- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Why abortion fight isn’t over if Roe is overturned

- Libya elections: Can internal conflict move from bullets to ballots?

- Civil debate about education? Two opponents offer a blueprint.

- Not just another lizard: Peruvian beauty offers extinction counternarrative

- Boxing and talking: How a 1988 Olympian gives back

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Reporters on the Job: What I learned from the cats of Parque Kennedy

Howard LaFranchi

Howard LaFranchi

We hear a lot these days about emotional support animals. The concept of therapeutic pets is so prevalent that these canine or feline (or other) friends have their own acronym: ESA.

While on a reporting trip to South America, I found a posse of my own personal ESAs in the cats of Parque Kennedy in Lima, Peru.

I had been reporting in Peru – including today’s story on biodiversity – and was set to move on to Santiago, Chile. I had done everything necessary to meet Chile’s pandemic requirements for entering foreigners, but there was a catch: The entering foreigner needed an official response that a submitted proof of vaccination was approved by the Chilean Ministry of Health. But day after day, my electronic file said “case pending.”

My flight left without me. My negative COVID-19 test expired. I had no way of knowing when approval would arrive.

This is where the cats enter the story. Needing to think about something other than my predicament, I walked from my hotel to Parque Kennedy, a favorite spot for families. I sat on a park bench, and before long I noticed a cat. And then another cat. And then another.

Turns out they were the famous cats of Parque Kennedy. (Two Facebook pages, one in English, one in Spanish. Many media appearances, including on the BBC.) The formerly homeless cats are cared for by the dedicated Voluntary Group of Feline Defenders of Miraflores Park.

But what I saw in those cats that day – and on subsequent visits – was a reassuring calmness that seemed to say, “Take it from me, it’s going to be OK.” I took solace in the sense of trust they displayed, allowing strangers like me, and even jumpy children, to pet them or scratch them behind the ear.

So thanks, cats of Parque Kennedy, for becoming for a few brief moments my ESAs.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

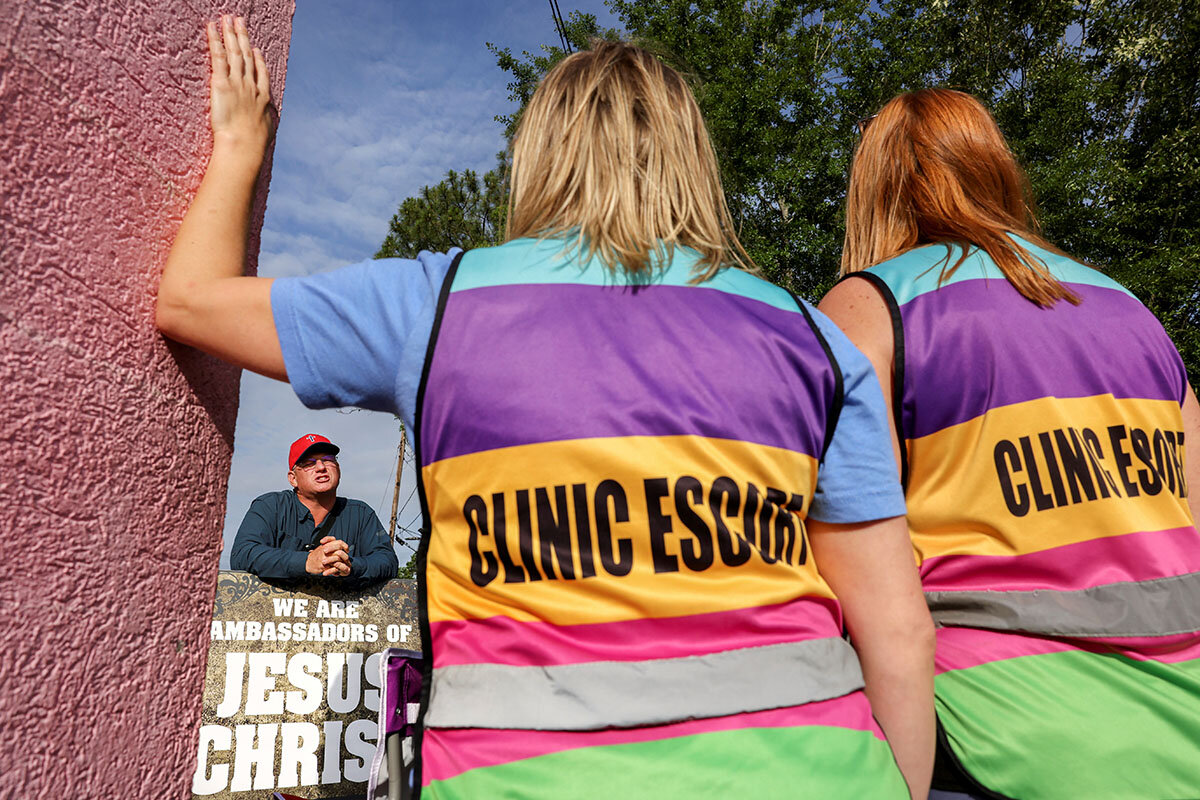

Why abortion fight isn’t over if Roe is overturned

In the rare instances the Supreme Court has overturned a constitutional precedent, it has typically been to expand, not revoke, a right. That may be changing for abortion rights, and states and their constitutions could find themselves even fiercer battlegrounds.

Vermont and Kansas offer a glimpse of the future abortion rights could face post-Roe.

Two years ago, Kansas’ Supreme Court ruled that its constitution protects a woman’s reproductive rights. State Sen. Molly Baumgardner, an abortion foe, began pushing for a constitutional amendment that would remove that right in the state.

It passed the statehouse earlier this year. Next August, Kansans will vote whether to ratify it.

Meanwhile, Vermont state Sen. Virginia Lyons is leading the campaign in her state to become the first in the country to enshrine abortion rights in its state constitution.

For the first time in decades, the federal right to abortion faces an existential threat. On Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear a case challenging a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. If the conservative supermajority votes to substantially weaken or overturn Roe v. Wade, the result will move the culture war to the states, and their constitutions.

State constitutions “are more responsive to popular pressure and democracy. Majorities get their say,” says Emily Zackin, author of “Looking for Rights in All the Wrong Places.” But if you want certain rights protected from majoritarian influence, as America’s founders did, she continues, “a state constitution can’t do that as well.”

Why abortion fight isn’t over if Roe is overturned

Virginia Lyons has served two decades as a state senator in Vermont. For 18 of those years, she was happy with how accessible abortion services were in the state.

Now she wants to go a step further and amend the state constitution.

Abortion access is relatively unfettered in the liberal state. But after watching Republican President Donald Trump get elected in 2016, and then solidify a conservative supermajority on the U.S. Supreme Court by appointing three new justices, she thought the state needed to do more.

Her proposed amendment – which must be passed by the statehouse before going on a statewide ballot next year – would enshrine a constitutional right to abortion in the state. Vermont would become the first state to do so.

“We can all see the writing on the wall,” says Senator Lyons.

Since the Supreme Court recognized a constitutional right to abortion with its 1973 opinion in Roe v. Wade, there’s been a “continued undermining” of the right, she adds, with federal courts permitting states to slowly but steadily restrict access to abortion.

