- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How motherhood made me a better reporter

A decade ago, I took my baby daughter with me on a reporting trip to Kenya. She was still nursing and would howl for hours if I tried to put her down. But I figured she was portable. Motherhood, I had decided, was not going to change the way I worked.

So, I strapped her into a carrier. I paced the airplane aisles to keep her quiet. I rocked her all night under a mosquito net. It was, in a word, exhausting.

I hadn’t thought about this trip for years. But then Joellen Russell told me about pumping milk on a dirty airport floor. She was traveling across the United States to build a scientific collaboration focused on ocean warming. She had also decided that being a mother wouldn’t affect her career.

There are some moments as a journalist when you recognize a story that’s particularly connecting, universal. For years, mothers in the workplace have gotten the message that it’s best to pretend your kids don’t exist. Resilience, we have imagined, means carrying on just as before they were born.

But Dr. Russell came to challenge this. She is part of a new group called Science Moms. They connect with non-scientist mothers to spread information about climate change and talk explicitly about the way they feel as parents looking at the Earth’s future. This is a big shift. It’s a full reframe of parenthood, science, and resilience. They have recognized that rather than undermining their work, their children are the rock beneath it. Climate change can be distressing. But as one scientist told me, when you’re fighting for your babies, there’s no such thing as giving up.

I write about climate change for the Monitor. I now feel a responsibility to search for characters like Dr. Russell, to share fierce, clearsighted stories that combat despair, build connection, and encourage progress. My daughter is 10 now, and her sister is 8. They have changed the way I work. I am grateful.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Meet the scientist moms fighting climate change for their children

A group of female scientists is trying to overcome climate “doomerism” – the idea that nothing can be done to stop global warming. For them, it’s not just about the science but about values: how the issue affects families.

When it comes to climate change, despair is not in short supply. For all the progress made, the challenges remaining can seem insurmountable.

At the same time, there is a growing movement not only to show the way climate systems are changing, but also to fight so-called climate doomerism.

Meet the Science Moms.

The movement’s motivations are multifaceted: to promote solutions-based dialogue and research on climate change, to meld members’ values and roles as scientists and mothers, and to fight the stigmas holding back female researchers and scientists.

Joellen Russell’s journey serves as an example. Over her career, the University of Arizona climate researcher has expanded her understanding of resilience from something personal to a collective force, from scientific achievement to a broader embrace of humanity. Her story is a mirror, in many ways, of the approach to global warming writ large: how people, groups, and societies around the world are beginning to integrate climate into the way they think, live, and act.

“I finally found my united voice,” Dr. Russell says. “It turns out that my students and my community members and my kids’ classroom teachers and all the rest of them were waiting for me to shake off the shackles of ‘just the science’ and talk to them about the values part. And I am thrilled.”

Meet the scientist moms fighting climate change for their children

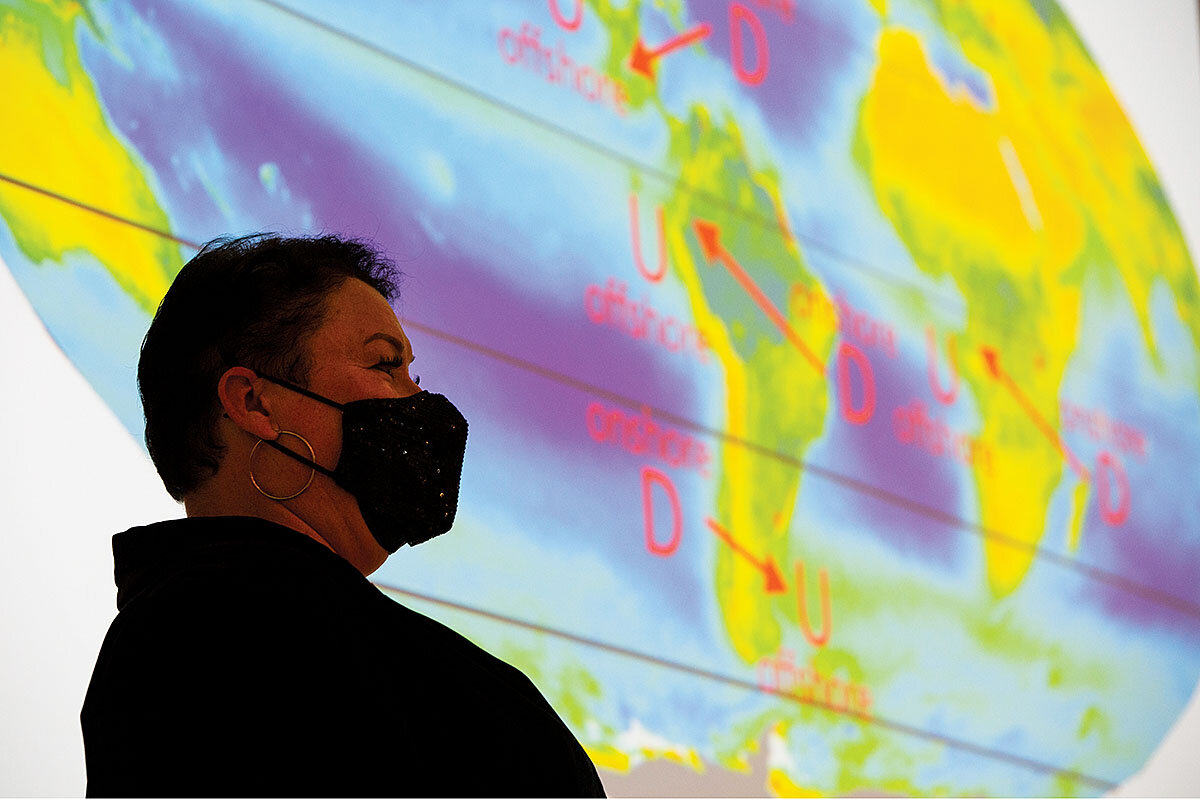

Joellen Russell likes a big class. The bigger the better, actually, with online sections and huge auditoriums and students swarming her after a lecture – the way they did one Thursday morning this fall after her Intro to Oceanography course at the University of Arizona.

