in 2016 were non-college-educated white adults – more than the state’s Black, Hispanic, Asian, and college-educated white non-voters combined. And over the past four years, Republicans have been outpacing Democrats among new voter registrations in the state.

But Democratic nominee Joe Biden is making a direct play for these voters as well. The former vice president has been careful to walk a more moderate line on issues like fracking, and has emphasized his own hardscrabble childhood in Scranton. That’s making the president’s path to victory more challenging.

So far, “polls show Trump is winning a smaller percentage of non-college whites than he did in 2016,” notes Mr. Wasserman. “For every one of those voters who defect from Trump to Biden, Trump needs to bring out two [new] voters to offset that.”

Still, the fight for one of the nation’s largest swing states is not a done deal. After all, many point out, Mr. Trump was behind in Pennsylvania polls four years ago, and wound up winning.

“Trump can’t afford to lose anything here,” says Joseph Sabino Mistick, a law professor at DuQuesne University and Sunday columnist for the Pittsburgh Tribune. “But Biden’s always been a hero of the working class – and this creates a dilemma for Trump in Pennsylvania.”

The Keystone State

In mapping out various paths to 270 electoral votes, no state may be more critical to both candidates than Pennsylvania. To put it another way, it’s difficult to envision either candidate ultimately winning the Electoral College without it.

President Trump won Pennsylvania – the first Republican presidential candidate to do so in more than three decades – by fewer than 45,000 votes in 2016. Since then, he’s held more rallies here than in any other state aside from Florida, including one just this week in Erie.

Mr. Biden seems equally determined to win the Keystone State. In addition to playing up his connection to Scranton, he has based his campaign headquarters in Philadelphia, and has used Pittsburgh as the site for several nationally televised addresses. His former boss, President Barack Obama, chose Philadelphia as the site for his first “drive-in rally” in a return to the campaign trail this week.

In some ways, Pennsylvania’s politics can be seen as a microcosm for the United States as a whole. Cities densely populated with diverse, college-educated liberals seem a world away from the state’s rolling rural counties of mostly white, non-college-educated conservatives.

As elsewhere, the suburbs in between have dramatically shifted from red to blue in recent years. Pennsylvania’s suburban voters now favor Mr. Biden by 38 percentage points over Mr. Trump, according to a recent Washington Post-ABC News poll. That’s 25 points higher than Hillary Clinton’s margin four years ago.

Much of that shift has been driven by suburban women – whom the president has lately taken to pleading with directly. “Suburban women, will you please like me?” he joked at a rally last week in Johnstown. “Please. Please.”

Some political experts think Mr. Biden’s lead in the suburbs will be enough to hand him the presidency outright. Indeed, Mr. Biden currently leads in Pennsylvania overall by an average of 6 percentage points, according to FiveThirtyEight.

“People always talk about the white working-class vote. What about the women who shop at Trader Joe’s?” says Robert Lang, a professor of public policy at the University of Nevada Las Vegas and co-author of the book “Blue Metros, Red States.” “In 2016, there was complacency in suburban Philly – and now, voters there report to pollsters they would walk over glass to vote.”

Still, that assumes Mr. Trump doesn’t find a way to grow his support in small town and rural areas, either by expanding his 30-point 2016 margin of victory among Pennsylvania’s white working-class voters, or by drawing more of those voters to the polls this time around. He may need to do both.

