Redistricting was supposed to look different this year.

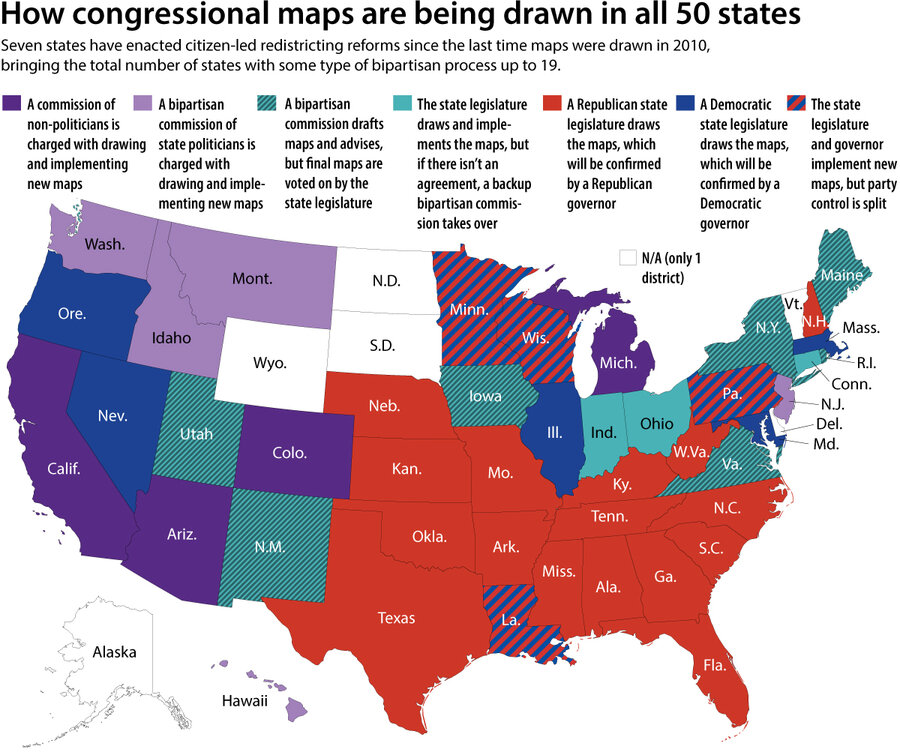

In the 10 years since the nation’s congressional and state legislative maps were last redrawn, a record-breaking number of states passed ballot measures intended to make the process more bipartisan and transparent. The citizen-led efforts were cheered by reform advocates as a win for American democracy, a sign that voters from both parties wanted to end partisan gerrymandering, or the drawing of lines for political advantage.

But with map-drawing now underway, the rubber of those reforms is meeting a very bumpy road.

In Virginia, the first attempt to draw a “fair” legislative map collapsed in acrimony last week and now appears headed for the state Supreme Court. The state’s new bipartisan redistricting commission – which was created in 2020 with support from two-thirds of Virginia voters – has been dogged by partisanship from the outset, with Democrats and Republicans working with separate consultants to produce separate maps and so far failing to merge them.

A similar process is playing out in New York, where 58% of voters approved a measure in 2014 to create a bipartisan redistricting commission, and the commission’s Democrats and the Republicans have also come up with separate maps, not yet agreeing on a compromise.

And in Ohio, where nearly three-quarters of voters approved a 2018 ballot measure to end partisan gerrymandering, a new redistricting commission failed to gain the required bipartisan approval for its state legislative maps. As a result, those maps will now only be in place for four years, including national elections in 2022 and 2024, rather than 10.

While the process remains ongoing, the fact that so many states are struggling to enact reforms that drew broad support from voters underscores the stakes involved. With Democrats holding an eight-seat majority in the U.S. House of Representatives, even subtle tweaking of lines in key states could determine control in 2022 and beyond. That independent redistricting commissions are being undermined by the same partisan forces they’re supposed to be alleviating raises a troubling question: Is it even possible to redraw districts in a way that would be perceived by both sides as fair?

“[The process] feels really existential to people,” says Michael Li, a redistricting expert with the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program. “In our very partisan age, they are having a hard time taking off their partisan hats.”