“So I felt that it was critically important to introduce this [amendment], and move the decision-making from law to constitution,” she continues.

For the first time in decades, the federal right to abortion faces an existential threat. On Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear a case challenging a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. The law violates high court precedents protecting the right to abortion before fetal viability, generally considered around 24 weeks. But the justices have asked to hear arguments on “whether all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are unconstitutional,” suggesting a majority of justices may be willing to further narrow – or perhaps even overturn – the federal right to abortion.

That’s just one of several potential outcomes in the case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health. In the rare instances the court has overturned a constitutional precedent, it has typically been to expand, not revoke, a right.

Overturning Roe would not criminalize abortion nationwide; it would just make it constitutional for states to do so if they choose. Many would. But with the U.S. Constitution supreme only when it conflicts directly with state constitutions, states would then become the surest method of protecting – or restricting – abortion rights.

In essence, a previously universal and inalienable right would become a location-dependent one. And although state governments are increasingly dominated by one party, without federal constitutional protection the abortion rights debate would inject a polarizing issue into the hitherto low-profile – but relatively volatile and unpredictable – landscape of state constitutional law.

“There would be a much greater degree of political uncertainty,” says Justin Long, an associate professor of law at Wayne State University in Michigan. “What rights exist and what don’t will be evolving and changing faster than it has at the federal level.”

“It’s normal for state constitutions and state high courts to be the site of these kinds of deep value contests,” he adds. But “there’s a dignitary harm that follows from demoting the debate to the state level, as well as the practical harm that follows from having that uncertainty.”

States as laboratories for rights

While the U.S Constitution is the supreme law of the land, functionally it sets a floor for which rights are protected from government interference. State constitutions have thus long functioned as a tool for protecting rights within states above and beyond that federal floor.

Aiding this bedrock feature of American law is the fact that state constitutions are much easier to amend than their federal counterpart. In most states, amending their constitutions requires supermajority approval from the state legislature, the governor’s approval, and ratification via a statewide vote. And 18 states allow voters to directly propose changes and ratify them at the ballot. That’s compared with the U.S. Constitution’s high bar of two-thirds approval in both houses of Congress and ratification by 38 states.

Consequently, while the U.S. Constitution has been amended just 27 times in 233 years (the last time in 1992), the average state constitution has been amended 115 times. In several instances, state constitutions have helped pave the way for the U.S. Supreme Court to enshrine rights nationally.

An overwhelming majority of state constitutions recognized an individual right to keep and bear arms, for example, before the highest court in the land did so in 2008. Many states also gave constitutional protection for same-sex marriage before the high court did in 2015.

“States preexist the U.S. Constitution, and many of them had written constitutions first,” says Emily Zackin, an associate professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“Pieces of [the Constitution] were actually inspired by the original state constitutions,” she adds, including much of the original Bill of Rights. “As American history goes on, the development is kind of linked.”

In other instances, key “rights” within American life have been left entirely to state constitutional protection. There is no right to universal voting or education in the federal Constitution, for example, but many states have constitutional provisions explicitly protecting both.

One might think that would lead to significant state-by-state variance in how people vote or get public education – and in practice that can be the case. But all 50 state constitutions, for the most part, resemble one another.

This would likely not be the case with abortion rights, and indeed hasn’t been with other politically charged rights that don’t have robust protection under the federal Constitution. Voting restrictions vary widely across the country, for example, as do labor rights.

Twenty-seven states in the country have “right-to-work” laws, meaning workers can’t be required to join a union in order to get or keep a job. Nine states have amended their constitutions to guarantee that right, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Tennessee will vote to add a similar amendment to its state constitution next year. In Illinois, voters will decide whether to do the opposite, amend its state constitution to effectively make “right-to-work” laws unconstitutional. And a similar dynamic has begun to emerge concerning abortion rights in state constitutions.

While Vermont is seeking to become the first state to amend its constitution to guarantee a right to abortion, 13 state supreme courts have interpreted their constitutions to protect abortion rights. Four states, meanwhile, have amended their constitutions to explicitly state that abortion rights aren’t protected. Two states – Kansas and Kentucky – will vote to ratify similar amendments next year.

Many Americans may prefer to have individual states determine for themselves the extent to which they want to protect abortion rights. But any rights holder “would prefer to have their rights protected by the federal Constitution than 50 state constitutions,” says Joseph Blocher, a professor at Duke University School of Law in North Carolina.

“The relative brevity and stability of the federal Constitution lends a special cultural, and I think legal, force to the rights that it guarantees,” he adds.

The case of Kansas

Kansas offers a glimpse of the future that abortion rights could face post-Roe.

Two years ago, the state Supreme Court ruled that its constitution protects a woman’s reproductive rights. Any kind of state law limiting abortion access – including dozens of bipartisan restrictions enacted by the Legislature in recent years – was now in jeopardy. State Sen. Molly Baumgardner was one of many anti-abortion Kansans shocked into a reaction, and she began pushing for a constitutional amendment confirming that abortions rights aren’t protected in the state.

“If we were not to have [a] constitutional amendment, then all of those laws are essentially null and void,” she says.

In 2020, the amendment failed to pass the statehouse by four votes. Four moderate Republicans who voted against it lost their seats in the next election, and the reintroduced amendment successfully passed the Legislature earlier this year.

Next August, Kansans will vote whether to ratify it.

“We’re not waiting for the Supreme Court to make a ruling that may or may not impact the different laws that we do have,” says Senator Baumgardner. “We want to make sure the laws passed by those individuals duly elected by Kansans, [who] represent Kansan values, are upheld.”

Indeed, what a post-Roe landscape would certainly bring, state constitutional experts say, is intensified attention – and funding – on state politics and constitutions.

“It would make that issue salient in campaigns for state legislatures and state governors,” says Professor Long from Wayne State University. “It would definitely draw more money and attention to the races for state high court judges, which is almost never a good thing.”

State constitutional volatility may be diluted somewhat if state governments continue to be controlled by one party. Whereas there were 19 “trifecta” states in 1992 – where one party controls the entire state government: House, Senate and governor’s mansion – there are now 37.

A state government with unified policy priorities may prefer passing legislation to the relatively arduous constitutional amendment process, particularly in GOP-controlled states. But if partisan dominance continues in state governments, the abortion rights landscape may not change as often, but it would likely divide the country into pro- and anti-abortion states.

Vermont and Kansas seem to be beginning to form that landscape already.

“We don’t know what will happen at the federal level,” says Vermont state Senator Lyons. But abortion rights are “something we have all taken for granted for nearly 50 years.”

“That pretty well sums up the need,” she adds. A constitutional amendment “is not only reassuring, but it is important to do.”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a liberal icon, once said that she thought the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe came too quickly. She would have preferred that abortion rights be secured gradually, including through state-level change, she said.

Abortions rights are now poised to make that journey, only in reverse. Absent federal constitutional protection, some states may step in to protect the right to abortion. But the right would be diluted and perpetually subject to change.

That “intuitively rubs many people the wrong way,” says Dr. Zackin, author of “Looking for Rights in All the Wrong Places: Why State Constitutions Contain America’s Positive Rights.”

But that kind of volatility has both benefits and drawbacks, she argues.