Swing counties

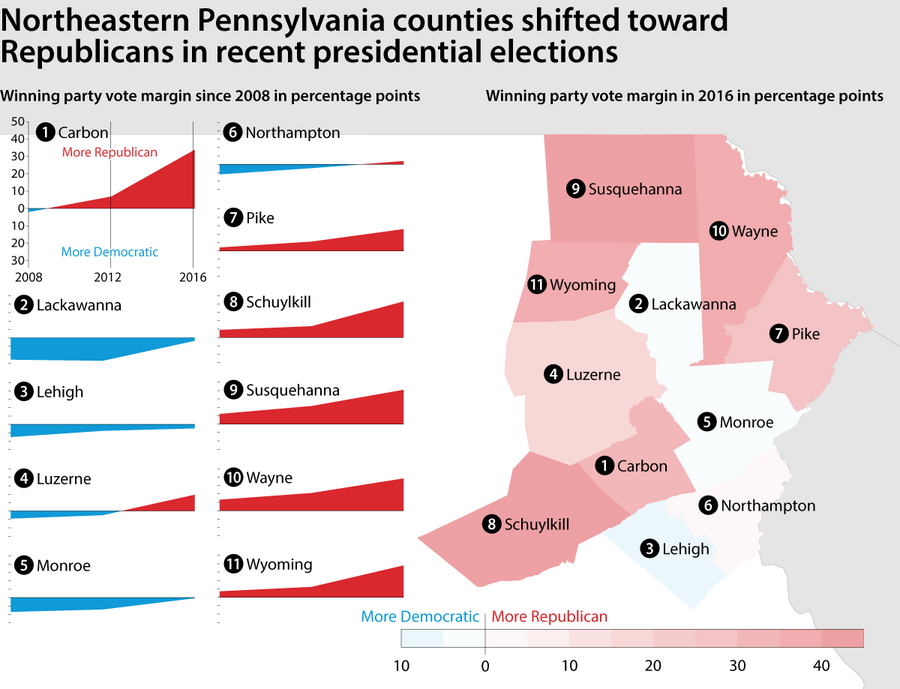

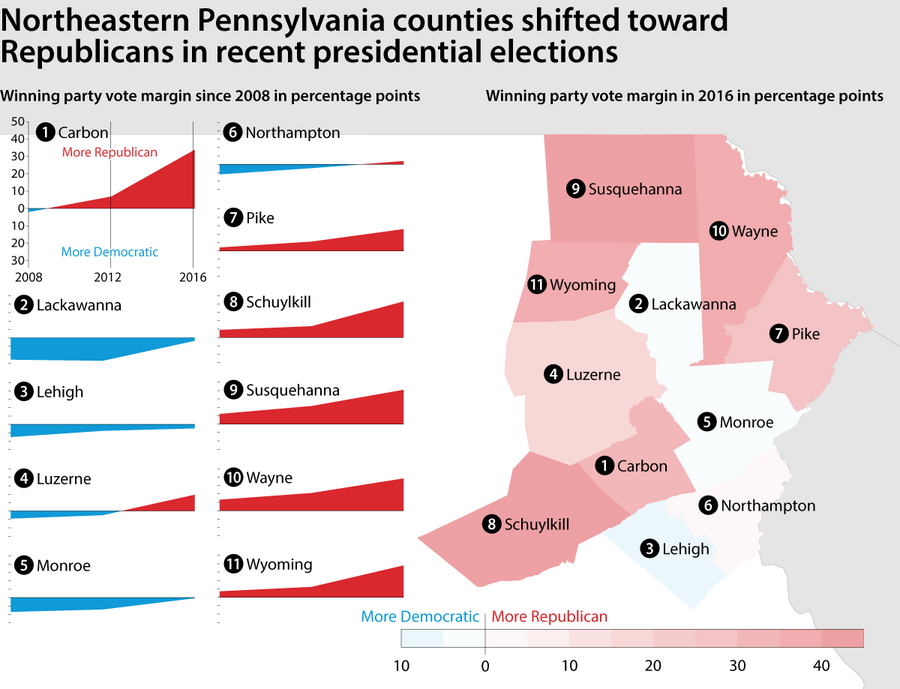

Pennsylvania’s key swing region is the right tip of the “T” between Scranton and Allentown, which is home to two of the state’s three “pivot counties” that twice voted for Mr. Obama before voting for Mr. Trump. Luzerne County swung from a nearly 9-point margin for Mr. Obama in 2008 to a 19-point victory for Mr. Trump. And while neighboring Lackawanna County, home to Scranton, stayed blue, the margin was alarming for Democrats. After Mr. Obama’s more than 27-point win in 2012, Mr. Trump lost here by fewer than 4 percentage points.

“The people here are very frustrated with the lack of progress that we’ve seen in the past 40, 50 years,” says Gary Wegman, a Democrat running in the 9th Congressional district. “They want to see their communities be able to compete like the rest of the world. They’re tired of being on an uneven playing field.”

When asked to describe themselves, northeastern Pennsylvanians offer adjectives like: hardworking, friendly, working class, and honest. The area was once defined by its anthracite coal mines, and the immigrant populations who came here to work in them. But the number of mining jobs have decreased, as have manufacturing jobs. Now it’s hard to even make a profit farming, says Dr. Wegman, who is both a fifth-generation farmer and a dentist.

Before COVID-19 disrupted the national economy, Pennsylvania had an unemployment rate of 12%, higher than the country as a whole. And counties in the northeast region – Lackawanna, Luzerne, Susquehanna – had rates higher than the state average. This year, following the pandemic, the statewide unemployment rate set a four-decade record.

“I just decided years ago that my two kids aren’t going to have the same opportunities that I did. It just gets chipped away more and more each year,” says John Kameen, chair of the Susquehanna County Committee to Re-elect President Trump. This economic frustration, he says, has gradually pushed the area’s residents away from the Democratic Party.

Between 2012 and 2016, Republican voter registration increased by more than 7% in Lackawanna County, more than 14% in Luzerne County, and more than 5% in Susquehanna County. Between 2016 and this month, these three counties have witnessed similar increases. Meanwhile, Democratic registration in these counties has decreased since 2012.

New York Times polling data

Mr. Kameen, who has been involved in Susquehanna County politics for over 50 years, says local enthusiasm for Mr. Trump in 2016 was unlike anything he had ever seen. And he insists this year is surpassing it. At the local GOP headquarters, he says they routinely run out of Trump-Pence lawn signs – and have sold at least 20 4-by-8-foot ones. “A guy came yesterday and said he wanted five,” he says.

Dr. Wegman, the Democratic congressional candidate, says he wasn’t surprised that Mr. Trump did well in northeast Pennsylvania in 2016 – because he spoke directly to voters’ concerns.

“I saw what [they] were listening to, and I understood,” he says. He knows plenty of people who want to work but can’t find jobs. He agrees that the immigration system needs reform.

And while he thinks Mr. Biden is the candidate who would best deliver on all these issues, he hopes the former VP can convince enough of his northeastern Pennsylvania neighbors of that.

“You want to win Pennsylvania, you’ve got to come in here to the ‘T,’” says Dr. Wegman. “[Biden’s] going to win Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. But are there enough votes there? Ask Hillary.”

“We value our values here”

At the Lackawanna County Democratic headquarters in Peckville, five women sit around plastic folding tables, sharing pizza and soda. They all have friends who voted for Mr. Trump – either because they hoped he would bring back jobs, or because he wasn’t Mrs. Clinton. But they say it’s now clear that the president has only made things worse.

“I think the working-class people who thought they were going to get a change with him are going to be looking at it now and saying, ‘No, I’m not any better,’” says Ann McDonough, a retired teacher who was born and raised in Scranton. “I think people got fooled by him. I know I paid more taxes.”

Ms. McDonough volunteers at the Peckville office on weekday afternoons – a level of political involvement she says she’s never had before. She periodically interrupts herself to welcome locals who wander in, handing out signs for Democratic candidates up and down the ballot.

She and the other women speak of a widespread fatigue in the area.

“People are tired,” says Mary Ann Kapacs, former chair of the Lackawanna County Federation of Democratic Women. “I’ve stopped watching the news because it’s just too upsetting. And combined with the quarantine and everything,” she trails off. “It just makes you feel bad inside.”

Mr. Trump’s personal behavior goes against the values they were taught as children growing up here, the women say – which is one reason Mr. Biden’s early years in Scranton mean something to them.

“We value our values here, and that’s why we love Joe,” says Jimmy Connors, who was Scranton’s mayor from 1990 to 2002, serving as a Republican for all but two of those years.

When asked why he thinks Mr. Biden would be a good president, Mr. Connors at first references policy positions. But he also mentions Mr. Biden’s Amtrak commute from Washington to Delaware each evening back when he was in the Senate so he could be with his family.

“Can you see Trump doing that? That’s the difference between [Trump] and what Biden learned at his kitchen table here in Scranton,” says Mr. Connors. “Biden is Scranton.”

New York Times polling data

Fleeing the Taliban in the night, a family’s faith in peace wavers

The Taliban practice of “fighting while talking” has long raised questions about their commitment to peace in Afghanistan. Now, as more die and thousands flee, the U.S. is calling the tactic “very risky.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Afghanistan’s southwestern Helmand province – long a Taliban target prized for its illicit opium production – has witnessed some of the most sustained fighting in the war. The fighting hasn’t abated, even amid long-sought peace talks between the Taliban and government in Kabul.