“Wait, Dr. Russell, I’m not sure about the homework.”

“What about the jet stream?”

“Dr. Russell! I saw your sweet family at CVS!”

The distinguished professor stays onstage, laughing, joking, answering question after question, until finally she suggests that anyone else who wants to talk should visit her during office hours, which she holds at a picnic table outside.

“It’s a bit of a circus,” she says as she walks out of the voluminous lecture hall. “But, I like it when it’s noisy. I like it when they want to talk and they want to tell you things and they want to ask things.” She grins, as if getting away with something. “It’s fun.”

The university’s administrators have suggested that perhaps Dr. Russell might want to teach smaller, more exclusive seminars. That, after all, is what’s typical for tenured professors with named chairs and multimillion-dollar grants and international partnerships on the cutting edge of scientific research. But Dr. Russell knows that students who take her introductory class are more likely than other undergraduates to enroll in another science course. They are also more likely to graduate. And that, she believes, means they are more likely to join her in what she sees as the biggest, most important fight for humankind today – a battle not only against climate change, but also against those who say there’s nothing anyone can do about it.

And she wants to grow an army of resilience.

“My job is not to just advance the science,” she says. “It’s to build the next front lines. I launch as many as I can.”

Dr. Russell is not alone in this mobilization. Across the scientific world, there is a growing movement not only to show the way climate systems are changing, but also to fight what has become known as climate “doomerism,” the idea that there’s simply nothing we can do about global warming, whether because of China’s coal plants or domestic ignorance or just that we’ve run out of time. This effort is founded on resilience – both collective and personal. Many of the key players in this rejection of despair are women. Many are mothers. And many are taking aim at long-held norms and assumptions of the higher education establishment, whether it’s what type of classes to teach, how research is shared – or, most recently, how scientists incorporate their families into their work. One new group, called Science Moms, is working to take this movement public, connecting female climate scientists who have children to other mothers in an effort to spread information about climate change.

“Women are creating space for different kinds of reactions to the climate crisis and opening up that conversation,” says Jacquelyn Gill, a climate scientist and paleoecologist at the University of Maine in Orono. “The discourse itself has changed.”

Dr. Russell’s journey is an example of this. Over her career, she has expanded her understanding of resilience from something personal to a collective force, from scientific achievement to a broader embrace of humanity. Her story is a mirror, in many ways, of the approach to global warming writ large: how people, groups, and societies around the world are beginning to integrate climate into the way they think, live, and act.

“I finally found my united voice,” Dr. Russell says. “It turns out that my students and my community members and my kids’ classroom teachers and all the rest of them were waiting for me to shake off the shackles of ‘just the science’ and talk to them about the values part. And I am thrilled.”

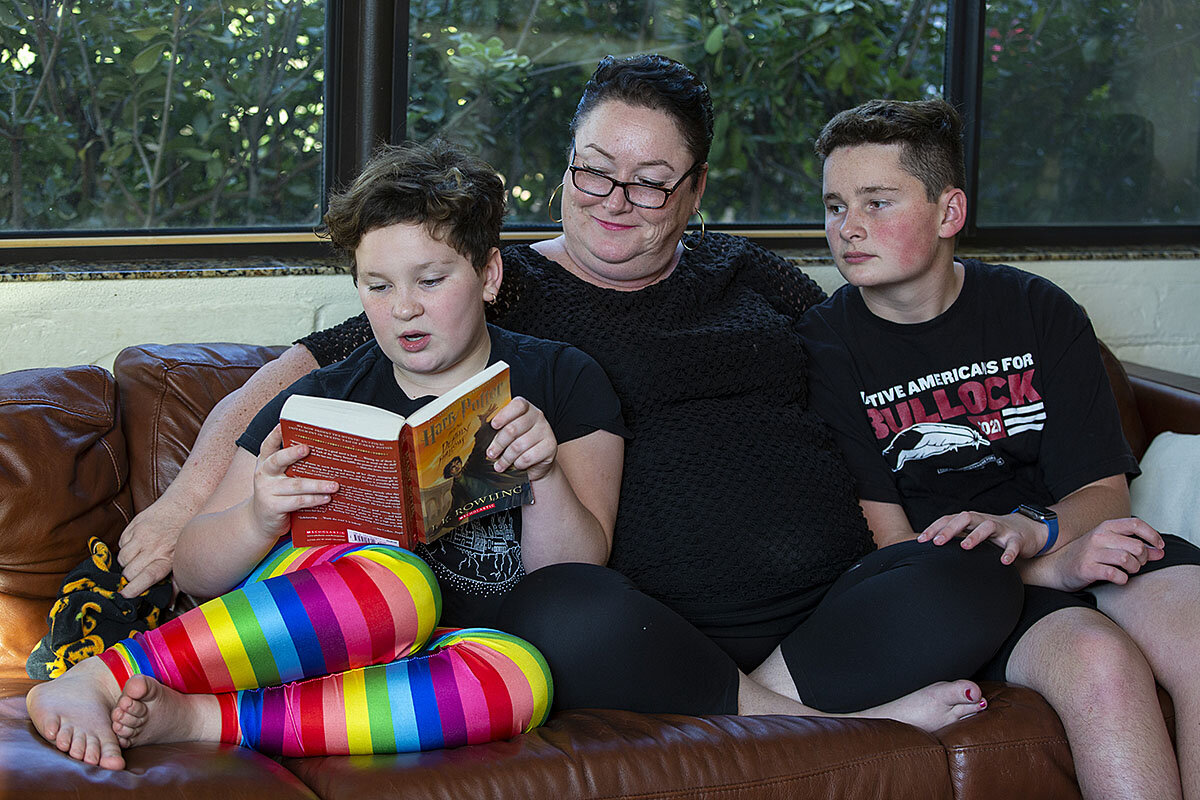

For her, this new kind of resilience starts with Joseph and Maeve. Joseph is 14 years old now; Maeve is 11. And not all that long ago, Dr. Russell says, she would have been uncomfortable talking about her children at work. Not because she didn’t adore them. To the contrary, she has been enthralled with these “smoochie babies” since before their births. She snuggles with them on the couch, reads “Harry Potter” to them at night, and splashes with them in the pool. But she learned early that in the geophysical sciences – a field in which only 27% of U.S. faculty members are women, according to one recent study – motherhood was suspect.

