- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Why GOP is stepping up fight against vaccine mandates

- Democracy under siege? At summit, there’s more to the story.

- Plastic as fuel? Why ‘advanced’ recycling gets mixed reviews.

- Brazilian ‘wonder berry’ offers farmers and the Amazon a future

- After defeat: Lessons learned coaching high school football

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Christmas generosity: How a community helps an IHOP waitress

Rita Rose Williams turned a $40 tip to a waitress into more than $9,000 in donations. She didn’t plan it. But Ms. Williams certainly nudged it along.

On Dec. 1, Ms. Williams gave Jazmine Castillo a $20 tip for a $30 meal at IHOP in Atlanta. “She was … so so grateful, I gave her another $20,” wrote Ms. Williams on Instagram later that day. Ms. Castillo explained the tip alone would cover daycare for her 1-year-old daughter.

After learning more about Ms. Castillo’s financial situation (a recent car accident and overdue rent), Ms. Williams wrote down Ms. Castillo’s Cash App handle. Ms. Williams later posted a description of this “IHOP blessing” on Instagram. What happened next is another example of community generosity unleashed.

"I was bathing my baby, and I started hearing my phone go off," Ms. Castillo told WJXX-TV in Jacksonville, Florida. "I don't usually get Cash App, so I didn't recognize the ring tone, and it just got crazier and crazier ... and it hasn't stopped."

As of Tuesday, Ms. Castillo had received more than $9,000 in donations. She’s stunned and grateful. “The money is more than greatly appreciated,” she wrote to donors. “But ... the fact that it came from the heart and that y’all really didn’t have to do that but chose to do so got to me.”

And Ms. Williams has added a new twist, challenging her followers to find their own Jazmine to bless. “You never know who’s just one step from giving up,” she posted on Facebook. “You never know. So, be kind to people.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

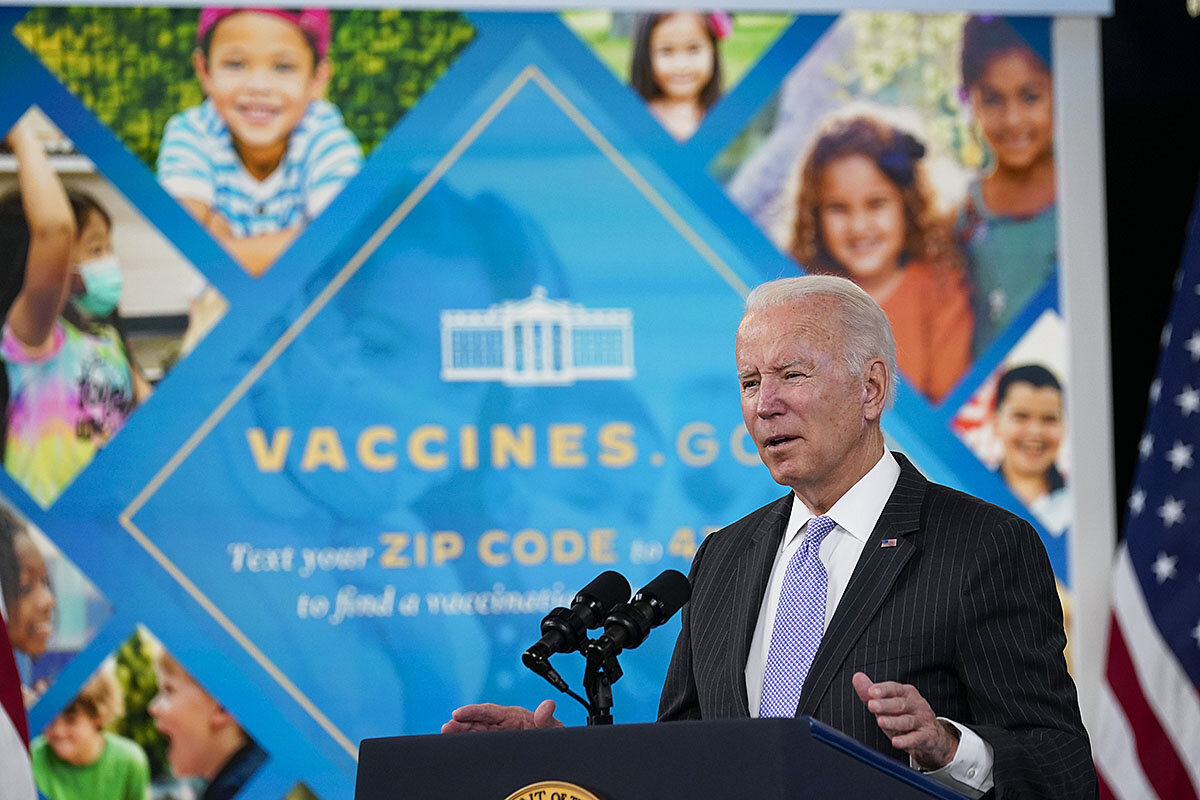

Why GOP is stepping up fight against vaccine mandates

Our reporter probes why Republicans, including those who are vaccinated, are opposed to government-declared mandates. To many, it’s an unjustified – or unnecessary – sacrifice of individual liberty.

Does the pandemic warrant vaccine mandates for private businesses, federal employees, and health care workers? Most Democrats, along with public health officials, tout widespread vaccination as the best tool to promote public well-being and end the health crisis.

“This is not about freedom or personal choice. It’s about protecting yourself and those around you,” said President Joe Biden on Sept. 9, when he announced the mandate for private businesses with over 100 employees, which has since been held up in court.

Today, all 50 GOP senators were expected to vote to invalidate that mandate, which they see as counterproductive and damaging to the economy. They argue the administration has not struck the right balance between the good of the community and individual liberty, nor adequately addressed studies raising questions about the push for universal vaccination, especially for those with natural immunity.

For GOP Sen. Mike Lee of Utah, who has introduced a dozen bills targeting the mandates, the president’s actions violate a key founding principle: that the people are sovereign.

“The use of overwhelming government power without even considering the implications on freedom is precisely why our founders thought the Declaration of Independence, a revolution, and our Constitution were necessary,” he said on the Senate floor.

