- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Like son, like father: How a family business is built with kindness

You probably won’t find the secret sauce of T and Sons Property Management LLC in a Harvard Business School textbook.

But maybe it should be.

The cornerstone of this small business in Mechanicville, New York, is kindness.

About five years ago, young Thor Hendrickson Jr. started helping out a neighbor, whom he spotted raking her yard with a cast on her arm. He volunteered to help. That single act turned into cutting the lawn, moving furniture, and shoveling snow for her. No charge.

Lending a hand to other neighbors soon led to paid landscaping and snow removal jobs for Thor. “I’m not a sit inside kind of person. I like to go out and help people with their yards and stuff,” the 16-year-old told WRGB-TV in Albany. “And if they don’t want to pay me, it’s OK.”

In the past year, Thor persuaded his dad to buy a snow plow for his pickup truck, so they could help more people, together. Word spread. Their new father-and-son snow removal and landscaping business keeps growing.

“I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing with my son if it wasn’t for his inspiration,” Thor Hendrickson Sr. told Fox News. Growing up, his son was labeled as having a learning disability, Mr. Hendrickson told “Morning in America,” but that never stopped him.

It sure looks like the son is teaching the father how the currency of kindness can fuel success.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

What happens to US education if there’s no one to teach?

Pandemic-induced staff shortages in schools are laying bare chronic problems in American education. Our reporters look at some of the more creative short- and long-term responses.

-

Sarah Matusek Staff writer

At a time of slipping test scores and plummeting social-emotional skills after prolonged remote schooling, staff shortages at schools, while anecdotal, are causing consternation both in city halls and at kitchen tables. Schools are a vital tool for America and its children to really recover from the pandemic. And more Americans are questioning whether public education is up to the task.

Amid the stress, community members are stepping in to cover classrooms, and politicians and educators are exploring immediate stopgaps to help maintain in-person learning and attract more talent long-term. The governor of New Mexico called up the National Guard to serve as substitutes and is volunteering as a substitute teacher. She, along with the governors of at least five other states, is calling for raising teacher salaries.

During the current school year, Kristin Humphries, superintendent of East Moline School District 37 in Illinois, has already helped in a number of positions including paraprofessional, playground monitor, principal, and bus dispatcher.

“This is my 28th year in education. … I’ve never been more tired,” Dr. Humphries says. Still, “I’ve never seen more people just jump to it and do whatever it takes. Everybody’s tired, but they know this is an important mission.”

What happens to US education if there’s no one to teach?

Is “blar” a word? Karina Sandoval wonders aloud, chuckling as she marks up first grade papers at her Granby Elementary School desk.

It’s a mid-January afternoon at the rural Colorado school bordered by snowbanks, and it’s time to collect students from music class. Mrs. Sandoval settles them for snack time.

As natural as she is, she is not a first grade teacher. She’s a local parent who became certified to serve as a substitute this school year.

“It was an opportunity to help,” says Mrs. Sandoval, who has a kindergartner in the East Grand School District, where some 1,350 students are adjusting to more staff shortages than usual. Mrs. Sandoval’s gained not only ideas for coaching her own child academically, she says, but also new respect for teachers. “We don’t realize, on the outside, how much work they do in here.”

The United States was already dealing with some teacher shortages before March 2020, with warnings about a looming crisis stretching back more than a decade. Short-term outages by educators to recover from COVID-19 and aid family members have exacerbated vacancies, which include support staff. As the pandemic spills into a third school year, governors have had to call up the National Guard to do everything from drive buses (Massachusetts) to teach class (New Mexico).

Coming at a time of slipping test scores and plummeting social-emotional skills after prolonged remote schooling, the shortages, while anecdotal, are causing consternation both in city halls and at kitchen tables. Schools are a vital tool for America and its children to really recover from the pandemic. And more Americans are questioning whether public education is up to the task. Some 54% of Americans say they are dissatisfied with the quality of U.S. K-12 schools, while only 46% approve, according to Gallup. That dissatisfaction is up 7 percentage points from 2019, before the pandemic.

Amid the stress, community members are stepping in to help, and politicians and school leaders are exploring immediate stopgaps to help maintain in-person learning, as well as initiatives to attract more sustainable talent long-term.

- The governors of Oklahoma and North Carolina issued executive orders allowing state employees to serve as substitute teachers in public schools without losing their regular jobs or pay.

- The governor of New Mexico called up the National Guard to serve as substitutes, and is volunteering as a substitute teacher herself.

- Governors in at least six states (Alabama, Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Mississippi, New Mexico) are calling for raising teacher salaries.

A lot is at stake for the U.S. – and for state and local elected officials, if they can’t deliver. Economic recovery from the pandemic requires that parents are able to get back to uninterrupted workweeks, guaranteeing consistent paychecks and open businesses. Schools also need time to prepare the students who down the road will help fuel America’s growth, but who right now are struggling with math.

“There is absolutely a hunger for using this moment to enact broader policy change, and at the same time there is just a struggle with the capacity to do so,” says Desiree Carver-Thomas, policy analyst at the Learning Policy Institute in Palo Alto, California. “It’s a balancing act between trying to keep schools afloat and trying to think about the big picture and long-term picture.”

“I’ve never been more tired”

Behind current pandemic-related staffing problems lurk longtime challenges with recruiting and retaining teachers, says Lynn Olson, a senior fellow at the FutureEd think tank at Georgetown University, and co-author of an October 2021 report on teacher shortages.

