- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Will your future car be an Apple or a Sony?

Have you heard about the car with no windows?

If you love vehicular innovation then you might have seen that Apple’s been filing patents reportedly aimed at developing an autonomous ride that would pair virtual reality feedback with exterior cameras and could, well, look like a giant wireless mouse on wheels.

Extreme? Sure. It’s one scout’s rendition. And yes, developers often flaunt capabilities in the way that fashion houses strut ensembles on the runway that won’t appear on the street. But pause for a moment to consider that we’re talking about Apple and automaking.

When I reported back in 2006 about a little startup called Tesla, auto-industry sources were skeptical about any “boutique” electric vehicle (EV) makers taking business from the bigs. It happened, pushing automakers to evolve.

New research from Ernst & Young hints at a “global tipping point” for EVs, with “more than half of car buyers saying they want their next car to be an EV.”

Next, the arrival of new players. Last week, smartphone manufacturer Foxconn struck a deal to buy an EV startup’s plant in Ohio. Earlier this year, Sony announced it would unveil a vehicle division. Others have piled on.

What does it mean? You might know some early adopters, but mainstream car buyers are slow to change. There’s still near-term doubt about autonomous cars (I wrote about self-parking, a baby step, fully 15 years ago).

Social evolution is slower than mobility tech. There are huge issues, old and emerging: safety, foremost. Also privacy, with the idea that more cars might soon require subscription updates (adding recurring costs and digital-divide concerns).

Still, we’re seeing the start of a bigger rethink around mobility. Who’ll lead in ways that scale – that serve societies, and the planet?

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

How an Army ethicist works to mold moral soldiers

A chaplain and decorated Army veteran works to teach soldiers how to look at missions through the lens of values: exercising a sense of fairness, respect, and honor toward opposing forces.

-

By Mary Beth McCauley Special contributor

War is not some abstract idea for Maj. Jared Vineyard. Neither are ethics.

Major Vineyard’s grandfathers served in World War II. As a senior at West Point, he watched on TV as the twin towers were attacked on 9/11. He then went to war himself, losing friends on the battlefield along the way.

Now, as an Army chaplain and ethicist, he has one of the toughest jobs in the military: He is charged with illuminating the line between right and wrong at a time when the ways to kill grow ever more sophisticated.

It’s a tall order at Fort Benning, Georgia, where soldiers are trained to win wars – trained to kill.

Major Vineyard’s job here is to make sure they win wars ethically. Ethics protect soldiers from what he calls “moral injury,” the psychological damage that can come from doing the wrong thing. They also protect nations from committing the kinds of atrocities that the United States committed at My Lai during the Vietnam War and at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, and the acts Russia commits almost daily in Ukraine.

“Beware,” he’s fond of saying, “lest you become the monster you perceive your adversary to be.”

“Combat changes you,” Major Vineyard says. “You can come out better or you can come out worse. You get a vote in that.”

How an Army ethicist works to mold moral soldiers

Maj. Jared Vineyard loves the Army. This, despite the car bomb in Iraq that took the lives of eight in his platoon. This, despite the faces around him of combat veterans who have seen “too much.”

Major Vineyard, an Army chaplain, U.S. Military Academy at West Point graduate, and decorated war veteran, is emerging as one of the military’s premier ethicists. He is charged with illuminating the line between right and wrong at a time when war seems but a hair trigger from peace, when the ways to kill grow ever more sophisticated, when the consequences stream round the world instantaneously.

But where some see danger, Major Vineyard sees opportunity. “The ability to do good is probably higher in the Army than in any other profession,” he insists.

That’s not necessarily obvious here at Fort Benning, Georgia, where people come to learn to kill. Some 60,000 soldiers train at the base every year, learning to shoot, jump from planes, crawl to cover. It’s a place where camo is regulation, not fashion; where boots are heavy and hair is sheared; where acronyms – IED, RPG, WMD – are a principal part of speech. The massive base covers some 285 square miles.

Its Maneuver Center of Excellence (MCOE) trains soldiers to win wars. Major Vineyard’s job here is to make sure they win them ethically, in a way that reflects the laws and values under which the Army operates. Ethics protect soldiers from what he calls “moral injury,” the psychological damage that can come from doing the wrong thing. They also protect nations from committing the kinds of atrocities that the United States did at My Lai during the Vietnam War, and Russia does almost daily in Ukraine.

In his 2 1/2 years at Fort Benning, Major Vineyard has taught more than 15,000 soldiers, most of them officers. His lectures provoke, inspire, entertain, and challenge. They are laced with personal stories of his own and others’ experiences, stories shared among soldiers, but – as personal war stories tend to be – kept within the fold. Beyond the presentations and diagrams, ethical leadership comes down to two questions, he says: “Can I do it?” and “Should I do it?” Military decisions that are moral as well as legal allow warriors to “sleep the sleep of the just,” he says.

“All of the lieutenants who have come through Fort Benning, all of the captains who have come through Fort Benning for their professional military education, all of the future battalion and brigade commanders who come through Fort Benning – Jared Vineyard’s thumbprint is on every one of them,” says Col. Craig Butera, director of the MCOE’s Command and Tactics Directorate. “And I’m just convinced our Army is better for that.”

Inspired by his grandfathers, who both served in World War II, Major Vineyard knew as a child he wanted to be a soldier. War became real for him on Sept. 11, 2001. A senior at West Point, arriving for a lecture on terrorism, he along with his classmates initially thought the terrorist attacks on the Pentagon and World Trade Center that they saw on the classroom screen were part of a training video. “We’re probably five minutes into class, and no one said a word and everybody just watched,” he recalls. The instructor muted the screen. “He looked at us and said, ‘Gentlemen, your nation is at war. Class dismissed. Go to the barracks and wait for further instructions.’”

War became even more real two years later when Lieutenant Vineyard, then an artillery officer outside Baghdad, was struck by a car bomb as he and his platoon cleared safe passage for engineers. Loaded with 500 pounds of dynamite, TNT, and artillery shells, the bomb exploded about 15 feet from the group.

