- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Impeachment vote: GOP grapples with how to address Capitol violence

- End of yearslong Saudi-Qatar feud reunites families, and a region

- A safe, fair vote? Why pandemic rules fuel concerns in Uganda.

- Why protecting prisons from COVID-19 is everyone's problem

- In a Brooklyn kitchen, a Statue of Liberty spirit offers a fresh start

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

‘A lesson much of the world needs to learn’

Howard LaFranchi

Howard LaFranchi

The other day I read a commentary about this moment, which also brought me back to 1992. Moroccan international expert Ahmed Charai said that events of Jan. 6 had shaken his confidence in the strength of America’s democracy. But he then said he cried when, just hours after the assault on the U.S. Capitol, Congress was back and the sitting vice president read the votes confirming his own loss and his opponent’s victory. That, this writer said, is the America he still believes leads the world by example.

Where does 1992 fit in? I happened to be in Morocco on a reporting trip that year in November, and the U.S. Embassy invited me to an election night party.

First, Bill Clinton’s victory became clear. Later, President George H.W. Bush came on the TV screens with his family. Around me in the ballroom, people were chatting, backs to the screens, like nothing was going on. Then a man near me said something I’ll never forget (and which I wrote about): He turned to his chatty group and said, “Hey, you all need to watch this. The most powerful man on Earth is about to acknowledge his loss, and that he’ll respect the will of the people and leave power quietly. It’s a lesson much of the world needs to learn.”

America has stumbled, no doubt about it. But when Mike Pence read the victorious votes for the Biden-Harris team, it was still an example for parts of the world where such transitions, even frighteningly flawed ones, don’t occur. Remembering that nearly three-decade-old experience gave me some hope.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Impeachment vote: GOP grapples with how to address Capitol violence

Many Republican lawmakers came out strongly against the violent siege on Jan. 6, but most saw impeachment of President Trump as inflaming rather than stifling the passions behind the violence.

How do you stifle a violent strain that has derived encouragement from the president of the United States? That was the dilemma facing GOP lawmakers as the House of Representatives met today to debate and vote on a resolution to impeach President Donald Trump for incitement of an insurrection targeting the peaceful transfer of power on Jan. 6.

Democrats fault Republicans for allowing this violent strain to gain momentum over the past four years, and have called on them to hold President Trump accountable. Ten House Republicans, including their No. 3 – Rep. Liz Cheney – came out in support of impeachment. But many others, while describing Mr. Trump as in a class of his own when it comes to dangerously divisive rhetoric, describe the storming of the Capitol as symptomatic of a much broader national malaise that has also erupted in violence on the left in recent months. They warn that a hasty impeachment without due process risks inflaming the country just days before the Biden inauguration.

“It throws gasoline on the fire,” says Rep. Nancy Mace, a new GOP congresswoman from South Carolina who worked on the 2016 Trump campaign and has been one of the most forceful and unequivocal Republican voices denouncing him since last week’s siege.

Impeachment vote: GOP grapples with how to address Capitol violence

Rep. Nancy Mace, a suburban mom from South Carolina, worked on President Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign, championed his accomplishments over the past four years, and with his endorsement won her inaugural run for Congress this fall.

But just three days after swearing to uphold the Constitution, she swore off Mr. Trump. There is no room for Mr. Trump in the Republican Party after Jan. 6, she said, calling his actions “indefensible.”

Many House Republicans have publicly criticized the president’s role in encouraging supporters to march on the Capitol, where some stormed into Congress as lawmakers were debating whether to object to the Electoral College results showing Joe Biden as the victor.

However, amid intensifying political pressure, concerns about more violence around the inauguration next week, and entrenched partisanship, Republicans remain divided over how best to stifle the violent strain that has emerged on the right.

“I’m holding [Mr. Trump] accountable. The media is holding him accountable. I think history is going to hold him accountable, too,” Representative Mace said outside the House chamber Tuesday night. “But the problem is, he’s only in office for one more week. .... I think [impeachment] throws gasoline on the fire.”

Today, Democrats moved forward with a resolution to impeach Mr. Trump for incitement of an insurrection, including willfully making statements that “encouraged – and foreseeably resulted in – lawless action at the Capitol, such as: ‘if you don’t fight like hell you’re not going to have a country anymore.’”

Ten Republicans, including Rep. Liz Cheney, the third-ranking House Republican and daughter of former Vice President Dick Cheney, joined Democrats in a 232-197 House vote in favor of impeachment. She said President Trump “lit the flame of this attack” and failed to immediately and forcefully intervene to stop it, calling it the greatest betrayal of any U.S. president to his oath to the Constitution.

The New York Times reported Tuesday night that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell also favored impeachment as the most expedient way to exorcise Mr. Trump from the party, raising Democratic hopes of a groundswell of Republican support.

But on Wednesday, Senator McConnell declined to use an emergency provision to bring the Senate back before its scheduled Jan. 19 reconvening, pushing any possibility of an impeachment trial into President-elect Joe Biden’s term, when Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer will take over as majority leader. And over the course of the day, it became clear that Democrats’ hopes of up to two dozen GOP votes in the House were overblown.

The small number of Republicans openly supporting impeachment likely reflected a variety of factors, from the political cost – both from fellow lawmakers as well as from Mr. Trump’s base – to security concerns. Rep. Jim Jordan of Ohio has already called for replacing Representative Cheney as chair of the GOP House caucus and Republican House members said privately that they worried voting for impeachment could physically endanger them and their families.

Rep. Jason Crow, a Colorado Democrat and former Army Ranger, told MSNBC his Republican colleagues are “paralyzed by fear,” adding that last night “a couple of them broke down in tears ... saying that they are afraid for their lives if they vote for this impeachment.” Even before the most recent violence, death threats against members of Congress were on the rise, targeting Democrats as well.

The FBI has warned of armed protests in Washington, as well as in all 50 state capitals ahead of and on Inauguration Day, Jan. 20.

A much broader malaise

Democrats have criticized Republicans for allowing this violent strain to gain momentum over the past four years, describing them as too eager to tap into Mr. Trump’s popularity for the sake of their own ambitions – or at least unwilling to jeopardize their political fortunes by crossing him.

But many Republicans describe the violence that erupted on Jan. 6 as symptomatic of a much broader malaise in America, in which distrust in government has soared on both sides of the political spectrum, fueled by increasingly partisan rhetoric and deadlock that prevent Congress from effectively serving the people.