Underlying problems include turnover and declining enrollment in teacher preparation programs. Among many of the country’s more than 13,000 districts, there exists a surplus of elementary or social studies teachers, but there aren’t enough teachers of color; teachers who specialize in science, math, foreign language, or special education; and those willing to work in rural or urban locations, according to the report.

Districts and states are tapping into their shares of about $190 billion in federal COVID-19 relief for K-12 education to try to fix some of the short- and long-term challenges. In addition to the handful of states looking to raise salaries, Los Angeles Unified School District offered a 5% pay boost this school year. Some states, like Tennessee and Minnesota, are investing federal funding in expanded Grow Your Own teacher initiatives, programs that recruit and financially support potential teachers from local communities.

Some research suggests that teacher retention rates rose in at least a half-dozen states earlier in the pandemic, says Chad Aldeman, policy director at Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University. So far data doesn’t point to a “mass exodus of people that are causing the vacancies,” he adds. Districts may be trying to rebound after fewer hires last year, for instance, and have more funds to put toward hiring due to government aid.

Cherry Hill Public Schools in southern New Jersey has “actually turned over fewer staff in the last two years than we typically do,” in terms of certified staff like teachers, says Superintendent Joseph Meloche. Currently, however, educational assistant and facilities jobs represent the most vacancies.

Even so, teachers are reporting higher levels of stress and more are considering leaving the profession than in pre-pandemic years, according to surveys. In Michigan, 44% more teachers retired midyear in the 2020-2021 school year than in the year prior, according to local reporting.

Nearly all – about 96% – of U.S. schools were operating in person as of Jan. 23. However, there is continued debate across the country about that approach, with teachers unions and some students pushing for stronger safety precautions and cautioning about prolonged effects from the pandemic and staff shortages.

Though “safe, in-person learning is what’s best for kids,” says Kisha Borden, president of the San Diego Education Association, there are trade-offs. A lack of substitutes has cut into teachers’ professional development time and ability to take days off. Plus, the merging of some classes into spaces like auditoriums has spurred more than health concerns, she adds: “When you put several classes together, the learning suffers.”

Substantial vacancies in schools nationwide in positions such as bus driver, cafeteria worker, and substitute teacher are well documented, leading to more teachers having to cover for other tasks.

“Low-income and minoritized students are more likely to be taught, in general, by less qualified teachers. They also experience more teacher absences than higher-income peers,” and have less access to substitute teachers, says Christopher Redding, an assistant professor of educational leadership at the University of Florida. “All of which can play a role in reducing the stable learning environment.”

Kristin Humphries, superintendent of East Moline School District 37 in Illinois, along with colleagues, recently served middle schoolers pizza for lunch. Stepping in has become a theme this year for Dr. Humphries, who’s helped in a number of positions including paraprofessional, playground monitor, principal, and bus dispatcher.

“This is my 28th year in education. ... I’ve never been more tired,” he says. Still, “I’ve never seen more people just jump to it and do whatever it takes. Everybody’s tired, but they know this is an important mission.”

“What can we do together?”

Mrs. Sandoval in Colorado considered substitute teaching after hearing about widespread school staffing needs on the news. She’s conflicted about whether it’s safe to work around so many people, since her family battled COVID-19 in 2020, but plans to continue subbing for now. “I enjoy being with the kids,” she says.

Another mother, Nicole Rukstalis in Milton, Massachusetts, contacted her school district in early January to see how she could substitute-teach. The college professor supported moving school online at the pandemic’s start, but the availability of vaccines and reports on learning loss and student well-being changed her mind.

On social media she encouraged other parents with flexible work schedules to substitute. “My goal wasn’t to say, ‘I’m awesome,’ but ‘What can we do together?’ Ten people might make a difference,” she says.

Elsewhere, one district is reaping benefits from experimenting with new ways to recruit teachers. Clarksville-Montgomery County School System (CMCSS), a district of about 38,000 students in northwest Tennessee, started a teacher residency program in 2018, which was recently named the country’s first registered teacher apprenticeship program by the U.S. Department of Labor. Residents can earn a bachelor’s or master’s degree and their teacher license for free, while working alongside a teacher and committing to work for the district.

Traci Koon, CMCSS educator pipeline facilitator, says the program has been “instrumental” in helping keep operations going this year, with teacher residents covering classes and helping with lesson plans. The district expects to place about 75 to 80 teachers annually through the program and recruited more diverse candidates in its first cohorts, better reflecting the student body.

Back in Colorado, East Grand School District Superintendent Frank Reeves says being more intentional about soliciting community member assistance is one strategy that might stick moving forward.

“What we’re really finding out is there’s so many really positive, awesome people that can work with our kids,” he says.

Patterns

Europe, divided on Russia, hesitant to back Biden

Why isn’t Europe joining the U.S. in a united front in the Ukraine crisis? It’s complicated. But our London columnist notes the transatlantic alliance has had trust issues for years. And some European states are ready to revisit their relationship with Russia.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

For Vladimir Putin, the timing of the Ukraine crisis could hardly be better; for Joe Biden, hardly worse.

Because a resolution of the crisis will depend not just on Moscow and Washington, but on dozens of European countries that lie between them. And America’s European allies are less ready to mount a unified response – or to make common cause with Washington – than at any time in recent years.

Their actions in the coming days could prove critical to Washington’s hope of finding a diplomatic way out.

And in the longer run, they will help define Europe’s future strategy toward both of the major powers now locking horns over Ukraine: the United States and Russia.

President Putin’s military buildup on the Ukrainian border, along with his drive to restore Russia’s Soviet-era sphere of influence, has highlighted an awkward obstacle to any common approach in Europe: disagreement, in light of Western Europe’s economic ties with Russia, over how to balance such practical considerations with the continent’s core commitment to democratic values.