State constitutions “are more responsive to popular pressure and democracy. Majorities get their say,” she adds. But if you want certain rights protected from majoritarian influence, as America’s founders did, she continues, “a state constitution can’t do that as well.”

Libya elections: Can internal conflict move from bullets to ballots?

In a nascent democracy, should accountability for alleged misdeeds be sacrificed on behalf of national unity? That’s a question Libyans are grappling with in a presidential election with few rules.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Libya’s first-ever presidential election is less than a month away, and the rules over who is allowed to run are still being worked out. Seif al-Islam Qaddafi, son of the slain former dictator, Muammar, is out. Gen. Khalifa Haftar, a warlord who laid siege to Tripoli just last year, is in. For now.

Much is riding on these elections, part of a political road map devised last year by the United Nations, Europe, and the United States. They were designed to unite a nation that has been divided by rival governments, foreign mercenaries, and proxy warfare for most of a decade.

A broad array of factions supports this democratic initiative, which could put Libya under one leader for the first time since a NATO-assisted revolution overthrew the elder Mr. Qaddafi in 2011. But observers caution that claims of voter fraud or irregularities, which have already led some to pick up arms once again, could plunge the country back into conflict.

“These elections are potentially transformative in the sense that Libya’s fundamental political structure would change, but they are a recipe for controversy in the way the election has been framed and who can and cannot run,” says Claudia Gazzini, an analyst for the International Crisis Group. “It’s a big risk.”

Libya elections: Can internal conflict move from bullets to ballots?

It was not the turning of the page that many had hoped for after years of conflict, but a callback to Libya’s troubled authoritarian past: a Qaddafi dressed in a distinctive brown turban and robe, addressing the nation on live television from Tripoli.

So attired, in February 2011, Muammar Qaddafi had vowed to amass an army of millions to “cleanse Libya inch by inch, house by house” of pro-democracy protesters.

This time, on Nov. 14, it was Seif al-Islam Qaddafi, the slain dictator’s son, ceremoniously registering for Libya’s first-ever presidential election on Dec. 24, and asking for the people’s vote.

Yet Mr. Qaddafi, still subject to a decade-old International Criminal Court arrest warrant for alleged war crimes, was hardly the only controversial candidate.

Gen. Khalifa Haftar – a warlord who ran eastern Libya as an independent entity, has styled himself as a strongman ruler similar to Egypt’s Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, and laid siege to Tripoli just last year – announced his candidacy two days later.

The initial reaction of many Libyans who are supporting the elections was: Well, that’s democracy.

But the question of who is and isn’t allowed to run has quickly become a new battleground in Libya – politically, and potentially, militarily.

Much is riding on these elections, part of a political road map devised last year by the United Nations, Europe, and the United States after warring factions in the country’s east and west deadlocked. They were designed to unite a nation that has been divided by rival governments, foreign mercenaries, and proxy-warfare for most of the last decade.

Yet like much in Libya, whether someone is a democrat or a war criminal, or should be allowed to run, depends on whom you ask.

“Recipe for controversy”

Dozens of individuals and groups are filing legal challenges against rival candidates, derailing several campaigns and threatening to unravel the polls themselves.

Late last week Libya’s electoral commission struck Mr. Qaddafi from the ballot as “ineligible,” following a motion by a Tripoli military prosecutor who cited his conviction in absentia by a Libyan court in 2015 for war crimes committed as part of his father’s 2011 crackdown.

Mr. Qaddafi’s lawyer sought to appeal the ruling, but an attack by gunmen allegedly loyal to a rival candidate prevented the attempt.

On Sunday, interim Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah, a leading candidate, was ruled ineligible for violating the election law by not resigning his post prior to the polls. Efforts are underway to challenge Mr. Haftar’s candidacy over the Tripoli siege.

The elections were slated to coincide with the 70th anniversary of Libya’s independence, and a broad array of political factions supports this democratic initiative, which could put Libya under one leader for the first time since a NATO-assisted revolution overthrew the elder Mr. Qaddafi in 2011.

But observers caution that claims of voter fraud or irregularities, which have already led some to pick up arms once again, could plunge the country back into conflict.

“These elections are potentially transformative in the sense that Libya’s fundamental political structure would change, but they are a recipe for controversy in the way the election has been framed and who can and cannot run,” says Claudia Gazzini, a senior Libya analyst for the International Crisis Group. “It’s a big risk.”

Nearly 100 candidates registered for the presidential elections, organized by a hastily passed electoral law and without a clear vetting process. Most are expected to stay on the ballot, to be decided by 2.8 million registered voters across the country.

With so many candidates fracturing the vote among so few voters, a few hundred votes here or there could catapult one candidate or deny another from entering the second round.

Qaddafi in question

And Mr. Qaddafi’s candidacy offered a cautionary tale.

Some tribes and members of the Libyan public – wary of post-revolution corruption and violence – hoped that a reformed Mr. Qaddafi, who had not been seen in public until registering as a candidate this month, would offer an alternative to revolutionaries in the western half of the country and the autocratic Mr. Haftar in the east.

Other Libyans said the Quran-quoting younger Mr. Qaddafi looked every bit a “person that was religiously cleansed” of his past mistakes.

Yet many rejected his candidacy.

“Our general preference is for new faces to take office, but currently almost all the candidates have been under the former regime in some way or the other,” notes Wadah Alkeesh, a Libyan Red Cross worker.

Hassan Garsa, a human rights activist from Bani Waled, 100 miles southeast of Tripoli, is among those who threw their support behind the younger Mr. Qaddafi as someone they believed would “reunite Libya through reconciliation.”

He called Libyans’ accusations and the ICC warrant for Mr. Qaddafi “unfounded allegations” designed to torpedo his campaign.

Then there is the mercurial Mr. Haftar, who three years ago stated Libya was “not yet ripe for democracy.” He is now asking for Libyans’ vote one year after he laid siege to a large segment of the population. “I declare my candidacy for the presidency, not because I am chasing power but because I want to lead our people toward glory, progress, and prosperity,” he said.

Still, other Libyans are supporting newcomers, such as Hatem El-Kour, a comedian, to provide them with “a break from the current hypocrisy.”

And having General Haftar, along with other former members of the regime, vie for votes against businessmen and a comedian may be fruitful.

“For Libyans … to see these people who have dominated the past 11 years try and articulate a program, is not bad in of itself. In a way, it is cathartic,” says Jalel Harchaoui, a Libya expert and senior fellow at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.

And if the strongmen and armed leaders fail to win large swaths of the vote, “it could be therapeutic,” he adds.

Legal framework

Not everyone is convinced, however, that the elections are being held under the right conditions.

“A new constitution should be issued first, banning … everyone from the regime from running or holding office in Libya,” says Khaled Zintani, an aviation engineer in Tripoli. “These elections should not happen because they are not fair or just.”

While the first round of presidential elections is slated for Dec. 24, the dates of the second round of presidential elections and parliamentary elections are not set. The election law does not give a mandatory time frame in which they should be held.

The eastern-Libya-based House of Representatives passed the election law without a vote, quorum, or input from many of Libya’s political factions. Due to a quirk in parliamentary procedure, it is free to amend the law at any time.

