- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Donors’ dilemma: How to help hungry Afghans ... not the Taliban

- Democrats and Republicans vie to be ‘the party of parents’

- An election in Nicaragua that could further dim democracy

- Europe plans border tax on carbon. Will others join the club?

- ‘Nomadland’ director brings her vision to Marvel’s ‘Eternals’

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Both sides-ism, one side-ism, and journalism’s mission

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

There’s a lot of talk in journalism circles about what’s called “both sides-ism.” The basic idea is that, in some cases, the journalistic approach of representing both sides equally creates false equivalencies. In other words, it makes things seem equal that aren’t.

This is true. Both sides-ism doesn’t work with the scientific view of climate change, for example, or with claims that the 2020 presidential election was stolen. Facts point decisively to one “side” in both cases.

Yet we’re also seeing the potential slippery slope of that kind of thinking. In many cases, the avoidance of both sides-ism has become “one side-ism,” which can be worse. In one side-ism, it becomes relatively easy to delegitimize other viewpoints with which you do not agree by casting them as immoral or nonfactual when, in fact, the situation is multifaceted.

In today’s issue, several stories stress the importance of a willingness to engage in news with all its nuance. How do you help the people of Afghanistan without propping up the Taliban? What does it mean to be the political party fighting for parents’ rights? What’s the line between a genuine auteur and a sellout?

Our aim is to empower you to think about these questions deeply, highlighting humanity and hope wherever it exists. They are complex questions not prone to one-sided answers, and progress rarely comes from convenient shortcuts.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Donors’ dilemma: How to help hungry Afghans ... not the Taliban

Winter is bringing a surge of hardship for Afghans, posing a moral dilemma for foreign aid donors leery of indirectly helping the Taliban. There’s an urgent need to find creative solutions.

-

Hidayatullah Noorzai Correspondent

There is no shortage of urgent warnings, led by the United Nations, about the looming threats this winter to the Afghan people: food insecurity for more than half the population, millions of children under 5 at risk of acute malnutrition. “A countdown to catastrophe,” in the words of David Beasley, head of the U.N. World Food Program.

Yet politicians are finding it unpalatable to resume massive Western aid to a country ruled again by the Taliban, which have been on official U.S. and European terrorist lists for years. So far, the White House has not authorized the release of $9.5 billion in Afghan Central Bank funds, most held in the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Already Afghans who have lost jobs and homes are exhausting what savings they had. Street markets are filled to bursting, as people desperately try to sell household items for cash.

Western donors face “a vicious policy dilemma,” writes Dr. Erica Gaston at the United Nations University in a recent analysis.

Relaxing sanctions, unfreezing funds, and recognizing the Taliban “risk giving away the carrots and sticks that might otherwise be used to induce better behavior,” she writes. Yet, failure to stanch the crisis “could lead to State collapse [and] the immediate suffering of millions.”

Donors’ dilemma: How to help hungry Afghans ... not the Taliban

With their hopes high a year ago that decades of war in Afghanistan would soon be over, they named their newborn daughter Peace.

Rafiullah Arman was a reporter for Afghan state TV, and enjoyed playing the traditional rubab lute for friends. His wife, Khalida, also worked as a journalist.

The Americans had signed a withdrawal deal with the Taliban that promised peace talks, and life was good.

Peace has, indeed, now come. Not long ago “more than 100 funerals were held every day; no one imagined that the sound of gunfire would disappear across the country in a week,” says Mr. Arman. The aspiration in their daughter’s name has been realized.

But the lightning Taliban victory in August has also brought extreme hardship for the young family – as it has for millions of Afghans now facing a perfect storm of hunger, poverty, and economic meltdown as winter approaches under Taliban rule.

Mr. Arman and his wife both lost their jobs, their home, and their hope. The young family was forced to move to a tent camp in the capital before relatives found them a single, windowless room. The money they made by selling Khalida’s jewelry is already spent.

“If hunger had not prevailed after the [conflict], how grateful we would have been for the current peace,” says Mr. Arman. “But unfortunately, the slap of poverty was more powerful and stronger than war, and now we are really suffering.”

That story of overnight transformation – from relative comfort to life-endangering vulnerability – echoes across a country that for two decades has depended on tens of billions of dollars in American and Western aid, which accounted for up to 75% of public spending. That cash has all but stopped flowing since the Taliban takeover.

As a result, a critical decision is now looming: Should the United States and Western donors provide aid – and indirectly help the Taliban regime consolidate power – or stand by and watch Afghan citizens suffer potentially catastrophic consequences?

“If we do nothing, Afghanistan drifts into state collapse. The economic chokehold is squeezing the air out of the economy,” says Graeme Smith, senior consultant for Afghanistan for the International Crisis Group (ICG).

“Temperatures are dropping below [freezing], and Afghans can’t stay warm,” he says. “People will freeze to death. And unfortunately, the experience in some other settings is that a disaster has to be visible before it gets solved. That’s the risk here.”

A “humanitarian-plus” strategy

The danger of state collapse is so great that some donors – led by the Europeans, who fear a wave of fleeing migrants – are trying to expand stopgap emergency measures to find creative ways to alleviate the financial challenge faced by the central Taliban government in Kabul.

“Now the conversation is shifting much more toward … keeping the electricity on and paying salaries for teachers, which are not usually associated with emergencies,” says Mr. Smith. “The line between humanitarian aid and development is blurring, and it’s that blurriness that some European donors are trying to squeeze through now, with what they call a ‘humanitarian-plus’ strategy.”

“There’s a prestige issue, too,” he adds. “If the world lets Afghans starve … it just compounds the shame of the chaotic exit for the international community.”

There is no shortage of warnings, led by the United Nations, about how nearly 23 million Afghans – more than half the population – face acute food insecurity, with 3.2 million children under 5 at risk of acute malnutrition.