Why GOP is stepping up fight against vaccine mandates

On more than half of the days the Senate has been in session since late September, GOP Sen. Mike Lee has taken to the Senate floor to rail against one thing: President Joe Biden’s vaccine mandates.

Senator Lee isn’t opposed to vaccination; he himself has gotten the COVID-19 vaccine, and he has encouraged others to as well. But the Utah conservative – a former Supreme Court law clerk – sees the mandates as an unjustified infringement of freedom. He argues that the federal government has chosen coercion over transparency, undermining public trust.

“When openly and transparently informed, I believe that each and every American is able to handle the responsibility of weighing the risks of getting vaccinated or not getting vaccinated,” he said in his opening speech on Sept. 28, introducing his first of a dozen bills targeting the mandates.

Since then, he and fellow Republicans have stepped up the pressure, driven in part by hundreds of constituents calling in to their offices or confronting them back home.

“I believe each time the federal government mandates that we do something, we lose a little bit of our freedoms and our liberties,” says Scott Graves, a power lineman in Kansas who was one of 250 union members that crowded into a standing-room-only town hall with Sen. Roger Marshall after being told that, as a federal subcontractor, he would have to get vaccinated. “We pretty much took a stand and said if you want to spend Christmas in the dark, then keep pushing that. We told Senator Marshall to take that back to Washington.”

Last week, Senator Lee and Senator Marshall were among a handful of GOP lawmakers who threatened to shut down the government, eventually backing down in return for a vote on an amendment to defund the mandates. That effort failed along party lines, 48-50. But the issue is not going away.

On Dec. 8, Senate Republicans forced a vote on a resolution filed by Indiana Sen. Mike Braun – and co-sponsored by all 49 of his GOP colleagues, as well as Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia – to nullify President Biden’s mandate for private employers. The resolution passed 52-48, with Democrat Jon Tester also supporting it. Even if Republicans get several Democrats to help pass the House, it is unlikely to be able to overcome a presidential veto. But GOP senators say the point is to get every member of Congress on record as to whether they support the OSHA mandate.

The GOP push stems from a feeling that Democrats have not struck the right balance between the good of the greater community and individual liberties. They warn that the mandates will prove counterproductive, leading to worker shortages in critical industries and further diminishing public trust.

Most Democrats, along with public health officials, see widespread vaccination as the best tool to promote the well-being of the country and end the pandemic. “This is not about freedom or personal choice. It’s about protecting yourself and those around you – the people you work with, the people you care about, the people you love,” said President Biden when he announced the mandate for private businesses on Sept. 9.

To Senator Lee, that view misinterprets the relationship between government and the people as outlined in the Constitution.

“The use of overwhelming government power without even considering the implications on freedom is precisely why our founders thought the Declaration of Independence, a revolution, and our Constitution were necessary,” said Senator Lee in his opening speech.

Held up in court, for now

There appears to be growing international momentum for universal vaccine mandates, with several countries having already implemented them, and more European leaders recently saying they would support such a move – though the World Health Organization’s top official in the region said this week they should be “an absolute last resort.”

The Biden administration has issued three mandates, all with a January deadline, which apply to more than 100 million Americans: 84 million workers at companies with 100 or more employees, 17 million health care providers under the umbrella of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and 3.5 million federal employees as well as an unspecified number of federal contractors, and subcontractors with contracts worth more than $250,000. Private employees would have the option of weekly testing, but federal workers would not. Private employers would face fines of nearly $14,000 per employee and $136,532 for “willful violations.”

Courts have temporarily blocked both the private employer mandate, implemented by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration under an emergency temporary standard, and the CMS mandate. Yesterday, a judge also blocked the mandate for federal contract workers.

Still, the White House insists it expects the mandates to be upheld, and last month released a fact sheet arguing that such requirements have already “increased vaccination rates by more than 20 percentage points – to over 90% – across a wide range of businesses and organizations.”

Supporters say many employers were relieved to have the government step in so they didn’t have to impose vaccine mandates themselves. But critics argue the president is turning private businesses into a “medical police force.”

“Employers are furious about this. They feel like Biden is pitting them against their employees,” said GOP Sen. Joni Ernst late last week.

Separately, more than two dozen U.S. cities have issued mandates for their employees, some with the option of weekly testing instead of vaccination, and New York City just announced a new mandate for private employers.

A significant number of employees affected by the mandates have applied for religious or medical exemptions, and a Kaiser Family Foundation survey published in late October found that an estimated 5% had quit their jobs rather than comply. Up to 9% said they planned to quit if not given the option of weekly testing.

In a letter released last week, more than a dozen Republican senators warned that the vaccine mandates would “destroy the machinery that allows our nation to function.”

The trucking industry – already facing a shortage of 80,000 truck drivers – could lose more than a third of its workforce, according to the American Trucking Associations, which is involved with one of the court challenges. Some 2,300 New York City firefighters called in sick the first day the city’s mandate went into effect. And nursing staff shortages due to opposition to the mandates shut down a Maine neonatal ICU and a New York hospital’s emergency department.

The U.S. military, whose branches issued their own mandates with deadlines in November and December, has reported high rates of compliance for vaccination among active-duty troops, but significantly lower rates for National Guard troops and reservists, particularly in the Marine Corps.

While most Republicans agree with Senator Lee, at least in principle, that mandating the COVID-19 vaccine infringes on individual rights, some say they might weigh the balance between public health and personal autonomy differently if the threat appeared more urgent.

“I can certainly envision a circumstance where I would support vaccine mandates [but] it would have to be a far deadlier disease,” says Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin in a phone interview. “If we were talking about Ebola, which has a 40% fatality rate, and we had a safe vaccine for that, we’d probably need to force that one on the public.”

Senator Johnson says he knows his stances have made him a political target. His YouTube channel has been suspended multiple times for violating COVID-19 misinformation policies, including after a roundtable he held last month questioning the safety of vaccines, in which he highlighted witness testimony and deaths registered in a national self-reporting database. (Health care providers are required to report deaths following COVID-19 vaccination, regardless of whether there is any causal link.)