That lesson seemed to come from everywhere. As a graduate student making her first expedition to the Southern Ocean, Dr. Russell had to take a pregnancy test before being allowed on the research ship. That’s still standard practice, she says. “No man knows how that feels,” she says.

She had colleagues who called women with children “breeders”; she knew the stories of friends denied positions because supervisors suspected they would “just get pregnant and leave.” And while there were a growing number of women joining the scientific ranks, very few had families.

“It was just normal to not have kids if you wanted to be a scientist, at least in the fieldwork-type sciences,” she says.

So when, by surprise, she became pregnant soon after she got to the University of Arizona, Dr. Russell panicked. There were no other mothers on the tenure track in her department. Her husband, Paul Goodman, was also an academic but had left his prior position so she could take the job in Tucson. Hers was their primary salary. When she Googled “maternity policy” for the university, she discovered that there was no paid leave.

For 4 1/2 months, she tried to hide her pregnancy. She kept thinking about an experience she had as an undergraduate at Harvard University in the early 1990s, when she had joined a research team in Hawaii, trudging through mud in the Alakai Swamp, collecting soil samples with two male professors and a female postdoctoral student. Dr. Russell recalls the postdoc pulled her aside at one point, frantic. The young woman was pregnant but had been trying to hide it because she thought it would threaten her position, which was up for review.

“So we sneaked all of her gear into my backpack so that she wouldn’t have to carry anything,” Dr. Russell says. “It was over 125 pounds; I weighed 130. And I lifted that freaking pack and I carried it out because ... the idea that they would find out, or that she would lose the kid ...” she trails off.

The men never knew what was going on. The postdoc eventually had a healthy baby and kept her job. But the lesson for 20-year-old Ms. Russell was clear: The way to survive motherhood in the sciences was to pretend your babies did not exist.

Dr. Russell eventually worked up the courage to tell her department chair at the University of Arizona that she was pregnant. But even after the big hug she got in response; even after her male colleagues wandered down the hall to ask whether, just this semester, she might let them teach one of her courses because, well, they’d never taught oceanography before and it might be interesting; even though she recognized that they were trying to lighten her load to make up for the university’s lack of maternity leave – she still was scared, still determined to show that motherhood would not change her work.

That, she thought, was resilience. After all, this sort of determination had always worked for her.

As a child growing up north of the Arctic Circle by the Chukchi Sea, in a Native fishing village where her father worked for the U.S. government’s Indian Health Service, she dreamed of one day following the sea ice, to understand what happened after it broke up and floated away. A relative told her that the best place to learn about that would be the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. The young Joellen scrawled “Scripps or bust” on her Converse sneakers.

When the family moved to rural Montana for her father’s next posting, the local school system did not offer calculus or geometry – skills Joellen knew she would need if she wanted to go to Scripps. She convinced her parents to let her apply to boarding school and was accepted on financial aid to the prestigious St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire. “I wanted to learn. I was so desperate,” says Dr. Russell. “And so I studied and I studied and I studied and I hustled and I hustled.”

When she discovered, to her heartbreak, that Scripps was a graduate program only, and that she would need to go to college first, she applied for financial aid at all the schools her advisers recommended. Harvard gave her the most monetary support, so she went there, waking up each night to the traffic and sirens on Massachusetts Avenue.

From there she did go to Scripps. She also voyaged to the Southern Ocean, where albatross circled the massive waves like fighter jets. She took positions at the University of Washington, and then Princeton, and eventually came to Arizona, where she began building a supercomputer system that would help untangle one of the big puzzles of modern climate science: how the oceans both slow and accelerate atmospheric warming. She was figuring out what happened to the sea ice.

So when she became pregnant, Dr. Russell was determined to continue that work.

When Maeve came, three years later, in 2010, there was still no paid maternity leave. So Dr. Russell put on compression stockings and boarded planes so she could network with colleagues on both coasts to put together a multimillion-dollar interdisciplinary grant application. They wanted to build and deploy hundreds of robot floats with sensors to record temperature, oxygen, and other chemistry at various depths in the Southern Ocean. She lugged a giant, plug-in breast pump to conferences and through airports, sitting with it on the dirty floor of Los Angeles International Airport – the only place near an outlet back then – and hoping none of her colleagues walked by.

Her father flew in from Montana to help her husband when she had work trips. She started investigating how to use artificial intelligence and advanced technology in climate modeling, and continued building out the National Science Foundation-funded SOCCOM, or Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observation and Modeling, project.

At the same time, the climate crisis was accelerating. The 2010s was the warmest decade in recorded history, kicked off by heat waves and wildfires in Russia. Soon there would be floods in Pakistan and Bangladesh, and droughts in East Africa.

Although most nations had agreed to emissions-limiting goals set forth in the 2015 Paris Agreement, in 2019 carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere passed a measurement of 410 parts per million – the highest concentration of the greenhouse gas in 3 million years. That’s the year Dr. Russell became a full professor. More heat waves swept across both the Arctic and Europe. In Tucson, the summers became oppressive. She understood, as thoroughly and intimately as anyone, the mechanisms of what was happening with the climate, and how these extreme weather events were connected to the geochemical data sets she analyzed at work. She was also a parent, distraught when Maeve got heatstroke trying to ride her bike. She woke up earlier and earlier to walk the family dogs so they wouldn’t burn their paws on the pavement.