“We are on a countdown to catastrophe,” David Beasley, head of the U.N. World Food Program, said last week.

“It is a matter of life or death,” Qu Dongyu, head of the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, warned. “It is urgent that we … speed up and scale up our delivery in Afghanistan before winter cuts off a large part of the country, with millions of people … going hungry in the freezing winter.”

U.S.-held funds frozen

And yet, politicians are finding it unpalatable to resume massive Western aid to a country ruled again by the Taliban, which have been on official U.S. and European terrorist lists for years.

So far, the White House has not authorized the release of $9.5 billion in Afghan Central Bank funds, most of the money held in the U.S. Federal Reserve. The World Bank and other big donors – while issuing dire forecasts about the shrinking economy and suffocating lack of liquidity – refuse to deal with a jihadist regime not yet officially recognized by any nation.

The International Monetary Fund has blocked Taliban access to $440 million in new emergency reserves.

“The very serious nature of Taliban violations, combined with the equally serious humanitarian, economic, and security stakes of the situation, have created a vicious policy dilemma,” writes Dr. Erica Gaston, head of the Conflict Prevention and Sustain Peace program at the United Nations University, in a recent analysis.

Relaxing sanctions, unfreezing funds, and recognizing the Taliban “risk giving away the carrots and sticks that might otherwise be used to induce better behavior,” she writes.

Yet, failure to stanch the crisis “could lead to State collapse, the immediate suffering of millions, mass migration flows, and substantial economic and security ripple effects,” writes Dr. Gaston.

Rising desperation

Already, the crisis is forcing Afghans to fill street markets to bursting, as they try to sell household items for cash.

Desperation is so high that there is an increase in the number of families selling young daughters as brides, CNN reported this week, citing cases in several provinces.

That level of despair is familiar to Amina, a mother of six contacted by the Monitor in a camp for displaced Afghans on the northern outskirts of Kabul. Her husband’s job as a cook – for an Afghan charity organization in northern Baghlan province – disappeared when the Taliban arrived.

Drought also wiped out the cucumber farm where Amina had a job. The couple had to sell their household items so as to pay two months of debt on food and utility bills. She says she contemplated suicide, but, concerned for her children, “can’t do it.”

She cries when discussing the coming winter, though the family this week was moved from a tent to a room in a mud brick dwelling. Amina’s oldest son, 12-year-old Omid – whose name means “hope” – earns barely 50 cents each day, washing cars along the road. Amina’s 10-year-old daughter collects wood from the street.

“If this situation continues, maybe everyone will starve to death because there is no food, there is no work, and prices have gone up a lot,” she says.

In the end, argues, Mr. Smith of the ICG, the solution lies in Washington’s hands. “At the end of the day, the U.S. is the major gatekeeper,” he points out. “This will require action by the Americans if they don’t want the state to fail.”

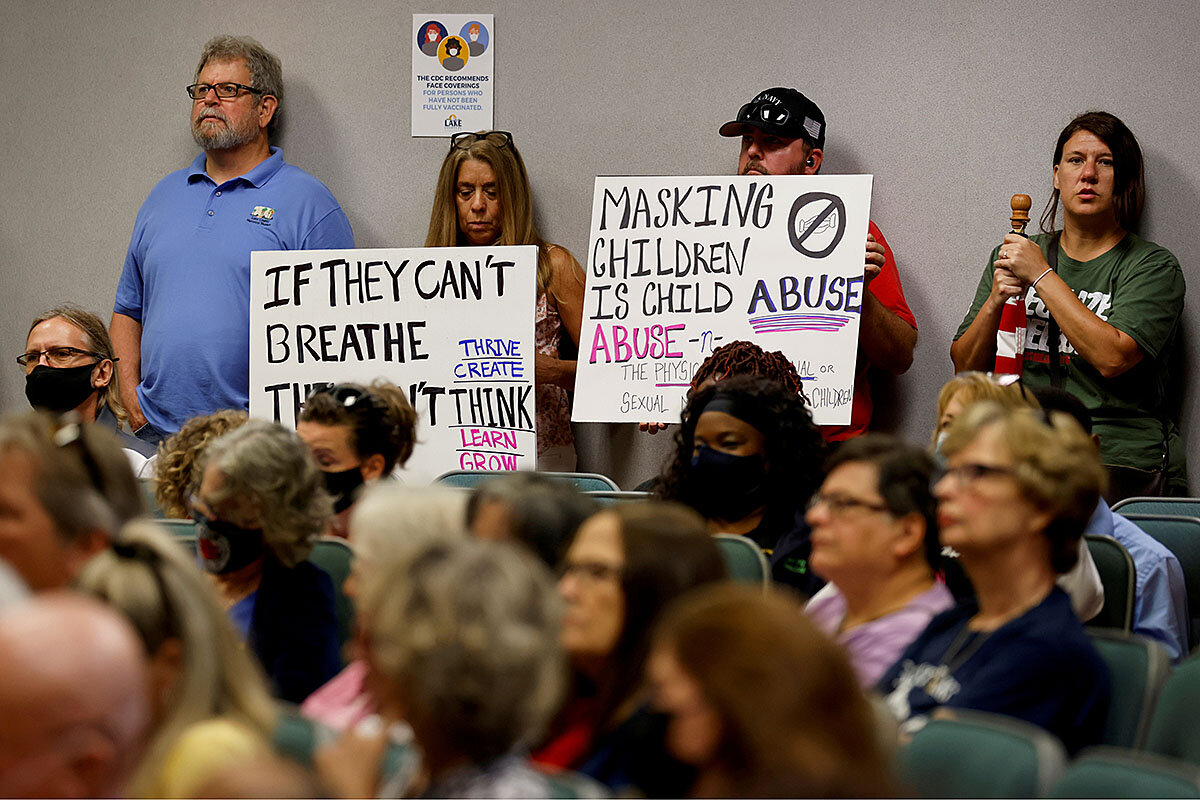

Democrats and Republicans vie to be ‘the party of parents’

Amid a pandemic and a racial reckoning, American parents are rethinking the role government plays in their children’s education, health, and opportunities. Both parties are striving to tap into that.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

What do parents want?

