- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Post-truth politics: As Trump pushes ‘fraud,’ partisans pick their own reality

- Moscow kids get teachers on screen, but trainees in class. Will it work?

- A ferry sank, killing hundreds. Now, a film stirs decades-old Baltic mystery.

- Why Big Tech faces rising pressure in Congress and courts

- Ski resorts expect a busy season. Can they find enough workers?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What teachers want you to know: ‘We love our students’

Kim Campbell

Kim Campbell

This week I asked friends and family who are veteran teachers to share what work has been like for them lately.

Though overwhelmed, they are hopeful and determined. They are frank about the obstacles they face: trying to keep kids engaged online; having to give one-on-one support from 6 feet away; providing equitable education. For one third grade teacher, “meeting the needs of the students” is the biggest challenge.

They also say that partnerships with parents have frayed. “In the spring teachers were viewed as heroes, now many parents are angry and upset,” writes one friend. “They feel as if teachers aren’t doing their jobs.”

If given the opportunity, these educators would try to dissuade people of that idea. “I wish the public knew how much we love our students, love our jobs, and want to be able to do all we can for them through all of this,” writes one. Another explains, “I wish parents knew that we are trying. It is not perfect, but we still love your children and we want to be with them. We also want to keep our own families healthy.” And another: “We are giving it our all, every day.”

What keeps them going are the students, and the resilience they regularly witness: “What gives me hope are the kids who log in and try their best despite the many barriers they face.” Another puts the road ahead in context: “Great generations are often formed through tough times,” she writes, “and I see our kids as truly giving us a bright future.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Post-truth politics: As Trump pushes ‘fraud,’ partisans pick their own reality

When Americans can’t agree on the truth, what does that mean for democracy?

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

President Donald Trump’s false insistence that he is the rightful winner of the 2020 election has exposed like nothing else the possibility that America is becoming a post-truth society, where political partisans can’t agree on a unifying framework of facts, and emotion and personal belief steer public opinion.

Supporters of President-elect Joe Biden point to his solid leads in key battleground states as evidence he won fair and square. Many supporters of President Trump are convinced by allegations, so far unsupported by evidence, that the election was rife with fraud.

State election officials of both parties insist that the nation has managed the heroic act of holding a fair and free vote, with no more glitches than normal, despite a pandemic and historic turnout.

The divide over what constitutes truth is not just due to partisan media or a president who fact-checkers rate as an unparalleled source of falsehoods. It also stems from social media, the blurring of fact and opinion, and the decline in trust in national institutions and expertise.

As Republican Al Schmidt, a Philadelphia city commissioner, said while speaking for the undersung election workers in a CNN interview: “One thing I can’t comprehend is how hungry people are to consume lies.”

Post-truth politics: As Trump pushes ‘fraud,’ partisans pick their own reality

President Donald Trump’s false insistence that he is the rightful winner of the 2020 election has exposed like nothing else in his time in office the possibility that America is becoming a post-truth society, where political partisans can’t agree on a unifying framework of facts, and emotion and personal belief steer the winds of public opinion.

Since the vote, Democrats and Republicans seem to be living in different worlds. Supporters of President-elect Joe Biden point to his solid leads in a number of key battleground states and record-breaking overall vote total as evidence he won fair and square. Many supporters of President Trump have been convinced by right-wing media allegations, so far unsupported by evidence, that the election was rife with fraud – with dead people voting, ballots tossed, and corrupted election machines changing thousands of votes at a swipe.

Caught in between are state and national election officials of both parties who insist that the nation has managed the heroic act of holding a fair and free vote, with no more glitches than normal, despite a pandemic and historic turnout. They point out that the Trump campaign’s many lawsuits about the results have virtually all collapsed and are doing nothing but further documenting the solidity of Mr. Biden’s win.

Republican Al Schmidt, a Philadelphia city commissioner, perhaps spoke for many of these undersung election workers in a CNN interview last week.

“I realize a lot of people are happy about this election and a lot of people are not happy about this election,” said Mr. Schmidt. “One thing I can’t comprehend is how hungry people are to consume lies.”

This divide over what constitutes truth and facts has been developing for some time, say experts. It’s not just the result of the rise of right-wing media outlets such as Fox News or the election of a president whom fact-checkers rate as an unparalleled source of political falsehoods.

It’s also about the rise of social media, the blurring of lines between fact and opinion, and the decline in trust of many national institutions and even the nature of expertise.

“It’s a phenomenon that’s not tied to one party or administration. ... It’s not only an information problem. It’s about the context in which information exists,” says Jennifer Kavanagh, a senior political scientist at Rand Corp. and co-author of “Truth Decay: An Initial Exploration of the Diminishing Role of Facts and Analysis in American Public Life.”

Unaddressed it could threaten democracy itself. As former President Barack Obama pointed out this week in an interview with the Atlantic, if we lose the ability to sort the true from the false, then by definition the marketplace of ideas does not work – and neither does democracy. Our whole theory of knowledge – epistemology – is threatened.

“We are entering an epistemological crisis,” President Obama told Atlantic editor Jeffrey Goldberg.

Truth and politics

It may not have begun with him, but President Trump has proved that truth-bending politics has its advantages. A candidacy that began with Mr. Trump leveraging “birtherism” – the lie that Mr. Obama was not born in America – is ending with a president clinging to false stories about why he has won reelection, despite overwhelming evidence he has lost.

During the campaign, Mr. Trump insisted without evidence that mail-in ballots were rife with fraud. He cast doubt on ballots counted after Election Day, though lengthy ballot tallies and checks are routine. Since the vote he has seized on small discrepancies in county vote counts as reasons why the ballots of entire states should be invalidated and state legislatures should name him as the winner of their Electoral College votes.

The president may sincerely believe these moves will keep him in the Oval Office. But in the past, he has used falsehoods and misdirection just to throw dust in the air, overwhelm the media, and create an appearance of scandal to delegitimize opposition. In his famous outreach to Ukraine – for which he was impeached – Mr. Trump only pushed for an investigation into Hunter Biden’s business deals to be announced, not completed or even begun.

In his fight to stay in office, the president has often taken a bit of true information and presented it out of context. On Wednesday night, he tweeted that in Wisconsin, former Vice President Biden had received “a dump of 143,379 votes at 3:42 AM, when they learned he was losing badly.” What Mr. Trump did not mention was that the “dump” was a routine release of ballots by a number of counties and that not all of the ballots were for Mr. Biden, as a Reuters fact check clarifies.

While Rudy Giuliani gives press conferences, as on Thursday, alleging widespread fraud, in court he is far more measured: “This is not a fraud case,” he told a federal judge in Pennsylvania Tuesday.