But that personal world, and any emotions about what was happening to her children’s futures, was something separate from her work. Then, Dr. Russell got an email.

Katharine Hayhoe is a well-known atmospheric scientist who is a distinguished professor at Texas Tech University in Lubbock and chief scientist for The Nature Conservancy. She is also an evangelical Christian, and her work communicating about climate change across political demographics has gained her a sort of celebrity status in the scientific and climate advocacy worlds.

Dr. Hayhoe was reaching out to a group of female climate scientists who were also mothers, she explained, with the goal of building an outreach and awareness campaign. She wanted Dr. Russell to be one of the founding members of the group, which would be called Science Moms.

Dr. Russell remembers hesitating.

By that point she had already been trying, in her own small way, to change the professional norms around parents. She regularly told the younger women in her department – and the younger men, for that matter – that they should have their own lives; that they should have families and babies, if that’s what they wanted; that they should make time for pets and parents. She urged them to take advantage of the university’s paid parental leave program, which the school started offering in 2014.

Dr. Russell believed in sharing research as well, embracing open-source data and encouraging her graduate students to take lead authorship on journal articles. She wanted to avoid the traditional practice of hoarding research for individual glory and instead create a model that was broader and more inclusive.

But to face the world and identify as a mother – that was different. That would require a different type of resilience.

The idea for Science Moms grew out of a collaboration between Dr. Hayhoe and John Marshall, the former chief strategy officer at Lippincott, a marketing consulting firm, as well as Dan Schrag, director of Harvard’s Center for the Environment. Mr. Marshall and Dr. Schrag had formed a nonpartisan nonprofit called the Potential Energy Coalition to, as they put it, “change the narrative” on climate change.

Mr. Marshall had spent years as a successful executive in the advertising and marketing industry when his 17-year-old son suggested, somewhat bluntly, that perhaps he should stop using his skills to get people to spend money and instead make the world a better place. It was a thought-shifting moment, Mr. Marshall remembers.

Soon, he and Dr. Schrag were talking about climate change – a problem that impacted every human on Earth, but one that had become unnecessarily political. They wanted to get more people to both care about climate change and demand action to address it – but without taking a particular partisan or policy stance. After running analytics, Mr. Marshall determined that among all U.S. demographics, mothers age 40-55 were the most likely to be moved on the issue. They were worried about their children’s futures but felt uneducated about climate science and didn’t know what to do about global warming.

Mr. Marshall realized he needed the right messenger to reach this group. He wanted someone who would be trustworthy and relatable, but also knowledgeable. And he knew from his for-profit work that the more authentic the storyteller, the better.

“Our work has focused on elevating new spokespeople, spokespeople that everyday Americans can relate to,” Mr. Marshall says.

At the same time, Dr. Hayhoe had been working on her own efforts to increase the conversation about climate change. In a TED Talk viewed almost 4 million times, she argued that the most important thing people could do to fight climate change was to talk about it – something she and others believed wasn’t happening enough around American dinner tables. She has also written a book, "Saving Us," about what individuals can do to make a difference on the issue.

Mr. Marshall and Dr. Schrag reached out to Dr. Hayhoe to share their marketing research and get advice. Soon, the three coalesced around the idea for Science Moms – a way to bring together a group of climate scientists who were mothers to connect with other mothers in their communities.

The team, led by Dr. Hayhoe, reached out to Emily Fischer and Melissa Burt at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, and Tracey Holloway, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who founded the Earth Science Women’s Network. And they reached out to Dr. Russell.

For Dr. Russell, Dr. Hayhoe was the right person to pitch the idea of Science Moms. She was another scientist from a red state who was decidedly, publicly, nonpartisan. But Dr. Russell was still nervous, wondering whether her male colleagues would think she was “playing” on her motherhood, or whether she would be seen as “less serious” by talking about being a mom.

She wasn’t the only scientist who worried about this. “I mean, that’s always an issue, right?” says Dr. Fischer, one of the group’s co-founders.

But as Dr. Fischer says, everyone in that group also knew, intimately, the importance of taking a stand. “I lead a very large mentoring program for women,” she says. “So I understand very well the research on role modeling for women. And so, when I feel this question, this ‘how is this going to be perceived by my colleagues that don’t have children,’ I know I have a larger purpose.”

To Dr. Russell, it was one of the first times she felt she could integrate, rather than separate, these different parts of her identity – the scientist and the mother. And looking at the Zoom screen filled with colleagues in the same situation, she felt a new type of strength. A new resilience. They were like a group of penguins, she says, encouraging each other, nudging each other to the cliff, diving off en masse and hoping they wouldn’t get eaten by the seals.

Since the group started, the scientists have recorded videos about both climate science and their children, which together have been viewed more than 440 million times. They have participated in livestreamed town hall conversations and gone on television to talk about climate change from a parenting perspective. They have brainstormed new ways of breaking down complex climate data to a lay audience, met with groups of nonscientist mothers, and helped with social media and advertising campaigns.

“It’s a testament to the human spirit that the people who know the whole story, how serious it is, they’re the ones who work the hardest,” says Mr. Marshall. “Yes, it’s resilience. But the why behind the whole thing is love.”

And it’s that same love, Dr. Russell says, that she can bring to the university lecture hall, or to the office hours with the line of students wanting to share their dreams, or when sitting down at dinner next to her children eating Paul’s famous vegetable lasagna.

It’s the same love, the same person, the same resilience. And it can change the world, she believes. So yes, she wants big classes, big tents, big movements.

Over the past weeks, the Science Moms founders have written letters to their children, which many have shared publicly.

“To my smoochie babies,” Dr. Russell wrote. “I chose this life to help build a better world for you.