“The main problem is the lack of consensus on the legal framework for the upcoming elections since the country does not have a constitutional basis for either candidate criteria or the vote,” Alessia Melcangi, non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, writes via email.

“A delay or failure in the electoral process could risk dragging the country back into the abyss of war.”

There has already been plenty of rule-bending and structural challenges: The number of voting stations outnumbers that of poll observers; and a de facto dividing line in the center of the country means representatives from candidates from the east or west will not be able to observe voting procedures in the other half of the country.

That leaves Libya vulnerable to accusations of vote-rigging and irregularities in rival regions – convenient for warlords and others with oversized personalities and bruised egos who are looking for blame should their election showings be less than stellar.

Some observers warn that many militia leaders may be paying lip service to the West – running on the ballot while readying their bullets for if and when the electoral process breaks down.

“They want to show they are Jeffersonian democrats, peaceful individuals who tried to serve a nation that loves them, but in the end were robbed by bad guys on the other side who rigged the elections,” says Mr. Harchaoui, the analyst.

“By claiming a conspiracy preventing them from reaching the finish line, they will have an excuse to revert to their coercive ways.”

Yet despite fears and reservations, many Libyans are hopeful about choosing their leader for the very first time.

“Of course, I will vote,” says Mr. Alkeesh, the Libyan Red Cross worker. “My vote matters, and it should for everyone else.”

A Monitor correspondent contributed reporting from Tripoli, Libya.

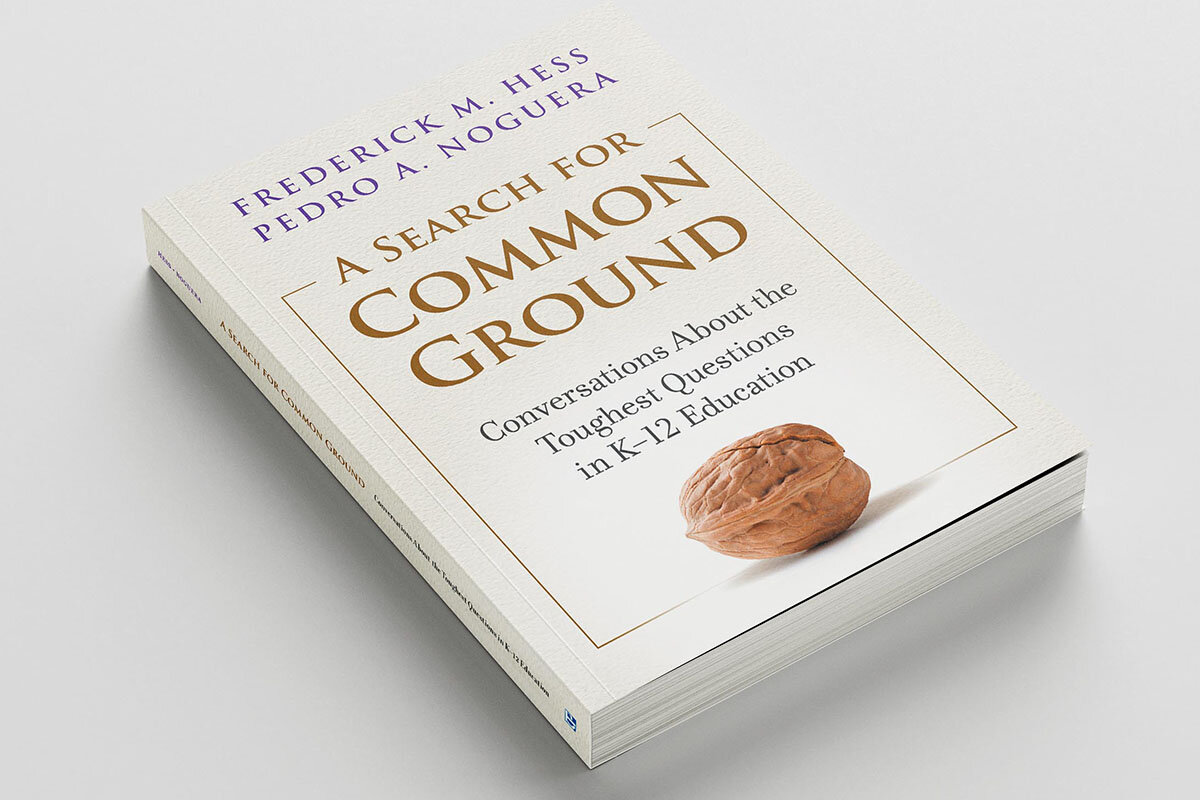

Civil debate about education? Two opponents offer a blueprint.

How can Americans who disagree about education talk productively? Two educators with opposing views wanted to find out for themselves. The result is a book and podcast with ideas for moving forward.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When Frederick Hess and Pedro Noguera wanted to better understand each other’s often opposite positions on education, they hashed it out in emails.

Their correspondence was published earlier this year in the book “A Search for Common Ground: Conversations About the Toughest Questions in K-12 Education,” and their approach has gotten the attention of school board members and educators, who suddenly find themselves in a firestorm over mask mandates and the teaching of race.

In the book’s preface, the duo say they have “spent much of the past few decades on opposing sides of important educational debates, with Pedro generally on the Left and Rick mostly on the Right.” Dr. Hess is director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, and Dr. Noguera is dean of the Rossier School of Education at the University of Southern California.

They’re often asked for advice on how to start difficult conversations. “It takes an interest in listening to one another,” says Dr. Hess in a joint Zoom call with the Monitor.

“This country is so divided and it’s dangerous, because it’s becoming more and more violent,” adds Dr. Noguera. “And so modeling how to have civil debate is really important.”

Civil debate about education? Two opponents offer a blueprint.

Rancor over COVID-19 policies, diversity and equity initiatives, and school choice has divided communities and supercharged school board meetings. Is there any way to find common ground about education amid such divisions?

Some people say yes.

Frederick Hess and Pedro Noguera, two education policy leaders, published a book earlier this year – “A Search for Common Ground: Conversations About the Toughest Questions in K-12 Education” – made up of in-depth emails they shared over seven months to better understand each other’s beliefs and unearth hidden agreement. They currently host a podcast, “Common Ground,” with recent episodes tackling the role of parents in education and anti-racist education.

The authors describe themselves in the book’s preface as having “spent much of the past few decades on opposing sides of important educational debates, with Pedro generally on the Left and Rick mostly on the Right.” Dr. Hess is director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative Washington think tank, and Dr. Noguera is dean of the Rossier School of Education at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

The goal of their exchange, the two write in the book, is to offer a model for those who “desire to disagree with grace and explore differences without rancor.”

The book’s impact will be “up to the readers and what they do with it,” says Dr. Noguera in a phone interview. He and Dr. Hess have done a series of book tour events, mostly on Zoom, where the two live-demo talking through tough issues respectfully for their audience. They’ve spoken at the Wyoming Education Summit, at an annual meeting of the Council of Chief State School Officers, and to staff of foundations like the Walton Family Foundation, among others. The most frequent feedback is that the book is a breath of fresh air, says Dr. Noguera.

Fred Campos, from Bedford, Texas, is an elected school board member of the Hurst-Euless-Bedford Independent School District. He was assigned to read the book for a leadership training program he’s participating in with the Texas Association of School Boards (TASB).