That question is top of mind for both parties on Capitol Hill in the wake of the GOP’s strong showing in state elections this week, which hinged in part on parents’ desire to have more authority over critical decisions in their children’s lives, including what they learn in school.

“Parents brought real energy in Virginia and we would be wise to listen and seek to understand their concerns,” GOP Rep. Jim Banks wrote in a strategy memo, arguing that Republican Glenn Youngkin’s success in winning Virginia’s governor race “reveals that Republicans can and must become the party of parents.”

Not if Democrats have anything to say about it. They are touting their Build Back Better Act, which would extend enhanced child tax credits, subsidize child care for lower-income families, make public pre-K universal, and help parents sidelined by the pandemic get back to work.

“It’s about the children, about their parents,” said House Speaker Nancy Pelosi on Thursday. When asked when she expects to hold a vote, she said, “I’ll let you know as soon as I” – and she paused – “wish to.”

Democrats and Republicans vie to be ‘the party of parents’

What do parents want?

That question is urgently top of mind for both Democrats and Republicans on Capitol Hill in the wake of Tuesday’s elections. Just one year after President Joe Biden won Virginia by 10 points, the GOP captured the governor’s seat there and nearly upset Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy in deep-blue New Jersey – in part by tapping into parental anger over education policy, and promising to give parents more authority over critical decisions in their children’s lives.

Democratic leaders, who were unable to pass two key bills last week that many thought would have helped the party on Election Day, are pushing hard to get them across the finish line and shut down Republican efforts to brand themselves as “the party of parents.” They are emphasizing the many measures in the president’s Build Back Better bill aimed directly at families – including an extension of enhanced child tax credits, subsidized child care for lower-income families, and universal pre-K.

“It’s about the children, about their parents,” said Speaker Nancy Pelosi on Thursday, noting that a month of paid family and medical leave – an issue particularly important to her as a mother who gave birth to five children in six years – has now been added back to the bill after being cut for cost reasons.

“Our belief is that when you invest in people early – whether it’s pre-K, whether it’s paid leave, whether it’s education – you are helping them to become fully self-sufficient,” says Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Washington, the chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus.

But Republicans, basking in wins from Virginia to New Jersey to Seattle, say Democrats are failing to heed the lesson of Tuesday’s results: that their sweeping social reforms are not resonating with the needs and concerns of American parents. They chastised Democrats for pushing the U.S. attorney general and FBI to monitor school board meetings, which have seen heated debates over COVID-19 regulations and curriculum changes surrounding race and identity. They also argue the proposed expansions to the social safety net will end up hurting parents financially, by driving up the cost of everything from gas to groceries to winter heating bills.

The GOP is already looking to replicate Virginia Gov.-elect Glenn Youngkin’s parent-focused campaign in races across the country as it looks to 2022, with House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy promising to soon unveil a “parents’ bill of rights.”

“Youngkin’s success reveals that Republicans can and must become the party of parents,” wrote Indiana Rep. Jim Banks, chairman of the largest conservative GOP caucus in the House, in a memo to his members. “Parents brought real energy in Virginia and we would be wise to listen and seek to understand their concerns.”

How best to help parents, children

At the heart of the debate is a fundamental difference in the parties’ views about the role of government. In recent decades, Democrats have worked to create a more robust social safety net, pointing out that America lags far behind other developed nations in that regard. They argue that at a time of vast income inequality – which has been exacerbated by a pandemic that disproportionately hurt the working class – more government support is needed to ensure that every child has an equal chance to succeed.

“We are a nation that underinvests in our children. We have an opportunity now to do a whole lot better,” says Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who has recounted how she was only able to launch a promising law career because her aunt came to be her children’s live-in caregiver for 16 years.

“We’re trying to make an investment in children, and make it possible for parents to be able to work, to finish an education, to start a small business – but that takes a bigger infrastructure,” she says. “We have tried the Republican approach for far too long, and we have too many children in poverty in the richest nation on earth. And that’s fundamentally wrong.”

Republicans see such government programs as inefficient, susceptible to exploitation, and eroding the role of faith-based institutions in supporting those in need. They blame government benefits for creating a dependency that undermines the dignity of individuals and disincentivizes work and marriage. They also argue that things like education and child care are best addressed at the local level, rather than by a federal government that may be thousands of miles removed and is unable to pinpoint the most effective or cost-efficient approach.

Democrats often criticize that as a do-nothing approach that lacks compassion for the struggles of working- and middle-class families. But Republicans say they have more faith in individuals than in a federal bureaucracy to meet the needs of those struggling and that the role of government is to empower them to do so – in part by staying out of their way.

“I find that the government’s far less compassionate than the church, and in some situations, I think, compassion that comes from people of faith is oftentimes overlooked by our own government, particularly in recent years,” says GOP Sen. Kevin Cramer of North Dakota, who sits on the Senate Budget Committee chaired by Sen. Bernie Sanders. “You’ve seen an increase in the government taking care of people and a decrease in the church taking care of those same people, either out of necessity or discouragement.”

The question of work requirements

These ideological differences have come to a head over Democrats’ proposed reforms that would delink a work requirement from certain benefits, including for children. Republicans say Democrats are exploiting the pandemic to push through permanent changes that would foster greater dependence on government. One key area of disagreement is a plan for the IRS to send monthly child tax credits to parents through direct deposit or money on a debit card, without the sort of face-to-face meetings that used to be part of such benefit programs and could bring to light other issues, such as unpaid child support or domestic violence, so that they could be addressed.