This sort of activity could continue to cloud Mr. Biden’s presidency, says Whitney Phillips, a lecturer on media literacy and misinformation at Syracuse University.

“It is creating a permission structure to not accept Joe Biden as president,” Dr. Phillips says.

That may have real-world consequences, she adds. If a quarter of the population does not think Mr. Biden is a legitimate president, what does that mean for his coronavirus response plans? Will he face more entrenched opposition to masking recommendations or vaccine distribution?

“This is not just an abstract conversation about electoral consequences 10 years down the road,” she says.

Dr. Phillips says it is also important to place Mr. Trump’s current charges in context. The president began constructing a narrative about the “deep state” and shadowy enemies almost from the moment he entered office. It has been a thread linking the investigation of special counsel Robert Mueller, the impeachment effort, and more fervid false conspiracy theories such as those espoused by QAnon. This summer he began pushing a message that the Democrats would steal the election from him by any means necessary. This feeds a constant media diet by right-wing outlets that wraps around and encompasses many issues and “explains” confusing developments.

“It’s very hard to see outside the narrative. People are convinced of the underlying idea, and they’re going to seek that story out,” Dr. Phillips says.

“We wanted to support our president”

Many supporters of President Trump believe wholeheartedly that the vote was rife with wrongdoing, with dead people voting, ballots falsified, and corrupted election machines changing thousands of votes at a swipe. A recent Monmouth poll, for instance, found that 77% of Trump backers believed Mr. Biden’s victory was due to “fraud.”

That’s in contrast to the 60% of Americans who believe Mr. Biden won the election fair and square, according to Monmouth.

Sign-waving fans of the president interviewed at Nov. 14’s “Million MAGA March” in Washington were certain there was no way he could have lost legitimately. They cited the size of Trump rallies, Mr. Biden’s flaws, and U.S. economic strength.

Janine Luzzi, a financial analyst from New Jersey, woke up at 5:15 a.m. to drive down to Washington with a friend.

“We wanted to support our president. We know he’s been cheated,” said Ms. Luzzi.

Terry and Kevin Roche drove up from their hometown of Charlotte, North Carolina, the day before the rally. They felt it was important to attend because they don’t think the election process is over, and that courts and legislatures will discover there was fraud.

“Historically, the economy, scandals, all the measures that we use to judge a candidate – Joe Biden could not have done well. So it’s very inexplicable. Simply because people don’t like Donald Trump’s tweets he would lose an election?” said Mr. Roche, who works in computers.

Cathy Boyd, a nurse from western Massachusetts, spent seven hours on a train to reach the rally. She says she felt she had to come and support the president because his opponents are simply stealing the election.

“I tell people that President Trump exposed the evil and corruption. He’s the only person who can do it. He’s got his own money,” said Ms. Boyd.

Why would Trump supporters be so sure about fraud in the election, when evidence to support that claim is lacking, more than two dozen court cases have gone against the president’s campaign or been withdrawn, and a majority of the country believes otherwise? Media silos may be one big reason. A quick glance at news headlines on Nov. 18 shows the split: The New York Times and other mainstream sources led with stories about the national coronavirus spike, with a smattering of pieces about the organization of the incoming Biden administration. Fox News, Breitbart, and OANN lead with Trump lawyer Mr. Giuliani laying out a “path to victory,” and the continuing struggle to certify vote results in Michigan’s Wayne County.

Many adults now get much of their news through Facebook and other social media sites, where it remains difficult to ascertain the validity of stories. At last weekend’s MAGA March, many participants repeated allegations that have been debunked by fact-checking, such as the false charge that Dominion Voting System machines were rigged to throw votes to Mr. Biden. As The Wall Street Journal pointed out in an editorial Thursday, if there had been a problem with Dominion machines, the hand recount Georgia just completed would have uncovered them. Dominion machines also were used in South Carolina and other states that voted for the president.

In his interview with The Atlantic, former President Obama criticized what he called the nation’s “new malevolent information structure.” America no longer has a trusted figure such as Walter Cronkite to bring us all together, he said. Locally owned and controlled TV stations are dwindling. Local newspapers run by experienced journalists are dying off.

“Maybe most importantly, and most disconcertingly, what we’ve seen is what some people call ‘truth decay,’ something that’s been accelerated by outgoing President Trump – the sense that not only do we not have to tell the truth, but the truth doesn’t even matter,” said the former president in a separate interview with “60 Minutes.”

Combating “truth decay”

“Truth decay” is a phrase Mr. Obama likely lifted from a lengthy 2018 Rand study of the same name.

Since his interviews “we definitely have gotten renewed interest,” says Dr. Kavanagh, who co-wrote the book with Rand president and CEO Michael D. Rich.

Truth decay, as defined by Dr. Kavanagh, is a set of four interrelated trends: increasing disagreement about facts and interpretations of facts and data, more and more blurring of lines between opinions and facts, an increased volume of opinions, and lowered trust in formerly respected sources of factual information.

Causes of these trends include changes in information providers, such as the rise in social media; an educational system that places less emphasis on media literacy and critical thinking; and political and demographic polarization.

Damaging consequences of this situation include the erosion of civil discourse, political paralysis, and uncertainty about national policy.

“We’re describing a situation in which people don’t know what’s true and what’s not – and they don’t know where to turn to find fact-based information,” says Dr. Kavanagh.

Solutions to truth decay could include more teaching about civic responsibilities and media literacy.

“Understanding the responsibility to become informed, and then having the tools to do it,” says Dr. Kavanagh.

There is also much that journalism can do to help overcome the challenge, according to Rand. A first step would be much clearer separation of fact and opinion articles and broadcasts. Consumers conflate the two much more than many journalists realize. A second step would be an increased attention to breaking up high-quality news in small, digestible chunks. That’s a market currently dominated by low-quality news providers.

The online news environment is a big part of the problem. Right now, it’s a problem with more questions than answers. How to balance privacy and access against manipulation and hate speech? Are the companies themselves the right people to make those decisions?

Overall, with effort truth decay can be addressed, says Dr. Kavanagh.

“It’s not inevitable,” she says.

Moscow kids get teachers on screen, but trainees in class. Will it work?

Amid the pandemic, how do schools balance the education of young students with the health of older teachers? In Moscow, the answer is to move the vulnerable teachers remote and bring educators in training into the classroom.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

While Moscow schools have largely shut down as COVID-19 cases rise again, city officials have decreed that students in grades one to six need to have regular classes and daily face time with teachers. That has led to an unusual experiment in Moscow’s schools.

Healthy young volunteers have been recruited from Moscow’s several pedagogical colleges and universities, which train teachers, to act as in-class tutors. Meanwhile older and more vulnerable regular teachers deliver their lessons from the safety of their homes, displayed on a big computer screen at the front of the classroom.

