- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Should a bullying comedy routine be illegal? Canada’s high court may decide.

- Biden wants to beat China. Beijing says, bring it on.

- Breaking grass ceilings: Why more women are coaching men's teams

- ‘Ground zero’ for voting rights. How Georgia’s new law fits with its past.

- Neighbors feeding neighbors: Community fridges strengthen ties

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Covering the bases: What women offer men’s sports

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

As a teacher, one of my least favorite phrases was “those who can’t, teach.” It implies educators must have washed out of the real world.

One of today’s stories puts that adage in a new, almost subversive, light. We meet Justine Siegal, who dreamed as a girl of playing professional baseball. She never got to test that dream because of her gender. Instead, she became the first female coach in Major League Baseball.

That women are making inroads into men’s professional teams may seem curious. After all, women have their own leagues. But, from youth sports up through the pros, women’s sports are consistently undervalued by society.

That second-tier status was on display during the NCAA championship, when Ali Kershner, a sports performance coach for Stanford University, posted shots of the weight room for the men’s teams and the single rack of barbells available to the women’s teams. The posts went viral, and the NCAA responded with a fully stocked weight room and an apology.

I have encountered similar double standards as an assistant amateur boxing coach with USA Boxing. When a fighter I worked with won the New England Golden Gloves, we were told she would need to fundraise to pay both her way and her coaches’ to nationals in Florida. Had she been a male fighter, there would have been travel funding.

Why does this matter?

The world of sports is both a reflection and a driver of cultural trends. Seemingly small changes, like Sarah Thomas taking the field to referee the 2021 Super Bowl, send ripples of broader movement across society.

Professional sports is one of the few arenas that holds the attention of people from pretty much all walks of life. And fans love nothing more than watching people shatter the expectations of what is thought to be possible.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Should a bullying comedy routine be illegal? Canada’s high court may decide.

Protecting the right to free speech is critical. So too is preserving human dignity. What happens when they are mutually exclusive, as in a case currently being decided by the Supreme Court of Canada?

Jérémy Gabriel was diagnosed at birth with Treacher Collins syndrome, which affected his facial structure and ability to hear. But after multiple surgeries, he learned to sing and achieved local fame. In Quebec he needed no introduction; he was “Le Petit Jérémy.”

In 2010, Mike Ward, a stand-up comic, took aim at Quebec’s “sacred cows,” including Le Petit Jérémy, in his routines. He said that when he found out the child wasn’t dying, he tried to kill him. The bit, while mean, especially when heard today, was popular with audiences.

For Mr. Gabriel, it was deeply upsetting – so much so that he took Mr. Ward to court. Now the Supreme Court of Canada must decide whether Mr. Ward’s routine discriminated against Mr. Gabriel, or whether it was a protected expression of Mr. Ward’s artistic freedom.

For those who are rallying behind Mr. Ward, including comedians and free speech advocates, many say they don’t like the routine. But they say courts should not be deciding the legality of comedy.

For Mr. Gabriel’s family and many supporters, including human rights and disability advocates, this is more than an offensive joke. It is repeated speech that attacks an individual because of his disability.

Should a bullying comedy routine be illegal? Canada’s high court may decide.

Listening to the joke now, in 2021, can be shocking.

He’s called ugly. The stand-up comic pokes fun at his hearing aid. The “he” in question was a 13-year-old boy named Jérémy Gabriel who has a disability. The comedian Mike Ward says that when he found out the child wasn’t dying, he tried to kill him.

Back then, in 2010, audiences roared. The bit was part of a popular routine attacking the “sacred cows” of Quebec society, including Mr. Gabriel, who was born deaf but against the odds learned to sing and became a Quebec sensation.

And now the Supreme Court of Canada must decide whether the routine discriminated against Mr. Gabriel, or whether it was a protected expression of Mr. Ward’s artistic freedom.

For those who are rallying behind Mr. Ward, including comedians and free speech advocates, many say they don’t necessarily like the joke. They wouldn’t tell it themselves. But they say the courts should not be deciding the legality of comedy routines.

For Mr. Gabriel’s family and many supporters, including human rights workers and disability advocates, this is more than an offensive joke. It is repeated speech that attacks an individual because of his disability.

The court must balance these rights at a time when social mores and public tolerances toward what we can laugh about are quickly evolving.

“The joke”

Mr. Gabriel was diagnosed at birth with Treacher Collins syndrome, which affected his facial structure and ability to hear. He underwent multiple surgeries and, with the help of an anchored hearing aid, learned to sing, gracing the stage as a 9-year-old with Celine Dion and even performing for the pope. In Quebec he needed no introduction; he was “Le Petit Jérémy.”

“The joke,” as it’s often called, may have entailed perfect comic timing for its howling audience, but it came at the worst possible time for the object of it. Mr. Gabriel had just started his first year of high school. It was hard enough to make new friends; students started calling him ugly in the hallways.

His parents urged him not to watch the replays of the adult-only shows available over the internet. But one day he flicked on his screen and listened to the two-minute segment that built up to Mr. Ward saying he tried to drown Mr. Gabriel at a water park when he found out he wasn’t terminally ill. “I thought it was not real. And then the people started laughing really, really hard,” Mr. Gabriel says. “And then I started to cry for the first time.”

Mr. Ward, on a circuit tour from 2010 to 2013, told that routine more than 200 times.

“He did not attack the fact that I was famous,” says Mr. Gabriel, now a university student in Quebec City. “He targeted the disability directly.”

Mr. Ward declined, through his manager, to be interviewed. But comedians have stood behind Mr. Ward, who’s known for his dark and edgy humor and took home comedian of the year in Quebec in 2016 and 2019. They say the joke has been taken out of context. It was part of a social commentary – pushing the boundaries as the best comedy does – about why it’s taboo to critique the icons of Quebec like Ms. Dion or Le Petit Jérémy.

Derek Seguin, an improvisational comic in Montreal, says his friend’s intent was never to injure Mr. Gabriel. “If you’re sitting in the room, you could feel that it’s not mean,” he says. “He’s a master of what he does. It was really, ‘Let’s play with this idea that people are often scared to play with.’”

In fact, Mr. Ward’s lawyer said in the Supreme Court hearing in February that by mocking Mr. Gabriel, his client had been treating him as an equal. “Come on, don’t go that far,” Justice Russell Brown responded. “We’re not talking about Galileo or Salman Rushdie.”

But Mr. Seguin says it’s not an absurd argument. At his own shows, sometimes he has audience members in wheelchairs. When he has teased them – “good way to get a front-row seat,” he’ll joke – they have approached him with thanks afterward. “They’ll say, ‘Usually people won’t look at me, or I’ll catch them looking at me and they’ll just look away. Thanks for just talking to me like a person.’”

Expression vs. dignity

The case has been touted as a high-stakes battle between freedom of expression and protection of dignity against discrimination.

The Gabriel family brought their complaint to the Quebec Human Rights and Youth Rights Commission in 2012. Four years later the province’s Human Rights Tribunal, which hears cases on discrimination and harassment, sided with the family. It ordered Mr. Ward to pay $42,000 (Canadian; U.S.$33,000) in total to both Mr. Gabriel and his mother. Mr. Ward appealed, and in 2019 the decision was upheld – although not in the case of Mr. Gabriel’s mother – at the Quebec Court of Appeal. He has appealed to the Supreme Court, which is expected to decide the case within a few months.

The case itself applies narrowly to Quebec, as it questions the balance of rights protected by the province’s charter of human rights and freedoms, and whether the tribunal had a place wading into a free speech debate. But, depending on how broadly the justices base their decision, the general principles of law could reshape speech across the country – and even internationally, says Pearl Eliadis, a lawyer and an adjunct professor at both the Max Bell School of Public Policy and the Faculty of Law at McGill University in Montreal.

As the fight has wound its way through the justice system over the past decade, a cultural movement has kicked up outside, from #MeToo to Black Lives Matter, and the pandemic has exacerbated disinformation wars. “We have a much stronger understanding of the importance of equality law and the ways in which speech can be used to silence minorities,” says Ms. Eliadis.