Under a microscope

According to a 2017 Brennan Center study, extreme gerrymandering in a handful of states during the 2010 redistricting process likely netted Republicans 16 to 17 additional seats in the U.S. House.

In many ways, this is nothing new: district-drawing has been abused for partisan gain since the early days of the republic. In fact, the term for it – gerrymandering – is named after one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

One difference today, say experts, is that more Americans are paying attention.

“Ten years ago, the process just occurred in more of a black box. The maps were produced, passed, and then you were like, ‘Oh I guess this is my new district,’” says Adam Podowitz-Thomas, senior legal adviser at the Princeton Gerrymander Project. “These entities are under a microscope like they haven’t been before.”

According to one recent poll, more than two-thirds of Americans are at least familiar with the term gerrymandering. And majorities in both parties say they would prefer congressional districts be drawn with “no partisan bias,” even if that meant their own party would not win as many seats.

That explains the flurry of citizen-led reforms in recent years, with seven states passing ballot measures to address the problem. In fact, the number of states implementing reforms could have been as high as 12, but a measure passed in Missouri in 2018 was overturned in 2020, and four states – Nebraska, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Oregon – had their required signature gathering hampered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic also delayed the U.S. census, which in turn has drastically delayed the redistricting process. So far, only four states have finalized new maps, with many states fast coming up on constitutional or primary election deadlines.

For this reason, some experts say it’s too early to evaluate the success of the new redistricting commissions.

“The jury’s still out,” says David Wasserman, a redistricting expert and senior editor of the Cook Political Report, at a conference at Duke University in late September. “There is a steep learning curve for citizen commissioners. It sounds easy, maybe, to draw a map, but the technical requirements actually are quite strenuous.”

“What if we made every line less important?”

Mr. Wasserman is referring to four states that are using, for the first time, commissions made up of nonpoliticians to draw and implement new congressional and legislative maps – Arizona, California, Colorado, and Michigan.

Both Michigan and Colorado put their redistricting in the hands of 12- to 13-person citizens’ commissions made up of Republican, Democratic, and independent voters.

In Michigan, the new commission of randomly selected novices approved 10 draft maps on Monday to take to the public for hearings beginning next week. The new maps, which will likely undergo revisions, may not make either side particularly happy – they undo gerrymandering put in place by the GOP legislature 10 years ago, and also eliminate some majority-Black districts – but reform advocates remain hopeful.

“Michigan’s redistricting hasn’t been without its hiccups, but it’s going remarkably well,” says Connie Cook, a retired political science professor and volunteer with Voters Not Politicians, an organization that spearheaded the ballot initiative to reform redistricting in 2018. She notes that the commissioners have not taken a single vote along party lines in the 13 months they’ve been meeting.

Still, that “steep learning curve” that Mr. Wasserman mentioned, along with the census delay, has in some ways already hampered both the Michigan and Colorado commissions’ ability to live up to voters’ expectations. Michigan’s commission had to cancel several public hearings to allow more time to create its maps, and Colorado’s plan for five months of deliberation was condensed into two. Colorado’s maps, which are completed and awaiting verification by the state Supreme Court, would largely protect the state’s seven incumbent representatives, while creating a new, competitive district.

To some experts, even the most successful efforts at redistricting reform will inevitably still fall short.

Voters approved these reforms in pursuit of fairness and better representation, says David Daley, author of the book “Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy.” He argues there are better ways to achieve that – such as multimember districts.

In such a system, the U.S. House would still have 435 members, and seats would still be apportioned to states based on population. But how states allocated their representatives would change.

Instead of nine congressional districts, for example, Mr. Daley’s home state of Massachusetts could have nine lawmakers representing just three big districts, and use ranked-choice voting to select officials. Fewer districts would limit the opportunities to gerrymander, while ranked-choice voting would allow representation for voters of a minority party. There are almost half a million registered Republicans in Massachusetts, for example, but all nine members of Congress are Democrats.

“As long as each [district] line is so important, politicians are going to find a way to exploit every possible loophole,” says Mr. Daley. “So, what if we made every line less important?”

As citizens watch their independent commissions fall short, they should be inspired to think bigger, he argues. “Reformers have to learn the valuable lessons of this cycle,” he says, “which is that commissions as a reform need reforming.”