“We had no idea what was going on when the explosion happened,” he says. “I was in the air going backwards, and I was just surrounded by fire.”

Eight of his platoon members died in the blast, and its aftermath would test the faith that he had held firm since he first embraced Jesus at age 7 in vacation Bible school. “Everybody was gone.”

Sweats, nightmares, chaos, and trauma haunted him at the German hospital where he had been taken by medvac helicopter. His faith offered no consolation. Finally, desperate, he got on his knees next to his hospital bed and gave up the struggle.

“I said, ‘God, I’m going to give this to you. What was meant for evil, use it for good.’” Today, he says, “I believe God just honored that prayer. Right away I felt like something was scooped out of me.” He has not had a nightmare since, and though the tragedy of the loss remains with him, he feels freed to use it for good.

The spiritual transformation ultimately led him to the ministry. He received his master of divinity from Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, in 2008, and for four years afterward worked in civilian life as a youth pastor. He and his wife, Amanda, a former professional ballerina, lived their dream, working side by side, ministering as a couple and raising their children – who today number six, ages 6 to 16.

While satisfying part of his Army Reserve requirement, the chaplain further clarified his sense of calling. He was assigned to Fort Hood, Texas, the sixth choice on his list of preferred job assignments. As with other life-turning moments, he sees that as no random event. One day he was shadowing a base chaplain, listening quietly at the bedside of a wounded soldier. “[The soldier] is basically sharing what happened to me,” he says. “He was in an explosion, guys on his right and left died, and the point of his story is, ‘I have no hope.’”

The senior chaplain told the soldier he was sorry to hear that. Mr. Vineyard jumped in. “I said, ‘You’ve got the wrong ending. ... Let me tell you about my story.” His message resonated. Hope returned. As a result, the junior chaplain would wind up back at war.

“What was so hard for me about the decision to return to the Army was that my wife and I are really close, and for those four years, we did ministry together, and it was awesome.”

But he returned to the front lines, this time in Afghanistan, embedded as a chaplain with the 2-506th Infantry Battalion, 101st Airborne Division, made famous by the HBO series “Band of Brothers.” Offering counsel for needs temporal as well as spiritual, he often just listened. He recalls one soldier, the stereotype of a big, tough, reserved infantryman. “He had some massive, massive things that were weighing on him. I’m just not feeling really led to say anything, just to kind of listen to him, and we got to the end of an hour, and he says, ‘You ... are the best counselor that I can imagine.’ I chuckled.”

Today, after graduate studies in ethics at Yale Divinity School, he is one of 17 chaplains and two world religion instructors charged with formally training Army personnel in ethics.

The chaplain approaches his Fort Benning lectures with the zeal of a preacher. On one recent morning, he peppers the 150 captains in class with questions about ethical leadership.

He references the World War II movie “Saving Private Ryan,” screening an emotionally charged scene in which a group of soldiers, bent on revenge after its medic was killed by the enemy, debates what to do with a prisoner of war. The real-life complexities they often find themselves in muddy what should be a clear ethical decision: You never kill a prisoner.

The commander, played by Tom Hanks, winds up releasing the man, but his intentions leading up to the decision seem ambiguous, and this gives Major Vineyard an entree: What did the commander do here that was wrong? What was right? How can a leader balance competing values? Even if he ends up doing the right thing, can his attitude risk inciting one of his soldiers to make a mistake? There may not always be a clear right answer, but there is often a clear wrong one, he tells the officers.

Killing a prisoner of war is always wrong, according to the Army. So is failing to treat the enemy humanely, a “principle of honor” famously violated by American service members at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Also always wrong: intentionally failing to distinguish combatants from civilians, as happened at My Lai. An attack that has no military necessity is also always wrong, says Major Vineyard.

The Army uses “ethical, effective, and efficient” as benchmarks for right decisions, with the ethical component rooted in military necessity. The Army forbids unnecessary suffering and urges soldiers to exercise a sense of fairness, respect, and even honor toward opposing forces.

“I came in aggressive,” the chaplain explains of his lecture. He wants students to know that in the swirl of training, ethics “is the main event, not a sideshow.” The saying is a favorite of a teacher noted for his storehouse of memorable quotes: “You are the standard.” “Be that person.” “Leaders are readers.” “Be there.” “Beware, lest you become the monster you perceive your adversary to be.”

“He has a gift for communicating,” says Jason Baker, second lieutenant in the Georgia National Guard, who studied under Major Vineyard as a student at Officer Candidate School last year. “In class you can feel the passion of his personality and of his experience and so as a result, there were no sleepy eyes in my class. There were no disinterested faces.”

Especially early in training, when soldiers are being taught to think as part of the “collective,” ethics class stresses independent thought – the ability to recognize, for instance, whether an order is strictly legal or whether it is legal and moral, Second Lieutenant Baker says. “Because obviously throughout history, we have many examples of lawful orders that may not be moral orders.”

Still, the classroom and combat are two entirely different theaters. Major Vineyard, as a result, wants his charges to develop moral “muscle memory.” “When you get punched in the face, your ethical gloves better not come off,” he warns his students.

Cultural differences complicate moral decision-making. Opponents with different values exploit American ethical standards for their own advantage, using women or children as shields, for instance, or sending 12-year-olds out with guns. Major Vineyard calls reports of civilians intentionally being bombed in Ukraine “a reminder that our adversary, whoever it is, probably doesn’t fight like we do.”

In order to do the right thing, soldiers need to know what the right thing is. For that, the Army has “great doctrine,” the teacher tells his class. It’s rooted in the ancient Greeks – Aristotle, Plato, and Socrates – in the “just war” doctrine of St. Augustine, and in the culture and spirit of the American people. It draws on the famous Soldier’s Creed, the seven Army values, on established rules of engagement, treaties, and ultimately the U.S. Constitution. Decisions are tested against often-competing philosophies of Immanuel Kant and John Stuart Mill: Is this what a virtuous person would do? Would you like to see everyone required to abide by this choice? Would it bring the best benefit to the greatest number of people?