A recent Taliban offensive to capture Lashkar Gah, the provincial capital – the boldest among a multitude of lethal Taliban attacks and advances nationwide in recent weeks – created nearly 40,000 displaced Afghans and required American airstrikes to stop it. It precipitated a warning from the U.S. peace envoy, Zalmay Khalilzad, that “too many Afghans are dying,” and that the Taliban tactic could “undermine the peace process.”

“This recent attack, especially, has sent a gloomy feeling across Afghanistan that” the Taliban “feel that they can still settle this by war, rather than at the negotiating table,” says a veteran Kabul analyst.

“We are surprised by our situation,” says an Afghan corn farmer whose family was forced to flee the Taliban advance. “We were too optimistic. All our nation was very happy. We thought, ‘We will have a peaceful life, there will be no conflict, our people will not kill each other,’” he says. “Unfortunately ... our people are still killing each other.”

Fleeing the Taliban in the night, a family’s faith in peace wavers

Afghan corn farmer Ehsanullah Popalzai dared to hope that peace might be possible when he saw Taliban insurgents and Afghan government negotiators finally sit down face-to-face for the first time last month to end decades of war.

He expected a cease-fire, or at least calm, while talks progressed in Doha, Qatar.

But instead, as darkness fell one night last week, Mr. Popalzai and his family experienced once again the pain of war and fled their home, caught in the path of a Taliban offensive to capture Lashkar Gah, the capital of southwestern Helmand province.

That single offensive – the boldest among a multitude of lethal Taliban attacks and advances nationwide in recent weeks, as the insurgents keep pressure on Afghan security forces despite the peace talks – created nearly 40,000 displaced Afghans and required American airstrikes to stop it.

It has also raised broader questions about whether the Taliban prefer waging war over making peace, and therefore the fragility of Afghans’ own hopes to end 40 years of conflict.

“We are surprised by our situation,” says Mr. Popalzai, noting how hope over the Doha talks has turned to despair for his family.

“We were too optimistic. All our nation was very happy. We thought, ‘We will have a peaceful life, there will be no conflict, our people will not kill each other,’” says Mr. Popalzai, contacted by phone. “Unfortunately, that belief was not true, our people are still killing each other.”

A flight in the dark

On the morning of the battle, Taliban fighters had infiltrated fields and villages in Mr. Popalzai’s district east of Lashkar Gah. The fighters gave prayers – even calling from the loudspeakers of the local mosque for divine help in delivering victory, which Mr. Popalzai says he heard – and then surrounded a nearby military outpost, attacked, and in a two-hour battle “killed most of the soldiers,” before burning the base.

Surviving troops took up defensive positions along the road, and also broke through the high wall of Mr. Popalzai’s family compound with their armored vehicles – despite family protests that it was full of women and children. After dark, the Taliban attacked again, prompting an immediate exodus of the family and a night of heavy American airstrikes.

“Too many families left the area at the same time; we suffered too many problems ... and don’t know about our future,” says Mr. Popalzai. What “damaged my soul,” he says, was losing track of his 8-year-old daughter for a day and a half, until she was found with another family.

The Afghan farmer is angry that war has once again upended his life, while the intra-Afghan talks stall over procedural issues. He is angry that his entire family of 16 must now shelter in an empty, one-room shop in town.

And he is angry that it finally required American airstrikes – the first of consequence since the United States and Taliban signed a withdrawal deal last February – to stop the Taliban advance.

“This recent attack, especially, has sent a gloomy feeling across Afghanistan that probably peace will not be as easy as we dreamed,” says a veteran Kabul analyst from an organization that facilitates peace efforts, who asked not to be named.

“The image that has gone [out] to the Afghan population is that, given the Taliban are in the stronger position, they feel that they can still settle this by war, rather than at the negotiating table,” says the analyst. “For the Taliban, to show militarily they remain quite a formidable force is one of the key tools in their hand to demonstrate why making peace with them is necessary.”

But the Taliban strategy of fighting while also talking peace is wearing thin, especially due to the disruption of civilian lives by, for example, cutting off the road between Lashkar Gah and Kandahar to the east, on the long road to Kabul.

“It’s proving counterproductive [for the Taliban],” says the analyst. “Roads cut off mean difficulty for commuters, difficulty for businesses. Hospitals are full. So I definitely think this is not great PR for the Taliban.”

The U.S.-Taliban deal signed Feb. 29 commits to a full troop withdrawal of the remaining U.S. troops, who number at least 4,500, and 6,100 other NATO soldiers by May 2021 – which would end America’s longest war after 19 1/2 years. But it is conditional on counterterrorism guarantees from the Taliban, and a reduction in violence that the U.S. says was meant to be “as much as 80%.”

Since February the Taliban have halted attacks against U.S. and other NATO troops, in line with the deal. But they have barely eased attacks against Afghan security forces.

“Too many Afghans are dying”

U.S. special envoy Zalmay Khalilzad and the top U.S. commander in Afghanistan, Gen. Scott Miller, met the Taliban several times last week and agreed on a “reset” to reduce attacks.

“At present too many Afghans are dying,” Ambassador Khalilzad tweeted Oct. 15. The Taliban tactic of fighting while talking is “very risky,” he later warned, because it can “undermine the peace process and repeats past miscalculations by Afghan leaders.”

“We are blaming the Taliban because there is no reason for conflict and violence,” says Mr. Popalzai, whose Helmand province – long a Taliban target prized for its illicit opium production – has witnessed some of the most sustained fighting in the war.

“Before, the Taliban said there is jihad against Americans, but now America is leaving the country and most of them have already left, so there is no reason for violence,” says the farmer. “[Now] it is only Muslims and Afghans killing each other.”

Indeed, the U.S.-Taliban deal changed the pattern of conflict in favor of the insurgents, such that “the Taliban have little incentive to reduce violence,” according to an in-depth report last week by Andrew Quilty for the Kabul-based Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN).

“With the threat of being targeted by government or U.S. forces now low, morale among [Taliban] fighters has soared” due to “the prospect of ultimate victory – whether by political or military means,” notes the report, based on dozens of interviews across three provinces.

In contrast, Afghan security forces spoke of frustration over the government’s “sudden passivity” toward the Taliban. “The current defensive posture” makes them “vulnerable to attack, has meant a rise in casualty rates and depressed morale,” AAN concludes. “This is not sustainable.”

Even as the U.S. draws down its troops, it is trying to “prevent any negative outcomes” that lead to civil war in Afghanistan “or even less stability than it has now,” General Miller told the BBC this week.

Humanitarian crisis

That may not be easy, says a lawyer in Lashkar Gah who works for Afghanistan’s intelligence service, the National Directorate of Security, and asked not to be named.

