- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A light that binds

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

I’ve been thinking a lot about darkness these days. For one thing, it literally comes early now in the Northern Hemisphere. Gone are the gauzy summer sunsets. December nights instead unfurl like a heavy blanket. This year, the arrival of dusk carries a different kind of weight.

A resurgence of the coronavirus has meant that many of the holiday gatherings that typically draw us together in defiance of the December cold and dark have been scaled back or canceled. While public health officials have signaled significant medical progress, they also warn that the next few months may be dark indeed.

So at this moment, where can we turn for a bit of light?

Elie Wiesel was no stranger to darkness. The Romanian-born writer and Nobel laureate was sent to a concentration camp when he was 15 years old. He lost his father, mother, and one sister to the death camps before he was liberated by Allied forces. That time period was so enshrouded in darkness for him that he named his seminal masterpiece chronicling the ordeal “Night.”

But night eventually gives way to dawn.

As an adult, Wiesel was determined to be a light for humanity. He became an advocate for Holocaust remembrance, so that humankind might learn from its past transgressions. He spoke out wherever he saw injustice and suffering, using his stature to take his concerns to heads of state.

He reflected on his life experiences in his 2012 memoir, “Open Heart.” “Even in darkness,” he wrote, “it is possible to create light and encourage compassion.”

We can all carry those words close this winter.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Why traditional retailers have the checkout blues

The pandemic may prove a tipping point for a trend we’re all part of: online shopping. But is everyone ready to give up the entertainment element of retail browsing? Maybe take a pause before going there.

Gustavo Bottan, a baby boomer in Boston, says he’s “never, ever liked shopping.”

“Going to the mall, looking for this or that, I hate that with a passion,” he adds.

For Mr. Bottan, ordering products online is something of a relief. And one thing 2020 has had in spades is online shopping, what with pandemic health concerns and restrictions on face-to-face commerce. We’re still buying stuff, and when it comes to office chairs and web cameras we’re buying more than ever, thanks in part to federal stimulus dollars.

But what about brick-and-mortar stores? The near-term outlook is dire: As many as 25,000 could close this year in the United States, according to Coresight Research. The company expects a quarter of America’s 1,000 malls to close in the next three to five years.

This year’s disruptions will permanently transform the way we shop, much as the advent of department stores did around the time of the Civil War and the adoption of indoor shopping malls after World War II.

The difference is that these shifts enhanced, or at least preserved, the social aspect of shopping. After 2020, will shopping ever again be something we do together?

Why traditional retailers have the checkout blues

Cara Salvatore loves a local corner bodega in Brooklyn, its specialty food items, and the cashiers who work there. But the writer and online entrepreneur rarely goes there anymore because its aisles feel too narrow and cramped to maintain social distance from other people. Instead, Mx. Salvatore’s purchases happen online – for just about everything.

“I don’t love letting somebody else pick what produce I get,” Mx. Salvatore says. Even the writer’s parents in Maryland are grocery shopping online now, “which I never expected. They’re in their 70s!”

It’s a similar story in Tacoma, Washington, for Rick and Sarah Daniel, MBA graduates who are not working as they care for Mr. Daniel’s ailing parents. Men’s deodorant? A click away on Amazon Prime. Bulk household items from Costco? A monthly delivery via Instacart, an online delivery service. The only in-person shopping the couple still does is for fresh food.

The conundrum is the couch.

The Daniels want to get one so they don’t have to rely solely on their antique sofa from the 1800s that needs reupholstering. They’ve looked at new sofas online, but feel uncomfortable buying sight unseen, even with all the fancy 3D imaging on furniture websites. Yet they feel unsafe going into a store to sit on sofas. “We would prefer to wait and shop for that in person, so we can see and touch,” says Ms. Daniel.

Welcome to pandemic shopping 2020, where consumers constrained by health concerns and state and local restrictions on face-to-face commerce have turned most shopping into a sterile contactless experience. We’re still buying stuff, and when it comes to office chairs and web cameras we’re buying more than ever, thanks in part to federal stimulus dollars. And while that stimulus effect is fading, Christmas sales should provide a welcome boost to retailers.

But this year’s festive shopping season will probably not be a “Miracle on 34th Street” for struggling brick-and-mortar retailers as the biggest gains will go to online platforms like Amazon, whose revenues are already up by more than a third this year. While Black Friday online sales surged by nearly a quarter compared to 2019, traffic at physical stores plunged by more than half, according to separate surveys. The near-term outlook for physical stores is dire: As many as 25,000 could close this year in the United States, nearly triple the closures last year, according to Coresight Research, which also expects a quarter of America’s 1,000 malls to close in the next three to five years. Mall stalwarts like J.C. Penney, Neiman Marcus, and Brooks Brothers have all filed for bankruptcy.

The silver lining to all this disruption is that consumers and retailers have been jolted out of their old habits, forcing them to experiment with new ways of shopping. Some of these changes will permanently transform the way we shop, much as the advent of department stores did around the time of the Civil War, the adoption of indoor shopping malls after World War II, and the birth of e-commerce in the 1990s.

The difference is that most of those transformations enhanced, or at least preserved, the social aspect of shopping. In the present era of change, that social aspect has all but evaporated. Everyone agrees that online shopping will get bigger, more efficient, and more streamlined, and that the ease of ordering from home will be irresistible.

But the future of the physical shop, from the big-box outlet near the interstate to the independent home decor store on Main Street, is less clear. Will shopping still be something that we do together, a form of leisure and entertainment? Will it ever become fun again?

***

As a Wall Street retail analyst, Greg Melich spends a lot of time figuring out how and where U.S. consumers are spending their dollars and which companies are best positioned to ring up their sales. He’s tracked the meteoric growth in digital commerce during the pandemic. Take Walmart, the nation’s biggest retailer: Online sales rose 79% in the third quarter.

Still, Mr. Melich reckons that shopping as entertainment will be back, because most of us want to go back to shopping in person when it feels safe to do so again. “I’m not a believer that all retail goes online. ... People are social animals,” he says.

The easing of the COVID-19 pandemic would provide short-term relief for shoppers who want to resume their social habits and indulge in what retail experts call “revenge shopping.”

Ms. Daniel wants to go window-shopping with her mother again; Mr. Daniel wants to browse book and antique stores. “There’s things we’re definitely looking forward to getting back to,” he says.

Even after the pandemic is over, however, four shopping and lifestyle trends will drive the future of retail, according to Mr. Melich, a senior managing director at Evercore ISI, an investment bank. Two of these trends are familiar: online shopping and a hybrid of online and on-site purchases. The other two are more tied to the pandemic and thus more speculative. But they could prove far-reaching in how we live and shop.

One is nesting at home. The other is fleeing density, moving from crowded cities to less-crowded ones or to the suburbs.

Nesting is likely to continue, Mr. Melich believes, because many Americans prefer to spend more time working from home and are also making fewer trips to restaurants and other public forms of entertainment.

As a result they’re spending more on their home, creating a surge in sales for hardware and electronics stores, online furniture retailers like Wayfair, and even small entrepreneurs like Pack Matthews, whose Columbia, Missouri, firm sells office chairs meant to accommodate folks who prefer sitting cross-legged.

When the pandemic hit he fretted that sales would drop for handmade chairs that cost $980 and up. Instead, Mr. Matthews saw sales double. Under a deal he has with Google, he offers chairs at a discount to its employees working from home. The pandemic boom has allowed him to move production from a shared makerspace to a dedicated facility.