“I’m not doing this based on politics at all,” he says. “I’d say the politics … are probably not in my favor because the media and the social media – the COVID gods – have their narrative, and boy, you’d better not push back.”

Indeed, some in his own party seem wary of putting the issue front and center. Minority Leader Mitch McConnell notably did not support the threat to shut down the government last week over the issue. The GOP currently appears well positioned to take back the House and possibly the Senate in 2022, with President Biden buffeted by inflation, supply chain issues, and more. Some Republicans are leery of risking a backlash with a controversial fight over vaccine mandates, which a September poll showed a majority of Americans support.

Science in an age of polarization

The political fight is unfolding against a backdrop of new uncertainty surrounding the pandemic and how best to address it. The recent discovery of the omicron variant has fueled frustration on the left, many of whom blame low vaccination rates for the emergence of new variants and the pandemic dragging into a third year.

“We should be doing everything we can to stop this virus, we should be using every tool to keep America safe,” said Sen. Patty Murray, the Democratic chair of the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, speaking on the Senate floor against Senator Marshall’s amendment. “I do not understand why – after all families have been through, after all we have lost and all the hard work we have done to rebuild – would anyone want to throw that in jeopardy and throw away one of the strongest tools we have: to get people vaccinated.”

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and other Democrats have accused Republican lawmakers opposed to the mandates as being “anti-science.” But GOP Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina says that’s missing the point.

“The executive branch doesn’t have this power,” says Senator Graham, noting that he is vaccinated himself and has encouraged others to get vaccinated as well. “They’re legitimizing an unconstitutional act by suggesting it’s about science. It’s not about science; it’s about the law.”

One factor driving many people to protest, however, is frustration that public health officials have not adequately addressed studies raising questions about the push for universal vaccination, especially for those with natural immunity. Part of the challenge is that there’s still a lot that virologists and epidemiologists are trying to determine about the virus, how it spreads, and how effective vaccines are over time and in the face of new variants. One Centers for Disease Control and Prevention compilation of research on vaccine efficacy, for example, reveals double-digit variance between studies. In response to data showing reduced antibodies after six months, the CDC is now recommending that all adults get booster shots.

Officials say the data is changing over time, but critics fault them for not being more transparent about what they don’t know.

“Nobody really trusts the medical people in charge,” says Mr. Graves in Kansas, who says the inconsistent messaging has undermined his confidence.

A nurse who was working at the front lines of the pandemic says he can see both sides. As someone who has dedicated his life to medicine, he understands the urgent desire to get a public health crisis under control. But he says it opens up “a whole can of ethical worms” to mandate vaccines that have been rapidly upscaled and lack long-term safety data in humans. Several days after getting vaccinated last year, he says he began experiencing severe symptoms, which he blames on the vaccine. The CDC maintains that the vaccines are safe and effective, and says reports of adverse events are rare and most do not prove causation.

Lost in the debate over whether to mandate vaccinations, the nurse adds, is the nuance needed to navigate the complex and sometimes contradictory information involved.

“Science has been hijacked by politics, unfortunately – on both sides,” says the nurse, who did not want to be identified out of fear of losing his job. “No one is winning in this, because we have too polarized a government and all they do is increasingly polarize the population.”

This story has been updated to reflect the result of the Senate’s Dec. 8 resolution on the vaccine mandate for private employers.

Democracy under siege? At summit, there’s more to the story.

In the global battle between two approaches to governance – autocracy and democracy – our reporter looks at how a U.S.-sponsored gathering might, or might not, be effective.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

As President Joe Biden hosts his promised Summit for Democracy Thursday and Friday, much of the talk in Washington and other capitals is on how this event is akin to a firetruck responding to a raging global blaze – of democratic backsliding, proliferating coups, and advancing authoritarianism.

But events in India, Honduras, Gambia, Cuba, and indeed many other countries suggest a more positive role that the summit needs to play as well. For all the frustrations with democracy, many people in all parts of the world still have faith in democratic governance and aspire to the human and political rights that are its foundation.

“The democratic recession of the last 15 years is real, but it’s not a uniform tendency – just as some countries have fallen backward, some have moved forward,” says Thomas Carothers at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington.

“A democratic recession doesn’t mean people around the world have lost interest in democracy. What we see is that many people want to live in free societies,” he adds. “This summit is a good opportunity to recognize that, and for the United States to show it’s going to be there supporting and nurturing this desire.”

Democracy under siege? At summit, there’s more to the story.

Farmers in India, voters in Honduras and Gambia, even protesters in communist Cuba – what they have in common is some recent victory secured through the exercise of rights guaranteed in democratic governance.

As President Joe Biden hosts more than 100 countries for his promised Summit for Democracy Thursday and Friday, much of the talk in Washington and other capitals is on how this summit is something like a firetruck responding to a raging global blaze – of democratic backsliding, proliferating coups, and disaffection with democracy’s ability to deliver.

But events in India, Honduras, Gambia, Cuba, and indeed many other countries suggest a more positive role that the summit needs to play as well. For all the frustrations with democracy and evidence of authoritarianism’s march, many people in all parts of the world still have faith in democratic governance and aspire to the human and political rights that are its foundation.

If millions of farmers in India were able to force Prime Minister Narendra Modi to back down on deeply unpopular farm laws last month after a year of nonstop protests, it was largely because farmers believed their rights under India’s democracy could bring a change.

Likewise, Honduran voters last month rejected an incumbent president – and warnings from the military and economic elites – to elect a leftist (and the country’s first female) president. And in Gambia, voters this week decided to keep their incumbent president in the country’s first election without a dictator on the ballot.

Even in Cuba, a movement pressing for political freedoms and economic justice – and led largely by social-media-wielding young people – has at least managed to win government acknowledgment that living conditions need to change.

Given a global landscape where hopes for democracy remain just as salient as the much-touted frustrations, many democracy experts and pro-democracy activists say the task for Mr. Biden’s initiative will be as much about bolstering the world’s democratic aspirations as it is about addressing the challenges.

