- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Biden ran on competence. A slew of challenges are testing that promise.

- What happens when protesters take over for the police?

- Can China and America be frenemies on climate change?

- From inside a Ugandan camp, one refugee helps others tell their stories

- Going ‘bold’: How the pandemic is changing New York’s Lincoln Center

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What happened when a Black music critic disliked a Beyoncé song

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

For a culture writer who has dived fearlessly into the tough issues of race, the idea seemed harmless. Wouldn’t it be fun to rate Beyoncé’s 10 best and 10 worst songs?

Little did Candace McDuffie know. Monitor readers will know Candace. She’s graced our pages many times, writing about music festivals for people of faith and remarkable books by Black authors. But when she wrote her Beyoncé list for Glamour magazine, something odd happened. Twitter went crazy.

How dare she criticize Beyoncé? Who did she think she was? The hate rolled in, topped by the oddest accusation of all: She must be anti-Black. It was a sobering moment. “It was hard to swallow,” she tells me. “All these stories that I’d done about race and Blackness and white supremacy, and it’s a piece about Beyoncé that goes viral.”

Truth be told, writing about race had brought her much worse comments in the past. But it was a reminder of how too often America’s race conversation turns to using identity as a weapon – in this case, a narrow sense of Blackness that sought to punish an opinion outside the collective thinking.

For Candace, it’s all the more reason to keep writing the deeper stories that perhaps don’t go viral, but help America wrestle with the complexity of race. “I’m going to keep doing the work that I do,” she says. “I am a Black person in America, and I want to uphold my people.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

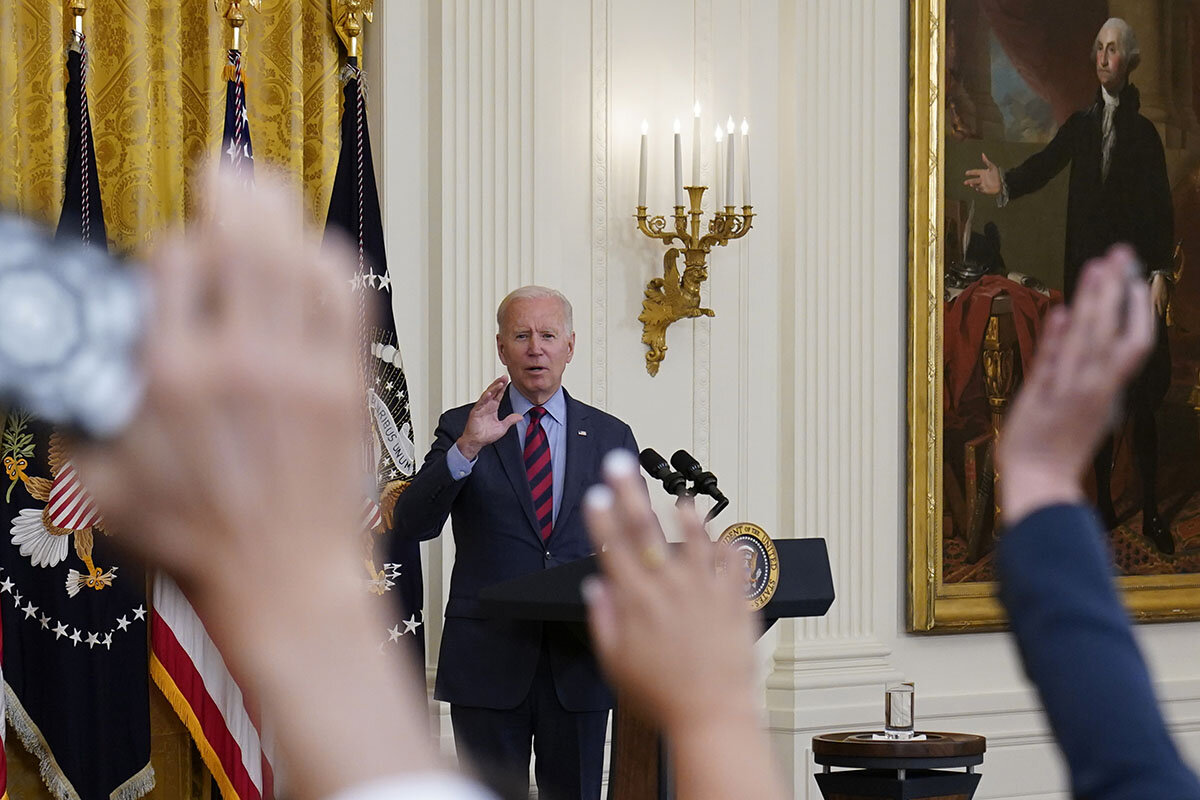

Biden ran on competence. A slew of challenges are testing that promise.

New administrations have learning curves. President Biden’s struggles prove that but might also point to a deeper issue: a bureaucracy not nimble enough to meet 21st-century challenges.

Joe Biden’s campaign watchwords were competence, experience, empathy. But since Inauguration Day, one challenge after another has tested the new president and his administration in ways both foreseen and unimagined, denting the reputation of a man who took office amid high hopes.

A summer COVID-19 surge fueled by the delta variant dashed expectations of a return to quasi-normality. A different surge – of migrants at the southern U.S. border – has also put the Biden team on the defensive.

And following the United States’ chaotic, deadly exit from Afghanistan, President Biden is digging out of his biggest foreign policy crisis yet. The Taliban have returned to power; Americans and Afghans qualified for evacuation are still trying to get out.

Mr. Biden’s biggest challenge of all – the pandemic – threatens to engulf his presidency, with major implications for all aspects of American life. On Thursday, the president laid out a new six-pronged strategy to fight the delta variant and increase vaccinations.

“First years are problematic for presidents,” says presidential historian Russell Riley. Even eight years as vice president isn’t the same as having the top job, he says. And the president’s team, no matter how talented, won’t have fully jelled this early on. “The only way to mount the learning curve is over time.”

Biden ran on competence. A slew of challenges are testing that promise.

The contrast was meant to be sharp: a seasoned Washington veteran replacing a president who arrived a political novice and was voted out after one tumultuous term.

Joe Biden’s campaign watchwords – competence, experience, empathy – applied both to himself and to the team he would bring in. But since Inauguration Day, one challenge after another has tested the new president and his administration in ways both foreseen and unimagined, denting the reputation of a man who took office amid high hopes.

A summer COVID-19 surge fueled by the delta variant dashed expectations of a return to quasi-normality, laying bare the limits of government. A different surge – of migrants at the southern U.S. border – has also put the Biden team on the defensive. The Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack last spring, disrupting access to fuel up and down the East Coast, found the nation’s cybersecurity apparatus wanting.

And following the United States’ chaotic, deadly exit from Afghanistan, President Biden is digging out of his biggest foreign policy crisis yet. The Taliban have returned to power. Americans and Afghans qualified for evacuation are still trying to get out – though some dual nationals, including Americans, were able to leave Kabul on Thursday. U.S. relations with NATO allies have been damaged.