“We’re helping folks make the home working environment its healthiest,” he says.

The other trend is less certain. Early evidence points to some residents exiting New York and San Francisco. Other research finds a surge in temporary moves by urbanites who may be moving to less dense locations to wait out the virus. However, should that movement outlast the pandemic, it could parallel the national exodus to newly built suburbs after World War II.

These two trends could end up boosting retail sales. For roughly two decades, consumers have devoted an increasing share of their disposable income to experiences rather than physical items sold in stores. The pandemic has restricted or shut down venues that cram people together, whether it be airlines and restaurants or concert halls and movie theaters. So if we continue to hunker down at home, then more of our disposable income could wind up in the hands of retailers.

That would be fine for Gustavo Bottan, a baby boomer and business development director at Northeastern University in Boston. Since the start of the pandemic, he’s grown wary of crowded spaces like movie theaters and is sticking with his TV for now. “I have a large enough screen that I can kind of feel what [the big-screen experience] is at home.”

Not so fast, says Michael Upton, a software engineer in North Chelmsford, Massachusetts, who graduated from college a year ago. “I definitely would go see movies more than anything,” he says. It’s not just movie theaters that he misses during the pandemic. “The community experiences that we have lost – they’re a big part of human nature that we enjoy doing. Imagine going to an amusement park when nobody’s there.”

***

The challenge for retailers is to understand what kinds of communal shopping experiences will attract consumers in the future. Some are doubling down on online and hybrid options, knowing that even after the pandemic recedes there will be some who prefer to shop that way.

“It’s easier for me to click a few buttons on my phone and get something in two days than to take an Uber to the grocery store,” says Grace Kim, a sophomore at Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. Even buying clothes online has become easier, she says, because sites like Boohoo help customers answer questions about specific brands’ sizes that fit them, the curvature of their hips and belly, and their preferences in loose vs. tight-fitting clothes.

Ms. Kim still likes shopping in person. But in the future, “it would be less frequent.”

On a recent evening, retail consultant David Bishop placed an online order for curbside pickup at a Target store near Chicago. Curbside pickup, once a niche offering, has become a way of life for many pandemic shoppers wary of exposure to the coronavirus inside stores. It has also been a lifeline for retailers that would otherwise have had to shut down during state or local lockdowns.

When Mr. Bishop’s notification came that his order was ready, he clicked on an app saying he was on his way and drove to the store. He parked, and a minute later his order of nearly two dozen grocery items had been brought out to his car. “So it’s almost, like, magical,” he says.

The next day, he worked with another grocer in Minneapolis where the average wait time for a curbside pickup was five minutes. Five minutes may or may not be a long time to wait in a checkout line. But in the competitive world of hybrid shopping, it can feel like an eternity to wait five minutes in your car, especially if you have a young child and you know that other retailers can do the job in a minute.

“At that level, you start getting to a point where a customer can get frustrated,” says Mr. Bishop, who is a partner at Brick Meets Click, a grocery consultancy in Barrington, Illinois.

To pull off curbside “magic,” Target and other retailers are investing heavily in sophisticated geolocation and other technology that lets staffers know when the customer’s car is heading to the store, when it enters the parking lot, and when it’s approaching the pickup area.

Going a step further, Amazon has pioneered cashierless stores, selling meals and snack food in cities like Seattle, Chicago, New York, and San Francisco. When shoppers take an item off the shelf, the system of cameras and sensors automatically charges it to their Amazon account. If they put it back on the shelf, the system credits their account. Once the system scans the Amazon app on the shoppers’ phone, there’s nothing else to scan: no special grocery carts or checkout lines before they leave the store.

Of course, such technologies involve huge investments by multinational corporations, which raise privacy and competitive issues. Location tracking already happens under the radar, but in the hands of big companies it may draw additional government scrutiny. In 2019, Facebook paid a $5 billion fine for deceiving customers about their control over privacy.

A House of Representatives subcommittee recently concluded that Amazon, along with Facebook, Apple, and Google, holds monopoly power. It found that Amazon holds sway over half or more of U.S. online retail sales by dominating the third-party sellers on its site. Amazon argues it isn’t a monopoly and has no incentive to undermine the sellers on its platforms.

Some shoppers are also wary of Amazon’s growing clout. A recent survey of shoppers found that a third believe the company uses questionable practices, though nearly all respondents agreed that the company puts its consumers first.

“I try really hard not to buy from Amazon, because I feel that it’s really hurting our small communities,” says Betsy Morris, a retired baby boomer in Huntington Beach, California. “I always look locally first and if I can’t find it, I’ll go to Amazon.”

***

Just as the pandemic is global, so too are the trends at work in the retail sector. Many of the pressures facing American brick-and-mortar stores are also roiling those in rich countries in Europe and Asia. For hints of what the future may hold, retail experts say, look to China.

That’s partly because Chinese consumers have embraced digital commerce more quickly than Americans have, leapfrogging the mall era to shop on their smartphones. China was also the first to experience the coronavirus and among the first to emerge from it.

“China is now into the new normal, as it were, the first country in the recovery phase of COVID, and it serves as a signpost to the rest of the world,” says Kanaiya Parekh, a Hong Kong-based retail expert for Bain & Co.

Several retail trends in China are recognizable to U.S. retailers: the move from in-store to online sales; growth in spending on health and wellness, everything from fresh fruit to sporting goods; and what Mr. Parekh calls a flight to value. Globally, luxury brand sales are down this year. In China they continue to grow, but cheaper local brands are growing even faster.

Chinese online retailers led by behemoth Alibaba are also trying to make internet shopping fun by livestreaming celebrities selling goods. Livestreaming product demonstrations and celebrity endorsements is nothing new, but China, where nearly 1 in 4 retail sales are done online, has turned it into a juggernaut.

Last year on Nov. 11 – China’s so-called Singles Day for online shopping – retailers sold about $60 billion worth of goods, says Mr. Parekh. That’s more than Amazon sells in an entire month. And livestream sales accounted for 7% of the total. This year on Singles Day, which actually stretched over several days, sales doubled to $120 billion and livestreaming made up 10% of the total.

Livestream companies featured personalities such as Li Jiaqi, China’s “King of Lipstick,” and even retired U.S. basketball legend Earvin “Magic” Johnson, who sold hemp- and cannabidiol-based creams on Alibaba’s Tmall platform.

As in China, U.S. retailers are trying to make the online experience easier, more efficient, and less intimidating, including for personalized items, such as clothing and groceries. Still, many consumers report that the fun is still missing.

Ms. Morris, the retiree in Huntington Beach, still insists on grocery shopping in person. “Honestly, that’s the only social interaction I have. It’s fun,” she says.

It should be even more fun when all the stores are able to reopen, she adds. “It has been like a year that we haven’t gone to a home goods store or a home decor store. We’re all going to go out and say: What is everyone doing? What do houses look like? Is gray out for a paint color?”

Mr. Bottan, the baby boomer in Boston, offers a different perspective. “I have never, ever liked shopping,” he says. “Going to the mall, looking for this or that, I hate that with a passion.” So for him, ordering online for home delivery is something of a relief.

But even he waxes poetic over the hours he’s spent in bookstores like Barnes & Noble. “You have a Starbucks there. You can browse,” he says. “You can go with your kids and read a book. They’re not selling a book; they’re selling an experience.”