“Who we are as an Army is your shield of protection,” he tells his class.

What if an order seems wrong? “We are never called as soldiers in the Army to do anything illegal, immoral, or unethical,” he says after class. “So if we believe something is immoral, there are two R’s: reject and report.” For broader moral objections, the long-standing principle of exercising conscience – though not part of Army doctrine – allows members to resign.

Since George Washington established it in 1775, the Chaplain Corps has concerned itself with moral character, initially warning soldiers off cursing and drunkenness. After World War II, a weekly “Chaplain’s Hour” radio program promoted virtue, and the Army advertised itself as a place where military personnel emerged better people than they were when they went in.

Lt. Col. Seth George, Deputy Combined Arms Center chaplain at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, who oversees all of the Army’s ethics instructors, says that the ethics effort intensified after Vietnam and the institution of the draft. The military was also demoralized after the war.

“In the late ’70s and ’80s, they were really looking at ‘How do we professionalize our Army?’ And that included everything from uniform standards, to tactical competency, to professional leadership, so that you have leaders that build trust,” he says.

The effort continues to evolve today, with a new field manual emphasizing holistic soldier readiness. “What does a soldier who’s ready for the mission look like? How are they performing? Are you mentally sound? Are you physically fit? Do you have a routine for sleep and nutrition? Are you spiritually connected or are you isolated?” says Lieutenant Colonel George. “It’s trying to communicate to commanders that there’s more than just the strict utility of accomplishing the mission.”

Looking at the mission through the lens of values illuminates behavioral standards, he says. “What does it look like to not only say, ‘I accept the Army values of courage and selfless service’? But how do I now engage another individual in my unit with dignity and respect?”

Colonel Butera speaks of societal “corrosives,” which also affect the Army, such as sexual harassment, political extremism, and discrimination. “If everybody was acting perfectly in alignment with the Army values and the Army Ethic, then we wouldn’t have these problems,” he says. “But we do have these problems. So it’s important that we continue to have leaders engaged with their populations, their followers, their counterparts. You have a responsibility to the American people.”

While a student at Yale, Major Vineyard visited the university’s art gallery, where he came upon “The Veteran,” Thomas Eakins’ portrait of George Reynolds, a Medal of Honor recipient depicted 20 years after his service in the Civil War. The chaplain says that, even before he knew the subject of the painting, he recognized in the eyes someone who had seen combat – one who, as he puts it, “has experienced the brokenness of the world.”

In his work as a chaplain, Major Vineyard has seen the look. “You just see the fullness of innocence lost, like the war never left them. After the Civil War they called the look ‘the soldier’s heart’ – what we might call today post-traumatic stress disorder or moral injury, though they’re not all the same thing.”

“Combat changes you,” he goes on. “You can come out better or you can come out worse. You get a vote in that.”

He recalls the potentially disabling emotion he felt in 2004, after a vehicle two cars ahead of him in a caravan was bombed in an ambush. His unit was already suffering unrelenting casualties. “You can see where you have empathy for people who lose it,” he says of his response to the attack. The warrior who has seen too much needs to know, he says, “What are you going to give me, Army?”

For some, relationships with fellow combat veterans have spiritual overtones that can be redemptive. “Yes, it’s hard. But you’ve got another family now,” he says of the military. “For the rest of your days, here’s another family that – they just know. And the neat thing is, it doesn’t even have to be [people] of your generation. You’re one of us.” It wasn’t until he returned from Iraq that his grandfather spoke of his own experiences in World War II.

Major Vineyard’s lifelong relationship with God, put to the test, saved him. When ministering to other believers, he talks about it. He guides nonbelievers to timeless principles – encased in religion but accessible to everyone – principles like “choose life,” principles like the golden rule. “I wouldn’t quote the Bible, but I would say, ‘Hey, I think in your heart, you understand that there’s choices that you get to make. There’s destructive, and there’s helpful, and my challenge for you is choose the helpful.’”

“I’ve seen transformation happen with soldiers. And I’ve seen the other as well. It’s hard to see sometimes. Sometimes they’ll listen, and sometimes they won’t. ... I say, ‘I can’t be your Messiah. I can’t save you. ... I can give advice. I can be here. I can listen. But, you know, you get a choice in this.’”

By Wednesday evening, Family Night at the on-base chapel, the chaplain is in full-on pastor mode, his rapid-fire delivery still intact. Leading a Bible study group, he draws laughter from the class as he likens God’s excluding Moses from the Promised Land to regime change. He’s home – a place where a Scripture citation illustrates everyday experience, where believers talk of a God who speaks to them personally, and where he and his wife listen for divine guidance in every decision.

“He practices what he preaches – very much,” says Amanda Vineyard, who reaches out to base families through children’s programs and marriage enrichment wherever the couple is stationed. “I feel like the happiest military couples feel called to it – like this is our adventure and we’re in it together.”

Major Vineyard is legendary for being accessible to soldiers – on the base and after they move on. “He’s still incredibly responsive, even to little old me,” says Second Lieutenant Baker, the Georgia Army National Guard member. “I know that I can text him right now and hear back from him today. But that’s not only me. He would do that for any soldier.”

And the soldiers do benefit from his help.

Colonel Butera, illustrating the “Be there” ethic of the chaplain, shares a story. “I’ll try not to get choked up in offering this,” he says, eyes filling. “But there was somebody who I heard say that they owe their life to him, just through him being accessible during a certain challenging time. I mean if that’s not impactful, I don’t know what it is.”

Work from home? Alabama towns say ‘Come on down.’

The work-from-anywhere boom may be a boon to small towns struggling with population decline. Some of those places are paying for new residents – encouraging people who work from home to rethink home and replant their roots.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Xander Peters Special correspondent

The onset of COVID-19 in spring of 2020 came with hardships for small communities in Northwest Alabama, as it did everywhere. But it also represented an opportunity for programs like Remote Shoals, which offers cash incentives to remote workers willing to relocate.