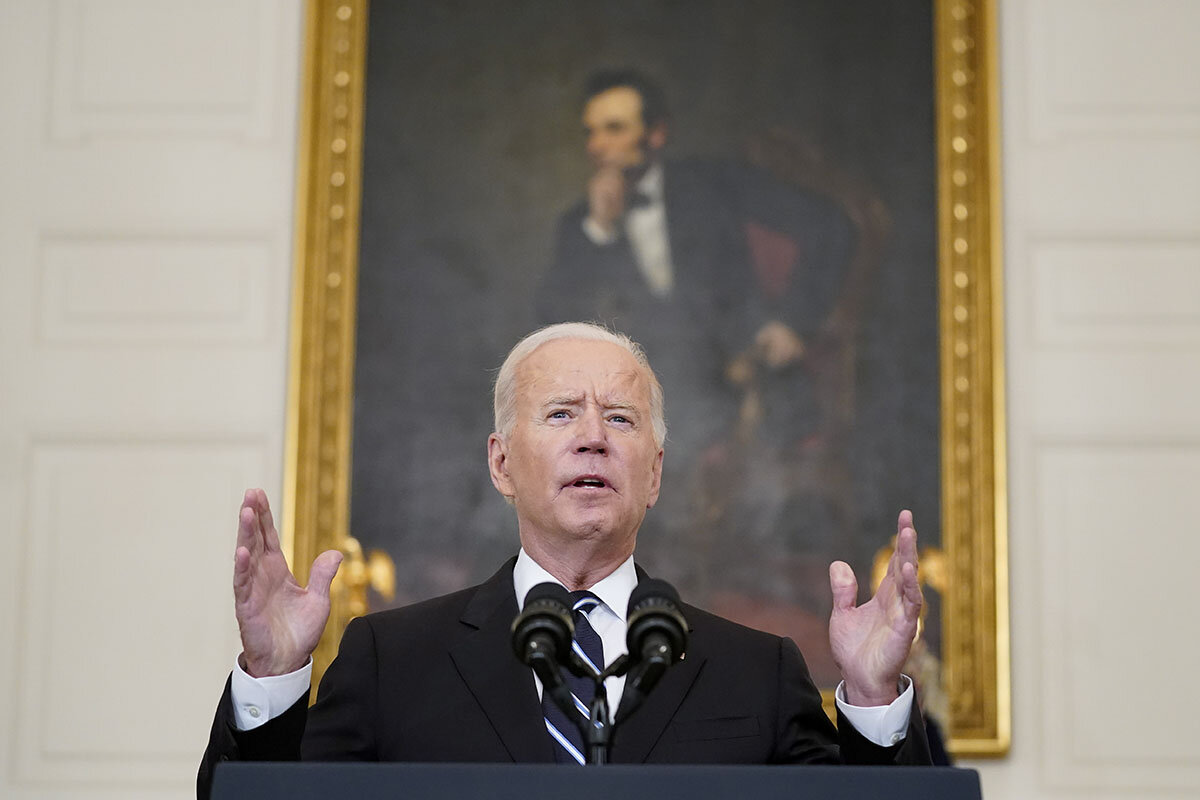

Mr. Biden’s biggest challenge of all – the pandemic – threatens to engulf his presidency, with obvious major implications for public health, the economy, education, essentially all aspects of American life. On Thursday, the president laid out a new six-pronged strategy to fight the delta variant and increase vaccinations.

“We have tools to combat the virus, if we can come together as a country and use those tools,” Mr. Biden said in a televised address from the State Dining Room in the White House, at times visibly frustrated with the resistance he says has slowed the U.S. efforts to fight the pandemic.

“First years are problematic for presidents,” says presidential historian Russell Riley of the University of Virginia. “There’s a tendency to a kind of innocent arrogance in the early part of an administration. You think that because you succeeded in winning the White House, your judgment is golden.”

For President George W. Bush, the first year in office was punctuated by the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 – a historic “failure of imagination” on the part of an unprepared U.S. government, as The 9/11 Commission Report famously stated. The ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in April 1961 is another prime example of a new president, John F. Kennedy, stumbling badly early.

President Bush came to office having never served in Washington, only as Texas governor. President Kennedy, barely in his 40s, came straight from the Senate. In contrast, Mr. Biden brings to the table more experience in elective office than any American president in history.

Still, even eight years as vice president isn’t the same as actually having the top job, says Professor Riley, co-chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at UVA’s Miller Center. The president’s team, no matter how close to the president or talented as individuals, won’t have fully jelled this early on, he adds. “The only way to mount the learning curve is over time.”

A “slow-moving horror show”

Regarding the U.S.’s 20-year occupation of Afghanistan, Mr. Biden said he had to abide by the deal the Trump administration had struck with the Taliban to withdraw U.S. forces, or risk prolonging a “forever war.”

His insistence in July that the U.S. would not see a repeat of the chaotic 1975 withdrawal from Vietnam was soon belied by facts on the ground. Yet even as U.S. intelligence began to see that the Afghan government could collapse imminently, Mr. Biden didn’t waver. America was pulling out.

The U.S. military ultimately evacuated some 124,000 people, initially amid heartbreaking images of Afghans desperately clinging to a U.S. cargo plane as it took off – and the horrific terror attack at Kabul’s airport on Aug. 26 that killed 13 U.S. service members and scores of Afghans.

Overall, the U.S. withdrawal was a “slow-moving horror show, though we did regain our balance a bit with that superb air evacuation,” says retired Brig. Gen. Peter Zwack, a former senior U.S. military intelligence officer in Afghanistan.

By the Aug. 31 pullout deadline set by Mr. Biden, the U.S. was unable to evacuate between 100 and 200 Americans who wanted to leave, the administration acknowledges. And most Afghans who applied for Special Immigrant Visas, or SIVs – intended for those who helped the U.S. government – are still in Afghanistan.

The backups in the SIV program represent another challenge of governance: how bureaucratic processes, albeit often legitimate, can delay action.