The latest attack on his city is further proof, the Afghan lawyer says, that peace talks are a “waste of time, because the Taliban want to play for time,” until U.S. and coalition forces withdraw, so they can “focus on fighting.”

Yet the Taliban attacks’ biggest impact is on the ground, where a new humanitarian crisis has grown, beyond the tide of displaced civilians.

The medical charity Emergency said Lashkar Gah’s main surgical center, which it operates, was “saturated” with 132 war-wounded.

The gap between “the raised hopes” of the Doha peace talks and the “harrowing daily reality of those who have seen their lives destroyed by fighting is abysmal,” the charity said.

At the Boost provincial hospital, which takes overflow cases and is supported by the French charity Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), 52 war-wounded patients arrived in the first days of the fight, “all with stories as devastating as their injuries,” wrote hospital coordinator Marianna Cortesi on the MSF website.

In one case, a pregnant woman called Safia – just two months before her due date – was struck with a stray bullet that killed her unborn child. Another woman, Zina, was breastfeeding when a stray bullet hit her in the chest, narrowly missing her 8-month-old baby.

Such casualties are no surprise to Mr. Popalzai, the corn farmer. His family also fled a similar Taliban attack in 2016, but not before the Taliban targeted his house with a shoulder-fired rocket. The explosion killed his younger brother and sister.

“The first clause for ending the war in Afghanistan is a long-term cease-fire,” he says. “For this, America should bring pressure on both sides to tolerate each other.”

Hidayatullah Noorzai contributed reporting for this story from Kabul, Afghanistan.

Poll watching: Democratic safeguard or intimidation?

As the president urges his supporters to go en masse to watch polling, Americans of all political stripes are grappling with trust in the election process. Understanding the protections in place, like the tradition of poll watching, can help restore confidence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

As President Donald Trump calls the integrity of the election into question – asking his supporters to “go into the polls and watch very carefully” – he stokes fear of widespread voter fraud and intimidation at the polls, say election experts.

This raises the question of trust in the elections, the fairness of which is fundamental to the democratic process. But election experts say voters should have confidence in the system, which has strong protections in place and in which voting irregularities are rare.

“Voters should not be afraid to exercise that fundamental right to vote at polling places,” says Eliza Sweren-Becker, voting rights and elections counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice. “The best way to push back … is to show up robustly at the polls, and for voters to have their voices heard.”

The role of poll watchers is getting heightened scrutiny. Known as partisan observers, they are distinct from the poll workers who run elections in the country’s roughly 170,000 precincts. They’re an institution within the American electoral system meant to support transparency and fairness by reporting concerns at polling places or during ballot counting.

Poll watching: Democratic safeguard or intimidation?

On Election Day 2016, Jane Grimes Meneely arrived at a Nashville, Tennessee, community center ready to put her three-hour poll watcher training to use. Sent by the Clinton campaign, she wore a badge around her neck and a bright blue “ELECTION PROTECTION” sticker on her back.

Her job: Report concerns, but don’t interact directly with voters.

Over her six-plus-hour shift, however, Ms. Meneely says she never had to use her authority because the day “went really smoothly.”

“There was a part of me that wanted to use the training ... but also thankful that I didn’t have to,” she says.

Designated poll watchers like Ms. Meneely are a traditional part of the American election system.

But the role of poll watching is getting heightened scrutiny since President Donald Trump, at the September presidential debate, urged supporters to “go into the polls and watch very carefully.”

That call, paired with the president’s persistent, unsubstantiated claims of widespread voter fraud, raises the question of trust in the elections, the fairness of which is fundamental to the democratic process. Voting rights advocates and Democrats see it as potential encouragement of interference, even intimidation, at the polls.

Though the president may question the integrity of the election, citizens should not be dissuaded from voting by mistrust or intimidation, say election experts. To help bolster confidence, they stress the importance of understanding protections in place that restrict who can interact with voters – and how.

“Voters should not be afraid to exercise that fundamental right to vote at polling places,” says Eliza Sweren-Becker, voting rights and elections counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice.

Voter intimidation is rare

Laws that govern the American election process are hard to generalize, because the Constitution grants states broad authority to run elections on their own terms. Rules also vary between counties.

Attempts to “intimidate, threaten, or coerce” voters, however, is a federal crime, and states have similar statutes that safeguard ballot casting. Given the decentralized nature of U.S. elections, it’s hard to determine the extent of voter intimidation at the polls. The American Civil Liberties Union calls it “rare and unlikely.”

Poll watchers – also known as election or political observers – are meant to support transparency and fairness. They generally can report concerns at polling places or during ballot counting. Poll watchers are distinct from the poll workers who run elections in the country’s roughly 170,000 precincts.

Prototypes of modern-day poll watchers were the “party agents” who emerged around the 1830s, says Richard Bensel, professor of government at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Before the adoption of the secret ballot in the 1890s, party agents could publicly challenge voter eligibility, often without hard proof.

The role of today’s poll watchers is limited. Typically they are appointed in advance of an election by a candidate or political party and can be restricted in number per polling place. Battleground state Wisconsin is an exception, where anyone except for candidates themselves can observe within designated areas, though further local restrictions may apply. Statutes in some states including Georgia, North Dakota, and South Carolina require poll watchers to wear a badge bearing their name and organization.

“They are really only there to observe, so they can’t talk to or interact with voters. They’re not supposed to interfere with the [voting] process at all,” says Ms. Sweren-Becker.

Similar calls by Mr. Trump to monitor polls en masse were issued in the 2016 elections, but they have been eclipsed by cybersecurity concerns and foreign interference, says Tammy Patrick, senior adviser for the elections program at Democracy Fund and former election official for Maricopa County, Arizona.

“Thankfully, we haven’t seen [intimidation at the polls] manifest in a widespread way,” she says, adding that it has been on the radar for election officials long before Mr. Trump came onto the scene. As far back as 1999, when the Columbine High School shooting massacre in Colorado shook the nation, election officials have braced for trouble by preparing contingency plans.

Political observers are typically trained by the entity that appoints them. Ms. Meneely, in Nashville, was trained through the Clinton campaign, for example. Training can involve a review of proper behavior and how to report concerns, such as illegal voting, tampering with equipment, or other perceived interference. Maricopa County’s curriculum prepared by Ms. Patrick includes reminders to observe officials’ instructions and stay six feet from ballot boxes or voting booths.