The pay-to-move concept’s increase in popularity intersects with a tumultuous era and debate over how Americans view workspace. As recent as two years ago, most industries still preferred and maintained traditional office spaces. But with the pandemic shutdown, remote work boomed, while boredom and separation among many pandemic shut-ins inspired a will for change.

That was true for the Millimans, who relocated to Florence, Alabama, through Remote Shoals.

Shannon Milliman grew up in rural Alaska; Eli Milliman, Anchorage. They started a family in Portland, Oregon, where their five children (ages 19, 18, 16, 14, and 11) and two dogs outgrew a 1,000-square-foot home. Portland city life had also grown stale. The Millimans knew they would miss their cosmopolitan lifestyle, but wanted stability – and a larger home to fit their needs seemed unobtainable in Portland. The family was ready to try the slower pace of Southern small-town life. One of the reasons they chose Florence was because of nearby Muscle Shoals, known for its rich music history.

“There’s been a lot of culture shock – I don’t know,” Ms. Milliman says, smiling, as her eyes dart toward husband Eli Milliman on the opposite end of the couch. “Different mindsets, which is good, right?”

Work from home? Alabama towns say ‘Come on down.’

It’s springtime in Northwest Alabama, when the birds chirp away in the evenings as Heather Brown and her wife, Janice, watch the day slip by from their white-painted front porch in Sheffield.

It’s a slow-paced town of about 9,000, among a series of small towns nestled in Alabama’s steep hills that seem to stand guard against hastened city life. Ms. Brown toured Sheffield only once before they moved here last year. It didn’t take long for it to feel like home.

By November, their household – dogs included – had relocated from Knoxville, Tennessee, which sits north up the winding Tennessee River. It felt at the time like the river’s current was carrying their lives downstream to small-town Alabama, where they intend to live permanently.

Ms. Brown laughs at the notion – that the river’s powerful push carried their belongings and dogs to Northwest Alabama, like children on a wooden raft. She used a similar metaphor last year during interviews with Remote Shoals, the pay-to-move initiative that brought them here. It allocates up to $10,000 to remote workers who earn at least $52,000 a year. Participants have the option of buying or renting a home in their new community and can leave without repayment after a year. Ms. Brown’s household intends to stay.

The pay-to-move concept’s increase in popularity intersects with a tumultuous era and debate over how Americans view workspace. As recently as two years ago, most industries still preferred and maintained traditional office spaces. But as noted by Mackenzie Cottles, a marketing and communications specialist at the Shoals Economic Development Authority, the COVID-19 pandemic hosted a rethink of what it means to work, and where.

The onset of COVID-19 in spring of 2020 came with hardships for the community, as it did everywhere, but it also represented an opportunity for programs like Remote Shoals. Remote work boomed due to workplace shutdowns. Boredom and separation among many pandemic shut-ins inspired a will for change, and thus a reason to leave cities for towns like Muscle Shoals.

For folks like Ms. Brown, it was as good a time as any to make a change.

“This community decided to invest in me,” Ms. Brown says of the Remote Shoals program. Now, she wants to invest back – financially, once she and Janice eventually buy a new home, as much as emotionally.

Ready for something new

The Remote Shoals program, which encompasses the four main towns in Colbert and Lauderdale counties – Sheffield, Florence, Muscle Shoals, and Tuscumbia – isn’t the first of its type to pay remote workers and their families to pick up their lives and relocate. In recent years, incentivization has gained traction across the United States – Tulsa, Oklahoma; Newton, Iowa; Natchez, Mississippi; and Johnson City, Tennessee, are also among the municipalities to launch relocation stipend programs. And similar to other pay-to-move programs, Remote Shoals’ ultimate goal is to counter population stagnation and pave a path to the future.

Remote Shoals is publicly funded through a half-cent sales tax in Colbert and Lauderdale counties. The revenue goes to the Shoals Economic Development Fund, which launched the program in 2019. Ten remote workers were accepted that first year.

Three years into the program – two years into the pandemic – Remote Shoals has accepted 62 participants, many with families. Ms. Cottles says the number of participants in the program grows by the week. And while the Shoals Economic Development Fund has yet to publish a comprehensive economic impact statement, they cite a $6 million increase in local gross domestic product so far through its participants.

Pay-to-move programs have upsides for municipalities, says Justin Harlan, managing director for Tulsa Remote, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Tulsa Remote’s 1,600 participants added $60 million to the city’s GDP in 2021 alone, according to Mr. Harlan. But it also provides an opportunity for outsiders to see regions in a new light.

“Folks have a specific image in their head when they think of Oklahoma,” Mr. Harlan says. However, what visitors “find is that Tulsa does not match that image at all.”

More importantly, newcomers have found a home. Several years into Remote Tulsa, 98% of participants remained in the city for the full-year commitment. Another 88% stayed beyond the initial year, according to data from the bipartisan Economic Innovation Group, which released a study in November on Remote Tulsa’s impact so far.

The retention rate is expected to slip over time, but even with lower rates the programs have a strong economic impact, says Kenan Fikri, Economic Innovation Group’s director of research. The incentives actually “target the feedstock of growth in the modern economy, which is people and human capital,” he adds.

On its face, it’s an easy pitch to recruits looking for not only a change in lifestyle, but also an affordable place to grow roots. Both were draws for the Milliman family, who recently moved to Florence, Alabama, through Remote Shoals.

“There’s been a lot of culture shock – I don’t know,” Shannon Milliman says, smiling, as her eyes dart toward husband Eli Milliman on the opposite end of the couch. “Different mindsets, which is good, right?” Mr. Milliman leans his elbows over his knees and clasps his fingers together. He nods and smiles back at his wife.

Ms. Milliman grew up in rural Alaska; Mr. Milliman, Anchorage. They started a family in Portland, Oregon, where their five children (ages 19, 18, 16, 14, and 11) and two dogs outgrew a 1,000-square-foot home. Portland city life had also grown stale. The Millimans knew they would miss their cosmopolitan lifestyle, but wanted stability – and a larger home to fit their needs seemed unobtainable in Portland. The family was ready to leave.