Mr. Campos listened to the audio version of the book twice and says he “loves the premise that we should not go to the extremes.” As a second-term board member, he’s adjusting to a “new era” of more polarization and increased attendance after a fairly quiet first term. The book helped him better understand why some in his community wanted a mask-optional policy – which differed from his position in favor of mask mandates.

“One thing I think both authors did well is they were complimentary of one another, respectful, and that modeling is huge, whether you’re dealing with parents, other board members, or staff,” Mr. Campos says.

“Light a candle”

The idea for “Common Ground” started before COVID-19 and the latest waves of education furor. Even in pre-pandemic days, tension existed within the field. For Dr. Hess, disputes over education over the past few years felt more polarized than at any time in his nearly 30-year career as a K-12 educator, college professor, and researcher.

One November night in 2019, Dr. Hess says he was sitting in his office, staring into space, and pondering how to actually model a different style of conversation. He started thinking about who was someone who disagreed with him on major issues and might be willing to engage in a civil dialogue.

“Education is supposed to be about teaching kids how to wrestle with things, how to look past our differences, and it felt like rather than leaning on this, we’ve been as bad as anyone,” he says in a phone interview. “So I finally said, ‘I’m a big fan of ‘light a candle rather than curse darkness,’ … so I picked up the phone and called Pedro, and he was great about it.”

“I immediately said yes because I appreciated the need for dialogue on these issues, and like him, I was frustrated by the tenor of the debate and the kind of paralysis that I would say characterize the field,” says Dr. Noguera.

The two wrote emails to each other from January through July 2020, on 11 hot-button education topics such as school choice, the achievement gap, testing and accountability, diversity and equity, and teacher pay. They also addressed major events that hit while they were writing, such as COVID-19, the shuttering of schools, and the murder of George Floyd.

Both men say they were provoked at various times by each other’s viewpoints. Because they were communicating in writing, they had time to reflect before responding and gather evidence to back their points. The two found areas of common ground on nearly every topic, especially on teacher pay and testing, after airing their differences.

In a joint Zoom interview with the Monitor, the pair easily banter with each other, but say it took time to develop rapport. They’re often asked for advice on how to start difficult conversations. Dr. Hess says he thinks anyone can do it, but it takes certain skills.

“It takes an interest in listening to one another. It takes the habit of pausing on your first ‘that’s wrong’ in order to listen, hear them, and ask a question instead of pushing back,” he says.

“I think the need for this can’t be understated, especially now,” Dr. Noguera adds during the Zoom meeting. “This country is so divided and it’s dangerous, because it’s becoming more and more violent. And so modeling how to have civil debate is really important.”

Kay Douglas is a former school board member, a senior consultant at TASB, and the instructor who assigned “Common Ground” to the leadership cohort that Mr. Campos is a part of. She says the book offers a valuable example of intentionally trying to understand and work with others.

“Otherwise, we are going to self-destruct. People are so stressed and the stress level keeps going up,” she says.

“Muscles that we have to build”

For Dr. Noguera, learning how to debate respectfully was something he learned around his kitchen table. When he was growing up, his dad, an immigrant from Trinidad, was a police officer in New York City. He would sometimes bring home friends with conservative views on crime.

“I was a kid and I’d listen to these conversations and get angry, but because they were adults and I was a kid and I wanted to engage, I had to figure out how to do that respectfully because my parents insisted on respect,” he says.

As a professor, Dr. Noguera has invited people who disagree with him on policy to debate him in his classes, because he thinks it makes his ideas stronger and shows that people can disagree “without attacking an individual’s personhood.” Conjuring up the worst intentions about other people, he says, is unproductive and unhealthy for democracy.

Dr. Hess agrees that subjecting his ideas to scrutiny from the other side is a way to check blind spots and make policies stronger. He compares civil dialogue to going to the gym.

“Listening to somebody, actually taking care to understand why they are pushing back, answering them without going to sound bites or talking points, these things are like muscles that we have to build,” he says. “If all you do is fire off tweets or Facebook posts or talk to people who think like you, it’s like you never go to the gym to build those muscles.”

In September, Dr. Hess and Dr. Noguera spoke at the Wyoming Education Summit, attended by teachers, administrators, home-school parents, and school board members.

Jillian Balow, Wyoming superintendent of public instruction, says the theme of the book was particularly relevant since the state has also seen an uptick in school board meeting attendance and parents concerned about curricular materials. She’s pondering ways to make policymaking more transparent, such as establishing community teams to look through school policies and identify areas for public involvement.

“We have a system that really caters to people talking past each other,” Ms. Balow says. She points to schools traditionally including parents in their own child’s learning, but providing fewer outlets for involving parents in policy or curricular decisions.

“Maybe there are some opportunities … so there’s less talking past and more finding common ground,” she adds.

Not just another lizard: Peruvian beauty offers extinction counternarrative

Sometimes, the best part of a reporting trip doesn’t make it into a story. While reporting at the species lab for our next story, I got the chance to witness an incredible mating dance performed by an Andes condor at the bird rehab facility. Alas, the female condor who was the object of all the flapping and fluttering was not buying, and the male retreated to his corner, rebuffed.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

When Peruvian herpetologist Pablo Venegas announced the discovery of a new lizard this fall, the glimmer of good news was lost.

In October, U.S. wildlife officials announced that 23 species are gone forever and should be declared extinct, including the ivory-billed woodpecker – once common to Southern U.S. woodlands and so imposing it earned the moniker “Lord God bird.” In Europe, BirdLife International announced an updated “red list” that found as many as one-fifth of the Continent’s bird species are declining rapidly.

Overall, scientists have declared that Earth is in its sixth mass-extinction era – but this one the first to be the result not of volcanoes or asteroids, but of human activity.

Against that backdrop, Mr. Venegas, who has the discovery of several dozen frog, snake, and lizard species to his credit, says such finds should not in any way be used to soften the alarm over the loss of biodiversity. But they should, he adds, provide encouraging evidence that there is still time to preserve much of Earth’s biological richness.

“It’s not about crying victory,” says Mr. Venegas. “That’s not the message people should take from this. Much better if the hopefulness of a new species discovery energizes efforts to preserve nature and find out more about what’s out there.”

Not just another lizard: Peruvian beauty offers extinction counternarrative

After a couple of decades poking around Peru’s remote rainforests – some large swaths still untouched by invading woodcutters, miners, cattle grazers, and coca farmers – Pablo Venegas has developed an eye for what is different and even unknown to humankind.

In that time the herpetologist has the discovery of several dozen new frog, snake, and lizard species to his credit.

So when a gorgeous wood lizard with gold-rimmed eyes and a delicate mosaic hide of iridescent blues, oranges, and greens scooted by him several years ago, Mr. Venegas had a hunch the showy reptile was going to add to his list.

And he was right. A lengthy scientific process, these days including DNA sequencing, revealed that what Mr. Venegas had discovered in Peru’s Huallaga River basin was a “new” species of lizard, in that it was previously unknown to humanity.

The announced discovery of a new lizard in a distant rainforest may elicit a blasé “so what?” from some. But amid a crescendo of extinctions and warnings about threatened flora and fauna around the globe, Enyalioides feiruzae, as Mr. Venegas named the lizard, offers a hopeful counternote about the state of Earth’s biodiversity.

