If you’re heading home and get stuck in a snowbank in Vermont, chances are a neighbor with a truck will stop and help. And if you live nearby, you might be helping your neighbor out of a similar jam some day.

In the Green Mountain State, that’s not just an act of kindness – it’s the way Vermonters live.

“There’s a sense that patriotism isn’t just about national interest. It’s also about how you contribute to community and place,” says Paul Costello, former head of the Vermont Council on Rural Development.

For the past two decades, he was the driving force behind dozens of “community visits,” local discussions focused on turning community goals into action – examples include a new senior housing project, a youth center, and downtown revitalization efforts.

Some believe that focus on community has been the engine behind the state’s largely successful pandemic response. From expanding statewide food distribution to making vaccines accessible, Vermonters have generally been unified, notes Mike Smith, the state’s secretary of human services.

“You’re going to have disagreements, and that’s fine, but in terms of the fundamentals of responding to this pandemic, Vermonters have really stuck together,” he says.

That stands in stark contrast with other states, where the pandemic has further frayed the fabric of community that defines people as neighbors and fellow citizens, regardless of how they vote.

One sign of Vermont’s unity is the state’s high vaccination rate, supported by specific outreach to Black and Indigenous people and other minorities, as well as groups requiring special consideration, such as homebound individuals.

As of Dec. 7, 94.2% of Vermonters 12 years of age and older had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, compared with 81.5% nationally. And 83% of Vermont residents in that age range had been fully vaccinated; that’s 13 percentage points higher than the national statistic according to state and federal data. In addition, as of Dec. 6, Vermont had one of the lowest pandemic death rates, at 1.4 per 100,000 residents over the prior seven days, 10 times lower than Wyoming’s death rate of 14, the highest in the nation on Dec. 6.

Like much of New England, Vermont saw a spike in cases in November when the weather turned colder. But despite the surge, the state still ranks among the best for COVID-19 outcomes.

Vermont’s high vaccination rates remind Mr. Smith of the all-hands-on-deck community spirit that drove rebuilding efforts after the disastrous flooding from tropical storm Irene in 2011. And, he adds, people who relocated to the state during the pandemic became part of this community culture.

“When you come to a community, you’re really embraced. ... People want to make sure that you’re taken care of in terms of your well-being,” Mr. Smith says.

Keeping businesses afloat

The health of businesses has been a top concern too. While some closures have occurred, Vermont showed a 1.6% increase in establishments in 2020 over 2019 and a 4.4% rise in the first quarter of 2021 over the same quarter in 2020, according to the Vermont Department of Labor. Preliminary data for the second quarter of this year over the same quarter last year shows a 6.1% increase.