European leaders will need to make much more progress toward an answer to that question if they are to offer President Biden the solid support he is seeking.

Europe, divided on Russia, hesitant to back Biden

For Vladimir Putin, the timing of the Ukraine crisis could hardly be better; for Joe Biden, hardly worse.

Because a resolution of the crisis will depend not just on Moscow and Washington, but on dozens of European countries that lie between them. And America’s European allies are less ready to mount a unified response – or to make common cause with Washington – than at any time in recent years.

Their actions in the coming days could prove critical to Washington’s hope of finding a diplomatic way out.

And in the longer run, they will help define Europe’s future strategy toward both of the major powers now locking horns over Ukraine: the United States and Russia.

The Europeans are in the throes of what might be called a geopolitical identity crisis. Deeply unsettled by the go-it-alone presidency of Donald Trump, they have been asking themselves how much they can rely on the transatlantic alliance, especially now that Washington’s top foreign-policy priority is China.

Europe is also debating its attitude to Russia, given that the continent is much more closely linked economically with Moscow – and hugely more energy-dependent on the Russians – than the United States.

That debate has highlighted different views on how to deal with Mr. Putin: The former Soviet states near Russia have far fewer doubts on the need for a robust deterrent to his growing regional ambitions than do capitals farther west.

At the same time, the crisis also finds key European leaders preoccupied with politics closer to home.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson is neck-deep in controversy over a series of Downing Street parties held at a time when the rest of the country was in lockdown. French President Emmanuel Macron faces a stern reelection test in April.

In Germany, the three-party coalition that has taken over from long-serving Chancellor Angela Merkel appears divided over how tough a line to take with Russia.

For Mr. Biden, the stakes could hardly be higher. A key element of his plan to deter Mr. Putin from invading Ukraine is to demonstrate shoulder-to-shoulder resolve across the Western alliance that the Russian president would pay an immediate and painful political and economic cost if he moved further against Ukraine.

After an 80-minute video call on Monday he declared “total unanimity with all the European leaders.”

But while that’s almost certainly true should Mr. Putin launch a full-scale invasion, it’s still not clear whether the allies would respond unanimously to lesser forms of aggression such as cyberattacks, cross-border artillery fire, missile or drone strikes, or a raid aimed at seizing further territory in eastern Ukraine and destabilizing the pro-Western government in Kyiv.

That’s what Mr. Biden referred to at a news conference last week as a “minor incursion.” In that case, he said, “we end up having a fight [with the European allies] about what to do and not do.”

That remark was undeniably a diplomatic gaffe: Ukrainian leaders accused the president of effectively giving a greenlight to Mr. Putin for such a “minor incursion.”

But it was also true. And even though, as the crisis ramps up, a number of European NATO states are sending weapons to Ukraine and beefing up their military presence in Eastern Europe, that diplomatic calculus has probably not changed.

Would Germany, for instance, be ready to mothball the new pipeline designed to carry more Russian natural gas to Europe, bypassing an existing route through Ukraine? The coalition government’s foreign minister, Annalena Baerbock, has long favored scrapping it, but there has been no sign Chancellor Olaf Scholz would contemplate that.

Germany and France also this week reopened a diplomatic track of their own. They scheduled a meeting with Russian officials within the framework of the still-unimplemented cease-fire plan they negotiated with Moscow following a Russian-supported uprising in Eastern Ukraine eight years ago.

For France, there’s a powerful, long-term logic to such separate initiatives: a desire to develop a more autonomous European role on the world stage.

That would not mean jettisoning close ties with Washington, nor unwinding the NATO security alliance. But it would recognize that Europe – collectively, the world’s third-largest economic power after the U.S. and China – has interests of its own to defend.

If President Macron is reelected in April, there is little doubt that he would continue to press for more European “strategic autonomy.”

But Mr. Putin’s military buildup, along with his drive to restore Russia’s Soviet-era sphere of influence, has highlighted an awkward obstacle to any common approach in Europe: disagreement, in light of Western Europe’s economic ties with Russia, over how to balance such practical considerations with the continent’s core commitment to democratic values.

European leaders will need to make much more progress toward an answer to that question if they are to offer President Biden the solid support he is seeking.

Sacred spaces: Church buildings repurposed as community hubs

One of the roles of a house of worship is to foster community. We look at three American cities where church edifices are being converted into new centers of community.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Erika Page Staff writer

As religious congregations dwindle, developers have jumped at the chance to transform church buildings into luxury condos, cafes, even a Dollar Tree.

But in some cities, residents are breathing new life into sacred spaces by giving fresh thought to what it means to serve, and who can constitute a congregation.

After closing last summer, St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Hallowell, Maine, offered the building to Capital Area New Mainers Project, which supports the growing number of refugees and other immigrants in the area.

The congregation chose CANMP because it “felt like we would be carrying on the mission,” says Chris Myers Asch, CANMP’s co-founder and executive director. “We take that responsibility very seriously. It’s hallowed ground.”

Mr. Myers Asch and his team of volunteers are currently renovating the sanctuary to create the Hallowell Multicultural Center. When it’s ready, anyone in the community will be able to host events that bring people of different backgrounds together.

“It’s a place,” he says, “where we can celebrate becoming America together, bringing the newest Americans into the fold.”