***

Mx. Salvatore of Brooklyn, the writer who buys and sells almost exclusively online, sells artsy homemade picture frames at Duskshaped. But they (Mx. Salvatore identifies as nonbinary) dream of opening a physical shop in the future, a place where shoppers can linger and browse.

Online retailers “put all those algorithms in place to try to show you things that you wouldn’t have discovered otherwise,” they say. “But I don’t think it compares to the experience of walking into a store and seeing things you wouldn’t have seen otherwise.”

That’s hardly an old-fashioned view. One of the myths in retail is that because younger customers are comfortable with digital technologies, they’re less interested in shopping in person. In fact, researchers have found that by a wide margin both millennials and the generation born after 1995 prefer brick-and-mortar shopping to buying online.

“I’m not really buying into” online grocery shopping, says Mr. Upton, the software engineer. “There’s something very tactile about food, to see what you’re eating.”

It’s perhaps the melding of physical and online shopping – the hybrid or multichannel category – that could spur some of the biggest retail innovations over the next few years.

For most of history, people could only shop one way: in a physical location. In the 1870s, Montgomery Ward introduced catalog shopping to the general public, a novelty made possible by the crisscrossing of railroads across the continent. In the 1990s, e-commerce emerged on the back of the internet, a technology seeded by military research dollars.

Now in the pandemic era, retailers like Target are working on making ordering online and picking up at the store a seamless process. And that could be just the start. Other hybrid models will emerge, especially as retailers wring delays out of the system, says Kirthi Kalyanam, executive director of the Retail Management Institute at Santa Clara University in California.

Amazon, which already provides free two-day delivery to Prime members, now offers one-day delivery nationwide for a fee and same-day delivery on select items in several cities. Its Amazon Fresh grocery service lets shoppers pick a two- to three-hour time slot for delivery.

Yummy, a hybrid grocer in Los Angeles, is going one better. It now offers to deliver groceries to select LA neighborhoods and suburbs within 30 minutes of an online order. The fee is $6.99 for a minimum order of $14.99 – or free if you spend $125 or more. And in China, several delivery companies are also moving to 30-minute delivery for online orders, says Mr. Parekh.

Stores will increasingly become places to showcase products rather than to stock inventory, says Mr. Kalyanam. Online retailers will re-create their online persona in a physical space: Think Apple stores or Lululemon. And consumers will have multiple ways to buy their goods. Stores might not even carry inventory, but promise to deliver your purchase from a nearby warehouse in a half-hour.

“Fast forward three or four years, you’re going to have ... five, six different big, familiar ways of shopping,” says Mr. Kalyanam. “Shopping as fun will come back, and bricks-and-mortar will be stronger than ever before for shopping as fun.”

Profile

How will a Black Texas GOP chief nurture Trumpism after Trump?

The takeover of the Texas GOP by retired Lt. Col. Allen West – a Black Republican of unbending principles – mirrors President Donald Trump’s takeover of the party at the national level. And it offers a window on how Trumpism can survive the Trump presidency.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

The conservative firebrand newly elected to chair the Texas Republican party, Allen West, is an African American retired Army officer who calls himself “liberals’ worst nightmare.” And he has rebranded the state GOP with the slogan, “We are the storm,” linked to the QAnon conspiracy theory (though the party disputes that connection).

Colonel West’s unbending commitment to conservative principle has become a window on how Trumpism will survive the Trump presidency, say party regulars watching in astonishment as well as grassroots Republicans watching in righteous support.

“Allen West is tailor-made for this moment,” says Fred Wellman, a retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel who is now a senior adviser at the Lincoln Project, a group of Republicans opposing Mr. Trump. “Trumpism rises, and here he is, state chair of a large state.”

The Trump base hopes Colonel West – whose hero, Davy Crockett, is known for his dying last stand – will leverage his rigid conservative ideology to force state leaders to finally fight for their interests and concerns. Those include banning abortion, reinforcing traditional views of sexuality, and cracking down on unauthorized immigrants.

Frustrated grassroots Republicans are "ready for their elected officials to actually deliver conservative results," says Luke Macias, a conservative political strategist. “Chairman West recognizes that and has rightfully [become] an ambassador of the grassroots.”

How will a Black Texas GOP chief nurture Trumpism after Trump?

As dark fell over Taji, Iraq, on an August evening in 2003, Lt. Col. Allen West – angry and afraid – decided to take matters into his own hands.

His battalion had been ambushed several times, and now it had information of another imminent plot to attack them – and an alleged accomplice in custody.

“I came here for two reasons, to get the information I need or to kill you,” Colonel West, his 9 mm pistol drawn and resting on his knee, told the alleged accomplice, according to a U.S. Army investigation of the incident.

But with each denial of knowledge of the plan by the alleged accomplice, local police officer Yehiya Hamoodi, the rumored attack grew more imminent and deadly in Colonel West’s mind. He ordered everyone outside. Minutes later, he was pushing Mr. Hamoodi’s head into a clearing barrel – a sand-filled container used to clear ammunition from weapons. He put the pistol a foot from Mr. Hamoodi’s head and fired a round into the barrel.

“The man inside me probably did want to inflict hurt,” Colonel West told an investigator, “but the soldier and leader just wanted the pertinent intelligence for the safety of my soldiers.”

To this day, the incident – which dislodged faulty information – vexes ethicists and academics. It’s a case study in Army officer training for how to navigate moral gray areas in a war zone. But even when a situation is gray, Colonel West has a penchant for viewing it in black and white.

He wasn’t court-martialed, but the incident brought his Army career to an end – while launching his political career as a conservative cause célèbre for sticking to his principles despite the consequences.

Now, as the new chairman of the Texas Republican party, Colonel West’s unbending commitment to conservative principle has become a window on how Trumpism will survive the Trump presidency, say party regulars watching in astonishment as well as grassroots Republicans watching in righteous support.

A Tea Party forerunner of Trumpian disruption, he criticized the president in 2017 but now backs him to the hilt. Last week, within an hour of the U.S. Supreme Court dismissing a Texas lawsuit challenging President Donald Trump’s election defeat in four states, he blasted the ruling, suggesting that “law-abiding states should bond together and form a Union.” He has critiqued outright calls for secession – “America needs Texas to lead, not secede,” he also said last weekend – but as the Republican Party fractures nationally over Mr. Trump’s election defeat, he is staking a claim to be a vocal, earnest leader of the party’s grassroots Trumpian wing.

“Allen West is tailor-made for this moment,” says Fred Wellman, a retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel who is now a senior adviser at the Lincoln Project, a group of Republicans opposing Mr. Trump.

“His political approach to this day [is] ‘take no prisoners,’” he adds. “He doesn’t work with anyone. He’s constantly making threats. ... Trumpism rises, and here he is, state chair of a large state.”

With a precise high-and-tight military haircut and wire-rimmed spectacles, the conservative warrior presents seriously in measured tones and frequent historical references. But the content of his zero-sum view of politics – as a war between conservatism and “progressive socialism” – fires up restless grassroots Texans more than it does the trustees of the old Bush “compassionate” conservatism.

An African American born in a Blacks-only Atlanta hospital, he grew up in the same neighborhood that decades earlier produced Martin Luther King Jr. But he has called himself “liberals’ worst nightmare” and has rebranded the state GOP with a slogan, “We are the storm,” linked to the QAnon conspiracy theory (though the state party disputes that connection).

