- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 12 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A mountain lion downtown

My breath always quickens when, from my deck, or supermarket, or nail salon, I glimpse mountain trails I’ve scaled in the wilderness backdrop of my Southern California town. From our urban setting, you can – within minutes – walk into backcountry and see no one else within the sweep of the eye. That’s a hugely refreshing boon to the health of the community and the larger ecology.

We covet and cultivate wild spaces – but how wild?

When news hit in late April of the first documented sighting in 30 years of a mountain lion wandering canyons and hills here in Laguna Beach, it triggered a gulp. I’ve made my peace with wandering near coyotes, rattlesnakes, and bobcats. But 100-plus pound apex predators? Not so much. And this morning – May 9 – police alerts said that at 1:30 a.m. that same cat was wandering Laguna Beach boutiques on Pacific Coast Highway.

In the past two months, the region has been having a mountain lion moment. Three were killed crossing highways – one near a planned wildlife crossing. The cat sighted today actually was e-collared and released in March after it ran into an office in an Irvine, California, shopping plaza. (Authorities stress it shows “appropriate fear of humans.”) Another was seen wandering the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles.

Winston Vickers, who collared the Irvine and Laguna Beach intruder and co-directs the California Mountain Lion Project, offers some sensibility on how to think about this.

He compares mountain lion-human interaction to the “very low likelihood” of shark attacks. And there’s no uptick in negative interactions or attacks. What’s new is our awareness of the cats, he says.

“The positive message,” he adds, “is that, wow, we’re in this big urban matrix of Southern California, and we’re managing to live with this large predator threat. Mostly the predator is happy and we’re happy.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

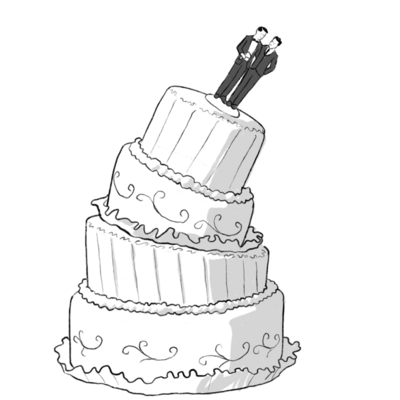

With Roe in peril, ‘slippery slope’ looms larger for LGBTQ Americans

The Supreme Court appears on the cusp of overturning the right to abortion. Would that also affect other rights unpopular with conservative Christians?

In late 2019, Lorah Trumbaturi and Stephanie Rogers were married under the wide Texas sky in a rural county west of San Antonio.

It was the end of a long, and sometimes difficult, journey. Ms. Rogers is a lesbian and Ms. Trumbaturi is trans, and in the seven years they’ve been together their parents had gradually, sometimes awkwardly, warmed to their partnership.

But a ride off into the sunset did not follow. In fact, their union began another long, difficult journey. First, the pandemic struck. Now, legal winds are rising that could uproot the rights that have helped them feel like safe, valued, and equal members of society.

Last week, a draft opinion overturning the right to abortion leaked from the U.S. Supreme Court. While the final opinion could be different, and while the draft opinion stressed that the abortion right lies on shakier legal ground than other rights not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, many legal experts are less sure.

Ms. Rogers admits she has had trouble sleeping. But she still has some dark humor. Will Texas try to unmarry them? Should they get married in a bunch of other states? Or set up an LLC to protect their assets in a state that recognizes their marriage?

“I am no longer imagining that there is a slippery slope,” she says. “There is a slide happening. It could pick up speed.”

With Roe in peril, ‘slippery slope’ looms larger for LGBTQ Americans

In late 2019, Lorah Trumbaturi and Stephanie Rogers were married under the wide Texas sky in a rural county west of San Antonio.

It was the end of a long, and sometimes difficult, journey. Ms. Rogers is a lesbian and Ms. Trumbaturi is trans, and in the years they’ve been together – first in Southern California and then in Texas – their parents had gradually, sometimes awkwardly, warmed to their partnership. Her father is accepting, says Ms. Rogers, though probably not affirming.

But a ride off into the sunset did not follow. In fact, their union began another long, difficult journey. First, the pandemic struck, and in a state where LGBTQ couples can feel uncomfortable in public, they could barely be in public at all. Now, legal winds are rising that could uproot the rights that have helped them feel like safe, valued, and equal members of society.

Last week, a draft opinion overturning the right to abortion leaked from the U.S. Supreme Court. While the final opinion could be different, and while the draft opinion stressed that the abortion right lies on shakier legal ground than other rights not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution (known as unenumerated rights), many legal experts are less sure.

Three current members of the court voted against recognizing a right to same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges – including Justice Samuel Alito, the author of the leaked draft opinion – and have repeated their objections that it has “ruinous consequences for religious liberty.” Conservative lawmakers and lawyers have argued recently that same-sex marriage carries the same fundamental flaw as other unenumerated rights. Meanwhile, red states around the country are enacting laws and policies targeting LGBTQ youth and their parents.

Sitting in a cafe in Dallas last month, weeks before the leak of the draft opinion, Ms. Trumbaturi and Ms. Rogers link arms. It’s been seven years since Obergefell, they note – seven years that have transformed their lives and how they feel society views them. But now they’re starting to feel whiplash.

“There has been a lot of progression,” says Ms. Trumbaturi, but “it can erase pretty easily, because it’s such a marginalized group.”

Speaking on the phone last week, after the leak of the draft opinion, Ms. Rogers admits she has had trouble sleeping. But she still has some dark humor. Will Texas try to unmarry them? Should they get married in a bunch of other states? Or set up an LLC to protect their assets in a state that recognizes their marriage?

“I am no longer imagining that there is a slippery slope,” she says. “There is a slide happening. It could pick up speed.”