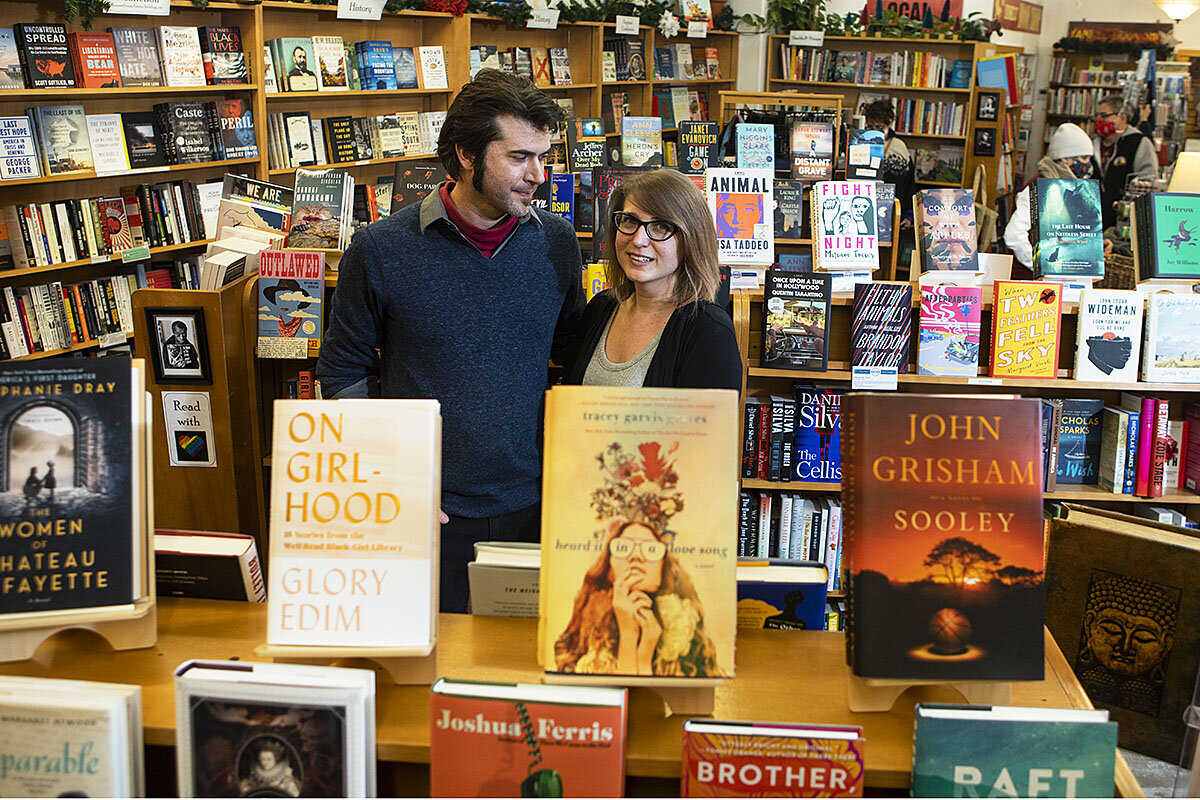

At least some of that progress resulted from Vermonters rallying around their neighbors. Here in Woodstock, a small shire town of about 3,000 people, the Yankee Bookshop credits local support with the store’s survival. Co-owners Kari Meutsch and Kristian Preylowski saw a flood of online orders from people near and far.

“It allowed us to continue to keep the store functioning through those couple of months when we were closed,” Ms. Meutsch says. Some customers even bought gift cards just to help the store. One person asked for his gift card to be used to get books to then-shuttered senior centers and assisted living facilities.

The bookshop re-opened to in-person traffic in June 2020, and Mr. Preylowski senses an increased appreciation for buying local, not just at his shop but across all sectors.

“It means so much more to people now,” he says. And that includes newcomers.

“It’s Vermont culture for sure, but it’s also adopted by the people that joined us,” Ms. Meutsch adds.

Setting the tone

When it comes to states led by a Republican governor, Vermont is atypical. Republican governors in Texas, Missouri, Florida, and Georgia, for example, quickly came out against President Joe Biden’s vaccine mandates for federal employees and contractors, certain health care workers, and all companies employing 100 or more. However, back in the Green Mountains, Gov. Phil Scott was the rare Republican head of state to support it. That fits a pattern for the Scott administration, which has been supportive of pandemic precautions.

The governor has also consistently urged his fellow Vermonters to respect their neighbors who disagree with them.

“Let’s not make the news with screaming matches caught on video,” Governor Scott urged during a press conference earlier this year. “Let’s do things the Vermont way, by being role models and leading by example.”

A few small protests against pandemic restrictions have occurred in Vermont, with one on the Statehouse steps in Montpelier in May drawing between 50 to 100 people. But that opposition failed to gain widespread momentum, and many restrictions, including a mask mandate that Vermonters largely supported, were lifted in June after the state’s vaccination rate passed 80%. Thus far, no statewide mask mandate has been reimposed, though the Legislature did, in a special session on Nov. 22, pass a law giving municipalities the option to enact their own mask mandate if they so choose. Under the bill, that authority for municipalities expires on April 30, 2022.

Maintaining a culture

Though no state has entirely escaped conflict over how best to approach the pandemic, Vermont’s largely cohesive response may be an extension of its deeply rooted neighborly culture. Steve Perkins, executive director of the Vermont Historical Society, says the state’s difficult mountainous terrain has compelled communities to “live as their own units” for most of Vermont’s history.

“This idea of unity and helping one’s neighbor just became a part of life,” Mr. Perkins says. “You could not rely on help from outside your community; it would have to come from the community.”

Anson Tebbetts, Vermont’s agriculture secretary, can attest to that. He remembers the community coming to his family’s rescue more than once while he was growing up in Cabot.

“If we were facing a three- or four-day power outage, the neighbors would bring their generator and they’d help us milk the cows and clean the barn,” he says.

Maintaining a community-oriented culture depends on that kind of neighborly assistance, says Tom Donahue, CEO of BROC Community Action, which is based in Rutland, where Mr. Donahue grew up. And 2020 was full of examples of it, he notes, including an annual charity event that raised three times the money it usually does to support low-income families.

“You might not know the name of every one of your neighbors, but you’re always looking out for each other,” he says.