“Ballot security”

The Trump campaign says it expects to exceed its goal of 50,000 trained poll watchers in this election, but did not respond to a Monitor query about whether that goal has been met. Echoing his father’s expectations of massive fraud by the “radical left,” Donald Trump Jr., in a campaign video last month, implored “every able-bodied man [and] woman to join Army for Trump’s election security operation,” including during early voting, by signing up online.

Officials including the FBI director have dismissed the notion of widespread voter fraud historically in a major election. The conservative Heritage Foundation has tracked 1,298 proven cases of voter fraud in thousands of elections nationwide since 1982.

“In a sense, these calls could be heard as proverbial dog whistles for signaling [Trump’s] supporters to intimidate Blacks and Latinos in particular,” says Atiba Ellis, professor of law at Marquette University Law School. He considers the president’s talk akin to Jim Crow-era intimidation of voters of color, who gained heightened protection with the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Trump campaign says it is committed to “every voter’s right to vote.”

“President Trump’s volunteer poll watchers will be trained to ensure all rules are applied equally, all valid ballots are counted, and all Democrat rule breaking is called out,” wrote deputy national press secretary Thea McDonald in an email to the Monitor.

This presidential election marks the first in four decades that the GOP hasn’t needed court approval to carry out what it deems “ballot security” activities. During a tight race for New Jersey governor in 1981, the Republican National Committee helped assemble a National Ballot Security Task Force of armed, off-duty law enforcement officers to patrol polling sites in minority communities. The Democratic National Committee sued the GOP, alleging voter intimidation. In a settlement, the Republicans entered into a consent decree that expired in 2017.

The Democratic National Committee did not clarify how many poll watchers have been trained this year as part of its national “election protection” initiative in response to a Monitor request. An official did note in an email that the DNC’s “historic investments” include 28 state voter protection directors and filing litigation to expand access to voting.

Due diligence

The scope of Pennsylvania poll watchers’ access was tested in Philadelphia this month. A judge denied the Trump campaign’s request to allow poll watchers at the city’s new voter registration and ballot drop-off offices because they are not polling places.

New election infrastructure has been introduced in many precincts, especially as mail-in voting has expanded during the pandemic. Some states that ran vote-by-mail elections prior to the outbreak haven’t permitted poll watchers at ballot drop boxes.

Election roles differ in title and authority depending on jurisdiction. Michigan, for example, allows for challengers to raise questions about a voter’s eligibility. Blurring definitions further, some people use the term poll watchers to describe individuals who engage in unofficial monitoring outside polling places.

International and other nonpartisan observers can engage in election protection with varying levels of access to the voting process. Electioneering typically takes place beyond a buffer around a polling place, beyond which individuals can engage in political speech; but prohibitions on voter intimidation still apply.

To guard against disinformation or misinformation about the election, especially on social media, U.S. Election Assistance Commission Chairman Ben Hovland says voters should seek information directly from state or local election officials.

Questions about casting your ballot? Contact your local board of elections, or visit www.usvotefoundation.org, for guidelines specific to where you live.

Is Bolivia’s vote a comeback for Latin America’s left? Not so fast.

Right- and left-wing parties have closely watched Bolivia this year, ever since a disputed election sent longtime President Evo Morales into exile. But does socialists’ win at the polls this week foretell a resurgence of the “pink tide”?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

One year ago, Bolivia’s election ended in chaos: weeks of protest; incumbent President Evo Morales fleeing the country; and a right-wing interim government stepping in, which twice postponed redo elections.

When the long-awaited vote was held this week, observers across Latin America viewed it as more than a referendum on Mr. Morales’ socialist leadership. It was a wider test: Could Latin America’s political left – the so-called pink tide – make a comeback?

The socialist party candidate, Luis Alberto Arce Catacora, won at the polls. But that’s not a harbinger for the region, analysts say. Instead, the biggest takeaway for Bolivia’s neighbors is the rejection of incumbents in a region where faith in democracy is on the decline, and economic security is in a tailspin, says Christina Ewig, an expert on Latin American politics.

The conservative interim government made a series of missteps, which combined with the unprecedented toll of COVID-19 to lay the groundwork for socialists’ return, says economist Gonzalo Chávez Alvarez.

“Bolivia chose to resolve its problems through democracy,” Dr. Chávez says. But, he adds, “right or left, we are seeing a resistance to playing by the rules of the game” across Latin America, whether Morales in 2019, or Venezuela, Brazil, or Nicaragua today.

Is Bolivia’s vote a comeback for Latin America’s left? Not so fast.

“¡GAME OVER!” tweeted Venezuela’s foreign minister.

A “retreat to the left,” suggested one international headline.

A “blow to neoliberalism,” a foreign activist proclaimed.

For many, Bolivia’s long-awaited presidential election this week was not only a referendum on exiled former President Evo Morales’ 13-year term, but a test for the possible rebound of Latin America’s political left.

The socialist party candidate Luis Alberto Arce Catacora earned 54.5% of the vote with roughly 95% of votes counted by Thursday morning. It’s a rare win for the left in a region that took a sharp right turn in recent years, following more than a decade of the so-called pink tide of leftist leadership, from Brazil to Argentina, Chile to Uruguay. And it’s a striking comeback for Bolivia’s Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party, after allegations of fraud in the 2019 vote threw the country into months of civil unrest. But it’s not, experts warn, a harbinger for the reemergence of the Latin American left.

The results reflect unique aspects of Bolivia’s socio-economic situation, an Indigenous majority with a strong history of social mobilization, unhappiness with the conservative interim president, the socialist party’s move away from personality politics, and the opposition’s inability to coalesce behind a single candidate.

The biggest takeaway for Bolivia’s neighbors isn’t a return of the left, but the rejection of incumbents in a region where faith in democracy is on the decline and economic security is in a tailspin, says Christina Ewig, a professor at the University of Minnesota who studies Latin American politics.

“In terms of the regional context, this doesn’t signal more votes for the left, but more votes for change,” she says. “What we’ll see more of are problems for incumbents in Latin America, especially in 2021.”

Turbulent year

Evo Morales became Bolivia’s first Indigenous president when he took office in 2006. Over the course of his three terms in office, he promised to fight inequality, tighten state control over natural resources, and distance Bolivia from imperialist powers like the United States. Mr. Arce served in his administration for more than a decade, implementing fiscal policies that don’t typically jibe with leftist governments.