“President Biden and the Democrats are weaponizing the temporary COVID relief as a back door to create permanent new welfare-without-work programs that foster greater dependence on government and pay people more to stay at home,” said Rep. Jackie Walorski of Indiana, a member of the House Ways and Means Committee.

A nonpartisan congressional study found that work requirements could improve incomes and financial stability in some cases, but the effectiveness of such measures varied significantly based on the type of benefit and whom it aimed to help.

Democrats say that the Build Back Better bill includes numerous provisions to support greater workforce participation, and argue that work requirements create an undue administrative burden – adding to the administrative cost of the programs and preventing struggling Americans from getting the help they need in a timely way.

“Most people, the vast majority of people, are trying to do the best for themselves and for their families, and very much want to be independent – that’s my fundamental belief,” says Representative Jayapal. “So we should try to make benefits as universal as possible, make them as easy as possible, not saddle them up with a bunch of work requirements and other things that prevent the most vulnerable from actually getting the benefit.”

Representative Jayapal has taken a strong stance for ensuring that progressive priorities are included in the Build Back Better Act, and has repeatedly said in recent weeks that her 96-member caucus would not vote for a related bipartisan infrastructure bill until those priorities were agreed to not only by House Democrats but also by all 50 Democratic senators.

Speaker Pelosi has twice been forced to delay a vote on both bills due to progressives holding out for a better deal. Now, some moderates are demanding an assessment from the Congressional Budget Office that the bill really will be paid for through new taxes and stepped-up enforcement for corporations and wealthy individuals. That would take an estimated two weeks.

The speaker said Thursday morning that the nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation had just determined that the bill would indeed be paid for. But when asked about when she expects to hold a vote, she said, “I’ll let you know as soon as I” – and she paused – “wish to.”

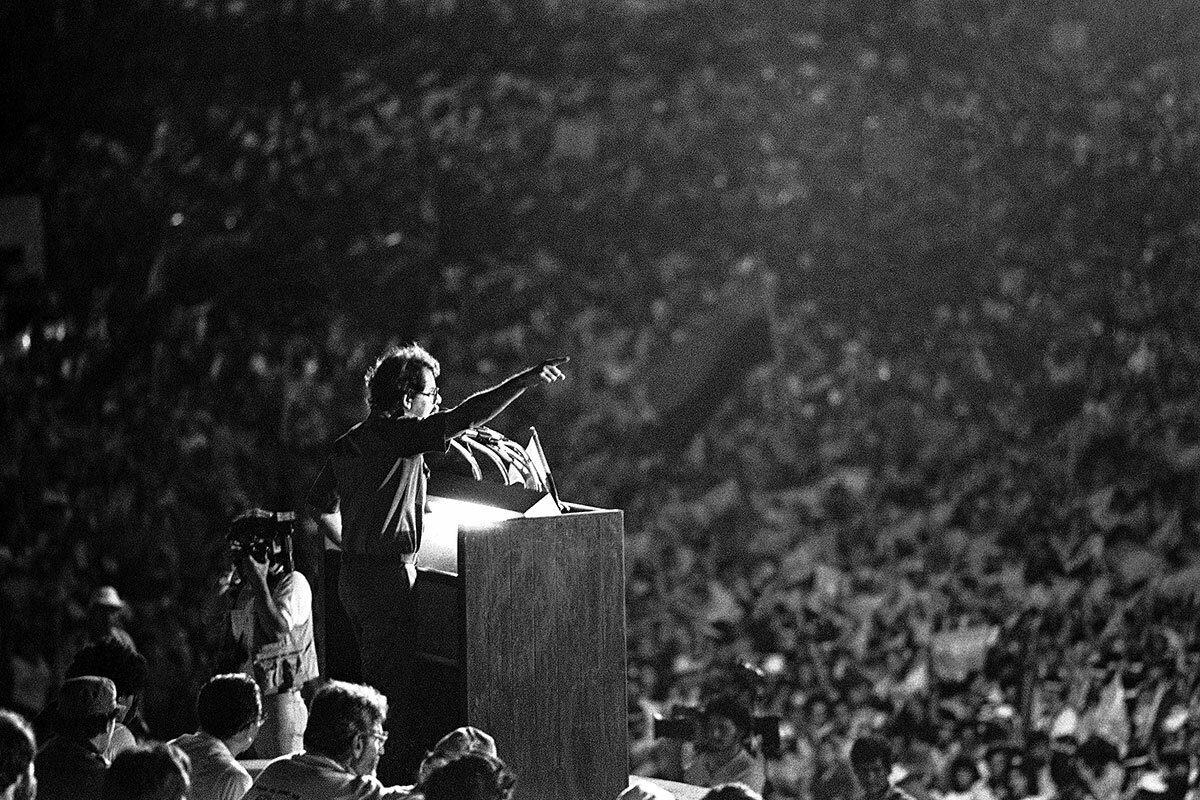

An election in Nicaragua that could further dim democracy

Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega has in many ways become the dictator he once toppled. That presents a crucial test for a region always flirting with authoritarianism.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By a correspondent

Daniel Ortega was once a beacon for the international left. The former guerrilla fighter helped topple a dictatorship in Nicaragua and vowed to free the people from the shackles of a corrupt dynasty.

Now he lives lavishly and has kept a firm grip on power, becoming the dictatorial force he once stamped out. As the nation heads to the polls on Nov. 7, he has imprisoned his political rivals and refused to allow election observers and the foreign press corps to bear witness to the race.

This election marks a watershed moment for the country, not because of the outcome but for where Nicaragua goes next. The opposition and international community face the task of reestablishing democracy here, and the stakes are high. Just as the Sandinistas inspired a generation of revolutionary leaders in the 1980s, today’s FSLN could embolden authoritarianism in the region.

“Unlevel playing fields are common in Latin America, but still not to this level,” says Tiziano Breda, Central America analyst for the International Crisis Group. “There is not even a playing field.”