“We know that many countries are in this situation, so we’re not the only ones facing this challenge,” says Sergei Graskin, a Moscow school principal. “It is of critical importance to protect our pupils and teaching staff in this pandemic. But we have to get the balance right.”

“The whole conservative model of teaching, where a teacher stands in front of a class and delivers a set amount of material and assigns huge amounts of homework, has been profoundly challenged,” says Alexander Adamsky, editor of an online journal of education. “A lot of problems have been exposed, but the system has also been forced to adopt some innovative new methods.”

Moscow kids get teachers on screen, but trainees in class. Will it work?

All across Moscow, schools are mostly empty amid the city’s raging second wave of the coronavirus pandemic, as city government orders older pupils and staff to shelter at home and continue their studies online.

But, in a controversial move, Moscow officials have decreed that younger pupils cannot afford a repeat of the spring’s total lockdown. Rather, students in grades one to six need to have regular classes and daily face time with teachers.

That has led to an unusual experiment in Moscow’s schools.

Inside one of those – School No. 1580, a large, sprawling grade school that occupies most of a block in a leafy neighborhood in the center of the city – healthy young volunteers have been recruited from Moscow’s several pedagogical colleges and universities, which train teachers, to act as in-class tutors. Meanwhile older and more vulnerable regular teachers deliver their lessons from the safety of their homes, displayed on a big computer screen at the front of the classroom. A few senior students, nearing graduation, are even being handed full teaching responsibilities on a temporary basis.

“We know that many countries are in this situation, so we’re not the only ones facing this challenge. It is of critical importance to protect our pupils and teaching staff in this pandemic. But we have to get the balance right,” says Sergei Graskin, the school’s principal.

“Older pupils can study mostly online because they know how to use the technology and discipline themselves. This is not the case for the youngest ones. They absolutely need personal attention, to have their questions answered and be shown how to do things. It also seems that the younger children are the least vulnerable to this virus, and we have not been seeing many infections in our school,” he says.

Learning on the job

The scheme appears to be working well. In several classrooms, lessons are in full swing, with teachers delivering their material and handing out class work remotely, visible on a large screen. Meanwhile a masked student teacher hovers among the kids, directing their attention if it wanders, and later giving supplementary tutorials.

In one class, fifth-year pedagogical student Irina Vinogradova is teaching a history lesson on her own. She has a big, computerized diagram showing the world of the ancient Near East, and she’s explaining to the kids how civilizations interacted with each other in the past and continue to affect the present, spreading knowledge, technologies, and religions far beyond their own time and place.

She seems delighted with the opportunity to be a full teacher, even if unpaid and temporary. She has agreed to do it for one month, but that could be extended depending on the pandemic situation.

“This is so much better than regular practice teaching,” she says. “There is no teacher in the room, so I can try out the methods I’ve been learning, and get the full experience. I’m replacing an older teacher here, but at the same time I am continuing with my studies at the pedagogical institute. So, I am learning fast. I feel very comfortable with it. If I run into a problem, senior staff are being very helpful. And WhatsApp always works.”

Finding new ways to teach

In the Russian educational system, some schools orient on a particular specialization from the earliest grades. School 1580 has an engineering focus, and maintains a close relationship with Bauman State Technical University, which provides it with a lot of assistance and takes in many of its graduates. Thanks to that technical edge, this school may have been better placed than some others to adapt and change amid the severe challenges of the lockdown earlier this year.

Yelena Ivanova, a social studies teacher with 30 years experience, says that when the first wave of the pandemic hit earlier this year, it disrupted everything and no one had any idea what to expect.

“It was really awful, like nothing we’d ever experienced,” she says. “But we gradually discovered that we had all the tools we needed to deal with it. All these technologies were in place. We had computers. We were already customizing lessons for individual students, but it had all been in the form of routine computer lessons. When this happened, we needed to put it all together in new ways, to keep as much education going as we possibly could.”

But she has also learned that there is no substitute for direct classroom contact between teacher and pupils, she says.

“Even for older students, who know how to use the devices and study on their own, some issues can only be dealt with face-to-face,” she says. “It’s a matter of socialization, which is crucial to the learning process. We’ve discovered a lot about how technology can assist, but there will never be any replacement for personal contact.”

One of the educational scholars who advised Moscow about the experimental plan to throw pedagogical students onto the front lines for the pandemic’s duration is Yefim Rachevsky, director of the Tsaritsyno Education Center in Moscow. He says that it’s a crisis measure that should probably be considered for permanent implementation.

“Medical students have to go through years of internship, but student teachers only get brief periods of actual practice in classrooms before they graduate,” he says. “This stopgap measure has shown a way for students to integrate more thoroughly into the system, understand the job, and for employers to see if they’re up to it.”

“Why practice on my kids?”

The project has drawn fire from some teachers and parents, who see it as an inadequate solution that the authorities are taking too much credit for.

“I wonder why anyone thinks a young student can replace an experienced older teacher?” says Alexei Bykov, father of two sons, one of whom is in grade three and the other in grade six. “I understand that they need practice, but why practice on my kids? Last spring we had 2 1/2 months of so-called remote study, and the results were terrible. In fact, many families cannot afford to have their kids at home, studying by computer. I’m not in bad shape, but I can’t afford to have two computers at home. ...

“I want my children to study at school with their teachers. Even if they need to do something like two weeks on and two weeks off it would be preferable to this, which I think will only lead to chaos.”

Yelena Kosarikhina, a retired Moscow school principal, says that inexperienced students simply cannot handle the job.

“Sure, young students may know how to use the technology, but they lack vital teaching experience,” she says. “I can’t see this working. And how long is it going to go on? At first they said it would just be a month or two. Now they’re saying a year or more. The longer it continues, the more older teachers will be sidelined, and the quality of education will deteriorate.”

The pandemic has been a shock to the whole educational system, and time will tell what’s been learned through efforts to manage the crisis, says Alexander Adamsky, editor of Vesti Obrazovaniya, an online journal of education.

He praises the young students who are stepping up to help in the classrooms, calling them “something like a volunteer corps, called into service in war time.”

“But the whole conservative model of teaching, where a teacher stands in front of a class and delivers a set amount of material and assigns huge amounts of homework, has been profoundly challenged,” he says. “As a result of this emergency, our educational officials are in a state of near paralysis, parents are up in arms, and schools have been forced to seek their own solutions. ...

“A lot of problems have been exposed, but the system has also been forced to adopt some innovative new methods. Let’s wait and see whether it will all lead to a better understanding of our children’s educational needs.”

A ferry sank, killing hundreds. Now, a film stirs decades-old Baltic mystery.