“The democratic recession of the last 15 years is real, but it’s not a uniform tendency – just as some countries have fallen backward, some have moved forward,” says Thomas Carothers, a leading authority on international support for democracy, human rights, and civil society at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington.

“A democratic recession doesn’t mean people around the world have lost interest in democracy. What we see is that many people want to live in free societies,” he adds. “This summit is a good opportunity to recognize that, and for the United States to show it’s going to be there supporting and nurturing this desire for democratic governance and freedoms.”

Freedom House, the Washington-based human rights and civil liberties organization known for its annual freedom index, reports finding growing support for democracy, even as its annual surveys find widespread retreat from political freedoms – including this year within the United States.

“We definitely see enormous support among populations and average people for the concept of democracy, while what has been declining is support for those in power” amid disappointment in the way democracy has been practiced, says Sarah Repucci, vice president of research and analysis at Freedom House and co-author of a recent report delving into 15 years of democratic backsliding.

“People have been willing to go into the streets in support of the democratic rights they have,” says Ms. Repucci, citing the “mass movements” that have shaken the world, from Hong Kong to Chile, since 2019. “Often those actions have been most intense when rights have been interrupted or challenged,” she adds, “in cases like Belarus, Myanmar, Sudan, or the successful movement we’ve seen among farmers in India.”

Response to China

For some, Mr. Biden’s summit for democracy is really about China’s rise and challenging the seemingly rising appeal of an authoritarian model Beijing touts as more effective at meeting 21st-century challenges. The summit is organized around three “pillars” or themes: defending against authoritarianism, fighting corruption, and promoting respect for human rights.

But some Asia experts counter that if anything, support for democracy in the region is higher than ever because of the authoritarian example China is setting.

“What we’re seeing in surveys of Asia is that the U.S. is losing its mojo and China is rising. … But at the same time we’re seeing higher support than ever before for democratic norms, less support than ever before for autocracy,” says Michael Green, senior vice president for Asia at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “The trend is definitely towards support for democracy and democratic principles as the defining norms for Asia.”

Mr. Green, who served as special Asia assistant in the National Security Council under President George W. Bush, cites evidence beyond surveys including creation in Japan’s Diet of a human rights caucus, and new initiatives in Japan, South Korea, and Indonesia, to support regional democracy.

And then, he says, there’s the “Milk Tea Alliance.” The online democracy and human rights movement powered by self-described “netizens” from Hong Kong and Taiwan to Thailand and Myanmar is aimed at undercutting authoritarianism and advancing democracy.

The group even has its own flag: a three-striped standard with the brown tones of Thai, Hong Kong, and Taiwanese milk tea.

“This is a movement inspired by the Gen Xers and young activists of Hong Kong who … have said, ‘We will die for democracy,’ and which has taken hold in East Asian societies that look like Hong Kong,” Mr. Green says.

Grassroots engagement

Given the global context, many experts say the Summit for Democracy will only be successful in its aim to “revitalize democracy around the world” if it manages to reach beyond leaders and elites to the populations looking for more responsive governments.

“I do think the summit is an opportunity for leaders to show that democracy can deliver on what people care about,” says Ms. Repucci. “But I think the way we extend it beyond the elites is to make the very firm and material commitments to the civil society that is doing the hard work of fighting for democracy.”

It appears the Biden administration received that memo. In pre-summit briefings and interviews, administration officials have underscored how civil society will be engaged both this week and over the coming “year of action” that the summit will launch.

“We are engaging human rights defenders and highlighting the role of independent media and political activists [as a way to underscore] that what’s most important is to robustly involve civil society,” says a senior administration official involved in developing the summit agenda. Noting that local leaders including mayors have also been involved in the summit process, the official adds, “We really want the summit to be about entire societies.”

Still, for many analysts, the proof will be in the pudding of the coming year. Some worry that more time and energy was spent on the summit guest list – a process that led to global controversy over who’s in and who’s out – than on setting the global stage for quick and meaningful action.

Others caution that some in the world may remain leery of an initiative driven by the U.S., which is seen as experiencing its own democratic backsliding and often acting more in its own self-interest than for a global good.

“My sense is that a global level of discussion around democracy tends to only engage with elites … and rarely reaches the average person, [while] a U.S.-led initiative will lead to a specific engagement with specific international partners,” says Bittu Rajaraman, head of the psychology department at Ashoka University in Haryana, India, and a human rights activist.

The U.S. will have to overcome a sense that a “somewhat hypocritical U.S. is [promoting] a U.S. national agenda and not … issues of global justice,” they add.

Others see a world hungry for a strengthening of the democratic norms Mr. Biden wants to support, but add that the year ahead will tell if the U.S. can turn rhetoric into action.

“There’s certainly a lot for the Biden administration to work with,” Mr. Green says. “But what I see is that they haven’t done that much yet to engage and build on the support for democracy that’s out there.”

Plastic as fuel? Why ‘advanced’ recycling gets mixed reviews.

Converting plastic waste to fuel – instead of piling it up in landfills – sounds like a path to progress. Our reporter explores whether “advanced recycling” is a viable solution or a sham.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Xander Peters Special correspondent

In places like Baytown, Texas, ExxonMobil and others in the petrochemical industry are moving to expand an approach to plastic waste that they call “advanced recycling.”

Prior to an industry rebrand, the method was referred to as chemical recycling, an energy-intensive process that uses high heat or chemical reactions (or both) to turn plastic waste into new plastic materials or fuels. This stands in contrast to methods in which plastics are melted down but complex molecules remain intact to be reused in new products.

The expansion of advanced recycling comes as citizens globally are awakening to what many see as a crisis of plastic-waste pollution. Beyond the solid-waste stream, the climate implications are also large. The domestic plastics industry is responsible for annual emissions equal to 116 coal-fired power plants, according to a recent analysis by Beyond Plastics. By 2025, that equivalent could reach up to 150 coal-fired plants.

“Innovation is good. I don’t think we should discourage innovation,” says Sarah Morath, an expert at Wake Forest University in North Carolina. “But I think we should be thinking about innovating at the beginning and not the end of plastics’ life.”