Sacred spaces: Church buildings repurposed as community hubs

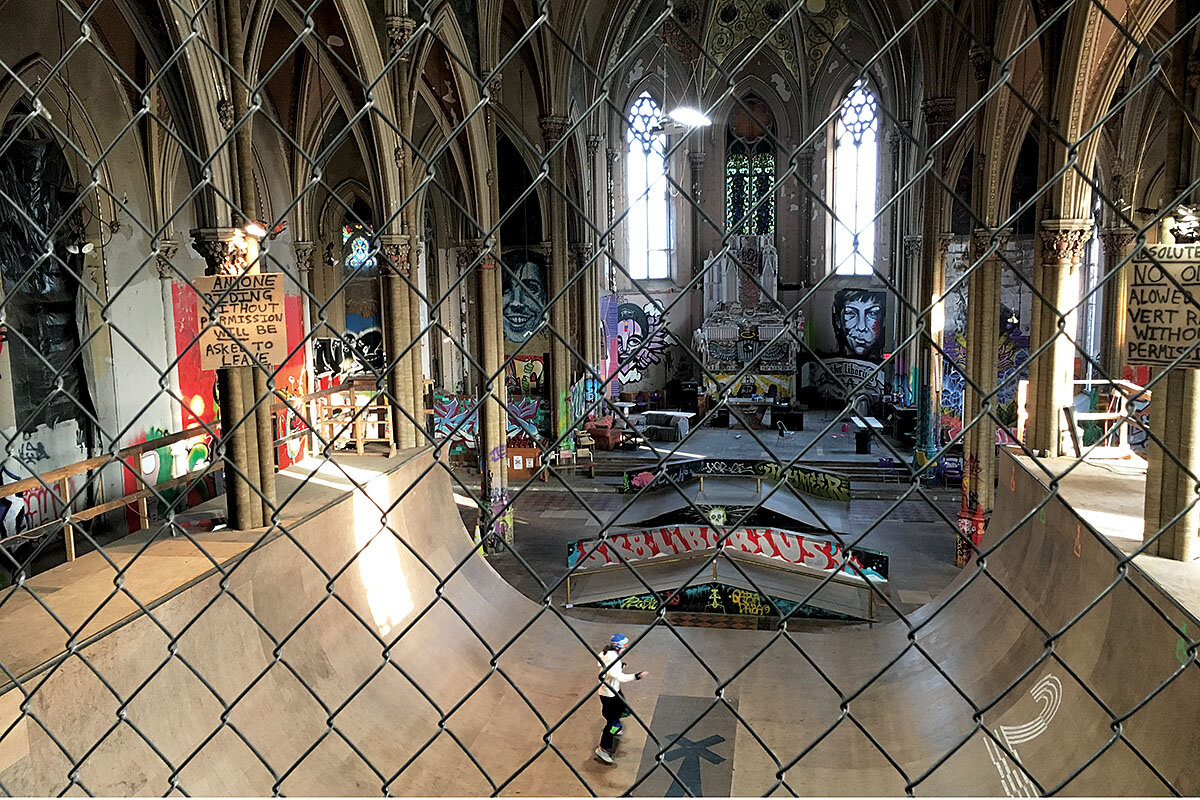

Victoria Stadnik glides on roller skates down one side of a wooden halfpipe decorated in neon spray paint. Light pours in through stained-glass windows, catching her body as she rotates through the air in the nave of what used to be St. Liborius Catholic Church.

After the church shut down in 1992, the building served briefly as a homeless shelter. Now, St. Liborius is better known as Sk8 Liborius – a skate park in use informally for a decade, with plans to open officially in three years.

St. Liborius is one of hundreds of churches across the United States beginning a second life. As congregations dwindle – only 47% of American adults reported membership in a religious organization in 2020, down from 70% in 1999 according to a Gallup poll – churches are closing doors and changing hands. Developers have jumped at the chance to transform the consecrated spaces into luxury condos, cafes, mansions – even a Dollar Tree.

For some, the trend brings with it a sense of dismay.

“Congregations are the major community hubs,” says Ram Cnaan, director of the Program for Religion and Social Policy Research at the University of Pennsylvania. “And I’m talking as a person who is not spiritual, who does not believe in any God, just as a social scientist. Those congregations are the fabric of our society.”

But in some cities, residents are breathing new life into sacred spaces by giving fresh thought to what it means to serve, and who can constitute a congregation. Groups in St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Hallowell, Maine, are finding that one fundamental purpose of church – community uplift – can take many forms.

“These places are very powerful links to the history and the evolution of our neighborhoods,” says Bob Jaeger, president of Partners for Sacred Places, based in Philadelphia. Even though a church “may need repair, even though it may be empty, ... it’s a bundle of assets. It’s a bundle of opportunities.”

For Ms. Stadnik, the skate church offers more than an adrenaline rush.

“It’s hard to make friends as an adult,” says Ms. Stadnik, who moved to St. Louis with few connections, as she catches her breath from her halfpipe run. But at Sk8 Liborius, “it feels like I unlocked the secret.”

Falling, then getting up

When Dave Blum, co-owner of Sk8 Liborius, speaks about his plans for the church, his voice echoes out across the sanctuary, ringing with the hope and certainty of a sermon. His team is creating not only a skate park but also an urban art studio where local artists can display and sell their work and children can learn skills ranging from metalworking to photography.

In every empty nook and cranny, he sees the potential to support a new congregation: underserved urban youth. He hopes skateboarding will get kids in the door – where vital lessons await.

Skating is about learning how to get up when you fall, both physically and mentally, says Joss Hay, another co-owner. If your friends fall, “You don’t tell them to give up. You’re always lifting them up.”