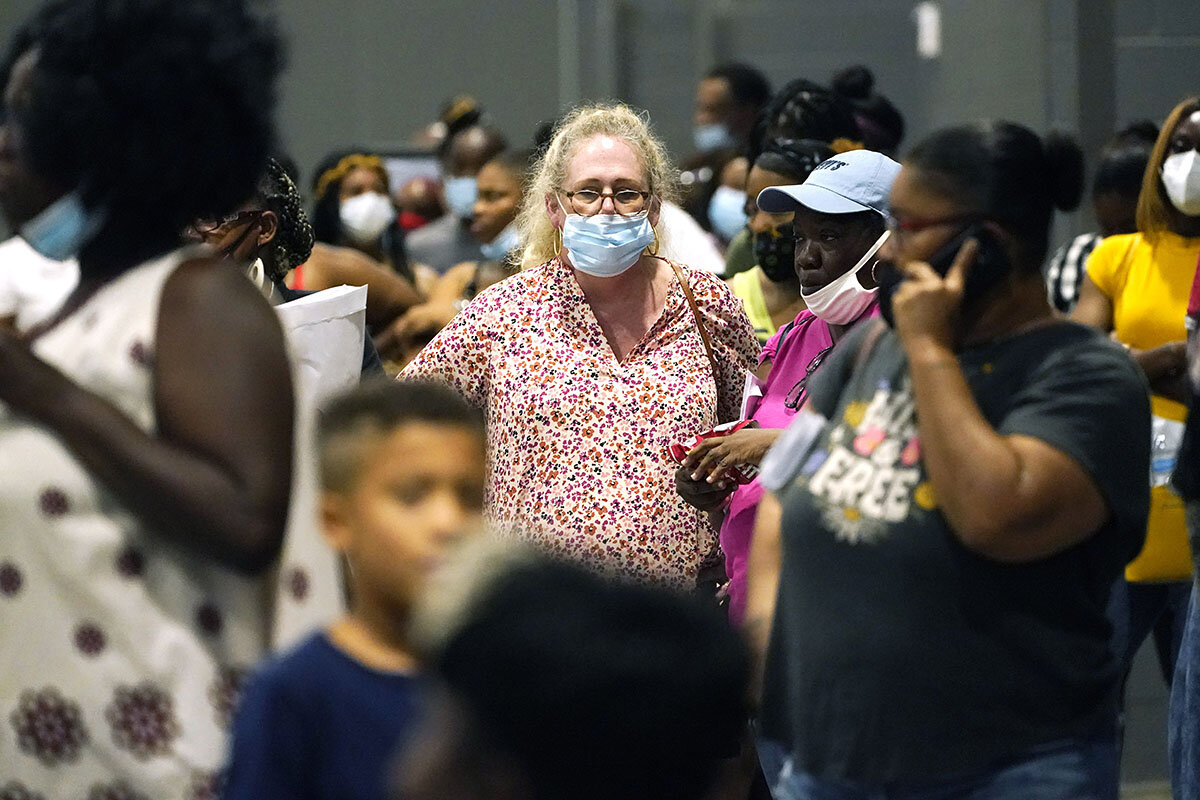

Another example, in a different context, is the slow disbursement of federal rental-assistance money intended to prevent evictions during the pandemic. By the end of July, only 11% of the $5 billion funding the program had been disbursed – in part because of the nation’s federalist system. The money is distributed by state and local governments.

The Treasury Department has announced changes to speed up the process. Adding urgency to the matter, the Supreme Court two weeks ago struck down a national moratorium on evictions.

Looking at American government writ large – from fighting terrorism to helping people in need – there’s an obvious problem, says Elaine Kamarck, director of the Brookings Institution’s Center for Effective Public Management.

“It is not agile,” says Ms. Kamarck, who served in the Clinton White House.

“Essentially the 20th century was a century of bureaucracy. We created bureaucratic structures, which did a good job of meeting the issues of the day. But as we move into the 21st century, those structures are a little bit clunky when it comes to dealing with 21st-century problems.”

Take the issue of terrorism. The U.S. invaded and conquered an entire country – Afghanistan – to carry out what is in effect a police function: stopping attacks.

Then there’s cybersecurity, which defies the notion of jurisdiction, the essence of law. “We are having trouble adapting government organizations to this very new and fluid phase we’re in,” Ms. Kamarck says.

Max Stier, CEO of the nonpartisan Partnership for Public Service, comes back to the fact that the Biden administration is still getting up and running – with a lot of top jobs vacant. Of the 800 government positions the partnership tracks, only 127 have been confirmed by the Senate. The Food and Drug Administration, for example, still doesn’t have a permanent commissioner – in the middle of a pandemic.

“It’s the equivalent of Super Bowl Sunday coming on, and your team has on the field the quarterback and the center but none of the offensive line,” Mr. Stier says. “It’s crazy. And we’re deep into the administration.”

“That’s actually a really important component of what’s breaking down now and what has broken down before,” he adds.

A reset for the pandemic?

Early in his presidency, Mr. Biden seemed keenly aware of managing public expectations. His guiding principle seemed to be “underpromise, overdeliver.”

That came through in his early handling of COVID-19. A month before taking office, Mr. Biden announced that in his first 100 days, 100 million Americans would get vaccinations. By the 100-day mark, more than 220 million shots had been administered.

Since then, any expectation of an orderly national effort to confront the pandemic has fallen by the wayside. When it comes to mask mandates in public schools, for example, governors either require them, forbid local jurisdictions from imposing mandates, or state no position.

There’s also been a disconnect between the White House and two key federal agencies – the FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – over when and for whom to recommend certain booster shots. A decision is expected soon.

On Thursday, Mr. Biden’s new “action plan” on COVID-19 contained six broad categories. The provisions include a requirement that all companies with 100 or more employees ensure workers are vaccinated or tested weekly; potential disciplinary measures against federal employees who refuse to get vaccinated; and a call for all schools, teachers, and staff to set up regular testing consistent with CDC guidance.

Mr. Biden is losing ground with the public in his handling of the pandemic – from 62% approval on July 1 to just over 52% now, according to the FiveThirtyEight analysis of polls.

Republicans, for their part, are casting Mr. Biden as a modern-day Jimmy Carter, the one-term president whose tenure included the Iran hostage crisis, gas lines, and major economic woes.

All presidents go through rough patches, and their ability to weather them depends on many factors – including political skill and events beyond their control.

Mr. Biden’s job approval ratings held steadily above 50% from January onward, but went “underwater” – more disapproving than approving – in mid-August and have stayed there.

It’s too soon to say if Mr. Biden can recover politically, or how the recent rough sledding might influence the 2022 midterms. Most Americans, of both parties, agree with the decision to get out of Afghanistan. The problem was execution. Political analysts surmise that by November of next year, memories of the messy and tragic pullout will have faded.

But in the meantime, Mr. Biden needs other things to go well – handling of the pandemic, the economy, national security.

Paul Light, a professor of public service at New York University, praises Mr. Biden and his staff as “among the most accomplished policy designers we’ve ever seen in the White House.”

But he dings them on policy delivery: “They have a confidence in government that I think is misplaced.”

What happens when protesters take over for the police?

Protesters are creating cop-free autonomous zones as a statement against police violence. But the line between citizens’ rights and law and order is hard to draw.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The “Free State of George Floyd” was in some ways a laboratory. In the hours after police clashed with demonstrators in Minneapolis, protesters occupied what became known as George Floyd Square. Police pulled back and an “autonomous zone” was born.

The same thing happened from Seattle to Atlanta to New York City. In 2016, the ranchers’ takeover of an Oregon wildlife refuge shows the same tactic can appeal to the right. But what happens when police withdraw and citizens take over?

In George Floyd Square, a group of local leaders made some headway in establishing public services associated with “the gated community experience,” one leader said. But there was also increased violence, and Atlanta is now being sued after a young girl was killed in an autonomous zone overrun by gangs.

“When police are absent, you understand that the issue is about sovereignty, not just coercion by the police,” says political scientist Vasabjit Banerjee. As the Supreme Court grants the police more power over individuals, the question emerges: “Who is sovereign?” he asks. “And is the state doing its duty by ceding sovereignty to groups?”

What happens when protesters take over for the police?

When Michael McQuarrie entered the George Floyd Square autonomous zone for the first time last year, he felt as if he was entering a freer, friendlier, and, in some ways, edgier America.