His shoot-from-the-hip critiques are aimed equally at “socialist” Democrats and “traitorous” Republicans who would consort with them. And while the majority of Texas Republicans may not share that Manichaean view of U.S. politics, it’s a pillar of the Trump base.

“West wants to say you’re either with us or against us,” says Brandon Rottinghaus, a University of Houston political scientist. “That sends a clear signal that Donald Trump’s influence on American politics continues.”

A Florida “thorn”

Like one of his heroes, Davy Crockett, Colonel West likes to say he’s another Tennessee Volunteer who followed the call to Texas. He graduated from the University of Tennessee before joining the Army, where a glittering 22-year career included tours in the first and second Gulf Wars and a Bronze Star, among other decorations.

Crockett and another of West’s heroes – the Spartan King Leonidas – both perished in heroic last stands, and it’s this angle that best illustrates how Colonel West views his job in Texas and nationally. The political marketplace of ideas is, in his view, more a battlefield of ideas – not a dialogue, or even an argument, but a conflict.

“Right now what we see are two conflicting philosophies of governance, two conflicting ideological agendas,” Colonel West told the Monitor in a September interview. “People are truly ready to get out there and make sure that [conservatives] hold on to Texas.”

A state party chair is supposed to help the party gain or stay in power, but Colonel West has put his personal stamp on the job. Where past chairs kept a low profile, recruiting candidates and keeping party finances healthy, he makes regular appearances at rallies and on cable news.

While he most often rails against Democrats, he’s fueled his rise in Texas by criticizing the state’s Republican leaders for what he calls the “tyranny” of Gov. Greg Abbott’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic: “My criticisms of Governor Abbott have nothing to do with the person. It has everything to do with the fact that we should not be ruled with orders, mandates, edicts, and decrees.”

But in terms of uproar generated, Colonel West’s attacks on the governor pale compared with his November criticism of Dade Phelan, a Republican state representative from East Texas, as “a Republican political traitor” for seeking “affirmation from progressive socialist Democrats.”

State representatives were quick to hit back at Colonel West with one of the most potent political attacks in Texas: not being a true Texan.

“Allen West [needs] to be bought a one-way bus ticket back to Florida,” said Dennis Bonnen, the outgoing Republican House speaker, in a radio interview. “The problem is that I don’t think Florida will take him.”

Colonel West’s approach also runs counter to how the GOP has been able to comfortably hold political power in the state for 25 years, some Texas Republicans say. Making a heroic stand against “progressive socialism” in Texas is all well and good, but the reality is that Republicans have been winning voters just fine already – in part because they have worked with Democrats without compromising their fundamental principles.

“Colonel West is certainly focused on the grassroots perspective of the party,” says Jamie McWright, president of the Associated Republicans of Texas, adding that they need to focus on issues that matter most to all Texans. “If we do, we’ll continue to win.”

While the state GOP as a whole has drifted to the right of the business-friendly, “compassionate” conservatism of the Bush family, it has declined to push the envelope in governing. Bombastic ultraconservatives have always been a feature of Texas politics, says Jim Henson, director of the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas, Austin, but they haven’t been “overly successful.”

“I’m not saying he’s not important or relevant,” he says, but Colonel West “wants to claim a majoritarian status within the Republican Party, and to my mind it’s not clear that that’s true. ... Allen West is a thorn in the side of many people. My suspicion is they’d rather pluck it than support him.”

“All business”

Colleen Stolberg was there at the colonel’s political start in southeast Florida, and it embarrasses her still that she spelled the newcomer’s name wrong – Alan West – on publicity material.

As president of the Broward County Federation of Republican Women, her group was getting tired of cookie-cutter speeches from local candidates. She asked Colonel West to say something different, and he obliged: A talk about the women he served with in the military and the differences they’d faced in the countries he’d served in.

“He had everybody sold,” recalls Ms. Stolberg, who decided on the spot to volunteer for him. “He’s one of those people who will stand up for what he believes in and it doesn’t matter what the consequences are. ... If he ran for president tomorrow, I’d probably work for him again.”

“Not your average politician.” It’s a compliment often heard about Colonel West – and another trait he seems to share with President Trump.

“I’m going up [to Washington, D.C.,] and I’m going to drain that cesspool,” he said at one April 2010 rally, foreshadowing the 45th president. And in his one term in Congress, from 2010 to 2012, he was committed to his ideological mission.

“He was all business,” says Tom Rooney, a former Florida Republican congressman who served with him on the House Armed Services Committee. “On the House floor he’d talk to you about issues, but he wasn’t a back slapper.”

And, he adds, in trying to compromise with some lawmakers on the Hill “you don’t know how to get from Point A to Point B. … You may never get to Point B with Allen, because he’s set in his ways, but at least you know where he stands.”

Southeast Florida was an ideologically diverse area at the time, and Colonel West may have lasted longer in the House save for his consistently favoring principle over compromise. Of 11 bills he sponsored, two passed, neither with Democratic cosponsors.

In Texas, frustrated grassroots Republicans hope his rigid conservative ideology will force state leaders to finally fight for their interests and concerns – like banning abortion, reinforcing traditional views of sexuality, and cracking down on unauthorized immigrants.

“The energy to keep Texas red didn’t come from Texans who want purple government,” says Luke Macias, a conservative political strategist.

“Republicans in Texas are ready for their elected officials to actually deliver conservative results, he adds. "Chairman West recognizes that and has rightfully [become] an ambassador of the grassroots.”

Colonel West would certainly be an earnest ambassador. Had he been willing to compromise on some of his values, he might still be in the Army or Congress. As it stands, with a constituency comprised exclusively of Republicans, he hopes to maintain – and expand – that grassroots base as a new standard-bearer of the Republican Party’s Trumpian wing.

“I would rather be in a position where I could do something to support candidates, where I could do something to support Texas overall,” he says.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify a statement by Jamie McWright, president of the Associated Republicans of Texas, that the party should focus on issues that matter most to all Texans. And the regional name of Mr. West's southeast Florida congressional district has been corrected.

2020’s murder increase is ‘unprecedented.’ But is it a blip?

The spike in murder across the board in the United States defies easy explanation. But getting control of the pandemic looms large on lists of proposed solutions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