“If there is no robust and coordinated response,” he adds, “it will set a dangerous precedent for the region where other authoritarian wannabes are not lacking.”

An election in Nicaragua that could further dim democracy

Under the wing of Daniel Ortega, Nicaragua buzzed with revolutionary promise at the height of the Cold War.

The former guerrilla fighter and his Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) toppled the Somoza dictatorship in 1979, and won presidential elections five years later – bringing democracy to the Central American nation. At the time, foreign journalists flocked to Managua to cover the historic transition.

Forty years later, Mr. Ortega leads Nicaraguans to the polls once again. But there is no international press corps here now. There are no rivals either.

Even before Nicaraguans vote Nov. 7, the results are already clear: Mr. Ortega is running essentially uncontested for his fourth consecutive presidential term after an unprecedented crackdown on opposition candidates and press freedom this summer.

This race marks a watershed moment for the country, not because of the outcome but for where Nicaragua goes next. The opposition and international community face the task of reestablishing democracy here, and the stakes are high. Just as the Sandinistas inspired a generation of revolutionary leaders in the 1980s, today’s FSLN could embolden authoritarianism in the region.

“Unlevel playing fields are common in Latin America, but still not to this level,” says Tiziano Breda, Central America analyst for the International Crisis Group. “There is not even a playing field.”

“If there is no robust and coordinated response,” he adds, “it will set a dangerous precedent for the region where other authoritarian wannabes are not lacking.”

“Nothing Sandinista left”

Once a beacon for the left, Mr. Ortega has moved far from those ideals. He once vowed to free Nicaragua from the shackles of a corrupt dynasty that funded its lavish lifestyle at the expense of poor Nicaraguans. Now, he lives as lavishly and has appointed his family to top leadership posts, including his wife, Rosario Murillo, who is vice president. Nicaragua remains the second-poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere.

Since first returning to power in 2006 elections, Mr. Ortega has reformed the constitution to allow reelection and stacked the judicial system with loyalists. When he faced a mass anti-government protest movement in 2018, he sent police to violently repress it. International human rights groups call that crackdown a crime against humanity.

It was also a betrayal of the 1979 revolution, says Gioconda Belli, a prominent Nicaraguan poet who worked clandestinely for the Sandinistas before the revolution and supported them enthusiastically in the early days of their rule. “It was an anti-dictatorial movement,” she points out. “We fought against a 45-year-old dictatorship, so to go back to dictatorship [means] there is nothing Sandinista left.”

Despite ongoing repression, a coalition of opposition organizations came together in 2018 to form a front they named Blue & White National Unity (UNAB), hoping to defeat Mr. Ortega and return Nicaragua to democratic rule.

“We saw a small window of opportunity for Nicaraguan citizens to elect new authorities, even in such adverse conditions,” says Alexa Zamora, a member of the political council of UNAB who is now in exile. But the window quickly shut on them.

In June, the government placed under house arrest leading rival Cristiana Chamorro – daughter of former President Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, who defeated Mr. Ortega in 1990 elections – on charges of money laundering, which she denies. Within weeks, the remaining six contenders were imprisoned under a law passed in December 2020 criminalizing “traitors.” That has left just five other candidates – all considered Ortega loyalists – on the ballot.

An October CID Gallup poll showed only 19% of Nicaraguans planned to vote for Mr. Ortega, compared with 65% who supported an imprisoned opposition candidate.

A chilling effect

Mr. Ortega’s crackdown reaches beyond the political world. As of Nov. 4, the government had arrested 39 people, including Francisco Aguirre-Sacasa, former Nicaraguan ambassador to the United States who spoke critically of the government after the 2018 crisis but toned down his comments before elections. “My father’s retired from politics,” his daughter Georgie Aguirre-Sacasa says. “He’s a horse farmer and a grandfather. He is not a spy or whatever they are claiming he is.”

The Ortega-Murillo government has justified its actions as necessary to defend the country against “foreign interference.” In a June speech, Mr. Ortega condemned “false narratives espoused by right-wing media and U.S.-funded ‘opposition figures.’”

In July, Nicaragua’s Supreme Electoral Council announced it would not allow electoral observers. At least a dozen foreign reporters have been denied entry or never received a response to a request for a journalist’s visa, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

The government wants an “information blackout,” says Cindy Regidor, a Nicaraguan journalist with independent media outlet Confidencial who is now living in Costa Rica. Police harass and confiscate equipment from journalists working in the field, and public prosecutors have called journalists in for questioning so as to intimidate them, she says. “What exists in Nicaragua is a regime that now uses judicial persecution against anyone they consider an adversary, including journalists.”

That tactic has had a chilling effect on political debate. “There’s a lot of fear in Nicaragua – fear of repression, of arbitrary detentions, and of criminal charges for crimes against national integrity,” says a UNAB member who asked not to be identified to ensure their security.

A path forward

Ortega’s “virtual beheading of any slight electoral challenge” is incomparable to any elections in Latin America since the region’s transition to democracy after military dictatorships in the 1980s, says Mr. Breda. Even in Venezuela some participation by rival candidates has been allowed; the opposition won control of Congress in 2015.

And that’s why the international community must mobilize, he says.

With the election outcome certain, UNAB has launched a campaign called “Let’s Stay at Home” urging Nicaraguans to refrain from the Nov. 7 vote and calling on the international community to reject the outcome and demand another race.

The actions of the regional Organization of American States, which issued a resolution on Oct. 20 calling for the release of political prisoners and respect for free elections, will be crucial to set the tone of the international response, UNAB says.

The U.S. Senate this week passed the Renacer Act, which calls for restrictions on the Nicaraguan government’s access to international funding and sanctions on officials involved in attacks on democracy and human rights abuses. Mr. Breda says the international community must coordinate condemnations and sanctions after the elections.