“I think the summer of violence, as well as what happened on Jan. 6, are really symptoms of a much bigger problem and we’ve got to address it,” says Rep. Ken Buck, a Colorado Republican who spearheaded a letter to President-elect Biden calling an 11th-hour impeachment “as unnecessary as it is inflammatory” and calling on him to urge Speaker Nancy Pelosi to refrain from pursuing it. “I think we have to recognize that the rhetoric that’s used from politicians, myself included, gets people fired up and we’ve got to do our best to be more understanding of each other’s bases and supporters and make sure we’re focused on policy and not personality.”

While describing Mr. Trump as in a class of his own when it comes to dangerously divisive rhetoric, many House Republicans have called out Democrats for tolerating violence on the left around racial injustice protests in recent months, as many businesses were looted or burned, causing damage that could exceed the $1.4 billion cost (in 2020 dollars) of the 1992 Rodney King riots.

Democrats decry such “both-sides-ism,” saying that the cause of racial justice is hardly analogous to disrupting the peaceful transfer of power.

GOP Rep. Thomas Massie of Kentucky, who along with Representative Mace signed a letter opposing the Electoral College objections of his GOP colleagues last week as well as the letter to Mr. Biden, says Congress has misdiagnosed the threat, erroneously labeling a wide swath of regular Americans as “domestic terrorists.”

“Instead of trying to fix the underlying problem of Jan. 6 – which is, people don’t trust our government – we’re hunkering down here and calling in reinforcements,” says Representative Massie outside the House chamber, as hundreds of National Guard members patrolled a newly erected security fence outside the Capitol. “And I think it could escalate. Somebody needs to de-escalate.”

Many of Mr. Trump’s supporters appear to be genuinely convinced that the election was stolen from the president amid a rapid scale-up of mail-in voting, despite numerous Trump-appointed judges and GOP election officials debunking the president’s claims and declaring that they saw no evidence of widespread election fraud. A portion of these supporters see themselves as engaged in a valiant revolution against a tyrannical partnership between Mr. Biden, the left, and Big Tech. They have drawn parallels between their actions and the American Revolution of 1776 against the British crown.

Mr. Trump urged his supporters to march on the Capitol as Congress was meeting in a joint session overseen by Vice President Mike Pence to count the Electoral College votes. By some accounts, some of them were prepared to die for the cause. Ashli Babbitt, an unarmed U.S. Air Force veteran, was fatally shot while trying to climb through a broken pane to the Speaker’s Lobby, just outside the House chamber. Others took in the scene from a distance.

“I think people who just care about their country were sent here on an impossible mission, on a suicide mission,” says Representative Massie. “There was no way for them to overturn the election, but they were led into thinking that if they came here, there was a way to overturn the election.”

“Snap” impeachment

Few Republicans are defending Mr. Trump’s rhetoric or actions on Jan. 6. But some questioned whether they constitute impeachable offenses, and many expressed concern that a snap impeachment would set a dangerous precedent for the future.

“Honestly, while I think he bears considerable responsibility, the president deserves his day in court, too,” says Rep. Tom Cole of Oklahoma, the ranking Republican member of the House Rules Committee. “It’s the first time I’ve ever seen an impeachment where the president doesn’t have any representation at all.”

Many Republicans had favored a censure vote rather than impeachment, which had the potential to get far more GOP support.

Representative Cole, who during this morning’s proceedings expressed support and respect for his Democratic counterpart, Chairman James McGovern of Massachusetts, says the way forward involves rebuilding a more constructive political culture.

“I think all of us have to take a much more responsible tone,” he says. “The president’s been a big part of that, but I think it goes well beyond him.”

“You know what I would do?” asks Representative Buck, standing outside an entrance to the House chamber and pointing inside. “I would lock everybody in that chamber and I wouldn’t let anybody out until we figured out how do we want to start talking to each other.”

“There was a time when members lived in D.C., their kids played sports together, and they attended sporting events, and their spouses socialized together,” he adds. “Now ... we all run back to our districts and we get bombarded with a particular message ... and we come back here energized to do things that are really more partisan than they were at another point in time in our history.

“And I think there are a lot of things we can do, if we sat down and looked at it,” he says. “Throwing impeachment on the floor is not one of those things. This is not a healing move.”

End of yearslong Saudi-Qatar feud reunites families, and a region

What price political principles? When the Saudis punished Qatar for its policies, it came at a personal and economic cost for residents of the whole region. Reconciliation and cooperation are now in the offing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In 2017, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates initiated a blockade against Persian Gulf neighbor Qatar for its support for Islamist movements, the influence of its Al Jazeera network, and its perceived closeness to Iran. Travel to and from Qatar was banned, the country’s only land border was blocked, and Qatari flights were barred from Gulf airspace.

Now, 3 1/2 years after a fracture that did little more than divide citizens and hurt economies, Gulf Arab reconciliation is ushering in a renewed appreciation for regional cooperation.

Perhaps the fastest positive from an agreement signed last week in Al Ula, Saudi Arabia, was the emotional reunification of families separated by the blockade. But the region is already moving forward on economic cooperation and the fight against COVID-19.

Some analysts caution that many hurdles remain on the path to the political and military integration envisioned by the Al Ula pact.

“The whole idea of regional integration is that you work on a lower level, build confidence and trust, and work higher to the political level,” says Abdullah Baabood, an Omani analyst. “I am cautiously optimistic now that due to the crises of COVID-19 and oil prices we will start to see serious, concrete action.”

End of yearslong Saudi-Qatar feud reunites families, and a region

Feuding royals hugging, music videos celebrating “brotherhood” on national television – the pomp and ceremony of Saudi Arabia and Qatar’s reconciliation, which ended a blockade that divided the Arab world, was as schmaltzy as it was momentous.

In 2017, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates initiated a blockade against Persian Gulf neighbor Qatar for its support for Islamist movements during the Arab Spring, the influence of its oft-critical Al Jazeera network, and its perceived closeness to Iran.

Travel to and from Qatar was banned, the country’s only land border was blocked, and Qatari flights were barred from Gulf airspace. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi even threatened to instigate a coup, forcing Qatar to build a new alliance with Turkey.

Now, 3 1/2 years after a fracture that did little more than divide citizens and hurt economies, Gulf Arab reconciliation is ushering in a renewed appreciation for, and reliance on, regional cooperation.

While observers debate how much the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) reconciliation pact signed last week at a summit in Al Ula, Saudi Arabia, was pure PR, Gulf citizens who were told by state media for years to turn against each other have been instantly reconnected.

Overnight, borders reopened and flights resumed.

Family reunions

There was a sense of palpable joy from divided families and friends in a tribal region that is perhaps more connected by blood and trade than any other regional bloc.

Gulf media were full of stories of daughters reunited with their parents, grandparents meeting their grandchildren for the first time.