To some, the neighborhood had become the “Free State of George Floyd.” To him and many there, it proved more broadly that a community can not only function, but thrive, without police authority: that physical autonomy empowers citizens.

And then there were the gun shots.

“Policing in Black and trans communities has been so brutal over 30, 40 years ... that a lot of people are just traumatized, and they cannot find relief unless they know there are no cops around,” says Mr. McQuarrie, an Arizona State University sociologist who created a short documentary about the rise of George Floyd Square. “Mind you, [such zones] are very safe in that they are free of police violence. But you still have a lot of armed young people around.”

United States cities have long had unofficial “no-go zones” that are policed by community members instead of officers. But last year, as police cracked down on protesters after the murder of Mr. Floyd, citizen-created autonomous zones appeared in Atlanta; Seattle; New York City; Philadelphia; and Richmond, Virginia.

The takeover of Zucotti Park in New York City during the 2011 Occupy protests set the stage for such zones to be used in direct protest. The 2016 occupation of Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge by a group of antigovernment ranchers showed that the desire to seize land as a retort to perceived authoritarianism is not defined by partisanship.

Autonomous zones are often spontaneous, ad hoc, and short-lived. But their increasing prevalence as a means of protest raises legal and ethical questions about the balance between citizen autonomy and the public safety problems that can be unleashed.

The relative success of George Floyd Square, where community leaders negotiated garbage pickup and emergency medical services, contrasts with the gang violence that broke out in Atlanta, where a young girl was shot and killed. In a nation where the Constitution grants citizens inalienable rights, the line between those rights and collapse of law and order is not an easy one to draw.

“When police are absent, you understand that the issue is about sovereignty, not just coercion by the police,” says Vasabjit Banerjee, a political scientist at Mississippi State University.

As the Supreme Court has whittled away at rights against search and seizure, police have been granted more power over individuals. “But who is sovereign?” he asks. “And is the state doing its duty by ceding sovereignty to groups?”

Why zones crop up

Today, one of the largest autonomous zones in the world is Rojava, a sliver of land in northeast Syria that sought to create a democratic local government in 2012 amid civil war. Rojava has not received official recognition by any country. But it has been widely hailed as a model for how areas historically prone to authoritarianism and religious intolerance can find space to overcome those forces.

Writing in The Guardian newspaper in 2019, a group of social leaders worldwide said: “By promoting radically democratic and decentralised self-governance, equity between genders, regenerative agriculture, a justice system based on reconciliation and inclusion of minorities, the Rojava experiment has presented a living example of possibility under the most impossible of circumstances.”

In Minneapolis, George Floyd Square emerged from concerns about policing. It appeared in the aftermath of a police crackdown on protests that had at times grown violent. After one clash in the area, a handmade monument to Mr. Floyd lay in tatters.

“When the police destroyed the memorial, that’s when the barricades went up,” says Mr. McQuarrie. “It wasn’t some sort of planned anarchist occupation. It was a community that was in shock of being brutalized. That’s why they did it.”

That motive is consistent across many such zones. They form when people feel the state is denying them lawful access to public spaces.

“The streets, the sidewalks: These are the spaces where protest is supposed to happen, where dissent is supposed to happen,” says Karen Pita Loor, a professor at Boston University School of Law. “When police engage with people in a violent manner, that [access to the public square] is completely and absolutely gone. So an autonomous zone is often a response to long-standing historical frustration on issues of police brutality.”

Keeping law and order

The appearance of gang activity in several such zones, however, has complicated the political messaging and endangered occupants and bystanders. A Minneapolis gunshot detection system found that incidents of shots fired near George Floyd Square rose from 33 in 2019 to 700 in 2020.

That’s why autonomous zones in Atlanta, Seattle, and Minneapolis expressed elements of what Michigan State University sociologist Carl Taylor calls the “third city.” These are areas that are controlled and affected “by poverty, violence, crime, drugs, ignorance and illicit enterprise.” In that way, lawless autonomous zones are simply the outgrowth of the perception that law and order is already absent, variable, or inconsistent.

“When white men storm the capitol in Michigan and threaten the governor, we’re not calling them gangs. But is that not worse than Bloods and Crips?” says Professor Taylor. “That’s why [some Black people] don’t give a damn, because they don’t live in America as it stands for fairness and justice. I’m not condoning [violent gang] behavior. But we shouldn’t be surprised at what we are seeing.”

More recently, he adds, “there seems to be a disappearance of police services in many places. That leaves communities of innocent people who have nothing to protect them, so they hope a gang will try to protect them. But gangs aren’t professional, and that’s how you end up with innocent babies killed.”

Secoriea Turner is one tragic example. The 8-year-old was riding with her mom in her car in Atlanta when they turned into the burned-out Wendy’s where Rayshard Brooks was fatally shot by police. Men with guns appeared and ordered her to turn around. Shots were fired, killing Secoriea.

A lawsuit filed this month now blames the city of Atlanta and Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms for her death. The city failed to maintain order, and the crackdown on the zone after Secoriea’s death, they say, only proves it. The Georgia Bureau of Investigation has since tied at least some members of the group to a street gang. The shooters now face life in prison. A similar suit was filed earlier this year in Seattle by a family of a teenager killed by gunfire in Seattle’s autonomous zone.

What worked in Minneapolis

The legal issues are complex. Governments have broad immunity from liability, especially for actions not taken. The lawsuits argue that city officials violated the victims’ 14th Amendment right to equal protection within the jurisdiction of the U.S. government.

But also strong is the evolution of Fourth Amendment rights to be free from unreasonable state searches and seizure.

“When you do these kinds of informal ceding of power, you are getting really deep into citizens’ rights,” says Professor Banerjee of Mississippi State. “Is it like a new form of federalism?”

If it is, then the square in Minneapolis could be counted as a success. Community leaders negotiated for garbage pickup and emergency medical services. It wasn’t as much a new country as an attempt to give the community the kind of autonomy that more affluent Americans can afford.

“I’m trying to give residents the gated community experience,” Marcia Howard, one of the leaders, would often say during conversations at the barricades.

Their political messages had an effect. Minneapolis shifted $8 million of its $179 million police budget toward social services and adopted stricter rules for police engaging citizens during protests. George Floyd Square also made headway in merging stubborn cultural and political divides within the Black community.

“The most noted sort of division in Black politics is between church politics and the street,” says Mr. McQuarrie. “In Minneapolis, they completely bridged that to keep the protest going for over a year.”

Patterns

Can China and America be frenemies on climate change?

The world’s top two carbon emitters, China and the United States, are essential to progress on climate change. That means disentangling the issue from their broader rivalry.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

President Joe Biden said America had to get out of Afghanistan so as to concentrate on what he sees as the world’s real challenges. Now he is facing two of them at the same time – China and climate change.

As the world reels from extraordinary floods, droughts, and wildfires, and a major climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, approaches, Washington is trying to persuade Beijing – the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter – to make common cause on carbon emissions.

Beijing, though, is showing no signs of playing ball, refusing to work with Washington while the Biden administration continues to criticize its style of government and assertive behavior abroad. Six years ago, the Paris Agreement worked out because Barack Obama made a deal with Xi Jinping. That kind of thing looks unlikely today.