“I hope that when you’re grown, you’ll forgive me for being the ‘tired’ mama. The ‘gone to the field’ mama. The ‘obsessed with the new data’ mama. Because the climate is changing so fast, and will affect your world so much, I’ve had to become your ‘gladiator science’ mama so I can fight every day – for you.”

Rural migrants are denied rights in Chinese cities. Can Xi fix the problem?

China’s household registration system acts as a block on the rights of rural migrants in cities. Moves to relax the rules are framed as a step toward greater shared prosperity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Ever since China began disbanding rural communes in the 1980s, migrants have poured into cities to find work. But as rural transplants don’t qualify for urban residency, they can’t easily access public education and social security.

Previous efforts to change the rules on urban residency have largely fallen flat. Now China is trying again by loosening restrictions on household registration in small and medium-sized cities, in a bid to close the gap between rural and urban citizens and boost economic efficiency. This is in line with Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s goal to build a secure middle class that can power a consumer-led economy.

Rural migrants have long struggled with the dilemma of how to educate their children who don’t automatically qualify for public education in cities. Some send children back home to live with grandparents. Others scrimp and save to pay for private schools. But frustration runs deep for many.

“There is increasing recognition that this system is basically unfair,” said Martin Whyte, a sociologist at Harvard. “You don’t want to run a modern society by having people categorized at birth in a lower status position and denied opportunities that you would allow the rest of the population.”

Rural migrants are denied rights in Chinese cities. Can Xi fix the problem?

Tan Chunmiao left his rural hometown in the mountains in 2011 for a factory job in the booming Pearl River megacity of Guangzhou.

Ten years later, Mr. Tan is still there, now putting in long hours as a chef in a Japanese restaurant to support his wife and two young children. But as a rural migrant – one of more than 280 million who have put their shoulder to the wheel of China’s economy – he’s denied the same rights and social services afforded to city residents, including free education for his kids.

“I just have to depend on myself. It’s like I don’t have a Guangzhou ‘green card,’” he says with a laugh, comparing his second-class status with that of a temporary immigrant in the United States.

Under China’s 1950s household registration, or hukou, system, citizens are categorized at birth as rural or urban, based on where their parents are registered. Communist leader Mao Zedong sought to bind peasants to the soil for collective agriculture. After rural communes were dismantled in the 1980s, migrants flooded into cities and became a vast underclass that businesses could exploit.

But today, the economic and social costs of a segregated system are seen as a roadblock to China’s overarching goal of building an urbanized, advanced, consumer economy that is less reliant on exports. Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s “common prosperity” campaign seeks to expand the middle class and reduce income inequality, which is nearly as high in China as in the United States, by some measures.

Studies show the insecurity of migrant life dampens consumption, reduces economic efficiency, and discourages families from having more children, while those children born to migrants struggle to get ahead, given the disadvantages they face.

“It must be soberly recognized that the problem of unbalanced and inadequate development in China is still prominent, with a large gap between urban and rural regional development and income distribution,” Mr. Xi said in a speech last August to China’s Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission.

Past efforts to loosen residency restrictions in smaller cities are widely seen as producing marginal gains, since few benefits flowed to migrants. In response, Beijing is pushing new, top-down measures to eliminate hukou restrictions in most cities by 2025: Its current development strategy calls for abolishing hukou restrictions in cities of less than 3 million people, and loosening them in cities with populations of 3 million to 5 million people.

“We will accelerate the urbanization of the rural migrant population,” Wu Xiao, director of the rural economic department of the National Development and Reform Commission told a press conference in December.

“Not a lot of rain”

Still, experts question whether such plans will make migrants like Mr. Tan full citizens in China’s most dynamic cities, given the cities’ resistance to reforms that would add to their fiscal burden, such as free schooling for migrant kids and social security checks.

“There is a lot of thunder but really not a lot of rain,” says Kam Wing Chan, a professor of geography at the University of Washington and an expert on China’s hukou system.

He points to the easing of hukou restrictions since 2014 in many small and medium-sized cities that largely lack the jobs and social services to attract rural migrants. “It’s just in name. There is no benefit,” Professor Chan says. “I call it a fake hukou.”

Just like the latest proposals, the previous program excluded big cities like Shanghai and Beijing that have long been magnets for bootstrapping migrants. And the problem keeps growing: China’s 2020 census showed that the proportion of urban residents who don’t have an urban hukou has increased to 18.5%, up from 17.2% in 2012.

“Most agricultural workers … still face an ‘invisible wall,’ that is, they cannot get adequate social security and public services,” said Cai Fang, former vice president of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in a keynote speech last July. “Only by turning them into urban residents can they become middle-income groups in the true sense, otherwise they will be very unstable.”

Indeed, the disenfranchisement of such a large group risks creating not only dislocated lives but also the seeds of political instability in China where polls have shown the hukou system to be unpopular with both urban and rural residents.

“There is increasing recognition that this system is basically unfair,” Martin Whyte, a China expert and professor emeritus of sociology at Harvard, told a recent seminar at Harvard’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies. “You don’t want to run a modern society by having people categorized at birth in a lower status position and denied opportunities that you would allow the rest of the population.”

A disrupted education

The impact is especially harmful for the children of rural migrants. Many are forced to live apart from their parents since most urban public schools won’t enroll those children and many migrant families can’t afford fees at private schools.

One young woman in Guangzhou recalled that as an elementary student she had to switch private schools seven or eight times as her parents were migrant farmers who grew vegetables on other people’s suburban land. “My education was very troublesome,” says Ms. Lu, using a pseudonym to protect her privacy. Her parents couldn’t afford the private middle schools open to migrant children, so they sent her back to her home village to study and live with her grandfather. Later she found work at a soy sauce factory in Guangzhou.

Mr. Tan faces similar problems, worrying about how to educate his two children, who live with his wife in another town.