The sinking of the MS Estonia ferry in 1994 affected all of Estonia and Sweden. Today, revelations in a new documentary are bringing the disaster back to the forefronts of their national psyches.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The sinking of the MS Estonia passenger ferry in the early hours of Sept. 28, 1994, under mysterious circumstances in the Baltic Sea, is the worst peacetime maritime disaster in European waters. All told, 852 of the 980 passengers and crew aboard the massive vessel died in the tragedy.

For years, the official cause of the sinking has been written off as a mechanical failure. But now, after Swedish journalist Henrik Evertsson incorporated new footage of the ferry wreckage into a documentary, the question of what sank the ferry has been reopened.

The official 1997 report on the tragedy indicated that the bow door of the ship had separated from the rest of the vessel, leading to the lightning-fast flooding. But Mr. Evertsson’s film crew discovered a 14-foot-long hole in the wreckage’s hull, contradicting the report’s finding about the lack of external damage and suggesting that a collision may have caused the catastrophe.

“I thought the documentary was credible and trustworthy,” says survivor Kent Härstedt. “I also am upset that it took a private filmmaker and journalist to do a job that three democratic states should have properly done in the first place.”

A ferry sank, killing hundreds. Now, a film stirs decades-old Baltic mystery.

Mart Luik was in Paris when he found out that the MS Estonia ferry had sunk, killing more than 850 people, a quarter century ago.

“I ... rushed to call to see if any of my family were aboard and to see what happened,” Mr. Luik, now an adviser in the Estonian foreign minister’s office, says. “I think all Estonians of a certain age remember where they were when they heard about the Estonia.”

The sinking of the passenger ferry in the early hours of Sept. 28, 1994, under mysterious circumstances in the Baltic Sea is the worst peacetime maritime disaster in European waters. All told, 852 of the 980 passengers and crew aboard the massive vessel died in the tragedy.

Citizens of seventeen nations died when the MS Estonia capsized. It was especially devastating to the two countries with the most people on board: Estonia and Sweden, who lost 285 and 501 citizens respectively. The scale of the tragedy, and the small size of the nations involved, meant that it struck across their entire populaces. “Sweden is so small that basically everyone knew someone who drowned,” says Rolf Sorman, a Swedish survivor.

For years, the official cause of the sinking has been written off as a mechanical failure – a finding that has not sat well with survivors who were on the MS Estonia at the time. But now, after Swedish journalist Henrik Evertsson incorporated new footage of the ferry wreckage into a new documentary, the question of what sank the ferry has been reopened. And the revelations he has brought to light are stirring the two countries to rethink one of the greatest tragedies in their modern history.

A sudden bang, a ship sinking

The MS Estonia was the pride of its newly independent namesake republic. The 15,000-ton steel vessel, 510 feet long and nine decks high, featured a swimming pool, a sauna, a casino, and a cinema, along with labyrinths of cabins with accommodations for up to 2,000 people for the overnight trip between Sweden and Estonia. It also had a car deck that stretched from bow to stern through the hull’s insides. In port, the car deck was accessed through a special bow that could be raised to allow vehicles to roll on and roll off.

Around 1 a.m. on Sept. 28, 1994, the MS Estonia, then en route from Tallinn, Estonia, to Stockholm, foundered in a severe Baltic storm off the southwest Finnish coast. As numerous survivors have attested, a sudden clanging sound reverberated through the ship.

“I was sitting in the ship’s bar, quite sober, when a sudden ‘bang’ took place,” says Swedish Special Envoy to the Korean Peninsula Kent Härstedt, then a young foreign ministry official. “Suddenly the ferry was immediately thrown to the side.”

“I immediately thought that the ship had hit something, perhaps a container, and changed course,” said Mr. Sorman, who also happened to be up at that hour.

“Actually, the blow was so strong I was too stunned to think anything,” says Mr. Härstedt. “Then everyone was falling.”

As Mr. Sorman, Mr. Härstedt, and others fought their way to the passenger deck, the car deck became flooded, causing the ferry to capsize and sink in less than 50 minutes. At the same time the door, and putative cause of the disaster, came off entirely.

In 1997, the Joint Accident Investigation Committee (JAIC), the body appointed by the Estonian, Swedish, and Finnish governments, issued its report on the sinking. It indicated that the locks on the bow door had failed from the strain of the immense waves hitting the MS Estonia, causing the door to be separated from the rest of the vessel, pulling the ramp behind it ajar, leading to the lightning-fast flooding. Although the investigators found other contributing or aggravating factors, including the ship’s high speed and the MS Estonian crew’s passivity and lack of safety training, that was deemed the principal cause of the disaster. The JAIC’s report indicated no external damage to the hull.

“It’s engraved in my memory forever”

However that was not the end of the story for the families of the deceased, nor the survivors, like Mr. Sorman and Mr. Härstedt, who were frustrated by the investigators’ refusal to interview the survivors. Mr. Sorman ended up being one of three survivors in his traveling group of twelve, while Mr. Härstedt was one of only two in his group of two dozen.

“We were never given the opportunity to share our information,” says Mr. Härstedt. “It was very upsetting. ... It still is.”