But Beijing could still come round. China is presenting itself as a new global leader; if it is looking for a way to highlight that role, it could do worse than be a standard-bearer on an issue of such overwhelming importance to the planet.

Can China and America be frenemies on climate change?

Getting out of Afghanistan wasn’t just about ending a “forever war.” U.S. President Joe Biden has insisted it was essential if America was to confront the true policy challenges of today’s world – among them a rising China and climate change.

Now, just days later, he finds himself facing both of these issues at the same time. He is trying to balance a tough line on China – its autocracy at home and assertive ambitions abroad – with a bid to win Beijing’s cooperation in the fight against global warming.

How that juggling act turns out has urgent implications, not just for Washington but for the world. The most important climate change conference since the 2015 Paris Agreement is due to get underway in Glasgow, Scotland, in eight weeks’ time. It’s being billed as a make-or-break moment, and active engagement by China, by far the world’s largest carbon emitter, will be key.

The early signs have not been encouraging. When Mr. Biden’s climate envoy, John Kerry, made the case for climate cooperation in China last week, he was given the diplomatic equivalent of an ice bath. The top officials on his schedule “met” with him only by video link. And the message they delivered was unequivocal: that climate issues could not be divorced from overall U.S.-China ties, and that Washington is to blame for the chill in that relationship.

This could just be political theater, a high-profile reassertion of Beijing’s insistence that the 21st century will belong to China and that the influence of the United States and other Western democracies is waning. By the time of the Glasgow summit we should know how China plans to handle its own climate change juggling act, dealing with competing economic, political, and diplomatic pressures as it decides whether to adopt more ambitious carbon reduction targets.

China remains one of the few countries not to have pledged to reach “net zero” carbon emissions by 2050. It’s aiming instead for 2060. But even that goal may be hard to meet unless the Chinese cut back dramatically on coal-fired power, an issue Mr. Kerry has been driving home.

The domestic policy calculus for China is pretty clear. Its leaders are perfectly aware of the threat that global warming poses – not least to their major coastal cities as sea levels rise – and they are working hard to expand production of clean energy. China is by a wide margin the world’s biggest builder and consumer of wind power.

But the same leaders continue to make economic growth their overriding goal, and they believe coal is essential to that: last year China also built three times more coal power capacity than the rest of the world combined.

It’s the diplomatic equation, however, that will matter most in the run-up to Glasgow, the outcome of a delicate diplomatic dance between Washington and Beijing.

While Britain will be hosting the Glasgow conference, it’s the Americans who have assumed the lead role so far in pressing governments to make the clean energy commitments required for it to succeed.

They’ve seized on last month’s sobering report by the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and on a devastating increase in floods, droughts, wildfires, and other extreme weather events, to insist that time is running out for concerted international action. Visiting flood-ravaged areas in the U.S. this week, Mr. Biden repeated the IPCC’s warning: a “code red for humanity.”

The message Mr. Kerry carried to China last week was that “the stakes are very high. It’s not a matter of ideology or politics … it’s a matter of mathematics and physics.”

If the Americans are still holding out hope that Chinese leader Xi Jinping will make common cause with them, part of the reason may be that there is a precedent.

In Beijing in 2014, after months of quiet negotiations, Mr. Xi and Mr. Obama announced a joint climate change commitment that opened the way to global agreement at the Paris conference a year later.

Yet the bilateral atmosphere is far colder now. Political theater or not, Beijing’s treatment of Mr. Kerry reflected China’s genuine reluctance to appear to bow to U.S. pressure or to hand Washington a diplomatic victory.

China also has a substantive concern: whether America itself will stay the course on climate change, having pulled out of the Paris Agreement under Donald Trump. More immediately, Beijing may be waiting to see whether or not Mr. Biden can live up to his own pledges on climate change by navigating his $3.5 trillion budget plan, replete with climate-friendly measures, through Congress.

Still, there is one reason China might yet decide to commit to more ambitious climate targets: its own political ambition.

The “mathematics and physics,” in Mr. Kerry’s words, are no longer in doubt: there’s an international consensus that without far tighter, binding clean energy targets, there’s no way to reach Paris’ goal of keeping global warming in check.

If Beijing is looking for a way to further its burgeoning aspirations of global leadership, stepping up as a standard-bearer on an issue of such overwhelming importance to the planet might be an attractive option.

Difference-maker

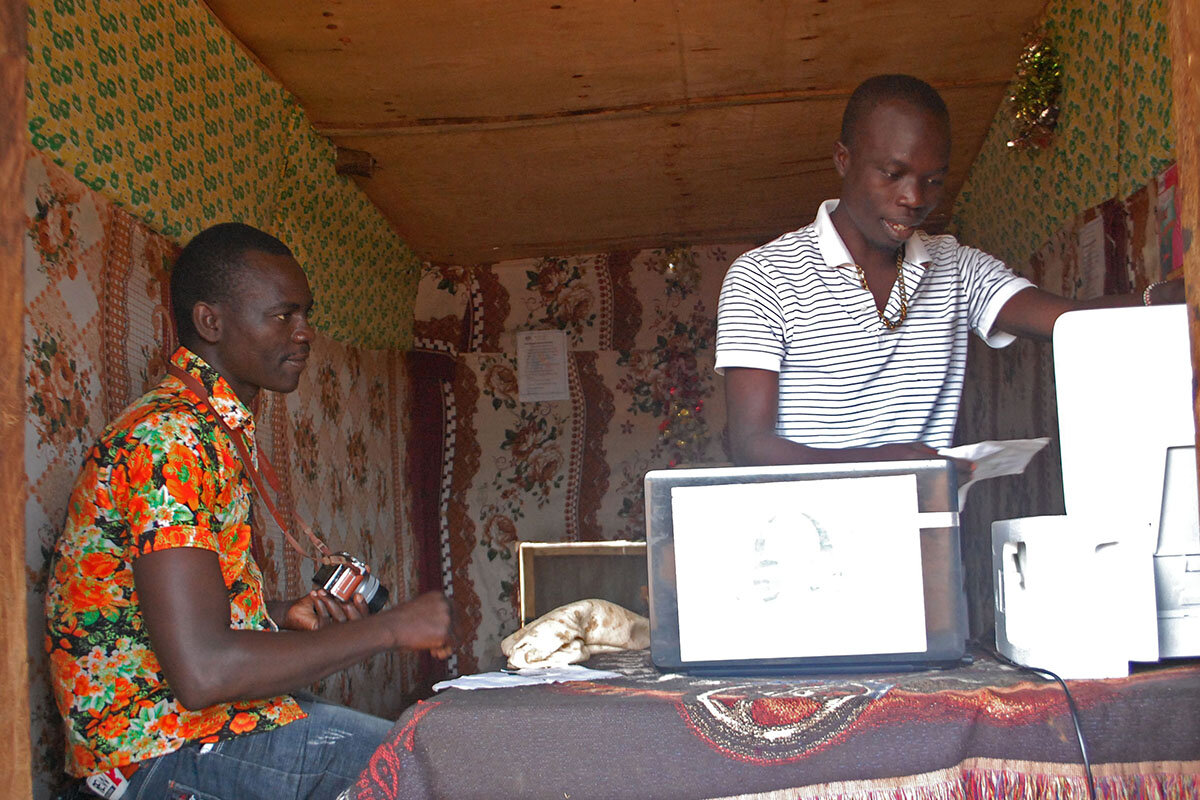

From inside a Ugandan camp, one refugee helps others tell their stories

James Malish fled home when he was four years old. Today he helps give voice to people in his settlement and shares that power by teaching new skills to residents.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By John Okot Correspondent

In a refugee camp of more than a quarter million people, there are as many individual stories. Smart phone in hand, James Malish captures snippets of the refugee experience at the Bidi Bidi settlement in northwestern Uganda and puts them online.