Millions of “left behind” children with poor educational opportunities are contributing to China’s shortage of human capital – a key determinant of whether a country can join the ranks of advanced economies, says Dr. Whyte. The percentage of China’s labor force with some high school education is lower than that of Mexico, Turkey, Indonesia, and Brazil, he says.

Land as security

For many Chinese rural migrants, the uphill battle to obtain the benefits that come with a city hukou has made them reconsider the value of holding onto land back home as a source of security.

Mr. Fuo – a pseudonym – has worked for more than 20 years at a variety of jobs in Foshan, a satellite city of Guangzhou, supporting his mother on their 1.6-acre farm in his hometown. Unable to find a wife, he lives alone in a rented room 300 meters from the bra factory where he now works six days a week. “Living in the city isn’t easy,” he says, “so if the conditions are not very good, and the income is not high, I can consider going home and taking care of my mother,” he says.

As for Mr. Tan, he has no plans to give up his family’s land – half an acre of rice and beans farmed by his father and a few acres of mountain land where they grow trees.

“Above me there are old people, below me young people,” he says, quoting a Chinese saying about a sandwich generation caring for both parents and children.

Instead, he plans to work for another 15 years until his children are grown and self-supporting, and then retire to his village and hope for gradually better social welfare there. “Then I can go back home and have a different life – maybe be a tourist,” he says, “but now, I can’t.”

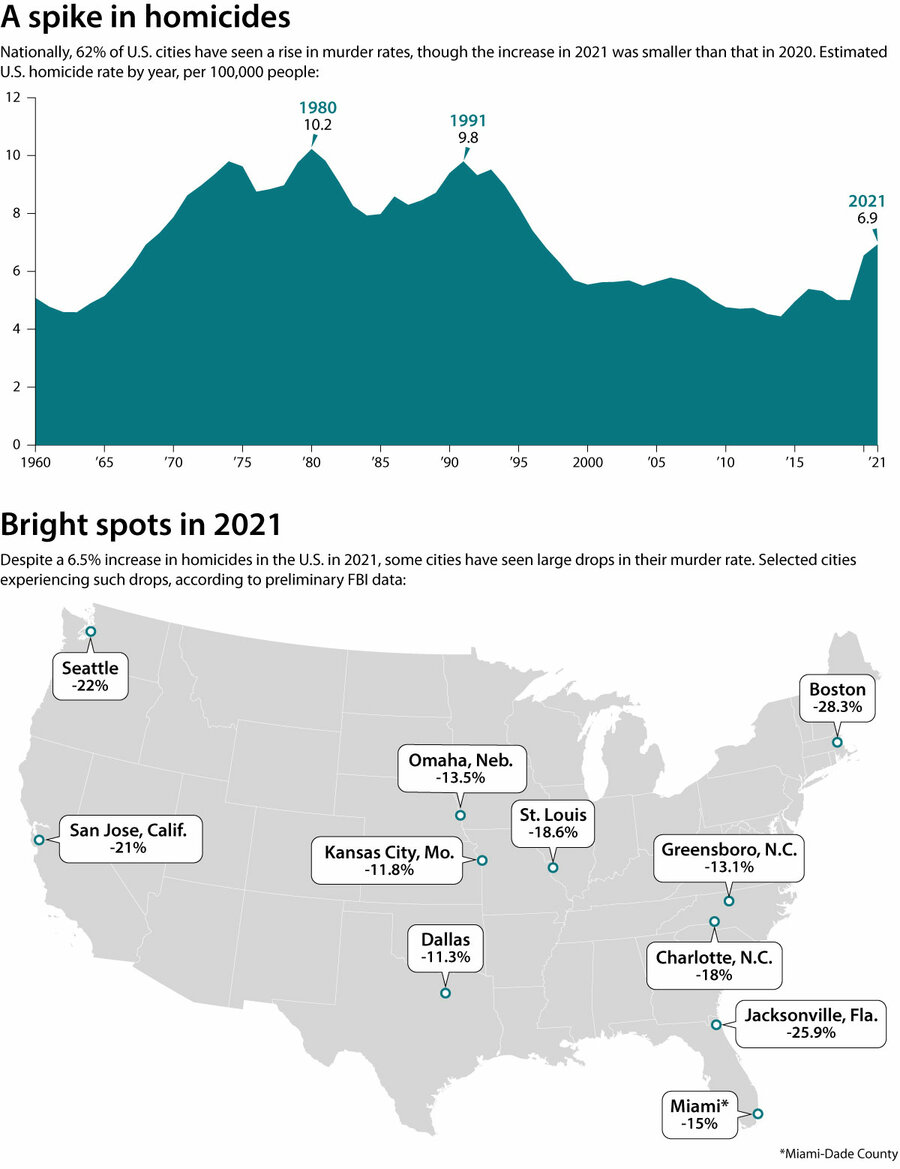

Graphic

Is murder upswing starting to abate? Some US cities see declines.

Declining homicide rates in some U.S. cities hint at hope amid concern about a jump in violent crime. The reasons may range from improved policing to an easing of pandemic stresses on society.

Despite a second straight year of rising homicides in 2021, last year’s violent crime data show some reasons for hope.

First, even though the homicide rate rose again, it slowed down. During the first three quarters of 2020, there was a 30% year-on increase in the homicide rate, according to research from the Council on Criminal Justice. In the same period last year, it rose only 4%.

Second, that rise hasn’t been uniform. Homicides rose in almost every major city in 2020 – as gun deaths hit an all-time high – but that wasn’t true in 2021. Some cities – like Portland, Oregon; and Albuquerque, New Mexico – still had major increases. But others, like Boston and Dallas, had major dips.

That’s reason for optimism, says Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri, St. Louis. Nationally, he says, it suggests that the trends driving up violent crime – like the COVID-19 pandemic and social unrest – have started to wane.

“What, generally speaking, we’re seeing in most but perhaps not all places is an unraveling of some of the conditions that gave rise to the increase in ’20,” says Professor Rosenfeld.