UNAB leaders say they hope to establish dialogue with the government. But first, they insist that all political prisoners must be freed.

They know reestablishing democracy will likely be a yearslong process – and they aim for it to be peaceful, unlike the armed resistance Mr. Ortega once waged, says Ms. Zamora.

“Nicaraguan citizens have chosen the civic and pacific route,” she says, “as the only route out of this socioeconomic crisis.”

We are withholding the byline on this article in order to ensure the author’s security.

The Explainer

Europe plans border tax on carbon. Will others join the club?

The COP26 global climate summit is, by design, about bargaining and voluntary steps, not mandates and penalties. But Europe is poised to add a tough-love tactic on the side. Will it help?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

What happens when one trading power is trying to drive down carbon emissions, and other nations aren’t moving so fast? That’s a hot question for the European Union, which makes its heavily polluting industries pay for their pollution while many other countries don’t.

Leaders in the EU have long argued that it’s time to level the playing field. Now they have a plan to use their market power to bring others into line. The penalties they envision might have a side benefit for Earth’s climate by nudging other countries to ratchet down their own emissions.

A key goal is to fix what is now a “leaky” system. Inside the EU, there’s a robust carbon market with rules and prices that push industries to reduce pollution. But goods imported from outside don’t typically face such constraints.

The EU’s proposed answer is a carbon border adjustment mechanism, effectively an import levy on carbon-intensive products. It could incentivize companies to invest more in green technologies, both in Europe and overseas. And the EU may bring others along later, creating a club of economies aligned to curb the buildup of heat-trapping gases in Earth’s atmosphere.

Europe plans border tax on carbon. Will others join the club?

What happens when one trading power is trying to drive down carbon emissions, and other nations aren’t moving so fast? That’s a hot question for the European Union, which makes its heavily polluting industries pay for their pollution while many other countries don’t.

Leaders in the EU have long argued that it’s time to level the playing field. Now they have a plan to use their market power to bring others into line.

The penalties they envision might have a side benefit for Earth’s climate by nudging other countries to ratchet down their own emissions.

A key goal is to fix what is now a “leaky” system. Inside the EU, there’s a robust carbon market with rules and prices that push industries to reduce pollution. But goods imported from outside don’t typically face such constraints.

The EU’s proposed answer is a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), effectively an import levy on carbon-intensive products. The proposal, released in July, forms part of a strategy to cut EU-wide emissions 55% by 2030. The goal is to incentivize companies to invest more in green technologies, both in Europe and overseas, by driving up the cost of polluting.

It’s an idea to drive market-based carbon accountability that could someday reach far beyond Europe. John Kerry, the White House special climate envoy, has said President Joe Biden wants to evaluate Europe’s CBAM and that the United States could deploy its own border adjustment tax.

By going first, the EU may bring others along later, creating a club of developed economies that put a price on carbon and penalizing those that don’t. That would speed up the clean energy transition that is essential to break the buildup of heat-trapping gases in Earth’s atmosphere.

“There are a lot of people who see this as a way to build coordination among like-minded nations with similar levels of ambition who are ready to play by similar rules,” says Christopher Kardish, an adviser to Adelphi, an environmental consultancy in Berlin.

Such a club would reside outside the consensus-based, voluntary process at the United Nations climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland. Yet the CBAM is certain to be discussed on the sidelines, particularly between EU members and their trading partners.

What exactly is the EU proposing to do?

From 2023, EU importers of industrial products such as steel, aluminum, and cement would start assessing and reporting their imports’ overseas carbon footprint: put simply, how much carbon was emitted to make the product. The next step in 2026 would be to tax the emitted carbon under the market price in Europe that domestic producers must pay.

The idea is to prevent leakage, whereby strict standards in one jurisdiction cause production to shift to places with laxer rules. Already, around one-quarter of Europe’s emissions are embedded in the goods it imports, according to a study by the Boston Consulting Group.

“More emissions are occurring in other countries to meet the demand [in Europe] for consumer goods,” says Michael Mehling, deputy director of the Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He notes that Switzerland now imports more embedded emissions in goods than it emits domestically.

And European companies that are paying higher prices for carbon permits – hitting $70 per ton in October – don’t want to be at a competitive disadvantage to imports, says Mr. Kardish. “They’re facing a real bite in a world where they’re the only ones pricing carbon at that level,” he says.

Crucially, imports into Europe from countries that also price carbon would benefit under a CBAM. That’s because importers of steel, for example, made in California, one of several U.S. states that operate carbon markets, could deduct what was already paid there. Importers from countries that don’t tax carbon, however, would pay the full amount.

What are the implications for international trade?

Europe’s CBAM could transform the market for carbon-intensive products. It may also help to turbocharge investment and innovation in greener ways of producing those products, either in Europe or other regions that run carbon markets. By contrast, countries that don’t tax carbon would be at a disadvantage in selling into the world’s richest economic bloc.

Some critics question whether the CBAM is compatible with international trade rules, or represents a form of protectionism.

At the very least, a thorny question for EU regulators is what to do about countries that have policies to curb emissions, such as clean energy standards, but don’t put a price on carbon. In 2010, a bill to create a federal emissions-trading system like Europe’s failed to pass the U.S. Congress, and proposals to include a carbon tax in the Democratic social spending bill were dropped.

“If it’s not an explicit price, either from a tax or a mandatory carbon market like California has, it’s not going to be a cost that can be counted” toward paying a border tax, predicts Mr. Kardish.

While many countries have introduced carbon markets, most emissions aren’t subject to caps and prices vary greatly. Studies have shown that only when carbon prices are sufficiently high do they lead to changes in investment and production that lower emissions. Around 16% of all greenhouse gas emissions are currently covered by carbon markets.

Could this be the basis of a new global approach to climate?