Plastic as fuel? Why ‘advanced’ recycling gets mixed reviews.

Baytown, Texas, is a city that stands in the shadow of the nation’s oil and gas industry. Located only 26 miles from Houston, it’s been home to an arm of the Gulf Coast petroleum corridor for more than a century. Look to the western horizon from Baytown’s east side in the evening and you’ll see a smear of orange, red, and yellow pastels blending into the Texas sunset, as it slips away behind the nation’s largest petroleum refinery.

The city is also among the key sites for the oil and gas industry’s next significant pivot.

ExxonMobil has already broken ground on an operational “advanced recycling” facility that it hopes to open next year. The operation is expected to be among the continent’s largest, with a capacity to recycle up to 30,000 metric tons of plastic waste annually. And it’s part of a petrochemical industry trend with global scope. ExxonMobil is building a similar facility in Notre Dame de Gravenchon, France, for example.

The idea is to expand heat-intensive recycling methods for materials that aren’t amenable to more traditional recycling.

This may sound like a win for the environment – a way to responsibly handle waste at a time when China is doing less of the world’s recycling than it used to. The industry’s expansion, however, is being met with skepticism by many recycling experts, who cite a lack of evidence demonstrating advanced recycling’s effectiveness.

“This a way for the petrochemical industry to sort of signal that they’re responding and being responsive to some of these concerns that the public is raising” about the plastics crisis, says Sarah Morath, an associate professor of environmental law and food law at Wake Forest University and the author of the forthcoming book, “Our Plastic Problem and How to Solve It.”

Yet she and other experts say advanced recycling is far from a simple and clear-cut solution.

Public concern about plastic

Prior to an industry rebrand in recent years, advanced recycling was referred to as chemical recycling, an energy-intensive process that uses heat or chemical reactions (or both) to recycle plastic waste into new plastic materials, fuel such as diesel and jet fuel, and other chemicals.

This method stands in contrast to a less-polluting process called mechanical recycling in which plastics are melted down but their complex molecules remain intact to be reused in new products. And many environmentalists say the best answer, for reducing humanity’s emissions and the waste that clogs roadsides and oceans, is to learn to use less plastic in the first place.

The expansion of advanced recycling comes at an important moment. The oil industry is exploring new business models as the world increasingly seeks to curb the use of fossil fuels due to climate change. Meanwhile, U.S. consumers are questioning their habits of heavy reliance on single-use plastics. A 2019 survey by PBS Newshour and Marist Poll found that roughly two-thirds of Americans – 66% – would pay at least 1% more for single-use daily items that are environmentally sound, as compared to single-use plastics, which break down into tiny particles and never truly degrade and disappear.

In fact, citizens globally are awakening to what many see as a plastics crisis, in large part spurred by data such as what researchers found in a 2018 study in the journal Science Advances: Of the more than 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic ever produced – single-use utensils, water bottles, grocery bags and more – 6.3 billion metric tons have been tossed aside as plastic waste. Only 9% of that waste has been recycled in plastic’s roughly 70-year history.

“A way to liquefy plastic and burn it”

Beyond the solid-waste stream, the climate implications are also large. The domestic plastics industry is responsible for the equivalent of 232 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually – roughly equal to 116 average-size coal-fired power plants, according to a recent analysis by Beyond Plastics, a think tank at Bennington College in Vermont. By 2025, that equivalent could reach up to 150 coal-fired plants.

The report also noted the unequal burden of pollution shared among communities. In fact, 90% of the reported pollution from the U.S. plastic industry is released into just 18 communities – the Houston/Baytown area topping the list.

Advanced recycling is pitched by many in the industry as a closed loop solution to the plastics crisis, in that instead of plastic waste ending up in landfills, it’s converted to a usable substance.

ExxonMobil did not respond to the Monitor’s request for comment and for information on advanced recycling yields, what pollutants are measured, and how much energy is used.

Matthew Kastner, director of media relations at the American Chemistry Council, describes the industry group as “very supportive of advanced recycling,” calling it “the solution to recycling more types and volumes of plastic packaging,” which would reduce the amount of plastic going into landfills. As the group points out, since 2017, $6.7 billion in advanced recycling investments have been made in the U.S.

“There are many environmental benefits made possible by plastics,” Mr. Kastner says in an emailed statement. “Plastic enables the products we need for a lower carbon future, such as lighter vehicles, wind turbine blades, and building insulation, that either reduce greenhouse gas emissions by saving energy or create renewable energy. In addition, plastic packaging requires less material by weight to perform many of the same functions as glass, paper and metal, and is lighter to transport compared to most other packaging materials, which helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

Neil Tangri, science and policy director at the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, worries advanced recycling is “another red herring to distract us from the need to reduce the amount of plastic that is produced.”

Last year, the group produced a report that looked into the 37 advanced recycling facilities proposed since the early 2000s. Only three are currently operational – two of which are plastic-to-fuel projects – and none of the current facilities have successfully recycled used plastic waste into new plastic or fuel, the researchers learned based on publicly available information.

“That’s not recycling at all, you’re just finding a way to liquefy plastic and burn it,” Dr. Tangri says of their findings. The industry is “a boondoggle, really. It’s the latest in the industry’s long line of arguments that plastic isn’t a problem, because we have a technological solution to it.”

Amid the concerns about advanced recycling, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently offered a period for public comments (through Nov. 8) on how the industry should be regulated under the Clean Air Act.

In states, however, groundwork has already been laid for the advanced recycling industry to grow in coming years. In July, Louisiana lawmakers unanimously approved a state bill allowing advanced recycling. Louisiana’s action aligns with at least 13 other states that have enacted or proposed laws in recent years to deregulate the use of pyrolysis and gasification – the heat and chemical reactions used in advanced recycling – reclassifying the process as manufacturing.

Options on plastic waste

There are better ways of combating the plastics crisis, says Winnie Lau, a senior director at Pew Charitable Trusts, which has researched the issue.

“[There’s] no silver bullet, despite what anyone in any sector might claim. The only way we can actually solve this problem is to implement systemwide solutions,” she says. That means actions addressing consumer awareness, how plastic products are being manufactured, and how better to deal with the waste.