Indeed, when Mr. Venegas was able to officially announce his discovery this fall, the glimmer of good news was lost amid reports of extinctions and species decline.

In the United States, federal wildlife officials announced in October that 23 species are gone forever and should be declared extinct. They included several Hawaiian songbirds and the much-mourned ivory-billed woodpecker – a species once common to Southern U.S. woodlands and so imposing it earned the moniker “Lord God bird.”

In Europe, BirdLife International announced in October an updated “red list” that found as many as one-fifth of Europe’s bird species are declining rapidly toward extinction.

Overall, scientists have declared that Earth is in its sixth mass-extinction era – but this one the first to be the result not of volcanoes or asteroids but of human activity that has polluted the environment, warmed the climate, and destroyed habitats.

Against that backdrop, Mr. Venegas says the discovery of new species should not in any way be used to soften the alarm over the global loss of biodiversity. But it should, he adds, provide encouraging evidence that there is still time to preserve much of Earth’s biological richness – some of which is still unknown to humans.

“I think there is an element of optimism in being able to announce a species of frog or reptile that previously wasn’t known, but it’s not about crying victory,” says Mr. Venegas, standing in the specimen storeroom of the Center for Ornithology and Biodiversity (CORBIDI) in Lima, where he has been curator of amphibians and reptiles since 2007.

“We have people tell us, ‘All we hear about today is how species are disappearing, but you’re finding new species, so it seems we’re doing OK.’ But that’s not the message people should take from this,” he adds. “Much better if the hopefulness of a new species discovery energizes efforts to preserve nature and find out more about what’s out there.”

Beyond the exhilaration that goes with announcing a piece of nature no one knew existed, there are also practical motivations behind the work of discovering new plant and animal species. CORBIDI is a small scientific nongovernmental organization that survives on foreign donors, the most important of which is the Rainforest Partnership, based in Austin, Texas.

Those donors value evidence that their dollars are getting results.

At a national level, finding new species and compiling the rich natural inventory of little-studied areas helps activists and organizations like CORBIDI pressure the government to create new nature reserves – or do a better job of protecting existing ones.

And even though Peru is already recognized internationally as a biodiversity hot spot, the discovery of new species creates the kind of fanfare that helps Peruvian environmental officials attract more international support and funding for the country’s rich but often poorly protected nature reserves.

Enter the new earless frog with a distinctive cross marking between the eyes and along the back, announced in April by Peru’s service for natural protected areas, SERNANP.

“One new frog species may seem like a small thing, but when it’s part of a growing list of new species discoveries, that frog helps us secure Peru’s place as a highly biodiverse country worthy of international support for investigating and protecting what we have,” says Edgar Vicuna, communications director of SERNANP in Lima.

Over the past five years, SERNANP has announced 67 new species – over half of which were plants, including a number of orchids. But the list also includes 17 amphibians and four new bird species.

And while adding new species helps Peru secure its reputation for “mega” biodiversity, it can also give the country a boost on international “most species” lists – a point of pride for SERNANP and many Peruvians, especially those involved in scientific investigations or activities like ecotourism.

Noting that Peru is No. 1 globally in butterfly species, ranks third in birds, fourth in amphibians, and seventh in reptiles, Mr. Vicuna says discovering new species can “help us go up in those rankings and add to our international renown for biodiversity.”

Of course with that fame comes a responsibility to protect those natural riches. Mr. Vicuna says Peru is working hard at preservation, redoubling efforts at establishing agreements with communities in biodiverse areas to promote economic activities that help preserve sensitive areas instead of destroying them.

But he underscores that nearly 20% of Peru’s territory has been declared nature reserves, with the country’s national parks the “jewels” of that vast terrain with some level of protected status.

SERNANP

Mr. Venegas of CORBIDI says his experience in the field tells him many of Peru’s biodiversity hot spots aren’t adequately protected. Park rangers are often woefully outnumbered by illegal miners on the hunt for gold, woodcutters snatching prized tropical woods, farmers clearing land for grazing cattle – and armed drug traffickers.

Indeed, a number of the herpetologist’s species discoveries occurred when he was alerted to a new road being built into an uninvestigated area, or to human activity pressing into a protected zone – prompting him to rush in to do species inventories.

“It’s important that we go into threatened areas and get a full accounting of what exists there – for one thing, so that we know what risks being lost,” he says.

As he pursues his search for new species, Mr. Venegas says he remains encouraged by a fact that might surprise many people accustomed to hearing dire reports of biodiversity loss and species extinction.

“The reality is that the rate of discovery of new species continues to surpass the rate of confirmed extinctions,” he says. “We don’t know how long that will be the case, especially given the accelerating pressures on areas of high biodiversity.”

Noting that even as a little boy he was fascinated by reports of a new bird or perhaps a previously unknown rodent found somewhere in the world, he adds, “To me it’s reassuring that there are still places of great natural wealth to be explored and unknown species to be discovered.”