Christopher Bredt, a lawyer for the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, an intervener in the case, argues that a province’s human rights codes are subject to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and that the Supreme Court has already established that discriminatory expression can only be banned if it rises to the level of hatred.

“If the court lowers the standard of what gets protected in the context of the Quebec human rights code, then in effect, it permits the lowering of standards not just in Quebec but across the country,” he says.

“There’s no question that this was offensive and affected the dignity of Little Jérémy in the sense that nobody likes to be made fun of. But sometimes you have to accept that there is going to be expression that takes place that is offensive and harmful to people,” he says. To try and regulate it opens the door to censorship. “Try going to a comedy club in Russia and telling some jokes about Putin.”

Ms. Eliadis counters that this “essentialist view” of free speech doesn’t reflect the laws of Canada or international human rights law; here free speech isn’t as “absolute” as it is under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

“This really is a social choice at some level, about the extent to which a person’s right not to have their dignity affected, not to have harm caused to them because of the fact that they were singled out due to their disability, whether that is more or less important in this case than Mike Ward’s free speech rights,” she says. “I think we need to be vigilant about protecting free speech, but it doesn’t mean that people who are vulnerable, people who have disabilities, people who are from [racial minority] communities, women who are often targeted on social media in particular ... it doesn’t mean that all these people become roadkill in the name of free speech.”

Non-legal solutions?

When Mr. Seguin looks back at the joke, he says he feels empathy for Mr. Gabriel. Mr. Seguin is a father. He flinches when he recounts the joke’s last punch – Mr. Ward saying he couldn’t kill Mr. Gabriel so he looked up what he had, and found out it’s that he’s “ugly.” “His life must not have been easy,” Mr. Seguin says.

Jess Salomon, a Montreal-born comedian in Brooklyn, New York, who used to work as a war crimes lawyer in The Hague, also feels sorry for a child who was bullied at school, but is unequivocal that the question doesn’t belong in court.

“I’m not saying that there shouldn’t be consequences for comedians’ speech. But there are a lot of other things that make more sense as a consequence than being before the Supreme Court for what is clearly a joke,” she says.

Outlets for publicly expressing displeasure, for example, are everywhere. Patrons can talk to the venue or the tour promoter; they can skewer comedians over social media. They can walk out of the room.

But for Ms. Eliadis, that’s a right that the victim himself wasn’t granted. “Jérémy Gabriel couldn’t walk away,” she says. “He was the one who was targeted. Why is he deserving of less protection?”

As both sides await a decision, there is a sense of regret about how far it has all gone. Mr. Gabriel says he regrets the two never met; Mr. Ward has told other media outlets that he would not tell the same joke today. His friend Mr. Seguin says that, had they simply talked, he’s sure Mr. Ward would have shown Mr. Gabriel the generosity he says his friend is known for.

Dan Delmar, a political commentator and managing partner of communications at public relations consulting firm TNKR in Quebec, calls this a classic breakdown in communication.

“The case has gone too far, and it’s gone too far because we’re caught up in a bit of a social panic now on these questions,” he says. “I think as Canadians, we can come up with a better compromise.”

Patterns

Biden wants to beat China. Beijing says, bring it on.

Washington is seeking allies to counter Chinese autocracy, and Beijing is girding for battle. But potential areas for cooperation could persuade both sides to avoid a new cold war.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

As Washington limbers up for what President Joe Biden calls the defining battle of our times – in favor of democracy and against Chinese autocracy – Beijing seems more than ready to take up that challenge.

The United States is seeking to gather allies for the fight, but China is making it clear that those allies will pay a price if they join in too enthusiastically. It has just slapped sanctions on European countries that had sanctioned Chinese officials implicated in the abuse of Uyghur Muslims, for example. Unspoken, but understood, is the threat to close off European access to China’s huge consumer market.

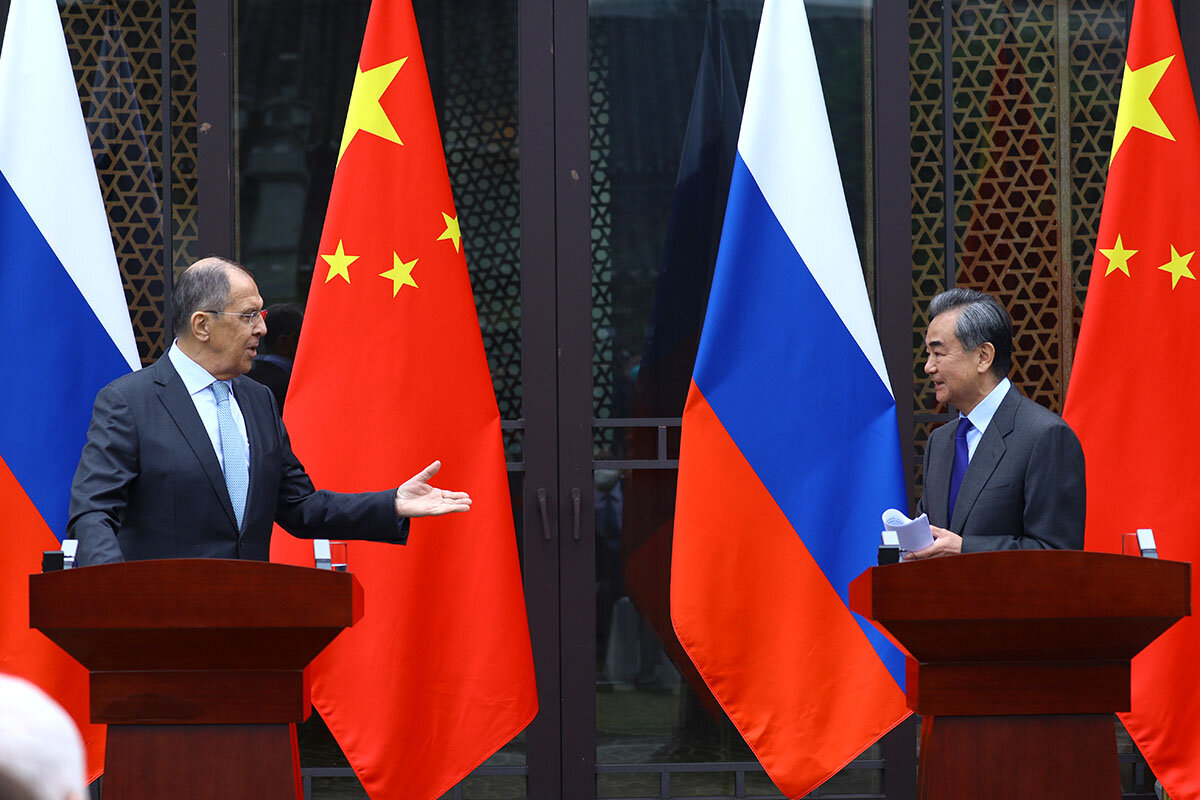

And China has made a point of reminding Mr. Biden that it has friends of its own. In recent weeks Beijing has welcomed Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, Chinese leader Xi Jinping sent a message of support to North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, and China signed a 25-year cooperation agreement with Iran.

Can a new cold war be averted? Both sides have an interest in stopping short of that outcome, and could work together on common interests such as nuclear nonproliferation and climate change. But they will have to tone down their rhetoric.

Biden wants to beat China. Beijing says, bring it on.

If a full-on “new cold war” is brewing between the United States and China – and we’re not there yet – Beijing is girding itself for battle.

As Washington seeks to build a common front to challenge China’s autocracy at home and assertiveness abroad, Beijing is signaling its determination to stymie that move and to build alliances of its own.

The two countries still have an interest in stopping short of Cold War II – a competition not just between two major powers but between rival power blocs across the world stage.

And at the first high-level U.S.-Chinese talks since the election of President Joe Biden – in Anchorage last month – both sides held out the prospect of finding areas for cooperation.

But such talk was drowned out by an extraordinary public exchange of accusations by U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and top Chinese foreign policy official Yang Jiechi. The main dividing line: human rights.

Mr. Blinken set out a frank bill of particulars: the crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong, China’s pressure campaign against Taiwan, and the systematic repression of Uyghur Muslims in the northwestern region of Xinjiang. Mr. Yang suggested that America should look to its own record on human rights before criticizing others.