A European border tax that recognizes other countries’ emission markets would be a step toward creating a carbon-pricing club that runs parallel to U.N.-brokered emissions cuts. Proponents say this club could raise the climate ambition of other countries that aspire to join and funnel more investment into renewable energy to produce tradable goods.

By penalizing countries that don’t put a price on carbon, though, an EU-led club could undercut the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, which 197 countries have signed and is the basis of the 2015 Paris accord. Under that accord, countries effectively chose their own speed to cut emissions and build a low-carbon economy.

Absent U.S. support, there may be doubts about the long-term effectiveness of such a club. Another question is how the EU cooperates with China, which recently launched an emissions trading market that only covers domestic power generators. Many wonder if China would want to join a club in which EU regulators are determining the basis of carbon pricing.

Such doubts won’t stop European policymakers from rolling out a CBAM, says Mr. Mehling, who notes that Germany’s incoming coalition government is bound to be supportive. “It’s popular and populist: ‘We’re doing what you elected us to do and we will hit anyone outside the country that’s trying to undermine it,’” he says.

Film

‘Nomadland’ director brings her vision to Marvel’s ‘Eternals’

If Oscar winner Chloé Zhao pivots from her indie roots to make a big-budget Marvel film like “Eternals,” does it make her a sellout? The Monitor’s film critic weighs in on that – and the new movie.

-

By Peter Rainer Special correspondent

‘Nomadland’ director brings her vision to Marvel’s ‘Eternals’

The director of “Eternals,” the new Marvel extravaganza, is none other than Chloé Zhao, the indie auteur whose last film was the microbudgeted “Nomadland.” The road movie about rural itinerants won Oscars for both best picture and director, and for star Frances McDormand. In style and substance, I can’t think of two more disparate films. Unlike some of my colleagues, however, I don’t regard Zhao’s Marvel makeover as a simple case of selling out. But before I elaborate on that, here’s a more pressing question: Is the film any good?

I’m not a big Marvel person, but I recognize the need for these films to exist; they’re the cinematic equivalent of the circus coming to town. A few of them, such as “Iron Man,” “Black Panther,” and “Avengers: Endgame,” were good. “Eternals” is subpar in comparison. It comes across like the B side to the “Avengers” movies, with almost none of their star power or CGI pizazz.

The Eternals are shadow warriors sent to Earth thousands of years ago to save it from the monstrous Deviants, who resemble befanged supersize renegades from “A Quiet Place.” Thanks to the Eternals, earthlings have never heard of Deviants but, alas, they’ve returned – after 500 years – more ferocious than ever.

The Eternals include Sersi (Gemma Chan), first seen in modern-day London and looking happily human paired with her earthly lover (Kit Harington). Her Eternals lover, Ikaris (Richard Madden), with whom she has had an off-and-on romance for millennia, suddenly shows up to complicate matters. He and the other superheroes, scattered around the globe in their various guises, are roused to once again decimate the Deviants.

It’s noteworthy that the Eternals are, by Hollywood superhero standards, remarkably diverse, with several other Asian actors besides Chan – including Don Lee’s rollicky Gilgamesh and Kumail Nanjiani’s wisecracking Bollywood heartthrob Kingo – in starring roles. Brian Tyree Henry’s genius inventor Phastos not only is an openly gay Black man but also is married and a father. Lauren Ridloff, who is deaf, plays the deaf speedster Makkari.

But, except for Angelina Jolie, who plays the warrior Thena, none of the film’s performers is especially luminescent. Even Jolie, in her too-brief role, seems a bit distracted. She periodically goes murderously rogue against her helpmates, which turns out to be more tiresome than thrilling. Even if Zhao and her co-screenwriters were more adept at establishing the family-style togetherness of the Eternals, the emotional continuity is shattered by the incessant time tripping and globe hopping. Just when you think you’ve got your bearings in South Dakota, you suddenly find yourself in Mesopotamia.

Still, I don’t think Zhao should be chided for attempting a film so seemingly outside her comfort zone. (She has professed a love of manga.) No director – least of all a female director, for whom job opportunities are particularly unplentiful – should have to commit to a career of specialization. The only qualm I have about “Eternals” is that it’s not better. (And, for the record, I was mixed on “Nomadland” and her earlier indies.)

Is Zhao perhaps the victim of a double standard? There was no big selling-out hoo-ha when Ryan Coogler, who made his name with the powerful indie “Fruitvale Station,” graduated to “Creed” and “Black Panther.” The combined budgets of Christopher Nolan’s first two films, “Following” and “Memento,” wouldn’t pay for the caterer on his “Batman Begins.”

It’s also quite possible to achieve moments of emotional intensity in superhero movies matching anything in the indie realm. Case in point: Tony Stark’s death scene in “Avengers: Endgame,” which features Robert Downey Jr. at his most moving. In an ideal world, I would wish for filmmakers to mix it up micro and macro, the way, say, Steven Soderbergh does. But that’s just me. If indie filmmakers want to exit the byways and enter the circus tent, there will be others to take their place. In the end, the only thing that really matters is that the movies be good.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “Eternals” is rated PG-13 for fantasy violence and action, some language, and brief sexuality.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

In Israel, Arab magnanimity toward another minority

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In the Middle East, moments of bridge building between adversaries are always worth noting, especially if the bridge is built on empathy.

On Tuesday, the leader of Israel’s minority Arabs made an unexpected gesture toward another minority. Mansour Abbas of the Raam party said he had asked the government to give a portion of $9.4 billion slated for Israeli Arabs to the ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities, or the Haredim.

“We prefer to use the money for things which are important to us. That would include friends,” he told Kan Bet media, citing a wish for the two minorities to get along. He said he was moved by a recent speech in parliament by Moshe Gafni of the United Torah Judaism party about hardships in the Haredim and the need for “weaker” parts of Israeli society to band together.

Politics in a democracy do not always have to be zero-sum battles or even a transactional splitting of differences. Often it is minorities who, out of shared suffering from being on the outside looking in, develop empathy to alleviate the misery of others.