“The most affected party from the blockade were the people of the GCC, and those who will most feel the benefits of this blockade ending are GCC citizens,” says Najah Al Otaibi, a London-based Saudi analyst.

Single tribes stretch from the tip of Oman up to Kuwait, and families woven by decades of intermarriage among citizens of Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE were suddenly divided when Riyadh and Abu Dhabi imposed the 2017 blockade.

The renewed appreciation for cooperation even extends to the much-maligned Gulf Cooperation Council.

“When the GCC came to life four decades ago, it made travel easy, it helped to reconnect these families and tribes divided by the borders of the nation-state,” says Abdullah Baabood, an Omani analyst and visiting professor at Waseda University.

“These connections don’t suddenly go away in a blockade or political divisions. This reconciliation is a return to normal.”

Confronting the pandemic

Another area impacted by the deal, brokered in part by Jared Kushner as the Trump administration wound up its Mideast diplomacy, is public health.

In their reconciliation announcement, Gulf leaders established the Gulf Center for Disease Prevention and Control to coordinate efforts in combating COVID-19 and potential future pandemics.

Aside from a much-publicized Zoom call of all Gulf health ministers in March 2020, insiders and observers say there had been minimal coronavirus coordination among Gulf states.

This is despite that, within the Arab world, the Gulf has been hit especially hard. Its combined population of 55 million people has recorded 1 million cases and 10,000 deaths.

The center, in coordination with Gulf health ministries, will assist in vaccine rollout, information-sharing, and research concerning COVID-19 and other infectious diseases.

“This reconciliation agreement injects hope into the idea of regional economic integration and cooperation,” says Giorgio Cafiero of Gulf State Analytics, a Washington, D.C.-based consulting firm, cautioning that political divisions nevertheless remain. “We can see some positive and significant changes in the struggle against COVID-19.”

Economic integration

The GCC’s reconciliation declaration also called for the activation of the much-delayed common Gulf market and a customs union to set uniform trade policy, tariffs, and a single point of entry for Gulf imports.

Observers and citizens say even the most basic steps toward economic integration would alleviate pressures on oil-reliant Gulf states desperate to diversify and privatize their state-run economies amid a pandemic.

One year on from the crash in oil prices, oil only last week reached the $50 per barrel mark and remains well below $60, the fiscal break-even point for every Gulf state save for Qatar.

Gulf states are all looking for ways to keep businesses afloat while facing budget deficits of 12%-20% of gross domestic product one year after paying out a combined $97 billion in bailouts to private sector and semiprivate sector businesses in 2020.

“The impact of the pandemic was positive in the sense that Gulf states realized that the Gulf is stronger when they are united, and they have to be united as we are all facing a common challenge,” says Dr. Otaibi, the Saudi analyst.

Another boost by the rapprochement is in the realm of sports and entertainment.

With Qatar set to host soccer’s World Cup in 2022, the end of the blockade will not only allow for easier logistics for teams and fans to reach Doha, but also let other Gulf states to entice visitors to see the sights in their countries.

Lingering divisions

But questions remain whether greater cooperation and shared economic and health threats can paper over ideological divisions. Observers caution that deep-seated differences remain between Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE despite the televised hugs.

Crucially, the reconciliation agreement did not address Doha’s support for Islamist movements in the region, which the UAE views as a threat to its own stability and was a stated reason for the 2017 blockade.

Nor did the agreement address Qatar’s alliance with Turkey and its deepening economic reliance on Iran – both partnerships it strengthened due to the blockade.

Meanwhile, Oman and Kuwait do not share Saudi Arabia’s view of Iran as an imminent threat to be neutralized, but rather as a neighbor with whom Gulf states must normalize peaceful ties.

Other observers say such differences make the Al Ula pact’s goals of a “joint defense agreement” and “military integration” unrealistic, for now.

“You can’t move to the final stage of political unity when you don’t have economic unity or a common market,” says Mr. Baabood, the Omani analyst.

“The whole idea of regional integration is that you work on a lower level, build confidence and trust, and work higher to the political level. I am cautiously optimistic now that due to the crises of COVID-19 and oil prices we will start to see serious, concrete action.”

Healing bruised feelings

Hopes are high the deal will cool the polarization fueled by state-run media, talking heads, and social media influencers, all of which were used by governments to attack one another and peddle conspiracy theories.

Previously, UAE-backed media personalities called for the overthrow of the Qatari emir and accused Doha of terrorism, while Qatari networks denounced the UAE as waging a war on democracy, and promoted rumors of Saudi royal family feuds, murder plots, and insurrections.

As the deal was signed, Gulf satellite networks suddenly broadcasted music videos of Gulf citizens singing together and holding hands. Saudi state networks brought on analysts citing the need for Gulf diplomacy and “brotherly” ties with Qatar. Qatar’s Al Jazeera played travel agency, posting clips hailing the beauty of Abu Dhabi , Riyadh, and Al Ula.

Although Gulf media are now falling in line with the decisions of princes and kings, observers question when and if the vitriol and fevered nationalism fed to their publics the past four years will dissipate.

“Governments of these countries can sign an agreement, but that doesn’t mean the Qataris are going to forget what happened to them, or the public forget what was said in the media on a daily basis,” says Mr. Cafiero, of Gulf State Analytics.

“You cannot go 100 miles per hour in one direction, press a button, and suddenly be back where you started.”

“Injuries have occurred on both sides and there are bruises,” Mr. Baabood says. “But over time these bruises will heal.”

A safe, fair vote? Why pandemic rules fuel concerns in Uganda.

Around the globe, pandemic restrictions have sometimes served as pretext for repression. Elections raise especially urgent issues of how to protect a fair vote, while also protecting voters.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

In Uganda, like much of the world, the line between protecting people’s health and upholding their rights has often been a blurry one during the pandemic. And in Uganda, that has played into the hands of the country’s 76-year-old president, Yoweri Museveni, who is running for a sixth term in Thursday’s election.

The president has used the pandemic to limit campaign rallies and other get-out-the-vote events, while the crisis has helped him argue the country needs firm, stable, and familiar leadership.

“I think for many people it’s difficult to tell government is enforcing lockdown restrictions to protect people’s health and when it’s spilled over into violence to protect the people in power,” says Eshban Kwesiga of Chapter Four Uganda, an organization promoting democracy and civil liberties.

With campaign events limited, and radio and TV largely controlled by the government and its allies, many opposition politicians have attempted to take their campaigns online. But on Tuesday, President Museveni announced a ban on social media.