A few days later, when the U.S., Europe, and Canada imposed sanctions against government officials in Xinjiang, China’s response was striking and unequivocal: Whatever pressure you or your allies bring to bear, we’ll match and raise.

Beijing retorted with sanctions of its own. Significantly, they were targeted more heavily against the European Union, in effect signaling to European countries that they risked paying a heavy price – access to China’s huge consumer market – if they aligned themselves with Washington.

The next day, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi welcomed Russian counterpart Sergey Lavrov on a visit. When Mr. Lavrov denounced Washington for falling back on “the military-political alliances of the Cold War era,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying backed him up. “Just look at the map,” she said, “and you will know that China has friends all over the world. What would we worry about?”

As if to drive home that point, Beijing proceeded to demonstrate the importance of its ties with two countries at the top of Washington’s worry list, and where Mr. Blinken would like Chinese cooperation.

First, nuclear-armed North Korea. Chinese leader Xi Jinping exchanged personal messages with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un reaffirming their alliance. Pyongyang termed this a show of “unity” against the Biden administration’s “hostile” policies.

Days later, Foreign Minister Wang signed a 25-year cooperation agreement in Iran, sealing what he termed a “permanent and strategic” relationship that seems certain to deepen economic, infrastructure, and security ties under China’s “Belt and Road” financing program.

Closer to home, China’s parliament this week further tightened its grip on Hong Kong. It approved changes to the electoral system there, reducing the number of elected seats in its parliament and requiring all candidates to pass muster on their “patriotic” loyalty to Beijing.

The irony is that, at least in the near term, China’s assertive response seems likely to reinforce rather than erode cohesion between Washington and its allies. Popular sentiment toward China in major democracies has been souring. A Pew survey across more than a dozen advanced economies late last year found nearly 8 in 10 people lacked confidence in Mr. Xi to “do the right thing” internationally.

A series of recent reports concerning the Uyghurs – alleging, among other things, the use of forced labor and forced sterilizations – has further hardened criticism of China’s human rights record by members of the European Parliament.

That body must ratify a long-sought EU-China investment treaty, sealed last December. But since Beijing slapped its sanctions on a number of EU legislators, parliamentary ratification is looking increasingly unlikely.

The key question now is whether Washington and Beijing will be minded – or able – to find a way to stop short of across-the-board political confrontation and carve out areas of cooperation.

China’s recent diplomatic embrace of North Korea and Iran may have been intended not merely as a taunt, but as a reminder to Washington: If you want to rein in North Korea’s nuclear arsenal and keep Iran from getting one, you’re likely to need our help.

And there’s another, broader issue where the U.S. administration has made clear that it sees China’s partnership as indispensable: the worldwide response to climate change.

That issue may provide an early sign of whether cooperation indeed remains possible, and the litmus test won’t involve meetings, diplomatic overtures, sanctions, or rhetorical exchanges.

It will come in the shape of an RSVP to a virtual summit on climate change that Mr. Biden is hosting later this month.

Mr. Xi is on the guest list.

A deeper look

Breaking grass ceilings: Why more women are coaching men's teams

Overcoming historic barriers, women are becoming coaches in men’s professional sports in greater numbers, bringing more diversity to one of the last bastions of male-dominated culture.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

-

Connie Foong Staff writer

-

Nick Roll Staff writer

-

Erika Page Staff writer

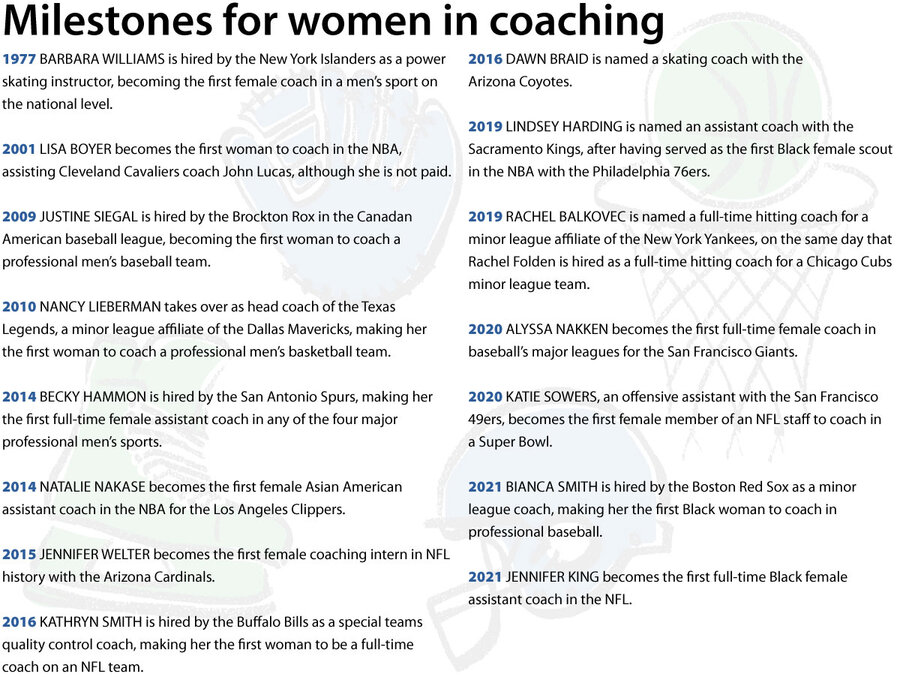

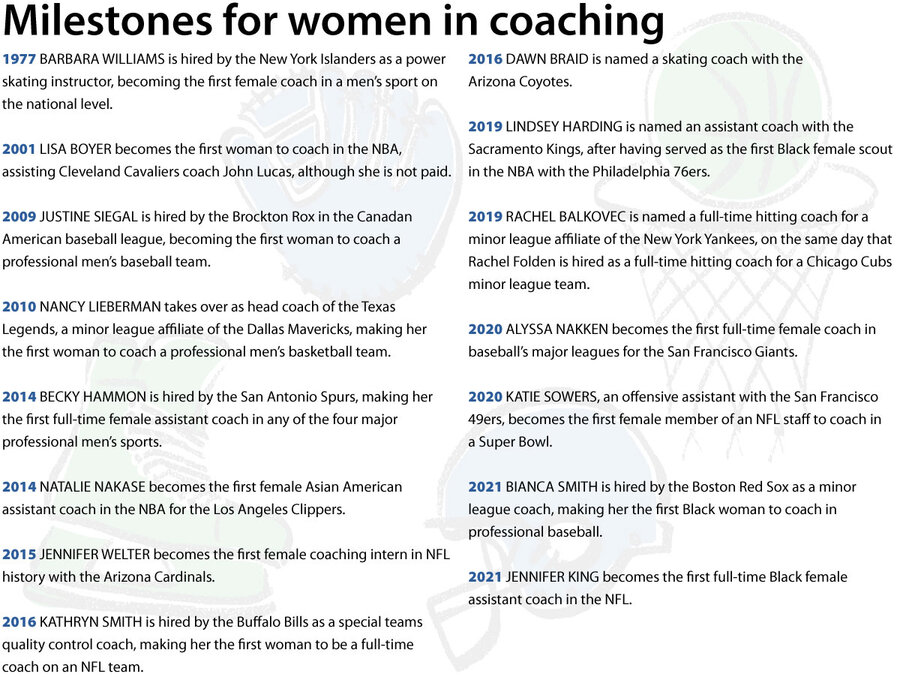

Female coaches are suddenly expanding their presence in the uppermost ranks of men’s professional sports, especially across baseball, basketball, and football. During the past 18 months alone, at least 30 women were working as full-time coaches in MLB, NBA, and NFL organizations.

While women still occupy only a fraction of such positions, their nascent movement into coaching represents what some believe could be the beginning of a second gender revolution in sports almost 50 years after the passage of Title IX. The new coaches are inspiring a generation of young female athletes, bringing greater diversity to dugouts and weight rooms, and may usher in new ways of motivating pro athletes – and even winning.

And their impact goes beyond the athletic field. Because sports occupies a hallowed place in American culture, the movement of women into coaching carries important symbolic significance.