Bridge building starts with cornerstones of listening, especially to those on the margins.

In Israel, Arab magnanimity toward another minority

In the Middle East, moments of bridge building between adversaries are always worth noting, especially if the bridge is built on empathy.

On Tuesday, the leader of Israel’s minority Arabs made an unexpected gesture toward another minority. Mansour Abbas of the Raam party said he had asked the government to give a portion of $9.4 billion slated for Israeli Arabs to the ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities, or the Haredim.

“We prefer to use the money for things which are important to us. That would include friends,” he told Kan Bet media, citing a wish for the two minorities to get along. He said he was moved by a recent speech in parliament by Moshe Gafni of the United Torah Judaism party about hardships in the Haredim and the need for “weaker” parts of Israeli society to band together.

Mr. Abbas’ conciliatory request to share money due for his own community “makes him among the most refreshing figures on the Israeli political scene,” wrote The Jerusalem Post, adding that the gesture is “magnanimous,” a quality often lacking among parties that “view one another as mortal enemies.” (Many Israelis refer to Arabs living within Israel proper as Palestinians.)

Perhaps the gesture was made easier because Israel has enjoyed five months of governance under a rare ruling coalition of Jewish parties from the right and left as well as Raam, the first time that an Arab party has been part of a coalition. The Jewish politician who put the diverse coalition together, Yair Lapid, says its main purpose is to “find the shared good.” The government has been able to agree on a budget for the first time since 2019.

Politics in a democracy do not always have to be zero-sum battles or even a transactional splitting of differences. Often it is minorities who, out of shared suffering from being on the outside looking in, develop empathy to alleviate the misery of others. That can change the narrative from simply winning political contests toward one with a mutual vision for society.

Bridge building starts with cornerstones of listening, especially to those on the margins.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The bedrock of meaningful relationships

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karyn Mandan

How can we navigate relationships with wisdom, joy, and harmony? Starting from a spiritual standpoint – recognizing our unity with God – offers a rock-solid foundation.

The bedrock of meaningful relationships

A visitor to Boston’s dense residential and commercial district known as Back Bay might be surprised to learn they are standing right where ocean water used to be – and water still ebbs and flows beneath the filled land. The fill is unstable, so many building foundations have been anchored by piles that were driven through the sand, dirt, and water into more stable ground – in some cases, all the way down to the bedrock.

To me, this is a useful metaphor for building lasting relationships, too! I’ve found that when our values are secured on a spiritual foundation, then life-enriching relationships stand more solidly.

At one point years ago, I was living far from family and aching with loneliness. My new job was demanding, and I hadn’t yet formed meaningful friendships.

And then I met a guy. Oh gosh, he was fun and exciting, and – pinch myself – he wanted to be with me! The early days of our friendship were wonderful as we got to know each other. I was swept up in the newness and excitement, and I totally forgot about being lonely.

But as the relationship progressed, different expectations of each other emerged. It became clear that we weren’t in agreement in some key ways, including how the relationship would develop. I felt pressured to yield to his expectations. But what about mine? I was afraid to lose the relationship, but was it worth compromising what was important to me? The inner conflict became unbearable.

Whenever I am confused about direction in my life, I pray for clarity from God, the divine source of intelligence. Christian Science teaches that there is no confusion or instability in the unbreakable relation we each have to God, our heavenly Father-Mother, divine Love. Each of us stands safe and secure as God’s spiritual, loved offspring.

That’s when an image of one of the historic churches in Back Bay came to thought. Soaring beautifully in the sky, it appears to get its stability from the visible ground. But I knew it was constructed on piles that were anchored much deeper than outward appearances.

I asked myself, What was the bedrock of this relationship? And what anchors me throughout the ebbs and flows of life? Am I looking exclusively to a person for security and happiness, or am I relying on a firm foundation of divine wisdom?

In Christ Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, he illustrated the effects of constructing one’s house – a metaphor for life – either on sand or on rock (see Matthew 7:24-27). Building on sand represents hearing Christ’s healing message of God’s love and goodness and immediately forgetting about it, which leaves one vulnerable to life’s storms. Building on the rock – accepting and humbly conforming to our unity with God – ensures greater stability in both storm and sunshine.

As I thought deeply about this, there was no doubt in my mind that I wanted to build on the rock, harmonizing my life with God. I saw that God expresses in each of us spiritual qualities such as integrity, kindness, generosity, and unselfishness. This is our true, spiritual identity as God’s children, the bedrock of being that secures every relationship and nurtures a companionship that benefits both individuals. So, these God-given attributes could no more be compromised in me than in divinity!

Moreover, adhering to my God-derived individuality wouldn’t deprive me of good, as I’d earlier feared. It would free me to build a life of genuine happiness in healthy, harmonious concord with others.

A calm consciousness of God’s ever-presence came over me. For the first time in months, I felt safe, cared for, and deeply loved – without limits. And I knew that God always provides all that is needed, including wisdom, compassion, and confidence in navigating relationships. I was completely at peace.

Shortly after this awakening, my friend and I parted respectfully, each moving on in productive, fresh ways. In my case, this included a new and rewarding work assignment in Southeast Asia a few months later, where I developed new and lasting friendships.

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, describes the nature of fulfilling companionship based on a solid, life-enriching, divine foundation: “Happiness is spiritual, born of Truth and Love. It is unselfish; therefore it cannot exist alone, but requires all mankind to share it” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 57). When letting the wisdom of divine Truth and Love ground us, we – and those we interact with – are blessed.

A message of love

Posing, with puppies

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we look at a different kind of worker shortage. Many youth sports officials are not coming back from the pandemic hiatus, partly because of the increasingly abusive behavior directed at them from fans, especially parents. What are players learning about sportsmanship, and what’s being done to address the problem?