Beyond that, numbers that vary city by city tend to have city-by-city explanations. Improved policing seems to be the answer in some cities, and community-based interventions may also be playing a role, though their effect is less certain.

Despite the overall rise since 2019, America’s homicide rate is still far below the violent crime peaks of the 1990s. A more nuanced national picture in 2021, says Professor Rosenfeld, may suggest future increases aren’t inevitable.

“I think it is good news,” he says.

– By Noah Robertson, staff writer

AH Datalytics, FBI

Essay

In the Cold War’s depths, a glimmer of light

At a time when the world seemed on the brink of nuclear war, our essayist, a diplomat, found hope in an unlikely place.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Peter Bridges Correspondent

I arrived at the United States Embassy in Moscow in 1962, weeks before the Cuban missile crisis. I was a political officer, tasked with reporting on the secretive Soviet scene.

Tensions were high, but a U.S.-USSR cultural exchange led to an invitation to a party at Moscow State University. The room at MGU was surely bugged, but it was so noisy that hidden microphones were useless. Two men, students at the Faculty of Law, approached me.

Where, I asked, will you work?

We will join the Prokuratura, they said.

I said I was sorry to hear that. The prosecutor-general’s office had played a key role in Stalin’s purges. Its then-leader had commanded a notorious prison camp.

The men said they would make the Prokuratura better, more humane.

I was skeptical. That’s dangerous, I said. No, they replied, we will work carefully and slowly – and there are others like us. I wished them well.

I do not know what happened to those men. I learned years later that they’d had a predecessor in the Faculty of Law: Mikhail Gorbachev, who changed Russia so profoundly. I could not have predicted a Gorbachev, but I never forgot those students. They gave me hope.

In the Cold War’s depths, a glimmer of light

In 1963 my wife and I and our three small children – the oldest was 6 – completed our first year at the American Embassy in Moscow. I was a career diplomat, a political officer tasked with observing and reporting on what I could learn of the secretive Soviet scene.

It was the middle of the Cold War, the nuclear standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union. Eastern Europe had been subjected to the USSR, and the West had formed NATO in response. Tensions were high. Weeks after our arrival the previous year, Soviet attempts to base nuclear-capable missiles in Cuba had brought the world too close to nuclear war.

There were signs of hope, too, including cultural exchanges with the West. Among them, a half-dozen American graduate students, several with spouses, were spending an academic year at MGU, Moscow State University.

Our public affairs officer gave a party for the students. My wife, Mary Jane, asked one of the couples how they found life in MGU’s skyscraper building. Not too bad, they said. The main problem was the scarcity of laundry facilities. Ah, said my wife, you are welcome to use our washer and dryer.

When they returned later, bearing dirty clothes, they often stayed for lunch or dinner.

Soon the couple, Philip and Nancy Stewart from Ohio State University, reciprocated by inviting us to a get-together at the university. No doubt the KGB, the chief Soviet state security apparatus, would not have wanted anyone from the U.S. Embassy to attend, but we got in.

The party took place in a university meeting room. It was packed. There was lots to eat and drink, and the noise level rose high. No doubt there were microphones hidden in the walls, but so much noise made them useless to anyone trying to listen in.

Two young men approached me. From my dress, it was clear I was the foreign diplomat they had heard was coming. They introduced themselves as students in the Faculty of Law.

What, I asked them, are your plans for a profession?

We are going to join the Prokuratura, they said.

I said I was sorry to hear that. I knew about the Prokuratura, a powerful arm of the Soviet police state. It combined what in the U.S. were functions of the attorney general, congressional committees, grand juries, and public prosecutors. Andrei Vyshinsky, procurator general in the 1930s, had overseen Stalin’s horrendous purges of millions of ordinary citizens – plus most of the members of the Communist Party Central Committee and top Soviet generals. Now, in 1963, the procurator general was Roman Rudenko, who (I learned years later) had commanded a camp in which 12,000 people died of starvation and disease.

One of the young Russians said that they were going to change things. His comrade said they aimed to make the Prokuratura better, more humane.

I was very skeptical. You and your families will suffer if you get out of line, I said. No, they replied, we will work carefully and slowly – and there are others who think as we do.

We ended our conversation quickly. It was unwise for them to be seen talking with a Western diplomat. I wished them well.

Until then, I’d been pessimistic about the prospects for change in the USSR. Liberals and even rebels did exist there. I knew a young rebel, in fact: Andrei Amalrik, who was later sent to Siberia.

My two law students had made clear they were not rebels; they wanted change without violence. I went back to the embassy pondering that encounter.

I do not know what happened to them. I learned years later that they’d had a predecessor in the Faculty of Law named Mikhail Gorbachev, who changed things mightily. It was he who, as head of both the Soviet government and the Communist Party in the 1980s, pushed for glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring). His policies undermined the Soviet Union, which came apart in 1991. I could never have imagined a Gorbachev, but I never forgot the two students. They gave me hope for the Russians, a strong, talented, and long-oppressed people.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

How aid can nudge the Taliban

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Five months after the Taliban took over Afghanistan, the country has become the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. About half of its 40 million people are hungry, with dire forecasts for the winter. In response, both the United States and United Nations announced major relief efforts on Tuesday. The U.S. will give $308 million in new humanitarian aid while the U.N. made a global appeal for $4.4 billion in assistance.

Yet the big news may be this: After taking stock of the Taliban’s harsh style of rule, both the U.S. and U.N. vowed to bypass the new government and work directly with independent humanitarian groups. The aid will be distributed based on listening to the priorities of local Afghans.

This bottom-up, pro-women approach may help prevent the U.S. and U.N. from working directly with a morally suspect regime and prevent aid money from being diverted to the Taliban’s purposes. It could also allow Afghans to follow local norms of self-governance, challenging the Taliban’s top-down authoritarian rule.