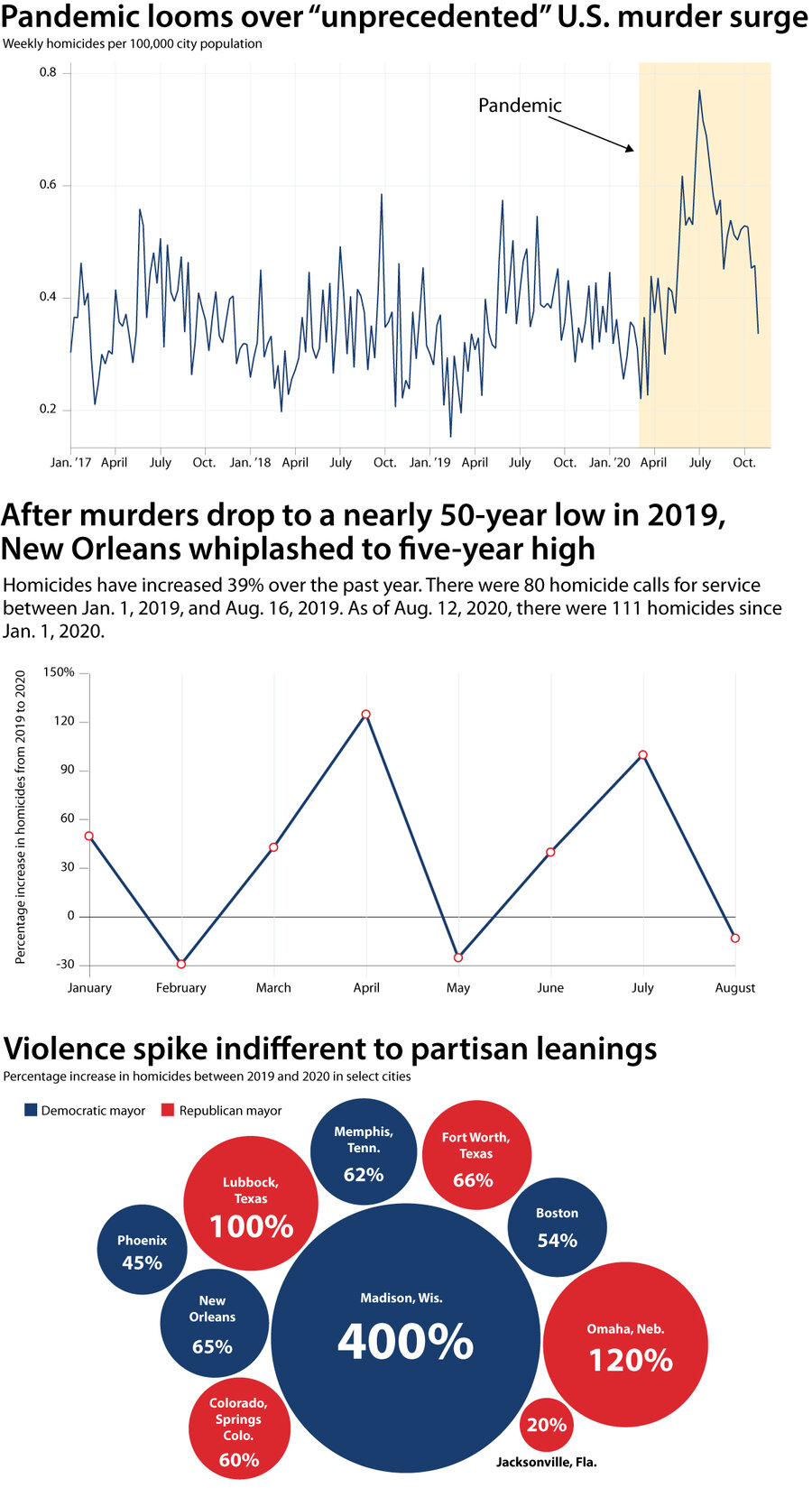

Overall crime has dropped dramatically in the United States since the late 1990s. But the 2020 homicide rate “now exceeds the rates of the late ’80s and ’90s, before the big drop,” says Richard Rosenfeld, lead author of “Pandemic, Social Unrest and Crime in US Cities,” a new report. “This round of crime increase is unprecedented.”

This year, 51 cities across the U.S. saw an average 35% jump in murder from 2019 to 2020 – a “historically awful” development, says New Orleans-based crime analyst Jeff Asher, who crunched those numbers. A different study looking at 21 U.S. cities found 610 more murders in those jurisdictions this year over last year. In those cities, gun assaults increased by 10% over 2019.

Those who want to read partisanship into the trend will be disappointed. Like the pandemic, murder doesn’t discriminate by political affiliation.

“When society’s norms and values are in flux or have disappeared or disintegrated, people don’t know how to behave,” says Kim Davies, a sociologist who studies the dynamics of violent crime. “It’s a kind of normlessness that gives way to ‘Nothing matters.’ [The murder increase] is similar to spikes in suicide when we’ve had economic depressions. But nothing like this has ever happened.”

2020’s murder increase is ‘unprecedented.’ But is it a blip?

After police discovered Huong Nguyen’s body in a car trunk earlier this year in New Orleans East, suspicion fell on her brother.

After being spotted on a surveillance camera walking away from his sister’s car the night she disappeared, Hoa Nguyen has been charged and, if convicted, could spend the rest of his life in prison.

For all its singular tragedy, Ms. Nguyen’s death is part of a tide of gun violence rising from New Orleans to Lubbock, Texas. Coming off a record low in homicides in 2019, New Orleans saw its rate spike by over 50% this year. It is not, by any stretch, an outlier. Lubbock doubled its murder rate, so far, from 2019 to 2020.

To be sure, overall crime has dropped dramatically in the U.S. since the late 1990s. But the 2020 homicide rate “now exceeds the rates of the late ’80s and ’90s, before the big drop,” says Richard Rosenfeld, lead author of “Pandemic, Social Unrest and Crime in US Cities,” a new report. “This round of crime increase is unprecedented.”

This year, 51 cities of various sizes across the U.S. saw an average 35% jump in murder from 2019 to 2020 – a “historically awful” development, says New Orleans-based crime analyst Jeff Asher, who crunched those numbers. A different study looking at 21 U.S. cities found 610 more murders in those jurisdictions this year over last year. In those cities, gun assaults increased by 10% over 2019.

Rosenfeld, Richard, and Ernesto Lopez. 2020. Pandemic, Social Unrest, and Crime in U.S. Cities: November 2020 Update. Washington, D.C.: Council on Criminal Justice (December). Metropolitan Crime Commission. Crimealytics

Those who want to read partisanship into the trend will be disappointed. Like the pandemic, murder doesn’t discriminate by political affiliation: Cities with Democratic mayors are seeing the same increases in lethal violence as cities with Republican mayors.

“We’re seeing it pretty much across the board in places like New Orleans ... but also in smaller places like Omaha, Nebraska, that don’t typically have a lot of murders,” says Mr. Asher. “It’s really not something that’s got a lot of easy explanations.”

Calls for service and arrests in cities like New Orleans have plummeted in a pandemic year, though underreporting could be a factor in those drops.

One nonviolent crime that’s rising is shoplifting. An estimated 54 million Americans are struggling with hunger this year, a nearly 50% rise since 2019. High joblessness, the end of federal pandemic aid, and a relative lack of a safety net in the U.S. are leading to high rates of despair, experts say.

The pandemic’s grating effects and the electorate’s rebuke of a norm-busting presidency have dominated the national psyche. As Americans have bought guns at record rates, some research suggests a causal increase in those weapons being used against others.

The biggest spike in gun violence, notes Mr. Rosenfeld, came in the weeks of social unrest in late spring and summer after George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis.

What’s more, there is evidence that the bulk of the violence is occurring in poorer working class neighborhoods, such as New Orleans East, that have been hit hardest by the pandemic’s economic downturn and the backlash to calls for police reform.

Police activity – or lack of it – “is more likely a symptom of this concept of police legitimacy, where police pull back because people are upset and questioning their legitimacy,” says Mr. Asher in New Orleans. “And when people don’t believe that the police are going to be a natural arbiter, perhaps they’re more likely to take things into their hands – more retribution killings. But ... I’m skeptical that the explanation for why murder is going up everywhere is because police have somehow changed.”

After all, “murder is often mundane,” says Kim Davies, a researcher at Augusta University, usually involving people known to one another, often over insults or resentments fueled by alcohol and other drugs, the use of which have risen during the pandemic.

Interpersonal toxicity, she says, can be exacerbated by more foundational shifts – such as once in a century-level health crisis and a bitter election in which a peaceful transition has come under threat.