The church was completed in 1889, and after years of neglect, it has a long way to go before it can pass an inspection and be formally opened to the public. Emergency exits, bathrooms, window repair, plumbing, electricity, and heat are just a few of the items on a to-do list of fixes estimated at $1 million. But donations are pouring in from supporters, and local skaters like Ms. Stadnik, who also works as a skating coach, spend weekends helping with repair work.

“A whole community came together to build these structures because it was important to them. And now, what we’re trying to do is have a whole community come together to maintain this structure,” says Mr. Blum.

“Becoming America together”

Welcoming newcomers into the fold is another function churches often fulfill. In Maine, a local nonprofit is continuing that mission by turning a former holy space into a home and community center.

Ali Al Braihi and Mohammed Abdalnabi came to the U.S. as refugees because war – in Iraq for the first and Syria for the second – made staying home impossible. Their journeys were different, but their families both ended up in Hallowell, Maine. Housing was limited, says Mr. Abdalnabi, and squeezing all nine members of his family into a two-bedroom apartment was “rough.” Mr. Al Braihi had the same difficulty.

Now, the 18 people that make up both families live in what used to be St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church, a classic white, wooden structure in Hallowell’s small downtown.

“What I feel is fortunate and thankful,” says Mr. Al Braihi, now a college student. His family is Muslim, but he says he appreciates the sacredness of his new home and is just happy to finally have enough space to study.

After closing last summer, St. Matthew’s offered the building to Capital Area New Mainers Project (CANMP), which supports the growing number of refugees and other immigrants in the area.

The congregation chose CANMP because it “felt like we would be carrying on the mission,” says Chris Myers Asch, CANMP’s co-founder and executive director. “We take that responsibility very seriously. It’s hallowed ground.”

Mr. Myers Asch and his team of volunteers are currently renovating the sanctuary to create the Hallowell Multicultural Center. When it’s ready, anyone in the community will be able to host events: dinners, talks, movie screenings, weddings – whatever brings people of different backgrounds together.

“We see it as a wonderful space to bring cultures together, to learn from each other, to share stories with each other, to share food, break bread, and really build community,” says Mr. Myers Asch. It’s a place, he says, “where we can celebrate becoming America together, bringing the newest Americans into the fold.”

“A labor of love”

Further down the East Coast, in a church turned recreation center, there’s a different type of culture unifying the community – sports.

When Coach Curt De Veaux discovered that Our Lady of Hope, a Catholic church in a low-income neighborhood of Philadelphia, had sat vacant for 15 years, his wheels started turning.

After nine years as a basketball coach, he understood the power of sports to transform individuals. So he partnered with a local organization to purchase the space and began renovations to turn the church into a youth recreation center.

“A lot of kids in the area don’t have an outlet, or things to do,” he says.

City Athletics Philadelphia now offers basketball, volleyball, indoor soccer, lacrosse, spinning bikes, and other types of training at low to no cost to neighborhood youth.

“There are just so many life lessons that you can help a young person navigate,” says Mr. De Veaux. “I always tell the parents, ‘It looks like sports, but it’s really life,’ whether it’s emotional control or learning how to work with others, how to respect rules, how to compete, or practice makes perfect.”

At the end of the day, Mr. De Veaux’s goal is for the church to continue to be a gift to the neighborhood. Beyond his work at the youth center, he has also organized drives for coats, school uniforms, and sports-related toys.

“Every time I go there, I come in with a list of things I need to get done, and I come out and my list is always longer than when I went in,” adds Mr. De Veaux, who says it’s taken plenty of resources, energy, and anguish to stop roof leaks, wrangle the heating system, and bring the church up to standards.

“But it really is a labor of love.”

Points of Progress

Shut the door, and stay out of the way: Strategies to help wild animals

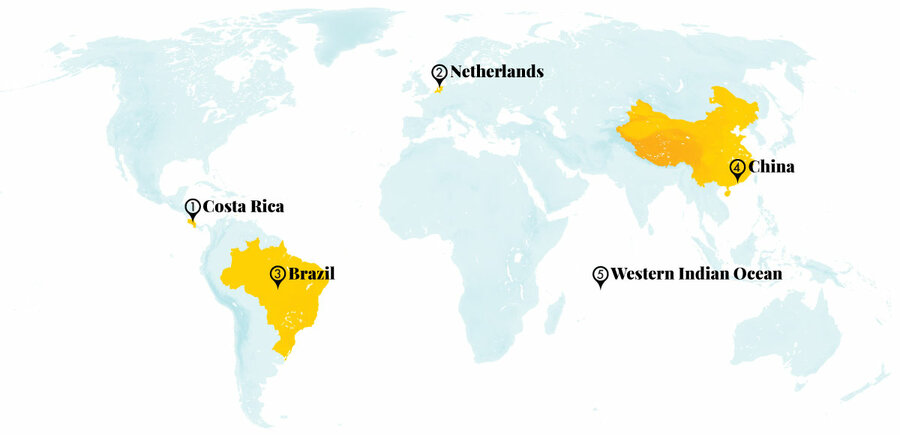

In the first of two stories today about caring for the creatures that share this planet, we find progress in a Hong Kong ban on ivory, habitat protection efforts in Costa Rica, and a new 10-nation alliance to conserve areas of the Indian Ocean.

Shut the door, and stay out of the way: Strategies to help wild animals

In Costa Rica, photographic evidence proved that conservation measures worked, and showed that better protections against human activity improved wildlife recovery. We also take a look at a multinational effort to protect the ocean and the growing role of women in Dutch government.