“They see that the largest voting bloc is accessible online, and that the era of mass rallies to build support is over,” says Mr. Kwesiga, noting that the average Ugandan is 19 years old.

“The pandemic,” he says, “has just accelerated that.”

A safe, fair vote? Why pandemic rules fuel concerns in Uganda.

When Uganda’s main opposition candidate for president, Bobi Wine, was shoved into a police van during a campaign rally in the eastern part of the country in mid-November, the scene was in many ways familiar.

Since he became an opposition member of parliament in 2017, Mr. Wine – whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi – has often been the target of violent intimidation by security forces. In 2018, he was allegedly severely beaten and tortured in police custody, and later sought medical treatment in the United States. During his campaign for president, he and his supporters have been regularly shot at, tear-gassed, and arrested.

But his supposed crime, this time around, was a new one. He was arrested for violating COVID-19 social distancing guidelines, which prohibited campaign rallies of more than 200 people. In the days that followed, police and security forces killed more than 50 people protesting Mr. Wine being detained.

In Uganda, like much of the world, the line between protecting people’s health and upholding their rights has often been a blurry one during the pandemic. And in Uganda, that has played into the hands of the country’s 76-year-old president, Yoweri Museveni, who is running for a sixth term in Thursday’s election.

“The pandemic has given leverage to Museveni to tighten his grip on power,” says Eric Mwine-Mugaju, a Ugandan journalist and political commentator. The president has used the pandemic to limit campaign rallies and other get-out-the-vote events, and the crisis has helped him make the case that the country needs firm, stable, and familiar leadership.

“I think for many people it’s difficult to tell government is enforcing lockdown restrictions to protect people’s health and when it’s spilled over into violence to protect the people in power,” says Eshban Kwesiga, head of development and policy at Chapter Four Uganda, an organization promoting democracy and civil liberties.

The Ugandan government, indeed, was initially praised for its brisk response to the pandemic in March and April. A strict lockdown quickly contained the virus’ early spread to a trickle. But many in and outside the country sounded alarms about its heavy-handed enforcement. By the time Uganda confirmed its first death from COVID-19, about a dozen people had reportedly been killed by police. To date, the country of more than 40 million has confirmed about 38,000 cases and more than 300 deaths.

“Despite the violence being meted out, people didn’t actually have any doubt about the existence of the virus or its danger like in some other countries,” says Mr. Mwine-Mugaju, who also notes that Mr. Museveni’s government has a long track record of successfully fighting serious disease outbreaks, including Ebola and AIDS. “So that really helped Museveni because when he spoke about limiting movement and rallies to stop the virus, people believed it.”

Restrictions on campaigning have also helped Mr. Museveni open a lead by forcing candidates to campaign on radio and TV, which are largely controlled by government and its allies.

“The president can easily say he needs to speak to the nation under the pretext of talking about the coronavirus response, and then use that airtime to advance his political agenda,” Mr. Kwesiga says.

Many Ugandan opposition leaders, chief among them Mr. Wine, have also attempted to take their campaigns online. (The singer-turned-politician has 1 million followers on Twitter.) When Mr. Wine was arrested in November, his campaign livestreamed the leader being pushed into a police van.

“We are not slaves!” he shouted as the doors of the police vehicle slammed shut behind him.

Last week, campaign staff filmed Mr. Wine being surrounded by police and shot at with tear gas and rubber bullets as he gave a press conference in his car.

Such seemingly unfiltered access to political events as they are unfolding can have a powerful effect on voters, experts say.

“Increasingly we can see that the state recognizes and is concerned by the role that social media play in our elections,” Mr. Kwesiga says, noting that the average Ugandan is 19, and more than two-thirds of registered voters are under 30. “They see that the largest voting bloc is accessible online, and that the era of mass rallies to build support is over.”

“The pandemic,” he notes, “has just accelerated that.”

On Tuesday evening, as election day closed in, Mr. Museveni announced a ban on social media, explaining that the move was in response to Facebook removing several pro-government accounts from its site in the preceding days.

“We cannot tolerate this arrogance of anybody coming to decide for us who is good and who is bad,” he explained on live television.

But as Ugandans prepare to vote, many say they are concerned that the politicization of the pandemic has distracted from the fact that COVID-19 remains a major public health concern.

“Whether Museveni wins or Bobi Wine does, we need a healthy population to carry on after election day,” says Anne Abaho, a lecturer in international relations at Nkumba University in Entebbe. “The main concern should be keeping people safe, regardless of how they vote.”

Graphic

Why protecting prisons from COVID-19 is everyone's problem

Understanding how the coronavirus threatens the lives of prisoners and prison officers is crucial to combating its spread and to safeguarding incarcerated people.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