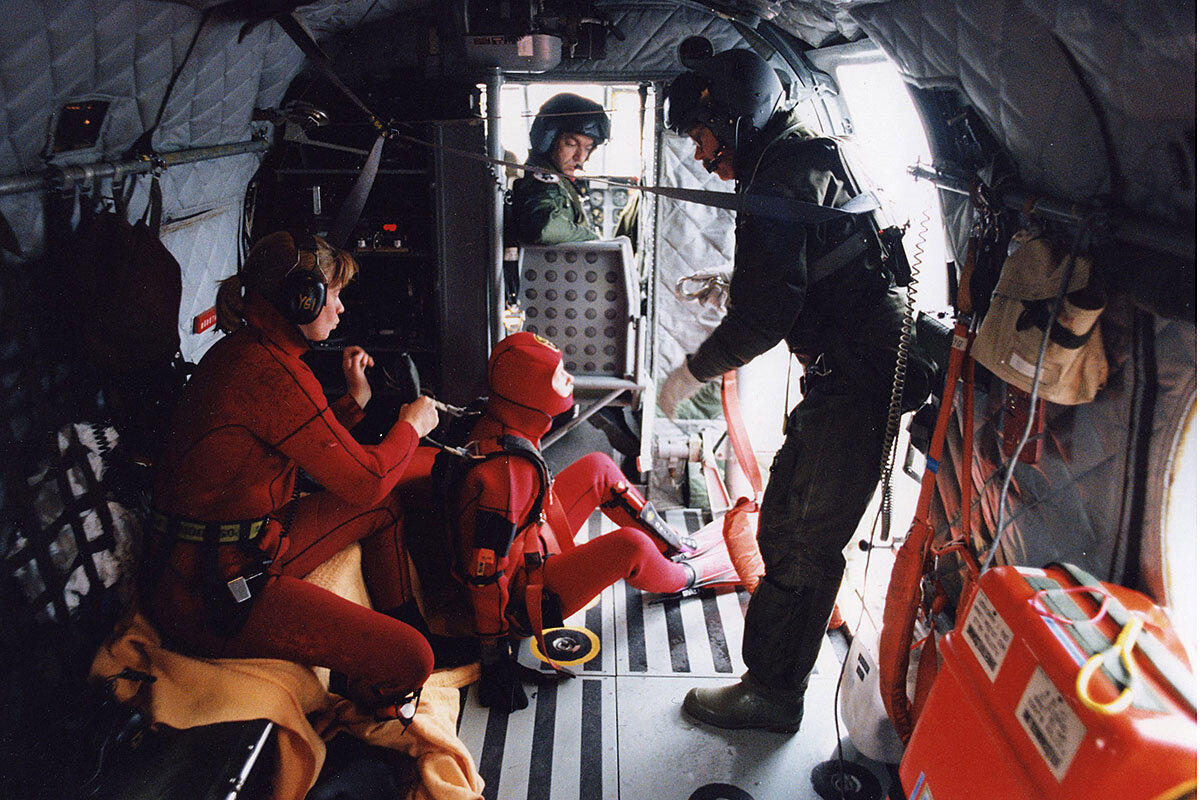

And the sinking traumatized Estonia and Sweden. This correspondent reported on the tragedy for The New York Times in Helsinki, and later in Turku, the Finnish city nearest the sinking, where the haggard, too few survivors from the MS Estonia were helicoptered in, along with Stephen Kinzer, the Times’ Berlin bureau chief who anchored the paper’s coverage.

Mr. Kinzer still recalls the crater-like impact the disaster had on the two societies. “Death on this scale was a cataclysm that deeply shook people in both countries. It seemed to strike every family. People were stunned. The emotions went as deep as any I’ve ever seen or felt. And with that level of shock and grief surrounding you, even reporters can’t help being affected by it.

“To this day I remember looking at people’s blank faces in Turku and [Estonia’s capital,] Tallinn,” says Mr. Kinzer, who now teaches at Brown University. “Even for those of us not directly affected, it was a traumatic episode to live through. It’s engraved in my memory forever.”

The catastrophe also made a lasting impression on Mr. Evertsson, who was only 7 when he first heard about it on the radio. Investigating the sinking has been a priority for him ever since he became a journalist.

It took some years for Mr. Evertsson, who directed the documentary along with his co-producers Bendik Mondal and Frithjof Jacobsen, to acquire the financing from Discovery Networks Norway for the expensive – and potentially illegal – expedition they envisioned. An international treaty deeming the MS Estonia a sacred site forbids approaching it or diving near it.

Nevertheless, Mr. Evertsson’s team, including a Norwegian diving company, traveled to the site on a ship registered in Germany – the only nation on the Baltic Sea that did not sign the aforementioned treaty. And they went ahead and filmed the length and breadth of the sunken ship.

In the process, they discovered a 14-foot-long hole in the ship’s hull, contradicting the JAIC report’s finding about the lack of external damage and suggesting that a collision may have caused the catastrophe.

A new investigation?

On Sept. 28, the 26th anniversary of the disaster, their five-part documentary, “Estonia: The Find That Changes Everything,” was broadcast throughout the Baltic region. The effect of the film, as well as the furor it caused, was immediate.

Among those watching were survivors Mr. Sorman and Mr. Härstedt.

“My reaction was that the film confirmed the Archimedean principle also applied to [the MS] Estonia,” says Mr. Sorman, now a school headmaster in Nacka, Sweden. “For a ship to sink there must be a hole beneath the waterline. I thought the film was very well done.”

“I thought the documentary was credible and trustworthy,” Mr. Harstedt agrees. “I also am upset that it took a private filmmaker and journalist to do a job that three democratic states should have properly done in the first place.”

The reaction of the Estonian, Swedish, and Finnish governments was more complicated. For its part, the Estonian government took it seriously enough to dispatch its prime minister and foreign minister to Stockholm and Helsinki to discuss the film and its findings with their counterparts.

At the same time, all three governments have reserved judgment about the film’s reliability. As Mr. Luik, who is assisting with the new investigation, put it, “We have no reliable information which would disprove the main conclusion of the JAIC’s report” – that the failure of the bow door caused the MS Estonia to sink.

That said, Mr. Luik continues, “it is obvious that we need to conduct a new technical investigation which is exhaustive, technically sophisticated, transparent, and independent.” Currently the three governments “are discussing the proper criteria for the new investigation.”

“I simply do not trust the original investigative entities to investigate themselves,” says Mr. Sorman. “For me this is all about trust, as well as about maritime safety.”

“To conduct a new trustworthy investigation is of the utmost importance out of respect for those who died, as well as their relatives, and everyone else who was impacted by the disaster,” says Mr. Härstedt.

Ramifications

Mr. Evertsson says that his purpose in making the film was not necessarily to disprove the JAIC report, but to posit another theory for why MS Estonia sunk so quickly that might account for the new hole he discovered.

“I want to be clear that we didn’t and don’t make any conclusions,” he says. “It’s up to the experts to investigate further.”

In the meantime, the Swedish government indicted Mr. Evertsson for trespassing on the MS Estonia site, for which he faces up to two years in prison. The case goes to court in January.

“To perform the critical journalism that was necessary in the case of the Estonia was more important than the charges,” he says. “I welcome the opportunity to discuss the film in a court of law.”

“People are calling me and crying and thanking me because now maybe the truth can be revealed,” he says. “For me that is sufficient.”

On Thursday, Mr. Evertsson received validation of another kind when he was awarded the Swedish Grand Prize for Journalism, the Swedish equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize, for Best Scoop of the Year.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct Mr. Luik's employment in the Estonian government.

The Explainer

Why Big Tech faces rising pressure in Congress and courts

The rise of the internet and social media occurred in an era of relatively light regulation of technology firms. Now, in an era of concern about the clout of a few tech giants, attitudes in Washington are shifting.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

While the tech industry delivers many benefits to society, governments around the world have been showing a rising interest in regulating it. Digital platforms, they worry, may be encouraging tech overuse and eroding privacy among consumers, curbing competition among businesses, and failing to adequately manage their societal role as gatekeepers of information.

In the U.S., tighter antitrust oversight appears to be already taking shape. On Oct. 20, the U.S. Justice Department sued Google for using anticompetitive practices to maintain its dominance over search and search advertising. And many Democrats in Congress support legislation to break up tech monopolies.