How “deeply rooted” are LGBTQ rights?

The past decade has seen LGBTQ rights become the leading edge of a long, steady expansion of fundamental rights – typically underpinned by the due process clause of the 14th Amendment – over the past half-century. What began with the dismantling of Jim Crow segregation in the 1960s continued with the expansion of sexual freedom rights, such as to contraception (Griswold v. Connecticut) and abortion (Roe v. Wade).

By 2003, however, most LGBTQ Americans still lived firmly in the closet. Fourteen states criminalized sodomy, and there were no same-sex spouses – at least officially. The Supreme Court legalized sodomy that year in Lawrence v. Texas. The next year, Massachusetts became the first state to legalize same-sex marriage. Twelve years later, as norms changed and same-sex relationships became more visible and accepted – with 37 states and Washington, D.C., following Massachusetts’ lead – the high court delivered the Obergefell ruling.

Both the Lawrence and Obergefell decisions followed a similar rationale – a rationale that dates back to the Supreme Court’s contraception and abortion rulings of the 1960s and ’70s. The due process clause of the 14th Amendment – holding that a state cannot deny a person “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” – protects certain substantive, unenumerated rights from government intrusion.

Many unenumerated rights have been recognized by the courts, but this “substantive due process” doctrine has been criticized by conservatives for empowering unelected judges with the ability to “create” rights that don’t flow directly from the text of the Constitution.

In the draft opinion for Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health leaked to Politico last week, Justice Alito writes that overturning Roe and a related case, 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey, “should [not] be understood to cast doubts on precedents that do not concern abortion.”

Some analysts are skeptical that the end of Roe would quickly result in the end of Obergefell and other LGBTQ rights.

But other legal experts have doubts. In the draft opinion, for example, Justice Alito writes that the court “has long asked whether the [unenumerated] right is ‘deeply rooted in [our] history and tradition.’” The right to same-sex marriage would likely not fall into that category.

In the coffee shop in Dallas, Ms. Trumbaturi says her wife “worries too much.”

“I’m a professional worrier,” Ms. Rogers replies.

And she does worry, she continues, that the country is moving back toward a marginalization of LGBTQ people. Then she worries about the consequences that could have.

“One of the things that’s always been said in the LGBT community is, if you just get to know your gay friend, your gay neighbor, your trans friend, your trans neighbor, whatever, you will begin to humanize them,” she says.

If it becomes harder to talk about and normalize LGBTQ people, she adds, “it just makes it easier for people to think of queer people as less existent, I guess, and therefore less in need of defending.”

The question of parental rights

In Florida, January Littlejohn also expresses worries, but from a very different perspective. Hers started in the spring of 2020, when her 13-year-old daughter told her she was confused about her gender and thought she might be nonbinary.

Mrs. Littlejohn became more worried when, soon after the next school year had begun, her daughter climbed into the car and mentioned, offhandedly, that school officials had asked her in a private meeting which bathroom she wanted to use.

“I had zero idea that a meeting had been set up,” she says. After she immediately contacted the school, officials told her that parents couldn’t attend the meeting if their child didn’t request it, and that information about the meeting was protected under a state nondiscrimination law.

“That is a gross violation of parental rights, regardless of the content of the meeting,” says Mrs. Littlejohn. “It is my job to protect my daughter, and they took that away from me.”

Mrs. Littlejohn and her husband have filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the Tallahassee, Florida, school district, hoping to “vindicate their fundamental rights to direct the upbringing of their children.”

A jury trial has been scheduled for January next year, but it’s not just the school district that she believes has been interfering in her relationship with her daughter. She’s concerned about how schools handle students’ feelings around gender identity and sexual orientation. But she’s also concerned about what she believes is partially a socially driven phenomenon.

“I believe [a lot of these kids] are being swept up into a social movement and not fully understanding the consequences,” she says. “I’m very concerned about the issue overall.”

It’s why she’s thankful Florida has enacted the Parental Rights in Education law.

The seven-page law requires schools to share more information with parents regarding their child’s “mental, emotional, or physical well-being.” More controversially, the law prohibits classroom instruction on gender identity or sexual orientation from kindergarten through third grade “or in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students,” and it authorizes parents to sue the school district if they believe it isn’t following the law.

“The true bulk of the bill [is] to further protect parental rights,” says Mrs. Littlejohn.

“These are distressing [times], times of crises” in a child’s life, she adds. “They need their parents the most.”

A “skim milk education”?

Critics have labeled it the “Don’t Say Gay” law. It is one of many laws and policies implemented in red states in recent months concerning LGBTQ education and health care.

Florida’s law goes into effect in July, and critics are concerned that the classroom instruction provision is so vague and ambiguous that, coupled with the potential for legal action, the existence of the LGBTQ community will be effectively erased from school life.

“The anxiety is that teachers and schools will be so scared about what the law might mean ... that they will err in favor of just abolishing any recognition whatsoever of the existence or reality or integrity of LGBTQ people and families,” said Joshua Matz, a partner at Kaplan Hecker & Fink, a law firm that has filed a federal lawsuit challenging the law, on a podcast last month hosted by the National Constitution Center.

“Parents like me who are sending their children to school,” he added, “don’t want their children to get a second-rate or a skim milk education because they’re made to feel like outcasts and they’re made to feel like their families are different and less than.”

Another wave of laws and policies, such as a directive in Texas and a law in Alabama, criminalizes parents for arranging gender-affirming care – defined by the World Health Organization as “a number of social, psychological, behavioural or medical (including hormonal treatment or surgery) interventions designed to support and affirm an individual’s gender identity” – for their minor-age children.

People receiving gender-affirming medical care must typically be over the age of majority before undergoing surgery, experts say. Numerous studies have found that gender-affirming care improves mental health outcomes for transgender youth, including lowering the odds of lifetime suicidal ideation.