A BBC crew filmed with Mr. Malish at Bidi Bidi, and his Facebook Page, Daily Refugee’s Stories, has generated help for residents in the form of donations for food and repairs that improve residents’ access to water.

As a child, Mr. Malish himself began fleeing civil war and instability with family members, first leaving southern Sudan, then Congo. Today he lives at Bidi Bidi with his wife and four children. His work hands the microphone to people who often have their stories told for them by others, says Moses Acole, who works with refugees in Bidi Bidi. “The mainstream media … tends to dictate the terms on what to cover about refugees, who have no choice” in what stories are written, he says.

“Many people don’t understand what conflict feels like,” says Mr. Malish. “But, with support, you can also land on your feet. I’m a living testimony to that.”

From inside a Ugandan camp, one refugee helps others tell their stories

Growing up in southern Sudan, James Malish often stayed up late into the night, listening to his mother tell folktales by the fire. At school the next day, he would recount the stories to his enthralled classmates, adding his own dramatic flair.

Back then, he saw stories as pure entertainment, a kind of spoken word soap opera to pass the time, and a way for him to be close to his mother and friends.

“I never thought that storytelling had the power [of] helping your community,” he says.

But as civil war tore apart that idyllic life, forcing Mr. Malish and his family to flee to Congo, and later Uganda, telling stories took on a new significance for him. It became a lifeline to the place his family had lost, and a way for people in the community of refugees where he lived to shape how the world saw them. Since May 2019, he has run a Facebook page called “Daily Refugee’s Stories,” a Humans of New York-like platform that shares snippets of the refugee experience in Bidi Bidi, one of the world’s largest refugee settlements.

The stories and photos that accompany them are personal and intimate – a young artist working on a portrait, a group of children roasting sweet potatoes, a gospel musician preparing for a concert.

They bring life in Bidi Bidi – a sprawling settlement of more than a quarter million people near the border with South Sudan – down to a human scale. On Daily Refugee’s Stories, Mr. Malish says, big-picture issues faced by refugees like hunger, lack of clean water, or poor education get personalized treatment, which he and the site’s other contributors hope makes them more relatable and accessible.

It also hands the microphone directly to a group of people who often have their stories told for them by others, says Moses Acole, a community development specialist at the Italian NGO Associazione Centro Aiuti Volontari (ACAV), which works with refugees in Bidi Bidi. “The mainstream media … tends to dictate the terms on what to cover about refugees, who have no choice” in what stories are written, he says.

Mr. Malish’s project started by chance. It was 2018, two years after he’d fled South Sudan for the second time in his life, in the midst of brewing civil war. He saw an advertisement pinned on a notice board at Bidi Bidi, advertising a World Food Program-sponsored course to teach digital storytelling tools to refugees in the settlement. At the time, Mr. Malish was volunteering at a clinic in the settlement, and on a whim, decided to apply.

“I wanted to do something different,” Mr. Malish remembers thinking, “And to do that, I had to apply for this opportunity because I didn’t want to go back [to South Sudan] one day as the same person I was before.”

During the two-week training, Mr. Malish learned about photography, videography, and writing for social media audiences. At the end of the program, he was given a smartphone, and began to post stories and photos on the program’s Facebook group, Bidi Bidi Storytellers.

Soon, Mr. Malish’s posts began to attract outside attention. A BBC crew traveled to Bidi Bidi to film with Mr. Malish, and he decided to create his own, spinoff Facebook page, Daily Refugee’s Stories.

The page quickly gained traction. When Mr. Malish wrote about how a drastic cut in food rations had affected the elderly and single mothers, readers in the United States and South Sudanese in the diaspora came forward with donations. Later, two nongovernmental organizations fixed 10 broken taps and boreholes after Mr. Malish’s page alerted them to the problem.

Rosebell Kagumire, a media specialist who was one of Mr. Malish’s trainers in the WFP course, says when refugees tell their own stories, they are able to “humanize their whole … experience.” This, she adds, helps in “bridging those gaps with the host communities who often fail to understand their needs.”

When Mr. Malish saw how well received his Facebook page was among South Sudanese in the diaspora, he decided to expand and started a small NGO called Afri-Youth Network, which teaches business, tech, and art skills to young people in Bidi Bidi.

“We want to give them a purpose – something they can learn so that they are able to make good out of themselves,” he says.

So far, Mr. Malish has trained about 30 young people in the same kinds of digital storytelling skills he himself was taught three years ago. His course is a month long, and teaches video, still photography, and script writing.

Last year, he was invited by the World Economic Forum to give an online talk about the issues faced by refugees. To him, he says “this was a sign that my work is being recognized as I continue to be the voice of the people in my community.”

Charles Thomas, who came from South Sudan in 2016 and was trained in the storytelling course, says the program helped “because I want to be the voice for the people in the community where I understand their issues since I am part of them.” Mr. Thomas, who dreams of becoming a journalist one day, currently contributes to Daily Refugee’s Stories.

Tonny Charles, who fled from South Sudan in 2017, says that since he completed Afri-Youth’s storytelling program, he has written multiple movie scripts and also acted in feature-length films that he and his program peers film on their smartphones using skills they learned in the program.

“I love storytelling. When I act in film or drama, it makes me a better person after I have freedom to be a different person and live their lives,” says Mr. Charles. “Besides that, most of the subjects [are] social problems that youths face and [the films] are aimed at educating them.”

To Mr. Malish, who lives at Bidi Bidi with his wife and four children, this is just the start. He plans to roll out the program to all refugee settlements in Uganda, just as soon as he can find the money. In the meantime, he has been looking for new ways to tell the stories of South Sudanese refugees in Uganda to the world.

“Many people don’t understand what conflict feels like. They have just watched it in a movie,” he wrote in an op-ed for The Independent in June. “Refugees are people who have really experienced it. You leave your country. You run for asylum. … But, with support, you can also land on your feet. I’m a living testimony to that.”

Q&A

Going ‘bold’: How the pandemic is changing New York’s Lincoln Center

After being stopped in its tracks by the pandemic, New York’s Lincoln Center found ways to move forward. The ability of the arts to educate and celebrate turned out to be invincible.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Jacqueline Adams Correspondent

To get a sense of how the arts fared during the pandemic – and how they’re revving up again – Monitor columnist Jacqueline Adams explores the state of affairs at Lincoln Center. She speaks with Leah Johnson, who holds the multifaceted title of executive vice president and chief communications, marketing, and advocacy officer at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, the landlord of the 16-acre complex.