Up-front reduction – producing and using less plastic – will “be the most effective, because what you don’t produce, you don’t even have to worry about dealing with at the end,” Dr. Lau says.

The Pew analysis sees the opportunity to reduce plastic pollution by 80% over the next two decades. But that’s if every actor, including government and companies, invests an effort in doing so – a sentiment that’s shared among researchers.

Dr. Morath at Wake Forest also calls for a redesign of consumer products.

“If we’re going to continue producing plastic-type products, because we like durability, we like lightweight, we like those kinds of longevity, all those great characteristics of plastic, let’s think about designing plastics that are going to biodegrade and be less harmful once they’re in the environment.”

Many say the need is for less single-use packaging, whether made of plastics or other materials.

“Innovation is good. I don’t think we should discourage innovation,” says Dr. Morath. “but I think we should be thinking about innovating at the beginning and not the end of plastics’ life.”

Brazilian ‘wonder berry’ offers farmers and the Amazon a future

Most of the world knows the açaí berry from smoothies and breakfast bowls. But amid the deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon, the açaí tree offers an alternative, sustainable lifeline to small farmers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Ana Ionova Correspondent

In Brazil, cattle ranchers, timber merchants and land grabbers are felling the Amazon jungle faster than ever before. “They cut, cut, cut,” complains a local farmer, Nelson Galvão, and in his view, that’s what accounts for the worst drought in a century that hit the Amazon this year, and the flash floods that followed.

Mr. Galvão is working hard to make a living without destroying the forest; he cultivates açaí palms, which yield a tart berry native to his local rainforest that has become a globally coveted superfood among the health-conscious.

He is onto a good thing. Brazilian açaí exports are leaping by 50% a year, and the world market for the fruit is worth about $720 million.

But deforestation, and the resulting climate change, is threatening that business; experts say the rainforest runs the risk of turning into a savanna, and that would be the end of açaí.

“It all worries me, of course,” says another local farmer. “But we are doing our part. We’re planting trees.”

Brazilian ‘wonder berry’ offers farmers and the Amazon a future

Squinting into the late afternoon sun, Nelson Galvão leans against the trunk of a towering açaí palm. About 20 feet above his head, nestled into the crown of the palm, clusters of deep-purple berries weigh down the tree’s slender branches.

“Açaí has been good to us,” Mr. Galvão says. “If you know how to care for it right, it brings in a good income. It’s our family’s survival.”

For the last two decades, Mr. Galvão has been cultivating açaí, a tart berry native to the Amazon rainforest that has become a global health food sensation and a business worth nearly a billion dollars a year. About 2,000 açaí palms grow on his lot here, some 70 miles from the Amazon capital of Manaus, yielding enough pulp each harvest to earn him about $2,150, the equivalent of a minimum wage.

Mr. Galvão is working hard to make a living without destroying the forest. Instead of toppling trees, he restores the land by planting banana, pineapple, and cupuaçu – a close relative of cacao – in the gaps between his palms.

“Growing up, I saw my parents clearing big pieces of land, clearing everything,” Mr. Galvão says. “Now I know that, if we just destroy without restoring, all this will come to an end.”

Many of Mr. Galvão’s neighbors have chosen a different path though. The emerald jungle canopy here is fast giving way to cattle pasture, as in much of the Brazilian Amazon, and Mr. Galvão is feeling the impact.

Açaí palms usually thrive in this sun-drenched corner of the Amazon, where flood plains swell during the rainy season to form a maze of land and water. This year, though, his trees yielded less as Brazil was hit by its worst drought in almost a century. Then this part of the Amazon was struck by devastating flash floods.

“We see these weather disasters and we really worry. We wonder about future harvests,” he says. “But the cattle ranchers – they are not worried. They cut, cut, cut. They deforest everything. And we, the small growers, are the ones who end up paying the price.”

A “wonder berry” spreads

Mr. Galvão is not alone in his concerns for the future. The Brazilian Amazon is being razed and burned at a dizzying pace, with deforestation hitting its highest level in 15 years, despite government vows to curb the destruction. Scientists warn the rainforest is nearing a tipping point when it will turn into a savanna, with grave consequences for the climate. And açaí – along with other native species – could disappear from swaths of the Amazon by 2050, researchers warn.

“Some areas where açaí palms grow today will no longer be suitable in a future climate scenario,” says Pedro Eisenlohr, professor at the State University of Mato Grosso and co-author of a recent study forecasting climate change in the Amazon.

“This poses a huge problem for the families” living in such vulnerable areas, Professor Eisenlohr says, “because they are counting on açaí for their survival. And it might not be there in the future because of climate change.”

Full of fiber, açaí was a staple food in the Amazon long before it turned into a globally coveted superfood. For generations, Indigenous and traditional people harvested and ate the berries that grow on native palms near rivers at the edge of the jungle.

The popularity of this “wonder berry” spread to gyms and surf shacks across Brazil in the 1990s. Before long, açaí made a name for itself abroad too and quickly amassed a loyal following, making its way into smoothies and protein bars in cities like Los Angeles, London, and Tokyo. Exports have grown more than a hundredfold in the past 10 years.

And the growth has shown no signs of slowing. Last year, exports jumped by 50% from the year before, and globally, the açaí market is now worth about $720 million annually, says Renata Guerreiro, project coordinator at the Terroá Institute, a nonprofit focused on sustainable development in the Amazon.

“It is a real force within the Amazon’s bio-economy,” says Ms. Guerreiro, whose organization runs an initiative promoting sustainable production of açaí. “And it carries enormous potential.”

The surge in demand for the nutrient-packed berry has been welcome news in the Amazon, promising a path to prosperity for small-scale growers. Although some have sounded the alarm over the unbridled growth, fearing growers may raze virgin forest to make space for more açaí, the berry has proved a sustainable source of income for most growers, often cultivated within the forest.

A rare bright spot

Luis Carlos Gomes experienced the açaí boom firsthand. When he was growing up, the fruit was a lunch staple rather than a business opportunity. When he started planting the berry 12 years ago, he was one of few growers in Autazes excited about its potential. But soon that changed.