Separate questions are swirling about what role tech giants should play in controlling misinformation online, and Republican allegations that the firms have an anti-conservative bias. The Senate Commerce Committee has been considering whether changes are needed to a 1996 provision that protects internet companies from liability for what people say on their platforms, but also allows them to moderate their content as they see fit.

Why Big Tech faces rising pressure in Congress and courts

For the past two decades, the U.S. government has taken a relatively hands-off approach to Silicon Valley, as tech companies have gained increasing influence over our day-to-day lives.

But that may be changing. Google, Facebook, and Twitter confront a series of government actions aimed at restricting their behavior, and are besieged by questions from Congress over how their platforms moderate the flow of information.

Q: Is Big Tech playing “monopoly”?

An October report prepared by Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee outlined what the committee says are anti-competitive practices by digital-era firms like Apple and Amazon. The report quoted Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg mulling the price worth paying to buy up competitors – as the company has done with platforms like Instagram.

Now after years on the sidelines, antitrust regulators are taking action, at least in one case. On Oct. 20, the U.S. Justice Department sued Google for using anticompetitive practices to maintain its dominance over search and search advertising.

The suit claims that the company blocks rivals by paying device manufacturers to make Google their default search engine.

“The end result,” U.S. Attorney General William Barr said, “is that no one can feasibly challenge Google’s dominance.”

Google called the lawsuit “deeply flawed.” “People use Google because they choose to, not because they’re forced to, or because they can’t find alternatives,” said the company in a statement.

The suit mirrors the government’s successful 1998 case that said Microsoft forced computer manufacturers to bundle its web browser with its Windows operating system, thus locking out competitors.

Q: What about digital-era free speech?

When two congressional committees recently called for tech CEOs to testify, the reason was concern about America’s information diet, not just preserving competitive markets. On Oct. 28, the Senate Commerce Committee focused on potential changes to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which protects internet companies from liability for what people say on their platforms, but also allows them to moderate their content as they see fit.

The hearing touched a nerve with Republican senators, who blasted the CEOs of Google, Twitter, and Facebook for alleged anti-conservative bias.

The Senate Judiciary Committee, meanwhile, is focused on complaints that digital platforms intentionally limited the spread of a controversial New York Post article about Hunter Biden, which ran as his father, former Vice President and now President-elect Joe Biden, was in the final days of the presidential race.

This Tuesday, Republicans on the committee grilled Mr. Zuckerberg and Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey over their content moderation policies, with some, such as Senator Marsha Blackburn of calling for reform of Section 230.

Mr. Biden, in a July interview, said that the rule should not apply to Facebook and similar platforms. “[Facebook] is not merely an internet company,” he said. “It is propagating falsehoods they know to be false.”

The American Civil Liberties Union demurs: “Section 230 defines Internet culture as we know it,” the group says on its website. It’s why websites “can offer platforms for critical and controversial speech without constantly worrying about getting sued.”

Q: What does this mean for the future?

While the tech industry delivers many benefits to society, governments around the world have been showing a rising interest in regulation. The worries include that digital platforms may be encouraging tech overuse and eroding privacy among consumers, curbing competition among businesses, and failing to adequately manage their societal role as gatekeepers of information.

With a politically divided Senate, prospects for U.S. legislative action remain uncertain. But tighter antitrust oversight appears to be already taking shape, and many Democrats in Congress support legislation to break up tech monopolies. “It would be a historical anomaly if tech were not to be robustly regulated, as other systemically important industries such as banking and food were before it,” writes The Economist.

Writing in Jacobin, a leftist magazine that recently had a video removed from Facebook without explanation, Nicole Aschoff agreed that public opinion is shifting in favor of regulation. “Preserving the internet as a place of free expression while simultaneously protecting the electoral process, shielding users from harassment and abuse, and reining in the power of hate groups is an incredibly difficult task,” she wrote in July. “Indeed, one could argue that it is a defining challenge of the present moment.”

Ski resorts expect a busy season. Can they find enough workers?

Even in a pandemic, people want to get outdoors. That dynamic may help ski resorts survive, but they are having to look closer to home for their staff.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

As ski resorts start to open for a new season, the coronavirus pandemic has prompted protocols such as socially distanced lift lines and reduced capacity for indoor dining. Yet the industry is also benefiting from Americans’ desire to get out of their houses and into fresh air.

“People are excited to have this ability to have a respite from everything they’ve been dealing with the last several months,” said Ryan Huff of Vail Resorts, which has several Colorado ski mountains open already.

A key challenge for industry is staffing. Typically, a system of temporary visas brings about 7,000 workers from other nations – often students from the Southern Hemisphere who are on their summer breaks.

A visa ban by the Trump administration means that, for this season, ski facilities are recruiting closer to home. One focus is on college students who have some flexibility due to online classes or lengthened winter breaks.

“We’re still in the early days of our recruiting but we’re liking what we’re seeing,” said Dave Fields, president of Snowbird Resort in Utah. “People want to work outside in a healthy environment, to be in the mountains.”

Ski resorts expect a busy season. Can they find enough workers?

Last winter, Angella Reyes spent every day working with a panoramic view of blue skies and snow-capped Smoky Mountains of Idaho.

Ms. Reyes, a university student studying architecture from Lima, Peru, spent her Southern Hemisphere summer break working as a dishwasher and pre-cook at a mountaintop eatery on Bald Mountain at Sun Valley Resort in Ketchum, Idaho.

“The people I met, the weather, the place was beautiful,” Ms. Reyes said. “A beautiful experience that I will never forget.”

But Ms. Reyes won’t return to Sun Valley this season, she said, due to President Donald Trump’s June 22 executive order to freeze some federal foreign visa programs – in efforts to promote job opportunities for Americans after unemployment skyrocketed due to the outbreak of COVID-19.

“I really feel bad because I miss Sun Valley so much,” Ms. Reyes said.

About 7,000 international seasonal workers like Ms. Reyes, usually from countries in the Southern Hemisphere, travel to the U.S. every year, making up 5% to 10% of the seasonal workforce at 470 resorts in 37 states, according to estimates from the National Ski Areas Association (NSAA).

With the more limited pool of workers available this year, U.S. ski resorts have been forced to make alternative recruiting plans. And with American consumers showing strong demand to be out on the slopes, the good news is that resorts are seeing an uptick in job applications from young people who don’t need to cross international borders. Some are college students and high school graduates who are deferring school for a year or taking online classes due to the impact of COVID-19.

“We’re still in the early days of our recruiting but we’re liking what we’re seeing,” said Dave Fields, president and general manager of Snowbird Resort in Utah. “People want to work outside in a healthy environment, to be in the mountains.”

