Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

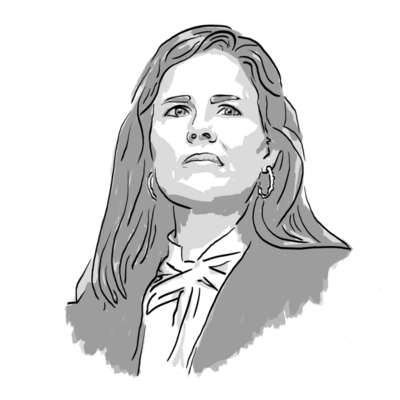

Kim Campbell

Kim Campbell

In Colorado, we’ve been inhaling smoke for months from some of the largest wildfires in the history of the state and region.

A snowstorm Sunday helped slow the raging fires and allowed people to breathe again. With the moisture came a chance to take in something else: the American thankfulness and generosity that have been overshadowed in a heated election year.

One Coloradan whose cabin was spared tweeted “tears of gratitude” to the members of Engine 1446 from Meeker who left him a note apologizing for not being able to save his shed and explaining why they damaged a fence to protect his home. “If this note finds you we must have done something right,” the firefighters wrote. “Things got really hot we stayed as long as possible.”

An inn owner in Boulder let people affected by evacuation orders – and their pets – stay for free. And viewers of NBC affiliate 9News donated more than half a million dollars to the Red Cross of Colorado and Wyoming through the station’s “Word of Thanks” weekly $5 micro-giving campaign.

“Everybody’s dropping all the hate and they’re just gathering together regardless of what walk of life they come from,” Hilary Embrey, who lost her home in the Cameron Peak fire, told 9News.

When the smoke cleared in Colorado, the compassion was still there. A hint of what’s possible for the rest of the U.S. after next week’s election.