Despite staggering financial losses and furloughs of half of the staff, there are silver linings. Ms. Johnson describes the center becoming more “nimble,” for example, planning events quickly to respond to the needs of the moment.

Collaboration increased too, she adds.

“Everyone has had to deal with the coronavirus as well as the racial reckoning that has been going on, not only in our city but in our country and, quite bluntly, in the world,” Ms. Johnson says.

“This is the silver lining: While in the middle of the devastation, in the middle of all of the shrinking that we had to do, we have also been able to come together as a campus.”

Going ‘bold’: How the pandemic is changing New York’s Lincoln Center

Broadway’s theaters are beginning to reopen, and one mile north, the 11 arts organizations under the Lincoln Center umbrella – the nation’s largest performing arts complex – have announced their fall schedules too.

Reopenings of the Metropolitan Opera, Jazz at Lincoln Center, the Chamber Music Society, and others, however, may be a moving target, depending on guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s the cautious assessment of Leah Johnson, who holds the multifaceted title of executive vice president and chief communications, marketing, and advocacy officer at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, the landlord of the 16-acre complex.

Monitor columnist Jacqueline Adams sat down with Ms. Johnson to discuss the highs and lows Lincoln Center has experienced during the pandemic. Millions of dollars in revenue have been lost and half of the 300 staffers were furloughed. But, in their lightly edited chat, Ms. Johnson described several silver linings that emerged.

Q: How is Lincoln Center doing?

What wiping out everything does is you start with this clean slate almost. It’s an interesting moment when you can no longer do what you set out to do, which is to put people on stage and to present and to fill seats. You can’t do that. So that becomes a bit of the mother of invention, and, really, you can be bold. You can respond to things more immediately.

With the surge of Asian American and Pacific Islander hate crimes in our city, we commissioned [multidisciplinary artist] Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya. She did a series called “We Belong Here,” [which] is throughout different parts of Lincoln Center.

[Congressman] John Lewis and [minister and civil rights leader] C.T. Vivian passed away on the same weekend. We came to work that Monday and said, OK, what can we do to honor these greats? So we commissioned Carl Hancock Rux, who is a poet activist, and he created a visual [video] poem called “The Baptism.”

Usually, our work requires a year or two in advance planning. But now we’re building the plane as we’re flying. So it’s really shown us that we can be nimble.

Q. Talk to me about the Restart Stages performances. How have the events been received, and is this a way to sort of lure people back to the Lincoln Center campus?

We sat around one day, and we thought, we have 16 acres of outdoor space, right? This is in the height of the pandemic. And we thought, what can we do? How can we utilize the 16 acres, and how can we also kick-start the city’s revival? How can we get people comfortable with coming back to live performances? So, we created these 10 outdoor venues that have been very, very well received.

We launched it with World Health Day, April 7. The mayor came and spoke, and we had some members of the New York Philharmonic playing to honor healthcare workers.

We have co-curated with organizations throughout the five boroughs. Whether it’s the Korean Cultural Center, the Caribbean Cultural Center, the Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance ... all of these organizations, we knew, needed a place and wanted a place to perform. We’ve had dance workshops with the New York City Ballet and film screenings. The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center has been doing evening concerts.

We decided that we would connect with the New York Food Bank, and we’ve done food distributions. We have done blood drives. When there was a need for more polling places, we became a polling site.

We also put “grass” on the Plaza around the fountain. “The Green,” [an installation by designer Mimi Lien], is a soy-based product that can be recycled once we take it up. It is going to be used for playgrounds around the state. From a sustainability perspective, we thought this was just a wonderful, wonderful thing.

Q: What are some of the silver linings Lincoln Center has experienced?

Everyone has had to deal with the coronavirus as well as the racial reckoning that has been going on, not only in our city but in our country and, quite bluntly, in the world. This is the silver lining: While in the middle of the devastation, in the middle of all of the shrinking that we had to do, we have also been able to come together as a campus.

With our colleagues at the New York Philharmonic, we saw an opportunity, once we were out of the halls, to really accelerate the renovation of David Geffen Hall, so that we could open up in 2022, instead of 2024, which could really be a big boon for New York City.

And all the things that we’ve been able to do regarding workforce development, regarding minority and women business enterprise contracts and also workforce inclusion has been just a wonderful, wonderful contribution.

We’re committed to a 30% minimum of minority and women business enterprise contractors to participate in the project. We are now at about 41%, so we have exceeded our goal. We also committed to a 40% workforce inclusion, meaning aggregate hours. We are now at about 54%. We had a graduation ceremony for the 30 graduates who had been paid throughout training and who will now all work on the site, at David Geffen Hall, and become members of the union.

Q: What is your sense of New York City almost post-pandemic?

My sense, Jackie, is that everyone, including Lincoln Center, had to be so creative, had to be so bold, had to really think about ways to create things that would excite people, that would heal people, and that would bring people together and connect people.

So what this pandemic, in the oddest of ways, has done – among the tragedy and among all of the effects that have happened with the racial reckoning – is that it has forced institutions like ours and others to really, really dig deep and think about what we [will be] when we come back. We will come back bolder. We will come back differently and more equitably.

At the end of the day, we are thinking of it as inclusive excellence. [Ford Foundation President] Darren Walker is on our board, and we’re always quoting him. He says, “You know, the arts create empathy, and without empathy, you cannot have justice.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