“Before, there was no market for açaí,” Mr. Gomes says. “People only picked it for their families to eat. But, all of a sudden, our açaí started selling and selling. And other people got excited about planting it too.”

Mr. Gomes, one of the largest producers in the Autazes region, is making big plans for the future too. He hopes to start an açaí producers’ association, and he wants to plant more açaí on his 14-hectare lot, expanding from 8,000 palms to about 10,000.

“Out there in other countries, açaí has become well known and much loved by people,” he says proudly. “We hope the demand will only grow.”

Today, some 120,000 families live from açaí production across Brazil, cultivating about 1.6 million metric tons of fruit per year, Ms. Guerreiro says. Further benefits could be gained if Brazilian companies processed more of the fruit locally.

The industry has come in for criticism due to allegations about the use of child labor, but as the destruction of the Amazon advances, açaí has emerged as a rare bright spot in the fight to save the rainforest. Projects promoting the sustainable cultivation of the berry aim to make preserving the forest more lucrative than razing it. In already deforested areas, planting more açaí is also helping restore degraded forests while providing local people with an income.

“Açaí is really important for the generation of sustainable income in the Amazon,” Ms. Guerreiro says. “And it’s also a key to preservation, as long as it is grown in a way that minimizes impact ... and its expansion is done in a sustainable way.”

Now that climate change is threatening the açaí palms, environmentalists worry that some growers, unable to make a living from the forest standing, will move to raze it, turning the land into pasture.

Mr. Gomes also worries about what climate change might mean for his açaí trees. Still, for now, he says the future is bright.

“The droughts, the floods – it all worries me, of course,” he says, steadying a ladder as his son climbs up a palm in search of the very last berries of the harvest. “But we are doing our part. We are planting trees. And we’re putting our faith in açaí.”

Essay

After defeat: Lessons learned coaching high school football

In this moving essay, a high school football coach finds inspiration in his players, and in the gains realized even in defeat.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Martin A. Davis Jr. Correspondent

This was no ordinary Saturday. It was the first Saturday after our loss in the Virginia high school football playoffs, which ended our season. Losing in the playoffs is never enjoyable, but when you fall 58-3, well, it hurts.

As a coach, I realize there are certainly moments when coming back and winning isn’t going to happen. And there are moments where you feel utterly helpless, as whatever you call fails to achieve the desired results.

The only option is to keep coaching.

You coach for those who still have to take the field and play the game. You coach for the younger players who are coming back. And you coach for the players for whom this was the last time they would put on a high school football uniform. They were still playing the game they loved. Still making memories. Still enjoying the moment.

Coaching to the very end is the best way I know to thank them for all they gave their team. Tomorrow, the sun will come up again. And rising to face it is its own reward.

After defeat: Lessons learned coaching high school football

The sun came up this morning. The dog needed walking, as he does every morning. And the usual Saturday routine – grocery shopping, lunch with my wife, strolling through knickknack shops in our beloved downtown Fredericksburg – was still in place.

These are the little joys that I embrace every Saturday.

Opening my email, however, I was quickly reminded that this was no ordinary Saturday.

It was the first Saturday after our loss in the Virginia high school football playoffs the night before, which ended our season. Losing in the playoffs is never enjoyable, but when you fall 58-3, well, it hurts.

A friend who had attended the game had written to extend his regrets on the loss, and to ask a question. “We walked in about 3 minutes before halftime,” he wrote, “and as soon as I saw the score board I knew it was [going to] be a lopsided loss. … I’m curious how you coach in those situations.”

I tripped over his words. There are certainly moments when, as a coach, you realize that coming back and winning isn’t going to happen. And there are moments where you feel utterly helpless, as whatever you call fails to achieve the desired results.

The only option is to keep coaching.

You coach for those who still have to take the field and play the game. When we were down by 41 in the fourth quarter, I was on the sideline teaching a young man to play a position he didn’t normally play because our starter was injured. There was no other backup; I had to prepare my players for the possibilities.

You coach for the younger players who are coming back. When we were down by 48, I was talking with my punter about how to get his kicks away quicker. It would make no difference tonight. But for the Friday nights that lay before him, it will.

And you coach for the players for whom this was the last time that they would put on a high school football uniform. With every snap, they were still playing the game they loved. Still making memories. Still enjoying the moment.

Coaching to the very end is the best way I know to thank them for all they gave their team.

A photo of one of our seniors taken right after the game reminded me how much we owe these players.

When the shutter snapped, the stadium lights still illuminated the dark skies. The young man was down on one knee, helmet in his right hand resting on the turf, his head hung.

Most people still at the stadium, no doubt, saw this and felt sadness. They saw pain and they saw loss. But they only saw this singular moment in time.

I spoke with that player Saturday morning about what he was thinking when the shot was taken. The hurt and the sting of loss were there, to be sure, but what he was focused on was the past four years. The ups and downs. The friendships. The tribulations. The relationships he’d formed with his teammates and his coaches. And he was thinking about the final moments of his playing career. His final block. His last tackle. His last time breaking the huddle.

It was a moment of thankfulness for every snap he’d played. Every practice he’d endured. Every injury he’d fought through.

And when the stadium lights finally fell, it would not be the darkness he dwelled on. His eyes were on his life ahead.

What football has taught him, and what it is still teaching me, is that every day, every collective experience, ends the same, with a sunset. And in that moment, it is good to reflect on all that has gone before.

But, the sun always comes up in the morning. And rising to face it is its own reward.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The core mission of the democracy summit

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One unintended consequence of President Joe Biden’s Dec. 9-10 Summit for Democracy is all the complaining beforehand about the 110 nations attending. Critics in many countries asked if their governments can really be called a democracy with so much political favoritism, hidden wealth, bribery, and so on. Critics in the United States were no exception.

But that’s the point. A country’s self-criticism about corruption, made possible by freedom and a bias toward integrity in governance, is the bedrock of democracy. In contrast, dictators squelch public deliberation to hide the stealing of public resources that helps keep them in power.