Signing a law last month criminalizing certain gender-affirming care procedures in Alabama, Republican Gov. Kay Ivey said, “There are very real challenges facing our young people, especially with today’s societal pressures and modern culture.”

She signed another bill the same day prohibiting classroom discussion of gender identity and sexual orientation in elementary school.

While some believe being transgender is part of a social phenomenon that children are being peer-pressured into, studies and surveys suggest that a growing acceptance of transgender identity has led to the existing transgender population being more comfortable coming out publicly.

A study published in 2017 in the American Journal of Public Health estimated the number of transgender U.S. adults at almost 1 million. Further national surveys, it added, “are likely to observe higher numbers of transgender people” because “trends in culture and the media have created a somewhat more favorable environment for transgender people,” and because of surveys that “more often collect transgender-inclusive gender-identity data.” The number of respondents to the second U.S. Transgender Survey in 2015 more than quadrupled from the first survey in 2008-09, an indication of the “growing visibility and acceptance of transgender people in the United States.”

Some of the people who enact laws like those in Florida and Alabama think that “the mere acknowledgment of the reality of LGBTQ people [is] something like proselytizing. The words they use are grooming, or predating, or recruiting,” says Mr. Matz.

“It’s the same instinct that somehow the very presence or reality of LGBTQ people is somehow nefarious, somehow trying to win people over to the cause,” he adds.

“Every parent has the right to raise their kids, and it’s not like schools are meant to usurp that role,” says Mr. Matz.

But schools do have an important role that parents can’t fulfill, he adds, such as inculcating “very basic values” and introducing children to people who aren’t like them.

“To allow laws like this to proliferate in a wide range of settings is to invite social discord,” he continues.

Could the equal protection clause come into play?

Not everyone is fearful that the potential end of Roe this year would lead to the quick demise of LGBTQ rights like same-sex marriage.

Writing in Reason magazine, Scott Shackford says he thinks the fears “are somewhat misguided.”

The draft opinion, he notes, distinguishes abortion from other substantive due process rights because it concerns “potential life,” and because the court’s abortion rulings have failed to resolve conflict over the issue.

“The same is not true for gay marriage or LGBT issues in general,” he writes. “Americans now support gay marriage recognition.”

A majority of Americans also support Roe v. Wade, according to polling that has remained consistent for decades. Just 28% want to see it overturned, according to a Washington Post-ABC News poll out last week, while 54% say it should be upheld.

But there may also not be five votes on the current court to overturn Obergefell. Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote a 2020 opinion extending federal anti-discrimination protections to LGBTQ workers, in Bostock v. Clayton County. Justice Brett Kavanaugh dissented from that ruling, but in a different way from Justice Alito. Chief Justice John Roberts, who also dissented in Obergefell, is well known for upholding precedents he personally disagrees with.

“We are in the midst of a very obvious culture war conservative backlash on LGBT issues,” Mr. Shackford adds. “But conservative justices are not the same as conservative politicians.”

Many legal experts agree that Obergefell likely wouldn’t be overturned in one fell swoop – but, they add, Roe wasn’t either.

“There are lots of ways to diminish and undermine a right short of overturning a decision, including finding lots of exceptions,” says Carey Franklin, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law.

Interviewed again after the leak of the draft opinion, Professor Franklin points out that another clause in the Constitution – the equal protection clause – could help preserve Obergefell and Bostock, and that one conservative justice has already cited it in a decision.

“In Bostock, Gorsuch said ... it’s a matter of sex equality,” says Professor Franklin. “That could be a way of upholding LGBT decisions as matters of equality ... under the equal protection clause.”

However, she adds, “I’d be surprised if we didn’t see some chipping away in the areas of LGBT rights and contraception.”

Besides the right to marriage itself, “there’s a whole range of other considerations, like the right to adoption,” says Professor Franklin. “It could be that we see a deterioration of rights and protections even as Lawrence and Obergefell stand.”

That process may soon begin. Next term, the Supreme Court will hear a case asking whether a Colorado nondiscrimination law forcing a web designer to make websites for same-sex weddings or make no wedding websites at all violates her free speech. It is a redux of a 2018 case involving a Colorado baker, which the court decided on narrow grounds. If the court rules in favor of the web designer, it could pave the way for other forms of discrimination against LGBTQ people.

“Once you’ve limited it and restricted it, you’ve normalized it in the public’s mind, and that makes it easier to maybe overrule it at a later date,” says Melissa Murray, a professor at New York University School of Law.

On the phone last week, Ms. Trumbaturi also is unsure that public support today will protect LGBTQ rights in a post-Roe world.

“I just don’t think it’s in the limelight yet,” she says. “All the while, restrictions on transgender people have been prolific” across red states.

Whether the right to same-sex marriage is ultimately overturned or not, Ms. Rogers and Ms. Trumbaturi say they are crafting an “exit plan” to move to a more LGBTQ-friendly state. They hope to not use it – their parents live in Texas. But mostly, they hope that the equal rights they’ve come to enjoy in recent years remain. They hope to have more days like that day they were married under the wide Texas sky.

In the Dallas coffee shop last month, Ms. Rogers notes how a lot of people in her family “have come a long way ... just in general acceptance, and in being more affirming.”

“I have to have hope that people who are living in fear will have a moment when they’re like, OK, this isn’t as bad as I think it is,” she adds.

“You can’t maintain a fear state forever. People eventually have to exhale.”

Editor’s note: The article has been updated with the correct spelling of Lorah Trumbaturi’s name.

Part 1: ‘Hard for it to be a bigger deal’: The future of American rights

Can Brazil stamp out fake news ahead of presidential elections?