But the widespread support Mr. Morales enjoyed from his base started to erode as he began consolidating power and pushed for a second, third, and finally a fourth term in office. Before the fourth campaign, voters had narrowly rejected a constitutional amendment to let him run again. Yet the Supreme Court scrapped term limits altogether in 2018, ruling it was Mr. Morales’ human right to run – putting off many of his former supporters. He claimed victory in last year’s polls, but international observers questioned the results, and protesters took to the streets. The sometimes violent protests lasted nearly a month.

Mr. Morales fled Bolivia, while a U.S.-backed, right-wing interim government took the helm. When interim President Jeanine Áñez was sworn in, she made a show of bringing Christianity with her, after the last administration’s emphasis on Indigenous traditions. “The Bible has returned to the government palace!” she declared, carrying an oversized Bible.

A series of missteps, combined with the unprecedented economic and health tolls of COVID-19, laid the groundwork for a return to MAS leadership, says Gonzalo Chávez Alvarez, an economist who directs the master’s in development program at the Catholic University of Bolivia.

“This vote isn’t saying everything Morales did before was wonderful,” Dr. Chávez says. “It was a vote for social and economic change.”

Over the past year, the transitional government, which postponed the vote twice, “made many errors that scared voters,” Dr. Chávez says, including corruption, a lack of coordinated leadership, violent crackdowns on Indigenous communities and protesters, and the “terrible idea of the interim president presenting herself as a candidate for reelection,” even though she later took herself out of the running.

“Bolivians had a taste of what the right would be like and they really blew it under Áñez,” Dr. Ewig says. “She wasn’t prepared to be president. It was a year of right-wing rule that was disastrous and reminded people how much elites in Bolivia can be really exclusionary to the majority of the population, which is Indigenous.”

Former President Carlos Mesa, who also ran, “was painted with the same brush.”

The opposition had a hard time deciding whom to back, much like Venezuela’s opposition, which for nearly two decades failed to unite to contest increasingly authoritarian leftist leaders. The closest contender in Bolivia’s vote, the centrist Mr. Mesa, led the country during a tough economic crisis, conjuring up unhappy memories. President-elect Arce, by contrast, was finance minister at the height of the region’s commodity boom.

“We have recovered democracy,” Mr. Arce said in a speech early Monday, when early results signaled his victory. “We are going to govern for all Bolivians and construct a government of national unity.” He said Mr. Morales is welcome to return home, but he needs to answer to the justice system for the numerous charges lodged against him.

Over the past year, MAS and President-elect Arce were able to move themselves away from Mr. Morales’ powerful personality and become a more institutionalized party. And his emphasis on unity has given international observers hope.

“MAS has been an incredible force in Bolivian politics, and for it to become more institutionalized as a party rather than a personal vehicle for Evo Morales is really important for the long-term health of democracy,” says Dr. Ewig.

Questions ahead

Many of the international lessons from Sunday’s vote may be yet to emerge, depending on how Mr. Arce moves forward. Will he truly distance himself from his predecessor, as was the case in Ecuador after Rafael Correa, observers ask? Or will he follow the path of Venezuela, where Nicolás Maduro leans heavily on predecessor Hugo Chávez’s name and legacy?

Bolivia is in economic crisis, Dr. Chávez says, and whether Mr. Arce tries to create a new path or falls back on policies from the Morales days will have a big impact on what comes next. “This wasn’t just the interim government mismanaging the economy, this began back in 2014,” he says of Bolivia’s economic downturn. The GDP is forecast to shrink nearly 8% this year.

The global consequences of COVID-19 are hitting Latin America particularly hard, pummeling already fragile economies, increasing inequality, and feeding preexisting feelings that the promises of democracy haven’t delivered. With general and midterm elections taking place across the region later this year and in 2021 – from Argentina to Mexico to Venezuela – regional governments and citizens may hold up Bolivia as an example for peaceful change.

“Bolivia chose to resolve its problems through democracy,” Dr. Chávez says. “That’s a win for democracy. It proves turmoil can be resolved with the vote,” he says.

“But, right or left, we are seeing a resistance to playing by the rules of the game” across Latin America, he says, whether Morales in 2019 or Venezuela, Brazil, or Nicaragua today.

“It’s democracy that saved Bolivia’s socialist movement.”

Did prehistoric climate change help make us human?

News of climate change sparks concern, but it also brings out humanity’s most prominent trait: the ability to innovate. One recent study suggests that this was as true in our distant past as it is today.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Piecing together early human history is often like assembling multiple puzzles without all the pieces in the boxes. Researchers do their best to imagine the whole picture from some fragmentary fossils, artifacts, and what environmental data they can gather from the geologic record. But big questions remain about the origins of our species.