“I think in five years,” says Justine Siegal, who once coached in men’s professional baseball, “you’ll see a major difference and you’ll see almost all programs, all the major professional teams, having female coaches in some capacity. ... We’ve changed.”

Breaking grass ceilings: Why more women are coaching men's teams

The story begins with a question about pink baseball jerseys.

Justine Siegal had been passionate about baseball since her days in Little League. She often slept with one hand gripped on her bat, in case she wanted to practice swings in the middle of the night. She played third base and pitched on her all-boys high school team. Her dream was always to take the field for the Cleveland Indians. But as she grew older and the reality set in that there was no pathway for a woman to become a professional ballplayer, she refocused.

Her new goal: become a coach.

Ms. Siegal honed her academic skills so no one could say she wasn’t qualified. She secured a master’s degree in sports studies. As she completed a Ph.D. in sport and exercise psychology at Springfield College in Massachusetts, she coached the men’s baseball team. One summer she was among a handful of women to join hundreds of men at a meeting of the Society for American Baseball Research. That’s when Ms. Siegal, during a panel discussion, asked her pointed question about professional opportunities for women in baseball.

“What is [Major League Baseball] doing for women besides selling them a pink jersey?” Ms. Siegal recalls saying. “But then I went and introduced myself to [minor league owner] Mike Veeck and said, ‘I want to coach for you.’ And he said he wanted me to coach for him. I interviewed with two teams, and the second team after, like, three interviews took me on.”

With that hire in 2009 by the Brockton Rox, then a member of the independent Canadian American Association of Professional Baseball, Ms. Siegal became the first paid female coach in men’s professional baseball. And, if a current trend of more women in dugouts and weight rooms holds, she won’t be just an asterisk in the narrative of American sports.

Female coaches – especially across baseball, basketball, and football – are suddenly expanding their presence in the uppermost ranks of men’s professional sports. During the past 18 months alone, at least 12 women in MLB organizations, 12 women in NBA organizations, and eight women in the NFL were working as full-time coaches. This doesn’t include the dozens more occupying mental skills and player development roles.

While women still occupy only a fraction of such positions, their nascent movement into coaching represents what some believe could be the beginning of a second gender revolution in sports almost 50 years after the passage of Title IX. The new coaches are inspiring a generation of young female athletes, bringing greater diversity to one of the last bastions of male-dominated culture, and may usher in new ways of motivating pro athletes – and even winning.

And their impact isn’t limited to the athletic field. Because sports occupies a hallowed place in American culture – and is where tough conversations about race, economics, and gender often happen in public ways – the arrival of women into coaching carries important symbolic significance.

“I think it is a revolution, but there’s still work to be done,” says Rachel Balkovec, who was the first female hitting coach hired by an MLB team, the New York Yankees, in 2019, after working as a strength and conditioning coach for baseball organizations for nearly a decade. “In the past year ... I felt more than ever that it’s different. We’re here, we’re supported. We’re not equally represented, but I do think we’re getting equal opportunity.”

The recent influx of women into coaching is being driven by a host of factors, not least of which is the inevitable march of history. Women have been busting through barriers in almost every profession for decades. The doors to locker rooms and film rooms just relented later than most.

“What’s happening on the coaching front is not unlike what’s happening in business, or politics, and all of these other places where we’re seeing more women entrepreneurs, more women in leadership positions, on boards,” says Courtney Cox, an assistant professor at the University of Oregon who studies race, gender, and sport. “These are fights that women have been fighting forever. And so we’re now seeing some of them able to kind of bear the fruits of that labor.”

Yet the biggest reason for the advances is the tenacity of the women themselves. Many have excelled as athletes. They have labored long and sacrificed heavily to build up experience over time, and burnished their résumés by getting advanced degrees. They have taken on short-term contracts and occupied temporary positions – all while chipping away at the glass walls around men’s professional leagues. Perhaps most important, the women who are now guiding and developing professional athletes weren’t afraid to confront the pressures and overcome the doubts of being “first.”

Ms. Siegal, for instance, became used to being the only woman in the locker room: first female coach of a professional men’s baseball team with the Brockton Rox (in 2009 in Massachusetts); first woman to throw batting practice to an MLB team during spring training with, yes, her beloved Cleveland Indians (2011); first female coach employed by an MLB team with the Oakland Athletics (2015, Arizona Instructional League).

Yet almost any woman who secures a paying job in the men’s professional leagues these days becomes a kind of pioneer. In MLB, for instance, Bianca Smith was hired in January as the first full-time minor-league Black female coach with the Boston Red Sox. In the NFL, Jennifer King was named assistant running backs coach in January for the Washington Football Team, becoming the first full-time Black female coach in the league.

In the NBA, Becky Hammon made headlines in December when she became the first woman to serve as an acting head coach after San Antonio Spurs head coach Gregg Popovich was ejected from a game. In September, Sonia Raman became the first full-time, Indian American female coach with the Memphis Grizzlies.

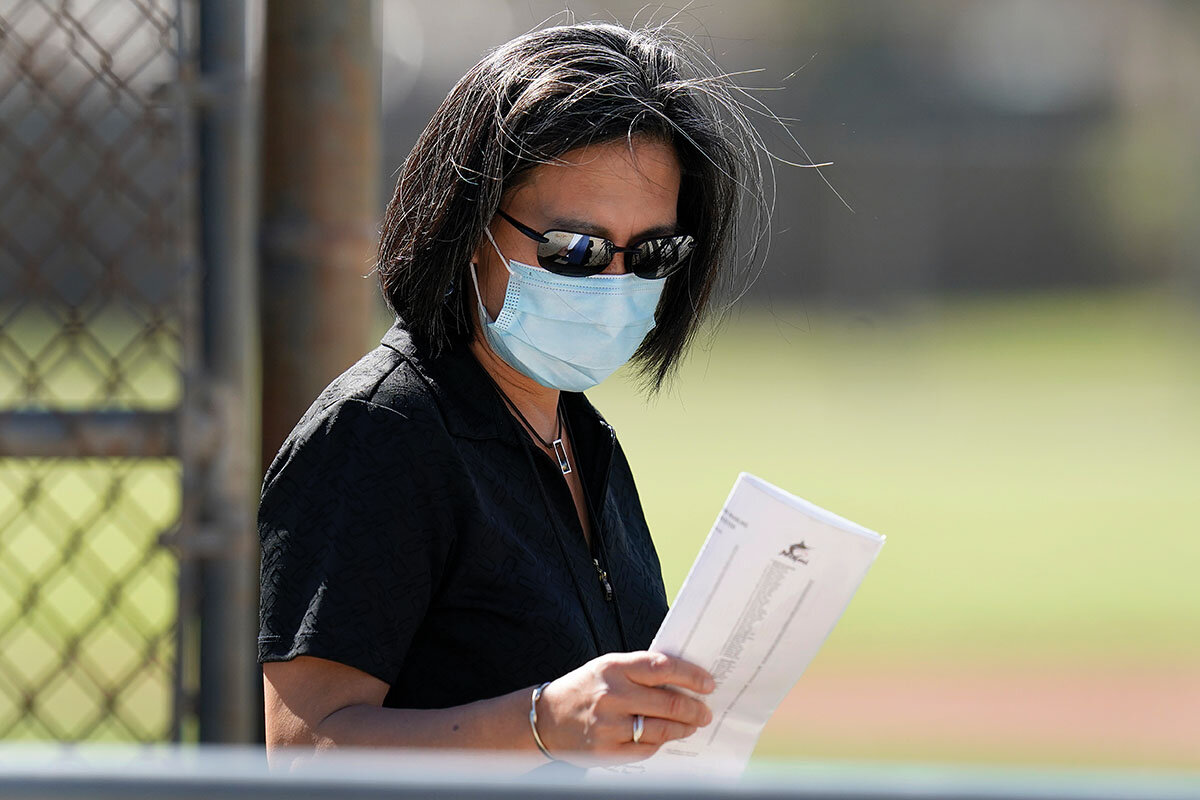

And that’s not counting the 2020 hire of Kim Ng as the Miami Marlins general manager, and the presence of NFL sideline official Sarah Thomas at this year’s Super Bowl – two more thresholds passed.