1. Costa Rica

Central America’s largest camera trap study to date proves Costa Rica’s conservation efforts successful. The Osa Peninsula, off Costa Rica’s southern Pacific coast, is one of the last sites in the region that’s home to a wide variety of rare wildlife, including elusive species of cats like jaguars, pumas, ocelots, margays, and jaguarundis. But in recent decades, human activity has created a tenuous situation for these animals.

So in early 2018, researchers partnered with local community organizations to set up 240 motion-triggered cameras across the peninsula. “Conducting a study of this magnitude is a logistical nightmare, but they could pull it off because of their strong relationships and collaborations,” said John Poulsen of Duke University, who was not involved in the study.

After sorting through 13,600 detections, they discovered that many species thought to be in decline had recovered over the past 30 years. Areas better protected from human activity offered more signs of diverse wildlife, including the largest cats, which scientists consider “indicator species” of ecosystem health. “The results were maybe not surprising,” said Dr. Poulsen. But the data show that “humans have an immense effect on animal communities, favoring smaller species, and dramatically reducing the distribution and abundance of large species.”

Mongabay

2. Netherlands

In a historic first, women have achieved gender parity in the Dutch government. The new government was sworn into office on Jan. 10 after nine months of negotiations. Of 29 ministers and secretaries of state, 14 are women. Those include Dilan Yesilgoz-Zegerius as the minister of justice and security, Kajsa Ollongren Dilan as the defense minister, and Sigrid Kaag as the new finance minister.

While Germany’s new Cabinet is also 50% women, that level of gender parity is still unusual. Twenty-one percent of government ministers around the world were women at the end of 2019. In the United States, women currently hold 27% of seats in Congress. Advocates warn that the mere presence of women in government isn’t enough to bring about true gender equality – which requires a deeper shift in societal norms and values – but note that equal representation is a good place to start.

Al Jazeera

3. Brazil

Solar power is providing energy and economic opportunity to a Brazilian village – while protecting local forests. Long outages used to be commonplace in Santa Helena do Inglês, a riverside community of around 130 residents in the Amazon, reachable only by boat. Like many remote communities, it was dependent on diesel generators or vulnerable power lines that cut through forest. Last June, in the first of four pilot projects in the Amazon, the Sustainable Amazon Foundation and energy company Unicoba gifted the town 132 solar panels, 54 lithium batteries, and nine hybrid inverters to unfurl clean energy in the region.

Brazil has been slow to take up solar power, which makes up only around 2% of its energy mix. But falling prices for the technology are expected to help facilitate adoption. In places like Santa Helena do Inglês, once a hub for illegal logging, solar power benefits residents, fishers, and small businesses – including a women-led ecolodge that had previously lost customers due to insufficient power. “It’s made a huge difference already,” said Pedro Vidal de Mendonça, the owner of a tiny grocery store. “Now, as long as the sun is shining, we know that the power won’t go out.”

Mongabay

4. China

Hong Kong, a mainstay of the global ivory trade, has banned the sale of commercial ivory products. Ivory – most of it from Africa – has long been a symbol of status in China. Because demand continues to be high, the industry as a whole is estimated to be worth around $23 billion a year. Hong Kong, a convenient point of transit for illegal goods headed to mainland China, earned a reputation as a hub of ivory production in the 1970s and ’80s; now, the government is trying to change that.

Hong Kong’s law went into effect Jan. 1, building upon China’s 2018 ban and a gradual phaseout agreed to by local lawmakers, in the hopes of finally ending the ivory trade and protecting elephants. Under the ban, the “import, re-export, and commercial possession of elephant ivory” is outlawed in Hong Kong, and offenders face a maximum fine of $1.3 million and 10 years’ imprisonment. Given concerns that the ban could lead to commercial ivory being reclassified as private and sold legally in antiques markets, the international organization Traffic recommends a management system to register and audit privately held ivory as well.

Agence France-Presse, Bloomberg

5. Western Indian Ocean

Ten countries have joined to form a first-of-its-kind network of marine conservation areas in the Western Indian Ocean. Fifty years ago, these waters were relatively virgin. Now, with the region having a coastal population of 69 million, overfishing, pollution, and climate change have become increasingly worrisome threats. The collaboration, known as the Great Blue Wall, is part of a global plan to protect 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030. Right now, only around 5% to 8% of the Indian Ocean is formally protected. The pact will promote sustainable use by communities and protect coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass meadows crucial for the health of the ocean.

Supported by the governments of Comoros, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa, Tanzania, and France (representing the island of Réunion), the effort is modeled after Africa’s Great Green Wall, a plan to plant a 10-mile-wide, 4,350-mile-long wall of trees from Senegal to Djibouti. As a group initiative, the pact may attract more international and private funding, with Ireland the first to commit a grant of €400,000 ($458,000). “Many countries ... do not have adequate financial resources to be able to implement their ocean management planning,” said Aboud S. Jumbe, an environmental scientist from the Tanzanian government. “So, any support or partnership for conserving and protecting the marine environment is appreciated.”

Mongabay

Profiles in Leadership

Rise in animal welfare laws? Thank Judie Mancuso.

In this story, we profile a woman whose compassion for pets and her determination to confront the status quo led to pioneering animal protection laws in California and beyond.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Chanté Griffin Correspondent

If you think twice about leaving your pet in the car while you run an errand – just for a minute, even on a cool day – Judie Mancuso has something to do with that. She’s an animal rights pioneer in California with outsize success creating the legal foundation for the animal welfare revolution.

In the past 20 years, Ms. Mancuso has helped pass nearly 20 animal protection laws in California – from outlawing animals in hot cars and fur trapping to mandatory microchipping of shelter animals. Many were replicated across the nation.