Fake news has been a global scourge, but Brazilians’ heavy use of social media makes them particularly susceptible. Now, Brazil is trying to set an example for cutting out misinformation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Ana Ionova Contributor

Mary Rose Filgueiras Lacerda confesses she used to forward a lot of fake news.

“I thought they were true!” she says of the fabricated stories – and she’s not alone. Although fake news has challenged citizens and governments around the world, a 2020 study found that Brazilians fall for fake news more than people in other countries, including the United States.

Brazil is one of the world’s heaviest users of social media, with about 75% of the population on at least one platform. And the way messages are sent – relying more on voice memos or images overwritten with text – makes them hard to screen. Experts say low education levels and mistrust of institutions combine with the heavy social media use to create a perfect breeding ground for misinformation here.

In 2018, a torrent of disinformation favoring President Jair Bolsonaro helped sweep the far-right candidate to a surprise victory. And with Brazil preparing for a tight presidential race in October, fake news is already ticking up across platforms.

Enter Ms. Lacerda. With the help of a local news collective, she is trying to educate herself about reliable sources and how to spot misinformation. But it’s not just nongovernmental organizations running digital literacy trainings that are combating the problem. Congress proposed legislation, and the Supreme Court has even stepped in.

Can Brazil stamp out fake news ahead of presidential elections?

Whenever a story with a wild headline came her way, Mary Rose Filgueiras Lacerda used to skim it and forward it on without any second thoughts.

But when the eye-popping stories arrived with more frequency on WhatsApp, she got suspicious. “I thought, this is strange. It can’t all be true,” says Ms. Lacerda, a retiree who lives in Divinópolis, in Brazil’s Minas Gerais state.

She decided to take action, enrolling in a digital course teaching Brazilians over the age of 50 how to spot fake news. Over five days, daily messages urged her to read beyond the headlines and to double check her sources. Short YouTube videos taught her how to spot fakes and detailed how videos, images, and memes can be doctored.

“I confess I used to forward lots of fake news, because I thought they were true,” Ms. Lacerda says. “What I learned ... showed me we need to stay alert.”

Ms. Lacerda’s concerns are not misplaced. Fake news and misinformation campaigns have hit Brazil hard over the past five years. And even with Brazil’s presidential elections still months away in October, fake news about the upcoming election is already spreading across platforms like WhatsApp, Facebook, Telegram, and TikTok.

Fake news has been a global scourge in recent years, with online messaging services and social media often overshadowing traditional media as go-to sources of information. The phenomenon has left a profound mark on Brazil, where experts say low education levels, mistrust of institutions, and heavy social media use have created a perfect breeding ground for misinformation.

Brazil is one of the world’s heaviest users of social media, with about 159 million – or 75% of the population – on at least one platform. And the way messages are sent, relying more on voice memos or images overwritten with text, makes them hard to screen en masse. In 2018, a torrent of disinformation favoring President Jair Bolsonaro helped sweep the far-right candidate to a surprise victory.

And although a fresh wave of election disinformation is fueling concerns about Brazil’s democratic health, the South American giant may also be offering new paths toward combating it. Congress has proposed legislation to curb the spread of fake news. The Supreme Court is trying to force social networks to more effectively police users. Brazil’s electoral court has struck deals with tech giants to screen out fake news and report those who create it to authorities.

And nongovernmental organizations are working to teach digital literacy and fact-checking, in hopes that with a little help, citizens can identify misinformation and play a central role in stopping its spread in their communities.

“We end up with multiple versions of the truth out there, circulating,” says Valerie Wirtschafter, a senior data analyst at The Brookings Institution, who studies misinformation in Brazil. “That’s problematic, because we know that an informed voter is what underpins democracy.”

Who is responsible?

Brazilian lawmakers have wrestled with how to crack down on disinformation for years. And it’s not just around elections – misinformation flourished during the pandemic.

Legal efforts culminated in a sweeping legislative proposal known as the “Fake News Bill,” which seeks to criminalize the spread of fake news and force social media platforms to identify financial backers of such posts. It would also limit the reach of mass messages on platforms like WhatsApp.

But the legislation, first introduced in 2020, has drawn fierce criticism from technology companies, civil society, and free speech advocates. Among its most vocal critics is President Jair Bolsonaro, who is himself under federal investigation for spreading misinformation on social media during the pandemic – including false claims that COVID-19 vaccines might raise the chance of contracting AIDS.

“The bill is not perfect, but it’s a good start,” says Felipe Nunes, a political scientist at the Federal University of Minas Gerais who studies public opinion and social media. “It has been met with a lot of resistance though.”

Last month, the bill suffered a major blow when Congress rejected an attempt to fast-track it, making the bill unlikely to advance before October’s vote.

Mr. Bolsonaro is facing off against former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva this fall. Mr. Silva, known widely as Lula, is leading early polls with 45% of the vote, to Mr. Bolsonaro’s 31%.

Last year, Mr. Bolsonaro unsuccessfully tried to ban social media platforms from removing content and users. But platforms like YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter have taken down videos of him promoting unproven “miracle cures” for COVID-19 and peddling false claims about 2018 election fraud.

Even if legislation criminalizing fake news advances, it may be difficult to implement because it would require global tech giants to usher in sweeping policy changes.

But the power of Brazil’s courts in forcing the hand of tech platforms became evident earlier this year, when a Supreme Court judge banned Telegram after Brazil’s federal police had repeatedly tried to get in touch with the platform to request the removal of what it deemed dangerous content. The messaging app then came around, signing on to rules governing misinformation set out by electoral officials.

“We will only reach a solution when platforms are made responsible for identifying and helping authorities to criminally punish those who produce fake news,” says Mr. Nunes.

New challenges

For the fake news machine churning out false information, the pandemic proved a boon.