“When society’s norms and values are in flux or have disappeared or disintegrated, people don’t know how to behave,” says Ms. Davies, a sociologist who studies the dynamics of violent crime. “It’s a kind of normlessness that gives way to ‘Nothing matters.’ [The murder increase] is similar to spikes in suicide when we’ve had economic depressions. But nothing like this has ever happened.”

That unique dynamic also gives researchers hope that 2020 becomes a statistical anomaly.

“The strategy to reduce violence is, first and foremost, to subdue the pandemic,” says Mr. Rosenfeld, a professor emeritus and criminologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. “The second is to redouble smart policing activity. And the third is to take the essence of police reform seriously, because if police aren’t able to repair the relationship with communities in the cities that have experienced this uptick, I don’t think any crime reductions that might occur from more policing are going to last long.”

Rosenfeld, Richard, and Ernesto Lopez. 2020. Pandemic, Social Unrest, and Crime in U.S. Cities: November 2020 Update. Washington, D.C.: Council on Criminal Justice (December). Metropolitan Crime Commission. Crimealytics

Can the world outdo the Paris accord? Climate summit dreams big.

Scientists agree that the emissions targets set by the Paris Agreement five years ago won’t rescue humanity from catastrophe. A virtual gathering on Saturday aimed to close the “ambition gap.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Five years ago, representatives from nations around the world gathered in Paris and agreed to take drastic measures to curb climate change. For many, it was a moment of unity and hope.

But underlying the Paris Agreement was the understanding that those ambitious plans would not actually achieve the agreed-upon international goal of limiting global warming to an increase of 1.5 degrees Celsius. That goal seemed even less attainable when the U.S., the world’s second largest greenhouse gas emitter after China, dropped out under President Donald Trump.

Still, on Saturday, global leaders gathered once again – this time virtually – for the Climate Ambition Summit 2020 to reaffirm their commitment to the goals set in France half a decade ago and to put forth even more ambitious plans to curb climate change.

“It’s all about putting some more meat on the bone,” says Rachel Cleetus, policy director with the climate and energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. It’s about “the countries not just making aspirational pledges, but backing them up with credible, ambitious policy plans domestically to make sure that they can meet their international commitments.”

Can the world outdo the Paris accord? Climate summit dreams big.

For many, it was a moment of unity and hope. Representatives from nations around the world had gathered in Paris in December 2015 and agreed to take drastic measures to curb climate change.

But lurking behind the Paris Agreement was the understanding that those ambitious plans would not actually achieve the agreed-upon international goal of limiting global warming to an increase of 1.5 degrees Celsius, says Alden Meyer, a senior associate with E3G, a European climate change think tank.

There was an “ambition gap,” he says, so the parties agreed to reconvene and update their goals every five years.

On Saturday, the Paris Agreement’s fifth anniversary, participating global leaders gathered once again – this time virtually – to reaffirm their commitment to the accord and to put forth even bolder plans.

“It’s all about putting some more meat on the bone,” says Rachel Cleetus, policy director with the climate and energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. It’s about “the countries not just making aspirational pledges, but backing them up with credible, ambitious policy plans domestically to make sure that they can meet their international commitments.”

“An important step forward”

The Climate Ambition Summit 2020 indeed delivered more tangible plans to reach lofty goals from many international leaders. But, experts say, there is still work to be done.

“The summit has now sent strong signals that more countries and more businesses are ready to take the bold climate action on which our future security and prosperity depend,” United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres said on Saturday. “Today was an important step forward, but it’s not yet enough. Let’s not forget that we are still on track to an increase of temperature of 3 degrees at least in the end of the century, which would be catastrophic.”

For Saturday’s summit, 71 countries submitted more ambitious national climate plans. Many included significantly more aggressive goals than were outlined in Paris, and 45 focused on benchmarks for 2030. The European Union, for example, has now set higher goals than the ones it agreed to in Paris, promising to reduce net carbon emissions 55% from 1990 levels by 2030, a target that Mr. Meyer calls “a significant step up in ambition.”

Several countries pledged to go net-zero by the middle of the century – or sooner, in many cases. Perhaps most notably, Group of 20 countries like China, Japan, South Korea, the EU, and Argentina have joined that group.

When science meets politics

Since the Paris accord, some countries have taken strides in reducing their emissions. India, for example, has gone from being a growing source of global emissions to being on track to meet international plans to limit warming to 2 degrees Celsius, according to the Climate Action Tracker. The countries that have made notable progress tend to be smaller ones with minimal carbon emissions to start with.

But global carbon emissions have continued to rise, and most of the progress made in the last half a decade is hard to measure.

There has been a move away from coal in much of the West, coinciding with falling costs of renewables, says Dr. Cleetus, making those energy sources competitive with fossil fuels in many parts of the world.

“We know how to do 80% of emissions reduction,” says Katharine Mach, associate professor at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and a lead author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report and the U.S. Fourth National Climate Assessment.

“Technologically we know how to do it, economically, it’s the right choice, the lower cost option,” in more and more places, she says. “That we can get most of the way there, to the super aggressive targets, based on the technologies that exist now, for me, is always very hopeful.”

But this knowledge, she says, isn’t necessarily easy to translate into climate action. There’s politics to contend with.

“Climate models usually have been just physics of how the science works, or in the solutions model space, it’s just straight economics,” she says. “In between the two is how societies actually work.”

A fickle friend

To Michael Mann, professor of atmospheric science at Pennsylvania State University and a lead author on the Observed Climate Variability and Change chapter of the IPCC Third Scientific Assessment Report, “ambition is a close cousin of optimism and hope.”

“Every bit of additional warming does damage, so we can never truly be too ambitious,” he writes in an email. “But we must also recognize the political constraints we’re operating under and work to achieve progress that is possible under those constraints.”

A big concern for Paris Agreement participants and climate change activists is the absence of action from some of the biggest emitters, like Australia and the United States. The U.S. emerged as a leader in climate pledges five years ago, but with the nation pulling out of the agreement under President Donald Trump, that changed sharply.

Now, President-elect Joe Biden, who made climate change a central part of his campaign, has said he plans to rejoin the Paris Agreement. But much of the world is waiting to see what can actually be achieved when he takes office in January.

“The world is painfully aware of the yo-yo nature of American politics” and the partisan split, says Mr. Meyer. “The question people overseas have is, what can the U.S. deliver, given the political tensions?”

Books

Our reviewers’ picks for the best nonfiction of 2020

To understand today’s events, it’s necessary to reach back into history. Explore the life of intrepid explorer Sanmao, how America rewrote its own history, and Abraham Lincoln’s legacy in the best nonfiction titles of 2020.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Monitor reviewers

After a brief slowdown in March due to the pandemic, the stream of books arriving in 2020 gathered force, with nonfiction books emerging stronger than ever. The subjects ranged from biographies of the famous (Abraham Lincoln, Eleanor Roosevelt) and the infamous (Sen. Joseph McCarthy) to reexaminations of race in the United States to the memoir of a Chinese woman who journeyed across the Sahara Desert in the 1970s. The reviewers agree: It’s been a banner year for nonfiction.

Our reviewers’ picks for the best nonfiction of 2020

Curious minds deserve insightful books, and there was no shortage of excellent titles this year. Here is the Monitor’s list of superlative nonfiction books published in 2020, from histories to memoirs and everything in between.