Mr. Biden made sure the summit is not only about improving the mechanisms of democracy or joining forces with other democracies against a rise in autocracies. Corruption, he says, “is nothing less than a national security threat in the twenty-first century.” It forces democracies to demonstrate “the advantages of transparent and accountable governance.”

The core mission of the democracy summit

One unintended consequence of President Joe Biden’s Dec. 9-10 Summit for Democracy is all the complaining beforehand about the 110 nations attending. Critics in many countries asked if their governments can really be called a democracy with so much political favoritism, hidden wealth, bribery, and so on. Critics in the United States were no exception.

But that’s the point. A country’s self-criticism about corruption, made possible by freedom and a bias toward integrity in governance, is the bedrock of democracy. In contrast, dictators squelch public deliberation to hide the stealing of public resources that helps keep them in power.

Mr. Biden made sure the summit is not only about improving the mechanisms of democracy or joining forces with other democracies against a rise in autocracies. Corruption, he says, “is nothing less than a national security threat in the twenty-first century.” It forces democracies to demonstrate “the advantages of transparent and accountable governance.”

Days before the summit, Mr. Biden unveiled the first U.S. strategy on countering corruption. It is aimed mainly at bolstering federal agencies to watch for illicit money flows, whether in U.S. assistance to foreign militaries or the purchases of U.S. real estate by foreign corrupt elite. He also expects countries to bring their own anti-corruption commitments to the summit and be held accountable at a followup summit next year.

Such self-reflection is essential. The world’s democratic decline is driven by a loss of trust in governments that comes with a rise in corruption. Or, as the world’s leading anti-corruption watchdog Transparency International puts it: “The corruption problems that established democracies face at home diminish their ability to confront the rising authoritarianism around the world.”

Cleaning up graft has another benefit. “Nothing gets under the skin of dictators more than democracies working together and confronting corruption,” says Rep. Tom Malinowski of New Jersey.

It was probably not a coincidence that opening day of the democracy summit is also International Anti-Corruption Day. Global efforts against corruption barely existed four decades ago. Now at least half of recent pro-democracy protests in countries from Sudan to Myanmar were driven by popular demands for clean governance. Many leading political dissidents, such as Russia’s Alexei Navalny, are primarily anti-corruption fighters. And according to the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, the world has never had so many investigative reporters working to expose corruption.

Mr. Biden’s summit is riding a wave of global activism to revive the ideals of democracy, starting with the self-criticism that helps sustain the social contract in each democracy.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Be a fact-checker

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Kent Garland MacKay

Learning more about God’s nature and our relation to the Divine enables us to prove the spiritual fact of God’s goodness, which brings about healing.

Be a fact-checker

My first job after college was fact-checking in the copy-editing department of a women’s magazine. I had to verify that the dates, addresses, names, and events in each article were correct. These facts were often crucial to the substance of a story.

Facts are even more important in a science, such as astronomy or geology. And to take it even further, the Science of Christianity, discovered by a 19th-century seeker of truth, Mary Baker Eddy, includes what she calls “the spiritual facts of being” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 312).

One day I was fascinated to discover in Mrs. Eddy’s writings the phrase “the great fact.” In her major work, Science and Health, Mrs. Eddy says, in instructing her readers how to heal, “Insist vehemently on the great fact which covers the whole ground, that God, Spirit, is all, and that there is none beside Him” (p. 421).

In the same chapter, she writes, “The great fact that God lovingly governs all, never punishing aught but sin, is your standpoint, from which to advance and destroy the human fear of sickness” (p. 412).

To me, the phrase “the great fact,” which appears numerous times in Mrs. Eddy’s writings, serves as a kind of spotlight to alert the reader to truths basic to this Science and crucial to demonstrating it in healing. This term often references the nature of God as the one and only Being, omnipotent and omnipresent.

Mrs. Eddy also shares great facts about man – everyone’s true identity. For example, “The great spiritual fact must be brought out that man is, not shall be, perfect and immortal” (Science and Health, p. 428). How reassuring that the concept of man’s spiritual perfection is not a theory but a reality that we can discern through our God-given spiritual sense.

This is the wonderful thing about the truths of spiritual being articulated in Christian Science. They are not philosophical abstractions but provable facts. They form a basis for earnest prayers to our loving Father-Mother God and are manifested in harmonious human circumstances as we let the active presence of God, good, assert itself in our thoughts. Based on the fact of God’s nature as infinite good, effective prayer challenges the reality of any opposition to good and emphasizes the pervasiveness, activity, and preeminence of good.

These metaphysical facts articulate grand verities prominent in the Bible, such as “Neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Romans 8:38, 39). Understanding these primal and immortal facts can bring healing.

While doing housework one day, I made an abrupt move that caused immediate discomfort in my lower back. Every time I sat down, lay down, or stood up, there was an intense muscle spasm.

When I requested prayerful help from a Christian Science practitioner, she replied, “That spasm is not telling you one fact about yourself.” She pointed out that healing consists of revealing our already-existing, God-endowed perfection. God, good, is infinite, and therefore evil can’t claim to have power. I saw that when conscious of good, I can’t be conscious of evil.

Over the next several days I devoted myself to maintaining these spiritual facts in thought. Deepening my study and prayer, I found this idea to be especially meaningful: “The scientific sense of being ... undermines the foundations of mortality, of physical law, breaks their chains, and sets the captive free, opening the doors for them that are bound” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 101). In two weeks, I was released from the “chains” I’d been experiencing – the feeling of injury – and once again enjoyed painless, wide-ranging freedom of movement.

Only once during the next 25 years did I experience anything wrong with my back, and that time, too, the problem was quickly healed.

Each of us can be a fact-checker and check out the great facts found in the Bible and Science and Health – the demonstrable truths of God and His beloved creation. Pondering and treasuring them brings about healing views of our thoroughly spiritual, all-harmonious being.

Adapted from an article published in the Nov. 15, 2021, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Let it snow

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: Our film critic looks at what Steven Spielberg brings to the Hollywood remake of the 1961 classic, “West Side Story.”