Producers of misleading content were able to hone their craft, says Sérgio Lüdtke, who leads the Comprova Project, a monitoring collective made up of 40 Brazilian media outlets and funded by Google and Meta, the parent company of Facebook.

“It was almost like a training ground for them in what works and what doesn’t,” Mr. Lüdtke says.

Those spreading disinformation are growing more sophisticated, experts say. False messages have become increasingly subtle in how they convey their version of the news, omitting context or inviting misinterpretation instead of offering up overtly fabricated storylines. Brazilians fall for fake news more than their counterparts in other countries battling misinformation such as the United States and Italy, a 2020 study concluded, with 73% believing at least one false claim during the pandemic.

“It’s no longer necessary to invent a whole new narrative” when spreading misinformation, says Mr. Lüdtke. “It’s enough to raise doubt, to suggest a link that isn’t there, and to let people draw a false conclusion.”

This is making the work of initiatives like Comprova more painstaking. The group is currently running the course in which Ms. Lacerda and upwards of 2,200 others took part, in hopes of teaching Brazilians who didn’t grow up as digital natives how to spot fake news. “We have to figure out how people are interpreting this misleading information and then deconstruct that narrative,” Mr. Lüdtke says.

False information tends to bolster the beliefs of voters who have already picked sides, not necessarily change someone’s position, a study led by Mr. Nunes found.

“Fake news doesn’t serve to manipulate people’s opinions,” he says. It “serves to engage and mobilize people in electoral processes. ... It’s election gold.”

Standing up to disinformation

Despite the vast presence of fake news, those trying to fight the phenomenon are feeling hopeful. Ariel Freitas works for Voz das Comunidades, a favela-based news organization that is actively fighting election disinformation.

“We’re seeing all kinds of efforts to ... trick people,” Mr. Freitas says, whose team creates fact-checking posts to share on social media and Voz das Comunidades’ mobile app. But “we are much better prepared than we were in 2018.”

For one, grassroots journalists and activists have fine-tuned their skills, he says, improving how they monitor misinformation and reach people via social media who may not watch, read, or listen to traditional news outlets.

Voz das Comunidades is about to launch an elections-specific fact-checking project that will verify the claims of candidates and send out push notifications warning about false information making the rounds on messaging apps and social media.

“We’re stronger now. We can stand up to the disinformation,” Mr. Freitas adds.

Puerto Rico seeks clean-energy revolution. It is getting blackouts.

Five years ago, Hurricane Maria upended Puerto Rico’s electricity grid, and the island is still often in the dark. But it has kindled huge clean-energy ambitions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Xander Peters Special correspondent

After Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico in 2017, one obvious imperative was to rebuild the power grid, to make it more resilient and also with a focus on clean energy sources that could help combat climate change.

Five years later, just 3% of electricity in the U.S. territory is generated by renewable sources. Ongoing blackouts prompt some to leave the island altogether.

“People say, ‘I’m paying more for my electric bill. We have more blackouts than ever. Why bother?’” says Ramón Luis Nieves, a former member of the Puerto Rico Senate in the San Juan area.

The reality isn’t hopeless, however. Many individuals are installing solar panels on their own. A post-Maria law envisions rapid expansion of clean energy supplies and breaking a monopoly in the electricity market. The government has recently emerged from a five-year period of bankruptcy, with the U.S. government also providing aid. These are signs of the kind of ingenuity and collaboration that could help both repair the grid and buoy the island’s society and economy.

“It’s really hard to trust that it will get better if you don’t see, hear, or read about improvements to the infrastructure,” says San Juan resident Olga Otero. “If it doesn’t get better, it doesn’t change.”

Puerto Rico seeks clean-energy revolution. It is getting blackouts.

Within seconds on a Wednesday evening in early April, more than 1 million Puerto Ricans were without power. Marilu Mayorga and her longtime partner Bill Greenberg were among them.

“The street, it’s total, complete darkness,” Ms. Mayorga said as she stepped outside their home. She could smell the gasoline fumes coming from her neighbor’s generator. She could hear its engine purr. “I’m seeing police lights outside. What’s happening? It’s so dark out here.”

It was dark in many other communities too. One of the island’s four main power plants had suffered the failure of a circuit breaker, erupting in flames. For five days, many Puerto Ricans remained without power. Public schools and government agencies temporarily shuttered.

Nearly five years after Hurricane Maria devastated this territory of the United States – claiming nearly 3,000 lives and prompting the longest power outages in U.S. history – Puerto Rico’s electric grid remains far from revived. Instead, its troubles symbolize deep challenges on the island, as climate change calls for both a greener power supply and resilience against increasingly powerful storms.

The devastation of Maria was an unavoidable call to action. The plodding follow-up is raising questions about governance, and is taxing residents’ patience while prompting some to leave the island altogether. Puerto Rico’s population of 3.2 million people is about 11% lower than in 2010.

“There’s a whole generation here, after Maria, that left the island. They couldn’t handle” the dysfunction anymore, says Ramón Luis Nieves, a former member of the Puerto Rico Senate in the San Juan area. “People say, ‘I’m paying more for my electric bill. We have more blackouts than ever. Why bother?’”

The reality here isn’t hopeless, however. Alongside the presence of fuel-burning generators, a fast-growing number of residents are installing their own solar panels. A post-Maria law envisions rapid expansion of clean energy supplies. And the government has recently emerged from a five-year period of bankruptcy, seeking a fresh start, with the U.S. government also pledging $12 billion early this year to bring Puerto Rico’s grid to a state of reliability.

Those are all signs of the kind of ingenuity and collaboration that ultimately could not only repair the grid but also buoy the island’s society and economy, too.

Still, the hurdles are formidable.

Many residents say blackouts are frequent even as their electric bills have in some instances tripled.