“Why you wouldn’t want to provide that extra ear, that different perspective, that different voice [by having a woman coach] is beyond me,” says Ms. Siegal.

Women have been helped in their rise by the changing nature of sports. As sabermetrics, big data, and other new technologies have permeated front offices and fitness rooms, teams are hiring a greater diversity of people with a wider variety of skills. During the three years Ms. Balkovec spent with the Houston Astros as a strength coach, the team was beginning to use all kinds of new gee-whiz tools, including sensors by Blast Motion that analyze swings and other activities on the diamond. She managed eight different technologies.

“It used to be just former players [who] got hired as professional coaches,” says Ms. Balkovec. “And now, well, some of our players can’t turn on a computer and they don’t want to learn how. So it’s opened up opportunities for not just women, but nontraditional hires.”

The leagues themselves have also given women a boost – belatedly, some would say. The NFL launched its annual Women’s Careers in Football Forum in 2017 as part of an intentional effort to recruit more women.

In 2018, MLB started a Take the Field program to prepare women for careers in baseball operations and on-field roles. The NBA established the Coaches Equality Initiative in 2019 to find diverse talent and build skills. The NHL followed with its own initiatives in September 2020.

It perhaps makes sense that the leagues are eager to do something for women beyond selling them jerseys, pink or otherwise. Women today account for nearly half the fans who follow big league football, baseball, and basketball, according to various league studies.

In some cases, it can be pressure as much as progressive thinking that gets organizations to embrace diversity, whether in the form of lawsuits or in the need for a change in workplace cultures.

Barbara Rayner is an ardent fan of the Dallas Mavericks basketball team who knows a little something about breaking barriers. She has often been the only woman in the room as a partner for the accounting firm Ernst & Young.

When the Mavericks hired Jenny Boucek as an assistant coach in 2018, she found the timing suspicious. It came six months after Sports Illustrated published an exposé about the Mavericks’ toxic work environment – rife with stories of sexual harassment and domestic violence.

Ms. Rayner was certainly happy with the hire, believing it was long overdue. But she remembers thinking at the time, “I wonder what it took for [Ms. Boucek] to get up to that [level]. She probably had to be twice as good, if not more, and had to clearly have the credentials in order to be able to break through to be put in that position.”

Indeed, Ms. Boucek, a former pro player herself, had 10 years of coaching in the WNBA and already had worked in the NBA as a player development coach for the Sacramento Kings.

The pathway for women to coaching has always been strewn with impediments. Consider the case of Virne Beatrice Mitchell Gilbert.

In 1931, “Jackie,” as she was called, was a minor league pitcher who achieved something few baseball players ever would: In an exhibition game against the Yankees, the 17-year-old struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in succession. A few days later baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis voided her contract and declared women unfit to play the game.

After female players had kept America’s favorite pastime alive while men were off fighting in World War II, MLB formally barred the signing of women to contracts in 1952 for the next 40 years. This ended when the Chicago White Sox drafted Carey Schueler, the daughter of the team’s general manager, in 1993. Girls weren’t allowed to play on Little League teams until 1974, either – a change that came about because of a lawsuit by the National Organization for Women.

Sports leagues continue to lag behind other institutions that were once male-

dominated – from the Supreme Court and the military to corporate boardrooms and higher education – in their gender diversity. Part of that is an entrenched practice of deferring to male applicants at all levels.

Even with the advent of Title IX in 1972, which has increased the number of girls participating in athletics by more than 1,000%, wide disparities persist in coaching. On the college level, for example, less than half the women’s teams are coached by women. The proportion of women heading men’s teams is even smaller – 3%.

Just getting their résumés to be taken seriously can be a challenge for women. “Because of gender bias, women coaches have to be usually more qualified and more competent than their male counterparts,” says Nicole LaVoi, director of the Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women in Sport at the University of Minnesota. “[They have to] have a lot of education, a lot of athletic capital, and leverage that to be perceived as competent as their male colleagues.”

Ms. Balkovec, the hitting coach, has often recounted how she was denied low-level jobs in pro baseball because of her gender. This happened even though she had been named the 2012 Appalachian League strength coach of the year as an intern with the St. Louis Cardinals, spoke Spanish, and had a master’s degree in kinesiology.

Instead of suing for sex discrimination, however, she tried a different tactic: She changed the name on her résumé from Rachel Balkovec to Rae Balkovec. She dropped the word “softball” in front of Division I college catcher.

Hiding her gender on her application did seem to increase the number of callbacks she got. But ultimately it was her connection with the Cardinals coaching staff that landed her first full-time job as a strength and conditioning coach.

Those connections highlight another truism in the modest rise of women in professional sports: For every man that stands in the way of a woman moving into coaching, another one is usually there to encourage and mentor her.

When Jennifer Welter in 2015 became the first woman in the NFL to be hired in a coaching position for the Arizona Cardinals, many credit the vision of head coach Bruce Arians. In February, Mr. Arians made history again when he won the Super Bowl as head coach for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers with one of the most diverse coaching staffs in the NFL, including two women – Lori Locust and Maral Javadifar.

“I would hope that other owners would look and see that this works,” Mr. Arians said during a pre-Super Bowl news conference.

It’s the kind of message that advocates for women like to hear. Women should be seen as creative contributors, they say, not as intruders in the world of men’s sports.

“Every individual whether they’re male or female has their experiences to offer,” says Jessica Chin, professor with the department of kinesiology at San Jose State University. “In my mind, just teaching men that women can have authority, too, that women know about sports – that’s important.”

But an openness to diversity requires a shift in culture – away from the old-boy’s world of towel-snapping locker rooms, overt sexual harassment, and definitions of “true masculinity” tied to physical dominance. For head coaches, that means considering applicants who don’t look or think like they do.

“I think it’s easy to hire people that you know. And sometimes maybe that’s something that works against [female coaches],” says Rex Ryan, the former Buffalo Bills head coach who hired Kathryn Smith in 2016 as the first woman in a full-time NFL coaching position. Ms. Smith got the job as the Bills’ quality control coach, in part because she was familiar – she had worked with Mr. Ryan for years in an administrative position after climbing her way up from an internship in 2003.

“The main thing is your passion, your work ethic, and your accountability and team chemistry. And I think if whoever – a female, whoever – fits that, then why not consider them?” says Mr. Ryan.

Many athletes are welcoming the presence of women as coaches. This is particularly true among some of the younger players, who have grown up with modern views of gender and aren’t as steeped in the ethos of the past.

When Ms. Welter showed up as a coaching intern for the Arizona Cardinals, she already had plenty of on-field experience. In 2014, she was the first woman to play running back in a men’s professional football league with what was then the Texas Revolution of the Indoor Football League. The Revolution later hired her as a linebackers coach. She also had a master’s degree in sport psychology and a Ph.D. in psychology.

And the men she coached had done their homework. “Those guys [in Arizona] knew everything about me before I even walked in the door,” says Ms. Welter. “They’d watched my game film. They talked to people who knew me from Dallas.” But more important, they recognized the significance of her hire. “The guys were really excited to be a part of history and changing the culture within the NFL,” she says.

The lessons women have learned in grinding their way to the top pro leagues, and the different approaches they bring to the sidelines, can help them in working with their new charges. Both Ms. Siegal and Ms. Balkovec talk about the patience required to earn players’ trust.

While coaching the Sydney Blue Sox in Australia over the winter, Ms. Balkovec says, there was a veteran player on the team who was resisting a new philosophy on hitting even though he was struggling. So she spent weeks chatting with him about his family, his girlfriend, how he spent his weekends.

It paid off. One day in the batting cages, he opened up. “Finally, he asked me a question about his swing, ‘Well, what do you think I should be doing?’ And I just thought, wow, I’ve been waiting for this moment for two months.” She leaned in with statistics to pinpoint weaknesses in his swing and how to fix them.

“We won’t know if it’s made an impact until this season,” says Ms. Balkovec, “but I would say it’s made an impact in the way that he trains and his approach at the plate.”

Still, not everyone sees the presence of women in batting cages as an automatic sign of progress – including some fans. Sam Kaufman roots for the San Francisco Giants. He was surprised that the team hired Alyssa Nakken in January 2020, making her the first female coach in the big leagues. Just because she played college softball and has a master’s degree in sports management, he says, doesn’t mean she is qualified to coach baseball at the highest level.