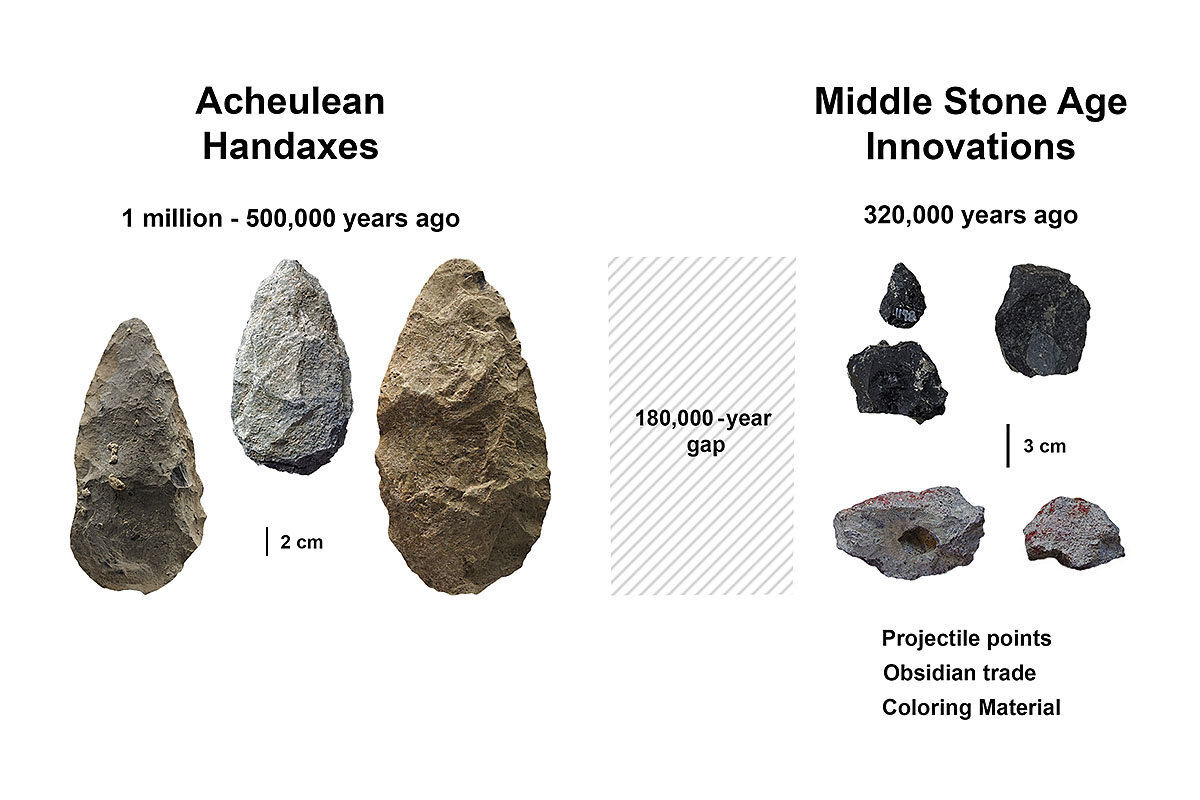

One of these arose in southern Kenya, when researchers found that a crucial 180,000 years was missing from the archaeological record at that site. Over that time, stone tool technology leaped from hand axes to a suite of more advanced technologies.

To better understand that transition, the team turned to the environmental puzzle pieces. Their results, detailed in a paper published in the journal Science Advances on Wednesday, reveal a particularly turbulent period, with rapid changes throughout the environment. And this could yield clues to some of the broader questions about the origins of our species.

“We’re really looking at the foundation of how humans adjust to environmental disruption,” says Rick Potts, study lead author and director of the Human Origins Program at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Did prehistoric climate change help make us human?

For years, Rick Potts has excavated ancient stone tools in southern Kenya, at a site called Olorgesailie, seeking to piece together a picture of what life was like for early humans who lived there. But he and his colleagues were puzzled by what seemed to be a technological leap forward.

Dr. Potts, the director of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Human Origins Program, said that the site yielded hundreds of thousands of years’ worth of stone hand axes, suggesting its residents were prolific toolmakers. But those tools seemed to disappear 500,000 years ago, and the next 180,000 years of the archeological record were missing, swept away by erosion.

The next tools show up in sediments that are some 320,000 years old, and those tools seem to indicate a cultural leap, one that could add to the story of the origins of our species.

But what prompted this leap? With no clear transition in the archaeological record at Olorgesailie the research team was left puzzled.

Dr. Potts and his colleagues found a spot about 15 miles away in the nearby Koora basin where they could extract a core of sediments from deep in the ground to assemble a timeline of the environmental conditions for the last million years.

“And it turns out that the missing time, that 180,000 year gap, is beautifully recorded in the core – thank goodness,” says Dr. Potts.

As the core revealed, a lot happened in those 180,000 years. Beginning about 400,000 years ago tectonic activity fractured East Africa’s landscape into small basins, the landscape alternated between arid grasslands and fertile woodlands. Large herbivores died out, replaced by smaller mammals with diverse diets.

And human behavior changed, too, says Dr. Potts, connecting the technological transition to the ecological context. ”We’re really looking at the foundation of how humans adjust to environmental disruption,” he says. And, according to a paper published by Dr. Potts and the research team on Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, that rapid climate change might explain what drove those early humans to innovate.

Emerging humanity

Piecing together early human history is often like assembling multiple puzzles without all the pieces in the boxes. Researchers do their best to imagine the whole picture from some fragmentary fossils, artifacts, and what environmental data they can gather from the geologic record. But big questions remain.

One of these is how the world went from having several human species – members of the genus Homo – to just one, Homo sapiens. Why did our species survive when others did not?

While this new study does not point directly to the origin of our species (the oldest fossil found with H. sapiens features has been dated to around 315,000 years ago), it might still provide some pieces of the puzzle.

The artifacts unearthed at Olorgesailie from around 320,000 years ago are markedly different from the earlier artifacts in a way thought to be emblematic of the technology and culture of more modern humans.

First, while the ancient stone hand axes were large and fairly uniform in shape, likely used for multiple purposes, the newer tools were smaller and more diverse. Some appeared to be projectile points. Others, blades or flake tools.

What’s more, while the older tools were made from stones that could be found nearby, some of the newer ones were made of rocks like obsidian that had to have been imported. This, the researchers posit, suggests that the humans at Olorgesailie had begun to engage in long-distance trade with other groups.

And that’s not all. There’s also evidence that the Olorgesailie residents were using pigments, which anthropologists often take as a sign of symbolic communication.

“All of that contributes to this strong impression that they are using their landscape and the resources available in it in a much more sensitive way, they’re not doing the same thing all the time,” says Julia Lee-Thorp, emeritus professor of archaeological science at the University of Oxford. “It is a feature of humans that they were using material culture to exploit the resources that were available to them.”

Lessons for the future?

But does that mean this new paper is providing pieces that fit in the puzzle of the origin of our species, H. sapiens?

Perhaps. This turbulent, rapidly changing environment was likely “the crucible from which modern humans sprang,” says Professor Lee-Thorp, and it’s certainly a driver of human evolution.

Still, cautions Pamela Willoughby, chair of the department of anthropology at the University of Alberta, there are instances in the archaeological record where technology seems to leap forward for a bit of time but then return to older styles of tools, or doesn’t change across the landscape as it does in a single site.

“I think this is a fascinating case study,” she says. “It involves lines of evidence from just about every source that you can get” with a massive, interdisciplinary research team behind it. But it remains to be seen whether these patterns appear across Africa at that time, Dr. Willoughby says.

However, most researchers agree that there’s something about the ability to be flexible in the face of change that seems to set H. sapiens apart.

“This is kind of defining in ancient times how our species adapts, how it adjusts to times of environmental disruption, or the shift from more stable, reliable times, to times of uncertainty,” Dr. Potts says.

And, as we enter another period of global climate instability, these findings may inform humanity’s response.

“The question is, does this work in the face of nation-states?” Dr. Potts asks. “Does it work in the face of big institutions? Does it work in the face of all of those things that have developed in civilization during a period of thousands of years of relative stability in our ecosystems and environment, which are now becoming disrupted?”