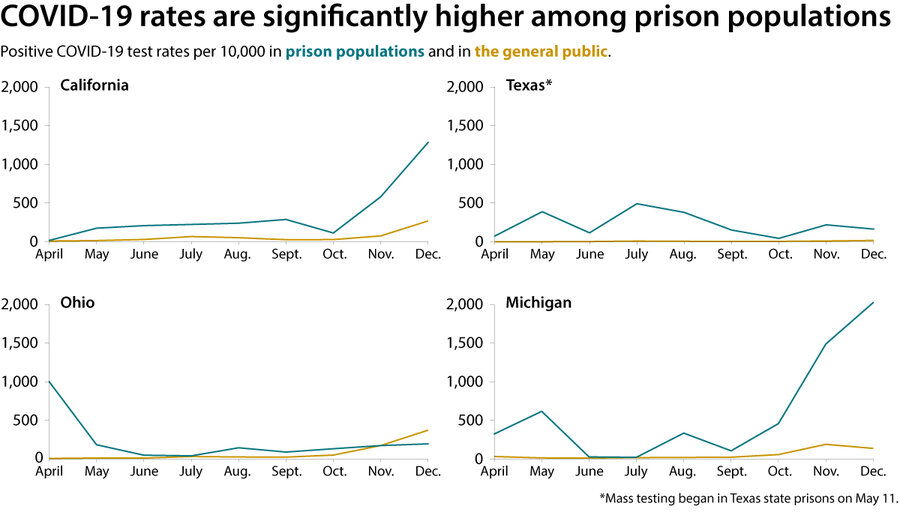

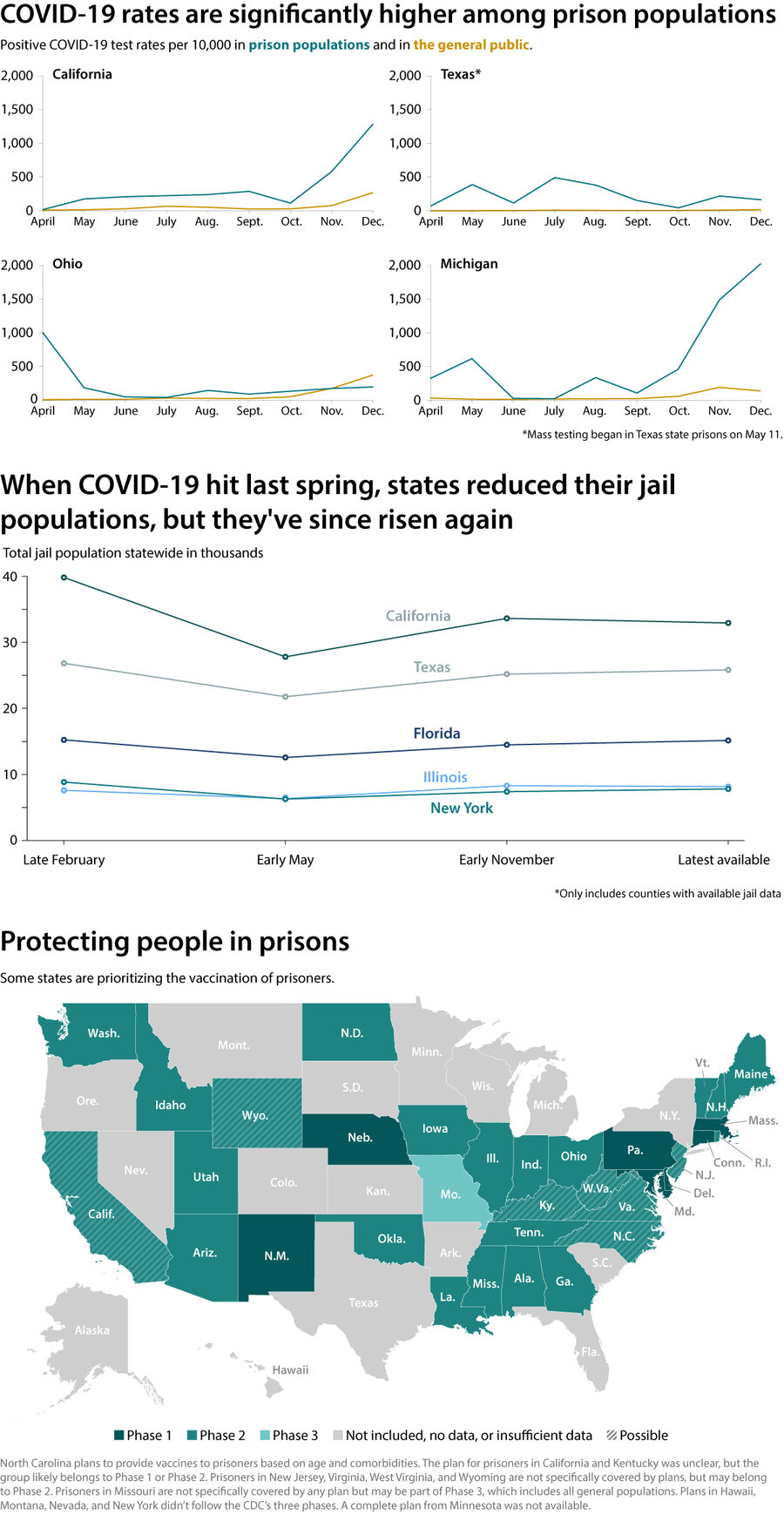

More than 329,000 COVID-19 cases have been recorded in U.S. prisons and jails since the pandemic began, highlighting the risks posed to incarcerated men and women and, in turn, to the general population to which inmates eventually return.

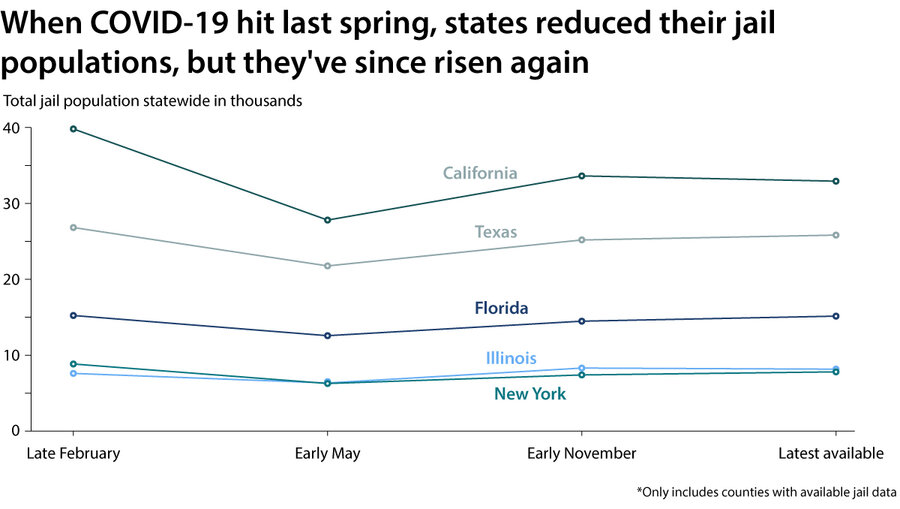

Last spring, some states tried to reduce the risk by depopulating jails. Medical protocols were also overhauled to get treatment to those sickened by the virus. Since then, however, prison populations have begun rising again. At the same time, prison guards complain of the strain on their ranks from exposure to the disease.