How aid can nudge the Taliban

Five months after the Taliban took over Afghanistan, the country has become the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. About half of its 40 million people are hungry, with dire forecasts for the winter. In response, both the United States and United Nations announced major relief efforts on Tuesday. The U.S. will give $308 million in new humanitarian aid while the U.N. made a global appeal for $4.4 billion in assistance.

Yet the big news may be this: After taking stock of the Taliban’s harsh style of rule, both the U.S. and U.N. vowed to bypass the new government and work directly with independent humanitarian groups.

The aid will be distributed based on listening to the priorities of local Afghans. It is designed to build up individual resiliency and encourage consensus around shared values. And it will be inclusive of all Afghans regardless of ethnicity or gender.

This bottom-up, pro-women approach may help prevent the U.S. and U.N. from working directly with a morally suspect regime and prevent aid money from being diverted to the Taliban’s purposes. It could also allow Afghans to follow local norms of self-governance, challenging the Taliban’s top-down authoritarian rule.

“We would do well to figure out what it is that’s going to be helpful for the Afghan people, and then work backwards to negotiate with the Taliban on that basis,” Azza Karam, a professor of religion and development at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, told Foreign Policy magazine.

This listen-first approach is not new in international aid. The Biden administration, for example, promises to provide 25% of U.S. aid to local organizations, especially in Central America, up from 6%. Yet in Afghanistan, the listen-and-learn approach is a necessity.

“Just because we’re the United States does not mean we’re going to solve the problem with more people and more money,” says Robert Jenkins, a top USAID official. “We need to engage locals. ... We need to listen to them.”

Applying this approach in Afghanistan could be a model for other trouble spots. “By the end of this decade, 85% of the extreme poor – some 342 million people – are going to be living in fragile and conflict-affected states,” says USAID Administrator Samantha Power. “So we have to shift our focus, not just in terms of where we work but with whom we partner.”

American aid, she adds, must be “rooted in the societies in which we work.” In Afghanistan, the aid could help restore hope of self-governance. It could keep democratic values alive during Taliban rule.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding resilience through God’s grace

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mimi Oka

When difficulties emerge, we can rely on God’s gracious love, which imbues us with strength, hope, wisdom, and healing.

Finding resilience through God’s grace

Resilience is a concept we’re hearing more about these days – whether in relation to the pandemic, to weather events, or to other adverse situations. The Christian Science Monitor, for example, has a series titled “Finding Resilience: Adapting in the face of adversity.”

Accounts of resilience can be encouraging as we learn of people who have gone through great hardship and emerged stronger for it. But what if these stories make us feel that it’s all well and good for others to experience great progress or renewal, but that it’s just not possible for us?

Actually, instances of genuine resilience are evidence of a quality that is innate to all of us as children of God, the divine Mind that is Love itself. Resilience is enabled by the grace that flows abundantly from God. This is true resilience, grounded in the spiritual fact that God is our divine Parent, who has bestowed grace and favor upon each of us.

Divine grace enables people to triumph over their greatest fears. This is illustrated in the scriptural story of Jacob.

Years after fleeing for his life because his brother, Esau, felt cheated out of their father’s blessing, Jacob is struggling mightily the night before coming face to face with Esau once again. It is the grace of God that shows Jacob that his true identity is spiritual and that he is the “apple of [God’s] eye” (Deuteronomy 32:9, 10). When the brothers meet, Jacob sees Esau as the very expression of God, too.

This recognition brings the thinking and actions of both brothers in line with the true sense of man as God’s creation. One of the most beautiful depictions of grace in human relations follows, in which the brothers extend to each other love and forgiveness. Jacob urges Esau to accept a substantial gift “because God hath dealt graciously with me, and because I have enough” (Genesis 33:11).

God is abundantly and continuously pouring forth the grace of impartial love on all of us as His beloved children. When we recognize that this grace is at hand even in difficult situations, this reveals to us strength we didn’t know was there, divinely impelled strength that enables us to keep going.

As we open up to that, we feel its effects in our lives. We feel the divine influence, Christ, propelling us forward, bringing forth strength, clarity, hope, trust, ingenuity, and love. It’s this grace of God that enables our lives, homes, relationships, communities – whatever we need – to be restored or rebuilt.

I knew someone who found such resilience after experiencing terrible abuse as a child at the hands of one who should have been her protector. She grew up and developed a strong work ethic and a fierce desire to fight for and protect the innocent. What really touched me was that she was able to forgive and sincerely love the person who had abused her (and who has since passed on).

She attributes this to meeting someone whose faith in God and God’s goodness was “contagious,” as she described it. This helped her gain a sense of man’s innate holiness and integrity. She was able to see through those years of pain and suffering and refuse to be deprived of her natural joy and her love of the good in humanity. People who know her today comment on her warmth and, above all, compassion.

The foremost example of grace expressed is Christ Jesus, who the Bible says was “full of grace and truth” (John 1:14). Mary Baker Eddy, in the Glossary of “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” defines Jesus in part as “the highest human corporeal concept of the divine idea” (p. 589). He continually brought about manifestations of resilience – stilling storms, feeding multitudes with just a few loaves and fish, healing diseases deemed incurable.

All of this was evidenced because he so fully expressed the Christ, “the true idea voicing good, the divine message from God to men speaking to the human consciousness” (Science and Health, p. 332). And Christ, Truth, naturally comes to each of us with tender grace and shows us that we can experience and witness profound healing as we follow Jesus’ example.

So when we see instances of resilience in the media and experience it in our lives, let us see this as tangible evidence of God’s grace in action. We each have the grace to go forward through our divine Father-Mother’s love for us.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Dec. 27, 2021, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

An unexpected visitor

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow. Our Fred Weir has put a lot of effort into exploring the moods, views, and preferences of young Russians who’ve grown up knowing only Vladimir Putin as leader. From Moscow, Fred reports on what’s so different about the “Putin Generation.”