Snowbird has had difficulty filling all seasonal positions in past winters, even with about 120 international workers last year, according to Mr. Fields. “That’s not as many as some resorts, but they play a pivotal role in our operations because many are returning year after year,” he said.

This year, he anticipates the resort will be able to hire staff in every position because the resort has received significant interest from locals.

The search for workers

Colleges across the U.S. are ending their in-person fall semesters once students go home for Thanksgiving and finishing their courses online until winter break to limit travel to and from campuses.

That doesn’t mean students are free from schoolwork. But Dave Byrd, NSAA director of risk and regulation, said the extended winter break and flexibility with online classes are contributing to increased interest in working at ski resorts.

“We have ironically and unexpectedly been able to take advantage of college students,” Mr. Byrd said.

In a typical year, international workers include holders of J-1 visas who fill entry-level jobs such as operating lifts, busing in lodge restaurants, maintenance, and other hospitality positions. Others are H-2B visa holders, usually professionals in their field, such as ski instructors or chefs at resorts.

Now that Joe Biden has won the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Mr. Byrd said the NSAA anticipates he will not renew the visa ban – set to expire at the end of 2020 – when he takes office in January 2021.

Several court cases have also challenged the order – the most recent of which on Oct. 1, when a U.S. District Court judge in California suspended the visa ban. There are still barriers standing between ski resorts and their ability to hire international workers in time for this season.

Ryan Huff, communications director at Vail Resorts, which owns 34 resorts in North America, said Vail is not pursuing international workers at this time, and is focusing its hiring efforts in local communities, many of which have shown interest.

A strong season ahead?

The recruiting efforts could help resorts meet what appears to be strong demand.

“Everything that we’re seeing points to a demand for outdoor recreation, also because open air activities tend to have a lower risk of transmission of COVID,” said Adrienne Isaac, director of marketing and communications for NSAA. “That’s huge for your mental and physical health as well, and skiing can offer people that opportunity.”

Ski resorts have new health protocols, such as socially distanced lift lines, reduced capacity in dining locations, and crowd limits on the slopes.

Despite the pandemic, Vail Resorts was able to mention an 18% rise in season pass sales in a September 2020 earnings report, compared with that same time last year. Sales may have increased due to new requirements to purchase passes ahead of time, but some experts still credit the demand to a desire to get outdoors this winter after pandemic lockdowns.

“People are excited to have this ability to have a respite from everything they’ve been dealing with the last several months,” said Mr. Huff at Vail Resorts, which has several of its ski mountains open already.

For Ms. Reyes in Peru, several factors still stand in the way of her ability to work at Sun Valley for another season. For ski resorts, one big uncertainty is a nationwide rise in coronavirus cases, but for now they are hopeful.

“If the public health realities continue to be in their favor – that’s key – we think it could actually be a decent season for them,” said Ms. Isaac of the industry association. “Maybe not a record one but a good one, all things considered.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, we have removed our paywall for all pandemic-related stories.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

America’s new pastime: Police reform

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Despite partisan battles in the United States, plenty of evidence exists that American society is striving to be more democratic and compassionate. One example is the momentum to reform police departments. Ten cities and four counties put 20 police reform measures on the Nov. 3 ballot across eight states. Voters approved all of them. Those initiatives are by no means a complete list of the reforms underway. Local governing councils across the country are taking steps without direct voter initiative.

The efforts include both new and old ideas. In Los Angeles County, Measure J will divert at least 10% of the county’s general fund to “community development” and to alternatives to incarceration. The most popular reform involves closer citizen review of police policies and actions through advisory commissions.

From the streets to the ballot box to city hall, this year has brought overdue scrutiny to American law enforcement. Debates over how officers conduct themselves on the beat should ripen into new partnerships between citizens and police. Reimagining the nature of policing in a just and compassionate society is a project all Americans can serve and protect.

America’s new pastime: Police reform

When a society turns to finger-pointing, which seems to be a pastime in America these days, the rush to blame can obscure progress. Partisan battles over the pandemic, protests over racial injustice, and contested election results portray, to one point of view, a house divided.

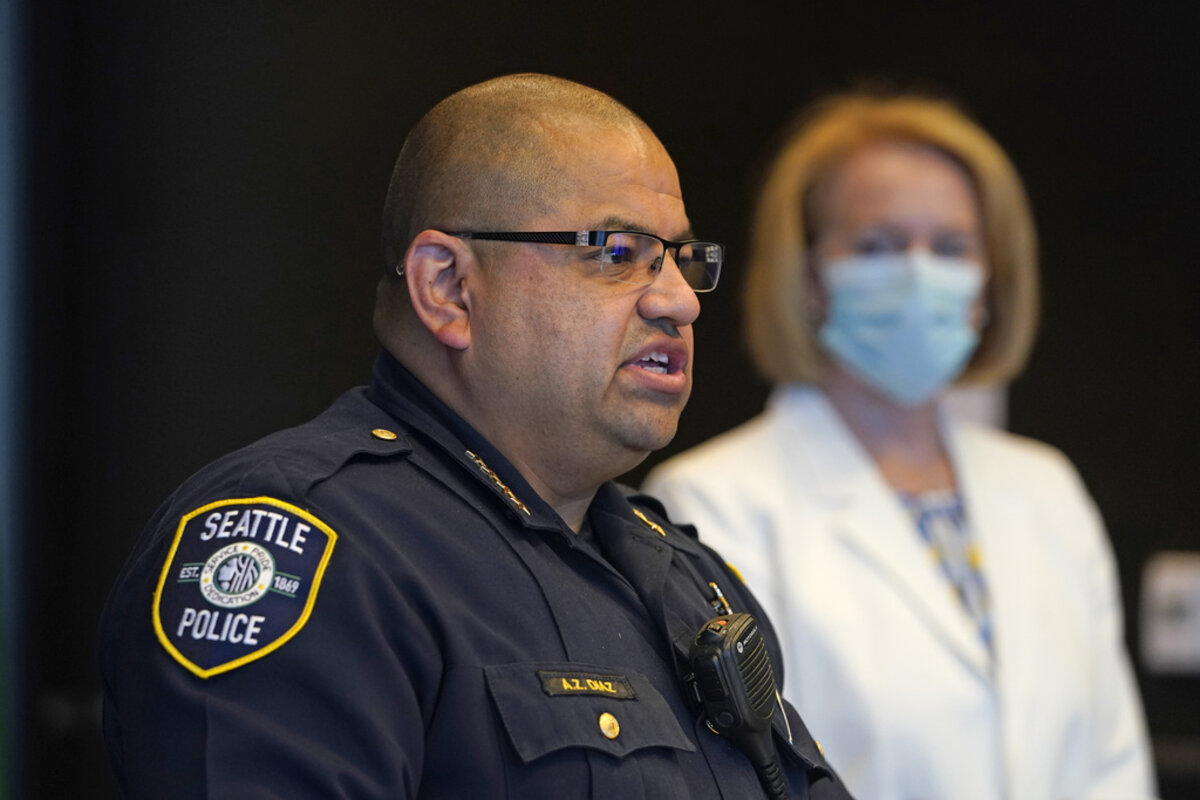

Yet plenty of evidence exists that American society is striving to be more democratic and compassionate. The most obvious example is the diligent effort by local officials and countless volunteers to ensure an orderly, fair, and transparent election. A less apparent but no less significant example is the momentum to reform police departments in order to prevent unjust killings like that of George Floyd last May.