They looked east for new opportunities. Mr. Milliman, a musician and photographer, researched cultural scenes across the country and educational opportunities in the arts for their children. Meanwhile, Ms. Milliman remembered reading about pay-to-move programs, which fit her new work situation. They landed on Remote Shoals.

Among the selling points was neighboring Muscle Shoals, with its outsize role in American music history. The town of about 14,000 people has attracted icons to its studios: Bob Dylan, the Allman Brothers, Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, Rod Stewart, George Michael, Paul Simon.

And the Rolling Stones, who recorded “Wild Horses” there in 1971. “I love that song,” Mr. Milliman says. Florence, which is just 10 minutes away and where the Milliman family purchased their 4,000-square-foot home sight unseen, has its own rich history of blues music.

One day, they hope to make an impact on their new community. They’re working on a magazine inspired by local art. The inaugural issue, they say, will focus on water.

Where the river sings

In Muscle Shoals, a rock wall stands in tribute to the region’s eclectic charm – and the tenacity of its Indigenous people. In the 1830s, a young Yuchi woman was among thousands of Native Americans forcefully removed from the region and sent to Oklahoma with armed escorts along the Trail of Tears. As 15-year-old Te-lah-nay and her sister attempted to settle into unfamiliar lands, they claimed the rivers of Oklahoma didn’t sing like the one back home.

Te-lah-nay escaped the Oklahoma territory on foot, journaling the five-year trek back to her singing river in Northwest Alabama. When her great-great-grandson discovered the journals in the 1980s he built a wall of stones near Muscle Shoals – 38 billion tons of rock, a nod to each step of Te-lah-nay’s journey back to the Tennessee River, known locally as the Singing River.

If Ms. Brown has anything to say about it, she’ll hear that river sing for a long, long time.

Through Remote Shoals, her wife has received help in landing her own full-time job. The weather’s only gotten warmer in recent weeks, which means they will finally go hiking. They’ve joined a local Unitarian church. They’ve made friends.

“This is it,” Ms. Brown says of staying in Sheffield.

When their lease is up later this year, they hope to buy a house in the nearby countryside. If all goes according to plan, says Ms. Brown, they’ll live near the water.

The Explainer

Voting: Should it be only for citizens?

A renewed effort to enfranchise immigrants swims against American public opinion on the issue. But some cities see the right to vote as a way to strengthen community commitment of residents – citizens or not.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Across the United States, 22 million noncitizens pay taxes, send their children to schools, own businesses, and even serve in the military. Should they be allowed to vote?

More than a dozen cities – including New York and San Francisco – say “yes” and allow noncitizens (legally authorized to be in the U.S. or not, depending on the city) to vote in local elections.

A range of arguments for enfranchisement include the American Revolution slogan “no taxation without representation” and the notion that voting helps prospective citizens strengthen community commitment.

An Atlantic-Leger poll in December found a majority of Americans do not support enfranchising noncitizens. Opponents say that, to have that right, a person should assume the responsibilities of citizenship, such as jury duty and renunciation of allegiance to other nations. Critics also suggest the citizenship test required of new citizens indicates some knowledge of civics informing their voting. The issue has become heated, too, with increasing visibility of the extreme right “replacement theory,” which purports a conspiracy to diminish the influence of white people.

“The essence of democracy is that stakeholders should have a say,” says Ron Hayduk, a political scientist at San Francisco State University who studies immigrant voting rights. The question is, what makes “a legitimate stakeholder in a community?”

Voting: Should it be only for citizens?

The right to vote may seem inextricably linked to citizenship in the United States. But since America’s founding, 40 states – at different times – have allowed noncitizen voting in local, state, or federal elections; and while today it’s now illegal for noncitizens to vote at the federal and state level, more than a dozen cities do allow noncitizens (legally authorized to be in the U.S. or not, depending on the city) to vote in municipal elections. Citizenship, though, has not always guaranteed voting rights: Gender, race, and age have also been criteria.

Debate over the issue flared in December when New York City passed a law allowing 800,000 immigrants residing in the city legally to vote in city elections, and Florida Republican Sen. Marco Rubio introduced a bill prohibiting noncitizen voting nationwide. The issue has become heated, too, with increasing visibility of the conservative far right “replacement theory,” which purports a conspiracy to diminish the influence of white people.

“The essence of democracy is that stakeholders should have a say,” says Ron Hayduk, a political scientist at San Francisco State University who studies immigrant voting rights. The question is, what makes “a legitimate stakeholder in a community?”

What are basic arguments for and against enfranchising noncitizens?

An Atlantic-Leger poll in December found a majority of Americans do not support allowing noncitizens to vote. Opponents say that, to have that right, a person should make the effort to assume a citizen’s responsibilities, such as jury duty and renunciation of allegiance to other nations. Critics are also concerned with outside influence that could threaten national security; and they suggest that the citizenship test required of new citizens indicates some knowledge of civics to inform their voting.

“You need some marker ... to gauge people’s interest in and commitment to becoming an American,” says Stanley Renshon, a political scientist at the City University of New York. Noncitizens, he says, can already participate in politics in many ways, from protesting to donating to campaigns.

A range of arguments for enfranchising the estimated 22 million noncitizens living in the U.S. include the American Revolution slogan “no taxation without representation” and the notion that voting is a practice in civics that helps prospective citizens strengthen their community commitment.

“Immigrants tend to score low on most indicators of well-being: education, health care, housing, income, wealth,” says Professor Hayduk. Immigrant rights advocates say that if noncitizens were able to elect their representatives, it could move these outcomes in a more egalitarian direction.

Does noncitizen voting harm the rights and interests of citizens?

In recent times, noncitizen voting has had minimal impact nationally because local elections are the only place it is allowed, and the numbers are small, says Professor Hayduk.

For example, in Takoma Park, Maryland, a city of 18,000 residents, which allows legal residents as well as those who immigrated illegally to vote, the noncitizen voter turnout falls between 50 and 70, says City Clerk Jessie Carpenter.

Even in San Francisco, where any noncitizen parent can vote in school board elections, the average noncitizen turnout is less than 100, says John Arntz, Department of Elections director there.