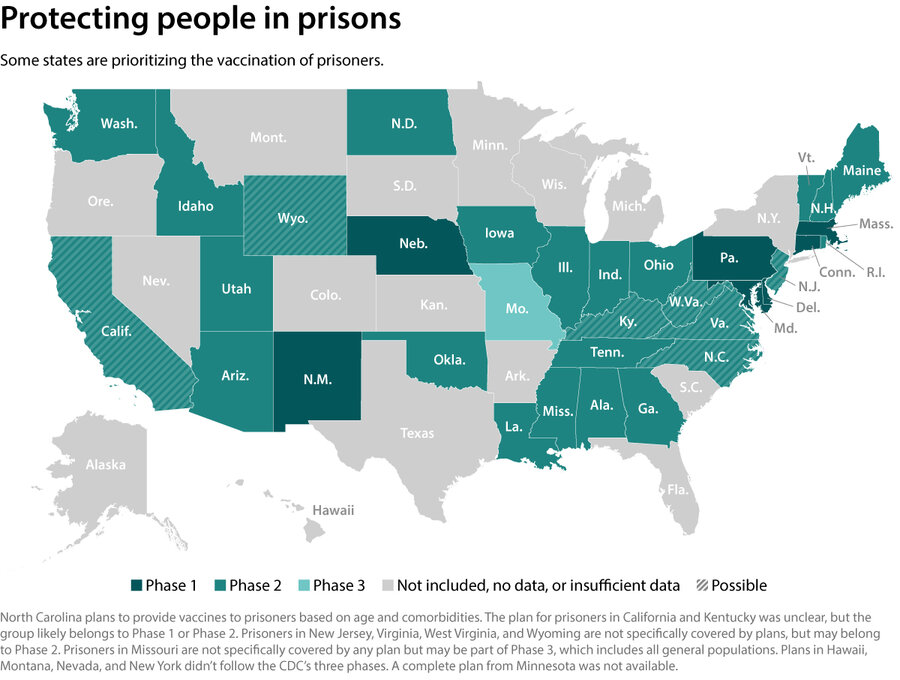

As vaccines become available in prisons, the risk should diminish, but only if inmates accept vaccination programs, says Homer Venters, a doctor who served in New York’s jails. Should they refuse to vaccinate, this would complicate U.S. efforts to contain the coronavirus, so it’s important to build trust. If not, he warns of “a series of slow-rolling disasters.”

Why protecting prisons from COVID-19 is everyone's problem

The COVID-19 pandemic that has devastated the United States has raged with particular ferocity inside prisons and jails. Such facilities are characterized by poor sanitation and health care, and house large concentrations of high-risk individuals; social distancing is nearly impossible.

Among the country’s roughly 2.3 million prisoners, there have been at least 329,000 reported COVID-19 cases behind bars, taking the lives of at least 2,020, according to data tracked by The Marshall Project and The Associated Press – rates that far exceed the non-prison population. By comparison, 380,000 have died in the U.S. overall.

The Marshall Project, Associated Press

The health care system behind bars was “deeply flawed” even before the pandemic, says Homer Venters, former chief medical officer for New York City’s jails.

“There wasn’t a lot of evidence-based access to [medical] care to begin with, so when outbreaks hit many of these facilities people were left to fend for themselves,” he says.

Some states have been doing better than others, says Michele Deitch, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin who studies how jails and prisons are run. But generally speaking, “the biggest [health] recommendations have really not been implemented adequately.”

What does work in reducing the risk of spreading COVID-19, say analysts, is depopulating prisons and jails. And while some states did this at the start of the pandemic, prison populations have been ticking back up recently, and so long as that’s the case, says Professor Deitch, “there’s a limit to how much [other] precautions can work.”

Vera Institute of Justice

For corrections officers potentially exposed to the disease, the pandemic has exacerbated long-standing issues over staffing, training, and pay.

Annual line-of-duty deaths for corrections officers typically number about a dozen. Since March 2020, 115 officers have died from COVID-19 alone, according to Brian Dawe, national director of One Voice United, an advocacy group for corrections officers. (That doesn’t include officer suicides, which were already occurring at a much higher rate than the general population.)

“We’ve got guys and gals doing double shifts day after day after day … who’ve slept in their cars and in their RVs because they were afraid to go to their families,” says Mr. Dawe. “The strain and stress on them, it’s unfathomable.”

Corrections facilities have also contributed to the pandemic outside their walls.

In a report last month, the Prison Policy Institute, a nonprofit research and advocacy group, analyzed the density of incarcerated populations and the increase in pandemic caseloads in that area. It estimates that mass incarceration was responsible for an additional 500,000 cases over the summer.

Prisonpolicy.org

How corrections systems manage the virus moving forward will be a significant factor in when the pandemic ends here, and how the criminal justice system could be reformed afterward.

For now, vaccination plans for correctional facilities need to be grounded in programs that successfully build trust with incarcerated people, says Dr. Venters, author of “Life and Death in Rikers Island.”

“If the same person bringing you a vaccine is the same person that took you to solitary confinement, or turned a blind eye to your abuse, there would be a tendency to not trust them,” he says.

And until COVID-19 is less prevalent behind bars, the pandemic won’t truly be over in the U.S. no matter how widely vaccines are distributed.

“There would be, a year from now, a series of slow-rolling disasters,” Dr. Venters says, “if we don’t do a good job engaging with people who are incarcerated about taking the vaccine.”

On a positive note, the pandemic could accelerate justice reform. Some jurisdictions are considering making permanent decarceration policies implemented during the pandemic, Reuters reports.

And generally, the pandemic “has created more [public] awareness about the problems inside prisons and jails,” says Professor Deitch. “That does give me hope.”

The Marshall Project, Associated Press

Difference-maker

In a Brooklyn kitchen, a Statue of Liberty spirit offers a fresh start

In the training kitchen at Emma’s Torch, refugees earn more than culinary skills. They begin to carve their own path to the American dream.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

“Give me your tired, your poor” is just one line of the famous poem that Kerry Brodie took to heart to create her nonprofit – a program that readies refugees for jobs in the food industry.

Ms. Brodie had worked for a civil rights group, volunteered at a homeless shelter, and had her immigrant great-grandparents in mind when she founded Emma’s Torch. A reference to both the poet, Emma Lazarus, and the Statue of Liberty, its culinary classes are complemented with lessons in job readiness and personal development. Emma’s Torch also aids graduates with job placement.

The organization has made adjustments during the pandemic, holding smaller classes but still serving a takeout menu featuring fare infused with flavors from its students’ varied backgrounds.

Fanta Sylla’s December graduation had her prepare a fresh salad and coconut flan for the incoming class. Ms. Sylla had worked as a humanitarian in Ivory Coast, and in 2017 the asylum-seeker arrived in the U.S. alone. She found family at Emma’s Torch, she says. “I’m happy to be here. I started a new life, and I’m proud of that.”

In a Brooklyn kitchen, a Statue of Liberty spirit offers a fresh start

One fall morning in a white-walled Brooklyn bistro, a chef folds his arms into wings and flaps.

“Chicken, duck, turkey – these are all examples of poultry!” says chef Alexander Harris, drawing out the last word.

The culinary director is used to patiently pantomiming vocabulary and other kitchen terms for students learning English. In today’s lesson on moist-heat cooking methods, his red marker fills a whiteboard with words like “simmer” and “sous vide.” A student snaps a photo on his phone before the canvas is cleared.

Mr. Harris’ three aproned pupils sit attentively, binders open, spaced apart at steel-top tables. They hail from the countries of Georgia, Dominican Republic, and Ivory Coast, but are all carving out fresh starts in New York. United by their kitchen uniform, they nod in understanding beneath black baseball caps and masks.