SERNANP

Difference-maker

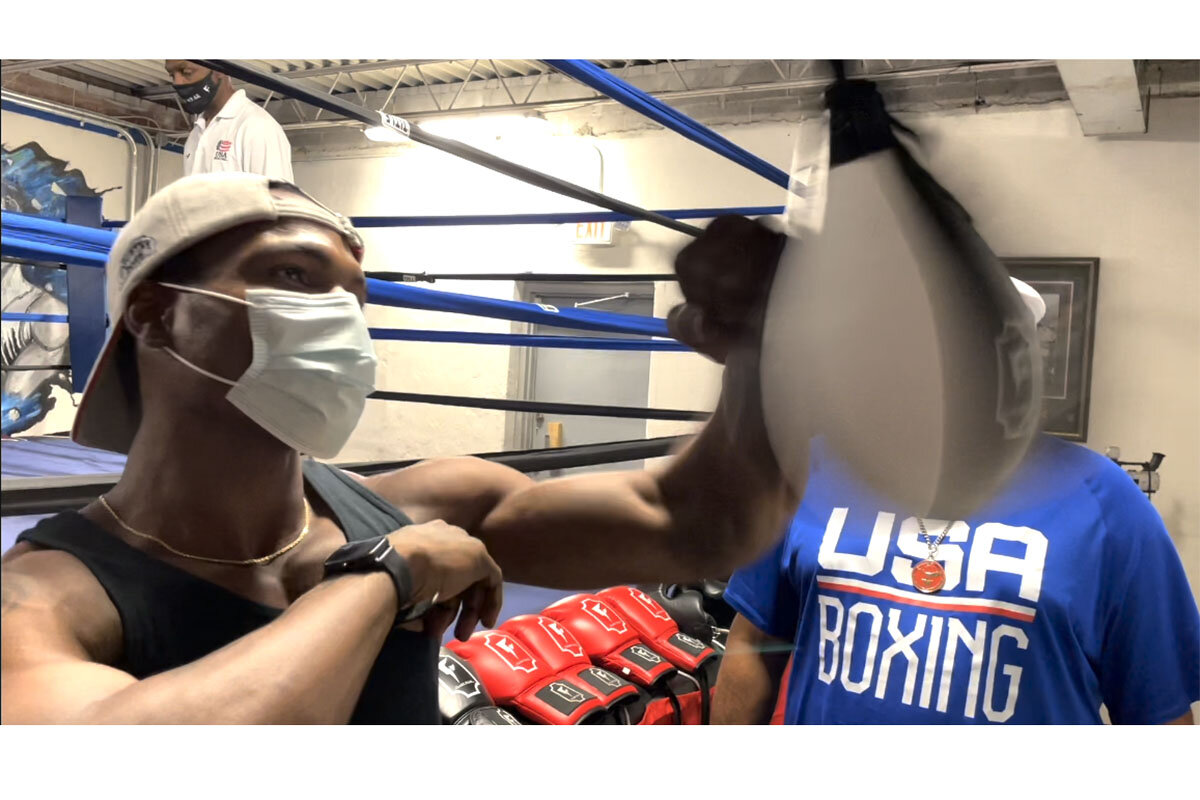

Boxing and talking: How a 1988 Olympian gives back

Instead of trying to stop students from fighting, this difference-maker helps them turn an impulsive response into a disciplined tool. Among the results are boxing championships – and life skills.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Amicia Ramsey Correspondent

Arthur “Flash” Johnson founded the Flash Boxing and Activity Center in East St. Louis, Illinois, a high-poverty, high-crime area, where fighting is a frequent response to adversity. His goal is to redirect the impulse to fight into the sport of boxing and to nurture the discipline and respect needed to succeed not only in the ring, but also at school, on the job, and in the community.

“Coach is going to give you all the tools, and you have to work with them,” says Carlton Richardson.

After Mr. Johnson spotted him in an after-school program and invited him to try the sport, he was hooked. “I developed a passion for it,” Mr. Richardson says.

He trained with Coach Johnson for months. “It was hard at first. It’s mental,” explains Mr. Richardson, noting that he spent countless hours in the gym. “It has to be your life,” he adds.

That dedication paid off. He took home the super heavyweight title for his division at the 2016 Ringside World Championship and went on to place third in the nation that year. Now 21 years old, Mr. Richardson works full time, but he applies his accomplishments in the ring to everyday life. “It taught me how to face a lot of fears,” he says.

Boxing and talking: How a 1988 Olympian gives back

Amateur boxer Kevin Hill remembers when his mother begged high school administrators to give her son a second chance after he’d gotten kicked out of three different high schools for fighting. They did. He graduated from East St. Louis Senior High School in 2007, an accomplishment he doesn’t take lightly.

Mr. Hill recalls experiencing chronic homelessness while growing up, and losing friends and family to street violence or drug-related crimes. He dealt with it all by fighting.

“I wasn’t friendly,” he reflects. “I would have an attitude, … and that would stir a fight up.”

Today, Mr. Hill is still fighting, but he’s not getting in trouble for it. He spends his days at the Flash Boxing and Activity Center, a haven for children and young adults in East St. Louis. Despite finding a coach in Arthur “Flash” Johnson later in life, Mr. Hill still has an opportunity to turn pro.

Mr. Johnson, who holds both amateur and professional world titles and competed in the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, South Korea, is the founder of the activity center. He also co-founded the Arthur Johnson Foundation with his wife, Latonya Johnson, in 2001 to give back to the community and serve youth through boxing and mentoring programs.

In a high-poverty, high-crime area, where fighting is a frequent response to adversity, Mr. Johnson works to redirect that impulse into the sport of boxing and to nurture the discipline and respect needed to succeed not only in the ring, but also at school, on the job, and in the community.

“You could’ve had a lot of bad things happen to you in your life,” he says. “But at the end of the day, when you reach a certain age, life expects you to make better choices.”

From competing to coaching

After retiring from boxing in 2003 and later overcoming a disease he was told would kill him, Mr. Johnson developed a heart for coaching athletes. That’s the most obvious thing he focuses on at the activity center, which was built in 2017 following years of effort. “You have to keep knocking when the doors are closed, even if they say go to the next door and the next,” he says.

This year, after rebounding from the worst of the pandemic, the center has 40 children and young adults registered, about 85% of whom are under 18. Boys and girls can begin as young as 8. Mr. Johnson also trains men and women who want to pursue boxing careers.

Boxing is “going to demand you to be disciplined,” Mr. Johnson says, pointing out the importance of developing character – the less obvious focus of both the foundation and the center.

Alongside the coaching, a mentoring program is designed to instill values and nurture character growth. “Twice a month we get the guys in the gym, and we go to the conference room. We have a roundtable talk,” says Earnest Rice-Bey, a volunteer coach who grew up in the neighborhood. Boxing was Mr. Rice-Bey’s first love, but the streets pulled him away from it, resulting in three stints in prison, he says, before he turned his life around. “I try to mentor to that toughness,” he explains. “I know what it is like because I was there. I see it in them.”

Nothing is off-limits during the roundtable discussions.

“I had trust issues at first,” says Mr. Hill, who was a young child when his father was shot and killed at just 21 years old. From that day forward, Mr. Hill explains, his only ambition was to stay alive longer than his father. Although he’s exceeded that life expectancy, it can be hard to see beyond the violence and scarcity prevalent in his environment. Mr. Hill isn’t the only one to have experiences and feelings like these come up in the roundtables. It’s where everyone comes to lay down their burdens. Then, in the ring, they can tap into their potential.

“It has to be your life”

“Coach is going to give you all the tools, and you have to work with them,” says Carlton Richardson, a 2016 Ringside World Champion.

Mr. Richardson was 16 years old when Coach Johnson spotted him at an after-school program. “There were so many other kids in the gym, and he saw something in me,” says Mr. Richardson, who had never stepped inside a boxing ring. Mr. Johnson invited him to try the sport – and that was all it took. “I developed a passion for it,” he says.

For about six months, he trained with Coach Johnson. “It was hard at first. It’s mental,” explains Mr. Richardson. He changed his diet and sleeping habits and spent countless hours in the gym. “It has to be your life,” he adds.

Then came his first competition: the Ringside World Championship, a four-day tournament in Independence, Missouri, with more than 1,500 boxers from around the world. Mr. Richardson says he took home the super heavyweight title for his division by outworking his opponent. He would go on to four more competitions and earn the rank of third in the nation that year. Now 21 years old, Mr. Richardson works full time, but he applies his accomplishments in the ring to everyday life. “It taught me how to face a lot of fears, like being comfortable in uncomfortable situations,” he says.

Off the streets and into the ring

Poverty and crime are common threads in the lives of many of the athletes who come to the center. A 2019 survey from the U.S. Census Bureau shows the poverty rate of East St. Louis is just over 33%, which is three times the national average. That same year, East St. Louis ranked as one of the most dangerous cities in the U.S., according to FBI data.

Lawrence Wise is an East St. Louis Park District police officer and a native of the city. For three decades, he’s seen how young men and women faced with adversity make poor decisions that lead to crime and jail. He says a lot of the youth he encounters have pent-up emotions that are ready to explode. That’s where Mr. Johnson’s activity center can help, he adds.

“He is taking some of the anger out of them by teaching and instilling boxing skills. The students learn self-respect,” says Captain Wise. Recalling the mentors who taught him how to value himself, he says the youth who join the boxing club get that same support. “They have potential to be great and can go on to be the person [Mr. Johnson] sees them to be,” explains Captain Wise.