But when New York City allowed noncitizen voting in school board elections between the 1960s and the early 2000s, says Professor Hayduk, “noncitizen voting was a big contributing factor that tipped the balance of power,” at least in certain districts with high concentrations of immigrants. And that, he adds, “led to policy changes – increased funding for schools, the building of new schools.”

Speaking hypothetically, Hans von Spakovsky, a senior legal fellow at The Heritage Foundation, suggests that if “a reporter for Pravda, the propaganda arm of Russia, can vote in local elections in New York” it would make “no sense whatsoever.”

Is noncitizen voting feasible and secure to implement?

In San Francisco, election workers set up a new system to register voters and process ballots, says Mr. Arntz, the election official. “It was not easy,” he says, but “once we got set up, it’s pretty straightforward.”

Takoma Park has experienced no logistical difficulties because since 1993, noncitizens have gone through the same voting process as citizens, says Ms. Carpenter.

One concern shared on all sides is that noncitizens could by accident or intention vote in state and federal elections. But Professor Hayduk says there has been “minuscule” evidence that fraud happens.

Television

Can a show about corruption lead to better policing?

What role can a television show play in helping people understand different perspectives in the debate about police reform? “We Own This City,” based on a true story, aims to get people talking.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Gregory Wakeman Contributor

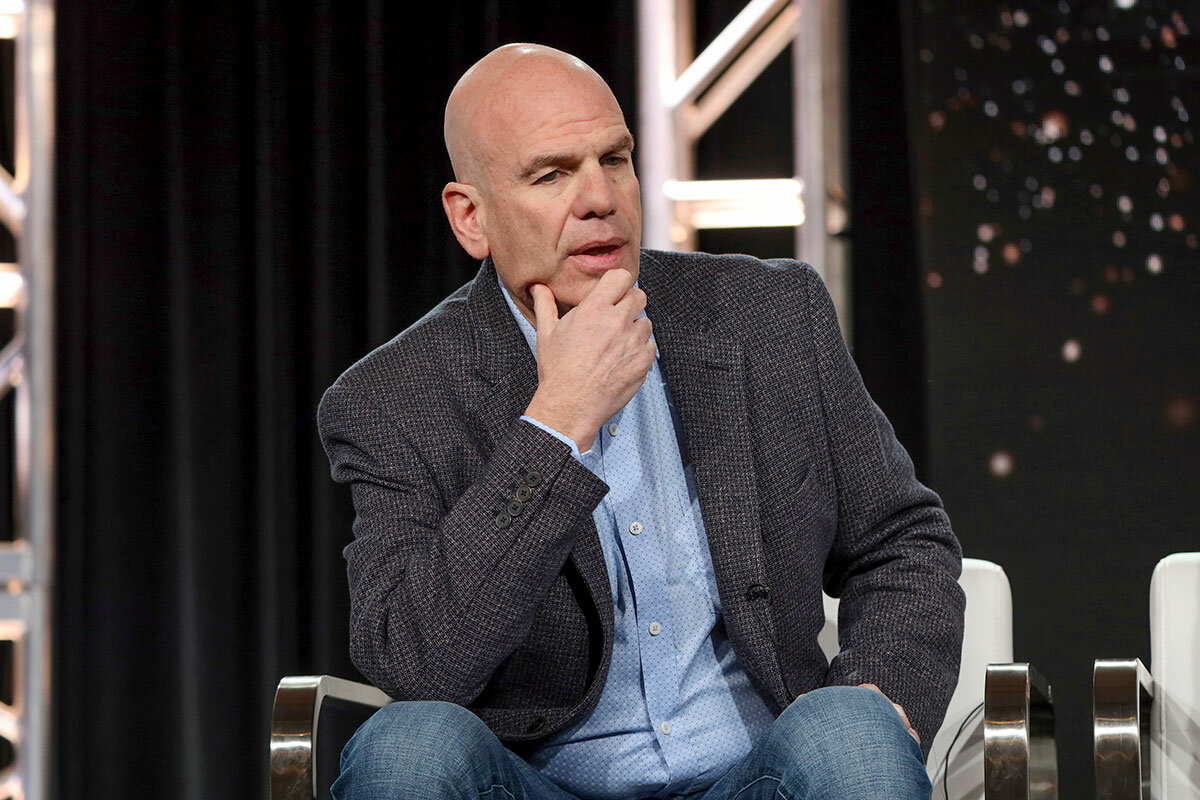

When George Pelecanos first read “We Own This City” – a book about crime in the Baltimore Police Department – he contacted his longtime collaborator David Simon, whom he had worked with on “The Wire,” and suggested that they make it into a show.

They immediately wondered how they could distinguish it. It couldn’t “just be about corrupt cops. That’s been done before,” says Mr. Pelecanos. “But the state of policing in America was at a tipping point. All these things had happened since ‘The Wire,’ especially with the Freddie Gray uprising, which pushed us to really tell the story.”

“We Own This City” debuted this spring on HBO, with the fifth of six episodes available on May 23. The series gave Mr. Simon and Mr. Pelecanos, who executive produced and wrote for it, a chance to “restate the basic theme of ‘The Wire,’” says Mr. Simon, which is the futility of the drug war. It also allowed them to explore the systemic problems in the police department.

Their show, he says, tries to get at, “Why is this story indicative of the problems of policing in this country? Why is [policing] worth fighting for?”

Can a show about corruption lead to better policing?

After the critical acclaim of “The Wire,” it was always going to take a huge story for its creator, David Simon, to return to the world of crime, drugs, and the Baltimore Police Department.

But when the real-life corruption scandal of the city’s Gun Trace Task Force was exposed in the spring of 2017, Mr. Simon didn’t immediately see the criminal acts of the officers as a television show. Instead, he called Baltimore Sun crime reporter Justin Fenton and told him, “This is a book. You need to step back and gather up your reporting,” Mr. Simon, who used to have the same beat at the paper, recounts in a recent interview.