“In any organization, especially the Giants who are coming off of far too many consecutive losing seasons, hiring a female because it’s groundbreaking might feel nice ... but as a fan, I want to maximize value everywhere I can in the organization,” says Mr. Kaufman, who works as a money laundering analyst at a consulting firm.

In the end, one question underlies this budding sports movement: How far will it go? Will there someday be gender parity in coaching? Will a female manager win a World Series championship, or hoist a Super Bowl trophy?

The women now clearing a path to a new future aren’t all contemplating such grandiose ideas. In fact, many are hesitant to talk about gender at all. Their idea of success is reaching the point where everyone – society included – judges them by their skills and talents, not their sex.

To reach that moment will require many more women coming up through the ranks, ready to guide tomorrow’s hitters and three-point shooters. Some are already trying to mold the next generation.

Ms. Siegal and Ms. Welter, for instance, are working to build the presence of women in baseball and football from the ground up. Ms. Welter runs flag football camps for girls to reinforce that they have a place on the gridiron. Ms. Siegal’s organization Baseball for All supports 40 teams of girls across the country and is working to introduce women’s baseball at the collegiate level.

“It’s a lot of work. I’ve always seen it as work for a generation. I’ve never thought it was going to be a short-term effort,” says Ms. Siegal. “I think in five years, you’ll see a major difference and you’ll see almost all programs, all the major professional teams, having female coaches in some capacity. ... We’ve changed.”

And for those revolutionary coaches still to come, no pink jerseys will be required.

Commentary

‘Ground zero’ for voting rights. How Georgia’s new law fits with its past.

History can be a useful touchstone for determining progress – and identifying patterns that impede it. When it comes to voting rights in Georgia, our commentator warns of the latter.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

On the heels of their defeat in Congress and the White House, Republicans across the country have advanced controversial voting bills – most notably in Georgia. Senate Bill 202, which Gov. Brian Kemp signed into law last week, contains a number of provisions that many consider to be a deterrent to voting – along with an option that would allow officials essentially to overturn the vote.

Stacey Abrams, founder of Fair Fight, called the bill “a redux of Jim Crow in a suit and tie.” Her comments bring to mind past events that helped to birth Jim Crow.

For example, the Camilla massacre in September 1868 followed the expulsion of the “Original 33” Black members of the Georgia General Assembly. One of the expelled members, Philip Joiner, led a mostly Black coalition of marchers from Albany to Camilla to attend a Republican political rally. The marchers were met with violence, resulting in around a dozen deaths.

The signing of SB 202 wasn’t violent like the Camilla massacre. But it was a direct response to the political gains made by and for African Americans in Georgia.

America is always in the midst of reconstructing itself. If history is our guide, vigilance is needed.

‘Ground zero’ for voting rights. How Georgia’s new law fits with its past.

Georgia’s current voter suppression saga began with a bid for governor back in 2018. The contest between Democrat Stacey Abrams and eventual Republican winner Brian Kemp was embroiled in controversy – and not just because Mr. Kemp was secretary of state at the time.

Mere months before the election, a plan to close seven of nine polling places in Randolph County drew the ire of civil rights groups and activists alike. While the plan was turned back due to the efforts of the ACLU, among others, the air of disenfranchisement was pungent.

Despite her defeat months later, Ms. Abrams was undeterred.

Her speech acknowledging that Mr. Kemp would be Georgia’s next governor was defiant:

Make no mistake, the former secretary of state was deliberate and intentional in his actions. I know that eight years of systemic disenfranchisement, disinvestment, and incompetence had its desired effect on the electoral process in Georgia.

The speech also noted the birth of Fair Fight Georgia (now called Fair Fight), dedicated to election reform and voter fairness. Ms. Abrams was the face out front for a network of activists and civil rights groups that pushed back against voter suppression and encouraged voter participation. Two years after political heartbreak, redemption came in the form of a presidential victory for Joe Biden and two U.S. Senate seats.

Georgia Republicans were undeterred.

“Ground zero” for voting rights

On the heels of their defeat in Congress and in the White House, Republicans across the country have advanced controversial voting bills – most notably in Georgia, which many have considered “ground zero” for the debate on voting rights.

Senate Bill 202, which Governor Kemp signed into law last week, contains a number of provisions that many consider to be a deterrent to voting – along with one that could lead to overturning the vote:

- The secretary of state will no longer chair the State Election Board. The new chair must be nonpartisan, but he or she will be appointed by a majority of the state House and Senate. That ruling currently skews the decision in Republicans’ favor and could allow appointees to essentially overturn elections. It also disempowers Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, who came under fire from the former president and fellow Republicans due to claims of a fraudulent election, despite two recounts confirming Mr. Biden’s victory.

- It is now illegal to give food and water to people standing in line to vote. The measure is seen as an attack on predominantly Black precincts, where voters have significantly longer wait times to cast their ballots than those in white areas.

- In Fulton County, where residents are predominantly people of color and about 45% are African American, the use of its two mobile polling places (buses with voting machines) is no longer allowed, except during an emergency declared by the governor. The buses were employed for early voting last year to alleviate long lines and wait times on Election Day.

During a recent appearance on CNN’s “State of the Union,” Ms. Abrams was particularly critical of the House bill, incorporated in the final law, that ends the right to vote by mail without an excuse and adds voting ID requirements, among other changes:

Well, first of all, I do absolutely agree that it’s racist. It is a redux of Jim Crow in a suit and tie. … It’s not that there was a question of security.

In fact, the secretary of state and the governor went to great pains to assure America that Georgia’s elections were secure. And so the only connection that we can find is that more people of color voted, and it changed the outcome of elections in a direction that Republicans do not like.

Using violence to deny rights and alter results

Ms. Abrams’ comments are a callback to the discriminatory practices of the 1950s and 1960s that effectively denied Black people the right to vote and led to the 1965 Voting Rights Act. But they also recall key events further in the past that helped to birth Jim Crow.

For example, the Camilla massacre in September 1868 followed the expulsion of the “Original 33” Black members of the Georgia General Assembly. In response to Reconstruction, a time of political gains for African Americans, Georgia initially expelled 28 of the 33 for being “one-eighth Black,” and later dismissed the remaining five.

One of the expelled members, Philip Joiner, led a mostly Black coalition of marchers from Albany to Camilla to attend a Republican political rally. The marchers were met with violence, resulting in around a dozen deaths. In terms of suppressing Black votes, the massacre was profoundly successful.

The truth is, political violence and rioting are still fresh – think back to January. Storming the Capitol to overturn the election is consistent with the country’s blood-stained history of voter suppression.

The signing of SB 202 – and the arrest of Georgia State Rep. Park Cannon for knocking on the governor’s door as he livestreamed the signing – weren’t as violent as the Capitol Riot or the racially and politically motivated Camilla massacre. Yet last week’s events were no less vitriolic, and they are a specific response to the political gains made by and for African Americans in Georgia.

America is always reconstructing itself

In January, Raphael Warnock was elected as the first Black senator in Georgia’s history – a history that includes gains made during Reconstruction. Who would have thought it would take more than a century and a half to elect a Black senator?

And yet, because we live in an imperfect democracy, it seems like America is always in the midst of reconstructing itself. That’s what makes this current fight for voting rights so important.

“Georgia still has a decision to make about who will we be in the next election. And the one after that. And the one after that,” Ms. Abrams said in her speech after the 2018 election. “So we have used this election and its aftermath to diagnose what has been broken in our process.”

Reconstruction is always going on – with some progress along the way. The temptation to rest on our laurels is understandable, but if history is our guide, we know full well that injustice never sleeps. Vigilance is needed.

Ken Makin is the host of the “Makin’ A Difference” podcast.

Neighbors feeding neighbors: Community fridges strengthen ties

Can meeting a neighbor’s need help stabilize an entire community? That’s what some in the community fridge movement are aiming for. Second in a series about hunger in America.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As lines at local food pantries began stretching around the block during the pandemic, community fridges emerged as a grassroots response – neighbors feeding neighbors. Community fridges let anyone give and take food freely.