“Caste” by Isabel Wilkerson

In her stirring follow-up to “The Warmth of Other Suns,” Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Isabel Wilkerson persuasively argues that racism alone does not explain America’s social divisions. Rather, the United States ought to be understood as having a race-based caste system, one whose hierarchies, though artificial, are remarkably enduring.

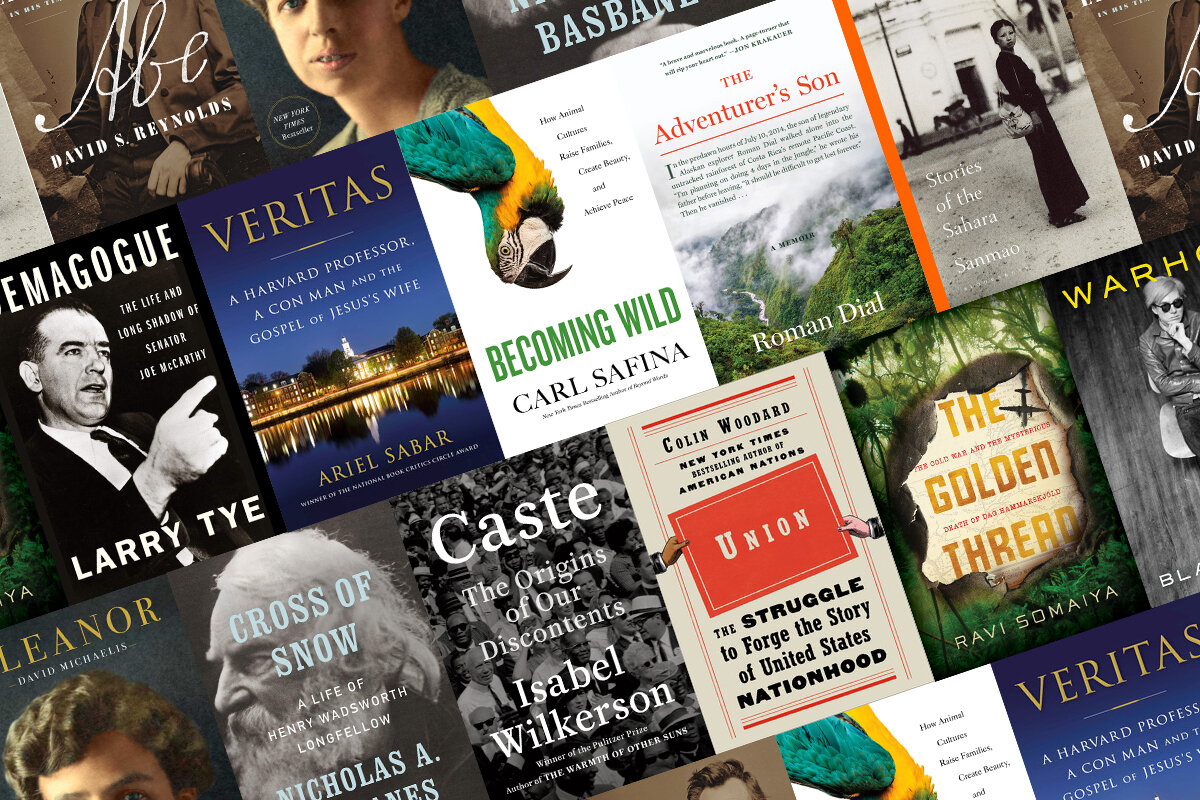

“Demagogue” by Larry Tye

Bestselling biographer Larry Tye writes a long and comprehensive biography of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, the polarizing spearhead of the Red Scare of the 1950s and – Tye contends – the origin of some disturbing features in our 21st-century political landscape.

“Warhol” by Blake Gopnik

“In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes,” Andy Warhol is credited with saying. But there is nothing fleeting about his legacy as an artist, filmmaker, and self-created pop-culture phenomenon. His life and work are examined in detail in Blake Gopnik’s biography. Warhol devotees will rejoice, and more casual readers will receive an education in all things Andy.

“Union” by Colin Woodard

Colin Woodard tells not the story of how America became a nation, but rather of how America crafted its own version of its national history, and how that national mythology has changed over the decades.

“Stories of the Sahara” by Sanmao

As a Chinese woman born in 1943, Sanmao was a pioneering global citizen. These 20 essays about living in one of the harshest areas of the world in the 1970s are testimony to her audacity and courage.

“Just Us” by Claudia Rankine

Claudia Rankine follows her prize-winning “Citizen: An American Lyric” with a brilliant and timely examination of whiteness in America. This consciousness-raising, bravura combination of personal essays, poems, photographs, and cultural commentary works on so many levels and is a skyscraper in the literature on racism.

“Dark Mirror” by Barton Gellman

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Barton Gellman writes an insider account of the breaking of Edward Snowden’s story and its wider implications for the modern world, all told in prose as gripping as a spy thriller.

“Cross of Snow” by Nicholas A. Basbanes

The poems of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow aren’t in fashion today, but in the first major biography of the fabled New England poet in many years, Nicholas A. Basbanes argues that Longfellow is making a comeback. His exhaustively researched account of Longfellow’s career should give that reappraisal a boost.

“Becoming Wild” by Carl Safina

Carl Safina looks at three species – the sperm whale, the scarlet macaw, and the chimpanzee – to chart all the ways they build and sustain their societies. He explores how those cultures echo and differ from our own.

“The Golden Thread” by Ravi Somaiya

U.N. Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld was negotiating an end to the Congolese civil war when he died in a plane crash in 1961. To this day, many believe he was assassinated. Journalist Ravi Somaiya explores one of the most compelling mysteries of the Cold War in this grim and absorbing book.

“Abe” by David S. Reynolds

Abraham Lincoln had less than a year of formal education; he has often been portrayed as inexperienced and unprepared to lead. David S. Reynolds’ monumental, reverential biography rejects that narrative, arguing that Lincoln’s immersion in the high and low culture of 19th-century America, along with his deep moral convictions, equipped him to steer the Union through the Civil War.

“Eleanor” by David Michaelis

This riveting, cinematic biography of America’s longest-serving first lady spans Eleanor Roosevelt’s lonely childhood, her frosty marriage to FDR, their White House years, her intimate relationships outside their marriage, and her widowhood, during which she became an advocate for human rights.

“Veritas” by Ariel Sabar

In 2012, a religion scholar announced a discovery: an ancient papyrus fragment that suggested that Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene may have been married. Expanding on his 2016 article for The Atlantic, Ariel Sabar digs into the story of the papyrus and the couple who tried to pass it off as real.

“The Adventurer’s Son” by Roman Dial

Renowned biologist and explorer Roman Dial searches for his 27-year-old son, who has gone missing in the jungles of Costa Rica. Part memoir, part mystery, “The Adventurer’s Son” is a story of a father’s love – for his son, and for the natural world.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A decade of declaring decency in government

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Ten years ago on Dec. 17, a popular protest broke out in Tunisia against a corrupt regime. It not only felled a dictator and inspired similar revolts in the Arab world, but it also set a model for “smartphone revolutions.” In more than a dozen countries, the uprisings of the past decade have had a similar demand: honest and open governance. On the 10th anniversary of Tunisia’s revolution, it is worth asking: Has this new style of anti-corruption protest achieved much?

The record remains mixed. Yet despite the setbacks or slow change, the protests have shifted attitudes for a generation. “The revolution showed me that everything is possible,” said one young Tunisian woman.