Mr. Fenton did just that with “We Own This City: A True Story of Crime, Cops, and Corruption.” Released in February 2021, the book details how, with murders increasing and riots flaring up across the city after the 2015 death of Freddie Gray in police custody, the BPD looked to Sgt. Wayne Jenkins and his plainclothes unit to help rid the streets of guns and drugs. Mr. Jenkins and his crew, it turns out, were using the power of the Gun Trace Task Force to steal thousands of dollars from citizens, sell drugs obtained during raids, and plant evidence. Their misconduct resulted in a raft of wrongful convictions.

After reading the manuscript for the book, George Pelecanos, who wrote for “The Wire” and co-created “The Deuce” with Mr. Simon, suggested they make it into a show.

Yet it couldn’t “just be about corrupt cops. That’s been done before,” says Mr. Pelecanos. “But the state of policing in America was at a tipping point. All these things had happened since ‘The Wire,’ especially with the Freddie Gray uprising, which pushed us to really tell the story.”

“We Own This City” debuted this spring on HBO, with the fifth of six episodes available on May 23. The series gave Mr. Simon and Mr. Pelecanos – who developed, executive-produced, and wrote for it – a chance to “restate the basic theme of ‘The Wire,’” says Mr. Simon, which is the futility of the drug war. It also allowed them to explore the systemic problems in the police department.

“The system allowed these guys to be corrupted,” says Mr. Pelecanos.

Their show, says Mr. Simon, tries to get at, “Why is this story indicative of the problems of policing in this country? Why is [policing] worth fighting for?”

“It’d be very simple to just say this guy [Mr. Jenkins] was pure evil and he’s a bad apple. But there’s something wrong with the orchard,” he adds.

In the opening episode, future Gun Trace Task Force member Daniel Hershl (Josh Charles) pulls over a father for no reason and then emasculates him in front of his son. Mr. Pelecanos says he wanted to convey how the officer intentionally makes the driver feel powerless.

After reading Mr. Fenton’s book, Michael Pinard, a professor of law at the University of Maryland, says that he was happy to hear that the talent behind “The Wire” would be adapting it. “Particularly given the creators, I thought it would be important to tell the horrific story, but only if the story was situated within the broader policing issues in Baltimore and the institutional racism that allowed the Gun Trace Task Force to thrive,” he says.

He notes that the show has highlighted how the Department of Justice was involved with the BPD even before Mr. Gray’s death, “which hints at the systemic issues that were then detailed and displayed in infamy after his death.”

“No show can tug at all the roots of institutional racism,” he adds. “But I hope that viewers are asking the questions of why these officers were emboldened to commit these crimes and why they were able to get away with so much for so long. They saw their victims as disposable, and institutional racism set the stage for them. We need to get at the layers of why.”

Police departments need to figure out how to make “officers the true partners of residents and the guardians of these communities,” he says.

“What would happen if we actually rewarded police for doing the work that the cities need?” wonders Mr. Simon, who wants “We Own This City” to provoke discussions on police reform. “If you talk to people in the neighborhoods that are most vulnerable, they don’t want to be harried and brutalized by the police over stuff that doesn’t matter.”

That’s part of the reason Mr. Simon and Mr. Pelecanos wanted to write about the injustice of the mass police stops, arrests, and incarcerations in the city, and the impact those have on the victims.

Residents would regularly come up to them while the series was filming and reveal that they’d been robbed or harassed by members of the Gun Trace Task Force. “You really got a sense of how impacted they were by these events and how powerless they felt,” says Mr. Pelecanos, who wants the show to provide a voice for those who have been affected by these issues.

“We Own This City,” directed by Reinaldo Marcus Green (“King Richard”), takes a nonlinear approach, showing in the first episode, for example, Mr. Jenkins (played by Jon Bernthal) being arrested. Subsequent episodes then look at his rise through the police ranks, including how, according to the show, he was told to disregard his training – alternating between that background and key events in the timeline of the Gun Trace Task Force.

Mr. Fenton hopes the program will convince people to demand that their police departments operate with more transparency and accountability. “The inclusion of civilian and oversight boards is something that can help,” says Mr. Fenton, who is the first to admit that he “doesn’t have the answers.”

“Baltimore is in an existential moment of, ‘What do we want police to do?’” he says. “For some people, I think the answer is defund the police: Take the money and put it in places where it can make a difference from the root causes. But there’s a tremendous fear that if you pull police out, there will be serious, deep problems in the city, and all hell will break loose. ... [The police] have to figure out how to reform the department, while still keeping people safe.”

“We Own This City” is rated TV-MA for adult content and language, violence, and some nudity. It airs Monday nights on HBO and streams on HBO Max.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A global gauge to set the world aright

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The first five months of 2022 have provided vivid illustrations of how the world’s problems have become even more interconnected. The war in Ukraine has exacerbated the effects of climate change on food, and its impact on fuel supplies has prolonged inflation and goods shortages resulting from the pandemic.

But the year may also mark a turning point in the way the world addresses its challenges. One sign is momentum toward setting standards in the way corporations measure their environmental and social impact and create transparency in the way they are governed.

Business leaders gathering at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, this week are considering a “global baseline” that would measure how well they meet their commitments on issues like climate change and inequality.

As common threats draw the world closer together, the imperative has also grown to forge global solutions that rely on shared standards of accounting. Honesty in numbers will help ensure reliability in results.

A global gauge to set the world aright

The first five months of 2022 have provided vivid illustrations of how the world’s problems have become even more interconnected. The war in Ukraine has exacerbated the effects of climate change on food insecurity in Africa and Asia, and its impact on fuel supplies has prolonged inflation and goods shortages resulting from the pandemic.

But the year may also mark a turning point in the way the world addresses its challenges. One sign is momentum toward setting standards in the way corporations measure their environmental and social impact and create transparency in the way they are governed.

Business leaders gathering at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, this week are considering a “global baseline” that would measure how well they meet their commitments on issues like climate change and inequality. The framework was drafted by a new International Sustainability Standards Board established by global leaders at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Scotland last November and endorsed by the Group of Seven last week.