West Africa’s neighborly mood of countercoup

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

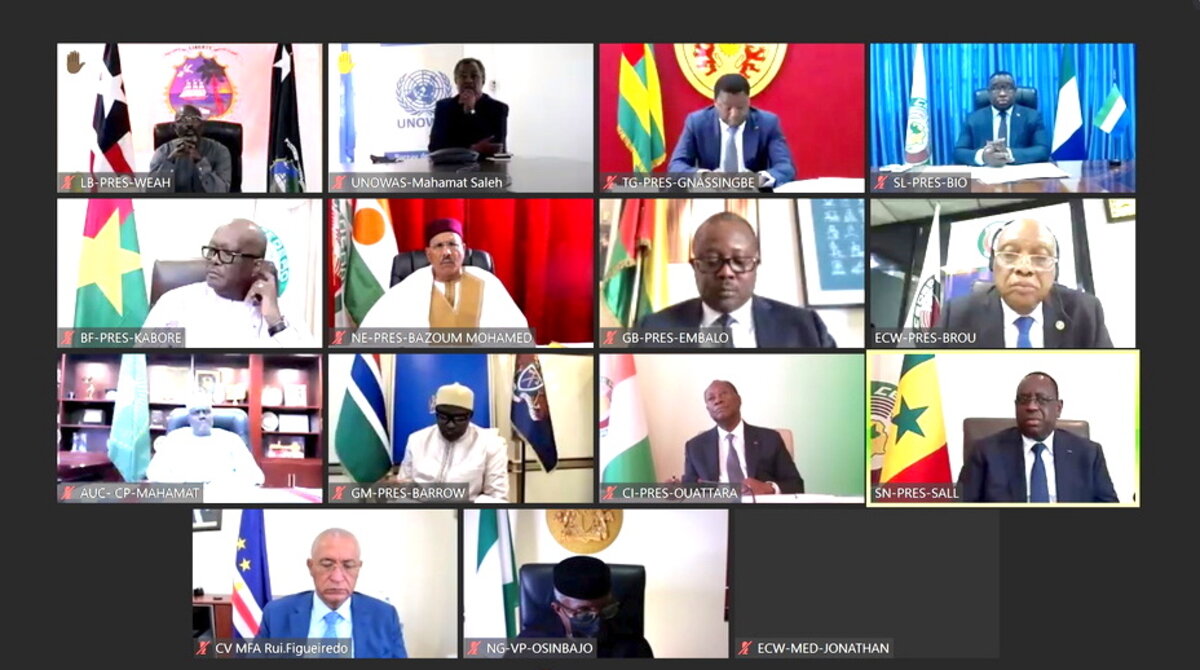

This doesn’t happen in other regions of the world. On Friday, a delegation of West African leaders is due to fly to Guinea just days after a coup to plead for a return to democratic rule. The coup leader seems to welcome the visit. The scene will be like an intervention by neighbors to nudge one of their own to keep the neighborhood in shape.

The swift intervention is designed to halt a dangerous trend. The coup in Guinea was one of four coups or attempted coups in the region over the past year. The trend is a setback for the 15-nation Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). For nearly half a century, the bloc has tried to create a region of peaceful, prosperous nations out of its roughly 400 million population.

“If ECOWAS does not succeed with the impasse in Guinea, a dangerous precedent could be in the making that could encourage and embolden other would-be coup plotters,” warned the news site Liberian Observer.

Sometimes neighboring countries with a shared history can carry more moral weight in holding dictators and would-be dictators accountable, much like the African proverb “It takes a village to raise a child.”

West Africa’s neighborly mood of countercoup

This doesn’t happen in other regions of the world. On Friday, a delegation of West African leaders is due to fly to Guinea just six days after a military coup d’état to plead for a return to democratic rule. The coup leader, Col. Mamady Doumbouya, seems to welcome the visit and also has released at least 80 political prisoners. Perhaps he did not want to become a political orphan in West Africa. The scene will be like an intervention by neighbors to nudge one of their own to keep the neighborhood in shape.

The swift intervention is designed to halt a dangerous trend. The forced ouster of President Alpha Condé in Guinea, a country of 13 million with the richest bauxite reserves in the world, was one of four coups or attempted coups in the region over the past year. The trend is a setback for the 15-nation Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). For nearly half a century, the bloc has tried to create a region of peaceful, prosperous nations out of its roughly 400 million population.

“What happened in Guinea is a brazen disregard for the provisions of ECOWAS Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance, which clearly states that every accession to power must be made through free, fair, and transparent election,” said Nigerian Vice President Yemi Osinbajo.

In its many attempts to restore democracy in member states or keep elected leaders from extending their stay in power, ECOWAS has had more failures than successes. One recent success was its military intervention in 2017 to save Gambia’s democracy. But this latest coup could be a turning point. “If ECOWAS does not succeed with the impasse in Guinea, a dangerous precedent could be in the making that could encourage and embolden other would-be coup plotters in other member countries to take a similar path,” warned the news site Liberian Observer.

The West African bloc could ultimately be more effective than global institutions that also promote democracy. Neighboring countries with a shared history and culture can carry more moral weight in holding dictators and would-be dictators accountable, much like the African proverb “It takes a village to raise a child.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The naturalness of Christian healing

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Blythe Evans

Is healing as Jesus taught miraculous, or inspired by “a divine influence ever present”? We’re all capable of opening our hearts to God’s message of goodness and love for all, which opens the door to healing as Jesus taught and demonstrated.

The naturalness of Christian healing

An incapacitated man was sitting by the wayside begging when he saw two strangers approaching. As he looked up in hopes of a handout, one of the two instructed him to look at them.

The two men, Peter and John, were disciples of Jesus, and this was more than a passing request. I like to think of it as an invitation to see and experience a reality the man begging had not yet known – spiritual reality. Peter then commented that he wasn’t wealthy but would share what he had – which was Christian love, the healing love he himself had experienced from knowing the Christ. Peter then charged the man to stand up and walk, reaching out his hand to lift him up.

At that moment, the man’s feet and ankle bones became functional, and he was able to rise and move forward “walking, and leaping, and praising God” (see Acts 3).

What seems particularly remarkable to me about this account is the naturalness of the healing. Peter and John’s demonstration of God’s healing power did not include any preconditions or caveats – there were no material interventions, time was not a factor, nor did the man’s physical appearance factor in. Rather, they must have felt in their hearts something of the man’s true nature as spiritual, a loved son of God – the divine Love that gives all and only good to each of us. God, divine Spirit, created man (meaning all of us) in the perfect spiritual image of the Divine – whole, strong, and well.

In the Preface to the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” its author, Mary Baker Eddy, states: “Now, as then, these mighty works are not supernatural, but supremely natural. They are the sign of Immanuel, or ‘God with us,’ – a divine influence ever present in human consciousness and repeating itself, coming now as was promised aforetime, To preach deliverance to the captives [of sense], And recovering of sight to the blind, To set at liberty them that are bruised” (p. xi).

How wonderful to realize that the divine influence which brings healing and health is present and revealing itself to us right now. It may not always seem like it, when we’re faced with distress or imperfection of some kind. But even then we can welcome this message of God’s presence and acknowledge all the good it includes. This empowers us to hold to the truth that only what divine Spirit creates is truly legitimate and active, and experience the naturalness of healing.

A few years ago a small flap of skin appeared on one of my eyelids. This didn’t make me very happy, and I had to wrestle with the thought that it might have been inevitable, as my mom had had a similar small skin growth on one of her eyelids for much of her adult life.

To combat these fears and find healing, I started to pray as I had learned through my study of Christian Science. First, I affirmed that nothing unrepresentative of God could exist or be present. Since God is entirely good and God is All, I could trust that everything in God’s creation must be desirable in function, activity, and appearance. If something was not, it could not remain in my experience.

Next I affirmed that as we are all made in the image of God, divine Love, there could be nothing ugly, unnatural, or extraneous about my identity. Nothing could be part of me that is not directly from God. Everything about God, good, is positive and useful; and God knows us not as flawed mortals, but as wholly spiritual, expressing the perfection, beauty, and order of divine Spirit. There is not even a miniscule exception to this fact.

As I prayed, my thought shifted from fear to assurance of Love’s perfection, presence, and care. I grew confident that divine Love alone was present with me, and that my identity could only include the loveliness of divine Spirit. In a week or two I noticed the skin nodule was gone, and it has not reappeared. (And I am happy to say that, as my mom steadfastly prayed, the growth on her eyelid also disappeared in her later years.)

Though prayerful persistence is sometimes needed, Christian healing is neither a mystery nor an arduous chore. It is the outcome of the natural activity of divine Love, revealing to us the bountiful goodness and love that is always ours as the cherished children of God.

A message of love

Departing Kabul

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when Scott Peterson and Ann Scott Tyson explore the advancements in Afghanistan that might endure despite the Taliban.