“It’s really hard to trust that it will get better if you don’t see, hear, or read about improvements to the infrastructure,” says San Juan resident Olga Otero. “If it doesn’t get better, it doesn’t change.”

When Hurricane Maria struck the territory in September 2017, people in the island’s populated areas were without power for months; for others, such as those living in its mountains, as long as a year.

Puerto Rico’s “Green New Deal”

In 2019, lawmakers approved a law known as Act 17 that would end the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority’s monopoly on energy distribution. Among the landmark law’s intentions was eliminating PREPA’s use of coal by 2028, and supplying 40% of electricity from renewable sources by 2025, rising to 100% by 2050.

“It’s like Puerto Rico’s ‘Green New Deal,’” says Javier Rúa-Jovet, a solar advocate, global energy attorney, and the former chairman of the Puerto Rico Environmental Quality Board.

But like many well-intentioned clean energy efforts on the U.S. mainland, Act 17’s ambitions have so far fallen short. Local residents and experts see a mix of complicating factors here, from bureaucratic foot-dragging to a long-standing failure to open the island’s electricity market to greater competition – including in clean energy. In March PREPA announced that the initial goal of 40% renewables by 2025 won’t be met.

Debt is another obstacle. Even with the territory’s overall debt restructuring, PREPA remains saddled with a staggering $9 billion in obligations, to be paid back through higher utility rates over the next 47 years. In March, amid rising global energy prices, Puerto Rico Gov. Pedro Pierluisi canceled that debt paydown plan, saying it was not feasible. Arty Straehla, chief executive of PREPA creditor Mammoth Energy, chided the decision to terminate the debt restructuring as “another example of Puerto Rico and PREPA continuing their resistance to pay their bills.”

At the moment, three years into Act 17, Puerto Rico generates just 3% of its power from renewables, with the rest coming from fossil fuels, such as petroleum (49%), natural gas (29%), and coal (19%), according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Clean energy advocates say that stands in stark contrast to the potential Puerto Rico has for renewable power – everything from utility-scale generation to community microgrids to individual rooftop solar. Recent research by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory found that Puerto Rico receives enough sunlight to meet its residential power needs at least four times over.

Small steps forward

For the territory to succeed in its hoped-for energy revolution, it will require considerable organized effort – yet it may also come due to small actions by people like Carla Giovonnani.

“You have to love your island to stay here and try to move it forward,” says the San Juan resident.

Ms. Giovonnani had solar panels installed on her modest home in a working-class neighborhood earlier this year. She’s been off the grid since March.

She realizes solar power is a luxury many Puerto Ricans, like her father, lack access to. At her father’s business, where he sells school uniforms, when the power goes out, he closes shop.

“He can’t have clients inside his store” because it becomes too hot, Ms. Giovonnani says. If he doesn’t crank the generator during a blackout, “he cannot work.”

Así es la vida en Puerto Rico. That’s life in Puerto Rico, some residents say.

Ms. Otero, also in San Juan, says she panics every time her phone dips below 50% percent charged.

“We, as a country, have some sort of PTSD, because I never let my phone run out of battery,” Ms. Otero says. “Because you never know when you’ll be without a power source. You could have emergencies or something, and then you’re” without a means of reliable communication.

“I’m sure I’m not the only one,” Ms. Otero adds.

Despite the slowness of Puerto Rico’s energy recovery, hope remains on the horizon – in solar.

Mr. Rúa-Jovet notes the change in recent years in how Puerto Ricans view solar as an answer to blackouts. Before Maria struck, less than 1% of the energy used on the island was coming from distributed solar. Now that amount, while still modest, has nearly tripled in a few years.

“When events like yesterday and today’s blackouts happen, it just multiplies,” Mr. Rúa-Jovet says.

In the tiny town of Maricao, with 5,000 people, locals recently began moving to build their own microgrid. The mountain community was awarded the opportunity through the Interstate Renewable Energy Council. Out of 12 municipalities that applied for the grid in Puerto Rico, Maricao was deemed the most needed.

While such community-based solutions may become increasingly common, many towns and neighborhoods across the island are, for now, awaiting a fix – at times, in darkness.

Ms. Mayorga and Mr. Greenberg’s power in Dorado remained off for three days after the Costa Sur power plant failure. In such events, they go through a routine, with Mr. Greenberg tossing an extension cord off their home’s balcony and then running it to the generator next door. Their neighbor generously lets them borrow its power to make up for the engine’s smell.

Meanwhile, the outage disrupts their remote work lives. The dysfunction has begun to weigh on them, as it has for many in Puerto Rico. The couple is unsure of what comes next, or if they’ll stay.

“This is not sustainable,” Ms. Mayorga says.

Points of Progress

Ocean surprises: Get out your microscope and headphones

In our progress roundup are stories about joy following confusion and doubt. As scientists discovering new species and the recovery of a coral reef show us, serious research need not be devoid of fun.

Ocean surprises: Get out your microscope and headphones

Along with new science and technology developments around the world in ocean health and malaria prevention, in the U.S. this spring the impact of Emmett Till’s life and death was observed in the performing arts and in federal law.

1. United States

Lynching became a federal hate crime amid wider efforts to honor the legacy of Emmett Till. The Black teenager was tortured and killed by white supremacists in 1955 after a white woman accused him of whistling at her, and his death galvanized the civil rights movement. After over a century of failed efforts to pass similar legislation, President Joe Biden signed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act on March 29. The law punishes conspiracy to commit a hate crime that causes serious bodily injury or death with up to 30 years in prison. Legal experts warn that legislation alone is not enough to prevent hate crimes, but many say the law serves an important symbolic purpose.