With so many more humans living across the entire world in a truly globalized society, Professor Lee-Thorp says, “It’s a very different situation” today than it was in ancient times. “But one would have to hope that human ingenuity would be able to get its head around it, and do something about it. Otherwise we’re in deep doo-doo.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Report card on gender equality in peacemaking

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Twenty years ago this month the U.N. Security Council urged countries to involve more women in preventing conflict and building peace. Resolution 1325 was hailed as a landmark. It was based on a recognition that women are disproportionately affected by armed conflict and that women in roles from foot soldier to negotiator are critical in preventing it.

Progress toward that goal has been slow. Yet the idea has taken hold as shown in debates this month at the United Nations. In an open letter, 558 civil society organizations from 102 countries wrote that the architects of Resolution 1325 created history by focusing on “equal participation” of women in all aspects of security. One sign of progress comes from the American military. Ambassador Jean Manes and Adm. Craig Faller, the civilian and military heads of U.S. Southern Command, note that peace negotiations are significantly more likely to succeed when women are involved.

Since 2000, the U.N. Security Council has approved nine more measures promoting the integration of women in peace strategies. As the U.N. again looks at women’s role in preventing and ending conflict, the evidence keeps piling up that gender equality is a tool for peace.

Report card on gender equality in peacemaking

Twenty years ago this month the U.N. Security Council urged countries to involve more women in preventing conflict and building peace. Resolution 1325 was hailed as a landmark. It was based on a growing recognition that women and children are disproportionately affected by armed conflict and that women in roles from foot soldier to negotiator are critical in preventing it.

Progress toward that goal has been slow. Yet the idea has taken hold as shown in debates this month at the United Nations among diplomats and interest groups. In an open letter, 558 civil society organizations from 102 countries wrote that the architects of Resolution 1325 created history by focusing on “equal participation” of women in all aspects of security.

That need for equal participation is shown in the scope of modern conflicts. Every year since 1990, between 40 and 68 countries, home to 46% to 79% of the world’s population, have been involved in armed conflict, according to estimates published in The Lancet. At the start of the 20th century, 90% of people killed in conflict were combatants. By the start of the 21st century, that number had flipped: 90% of war casualties were civilians.

One sign of progress comes from the American military. Ambassador Jean Manes and Adm. Craig Faller, the civilian and military heads of U.S. Southern Command, note that peace negotiations are significantly more likely to succeed when women are involved. “Hard-won experience tells us that women are key to preventing conflict before it breaks out, and that their participation enables communities to curb escalating violence and defuse tensions between groups,” they write in Americas Quarterly.

Since 2000, the U.N. Security Council has approved nine more measures promoting the integration of women in peace strategies. Despite that, countries have not responded with much financial or political support. One example is the slow rise in the number of women in uniform. In 1993, women made up 1% of deployed troops. This year, they account for about 4.8% of military contingents and 10.9% of police units in U.N. peacekeeping missions. That is well below the pace needed to meet U.N. targets of women contributing 15% of deployed personnel, 30% of police units, and 25% of military observers and staff officers.

Outside the West, Latin America has seen perhaps the most significant advances for women in military and strategic roles. In the past decade, Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil, El Salvador, and Guatemala have adopted plans to integrate women into their armed forces. Brazil, Colombia, and El Salvador now have women flying combat aircraft. Female soldiers from Latin America are serving in peacekeeping missions in Sudan and Central African Republic.

In many countries, however, the role of women in combat remains contested. Skeptics point to a 2015 U.S. Marine Corps study that found all-male units outperformed gender-integrated units in physical and skills-based drills. Yet there is broad consensus that women bring a perspective to military planning and peacekeeping operations that engender trust and defuse conflict. They help open greater access to civilian populations in conflict zones, enabling better intelligence gathering. Their presence in uniform has been shown to decrease the use of excessive force and reduce the risk of sexual exploitation.

As the U.N. again looks at women’s role in preventing and ending conflict, the evidence keeps piling up that gender equality is a tool for peace, especially in reducing the killing of innocent civilians in war.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Healed of sciatica

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Terri Murdock

Disheartened by a doctor’s advice that she learn to live with the pain of sciatica, a woman turned wholeheartedly to Christian Science for healing. The result was complete freedom from the pain she’d experienced for years, and the problem never returned.

Healed of sciatica

Shortly after I was married, I talked to a doctor about a problem that I had been trying to ignore. For several years I had suffered from pain down the back of my legs that was especially bad at night. He diagnosed it as sciatica and told me I could have an operation, but he advised against it. He said it would be best if I could learn to live with the pain.

The diagnosis scared me. I certainly didn’t want to live with the pain! I was a relatively new student of Christian Science, and the next day I decided it was time to get serious about addressing this problem through Christian Science. I called a Christian Science practitioner for prayerful treatment.

The practitioner helped me see that what the material senses were reporting – or even what the doctor had diagnosed – was not the reality of my being. She wasn’t saying that I had been misdiagnosed, but rather reminding me that God, divine Mind and Spirit, created me, so I was actually much more than a flawed mortal. As the spiritual idea of Mind, I could not become damaged, painful or diseased.

Divine Mind always knows us as spiritual and perfect, and we can know ourselves that way, too. We are built on a spiritual foundation upheld by Christ, Truth, not by matter. God, good, is the infinite Principle of the universe, and this condition was not in accord with God’s law of goodness. So I had divine authority to dismiss the diagnosis as not part of my true, spiritual identity.

The practitioner knew I enjoyed playing the piano, and she encouraged me to play hymns from the “Christian Science Hymnal,” singing along and focusing on the healing message behind the words. One hymn I especially loved was No. 51, which begins:

Eternal Mind the Potter is,

And thought th’ eternal clay:

The hand that fashions is divine,

His works pass not away....God could not make imperfect man

His model infinite;

Unhallowed thought He could not plan,

Love’s work and Love must fit.

(Mary Alice Dayton)

I spent some time at the piano, singing and lingering over the healing truths in the hymns. When I finished, I was at peace and free of any pain. Since then I’ve been fully active and enjoyed a career that required me to be on my feet for many hours at a time, without any ill effects.

What particularly stands out to me from this healing is the practitioner’s absolute conviction that health and well-being are upheld by divine Mind, not medical procedures; this did away with my fear. Also meaningful was the faith I had in the truthfulness of the sweet promises of the Christian Science hymns – promises of God’s ever present love and care.

To me this experience is a powerful reminder that when we nurture a childlike trust in the power of divine Truth, healing results are assured.

A message of love

Some images to reflect on

A look ahead

That’s a wrap for the news. Come back Monday. Our Washington bureau chief Linda Feldmann has been traveling with the president and we’ll have a letter from Air Force One.