The need for better reporting standards has grown with a shift in public expectations. As the effects of climate change and social inequality become more widely felt, many investors are demanding accountability from the companies they buy as much as solid returns. That mirrors expectations among the wider public. A survey of the Edelman Trust Barometer released in Davos found that among 14,000 respondents from 14 countries, 77% “believe improving societal issues is a primary business function” and 71% expect CEOs to take a lead role in shaping policies to tackle global warming.

Tracking how corporations steward the public good, however, is complicated. Demand for corporate accountability has brought more confusion than clarity. There are now more than 2,900 investment funds worth $2.7 trillion, according to Morning Star, that are based on environmental, social, and governance criteria. That, in turn, has sparked a cottage industry of consultancies offering to help investors and corporations determine sustainability benchmarks. But no common standard exists.

A recent U.N. survey of 1,230 CEOs from 113 countries found that while 71% said they were working toward net-zero emissions targets in their companies, only 2% of the companies they represent had plans validated by a scientific metric based on the 2015 Paris Agreement goals.

Judging whether a company meets social commitments is even harder. “It’s difficult to compare what one company does to broaden financial inclusion to what another might do to further education,” Michael Froman, vice chairman and president of strategic growth at Mastercard, told the World Economic Forum. “Yet that is precisely the type of commitment we want to encourage.”

The United States, Britain, and the European Union have all announced plans to impose mandatory sustainability reporting requirements. The framework from the International Sustainability Standards Board is different, notably, because it would be voluntary. While it provides a baseline for rationalizing the approaches those governments have proposed, more importantly it is helping business leaders find a common language on issues they are embracing with increasing urgency.

“For too long, markets around the world have been ill-equipped to efficiently price the risks and opportunities related to a raft of shared social and environmental challenges, from climate change and resource constraints to economic inequality and racial injustice,” Maha Eltobgy, Brightstar Capital Partners managing director and chief sustainability officer, said ahead of the Davos summit. “To ensure resilience and drive towards progress, a coherent, comprehensive system of corporate disclosure is needed.”

As common threats draw the world closer together, the imperative has also grown to forge global solutions that rely on shared standards of accounting. Honesty in numbers will help ensure reliability in results.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Active, healing peacemaking

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Our ability to be peacemakers comes from turning to God, the source of peace, and letting divine Love guide our footsteps toward practical solutions. This God-given peace begins within each heart, overflows to the world, and is lasting and all-inclusive.

Active, healing peacemaking

In light of the division, mistrust, and war that currently dominate the headlines, it’s natural for people to be thinking much more now about the deep need for peace in our world today. Sometimes it can seem as though conflict owns all the activity while peace is a passive hope.

But making peace is a healing activity that expresses God and is blessed by God, according to one of several of the Beatitudes shared by Christ Jesus. He said: “Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God” (Matthew 5:9).

I learned about peacemaking when I was a boy, when I would try to break up fights and help people become friends again. I saw that this was something important to do, but I only had mixed results. Eventually I learned that well-meaning human effort isn’t enough. I found that what is needed is a spiritual response, the action of God at work in human thought. That truly pacifies and enlightens.

God conceives peace as a quality that isn’t fleeting or unstable but unbreakable and lasting, expressed in each of us as His spiritual offspring. In any moment, we can choose to acknowledge this divine peace as the reality and feel it counteract concern and frustration. Within the precinct of thought, we can establish a love for spiritual peace, and as this view of peace becomes fixed in us, it then overflows into the world.

As the children of God, divine Love, we can both feel and express the great peace given to us by our creator, as we confront the stresses of daily living. The Bible says that God is here, “to give light to them that sit in darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the way of peace” (Luke 1:79).

God’s boundless peace, lived and loved, may begin in an individual as just a tiny light, but that light can grow to embrace others and envelop and enlighten the earth. Effective prayer is being open for God to guide us solidly “into the way of peace.” Hand in hand with this God-given peace comes resolution. A simple cease-fire that doesn’t address and resolve strife isn’t really peace; it’s just a muted interval between aggressive actions. Peace, to be genuine and enduring, must encompass everyone fairly and logically. Only the power of God, acknowledged and honored, engenders that kind of peace.

In a neighborhood where I used to live, there developed a growing conflict with an adjacent group of neighbors. The issue was water rights. Between suits and countersuits, we enjoyed some quiet times. But those intervals didn’t mean that everyone was at peace, as the issue remained unresolved.

As I prayed for resolution, I soon realized that this was an opportunity to be something of the kind of peacemaker that Jesus was talking about. I saw that, not just for the members of the two neighborhoods, but for the world, our deep hunger for peace and resolution is fed when individuals pause in prayer, yielding to the governing power and intelligence of God to direct our thoughts and actions.

As time went on, I began to appreciate more and more the ways God’s peace is reflected in His creation. People on both sides continued to have negative feelings about one another, but I was so taken up with praying to see God’s wonderful expression of peace reflected in all His creation that I stopped being distracted by the negativity.

As each month went by, I more consistently recognized the peaceful oneness we all naturally have with God, in which no one is excluded. My days overflowed with a joy for it all. Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy, in her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” comments how this approach to prayer operates to heal. She says, “One infinite God, good, unifies men and nations; constitutes the brotherhood of man; ends wars; ...” (p. 340).

One day, the whole issue was suddenly resolved amicably. Everyone agreed on a logical and fair way forward. This experience of praying for peace was a modest one, but it hints with promise at how each of us can magnify in our thoughts the spiritual peace that God gracefully emanates within each of His children.

Active, healing peacemaking, the kind of peacemaking that witnesses unreservedly to God’s power, is naturally loved by each of God’s children. As the Bible puts it, “And the fruit of righteousness is sown in peace of them that make peace” (James 3:18).

A message of love

Anyone there?

A look ahead

Thanks for starting another week with us. Come back tomorrow. We’ll have a report from Monitor justice writer Henry Gass about John Roberts, chief justice of the United States, who is seen by many as waging a high-stakes battle to maintain public trust in the Supreme Court. Henry will be looking at the major challenges Chief Justice Roberts now faces.