Mr. Johnson knows firsthand the struggles of those he coaches. He describes growing up in public housing in East St. Louis and being raised by Estella Johnson, a single mother with 10 children who struggled to make ends meet. “She was a Wonder Woman and definitely one of my heroes,” he says.

At the age of 11, he forged his mother’s signature on a permission slip to attend a boxing camp hosted by two men in the neighborhood. They were his first male mentors. Mr. Johnson tells his athletes how the grace of God kept him out of trouble, hoping to encourage them to look beyond their current circumstances.

Faith and spirituality are core values at the center. The scripture John 3:17 – which tells of God sending His son to save the world, not condemn it – is painted on the wall. “[God] is all about loving. He is all about second chances,” Mr. Johnson says. “We don’t just throw a kid out of here because he comes in here and acts up. We give him those chances.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

How robots can make us smarter

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Did humanity just become genuinely smarter about artificial intelligence? That could be the case with a 39-page set of recommendations released last week by the United Nations.

The document, a result of three years of work by hundreds of experts, was endorsed by 193 countries. For the first time on a global scale, it lays out universal values for the ethics needed to ensure that AI-driven technologies – from facial surveillance to driverless cars – “deliver for good.” Those values include transparency, social inclusion, accountability, and “explainability.”

The ethical challenges inherent in AI – especially robotic military weapons and mass surveillance – are many. Yet they also help expand human intelligence, force a higher concept of consciousness, and put a focus on the source of intelligence itself, beyond material origins. As more qualities of human thinking are built into AI, such as trust and empathy, the more the designers and regulators of AI must stretch their own thinking.

The UNESCO report is a good example of that progress. Humanity can be smarter, in a very tangible way, and “deliver for good.”

How robots can make us smarter

Did humanity just become genuinely smarter about artificial intelligence?

That could be the case with a 39-page set of recommendations released last week by the United Nations.

The document, a result of three years of work by hundreds of experts, was endorsed by 193 countries. For the first time on a global scale, it lays out universal values for the ethics needed to ensure that AI-driven technologies – from facial surveillance to driverless cars – “deliver for good.” Those values include transparency, social inclusion, accountability, and “explainability.”

“These new technologies must help us address the major challenges in our world today, such as increased inequalities and the environmental crisis, and not deepen them,” said Gabriela Ramos, an assistant director-general at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

The new UNESCO standard is seen only as an “incentive” for nations to build ethics into their AI systems. Yet it adds to other recent efforts to bring a higher order of thinking to the use of computer algorithms now reaching a scale and speed not even imagined in the best of science fiction going back to Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel “Frankenstein.”

One of the most active efforts at setting AI standards is the Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence. This coalition of 20 countries, set up in 2020 by France and Canada, aims to ensure that advanced technologies promote the values of democracy and equality.

The ethical challenges inherent in AI – especially robotic military weapons and mass surveillance – are many. The UNESCO report, for example, says the ultimate responsibility for AI technologies must lie with humans and that even the most intelligent devices “should not be given legal personality themselves.”

The challenges posed by machines able to learn and adapt are in turn forcing humans to learn and adapt. This helps expand human intelligence, forces a higher concept of consciousness, and puts a focus on the source of intelligence itself, beyond material origins. As more qualities of human thinking are built into AI, such as trust and empathy, the more the designers and regulators of AI must stretch their own thinking.

The UNESCO report is a good example of that progress. Humanity can be smarter, in a very tangible way, and “deliver for good.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

God’s love is yours to express

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Loving our friends comes naturally. But when we draw on God’s infinite love for all, it becomes natural to love everyone – and this brings healing.

God’s love is yours to express

It’s so good to act on opportunities to love others. That means, certainly, loving people we know. Also, it means loving people we don’t know. And, significantly, it can mean loving people we may never have considered loving.

Loving like that isn’t just a pleasant way to pass the time. Loving others matters more than we realize, because we’re drawing upon God’s love in doing so.

God’s love is more – infinitely more – than a human emotion. Without conditions, God loves us simply because of who we all are as His offspring – the spiritual expression of God, divine Love. The Bible doesn’t convey that God is merely a loving entity, but states that God is Love itself (see I John 4:8).

It’s never going to be necessary to earn God’s love. In order to better feel that love, though, we need to acknowledge it and act upon it. Christ Jesus said: “This is my commandment, That ye love one another, as I have loved you” (John 15:12). Jesus loved others by expressing God’s love, not just to help people feel happy, but to heal, reform, and restore them.

So, how do we follow Jesus’ instruction and draw upon God’s love to help and heal? To start, it’s important to be sure that we truly are looking to God for our supply of love. If we feel that we just don’t have enough love left to love others, if we’re feeling spent when we try, we may be looking to ourselves as the ultimate source of love. Or, say we express love toward someone, but we keep score, hoping we’ll receive something in return. That’s conditional love and, again, it’s a limited, personal love.

Instead, when we love others simply for the sake of loving as God loves, we’re on the right track. We expect nothing in return; we don’t do it to control others or hope they change and do what we want; we just enjoy being the expression of Love, and acknowledging that others are, too. It’s not about ignoring or condoning bad behavior, but acknowledging everyone’s capacity to feel and express God’s healing, reforming love.

We’ll notice that the more we do this, the more invigorated we start to feel. That’s because we’re drawing on God as the source for our love, and God’s love truly is infinite.

The Monitor’s founder, Mary Baker Eddy, observes in her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “The depth, breadth, height, might, majesty, and glory of infinite Love fill all space” (p. 520). When we behold all space, including all our mental space, as overflowing with infinite Love, we can follow Jesus’ example and heal.

I saw this happen some time ago when, almost daily, a person with whom I worked showed hatred toward me. I remember thinking, “I really don’t know this person, and this person definitely doesn’t know much about me. Why such resentment? Should I just continue to ignore it?” I tried being nice, but this only seemed to inflame his feelings.

So I prayed, basing my prayers on only one thing: God’s love for this individual. My goal was to constantly see him as on the receiving end of a waterfall of God’s cleansing, tender, assuring affection.

After a few weeks of praying this way, I noticed a change. The hatred had shifted to indifference. This encouraged me to pray even more diligently. Finally, the day came when I was standing in a group with some coworkers, and I felt a hand on my shoulder. It was this person! He smiled at me with genuine friendliness, and that was the end of the issue.

While modest, this experience hints at a poignant lesson. It reminded me how important it is never to ignore our opportunities to actively express God’s love. Science and Health instructs, “If Spirit or the power of divine Love bear witness to the truth, this is the ultimatum, the scientific way, and the healing is instantaneous” (p. 411).

Yes, God’s love is ours to express, anytime. Beholding God’s love for a friend is a powerful prayer. It’s also a powerful prayer to behold God loving someone you’d never thought of as a friend. This approach to active loving is so important for our world today.

Watch for opportunities to prove how God’s love truly is enough to heal, comfort, cleanse. Stick with it. As the Bible counsels, “Keep yourselves in the love of God” (Jude 1:21).

A message of love

Preparing for winter

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, correspondent Anna Mulrine Grobe looks at how military families are dealing with hunger, amid a time of inflation.