To Mark Bucher, a restaurant owner in Washington, D.C., the appeal of a place to provide free meals was simple: an opportunity to care for others.

Because some sidewalk fridges have been shut down due to city health codes and permit requirements, Mr. Bucher approached the Department of Parks and Recreation at the outset, which quickly agreed to a partnership. His program, Feed the Fridge, now stocks 19 fridges in community centers around the city. Donations to the program go to local restaurants in exchange for meals for the fridges.

Not everyone is a fan of the fridges, though. Some feel they hide more important questions about how to solve hunger.

Diane Hatz, a fridge organizer in New York, understands those critiques. But for now, she believes the fridges revitalize and rebuild communities that have become fractured. She also sees them as a first step in helping neighborhoods take ownership of the local food system. “I’m hoping they serve as a bridge,” she says.

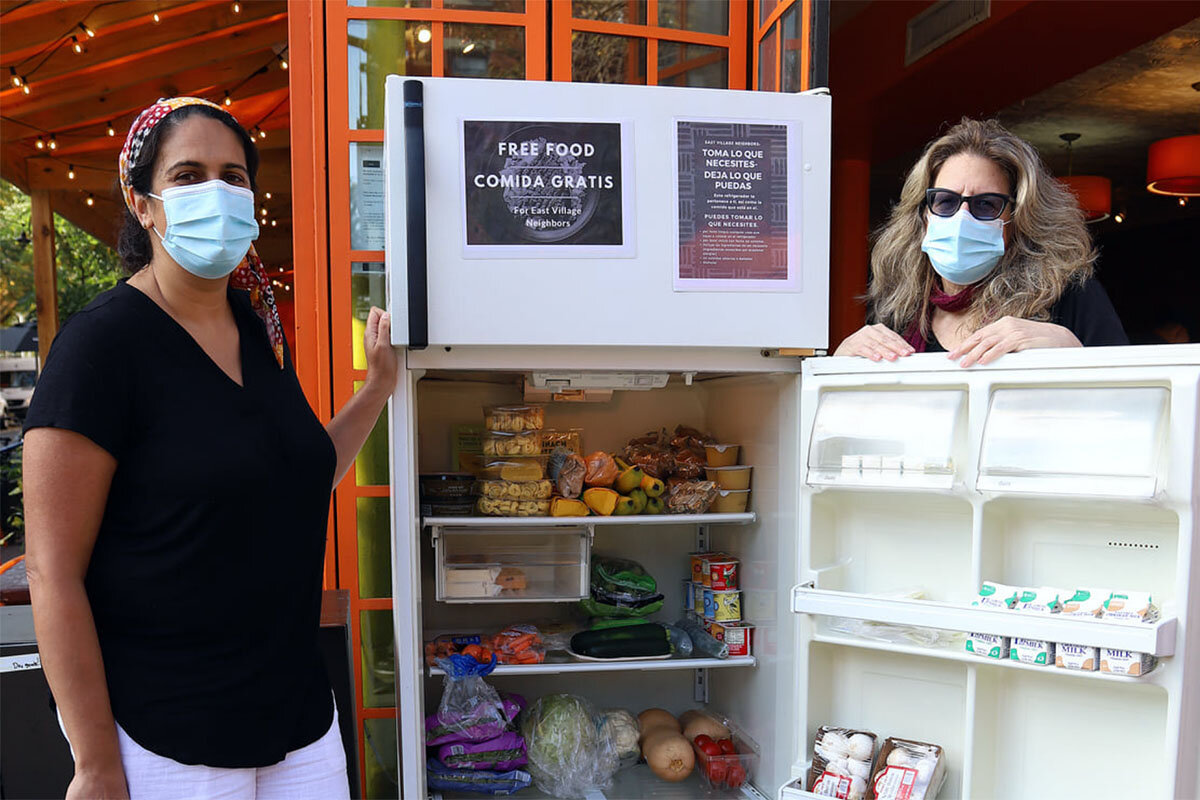

Neighbors feeding neighbors: Community fridges strengthen ties

Taylor Stack, her roommate, and two new friends slowly wrestled the refrigerator up 12 steps to street level and into the waiting truck in a Boulder, Colorado, neighborhood.

The fridge was old and bulky, and a darting dog didn’t help. But it was beautiful – painted light blue with large, bright suns shining on a field of sunflowers. Its final destination: a Denver sidewalk, where it would offer free food to the neighborhood.

“It felt really empowering for us to be able to do it,” recalls Ms. Stack, who works at a shelter for unhoused people in Denver, “just folks coming together, supporting one another, and getting something done.”

The pandemic has shined new light on America’s hunger problem. Last summer, researchers at Northwestern University estimated that food insecurity doubled due to the economic slowdown. Food insecurity was a problem for up to 23% of all households and around one-third of Black and Hispanic households. And since the pandemic began, 35% of lower-income adults have gotten food from a food bank, according to a Pew Research Center survey.

As lines at local food pantries stretched around the block, community fridges emerged as a grassroots response – neighbors feeding neighbors. Similar to Little Free Libraries and Little Free Pantries, only bigger, community fridges let anyone give and take food freely, which is especially helpful in neighborhoods where access to fresh produce is limited.

The concept first appeared in Germany around 2012. Then the pandemic spurred its appearance in cities across the United States. Now, there are more than 160 new community fridges throughout the country, according to the spreadsheet used by Freedge, a food-sharing facilitator.

Although the fridges face a unique set of challenges – upkeep, food safety, and a place to plug in – they have become an emblem of mutual aid, a concept that has become popular during the pandemic. Mutual aid is different from charity, say activists, because instead of forming a one-way relationship, it builds cooperative networks based on solidarity. And although some experts feel the fridges hide more important questions about how to solve hunger, the community relationships they are forming could serve as a bridge to longer-term solutions.

“Meeting the need that’s right in front of us”

To Mark Bucher, the appeal of a place to provide free meals was simple: an opportunity to care for others. So when schools closed last March, he called around. “What’s the plan?” he asked. As a restaurant owner in Washington, D.C., he wanted to help make sure no child went hungry in his community. “I had been seeing some news stories about community fridges,” he says, “and I’m like, ‘Maybe I can fill these with meals.’”

Because some sidewalk fridges have been shut down due to city health codes and permit requirements, Mr. Bucher approached the Department of Parks and Recreation at the outset, which quickly agreed to a partnership. Mr. Bucher’s program, Feed the Fridge, now stocks 19 fridges in community centers around the city. Donations to the program go to local restaurants in exchange for meals for the fridges.

“It’s a way of presenting these meals to those that are in need in a dignified manner,” says Delano Hunter, director of the Department of Parks and Recreation. “I know there’s a time and place for policy,” he says, but “we just want to focus on meeting the need that’s right in front of us.”

For their part, the community centers are happy to distribute the meals to those they serve, no questions asked. “They probably won’t tell you they’re hungry, but it’s going on everywhere,” says Sebrena Rhodes, who coordinates a community center for children in Ivy City, a low-income area of Washington. Every day she gives out fresh meals from the center’s Feed the Fridge refrigerator. “They combat hunger but they’re also helping the restaurants, and so that’s a win-win situation,” Ms. Rhodes says.

Can “neighborliness” end poverty?

Not everyone agrees. Some say that community fridges, like other forms of emergency food distribution, can’t address the real problem behind hunger – poverty.

“The food distribution system has never worked for people in under-resourced communities,” says Rae Gomes, executive director of the Brownsville Community Culinary Center. She believes community fridges are a “feel-good” response that doesn’t encourage people to think about why poor people are hungry in the first place.

Andy Fisher agrees. To him, the problem is the way the U.S. understands hunger.

“I think that we’ve made a decision as a society to separate out hunger from poverty,” says the author of “Big Hunger: The Unholy Alliance Between Corporate America and Anti-Hunger Groups.” By treating hunger as a technical problem to be solved by handing out food, Mr. Fisher says, we ignore the conditions that create hunger – like unemployment, low minimum wages, high costs of living, and medical bills. Community fridges may be a sign of “neighborliness,” he says, but they don’t solve these problems.