Ten cities and four counties put 20 police reform measures on the Nov. 3 ballot across eight states. Voters approved all of them. Those initiatives are by no means a complete list of the reforms underway. Local governing councils across the country are taking steps without direct voter initiative.

These efforts include both new and old ideas. In Los Angeles County, Measure J will divert at least 10% of the county’s general fund to “community development” and to alternatives to incarceration. In San Francisco, Proposition E will remove mandatory levels for police staffing from the city charter. Other measures around the United States require dash and body cameras for police, ban chokeholds, and rule out “no knock” warrants.

The most popular reform involves closer citizen review of police policies and actions through advisory commissions. Such scrutiny is supported by President-elect Joe Biden. Such commissions are not new. There are more than 150 nationwide. Many serve as a check on the political power of police unions that often lead to the protection of errant officers. There is a growing consensus to make the commissions stronger and more diverse.

Polls show a majority of Americans seek to strengthen rather than “defund” police departments. “For me, it’s about the kind of world we want to leave behind and how policing would look 10 or 20 years from now,” the Rev. Mark Kelly Tyler, a co-director of Power Interfaith in Philadelphia, told Vox News.

His colleague, Bishop Dwayne Royster, is more succinct. “I think the community wants healing,” he told the Los Angeles Times.

The recent videos of fatal encounters between police and civilians have stirred action to reduce an experience far too common for Black citizens. A new space has opened to understand and address the way America’s racial history has shaped policing. Yet just as important is what police face on the streets. In the two weeks since the election, there have been more than 2,500 incidents of violence involving guns, according to the Gun Violence Archive. Of those, 22 resulted in four or more individuals being shot – the definition of a mass shooting. Gun sales have surged over the past year. Just since the election, 15 officers have been shot or killed in the line of duty.

From the streets to the ballot box to city hall, this year has brought overdue scrutiny to American law enforcement. Debates over how officers conduct themselves on the beat should ripen into new partnerships between citizens and police. Demonizing the police is no more productive than demonizing the protesters of police brutality. Reimagining the nature of policing in a just and compassionate society is a project all Americans can serve and protect.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Where does evil come from?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Sandy Sandberg

Questions about evil’s origins are age-old, and Christian Science offers unique and healing answers.

Where does evil come from?

By way of answering the headline’s question let’s look at an analogy. When we enter a room that is dark, we don’t try to figure out why it’s dark. We find the light switch and turn on the light. Nor do we concern ourselves with where the darkness went, because we understand that it didn’t “go” anywhere. It was merely the absence of light.

This analogy works pretty well as a starting point for addressing the question of how Christian Science explains the nature of evil. Instead of trying to figure out where evil came from, Christian Science focuses on understanding the nature of the source of all that is, which is God. Because God is solely good, goodness has a source, but its opposite, evil, lacks a true source or substance – just like the darkness. In the light of Truth, a Bible-based name Christian Science uses for God, the darkness of evil dissolves.

And as we’re receptive to that light, we realize that evil doesn’t have any basis in spiritual reality. We come to understand the nature of Truth as supremely powerful, omnipresent, and entirely good. Therefore its opposite is without legitimacy, without intelligence – a lie. This is captured in one of the ways Jesus described the devil, or evil. He said, “There is no truth in him ... he is a liar, and the father of it” (John 8:44).

This is a startling conclusion if we’re used to relying on the physical senses to tell us what is real and true. But what the material senses do is testify to matter, which is no part of God, infinite Spirit.

It is through spiritual sense (which innately belongs to all of us, as the children of God) that we are able to see and understand the spiritual reality, where all is held in the infinite allness and goodness of God’s being. Referring to God, the Bible puts it this way: “You are of purer eyes than to behold evil, and cannot look on wickedness” (Habakkuk 1:13, New King James Version). Here the absolute purity of God’s nature as conscious of good and good alone is revealed. God, Truth, alone is ever present.

Christ Jesus lived to present this wonderful light of Truth. He once said: “I am the light of the world: he that followeth me shall not walk in darkness, but shall have the light of life” (John 8:12). Indeed, throughout his ministry those who were sick were healed, many entangled in sin were reformed, several people who had died were restored to life, and multitudes who were ignorant of God’s ever present goodness had the gospel – the good news of God’s allness – preached to them.

For instance, there’s an account in Matthew of a person with the skin disease called leprosy who said that Jesus could make him clean if he was willing to do so. The Bible says, “And Jesus put forth his hand, and touched him, saying, I will; be thou clean. And immediately his leprosy was cleansed” (8:3). It was truly remarkable that Jesus touched the man, because in Jesus’ time leprosy was viewed as extremely contagious.

But through the light of Truth, Jesus understood that God, good, alone is in control of His children, made in God’s own image and likeness. He saw the evil called leprosy as the false belief it was: a lie about spiritual reality that could not and did not have the ability to touch or hurt one’s true, spiritual wholeness in any way.

Mary Baker Eddy’s textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” describes how such healing took place. It says: “Jesus beheld in Science the perfect man, who appeared to him where sinning mortal man appears to mortals. In this perfect man the Saviour saw God’s own likeness, and this correct view of man healed the sick” (pp. 476-477).

Today, too, each of us can glimpse the spiritual fact of evil’s unreality, whether in the form of sickness or other obstacles to harmony, and experience healing. That’s what happened to me when I was faced with a frightening urinary blockage (see “Our changeless source of health,” The Christian Science Journal, September 2020).

In this way we are demonstrating what Jesus showed us we could do – we can prove the ever presence and all-power of Truth, whose light is forever shining, dispelling the darkness of evil.

Some more great ideas! To read or listen to an article explaining that one Mind, one God, is the only governing power, please click through to a recent article on www.JSH-Online.com titled, “A prayer for unity.” There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

A study in protest

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We are working on a story about what a drawdown of U.S. troops in Afghanistan could mean for the Afghan people and for negotiations with the Taliban.