The law comes at a time when the impact of Emmett’s death is gaining renewed attention. The Senate passed a bill in January to posthumously award Emmett and his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian honor awarded by Congress. The legislation is awaiting approval in the House. In Chicago, where Emmett was born, Collaboraction Theatre Company presented a play called “Trial in the Delta: The Murder of Emmett Till” based on direct transcripts of the trial. And a limited TV series, “Women of the Movement,” centering around Ms. Till-Mobley’s relentless pursuit of justice for her son, is airing on ABC this year.

NPR, NBC News, Chicago Tribune, Garden & Gun

2. Tanzania

“Mosquito grounding” bed nets lowered malaria rates among children by nearly half in a scientific trial in Tanzania. The addition of the chlorfenapyr insecticide paralyzes mosquitoes, preventing them from finding their next host. Tanzanian researchers collaborated with scientists from London and Ottawa to test the nets through a randomized trial that included 4,500 children from 72 villages in the district of Misungwi. They found that the nets lowered malaria rates by 43% in the first year and 37% in the second.

Because prevention programs have led to insecticide resistance in mosquitoes, the researchers are proceeding with caution. But in a country where malaria is one of the leading causes of death, especially among children, the results are welcome news. “By essentially ‘grounding’ the mosquito, our work ... has great potential to maintain control of malaria transmitted by resistant mosquitoes in Africa,” said Dr. Manisha Kulkarni, a scientist at the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Medicine.

EurekAlert

3. Germany

High-altitude kites are giving wind energy an added lift. Wind turbines are becoming an increasingly affordable piece of the world’s energy puzzle, but they take up large swaths of space and can’t be installed in remote locations like deep oceans, or reach the highest heights where winds blow fastest. Based on estimates, airborne wind energy (AWE) systems could generate 4.5 times as much power as ground-level systems.

German company SkySails Power launched the world’s first marketed AWE system this past December, with five massive sails already sold. In Mauritius, one sail currently generates 100 kW of electricity, enough to power 50 homes. The sails are programmed to fly autonomously in a figure-eight pattern at altitudes of up to 800 meters (2,600 feet), and energy is generated by the sail’s tether and a winch on the ground. Various AWE technologies came into focus when Google’s parent company, Alphabet, supported a similar project, Makani. It ultimately folded for financial reasons in 2020, but Makani’s research and patents were made available for others to access freely. Companies like Kitepower in the Netherlands and Kitemill in Norway are also working on AWE systems.

Yale Environment 360 Greentech Media

4. Indonesia

A coral reef destroyed by blast fishing is making a full, noisy recovery. Using visual surveys, researchers could see that the coral reef in the Spermonde Archipelago in central Indonesia was making a comeback, but they didn’t know to what extent until they began listening. They spent countless hours observing the snaps, purrs, and grunts of the underwater soundscape, excited for a break from the silence of unhealthy reefs. Computerized measurements confirmed the sounds were comparable to reefs that had never been damaged.

“We kept discovering sounds we had never heard. Some were a bit familiar but some were just like, ‘I have no idea what that is.’ It was a real sense of adventure and discovery,” said Tim Lamont, a researcher from the University of Exeter in England and co-author of a study presenting the findings. Specialists from the Mars Coral Reef Restoration project restored the reef by installing webs of sand-coated steel “reef stars” to bridge barren gaps between surviving corals, helping new corals grow quickly. But those involved say restoration shouldn’t replace harm prevention. Blast fishing, which uses explosives to stun and collect fish, is outlawed in much of the world but remains widespread across Southeast Asia and other regions.

The Guardian

Oceans

Scientists discovered two new nitrogen-fixing phytoplankton species. On the surface of the ocean, nitrogen gas is plentiful – it dissolves from the air above – but not useful to most aquatic organisms. Researchers from the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa found two microscopic diatoms, Epithemia pelagica and Epithemia catenata, capable of converting nitrogen gas into ammonia, which in turn supports plant, algae, and microbial life – and the entire aquatic food chain.

The scientists later learned that these “self-fertilizing” organisms live in oceans around the world. “Both of these diatom species are remarkable because they represent previously unrecognized sources of nitrogen-fixation in the ocean, which is a critical process that helps sustain primary production in nutrient-poor environments,” said Chris Schvarcz, one of the researchers on the project.

A better understanding of how nitrogen-fixing plankton operate is crucial for predicting the impact of warming oceans on biological productivity, according to the study. Or as Grieg Steward, a co-author and professor who worked with Dr. Schvarcz, put it: “Chris’s work is an important reminder of how much one can still learn with a little patience and careful observation!”

Mongabay, University of Hawai’i News, Nature Communications

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Good faith elections of US presidents

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a few weeks a congressional panel will hold public hearings on the violent attempt last year to disrupt the formal certification of the 2020 presidential election. The Jan. 6 committee’s immediate goal will be to share what it has learned about who was behind the attack on the Capitol. Those findings may help promote accountability and help clarify why, for instance, it took so long for additional security forces to be deployed.

While the Jan. 6 committee has drawn more public attention during the past year, small working groups in the House and Senate have been drafting reforms to an 1887 law called the Electoral Count Act. The law attempted to clarify the roles and authority of state governments and Congress in the conduct of choosing a president, a decade after the disputed presidential election of 1876. It spelled out how states were supposed to choose electors to the Electoral College based on the popular vote, and how Congress is supposed to count those slates of electors.

Since January at least 16 senators have come together to redraft the law. Their proposals reflect more than a desire just to fix old and muddled English.

Good faith elections of US presidents

In a few weeks a congressional panel will hold public hearings on the violent attempt last year to disrupt the formal certification of the 2020 presidential election. The Jan. 6 committee’s immediate goal will be to share what it has learned about who was behind the attack on the Capitol and whether it was organized or spontaneous. Those findings may help promote accountability and help clarify why, for instance, it took so long for additional security forces to be deployed.