The “parent” of two dogs and four cats adopted from shelters started her work helping rescue pets lost in Hurricane Katrina. But, says one legislative aide, she has evolved from “a nice lady ... neophyte” to a “real threat” in her lobbying.

She works through her small organization, Social Compassion in Legislation, and her work model favors the gladiatorial arena of political battle over incremental grassroots work. “You can talk to people until you’re blue in the face,” says Ms. Mancuso, but “passing laws is where I’m going to get the greatest bang for my buck.”

Rise in animal welfare laws? Thank Judie Mancuso.

It was a civil showdown over animal testing for cosmetics, but animal rights activist Judie Mancuso remembers the firepower bristling in the room. She and three other activists facing 20 deep-pocketed cosmetics industry lobbyists crowded into a state legislator’s office in Sacramento.

“We had like every large corporation in the world against us,” says Ms. Mancuso, founder and president of the California-based animal rights group Social Compassion in Legislation (SCIL). She recites a litany of foes: “the fragrance industry, the personal cosmetics industry, Estée Lauder, Procter & Gamble.”

At issue was the California Cruelty-Free Cosmetics Act of 2018, a bill prohibiting “the sale of any cosmetic newly tested on animals or containing ingredients tested on animals.”

Democratic California state Sen. Cathleen Calgiani had convened the two sides to find middle ground. But at the end of the meeting, says Ms. Mancuso, her sole contracted lobbyist looked at her and said, “We gotta lobby up. You have to start hiring lobbyists to help you.”

Ms. Mancuso had reached critical mass: The weight brought to bear against this bill indicated the recognition of Ms. Mancuso’s outsize success in creating legal foundations for the animal welfare revolution.

In the past 20 years, Ms. Mancuso has helped pass nearly 20 animal protection laws in California – from outlawing animals in hot cars to mandatory microchipping of shelter animals, from mandates of plant-based meal options in prisons and hospitals to banning fur trapping. Many were replicated across the nation.

“There are a lot of power brokers in Sacramento that are key stakeholders that don’t want us to take aggressive action in terms of protecting animals or the environment,” says Ash Kalra, a Democratic California assembly member. “Judie will speak truth to power,” he says, whether it’s the cosmetics industry, the National Rifle Association, or the United States Cattlemen’s Association.

In the end, that showdown over the California Cruelty-Free Cosmetics Act ended with passage. Ms. Mancuso described her strategy as “war.” SCIL hired 12 lobbyists – a record for the small organization – to combat what Ms. Mancuso describes as a “misinformation campaign.” She created a “myth vs. fact sheet” refuting arguments that the bill would kill jobs, be exorbitantly costly, and be impossible to enforce due to company contracts with international suppliers.

She found industry allies in environmentally conscious companies: “We had Lush Cosmetics testify at our first hearing.” Support from Lush and a tour of John Paul Mitchell Systems’ hair products facilities showed lawmakers that the ingredient tracking required by the bill was not impossible or catastrophic to bottom lines.

Instincts of a mama bear and a pit bull

The “parent” of two dogs and four cats adopted from shelters, Ms. Mancuso, say those who know her, possesses the protective instincts of a mama bear mixed with the determination of a pit bull.

The SCIL model favors the gladiatorial arena of political battle over incremental grassroots work. “You can talk to people until you’re blue in the face,” says Ms. Mancuso, but “passing laws is where I’m going to get the greatest bang for my buck.”

Jeff Ebenstein, who partnered with SCIL for years as director of policy and legislation for Los Angeles City Council member Paul Koretz, says: “Some people take the soft-sell approach” to politics. Ms. Mancuso takes the “Lyndon Johnson approach: You get up close to them and you show them your passion. You don’t withhold it.”

Indeed, while none of five big-hitting opponents asked to comment on Ms. Mancuso’s legislative prowess responded, Bob Alvarez, a former Democratic state legislative aide who has worked with her and her opponents, says she evolved from “a nice lady ... neophyte” to a “real threat.”

Her approach has won support from liberal policymakers to conservative media outlets. In 2007, for example, as SCIL fought for passage of a spay and neuter bill, Ms. Mancuso appeared on Fox News and learned, she says, that the network was “on the side of the animals.”

The spay and neuter bill didn’t pass, but 19 of the 54 SCIL bills have passed – a gargantuan feat, says Jennifer Hauge, legislative affairs manager for the Animal Legal Defense Fund. California “always leads the nation in progressive laws, especially in the area of animal law,” she says, and SCIL’s agenda is the “leading edge” in animal welfare.

For example, SCIL’s cruelty-free cosmetics act has been replicated in six states; the Pet Rescue & Adoption Act – requiring pet shops to identify the public animal control agency, shelter, or rescue group that their animals come from – was the model for laws in four states; and more than 30 states have passed laws similar to the Animals in Unattended Motor Vehicle Act.

Although celebrities like actors Diane Keaton and Pierce Brosnan help draw attention to SCIL’s activity, funding comes mostly from “dialing for dollars,” she says. “I’m calling people, ‘Hey, we’re doing this. Can you donate any amount?’” Individual donations aren’t tax-deductible because SCIL is a political nonprofit, she explains.

“The animals are dying. Can you come?”

Hints of her vocation came early. “When I was a kid, I had dogs and I’d look into their eyes, and I just felt like we were the same,” says Ms. Mancuso, whose personal philosophy on animals evolved with time. She didn’t give up red meat until she was 17, after she met a friend who was a vegetarian. As she met other vegetarians, she was inspired to study food supply chains. “I read ‘Diet for a New America,’ which is all about how animals are treated and the impact to the environment and what it does to our health, and I thought, ‘Wow, I’m done [eating meat].’”