Diane Hatz understands these critiques. Ms. Hatz is the founder of East Village Neighbors in New York, which organized a community fridge last spring. “A fridge is a Band-Aid and a stopgap,” she says. She wants to see long-term solutions to the country’s hunger problem, but for now, she believes the fridges revitalize and rebuild communities that have become fractured.

Like Mr. Bucher and other organizers, Ms. Hatz expects her fridge project to continue and grow beyond the pandemic. And she feels that fridges are a first step in helping neighborhoods take ownership of the local food system. “I’m hoping they serve as a bridge,” she says.

Miles away in Denver, Ms. Stack has similar hopes. She says the fridges show “what can happen when you actually invest in a community.”

Previously, she had been considering leaving Denver. “I felt a complete lack of community before COVID,” Ms. Stack says. But when she joined Denver Community Fridges, she met dozens of people working to support their neighbors. “During a time when the government hasn’t been taking care of us in a way that we need,” she says, “we, as individuals, have stepped up in communities across the country to take care of one another.”

She is no longer thinking about leaving her community.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A bit of sunlight on Ukraine corruption

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Just two years ago, the International Monetary Fund decided it would use its financial leverage to nudge corrupt countries toward honest and transparent governance. Because corruption hides in the dark, the IMF said, it would “harness the immense power of sunlight” to put countries on a healthier economic path. The agency’s approach may finally be paying off in a country pivotal to the contest between Russia and the West: Ukraine.

In recent weeks, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy has taken his boldest steps yet to crack down on corrupt oligarchs and high-level judges who have blocked anti-graft measures. One big reason: Ukraine’s economy needs a $5 billion loan from the IMF as well as the agency’s nod to foreign investors that the country is finally tackling corruption, especially in the courts.

The IMF is not alone in applying pressure on Ukraine. In early March, President Joe Biden placed sanctions on a key oligarch, Ihor Kolomoisky. The United States sees Ukraine as a “linchpin” for reform in former Soviet states.

Little noticed at the time, the IMF decision to put more sunlight on the dark side of corruption has begun to have a global impact.

A bit of sunlight on Ukraine corruption

Just three years ago, the International Monetary Fund decided it would use its financial leverage to nudge corrupt countries toward honest and transparent governance. Because corruption hides in the dark, the IMF said, it would “harness the immense power of sunlight” to put countries on a healthier economic path. The agency’s approach may finally be paying off in a country pivotal to the contest between Russia and the West: Ukraine.

In recent weeks, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy has taken his boldest steps yet to crack down on corrupt oligarchs and high-level judges who have blocked anti-graft measures. One big reason: Ukraine’s economy needs a $5 billion loan from the IMF as well as the agency’s nod to foreign investors that the country is finally tackling corruption, especially in the courts.

Elected two years ago on an anti-corruption platform, Mr. Zelenskiy has disappointed many in Ukraine. Yet he is also up against a well-entrenched culture of corruption. In February, he froze the assets of one oligarch, Viktor Medvedchuk, who is a friend of Russian President Vladimir Putin. In early March, Mr. Zelenskiy posed a question to all the country’s oligarchs in a video address: “Are you ready to work legally and transparently, or do you want to continue to create monopolies, control the media, influence deputies and other civil servants?”

His government has lately nabbed officials trying to escape the country with stolen money or fleeing prosecution for corruption. And the president has taken the unusual step of dismissing two judges on the country’s constitutional court over their participation in rolling back anti-corruption reforms.

The IMF is not alone in applying pressure on Ukraine. In early March, President Joe Biden placed sanctions on a key oligarch, Ihor Kolomoisky. And the European Union is insisting on more reforms before Ukraine can join the trade bloc. “President Zelenskiy, we are your friends; we will support you at every stage of your path to the rule of law and reform of the judiciary in Ukraine,” said European Council President Charles Michel.

The United States sees Ukraine as a “linchpin” for reform in former Soviet states. “If Ukraine succeeds, then other countries farther to the east will understand that many of the false narratives and claims by Russia are simply not true,” George Kent, U.S. deputy assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, told Voice of America. One of those Russian “narratives” is that a country does not need civil-society groups as a watchdog on corruption.

The U.S. has another reason for international pressure to clean up Ukraine’s politics. It needs a successful model in helping it curb corruption in Central America, where graft is one of the main drivers of migration to the U.S.

Little noticed at the time, the IMF decision to put more sunlight on the dark side of corruption has begun to have a global impact.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Present-day resurrection

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mary Alice Rose

On Easter and every day, the same Christ-spirit that enabled Jesus to overcome death is here to heal and raise us up.

Present-day resurrection

Christians around the world will soon be celebrating Easter, which commemorates Christ Jesus’ resurrection from the dead. His resurrection changed human history. As a Christian Scientist, I feel deep gratitude and reverence for the spiritual strength, moral courage, forbearance, fidelity, and selfless love Jesus expressed. It offers such a compelling example to us all.

Jesus knew long before he was arrested what awaited him. He foretold more than once that he would be sentenced to death and then raised on “the third day” (see Matthew 16:21 and 20:19). Jesus must have prayed deeply throughout his ministry to prepare his thought for what lay ahead. His utter humility was on full display on the eve of the crucifixion, when he prayed to God, “O my Father, if this cup may not pass away from me, except I drink it, thy will be done” (Matthew 26:42).

The writings of Mary Baker Eddy, a follower of Jesus and the discoverer of Christian Science, speak to Jesus’ state of thought as he administered the sacrament at the last supper with his disciples. Mrs. Eddy wrote, “With the great glory of an everlasting victory overshadowing him, he gave thanks...” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 33).

I love the idea that what overshadowed Jesus in this moment was not a sense of suffering, death, or failure, but the anticipation of “the great glory of an everlasting victory” over injustice, dishonor, sin, sickness, and death! The resurrection both illustrated and symbolized the destruction of evil. Jesus proved his oneness with divine Love, with God. His giving thanks to God at the last supper was an essential step toward victory.

Jesus’ sacred career serves as an example, not a substitute, for us all in finding salvation from evil. We have the ongoing opportunity to prove his words, “The kingdom of God is at hand” (Mark 1:15). We can do this because, although Jesus is not here personally, the same Christ-spirit that governed Jesus, the same sense of God’s power and presence that enabled him to rise above evil, is here today. The Christ, Truth, that lifted Jesus in the resurrection saves and heals us now.

The initial evidence that Jesus had risen from the dead was the immense stone rolled from the mouth of the sepulcher where Jesus’ body had been placed (see Mark 16:4). Mrs. Eddy referred to this stone symbolically during an address at an Easter service. She said, “What is it that seems a stone between us and the resurrection morning?” Then she answered: “It is the belief of mind in matter. We can only come into the spiritual resurrection by quitting the old consciousness of Soul in sense” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 179).

Jesus’ resurrection proved that life is not dependent on matter. Each of us can prove this to whatever degree we have grasped this truth. Spiritual understanding lifts us into infinite possibilities of life based in divine Soul, Spirit, God, universal good. This lifting of thought is present-day resurrection.

A woman once asked me to pray with her regarding a physical condition that caused her to be concerned for her life. She and I gave thanks in our prayers that life is dependent on God, Spirit, alone. God, being the source of all existence, cannot be extinguished or even diminished. Therefore, she could not, as Spirit’s offspring, express less than the full reflection of Life.

I soon discovered this woman was feeling a lack of love in her life because her parents had passed on. We further reasoned together that God, divine Love, was her true and ever-present Father-Mother. Because we can never be separated from this divine Father-Mother, we can never truly be separated from parental guidance or from the Love that is God.

Day by day, as we prayed, the woman felt strengthened, both mentally and physically. One day, after a period of steady improvement, she reported with great joy that she was well: All the symptoms had ceased. And in the intervening years, the healing has proved complete.

The eternal Christ is here to lift each of us to the realization of the allness of Spirit, Life, Truth, Love, enabling us to see the healing relevance of Christ in our lives. Each of us can experience our own sense of the resurrection. And this is cause for great celebration on Easter and every day.

A message of love

Hot doggin'

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow when our Simon Montlake will explore an experiment in Chelsea, Massachusetts, that puts cash directly in the hands of people in need and how it fits into broader interest in a universal basic income.