They become the new batch of graduates from Emma’s Torch today.

Doubling as an eatery, the nonprofit trains asylum-seekers, refugees, and human trafficking survivors for culinary careers – and pays them to learn.

In a city where most restaurant workers are immigrants, entering the industry can mean a first step toward financial security for newcomers with limited English.

Moreover, the Biden administration’s pledge to increase U.S. refugee admissions – from the current 15,000 annual cap to 125,000 – highlights the need for social enterprises like Emma’s Torch. The nonprofit has helped launch the new lives of over 100 students with an ethos as warm as the bistro’s butter-thick air.

“My work is not charity,” says founder Kerry Brodie. “It’s really about trying to give other people the access to those opportunities, and make sure that they feel supported in pursuing them.”

She named her nonprofit for the Jewish poet Emma Lazarus, whose 1883 lines “Give me your tired, your poor / Your huddled masses / yearning to breathe free” grace the Statue of Liberty pedestal. The sentiment echoes in Ms. Brodie’s family history. Her great-grandparents emigrated from Lithuania to South Africa during World War II – the only members of their immediate families to survive the Holocaust.

“Nuts idea”

Working at the LGBTQ civil rights organization Human Rights Campaign in Washington until 2016, Ms. Brodie watched as the global population of displaced persons swelled to over 65 million – surpassing World War II numbers. Underscoring the implications of this global trend for her was the now-iconic image of Alan Kurdi, the Syrian boy who drowned along with two other family members in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, Ms. Brodie was spending a couple of mornings a week volunteering at a homeless shelter. As she handed out muffins, she recalls bonding with the women she served over food memories; Ms. Brodie learned to cook from women in her own family.

These experiences helped marinate her idea for Emma’s Torch. Over a dinner in 2015, Ms. Brodie’s husband brought up her “nuts idea,” she says: “He offhand said to me ... ‘Someone should do it – why not you?’ And I think that that was the very scary aha moment.”

She started culinary school in New York City in 2016, then launched the nonprofit’s first apprenticeship after graduation a year later. Emma’s Torch added a restaurant in the Carroll Gardens neighborhood in 2018, followed by cafe space at a local library.

From over 40 countries, participants range widely in life experience and age. Culinary classes are complemented with lessons in job readiness and personal development, like interview prep, résumé help, and life-coping skills. Emma’s Torch also aids graduates with job placement to ensure good matches.

“We’re really looking for people who are ready and willing to start to make that change in their life,” says Mr. Harris.

Students graduate ready to impress.

“The one thing that always blew me away was the work ethic,” says Jennifer Nelson, managing partner at Buttermilk Channel, which has hired a couple of alumni.

Diligent job-placement efforts appear to pay off. The nonprofit reports that 97% of its 100-plus alumni have landed jobs within three months of graduation.

“Emma’s Torch is like the foundation to help us [become] confident,” says Thu Pham, who started as a line cook after graduation in 2018 and now works as a private chef.

When Ms. Pham arrived in the United States from Vietnam in 2016, she left behind a nonprofit career helping disadvantaged children. Starting life from scratch in a new country, she had difficulty landing a job.

Ms. Pham learned about Emma’s Torch through a refugee organization. She always loved cooking for family and friends, she says, and was “overwhelmed” when her application was accepted. The most challenging part was learning English along with the vocabulary of cuisine – with the help of Google Translate. She laughs when trying to explain which pan is a “hotel pan.”

Ms. Pham had hoped to sell her hot-sauce-drizzled, rice crust Vietnamese pizza at a food market, but the pandemic botched her plans. All the more, she says she valued the virtual classes Emma’s Torch extended to alumni during life under lockdown – especially on starting a business.

“That’s very useful information, especially for me,” says Ms. Pham, who still aspires to a venture of her own.

The organization is piloting an entrepreneurial track to equip recent graduates for leadership roles.

Pandemic pivot

In-person operations shut down in March. Without diners, the nonprofit that had operated on 55% earned revenue from the restaurant took a financial hit.

Donations from community members and past funders were a bright spot.

“Every time a gift-card order came through, it was a reminder that people know we’re going to get through this,” says Ms. Brodie. A federal Paycheck Protection Program loan has also offered reprieve.

The shutdown intensified the nonprofit’s focus on helping its network. Every morsel of leftover food was distributed to students and alumni “so they wouldn’t go hungry,” Ms. Brodie says.

With the apprenticeship on pause, trainees no longer received $15-an-hour wages. Emma’s Torch reports helping 77 students and alumni file for unemployment.

After careful planning, Emma’s Torch reopened its cafe for takeout in November. The menu still features American fare infused with students’ backgrounds, like black-eyed pea hummus and shakshuka sandwiches. The school also rebooted with smaller cohorts to respect social distancing. Heightened attention to safety is routine, with hourly cleaning of high-touch surfaces and regular hand-washing.

“We talk to our students constantly about the idea that each of us are ambassadors of public health,” says Ms. Brodie.

Graduation is typically a lively event involving guest chefs. Scaled back due to COVID-19, Fanta Sylla’s December graduation had her prepare a fresh salad and coconut flan for the incoming class.

Ms. Sylla had worked as a humanitarian in Ivory Coast. The asylum-seeker came to the U.S. in 2017 alone, but says she found family at Emma’s Torch. On a break from baking buttermilk biscuits, she says, “I’m happy to be here. I started a new life, and I’m proud of that.”

Ms. Sylla particularly liked learning the art of customer service, and says she hopes to divide her time between food and psychology careers. She’ll miss the kitchen’s people, with whom she shared “family meals” in the afternoon.

“It’s a beautiful school – it’s a family,” she says.

Learn more about Emma’s Torch at www.emmastorch.org.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Argentina’s embrace of equality for women

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Argentina embarked this week on a dramatic process of redemption. It is dropping all criminal charges and annulling all convictions against women who either terminated or lost their pregnancies. The move follows passage last month of a landmark bill legalizing abortion. It is expected to become law within days, making Argentina only the third country in Latin America to give women full control over their reproductive decisions.

The new law reflects shifting priorities and attitudes across Latin America coinciding with the growing role of women in government and civic affairs. It also affirms that women have been at the forefront of social movements in Latin America for decades. In Argentina, 42% of senators and 39% of deputies (serving in the lower legislative chamber) are women.

In societies where women have long been seen more as symbols of “the stability and continuity of the race,” as the Mexican writer Octavio Paz put it, than as individuals in their own right, Argentina has signaled a profound shift. Through a recognition of the dignity and worth of women, democracy is being renewed.