In 2003, when the pet shelter from which Ms. Mancuso had adopted a cat was closing due to unsafe conditions, she single-handedly headed an effort to find housing for the 100 animals scheduled to be euthanized. That leadership and networking experience led to a call in the middle of the night from a friend in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005: “The animals are dying. Can you come?”

In New Orleans, Ms. Mancuso was struck by the comfort that displaced residents felt when reunited with their furry friends: “Someone would come and say, ‘I’m looking for my poodle,’ and then we’d find it, and everybody would cry.”

When many families couldn’t locate pets that had been transported to shelters around the U.S., Ms. Mancuso, who worked in information technology, led the effort to design a computer system that allowed workers in the city to tag and register animals to reunite them with their families. She says the system facilitated “hundreds” of reunions.

From there, Ms. Mancuso’s trajectory was full-throttle advocacy. She quit her IT job and founded SCIL in 2007. In those early days, her political training came via hired lobbyists and “the authors that carried the bills for me,” particularly former Assembly member Lloyd E. Levine. She learned much “just being in the fight,” she says.

This year, SCIL will take on the oil industry. It is co-sponsoring anti-drilling legislation to protect marine life after an oil spill gushed nearly 25,000 gallons of crude oil into the water near Ms. Mancuso’s Laguna Beach community in October, killing marine life and temporarily closing beaches.

Although it often feels like pushing a boulder up a mountain, she says, “if we don’t seize the moment when the moment is in front of us, we’re never gonna get it done.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A new insight on Putin’s moves against Ukraine

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Russian troops are poised to invade Ukraine and yet many experts disagree on why. Does President Vladimir Putin want to restore the Russian Empire? Prevent Ukraine from joining NATO? Split Europe from the United States? Well, now add another theory to the mix.

Based on a new report from corruption watchdog Transparency International, seven countries in the former Soviet Union – from Estonia to Uzbekistan – have made significant reforms toward honest and clean governance in the last few years. Not so in Mr. Putin’s Russia. In the report’s ranking of countries on perceptions of corruption, Russia’s score has worsened.

It may be only a matter of time before Russian citizens wonder why so many neighbors are moving toward civic equality, transparent government, and other essentials for curbing corruption. Ukraine’s moves toward democratic ideals since 2014 may be driving Mr. Putin to end its progress.

Many nations have rallied behind Ukraine and are sending arms and money. They would only do so knowing that Ukrainians reject corruption as a social norm. And that also sends a strong signal to Russians to do the same.

A new insight on Putin’s moves against Ukraine

Russian troops are poised to invade Ukraine and yet many experts disagree on why. Does President Vladimir Putin want to restore the Russian Empire? Prevent Ukraine from joining NATO? Split Europe from the United States?

Well, now add another theory to the mix. Based on a new report from corruption watchdog Transparency International, seven countries in the former Soviet Union – from Estonia to Uzbekistan – have made significant reforms toward honest and clean governance in the last few years. Not so in Mr. Putin’s Russia. In the report’s ranking of countries on perceptions of corruption, Russia’s score has worsened. A new law, for example, has made reporting on corruption even riskier for pro-democracy activists.

It may be only a matter of time before Russian citizens wonder why so many neighbors are moving toward civic equality, transparent government, and other essentials for curbing corruption. Ukraine’s moves toward democratic ideals since 2014 may be driving Mr. Putin to end its progress. The country has a close association with Russian history, culture, and geography.

While Ukraine has instituted a host of anti-corruption reforms under President Volodymyr Zelenskyy since 2019, the Transparency report shows one of Russia’s other neighbors, Armenia, is the world’s top mover in making anti-corruption changes over the past few years. And that is despite the fact that the small landlocked nation of nearly 3 million suffered an embarrassing defeat in a brief war with Azerbaijan in 2020, triggering political turmoil.

Armenia’s military loss in the war, however, has been widely attributed to the country’s legacy of corruption from the Soviet era. It has stirred even more support for reforms, such as laws for an independent judiciary and a rule for public figures to declare their financial interests. By setting up anti-graft watchdogs, Armenia can help guarantee the country’s security, says Haykuhi Harutyunyan, head of a new body to prevent corruption.

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, a reformer who rose to power in a 2018 nonviolent “velvet” revolution, promised to end the country’s oligarch-led kleptocracy. “There will be no privileged people in Armenia and that’s it,” he said after taking power.

The Transparency report finds Armenia has “expanded civil liberties, paving the way for more sustainable civic engagement and accountability.” If such reforms in many of Russia’s neighbors are the real threat that worries Mr. Putin, they could also be the best defense against Russian meddling. Many nations have rallied behind Ukraine and are sending arms and money. They would only do so knowing that Ukrainians reject corruption as a social norm. And that also sends a strong signal to Russians to do the same.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

You can play a role in improving government

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Mark Sappenfield

Sometimes the state of governments around the world can seem discouraging. But as the Monitor’s Editor, Mark Sappenfield, explores in this short podcast, starting from a spiritual perspective empowers us to play a part in contributing to better government.

You can play a role in improving government

To listen, click the play button on the audio player above.

For an extended discussion on this topic, check out “You can play a role in improving government,” the Jan. 10, 2022, episode of the Sentinel Watch podcast on www.JSH-Online.com.

A message of love

Prayers for peace

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about Black LGBTQ Christians sharing stories about their faith and seeking new ways to build community in Black churches.