But experience has shown in countries where truth commissions have followed periods of violent conflict that restoring divided societies requires more than sunlight. “To rebuild lives without fear of recurrence and for society to move forward, suffering needs to be acknowledged, confidence in state institutions restored, and justice done,” Michelle Bachelet, United Nations high commissioner for human rights, has observed. “Without humility and modesty, the risks of failure are real.”

On Capitol Hill, those qualities may be restoring more than trust across the aisle. They are impelling what may turn out to be the most important result of this Congress: the renewal of what historian Joseph Ellis calls “the great achievement” of America’s constitutional design – its unique and uniquely frustrating sharing of power between the states and federal government.

While the Jan. 6 committee has drawn more public attention during the past year, small working groups in the House and Senate have been drafting reforms to an 1887 law called the Electoral Count Act. The law attempted to clarify the roles and authority of state governments and Congress in the conduct of choosing a president, a decade after the disputed presidential election of 1876. It spelled out how states were supposed to choose electors to the Electoral College based on the popular vote, and how Congress is supposed to count those slates of electors.

The statute provided the basis for the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore to resolve the 2000 presidential election. It also provided the basis for disputing the 2020 results by giving Congress power to oppose electors if a member from both the House and Senate had reasons to question their legitimacy. Critics have long decried the law as unconstitutional.

Since January at least 16 senators have come together to redraft the law. Their proposals reflect more than a desire just to fix old and muddled English. The different versions would require significantly more than one member from each chamber to raise objections to slates of state electors. That may be an acknowledgment that Congress itself has some blame to bear for the events of Jan. 6.

“I think sometimes when the going gets tough we just say, ‘That’s too hard,’ and we retreat to the party messages,” Sen. Lisa Murkowski, the Alaska Republican, told CNN. “But we have got to get to the place where we understand one another. And you can’t get to understanding without listening.”

That sense of deference and civility may be why the push to reform the law is happening largely out of public view. It reflects what the framers of the Constitution may have had in mind when they rejected a system of consolidated power. That diffusion of authority between the states and federal government, argued Gouverneur Morris, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention from Pennsylvania, perpetuates an argument that can only be resolved through “the good faith of the parties.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Have you mistaken your identity?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karyn Mandan

As we come to realize that God made all His children flawless and whole, not vulnerable and mortal, healing naturally results.

Have you mistaken your identity?

“How unbelievable is this!” I said to myself as I rushed across a crowded store to greet a friend I hadn’t seen in years. As I got closer, however, it was obvious this was not the friend I thought it was. It was only a mistaken identity.

In this case, mistaking someone’s appearance was no big deal. But other times, mistaking what we think we see for the reality that we need to see can have painful consequences. And correcting that misperception can bring healing.

I found this out one day 20 minutes before a friend and I were each to give a presentation at a community event. I was suffering from congestion and nausea, and thought I might faint.

My friend looked at me with such tenderness, and then said, “You’re not who you think you are.”

I was startled. My friend is a gentle person who looks out for others. What did she mean? Sick, weak, and nauseated – this wasn’t me?

Referring to everyone’s inherent Godlike nature, Christ Jesus said, “You shall be perfect, just as your Father in heaven is perfect” (Matthew 5:48, New King James Version). Many events in the Bible show the transformative effect of understanding our true self as God’s children, unlimited and spiritual. Once Jesus encountered a man who’d been sick for 38 years. Jesus asked him if he wanted to be well. The man explained that he had no one to help him get into a nearby pool of water that was believed to have curative power when it bubbled up. The man was discouraged because help never arrived in time.

He may have been surprised when Jesus responded compassionately that the man didn’t need to wait any longer to be well. Jesus told him to get up, and right then and there he stood up and walked freely (see John 5:1-9).

The man had mistaken what he saw materially for the reality that he needed to see spiritually. Jesus’ recognition of this man’s identity as forever perfect was spot on. This understanding was so illuminating that it changed the man’s perception of himself and restored his mobility.

I knew from my own experiences that prayer can have a healing effect, so I found a quiet room to think about these ideas. The Bible teaches that each of us is created and maintained by ever-present and all-loving God, who is Spirit, divine Love itself. Divine Spirit remains undiminished in perfection and goodness. And emanating from Spirit, we are spiritual and inherently manifest the divine nature. Each of us has a direct and unbreakable relation to God, and this keeps us whole. As we feel the power of this truth, we are healed.

I realized that my friend’s words, “You’re not who you think you are,” were a supportive invitation to turn my thought away from suffering toward a new, restorative view about myself. Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered Christian Science, wrote in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” (referring to “Science” as demonstrable Truth), “The Science of being furnishes the rule of perfection, and brings immortality to light” (p. 336).

Expectantly, I prayed with a sincere desire to know my genuine, harmonious, spiritual selfhood. As I became willing to let go of the belief that I could be separated from God’s goodness, I started to grasp my fundamental nature as an expression of the one perfect God.

Soon I gained a sweet confidence that as Spirit’s likeness, I couldn’t be compromised. I’d felt vulnerable and afraid. Now I felt cared for, safe, and peaceful. I quickly regained strength and the congestion cleared, and I gave my presentation with ease.

Sickness, suffering, and limitation aren’t truly part of anyone’s being. Real identity is a healthy, well, and unlimited spiritual expression of God. What a joy to have this true identity come to light – overcoming the effects of a mistaken identity – enabling us to get up and go forward strong and free as God made us to be.

New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

A message of love

In Sri Lanka, a long wait

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Come back tomorrow when Washington bureau chief Linda Feldmann shares a letter from women in Princeton University’s Class of 1972 – classmates of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito – reacting to his leaked draft decision that would overturn Roe v. Wade.