Argentina’s embrace of equality for women

Argentina embarked this week on a dramatic process of redemption. It is dropping all criminal charges and annulling all convictions against women who either terminated or lost their pregnancies. The move follows passage last month of a landmark bill legalizing abortion. It is expected to become law within days, making Argentina only the third country in Latin America to give women full control over their reproductive decisions.

The new law reflects shifting priorities and attitudes across Latin America coinciding with the growing role of women in government and civic affairs. When he proposed the abortion bill, President Alberto Fernández acknowledged “a dilemma”: “The criminalization of abortion is of no use. It has only allowed abortions to occur clandestinely in troubling numbers.” But his motives were more than pragmatic. The government, he argued, had an obligation to care for all its citizens regardless of their personal decisions.

The new law is catching up to an often-unrecognized reality: Women have been at the forefront of social movements in Latin America for decades. During the last military regime in Argentina, from 1976 to 1983, women whose husbands and children disappeared at the hands of the state formed a protest movement that radically transformed traditional attitudes toward women and motherhood. “To be a mother became more than caring for and educating children,” noted Cecília Sardenberg at the Federal University of Bahia in Brazil. “It also meant defending their rights.”

That ideal endures in the social movements led by women in Latin America today. In 2012, for example, Camila Vallejo led university students in Chile in protests of government funding of education. She is now a member of Congress. In Argentina, 42% of senators and 39% of deputies (serving in the lower legislative chamber) are women. In Bolivia, women make up 52% of parliament. Mexico last year made gender parity a requirement in all three branches of government.

It is unclear how many women in Argentina will benefit from the decision to drop criminal punishment for terminated pregnancies. But even partial numbers indicate the extent of the harm done. Since 2012, when the last reforms were enacted, allowing abortion only in cases of rape or when the woman’s life was endangered, an estimated 38,000 illegal abortions have been performed annually. According to a study by the Center for Legal and Social Studies (CELS) in Buenos Aires published last month, more than 1,500 women in 12 of 23 provinces faced criminal liability in some form for losing a pregnancy through either abortion or miscarriage.

The cost of strict abortion bans in Latin America is severe. In Argentina alone, an estimated 3,000 died of unsafe procedures since 1983. Poor women were disproportionately affected. As the CELS study notes, women suffering from the effects of bad procedures were often turned away by medical professionals. Even women who suffered miscarriages were subject to prison, abuse, and stigmatization.

Explaining her vote in favor of the bill, Sen. Nora del Valle Giménez said, “I choose to see the thousands of young people who are calling on us to pass this law and join in the consolidation of democracy – who demand ... to participate in the construction of a country with less exclusion, more equality, and more rights.”

In societies where women have long been seen more as symbols of “the stability and continuity of the race,” as the Mexican writer Octavio Paz put it, than as individuals in their own right, Argentina has signaled a profound shift. Through a recognition of the dignity and worth of women, democracy is being renewed.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A ‘divine law career’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Thomas Mitchinson

An avid student of political science, a young man was certain his future would include a law career and possibly public service. But the more he learned about Christian Science, the more he was drawn to practicing a different kind of law – God’s healing law of goodness.

A ‘divine law career’

Growing up, I always thought I would be an attorney, possibly with a career in public service. I wanted to make a difference in the lives of others. I loved reading about various politicians and Supreme Court justices, and admired some of them greatly. In college, I majored in political science and planned on attending law school.

During these years, I was also gaining a great love for Christian Science. A history class I took asked students to make a list of great people throughout history. I found myself thinking, “The greatest man in history, the one I should emulate, is Christ Jesus.” This was quite a revelation to me, and caught me off guard.

What would happen to my law career? I wondered. Then one day I found this passage in the book of Psalms in the Bible: “O how love I thy law! it is my meditation all the day” (119:97).

I knew then that the practice of God’s law, as taught and demonstrated by Christ Jesus and illuminated in the textbook of Christian Science – “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy – would be my career. I would be a Christian healer, a Christian Science practitioner. In her book “Rudimental Divine Science,” Mrs. Eddy defined Christian Science this way: “As the law of God, the law of good, interpreting and demonstrating the divine Principle and rule of universal harmony” (p. 1).

While I was still in college, every spare minute I had was spent studying Christian Science. After my homework was done, I would study the Bible and Science and Health. During breaks at work, I would read testimonies of healing from The Christian Science Journal and Sentinel. I couldn’t get enough! During this time I also took Primary class instruction with a teacher of Christian Science.

One day there was an opening in an office shared by several Christian Science practitioners. They needed someone to share the rent and take a shift in the office one morning a week. I felt that was my opening into the public practice of Christian Science and signed up.

For over a year, no one called asking for my help, but I loved the quiet time studying Christian Science and growing in my confidence in God’s healing power. After college, I worked in sales full time, but always kept hours in that practitioner office. Gradually, calls for prayer came in, and healings resulted.

I must admit I struggled with pride during this time. Many people couldn’t understand what I was doing and felt I was underemployed. A former professor of mine admonished me to get into law school before I regretted my career path. Friends were already established in high-paying jobs while I was sometimes struggling to make ends meet.

But I was learning the importance of gaining an understanding of my closeness to God, and striving to live a spiritually based life. As my Christian Science practice grew, I asked my employer at the sales job if I could work on a part-time basis. He agreed. After about a year, I felt confident enough in the path I was taking to let the sales job go. When I explained this to my employer, he stated that he thought that was foolish and would not let me go. I was stunned, but admired this man and kept working for him, while praying about my next steps.

A few months later, I received a call from my employer’s wife. She was a student of Christian Science. She said that my employer had been awakened in the middle of the night with acute pain in his hip. The condition was worsening. He was not a student of Christian Science and had always relied on medicine in the past, but he decided to ask me for Christian Science treatment.

We prayed together, and in a few days, the pain disappeared completely. My employer was very grateful, and stated that now he understood why I was choosing this new career. Soon I left his employ, with his blessing.

That was 35 years ago. In the intervening years, I’ve realized that my “divine law career” has been a great public service, making a difference in the lives of other people. I’ve seen divine law heal diseases and problems of every kind. And my financial needs have always been met.

I am so grateful for a career in which we can help those oppressed by fear, sin, and disease to find their freedom through Christian Science, the law of God.

Adapted from an article published in the Sept. 27, 2010, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Some more great ideas! To read an interview from the archives of the weekly Christian Science Sentinel on healing racism titled “An Interview: on racial prejudice,” please click through to www.JSH-Online.com. There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

Braving the Russian cold

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, our stories will include a look at a security risk exposed by the mob who stormed the U.S. Capitol last week: that extreme views on politics and race reach into the ranks of police officers and government workers.