Citizens in countries that saw protests against corruption now realize that a moral revolution displayed on the streets requires the creation of institutional guardrails against greed. Tunisia, for example, is one of the few Arab countries that now allows individuals to present cases of corruption.

The smartphone revolutions remain largely unfinished. But the mental breakthroughs are real. These are evolutions, not momentary episodes. A new generation has seen that good governance is not just an aspiration but an individual right.

A decade of declaring decency in government

Ten years ago on Dec. 17, a popular protest broke out in Tunisia against a corrupt regime. It not only felled a dictator and inspired similar revolts in the Arab world, but it also set a model for “smartphone revolutions,” or bottom-up rebellions driven mainly by young people organized through social media. (The iPhone had been invented only three years earlier.) In more than a dozen countries, from Azerbaijan to Zimbabwe, the uprisings of the past decade have had a similar demand: honest and open governance.

On the 10th anniversary of Tunisia’s revolution, it is worth asking: Has this new style of anti-corruption protest achieved much?

The record remains mixed. In many countries, such as Brazil, Sudan, Algeria, and Armenia, heads of state were forced out. After some protests, the small economic injustices that triggered them – such as hikes in transit fare or a tax on WhatsApp – were resolved. In more than 30 countries, anti-corruption agencies have been set up, although many have been stymied by entrenched elites. In many countries, either an autocrat remains in power or democracy struggles to curb graft. In Zimbabwe, one strongman fell and another took his place.

Despite the setbacks or slow change, the protests have shifted attitudes for a generation. “The revolution showed me that everything is possible,” one young Tunisian woman, Ameni Ghimaji, told Agence France-Presse. In Tunisia, nearly two-thirds of people now “think ordinary people can make a difference in the fight against corruption,” according to Transparency International. And under the country’s new democracy, regular dialogue between political parties is a norm. Yet protests continue, mainly to demand jobs. Corruption is still prevalent.

For change to stick, societies need to be ready when opportunities arise. A new study by the Open Society Foundations on the support needed for anti-corruption reformers notes that “certain political moments create new possibilities for progress.” Such junctures “are triggered by some combination of events. ... Once open, [they] do not last forever; they are temporary shifts in political possibilities.”

Success against corruption has long come in fits and starts. In South Africa, for example, mass protests against corruption in 2017 helped lead to the resignation of President Jacob Zuma. His successor, Cyril Ramaphosa, vowed to rid the ruling African National Congress party of “all bad tendencies.” That effort reached a significant milestone in November when ANC Secretary-General Ace Magashule was charged with 21 counts of fraud, corruption, and money laundering.

Days after the charges were laid, however, President Ramaphosa rebuffed demands by opposition parties to detail his government’s clean-up strategy. Allegations of corruption against ANC figures, he said, were matters to be handled within the party. Mr. Magashule remains in his post and his case has been postponed until next year. Without successful prosecutions and broad legislative reforms, South Africa’s window of opportunity for credible anti-corruption reform is at risk of closing.

One African leader who did make some progress against corruption during her time in office was Liberia’s Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Africa’s first and only elected female leader. She focused on restoring honor to public service. In a recent essay in The Economist, Ms. Sirleaf argued that “political leaders must make government service a realistic, accessible and genuinely prestigious career choice for talented young people. We have to begin with the premise that government can and does work.”

Over the past decade, citizens in countries that saw social media-driven protests against corruption now realize that a moral revolution displayed on the streets requires the creation of institutional guardrails against greed. Tunisia, for example, is one of the few Arab countries that now allows individuals to present cases of corruption and make requests for access to official information in court.

The smartphone revolutions remain largely unfinished. But the mental breakthroughs are real and the course ahead is becoming clearer. These are evolutions, not momentary episodes. A new generation has seen that good governance is not just an aspiration but an individual right.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Keep on singing

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Evan Mehlenbacher

Though ongoing stay-at-home orders may limit our activities, lockdowns can’t stop us from listening for divine inspiration that nurtures productivity, joy, and healing.

Keep on singing

In an effort to help stop the spread of the coronavirus where I live, residents have been instructed to stay home, cancel family gatherings, and not travel or visit others. It’s been a disheartening decree for many to hear, because it’s a repeat of a shutdown we experienced months ago and hoped would never happen again.

But through Christian Science, I’ve found a spiritual perspective that can keep our thought in a good place no matter where our body happens to be. As children of God, we have spiritual consciousness that can never be locked down or isolated by physical circumstances. The source of this spiritual consciousness is the divine Mind, God, not matter. Therefore our thought is always free to soar and sing with inspirations of divine Truth and Love no matter how confining physical conditions may be.

For instance, consider what happened to two biblical apostles, Paul and Silas, when they were thrown into prison for preaching the gospel (see Acts 16:22-26). To ensure they did not escape, the jailers cast the two into the inner dungeon and locked their feet in stocks. A true lockdown!

However, Paul and Silas did not allow their thinking to be imprisoned. They prayed and sang hymns of praise to God. They kept their thought in a state of spiritual uplift inspired by the omnipotence and omnipresence of their Maker. Their prayers were so sincere and heartfelt that the divine power behind them shook the foundations of the prison – literally. An earthquake swung the prison doors open and released the shackles holding Paul and Silas captive. They were free to go.

This story is inspiring because despite the dismal physical circumstances Paul and Silas faced, they did not become despondent and depressed. They understood something of the spiritual reality Jesus taught and demonstrated, in which God, good, alone is in control. And the physical condition imprisoning them dissolved.

Today, in obedience to government authorities, who are doing their best and need our prayers and support, we may find ourselves staying home more than usual, and working or studying alone. But our thinking can still soar and sing with God. Since we are God’s offspring, our identity is fundamentally spiritual. Our true, spiritual consciousness is in God – never confined by stay-at-home orders. We are always free to take in God’s healing inspiration, which transcends physical circumstances.

“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, tells us how to stay free: “The enslavement of man is not legitimate. It will cease when man enters into his heritage of freedom, his God-given dominion over the material senses” (p. 228). If feeling confined, we can affirm our “heritage of freedom” with God, which enables us to realize that nothing can isolate us from inspiration and joy. We do this through our spiritual sense, the ability to know God’s presence and feel divine buoyancy, delight, and joy. Everyone has it.

We don’t need to dread or be enslaved by feelings of isolation and loneliness. We have a God-given ability to put them off with an understanding that we are at one with God, Spirit, and this relation to God can never be held back. Life in God is boundless, free, limitless, inspired. It’s our native state and heritage from God.

This realization empowers us to keep singing and praising God, to keep our lives active and productive, even when things get tough. Stay-at-home orders do not require confining our thinking. We are always free to learn, discover, explore, reason, and gain fresh views of reality that transcend the physical. And this has a comforting, healing impact.

With God, there are no shutdowns or lockdowns. There is the never-ending freedom of Mind to celebrate and enjoy, to express and experience. Thought is always free to soar and sing in the heights of heaven with unfettered wing and ever-ascending views.

Whatever rules for social distancing you may be facing, above all, claim your heritage of freedom, and keep on singing!

Some more great ideas! To hear a podcast discussion about how we can break out of personal biases and tightly-held opinions and move toward unity, please click through to the latest edition of Sentinel Watch on www.JSH-Online.com titled “Are we limiting ourselves by living in our own reality?” There is no paywall for this podcast.

A message of love

Protesting Big Ag

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Tomorrow, we’ll look at American higher education. Is a rethinking of many schools’ dependence on foreign students in order?